BETWEEN CERTAINTY AND EPHEMERALITY

“The essentially religious nature of the white cube is most forcefully expressed by what it does to the humanness of anyone who enters and cooperates with its premises.”

Brian O’Doherty

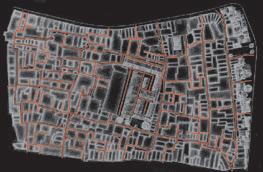

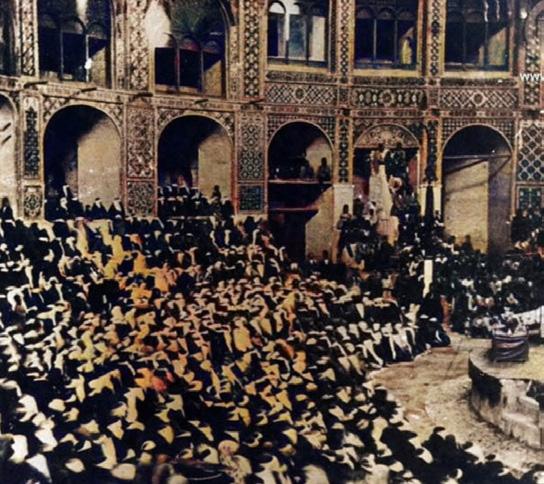

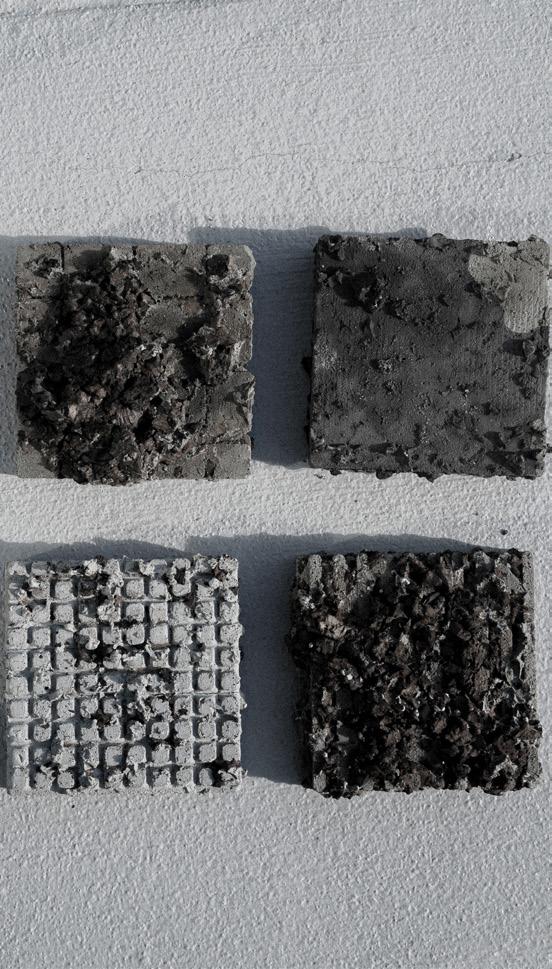

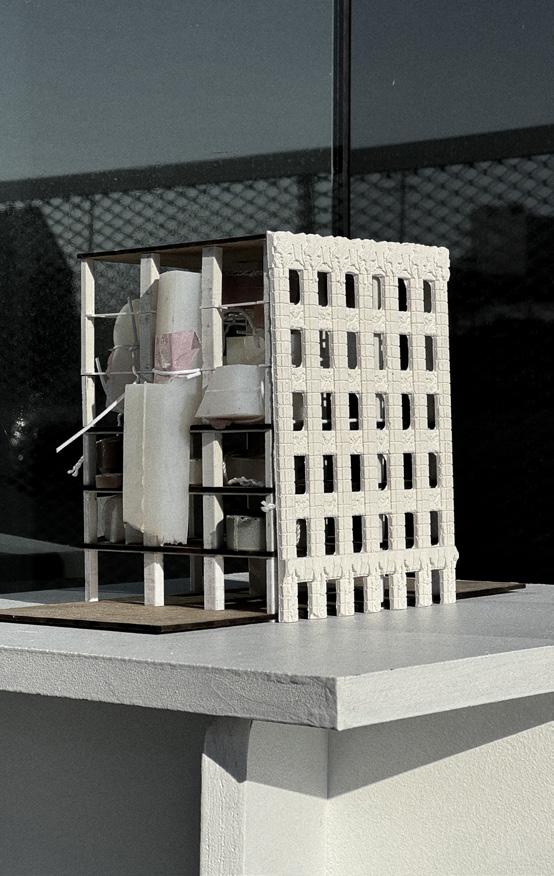

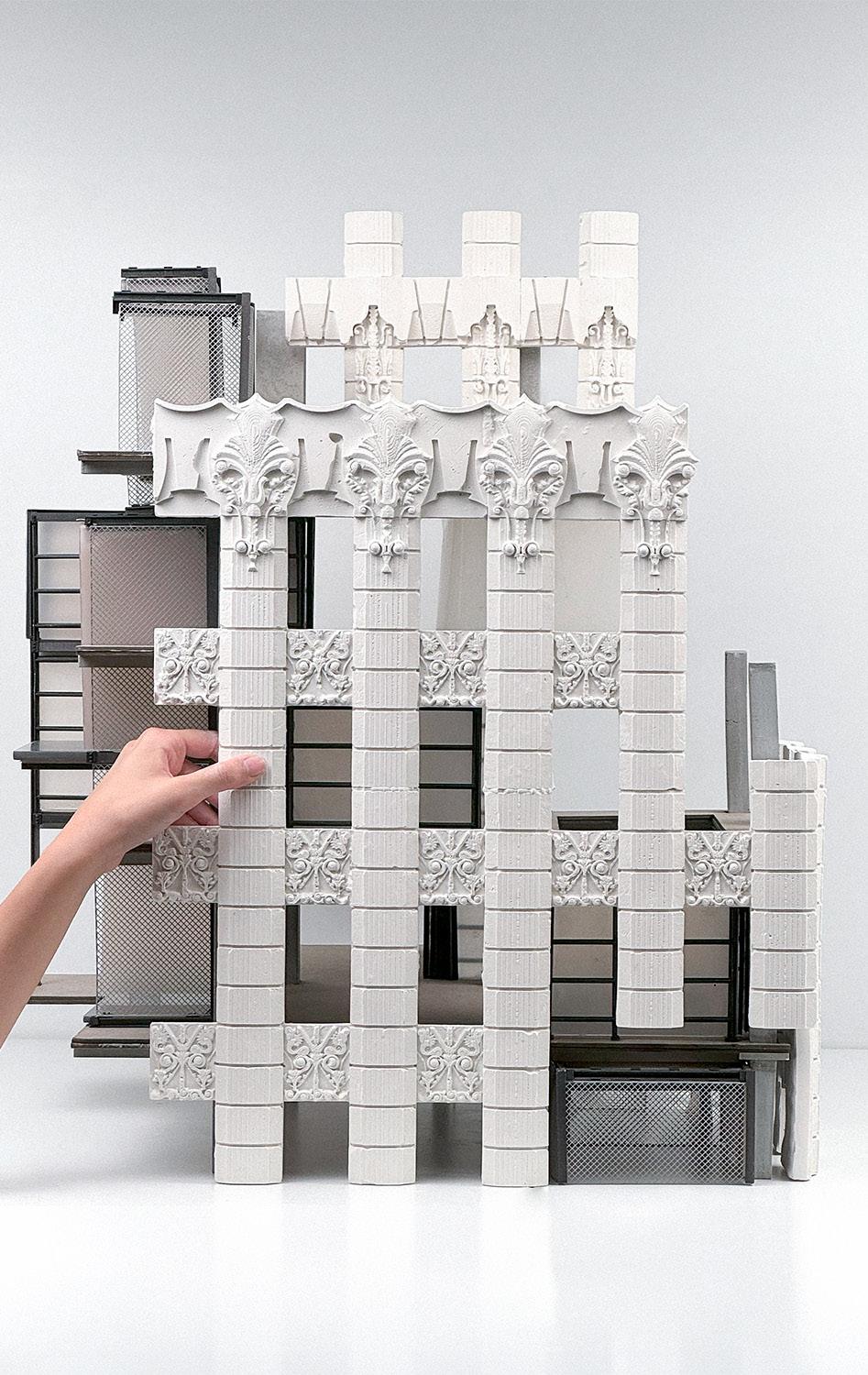

Spectrum_34 [02_4] Spatial Typology

Spectrum_56

Churches ‘White Cube’ Informal Space

