TEN YEARS OF MODERN MASTERS

16 Dundas Street Edinburgh EH3 6HZ +44 (0) 131 558 1200 scottish-gallery.co.uk

We open 2023 with Modern Masters. It is ten years since we first launched the series, which has done much to celebrate Scottish painting and highlight the history of The Scottish Gallery. The Aitken Dott provenance and The Scottish Gallery back label, changing over the decades, is a reminder of our association and close bond with a broad range and huge number of artists. Every day, a picture or object whose origins lie at The Gallery will be sold in Scotland, the UK and worldwide. If the artists describe the world we live in, then by equal measure, acquisitions describe who we are – pictures and objects leave traces wherever they go.

Modern Masters allows us to explore The Gallery’s history, providing academic notes and provenance information from our unique daybooks and archive, the accumulation of publications now providing a real insight and contemporary dialogue into 20th Century Scottish art.

For this anniversary edition we have an exceptional collection of paintings, tapestry, and furniture. We pay a modest tribute to The Scottish Colourists, who were among the first artists to lead The Scottish Gallery’s programme of curated solo exhibitions. There is work by Aleksander Zyw, which provides an understanding into the small but vital role The Gallery played during and after World War II, when artists forced to flee Europe found their way to Scotland, and we provided a home for their art. We present a Joan Eardley collection which includes one of her finest seascapes from Catterline, alongside a double-sided portrait from her other most celebrated subject, Townhead, Glasgow. The Edinburgh School and wider circle as ever play a key part: Henderson Blyth, Johnstone, McClure, MacTaggart and Philipson are all represented, offering a reminder of the importance of the painting schools of Scotland. There are

several significant landscape paintings by the late, great James Morrison, following our celebration of his life and work last year, an artist represented by the Gallery since 1959. We also have two rare examples from Victoria Crowe’s A Shepherd’s Life series contrasted by an enigmatic portrait painting from her Venice studio. Modern Masters has not been without controversy. Modern Masters Women in 2020 caused a national stir, demonstrating that a small independent gallery could generate local, national, and international recognition for highlighting something extraordinary: we sat women artists alongside their peers, placing women at the centre of the art market decades before the broader art establishment. The art market in Scotland continues to be defined by our work. There are many routes to art but there is only one The Scottish Gallery.

We believe in creative collaboration, and we have teamed up with Georgian Antiques and Dovecot Studios, both based here in Edinburgh. We have furniture by the historic makers Whytock & Reid, whose archive and name was recently acquired by John Dixon at Georgian Antiques. We also present an important tapestry designed by Humphrey Spender and woven in 1951 at Dovecot, juxtaposed with a contemporary gun-tufted rug designed by Linda Green.

However, the greatest collaborators are my fellow Directors at The Scottish Gallery –Guy Peploe, Tommy Zyw and Kirsty Sumerling. All my colleagues are unsung heroes; each of the team brings specialist knowledge, dedication and creativity and make us who we are today. It’s a labour of love.

Robert Henderson Blyth (1919–1970) 6 Donald Morison Buyers (1930–2003) 8 Victoria Crowe (b.1945) 10 Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002) 20 Kate Downie (b.1958) 22 Joan Eardley (1921–1963) 26 Ian Fleming (1906–1994) 44 Alexander Goudie (1933–2004) 46 William Johnstone (1897–1981) 48 David McClure (1926–1998) 50

William MacTaggart (1903–1981) 60 William McTaggart (1835–1910) 66 James Morrison (1932–2020) 68

Lilian Neilson (1938–1998) 82 Robin Philipson (1916–1992) 88

FCB Cadell (1883–1937) 94 JD Fergusson (1874–1961) 96 George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931) 98 SJ Peploe (1871–1935) 100

Duncan Shanks (b.1937) 102 Humphrey Spender (1910–2005) 106 Linda Green (b.1955) 112 Sylvia von Hartmann (b.1942) 114

Aleksander Zyw (1905–1995) 116 Whytock & Reid | Georgian Antiques (est.1807) 120

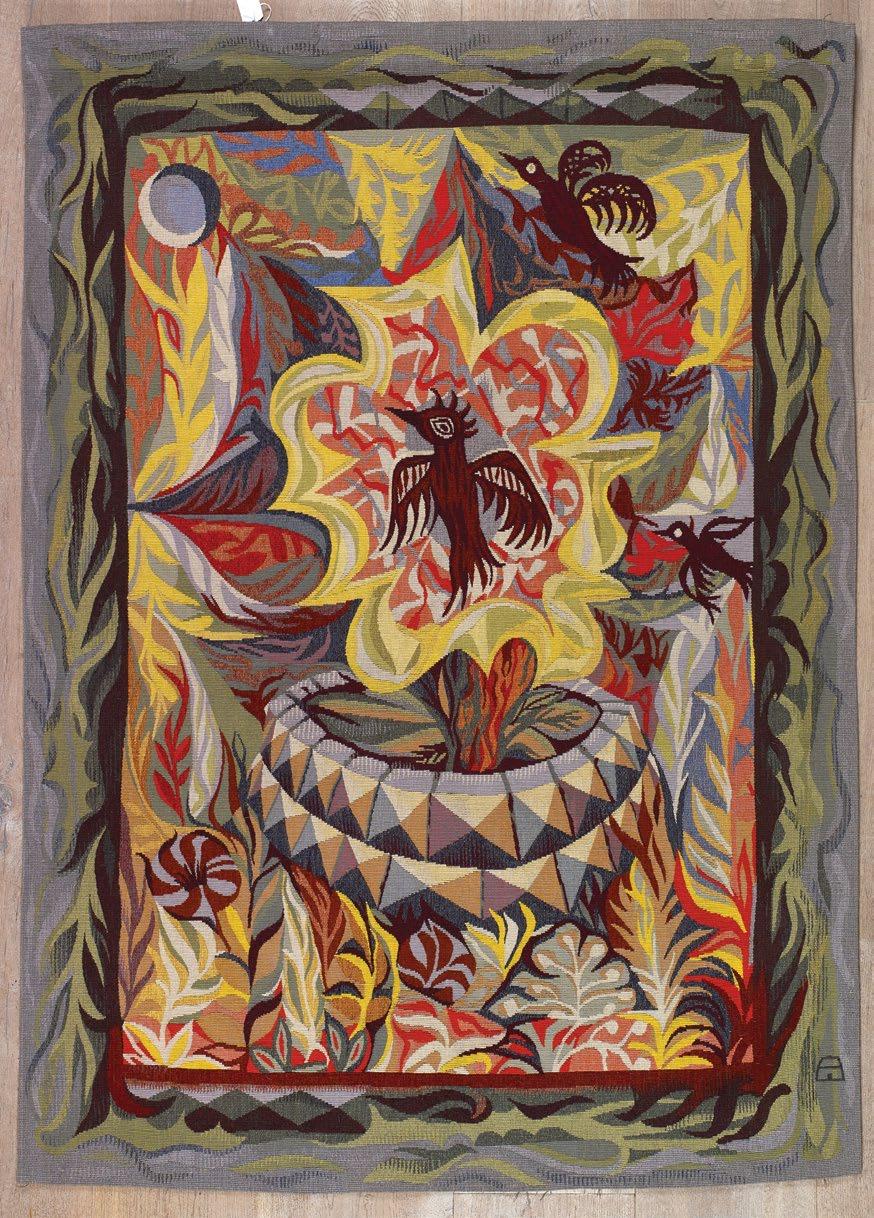

Opposite: Detail from Phoenix (Blackbird), 1951, by Humphrey Spender. Tapestry woven by Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh (cat. 44) (detail)

(1919–1970)

In The Road to Fochabers, Blyth has placed himself in the country hedgerows of near Elgin, the low evening sun illuminating the high ground, plunging the rest into shadow. He has sought to capture the texture of the landscape, indicating the long grasses by drawing into the wet oil paint with the back of his brush, a technique much favoured by his direct contemporary Joan Eardley. Like his friend and colleague Ian Fleming, Bobby Blyth moved to Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen by ways of Glasgow and Hospitalfield House near Arbroath. He became Head of Painting at Gray’s in 1960 before his premature death in 1970. He was a painter’s painter and was renowned for his brilliant, original draughtsmanship and eye for compositional design. Like Fleming, Blyth found much of his subject matter in the landscape of Aberdeenshire.

Robert Henderson Blyth RSA, RSW (1919–1970)

1. The Road to Fochabers, 1965–70 oil on board, 56 x 98 cm signed lower left

provenance

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

Robert Henderson Blyth at Edinburgh College of Art, 1946.

RSW (1930–2003)

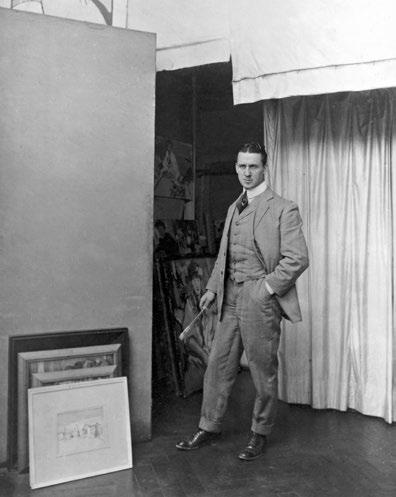

Corn Stooks, Aberdeenshire of 1962 owes something to the Modern British period, to Nash, Christopher Wood, Gillies and perhaps Robert Henderson Blyth, who was by then living in Aberdeen. But more, it seems a heartfelt response to the autumn harvest, with a deep red rich light on the landscape. Donald Buyers was born in 1930 in Aberdeen where he attended the Grammar School and then Gray’s School of Art after which he assisted his tutor Robert Sivell in the murals at the University Union in Schoolhill. His was a quiet life, well lived, throughout which family and painting were his twin loves. A honeymoon in Paris turned into an extended stay and the School of Paris was always present in his work. Back in Aberdeen, he began to teach in schools: Robert Gordon’s and eventually as a visiting lecturer at Gray’s, but he never stopped working and exhibiting.

2. Corn Stooks, Aberdeenshire, c.1962 oil on board, 73 x 99 cm signed lower right exhibited The Rendezvous Gallery, Aberdeen provenance Private collection, Edinburgh

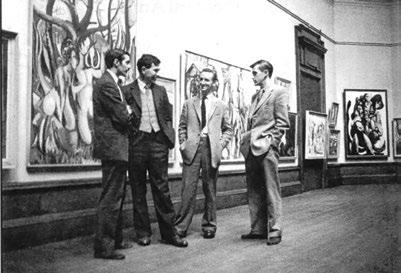

Donald Buyers at ABBO group opening, McLellan Galleries, Glasgow, 1960.

Donald Buyers at ABBO group opening, McLellan Galleries, Glasgow, 1960.

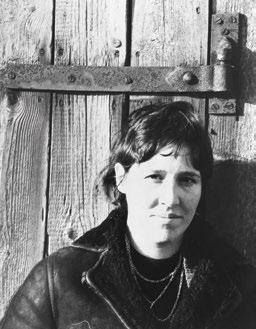

Victoria Crowe moved to Kittleyknowe in 1970 and lived there until 1990. She became good friends with her neighbour Jenny Armstrong who became the subject of a series of paintings known as A Shepherd’s Life. Victoria Crowe found the reality of life, harsh and idyllic by turn, around her new home in the Pentlands at Kittleyknowe, to be the roots of her development in Scotland, lending her the confidence and fortitude to develop into the great painter she is today.

‘The paintings and drawings recording Jenny and the surrounding landscape remain very personal and of great value to me. It was a period of my life when I was drawing and researching much of what was new to me. I wanted to respond to the environment that I found myself in, and to gradually make some sense of it in pictorial terms. Over those fifteen years shared with Jenny at Kittleyknowe, what began as a simple desire to record and understand a new environment, became a visual diary that also explored wider implications. The later paintings of the room, where light from the landscape asserts its dominance, are overlaid with references of memory and time. The painted interiors are, to me, parallel experiences to being with Jenny in that room – its contents and possibilities revealing themselves slowly. Watching Jenny at work and listening to her at home, had made me think of our relationship to the land, our impermanence vis-à-vis the enduring landscape and the rhythms of nature and season. Looking back to this recent past, there seemed to me a slowing of time, a chance to observe and reflect and to experience life unfolding almost in the way Jenny did, with an ease which worked with nature and the seasons as part of the continuum of time.’

Victoria Crowe, c.1972. Photograph courtesy of Michael Walton MBE

Extract from A Shepherd’s Life, Victoria Crowe, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 2000

Opposite: Jenny Armstrong at Kittleyknowe, c.1967.

OBE, DHC, FRSE, MA (RCA) RSA, RSW (b.1945)

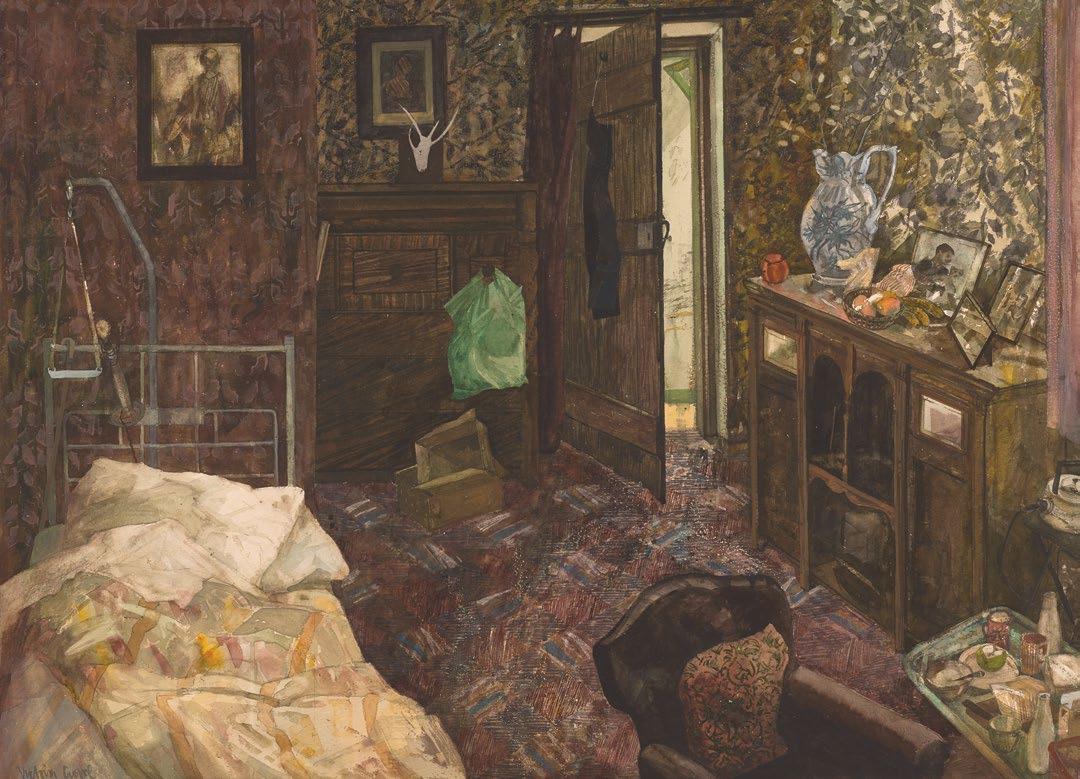

When Jenny Armstrong died in 1985, there was a short hiatus when the cottage was left empty, before it was eventually cleared and sold. Victoria Crowe had visited Jenny many times over the fifteen years from 1970 when the family moved to Kittleyknowe and apart from Jenny’s 18 months in hospital, her door which had always been open to visitors, was suddenly locked. The artist felt that the interior and all its resonances and memories of Jenny were lost until she was granted access for a short period of about a week before the cottage was sold. She began to photograph the interior, which was dimly lit, full of dusty sunlight or a cold snowlight and a glow from the fire. The black and white photos were disappointing, so Victoria returned to her drawn and observed studies of Jenny’s interior from over the years. From these she could see everything more clearly in her mind’s eye and she set about to recreate Jenny’s home. She made several large charcoal drawings (now in the collection of the National Galleries Scotland) and some oil paintings.

