geoff uglow

beyond the clouds

uglow beyond the clouds

august 2024

uglow beyond the clouds

august 2024

Uglow writes of how he is fulfilled by the physical exigencies of working with oil paint. This may derive from his upbringing on a Cornish farm, where he was a horticulturalist and painter. In Beyond The Clouds he reviews his formative years working in Edinburgh, applying the sophistication garnered in the Roman Campagna to readdress his subject led now by atmosphere, by the happenstance of how a particular morning light falls on familiar stone. It is the third state he seeks: from the solidity of the observed architecture, through the fluidity of his medium, to the atmosphere created. Order can only emerge from chaos, from the imposition of human will onto the apparent disorder of nature. Uglow recognises the solace and virtue in the Roman garden, in our requirement for a place of peace and contemplation and in Cornwall he has created a rose garden, a Monet-derived locus of thorn and bloom which is at once sanctuary and wilderness, a paradigm of both man’s interaction with nature and the painter’s need for an order which represents the process of regeneration, of life and death.

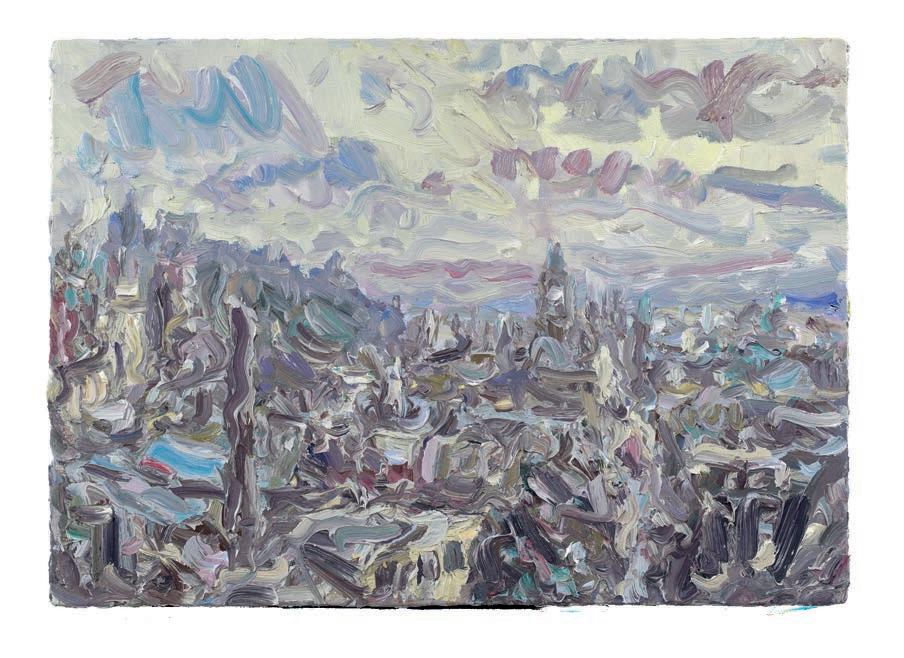

In 2024, I painted from Observatory House, which is a magnificent 18th century building on top of Calton Hill. It was designed and once inhabited by the New Town architect James Craig and is one of the best surviving examples of Craig’s architecture. Although it was originally built as a family house, the building was at one point used by astronomers for a short period of time until the famous William Playfair built the City Observatory building nearby in 1818. I also painted from a large rock in front of The Nelson Monument.

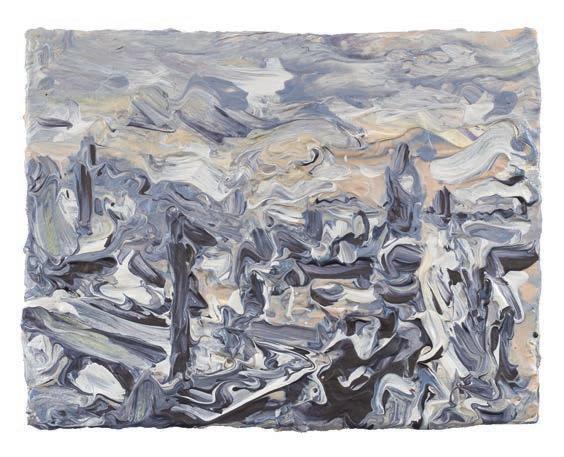

I see the body of the city as delicate. To the east you see Arthur’s Seat and the Salisbury Crags – brooding occupants. Black. Impenetrable. By comparison the city is the opposite. On the ground level and as you move through it, it feels strong and resistant, but when observing it afar, from an elevated position, the image of it flutters and renews every moment. It’s full of space and glass and reflection.