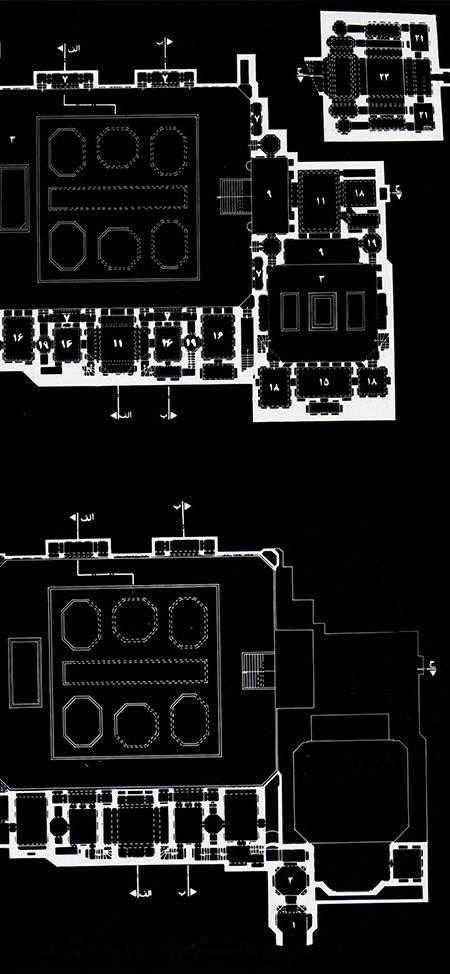

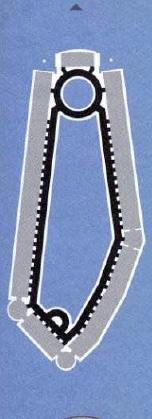

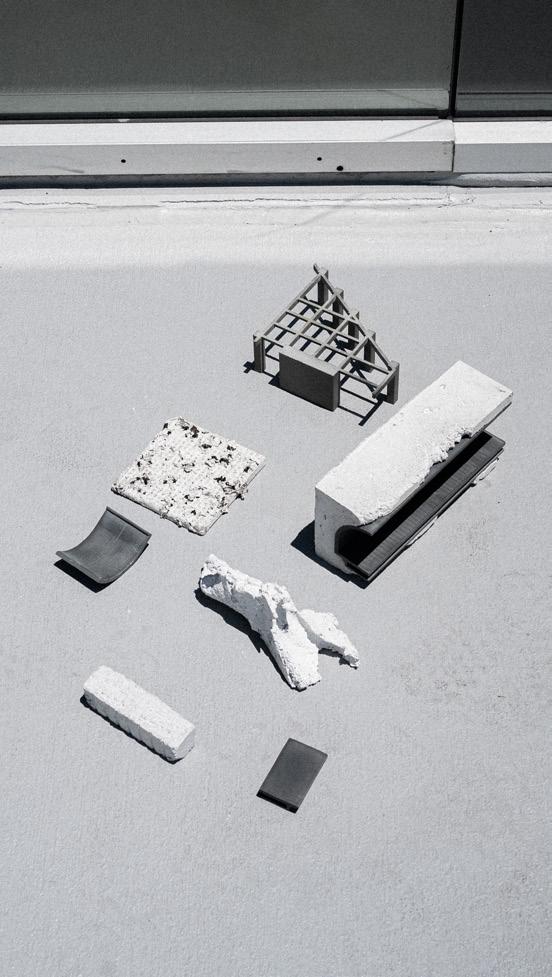

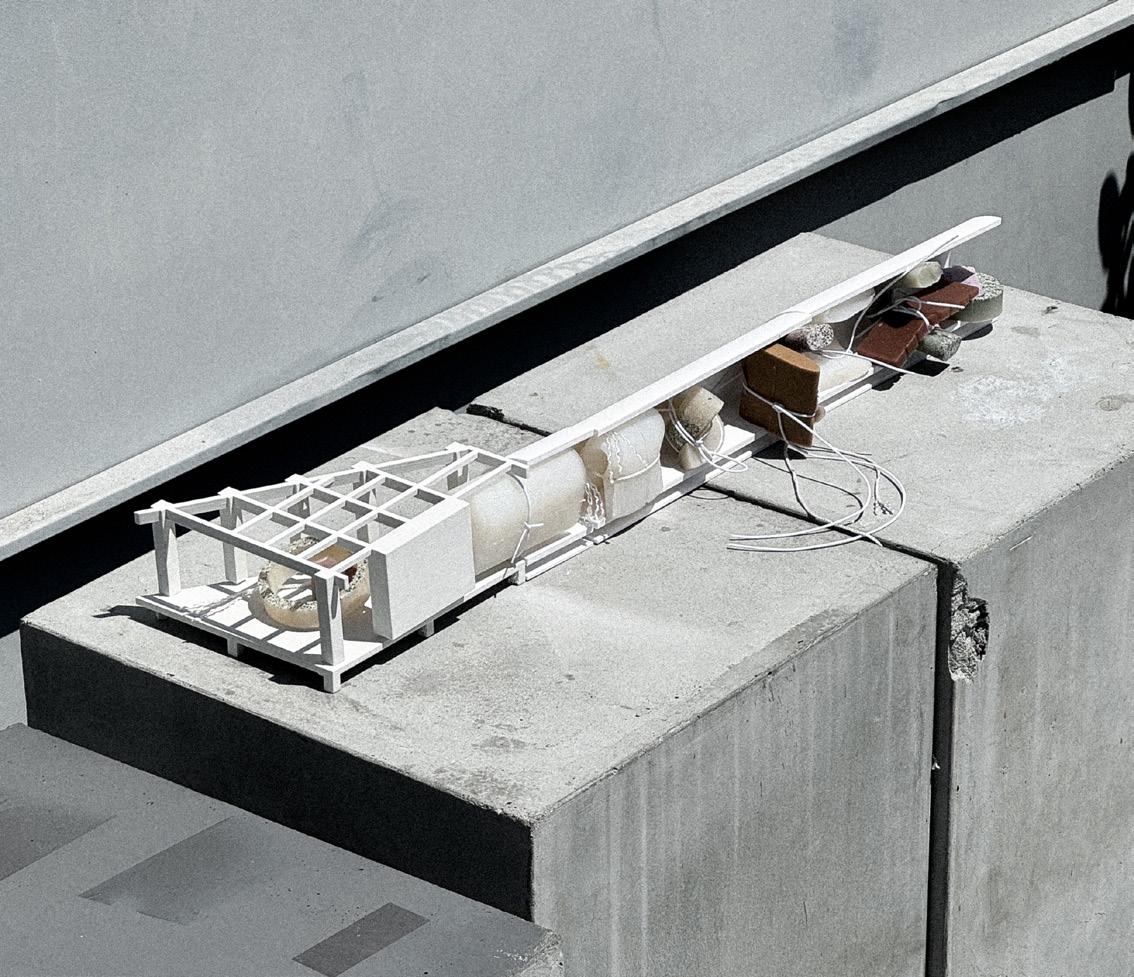

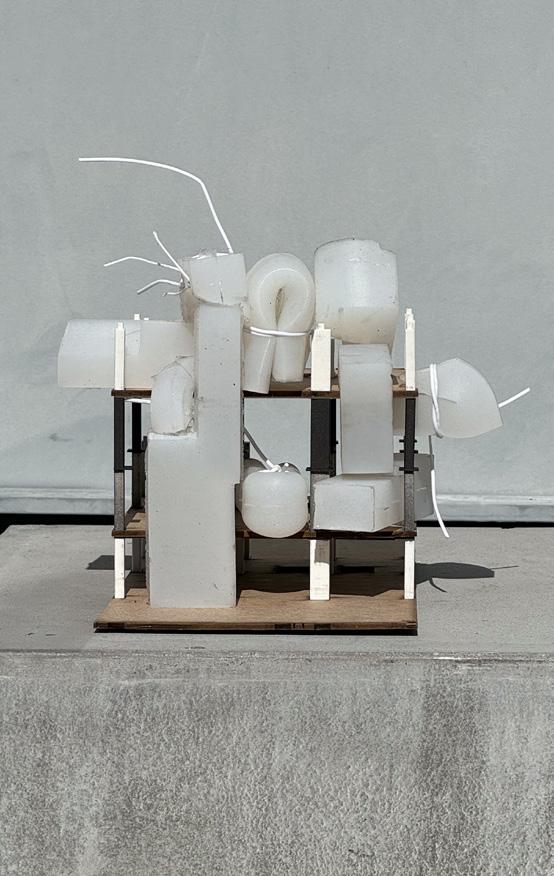

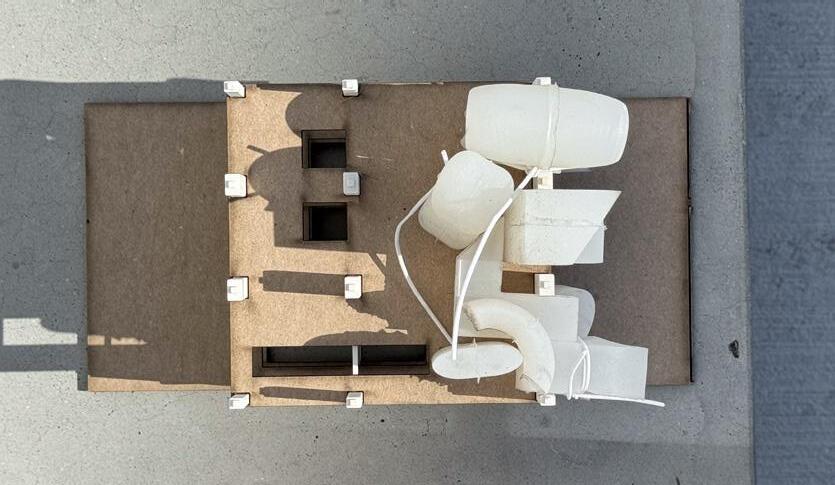

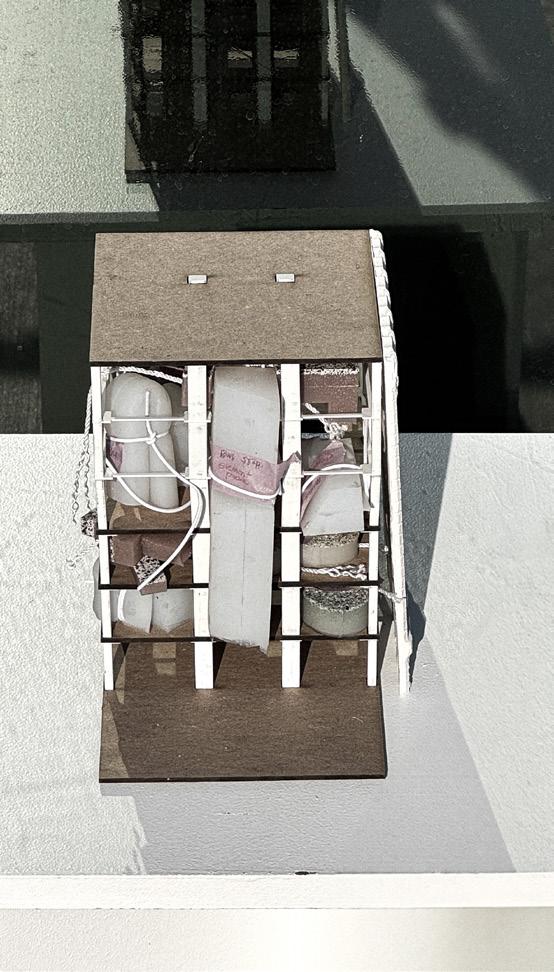

