LIFE LIVED ON THE EDGE OF THE WORLD

The Northern Isles are two archipelagos off the north coast of mainland Scotland, comprising Orkney and Shetland. They are quite distinct, different from anywhere else, their complex histories as associated with the Viking period as with Scotland. Their Neolithic histories are rich, centuries of peace and prosperity which put them at the centre of Iron Age culture. Shetland displays the northern geology of Scotland in miniature: ancient Lewisian Gneisses and Dalradian rocks brought together with younger structures by north/ south faults continuing the Great Glen Fault. Orkney is made up of the Devonian sandstones giving rise to its dramatic sea cliffs. Add in the fierce exposure to ocean and sea and the distinct turn of the seasons shaping all life and we can understand the sharp sense that life is lived on the edge of the world. These beautiful, harsh islands have held a special appeal to artists for centuries. This exhibition brings together many of these, pioneers and natives from the past and present, many drawn back, some coming to make their lives, others benefiting from imaginative residencies. Poet, writer, and Shetlander Christine de Luca delivers a special insight into the people and the places on the following pages, alongside a dedicated poem to The Northern Isles.

Christina Jansen Shetland and Orkney images by The Scottish Gallery and Kenneth GrayTHE NORTHERN ISLES

BY CHRISTINE DE LUCA POET, AUTHOR, SHETLANDERTogether Orkney and Shetland comprise the Northern Isles of Scotland. However, both are archipelagos, each with its own group of northern isles. I cannot be the only person to think that ‘Orkney’ and ‘Shetland’ are corruptions of the original names of their respective ‘mainlands’: Hrossay and Hjaltland.

The shapes of these island groups have always fascinated me: Orkney stretching along a horizontal axis and Shetland more vertical, more leggy.

Outstretched below the isles of Orkney lie: skins of ancient monsters patterned wildly. Long sinuous members, golden fringed … (from ‘Airborne over Orkney’, Voes & Sounds)

Shetland is geologically and topographically more diverse than Orkney. Its hilly, loch-strewn landscape is more ice-scoured, its coastline more penetrated by ‘voes’ (sea lochs), and its west coast particularly fretted by deep, narrow ‘geos’ and a scattering of stacks. Orkney is lower and greener with a chequerboard of small farms, while Shetland – other than the southern ‘Ness’ area – has small crofts eating into rougher moorland. Both island groups have fine sandy beaches.

In this extract, written in the Shetland tongue, I write of seeing the distant island of Foula, from the douce Ness, in wintertime:

A’ll start wi da horizon: draa a line caald enyoch ta stivven ivery vanishin point; far enyoch ta mark da aedge o da wirld.

A’ll mizzer Foula’s glansin distance as shö frets da skyline; laeve her dere, loomin, uncan, owre closs fur comfort: a mythic iceberg fae anidder wirld. (from ‘Owre closs fur comfort ‘, Parallel Worlds)

W hether visiting Orkney or Shetland, there can be a sense of ‘otherness’: perhaps it’s the wide open spaces where your eye can roam at will; or the subtle, ever-changing colours of land, sea and sky – back lit, low lit, sunsets so intense they look surreal. For artists, light is probably a major consideration, whether the long days of the ‘simmer dim’, the dark skies of midwinter or the moody mists that can hap the hills and roll down into summer valleys.

Or it might be the ‘speak’ of the local people; or the place names redolent of their Norse origins; or the juxtaposition of something very old and something strikingly contemporary.

There are strong similarities in the history and culture of Orkney and Shetland. Although Orkney is close to mainland Scotland, and has had more immigration than Shetland, it still retains its distinctiveness.

Both island groups are rich in archaeology – particularly Orkney. Both boast Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Age sites as well as much dating from the Viking era. The Earl’s Palace in Kirkwall and the beautiful red sandstone cathedral dedicated to St Magnus remind us of the pivotal position of Orkney during the Viking era.

Shetland was enroute to Faroe, Iceland and Greenland so it too was important to the northern ‘Jarls’. Both became strategically important during the two World Wars and now Shetland has been selected for a satellite launch pad. The encounters between ancient and modern continue. It’s not so long since electricity was laid to outlying places yet both are now leading in green energy developments.

While the traditional pursuits of farming and fishing face continual challenges from weather, markets and transport costs, they are still the foundation of the local economies. Orkney excels in meat, cheese and whisky while Shetland sends wild-caught fish, farmed salmon and mussels all over the world.

There is a long tradition of world-class craft skills: Orkney known for its silverware; Shetland for knitting. And both have an amazing musical heritage.

Tourism, with all is paradoxes and contradictions, is now a major contributor to both economies, with cruise-ships calling along daily in summer and many jobs now dependent on serving the needs of visitors.

Being somewhat adrift from mainland Scotland – Shetland’s latitude is similar to Helsinki, Bergen and the southern tip of Greenland – has perhaps encouraged in islanders a focus on self-reliance, community cohesion and a certain independence of mind. Yes, it’s seen as a bit other-worldly, a bit ‘on the edge’, and film-makers tend to get it wrong to please that appetite to the point of caricature, but these are deep-rooted, practical, hard-working places with a people who, while they embrace relative prosperity, know that the lives of their grand-parents or great-grandparents were hard. But, they know too that the world of the arts – particularly the story-telling and fiddle music of the past – enriched the souls of the people and that art and culture are still vitally important to well-being and social cohesion.

Our contemporary painters continue to find inspiration in the unique landscape, the geography, history and rich culture of Shetland and Orkney.

