MODERN MASTERS

Festival Edition

MODERN MASTERS

Festival Edition

August 2024

16 Dundas Street, Edinburgh EH3 6HZ

+44 (0) 131 558 1200 scottish-gallery.co.uk

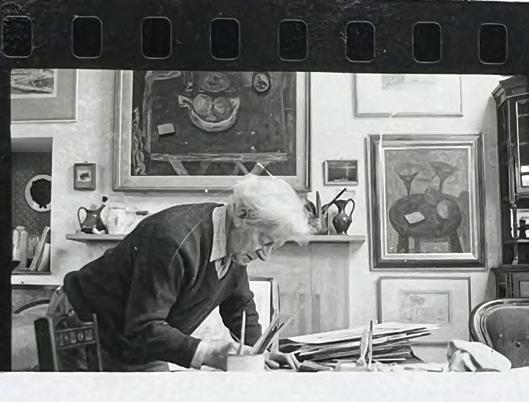

William Gillies at his Temple home and studio with his labrador, Jet.

Photographs by Jessie Ann Matthew, December 1972

Modern Masters | The Many Days

Colours went by

As shades of colour and a rose tree was Where space must thicken and where time must pause.

Brackloch by Norman MacCaig, 1962

In 1972, William Gillies agreed to be photographed by his neighbour and art student Jessie Ann Matthew, at his home and studio in Midlothian. The encounter resulted in an intimate portrayal of the artist’s life, revealing his warmth, humour, generosity, and studio practice.

Sir William Gillies (1898–1973) was a renowned figure in Scottish modern art, celebrated for his landscape and still-life paintings. He was a pioneering Principal at Edinburgh College of Art, and significantly impacted the Scottish art scene. Gillies was a man who lived in the moment, enjoyed the company of others, and dedicated his life to art and artists which included poets, writers and musicians. Gillies’ legacy has quietly contributed to a distinctive visual language unique to Scotland. Gillies maintained a lifelong

association with The Scottish Gallery, enriched by the many students and colleagues he taught and worked alongside, many of whom were also represented by The Gallery.

In this Festival edition, we include many of Gillies’ peers, colleagues, and former students. We bring together the Peploe family – S.J. Peploe, Denis Peploe, and Clotilde Peploe – and reflect on their legacy of colour. Additionally, we introduce some lesser-known women artists as the wider debate in the art world continues to challenge perceptions of artists. Our Modern Masters series showcases The Scottish Gallery’s unique ability to blend meaningful historical insights with the best of Scottish contemporary art.

Christina Jansen | The Scottish Gallery

The beneficent lights dim but don’t vanish. The razory edges dull, but still cut. He’s gone: but you can see his tracks still, in the snow of the world.

Praise of a Man by Norman MacCaig, c.1990

Kate Downie, Beached Boat, Solway Firth, 2023 (cat.26) (detail)

Barbara Balmer, Posie with Crabapple Bough, c.1979 (cat.4) (detail)

ARTISTS

Barbara Balmer (1929–2017)

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004)

Elizabeth Blackadder (1931–2021)

Robert Henderson Blyth (1919–1970)

Victoria Crowe (b.1945)

Alan Davie (1920–2014)

Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002)

Kate Downie (b.1958)

Joan Eardley (1921–1963)

William Gillies (1898–1973)

Audrey Johnson (1919–2005)

Brenda King (1934–2011)

Brenda Lenaghan (1941–2020)

William Littlejohn (1929–2006)

Sheila Macmillan (1928–2018)

Margaret McGavin (1924–2004)

Leon Morrocco (b.1942)

Ann Oram (b.1956)

Ann Patrick (b.1937)

James McIntosh Patrick (1907–1998)

Clotilde Peploe (1915–1997)

Denis Peploe (1914–1993)

S.J. Peploe (1871–1935)

Anne Redpath (1895–1965)

Joan Renton (b.1935)

Una Shanks (b.1940)

Robert T H Smith (1938–2016)

Geoff Uglow (b.1978)

Barbara Balmer (1929–2017)

Barbara Balmer studied at Edinburgh College of Art after the Second World War and subsequently enjoyed a travelling scholarship to France and Spain and a further trip to Italy with a group led by Douglas Percy Bliss. She married the artist and graphic designer George Mackie and they spent many years in Aberdeen where Balmer lectured at Gray’s School of Art between 1970 and 1980. She exhibited in Edinburgh with The Gallery having one-person shows in 1975, 1980, 1985 and 1988. In 1995, Aberdeen Art Gallery held a retrospective of her work which travelled to Dundee, Lincoln and Coventry. Latterly the family was based in Stamford in Lincolnshire spending the summers in Tuscany. Her artistic interests included the early Italian primitives, Stanley Spencer, Giorgio Morandi and the Edinburgh painter Cecile Walton, but her individual take on landscape and still life was purely her own. An intense, personal vision of landscape and the natural world is translated into ethereal interior/exterior paintings and still life, sharply in focus but soft in tone, graphically sophisticated but enigmatic. Her works are held in many private and public collections including The Scottish National Portrait Gallery, The Royal Collection and Perth, Dundee and Lincoln Art Galleries.

‘Pictorialist, stylist, classicist, modernist. She is all of these things and more. Instantly recognisable at 50 yards. Gentle like a dove. Feminine, if the expression is excusable, but tough in discipline, draughtsmanship and the sense of the fitness of things she brings together. I am reminded of Saladin’s scimitar scything silk. Landscape and interiors veiled in pink and lilac mist. Skies showering confetti instead of snow. Breezes are zephyrs. Beds invite the rapture of sleep. Intimate portraits beguile. She is the sorcerer and illusionist, yet the world she makes is real.’

W. Gordon Smith quote from The Scotsman obituary by Tom and Pam Wilson, January 2018

Public collections include:

Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

City Art Centre, Edinburgh

Dundee Art Galleries and Museums

Herbert Art Gallery & Museum

Glasgow Museums

Leicester Museum & Art Gallery

National Galleries of Scotland

Perth Art Gallery

Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen

Royal Collection

Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh University of Edinburgh University of Stirling

Barbara Balmer painting, c.1980.

Photograph by Robert Mabon

1. Fruits from Manolo – Almuñécar, Andalucia, c.1985 watercolour and pencil on paper, 70.5 x 54 cm signed lower left; signed and title inscribed verso

Barbara Balmer (1929–2017)

2. Basket of Apples, c.1970 watercolour and crayon on paper, 43 x 51 cm signed lower left; signed and title inscribed on label verso

Barbara Balmer (1929–2017)

signed lower right

Barbara Balmer (1929–2017)

3. Little Still Life, c.1975

watercolour on paper, 23.5 x 29 cm

exhibited Barbara Balmer Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1975, cat.44

4. Posie

Bough, c.1979 watercolour and pencil on paper, 71 x 52 cm signed lower left; signed and title inscribed verso

Barbara Balmer (1929–2017)

with Crabapple

Barbara Balmer (1929–2017)

5. Marquee in a Walled Garden, c.1980 oil on board, 92 x 122 cm signed lower left

Rendezvous Gallery, Aberdeen

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004)

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004) was a leading member of the St Ives group of artists and made an outstanding contribution to the advancement of post-war British art. Last year, filmmaker and director Mark Cousins directed a new film A Sudden Glimpse to Deeper Things, which is a cinematic immersion into Wilhelmina Barns-Graham’s art and life. The film will be on general release in 2025.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, known as Willie, was born in St Andrews, Fife, on 8 June 1912. Determining while at school that she wanted to be an artist, she set her sights on Edinburgh College of Art, where she enrolled in 1932 and graduated with her diploma in 1937. At the suggestion of the College’s principal, Hubert Wellington, she moved to St Ives in 1940. Early on she met Borlase Smart, Alfred Wallis and Bernard Leach, as well as Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and Naum Gabo who were living locally at Carbis Bay. Her peers in St Ives include, among others, Patrick Heron, Terry Frost, Roger Hilton, and John Wells. Barns-

Graham’s history is bound up with St Ives, where she lived throughout her life. In 1951 she won the Painting Prize in the Penwith Society of Arts in Cornwall Festival of Britain Exhibition and went on to have her first London solo exhibition at the Redfern Gallery in 1952. She was included in many of the important exhibitions on pioneering British abstract art that took place in the 1950s. In 1960, Barns-Graham inherited Balmungo House near St Andrews, which initiated a new phase in her life. From this moment she divided her time between the two coastal communities, establishing herself as a Scottish artist as much as a St Ives one. Wilhelmina Barns-Graham was represented by The Gallery throughout her career. Important exhibitions of her work at the Tate St Ives in 1999/2000 and 2005, and the publication of the first monograph on her life and work, Lynne Green’s W. Barns-Graham: A Studio Life, 2001, confirmed her as one of the key contributors of the St Ives School, and as a significant British modernist. She died in St Andrews on 26 January 2004.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, 1980. Photograph by Robert Mabon

At my age, there’s now no time to be lost. I say to myself, “Do it now, say it now, don’t be afraid.” I’ve got today, but who knows about tomorrow? I’m not ready for death yet, there’s still so much I want to do. Life is so exciting; nature is so exciting. Trying to catch the one simple statement about it.

