J.D. FERGUSSON

Fergusson with his sculpture, The Patient Woman, c.1930 Courtesy of Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries

Fergusson with his sculpture, The Patient Woman, c.1930 Courtesy of Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of one of Scotland’s greatest artists, John Duncan Fergusson. He was an exceptionally gifted man with an uncompromising vision of what it meant to be an artist: emotional truth was paramount. Free from the constraints of academic tradition or the conventions of bourgeois life, he was a man for whom his work was his manifesto and wide intellectual engagement was the basis for his art.

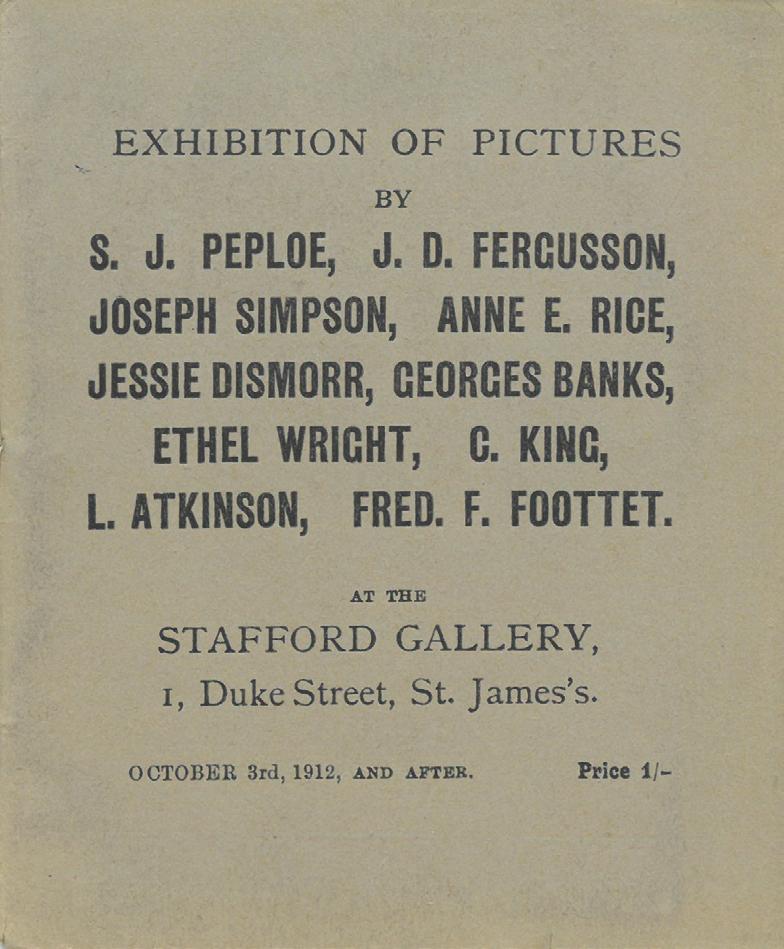

Born in Leith in Edinburgh, J.D. Fergusson’s studies took him to Paris in the 1890s where he attended the Académie Colarossi and made broad connections in avant-garde life. He exhibited in London in 1905 and finally settled in Paris in 1907 where he experimented with Fauvist and Cubist styles, became a Sociétaire of the Salon d’Automne and acquaintance of many of the leading figures in the movement, including Picasso and Braque. He had four works exhibited in Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition in London, 1913. He lived between France and Britain, eventually settling in

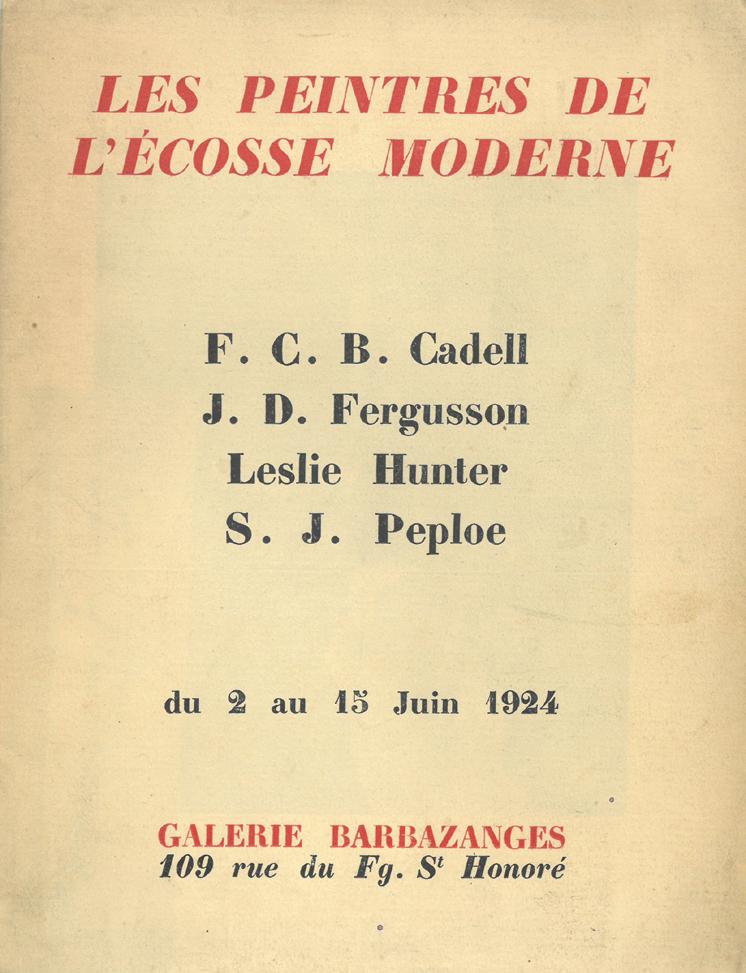

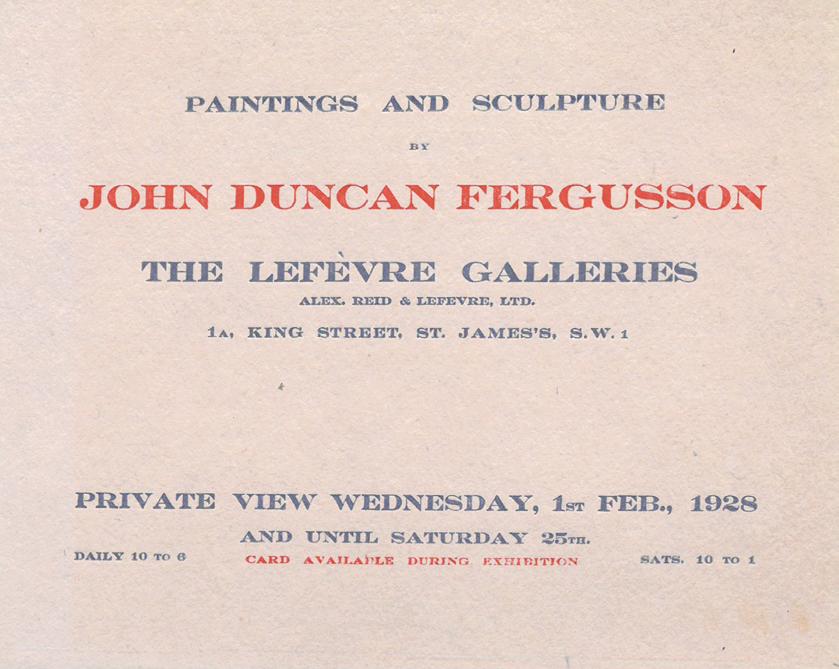

Glasgow with his life partner and the pioneering dancer Margaret Morris. His first solo show in Scotland was held at The Scottish Gallery in 1923 which was followed by an exhibition with the three other Scottish Colourists: Peploe, Cadell and Hunter.

As we pay tribute to the artist and his legacy, we include a group of Fergusson’s drawings and sculpture. These are previously unseen works which are typically economical, direct and true to the moment; free from affectation – they are the exercise of the artist’s instinct and overriding interest in form, character and joie de vivre. There are several bronze sculptures and a rare group of hand-painted plaster studies.

We are honoured to include the voice of Roger Billcliffe, trustee of the J.D. Fergusson Art Foundation, who has written the following essay A Scotsman in Paris.

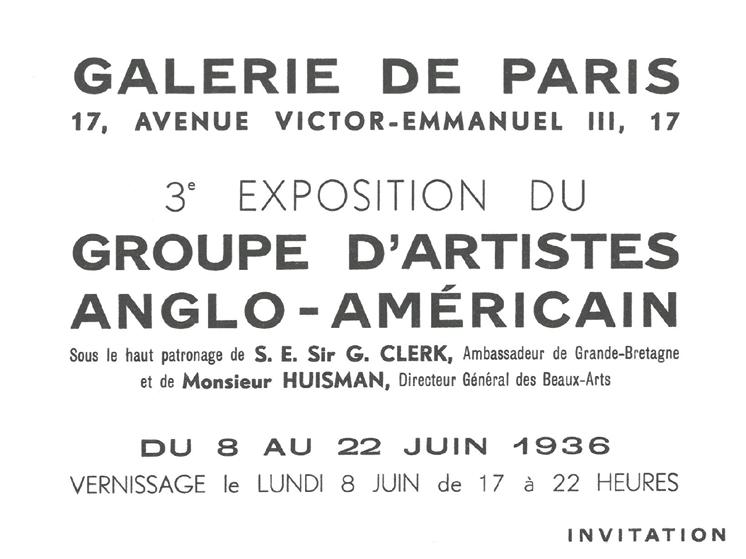

The Scottish Gallery

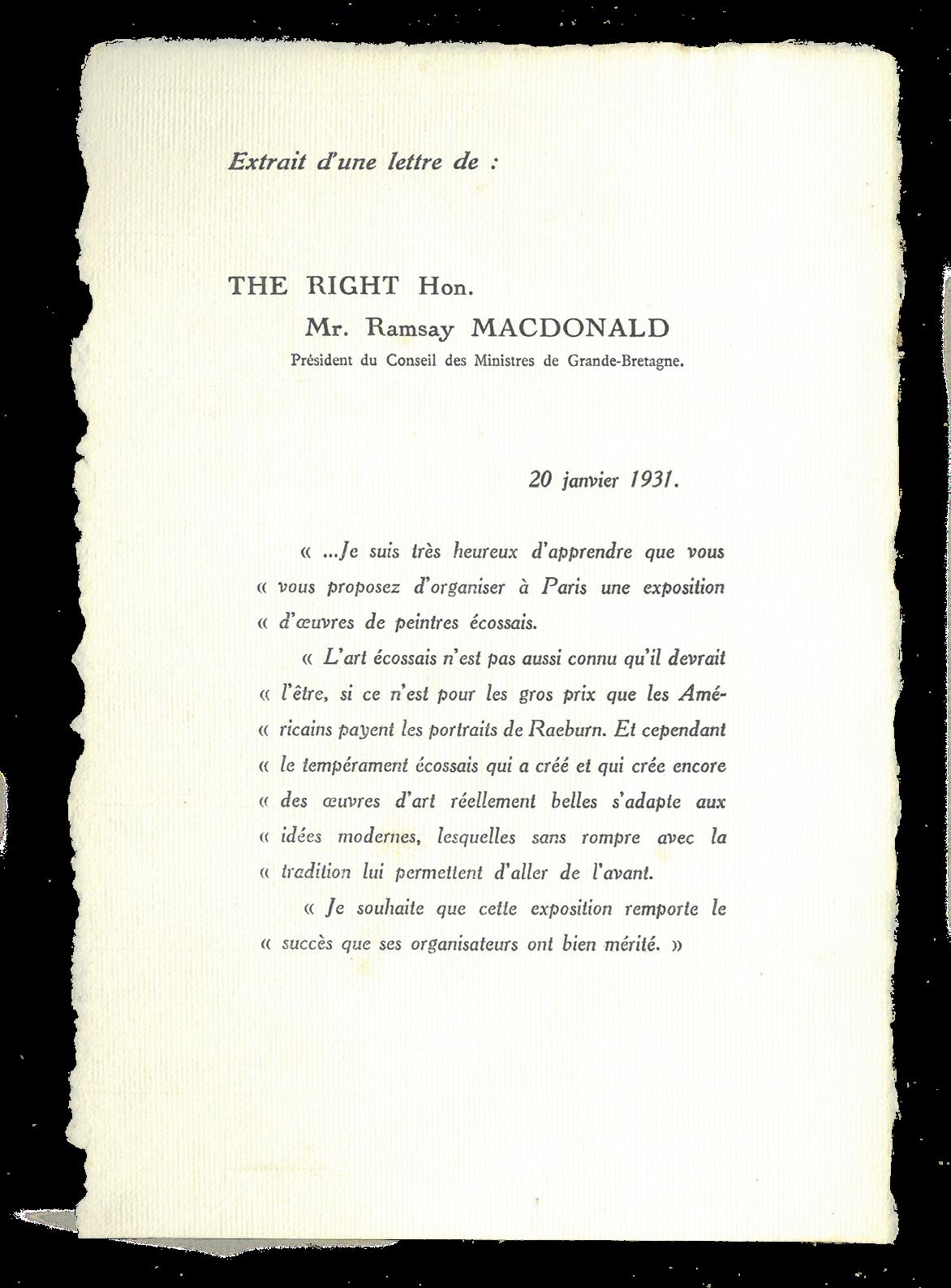

… I am very happy to learn that you intend to organise an exhibition of works by Scottish painters in Paris.