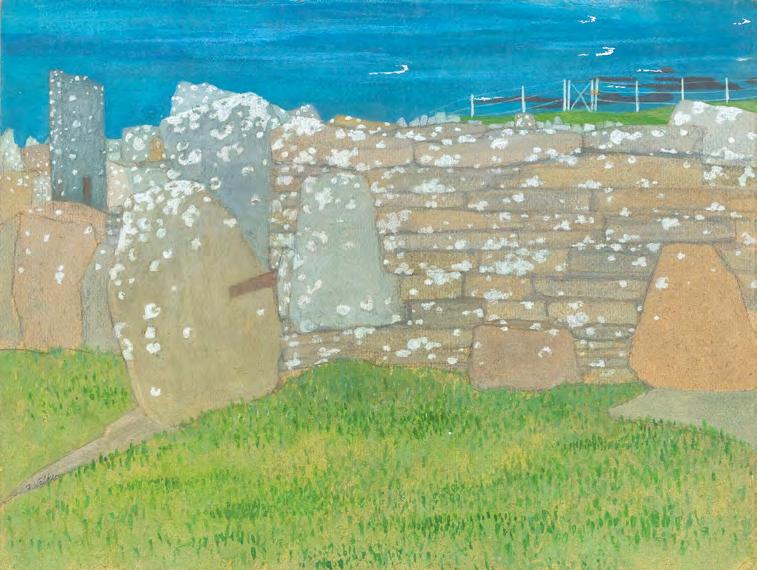

Tangwick, Shetland

Tangwick, Shetland

BEYOND PERSPECTIVE

The Northern Isles

Skies that defy reality: watery or inky, occasionally opulent or soft buttermilky. But they change quickly to sulks and sombreness.

The wind dictates mood from raem calm to sea-shatter. You walk the edge, hold your breath, dodge spume. Yesnaby, Birsay, Fitful, Aeshaness: battered margins.

It’s the light that catches: the way it plays on water, melds sky with horizon, glitters vistas till clouds roll in or build, till sea darkens and land hunkers.

Patterns of the past: of hard-won pickings from tough land, capricious sea –Scatness, Mousa, Gurness, Skara Brae; history worn wildly, ancient of days.

They may all resist you. Christine De Luca raem: cream (i.e. smooth as cream)

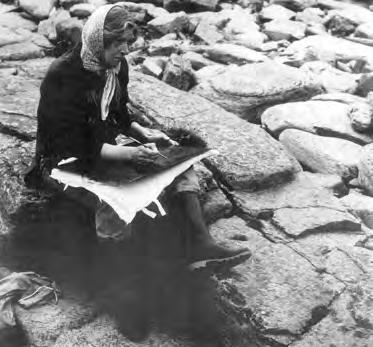

Victoria Crowe on the Cliffs at Yesnaby, Orkney Photograph: Kenneth Gray

Victoria Crowe on the Cliffs at Yesnaby, Orkney Photograph: Kenneth Gray

THE NORTHERN ISLES

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912-2004)

Alex Boyd (b.1984)

Ruth Brownlee (b.1972)

Anne Campbell (b.1957)

Victoria Crowe (b.1945)

Peter Davis (b.1953)

Pat Douthwaite (1934-2002)

Kate Downie (b.1958)

Laura Drever (b.1981)

Ian Fleming (1906-1994)

The Orkney Chair

David Kirkness (1855-1936)

Kevin Gauld (b.1980)

Kenneth Gray (b.1969)

Sylvia Hays (b.1938)

Diana Leslie (b.1971)

Ron Sandford (b.1937)

Frances Scott (b.1991)

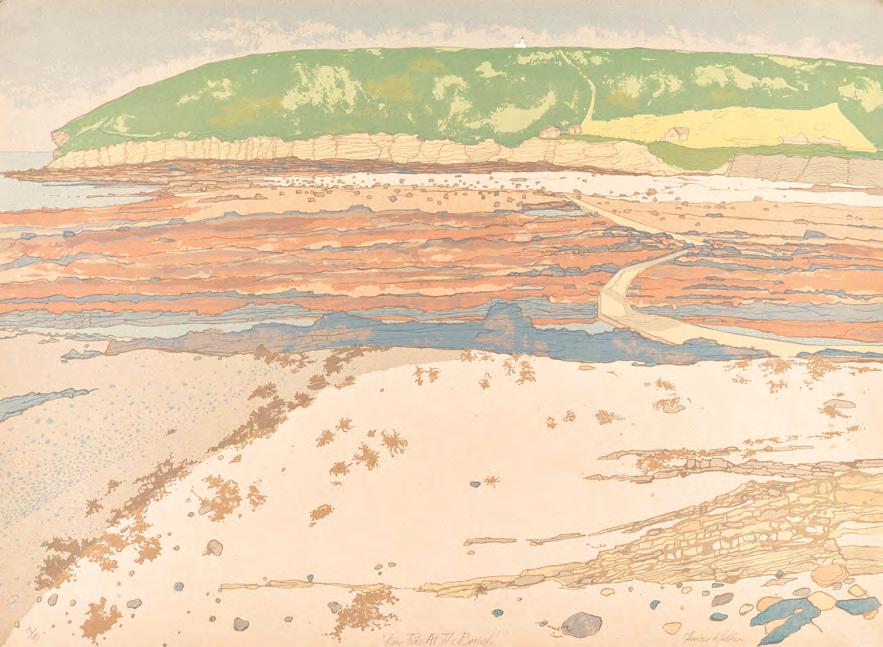

Frances Walker (b.1930)

Sylvia Wishart (1936-2008)

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham was the subject of an exhibition at the Pier Arts Centre on Orkney in 1984. Rather than returning immediately to St Andrews, she decided to stay on, remaining in Orkney for a further seven weeks. Ensconced as Artist in Residence at the Pier Arts Centre, she experienced an extraordinary freedom, unfettered from the regularities of her usual studio life. The Orkney landscape was subsumed into her art practice. She worked simultaneously within widely different visual styles, between the bounds of the literal and the abstract, indicating how comfortable she was in operating in both spheres, and that she had no, and saw no, difficulty in doing so.