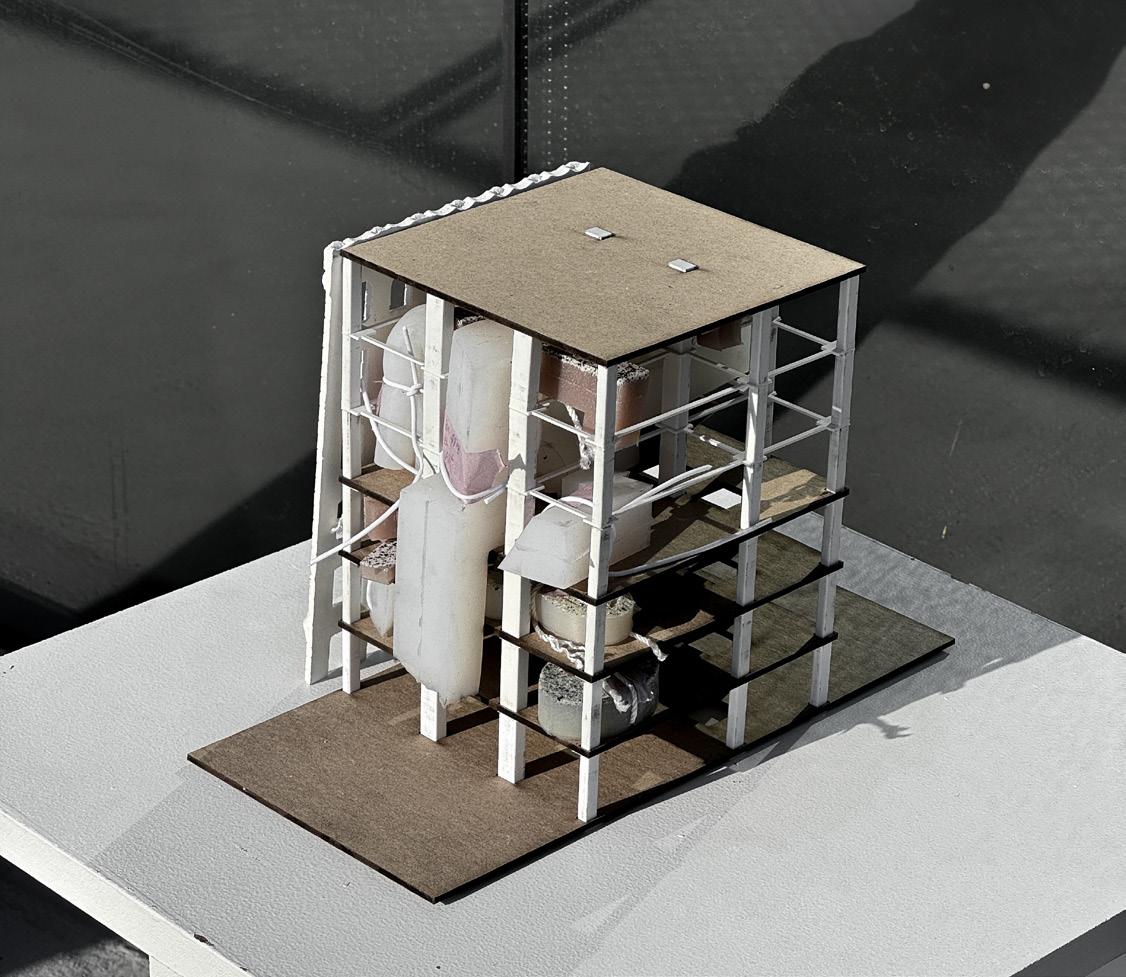

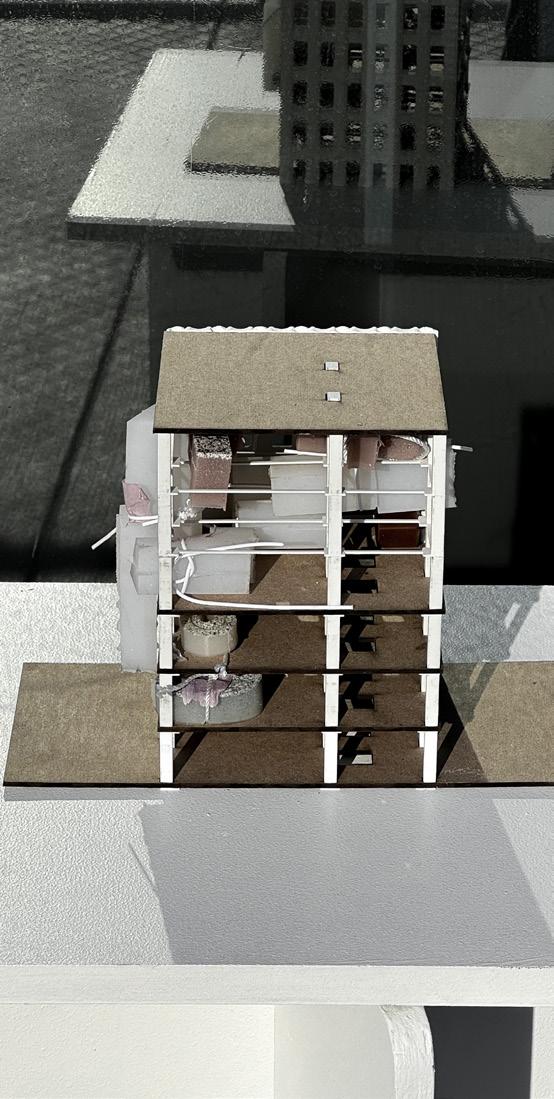

[03_1] Traveling Structure_80

Demount

Build/Unbuild

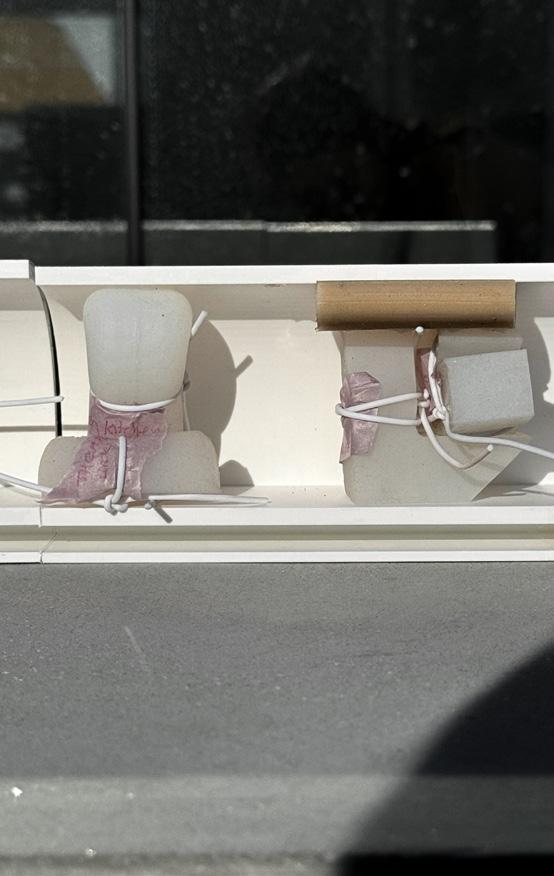

[04_1] Between Certainty and Ephemerality _134

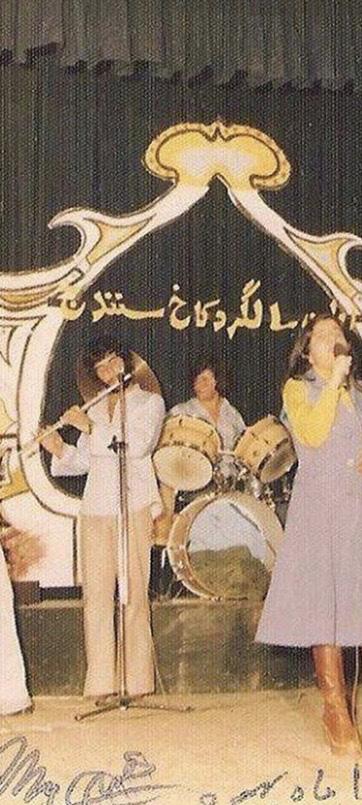

