7 minute read

Bait Up

How bait use and availability has changed over the years

By Erwin Bursik and Bruce Mann (Senior Scientist at ORI)

Advertisement

WHEN the very first “Crocker” ski was launched off the Durban beachfront with a determined angler on board, drawn to the abundant fish activity out beyond the reaches of a shore-bound angler, he relied on bait as one of his few methods of tempting a gamefish to strike. The only bait available to anglers at that time was frozen pilchards, aka sardines. The sight of the long, beautiful “silver fish” lying on the deck of the few Crocker skis when they beached soon persuaded more and more anglers to venture out beyond the breakers. Back then the silver fish was called barracuda — incorrectly as it later turned out — and it became known as a magnificent fighting and table fish. Today we know it as a king mackerel or ’cuda.

Those who opted to go to sea did so on very basic, homemade ski-boats powered by 2.5hp Seagull motors or any other small outboard that started to become available in South Africa after the end of World War II. Their methods for targeting ’cuda were rudimentary, to put it mildly. Tackle consisted of either cotton hand line the commercial linefishermen used for bottomfishing, or the then popular centre-pin or Scarborough reels on bamboo rods which the surf fishing fraternity of that era used.

Albie Upton, a doyen of the early days of boat fishing, related some of their methods to me:“We took a single 9/0 Limerick hook tied onto a length of baling wire, then attached this ‘trace’ to either the cord or flax line which was all that was available at the time.” Of course this was long before the advent of nylon line.

A whole pilchard was then impaled — sideways through its head — on the 9/0 hook, and then was either drifted or trolled. The trolled pilchard spun like a propeller behind a slow-trolling skiboat. The strike by a ’cuda was very exciting as they smashed the pilchards being trolled four- to five metres behind the boat. A hookup, especially on the cord handline, resulted in an incredible fight — essentially a tug of war. The few ’cuda landed were shoved into a hessian sack (streepsak) and pushed to the bow deck area where buckets of sea water were thrown over them periodically to keep them cool.

These old timers’ feedback was very minimal regarding other types of baitfish that were available to the “offshore” anglers. It seems they mainly caught fish off the beach (shad) and froze them to take to sea or else secured bait from the seine netters who pulled their nets in the Durban back beach area — around today’s Vetch’s or Addington beaches.

Shad were big in those days and trolling a 1.5-2kg shad on a single 9/0 hook didn’t land too many ’cuda but resulted in huge numbers of bite offs. You must also remember that because shad was a valuable food source for many people, they were difficult to obtain as bait.

The other fish the netters caught in fair numbers was the bony (glassnosed anchovy). In the old days they were caught from August to November in discoloured water.

Now visualise sticking a 9/0 through the head of a four-inch bony and trying to troll it! It didn’t make a very attractive ’cuda bait. With the sort of tackle available at the time one just could not target baitfish as we do these days.

Now let’s take a leap forward in time to the point where tackle selection improved and nylon line became available during the early 1950s. Things began to change dramatically in so far as trace make up and bait presentation was concerned, and that enabled off shore anglers to make up much more elegant terminal tackle. A “skelm” trace for ’cuda in those days was a single 2/0 tuna hook with two 4/0 trebles attached by marlin wire, the only trace wire available at the time. That became the standard ’cuda trace, a trace which is largely still used today by most offshore anglers, although in a much more refined format.

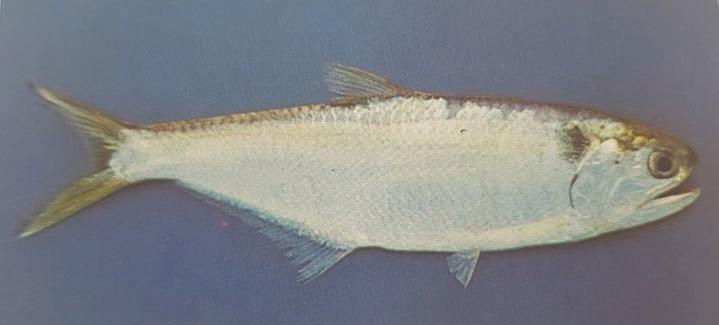

The only image of a bony (glassnosed anchovy) we could find, courtesy of A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa by Rudy van der Elst. In the early days these fish were plentiful off the KZN coast and became the bait of choice in the 1960s and ’70s.

Nowadays redeye sardines like these are found in huge shoals off the KZN coast and are popular as livebait. This photo clearly shows how the eye turns red after they’re caught which accounts for their common name.

Back to bait … the frozen sardine/pilchard was still king, but with the redesigned ’cuda trace a large bony could be trolled very effectively and a lot faster than a sard could. In addition, the bony didn’t break up when defrosted and retained its very silver colouration. Thus, when the netters got a nice haul of bonies all the members of the ski-boat club descended on them and purchased huge numbers. They froze well provided they were well packed, and thus became the bait of preference in the 1960s and early ’70s.

