Reigning Queens Modern and Contemporary Representations of Women, Power, and Religion

January–May 2023

Learning Guide

January–May 2023

Learning Guide

January–May 2023

Building on the adjoining exhibition, Beyond Eve and Mary , this exhibition examines twentieth- and twenty-first-century representations of women in art. From temptresses and monarchs to advocates and activists, Reigning Queens invites viewers to consider the ways artists have explored and challenged gender stereotypes. The included works center the bodies—covered and uncovered—of both famous and anonymous women, conveying messages of power and protest in different ways.

Exhibition support is provided by Hixson-Lied Endowment, Nebraska Arts Council and Nebraska Cultural Endowment.Pittsburgh, PA 1928–New York, NY 1987

Reigning Queens (Queen Elizabeth)

Screenprint on Lenox Museum Board, 1985

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Gift of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

U-6374.2013

Reigning Queens (Queen Elizabeth)

Created as a part of a series featuring the four queens in power in 1985, Andy Warhol based this image of Queen Elizabeth II on an official photograph released for her Silver Jubilee in 1977. Warhol’s work is the only artist’s portrait that Elizabeth did not sit for. The longest reigning woman monarch in history, she used her intentionally constructed royal image as a weapon against what historian Andrew Graham-Dixon describes as “the historic chauvinist preconception that queens must be weaker than kings.”