Victoria felt a great urgency to catalogue everything, to keep all those memories, to look at all the aspects of the room together. The bed is indicative of Jenny’s last months at Monks cottage, when a hospital bed had been made

available to her. There is an old table lamp tied on with string so that Jenny could have light handy; above the bed is the framed photo of her as a young woman, the Fraser boy’s photograph is on the dresser, next to an image of her three sheepdogs when she worked the hills – Laddie, Lassie and Fly. The tin of family circle biscuits would have been from her neighbour Tom Wickham, who always gave these as Christmas presents. Towards the back of the room, a chest of drawers has a green plastic bag of messages (term for shopping).

3. Jenny’s Room, 1987 watercolour, 54.5 x 78 cm signed lower left exhibited Thackeray Gallery, London, c.1987 provenance Private collection, Warwickshire

A Shepherd’s Life, Paintings of Jenny Armstrong by Julie Lawson and Mary Taubman, National Galleries of Scotland, 2000

Victoria Crowe OBE, DHC, FRSE, MA (RCA) RSA, RSW (b.1945)

Victoria Crowe OBE, DHC, FRSE, MA (RCA) RSA, RSW (b.1945)

Lightening Shadows belongs to a series of paintings Victoria Crowe painted after her neighbour and shepherd, Jenny Armstrong had died; painted from memory and revealing a deeper understanding of an ordinary life made extraordinary. The artist has arranged the mantel with a series of familiar objects including Jenny’s Victorian blue and white water jug which is filled with lunaria. The centre photograph is of the Fraser boy; a young man holding a dog – in the 1950s and 60s, he had lived with his mother and father at the Gate Cottage in Kittleyknowe. The internal wallpaper has faded and is in sharp contrast to the view which can be seen from the window on the right; two sheep graze, whilst the winter trees on the horizon reveal the Pentland Hills beyond. There is light on the landscape and the life cycle marches on.

4. Lightening Shadows, c.1986 oil on board, 40.5 x 51 cm signed lower right, titled on verso exhibited

Thackeray Gallery, London, 1989 provenance

Private collection, London; Private collection, Worcestershire

Victoria Crowe OBE, DHC, FRSE, MA (RCA) RSA, RSW (b.1945)

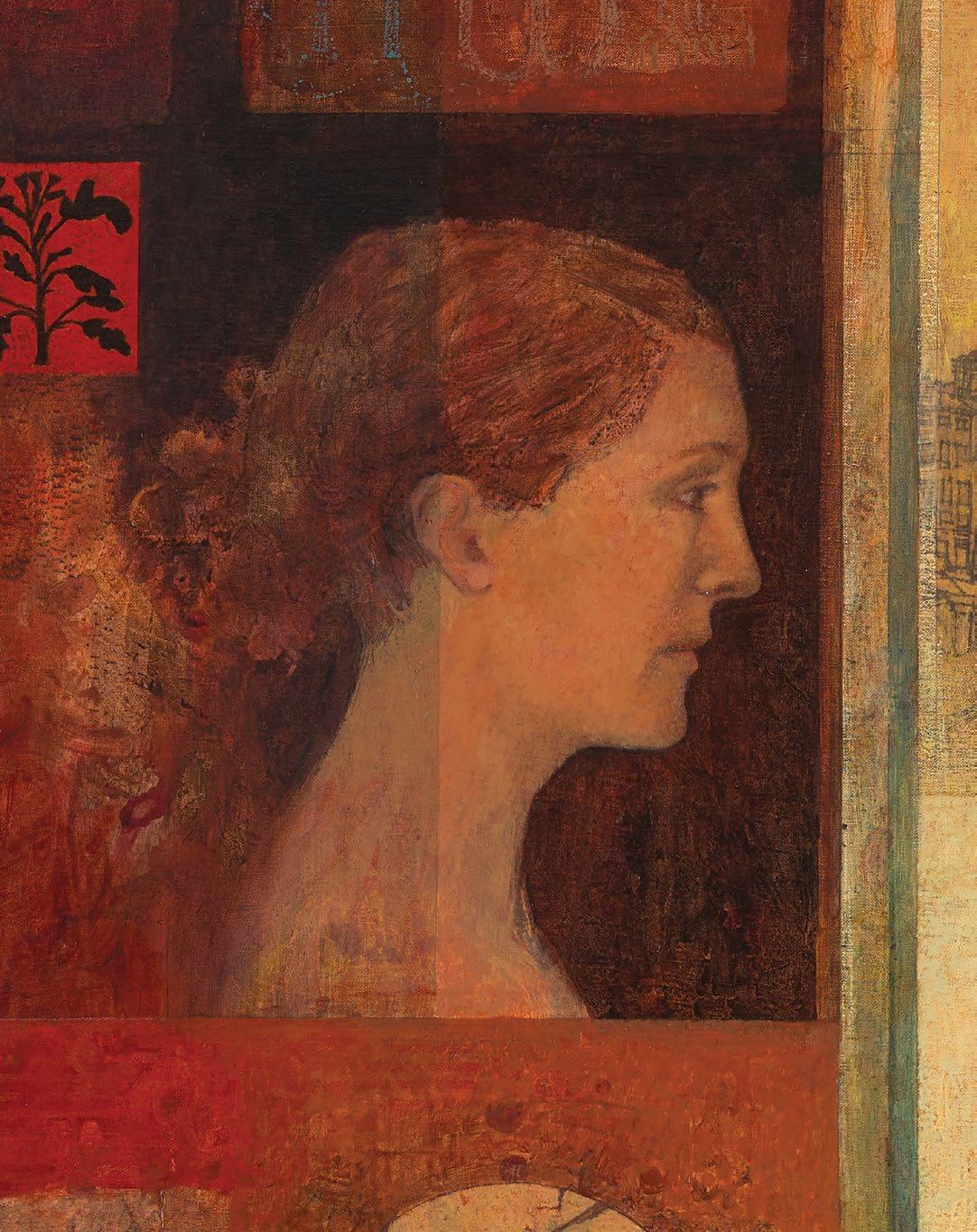

‘During my sabbatical term in 1992, I made my first study trip to Italy. I was there during the Easter period and noted the huge contrasts between the solemnity of Holy Week and the explosion of celebration on Easter Sunday. In Florence on Good Friday, the Cappella dei Principi, an octagonal, marbled mausoleum, was full of unlit white candles and white flowers of hydrangea and orange blossom against the dark marble walls. In contrast, Siena was full of people celebrating resurrection, waving olive and palm branches, while members of the Contrade, some on horseback and all in medieval costume with striped and quartered

leggings, gold brocade… proclaimed Easter. The idea of a vigil, a period of contemplation and focus, between these two states of mind, despair and waiting, to joy, is common in Christian celebrations at Christmas and Easter. Venice on the other hand, is a great place for survivors. That medieval city which had survived among all these ravages… the creep of lichen, the flaking of paint, the fading of colour, the rubbing away of gold… graffiti adds its message to all this too… The process of change made visible.’

Crowe, 2022 Victoria Victoria Crowe in Venice, 2014. Photograph by Andy PhilipsonKnown and Imagined World contains a portrait of the artist’s daughter, Gemma Gray. This is contained within several other portraits: Venice, plant studies and details from the medieval city, with the overall composition seen as a marriage portrait. This is a rich, complex painting which appears serene, outward looking, and joyful.

Victoria Crowe OBE, DHC, FRSE, MA (RCA) RSA, RSW (b.1945)

5. Known and Imagined World, 2012 oil on linen, 101.6 x 114.2 cm signed lower right exhibited

Victoria Crowe, Ti Sorprendo, The Scottish Gallery, December 2012; Victoria Crowe, 50 Years of Painting, City Art Centre, Edinburgh, 2020 provenance Private collection, London illustrated

Duncan Macmillan, Victoria Crowe, Antique Collectors Club, 2012, p.177

(1934–2002)

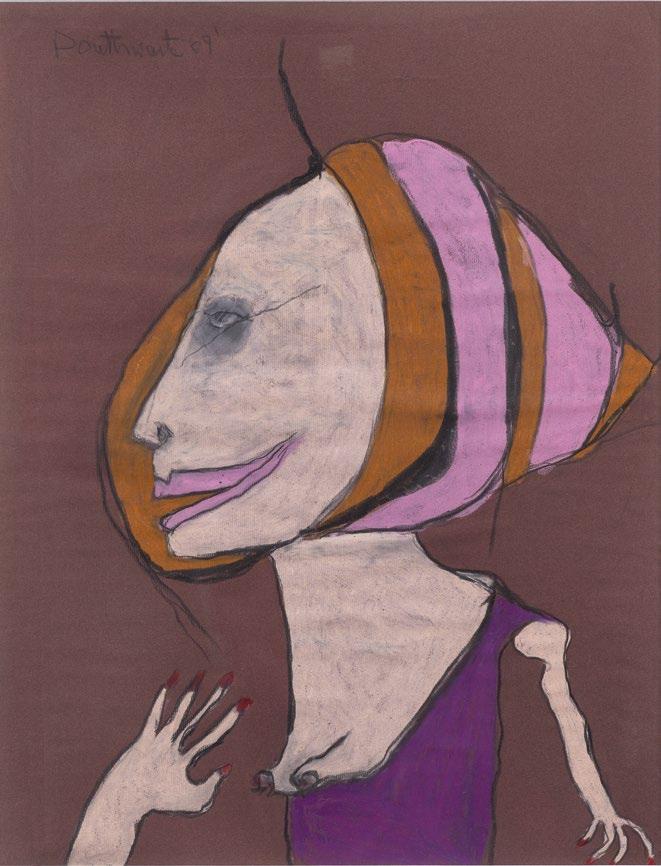

In 1969, Pat Douthwaite was one of ten Scottish artists exhibited in New Tendencies in Scottish Art at the Richard Demarco Gallery in Edinburgh. For its exhibition catalogue he wrote: ‘In Patricia Douthwaite Scotland has an artist who has the capacity to shock and horrify in the long Northern European tradition which goes back to Grosz and the German Expressionists. Thankfully, her black humour is mingled with compassion.’ Demarco admired her shocking subject matter and emotion, and what he believed to be a type of expressionism never before seen in Scottish painting. Female Figure is a bold and dramatic example: the female with her serpentine smile appears grotesque and imperfect, which makes her all the more human. Pat Douthwaite, c.1971.

Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002)

6. Female Figure, 1969 pastel on paper, 64 x 49 cm signed and dated upper left provenance Private collection, Dundee

PPSSA (b.1958)

Kate Downie is an artist whose residencies and adventurous spirit have taken her all over the world. This large oil of the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge is the result of study and experimentation in the Chinese ink painting tradition. The contrast of the urban and the rural is a theme which runs throughout her work. Here, the structural complexity of a remarkable feat of engineering is conveyed with restraint of gesture and without over-complication, while passing cargo boats and traditional bamboo net-fishing structures on the bank are painted with single-motion calligraphic lines. She paints the fog over the further aspect of the bridge, pulling it coherently into the horizon line, to convey the significant distance of the river with a calm, atmospheric quality.

Kate Downie RSA, PPSSA (b.1958)

7. The Yangtze River Bridge, 2013 oil on canvas, 110 x 200 cm signed lower right

provenance

Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh; Private collection, Edinburgh