That’s what I’m aiming for, I’ll keep on trying.

W. Barns-Graham, A Studio Life, p.271

[Untitled], 1998, is from her Millennium series.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004)

6. [Untitled], 1998

acrylic on paper, 25.5 x 37.5 cm signed and dated lower right

provenance

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust

However absorbed Barns-Graham is in the dialogue between her materials and her imagination, what goes on outside the window proves irresistible to an artist who is captivated by the beauty of the world. Work of the late 1990s is often a direct response to the pleasures of colour and movement on the beach below her St Ives studio: the activity of figures about to run into the sea may become a construction of oblongs, or stripes, moving across the picture plane? In the creative process, the relationship between external and internal, observed, and invented, is complex and multi-faceted: there are no rules of degree or proportion. Whatever the impulse or inspiration of her imagery, the

artist’s exploration of line, form and texture, colour, light, and space (their interrelationship and effect one upon the other, their ability to convey physical, emotional, and spiritual insight), is firmly rooted in experience. To look with the outer eye and to see with the inner eye is the mark of a natural painter. Barns-Graham is quintessentially this: an artist who imagines in form and colour, whose first response to experience is to express its equivalent in the language of painting. The studio is where outer and inner vision become one.

W. Barns-Graham, A Studio Life, p.271

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004)

7. Beach Dance, 1997–98

acrylic on paper, 58 x 77.5 cm signed and dated lower right

provenance

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust

Elizabeth Blackadder

(1931–2021)

For more than half of the one hundred and twenty years or so that we consider the modern period, the images of Elizabeth Blackadder have surprised and beguiled us. She is now considered a national treasure, like Burns or Scott or Raeburn; her body of work a monument to quiet application, restraint, enlightenment, and cultural variety. Her work has the simple poetry of a haiku but is presented with the perfect pitch of a tuning fork.

Flowers are often present in Elizabeth Blackadder’s still life compositions and increasingly they became a subject in themselves. She acquired her first garden with her move to Queens Crescent in 1963. There can be no other painter as prolific in the number of things included in her painting: toys, wrappers, ceramics, postcards, fabric, fruit (real and carved), boxes, bowls, parcels and so on. When she travelled, she accumulated things and then, eventually, they might be put to use, often crumpled, upside down, rescaled, flattened or partial.

Elizabeth enjoyed a long, consistent history of exhibitions with The Gallery over the long span of her professional life from the late 1950s onwards. She was honoured with a retrospective at The National Galleries of Scotland in 2010 and her long association with the Royal Academy (she became an Associate in 1971 and was the first woman to be a member of both the RA and RSA) provided her with a national profile. Her list of honours and exhibitions is extraordinary, and it is hard to grasp the breadth of her achievement across many media. For many she is best known as a watercolourist, for many more her printmaking allowed collectors to own her work. Her oil painting practice dominated, even though she also worked predominantly on paper, always maintaining separate studios for each medium. This diversity of approach she shared for forty-five years with her husband John Houston – they met as students – and whom she sadly lost when he died in 2008.

Guy Peploe

Elizabeth Blackadder in her garden, 1989.

Blackadder shares with William Gillies, her tutor, friend and colleague from Edinburgh College of Art, a profound understanding of medium, sophistication of composition and subtle use of colour. But her work goes further in its restraint, subtlety, and originality to mark her out as the leading light in the Edinburgh School. In Still Life with Daisies, she has painted a jazzy frieze at the foot of the canvas which conventionally might have represented a table edge, defining a picture space, but she has defied this visual expectation by balancing her vase of delicate daisies over its edge. There are no straight lines, and the simplicity and formality of the central composition is further modified by her use of scratchy lines and tonal shifts in her background. She had painted in Harris in 1974 and the harsh, subtle beauty of a pared down landscape produced an effect in all her work. August saw her major one-person show at The Scottish Gallery for the Edinburgh Festival, exactly fifty years ago.

8. Still Life with Daisies, 1974 oil on canvas, 50.5 x 50.5 cm signed and dated lower right

Elizabeth Blackadder (1931–2021)

9. Still Life and Peony, 1977

watercolour on paper, 41 x 51 cm signed and dated lower right; artist name and title inscribed verso

Elizabeth Blackadder (1931–2021)

Elizabeth Blackadder visited Japan in 1985, and also after her retirement from Edinburgh College of Art the following year. Her work had long chimed with Japan’s aesthetic style, but from then she added distinct Japanese subject matter, from kimonos to chopsticks to formal gardens.

Elizabeth Blackadder (1931–2021)

10. Still Life with Chinese Boxes, 1978 watercolour on paper, 61.5 x 99.5 cm signed and dated lower left exhibited

Austin/Desmond Fine Art, London

11. Parrot Tulip and Irises, 1979 watercolour on paper, 29.5 x 30 cm signed and dated lower right; artist name and title inscribed verso

Elizabeth Blackadder (1931–2021)

Elizabeth Blackadder (1931–2021)

12. Summer Flowers, 1979 watercolour on paper, 25 x 30 cm signed and dated lower right; artist name and title inscribed verso

John and I didn’t have cats until we went to live at Queen’s Crescent in Edinburgh. I wasn’t too sure about drawing cats because I thought the subject of cats and flowers are dangerous – they can be too pretty or something… So I began looking at a lot of paintings of cats by Bonard and Gwen John. That’s when I started drawing cats. They’re flexible. I looked at anatomy books on cats. They would come into the studio because they love lying on paper, or they would lie on a painting or a stack of paintings. They are quite difficult to draw! You have to do lots of drawings because they’ll move – even when they’re sleeping they’ll turn their head over.

Elizabeth Blackadder, 2006

Elizabeth Blackadder (1931–2021)

13. Coco and Sophie, 1981 pastel on paper, 43 x 53 cm signed and dated lower left

exhibited Mercury Gallery, Edinburgh, 1982

Robert Henderson Blyth

(1919–1970)

Bobby Blyth, as he was known amongst his fellow artists, was a popular, familiar figure in the academic and institutional corridors, in Edinburgh and Aberdeen. He took his diploma at Glasgow School of Art before serving in the Army Medical Corps from 1941 until VE Day. Gillies then offered him work at Edinburgh before he moved to Aberdeen by way of Hospitalfield in 1954, a similar route to that of his colleague Ian Fleming. He had already become a friend of the young students McClure, Houston and Blackadder, with whom he remained close. His response to War had been in a few surrealist influenced subject pictures but his subsequent development was in lyrical landscape owing something to Gillies and English Neo Romanticism. He became head of drawing and painting at Gray’s in 1960 and had great influence on the next generation of painters emerging from the college, a post he maintained until his death in 1970. Henderson Blyth’s painting moved through distinct phases from early work where line, structure and texture were uppermost in his mind to his late work where form dissolves into colour. This striking work of Summer Fields shows the shared influences of his Gray’s colleagues Wishart and Fleming. Like the compositional devices used in Fleming’s

harbour scenes, Blyth has revelled in capturing the immediate texture of the stone dyke, before it recedes into the distance, leading the viewer into the rolling landscape of Aberdeenshire. A brilliant draughtsman, Blyth made distinctive choices on the information he would include. Here, he divides the distant fields and fences into flat areas of pattern, under a darkening North Sea sky.

Robert Henderson Blyth, c.1969. Photograph by Richard Collins

Robert Henderson Blyth (1919–1970)

signed lower right

exhibited Robert Henderson Blyth – Memorial Exhibition, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1972, cat.26

14. Summer Fields, c.1958

oil on canvas, 61 x 51 cm

Victoria Crowe (b.1945)

Victoria Crowe studied at Kingston School of Art from 1961–65 and at the Royal College of Art, London, from 1965–68. At her postgraduate show, she was invited by Sir Robin Philipson to teach at Edinburgh College of Art. For thirty years she worked as a part-time lecturer in the School of Drawing and Painting while developing her own artistic practice. She lives and works in West Linton, Edinburgh, and Venice. Her first one-person exhibition, after leaving the Royal College of Art, was in London and she has subsequently gone on to have over fifty solo shows. Her first solo exhibition at The Scottish Gallery was in 1970. In August 2018, The Scottish National Portrait Gallery held a retrospective exhibition of Crowe’s portraits, Beyond Likeness. In 2019, the City Art Centre, Edinburgh, honoured Crowe’s career with a four-floor retrospective, 50 Years of Painting Her retrospective enjoyed a record number of visitors and embraced every aspect of Crowe’s practice and featured over 150 artworks. The Scottish Gallery hosted a complementary exhibition in September 2019, 50 Years: Drawing & Thinking. Victoria Crowe is a member of the Royal Scottish Academy and the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolours. In 2000, her exhibition A Shepherd’s Life, consisting of work selected from the 1970s and 80s, was one of the National Galleries of Scotland’s Millennium exhibitions. The exhibition toured Scotland and was re-gathered in 2009 for a three-month exhibition at the Fleming Collection, London.