Cleveland, OH 1926–New York, NY 2009

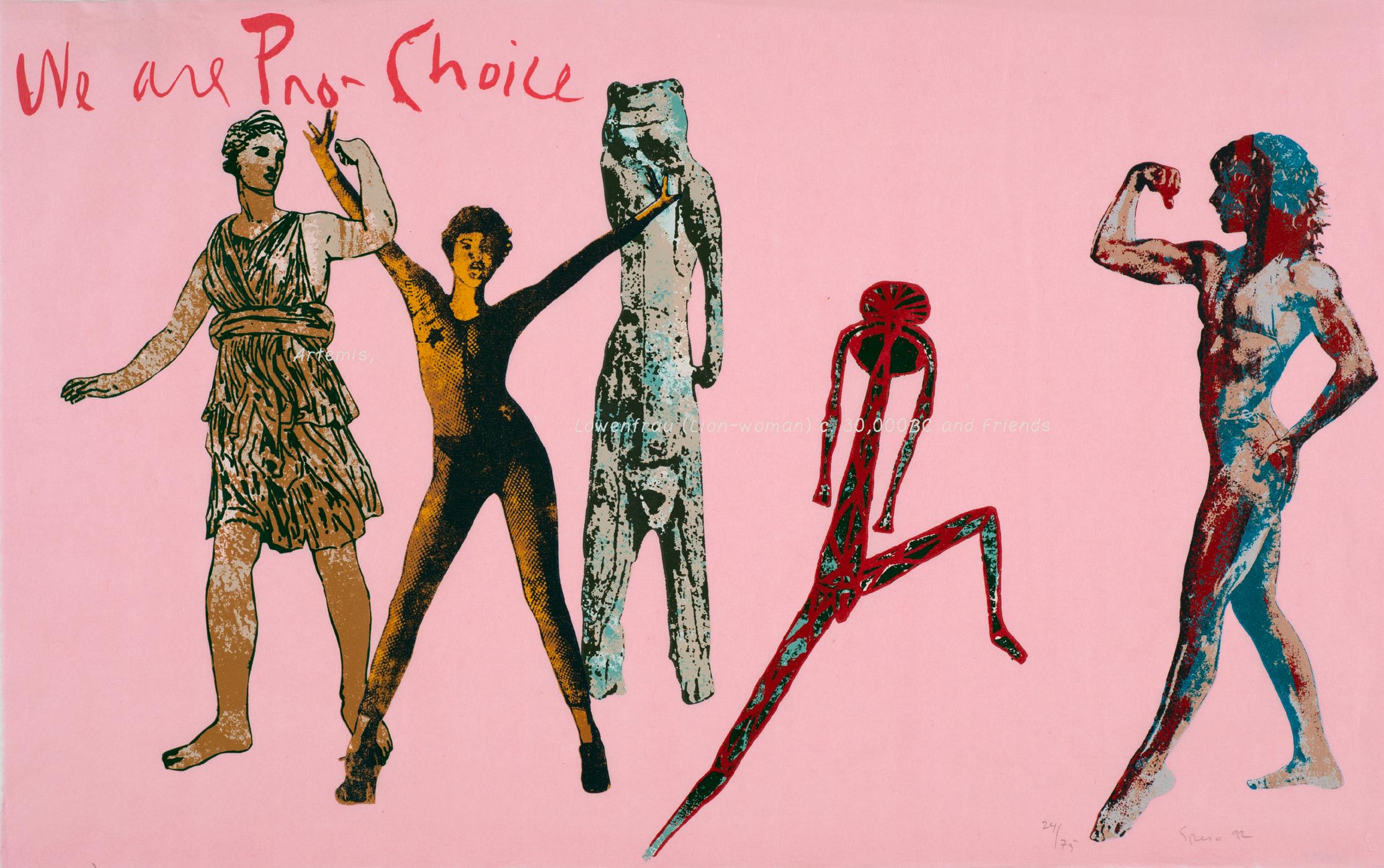

We are Pro-Choice Silkscreen, 1992

University of Nebraska–Lincoln University Collection

U-4697.1996

We are Pro-Choice

In this work, artist and activist Nancy Spero juxtaposes women from different cultures and time periods—all in control of their own bodies and, through the title, proclaiming their right to choose. The name “Artemis,” included in the white text written across the work, refers to the figure on the left: the ancient Greek goddess of childbirth, shown reaching for her arrow. The name “Löwenfrau (Lion Woman)” refers to the central figure: a small statuette carved from a mammoth tusk approximately 40,000 years ago that was significantly damaged by a geologist who hastily unearthed it in a cave in southwest Germany in 1939. While 220 pieces of the object were reassembled in 1988, an estimated thirty percent of the body is missing. Disputes arose over the gender of the figure, which was originally called “Lion Man” by archaeologists, and the piece became an icon of the women’s movement in the late 1980s.

GHADA AMER

born Cairo, Egypt 1963

REZA FARKHONDEH

born Iran 1963

Love Me

Lithograph with hand-sewn elements, 2006

Published by Landfall Press, Chicago

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Olga N. Sheldon Acquisition Trust

U-6671.2017

Love Me

For me it is as hard to be a sleeping beauty as it is to be a sex symbol; both of them are useful for women in order to gain power and freedom.

Beginning in 1992, Ghada Amer began incorporating well-known female characters from animated Disney films—such as Cinderella, Snow White, Tinkerbell, and, as in this piece, Princess Aurora (aka Sleeping Beauty)—into her work. With only eighteen spoken lines and approximately eighteen minutes of screentime in the 1959 Disney movie, Sleeping Beauty speaks less than any other speaking main character in a feature-length animated Disney film. Her image is presented here against a floral backdrop made by Amer’s collaborator, Reza Farkhondeh, and the words “LOVE ME” embroidered onto the paper by Amer.

