Acknowledgement

Foremost, praises to God, the Almighty, for the blessing throughout the whole research process.

Feeling grateful that I had finished my Interior Design Research about In-between Space in Wellbeing Centre based on practice in Design Studio Course.

Special thank you to my Mother who always supports me from Indonesia and my friends here in Melbourne. Thank you for the outmost support from the tutor, Dr. Roger Kemp along the process of the research and the design process in the Interior Design Studio Course.

To my team member of Group 1, thank you for the great collaboration and making the project an interesting first semester experience in Master of Interior Design.

I hope this research can be a useful contribution to the design community.

Grigoriou, Elina., and Richard. Francis. Wellbeing in Interiors : Philosophy, Design and Value in Practice. Milton: RIBA Publications, 2019 XII-XIII.

“ wellbeing: it’s a beauty, it’s experience

Abstract

The research investigated the creative strategies for creating an Interior Design that can support the wellness and well-being of the occupants. It focused on analyzing the ‘in-between’ elements in the design and the experience that affected user perception. The research was conducted through a literature review about the spatial qualities to support wellness and wellbeing in a spatial design. Research also happened through the design process of ‘Shepparton Wellbeing Centre – Nutritious Hub’ from exploration study with physical model making, the final visualization stage, and the feedback from the design community. The design processes were documented and then written as a reflection summary to be analysed further.

The result showed that several aspects are crucial in the making of design supporting wellness and wellbeing. It had to be mindful of user positive experience. In the case of the design of Shepparton Nutritious Hub, the goal was to create a healing atmosphere considering affordance and inclusivity as an approach to supporting wellness and wellbeing for the user.

Within the design process, the research found interesting atmosphere generators and the role of experience within ‘in-between’ space to achieve the goal. The tangible elements such as layout and architectural form were the trigger of the inclusive experience. Moreover, the quality of material, texture, shape, and lighting were the generator of the atmosphere. Both affected the users in the space which determine the happening of atmosphere inclusivity.

For the designer, there was a limitation in this research as it was strongly based on visual communication. It had not happened within a real physical experience to be experienced by the user. Further research suggested covering the process of making in the physical environment to get a hint of user experience.

Keywords:

Wellness and Wellbeing, Interior Design, Atmosphere Inclusivity, In-between Space

Introduction

BACKGROUND

World Health Organization1 stated that a global outbreak of the Corona virus had sparked a considerable amount of fear, worry, and concern in the larger population as well as certain groups. It affected public mental wellbeing. It also changed several aspects such as awareness of physical and mental health. The World Economic Forum2 released an article from Ipsos Research suggesting that COVID-19 made people more health-conscious and willing to change their lifestyles to stay well. The research also explained that wellness was not only about medical fitness but also affected by the awareness of mental health, more ageing population, more development of technology, health, and environmental condition.

Prior to the literature studies, the transition area of the built environment might have a huge impact on creating the experience of the user. It was called ‘in-between’ space. Therefore, the research question were:

• How can interior design support wellness and wellbeing to improve public health?

• How can designers shape the user experience through tangible aspects to ensure a positive experience and promote wellbeing?

• To what extent can the experience happening within the ‘in-between’ space promote wellness and wellbeing?

METHOD

1World Health Organisation. Mental Health and Covid-19. Last modified 2022, https://www. who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19/mental-healthand-covid-19

2Broom, Douglass, “6 trends that define the future of health and wellness”, The World Economic Forum https://www.weforum.org/ agenda/2022/02/megatrends-future-health-wellness-covid19/

Following on this issue, it was important for the designer to take this chance to improve the built environment performance. I suggested that the built environment, especially interior design, which is the closest design field to human occupation, can help to facilitate wellbeing and wellness. Therefore, this research aimed to investigate the relationship between interior design with the happening of wellness and the wellbeing of the user.

PURPOSE

The research was conducted through creative practice. It is intended to search for strategies to create an Interior Design that can support the wellness and well-being of the occupants. It investigated to look for the quality’s environment and the tangible and intangible element within the design.

The research was conducted through 3 stages: literature review, exploration stage, and design stage. The research was conducted through design practice within a team of four students including me as the writer.

The research stages consist of:

1. The literature review is about the fundamental understanding of wellness and wellbeing in a built environment.

2. The exploration stage consists of 4 tasks including investigation of the case studies, drawing institutional moment, inclusivity aspect in design, and affordance and atmosphere exploration through model making.

3. The last stage was the final design process of the Shepparton Wellbeing Centre named ‘Shepparton Nutritious Hub’. It consists of an exploration program and services, site analyses, the final visualisation image, and feedback from the design community. The design processes were documented and then written as a reflection summary to be analysed further.

References:

Space, Wellness, and Wellbeing

Introduction

Much contemporary literature identifies a connection between the design of Healthcare with the promotion of wellbeing. Most interestingly, a statement by Terry Montgomery in Architectural Design in 20171 highlights the term ‘in-between’ space. He identified ‘in-between’ space as a crucial design consideration for patient experience in clinical environments. This led the firm to have a new design approach, enhancing patient wellbeing through emphasising the connection between inside-outside and public-private, the ‘in-between’ space.

‘In-between’ spaces are discussed by Kearns, Neuwelt, and Eggleton2 as a negotiation for a patient within the ‘under-examined’ areas such as the reception hall and waiting rooms. These spaces had a remarkable impact on patient experience due to the dealing activity between person’s needs with the institution protocol. Kearns, Neuwelt, and Eggleton3 propose ways to mitigate the stressful nature of Healthcare by rectifying the design of ‘in-between’ spaces.

Both texts discuss the relationship between healthcare design and patient experience, mainly focusing on the ‘in-between’ space. Key questions within the research include: 1). To what extent can the experience happening within the ‘in-between’ space promote well-being? 2). How can designers shape the patient experience through tangible aspects to ensure a positive experience and promote wellbeing?

‘In-between’ spaces, such as waiting rooms, are an embodied experience4. The experience of transition through these spaces happens alongside institutional processes such as taking a seat in waiting room and standing beside reception desk. It’s a transaction between ‘clinical structure’ with ‘the patient need’ which mediates explicitly through the staff instruction or tacitly through the spatial design. The experience was also a part of patient perception, studies shown range of sensory experience experiments, such as citrus smell and visual distraction (artwork), powerfully influences the sense of satisfaction within healthcare5.

Phillip Vannini in Kearns et. al. argued that activity within in-between spaces has a huge chance of becoming. Waiting activity is a momentarily delay from activities, to recognise something which could assist more connection to the environment. ‘It’s alive with potential for being other than this6. It is not a static experience, it change of time and has possibilities to obtain perception of comfort or relaxation. It draws a potential pathways of place to wellbeing.

The relation of experience and wellbeing, explained by interior designer7, Elina Grigoriou and Francis Richard, 2019 in the book ‘Wellbeing for Interior Designers’. They define wellbeing as a state where there is a feeling of wellness and happiness in the body, the mind, and the emotion. It’s added that it could be achieved by aiming for beauty / harmonious design, but it is not an object; “it’s an experience”. This can happen in the negotiation of space and place, enabling a holistic interaction of physical, emotional, societal, and environment

The atmosphere and sense of space.

Gernot Bohme defines ‘atmosphere’ as the key to the mindful physical presence within a space, creating the sensation experience through the specific ‘generators of atmosphere’ tangible and intangible element.8 Along with the argument, Rebecca McLaughlan and Julie Willis propose an atmosphere of inclusivity to ensure a communicative hospital environment for its user.9 Emphasising evidence-based design McLaughlan and Willis identified the design of Royal Melbourne Hospital as ensembled visual cues that blend as a whole journey to the users. The architects intended the hospital to enable a strong sense of place that is capable of driving curiosity and discovery experience. In these findings, vision was the strong aspect of sense, made in the public spaces of hospitals through artwork. It had a positive response not only for the children targeted but fostering a conversation between the staff and family to interpret the painting, building a sense of connection.

Consistent with the findings of McLaughlan, a strong sense of space drives curiosity and fosters discovery and connectivity. Regarding the harmonious goal of well-being in the relation between people and place, Phillips et al were intrigued to have ‘curiosity’ as the catalyst to wellbeing. They found that curiosity can trigger attention, memory, and sensibility within a place.10

In healthcare design, treatment and recovery is a significant experience for individuals. Cameron Duff identifies an atmosphere of healing, in becoming well, that can have the atmosphere of sociality, safety, belonging, hope and belief.11

8 Böhme, G. “Atmosphere as Mindful Physical Presence in Space”. Building atmosphere, OASE, (91), (2013), 21–32. Retrieved from https://www. oasejournal.nl/en/Issues/91/AtmosphereAsMindfulPhysicalPresenceInSpace

9 McLaughlan, Rebecca, and Julie Willis. “Atmospheric Inclusiveness: Creating a Coherent and Relatable Sense of Place for a Children’s Hospital.” Journal of architecture (London, England) 26, no. 8 (2021): 1197–1218

10 Phillips, Evans, and Muirhead, “Curiosity”, 2348-2349

11 Cameron Duff, “Atmospheres of recovery: Assemblages of health,” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48, no. 1 (2015), https://doi. org/10.1177/0308518x15603222.