Crowe was awarded an OBE for Services to Art in 2004 and, from 2004–07, she was a Senior Visiting Scholar at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge. The resulting work, Plant Memory, was exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy in 2007 and subsequently toured Scotland. In 2009, she received an Honorary Degree from The University of Aberdeen and, in 2010, was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In 2013, Dovecot Studios wove a large-scale tapestry of Crowe’s painting Large Tree Group. This collaborative tapestry was acquired for the National Museums Scotland. In 2015, Crowe was an invited artist-in-residence at Dumfries House and, in 2016, a group of work by the artist was acquired by the National Galleries of Scotland. Crowe was commissioned in 2014 by the Worshipful Company of Leathersellers to design a forty metre tapestry for their new hall in the city of London; it took over three years to weave and was installed in January 2017. In collaboration with singer Matthew Rose, Crowe produced a 70-minute video of her work, Winterreise: a Parallel Journey. The film was shown in Snape Maltings; Wigmore Hall, London; in 2018 at the Weesp Chamber Music Festival in the Netherlands; and in South Korea in 2023.

Victoria Cowe will be the subject of a solo exhibition at the Pier Art Centre, Stromness in August 2024. The Scottish Gallery celebrates Victoria Crowe’s 80th birthday in 2025.

Victoria Crowe with Gemma, c.1980. Photograph by Jessie Ann Matthew

Victoria Crowe found the reality of life, harsh and idyllic by turn, around her new home in the Pentlands at Kittleyknowe, to be the roots of her development in Scotland, lending her the confidence and fortitude to develop into the great painter she is today. She came first in 1970, happier to commute into Edinburgh College of Art after moving from London, headhunted by Robin Philipson to the School of Drawing and Painting; in the country she was a different person. Her neighbour Jenny Armstrong was a hill sheep farmer, in an environment where being neighbours meant something, a kinship in times of adversity, sharing in times of plenty. The winter fence, hencoop and kennel, the view out from the warm comfort of a room with a coal fire, the twilight shape of a familiar landmark, all became fit subjects, little pieces creating a world of hardship shared and a landscape fully inhabited.

Victoria Crowe OBE (b.1945)

15. Corner of the Garden (Summer, Kittleyknowe), c.1972 oil on board, 71 x 91 cm signed lower right

Victoria Crowe OBE (b.1945)

16. Corner of a Garden, West Linton, c.1979 watercolour on paper, 55 x 75 cm signed lower left

Victoria Crowe OBE (b.1945)

17. Trees and Gold Sky, 1985 oil on canvas, 51 x 61 cm signed lower right

Alan Davie (1920–2014)

Alan Davie was born in Grangemouth and studied at Edinburgh College of Art from 1937 to 1940. After his war service, he performed as a jazz musician, wrote poetry, designed textiles, and made jewellery. From 1953 to 1956, Davie taught at the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London, under the principal and artist William Johnstone (1897–1981). Davie developed an interest in African and Pacific art. In 1971, he first visited St. Lucia and subsequently spent six months a year there, incorporating Caribbean influences into his work. Over the years, his art was also influenced by Paul Klee, American Abstract Expressionism, Zen Buddhism, and Indian mythology.

Davie was the first British—and likely the first European—artist to recognise and embrace Jackson Pollock’s innovations in ‘action painting’. The quietly spoken yet formidable Scot charted his own expressive course, which was less an imitation of Pollock and more, as fellow artist Peter Doig recently described, ‘like an expanded Paul Klee… but much more physical, much more visceral’.

By the time of his breakthrough exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery in 1958, Davie’s improvisational paintings were among the most avant-garde in British art. Monumental works such as The Creation of Man and Sacrifice (Tate Gallery) combined exuberant physicality with a ritualistic, symbolist quality. His Edinburgh Festival exhibition Magic Pictures was held at The Scottish Gallery in 1979.

‘When a black mark is placed on a white paper, both paper and pigment immediately become transformed. A relationship is set up between them – a marriage: the white becomes a mythic substance, evocative of infinity and sonorous depth.’

Alan Davie, 1994

Alan Davie.

Photograph: Scotsman publications

Alan Davie (1920–2014)

18. Island Phantasy, 1999 screenprint, 56 x 67 cm, edition of 50 signed lower right

Alan Davie (1920–2014)

19. Opus Drawing, 28, 2001 ink on paper, 30 x 26 cm signed and dated upper middle

Alan Davie (1920–2014)

20. Wall of Jewels, Opus G2461, 2004

gouache on paper, 30 x 23 cm signed and dated upper right

provenance

The Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

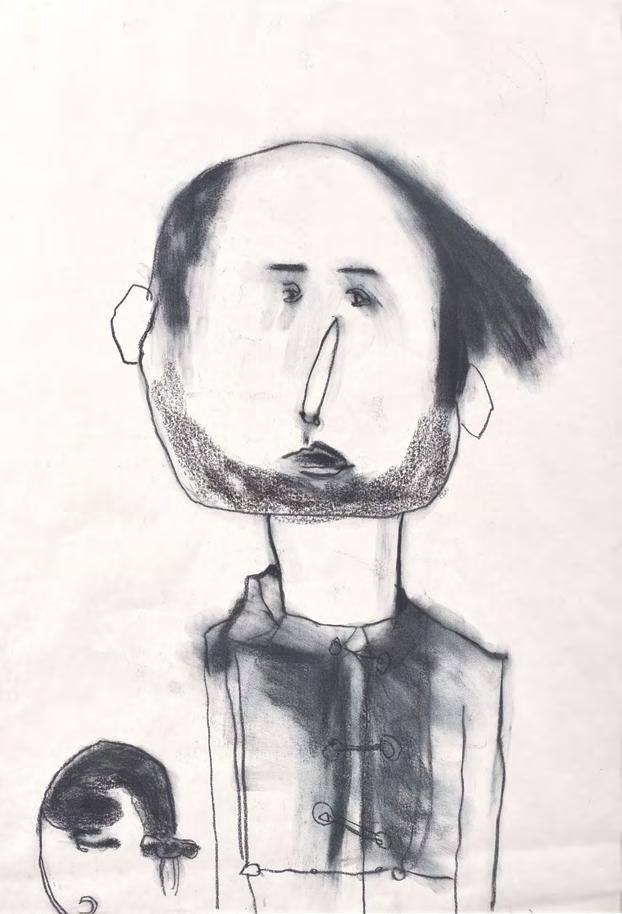

Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002)

Pat Douthwaite is a painter with an exceptional gift of externalising her own fantasy world, filling and quickening a two-dimensional space with nervously vital lines and emotionally expressive colour. Whether her subjects are legendary women – and these, like Theda Bara, Belle Starr, Amy Johnson, have been recurrent obsessions – or a shivering, cowering dog, or a palm tree sorely out of its element in an alien, northern winter, Douthwaite seems to find it necessary, like a method actress, to inhabit the idea, to get inside the skin of the role, as it were. Her paintings, often grotesque for all their elegance, can range in mood from tragicomic frenzy to angst-ridden melancholy, but they usually have a certain exciting theatricality in common.

Cordelia Oliver, 1981

Pat Douthwaite, 1984.

Douthwaite’s most significant subject throughout her life was the female figure, clothed or naked, real (in the sense of a real woman) or grotesquely imagined. Her heroines: Amy Johnstone, Mary Queen of Scots, an alphabet of Goddesses, American Bandits, are at once self-portraits and celebrations of female power. The woman is often accompanied by a creature – a sort of Pullmanian daemon.

Douthwaite visited Skye and Barra in the 1980s and drew seagulls, puffins and people, the latter invested with huge character. Douthwaite was a prolific draughtswoman, favouring a large sheet. Her drawings are usually of a single, arresting subject made with charcoal and coloured chalks, using white and coloured paper. The starting point for a painting or drawing by Douthwaite is always particular: an historical figure, a character, an observed incident or self-portrait.

Public collections include:

Aberdeen Art Gallery

Art in Healthcare

City Art Centre, Edinburgh

Ferens Art Gallery

Fife Collections Centre

The Hepworth, Wakefield

Museum of Contemporary Art, Warsaw, Poland

National Galleries of Scotland

Paisley Museum & Art Gallery

University of St Andrews

University of Stirling

Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Like all her portrayals of women, Sunglasses is a self-portrait, whatever the ostensive subject. It is always worth noting the composition: a ghost face concealed by large black sunglasses, lit cigarette suspended from pale pink lips, asymmetric hair and body hidden within a black polo neck and large, oversized yellow coat with wide collar and a patterned trim to the hem. Douthwaite worked on the floor, using charcoal and pastel with great tonal subtlety. The background colour is near uniform but not neutral: she creates the psychological keynote in her choices: black, red or green, against which her heroines have a heightened, theatrical presence.