Scottish Painting is not as well known as it should be, except for the high prices that Americans will pay for Raeburn portraits. And yet the Scottish temperament, which has created and still continues to create truly beautiful works of art, has adapted to modern ideas without breaking from the tradition that has allowed themselves to move forward.

I hope that this exhibition enjoyed the success that its organisers deserve.

Fergusson in his Paris studio, c.1910

Courtesy of Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries

Fergusson in his Paris studio, c.1910

Courtesy of Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries

In 1907, the 33-year-old John Duncan Fergusson arrived in Paris from Edinburgh in search of a studio. He found one in the Boulevard Edgar Quinet in Montparnasse, a quartier which had usurped the louche reputation of Montmartre as the destination for painters, sculptors, dancers, writers and musicians. Paris was an artistic and international maelstrom, where not being French was no disadvantage for an aspiring artist–Picasso, Gris, Modigliani, Chagall were just a few of the émigrés who settled in the city. There was also soon to be a coterie of British and American artists – including Jessie King and her husband E.A. Taylor, Jessica Dismorr, Anne Estelle Rice, and Fergusson’s Edinburgh friend S.J. Peploe – who seemed to find in Fergusson a natural spokesman, even leader.

Outwardly Fergusson seems not to have shared the outré lives of his continental neighbours. The three-piece tweed suit that he had worn on the beach at Paris-Plage in 1905 was still his habitual painting garb although the tie was now occasionally of the bow variety. His loyal supporter, the critic Frank Rutter, wrote of him in The Studio in 1912 while keenly interested in every serious new art movement, his racial hard-headedness has not allowed him to be swept hastily into a vortex. Cool and collected, he has watched the currents of contemporary painting, too wise to permit his personality to be sucked and drowned in any one stream. In his foreword in the catalogue of Fergusson’s first American show in 1926, Charles MacArthur wrote that it was so much easier to introduce Fergusson to his New York audience while he was still in Europe: There is no telling how it would be accomplished with Fergusson around. He is one of those dour, wind-blown Scots – at least three parts granite…. Such as Fergusson despise the gab and grimaces so necessary to further acquaintance…. He is as

blunt and straightforward as his work, and the only person who can tell him anything is a man named Fergusson.

Despite this inability, or reluctance, to soften his Scottish persona Fergusson quickly adopted some French habits. One could say that his move to Paris in 1907 was hastened by his meeting with a young American woman the previous year, on a short visit to Paris-Plage or possibly Paris. This was Anne-Estelle Rice, and they became lovers soon after Fergusson’s arrival in Paris, where Rice already had a studio in Montparnasse. For the next six years their work developed in tandem, each taking the advantage or lead in turn as they reacted to the vitality of life in Paris and the social, artistic, philosophical and political chatter of the cafés, restaurants, music-halls and theatres that was their life outside the studio.

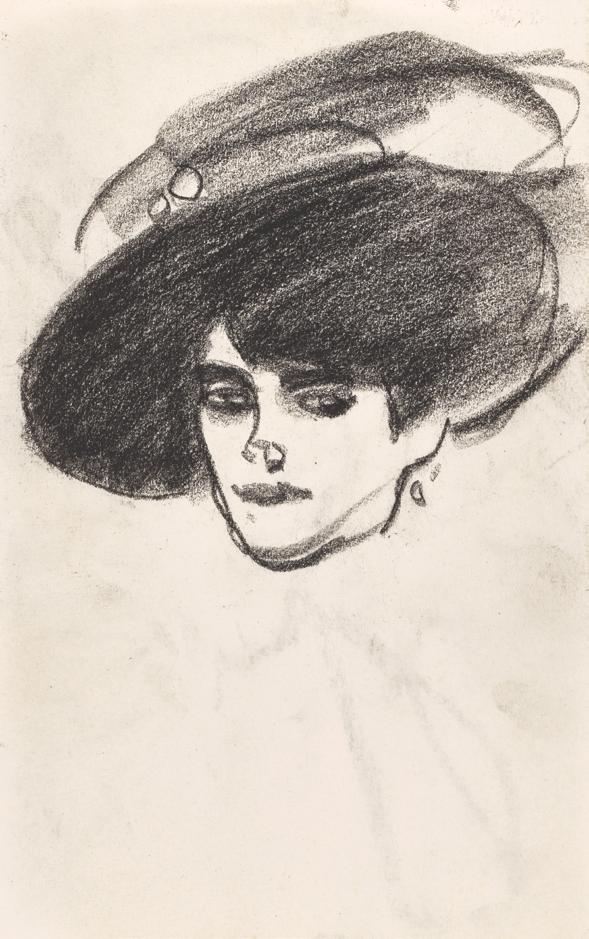

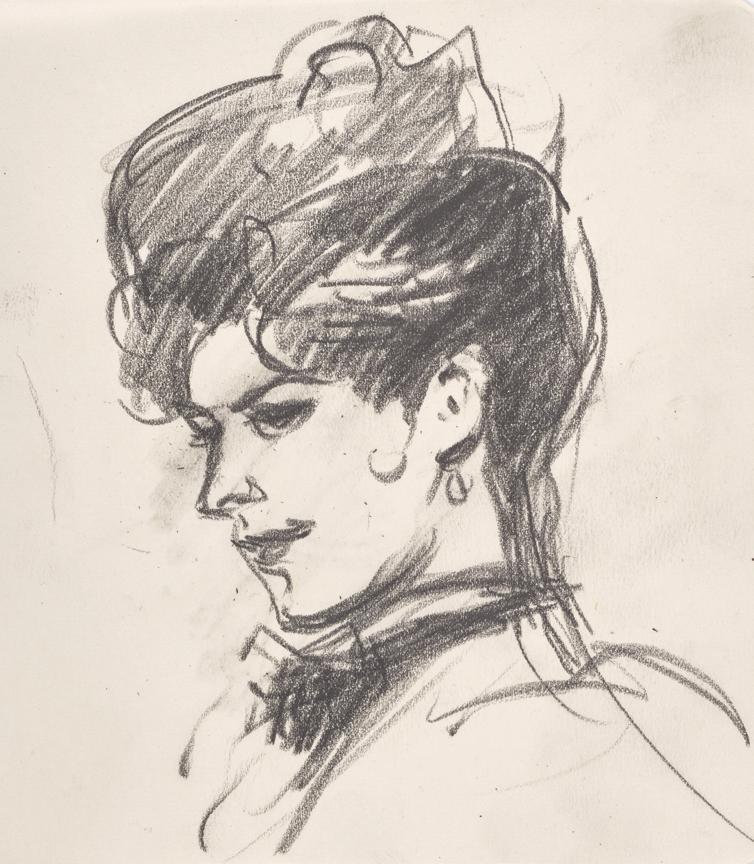

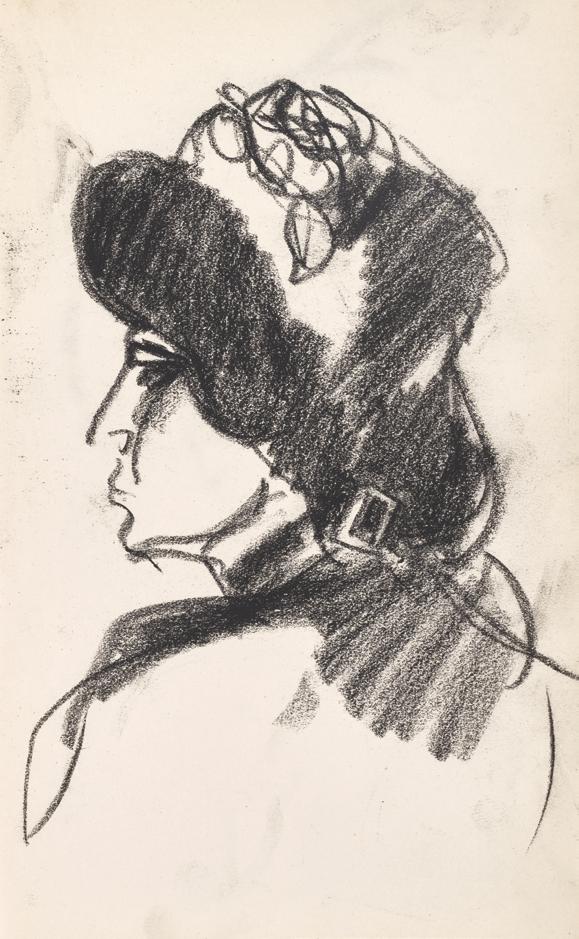

Neither artist had much money or made many sales so the ability to sit all night over a coffee or one glass of wine in the arrondissement’s many bars and cafés made life more bearable. Fergusson would occasionally teach a class at the Académie de la Palette, where his constant instruction to his students was to make a sketchbook an indispensable tool of their life outside the classroom. Fergusson followed his own advice avidly during his evenings at le Dôme, Closerie des Lilas and his particular favourite, le Café d’Harcourt. This was the haunt of the seamstresses and young women who worked at the local couturiers and milliners, and they happily allowed this bluff Scot to quickly capture their likenesses in his inexhaustible supply of sketchbooks. These drawings did not necessarily translate into specific paintings, although Fergusson’s fascination with the flamboyant creations these girls wore on their

heads was a recurring attraction for him. Their plasticity and elaborate structures coincided with his growing interest in sculpture, further developed in the years after he left France and returned to Britain after the outbreak of war in 1914.

Rice usually accompanied him to the Harcourt, making her own sketches, although Fergusson later confessed to Margaret Morris, his constant companion after 1913, that this was not an establishment where one would normally take a respectable lady. But for Rice, as for Fergusson, le Café d’Harcourt was a place of work as much as a social destination. When, in 1909 Fergusson was made a Sociétaire of the Salon d’Automne in Paris, the venue which in 1905 hosted the first exhibition of the Fauves, Anne and her American friend Elizabeth Dryden were the subject of several of the paintings that Fergusson sent to its annual exhibition. The largest painting, La Terrasse, Café d’Harcourt, was a dual celebration of both the location and, almost certainly, Anne herself who must surely be the central figure in the striking pink dress staring at the artist. It is a painting which is a culmination of an era for Fergusson and, for me, perhaps his chef d’oeuvre

A new motif began to take centre stage for Fergusson – the nude. Allied with a growing use of decorative backgrounds and patterns in his paintings Fergusson became fixated with a concept he defined as Rhythm. The philosopher, Henri Bergson, espoused similar ideas at this time; it became the talk of the cafés but Rice and the other members of Fergusson’s small group of friends were not drawn under its spell. Despite, the suggestion of movement in the term, Fergusson’s paintings Rhythm and At my Studio Window are surprisingly static, their figures statuesque rather than fluid, anonymous

nudes rather than the intimate studies of Rice that Fergusson had painted earlier. Fergusson began to move in different circles, socially and intellectually, following a meeting in mid-1910 with John Middleton Murry and Michael Sadler who were in Paris exploring the artistic life of the city, which developed into their enterprise of a new magazine exploring the cultural currents of the era. Fergusson was persuaded to join them as art editor, and Rhythm become the journal’s title. It was short-lived, and Fergusson’s involvement with it even shorter, although Fergusson and Murry remained friends for the rest of their lives. In a letter of February 1955, responding to a recent letter from Fergusson, Murry regrets not being able to visit a forthcoming exhibition in London (presumably Fergusson’s last show at Reid & Lefevre in March that year) and then goes on to congratulate Fergusson on his marriage to Margaret Morris – Fergusson had been a witness in 1918 at Murry’s marriage to Katherine Mansfield.