‘In-between’ spaces experience and wellbeing.

Top :

The interior of Maggie’s Center in Leeds, a circullar tree shape kitchen wall.

Designed by Heatherwick Studio

Bottom:

Self sustaining Australia home, producing vegetable, fish, and where nature and beauty meet symbiotically

Designed by Clinton Cole (CplusCArchitectural workshop) & Interior Designer, Jase Sullivan

The atmosphere of sociality is placed in rich social connection activities; the atmosphere of safety and belonging mimics what the domestic environment does, feeling secure in a familiar place; The atmosphere of hope and belief is effectively transformative and face new aspect in time and space, like the feeling when looking at nature, which enables motivation.

12Martin, Daryl, Sarah Nettleton, and Christina Buse. “Affecting Care: Maggie’s Centres and the Orchestration of Architectural Atmospheres.” Social science & medicine (1982) 240 (2019): 112563–112563.

13Bjarregaard in Martin, Daryl, Sarah Nettleton, and Christina Buse. “Affecting Care: Maggie’s Centres,” 6.

14Martin, Daryl, Sarah Nettleton, and Christina Buse. “Affecting Care: Maggie’s Centres,”, 6.

15Böhme, G. “Atmosphere”, 27.

The deal for designers.

In-between space is often a transitional space where people receive their first impression of a place. In the Maggie’s Centers, non-residential care buildings dedicated to those with cancer, their family, and friend, people were attracted to the building even before experiencing the threshold of the entrance.12 This reinforces how important the momentary experience of entering a building is to staging its atmospheric qualities13, which leads to Böhme generators of atmosphere.

In the case of the Magie’s Centers in Leeds, the attractive shape and material of physical elements of the building (the wooden tree form) enable an exploration from different angles. The tactility of the materials provide a feeling of warmth from the timber. This user experience through the unusual shape of architecture triggered ‘curiosity’14 and one of the generators to the atmosphere.15 These elements within the spatial environment fosters attention to objects, triggers sense of space to evoking memories, and also influence happening conversation which advantages social engagement for building a supportive healthcare community.16

17Kearns, Neuwelt, and Eggleton, “Permeable boundaries?”, 3.

18Böhme, G. “Atmosphere”, 27.

19Ibid.

20Phillips, Evans, and Muirhead, “Curiosity”, 2349.

21Duff, “Atmospheres of recovery: Assemblages of health.”, 66.

22Ibid.

23Ibid, 73.

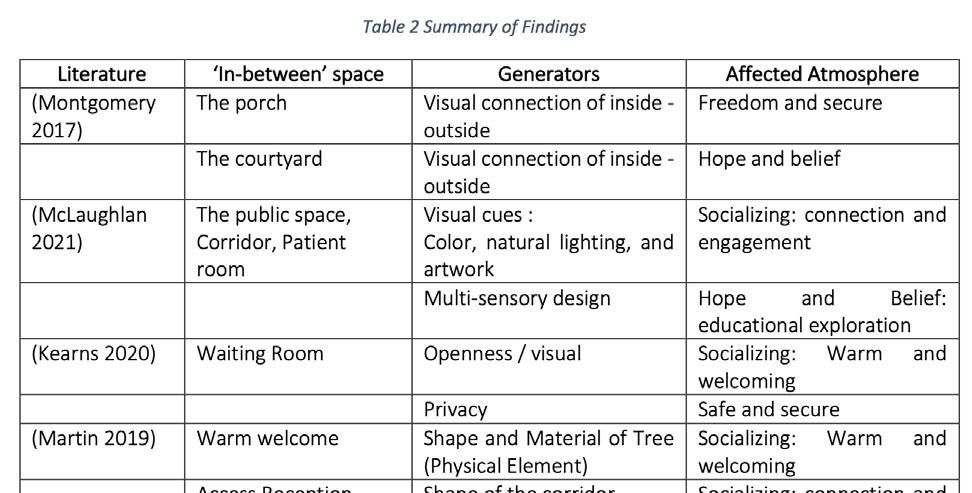

Identified through the literature, these critical findings of the physical environment and the affected atmosphere summarize in the table:

From the case studies, there are several samples of atmosphere generators found within ‘in-between’ spaces that affected the positive experience for the user. These could be tangible or intangible elements such as visual connection (permeability), unique shape and materials, and multi-sensory design. The generators mediating curiosity between objects to subjects (user) affecting experience in socio-psychological aspects supporting the recovery22. It set the goal to Healthcare design to create ‘Affective Recovery Atmosphere’ using experience in the ‘in-between’ spaces to permeate the comfort of ‘becoming well’23 and to reach the state of well-being.

Conclusion

The literature reviewed each promotes the idea that ‘In-between’ space plays a significant role in shaping the whole experience of place. This often to be the first encountered transitional space mediating patient needs with the ‘clinical structure’. There is a potential to enhance the spatial perception17 at the momentarily pause within ‘in-between’ activities to mitigate bad experiences. It allows the design to staging the atmosphere that supports well-being such as comfort. As mentioned by Elina Grigoriou and Francis Richard, the experience helps create a harmonious design to maintain happiness in body, mind, and emotion, as a pathway to experiencing wellbeing.

The key to shaping spatial perception lies in atmosphere and also sensation18. These can be generated through atmosphere ‘generators’19 that could enabling curiosity20. Curiosity itself can trigger attraction/attention which enables the sense of space to the atmosphere. It also provokes socio-psychological aspects such as evoking memory and driving social engagement. Therefore, Curiosity becomes the catalyst to develop the atmosphere of recovery to sociality, safety, belonging, hope, and belief.21

Major influence on Conceptual, Narrative, Programming, and Composition and Technology. These communities influence me most since I graduated from Architecture Degree.

Project Phase

CONTENTS : STAGE 1

1. Wellness or Wellbeing?

2. Institutional Moment

3. Exploring Affordance

4. Atmosphere Inclusivity

SUMMARIZE STAGE 2

1. About the Project

2. Programming, Site, and Stakeholder

3. Design

4. Reflection

24Definition of wellness by The Global Wellness Institute, https:// globalwellnessinstitute.org/whatis-wellness/

25Definition of wellbeing by World Health Organisation, https:// www.who.int/data/gho/data/major-themes/health-and-well-being

26Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Wellbeing Concept, https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/wellbeing.htm

27Grigoriou, Elina., and Richard. Francis. Wellbeing in Interiors : Philosophy, Design and Value in Practice. Milton: RIBA Publications, 2019 XII-XIII.

1. Wellness or Wellbeing?

This project aimed to understand the concept of wellness and wellbeing through literature studies and case studies of building / physical environment. It aimed to unveil what’s the need for designer to create a spatial design that can support these concept.

The project analysed the collective definition of wellness and wellbeing from many perspectives. It gathered definition from health-focused point of view, development studies, and also from designer/practitioner. This shaped the foundation thinking to select and analyse the case studies.

The method to understand the general knowledge about wellness and wellbeing helby by study literature. Then, it could define the elements of wellness and wellbeing that can be supported by physical environment. These elements became the variable to be analysed on each study case.

The Global Wellness Institute defined wellness as an active process to pursuit a health existence24 and the World Health Organisation stated that health is not merely the absence of sickness but also a state of physical, mental, and social well-being25. Wellness is an conscious attempt to pursuit health, and this will also help the wellbeing state. Wellbeing is a holistic concept of life satisfaction and happiness. Well-being integrates mental health (mind) and physical health (body) resulting in more holistic approaches also to disease prevention and health promotion26. However, it different to the designer perspective, the wellbeing concept was being approached as the beauty experience27.

The elements of wellbeing consist of the presence of positive emotions and moods (e.g., contentment, happiness), the absence of negative emotions (e.g., depression, anxiety), satisfaction with life and fulfilment. Wellbeing is an accumulation of individual body, the relationship within the surrounding, and it also deal within a huge time frame.

For instance, certain memories of past experience can also be a part of the happening of wellbeing. This also bring the Maslow diagram of need into the discussion. As wellbeing can span the fulfilment need from the lowest to highest level whilst wellness occurs on two levels of basic needs (safety and physiological needs). The wellness happens consciously and focuses more on individual body, to be in a good condition both mental and physical. Therefore, I think wellness and wellbeing are unseparated and wellbeing is a broad outcome to wellness.

Even though the happening of wellness and wellbeing are unseparated, the project tried to generated the main aim whether wellness or wellbeing. It was also analysed the designer strategy wto support the goal.