21. Self Portrait with Sunglasses, 1976 pastel on paper, 65 x 50 cm signed upper right

Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002)

Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002)

22. Barra Man with Cat, c.1987 charcoal on paper, 81 x 56 cm

signed and dated upper right

Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002)

23. Dog Laying Down, 1989 charcoal and pastel on paper, 54 x 41 cm

Pat Douthwaite’s son Toby Hogarth has recalled that his mother: ‘adored animals above all, preferred them to humans any day. I suppose because they gave her undivided affection no matter what. She collected butterflies and beetles and always had a soft spot in her heart for animals of any kind. She became closer to them as life went on, I think because she’d had bad experiences with people’.

Simon Martin, Director, Pallant House Gallery

Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002)

24. Snow Leopard Sniffing Flowers, Kashmir, 1984 oil on canvas, 152 x 122 cm signed and dated upper left

Kate Downie (b.1958)

Kate Downie was born in North Carolina but was raised from the age of seven in Scotland. She studied at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen before travel and residencies took her to the United States, The Netherlands, France, Japan and Norway.

As a landscape painter/printmaker she studies the relationship of the human coexistence within nature, with works defined by good draughtsmanship and a sense of movement. Downie has established studios in places as diverse as a brewery, a maternity hospital, an oil rig and an island underneath the Forth Rail Bridge. She has taught both in art colleges and universities and has directed major public and community art projects since 1987.

As President to the Society of Scottish Artist from 2004 to 2006, Downie co-curated contemporary visual art projects of international standing, including an exchange exhibition with Indian artists and the Bodyparts live

art Festival at the RSA in Edinburgh. Her work appears in many public and corporate collections including the BBC; Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art; Gracefield Art Gallery, Dumfries; Aberdeen Art Gallery; Rietveld Kunst Academie, Amsterdam; City of Edinburgh Council; HM The King; Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow & New Hall College Art Collection in Cambridge. In 2005, the artist was shortlisted for the Jerwood Drawing Prize, and in 2008 became a member of the Royal Scottish Academy.

Like the Scottish Artists Joan Eardley and D.Y. Cameron in the last century, Downie has spent the past thirty years exploring an artistic vision for both the extremes of a Scottish urban landscape as well as Scotland’s coastal ‘edgescapes’ beyond the cities. Downie re-located to Fife in 2018, establishing Birchtree Studios in 2019, which has since become a hub for creative collaborations both locally and internationally.

Kate Downie in Elie, Fife, 2024. Photograph by Michael Wolchover

25. North Beach, Iona (Walking the Dog), 2022 Chinese ink and watercolour on Xuan paper, 99 x 51 cm signed lower right; title inscribed verso

Kate Downie (b.1958)

Beached Boat,

, 2023 monotype, 52 x 100 cm signed lower right; title inscribed verso

Kate Downie (b.1958)

26.

Solway Firth

Joan

Eardley

(1921–1963)

There is an enduring fascination for Joan Eardley far beyond her unconventional life and early death at the age of forty-two. In her short career it is still hard to believe what this artist achieved; Eardley was an exceptionally gifted artist of her generation. Born in 1921 in Sussex, Joan Eardley’s family moved to Scotland in 1939 and a year later she joined the Glasgow School of Art. She found subjects in the shipyards of Clydebank and Townhead, at first the run-down tenements and buildings and later the children and street life around the Maternity Hospital on Rottenrow where the character of the people and the place became the vital subject of her work. Her art education was finished with scholarship visits to Paris and the cities of Renaissance Italy and back in Scotland she ventured with her art school friends to Arran and back to the south of France. However, by the fifties, Joan Eardley divided her life between her studio in Townhead and the fishing village of Catterline, a place she had discovered in the

Northeast of Scotland after a visit to recuperate from illness after her solo exhibition at the Gaumont Cinema gallery in Aberdeen. Eardley felt at ease in these two contrasting localities and over the succeeding decade, as if by accident, she created an epic vision of the world from no more than two streets and one small fishing hamlet. The slums of Townhead are no more, the harsh realities memorialised by the honesty of her vision, the spirit of the people invested in its children captured, enduring like no other example in the history of art. Catterline remains unchanged, and the village is inevitably a place of pilgrimage for the thousands who admire the artist’s deep-felt engagement with nature on the Kincardineshire coast. Joan Eardley was a regular gallery exhibitor from the 1950s under the care of our former Director William Macaulay, and The Gallery remains strongly associated with the artist since her passing.

Joan Eardley in Catterline, c.1955. Photograph by Audrey Walker

Much has been written about Joan Eardley and the Samsons, a Townhead family of perhaps 12 kids, who drifted in and out of her studio and became the subject for which she is most celebrated. This interior depicts Andrew, the eldest and first of the siblings she painted. It is dated as early as 1949 by Eardley’s biographer Christopher Andreae, but relates closely to her portrait of Angus Neil (page 112 of Joan Eardley, Lund Humphries, 2013). Neil sits passive, eyes downcast, cigarette burning in his fingers, but the boy looks about, posed with elbow on the table, hand tucked into his bomber jacket; he won’t be there for much longer.

On the reverse, is an unfinished painting of Townhead with a group of children in the foreground. The view is of the back of the close – an area directly behind the tenement buildings where the drying greens (for hanging washing) were situated; a playground of sorts. It was very common for artists to reverse a picture if they favoured another subject and didn’t want to waste the canvas. Seated Figure with Table is therefore a portrait with interior and exterior combined, which together reflects a period of post-war Britain.

Joan Eardley RSA (1921–1963)

27. Seated Figure with Table, c.1949–53 oil on canvas, 51 x 63.5 cm painting verso

provenance

Private collection, Edinburgh

illustrated

Christopher Andreae, Joan Eardley, Lund Humphries, 2013, p.99

Reverse side of Seated Figure with Table

William Gillies (1898–1973)

William George Gillies, born in Haddington in 1898, died in tranquillity at his luncheon table on Sunday, 15th April 1973. His painting stands out in any contemporary environment – his idiom was very personal and always unmistakably Scottish. After a spell at Edinburgh College of Art, interrupted from 1917 to 1919 by military service, he was awarded a travelling scholarship which enabled him to study some time in Paris and later travel in Italy. He was elected ARSA in 1940, becoming an Academician seven years later. He was awarded the CBE in 1957 for services to Art in Scotland. The accolade of knighthood was bestowed on William Gillies in 1970. In 1971 he was made Royal Academician, London.

There was something birdlike about him: his tempo was faster than normal and while most people walked, Bill Gillies ran – effortless in all his many activities and in conversation he often anticipated what was going to be said to him. In short, he used time to the full, being a prolific painter who managed also to be an inspiring teacher. At the Edinburgh College of Art his first junior appointment in 1925 led to his becoming the Head of the School of Drawing and Painting. As a climax to his career as a teacher he became the Principal of the College from 1961 to 1966. It has been estimated that Gillies completed well over 2,000 paintings and works on paper. He was an exciting colourist, and his paintings were full of light and poetry. Dedicated as he was to the gravity of his work which ever contained an original quality of Scottish character, Bill Gillies, an inveterate maker of wines and jams, regarded life with an air of detached amusement.

Broadly speaking, it could be said that there are two kinds of painters. Those who find their inspiration abroad and those who can only blossom in their native soil, Gillies being a perfect example of the latter. He found all the material he wanted in Scotland – Highland landscape and Lowland townscape, in Fife and the Lothians, in little seaports and bare hillsides, especially in the charming village of Temple where he lived and died. It would be a mistake to say that Gillies, the master of the Scottish scene, was indifferent to the many contemporary trends of art – it would be more true to say that he had something so fundamental, so pressing to say that he was not side-tracked by the passing fashions and whims of the day and his art will endure when a great deal that is fashionable will have long since been forgotten.

Sir William MacTaggart, edited obituary from the Royal Scottish Academy, 1973

In this edition, Gillies is connected to the following artists:

Barbara Balmer Former student

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Former student

Elizabeth Blackadder Former student and colleague

Robert Henderson Blyth Former student

Alan Davie Former student

Joan Eardley Peer and champion

Leon Morrocco Former student

Denis Peploe Former student and colleague

S.J. Peploe Peer and colleague

Anne Redpath Peer

Joan Renton Former student

Robert T H Smith Former student

William Gillies at his Temple home and studio. Photographs by Jessie Ann Matthew, December 1972

William Gillies, Pittenweem, c.1947 (cat.28) (detail)

Gillies was a prolific watercolourist and his approach varied throughout his life. In the earlier period he only employs the brush, sometimes wet on wet, with a minimum of drawing which can lend a spontaneous and gestural quality and often captures a particular moment or some fleeting atmospheric effect. From the 1940s he tended to draw first, with pencil or pen and then use monochrome or colour washes. Pittenweem, painted in 1947, the year he was elected an Academician has been painted on a large sheet of watercolour paper on a magnificent summer’s day. He has painted the dappled light on the pavement and road and has colour washed the detail of the seafront houses, gables and pantile roofs.