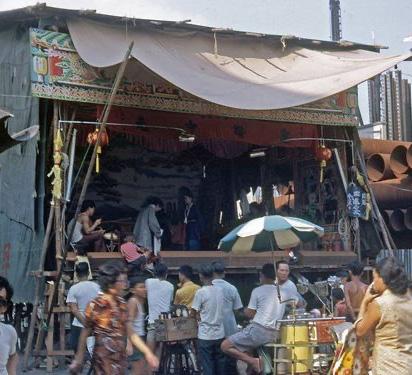

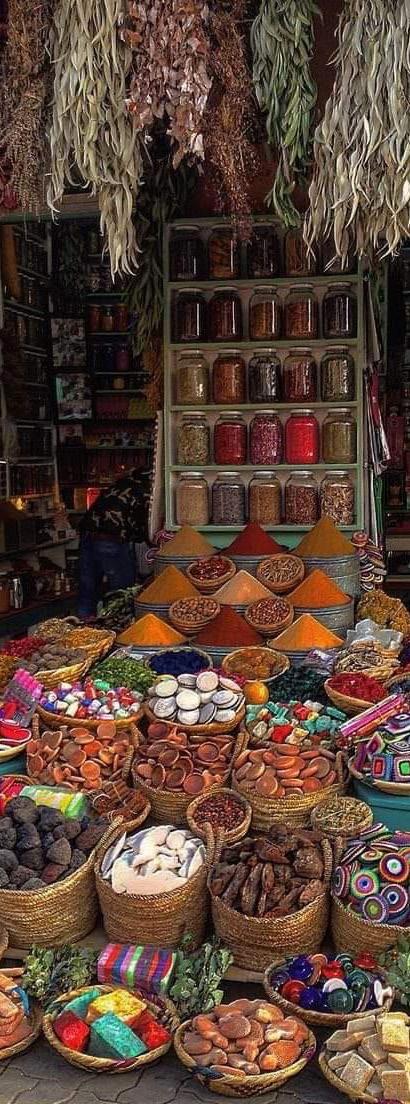

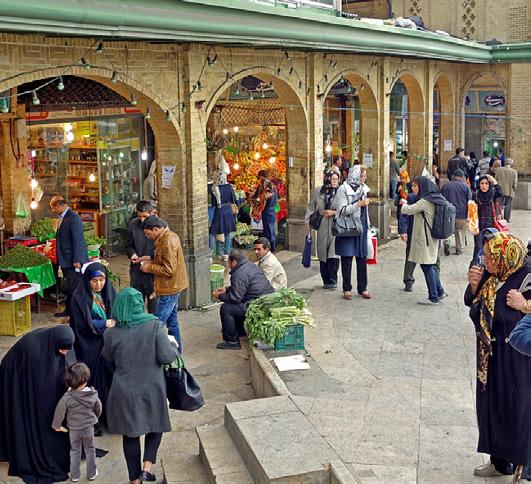

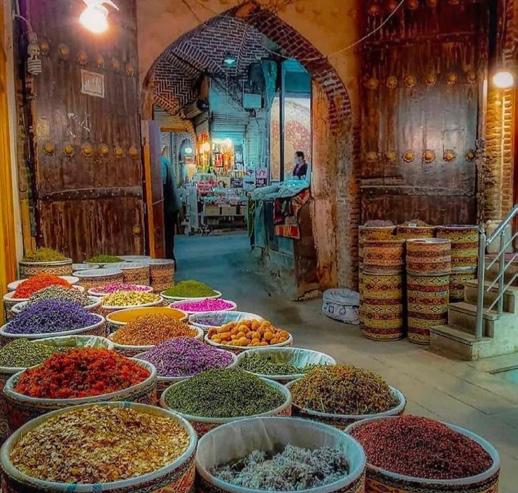

[02_5] Collective Memory Imagery_64

Kitchen Market Restaurant

APPROACH [03]