So much work ideas are here – drawings, colour, shapes, moods, space – elongated shapes + then the light + rock groupings –water movement – changes. It is overwhelming – choked with it all. Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, c.1984

Two Island Series (No.2) Orkney, 1987 oil and pencil on hardboard, 29.8 x 60.8 cm

WILHELMINA BARNS-GRAHAM (1912-2004) CBE, HRSA, HRSW

September Orkney, 1985-86 gouache on paper, 47.3 x 57.1 cm

Orkney, 1984 pencil and oil on paper, 17.7 x 22.8 cm

ALEX BOYD (b.1984) FRSA, FSAScot, CF

Alex Boyd’s images represent a major addition to the tradition of modern landscape photography. Robert Macfarlane, Author

Alex Boyd is a landscape and documentary photographer, printmaker and writer. His work is concerned with landscape, identity and land ownership, themes he has explored with collaborators such as Edwin Morgan and musician Nick Cave. His work examines the role of early Scottish landscape photographers, often using antique processes such as the Victorian ‘wet-plate collodion’ process using plate cameras on mountain tops.

His series on the Cuillin mountains on the Isle of Skye during his RSA’s Residency in 2013 is held in several national collections including the National Galleries of Scotland, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, Victoria & Albert Museum, London and The Yale Center for British Art, USA.

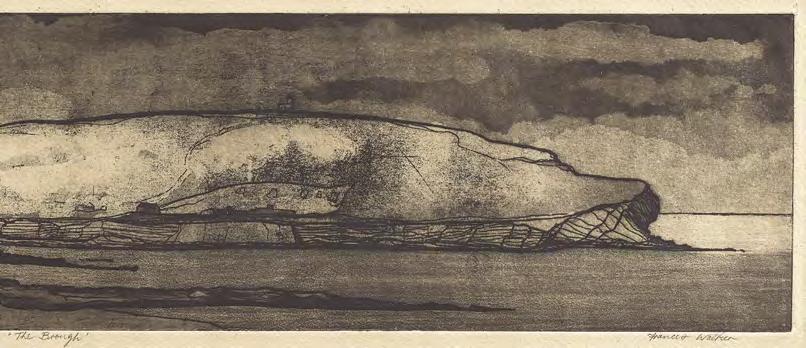

Sonnets - The Old Man of Hoy, 2013 silver gelatin print, 30 x 20 cm

I had gone to see where Peter Maxwell Davies had made his home and created some of his most memorable work, where Sylvia Wishart has painted, and where the path leads along the coast to the towering monolith of the Old Man of Hoy.

There is of course another side to Orkney and Shetland, with their northerly position giving them a prominent role in the conflicts of the 20th century. The wrecks of Scapa Flow had always held a particular fascination with myself and my older brother, an officer in the German Navy. The fate of the High Seas Fleet, scuttled to preserve its honour, providing a point of pride.

This image is part of a wider project looking at the role the North Atlantic has played in the defence of the United Kingdom, largely focusing on the landscapes of the Cold War. Alex Boyd

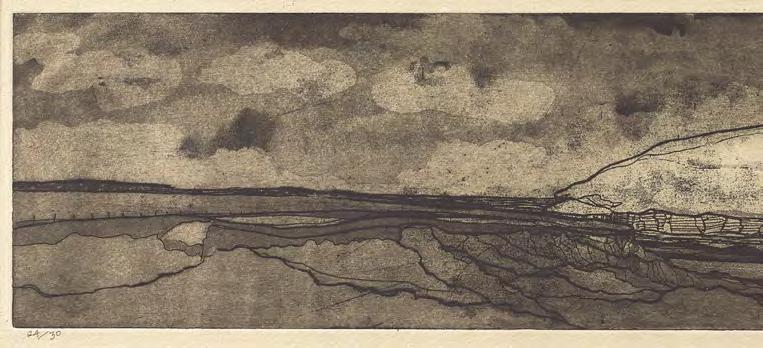

North Atlantic - The Faroe Shetland Channel, 2015 c-type print, 50 x 70 cm

The Neuk - Hoy, Orkney Islands, 2013 silver gelatin print, 30 x 40 cm

RUTH BROWNLEE (b.1972) SSA

Having lived by the sea since visiting Shetland to teach a painting workshop 24 years ago, my work continues to be inspired by this archipelago in the North Sea. Shetland is a rugged environment with an intense visual drama of constant changing elements. As I love walking and walk whenever I can; I watch the weather, and read the mood of the sea which filters into my studio practice. Capturing the intense atmosphere of this wild place is more important to me than trying to include the details of the coastal landscape. Ruth Brownlee

Born near Edinburgh in 1972, Ruth Brownlee graduated from Edinburgh College of Art in 1994. In 1998, she moved to Shetland. Her work is included in the public collections of The Fleming-Wyfold Collection, London, and Shetland Museum.