Gillies held several one-person shows with The Scottish Gallery in his lifetime and in addition there was often a ‘bin’ of unframed Gillies watercolours displayed in the premises on Castle Street which were constantly on sale at the ‘bargain’ price of 20 guineas.

William Gillies (1898–1973)

28. Pittenweem, c.1947 ink and watercolour on paper, 47 x 67 cm signed lower left

exhibited

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1949

William Gillies at his first exhibition with The Scottish Gallery in 1949, where Pittenweem was originally exhibited and sold.

Unlike the old masters, Gillies’ drawings were rarely studies for future oil paintings. Instead, most of them were completed as a first response to the scene in front of him and in this sense they offer a far more intimate and personal view than many of his paintings. His line varies from a languorous grace to breathless fury, every mark, scribble and dot offers an image of something observed by a passionately aware and purposeful mind. Unlike his watercolours which can be contemplative, his drawings are lighthearted, energetic and spirited.

William Gillies (1898–1973)

29. The Pentlands from near Temple, c.1950 pencil on paper, 21 x 35.5 cm signed lower left exhibited Steigal Fine Art Ltd, Edinburgh

Each time Gillies selected his sister Emma’s pots for a still life he acknowledged her. Her death in 1936 was one of several personal losses that Gillies bore in life. This small still life seems perfectly formed: the four ceramic vessels help define the space, two in diagonal conversation, two intimately close, the stems of the delicate poppies offering an embrace. Colour is strong and harmonious, and the paint deliciously applied.

William Gillies (1898–1973)

30. Iceland Poppies, c.1959 oil on canvas, 36

46 cm signed lower right

provenance

The Visionary Painter, The Scottish Gallery, 2023

x

Gillies divided his energy between oil and watercolour; painting in oils was his studio routine, whilst he was happiest working in front of the landscape on his watercolour block. The originality and spontaneity of his landscapes on paper in pencil, pen and ink and pure watercolour, form the core of his reputation. When filmed in 1970, he spoke eloquently about his watercolour practice: ‘My landscape painting began with watercolour and a great part of my work has continued in this medium and I feel the peculiar qualities of the medium have had a strong influence on my conception of landscape... I have perhaps opened many people’s eyes to some unexpected, some subtle beauties in our daily surroundings. This has been, I hope, a by-product of my own enjoyment of what I perceive and my great delight in the very act of handling the paint.’

Portmore is a small estate sitting 800ft up on the side of a Peeblesshire hill near Eddleston.

William Gillies (1898–1973)

31. Ploughed Fields, Portmore, c.1960 watercolour on paper, 54.5 x 76 cm signed lower right

exhibited

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh; Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour, Edinburgh

Gillies enjoyed visits to Wester Ross and Cromarty during the summers of the 1940s. This joyous oil, which will have been made en plein air, renders the effects of sunshine on the sea and landscape of Loch Alsh, looking east towards Balmacara. His swift notations with the brush captures the joy he experiences in the landscape, with the accuracy of painter whose technical ability allows him to translate reality into an image imbued with a poetic quality.

‘A landscape has to be digested. Working from nature, one is distracted by the perpetual change – I get led astray from the original conception. I seek the permanent in nature.’

William Gillies, 1961

William Gillies (1898–1973)

32. Kyle of Lochalsh, c.1946 oil on canvas, 35 x 45 cm signed lower right

exhibited Cyril Gerber Fine Art, Glasgow

Audrey Johnson (1919-2010)

Audrey Johnson is an artist about whom we know very little, but whose work deserves wider recognition. Her deceptively simple and honest still-life paintings have quietly influenced many of today’s social media-savvy popular artists. Johnson drew inspiration from her home, garden, and the joy in everyday things, which is reflected in her subtle and delicate compositions. These works, distilled down to their most essential forms, create an intimate experience for the viewer.

Although we don’t know much about Johnson’s training or the awards she may have received, we do know that she lived in the picturesque hamlet of Cartmel Fell in Cumbria with her husband and fellow artist, Claude Harrison (1922–2009). Harrison trained at Preston College of Art and Liverpool College of Art before serving in the Royal Air Force during the war. He married Johnson in 1947.

Audrey Johnson, Still Life in Jug, 1988 (cat.34) (detail)

Audrey Johnson (1919–2005)

33. Cyclamen, 1985 oil on board, 28 x 23 cm signed and dated lower right

Audrey Johnson (1919–2005)

34. Still Life in Jug, 1988 oil on board, 23 x 18 cm signed and dated lower right

Brenda King

(1934–2011)

Brenda King was born in Cumbria and studied art at Lancaster College of Art and at the Royal College of Art in the 1950s. While living near London, she exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. During the 1960s and 70s, she held numerous shows in the Southeast before relocating to Cornwall in 1975. King’s paintings are characterised by a folk style and her subject often features compositions of a table-top with crockery in front of a window overlooking a coastal scene. She was married to Jeremy King, and shared working studios in St Just, Cornwall.

Brenda King (1934–2011)

35. Flowers in a Cup, 1973 oil on board, 18 x 14 cm signed and dated lower left

Brenda Lenaghan (1941–2020)

Brenda Lenaghan was born in Galashiels in 1941. She studied at Glasgow School of Art between 1958–63 before joining Bernat Klein (1922–2014) in Galashiels. Klein was an artist, colourist and textile designer who founded his business in the Scottish Borders in 1952, where he produced innovative fashion fabrics for the couture houses of Europe. Lenaghan worked in the modernist building set in the landscape of Selkirk, which was designed by the pioneering architect Peter Womersley. The tweed fabrics which Lenaghan contributed to the design of, featured in Chanel and Dior’s haute couture collections. The colour experience during her time with Klein, informed her palette and compositional studies. When her son moved to Japan, her painting began to absorb oriental influences. Lenaghan won numerous awards throughout her career, including the SSWA’s Anne Redpath Award in 1975 and 1983. In 1984, Lenaghan was elected a member of the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour.

Brenda Lenaghan, Rendezvous Gallery, Aberdeen, 2014. Photograph by Press and Journal

36. Two Figures, c.1990 oil on board, 42 x 42 cm signed lower left

Brenda Lenaghan (1941–2020)

Brenda Lenaghan (1941–2020)

37. Figures in a Garden oil on board, 76 x 76 cm signed lower right

William Littlejohn

(1929–2006)

Littlejohn, who was born in Arbroath and lived there for most of his life, was known for his modernist watercolours and iconic imagery.

He studied at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, Dundee and, after national service in the RAF and work as an art teacher at Arbroath High School, he studied at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen, where he became a lecturer and later principal of the school of painting. Littlejohn was elected a member of the Royal Scottish Academy, the Royal Glasgow Institute and the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour.

From the early 1960s, The Scottish Gallery held regular solo exhibitions of his work.

Littlejohn’s work is held in numerous public collections including the National Gallery of Scotland and the Royal Scottish Academy.

William Littlejohn, 1980.

Photograph by Robert Mabon

William Littlejohn (1929–2006)

38. At a Shrine, 1998 watercolour on paper, 53 x 31 cm signed and dated lower middle; title inscribed verso

Sheila Macmillan (1928–2018)

Sheila Macnab Macmillan was born in Glasgow in 1928. She studied Geography at Glasgow University and went on to train as a teacher. Her painting talent was encouraged by her artist uncle Iain Macnab RE ROI (1890–1967) who persuaded Sheila to come to London to study fine art. Iain Macnab had been Principal at Heatherley’s Art School (1925–1940) and became the founding Principal of the Grosvenor School of Modern Art. Macmillan’s London influences and Glasgow School foundations gradually evolved into a distinctive and individual style. She worked en plein air and her work is semi-abstract. Her chief subject is the landscape where her training as a geographer and understanding of land formation explores the delicate balance of the seasons and interaction between man and the environment. Macmillan painted in Scotland, Spain, France and Italy.

Sheila Macmillan (1928–2018)

39. Late Summer Flowers, c.1980s oil on canvas, 51 x 61 cm signed lower left

Sheila Macmillan (1928–2018)

40. Hillside oil on canvas, 61 x 61 cm signed lower right

exhibited

Sheila Macmillan (1928–2018)

41. Church and Garden Sheds, Dalserf, c.1995 oil on canvas, 49 x 59 cm signed lower right

The Macaulay Gallery, East Linton, 1995, cat.57

Sheila Macmillan (1928–2018)

42. Grey Trees, Jackton, c.1990 oil on canvas, 49.5 x 59 cm signed lower left

exhibited The Macaulay Gallery, East Linton, cat.102

Sheila Macmillan (1928–2018)

43. Boatyard, c.1980 oil on canvas, 44.5 x 55 cm signed lower left exhibited The Macaulay Gallery, East Linton, cat.62

Margaret McGavin (1924–2004)

Margaret McGavin (known as Sonny) was born in Glasgow and attended Hutcheson’s Girls Grammar School. She studied at Glasgow School of Art during the Second World War and was awarded the Hugh Adam Crawford Prize, the SRC Prize, the Guthrie Prize for Portraiture, and the David Donaldson Prize. She was awarded the Robert Hart Trust Bursary in 1944 and 1945. She taught art in schools in Glasgow from 1945–1947. In 1947, Margaret married George Macdougall McGavin, a fellow artist, whom she met in the studio of David Donaldson. Together, their lives were committed to teaching and painting, often exhibiting together. She worked in watercolour and oils and in 1994 she received the Royal Diploma of Membership from the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour. McGavin is also a past president of the Scottish Society of Women Artists, now Visual Arts Scotland.