[03_2] Site_88

Flexible Program Interior Focus

STATEMENT

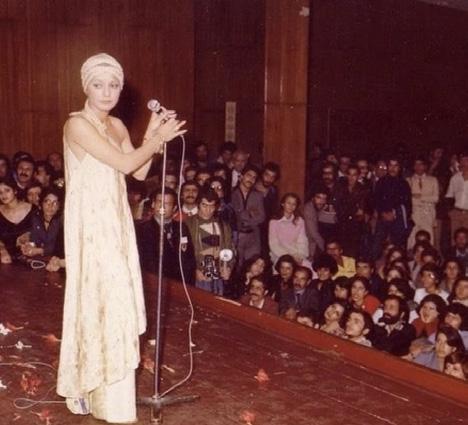

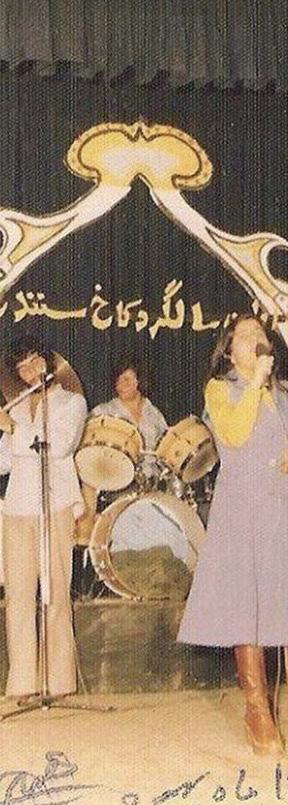

Art institutions such as museums and galleries have long been viewed as monopolizing the world of aesthetics and creative culture, reinforcing a world of privilege and enforcing exclusivity.1 The notion of showcasing art to the public originally occurred post-French Revolution, with governments opening their collections for educational purposes and transforming cabinets of curiosities into public displays. For instance, the Uffizi Gallery is the first public gallery to display The Medici family’s extensive art collection in Florence.2 However, by the late 19th century, these institutions primarily served the privileged class, evolving into systems of meticulously curated art experiences for the masses.3 In the late 20th century, the power shift, with artists and curators publicly criticizing the lack of openness and diversity in the art industry, led to the development of para-institution and anti-institution movements.

“Art museums, in their traditional format, were based on the concept of a universal art history. Accordingly, their curators selected artworks that seemed to be of uni-

1 Carol Duncan, Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums, 1995

2 Andrew McClellan, The Art Museum from Boullée to Bilbao (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008)

3 Dimaggio, P. (1982). Cultural Entrepreneurship in Nineteenth-Century Boston, Part II: The Classification and Framing of American Art.

versal relevance and value. These selective practices, and especially their universalist claims, have been criticized in recent decades in the name of the specific cultural identities that they ignored and even suppressed. We no longer believe in universalist, idealist, transhistorical perspectives and identities.”4

The last two decades have seen a significant evolution in art, as artists increasingly integrate political discourse and diverse cultural perspectives into the galleries. Still, the architecture of galleries remains in the “white cube” context that isolates art from reality and the outside world.

“The essentially religious nature of the white cube is most forcefully expressed by what it does to the humanness of anyone who enters and cooperates with its premises.” as Brian O’Doherty noted. The thesis explores the idea of bringing informal spaces into the gallery context, shifting the white cube context to create more public engagement and conversation, and bringing back the original idea of creating galleries.

[Middle Paragraph Under Develope]

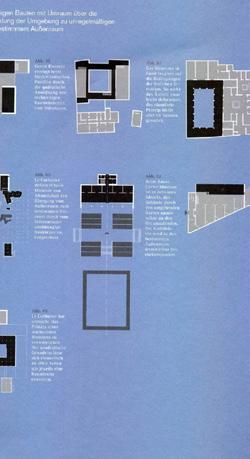

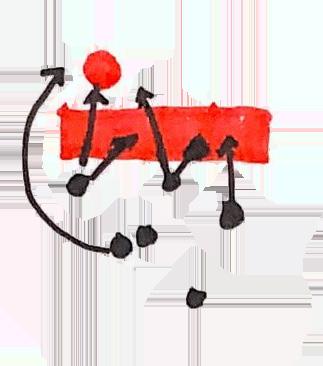

In the ongoing discussion of an alternative form of gallery space, the dissolution of institutional power in a social context is prominent. Alternative spaces to ‘white cubes’ are creations to denounce the manipulation of power and unethical supremacy.5 The project seeks to embody the act of viewing art, reinstating galleries in the context of life and time. Audiences, creators, etc, as a collective body involved in a shared space, hold a sense of common memory from the routine and ritual of life. Through constructing familiar scenarios and translating them to an exhibition framework, this thesis speculates a contemporary alternative to the ‘white cube’ that engages conversation, emotion, and intimacy. The project performs as a temporary structure, adapting to various contexts and geographic conditions, which is crucial in order to have a broader reach to audiences and situate gallery culture in unexpected contexts. The ability to evolve formally gives the project a sense of timelessness in its temporary moments in socioeconomic shifts. The informality of ‘life’ puts gallery space on a scale of closeness and a series of ongoing changes. The interruption of deconstruction and embodiment desensitizes the pureness nature of the ‘white cube.’

[02_1] Reading_08

Inside the White Cube A Brief History Of Curating ......