I learned that wellbeing and wellness are broad concepts. It consists of many aspect of economic stability, life fulfilment, and social engagement. However, through studying the several cases, a physical environment able to support the happening of wellness and wellbeing for the occupants. I identified that a built environment have specific program and function to support wellness and wellbeing and also have specific targeted user.

This led to a question about how actually a building can effect on people wellness and wellbeing? There are two factors I generated from the case studies the function of building and the interaction between building with the user. A clinical function of building can’t run by itself. The building run as an institution to operate the program and maintaining the function. The relationship between the physical element and the user are the main aspect to support the happening of wellness and wellbeing. Therefore, the next project needs to discover more about institutional and the user experience to it.

Image : An intense green ambiance in the a powder room, photo courtesy of Smac Studio from Dwell Magazine. I think, a little perception of wellness and wellbeing might be captured in the least expectant space like a powder room in an institutional space.

2. Institutional Moment

The last phase had two findings about the relation of physical environment to support wellness and wellbeing, the institution and how it closely related to user interaction with the spatial element. This project aimed to understand the interaction between user and the institutional space to understand about how spatial environment can affect people experience and inclusivity.

This project phase consist of two main steps: collective institutional moment and study literature about inclusivity. The collected institutional moment from four personal experience. The collection were made from sketches and become the tools to understand the experience people had within an institutional space. These sketches were analysed to gather the information about occupants experience with institutional element, both physical and non-physical.

The project used phenomenological approach to personal perspectives of institutional moments as the sample of user interaction with the institutional space. It did not use observation approach to control neutral aspiration to the institution. The project gathered sixteen moments. These visualized through sketches and close captioned to generate how the moment happened. Those moments were analysed by categorizing the element of space, non-physical institutional element and the type of experience, positive or negative.

The next phase was the further step from the conclusion to the previous institutional moment analysis. This phase studied about the relation of user and inclusivity to understand more about the happening of the institutional experience through literature study.

After analysing the sixteen institutional moments, there were two types of experience happened. The positive experience made user felt the enchanted moment, feeling curious, acceptance, and comfortable. In contrast, the negative experience made them felt pressed, controlled, uncomfortable, and bounded. These identified experiences mostly happened in the in-between spaces; waiting room, lobby, and corridor.

There was also identified several specific action from the user in respond to the experienced especially for the uncomfortable experience. In the setting of a bounded waiting room, people concerned to look for distraction on ceiling to escape people eye contact in waiting room. In entrance area, a tightly controlled lobby area by the nurses made people want to hide in order seeking for privacy. In the exit way, people started to wave on the automatic door sensor to make the door opens.

Meanwhile the positive experience made people observing more the space because feel attracted and comfortable to explore the element of building. For example, the lobby of office space had a clear direction and friendly staff generated a distinct access and generate happiness through the warm-welcome. The magnificent entrance enticed people to come in and driven curiosity about what is in the inside. For this cases, the spaces could fulfilled the friendliness, approachable, and accessibility to the user.

The question raised after findings the both types of experience: How to understand the user need?; and How these positive experience can help support the wellbeing? To answer the question I jumped to the next step to understand more about user profile and feeling.

Image : Sketched for Phase 2, Recalling institutional moment

Top part : An excited feeling to explore an institutional space after being allowed to go inside from the receptioonist.

Bottom part: Hide and seek feeling in the waiting room under observation of the triage due to the regulation of ‘caregiver wait ouside’.

Image : Mind map from team’s discussion about the occupant experience inside an institutional space could affect how people act.

The Institutional Image and User Profile

The institutional space is a built environment and a public space that run by an organization. It has the power to rules and state the constraint. Therefore, there are many aspect to control the building function such as rule and regulation, procedure, order, and system. However, they must facilitate a lot of people with different background, culture, and different condition.

Due to this condition, institution relied a lot in their procedural system to control the activity inside their building. So that, the atmosphere of the space built to create the powerful and rigid image. These what usually made a lot of occupants felt uncomfortable as their freedom to do certain activity are being pressed. As example mentioned in the literature review, the boundedness of the waiting room made user felt unable to move or did anything else beside waiting and observing the clerk28.

These rigid spatial environment, usually run for a general user which is the majority. As mentioned before, a public space should be facilitate a diverse users with various background and condition. These made a lot of gap of service that unable cover the specific need for people beyond the majority or neglecting several services outside the main clinical services.

From the literature study, this diversity aspect should be emphasize in the service of institution. “Diversity is about what makes each of us unique and includes our backgrounds, personality, life experiences and beliefs, all of the things that make us who we are.”29 Diversity also attempt to recognize, respect and value differences between any gender, age, race, religion, and sexuality condition. The inclusivity happens If these people could feel respected and valued, celebrated the diversity. They won’t feel neglected, feel the supportive environment, and have the equal opportunity. These actually part of high level Maslow pyramid of need which can generate the wellbeing.

The positive experience happened in the institution can be taken as an achievement to the friendliness, approachable, and accessibility which mean the occupants rarely feel discriminate and feel valued/respected. These interactions, especially the negative ones, produce several strategies showing how users deal with the controlled situation (institution). It usually happened as the institution has the constraint and certainty to order people in their space.

In the designer’s view, this is an opportunity to create a mindful moment to increase interaction between people and places. However, should designer still facilitate this rigid institution system into the design for wellbeing? One contradictory to this, should designer create a space that support de-institutionalization? This will aim for building more positive experiences to the built environment.

Back to the definition of wellbeing as an experience30 . Designer needs to create to support the positive experience through the spatial element of a building. How physical element of building give affordance and able to attract people to create a mindful physical experience? This also related to the literature review about the key to a sensational experience is called atmosphere31.

28 David Bissel in Kearns, Neuwelt, and Eggleton, “Permeable boundaries?”

29Diversity and inclusion strategy 2019-2021. Victoria Government. https://www.vic.gov.au/ dpc-diversity-and-inclusion-strategy-2019-2021/victorian-government-commitment-diversity-and

30Grigoriou, Elina., and Richard. Francis. Wellbeing in Interiors : Philosophy, Design and Value in Practice. Milton: RIBA Publications, 2019 XII-XIII.

31Böhme, G. “Atmosphere as Mindful Physical Presence in Space”. Building atmosphere, OASE, (91), (2013), 21–32. Retrieved from https://www. oasejournal.nl/en/Issues/91/AtmosphereAsMindfulPhysicalPresenceInSpace