McGavin’s work has a clarity that recalls her near contemporary Barbara Balmer, and she deployed strong colour in the best tradition of Scottish belle peinture

‘For many years now I have been attracted to a variety of imaginative elements which I enjoy combining in a poetic way. The scale of those elements vary greatly within one image, generating a mysterious set of dreamlike scenarios, with a cast of theatrical characters of interchangeable scale sometimes found within a toy theatre, a circus tent or a hot air balloon drifting through the sky, wandering in the landscapes or floating on the sea.’

Margaret McGavin

McGavin hanging her degree show work at Glasgow School of Art, 1945.

Margaret McGavin (1924–2004)

44. Garden of Dreams, c.1995

acrylic on board, 40.5 x 45.5 cm signed lower left

Leon Morrocco (b.1942)

Leon Morrocco, the eldest son of painter Alberto Morrocco, was born in Edinburgh and studied at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and The Slade, London before studying at Edinburgh College of Art under William Gillies. He was a lecturer in drawing and painting at Edinburgh College of Art from 1965–1968, and then took up a similar post at the Glasgow School of Art from 1969–1979 before moving to Australia to take up the post of Head of Fine Art at the Chisholm Institute in Melbourne. He has been painting full-time since 1984. It is fifty years since Leon Morrocco held a one-man show with The Gallery in 1974.

Leon Morrocco had a studio in Rome from 2000–2009. Pink House near the Vatican is a major work from the artist’s time in Rome and it encapsulates the quintessential vibrancy and dynamic essence of Italian life, characteristic of Morrocco’s lively, colourist paintings. The gate serves as a focal point, anchoring the composition while offering a window into the bohemian atmosphere of Rome. The artist has employed deep, rich colours and layered shadows to evoke the warmth and intensity of the midday sun. Intricate details such as

colourful patterns from hanging laundry, a bicycle parked against a wall, and a ladder leaning on crumbling architecture add to the narrative of everyday life. Road signs and architectural nuances further enhance the composition. Two women engaged in conversation on balconies enriches the scene with a sense of community and social interaction.

Leon Morrocco (b.1942)

45. Pink House near the Vatican, 2004 oil on canvas, 90 x 95.5 cm signed and dated lower left

Leon Morrocco in his London studio. Photograph by Dan Weill

Ann Oram (b.1956)

Ann Oram was born in London in 1956. She studied at Edinburgh College of Art between 1976 and 1982 and became a part-time lecturer at the College in the 80s and 90s. She was elected a member of the RSW in 1986. Ann Oram’s first exhibitions with The Gallery were exotic, rich urban landscapes: buildings familiar and foreign invested with character and mystery. Her subjects range around Scotland, in France, Italy and Spain and she continues to paint the interior with still life; flowers both cut and gathered, objects collected, like Anne Redpath before her, from her travels and a keen eye for shape and form. Today she works from her home and studio in the Scottish Borders, and it is here that she looks to the landscape changing with the seasons for inspiration.

Ann Oram in her Borders studio, c.2018.

Ann Oram (b.1956)

46. Flowers from the Garden, c.2010 watercolour and ink on paper, 112 x 119.5 cm signed lower right

exhibited Ann Oram, Following On, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2010, cat.41

Ann Patrick (b.1937)

Ann Patrick is the daughter of the renowned artist James McIntosh Patrick (1907–1998).

Born in Dundee, she studied at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and at Patrick Allan Fraser School of Art, Hospitalfield, Arbroath, from 1954 to 1958, under the tutelage of Alberto Morrocco and David McClure. She married fellow artist Richard Hunter in 1960. Although she lived and worked in Arbroath, she frequently painted abroad, particularly in Tuscany. Patrick’s work reflects her surroundings, giving formal permanence to ephemeral subjects such as fruit, flowers, and aspects of the sea and landscape.

The Walled Garden depicts a quiet corner of her garden at home. We sense that this is a warm spring day; two of her cats are sleeping in the flower beds in the foreground and there is an inviting cast iron bench flanked by two fruit trees on the cusp of coming into flower. The composition invites us to take a seat, enjoy the warmth, and just rejoice as nature bursts into life.

Her paintings can be found in the permanent collections of Aberdeen, Angus and Dundee council and the Fleming Collection, as well as the collection of the late H.R.H. The Duke of Edinburgh.

Ann Patrick (b.1937)

47. The Walled Garden, c.1970 oil on board, 76 x 97 cm signed lower right

signed lower right; signed and title inscribed on label verso

Ann Patrick (b.1937)

48. Sweet Lovers Love the Spring, c.1985 oil on board, 26 x 19 cm

Ann Patrick (b.1937)

49. Primroses, c.1988

watercolour on paper, 24 x 24 cm

signed lower right; signed and title inscribed on label verso

provenance

Fine Art Society, Edinburgh, 1988; The Rendezvous Gallery, Aberdeen

James McIntosh Patrick

(1907–1998)

James McIntosh Patrick, born in Dundee, Angus, in 1907, is recognised as Scotland's foremost landscape painter of the 20th century. He studied at the Glasgow School of Art from 1924 to 1928 under Maurice Greiffenhagen, where he won numerous prizes and a postdiploma scholarship. His meticulous landscape etchings caught the attention of a London print dealer, leading to an important contract in 1928. However, with the collapse of the print market in the early 1930s, he turned to oil painting, maintaining his attention to detail in landscapes. His oil paintings from this period, marked by incredible detail and formalism, include Winter in Angus, 1935, which was acquired by the Tate Gallery. During the Second World War, he served in the Camouflage Corps in North Africa and Italy, painting watercolours later exhibited at the Fine Art Society in 1946. Post-war, he taught at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, his own practice focused on landscape painting,

depicting the Angus countryside and Dundee. Elected to the Royal Scottish Academy in 1957, James held solo shows at Dundee City Art Gallery in 1967 and 1987, with a 90th birthday celebration at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 1997. McIntosh Patrick, who was married to Janet Watterson and father to artist Ann Patrick, was created OBE in 1997.

James McIntosh Patrick at Brae of Balshandie in 1956.

Photograph: DC Thomson

50. Carse of Gowrie, 1973 watercolour on paper, 37.5 x 55 cm signed lower left

James McIntosh Patrick OBE (1907–1998)

S.J. Peploe

Denis Peploe

Clotilde Peploe

W.W. Peploe

Denis, Guy and Elizabeth Peploe

Margaret Peploe

Willy, S.J. & Denis Peploe

W.W. Peploe (1869–1933)

The Peploe Family A Legacy in Colour Family Tree

S.J. Peploe (1871–1935)

Margaret Peploe (née MacKay) (1873–1958)

Clotilde Peploe (née Brewster) (1915–1997)

Willy Peploe (1911–1965)

Denis Peploe (1914–1993)

Clare Peploe (b.1942)

Mark Peploe (b.1943)

Lucy Peploe (b.1958)

Elizabeth Peploe (née Barr) (b.1938)

Guy Peploe (b.1960)

Lola Peploe (b.1983)

The Peploe Family | A Legacy of Colour

There are many examples of artist dynasties in the history of art. In earlier times art was sometimes a family business, the virtues and attributes of one generation continued in the next. In more recent times as the artist sought to assert his or her individuality and with less stress on craftsmanship and apprenticeship, there was no business to inherit. But, the genetic component (however uncertain) would sometimes out and other nurturing aspects of an artist’s development perhaps made a career more likely in the next generation. And it is not unusual for artists to marry artists, refreshing the gene pool, as is the case with the Peploes.

S.J. Peploe

Samuel John was born in 1871 and for him there was no precedent for the professional artist he was to become. He had two siblings, an elder brother Willie and a younger sister Annie and they became orphaned when first their mother died and then their father Robert Luff Peploe when Sam was thirteen. He was a determined young man and had to face considerable opposition to his choice of career from the Trustees tasked with looking after the Peploe children, appointed by the Commercial Bank of Scotland where their father had acceded to the General Managership before his early death. But succeed he did, developing as a painter through the crucible of change from 1890–1920 to emerge as Scotland’s first internationally recognised modern painter and one of The Scottish Colourists.

