6 minute read

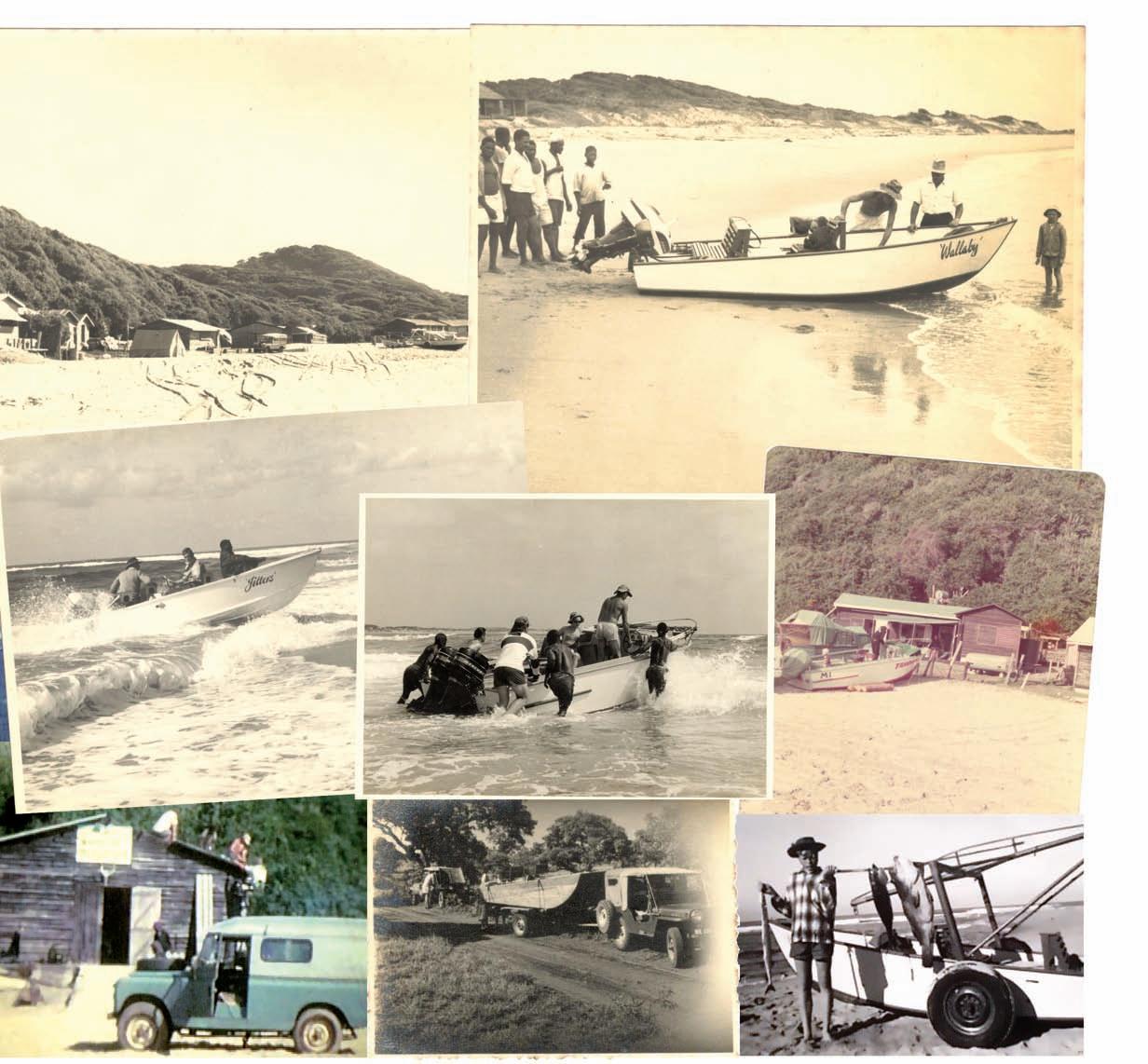

Crafting Boats

By Ian Coates

THE last time that I was at Mapelane was in 1995 while my dad, George, was still living at Monzi.

Advertisement

I feel the regulations outlawing any beach driving have killed Mapelane, where these days only skiboaters have realistic access to the beach and launch site.

My memories of those very early days when we had our clubhouse and shacks on the beach and then later in the bush overlooking the bay will always stay with me as the best days of our lives.

One thing I vividly recall is the way the skiboats changed over time. This article is an attempt by me to record the metamorphosis of the Mapelane skiboat from the early ’50s as I recall the progress through the years ... Around 1951 or 1952 the serious fishermen at Monzi, with help from some friends at St Lucia, decided to build themselves an enclosed deck, unsinkable boat, for fishing behind the surf back-line. They had seen similar boats going to see off Durban and wanted to do the same off Mapelane.