[02_2] History Timeline_20

Galleries vs Museums Timeline of Galleries

[02_3] Institution Spectrum_34

MOMA The Kitchen Bodium Project

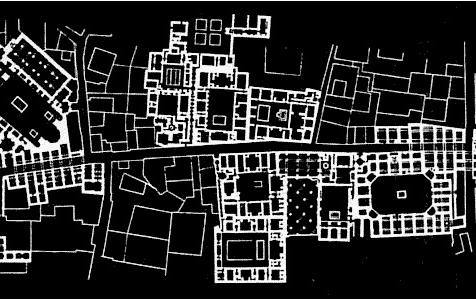

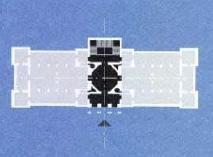

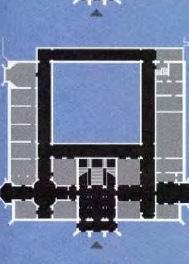

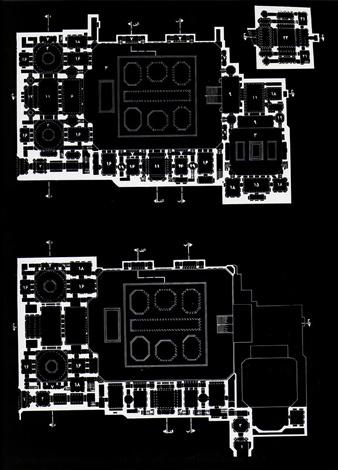

[02_4] Spatial Typology Spectrum_56

Churches ‘White Cube’ Informal Space

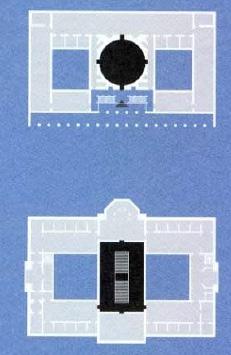

[02_5] Collective Memory Imagery_64

Kitchen Market Restaurant

Hans Ulrich Obrist

A Brief History Of Curating 2008

Hans Ulrich Obrist

INSTITUTION BUREAUCRACY ADAPTABILITY

FREEDOM

HIREACHY

“Furthermore, I did not want most things to be communicated verbally, but rather through architecture.”

-Johannes Cladders

“Somehow, early on I got used to the idea that these people who were exploring any given subject were constantly pushing out beyond the boundaries, in order to understand what the boundaries were in the first place.”

-Walter Hopps

White Wall, Designer Dresses

Mark Wigley

IDEOLOGY SURFACE WHITENESS

MODERNISM

CONTEXT

“Color is seen to emphasize, rather than mask, the pure geometries of both the machine and the new forms it makes available. If modern architecture is the child of the machine age, it would seem to make sense that it is colored like a machine, and

Le Corbusier’s color scheme does resemble that of the engineers”...

... “Just as the architect is not simply an engineer, the building is not simply a machine. The apparent discrepancy between white theory and colored practice remains unaccounted for.”

Brian O’Doherty

ISOLATION RITUAL PURITY

“The ideal gallery subtracts from the artwork all cues that interfere with the fact that it is “art.” The work is isolated from everything that would detract from its own evaluation of itself.”

FORMALISM POWER

“The essentially religious nature of the white cube is most forcefully expressed by what it does to the humanness of anyone who enters and cooperates with its premises.”

Alternative History 2012

Lauren Rosati

Mary Anne Staniszewski

ANTI-INSTITU-

TIONAL

ARTIST-RUN

COMMUNITY

ACTIVISM

GRASSROOTS

“The alternative space is supposed to denounce these manipulations and work on the ethical side of cultural production. The alternative space is the most autonomous method of reinventing intervention.”

“Yet the concept of a movement does imply the creation of communities, common practices, and networks, ...”

Entering the Flow: Museum between Archive and Gesamtkunstwerk

2013

Boris Groys

IMMERSION

DOCUMENT

TIME

ARCHIVE SPECTATORSHIP

“However, in this case, the initial mission of the art museum to resist time and become a medium of mankind’s memory reaches an impasse: if there is a potentially infinite number of identities and memories, the museum dissolves because it is incapable of including all of them.

“We can thus say that the traditional art system is based on desynchronizing the

time

of the

individual, material human existence from the time of its cultural representation.”

Educational and Cultural Institution

Museums primarily

serve as educational and cultural institutions. They are dedicated to the preservation, study, and public display of artifacts, artworks, and etc. Their primary mission is to educate the public, promote cultural heritage, and support scholarly research.

Permanent Collections

Museums often maintain extensive permanent collections that are preserved and displayed for public benefit. These collections can include a wide range of objects, from fine art to natural history specimens and scientific objects.

Non-Profit Institutions

Museums are often non-profit institutions funded by government grants, private donations, and admission fees. Their primary goal is public service and education.

Public Accessibility

Museums are designed to serve a broad audience, including students, scholars, families, and tourists. They often provide educational programs, guided tours, and public lectures.

Community Engagement

Museums focus on community engagement through educational programs, workshops, and collaborations with local organizations. They strive to be inclusive and accessible to diverse audiences.

Permanent Exhibitions

Museums have both permanent exhibitions, which display core collections, and special exhibitions that focus on specific themes, artists, or historical periods. These special exhibitions can be temporary and are often meticulously curated.

Commercial Spaces

Galleries are primarily commercial spaces focused on the exhibition and sale of artworks. They represent artists, organize exhibitions, and facilitate the sale of artworks to collectors, institutions, and the general public.

Temporary Exhibitions

Galleries do not typically maintain permanent collections. Instead, they exhibit artworks on a temporary basis, often changing exhibitions regularly to showcase different artists and styles.

For-Profit Businesses

Galleries operate as for-profit businesses, earning revenue through the sale of artworks and commissions. Their focus is on the art market and commercial success.

Target Audience

Galleries primarily target art collectors, buyers, and enthusiasts. While galleries are open to the public, their primary audience consists of potential buyers and art professionals. Galleries participate in international art fairs like Art Basel and Frieze, which are crucial for networking, sales, and expanding their global reach. These events attract collectors, curators, and art enthusiasts from around the world.

International Art Fairs

Rotating Exhibitions

Galleries regularly rotate their exhibitions, showcasing new artworks and artists to keep their offerings fresh and engaging. These exhibitions are often market-driven, reflecting current trends and the interests of collectors.