Clearing Gale, Cunningsburgh Banks mixed media on board, 26.5 x 26.5 cm

Incoming Rain, West Voe mixed media on board, 27 x 28 cm

Midsummer

ANNE CAMPBELL (b.1957)

Anne Campbell has worked as an artist and photographer for over twenty years, living and working in the Northeast of Scotland, where she has a studio in the village of Monymusk. She currently teaches photography at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen. Anne specialises in traditional and experimental darkroom processes to explore the Scottish landscape and capture the fragile northern ecosystems of the Highlands and Islands. Working with film and chemical processes, (layering and exposing different areas of the print by the use of bleaching and redeveloping), allows for the creation of textural layers, creating one- off, subtle yet complex images, that mirror the atmospheric and changeable weather systems, the landscape and her response to it; the transitory nature of human presence. The surface qualities can be painterly and descriptive of personal experience or may mirror the visceral qualities of nature: they can reference the past while looking to the future.

Shetland and Orkney, these northern isles, so different but enchanting in their own unique ways. Living in the northeast of Scotland I have been fortunate to visit them on many occasions, including exhibiting with fellow photographer and Shetlander, Chloe Garrick, in the Shetland Museum & Archives Gallery in Lerwick. These two distinct island groups evoke very different feelings: Shetland, more remote, feels wilder, with its jagged, brown cliffs and varied contrasting landscapes. The Orkneys, softer and greener, feel like they sit sandwiched between sea and sky as the weather rolls across, the clouds mixed with sea spray. I have tried to capture this in ‘West Across the Atlantic’ as I watched the rain clouds roll in from the ocean. The image of Foula, taken from mainland Shetland on a rare windless day, is an attempt to capture the timeless, magical and otherworldly sense of being, when visiting these islands on the edge.

Anne CampbellWest Over The Atlantic, Orkney, 2013 handprinted analogue photograph, 22 x 29 cm

VICTORIA CROWE (b.1945)

OBE, DHC, FRSE, MA(RCA), RSA, RSW

Victoria Crowe was awarded the RSA/Pier Arts Centre Residency earlier this year: she stayed at the Linkshouse artists residence in Orkney.

I worked from the looming landscape and cliffs surrounding the studio and began a series of works about the late and lingering solstice sunsets around the Brough of Birsay. The cloud formations were spectacular and varied, sometimes looking like great snowfields illuminated from within, and at other times immense distances opened up fleetingly behind bands of fast moving horizontal cloud.