W.W. Peploe

His brother, known as W.W. Peploe, was also a talented artist, but never took the leap to imagine a professional career. Instead, he worked, eventually as manager with his father’s bank, agent at the Stockbridge branch from 1901. The brothers were close, sharing a passion for music, both playing the piano, and they often holidayed together, particularly after the Great War, travelling to Iona where Willie made competent drawings of the vistas. His friends in Edinburgh included Canon John Gray and his partner André Rafallovich who ran a literary salon from their house in the Grange and formed a direct link with the milieu of the fin de siècle London and Paris. In 1910, he produced a limited edition of a book of fifty poems called The Heart of a Dancer, published by Otto Schulze and Company in Edinburgh. It was dedicated to his brother “To S.J. Peploe, dearest brother and friend in love and memory.” Sam had married in early 1910 and moved to Paris, his and Margaret’s first child Willy was born in Royan in August and Willie may have felt a sense of loss. Two further volumes appeared in 1912: Thebaida and Roses in Return. Colin Scott Sutherland, whose essay published in 1998 remains the only piece of critical writing on the artist, suggests that the frontispiece of the latter book, in the criss-cross latticework of the background, suggests a link to the Vorticists.

W.W. Peploe lived on until 1931, but never enjoyed good health and apart from a few works in pencil he seems to have desisted from making art and there were no further publications of his poetry. Both his art and poetry deserve renewed attention from the surveyors and anthologisers of this vital period of transition into Modernism.

Willie Peploe and Clotilde Peploe

The first son of Sam and Margaret, named Willie after his uncle, went on to study History at Magdalen College, Oxford, and have a career as an art dealer interrupted by The War. He also painted, but perhaps aware of the superiority of both his father and younger brother and wife, chose not to pursue this path. He fell in love with Clotilde Brewster in Florence in the late thirties. He knew her brother Harry from Oxford and had begun a book about the community of Mount Athos, but events overtook everyone and Willy and Cloclo married in 1939 and escaped to Africa. The route back to Britan was impossible, and the young couple spent the War years in Kenya where Willy worked for the Colonial Office and where the first of three children were born. Clare and Mark eventually worked in the film industry, Clare marrying Bernardo Bertolucci and making several successful auteur films of her own while Mark became a screenwriter, winning an Oscar for Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor in 1987. Willy returned to his desk at Reid & Lefevre after the War and Cloclo, determined to paint, began to take time to work in Italy and Greece. She was the daughter of Christopher Brewster, an American born in Austria and Elizabeth von Hildebrandt, a daughter of an Austrian sculptor who had acquired a former monastery called San Francesco in Florence as family home and studio. Elizabeth was also a painter and she and her daughter travelled extensively for work and inspiration in Italy in the thirties. The film Grandmother’s Footsteps is a charming and beautiful biopic and meditation on the calling of the artist made in recent years by Lola Peploe, Mark’s daughter. Her typical subject is the arid, mineral landscape of Calabria and the Greek islands, complex, ancient landscapes at once fertile and hostile.

Denis Peploe

Our final family artist is Denis Peploe, the second son of Sam. He attended Edinburgh College of Art, having post Diploma time in France, Italy and Spain before enlisting in 1939 and finishing the War as a Captain in SOE. In 1946, he picked up his brushes again and began to work towards an exhibition at the Hazlitt Gallery in London and then with The Scottish Gallery. He also became a teacher at Edinburgh College of Art. Like his father he was a distinctive draughtsman and a brilliant tonal painter in oils, capable of brilliant colourism and rich, sonorous representation of the West Highlands of Scotland. When I came to The Gallery his exhibiting career was revived after some fallow decades – he had never stopped painting, and he enjoyed sell-out shows in both Edinburgh and London.

Guy Peploe

Clotilde Peploe (1915–1997)

Clotilde (Cloclo) Peploe was born in 1915. She was the daughter of Christopher Brewster, an American born in Austria and Elizabeth von Hildebrandt, a daughter of an Austrian sculptor who had acquired a former monastery called San Francesco in Florence as a family home and studio. Elizabeth was also a painter and she and her daughter travelled extensively for work and inspiration in Italy in the thirties. During the 1930s, Clotilde and her mother spent long months painting together in southern Italy, and later in Corfu and on mainland Greece. At the same time, she met Willy Peploe, son of S.J. Peploe, who she married in Athens in November 1939. Her typical subject is the arid, mineral landscape of Calabria and the Greek islands, complex, ancient landscapes at once fertile and hostile. In 2023, Lola Peploe wrote and directed an award-winning film, Grandmother’s Footsteps, which tells the story of Clotilde Peploe by her granddaughter.

Clotilde Peploe

51. Laurels and Cypresses, c.1965 oil on canvas, 89 x 74 cm signed verso; title inscribed on labels verso

provenance

Arthur Lenars & Co, Paris; New Grafton Gallery, London; Duncan R Miller Fine Arts, London

Clotilde Peploe (1915–1997)

Denis Peploe (1914–1993)

Denis Peploe was born in 1914, the second son of the celebrated Scottish Colourist S.J. Peploe. He enrolled at Edinburgh College of Art at the age of seventeen, where he was a contemporary of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham and Margaret Mellis. He won post-diploma scholarships to Paris and Florence, and took advantage of the opportunity to travel extensively in Spain, Italy and Yugoslavia. He first exhibited at The Scottish Gallery in 1947, to critical acclaim. The Glasgow Herald critic responded to the exhibition, saying he was ‘an artist born fully armed’; and The Bulletin critic wrote: ‘the general impression of the exhibition is that we have in Denis Peploe a vital and adventurous painter’. Reviewers never avoided mention of his father, and though one couldn’t confuse their work there were similarities in their approaches: each picture was a response to a particular subject, either intellectual or emotional. Guy Peploe explains: ‘While he was intimately exposed to the mainstream of European art he remained better defined as an artist who responded directly to his subject,

en plein air or in the studio. Here the challenge was a live model, or the intellectual exercise of reinvigorating the still life subject. His work remained free of political or art-world references but was at the same time formed by the century of modernism, the times of unprecedented turmoil and change to which he belonged. His response was to cleave to the idea that art was important, even redemptive, and that it could somehow describe a better, or more vital place.’

Denis, Guy and Elizabeth Peploe, The Scottish Gallery, 1985.

Denis Peploe in his Edinburgh studio, c.1980. Photograph: The Scotsman Publications Ltd

In the decade after the War, as Denis Peploe returned to civilian life and took up his brushes once more, he sought to regain his equilibrium by a return to the classicism of Cézanne, a simple, even rustic form of painting, balanced, textural, and satisfying to the demands of composition. The violin, a prop inherited from his parents, the vases, hauled back from visits to his friends John and Vivienne Guthrie in Cyprus and contrasting rug and crumpled drape are carefully posed on a studio table before the act of mimesis.

Denis Peploe (1914–1993)

52. Still Life with Violin, c.1955 oil on canvas, 63.5 x 76 cm signed lower right

exhibited Denis Peploe – Drawings and Paintings, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 2000

In a vase, inherited from his father, is a display of yellow carnations, no doubt picked from the back garden by the artist. It is a simple, delicate motif and along with the rich cobalt blue of the backdrop provides as close a link with Samuel John as Denis ever makes. However, it is unmistakably the work of Peploe fils, made entirely with a palette knife, as if his paint is hewn from gemstones, and the notion of a conventional picture space denied in favour of floating elements. The artist’s engagement with the landscape of the West Highlands, sky, crag and lochan, analyzed in masses, rendered with the same knife, has a clear affect in his studio work.

Denis Peploe (1914–1993)

53. Flowers, Blue Background, c.1975 oil on canvas, 61 x 51 cm signed lower left; title inscribed on label verso

exhibited

Paintings from the Artist’s Studio, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1984, cat.44

S.J. Peploe (1871–1935)

At the beginning of 1923, Peploe contributed 23 works to an exhibition at the prestigious Leicester Galleries in London alongside Cadell and Hunter, henceforth referred to as The Scottish Colourists. Ten of these were of a new subject: Iona. He will have likely visited the island before the Great War, but his visit in the summer of 1920 was significant and would lead him to return most years until his death in 1935. He stayed on the Atlantic side near Port Bahn, and Cadell and John Duncan were also on the island. He wrote to Margaret and the boys, who had gone to South Uist: ‘Cadell has a nice house. He has got his man out and means to use him as a model. He has been very nice to me. I have dined with him I think four times already. He has done a few sketches and got other big things started but so far sold nothing. Nor has Duncan, who is rather depressed about the weather keeping him from working… Where I stay is about two miles from anywhere. I come home from dining with Cadell after 11 o’clock, crossing a large machair which would not be easy if he didn’t lend me his electric torch. The most beautiful part of the island is the north end: white sands and beautiful rocks, looking across to Mull; but it is too far from where I am.’ Peploe was undoubtedly back in Iona the following summer, staying nearer the north end which provided all the inspiration he needed

to work very hard. His first choice for subject was the massive craggy rocks, including the distinctive Cathedral rocks which emerge from the white sands. The pink hued rock, defined with decisive dark lines, has an architectural stature. Sometimes there is a view to the Island of Storms and Mull beyond or as here to the Treshnish Isles on a high horizon over blue green waters. As his vision mellowed and a greater naturalism appeared, weather became as much the subject as the topography, but the intensity of colour he observed in the waters of the Sound of Iona in bright sunshine, varying over reefs in the shallows and sand bars, darkening out to the deep blue of the Atlantic provided endless subject matter.