If the Rhythm series of paintings seem the antithesis of the term, one painting of the period positively grasps the idea of movement Fergusson’s largest surviving oil painting, Les Eus. Its nudes, muscular and bronzed by the sun, dance in a vigorous circle surrounded by more naturalistic foliage than that in the backgrounds of Rhythm and its contemporaries. Its title was apparently invented by Fergusson, The Well Ones. Margaret Morris once suggested to me that it could also be translated as The Possessed.

These were the years that the Ballets Russes and Isadora Duncan were appearing in Paris. We know that Fergusson and Peploe were regular attendees, along with Rice, at the Ballets Russes; Peploe said to Fergusson that these were among the greatest nights in his life.

Paris is simply a place of freedom. Geographically central, it has always been a centre of light, learning and research. It will be very difficult for anyone to show that it is not still the home of freedom for ideas; a place where people like to hear ideas presented and discussed; where an artist of any sort is just a human being like a doctor or a plumber, and not a freak or a madman.

J.D. Fergusson J.D. Fergusson, Rhythm, 1910, oil on canvas, 116.2 x 115.5 cm

Courtesy of University of Stirling Collection, Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries

J.D. Fergusson, Rhythm, 1910, oil on canvas, 116.2 x 115.5 cm

Courtesy of University of Stirling Collection, Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries

Fergusson was probably working on it over an extended period of 1911-13; no studies survive that might be related to it, possibly because Fergusson was for part of those years moving between Paris and the south of France, followed by the disruption of the war.

For many artists born or living in the northern parts of Europe, including the north of France, the lure of the Mediterranean south was inescapable. Fergusson was no exception; he had experienced its heat and light and colour on his visits to Spain and north Africa around 1900 and longed for a return to its soft climate. In mid-1913 he and Rice and Peploe, the latter with his wife and young family, spent some time in Cassis, all three painting side-by-side. Later that summer, Fergusson moved alone to a house in Nice, loaned to him by Frank Harris, which he intended to use as a base while he searched for a more permanent location on the Riviera. Throughout the summer and later months of 1913, Fergusson embarked on an intense correspondence with a young English dancer who at the beginning of the year had arrived in Paris with her dance troupe to perform at the Marigny Theatre. Margaret Morris had been provided with a letter of introduction to Fergusson and the pair of them experienced an immediate attraction which was disrupted by Morris’s return to London for other performances and Fergusson’s commitments to Cassis.

Anne Estelle Rice’s biographer, Carol Nathanson, records a probable mental and physical crisis suffered by Rice in the autumn of 1913. She attributes this to Fergusson’s ending of their relationship in early September followed by a possible miscarriage of his child shortly afterwards. There was no doubt of the

seriousness of Fergusson’s love for Margaret Morris (and they stayed together until his death in 1961) but his relationship with Rice would not have survived the presence of children. Nor would it have been immune to tension over the growing reputation of Rice as a painter, following a masterly group of work around 1912. Fergusson never associated again with an artist who might challenge his pre-eminence; and in Morris he found a partner who was similarly determined not to let children disrupt her career as a dancer, choreographer and impresario. Towards the end of the year, Rice married the English theatre and art critic whom she had met earlier in Paris. Fergusson acquired a ‘hut’ in a garden near Antibes which he decorated and furnished in time to welcome Margaret Morris for Christmas.

The outbreak of war drove him and Morris, separately, back to Britain, to Chelsea where they each established their separate studios, to preserve the ‘proprieties’ for the parents of Morris’s younger pupils. Morris gathered around her as members of her theatre club in Chelsea an older generation, immune from conscription into the armed forces, including Wyndham Lewis, Epstein, Wadsworth, Augustus John, the Sitwells, Charles and Margaret Mackintosh, Arnold Bax, Gordon Craig and many others. It wasn’t Paris but that was a moment that was over for many people.

Fergusson had brought Paris and the Modern Movement to London and Scotland, and in Paris he left a memory of Scottish integrity and determination, persistence and dedication. But the moment was over, and Fergusson turned to the decades ahead with new ideas, a new partner, a new drive to build on his already impressive past.

J.D.Fergusson is both a painter and sculptor. He was born of Highland parents, is a true Celt, and worked in Paris both before and after the War. Since 1909, he has exhibited at the Salon d’Automne, and the influence of France must be upon him. Yet, whatever impressions he has garnered in France, no Frenchman could have painted Fergusson’s pictures. There is nothing imitative in his work; rather it is the expression of an unusually strong personality. His compositions have attracted the French critics by their pleasing, unforced originality, kept always in bounds by an austere sense of good taste. Strength combined with grace characterises his pictures, and also his most attractive statuettes.

Excerpt from Scots’ Conquest of Paris. What the French think of our Scottish Painters by Marten

J.D. Fergusson did not consider himself a landscape painter, indeed professional accomplishments and acknowledgements were infra dignitatem. In his maturity as a painter the outdoors became a space in which issues of design were reconciled and themes were developed. Les Eus and Rhythm are set in versions of Eden, outdoor places of health and freedom influenced by German Lebensreform ideas. His series of Scottish landscape paintings made in the early 1920s were a reengagement with his Celtic origins, but were still rigourously composed in Cubistinfluenced style. His earliest works in oil paint however are of the landscape, chiefly in small scale, made en plein air using a

Pochade painting box. He painted these low toned studies in Edinburgh, Fife, on on trips to Islay, and then after 1900 on his many visits to Northern France, sometimes with his friend S.J. Peploe. The exact location of this panel is uncertain from the inscription but is likely to be in the Commune of Gaye in north eastern France, (here misspelled, not entirely untypically by Fergusson as Gaie in his inscription on the verso.) He deploys his favoured creamy oil vehicle, working quickly in an impressionist style incorporating the figure as well as buildings but for colour and space he respects the information in front of him.

Guy Peploe1 A House in Gaie, c.1901 oil on panel, 14.5 x 11.5 cm titled verso

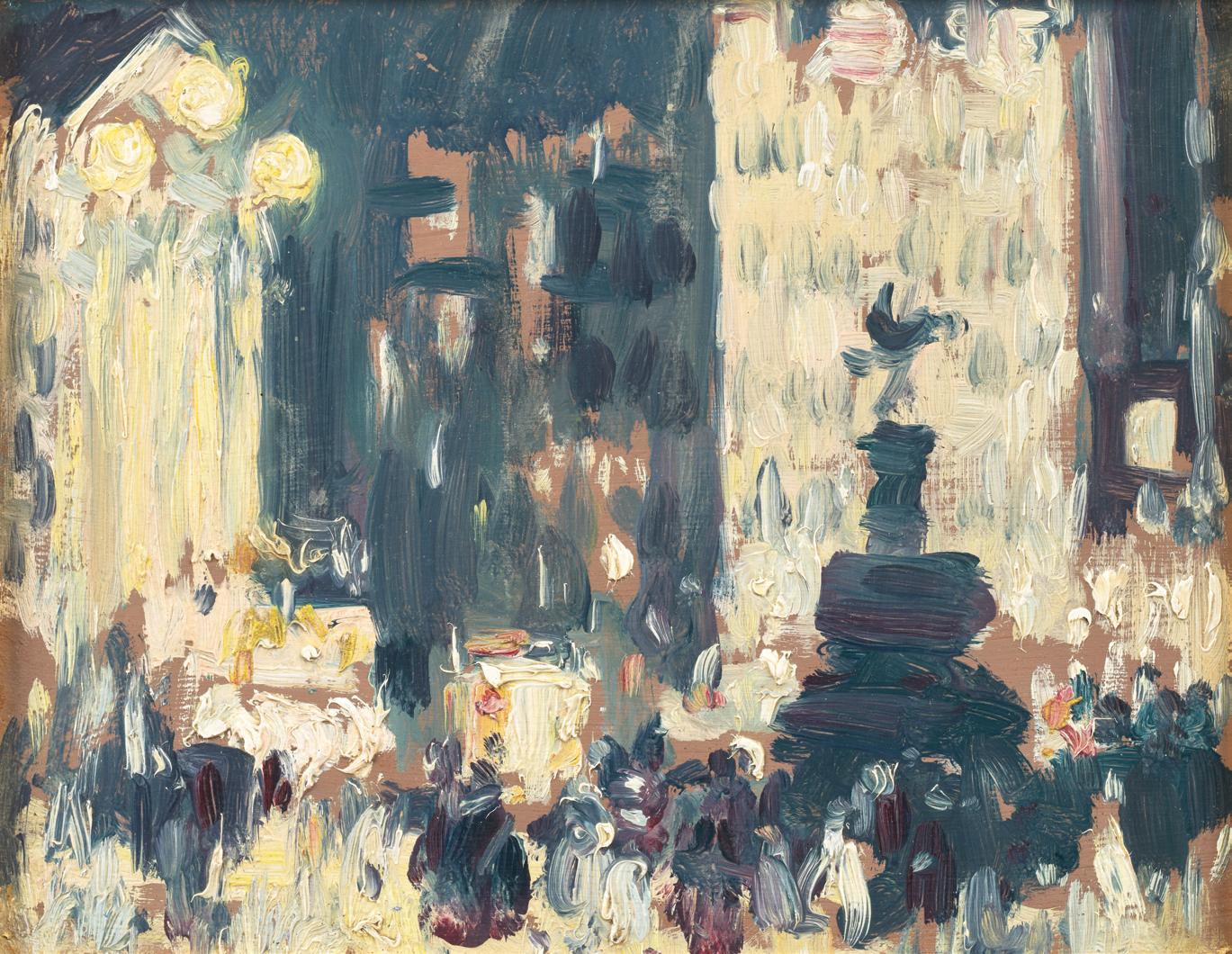

Picadilly Circus, Night is a small, vibrant panel and an important early example of Fergusson’s impressionism. He had worked on panel, on the spot, for some years, mostly in Edinburgh. In the proceeding years he made yearly visits to the Pas de Calais, often to Paris-Plage, Le Touquet sometimes with his friend S.J. Peploe. In 1907, he moved to Paris and continued to paint street scenes at night, recalling this earlier London example. Piccadilly was described by Charles Dickens Jr as ...the great thoroughfare leading from the Haymarket and Regent-street westward to Hyde Park-corner, is the nearest approach to the Parisian boulevard of which London can boast. The Circus lost it circular form in the 1880s with the remodelling of the Regent Street Quadrant and the building of Shaftesbury Avenue. By the end of the 19th Century, it was the heart of theatre land, the brilliantly lit hub it remains today. The

Alfred Gilbert statue of Anteros surmounts a fountain forming the Earl of Shaftesbury Memorial. Its delicate form is captured brilliantly by Fergusson with a few deft strokes grounding the location, highlighted against the lights of the buildings beyond. The bustle of humanity, indications of horsedrawn cars, the dirty gas light, all convey the atmosphere of excitement and the theatrical character of the architectural setting connected to the painter’s sense of possibility and change: a new century, the Edwardian era, new freedoms for artists willing to engage and respond. Dr James Ritchie, an important Edinburgh collector many of whose paintings are now held in the National collection, bought several paintings in Glasgow accompanied by Fergusson himself who, as Dr Ritchie recalled, paused in front of each work and said ‘Good Fergusson’.