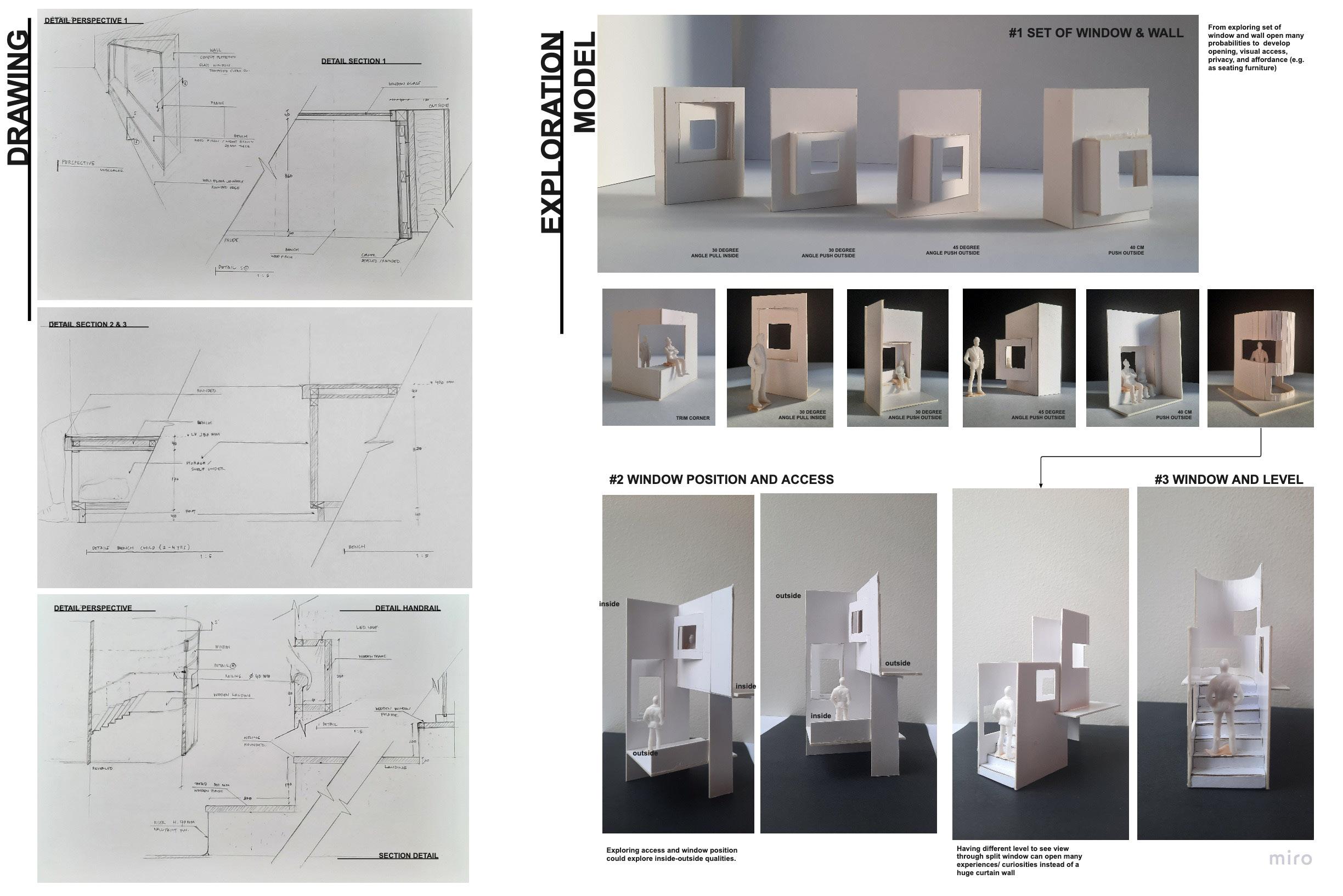

3. Exploration of An Element of Space to Afford Friendliness, Approachability, and Accessibility

The previous project analyzed how the user experience in the institutional space. The issue was about the overpowering atmosphere of constraint and rules in the institutional space to the user. It created an atmosphere of high formality for the user. Hence, it made the occupants feel powerless and restricted from freely doing their activities. It happened even for the activities that did not violate the rules. The assumption from the previous findings was that the user would be felt more appreciated in a ‘less formal’ environment. The ‘less formal’ here means the absence of a different rank between the staff of the institution and the occupants. For instance, the greeting from the receptionist made the occupants feel welcomed and accepted in the building. This was one example of a positive experience relating to a subject who represented the institution. As the designer, I thought it was important to investigate more how a positive experience could be created in a space. I found that one way to approach this was by making the space to be less institutional. There were two aspects that I would investigate more in the research, the physical element and the case study on the inclusive interior. In this project, I aimed to explore the first aspect of how spatial elements can support more informal activities to explore the idea of the de-institutional space.

To explore the physical elements of space, I examine a range of alterations consisting of two elements with a constant and relative variable. These alterations were looking for a space that could give affordance to informal activities enhancing the atmosphere of ‘less formal’. I put special attention to enhancing space to afford the support of conversation. Hence, I aimed to create a friendly atmosphere

in space. This project also used to explore spatial keywords which able to explore more varied alterations. I choose the elements of boundary and opening through the spatial modeling with a keyword of expanding and tilting.

Even though it was a continuation of the previous phase, the methods of approach consist of studying literature about what is the meaning of Atmosphere Inclusivity. The targeted space to be explored was a transitional space such as a corridor. Therefore, it began with studying literature on the history of a corridor in order to extend an understanding of a corridor. After gaining the concept, I created some sketches. Firstly, I used the previous alteration modelling to produce the corridor scenario. After some first sketches, I divided the experience of a corridor into three categories, consisting of the beginning, the middle, and approaching the end.

I choose the element of openings, which I defined as the window and the access or entry point. I created a series of window expansions from the wall with several variables of pushing the window, tilting the window, and folding the window. I also explored the window based on the height and the angle (for the tilted window idea). In the second step, I modified the location of the window with several heights and positions to be seen from different entry points. I took photographs with a person figurine standing or seating to enable seeing on a human scale. In the later step, I inverted the position of the tilted window and the wall. The wall, previously, was vertical, and on this step, I changed it to a tilted wall. I made several alterations with height variation and various accessibility directions to see the point of view of the user. After that, I analyzed through photographs and saw the affordance of the space.

The goal was to look for the friendliness element, approachability, adn accessibility.

The last step was an exploration of the possibilities dimension with sketches. In the previous findings, I found that the expansion of the window will give more space to pause, rest some part of the body, and sit. Therefore, I did more research on the human dimension, from children and adults to see the accessibility for broad users. Through some sketches, I researched the application of some materials to examine the atmosphere.

1. The Window Expansion

The window expansion was perpendicular to the vertical wall. It afforded support to sit or rest depending on height position. The tilted window affords the same thing. However, it depends on the angle degree and length of the expansion, small-angle needs a longer expansion until reaches the affordance to sit and vice versa. It also gave the quality to direct the point of view of the user.

2. The Window Position and Curve Wall

The window position lay along the curve wall gave a different view from the window on the flat wall. The curvy wall afforded to widen the view. Later these qualities combined with the leveling access to afford a different view.

3. The Combination of Access and Window Position

The main aspect of the positioning of the window and the access was the perspective view from the user. It was combined with a sense of direction and a connection.

The potential qualities were found in the curve wall and tilted window. I found that it could be combined with the direction and leveling as given context the relation with the user perspective. Later, I combined the 2 directions with a titled wall and elevating platform. It performed an upscaled experience where the user will unconsciously switch from inside to outside or vice versa.

Image :

Exploration of affordance with detail sketches and physical modelling.

32 Schneiderman, Deborah, Anca I. Lasc, and Karin Tehve. Appropriated Interiors. Milton: Taylor and Francis, 2021.

33McLaughlan, Rebecca, and Julie Willis. “Atmospheric Inclusiveness: Creating a Coherent and Relatable Sense of Place for a Children’s Hospital.” Journal of architecture (London, England) 26, no. 8 (2021): 1197–1218

34Montgomery, Terry. “Cultivating the ‘In‐Between’: Humanising the Modern Healthcare Experience.” Architectural design 87, no. 2 (2017): 114–121. tions, 2019 XII-XIII.

35McLaughlan, Rebecca, and Julie Willis.

36Jarzombek, Mark. “Corridor Spaces.” Critical Inquiry 36, no. 4 (2010): 728–70. https://doi. org/10.1086/655210.

4. Atmosphere inclusivity in Institutional Space

From Phase 2, the interaction between the user and building element in an institutional generated experiences both positive and negative. These interactions, especially the negative ones, produced several strategies showing how users deal with the controlled situation. In the designer’s view, this is an opportunity to create a mindful moment to increase interaction between people and places. After exploring the spatial iterations in the previous phase, this project had a goal to test spatial affordance, the occupants of the space, and the atmosphere created. These several strategies were supposed to create a mindful institutional space supporting users’ wellness and wellbeing.

The introduction of Appropriate Interior written by Karin Tehve explained that

interiors exist within and without the domain of designed environments and are thus more able to reflect and support a broader and more inclusive set of values.32

Therefore, when this project began to deal with the atmosphere and user, it was needed to have a perspective on the diversity aspect of the user. This was important as aiming to the respected environment which is part of wellbeing33 In this phase, the strategies focused on the transitional space: the corridor and waiting space. As these areas are mentioned and highlighted in Montgomery and Kearns’s writings as a space that is full of potential34.

Even though it was a continuation of the previous phase, the methods of approach consist of studying literature about what is the meaning of Atmosphere Inclusivity. The targeted space to be explored was a transitional space such as a corridor. Therefore, it began with studying literature on the history of a corridor in order to extend an understanding of a corridor. After gaining the concept, I created some sketches. Firstly, I used the previous alteration modelling to produce the corridor scenario. After some first sketches, I divided the experience of a corridor into three categories, consisting of the beginning, the middle, and approaching the end.

- What is atmosphere inclusivity?

In the writing of Rebecca McLaughlan and Julie Willis,“Atmospheric inclusiveness: creating a coherent and relatable sense of place for a children’s hospital”, they gave a short explanation of atmosphere inclusivity. Atmosphere inclusivity was a quality that been perceived from a combination of building elements to the user without giving any exclusion feeling. The building should bring a user feel respected regardless of their background and condition. This relates to what space can afford to facilitate this. McLaughlan and Julie Willis35 highlighted several strategies indicated as a factor in building the atmosphere of inclusivity in The RCH case study. Some of these were connected to nature and social connections. Another thing was visual cues of turning distraction into an attraction.

- The history of corridor

Mark Jarzombek wrote a history of corridor36. Corridors since the 14 century used to connect one building to another building and are located in an outdoor setting. With the development of the complexity of the building, the corridor then connected one room to another. However, these were closely related to the sense of hierarchy, different access for servants, and dealing with speed of movement. The function of corridors began to develop after post-world war II when there was a movement against corridor. It shifted the function as a gallery and have a sense of interaction in the middle of a corridor.