14 - 18 C

Religious Collections

Cabinet of Curiosity

Wunderkammern

Salon

18

Enlightenment

Institutional

Public Museums

Art for Public

MUSEUMS

White Cube Era

Artistic Movements

Anti/Para-Institutional Modern Museums

Digital Transformation

Globalization

Community Engagement and Education

14 - 18 C

Private Collections

Cabinet of Curiosity

Wunderkammern

Salon

18 - 19 C

Enlightenment

Institutional

Commercial Gallery

Art for Public

White Cube Era

Artistic Movements

Non-Institutional

Reuse Space

19-20 C

Online Platforms

Globalization

Inclusion

Biennials

21 C

14 - 18 C

Cabinets of curiosities, or “Wunderkammern,” emerged during the Renaissance in the 16th and 17th centuries as eclectic collections of rare and exotic objects, reflecting the era’s burgeoning interest in exploration, science, and art. These private collections, belonging to wealthy individuals, scholars, and nobility, showcased items like natural specimens, cultural artifacts, artworks, and scientific instruments. During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, private collections, known as “galleries” or “cabinets,” were common among European aristocrats and wealthy merchants. These collections often included paintings, sculptures, and other artworks displayed in private residences and palaces. The Medici family in Florence, for instance, was known for their extensive art collection, which was later opened to the public and became the basis for the Uffizi Gallery. Notable collectors included Ole Worm, Athanasius Kircher, and Emperor Rudolf II. These cabinets laid the groundwork for systematic scientific inquiry by gathering specimens from around the globe, promoting a hands-on approach to learning. They became central to intellectual life, hosting scholars and artists who studied and debated their contents. Over time, these collections were cataloged and studied more systematically, contributing significantly to the Enlightenment’s empirical methods and the professionalization of scientific disciplines. Simultaneously, salons emerged as significant cultural and intellectual gatherings during the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly in France. Hosted by influential women, known as salonnières, these social assemblies became hubs of intellectual exchange where writers,

artists, philosophers, and scientists discussed literature, art, science, and politics. Prominent salonnières like Madame de Rambouillet and Madame Geoffrin attracted figures such as Voltaire and Rousseau. Salons were instrumental in spreading Enlightenment ideas, fostering critical discussions, and shaping public opinion. Unlike cabinets of curiosities, which focused on the collection of physical objects, salons emphasized the exchange of ideas and played a crucial role in advancing intellectual and cultural movements, contributing to early feminist thought and challenging traditional gender roles.

14 - 18 C

Private Collections

Cabinet of Curiosity

Wunderkammern

Salon

18 - 19 C

19-20 C

21 C

18th C

The 18th century marked the birth of the modern commercial art gallery, transitioning from private aristocratic collections to more public and accessible spaces for exhibiting and selling artworks. This era saw the rise of significant venues like the Salon de Paris, which evolved into an influential public exhibition, and the establishment of early galleries in London by art dealers who catered to the growing middle class’s interest in art. Notable examples include Thomas Coram’s Foundling Hospital art gallery, which provided a public platform for artists like William Hogarth. These developments set the stage for the later proliferation and professionalization of art galleries in the 19th century.

19th C , 1800 - 1850

19th C , 1850 - 1900

their work, reach new audiences, and establish their reputations. The development of artist-dealer relationships, where galleries would represent and promote specific artists, became pivotal for movements like Impressionism. Dealers such as Durand-Ruel championed the works of artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, organizing exhibitions and marketing their art to collectors. This period marked the beginning of the commercialization of art, creating a dynamic market where artworks could be bought and sold, and laying the groundwork for the modern gallery system.

The 19th century witnessed the proliferation and professionalization of art galleries, especially in major cities like Paris, London, and New York. In Paris, galleries such as Goupil & Cie, founded in 1829, became influential players in the international art market, representing artists and popularizing their work through exhibitions and print publications. The Royal Academy of Arts in London, with its annual exhibitions, inspired the opening of numerous commercial galleries. The presence of international dealers like Paul Durand-Ruel, who promoted Impressionist artists, further expanded the art market’s reach and influence. In New York, galleries like Knoedler & Co., founded in 1846, played a crucial role in introducing European art to American collectors, shaping the American art market. The rise of these galleries significantly impacted the art market and artistic movements. They provided artists with platforms to exhibit

Enlightenment

Institutional

Commercial

Mid - Late 20th C

The mid to late 20th century saw the significant expansion and institutionalization of art galleries, particularly in New York with movements like Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. Prominent galleries such as Betty Parsons Gallery and Leo Castelli Gallery promoted key artists like Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol, while influential curators like Walter Hopps and spaces like Peggy Guggenheim’s museum-gallery played vital roles. This era also marked the rise of global commercial galleries like Gagosian and Hauser & Wirth. The White Cube aesthetic, popularized in the 1960s by critic Brian O’Doherty, introduced minimalist gallery spaces with white walls, significantly influencing exhibition practices and gallery design. The period also saw the rise of Conceptual and Installation Art, accommodating artists like Sol LeWitt and Joseph Beuys. The feminist art movement, with figures like Judy Chicago and the Guerrilla Girls, advocated for gender equality and representation in art. The advent of digital technologies and the internet transformed galleries, enabling global reach through online promotions and virtual exhibitions. The globalization of the art market increased collaboration and competition, with international art fairs like Art Basel and Frieze becoming major events, and emerging markets in Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America diversifying gallery practices. Influential artists like Claes Oldenburg expanded the scope of gallery exhibitions with large-scale public art installations.

Early 20th C

The early 20th century was a transformative period for art galleries, marked by the rise of modern art movements such as Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism, and Surrealism. These movements challenged traditional aesthetics and were promoted by pioneering galleries and dealers. In Paris, galleries like Galerie Bernheim-Jeune showcased Fauvist artists, while Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler promoted Cubists like Picasso. In New York, Alfred Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 was pivotal in introducing modern European and American artists. The 1913 Armory Show in New York was particularly significant, as it introduced European modernism to the American public, profoundly influencing the art scene in the United States.

White Cube Era

Artistic Movements

Non-Institutional Reuse Space

21st C

The 21st century has transformed art galleries through digital technology, globalization, and a focus on diversity and sustainability. Online platforms like Artsy and social media have enabled global reach and virtual exhibitions, especially vital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Major galleries have expanded into international markets, fostering cross-cultural exchange. There is a stronger emphasis on representing diverse artists, addressing social issues, and promoting dialogue. Galleries are adopting sustainable practices and ethical standards, including fair compensation for artists and responsible sourcing. Innovative exhibition spaces and technology-driven art have emerged, creating unique viewer experiences. Community engagement and accessibility are also prioritized through educational programs and local collaborations. Art fairs and biennials, such as Art Basel and Frieze, play significant roles in the global art market. These events attract collectors, curators, and art enthusiasts from around the world, offering galleries crucial platforms to showcase their artists and foster international connections. These developments reflect the evolving art world’s efforts to remain accessible, engaging, and relevant in contemporary society.

- 18 C

- 19 C 19-20 C 21 C Online Platforms Globalization Inclusion Biennials

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s earliest roots date back to 1866 in Paris, France, when a group of Americans agreed to create a “national institution and gallery of art” to bring art and art education to the American people.

1929 International

The Museum of Modern Art is the world’s preeminent institution dedicated to the art of our time.