Poetry in the Galleries

Thursday, September 29, 2022

Thursday, September 29, 2022

This digital booklet is an online recording of “Poetry in the Galleries,” a reading of original poetry inspired by art on view at Sheldon Museum of Art. The program, held at the museum on September 29, 2022, featured graduate students in a poetry writing seminar that I taught during the fall semester of 2022.

One of the rewarding practices available to poets is the opportunity to be in creative dialogue with the work of visual artists who trade in the most fundamental conception of the image—as a function of representation, abstraction, or psychological sublimation. The poet, working with language, is constantly faced with the limitations and possibilities inherent in this “conversation.”

As a practice, I build into my poetry writing seminars the opportunity for poets to explore the possibilities inherent in this dialogue. For many years, Sheldon’s rich exhibitions have provided me with an accessible entry into this process. I have relished walking through the light-flooded galleries at Sheldon to discover exciting pathways to my own work. I have watched this same pleasure lift the writing of my students over the years and this booklet offers irrefutable evidence of how powerful the dialogue between art and poetry can be.

The participating poets are a part of Nebraska’s Graduate Creative Writing Program, which attracts some of the most gifted writers emerging today. They hail from across the United States and around the world, bringing rich experiences and passions to this community of artists. Their poems are moving works of great risk and beauty. I trust you will share my admiration and enthusiasm for the poetry that exists in this booklet, even as you get to see some of the splendid work that is on exhibit at Sheldon.

Kwame Dawes, PhD George W. Holmes University Professor of EnglishGlenna

Luschei Editor of Prairie Schooner Editor, American Life in PoetryThe poems are published with the permission of the authors. All rights remain with the authors. No part of the poems may be reproduced without prior permission from the authors. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission from Sheldon Museum of Art.

Chicago, IL 1940–New York City, NY 2007

Wishing for the Farm Oil and canvas on wood 1991

Sheldon Museum of Art University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Gift of the Hormel Harris Foundation, Rhonda Seacrest, Donna Woods, and funds from the Olga N. Sheldon Acquisition Trust, and the Charles W. Rain and Charlotte Rain Koch Gallery Fund U-6778.2018

When we have the farm it will look, from above, like no other country; there will be holes blown in the hills around

Us, or bored by some enormous worm—impossible to tell how deep the tunnels go; bottomless fissures will cross

The land where tectonic movement will at last have been arrested— we will build bridges over the depths; at Three

Corners, red ochre flats and our haygrass fields will meet verdant hill country fed by the dark Mistwater—undulating

In valleys where globules like spilled oil mark the worm’s ancient path, tracing from the river to its burrows—the glow fence kept

Up to light the way; the washed-out road in the hollow near Yellow Hill will mark a boundary around where the old world was:

The interior where no road now cuts through, only runs around the perimeter of the island, until it winds in on itself

At the farm, where we will both have come in to wash up from the day’s work, leaning over the sink—together—to scrub our hands

Before dinner—in the halflight before the children get home, when the house is still—like we used to do before we had the farm.

Newburgh, NY 1825–Bridge of Allan, Scotland 1894

The Farmhouse

Oil on canvas, circa 1894

Sheldon Museum of Art

Nebraska Art Association

Given in loving memory of Lorraine LeMar Rohman by Melanie R. Waites, Carl P. Rohman II, Stephen L. Rohman and G. Peter D. Rohman N-674.1985

It all blurs together, doesn’t it? There was that stillborn puppy who left the world wide-eyed, her body warm & open.

That last winter of frostbitten crops we marked with a silence as dense as the graying weeds of the neighboring, abandoned farms.

Summers are dust cloud after dust cloud, & you always wait until I’m asleep to shower off the plains.

I think of the puppy often in the spring & how one turn of wind changes the crop formation & all of our animals’ dispositions.

Or maybe the baby just knew better.

She knew, like the white winter wheat, to wait until the world is more hospitable to begin because although patience hangs in the air like death, the sound of solitude is less forgiving.

Laura Knight

Long Eaton, England 1877–London, England 1970

Dressing Room No. 1

Aquatint, 1923

Sheldon Museum of Art University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Anna R. and Frank M. Hall Charitable Trust

H-1391.1970

The mistress insists on watching the seamstress pin and sew this underskirt.

It isn’t that thrilling. The seamstress is not the type to hold pins in her lips, draw attention to imagined kisses. She holds her needle so its delicate weave isn’t visible. Her mistress will see the final drape of the underskirt when it falls from her hips— secure at the waist— and before she’s layered the more embellished cover.