What was interesting for me from these two aspects (the case study of RCH and the history of the corridor) was the element of attraction and pace of movement. I thought that this can be a possibility to be explored more with the two keywords I found previously. I decided to approach the in-between space of a corridor and analysed the strategy waiting space using this perspective. In this project, I explored the corridor using the previous keywords and analysed the waiting area from the strategy found by the other group member.

I found that a corridor and waiting area had different characters to the speed. The waiting area is a place to pause. Some people found that they were caught in-between of activities37. What happen in the waiting area was a static activity where users would sit still or stand. They were longing for the next move. While the corridor was a fast pace environment. It gave the feeling to move fast and hurriedly. However, both are discussing the same variable time and pace, slower or faster. This could be integrated with the placement position of the attraction to distract the movement.

- The waiting area strategy: Enjoy the time that slowly passes.

Users always had a phone to find something interesting while waiting. From this point of view, a user (adults and children) got bored easily during waiting. It gave an idea to develop the area of waiting with a different level of experience and added different activities to fill the long waiting duration. The activity to be added as a test were book browsing, book reading, and interactive digital art. The activities chosen are activities that can be both enjoyed by different age groups, gender-neutral and general activities that everyone can enjoy.

The adult experience was to enjoy a digital interactive display and a distraction near the ceiling. This encourages to have a relaxed waiting with a supportive/comfortable lounge chair. This would be different for a targeted group of children. It had a side goal of education. For example, an introduction to color or animal.

The corridor strategy:

Reducing the pace, encourages a walk and conversation. The corridor was located between two functional spaces. It connected one activity to another activity. However, during this transition, did actually people need to be hurried every time? One user might need to catch their breath first. Other, might be the clinical staff who need to run errands and move directly from one clinical space to other. Therefore, it came to the question does it support the pause or support the continuation?

Here, the expansion keyword is applied. The expansion space of the corridor can be utilized as a waiting area, or conversational space near the clinical area such as a consultation room, or just a place to take a breath. This aim was to reduce the pace but actually not try to eliminate the main function of the corridor to connect the access from one place to other places.

This corridor can also be blended with the waiting area and the most encouraging one is to place near the courtyard. The space expansion for the conversational space can activate the courtyard, not only for sightseeing but also for the happening of the conversation. The corridor treatment was generated into 3 types.

1. The attractive start

The starting point of a corridor was a transition from the previous space. At this point, I tried to expand some parts of the corridor to be an attraction point. This would become the first view for the user as an invitation and gave an atmosphere of friendliness. It aimed to build a positive experience from the beginning of the journey along the corridor. The strategies found for this were making a different material from the previous room and positioning a visual connection to nature or attraction from the first glance. The visual treatment was used to eliminate the unfriendliness of the corridor. This attraction in the beginning also aimed to give a momentary pause. It would reduce the feeling of anxiety to move in a hurry. Therefore, a user would be able to have a sense of place.

Image :

Exploration drawing of spatial strategy in corridor setting.

Top : Expansion in general corridor area, Middle : Position of entrance, circukation, and expansion point as attaction, Bottom : expansion in the middle part of corridor.

2. The middle curiosity

After building the experience from the beginning, I tried to maintain the curiosity of the user. Therefore, I decided to segment the corridor into several parts with the division of expansion space. I tried several strategies to expand the space.

The strategies :

a. This expansion created a bigger corridor space. I applied a transparency material to the ceiling and the wall of the expansion space. I also tried to have a floating bench. Given the idea of expansion not only from the corridor side but also the visual connection expanded from the outside to inside. These afforded a slightly paused when walking down the aisle. The expansion from the outside, into the bottom of the benches, became a surprise detail that might attract people to come and have a more detail look.

b. I expand the space as a stage to observe the nature or courtyard. This will be located near a consultation room. So that, a user can take a rest after an intense discussion in the consultation room. I also connect the expansion space to the courtyard and arrange some furniture. The furniture and view could afford a medium of conversation, building connections among the users.

The material on the expansion space should use a warm and different material from the general corridor as indicate the different pace. I tried to use the warm timber flooring to afford comfort and close with the natural element.

c. I found a strategy to expand with a tilted angle to create a continuous journey but have a different experience. It also played with the boundary of inside and outside. So, I tried to apply the alteration to a circulation. The corridor were connected with a tilted opening.

When the user came out of the opening, they would walking to the different side of the space. I used a small garden as a surprise element differentiating more one space to the other space.

3. The Ending Frame

Just like in the beginning, I would like to shape the experience for people to have a sense of achievement to reach the very end of the corridor. Therefore, I tried to attract with a full-frame expanded view from the outside. From far away it would look like a painting, framing nature. However, if a user came close, they could expand the view into the ceiling.

The idea to slow down the pace did not mean to slow the movement in general. It was to calm down the anxiety to take a momentarily pause for looking at the surrounding. The application to this must be reflected on the user’s needs. Like what I identified before, clinical staff needs to move faster therefore the fast pace corridor had still been there.

Moreover, I found that the idea of connectivity and expansion can be combined with the treatment material. To slow down the pace of movement could also use the differentiation of texture and pattern of the material. For instance, an old brick pedestrian path would slow down the user’s movement. A tactile material could also attract the sensory to feel and touch the material.

Another thing that I reflected on in this project was the use of only one sensory, visual. However, the input from BLP pointed out using a smell or maybe a hearing to build another experience. I thought this was a really good idea. The writing from the Phillips about building the curiosity with the sensory of visual and touch. It would make the user think more about their past memories. If the design can stimulate a happiness memory for the user, it would be a great support for wellness and wellbeing.

37Martin, Daryl, Sarah Nettleton, and Christina Buse. “Affecting Care: Maggie’s Centres and the Orchestration of Architectural Atmospheres.” Social science & medicine (1982) 240 (2019): 112563–112563.

What can I get from the literature review and exploratory stage for the final design?

From the literature review, the goal of the design was to create a positive experience in the ‘in-between’ spaces to permeate an affective recovery atmosphere such as warmth, welcoming, relaxing and friendly. It is gained through activating the atmosphere generator to afford curiosity. Furthermore, from the exploratory stage, I found that the atmosphere generator not only defined the spatial qualities. Hence, it also generates the affordance for the user to occupy the space based on the designer scenario. It can be approached by implementing the next findings of spatial strategies. It consist of pausing the moment, tilting the physical element, using a curve boundary, and using a spatial keyword: expand. These can be applied to develop the design, especially in the ‘in-between space’, to activate the atmosphere generators

I wondered if this was the right direction to go with. As this is generated from a personal experiment, I have a case study in mind that want to investigate these strategies. I also want to rethink how these related to the idea of inclusivity, atmosphere, and affordance to support wellbeing.

From the literature of Affecting care: Maggie’s Centres And The Orchestration Of Architectural Atmospheres by Daryl Martin, Sarah Nettleton, and Christina Buse, they concluded that the most influential element to create the Healing Atmosphere in the Maggie’s Centre was materiality, colour, light, shapes, and form building in particular. These are the atmosphere generator in Maggie’s Centre37.

The other findings was about the user experience scenario. It should consider the user profile such as age group, gender, and special needs to make sure creating the respected environment. I could be from the accessibility and circulation to ensure the design inclusive for every user. Therefore, it would affect much on the layout of the design.

The atmosphere of Maggie’s Centre was a healing architecture intended to be a safe space for people with cancer. The program included a nonformal table talk, consultation with a psychologist, a workshop, and finding support to combat cancer. “Maggie’s transformed what seemed totally overwhelming into something manageable.” Just how finding someone to talk to. The atmosphere creates the affecting care and offers warmth and welcome. It was surrounded by a relaxing atmosphere with a garden and kitchen at the heart of it.

“

Programming / Layout Kitchen as the heart Friendly Engaging Social connection (Conversation)

Participatory design

(The visitor was encouraged to bring and decorate the space with their own things) Inclusivity,

Programming / Layout Kitchen as the heart Friendly Engaging Social connection (Conversation)

Multi-sensory Visual scenery to the greenery Exploration Interest

Material Wood, stone, concrete Warmth, homey, relaxing

Programming / Layout Kitchen as the heart Friendly Engaging Social connection (Conversation)

Color & Lighting

Natural material, natural daylight, and soft warm white Warmth, homey, and relaxing

Image : Qualities and Atmospher Generator in Maggie’s Centre Leeds

Image source from Archdaily, “Maggie’s Leeds Centre / by Heatherwick Studio

5. Design Process: Shepparton Nutritious Hub

#GROUP WORKS

5. Design Process: Shepparton Nutritious Hub

About The Project

The project was to design the wellbeing centre located in Greater Shepparton, Victoria on the corner of Wyndham Street 409-415. The city of Shepparton has a diverse community consisting of First Nation People of Yorta Yorta Nation, English-speaking counties communities, and other cultures. A wellbeing centre dedicated to the community of Shepparton to support the health of the Shepparton community and the achievement of wellbeing as the goal. In the Victoria Public Health and Wellbeing Planning 2019-2023, there are focus areas to protect the community and increase healthy eating. Furthermore, Greater Shepparton City Council choose eleven liveability domains and underpin goals for the health plan. The group project underlined the access to food and community participation as targeted responses for the wellbeing centre design.