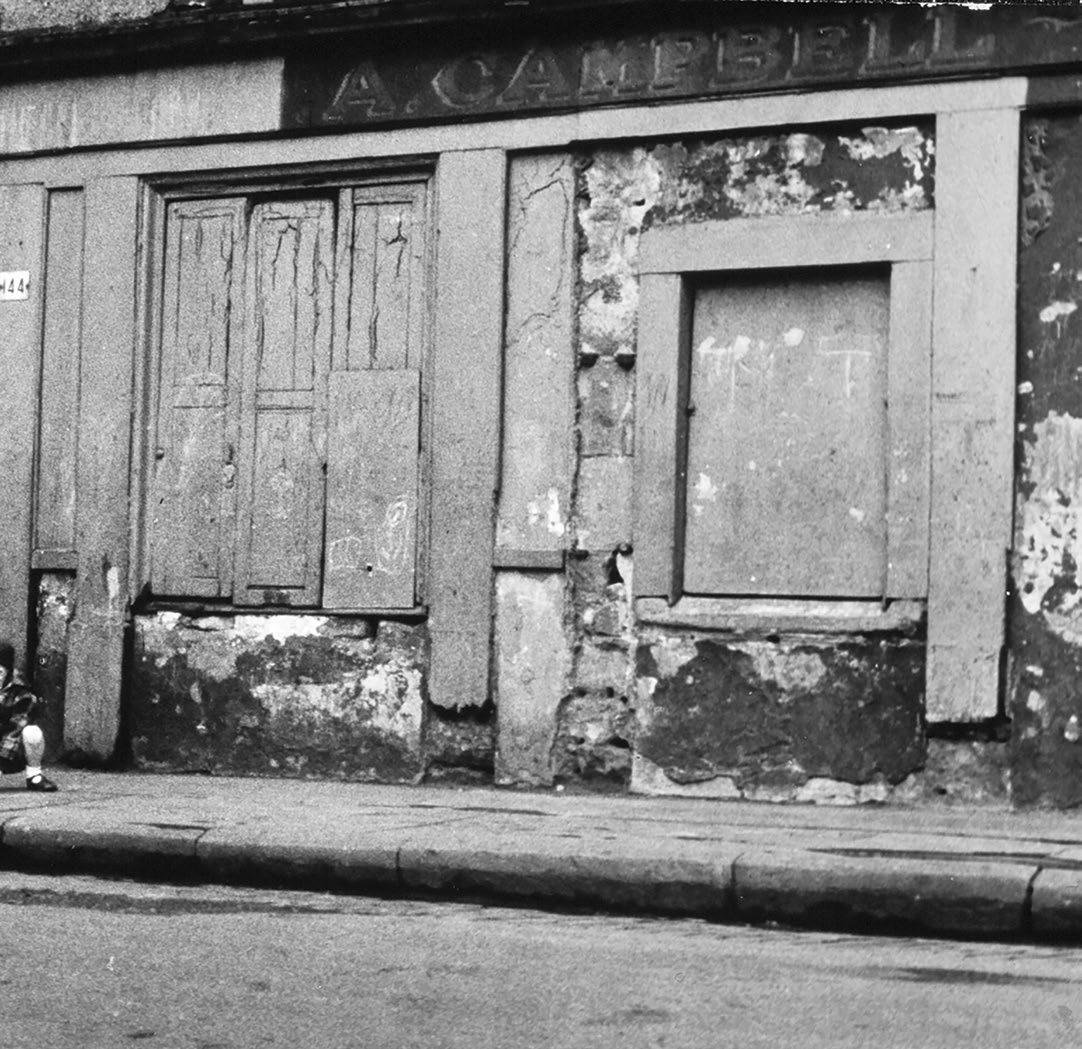

There is an enduring fascination for Joan Eardley far beyond her unconventional life and early death at the age of forty-two. In her short career we marvel at her energy and the scale of what she achieved; Joan Eardley was an unrelenting, driven talent who painted as if she was on a mission. Born in 1921 in Sussex, Joan Eardley’s family moved to Scotland in 1939 and a year later she joined the Glasgow School of Art. She found subjects in the shipyards of Clydebank and Townhead, at first the run-down tenements and buildings and later the children and street life around the Maternity Hospital on Rottenrow where the character of the people and the place became the vital subject of her work. Her art education was finished with scholarship visits to Paris and the cities of Renaissance Italy and back in Scotland she ventured with her art school friends to Arran and back to the south of France. However, by the fifties, Joan Eardley divided her life between her studio in Townhead and the fishing village of Catterline, a place she had discovered in the Northeast of Scotland after a visit to recuperate from illness after her solo exhibition at the Gaumont Cinema gallery in Aberdeen. Eardley felt at ease in these two contrasting localities and over the succeeding decade, as if by accident, she created an epic vision of the world from no more than two streets and one small fishing hamlet. The slums of Townhead are no more, the harsh realities memorialised by the honesty of her vision, the spirit of the people invested in its children captured, enduring like no other example in the history of art. Catterline remains unchanged, and the village is inevitably a place of pilgrimage for the thousands who admire the artist’s deep-felt engagement with nature on the Kincardineshire coast.

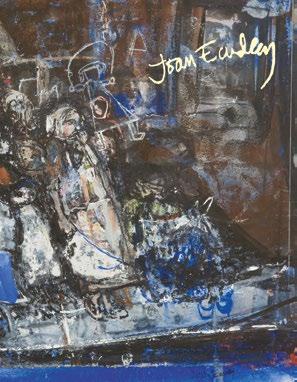

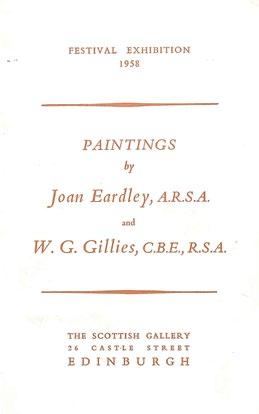

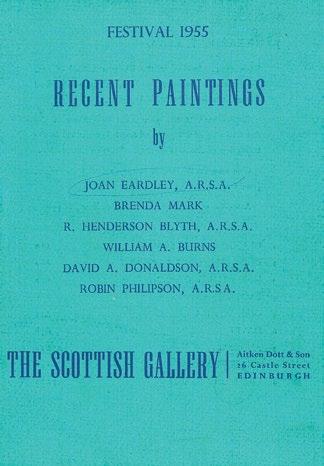

Joan Eardley was a regular gallery exhibitor from the early 1950s under the care of our former Director William Macaulay, and The Gallery remains strongly associated with the artist since her passing, particularly in the last 15 years. If you look carefully at our archive images on the right, note that Sir William Gillies, Principal of Edinburgh College of Art, who would become President of the Royal Scottish Academy, held a joint Festival exhibition at The Gallery. This exhibition signalled to the establishment that Joan Eardley was an equal amongst artists. In 2007, the National Galleries of Scotland mounted the first major Joan Eardley exhibition in 20 years; her work filled the palatial rooms of the Royal Scottish Academy building. It was a remarkable, seminal exhibition which brought the full force of her talent back into the public arena and interest in the artist and her work has grown ever since. We also held a Joan Eardley exhibition in 2007 which took five years of planning and resulted in one of our most successful exhibitions. In 2013, we marked the 50th anniversary of Joan Eardley’s death coinciding with the publication of a new monograph by Christopher Andreae. Last year was the artist’s centenary and for this we gathered over forty works, including a specially commissioned tapestry created by Dovecot Studios and a lavish publication. Despite pandemic restrictions, we welcomed hundreds of visitors who patiently queued every day to see Joan Eardley’s work, such is the enduring appeal for this restless talent.

Opposite: The Scottish Gallery Joan Eardley publications and archive

Christina Jansen

8. Two Chums, c.1954–56 pastel on paper, 21.5 x 13.5 cm exhibited

Christmas Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1966, cat. 8 provenance

The Artist’s estate inventory no.ED642; Private collection, Edinburgh illustrated

Christopher Andreae, Joan Eardley, Lund Humphries, 2013, p.49

Joan Eardley RSA (1921–1963)

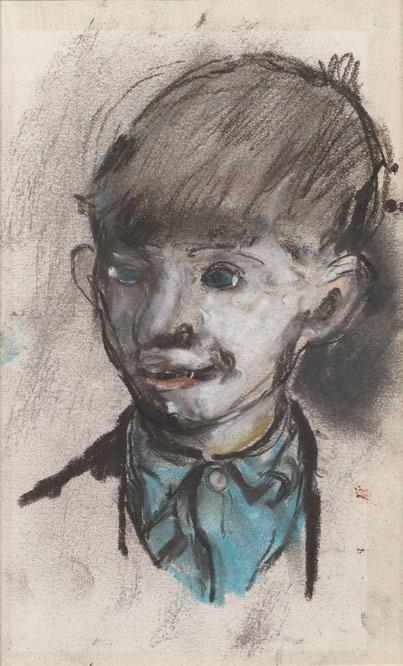

9. Boy with Blue Eyes, c.1949–56 pastel on paper, 21.5 x 13.5 cm provenance

The Artist’s estate inventory no.ED649; The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh; Private collection, Edinburgh illustrated

Christopher Andreae, Joan Eardley, Lund Humphries, 2013, p.127

From the moment of her arrival with her mother and sister in Glasgow in 1940, escaping the Blitz and the shadow of Captain William Eardley’s death, Joan Eardley had somewhere to belong. From January she was enrolled at the Glasgow School of Art. The Mac had looked after her well, awarding her its Diploma, post-Dip studies and a travelling scholarship to Italy and France in 1947–8; on her return the drawings and paintings are exhibited at the art school. By then already a professional member of the SSA she was established in her tenement studio in Cochrane Street, on the edge of the Merchant City, where she began to encounter and draw the street children. The next year she accompanied her friend Dorothy Steel to Gourock and Port Glasgow and made her first significant body of Glasgow painting and drawings. Port Glasgow had escaped the bombing raids which had devastated Greenock and Clydebank in the Spring of 1941 and Eardley was inspired by the structures of the shipyards to make industrial landscapes. But for Eardley a place is not summed up by its architecture or commerce: it is the people that matter and give colour and character to a place. The distinctive Port Glasgow tenement rows above the river

and yards look immediately forward to her great Glasgow subject, Townhead. Here the curving row is topped with a jumble of chimney stacks above a façade festooned with washing hung out to dry. As the shipyards closed demolition preceded regeneration, the poignant story repeated in most Scottish cities as transport infrastructure and high rise replaced the tenements which contained the communities.

Eardley’s eye is unsentimental and unsparing, and the accumulation of imagery derived from direct, participant observation forms a remarkable record and a homage to a lost way of life. Her many drawings of children have a hook, an element of instinctive observation which lend authenticity and the power to move the viewer. In The Two Chums (cat. 8) it is the conjunction of the boys, the elder with his arm around the smaller child, his eyes look across, as if protective. In Boy with Blue Eyes (cat. 9), it is the eyes, the blue repeated in the shirt, buttoned up, rumpled collar; his tie perhaps whipped off in the joy of the end of the school day.

Joan Eardley RSA (1921–1963)

10. Port Glasgow, c.1950–53 pen, Indian ink and watercolour, 17 x 48 cm exhibited

Joan Eardley Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1966 provenance

The Artist’s estate inventory no.ED1375; Private collection, Edinburgh

Much has been written about Joan Eardley and the Samsons, a Townhead family of perhaps 12 kids, who drifted in and out of her studio and became the subject for which she is most celebrated. This interior depicts Andrew, the eldest and first of the siblings she painted. It is dated as early as 1949 by Eardley’s biographer Christopher Andreae, but relates closely to her portrait of Angus Neil (page 112 of Joan Eardley, Lund Humphries, 2013). Neil sits passive, eyes downcast, cigarette burning in his fingers, but the boy looks about, posed with elbow on the table, hand tucked into his bomber jacket; he won’t be there for much longer.

On the reverse, is an unfinished painting of Townhead with a group of children in the foreground. The view is of the back of the close – an area directly behind the tenement buildings where the drying greens (for hanging washing) were situated; a playground of sorts. It was very common for artists to reverse a picture if they favoured another subject and didn’t want to waste the canvas. Seated Figure with Table is therefore a portrait with interior and exterior combined, which together reflects a period of post-war Britain.

Reverse side of Seated Figure with Table

11. Seated Figure with Table, c.1949–53 oil on canvas, 51 x 63.5 cm painting verso

provenance Private collection, Edinburgh illustrated

Christopher Andreae, Joan Eardley, Lund Humphries, 2013, p.99

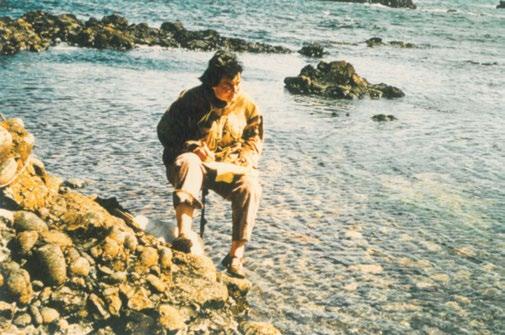

Catterline is a coastal fishing village in Kincardineshire, in the Northeast of Scotland, where Joan Eardley lived and worked from the early 1950s. A few weeks before her 29th birthday in 1950, Joan Eardley had a solo exhibition at the Gaumont Cinema in Aberdeen. She stayed with the Soper family in Stonehaven south of Aberdeen and while with them visited Catterline, a further seven miles south. Eardley’s first paintings of Catterline date from 1950 and for the next 10 years she increasingly visited and stayed in the village first through Annette Stephen (née Soper) offering free use of a property, renting her own cottage in 1954 and then buying one in 1959. At the time the village had a population of around 80 people and was unusual in that it had both fishermen and farmworkers as residents. The fishermen tended to stay in the older cottages looking down over the bay and its harbour. Eardley’s paintings reflect this rather unusual dual nature of the village. There are paintings of land and sea. These paintings do not ignore the human activity in either arena in that the harbour and boats frequently appear in the coastal paintings and the marks of human beings appear in the landscapes, but unlike the painter’s Glasgow paintings, which she continued to paint, people are never the focus. This absence of people does not reflect a lack of engagement with the community she chose to live in. Eardley was welcomed and accepted in Catterline and in turn felt a part of the village. In cavalry twill trousers and warm dark sweaters, her hair cut like Sybil Thorndike playing Joan of Arc, she was a familiar sight working outside in all weather.

‘…when I’m painting in the Northeast, I hardly ever move out of the village, I hardly ever move from one spot. I find the more I know the place or the more I know the particular spot, the more I find to paint in that particular spot. I do feel the more you know something, the more you can get out of it – the more it gives to you. I don’t think I am painting what I feel about scenery –but certainly not ‘scenery’ with a name. The Northeast – it’s just a vast waste and vast seas, vast areas of cliff – you’ve just got to paint it. I very often find I will take my paints to a certain place which has moved me and I’ll begin to paint there and I find by perhaps the end of the summer I haven’t moved from that place. My paints are still there. I’ve worn a kind of mark in the ground – no grass left! And I just leave my paints there overnight and eventually it seems to have built up this other table and generally a studio seems to have arrived outside and that seems to be how I work. Once I’ve started in a place, I don’t find I want to move, because I’m trying to do something and you’re never really satisfied with what you’re doing, so you keep on trying and the more you try the more you think of new ways of doing this particular subject and so you just go on and on.’

Joan Eardley, BBC interview, January 1963Joan Eardley painting the sea in Catterline, 1960.

Walker

Photograph by Audrey John Morrison

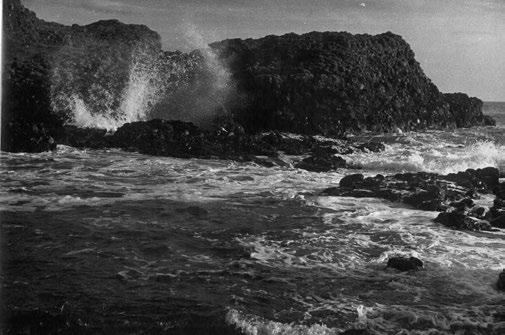

The late William Feaver described Eardley’s seascapes as spuming escarpments. We can recognise these in Winter Sea II, breakers rolling into the tight bay, dissipating their energy on its adamantine rock features, casting their spray onto the foreshore where the artist has planted her board to the east of Catterline’ s pier. It is winter and a gale has blown up, the dark rimmed sun already low in the west, still bright in the broken clouds. The gestural stroke of red indicates a beached boat, likely local fisherman Alec Craigie’s Fear Not, which has been pulled high above the churning surf. Eardley provides structure for her drama of sea and storm, the familiar features of the black rocky coast framing the crashing waves, her composition opening to the south with the rock finger sitting below the dark eye of the storm, described with sweeping brushstrokes.