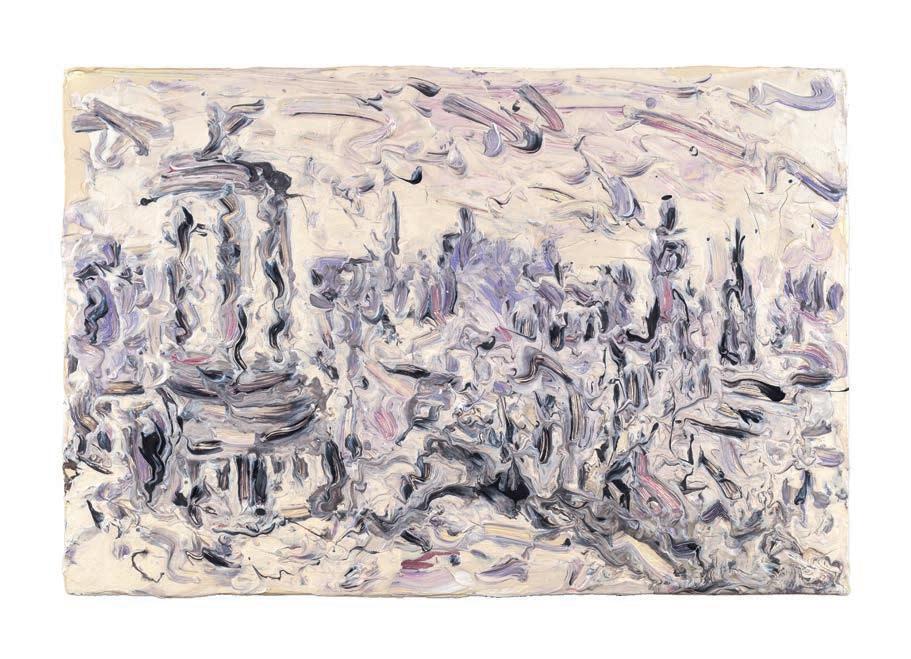

An essential component of the city is the people that inhabit it. The living, breathing creatures within it and the fluctuating light and air that moves and animates the space between the stones. I think about those great civilisations of the world that have risen and fallen and changed… nothing is permanent. A city is changing and adjusting continuously, and I feel this renders its parts to be fragile. This is why I chose to paint Edinburgh with liquid fluidity and with a sense of sway in the marks. This can be

seen in both the older and newer works, but it is the viscosity of the paint that has changed. Recent consistency is less dense and flows more gracefully.