Focusing on the Greater Shepparton profile as the ‘food bowl of Australia’, they still face health issues for about 54% of the people do not meet the dietary guidelines for either fruit and vegetable (The Greater Shepparton, 2018-2028 Public Health and Strategic Focus). Moreover, the Shepparton Kitchen Culture project unveils that the minority group found that it was hard to find their local food in the city37.

Therefore, the wellbeing centre, will support healthy eating habits to support wellness. Whilst also celebrating the inclusive cultural community with a vibrant social atmosphere through food and nutrition. Refer to Terri Peter writing about super architecture. We aim for the building to provide a therapeutic design through the incorporation of nature in the design with several keywords: sustainability and biophilic design. It will be a health-promoting building

and strengthen salutogenic potential, and bring more happiness, to the community of Shepparton. The group project decided on name Shepparton Nutritious Hub.

Programming And Service

This project’s programming and services were inspired by the production of food from the garden, harvesting, cooking, and bringing to the table to be shared as part of a cultural movement. It will provide a consultation service supporting their mental health, nutrition requirements and lifestyle. A therapeutic garden will be integrated into the space, creating a biophilic atmosphere as well as contributing to a community garden, growing a bond with an inclusive activity. There will be an opportunity to participate in gardening classes to learn how to grow fresh produce at home, promoting accessibility to fresh produce and a chance for children to learn where their food comes from. A café will afford a space for the community to gather, especially the elderly who live alone and find comfort in socializing with others and will be open to the public. The coffee waste used in the café will contribute to the garden’s fertilizers and food waste will be used for the garden’s compost.

The Shepparton community has expressed a need for a communal kitchen to provide them with a space to share meals together. It will facilitate a space for classes, in collaboration with Shepparton’s Culture Kitchen by MAV, to learn quick and healthy recipes. This space will celebrate the multicultural community of Shepparton by sharing recipes and creating events that can shape the communal haul. Teens will also be able to grow their hospitality skills to potentially acquire a job. In conjunction with the kitchen, the garden will allow people to pick fresh herbs and produce from the garden and in cooperate them into their meals. The exterior of the building itself will be used as a canvas for murals created by the community and become an experience for people circulating in the neighbourhood.

37Shepparton City Council, Public Health Our Strategies Focus 2018-2028

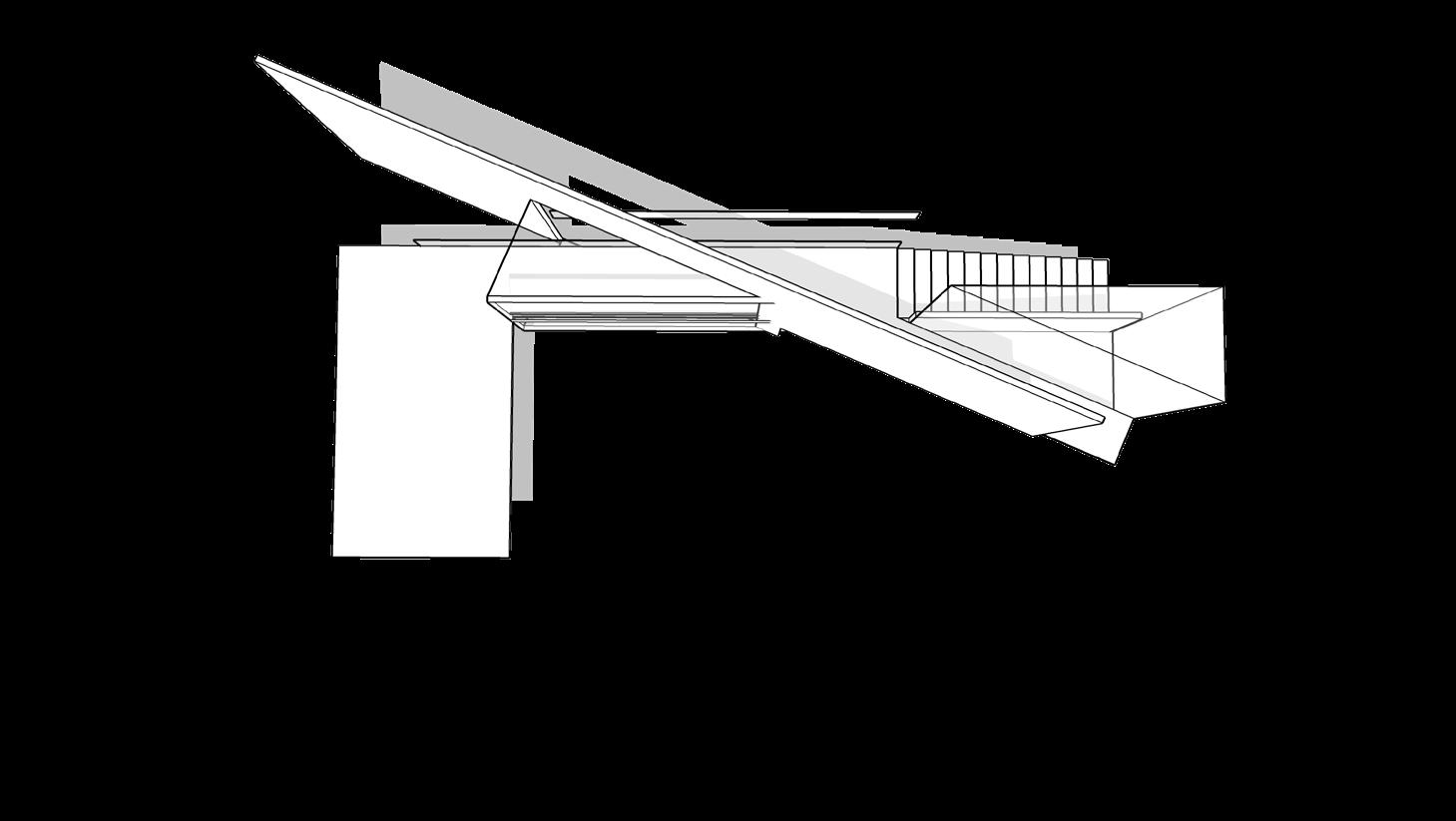

To create the Hub, the massive being slice into three parts.

(Group 1, Food and Nutrition, created by: Shinta Sari)

THE HUB

The group idea decided to bring awareness to the community of Shepparton about healthy eating and healthy food. It had another goal to reduce formal institutional design and promote the activity without any formal invitation such as a procedural appointment to come to the centre. The community were welcome to visit the hub anytime, to sit and enjoy the event together. Therefore, we combine the idea of walking and displaying the campaign poster in the shortcut. The idea was to create a walkable experience, to have a relaxing activity while also get information about the healthy eating campaign.

The shortcut lies along the building to connect the main street of Wyndham Street to the small alley where the cultural event will be organized. It is located in the center of the building, cutting the mass into 3 parts, and became the focal point of attention from any level (diagram 1). The three-zone would be used for the food gardening and processing activity, from garden, dining, kitchen, and community hall then connecting for the consultation in the next level. The shortcut alley was designed using a dynamic shape as tools to attract users. It can be seen through the layout.

THE USER EXPERIENCE SCENARIO

This step was aimed to address accessibility and inclusivity to every user profile. I identified that the user would have many different types. I analysed from the targeted group and sought for the probability of scenarios. After that, I categorized the types from the age group and the destination.

Main accessibility is defined by how people travel to the building: walking, car, bike, and universal access. So it will have an entrance for cars and bikes, and the circulation will have stairs, ramps, and an elevator as the universal access. The next process defined the boundary and access for each destination and implemented it into the layout.

Image :

Top: Ground Level Plan

Bottom: The programming and flow of user scenarios.

(Group 1, Food and Nutrition, created by: Shinta Sari)

First Part: Diagram positioning about wellness and wellbeing with the service program arrangement.

Below Part: Strategy of the design with materiality, architectural form, and splitted level programming.

(Group 1, Food and Nutrition, created by: Shinta Sari)

Design Implementation of The Strategies and Results COMMUNITY HALL a. Programming and Layout

The community hall would act as the main connection to each zone, therefore the vertical connections majorly occupy the space. It formed theatrical seating as the strategy to answer the needs of facilitating events, gatherings, and vertical connections. However, with the accessibility aspect, it needed universal circulation. I used findings in my exploration stage about the tilted wall and access point to arrange many types of user scenarios in the area.