Joan Eardley RSA (1921–1963)

12. Winter Sea II, c.1959–62 oil on board, 100 x 111 cm exhibited Sea and Shore, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1989, cat. 106 provenance Private collection, Dublin; Private collection, Edinburgh illustrated Christopher Andreae, Joan Eardley, Lund Humphries, 2013, p.159

Top: The Skipper’s bothy and nets, Catterline, c.1955.

Middle: Joan Eardley at Catterline, c.1960.

Bottom: Catterline, c.1958. A fishing and farming community.

Photographs by Audrey Walker

Top: The Watch House, Catterline, c.1961.

Middle: Waves breaking at Catterline, c.1955.

Bottom: Joan Eardley, October 1958, Catterline.

Photographs by Audrey Walker

Eardley will have made her way down to the water’s edge in the late afternoon, picking her way over the rocks and creels in the fading winter light. Her viewpoint is to the east of the pier close to the small salmon bothy, looking back towards the long sweep of cliffs, leading towards the headland and the silhouette of Todhead Lighthouse. The distinctive geographical features of Catterline’s rocky bay frame her scene, with the boulder like structures of ‘Kale Tap’ and ‘Dunning Woof’ lying in shadow against the backdrop of dark hill. The tide is high, and Eardley paints from the edge of the surf with the North Sea swell throwing

foam over submerged rocks. The subject is the intense sunset, piercing the brooding sky like a line of fire which illuminates the shallow water in a pink and violet light. This painting was gifted by the artist to her friend and Catterline resident Annette Stephen (née Soper), who first introduced Eardley to the area in 1951, later marrying local fisherman ‘Big’ Jim Stephen. Painted between 1960 and 1963 and relating closely to its sister work in the collection of the City Art Centre, Sunset over Catterline shows Eardley at the height of her expressive powers, the full potential of her visual language realised to harness the immediacy of her experience.

Joan Eardley RSA (1921–1963)

13. Sunset over Catterline, 1960–63 oil on board, 72 x 112 cm exhibited

Joan Eardley, Pastel, Drawings and Paintings, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1992, cat. 13 provenance

Annette Stephen, Catterline; Eduardo Alessandro Studios, Dundee; Private collection, Newcastle

RSA, RSW, RWA, RGI (1906–1994)

Gamrie is an area of Aberdeenshire, in the northeast of Scotland, encompassing spectacular country landscapes and the picturesque coastal villages of Gardenstown and Crovie. Built into the old red sandstone cliffs, the villages have a quaint atmosphere. From the harbour and beaches, you can look out over the Moray Firth and perhaps catch a glimpse of the dolphins that often swim in the bay or experience one of the stunning sunsets.

Ian Fleming was born and schooled in Glasgow and taught at the Glasgow School of Art from 1931 until 1947. He was an encouraging teacher who quietly nurtured the careers of many painters, including the Roberts, Colquhoun and MacBryde, and Joan Eardley. He moved to Aberdeen (by way of Hospitalfield House in Arbroath) and eventually became Head of Painting at Gray’s School of Art. An early love of etching was sustained and in 1987 he showed a series of etchings at The Scottish Gallery. In painting, he was an influence on many, including William Burns, Robert Henderson Blyth and Joan Eardley.

Ian Fleming, second from right smoking his pipe, with Gray’s School of Art staff and students, Aberdeen, 1971. Demarco Archive

Ian Fleming RSA, RSW, RWA, RGI (1906–1994)

14. Gamrie, c.1970 pen and wash drawing on paper, 37 x 45 cm signed lower left; inscribed with title and signed on label verso

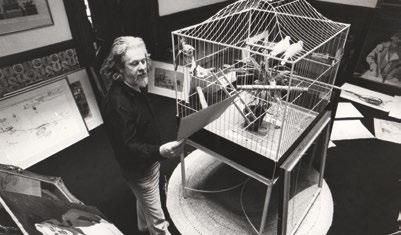

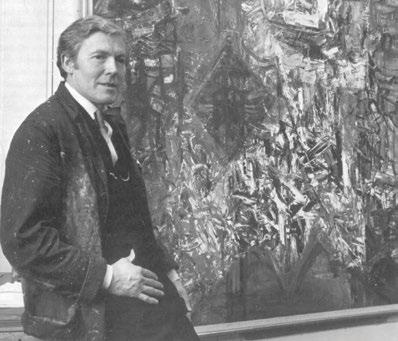

I have strong memories of visiting the home and studio of Sandy Goudie in Arnewood House, Glasgow surrounded by the extraordinary profusion of his creativity, lines, couplets, stanzas and epic poems of imagery making up a grand, operatic production. At his beautiful Victorian home and studio in Glasgow, there was a great atrium which held a large, suspended white bird cage with doves; all around were vitrines of modelled clay, paintings, frames, monumental props arrayed around and above on the gallery level more canvasses; stretched, primed, started, paused. No project was too grand: a commission for all the artwork and designs for the interiors of a giant ship from Brittany Ferries; Strauss’s Salome or Burns’ Tam O’Shanter. The artist thought big but honed his aesthetic to the last flourish, for a highlight on a ceramic jug or vital pentimento in a life drawing; attention to detail was obsessive and his art was an extension of his personality. From the declaration explicit in his early portraits that says: ‘I have arrived,’ to the touching depiction of the children, to his love letter in paint to his Bretonne wife Maïnée, to accomplished easel paintings and designs and sketches fizzing with creative energy, the personality of the painter is not hard to find and forms a vital, recently overlooked contribution to post-war Scottish art.

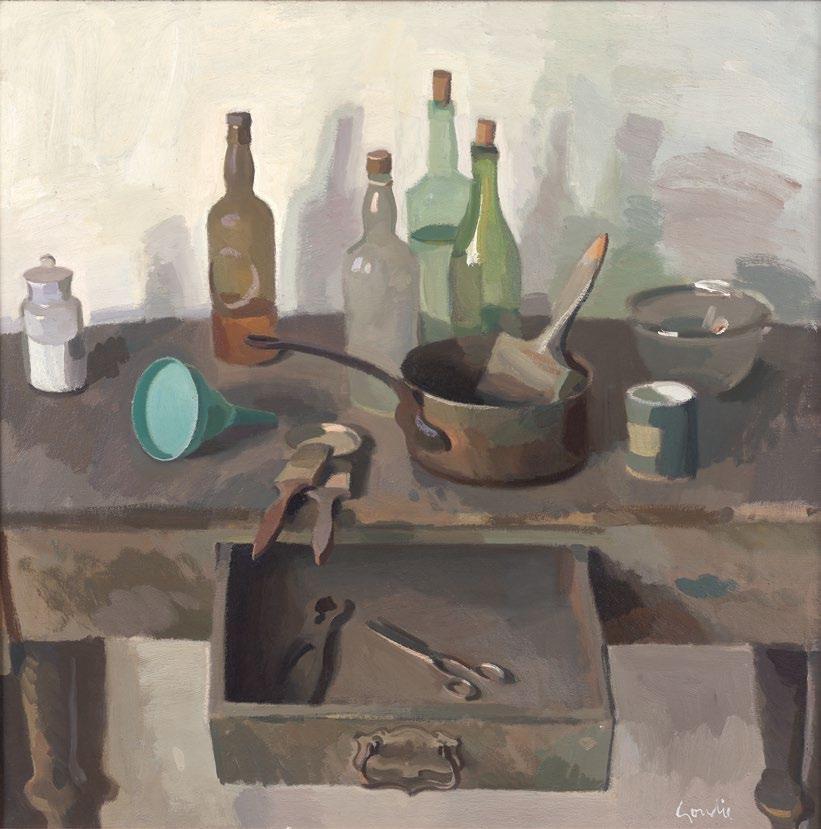

Guy Peploe15. Still Life with Bottles and Open Drawer, 1982–83 oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm signed lower right

Alexander Goudie preparing an exhibition, c.1983.

This still life would have been painted in Alexander Goudie’s studio in our family home in Glasgow. My father’s elaborate and richly painted still lifes were extremely sought after. In a series of paintings in the mid 1980s he often took inspiration from the objects that surrounded him in his studio – the tools of his trade. They are, in themselves, very humble items; worn brushes, a jar of white pigment, an old copper saucepan which he would use to prepare size, when priming his canvasses. But in the way that Alexander Goudie painted them, each object is afforded an extraordinary, sculptural presence. The handling of the paint displays a mastery of confident and economical brushwork. Just enough detail is given to summon up each object and the palette of colours deployed is both subtle and precisely modulated. The overall effect is an image which, for me, resembles a kind of painter’s altar – a profound and powerful tribute to the artist’s craft.

Lachlan Goudie Alexander Goudie RP, RGI (1933–2004)

William Johnstone was the Borders farmer turned painter, an artist who made a significant career ‘down south’, becoming one of the great art educators of the post war era. He was Principal at Camberwell School of Art and at Central St Martins, London, before retiring in the late 1950s. Border Landscape is a sparse and automatic painting in watercolour and brush and is unusually representative. The Borders, the people and places were always at the forefront of his mind, however far his career took him and this painting will have marked a return to his homeland which he entirely inhabited, emotionally and intellectually.

William Johnstone OBE (1897–1981)

16. Border Landscape, 1960 watercolour, brush and ink on paper, 17 x 24 cm signed and dated lower right

provenance

The Artist’s family; Duncan Miller Fine Arts, London

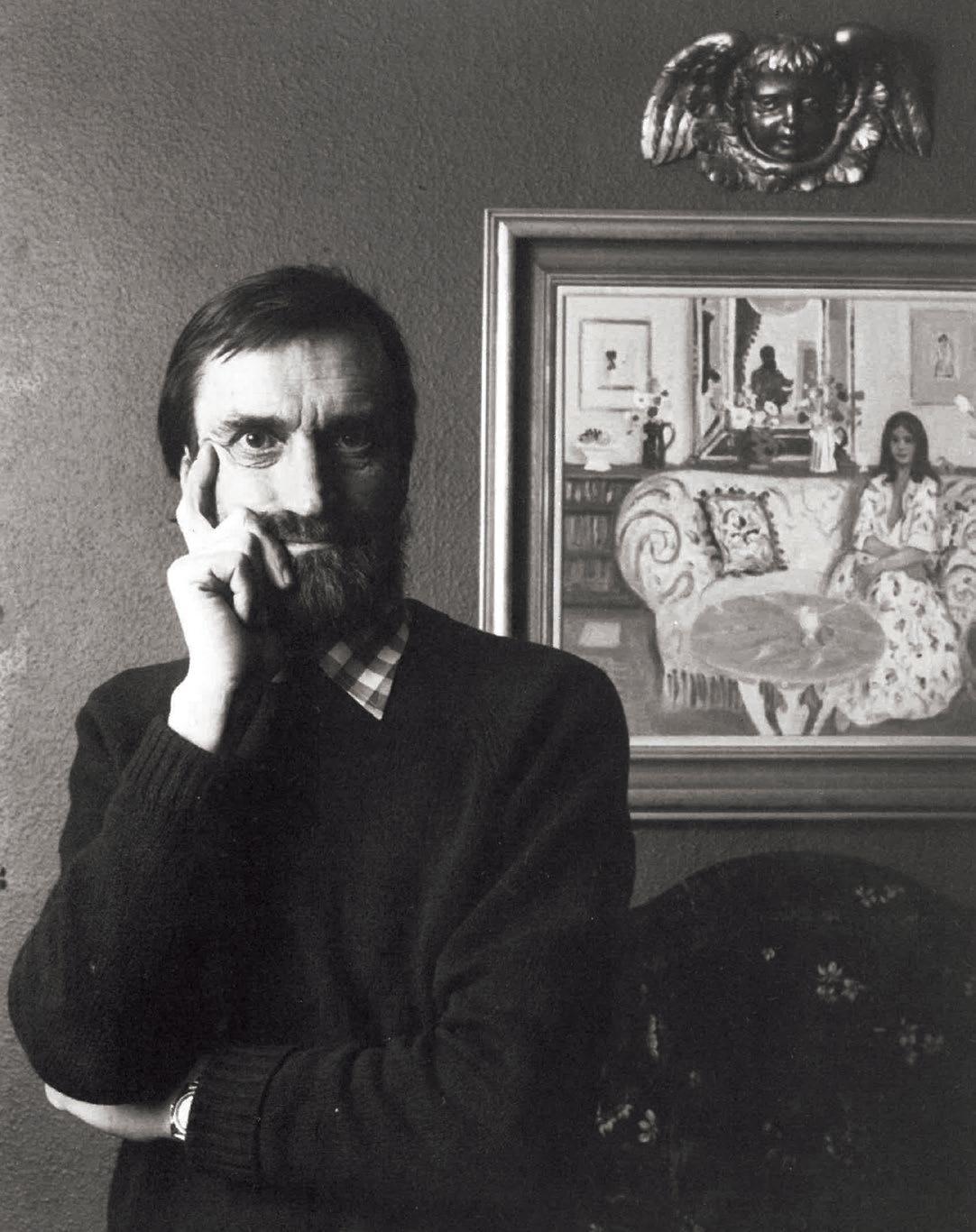

McClure was one of a group of highly regarded young painters that included James Cumming, William Baillie, John Houston, Elizabeth Blackadder and David Michie all of whom graduated from Edinburgh College of Art in the early 1950s having benefited in their formative years from the examples of a remarkable concentration of talent in the capital, both on the Art College staff and in the annual exhibitions of the RSA, RSW, SSA or SSWA. In addition, The Scottish Gallery were regularly showing established artists such as Anne Redpath, William Gillies, William MacTaggart, as well as younger artists such as Joan Eardley and Robin Philipson. McClure and many of his Edinburgh College peers soon joined them.

McClure had his first one-man show with The Scottish Gallery in 1957 and the succeeding decade saw regular exhibitions of his work. He was included in the important surveys of contemporary Scottish art which began to define The Edinburgh School throughout the 1960s and culminated in his Edinburgh Festival show at The Gallery in 1969. But he was, even by 1957 (after a year painting in Florence and Sicily) in Dundee, alongside his great friend

Alberto Morrocco, applying the rigour and inspiration that made Duncan of Jordanstone a bastion of painting. His friend George Mackie writing for the 1969 catalogue saw him working in a continental tradition (as well as a ‘west coast Scot living on the east coast whose blood is part Welsh and wholly Celt’) and exemplary of the artist as antidote to the dour Scot. ‘The morose characteristics by which we recognise ourselves… have no place in our painting which is traditionally gay and life-enhancing.’ Towards the end of his exhibiting life, Teddy Gage reviewing his show of 1994, celebrates his best qualities in the tradition of Gillies, Redpath and Maxwell but in particular admires the qualities of his recent Sutherland paintings: ‘the bays and inlets where translucent seas flood over white shores.’ We can see McClure today as a distinctive figure that made a vital contribution in the mainstream of Scottish painting, as an individual with great gifts, intellect and curiosity about nature, people and ideas.