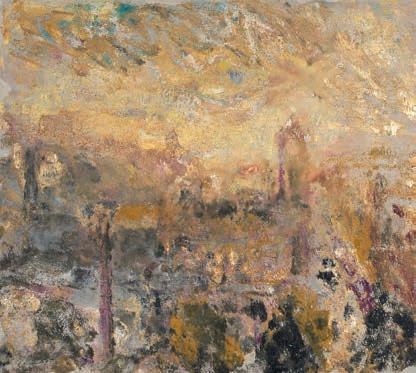

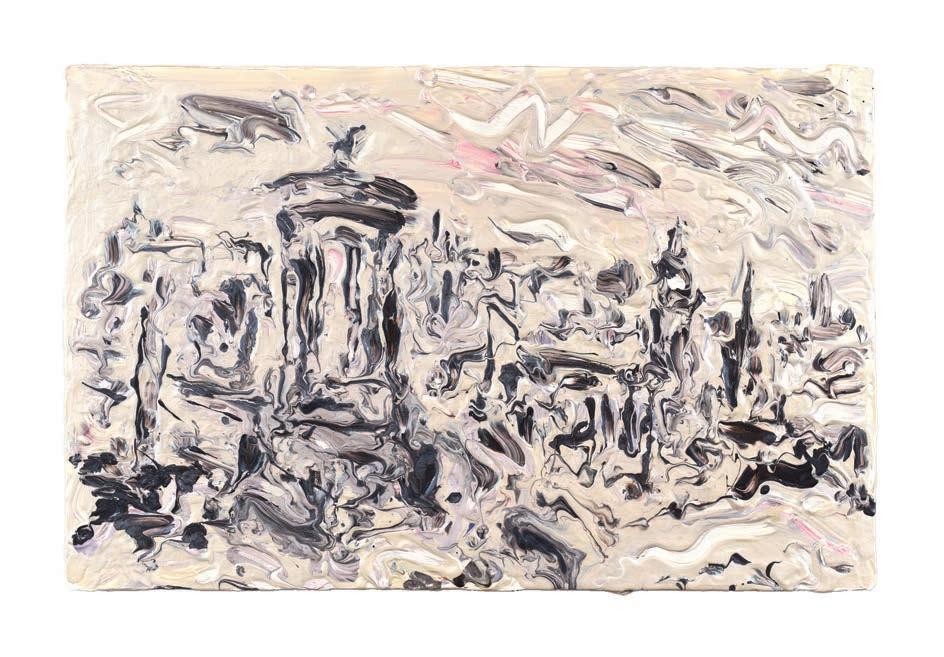

When I look at certain older paintings of mine, they seem to me to be like rocks you might stumble across when out hillwalking – brawny and weathered and full of age-old grit with the traces of a geological record patterned across them. And the colours are sturdy and sincere, like those seen in the local sandstone or dolerite. On the contrary, the drawing in a new painting is open, dissolved… with space and light surfacing from behind and between the marks. The palette is ethereal by comparison evoking moods of transcendence and contemplation. When considering painting the city of Edinburgh now, I’m interested in eternal notions of its existence - the poetry of the subject – but not how many chimney pots I must be sure to include in the rendering of a certain roof.

Physically my paintings are heavy with materials, so I like the image within them to appear weightless in opposition of that. My current paintings of Edinburgh focus more on a viewpoint of the city as a person… a character, or a feeling. I’m searching for a sound or a song… a voice. I aim to draw out emotive colour and mark from what I sense in the cityscape and I try to allow that vernacular to freely surrender itself onto the picture plane.

In 2002 the subject itself, the city of Edinburgh, dominated me. Understandably. It was the great capital city and I was not long out of art school. I think perhaps I felt a certain sense of duty to paint Edinburgh with some degree of geographical truth and integrity. At the time, I had less actual painting experience than I have now and so it was helpful for me to use those re-assuring structural features to support the compositions of my paintings. Using that method was advantageous at the time. Topography and architecture gave me the confidence to access the subject and initiate a journey of exploration. I could freely test out ways of describing what I was looking at, knowing that I had laid down a strong compositional bedrock to begin with and

that the overall image would maintain a satisfying unity. It was a determined process of discovering and tying down and I do see that there was serious intention there.

Uglow’s repeated assessments about the relationship of light and shade, form and space, let him move towards the balance and unity that he wants. He works wet on wet, wet on dry and is very aware that pace and the changes of pace shape the final feel of the painting. Such repetition inevitably results in a quality of pigment he obviously relishes. He believes it is continuity with the past that makes the present so fertile and his work is grounded on that premise. Robin Hume, 2002

In 2007 I spent several years living in Italy and my interests and experience expanded exponentially. I was painting the ancient city of Rome and the surrounding countryside and it was full of ruins. Ruins everywhere. Ruined cities and towns and villages. Ruins of ancient monuments, amphitheatres, architecture, artefacts and sculpture… Even a supercivilisation like the Roman Empire had fallen to ruins. And so, an invincible heroism, which I had perceived in the city early on, lost its authority over my drawing and composition with this exposure to the ruins. A lot of time was spent painting things that were broken. Fragmented. Come apart. It had a profound effect on my approach to painting the subject of the cityscape. A more personal response toward my subject entered into the work from this point. A city became a hook on which to hang the light of a time of day, or a memory or mood. The methods I employ now are more in line with this.

I do not place a grid. There is no under-pinning framework. Not allowing any mark or image to be pinned down is my aim… I want marks to appear to be in suspension, opening or circulating. I’m taking away things that feel solid or fixed… I’m letting go of hard edges. I omit restrictive architectonic drawing and instead loosen every part of the painting. Topography, even gravity, is not a concern. If painting a place, I aim to channel into each piece all the depth of personal understanding I have of that place, both from the experience and the memory of it, as well as what my eye observes in the moment. All the lines in my paintings curve… there are few straight lines.