As the result, it turned out that there were too many circulations which could make user confused. Another consideration would be it could make user feel boring with too many stairs, ramp and corridor happened in one area. Therefore, I developed split level strategies and had the architecture shape as attraction to distract the multiple circulation in this area.

The Strategies:

- Split level programming

I break the programming of the theatrical style sitting in the community hall became 3 parts. The below level zone dedicated for the adult and elderly to watch the performance, workshop, or cooking demo. The medium level would be for the neutral zone (foyer) and afforded non-formal conversation. As the level got higher, the targeted group also getting younger. The highest level would be for the teens and children to learn about the hydroponic garden. This area was a flexible space. The racking for hydroponic created using modular system and could be moved to the basement food farm if there was any event happening here.

#INDIVIDUAL WORKS

- The tilted wall as the centre of attention and camouflage the circulation

The tilted wall was shown from the entrance. It directed the attention to the next area. It split in the middle and created the threshold for accessing the ramp/corridor. It became the envelope to the ramp with a set of windows to create the visual experience.

- Choices of furniture enhance momentary pause (In-between)

In the theatrical seating of community hall, it used the puff chair and coffee table to achieve agility and flexibility. However, on the landing foyer next to the consultation area, it changed from puff to armchair sofa, to afford relaxing momentary of pause after climbing the stairs or after consulting

b. Material, Colour, and Lighting

To enhance the idea of nutrition, the group decided to use tactile material with earth tone colour. The different material used in the hydroponic farm in the basement. It was combined with the timber flooring and transparency to achieve openness. The lighting used a warm white light to enhance the warmth.

c. In between Area: Entrance Point Affordance to de-institutionalize design.

The strategy was to give the first impression to a deinstitutionalize with a low height entrance to create the welcoming atmosphere. There was also puppies parking spot and stroller parking spot when there was an event happening. The door itself shaped like a rotating wall instead of a usual door. The entrance shaped also similar with the attraction slanted wall from the inside. Once the door was opened there would be a connection within an inside and outside.

The gate also served as the foyer transition to the community hall. It was shaped through making the canopy as the expansion for the threshold space and could be categorized as foyer.

Image : Exploration sketches: the relation within circulation, access, curved wall, and stairways

(Group 1, Food and Nutrition, created by: Shinta Sari)

Image Top: The basement draft plan, drawing a connection from community hall stairs with the basement food farm. The continuous circulation.

Bottom: Draft plan applies splitting diagram for Community Hall

(Group 1, Food and Nutrition, created by: Shinta Sari)

Design Implementation of The Strategies and Results

FOOD FARM

a. Programming and Layout

The program scenario mainly only serve the food farm (productive garden) with the hydroponic system. However, based on the user analyses, it would need a program that can attract people to go downstairs. Therefore, I added the market program with a mealkit ready to pick up recipe. The market itself later positioned in the center of the food farm, visually connected to the ramp connection from the community hall. It became the attraction program of the basement. To support the happening seasonal event, the furniture created in modular scenario as a counter / stall to display groceries. The other spatial affordance was the modular furniture, which allowed people to sit.

The Strategies:

- Split zoning of food farm into two part, divided by the market. The layout also have neutral space to be the flexible space accomodating eventual program (Harvest Day and Market Day)

- The Materials and Atmosphere

In the Shepparton Nutritious Hub there were two garden, the ground floor was the relaxing and education garden while the underground would be the productive garden. The system and garden function were different, therefore I decided to create a modern hydroponic garden with an ambiance of clean design with bright color apply in the middle (market). It gave another experience of garden for the user.

- The Accessibility

There were four accesses to go to the underground level, the ramp, the stairs continuation from the Community Hall, access from the carpark (drop off point) and access for bikers. These accesses from both internal and external (car and bike) made the Underground easy to access, allowed quick shopping and easy loading activity after shopping.

Images: Top: Rendering Food Farm (Underground Floor)

Bottom: Axonometry modular furniture for the market (Group 1, Food and Nutrition, created by: Shinta Sari)

Conclusion

Interior design can support wellness and wellbeing. From my finding, supporting the wellness can be with the spatial qualities of natural lighting, good air circulation, and programming layout. It is concerning more toward the physical wellness. In the context of an open brief project like the Shepparton Wellbeing Centre, services also become the part contributing to wellness.

Wellbeing was defined as the experience39. Interior design can support the wellbeing with creating the positive experience. To ensure the happening of the positive experience the designer aim to build the atmosphere of inclusivity. It made user feeling respected which can contribute to happiness memory of having a supportive environment, sense of belonging, comfort, and life satisfaction

The atmosphere inclusivity also meant having affected care atmosphere. It was not passive element, but it could drive action from the user. To achieve this George Bohme had defined atmosphere generators to activate mindful spatial presence targeted to the user (affordance).

The designer can shape the experience from major to minor. The crucial first phase would be understanding the targeted user and the programming to define the user scenario. This would be a major experience narrative. It also contributed to inclusivity to define the universal accessibility. From major experience narrative, designer shaped the furniture layout to define the activity within the program zones.

From the exploration stages, found that the atmosphere generators could be the architectural form, furniture, material, colour, and lighting. These aspects afford different qualities to the atmosphere. To build this designer should have the strategies to achieve the affordance.

The spatial strategies about affordance to more friendly atmosphere was found. Threshold expansion of opening position afforded a resting space for hand or to sit. It could also expand the view. Curve/tilted wall position to the access direction afforded wider view. The curiosity can be driven with the intriguing senses activity, texture, smell, hearing, and visual. It can give attraction of view, interactive display, or decorative element. The strategy could also be an expansion in circulation space to create a momentarily of pause in the transitional area. All these affordances allowed creating new experience to the user. Furthermore, to create the positive affordance it needs to match the user profile to achieve atmosphere inclusivity.

The transition from one space to another space should be smooth. The in-between space was the one that could sew the whole experience together as the major experience scenario works. The example from the design phase was the foyer of entrance in community hall. It’s connecting inside and outside with the similar shapes, the low ceiling afford de-institutional aspect, and expansion of the threshold to momentarily pause so user can prepare before coming in.

After investigating the relationship between interior design with the happening of wellness and the wellbeing of the user, I can conclude that the spatial generator activated the atmosphere inclusivity. The physical element and natural qualities afford the Wellness support. Moreover, the catalyst element for the happening atmosphere was the dynamic transition in the in-between spaces. Therefore, people can feel fully respected, whole experience which lead to create beauty experience as defined40 as wellbeing.

Shepparton Nutritious Hub

Annotated Bibliography

Anderson, Ben. “Affective Atmospheres.” Emotion, Space and Society 2, no. 2 (2009): 77-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. emospa.2009.08.005.

Ben Anderson, in the writing, tries to explain the broad definition of atmosphere and differentiate Affective Atmosphere from emotion. Ben Anderson compares several theories of definitions of atmospheres. Ben argues that atmosphere correlated with duality conditions. It enables the experience to occur beyond, around, and alongside the formation of subjectivity. It holds a series of opposites: presence-absence, materiality - idealist, definite - indefinite, related to tension.

The writer compares the theory of Phenomenologist Dufrene about aesthetic atmosphere and the Böhme theory of Atmosphere. The Böhme theory stressed more spatial qualities, in which ambiguity describes the atmosphere as neither subject nor object. It is closely related to the subject, belongs to the subject, and fills the spaces.

What I understand about the atmosphere through Ben’s writing is that the atmosphere is uncertain, it never ends, and related to the body and the interaction of bodies within space as a subject or object. Affected Atmosphere is impersonal and objective; it connects to several bodies. This distinctive aspect of emotion which personal and subjective.

Böhme, Gernot. Atmosphere as Mindful Physical Presence in Space. Architektur und Atmosphäre. 2006

The Böhme writing is a philosophical study examining the relation of atmosphere, senses of space, and place.

Böhme’s approach examines the Atmosphere as a Physical Presence in Space through an approach to the philosophy of space and place. He also explained through the citation of August Endell that what is important for a building is not the shape of the wall or structure, but the inversion of space that spread rhythmically between the walls. This emphasizes how Böhme wants to talk about the intangible quality of space. The space was earlier defined as spatium and topos, which are related to the body. Therefore, Böhme argues that space is where the bodies find their space through body movement. It leads to physical presence: the maintaining differences between body and mindful body (sensitivity)—the happening of the atmosphere through the receptive senses of the body to perceive the spatial elements.

Duff, Cameron. “Atmospheres of Recovery: Assemblages of Health.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48, no. 1 (2015): 58-74. https://doi. org/10.1177/0308518x15603222.

In this research, Duff wants to know what atmosphere likely supports the recovery stage from mental illness, especially how it creates the affective atmosphere for recovery. The context in which Duff held her research was in an urban setting, which was held by observing several cases. Duff observes the place as the central to affective creation and how encounters atmospheres support the project of becoming (recovery).