Victoria Crowe

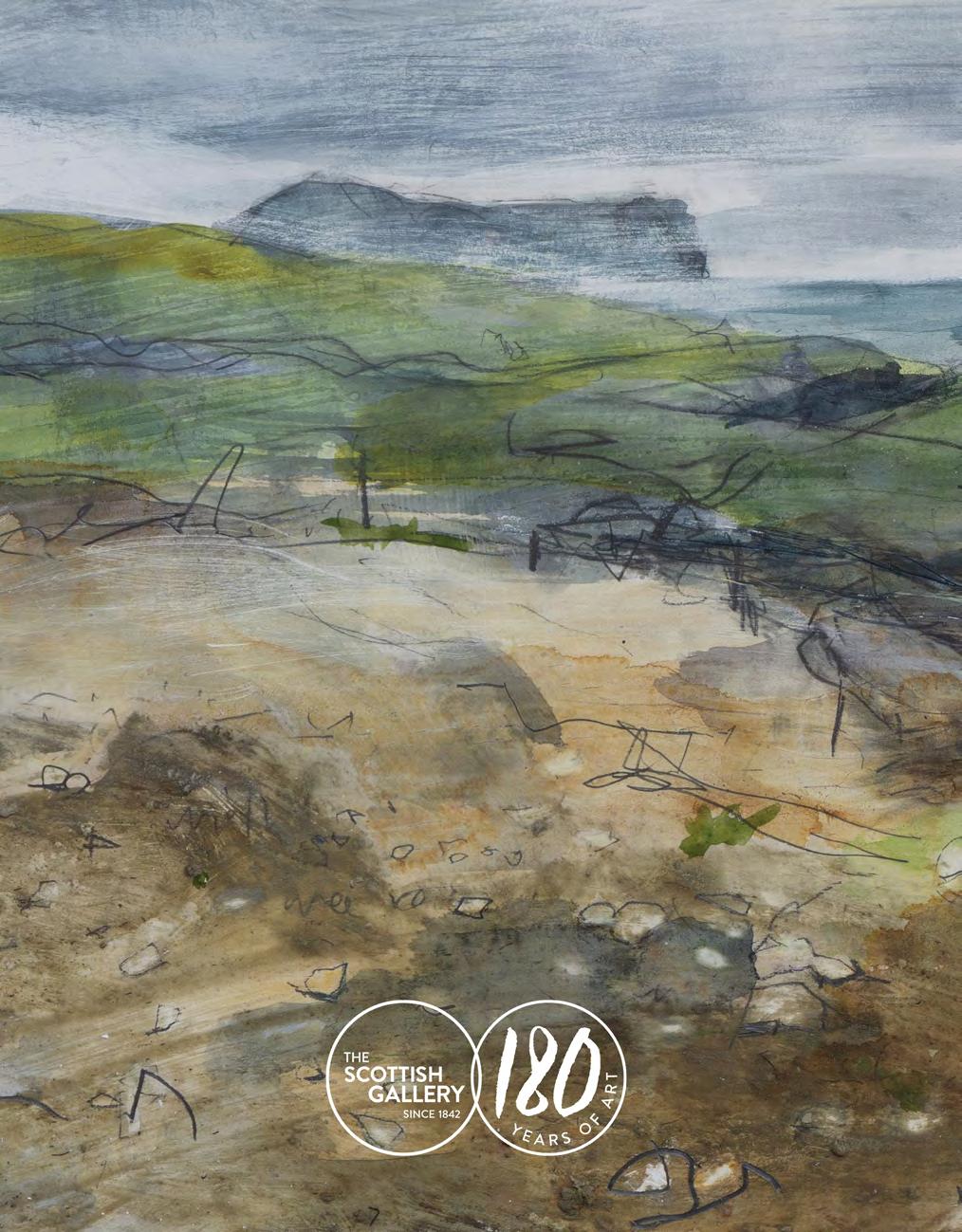

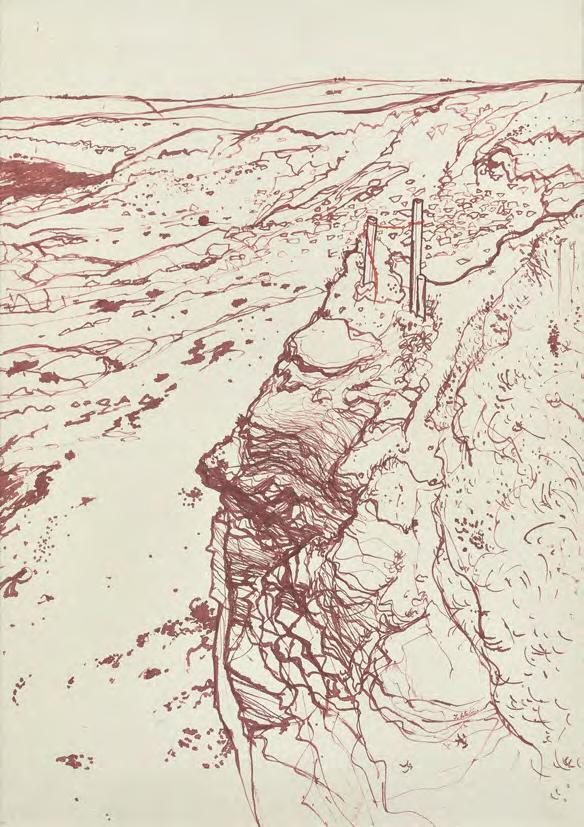

Cliffs near Yesnaby, 2022 ink and acrylic on Chinese rice paper, 30 x 45 cm

Late Evening with Rushing Clouds, 2022 acrylic on paper, 31 x 40 cm

Bands of Cloud after Sunset, Birsay, 2022 acrylic on paper, 41 x 30 cm

PETER DAVIS (b.1953)

There’s a point at which the act of painting and the inherent action of nature align themselves and that frequently happens in watercolour. I consider it the most natural of all the painting mediums, comprising pigment, a binder which is mainly gum arabic, and water, the drying process leaving the pigment on the surface. The two extremes of stillness and flow and the myriad activity between the two are what make watercolour, for me, the most natural medium with which to depict the extremes of the Northern landscapes. I have painted this subject for over 40 years, and it continues to provide a source of excitement and exploration. I have no wish to simply record what I see. I do not seek sedate topographies often associated with the term ‘watercolour landscapes’. Instead, I prefer the uncertain balance between abstraction and reality. Peter Davis

Peter Davis was born in North Shields and studied art and design at Northumberland College of Education, graduating in 1975. He has spent a large part of his career teaching art and design in the Orkney Islands from 1982-1991 and began teaching in Shetland from 1992. He has been painting full time since 2013 from his studio in Shetland. He has exhibited in the Northern Isles, the UK and internationally.

Hoolan (Silwick),

and chalk on paper,

x

cm

Davis’s palette is naturally subtle and finely nuanced, allowing space for each physical element within the picture plane; white paper, water and pigment to be mindfully observed, creating a space for the intellect and the imagination to dive into. Georgina Coburn

19

Skyued, 2022 watercolour, bodycolour and chalk on paper, 50 x 70 cm

PAT DOUTHWAITE

Orcadian Landscape is Pat Douthwaite at her most abstract, exaggerating the absence of features. She visited friends on the Island in 1999 and this watercolour appears to have been painted from the inside looking out; this is how she sees the harsh landscape in poor weather – it is not an oppressive image but rather, quite beautiful. The land, sea and sky appear in subtle bands.

Orcadian Landscape, 1999 watercolour, 61 x 49 cm

KATE DOWNIE (b.1958) RSA, PPSSA

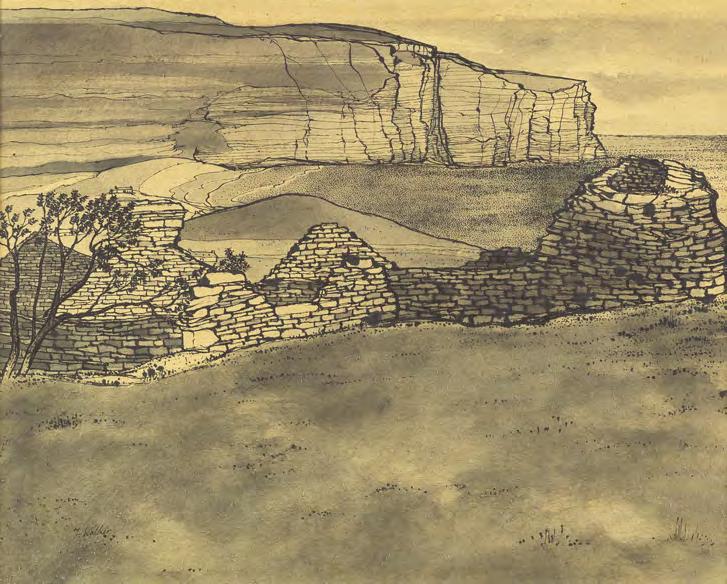

It was a delight to return to Orkney with its endlessly varied weather patterns, each iteration of the light, sky, clouds, as weather fronts blew in across the Atlantic, changing from one minute to the next. We were treated to exquisitely long days, endless sunsets, light peeping through blinds and the cry of strange birds. Wild blowing grasses and a view across to Hoy separated by the pattern of everchanging light on the sound. I explored ancient Brochs, standing stones and continuously uncovered Neolithic sites. The very place names carry poetry, spirits and history in the humblest windswept nooks.