2 Picadilly Circus, Night, 1902 oil on panel, 18 x 22 cm signed and titled verso

Provenance: Dr James Ritchie, thence by descent Exhibited: Baillie Gallery, London, 1908, cat. 36;

J.D. Fergusson: Paintings 1898-1957, T.R. Annan & Sons, Glasgow, 1957, cat. 7

Guy Peploe

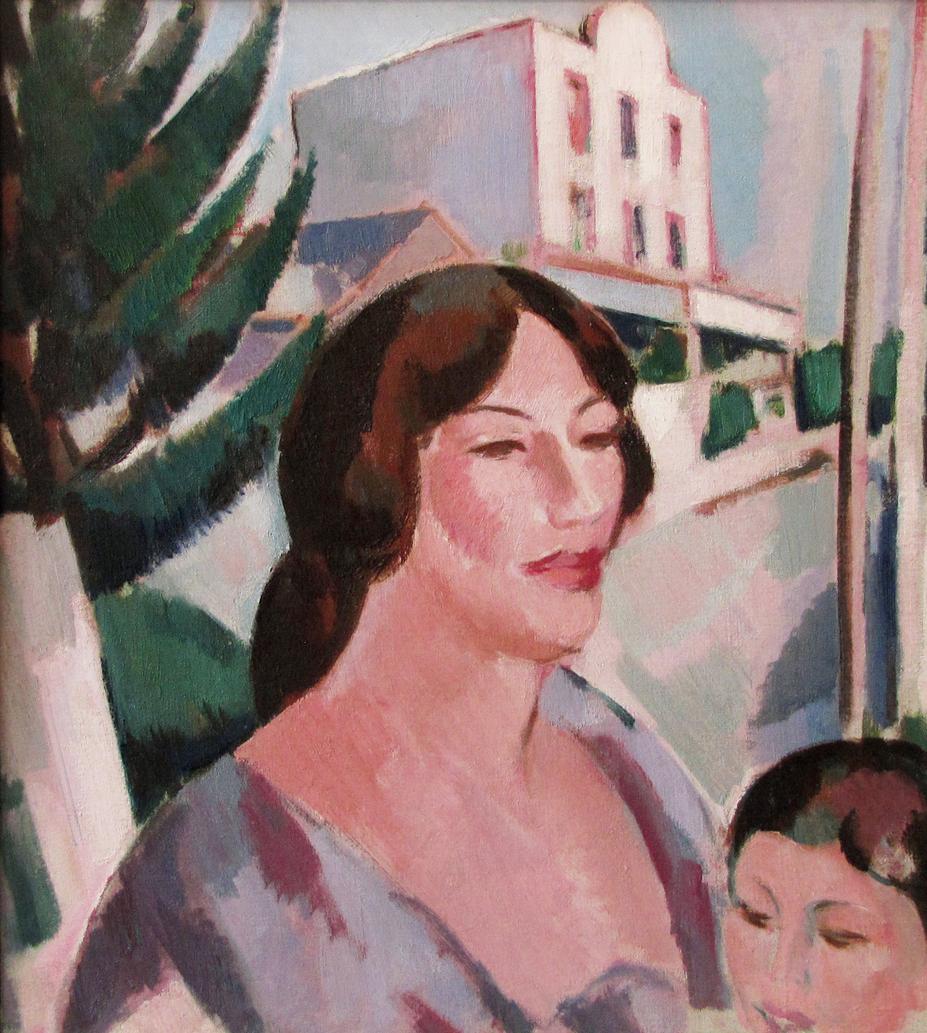

In August 1913, Fergusson was in Cassis with his partner Anne Estelle Rice, accompanying S.J. Peploe, his wife Margaret and their son Willy. It was both artists’ first visit to the South of France and their choice of the small fishing village near Marseilles may have been inspired by the many French painters who had worked there before, including Paul Signac. It was Fergusson who recalled persuading Peploe to accompany him after seeing a poster with the name ‘Cassis’ on it near his Paris Studio. Fergusson recalled in 1945 in his Memories of Peploe that at first he thought it would be too hot for ‘Bill,’ but he decided to take the risk. We arrived to find it quite cool and Bill didn’t suffer at all. We had his (third) birthday there and after a lot of consideration chose a bottle of Château Lafite instead of champagne. Lafite now always means to me that happy lunch on the verandah overlooking Cassis bay, sparkling in the sunshine. As in Royan three years before, both painters worked chiefly on panel, although Fergusson used several canvasses and both made many sketches, particularly of the harbour and its traffic of schooners.

It may have been a difficult time for Fergusson and Rice who were to separate shortly;

Fergusson had already met Margaret Morris in the spring when she had brought a troupe of her dancers to Paris to perform at the Marigny Theatre. Fergusson, whose Paris studio had been demolished, decided to stay in the south. By Christmas, he was renting a little house at Cap d’Antibes where he persuaded Morris to join him and where they spent the summer of the next year before the outbreak of War forced their return to London.

The group stayed in the Hotel Panorama, which forms the backdrop to the portrait, with its distinctive round pediment on the façade and screened verandah below. Peploe painted the same view when he returned with Willy, Denis and Margaret in 1924.

At this time, Fergusson was seeking more structure in his compositions the simplification of motif recalls the later Cézanne. The paint was applied in short, directional brush marks and the palette restrained. In recollection, he has captured the calm strength of his subject with her young child, confident in motherhood.

Guy Peploe

Hotel Panorama, Cassis, c.1913

Guy Peploe

Hotel Panorama, Cassis, c.1913

3 Margaret and Willy Peploe at Hotel Panorama, Cassis, 1931 oil on canvas, 61 x 56.5 cm signed verso

Provenance: Gifted to S.J. Peploe, thence by descent

Fergusson’s love of art as a boy had been engendered by his mother, who had encouraged him to draw and took him to the National Gallery of Scotland on the Mound and the Royal Scottish Museum in Chambers Street. He was given his first box of oil paints in 1883.

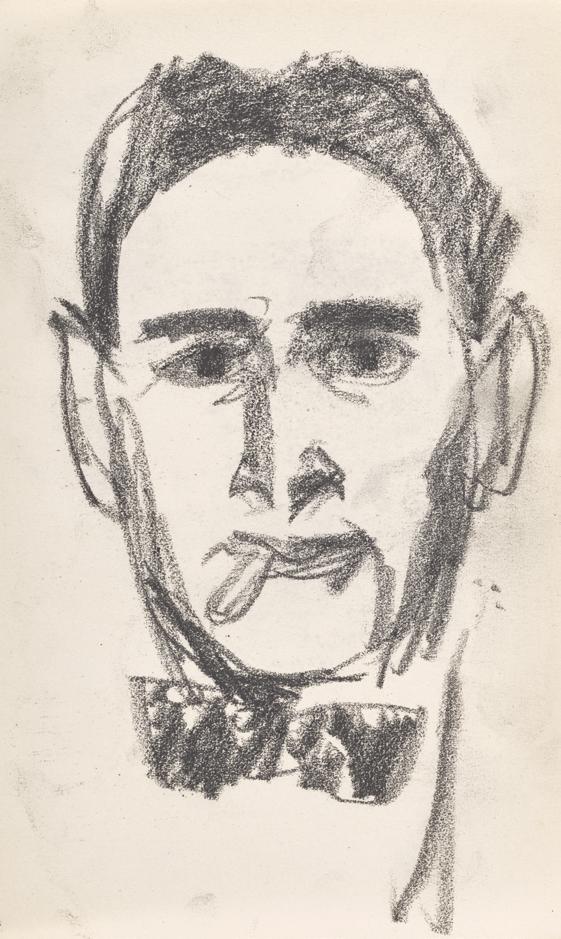

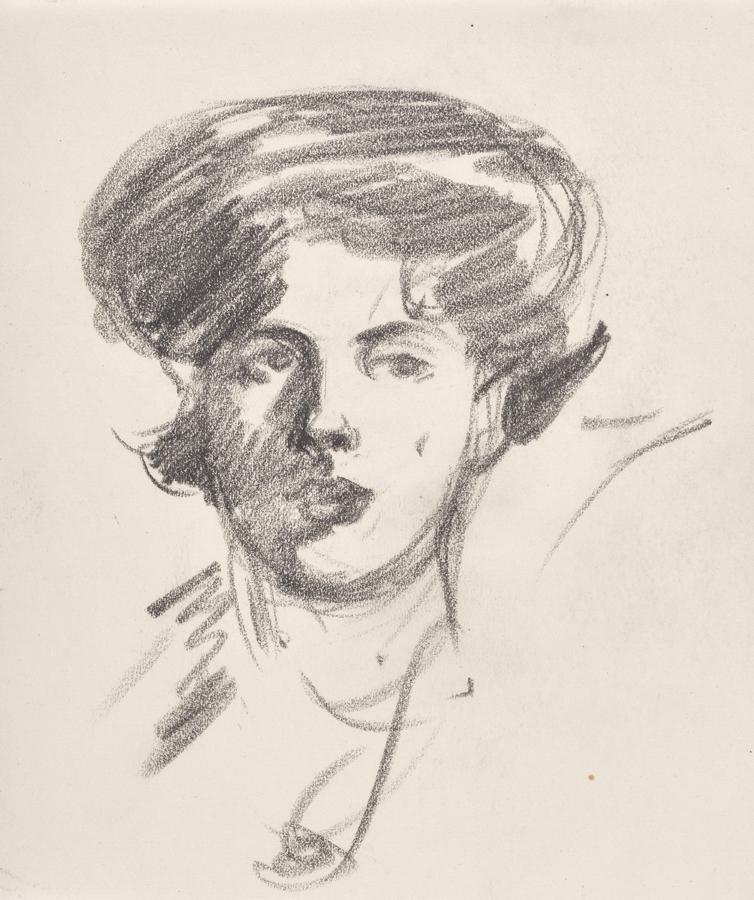

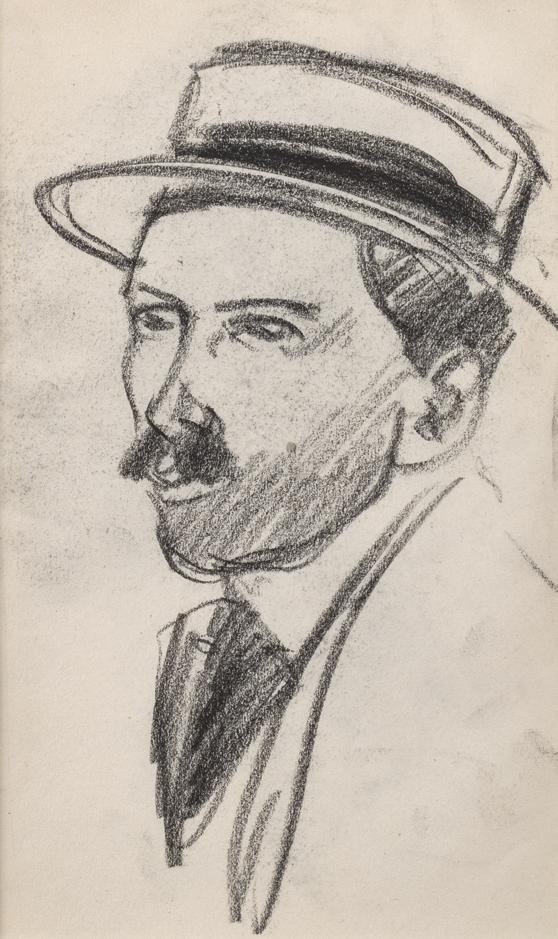

A prolific recorder of everyday life, Fergusson always carried a sketchbook with him. The story went that he failed his second-year exams at Edinburgh University because he spent too much time sketching caricatures of his professors.

The small scale of his sketches establishes them as an immediate response to the people he would have seen on the streets and in the cafes of Edinburgh and in particular Paris. Fergusson made several thousand drawings in his lifetime, and each has a particular quality. He did draw from life models and occasionally drew ‘thinking about painting’ (colour notes are sometimes written on a drawing) but mostly he was outside with his sketchbook. Drawing for Fergusson was like breathing in and out: the natural and essential practice of the artist.

Fergusson’s advice to would-be independent painters was – always carry a small, cheap sketchbook, a very soft pencil, and make

quick, rough sketches of anything around you; never correct a sketch, just make another; don’t try to make a good drawing, you won’t –or by accident, you may! Just keep at it, you are training your eye to see and your hand to respond.

Fergusson made only a handful of works in three dimensions, but with his talent, sculpture became a significant part of his practice, and they were exhibited in New York, France, London and Edinburgh. From his drawings, we see that he had no difficulty thinking in the round and his deep understanding of oil paint as a plastic medium makes the translation to clay a natural one. He also produced a few carvings. One depicts the life-size faces of himself, Margaret Morris and their friend and patron George Davison, hewn from one piece of stone. His masterpiece, Eastre (opposite), originally cast in brass in 1924, depicts a pagan goddess. The medium is specifically chosen so that when polished and lit, the effect is an extraordinary emanation of light. Our group of sculptures includes rare carved, and hand-painted plaster works and three bronzes. The bronzes, which were conceived in c.1914 - 1919 were cast in an edition of 9 in 2013 under the approval of the J. D. Fergusson Art Foundation.