Duff was observed within the subject POV (the patient). In conclusion, 3 atmospheres are underlined by Duff. 1). The atmosphere for sociality (such as café, garden, etc.): a place rich in social engagement and socialization, 2). the atmosphere of safe and belonging, feeling secure and belonging (supportive community), and 3). the atmosphere of hope and belief, the transformation of time and space, feeling the motivation.

Grigoriou, Elina., and Richard. Francis. Wellbeing in Interiors : Philosophy, Design, and Value in Practice. Milton: RIBA Publications, 2019.

Grigoriou writes the book Wellbeing in the interior from the perspective of a practicing designer. Grigoriou argues that well-being inside the interior can’t be given but can be supported. The writers emphasized the element of well-being which consist of body, mind, and emotions. The writers argue that well-being is also beauty which is a goal to be achieved. Hence, beauty is an experience, not a static object. In this statement, I could relate even though it is a bit uncleared how the writer decides it is a beauty just by practicing experience as a harmonious goal. However, later I found that geography professor Sarah Atkinson also defines well-being as a process. Another noteworthily, the writer also emphasized how comfort is one important aspect between wellness and well-being.

Kearns, Robin A, Pat M Neuwelt, and Kyle Eggleton. “Permeable Boundaries? Patient Perspectives on Space and Time in General Practice Waiting Rooms.” Health & place 63 (2020): 102347–102347.

The writer examines the under-examined space in usual health care (the reception and the waiting room). The findings recap how occupants perceive the waiting room. Kearns highlights that the waiting room can be perceived as a 1. bounded container that issues the problem of enclosed space. 2. The uncomfortable action of gaze and proximity with others relate to the privacy issue. 3. The preferable waiting room is connected as a transitory space with a warm and welcoming atmosphere. The discussion leads to an approach to making transitory space enable relational permeability. Kearns addressed the issue of the liminality of in-betweenness, which somehow made the space tightly knotted to other spaces or activities. Hence, the occupant in the space is unable to move or have freedom of movement. The suggestion later in writing tells how the waiting room should be more open (apply permeability) to cross the boundaries of inside-outside without losing track of the recent activities in the waiting room. It also should enable a sense of privacy. However, the writing lacks design evidence. It highlights more the data collection of people’s perception of the waiting room and reception area. It is more like a critique to design that lacks visualizing information to grasp the spatial context.

Martin, Daryl, Sarah Nettleton, and Christina Buse. “Affecting Care: Maggie’s Centres and the Orchestration of Architectural Atmospheres.” Social science & medicine (1982) 240 (2019): 112563–112563.

The writing examines how designer’s intention in creating Maggie’s Centres and how the occupants perceive it. The writer defined atmosphere as phenomena intermediating the belonging of neither world nor person. It cited Böhme’s atmosphere definition. It then argues that the architect can create an affective atmosphere, but how efficient it affects will be unpredictable.

What interesting in the findings is that occupants felt that Maggie’s center was like ‘a silent carer’. How the inhuman can make a person feel motivated and belong there. Others also find that the building affective in charge was in aesthetic experience. This creates a relevant definition idea for Grigoriou, who sees wellbeing as an aim to beauty.

McLaughlan, Rebecca, and Julie Willis. “Atmospheric Inclusiveness: Creating a Coherent and Relatable Sense of Place for a Children’s Hospital.” Journal of architecture (London, England) 26, no. 8 (2021): 1197–1218.

The writers propose a new concept of atmosphere inclusivity as a design aspiration for healthcare design. The paper studies the performance of the healthcare design of Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital, designed by Billard Leece Partners. The writing also includes qualitative study observation and interviews. They conducted interviews with the occupant and also the architect in charge. These findings are relatively easy to follow due to several photos included in the paper. Several points noteworthily from this literature are :

1.Creating the attraction and distraction from the treatmet reduces anxiety while also opening a curiosity to exploration.

2.The curiosity-driven with the medium of artwork, visual cues (graphic and color)

3.It gives children a space to explore, experiencing the place unrelated to the clinical activity.

4 The multi-sensory design (explorative) enhances the experience, which means engaging the sense of place in the healtcare

Montgomery, Terry. “Cultivating the ‘In‐Between’: Humanising the Modern Healthcare Experience.” Architectural design 87, no. 2 (2017): 114–121.

The article discusses the urgency to design atmospheric ambiance in ‘in-between’ spaces between clinical spaces, which is usually neglected. This space usually deals with many unsatisfactory institutional moments, unhappy memory, and feeling uncomfortable within healthcare. The Montgomery Sisam Architect seeks a new approach to address issues in healthcare design. Montgomery borrowed the urban theory of Jane Jacob’s The Great American Cities’ to emphasize how the street is a space in-between but crucial to wellbeing.

‘in-between space is the medium to connect the relation of inside-outside, the private, and the public within or in between institution and non-institution. Montgomery argues that this space left massive space for improvement and the probability to promote well-being. In my opinion, recalling the memory of personal experience and literature observation about occupants’ experience in the waiting room, most of it was unpleasant memories (Kearns 2020).

Montgomery also gave examples of how their practices stressed the importance of ‘in-between’ spaces, such as the porch (interaction inside-outside, freedom-controlled environment) and the courtyard and the gallery, which are non-clinical spaces.

hillips, Richard, Bethan Evans, and Stuart Muirhead. “Curiosity, Place and Wellbeing: Encouraging Place-Specific Curiosity as a ‘way to Wellbeing.’” Environment and planning. A 47, no. 11 (2015): 2339–2354.

The paper explores the possibilities of curiosity as a catalyst supporting wellbeing. Phillips refers to Atkinson about how place and wellbeing are closely related. Well-being is attached to the place, and the people interact with the space. Based on the Take Notice report of New Economics Foundations about the five ways to achieve well-being, Phillips argues that curiosity can be a medium to support this achievement.

The writing explores three case studies, creative gardening targeted for children, memory boxes targeted for dementia patients, and a photography project for the veteran. From these findings, curiosity emerges from the reception of senses toward a particular memory or emotion. The case study has many multi-sensory designs and activities. This could also lead to diverting attention, starting a standard communication, and creating a social engagement.

Schweitzer, Marc, Laura Gilpin, and Susan Frampton. “Healing Spaces: Elements of Environmental Design That Make an Impact on Health.” The journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.) 10, no. Supplement 1 (2004): S–71–S–83.

The writing seeks a design element (aesthetic enhancement) to reduce stress and anxiety and increase patient satisfaction. This could bring back unpleasant memories. There are also physical parameters such as personal space and sensory environment, including humor and entertainment. Some elements that could cause stress and disturb the patient include noises and negative smells (hospital odor).

Healing relationship is essential to feel connected to the staff and family. It includes intention, awareness, and intangible aspects of creating a healing environment such as a warm welcome, fostering connection, and participation

Bibliography

Anderson, Ben. “Affective Atmospheres.” Emotion, Space and Society 2, no. 2 (2009): 77-81. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.emospa.2009.08.005.

Bell, S. L., C. Phoenix, R. Lovell, and B. W. Wheeler. “Green Space, Health and Wellbeing: Making Space for Individual Agency.” Health Place 30 (Nov 2014): 287-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.10.005.

Broom, Douglass, “6 trends that define the future of health and wellness”, The World Economic Forum https:// www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/megatrends-future-health-wellness-covid19/

Duff, Cameron. “Atmospheres of Recovery: Assemblages of Health.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48, no. 1 (2015): 58-74. https://doi. org/10.1177/0308518x15603222.

Böhme, G. Atmosphere as Mindful Physical Presence in Space. Building atmosphere, OASE, (91), (2013), 21–32. Retrieved from https://www.oasejournal.nl/en/Issues/91/ AtmosphereAsMindfulPhysicalPresenceInSpace

Griffero, Tonino, and Marco Tedeschini. Atmosphere and Aesthetics: A Plural Perspective. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, 2019.

Grigoriou, Elina., and Richard. Francis. Wellbeing in Interiors : Philosophy, Design, and Value in Practice. Milton: RIBA Publications, 2019.

Hernandez, Rebecca Ory. “Effects of Therapeutic Gardens in Special Care Units for People with Dementia.” Journal of Housing For the Elderly 21, no. 1-2 (2007): 11752. https://doi.org/10.1300/J081v21n01_07.

Jouret, Jill. “A Healing Space.” The Lancet Oncology 13, no. 9 (2012): 866-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/s14702045(12)70406-0.x

Kearns, Robin A, Pat M Neuwelt, and Kyle Eggleton. “Permeable Boundaries? Patient Perspectives on Space and Time in General Practice Waiting Rooms.” Health & place 63 (2020): 102347–102347.