JUDITH SHEA

born Philadelphia, PA 1948

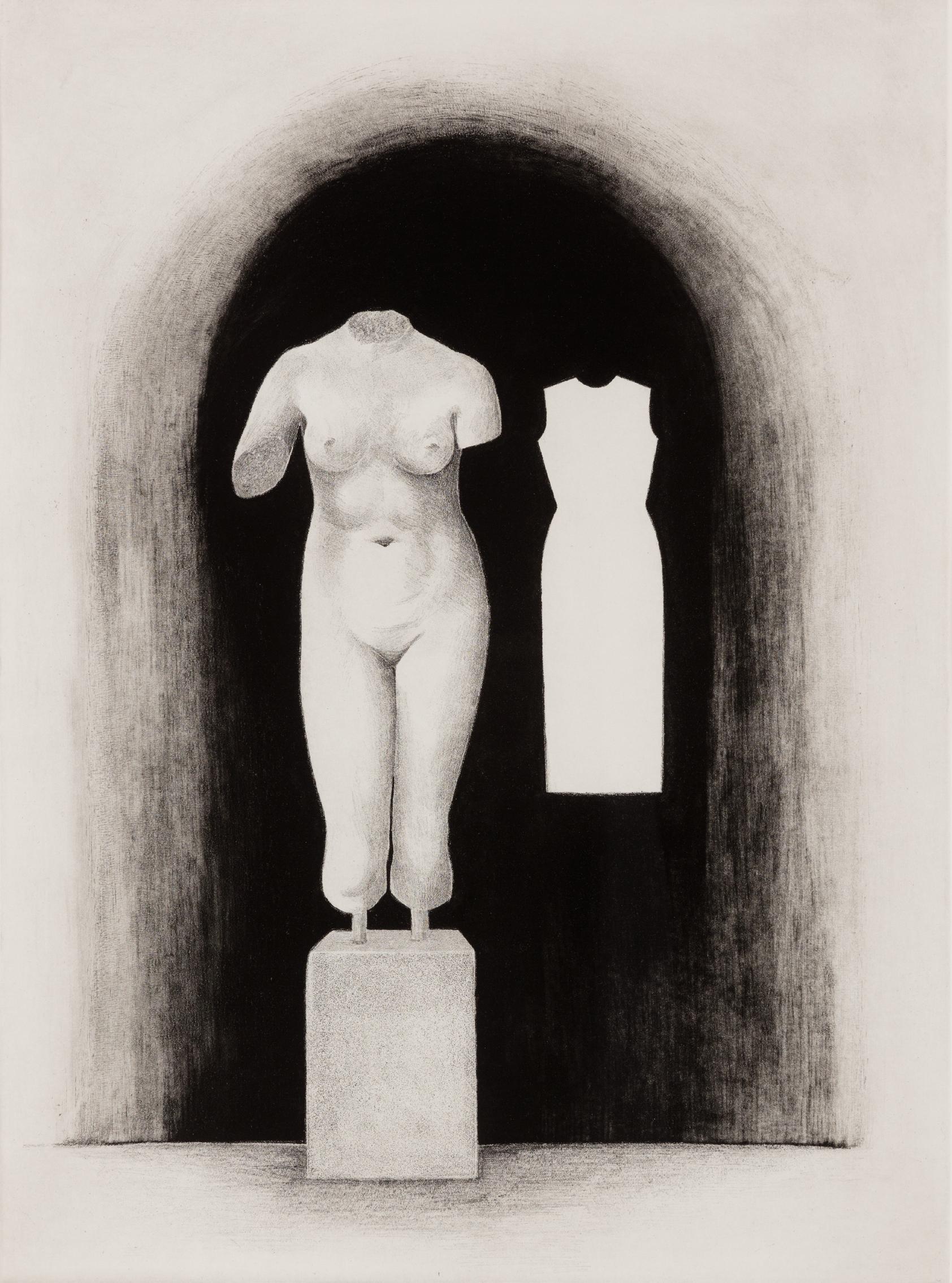

Venus

Soft-ground etching, 1990

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Anna R. and Frank M. Hall Charitable Trust

H-2957.1991

This print is after the eponymous sculpture

Judith Shea created in 1989 of a white castmarble torso on a stone base, behind which a white organza sheath dress was pinned to the wall. The nude sculpture is based on a small figure of Aphrodite, the ancient Greek goddess of sexual love and beauty, identified as Venus by the Romans. The form-fitting sleeveless garment, which has been closely associated with Shea since she left the fashion industry to create art in the late 1970s, stands in for a more contemporary female body that is present through its absence and chastely clad.

Judith Shea’s sculpture Shield is on view in the Great Hall.