Robin McClure (1955–2022)

Former Director of The Scottish Gallery 1988–2011

Infantas, Icons, Kings, and Bishops on horseback feature in another strong but narratively enigmatic series of works from this period. While undoubtedly based in part on his own experiences of religious processions and services and works seen in the churches he visited whilst in Spain, Florence and Sicily, church interiors also feature in the work of Anne Redpath (David and Joyce McClure were very close to Anne). Regal and religious figures also appear in some of Robin Philipson’s Roualtinspired work from the later 1950s.

Robin McClure, 2014

David McClure RSA, RSW (1926–1998)

17. Infanta, 1962 oil on canvas, 63.5 x 76 cm signed and dated lower right exhibited

Paintings by David McClure, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1962, cat. 31; David McClure – Memorial Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2000, cat. 20 provenance Private collection, Bathgate

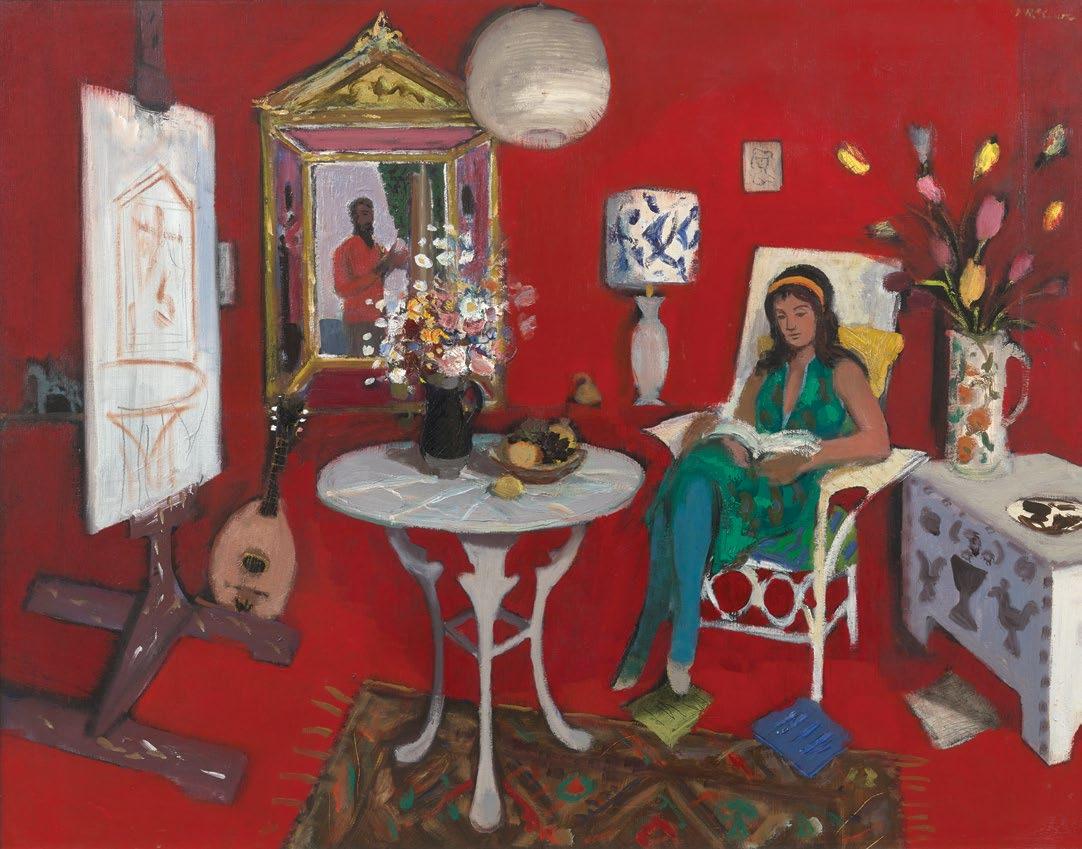

The Red Studio comes from McClure’s hugely successful 1969 Edinburgh Festival Exhibition at The Scottish Gallery in Castle Street in which there were two major themes – sensual nudes or models in an interior and still life/picture on an easel composition. The constructed settings are an imaginary combination of the artist’s studio and living room in Dundee, with the picture space defined only by the angles and perspective of furniture, rugs, a window, hung paintings or a wall-mirror all set against a single, strong flat background colour used for both wall and floor. Again, a painting on an easel usually appears, usually the one for which the

model is sitting, although not always. In The Red Studio, you are being invited into the artist’s studio with the artist reflected in the mirror as he paints the seated model. The blanket box is one painted by the artist inspired by similar furniture he saw in Norway in the impressive Museum of Folk Art. Anne Redpath of course had also painted furniture inspired in her case by similar French examples and indeed the lamp in the background here is sitting on a tea-chest she painted and which the artist owned as well as the tall vase and mandolin.

Robin McClure, 2014David McClure RSA, RSW (1926–1998)

18. The Red Studio, c.1969 oil on canvas, 86.5 x 112 cm signed upper right exhibited David McClure – Recent Paintings, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1992, cat. 10 provenance Private collection, Bathgate

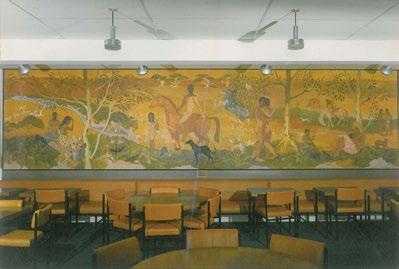

The subject of Horseman also forms the central motif of McClure’s monumental mural commissioned by Sir Anthony Wheeler for the staff common room of St Andrews University in 1975. Wheeler retained a cartoon of the whole composition which was in his collection until his death in 2013. The subject is an extensive arcadian landscape, an Eden without the serpent, in which man, woman, the birds and beasts rest and carouse, McClure’s personal response to Matisse’s Luxe, Calme, Volupte Our painting is likely to have come a few years after the mural was completed, the artist returning to his magnus opus for inspiration.

David McClure RSA, RSW (1926–1998)

19. Horseman, 1975 oil on board, 51 x 61 cm signed lower right exhibited David McClure Memorial Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2000, cat. 44 provenance Private collection, Bathgate

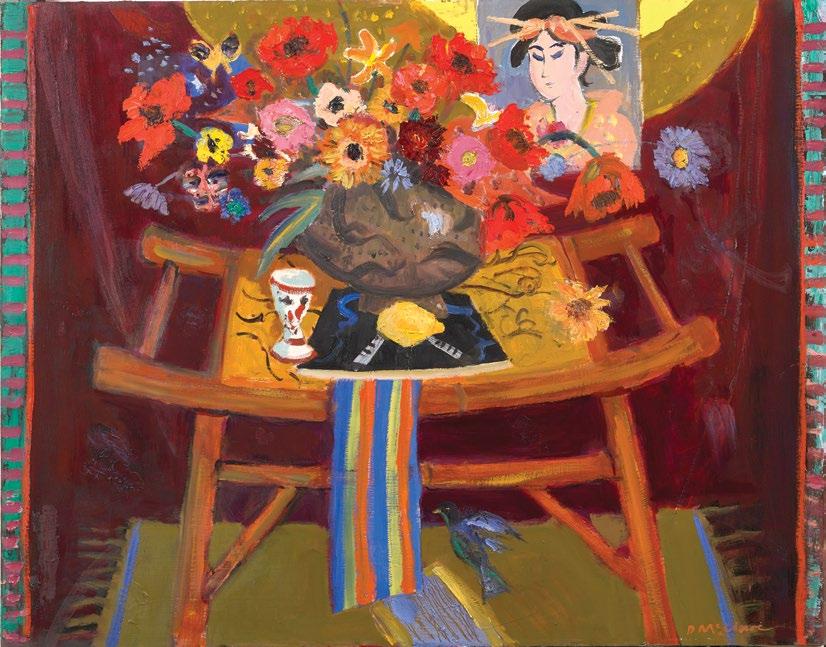

The Bamboo Stool is typical of the studio work McClure made in the seventies: a dark background, a theatrical setting for his interior still life, full of exotic and numinous objects: the Japanese print, chalice, fan and flowers.

David McClure RSA, RSW (1926–1998)

20. The Bamboo Stool, c.1978 oil on board, 71 x 91 cm signed lower right; inscribed with title verso provenance Private collection, Bathgate

Born in Loanhead, near Edinburgh, Sir William MacTaggart was the grandson of the landscape painter William McTaggart (1835–1910). He studied at Edinburgh College of Art from 1918 to 1921 at the same time as William Gillies and travelled to Paris after graduating. He was a founder member of the 1922 Group and in 1927, he joined the exclusive Society of Eight whose members included Colourists FCB Cadell and SJ Peploe and began, ahead of his contemporaries a successful exhibition career at The Scottish Gallery from 1929. A sumptuous painter in oils, he was instinctively an expressionist and romantic painter, his outlook shifting dramatically after visiting the Edvard Munch exhibition at the Scottish Society of Artists in 1931 (eventually marrying the Norwegian curator Fanny Aavatsmark) and again after studying Roualt in Paris in the 1950s. From his home and studio in Edinburgh’s Drummond Place in the New Town, some of his best-known works offer a still life, framed by a window, looking east towards Bellevue Church. MacTaggart was president of the Royal Scottish Academy from 1959–1969 and was

knighted for his services to art in 1962. From 1951, MacTaggart and his wife travelled the short distance to the Johnstounburn Hotel at Humbie for the Christmas Holidays. It became a favourite landscape and the inspiration for some of his most engaging work, including Away to the West (overleaf), which is one of the finest examples of this period.

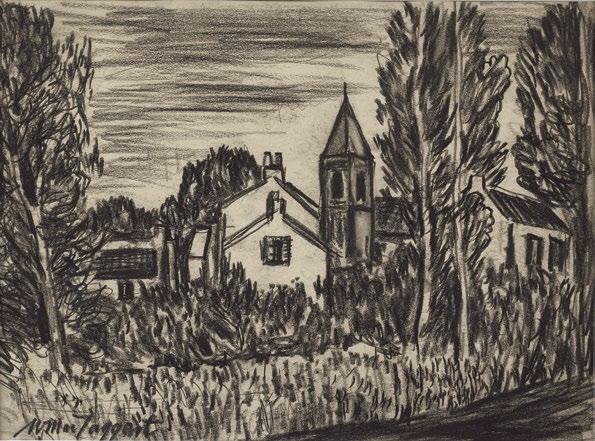

Throughout his life, MacTaggart made regular visits to France. His first trip in 1923 was enabled by a travelling scholarship and he returned frequently, finding the French landscape north of Paris and the south coast particularly rich for subject matter. This signed charcoal drawing of Orry-La-Ville will have been completed en plein air, perhaps with the intention of working up a larger version in oil on his return to the studio. An oil, Fields at Orryla-Ville, features in Kirkcaldy Art Gallery and Museum collection having been bequeathed by the great art collector JW Blyth in 1964. In 1968, MacTaggart was awarded Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur by the French government, the same year as his major retrospective exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art.

Clockwise from top: Sir William MacTaggart in his Edinburgh studio, c.1963; MacTaggart’s home at 4 Drummond Place, c.1970; MacTaggart’s drawing room at Drummond Place.

The MacTaggarts visited the town of Humbie in East Lothian regularly, particularly in winter, where he would produce charcoal sketches en plein air to later develop in the studio into finished oils. This painting, which features a low winter sun hanging over the distant Pentland Hills, conveys the mood and atmosphere of an East Lothian landscape in the gloaming, which MacTaggart, who had grown up in Loanhead, was so familiar. Like many of his later works this painting, completed with a palette knife, has a poetic quality in which MacTaggart heightens the abstract qualities of the landscape ‘to enrich the experience of the spectator… To create some kind of mood that somebody else responds to.’ This painting is one of the finest he produced and was exhibited at both major MacTaggart retrospectives at the National Galleries of Scotland in 1968 and 1998.

Sir William MacTaggart FRSE, RA, PPRSA (1903–1981)

21. Away to the West, 1963 oil on canvas, 86.5 x 111.5 cm signed and dated lower right exhibited

Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, 1963, cat. 207; 14 Scottish Painters, Commonwealth Institute, 1963; Sir William MacTaggart Retrospective, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, 1968, cat. 51; Sir William MacTaggart, National Galleries of Scotland, 1998, cat. 38

provenance

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh; Private Collection, Newcastle; Duncan Miller Fine Arts, London; Private Collection, London

22. Orry-La-Ville, c.1964 charcoal, 22.5 x 32.5 cm signed lower left exhibited

Sir William MacTaggart Centenary Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2003 provenance

Private collection, Larbert

23. Across the Bay, c.1962 oil on canvas board, 26.5 x 38 cm signed lower right exhibited

MacTaggart Exhibition, The Stone Gallery, Newcastle Upon Tyne, 1962

Sir William MacTaggart FRSE, RA, PPRSA

Sir William MacTaggart FRSE, RA, PPRSA

William

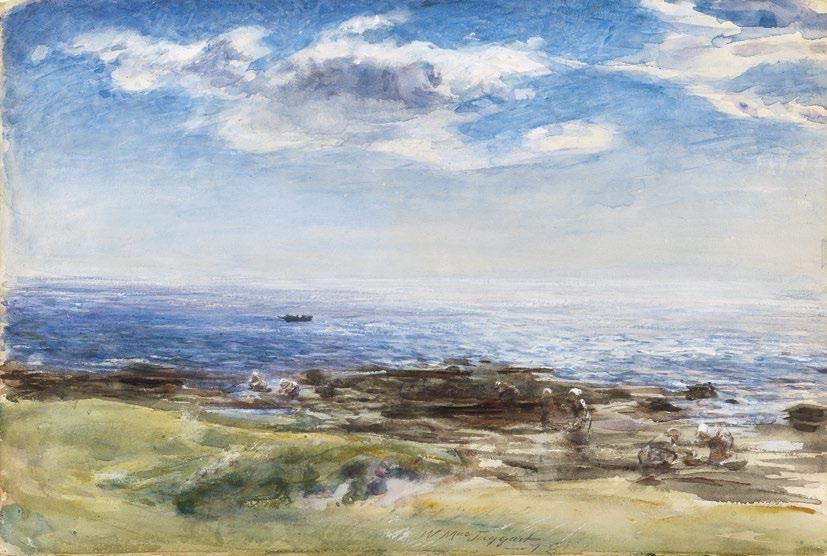

RSA, RSW (1835–1910)

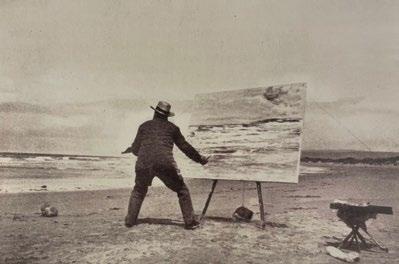

One of Scotland’s most famous landscape painters, William McTaggart’s paintings are typified by loose, energetic brushwork and a deep concern for the effects of light. The Scottish Gallery was McTaggart’s main dealer in his lifetime, selling many of his greatest works to the likes of Robert Wemyss Honeyman and Andrew Carnegie. There has been much discussion about the development of William McTaggart’s painting style in relation to Impressionism in France, but where McTaggart’s work differed from his French contemporaries is in the emotional content of the paintings; subjects such as children playing in the shallows, fishermen battling with a storm and ships leaving with emigrants to America. The figurative narrative in his paintings are observations on the communities with which he was connected in his own life and whose lives he recorded with such passion and poignancy in his paintings. He frequently worked on the east coast at Carnoustie in spring and summer and

making painting trips to his native Machrihanish during the Autumn. This scene depicts the beach of Westhaven, on the edge of Carnoustie. Painted outside, like many of his greatest works on paper, McTaggart captures the elemental qualities of light and weather on a glorious summer day.