David Cork (who was operating the Estuary Hotel in the early ’50s) had previously worked for the Royal Navy in the UK as a marine architect. He had some basic designs, suitable for a small flat-bottomed skiff, based on the RN landing craft design. To keep it

light, and since aluminium was, at that stage, available, George Coates and some others including Walter van Rooyen, decided to build this 14ft mini landing craft, based on David’s design.

This new “ski-boat” resembled one of the already famous swamp boats that were used in the Everglades, USA. However, instead of an aero-engine and propeller, it had a raised transom that could accommodate a small outboard motor — very small by our standards today!

The largest motors available back then were Johnson and Evinrude 15hp, 18hp and 25hp which were definitely better than the old, nonenclosed “chugg-a-lugg” Seagull of some 2hp!

The original boat had a single 16hp motor, was tiller-steered and the motor was open to the sea from underneath, with obvious consequences in the surf.

The open motor design meant that even the slightest hint of a sea water splash would extinguish the ignition. That was quite a challenge when launching into the incoming surf, but still we went to sea. Our only other “back-up” was an anchor, rope and a pair of oars.

This flat-bottomed boat could plane quite easily with a 15hp motor but its acceleration was not sufficient to run ahead of a following, incoming surf breaker when coming ashore.

The consequence of that was that we did have some tumbles on the incoming ride, inevitably losing all our fish in the process and of course the fishing tackle too. The next “improvements”to the boat were tackle fixing brackets which were fitted to the deck, and several used 100 lb hessian sugar pockets, into which we would insert the catch before attempting to come ashore.

We also learned that we could use the anchor rope to tie up these sacks full of fish, and ditch them overboard immediately before coming ashore. The unladen boat was a lot less likely to flounder in the surf. The snchor rope would then be hauled in, by the shore-men. The fish catches were thus recovered almost every time, but not always.

On one occasion, just before we abandoned that early hull design for David Cork’s next “invention”, we had gone to sea at 5h00 and by 7h30 had caught over 1 000 lb of fish! We came ashore (using the technique mentioned above) and then turned around and went back to sea again, to catch a further 1 000 lb load before enjoying breakfast on shore at 09h00!

Those fish were carted off some 40km to Kwambonambi where we sold them to cover the cost of the petrol for the outboard motors.

David’s next idea was to take a standard dinghy design, cut it in half lengthwise, then re-join the two half-hulls back-toback to form a crude catamaran design.

The boat had suitably raised gunwales and a raised transom, so a 25hp Evinrude with an extended shaft was mounted on the transom. This set-up raised the motor well out of the way of any wayward splashes.

The increased deck area was very useful. Some of these early designs then also incorporated closed hatches for the fuel tanks and tackle, with one hatch reserved for caught fish. The hessian sacks were no longer needed!

However, we were still stuck with only 25hp motors. To get around that they mounted two motors and then linked the two tillers together so that tiller-steering the boat became reasonably possible. No-one had got around to installing steering gear at that stage.

The problem with this design was that when we were coming down the forward slope of the following wave, depending on which half-hull’s prow dug into the wave front, the boat would unexpectedly veer off to the side that had ploughed into the wave front and the boat was in danger of flipping which happened on a few occasions.

Consequently, it became very important to not come in at an angle to the wave. The skipper had to be sure to be heading exactly in line with the wave’s chosen direction, to avoid the dreaded “flip”!

Alternatively we had to only come ashore slowly, on the back of an incoming swell. Things got tricky if the next swell overtook the boat and swamped the motors!

Larger motors of 40- then 50- and then 65hp eventually became available, and these early boats then developed better manoeuvrability and acceleration. That improvement enabled them to outrun the following waves to safely get to shore.

About the same time that the original flat-bottomed swamp-boat design came about, the Preen brothers, neighbours of David Cork, built their-own widened deck surf skis. These craft did not have motorised assistance but were paddled out to sea quite successfully off Mapelane. The Preen brothers were often seen to catch their full quota of fish — as much as they could store on their small deck-area, in hessian sacks, of course.

The Preen’s home-built, wide-decked surf paddle-ski, was built on a wooden skeleton framework, covered with canvas (like a kayak), and then sealed with aircraft dope. Rips or tears were, of course, the bane of their lives.

This development led to the debate about catamaran versus deep-V design, with refined versions of both of these now being standard design choices some 70 years later.

Boat-builders like the Yelds, Ace-craft, Tomcat and others then began to flourish.

Times have certainly changed since then. Larger boats, fancy launching trailers, high-powered (and now 4-stroke) motors, huge 4x4 vehicles and tractors needed to tow and launch these very much larger boats, have all changed the face of the original intrepid ski-boating fraternity of Mapelane, Vidal, Sodwana and places further to the north in Moçambique. I’m glad we have memories of how it all began.