Kate Downie

Norseman Village, 2022 ink and watercolour on gesso ground on wood, 30 x 50 cm

I became fascinated by the way that the wind shapes the trees of Orkney. Many folk believe that Orkney has no trees but I was humbled to happen upon (far more in the landscape than I remember from my first visit in the 1980s) these plucky small woods coory-ing in together for protection, wind sculpted into shapes that echo the hills and waves. Inside these taut leafed canopies

is shelter for birds, wild flowers and humans alike. Happy Valley was a special oasis in the lee of a hill near Stenness, a special place created by a farsighted Orcadian started over 70 years ago.

Kate DownieRendezvous in Happy Valley, 2022 tempera and watercolour on gesso ground on wood, 31 x 50.5 cm

These three pictures were both drawing board and paper in one, made for coping with the vagaries of wind and weather in the landscape. Gesso on wood, ready to absorb all the elements and yet give me freedom to experiment. No flapping paper but a sturdy surface delicate enough to catch the very subtle beauty encountered by an outdoor artist on her northern travels. Kate Downie

Yesnaby to Hoy, 2022 graphite and watercolour on gesso ground on wood, 31 x 50.5 cm

Danyal

LAURA DREVER (b.1981)

Laura Drever was born in Kirkwall, Orkney. Laura studied Drawing and Painting at Edinburgh College of Art and works from her studio in Kirkwall. For nearly twenty years Laura has been exploring the changing nature of her native islands. By walking over and through the landscape the artist has come to a deep understanding of the fabric and form of the hills, valleys and seascapes around her. She has exhibited regularly throughout the UK, and takes an active role in Orkney’s creative community. Laura is Chair of Soulisquoy Printmakers, delivers creative workshops and nurtures others through short residencies with locally based arts organisations.

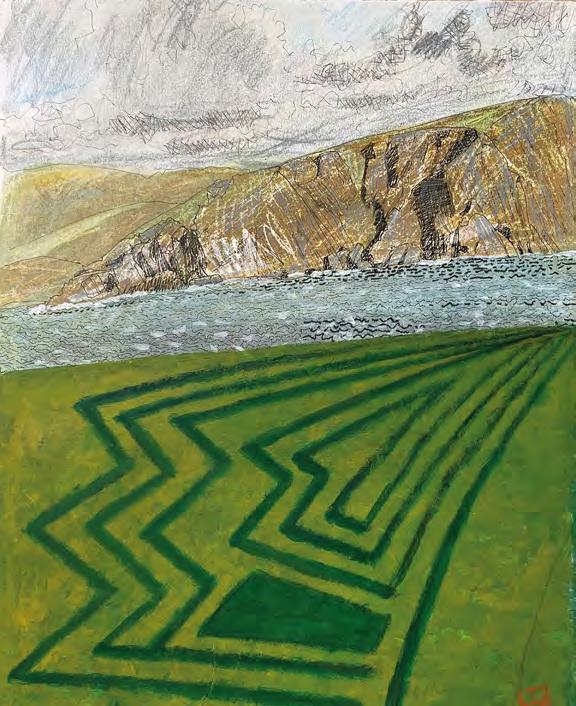

The modern Orkney landscape is characterised by the agricultural developments of the last 150 years or so, which saw a complete transformation in appearance from common grazing and piecemeal cultivation, to squared-off, drained and ordered fields. The higher up and more difficult to reach places, that proved impossible to put under the plough, endured, and most outlooks across the islands are capped by a contrasting layer of rough grass and heather. It is to these more rugged and untamed landscapes that Laura Drever is most often attracted… [and her paintings] offer a sense of the geology of these unpeopled landscapes and, through the artist’s careful modulation of tone and colour, a feeling of slowly evolving space. Extract from Teebro, New Work by Laura Drever, Andrew Parkinson, The Pier Arts Centre, 2022

base,

IAN FLEMING (1906-1994) RSA, RSW

Ian Fleming was born in Glasgow in 1906 and studied at Glasgow School of Art during the 1920s before joining their staff in 1931.

In 1954, he relocated to Aberdeen as Principal of Gray’s School of Art but continued to pursue his painting practice alongside his academic commitments. He was elected a full Academician of the Royal Scottish Academy in 1956, and by the time of his death was the longest-established member. The fishing towns of Angus and Kincardineshire were to be his inspiration for many post-war paintings in which he celebrated the colour, forms and architecture of the working harbour communities.