Guy Peploe J.D. Fergusson, Eastre (Hymn to the Sun), 1924, bronze, H24 cm Courtesy of Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries

4 Self Portrait with Cigarette, c.1910

Conté on paper, 20.9 x 12.8 cm

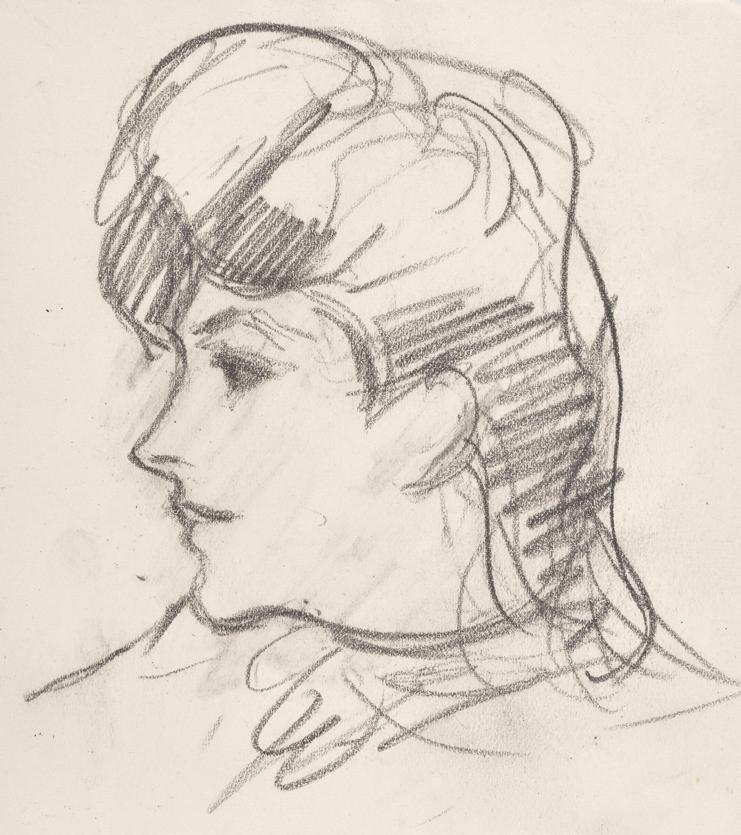

5 Self Portrait in Profile, c.1910

Conté on paper, 20.9 x 12.8 cm

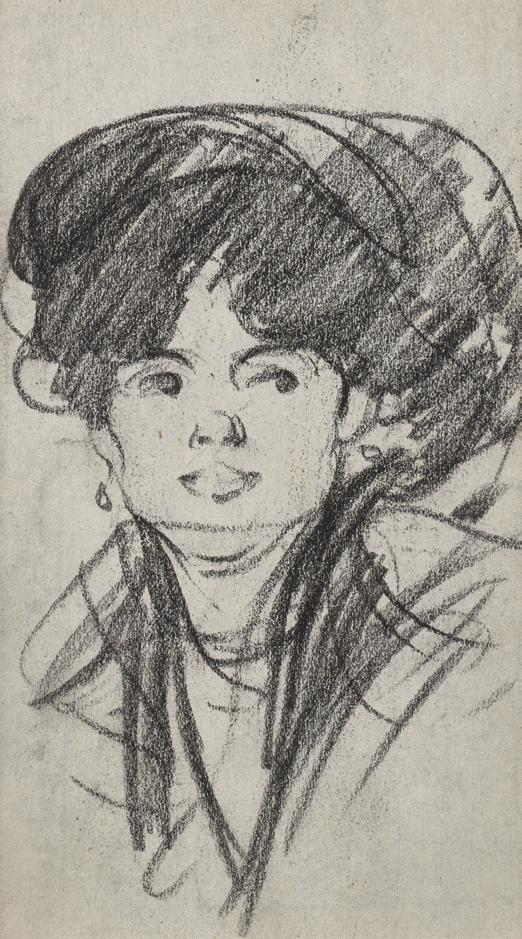

6 The Wide Brimmed Hat, c.1907

Conté on paper, 20.9 x 12.5

7 Anne Estelle Rice, c.1910

Conté on paper, 20.9 x 12.8 cm

8 Study for The White Hat, 1905

Conté on paper, 12 x 11.5 cm

9 Midinette, c.1907

Conté on paper, 11.9 x 13.3 cm

10 Jean Maconochie c.1904

Conté on paper, 15 x 8.5 cm

11 La Closerie des Lilas, Paris, c.1907

Conté on paper, 12.5 x 11 cm

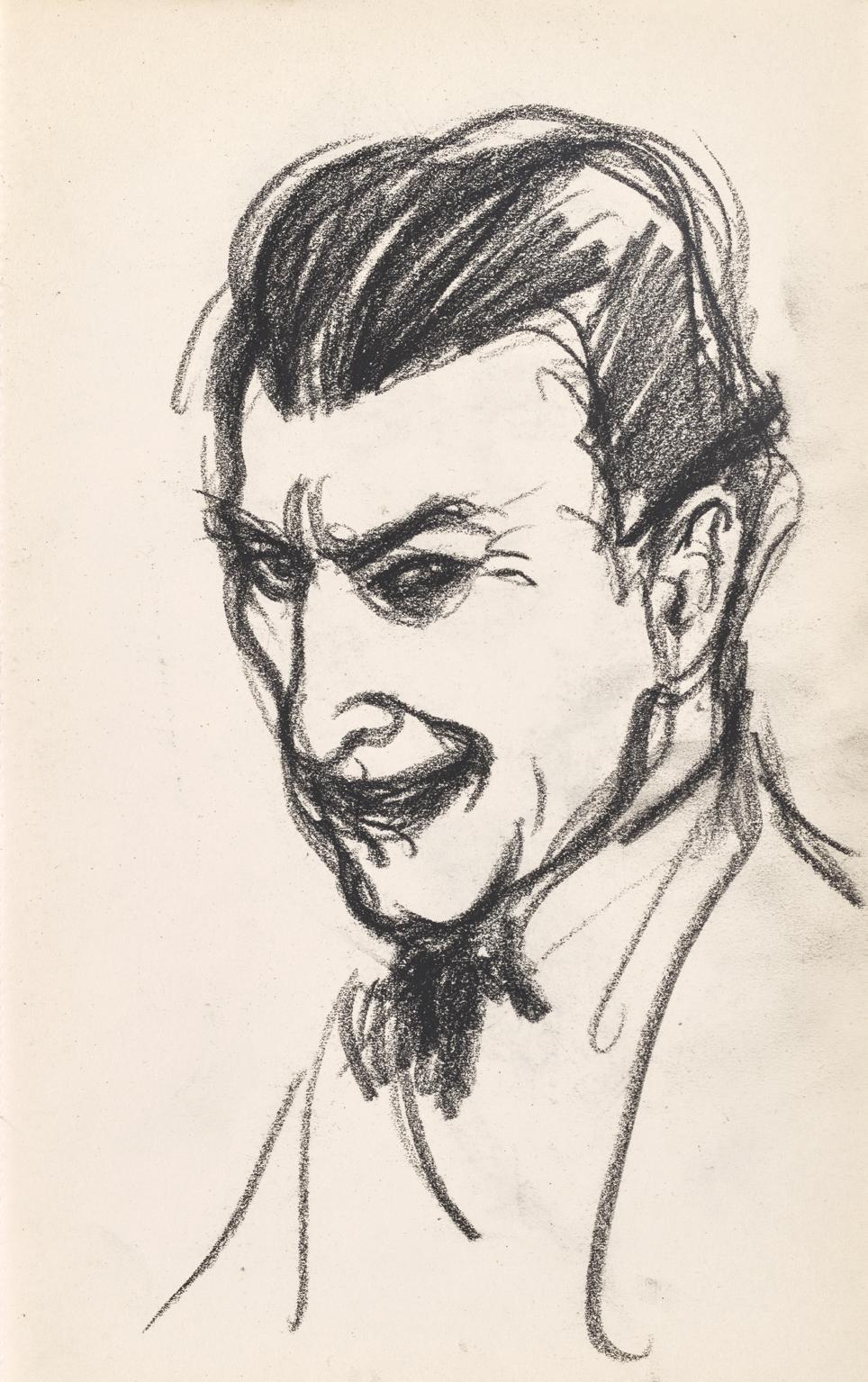

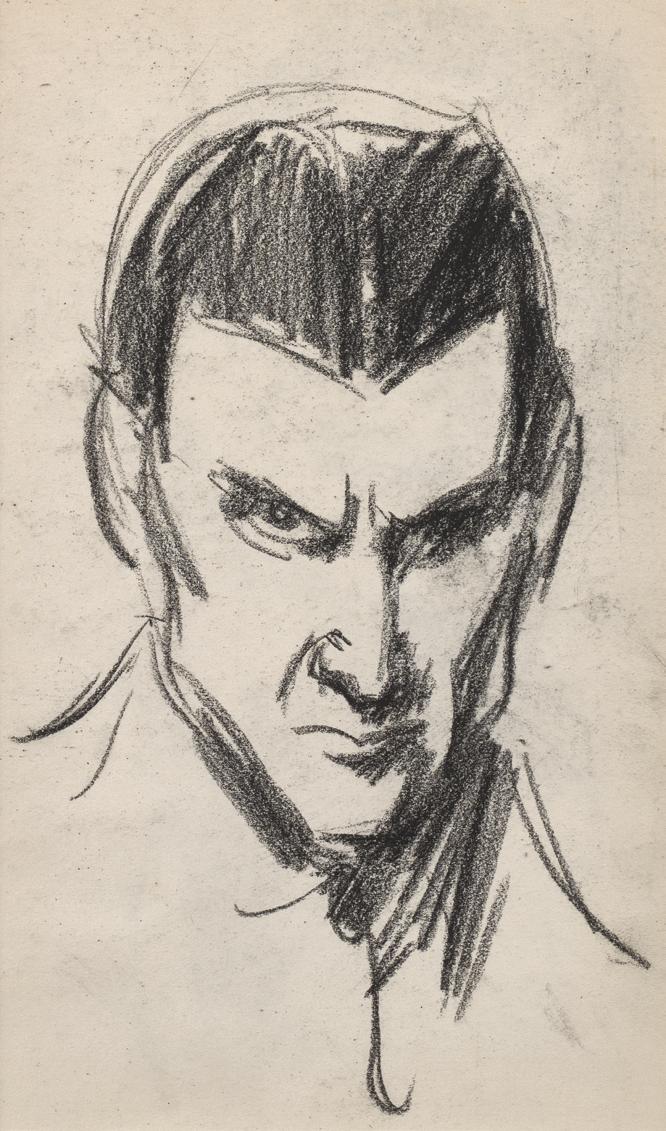

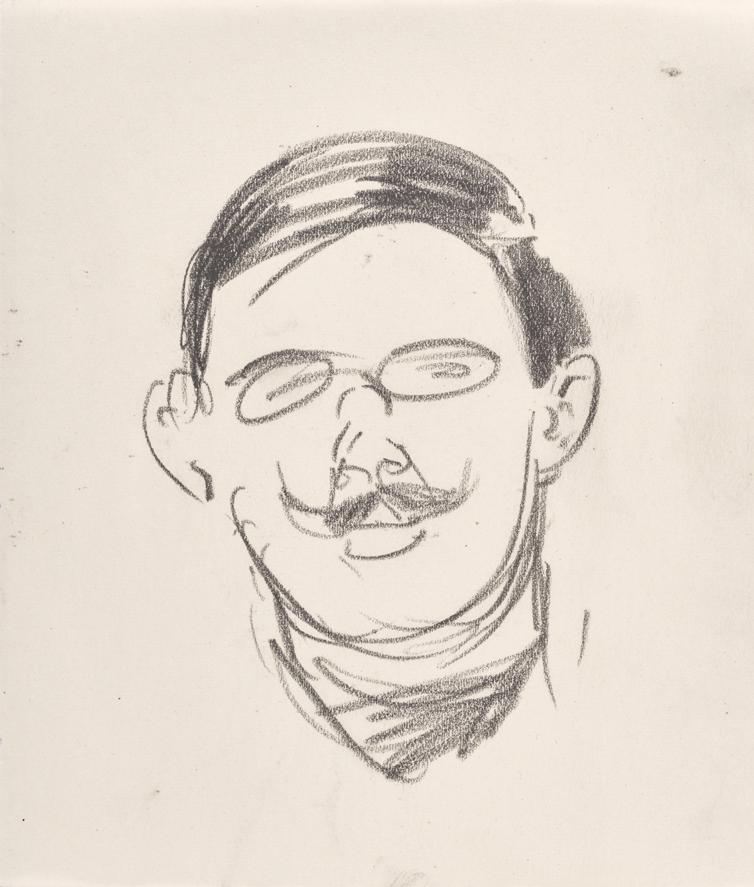

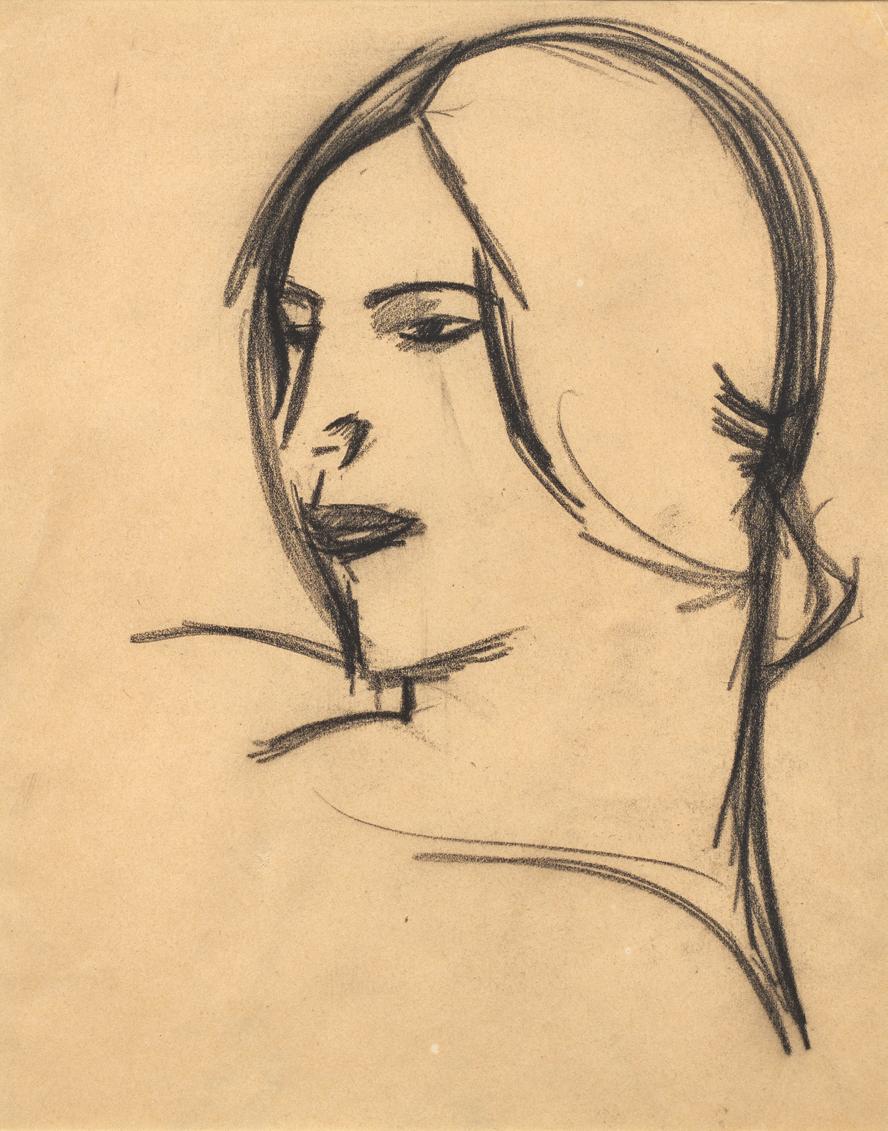

12

Self Portrait, Paris, c.1910

Conté on paper, 20 x 12 cm

12

Self Portrait, Paris, c.1910

Conté on paper, 20 x 12 cm

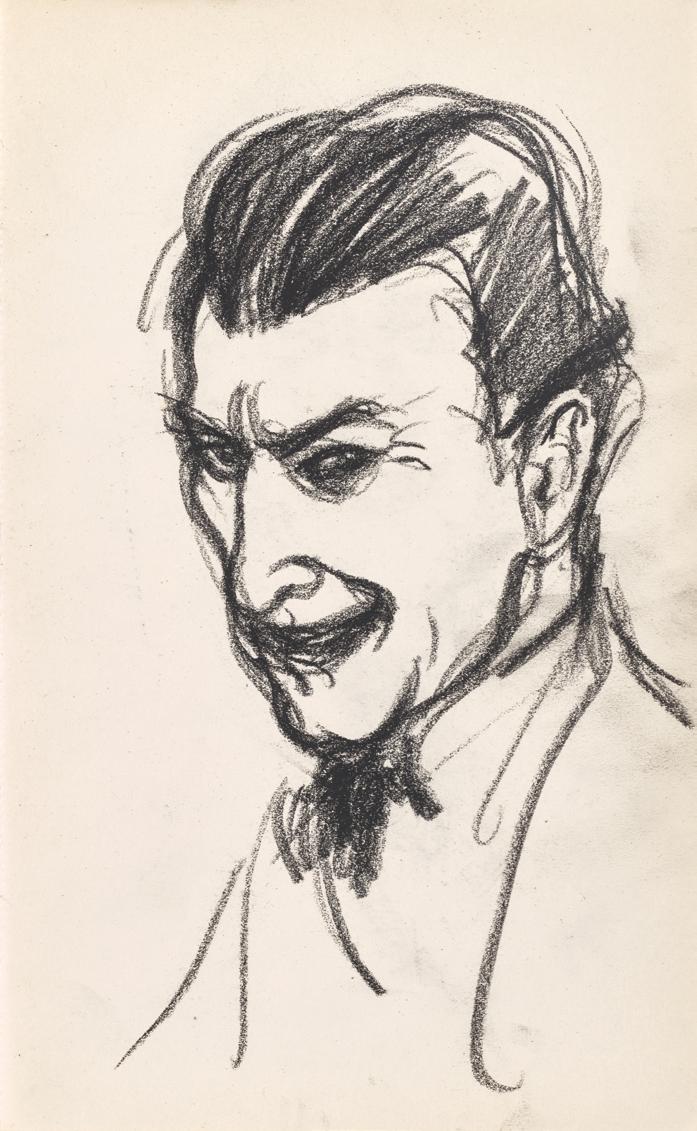

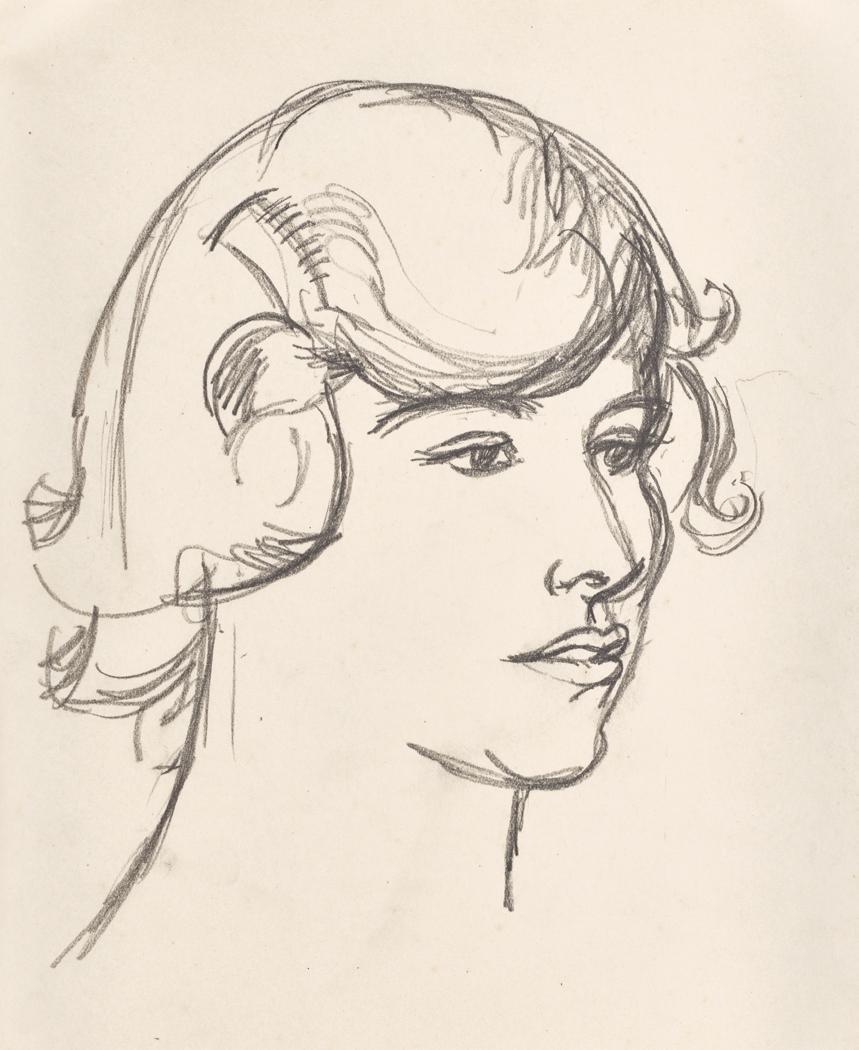

13

Self Portrait, c.1910

Conté on paper, 21.1 x 13.1 cm