Calton Hill has always been the most informative vantage point from which to view the city. It presents extensive views by which its history can be appreciated. I spent six months in the tower and often slept there, painting the city at night. The period spent in The Nelson Monument in 2007 was the lengthiest and most intensive I’ve spent so far.

It is characteristic of him to seek a location redolent of an historic past and graced with the footprint of previous artists. On offer from this elevated panorama of skyline are, on one side Arthur’s Seat and parliament buildings, on the other the Forth and Leith. In between lie great swathes of city texture, old and new, variegated by time and weather. The paintings reiterate his engagement with oil paint and they exalt its fluidity and adaptability in pace and application. This medium allows sustained assessment and reassessment of the depth of the space, or the luminosity of a particular light and how it falls on specific patterns of stone, fenestration and foliage. As in any good portrait, likeness, while important becomes meaningless without sentience, so in these cityscapes itemisation of topographical detail is subsumed within the search for some sort of quiddity.

Robin Hume, 2007

By studying Edinburgh’s natural topography as it is today, geologists have some understanding of the dynamic movements of magma, and the flow of glaciers that formed it. The landscape was, far back in its prehistory, in a state of flux. There was lava intrusion deep underground which rose up and spread out horizontally, finding its way between existing rock. The igneous rocks of the city and the surrounding area crystallised from liquid magma into solid after being pushed and pulled by various pressures and forces, the arrangements and shapes of which were then left to cool and set solid. I think of the development of my paintings as going through a similar journey. The curious merging of medium, illusion and emotion that come as a result of the interplay between me and my subject is captured in the flow of the liquid paint. It’s pushed and pulled by the force and pressure of my energy and my brush and at some chosen point, left to harden in the air. Emotion and meaning can be deciphered by reading the pace and patterns of the heaped-up dry paint.

I have used names of past Edinburgh inhabitants as titles for my paintings. It was in 2007, I took a walk one day through the Old Calton Burial Ground and found them waiting for me.

The sounds of the names themselves are beautiful and thought-provoking. Like when reading the first line of a novel or poem, they stir up feelings and impressions. So many of the names I came across exude an expression of Romanticism. That was the dominating artistic movement at the time when the cemetery was opened in 1718.

By definition, a city is an area of land where a large number of people live near to one another. Everything else grows from this. The people who have lived in a place are what define it. It seemed right that the names of those people might be respectfully adopted to live alongside the painted impressions.

It’s interesting to note that many roses have been named after people too; it is a similar use of metaphor.

The monument for the lost ones. Dried veins. Paths of soil. I carry this gaze. You the crags. Narrow twisted, winding stair. Within the tower. Leads me above. Beyond the clouds. Geoff Uglow 24/04/24

18 Monument for the Lost Ones, 2024 oil on board, 40 x 60 cm

Everything flows. Nothing stays the same. - Heraclitus

I continue to tend to the garden, and it continues to grow. I’ve introduced more of my own roses. The cycle goes on but every year different things are happening - one variety will dominate while another dies back. It’s about renewal. I re-iterate what I’ve suggested in the past, which is that making paintings is very like cultivating a garden. A garden is never ‘finished’. You accept it for what it is at every stage of its development. You work and toil, then rest and contemplate, then get up and begin again. Over and over and over; it’s the same cultivating my studio practice and my painting oeuvre.

The spirit of the garden changes from moment to moment depending on the light and season. There is a clear parallel here: changing light, atmosphere and season affect the spirit of a garden landscape in the same way it might affect a person’s inward, emotional landscape. Rising and falling mood are perceptible and palpable in both. From the time a seed germinates it goes through a great number of physiological processes. When a garden is dormant during winter rest, everything is quiet, and the roses are stripped like old bones. They conserve their energy until suddenly in the spring, movement is hyperactive again and the garden is temporarily full of new growth and colour. You want to pause the activity because it changes so quickly, but you can’t. You become very aware of the effects of time and the impermanence of everything.