JUDITH SHEA

Venus

JUDITH SHEA

Venus

Omaha, NE 1970–Omaha, NE 2013

Girl (#8) , from the Black as Pitch, Hot as Hell series Acrylic and latex paint on carved plywood, 2006

Sheldon Art Association

Gift of Kop Ramsey in memory of her sister, Della Kopperud Stover S-900.2013

Rotterdam, Netherlands 1904–East Hampton, NY 1997

Woman

Charcoal and oil on paper, 1954

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Anna R. and Frank M. Hall Charitable Trust

H-362.1955

With an exaggerated form and angular features, Willem de Kooning’s Woman embodies the tension between a recognizable female figure and the energetic mark-making of action painting. Some interpret the artist’s gestural slashes of paint as aggressive and the way in which he depicted the female nude as menacing or violent. To these readings de Kooning once famously asserted, “Beauty becomes petulant to me. I like the grotesque. It’s more joyous.”

WILLEM DE KOONING

Woman

WILLEM DE KOONING

Woman

born Marrakesh, Morocco 1956

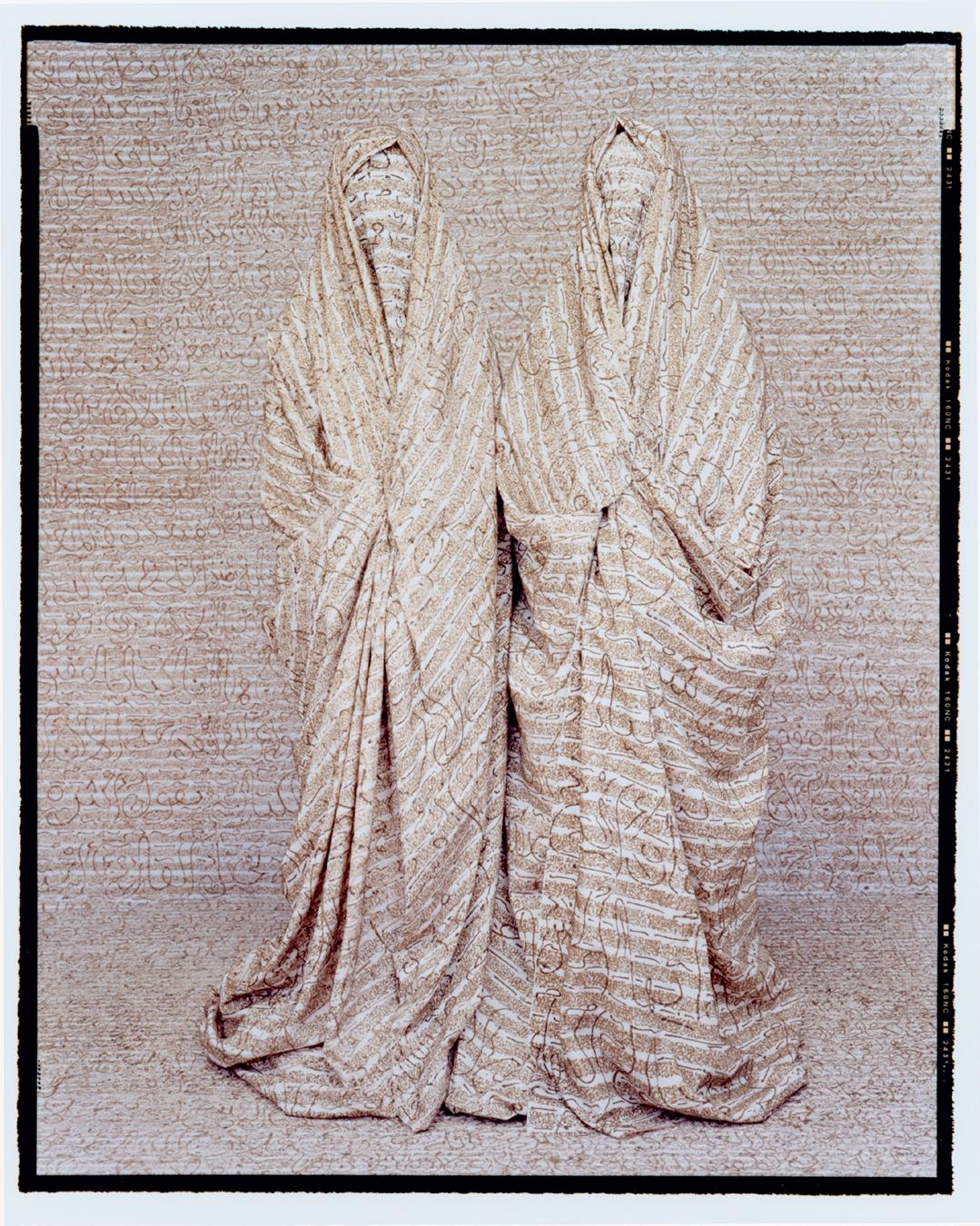

Les Femme du Maroc, #25, A & B [ The Women of Morocco, #25, A & B ]

Chromogenic prints mounted on aluminum, 2006

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Robert E. Schweser and Fern Beardsley Schweser Acquisition Fund, through the University of Nebraska Foundation

U-5612.1–2.2011

At least among those I have encountered, Arab women are having trouble with both worlds, Arab and Western. The Orientalist narrative is being projected on them from both directions. They are either weak and in need of rescue or jezebels who need to be brought under control. In my photographs, I try to clear away these projections so that—here is my hope—they can be seen as powerful presences in their own right.

—Lalla Essaydi, from an interview inBy fully cloaking the subjects of her largescale diptychs, Lalla Essaydi disrupts the nineteenth-century Orientalist tradition of overtly sexualizing Arab women through gratuitous nudity. She has covered the fabric that veils these two women and the photographs’ backdrop with Arabic calligraphy using henna, a pigment customarily applied to females to celebrate rites of passage. This painstaking process takes Essaydi more than six months to complete.

Les Femme du Maroc, #25, A & B [ The Women of Morocco, #25, A & B ]