14 La Parisienne, c.1908

Conté on paper, 11.9 x 13.3 cm

15 Au Bal Bullier, c.1908

Conté on paper, 20.9 x 12.8 cm

16 La Serveuse, c.1907

Conté on paper, 12 x 11 cm

17 Downward Gaze, c.1907

Conté on paper, 12.5 x 11.5 cm

18 La Modiste, c.1909

Conté on paper, 21.1 x 12.8 cm

19 La Cocarde, c.1909

Conté on paper, 11.9 x 13.3 cm

20 Woman in a Hat, c.1907

Conté on paper, 12 x 11 cm

21 Before the Opera, c.1909

Conté on paper, 21.1 x 13.1 cm

22 Man in a Hat, Paris, c.1908

Conté on paper, 16 x 12.5 cm

23 Le Plaisancier, c.1910

Conté on paper, 20 x 12 cm

24 La Violoncelliste, c.1908

Conté on paper, 11.9 x 13.3 cm

25 Des Lunettes, c.1907

Conté on paper, 11.9 x 13.3 cm

26 La Vie en Rose, c.1909

conté on paper, 20.5 x 12 cm

27 Woman with Necklace, c.1910

Conté on paper, 20 x 12 cm

28 Woman in Black, Paris, c.1909

Conté on paper, 20.9 x 12.8 cm

Conté on paper, 12.5 x 11.5 cm

29 Le Grain de Beauté, c.1909 Margaret Morris’s Summer School, Cap d’Antibes, 1924 Courtesy of Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries

Margaret Morris’s Summer School, Cap d’Antibes, 1924 Courtesy of Culture Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries

30 By the Pool, Cap d’Antibes, c.1924 Conté and watercolour on paper 19.5 x 24.5 cm

31 Le Tricolore, Royan, c.1911

Conté on paper, 18 x 11.5 cm

32 Sail Boat, Royan, c.1910

Conté on paper, 16 x 11.5 cm

33 Sur la Mer, Cassis, 1913

Conté on paper, 18 x 12.3 cm

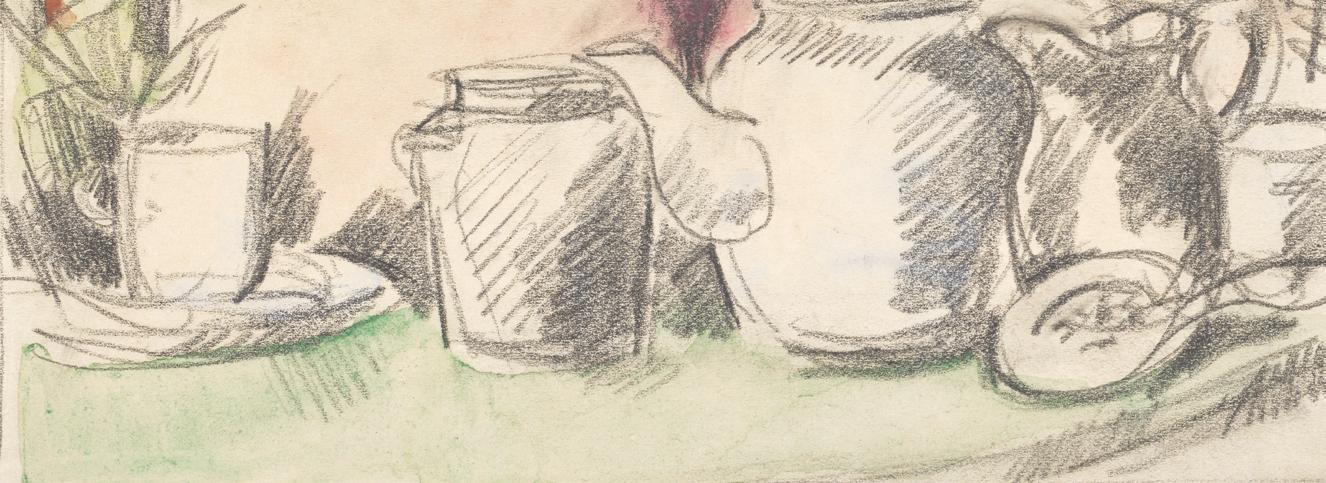

34 Kitchen Still Life, c.1925 Conté and watercolour on paper, 9 x 18.5 cm

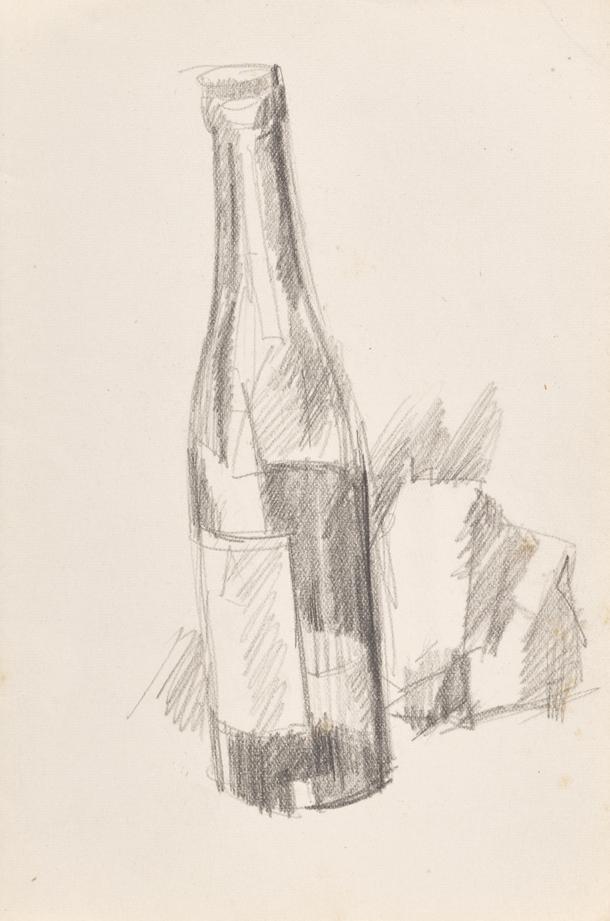

35 Vin Blanc, c.1919

Conté on paper, 18.5 x 12.5 cm

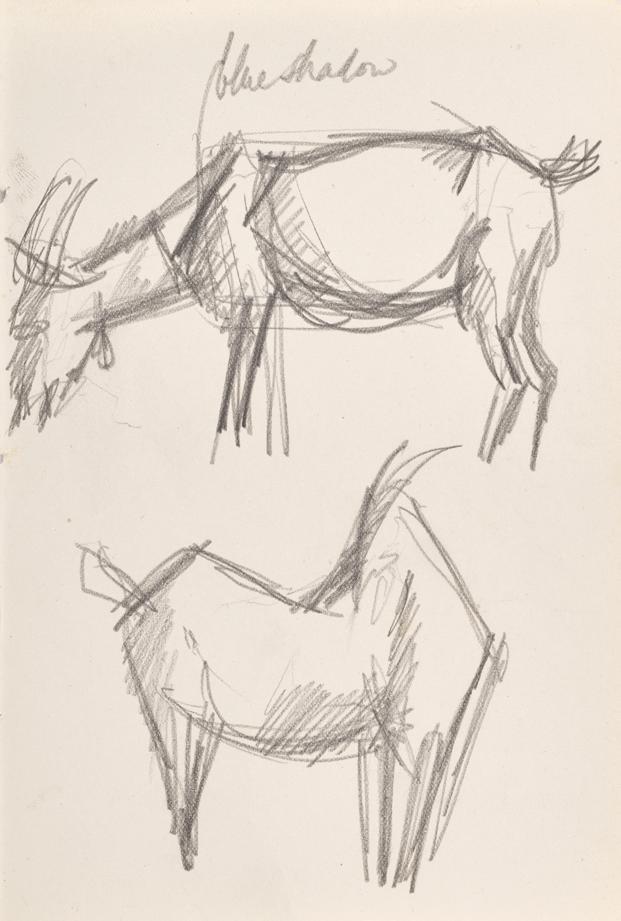

36 Mountain Goats, Harlech, 1921

Conté on paper, 18.5 x 12.3 cm

Anne Estelle Rice (1877 – 1959) was an Irish-American painter who Fergusson met in 1907 at Paris-Plage. The two had an instant connection and for the next six years were involved personally and creatively. Rice was originally from Pennsylvania and was working as a magazine illustrator in Paris. Her outgoing personality entranced Fergusson and they shared a similar love of adventure. Rice would occasionally escort Fergusson to establishments deemed improper for women. Fergusson painted and drew Rice on many occasions, and At the Window (opposite) does something to capture her intense, selfconfident stare.

Guy Peploe Anne Estelle Rice, Margaret Peploe, Willy Peploe and Fergusson in Cassis, 1913