Sharp and close and hidden.

Perhaps, for the mistress, it doesn’t matter the shape of the dress covering her curved lines.

Good tailoring makes fabric seem of a piece.

For the mistress, it is the making.

Topeka, KS 1899–Nashville, TN 1979

Window Cleaning

Oil on canvas, 1935

Sheldon Museum of Art

Nebraska Art Association Collection

N-40.1936

At the gym today, Spotify suggested a song you made me fall in love with. Divenire. To become.

I should’ve pressed next but the treadmill was going too fast, or perhaps, I wanted to re-live the moments that have become accompaniments to that tune:

The occasional rides from Manhattan to Jersey, your car filled with nothing but Ludovico’s piano. Slow then fast. Intense then gentle. Gripping all through.

How you drummed the steering wheel to each note when the traffic slowed down. How I ran my fingers through your afro when the lights turned red. Why did you let me?

How you smiled when I reached for the dashboard to press replay? Why didn’t you stop me?

The occasional photoshoot on your fire escape. How you cleaned the camera lens like you didn’t want to miss a strand of my hair. How you turned up Divenire as I gazed at the leafy horizon. How you lay on the living room floor, pointing camera at me through the open window. How I posed for your perfect shots until my feet ached. Smile, you said. Okay, I said. Beautiful, you said. Stop it, I said.

You knew we were not becoming anything, didn’t you? You knew the next morning you’d wait for me to leave & send that text saying you couldn’t do it, didn’t you?

I was at the gym, running like a lunatic to forget but an app squeezed you in with a song you called ours. What do you think that made me become?

I still love windows, except now I want to walk down the steps without posing on your fire escape.

Rochester, NY 1912–Los Angeles, CA 1985

Subway Drillers

Wood engraving, 1937

Sheldon Museum of Art

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Allocation of the U.S. Government, Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration

WPA-318.1943

New York, NY 1907–Walnut Creek, CA 2002

Paving

Lithograph, 1937

Sheldon Museum of Art

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Allocation of the U.S. Government, Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration

WPA-308.1943

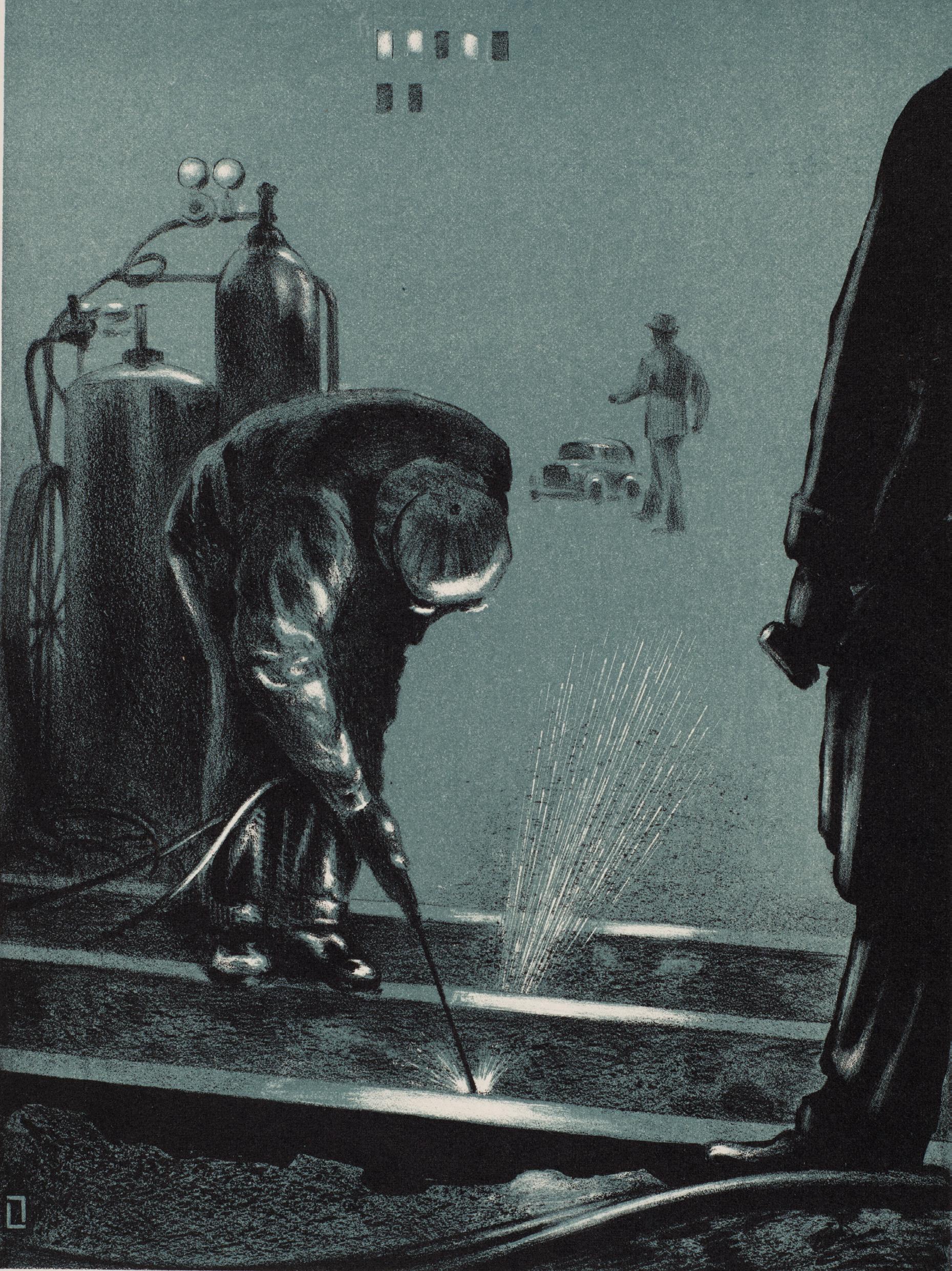

Ludvinovka, Ukraine 1892–South Orange, NJ 1973

Night Repairs

Color lithograph, 1939

Sheldon Museum of Art

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Allocation of the U.S. Government, Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration

WPA-306.1943

Labor is always bent over their work, consumed by the task at hand, those Big. Strong. Hands. Face down, ass up, they don’t even notice us gawking.

Or maybe they do?

Workers hardly need to remind us that they’re always pounding, drilling deep, just wrecking everything they touch.

Where there’s work there’s smoke, and where there’s smoke there’s heat. Fire.

Dare I say it, Sparks.

Can you blame me for seeing this as pornographic? Marx says when you have to sell everything, eventually you sell yourself.

So workers of the world, unite on the dance floor and sell what your mamma gave you.

Because honey,

We are buying.

IAN DAVIS

born Indianapolis, IN 1972

Files

Acrylic on paper, 2007

Sheldon Museum of Art Sheldon Art Association

Gift of Robert and Victoria Northrup

S-879.2012

As for this work, by a painter born in Indianapolis, painted in the year 2007, at around the time I left Indiana for good—I don’t like it much. At least, I don’t like it more than I liked Indiana.

Like that place, it seems to lend itself a bit too easily to that most brutally obvious way of seeing: allegory. Here, we have men in business attire, gathered in deferent postures around a line of six industrial machines, and taking notes— capitalism’s fetishistic excess, et cetera.

And yet, like the miles of corn that threatened to swallow the dying steel town I grew up in, framing it in bounty so absolute it became poverty, it is not completely without its small charms. Notice, for example, the scattershot ribbons of pink lacing and unlacing the walls, the floor, the men themselves, as if to say not even allegory, nor the sober silence of that most sober of states can be so serious as to preempt light’s play.

But then, there is also the sadness of the machines, which almost seem to sag, elephantine, under the weight of their silence.

I worked once with machines not unlike these, which had waited long decades in the quiet half-dark of a warehouse floor—for years, I lifted them gently by crane, or scooped them up in the tines of a forklift, and carried them, carefully, down the machine shop floor to the scrap metal bins, and to my station where, with just as much care, I’d open them up and take them apart.

Indiana Poem Nathaniel NelsonSwitched on, these machines would hush together twinned electrodes with such gentleness it resembled a kiss, and sparks would fall to dance on the oil-stained floor. Left dormant, as these had been for years, they reminded me of nothing so much as giant, unbeating hearts, whose chambers were rooms for cobwebs, grease, and stale air, and maybe the air’s slightest breath, which lifted a cobweb, then released it, every ten minutes or so, for years upon years.