William McTaggart RSA, RSW (1835–1910)

24. Children on the Shore, Westhaven, 1878 watercolour, 34.5 x 51 cm signed and dated lower centre

provenance

Private collection, London

William McTaggart, Machrihanish, 1898.

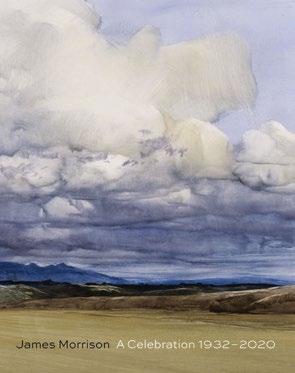

RSA, RSW (1932–2020)

‘James Morrison paints in a singular voice, as a prophet, teacher, sage, poet; it is to the land, sea and sky he asks his questions and from them he brings us answers…’

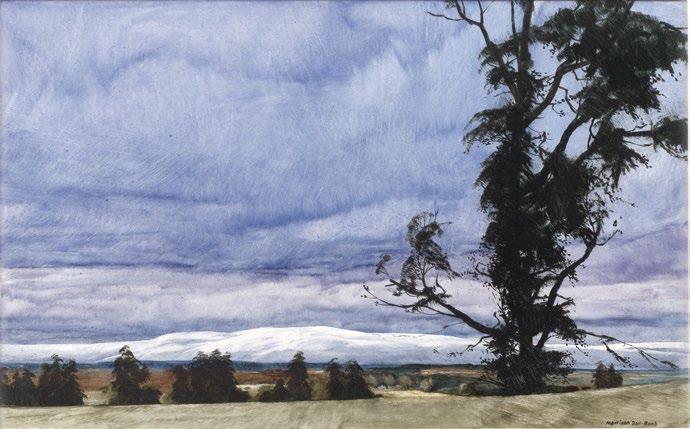

There is a moment when you pause on your walk in the country so that even the noise of your own progress cannot impinge on what you see. It is that moment that James Morrison consistently captures in his landscapes. There may be big weather rolling in, snow in the air, or brilliant blue sky, festooned high up with vapour trails. There may be a furrowed field drawing the eye to a hedgerow before a stand of trees, a windbreak for a comfortable arrangement of farm buildings. The artist understands that still, quiet moment of contemplation; it may engender awe, as when he paints at Achiltibuie in Sutherland; or a sense that all is right and has ever been so, in the rich farming landscape of Angus. His paintings are of real places and if pressed he might supply a map reference for where he set up his easel. But he will find his subjects where others might pass on. The conventions of landscape painting may be subsumed by the artist’s preferences: a strip of land, perhaps a far shore, may be crushed and over-run by a tumultuous sky which threatens to engulf the viewer. Not always for Morrison does the repoussoire tree lead the

eye to middle-ground and far horizons. While he may not invent, he will bend the landscape to his will; it will be seen through the vehicle of his technique and be subject to the editing of his intellect. Morrison tends to date his paintings, for example 24.iv.2001. ‘You mean he does them in a day!’ His practice is to work outdoors, which on a three by five-foot format is quite a difficult logistical problem. He has developed his technique to be able to work quickly, using thinned oil paint and boards prepared with a non-absorbent ground. This enables him to capture the transitory nature of his subject and also suits him temperamentally: it is not a painstaking process but one containing great force. The sky is swept in, in broad gestures; grasses or a fence are scratched in with nervous energy. The marks of the brush become the patterns of the earth, so strong is the artist’s power of suggestion. His home in Montrose and what consistently inspires him is the landscape of Angus and The Mearns, in a sense, his own back garden. As landscape lives, changes and regenerates so there in infinite variety and inspiration for the artist.

Guy PeploeJames Morrison en plein air painting in The Mearns, c.1992.

Over an eminent career, landscape painter James Morrison enjoyed a remarkable and lengthy association with The Scottish Gallery from 1959 to 2020. In June 2022, The Scottish Gallery celebrated the life and work of one of Scotland’s most-loved artists in a major retrospective show James Morrison: A Celebration 1932–2020. The exhibition, held two years after his death, presented work from the entirety of his artistic career which spanned seven decades. This coincided with the publication of John Morrison’s monograph on his father’s life and work, Land and Landscape, and a special screening of Anthony Baxter’s award-winning documentary, Eye of the Storm

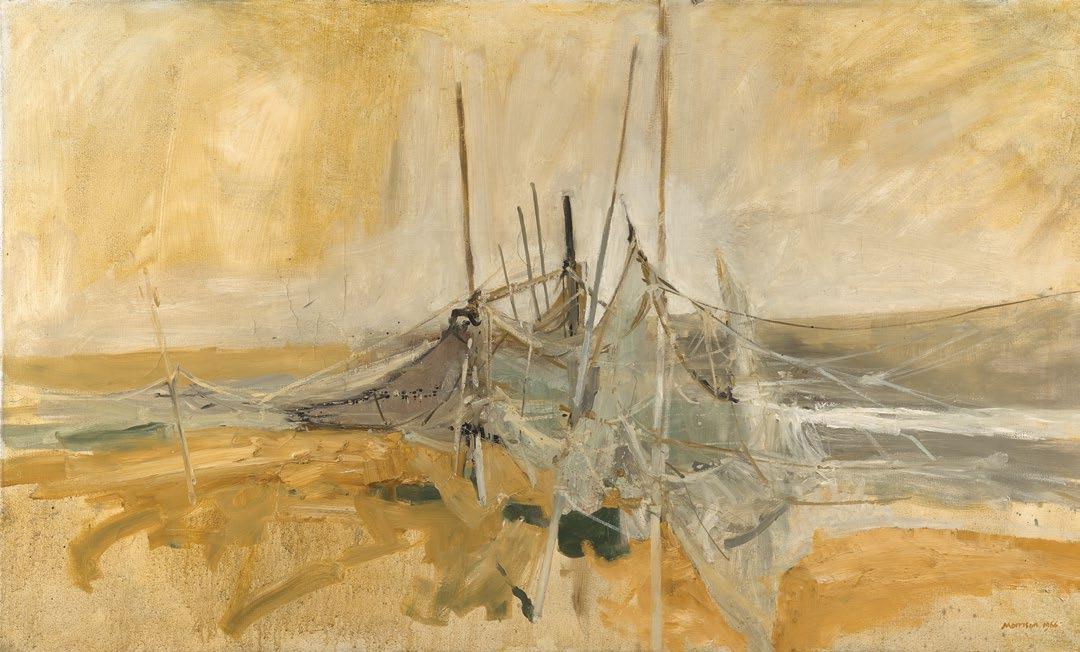

This ambitious painting, Salmon Nets was painted the year after Morrison had moved from Catterline to Montrose in 1965 and most likely depicts St Cyrus beach. Since arriving in the northeast from Glasgow, Morrison had been drawn to paint aspects of the local fishing community and boats and nets provided ample subject for the young painter, the salmon season operating between February and August of each year. In this work, the tangle of nets and receding upright posts draws the eye into the picture plane, and outward towards the sea and opaque sky beyond. It was at this moment that Morrison was perhaps most closely aligned with the work of his friend and contemporary Joan Eardley. Soon after Morrison’s move to Montrose, he began to experiment with a new visual language with a focus on the underlying formal qualities of the landscape.

James Morrison RSA, RSW (1932–2020)

25. Salmon Nets, 1966 oil on canvas, 92 x 152 cm signed and dated lower right exhibited

The Annual Exhibition, Society of Scottish Artists, Edinburgh, 1966, cat. 249

James Morrison RSA, RSW (1932–2020)

26. Old Montrose, Summer, 1980 oil on board, 75 x 105.5 cm signed lower right exhibited Thackeray Gallery, London, 1980

27. Egypt, Angus, 14.VII.1982 oil on gesso board, 55.5 x 152.5 cm signed and dated lower right

exhibited

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh provenance

Private collection, Forfar

James Morrison RSA, RSW (1932–2020)Like most of James Morrison’s Angus landscapes, the subject here is less than ten miles from the painter’s front door. Painted in winter, the fence and tractor tracks lead us down to a staccato line of winter trees, beautifully rendered, which stand stark against the wide expanse of the Montrose Basin. A low winter sun illuminates the underside of the high clouds, which build from the north and signal a change in weather.

James Morrison RSA, RSW (1932–2020)

28. Montrose Basin, 22.XII.1983 oil on board, 79 x 151 cm signed and dated lower right provenance Private collection, Angus

James Morrison RSA, RSW (1932–2020)

29. Montrose, 13.IX.1981 oil on board, 30 x 65 cm signed and dated lower right

provenance Private collection, Aberdeen

James Morrison RSA, RSW (1932–2020)

30. Strathmore, 26.I.2003 oil on board, 32 x 51 cm signed and dated lower right exhibited

Scottish Paintings & Drawings, The Scottish Gallery & Ewan Mundy Fine Art in Gallery 27, Cork Street, London, 2005 provenance Private collection, London

‘The glory of the landscape is its vastness. It rolls on and on and yet it’s so often dwarfed, completely overwhelmed, by the most immense skies, just huge great clouds that come rolling in… and dominate, completely overwhelm everything down below. It’s glorious, just glorious.’

James Morrison, 2005

James Morrison RSA, RSW (1932–2020)

31. Calm, 12.VI.2004 oil on board, 86 x 150 cm signed and dated lower right

provenance Private collection, Montrose

Born in Kirkcaldy, Lilian Neilson studied at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, Dundee (1955–60), followed by a brief period at Hospitalfield House in Arbroath, where she became friends with Joan Eardley (1921–1963). She completed a post-diploma year tutored by Hugh Crawford and Alberto Morrocco in 1960–61 and was awarded a travelling scholarship to France and Italy in 1961–62. Following this time in Europe, she joined Joan Eardley in Catterline where Neilson responded to the dramatic Northeast coastline and began painting powerful landscapes and seascapes. The artist also worked backstage with Reet Guenigault in theatres including the Traverse in Edinburgh and in England, returning to Catterline to help nurse Joan Eardley when her illness was diagnosed in 1962. Neilson bought one of the tiny fishing cottages, No 2 South Side, Catterline, with her home on one side and studio

on the other. Like Eardley, she lived a frugal life. She moved permanently to Catterline in 1986 where Neilson undertook monthly surveys of the coastline and local beaches and began studying printmaking in Dundee. Her final exhibition, Certain Days and Other Seasons, was held at the Seagate in Dundee and Aberdeen Museum & Art Gallery. Neilson, known as ‘Lil’ to her friends, pronounced this to be the end of her life’s work, prophetically as it turned out, for by August 1997, the artist was terminally ill with cancer. Sunrise Over a Seawall, Catterline, 1963 and A Beached Boat, 1964 are exceptional paintings, with the former presaging aspects of abstract expressionism in Scottish painting and the latter a love letter to Catterline. Lilian Neilson was underestimated as an artist during her lifetime and her contribution is only beginning to be fully appreciated.

Lil Neilson in her Catterline studio, c.1990. Photograph by Jenny Rutlidge

Lil Neilson has strong parallels with Joan Eardley (1921–1963), quite apart from their association, friendship, and lives in Catterline in Northeast Scotland. Sunrise Over a Seawall, Catterline and A Beached Boat speak to both the similarities in their work and the divergence. Looking at the same subjects, in particular the dark winters of dramatic sea and storm cloud, she was drawn to this wild, beautiful, forbidding place and exacted her painterly vision. Sunrise Over a Seawall, Catterline belongs to 1963 where the artist takes an imaginative, abstract approach to the subject. There is no sea wall structure in Catterline Bay: is it the sea this is the wall? Is it the harbour wall which shelters an enigmatic structure? It is a powerfully realised work that chimes with other directions in Scottish painting. Neilson was a restless searcher for well-being and truth and remains an enigmatic figure who is still to be fully appreciated as a great Scottish painter.

Lilian Neilson (1938–1998)

32. Sunrise Over a Seawall, Catterline, 1963 oil on board, 106 x 121 cm signed lower centre; inscribed with title and date on label verso

A Beached Boat is the artist’s immediate, emotional response to Joan Eardley’s passing, the previous August, painted in the winter of 1964. It is a powerful response to the wilderness they shared, where Neilson seems to inhabit the presence of her friend, to continue the engagement with a subject so dear to both.

Lilian Neilson (1938–1998)33. A Beached Boat, 1964 oil on board, 43 x 92 cm signed lower right; inscribed with title and signed on labels verso exhibited

Into the Light, Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums, 1999, cat. 11 provenance Private collection, Edinburgh

FRSE, RSW (1916–1992)

This small watercolour is a compositional study for the major triptych of the same name, now in the collection of the National Galleries of Scotland. The triptych contains a figure being consumed in flames on one panel, alongside the rich blues of a gothic rose window in another. Despite the small scale, it competes equally in intensity, with jewel like colour combined with energetic black line. The Burning III is a powerful expression of Philipson’s emotional state in the early 1960s, following the premature death of his first wife Brenda Mark in 1960.