Anne Estelle Rice, Margaret Peploe, Willy Peploe and Fergusson in Cassis, 1913

37 At the Window, c.1913

Conté on paper, 20 x 12 cm

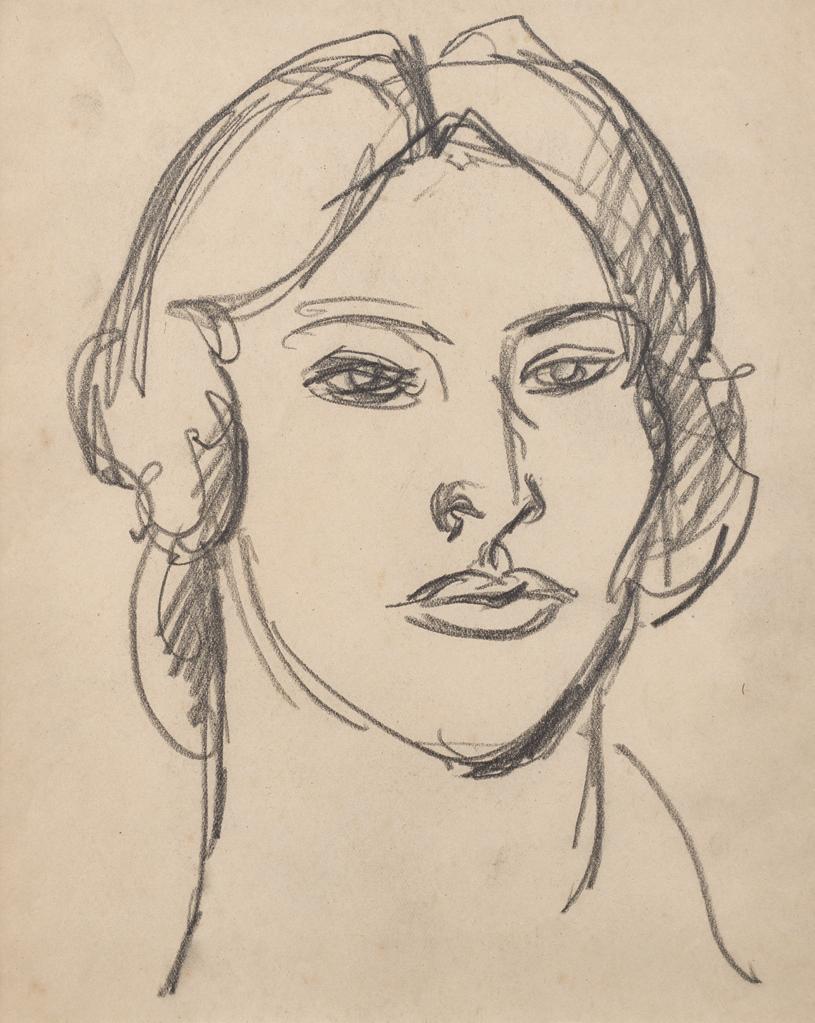

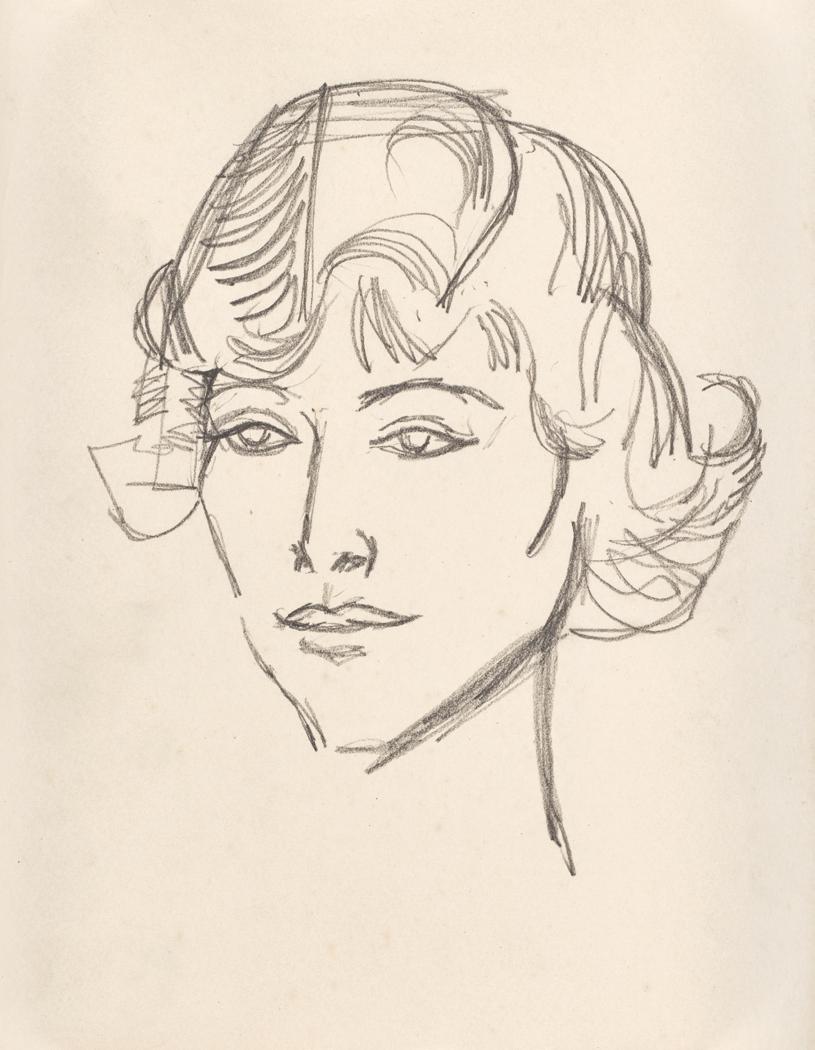

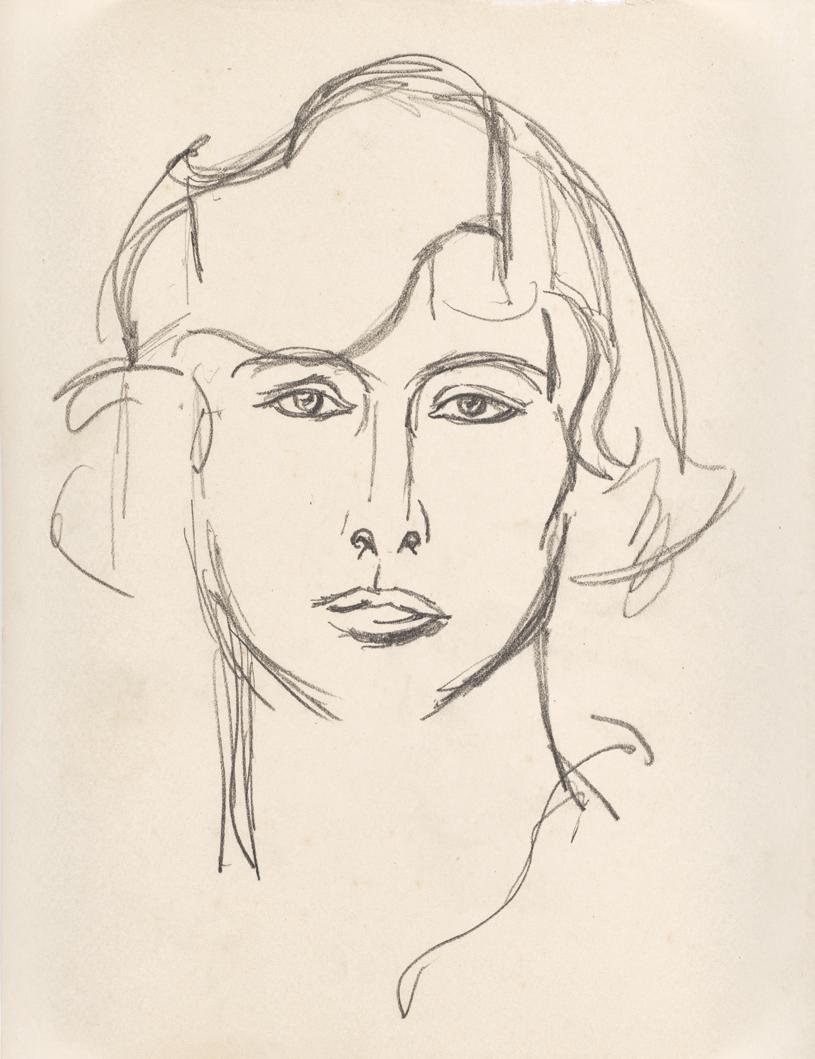

One of Fergusson’s most frequent subjects for drawing and in oil paint is a simple, female head, often full frontal, sculptural in its simplicity. Many are Meg, with her distinctive almond-shaped eyes.

Fergusson was introduced to Margaret Morris by a mutual acquaintance in Paris in 1913. Seventeen years his junior, Morris was to become Fergusson’s lifelong partner. She called him ‘Fergus’ after the ancient Irish king and he affectionately called her ‘Meg’. Margaret was not only an important

model for Fergusson, but as a pioneer in modern dance and choreography, her dynamic physicality and personality fascinated him and inspired much of his subsequent work.

Fergusson and Morris’s relationship grew into a burgeoning creative partnership. They held a firm belief in each other’s artistic vision in their respective art forms, centred on the quest for a new form of expression and language founded on colour, line and rhythm.

Guy Peploe

38 Margaret Morris, c.1918

charcoal on paper, 31 x 25 cm

Margaret Morris dancers, c.1932

Margaret Morris dancers, c.1932

Ifirst met Fergus in Paris in 1913 when I took a group to dance at the Marigny Theatre ... We got on famously and talked for hours. He made lots of drawings of me.

Margaret Morris, 1957

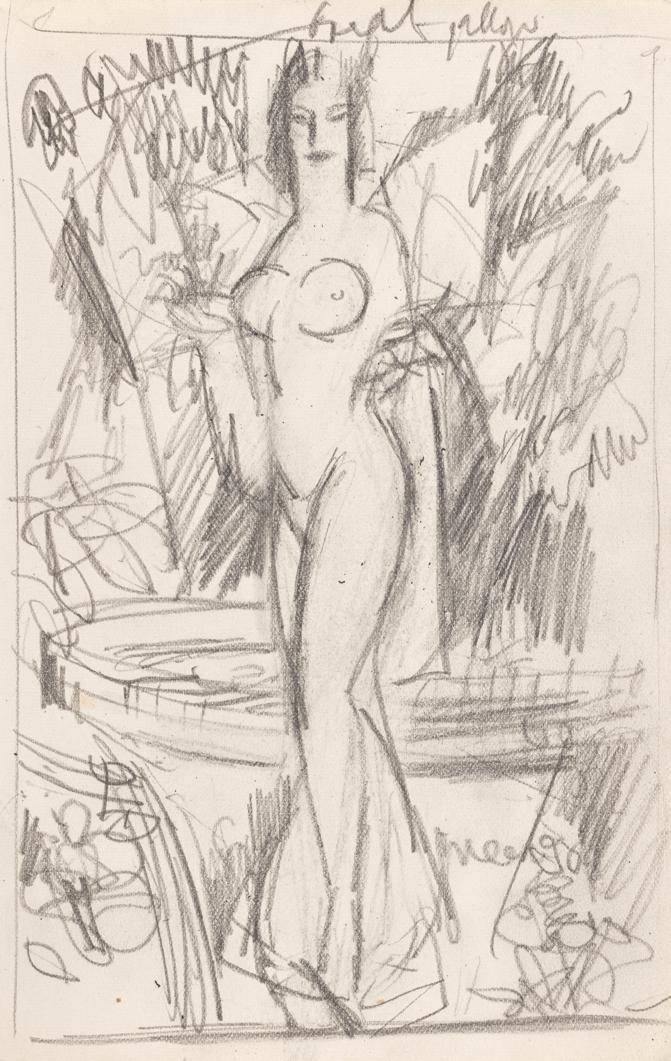

39 Standing Nude, c.1931

Conté on paper, 18.6 x 12.3 cm

40 Rose, Study, c.1918

Conté on paper, 18.5 x 12.3 cm

41 White Rose, c.1918

pencil and watercolour on paper, 13.5 x 12 cm

MrFergusson is among Scots artists the most interesting, in that he is always refusing to be tied down to a formula. He is continually making a new form within which to contain his ideas. He is, for example a most admirable sculptor, and several pieces in brass reveal ideas in simplification of the female figure, adapted to the assertive, shining surface of the metal with decision and style.

Excerpt from Joy in Colour, The Optimism of J.D. Fergusson, 1928

Fergusson made only a handful of works in three dimensions, but with his talent, sculpture became a significant part of his practice, and they were exhibited in New York, France, London and Edinburgh.

Guy Peploe

42 Standing Nude, conceived c.1914-19 bronze, 25 x 9 x 6 cm edition 6/9, cast 2013

43 Seated Nude, conceived c.1914-19 bronze, 14 x 15 x 10 cm edition 6/9, cast 2013

44 Philosophie, c.1919

carved plaster, 14 x 11 x 5 cm

44 Philosophie, c.1919

carved plaster, 14 x 11 x 5 cm

45 Standing Nude, c.1914-19

carved plaster, hand-painted by the artist 25 x 9 x 6 cm

46 Rhythm, c.1914-19

carved plaster, hand-painted by the artist 19 x 8.5 x 5 cm

47 Seated Nude, c.1914-19

carved plaster, hand-painted by the artist 14 x 15 x 10 cm

48 Head of Meg, conceived c.1914-19 bronze, 13.5 x 7 x 10 cm edition 1/9, cast 2013

49 Meg, c.1918

Conté on paper, 23 x 18.5 cm

50 Meg, c.1924

Conté on paper, 18.5 x 12.5 cm

51 Dancer in Profile, c.1928

Conté on paper, 25.3 x 20 cm

52 Portrait of a Woman, c.1928

Conté on paper, 25.3 x 20 cm

53 Dancer at Rest, c.1924

Conté on paper, 25.3 x 20 cm

54 The Dancer, c.1928 Conté on paper, 25.3 x 20 cm

The Scottish Gallery window, Castle Street, Edinburgh, c.1975

The Scottish Gallery window, Castle Street, Edinburgh, c.1975

John Duncan Fergusson was born in Scotland of Highland parents; he worked in Paris and the South of France until 1914, and later in London. He held fourteen solo exhibitions in London, the first at the Baillie Gallery in 1905. Elected Sociétaire of the Salon d’Automne, Paris, 1909, first American Exhibition, New York, 1926. Exhibited with Les Peintres Ecossais Galeries Georges Petit, Paris, 1931, when a painting was acquired by the Luxembourg. He was represented by The Scottish Gallery with his first solo exhibition held in 1923.

1874 Born in Leith, Edinburgh, 9 March.

c.1895 Decides to pursue art full-time. After a short spell as a student at the Trustees Academy, leaves to become self-taught.

1896-1901 Visits France, Spain and Morocco.

1898

1900-1905

Exhibits watercolours of French subjects at the Royal Scottish Academy and the Society of British artists.

Annual painting holidays to coastal resorts of north west France with S.J. Peploe (1871-1935).

1902 Moves to first studio in Picardy Place, Edinburgh.

1903 Elected member of the Royal Society of British Artists.

1905 First solo exhibition at the Baillie Galleries, London.

1906 Spends summer with S.J. Peploe touring the Normandy coast. Meets American artist Anne Estelle Rice (1877-1959).

1907 Settles in Paris. Exhibits at the Salon d’Automne for the first time. Teaches part-time at the Académie de la Palette.

1908 Elected Sociétaire of the Salon d’Automne.

1909 Group exhibition alongside Frances Hodgkins, at Modern English Watercolour Society.

1910 Paints with Peploe and Rice in Royan.

1911 Launch of Rhythm magazine by John Middleton Murry and Michael Sadler in London, with Fergusson as Art Editor. Paints with Peploe in Royan.

1913 Meets the dancer Margaret Morris (1891-1980) in Paris who later becomes his wife. Four works included in the Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition, Doré Galleries, London. Visits Cassis with Peploe and Rice. Settles in Cap d’Antibes.

1914

1914-1918

1918

Forced to leave Cap d’Antibes on outbreak of First World War and returns to London to be with Margaret Morris.

The war years spent between his family and Peploe in Edinburgh and Margaret Morris in London.

Commissioned by the Ministry of Information to make a series of paintings of life in naval dockyards, Portsmouth.

1922 Tours the Scottish Highlands with journalist and paints Highland Landscape series.

1923

1926-1928

1929

1930s

1931

First Scottish solo shows at The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh and Société des Beaux Arts, Glasgow.

Held two one man exhibitions in New York.

Left London to settle for second time in Paris.

Makes regular summer visits to the South of France. Acts as President of the Groupe des Artistes Anglo-Américains, Paris.

Les Peintres Écossais Exhibition, Galeries Georges Petit, Paris. Fergusson’s painting La Déesse de la Rivière purchased by the French Government.

1939 Settles permanently in Glasgow following the outbreak of the Second World War.

1940

1942

1943

1948

1950

1950-1960

1954

1961

Founds the New Art Club with Margaret Morris.

The New Scottish Group formed, comprising members of the New Art Club.

Modern Scottish Painting is published by MacLellan.

First major retrospective exhibition at the MacLellan Galleries, Glasgow.

Awarded honorary LLD by Glasgow University.

Annual trips to the South of France to teach and paint at Margaret Morris’s Summer Schools.

J.D. Fergusson Retrospective Exhibition (touring) Arts Council of Great Britain Scottish Committee.

Dies 30th January in Glasgow.

Published by The Scottish Gallery to coincide with the exhibition:

J.D. Fergusson | 150

30 April - 1 June 2024

Exhibition can be viewed online at: scottish-gallery.co.uk/jdfergusson

ISBN: 978 1 912900 83 1

Printed by PurePrint Group

Designed and produced by The Scottish Gallery

Thanks to Perth & Kinross Museums & Galleries.

All rights reserved. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced in any form by print, photocopy or by any other means, without the permission of the copyrightholders and of the publishers.

Inside front cover: Self Portrait, Paris, c.1910, Conté on paper, 20 x 12 cm (cat. 12)

Inside back cover: Self Portrait, c.1910, Conté on paper, 21.1 x 13.1 cm (cat. 13)