Les Femme du Maroc, #25, A & B [ The Women of Morocco, #25, A & B ]

born Rome, Italy 1938

Untitled (Woman and Store Window)

Gelatin silver print, 1963

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Gift of the artist

U-482.1964

VIVIAN MAIER

New York, NY 1926–Chicago, IL 2009

Untitled (Nun)

Gelatin silver print, 1959, printed 2013

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Purchased with funds from the Dr. Richard S. Hay Memorial U-6316.2013

Portland, OR 1883–San Francisco, CA 1976

Adam and Eve (The Supplicant)

Platinum print, 1912, printed later University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Anna R. and Frank M. Hall Charitable Trust H-1168.1966

JOEL-PETER WITKIN

born New York, NY 1939

The Wife of Cain

Gelatin silver print, 1981

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Anna R. and Frank M. Hall Charitable Trust

H-2600.1983

Joel-Peter Witkin describes his carefully structured tableaux as “sacred work,” often deriving from biblical subjects or his prayers. The subject of this photograph, the wife of the biblical figure Cain, is taken from the Book of Genesis. The unnamed, pregnant woman is the daughter of Eve and therefore Cain’s own sister. As is his practice, Witkin scratched out elements and distressed the photo negative, heightening the composition’s theatricality to produce what he has described as “profound emotional dichotomies within the viewer.”

The Wife of Cain

The Wife of Cain

Hobita, Romania 1876–Paris, France 1957

Princesse X

Marble with Caen limestone base, 1909–1916

University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Gift of Mrs. Olga N. Sheldon in memory of Adams Bromley Sheldon U-418.1963

Princesse X has its origins in an earlier sculpture depicting the notoriously vain Princess Marie Murat Bonaparte of France (1882–1962), who allegedly always carried a mirror with her. Enchanted by the graceful way she studied her own reflection, Brancusi initially made a marble portrait of her gazing downward. As he reworked his depiction of the princess over a seven-year period, Brancusi dramatically reduced her anatomical structure to a rather phallic appearance. The featureless face, elongated neck, and rounded breasts of Sheldon’s version have an almost industrial, streamlined precision, even though the work was carved by hand.