In summer the house is surrounded by a great duvet of roses, right up to the windows, with layers and levels of texture and colour. Even a

modest garden displays the profound, circular course of nature which is life, death and renewal. What is revealed in the life of a rose is similarly evident in the life of mankind. We nourish ourselves physically as well as emotionally and spiritually. We grow. Periodically we are pruned and coppiced by life, which will either end us or stimulate new growth. And we perish. But in most cases not without leaving behind the fruit of the seed, which is the next generation, that will carry on the cycle.

A rose is not just a rose. Every rose has an origin, a history, a breeder and a habit in its process of maturation. Some have bewildering blooms but weak growth; others are remarkably vigorous but lack scent. When breeding roses, I know the majority won’t be spectacular, but there is nevertheless a small possibility of creating an exceptional beauty one day. So, you have to be involved…devoted. Painting is no different. You have to work at the relationship to yield a good harvest. It’s good to be the gardener. It’s good to taste the soil and feel it in your hands. It’ll tell you whether it’s rich and happy, or not, and when the soil is managed well, then usually the growth, which becomes the colour, takes care of itself. I believe that if you go to the pains of extracting pigment from the ground, and crush it to a powder and mix it with oil in order to paint with it, you will have a much deeper and more authentic connection with the process and with your painting. Painting, gardening - it’s all the same thing. It’s about taking the time to care. Nourishing the potential.

I think about the ancient gardens of Rome or Pompeii a great deal. They did their growing in a hortus (a garden enclosure) or a peristylium (an open courtyard within the house) and painted murals on the walls of their homes. They created a haven of home life and flowers and art. It was the same at Monet’s residence, and it’s like that at my own studio too. It’s an enclosed paradise full of paintings and plants which put worldly strife and drudgery in its place. This sort of environment focuses the attention on matters conducive to creativity. Living and working within a garden setting, one can assimilate notions of temporal and eternal beauty, as well as the peace and respite experienced through simple contemplation of the universe and its eternal truths.

1997-2000 B.A. Hons (First Class), Fine Art; Painting, Glasgow School of Art

1996–97 Foundation (Distinction), Falmouth School of Art

selected solo exhibitions

2024 Beyond the Clouds, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

2023 Chorus, Tsivrikos Shake, London

2022 The Ploughman, The Scottish Gallery

2019 Era di Marzo, John Cabot University, Rome

2017 The Rose Garden, Vol 1, MMXVI, The Scottish Gallery

2016 A Room of Small Paintings, The Scottish Gallery

2015 MMXIV, Connaught Brown, London

2014 Next Year’s Buds, The Last Year’s Seed, The Scottish Gallery

2013 Quercus Robur, Connaught Brown

2012 Quercus Robur, Beck and Eggeling, Dusseldorf

Connaught Brown awards and residencies

2015 Royal Scottish Academy Award, RSA Open

2009 Alastair Salvesen Painting and Travel Scholarship, Royal Scottish Academy

2002-04 Sainsbury Scholarship, The British School at Rome

2002 John Murray Thomson Award

RAS N S Macfarlane Charitable Trust Award

2001 David Cargill Award

2011 Letters from Barra, The Scottish Gallery

2010 Coda, Connaught Brown

Coda, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

2008 Fathom, Connaught Brown

2007 Being Here Now, The Edinburgh Gallery, Edinburgh

2006 Roger Billcliffe Gallery, Glasgow

Roman Landscapes, The Edinburgh Gallery

2005 Spent Light, The Edinburgh Gallery

2002 Nor Loch Veiled, The Edinburgh Gallery

2001 Recent Paintings, Roger Billcliffe Gallery

Florence, The Edinburgh Gallery, Edinburgh

1999 Guyana Paintings, Assembly Gallery, Glasgow

2000 The John Cunningham Award

James Torrance Memorial Award

The Murdoch Gibbons Postgraduate Prize

The McKendrick Scholarship

Royal Scottish Academy Landscape Award

1998 Armour Painting Prize

Published by The Scottish Gallery to coincide with the exhibition:

Geoff Uglow

Beyond the Clouds August 2024

Exhibition can be viewed online at: scottish-gallery.co.uk/geoffuglow

ISBN: 978 1 912900 862

Designed and produced by The Scottish Gallery

All rights reserved. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced in any form by print, photocopy or by any other means, without the permission of the copyrightholders and of the publishers.