It is perhaps then no small thing that Ian Davis, child of Indianapolis, would paint these six achingly quiet machines in postures of holiness. Almost to a one, the men of midwestern steel towns know that these machines— turbines and furnaces, slide gates, ladle cars—even now falling silent, are their culture’s holiest relics, and the last escapes they’ve kept shored up between themselves and endless corn, and the whispered dialogue between them, asking always “ what now? ” and “ why here? ”

Towering above themselves, they built a heart, made perfect in that when the day’s work was done, it could be switched off.

born Plainfield, NJ 1976

Cotton Bowl

Digital chromogenic print, 2011

Sheldon Museum of Art

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Olga N. Sheldon Acquisition Trust

U-6506.2015

I touch the turf for the first time. Dad kneels down to show me. Digs his fingers into the torn up rubber. Says, look, lets the pieces roll around in my hand. He throws me a touchdown. Carries me on his back. Singing fight songs as I bounce in his arms. I can feel the drums of his hands as they thud in my feet, Go. Big. Red. Da-da-da-da. Go. Big. Red. da-da-da-da. Go. Big. Red. da-da-da-da-dum. I feel the thrum of my history. A repetitive beat. I feel it weaving, planting itself, in my identity.

College football is my identity is spectacle is prayers for the boys to bring home a win is a line of scrimmage is a group of bodies that I watch is standing in the stadium where I yell break his legs! as an adult as a joke but actually mean hit him really hard not so hard but maybe let him see the stars for a second make his ears ring and hear the song of our victory of our strength in the crowd.

The crowd is a violence is my friends is crying out to God is punching the sky is beating their wives is shaping their lives is worshipping the image. The image is a body bent to the ground. The ground is accumulating like the hits to the head on the O-line slamming helmet into helmet for the days and the years and the life. This is a land of memory loss. CTE. A movie with Will Smith that I watch to feel good feel sorry. Sorry’s in the mouths of the coaches, statements for ESPN.

My favorite sport is a harvest is unpaid labor is Nebraskan is the local economy is my consumption my catharsis my communion is what brings me together with my family on Saturdays with chips and salsa around the TV is contact with the dirt is in touch with my roots is history is present is how I avoid my own pain. I just keep watching. It goes on. Another season.

My Dad takes me to the Cotton Bowl. I dye my hair red. I don’t have to pay a dime. We drive down to Texas. Hike up the stands. Cheer and laugh and eat nachos

and I love this memory. The feeling of being special, like inside my chest is one of those balloons that gets released by the fans after the first Husker touchdown. I keep wanting to feel it. Stuff of history.

I am formed by what I want to watch and what I want to avoid. A thing of the past is not a thing of the past if I can’t stop watching it.

No more apologies. To watch is to play the game.

I want to plant sunflowers in my memories. I want to talk to my dad more. Form traditions that don’t take pleasure in watching over Black bodies.

I could tell him my love for him is scared is fraught is digging into a field and watching the dirt fall through my hands. I could tell him

I don’t know what to look at. That I want to learn to love what I look at. That I don’t know how to look him in the eye. That I’m done releasing my pain into other people’s bodies. Screaming it into a screen. Done talking around our lives by rehashing the game. No more side-stepping. This place has shaped me. I’ve been shaping it. Now, I have to live and work in it.

LISA SANDITZ

born St. Louis, MO 1973

Pearl Farm II

Acrylic on canvas, 2007

Sheldon Museum of Art

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Olga N. Sheldon Acquisition Trust

U-5493.2007

every goddamn thing is a glimmering mirror of divinity

Penny Molessoheaven is a city, glossy pink like inside cheek flesh. we’ll shuck the gates. out gushes everything clean, pearly iridescent pus pooling like motor oil in our dirty little sanctuary.

everything swallowed the crystalline city’s bleeding nucleus and spit up utopia in chunks. plastic skin, bubble wrap frisson, piss sluice streaming service in DIY eden.

the angels fell to earth. ancient oysters cradled their sweat. microscopic tektites, little scrying orbs. precious as candy. precious as cell phones.

once the irritant has been implanted it can take years to shape into a crucifix, a star, an antler, a pair of wings. i too formed a glistening shell around the biotoxic boy inside me, miserable and thriving.

the promise of eternity gutted this place, so we saw the glitter smog sunsets and named them gorgeous, borderless. we sink into an artificial lake, sweet endocrine water brimming with futures, contagious shell-cracking salvation.

ROCKWELL KENT

Tarrytown Heights, NY 1882–Plattsburgh, NY 1971

Headlands, Monhegan

Oil on canvas, 1909

Sheldon Museum of Art

Nebraska Art Association

Nelle Cochrane Woods Memorial N-244.1971

The day opens like a rose on fire; waves crashing over jagged rocks. I taste salt on the wind, draw the moment in like a kiss, from lips to lungs. My blood-

stream rushes bright red and vital, and it is as if I were seventeen again. At seventeen

I did not know the sea is slowly filling with poison from leaking nuclear bombs.