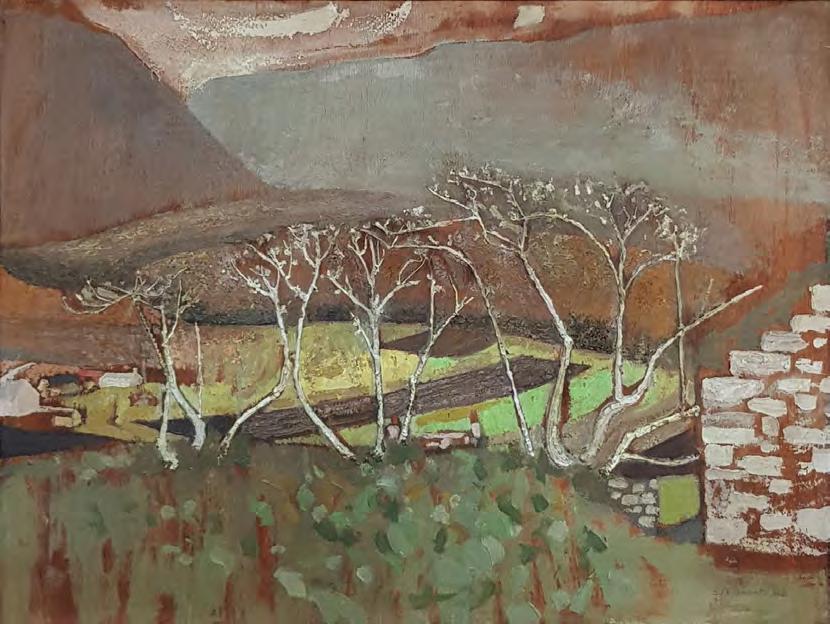

Like his work in the fishing villages of the east coast, SleetFalling, Shetland presents Fleming’s interest in capturing the texture of the landscape, the receding cottage roofs and fields providing exciting formal relationships.

Sleet Falling, Shetland oil on canvas board, 74 x 59 cm

THE ORKNEY CHAIR

The Orkney chair is probably one of the most iconic pieces of Scottish vernacular furniture. Now highly collectable (with examples in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London) Orkney chairs were originally made with a very practical design. The chair style that we know today was standardised in the mid-19th century by David Kirkness of Kirkwall. It is assumed that a straw back was used in the Orkney, Shetland and Fair Isles as few trees can grow due to the extreme weather conditions. The earlier examples usually have frames made from driftwood, which was gathered from the coastline. The making of these chairs is a very sophisticated and time-consuming process. Firstly, the back consists of a coil of straw – which is one continuous rope. In other traditions of making this type of rope or coil a template would be used to ensure consistency, but not with Orkney chairs – it is done by the eye of the chair maker. Marram or bent grass is used to tie the chair to the uprights of the chair. When the shaped back

is being made, the chair maker would grab a fistful of oat straw which has been threshed differently than regular straw, to ensure the minimum number of breaks in the stalks. Working with the straw the chair maker starts the process of coiling, winding and tying. The first row is held in place by nails and thereafter held in position by different types of sea grass.

27 Oak-Framed Orkney Chair by David Kirkness, c.1930s

An oak-framed Orkney chair stamped to the underside of the front rail by David Kirkness. The chair of traditional form with oak straw back held and tied with marram grass. The two shaped arms with a classic Kirkness curve at the end held in place by simple uprights. The drop in marram grass seat framed in oak. Back legs are square tapering and front legs square tapering and slightly put swept, intersected by conforming stretchers. H85 x W54 x D53cm

PROVENANCE

Georgian Antiques, Edinburgh

The Orkney chair is probably one of the most iconic pieces of Scottish vernacular furniture.

The Orkney chair is probably one of the most iconic pieces of Scottish vernacular furniture.

A Scottish Oak-Framed Orkney Rocking Chair, c.1950

The woven oak straw back and open arms above a drop-in bent grass cord seat on square tapering supports linked by stretchers and raised on rockers. Stamped D Kirkness on front rail.

H65 x W40 x D50 cm

Georgian Antiques, Edinburgh

Some Orkney chairs have solid seats and others have woven seats made from marram or bent grass. Most of the earlier Orkney chairs had solid seats and often have box panels on the front and sides, to keep off draughts and reflect heat from the fire. On occasion, you do find Orkney chairs with a little drawer on the front or side. This would have been used for the storing of documents, or perhaps a bottle of whisky or a bible. In Northern dialect the chairs are known as stuls (stools), and an Orkney chair with a hood would have been called a heided-stul, enclosed to provide further protection from draughts. The chairs range in size from very small for children, mid-sized, to large sized ones, and there are even the odd rocking versions. So popular were Orkney chairs at the turn of the last century that Liberty & Co., sold them in their London shop. They asked the maker (David Kirkness) to put a slight curl at the end of the arm to stylise the chairs a bit more, this has become a standard feature on the chairs today. Members of the Royal Family were collectors at the beginning of the last century.

Nest of 3 Orcadian Stools by David Kirkness, c.1950

An unusual nest of three Orcadian stools by David Kirkness of Kirkwall. The seats of typical Orcadian style in woven marram grass with square blocks in each corner. The two smaller stools nest neatly beneath the double top, all standing on square legs with a slight chamfer towards the toe, intersected by simple stretchers.