In the early ’60s ’cuda were few and far between, resulting in most of the Durban Ski-Boat Club boats anchoring off Natal Command on the Durban beachfront and fishing for snapper salmon which were plentiful. Two or three “trap sticks” were deployed with a small live shad under a big red cork (bung) float. If one was lucky, a ’cuda or two could also be caught while fishing for snappers.

This all taught us anglers the art of catching small fish on much lighter bait rods, reels and line, and a Paternosterstyle bottom trace with a 1kg or 2kg sinker and No. 7 longshank hooks.

This technique and variations of it produced a large variety of bait-sized fish including shad, maasbanker, bonies, sea pike, wallawalla and the odd “sand mackerel”, but neither I or any of the others who fished during that era ever caught the mackerel we catch these days. As far as I can ascertain it seems there were no mackerel in the area from Durban to Cape Vidal in that period, and to my knowledge none were caught on the lower KwaZulu-Natal south coast then either.

And then suddenly around 1990 not only did the Cape mackerel (as we called them) start to be caught when we were targeting livebait for both ’cuda and bottomfishing, but so did the redeye sardines that arrived in large shoals that boiled on the surface. This specific finding has been discussed at length among a number of us who fished the KZN coast from 1960 onwards and everyone concurs ... things have changed..

The art and practise of using livebait to target the predatory gamefish off this coastline saw the transformation of the old drum livebait container into a kind of livebait well. This was done either with an aerator or else the constant replacing of the water in the drum with a bucket to keep the livebait swimming happily. Nowadays of course most skiboats have a built-in livebait well that’s fed with a constant flow of sea water by means of a deckwash pump.

The net result is that today the anglers who target pelagic gamefish off South Africa’s coast predominantly use livebait as their bait of choice, especially when targeting ’cuda.

It’s great to have more baitfish in the area rather than less, but many of us wanted to know why these two specific species (mackerel and red eyes) suddenly appeared when they had never before been along the KZN coast, or certainly not in these numbers.

Dr Bruce Mann, senior scientist at ORI, is an offshore angler himself and he too had noticed this change in bait catches. During a number of coastal aerial surveys conducted during 2018 Bruce noticed more evidence of large shoals of baitfish than he had ever seen before. “Sometimes on quiet, windless days you could see patches of baitfish extending from Kosi to Port St Johns,” he said.

Mackerel like this never used to be caught off Durban but suddenly around 1990 they seemed to arrive in large numbers and have since become a well-used bait.

Bruce also wondered what had caused the change and subsequently contacted Dr Carl van der Lingen and Dr Stephen Lamberth who are both fishery scientists at Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment (DFFE).

A clear red-eye showing just below the surface.

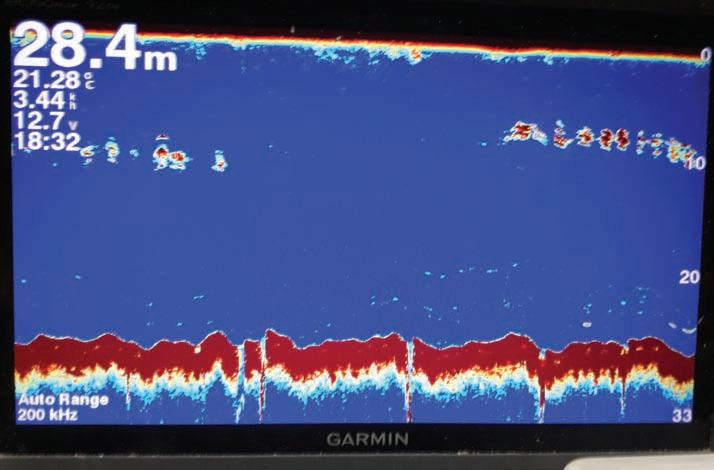

A showing clearly indicating the prescence of mackerel and maasbanker.

Photo: Jono Booysen

Following lengthy correspondence of a highly scientific nature with many scientific studies referenced, the general consensus was that there are three basic plausible reasons for the change in baitfish numbers and movement. 1) An increase of nutrient loading from rivers i.e. fertilizer runoff. This has stimulated phytoplankton growth with zooplankton following suit. As this is the main food source for filter-feeding fish like redeyes and mackerel, they have responded to the increased food availability. 2) That the high fishing pressure experienced over the period referred to, especially of pelagic gamefish such as ’cuda, Natal snoek/queen mackerel, garrick/leervis and demersal migrants such as dusky kob and geelbek, has reduced the number of predators in the area and there has been a resultant exponential growth of the bait population (known as “prey-release”by the scientists). 3) A general reduction in the pilchard (Natal sardine) biomass which results in less competition for available food, thus allowing other species in this niche to thrive.

Sadly, there are no clear answers to our original question, just theories, but we’ll take the positives where we get them, so let’s enjoy the access to the larger number of baitfish and pray that it lasts.