Sir Robin Philipson PPRSA, RA, FRSE, RSW (1916–1992)

34. The Burning III, c.1963 watercolour, 17.8 x 17.8 cm signed lower right; inscribed with title and artist’s name on label verso

In November 1898, the partners of Aitken Dott & Son bought a painting A Gypsy Queen by Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935). Two years before the partners had formed The Scottish Gallery to identify the picture dealing part of the firm as distinct from the other businesses: architectural supplies, artist materials, framing, gilding and other services, determined to represent the best of contemporary Scottish painting. The picture purchase began a close relationship between The Gallery and the artist, then aged twenty-seven. A show was arranged for January 1903 which was to be a commercial success and a significant succès d’estime

As the artist developed and took his place in the vanguard of modernism, becoming Scotland’s first modernist painter, The Gallery continued its support, embracing the extraordinary changes in the direction of expressionist colour and the avant garde that Peploe represented in 1911. From the early twenties The Gallery had a joint contract, along with Alex Reid & Lefevre to buy work directly from the artist, an arrangement which allowed Peploe to remove himself from the vicissitudes of the marketplace and concentrate on work, particularly his new subject of Iona and the magnificent rose and tulip paintings of his maturity. From April 1924 both firms had a similar arrangement with George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931) and his only show with The Gallery took place in the autumn. It was a momentous year which saw the exhibition: Peintres de l’Ecosse Moderne at the Gallery Barbazanges in Paris, featuring Peploe, Fergusson, Hunter and Cadell, and a productive time for Hunter who worked in Fife and on Loch Lomond and in a Glasgow studio for the most of the next three years. From 1928 he was living mostly in the South of France, based in St Paul de Vence and from where he sent back pen and crayon drawings. FCB Cadell (1883–1937) showed first with The Gallery in 1909 and again the following year when his Venetian work was showcased. The visit, sponsored by his

friend Sir Patrick Ford, had been productive and represented (as with Peploe and Fergusson in Royan in the same year) his full engagement with a personal impressionism in which colour was used for direct expressionist purpose. He had a precocious early career, brilliant in watercolour, encouraged by his godfather Arthur Melville. In oil, again chiming with the other Colourists, his earlier work is characterised by rich medium, broad-brush marks but high in tone, unlike the more sonorous works of Peploe and Fergusson’s early Edinburgh years. Cadell held another one man show with The Gallery in 1932 but he had always been comfortable to be his own agent, using the artist-run Society of Eight for many of his exhibitions of new work and on Iona, where he went every Summer with Peploe after the Great War. J D Fergusson (1874–1961) held a oneman show with The Scottish Gallery was in 1923 which significantly included both the small-scale sculpture he had produced over the preceding few years and the Highland series of oil paintings which represent The Scottish Colourists artist’s engagement with his native landscape and culture. Twenty years before he had been one of the purchasers of work from his friend Peploe’s first exhibition at The Gallery, but in the intervening years he had looked to London and then Paris for his commercial and spiritual existence and it would only be after his second flight from the continent in the face of the World War that Scotland would take the central place in his work and thoughts. The Scottish Gallery’s history is intimately entwined with the evolution of Scottish art and the lives of the painters. In the decades after their deaths The Gallery has represented the estates, included key works in survey exhibitions, sold works into national and regional museums, fostered and expanded the reputations of the artists, stressing their significance in a British and European context.

Guy PeploeFrom left to right:

FCB Cadell, picnicking with friends, Iona, 1920s.

George Leslie Hunter, c.1910.

JD Fergusson and SJ Peploe at Paris-Plage, c.1907.

SJ Peploe in his Devon Place studio, c.1902–04.

JD Fergusson (1874–1961)

JD Fergusson (1874–1961)

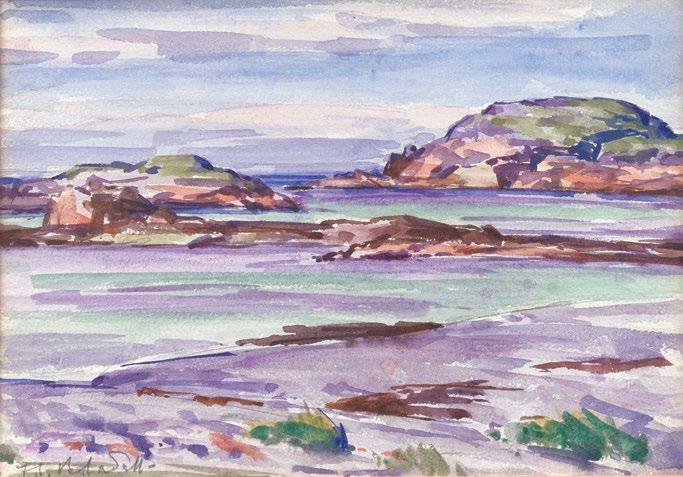

After serving in the Great War, Cadell returned to Iona with fellow painter and friend SJ Peploe every year from 1919 until 1932. Only requiring a small board for each sheet to be stretched, all his painting paraphernalia could be carried in a small bag as he went about the island. Any who have visited will attest any routes leaving the relative security of the machar are rough, rocky and dangerous, particularly around the North End. Here he has crossed the Island to the Atlantic coast, to Port Ban just north of the Bay at the Back of the Ocean. There is a deep, secluded bay and beautiful sandy beach divided by a rocky shoal in the centre. Cadell painted here many times including a well-known oil of the high rocky promontory behind the bay, the site of the iron age Dun Bhuirg. Here he has set up on the south of the bay on the tidal Eilan Didal looking north over the quiet waters of the best swimming beach on the island. The range of blues are highly characteristic, the waters reflecting the summer sky.

FCB Cadell RSA, RSW (1883–1937)

35. Iona, c.1925 watercolour, 17 x 24.5 cm signed lower left provenance Private collection, Edinburgh

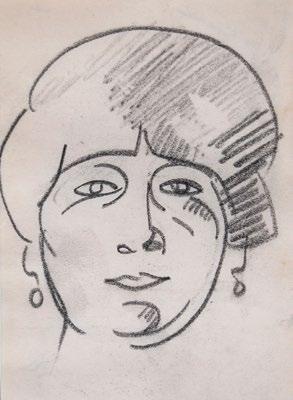

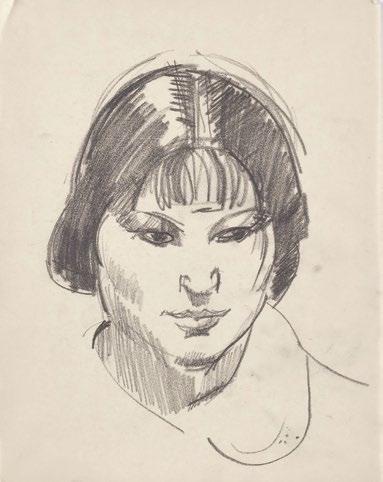

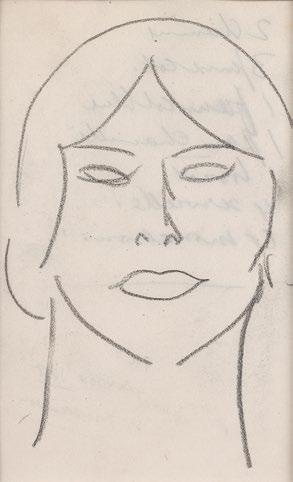

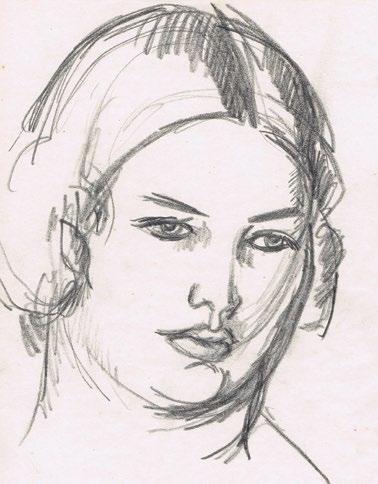

One of Fergusson’s most frequent subjects for drawing and in oil paint is a simple, female head, often full frontal, sculptural in its simplicity. Many are Meg, with her distinctive almondshaped eyes, many more are her students, in particular her star dancer Kathleen Dillon, the inspiration for John Galsworthy’s Spring and the Four Winds, first performed in 1913. Others were friends who would agree to model and whose names have often been lost and together they make up a profuse tribute to beauty and elegance.

Clockwise from top left:

36. Janice, London, 1918 conté, 25.6 x 20.4 cm

37. Meg, 1925–30 conté, 25 x 20 cm

38. Ida Rubenstein, c.1918 conté, 14 x 11 cm

39. Margaret Morris, c.1918 conté, 17.5 x 11.5 cm

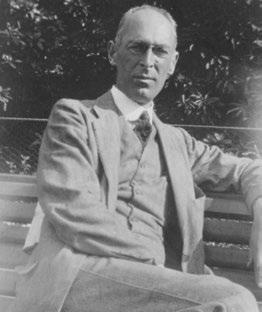

Fergusson in his Paris studio, c.1910. © The Fergusson Gallery, Perth & Kinross Council

George Leslie Hunter stayed in California when his family returned to Scotland in 1898. He was already determined to be an artist and moved to San Francisco, the town Robert Louis Stephenson called the ‘Smelting pot of the races’. Someone else described it as ‘Montparnasse with six-shooters’. Hunter found studio digs in one of the terraces overlooking the panorama of the bay. Years later Hunter recalled his time with great affection, getting a square meal at the Hotel de France or Lola’s for fifteen cents, drawing constantly, finding his subjects in the music halls, street markets and theatres of China Town. He worked hard, joining the Californian Society of Artists – what Hunter’s biographer TJ Honeyman called the ‘Salon des Refusés’ of San Francisco, though it is not recorded that he ever sold a painting. He did derive an irregular income from commissions from newspapers and magazines and befriended the writers Bret Harte and Jack London for whom he also made illustrations.

Hunter made a trip to Paris in 1904, returning via New York where he briefly kept a studio. He came back to hard work and the prospect of an exhibition. All hopes were dashed when his studio was destroyed in an earthquake on the 18th of April 1906. Hunter was out of town, but was left with no more than the clothes he wore and the contents of his weekend bag.

Our drawing may well be one of those acquired from SS White of Philadelphia by Honeyman after the artist’s death. White had met Hunter in Paris in 1904 and acquired the sketches. The title may well be original although it is now recorded that Hunter visited New Orleans. Instead, the subject may represent a commission most likely for a book illustration. The dominant male figure is strikingly similar to the illustration which is plate 4 in Honeyman’s Introducing Leslie Hunter entitled The Luck of Roaring Camp from Bret Harte’s story of 1868. The drawing has a strong narrative element and is typical of Hunter’s best early work; strong, direct, dramatic and highly skilfully handled medium.

40. The Flower Market, New Orleans, c.1900–1904 watercolour, white chalk and conté on paper, 29 x 23 cm signed lower left

provenance

Tillywhalley Gallery, Milnathort

SJ Peploe (1871–1935)

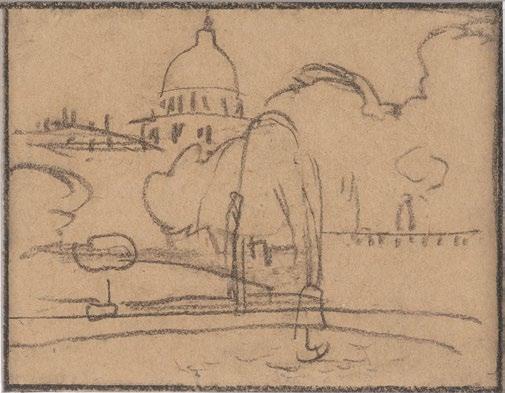

This small, charming drawing in conté crayon was made on an early trip to Paris, around 1907. Peploe drew every day, carrying a sketch book in his pocket. Here in the Luxembourg Gardens, he would have been thinking about a painting, considering the proportions of his panel and masses of the composition. The view is across one of the great ponds in the Gardens looking to the distinctive profile of The Pantheon sitting on the Montagne Sainte-Genevievre.

SJ Peploe (1871–1935)

41. The Pantheon from the Jardin du Luxembourg, 1907 conté on paper, 8.5 x 10.5 cm exhibited

The Winter Collection, Cyril Gerber Fine Art, Glasgow, 1996 provenance

The Artist’s family; The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

RSW, RGI (b.1937)

This work, which was published on the front cover of Duncan’s 2015 exhibition Works on Paper, features the shore of Culzean in Ayrshire. Shanks knew the landscape around Culzean, after visiting annually with a group of students from Glasgow School of Art. However, this painting was created after his retirement in the winter of 1984. Here Duncan stands at the edge of the Glenside Burn, capturing the energy of the water as it rushes to meet the Firth of Clyde.

Duncan Shanks RSA, RSW, RGI (b.1937)

42. The Shore – Culzean, 1984 watercolour, 29 x 60 cm signed lower left exhibited

Duncan Shanks – Works on Paper – 1957–2013, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2015, cat. 28 provenance Private collection, Edinburgh

Duncan Shanks sketching on the shore at Culzean, 1984. Photograph by Una Shanks

‘In the endless natural sequence, which colours the Scottish landscape, there is one constant and that is change. Only in front of nature with paint on paper can I throw caution to the wind and act on impulse. There is still a thrill as a painter, in catching a moment in time, when the familiar is transformed and the mundane becomes magical. It is an act of discovery, revealing the endless pictorial possibilities of the valley around me, when seasonal changes in my riverside garden become a kaleidoscope of colour. I drew the same view almost daily between September 2012 and June 2013, moving between the lush enclosure of summer green, through the transient and startling yellows of autumn, to bare open vistas, made fragile and luminous in the low winter sunlight.’

43. Reflections, February, c.2013 acrylic on paper, 70 x 100 cm signed lower right exhibited

Duncan Shanks – Drawing the Year, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2013, cat. 11 provenance Private collection, Edinburgh

Duncan Shanks RSA, RSW, RGI (b.1937)

Duncan Shanks, 2012. Photograph by John McKenzie

Duncan Shanks RSA, RSW, RGI (b.1937)

Duncan Shanks, 2012. Photograph by John McKenzie

Humphrey Spender (1910-2005) was a British artist, designer, and photographer and brother of the poet Stephen Spender. After the War, Spender shifted away from photography towards art and design and went on to become a successful textile designer and painter as well as becoming a tutor at the Royal College of Art (1953–1975). Spender had initially studied architecture in London but in 1933, he set up a photographic studio. After two years working at the Daily Mirror under the name Lensman, he photographed in Bolton for the Mass Observation movement (an independent body aiming to record the reality of daily life in Britain). In 1938 he joined the newly founded, illustrated magazine Picture Post, where he took similar documentary photographs. Following a brief period of conscription in 1941, he spent the rest of the war as an official photographer and interpreter of photo-reconnaissance pictures. His work is held in numerous public collections including the National Galleries of Scotland, National Portrait Gallery, London and the Imperial War Museum, London.