H44 x W81x D36 cm

Georgian Antiques, Edinburgh

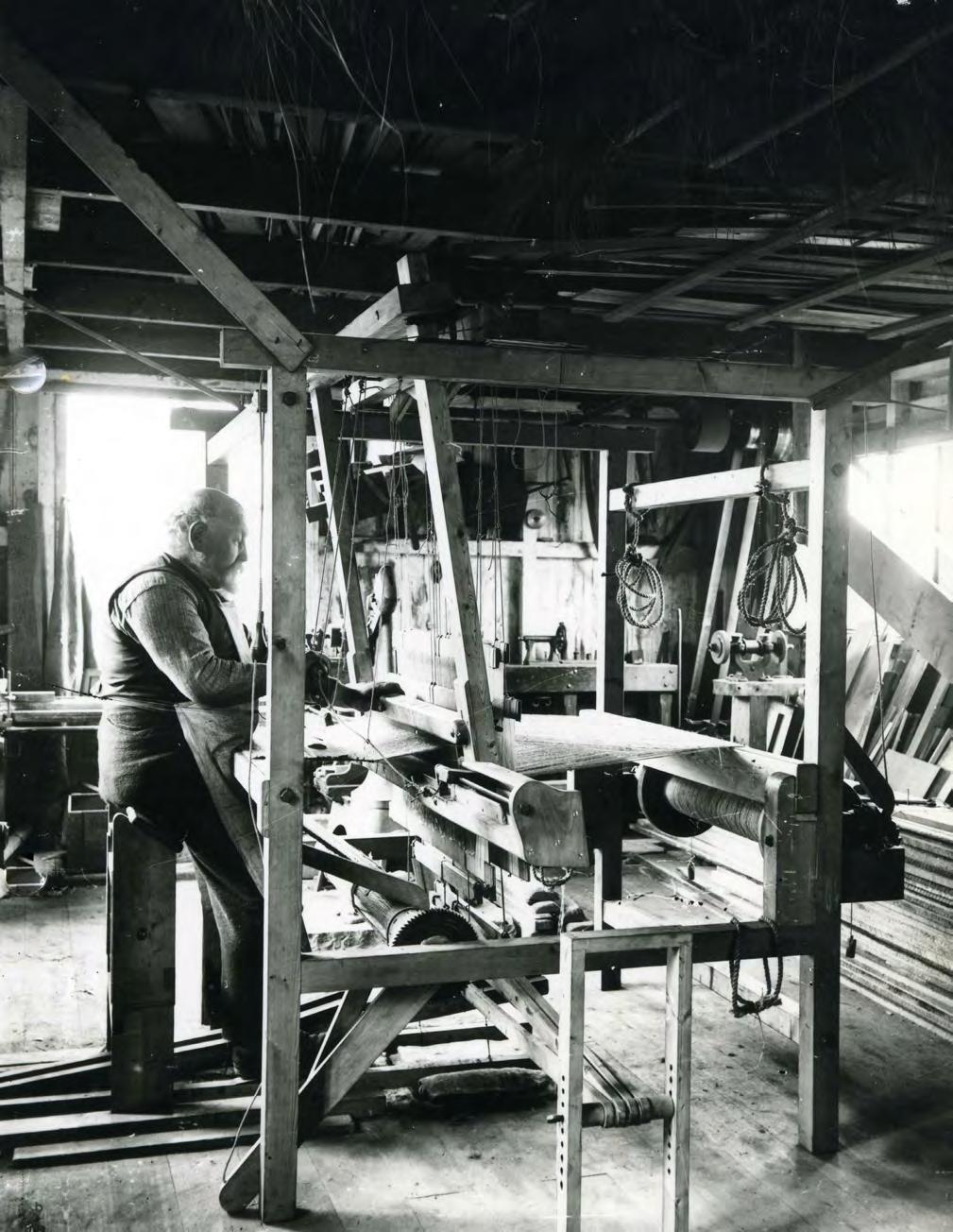

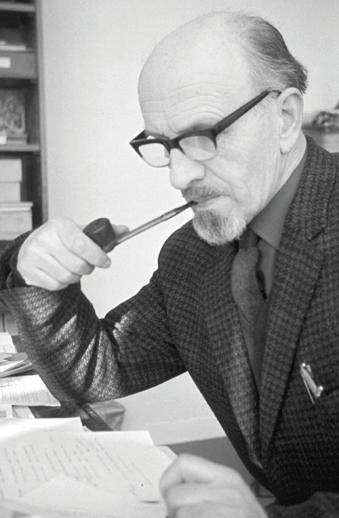

Tom Kent, David M. Kirkness using a Weaving Loom, Orkney Library & Archive

Tom Kent, David M. Kirkness using a Weaving Loom, Orkney Library & Archive

Kevin Gauld in his Kirkwall Studio, Orkney

Kevin Gauld in his Kirkwall Studio, Orkney

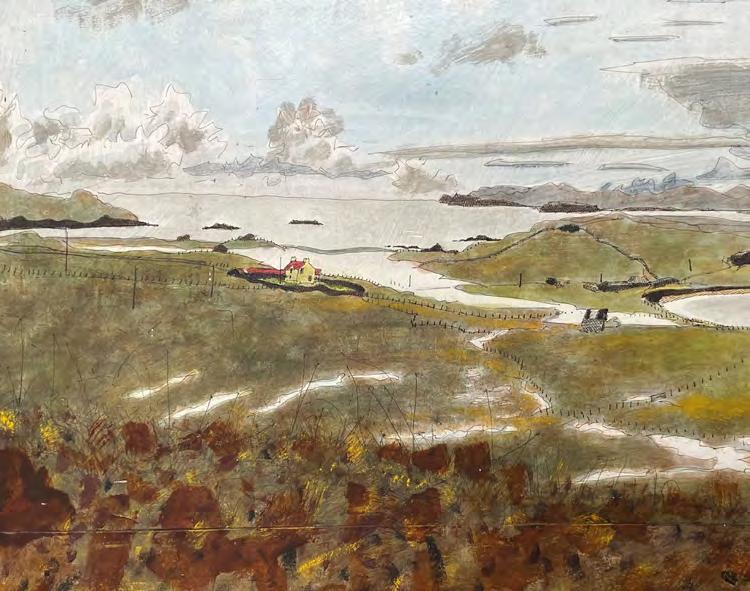

Scarvister, Shetland

Scarvister, Shetland