Sam, Denis and Margaret at Iona, c.1925.

54. Iona, 1920

oil on panel, 32.5 x 40 cm signed lower centre, title inscribed verso

provenance

The artist’s family and thence by descent

S.J. Peploe (1871–1935)

Anne Redpath (1895–1965)

It is nearly sixty years since the death of Anne Redpath at what seems today like the young age of sixty-nine. In her late-flowering success on the stage of the art-world she became enormously admired, even revered, amongst her peers and a wide circle of friends. L.S. Lowry sought her out and took tea in her elegant flat in London Street; Reid & Lefevre, that most patrician of London galleries, held her exhibitions in the south (always the occasion for a new hat) and in Edinburgh a younger generation of painters (often friends of her painter sons) flocked to her home and studio for good conversation in an atmosphere where art mattered. Redpath was kind and generous with her fellow artists not just from professional courtesy but from a genuine warmth and sympathy. She had achieved much but all of it was hard won and well earned. She sent work to all the Scottish exhibiting bodies as well as the Royal West of England Academy and Royal Academy summer show but most importantly she showed with The Scottish Gallery enjoying close relationships with Mrs Proudfoot and then Bill Macaulay exhibiting in 1950, 1953, 1957, 1960, 1963 and fittingly in a memorial show in 1965. She was included in all the major survey and group exhibitions of Scottish art and by the time of her death had an international reputation. Like the previous

generation of colourists her practice embraced belle peinture and her subject was chiefly still life and landscape.

Guy Peploe

Ashkirk is a small village on the Ale Water, in the Scottish Borders. Redpath had returned to the Borders with her young children in the mid–1930s making the landscape an integral part of her practice.

Scottish Society of Women Artists Exhibition in RSA Galleries, 1945. Miss Perpetua Pope; Mrs F Lauglin; and Miss Anne Redpath.

Anne Redpath OBE (1895–1965)

55. Trees at Ashkirk, c.1939 gouache and charcoal on paper, 29 x 43.5 cm signed lower left

Joan Renton (b.1935)

Joan Renton was born in Sunderland, County Durham. She studied painting at Edinburgh College of Art from 1953–58, and counted William Gillies, John Maxwell and William MacTaggart amongst her teachers. After a post-diploma scholarship year in 1959, she was awarded a travelling scholarship which she spent in Spain. In 1960, she took a teaching diploma at Moray House, Edinburgh, and taught art throughout Edinburgh until 1980. Renton was elected a member of SSA in 1960, SSWA in 1972 (becoming President in 1990) and RSW in 1974. Her subject matter ranges from landscape, botanical studies and still life. The Gallery represented Renton in the 70s and 80s.

Renton’s paintings and works on paper are a revelation; her practice puts her firmly in the Edinburgh School of Painting. At her best, her painting equals that of her direct contemporary, Elizabeth Blackadder. Dark Table is a dynamic, sophisticated, and subtle still life, painted on a dark ground which allows the soft blooms of the anemones and tulips to occupy the space whilst the blue vases hold the composition in place.

exhibited Festival Exhibition, Chasing the Moment, The Edinburgh Gallery, Edinburgh, 2006, cat.21

Joan Renton (b.1935)

56. Dark Table, c.2006 oil on canvas, 69 x 69 cm signed lower right

Una Shanks

(b.1940)

Una Shanks was born in 1940 and enrolled at Glasgow School of Art in 1958, studying textiles in the progressive department headed by designer Robert Stewart. A string of teaching posts followed graduating, including a year at Jordanhill College, which was later merged with the University of Strathclyde. She lectured in teacher training at Hamilton College until 1982 before taking early retirement, enabling her to focus on her artistic practice full-time. In the eighties and nineties, Shanks exhibited regularly at the Fine Art Society (later Roger Billcliffe in Glasgow), The Royal Glasgow Institute, Royal Scottish Academy and Royal Society of Painters in Watercolour, where she was elected an RSW in 1988.

Like her husband and fellow painter Duncan, Una’s work takes direct inspiration from the wild riverside garden around their home in the Clyde Valley. A painting will grow organically on the paper, mimicking the life of the garden – cultivated, yet left to grow free and wild. Una picks flowers outside her front door, brings them into the studio and sets to work directly onto the paper, without preparatory sketches. She captures their form in beautiful, intricate detail, before allowing her imagination to take over. The empty spaces and voids between flowers and stems fill up with decorative motifs and symbols which, over many years have developed into wild, densely patterned compositions which are rich in colour. Her working method is meticulous and timeconsuming. Una is reticent to share any artistic inspirations, however similarities can be drawn with Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret MacDonald, whose work celebrated pattern and design in the natural world. Having sold almost every painting she has ever exhibited, recently to the Hunterian collection, Una’s work is highly

sought after. In recent years she has chosen to withdraw from exhibiting, so for many her work in this exhibition will be a revelation.

The Aviary, Small Birds

The aviary, an object resonant with ideas of freedom, captivity, wealth and the exotic, is a cage in which the birds can fly. For Una Shanks the complexity of its interior and bars, birds, boxes and foliage has become a visual challenge to balance complexity with order. Finding patterns in the thicket of the natural world is her painterly mission, to provide a section of natural abundance at once real and abstract, challenging the eye to move and make sense. Her fellow countryman D’Arcy Thomson found equations to explain growth patterns in plants and animals, but Shanks will include many made structures in her profuse subject, balancing the elements and the detail as perhaps only an artist can.

Duncan and Una Shanks with Guthrie, Crossford, 2023.

57. Lilies, 1992–2023 ink and watercolour on paper, 70.5 x 100 cm signed lower right

Una Shanks (b.1940)

58. The Aviary, Small Birds, 1985 watercolour on paper, 19 x 17 cm artist initials lower middle; signed and title inscribed on label verso

Una Shanks (b.1940)

Una Shanks (b.1940)

59. Hidden Garden, 2023

ink and watercolour with collage on paper, 71.5 x 70 cm

Robert T H Smith (1938–2016)

Bob Smith (Robert Turnbull Haig Smith) was born in Dunfermline in 1938 and studied at Edinburgh College of Art from 1957 and his career was both artist and educator. He married the painter, weaver, and potter Susan K Senior.

After training at Moray House College of Education, Bob taught art for two years at Darroch Secondary School before being appointed in 1965 as lecturer in design at the Edinburgh College of Domestic Science. In 1970, ECDS moved to a new campus on Corstorphine Hill and was soon renamed Queen Margaret College to reflect its expansion and the provision of a wide range of professional training and ultimately undergraduate level courses. Until retiring in 1993, Bob Smith played a key role in the institution’s rapid development, becoming in turn, head of the new departments of design, of drama and of communication studies. In 1982, he was appointed assistant principal. After retirement, he moved to Pitlochry and established a full-time studio.

Smith enjoyed six solo exhibitions with The Gallery from 1969, his last, Of Quiet Places, was held in 1994. The art historian Christopher Andreae wrote of Smith’s works: ‘These paintings seem to have emerged out of some sort of archaeology of the imagination, a dream dig. They are like the rediscovery, by means of scrupulous investigation – aided by small touches of sensitive restoration – of ancient

Robert T.H. Smith, 1980.

by Jessie Ann Matthew

wall surfaces, of long buried, much overlayered symbols of mankind’s primal concerns: earth and sky, sun and moon and tide, wave motion and pattern, growth and the cycles of nature, metamorphoses of seed into root, into stem, into leaf and into berry.’*

Public collections include: City Art Centre, Edinburgh National Galleries of Scotland

*Edited text from The Scotsman, Obituary, 2016

Photograph

Robert T H Smith (1938–2016)

60. By the Head, 1980

mixed media on board, 29.5 x 39.5 cm signed and dated lower right

exhibited

Recent Paintings, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1980, cat.2

Geoff Uglow (b.1978)

‘Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, Old Time is still a-flying, And this same flower that smiles today, Tomorrow will be dying.’

To the Virgins, To Make Much of Time by Robert Herrick, 1648

I built my studio on a marshy field in Cornwall. Over the years I have painted, I continue to cultivate the ground and plant a garden around it… broadleaf trees, an orchard… and the rose garden. They are not separate. The garden is an extension of my studio. I move between the two freely; observing, gardening… and painting. I know my garden intimately. It is a quiet place where I can observe time passing. The vision of the paintings and the garden are inseparable. Working both simultaneously is a daily practice. I breed my own roses. The garden began with about one hundred different varieties of rose and from that I have cross bred almost three hundred more. It takes time. I have collected hips and seeds from many places, including Cornwall, Orkney and Rome. The rose is special. It encapsulates everything I need in a subject. It is beautiful but also violent. It is lovely, seductive and tragic. It has a life. It is growing and changing.

Geoff Uglow, The Rose Garden, The Scottish Gallery, January 2017