Humphrey Spender’s tapestry design Phoenix was designed for Dovecot Studios in 1950, after their incorporation as Edinburgh Tapestry Company, and completed in 1951. At this time, resident Dovecot weavers were producing tapestries designed by English designers who were well established in the 1930s, which is referenced in Elizabeth Cumming’s book, The Art of Modern Tapestry: Dovecot Studios Since 1912. The studio at that point was directed by Ronald Cruickshank who would leave in December 1953. The weavers of the Spender tapestry were probably Cruickshank himself, possibly with John Loutit. This rare and prestigious tapestry was formerly owned by Sir Harry Jefferson Barnes, who acquired the Edinburgh Tapestry Company in 1954, when Sax Shaw was appointed artistic director. Whilst Phoenix was not shown at The Festival of Britain of 1951, the year it was woven was a significant time. The Festival marked the Centenary of The Great Exhibition and was a nation-wide initiative of regeneration and optimism after the dark years and destruction of the War. The visual arts were displayed throughout the country and in London on the South Bank a major exhibition took place. The title, Phoenix (Blackbird), makes its impulse to regeneration explicit and the choice of the blackbird as a quintessentially British songbird, both ordinary and emblematic, celebrates creativity. The design is brilliantly adapted for the medium using both colour and movement to push the motif to its crescendo.

Harry Jefferson Barnes was the Director of the Glasgow School of Art 1964–1980. In conjunction with John Noble, Barnes acquired the Edinburgh Tapestry Company in 1954 at The Dovecot Studios and assisted running it. Barnes also served on the Saltire Society and the National Trust for Scotland and was on the board of the Citizens Theatre. During the 50s and the 60s, Barnes’ interests in Scotland gravitated to the crafts and he was involved in the creation of the Scottish Crafts Centre in Edinburgh and was appointed Convener of the Panel of Assessors who judged the work submitted to the Centre. He also represented the Scottish Crafts Centre as a member of the Joint Crafts Committee. He was then invited by the Secretary of State to be a member of the Consultative Curriculum for six years and, arising out of this, was invited to act as Chairman for the Working Party looking at the teaching of art in secondary schools. The Report from this, Curriculum No. 9, was published. Barnes was influential in setting up the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society, of which he was Chairman for many years.

Humphrey Spender (1910–2005) and Edinburgh Tapestry Company (now Dovecot Studios)

44. Phoenix (Blackbird), 1951 tapestry, 168 x 137 cm monogrammed lower right, inscribed to frame verso woven by Dovecot Studios, probably woven by Ronald Cruickshank and John Loutit

Dovecot Tapestries exhibition invitation, 1950, featuring cartoon by Humphrey Spender. Cover designed by George Mackie

There are twenty-three Humphrey Spender artworks held in public collections, the majority are paintings but also include photographs from his former career in photography. His paintings express fine technical detail and his subjects embraced social history, surrealism and abstraction. Composition from 1966 appears as a landscape but it is also an astute study in colour, contrast and illusion. At the time, the world was moving towards space travel, so perhaps this offers an image of an imagined, alien place. The effect is serene.

Humphrey Spender (1910–2005)

45. Composition, 1966 oil on board, 39.5 x 58.5 cm signed and dated lower left

(b.1955)

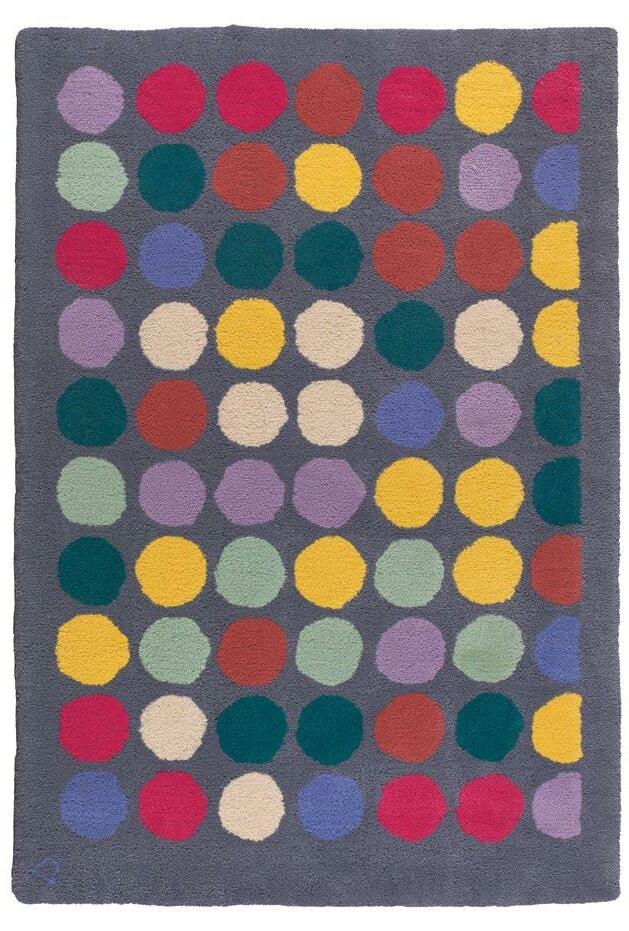

Edinburgh-based textile artist Linda Green created this rug with Dovecot Studios in 2010 for the exhibition Intimate Spaces: Material Lives. Seeking to represent an aspect of the Edinburgh Maggie’s Centre through the design, Linda settled on the Centre’s colour palette as her focus. She had worked as a colour consultant for the Centre’s architects and used her knowledge of the Centre’s colour scheme to create a design comprised of a playful pattern of dots. The colours in Linda’s design were then painstakingly colour matched by Dovecot Master Weaver Douglas Grierson to create the desired effect. The carefully spaced dots are typical of Linda’s wider interests in order, random processes, and geometry.

Linda Green MA(RCA) (b.1955) and Dovecot Studios

46. Rug, 2010 gun-tufted rug, 172 x 117 cm tufted by Douglas Grierson

(b.1942)

Paragon is both a landscape, still life and portrait. Sylvia von Hartmann works to her own rules and uses her own highly developed technique to build a personal narrative layer by layer. She lived in the Scottish Borders for over twenty years before making her home in the heart of the Old Town in Edinburgh and Paragon is a composition of the Eildons, flowers from her garden, the interior of her home and a selfportrait which looks both inward and outward.

Sylvia von Hartmann RSW (b.1942)

47. Paragon, 1994 pigment, ink and watercolour, 35 x 48 cm signed and dated lower left exhibited

Roger Billcliffe Gallery, Glasgow, April 1995 provenance Private collection, Aberdeen

Sylvia von Hartmann, May 2022. Photograph by Dennis Conaghan

Aleksander Zyw was born in Lida in 1905, a small town then in north-east Poland, before moving to Warsaw at a young age. He trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw before embarking on a travel scholarship which took him across Europe, often on foot, with extended periods on the sunny shores of the Mediterranean. Like many young artists of that time he gravitated towards Paris, and set up a studio there in 1934 but continued to travel during the summer months. Zyw sustained his seasonal lifestyle up until 1939 when it stopped abruptly with the outbreak of war. His early work was impressionist in style, with a focus on capturing the effect of light on the landscape, often featuring subjects from travels to Italy and the South of France. In 1939 he joined the Polish army in France and, after the French armistice, escaped through Spain to Britain. After service as a war artist with the Polish forces in Britain he married and settled in Edinburgh’s Dean Village in 1946. The War acted as catalyst for Zyw, and in the immediate post-war period his art turned inward, away from naturalism in favour of an individual form of expressionism. Zyw first exhibited with The Scottish Gallery in 1945 and was the subject of an Edinburgh Festival

exhibition at The Gallery in 1957. He exhibited across Europe as well as in the UK including a major retrospective held by the Polish National Union of Artists in Warsaw in 1967. In Scotland, public exhibitions included a retrospective with The Scottish Arts Council in 1972, the Talbot Rice in 1975 and the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art titled The Nature of Painting in 1986. The last thirty years of his life were spent largely in Tuscany, Italy, where he and his wife set up an olive farm. From the 1960s his art turned in other directions and he developed a new relationship with the natural world, creating seemingly abstract images based on minute studies of nature. He died at his home in Castagneto Carducci in 1995. In recent years Aleksander Zyw has been represented in exhibitions at The Scottish Gallery, in Parma, Volterra and in the Borders Museum in Hawick. In December 2022, he was the subject of the exhibition Portrait of a Soldier, which focused on his wartime experiences. The show was held in the recently renovated Polish Ex-Combatant’s House in Edinburgh, in conjunction with the Polish Consulate.

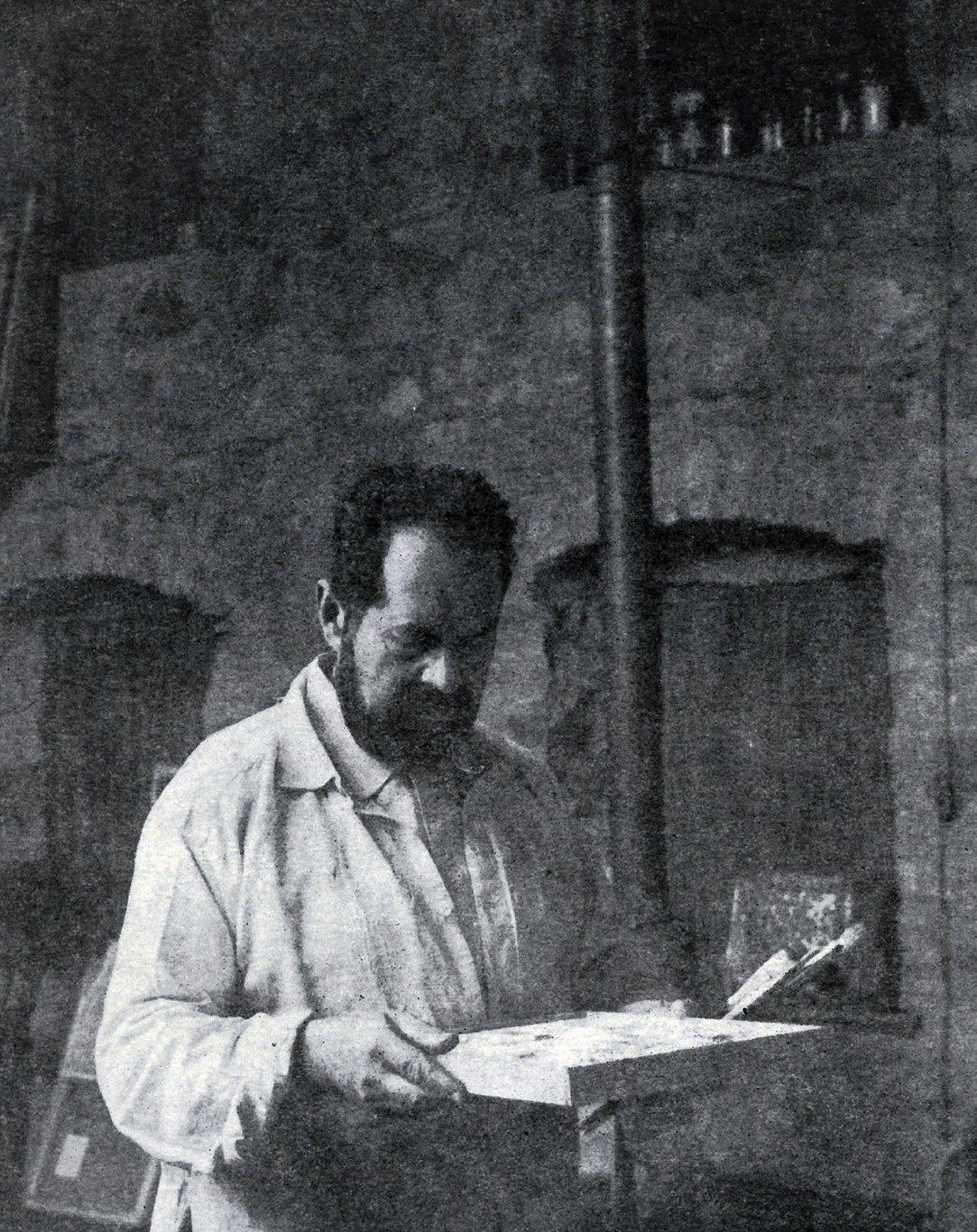

Tommy ZywLeft: Portrait of a Soldier exhibition catalogue; Galerie Galanis-Hentschel Invitation, Paris, 1951 Opposite: Zyw in his Edinburgh studio, c.1967.

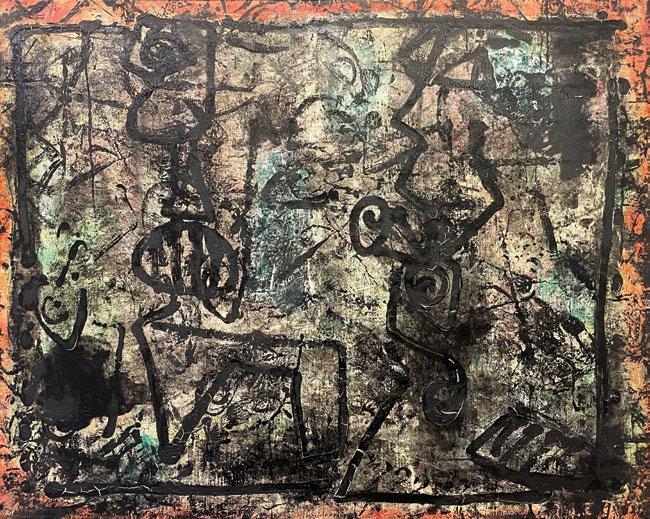

Although based in Scotland, working from his studio in Edinburgh’s Dean Village, Zyw’s outlook was distinctly European. Since the war his practice developed at pace, turning his back on naturalism in favour of an expressionist language in an attempt to make sense of the new world order. A decisive moment in his post-war development as a painter, was a trip made to France and Italy in 1949. The discovery of Paul Klee and a reengagement with the School of Paris was a helpful influence, and his paintings began to move towards an intellectual abstraction, rather than purely a vehicle for emotion. This painting, dating from 1951 was exhibited at his first Paris exhibition of the same

year. In it Zyw has built up the surface of the painting with layers of colour, before applying intuitive black line with a loaded brush. The hieroglyphs are freely drawn, in them animals, numbers and shapes are combined in a fretwork of graphic line which is at once ambiguous but equally compelling. The French art critic Frank Elgar described the paintings in his Paris exhibition as ‘halfway between essence and existence, these paintings seem at first illogical, arbitrary, because they escape gravity and vulgarity. But whatever the origin of their conception and the secrecy of their execution, one cannot dispute their power of fascination.’

Aleksander Zyw (1905–1995)

48. Zarysy (Outlines), 1951 oil on canvas, 41 x 51 cm signed upper right exhibited Zyw, Galerie Galanis-Hentschel, Paris, 1951, cat. 973