I had not yet seen the amber glow of streetlights on wet railroad tracks after trying to drive fast enough to leave this world behind.

I had not yet heard the call of death, crashing like waves against my skull, or felt the gray plastic chair at my back in the psych ward, tea going cold in my hands as I begged to go home.

At seventeen I did not know that one day the sea might take us back, waves crashing over our cities and our bodies until we are nothing but rubble and bone at the bottom of the earth.

It is as if I am seventeen again and my bones still belong to me, and they don’t ache

or crack as I start running, running, toward the call of life. I kick up the pale sand of everything that has gone

before me. I run until the sea engulfs me like a warm, new womb, glittering like a future worth staying for.

CHRISTINA FERNANDEZ

born Los Angeles, CA 1965

Lavanderia #5 [ Laundromat #5 ]

Archival pigment print, 2002-2003, printed 2022

Sheldon Museum of Art University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Anna R. and Frank M. Hall Charitable Trust

H-3128.2022

The discomfort of it, inside the laundromat at the corner of Broadway & Griffin. I spent so much time, looking at the clothes turn & turn. We always waited for the loads to pile, before my father would load the shopping cart kept in the outdoor parking lot in the back of the duplex to take the dirtiness of the past week to clean. He claims that he can wash all our clothes until he dies: as long as I’m alive, you don’t have to labor. We’d all go together.

I was always allowed one drink. I chose Coke, always. The coins go down the slot, clicking things into place, revealing the cold can, ready to be cracked open. I called my parents today, complaining that what I’ve always wanted is hard. My father does what he does best, tells me about a wise phrase along the lines of cách con vượt qua điều khó khăn mới là điều quan trọng. My mother chimes in, I don’t know anything, & I made it, so can you.

I would like to be back here: 2826 N. Broadway, Lincoln Heights, CA 90031, sitting on the orange bench with them, as the washing machines wring out our clothes.

Ber Anena

Ber Anena is a first-year Ph.D. student of Creative Writing at UNL. A Ugandan-born writer, editor, and performer, she graduated from Columbia University’s MFA Writing program in 2021. Anena’s debut poetry collection, A Nation in Labor , was the winner of the Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in Africa, in 2018.

Caroliena Cabada

Caroliena Cabada is a second-year Ph.D. student in Creative Writing at UNL. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing and Environment at Iowa State University, where she was the 2018-2019 Pearl Hogrefe Fellow in Creative Writing. Her work has been published in Pleiades , perhappened mag , JMWW , and elsewhere.

Syble Heffernan

Syble is a first-year M.A. student in Creative Writing with a concentration in Poetry. Her research interests include Women and Gender Studies, queer theory, mental health and trauma, and creative writing as an instrument of collective healing and community development. Her work has appeared in Gnashing Teeth and Blanket Sea Press , among others.

Ian Maxton

Ian Maxton is a communist writer and critic. He is a second-year doctoral student in Creative Writing with a focus on experimental fiction and the novel. His work has appeared in Always Crashing , Protean , and Cease, Cows

Penny Molesso

Penny Molesso is a transmedia artist from Arkansas. They received their BFA at the University of Arkansas and are currently a third-year MFA student in Studio Art at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Nathaniel Nelson

Nathaniel Nelson is a first-year Creative Writing Ph.D. student with a concentration in Poetry. Their poems have appeared in The Southern Review and Birmingham Poetry Review

Alina Nguyen

Alina Nguyen is a first-year Ph.D. student in Poetry from Los Angeles, CA. At the California State University-Long Beach, she was awarded the Gerald Locklin Writing Prize where she earned her M.F.A. She is the author of the risograph-printed chapbook, Before There Were More Ghosts , from Tomorrow Today.

Caleb Petersen

Caleb Petersen is a resident of Lincoln, Nebraska, currently pursuing a Ph.D. in English from the University of NebraskaLincoln, with a specialization in Poetry. He has an MA in English - Creative Writing from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and a BA in Theology from Colorado Christian University.

Kimberly Reyes

Kimberly Reyes is the author of the upcoming poetry collection vanishing point . (Omnidawn 2023). Her other books include Running to Stand Still (Omnidawn 2019) and Warning Coloration (dancing girl press 2018). Her nonfiction book of essays, Life During Wartime (Fourteen Hills 2019) won the 2018 Michael Rubin Book Award. Kimberly is a first-year Ph.D. student in Creative Writing.

Shannon Valkr

Shannon Valkr is a first-year M.A. student specializing in Creative Writing - Poetry. She holds degrees in Chemistry and English from UNL.