3 minute read

Blessings

fiction by Telisha Moore Leigg

Nothing’s secret long enough; nothing dies well. --Kwon

Advertisement

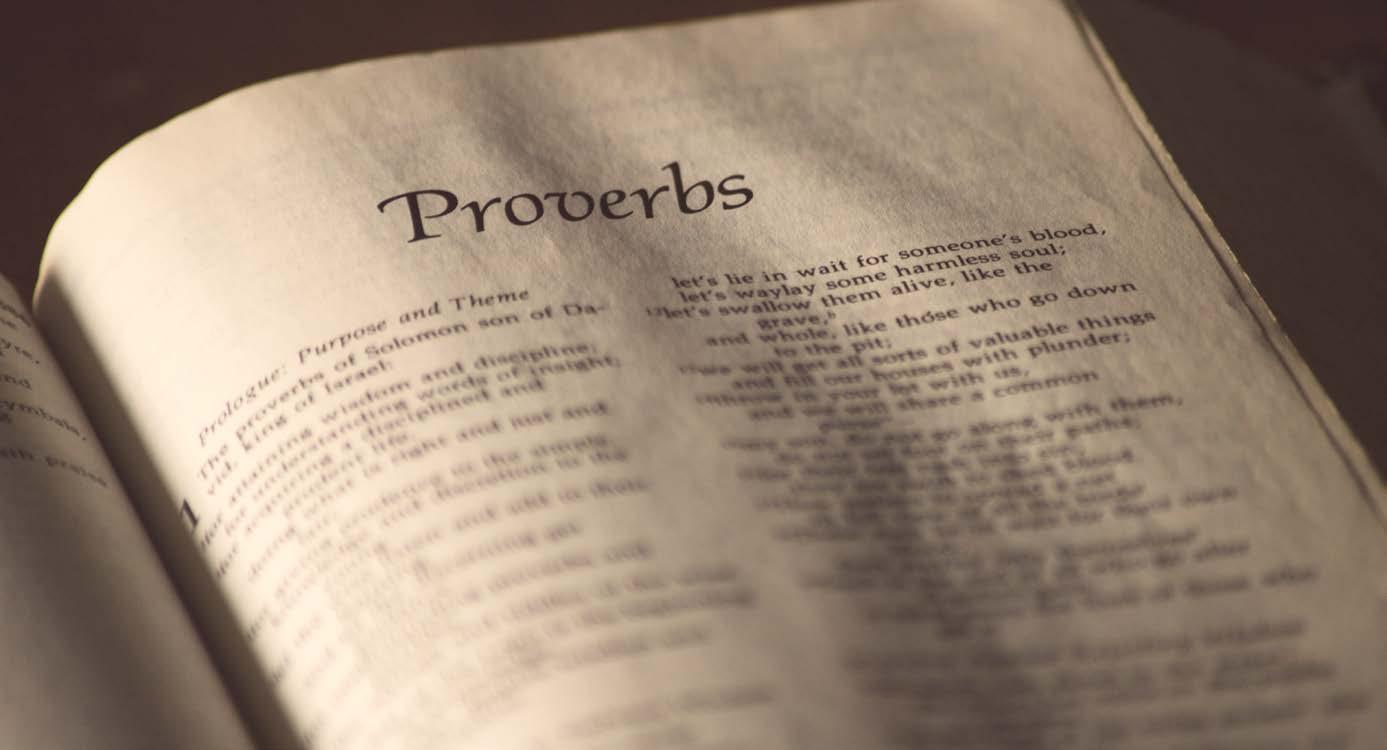

The old white man in the back of the mostly black congregation of Roland Street Grace Worship Center was not the anomaly; perhaps his stark and neat suit for the Sunday evening second service was. Services were usually more casual here, jeans, maybe a collared shirt. Part Bible study, part worship service, part homeless shelter, we were studying Proverbs that day in March, starting with that scripture about the beginning of fear and wisdom. It was too cold for air and yet not warm enough outside without a sweater; people sat a little chilly in the sanctuary, a converted old two-story grocery store. A baby whimpered in his mother’s arms, and she took him out while looking back at the white man on his own sitting on the last row of folding chairs. The service hadn’t started and was kind of quiet, with only Lilbit Russ (sixty years old if a day) playing stride piano to “Blessed Assurance,” his notes distant like rain before thunder. People alternately talked, prayed, and greeted each other with “Blessings” or “Blessings to you.”

I never knew them, Mandy Blue’s babies. I only knew they died alone, in a garage, probably crying, so young, and everyone thought

she would die too after that pain. With her mother and stepfather passed...we were all she had, me, Fallon, and my mother Mean Keisha. I take that responsibility seriously. I take it to mean something good for Mama Mandy. At almost twenty-seven now, I look at the old white man looking at me. I think nothing stays broken, nothing bad stays gone, nothing sad gets stolen away, but he should have stayed gone. There is a rhythm of rain on the tin roof.

I’m Kwon. I volunteer here, usually keep small things fixed, help with the free outreach meals, tutor the little ones in English, sweep up when needed. I’m behind the scenes, and I like that. But that night Sister Annette had a spring cold that deepened, and I had to lead the bible study for her. Glad it’s a Sunday because during the week I’m sometimes not here; I’m at home either grading papers or working on my doctorate. Old White Man looks at me. I say nothing. I turned the page to another scripture, started talking about kindness and how we need to love one another. The old man didn’t look at the booklet he held before him. He kept his eyes on me, steady.

I bet they gasped before they went to sleep, her Isabelle and Beau. I know they gouge her heart with their memories. She wouldn’t watch Aunt Fallen’s girls until they were older. And he never came to help her then, her father. I look at him now, her father. I often think what gives the world a dangerous grin? What’s dead is like a cello’s loose bow across the grain. Bruised sense. Low sounds of blood baying. He would do some hurt here, her father, Mama Mandy Blue’s daddy.

When I looked back there a second time, the old man was gone. It didn’t matter. I knew him and I knew he would be back. I should have picked up the phone then. But I didn’t. I told myself I wasn’t sure, when I was, and even if it were Mandy Blue Eyes’ daddy, what difference would it make? He had to be almost eighty now. Mandy Blue was nearing forty-five if not past it. It had been almost thirty years. I wouldn’t bring ghosts to her like rain in a rusty bucket unless I was sure.

Why’s he back now? I bet he’s dying. Well, aren’t we all?

Old Man came back about three weeks later in the soup line. He drank potato soup from the bowl, tore his donated barley bread with his left hand and the right side of his teeth. He sat alone, never mixing with the others. And he kept looking at me. And it was warmer now, almost ending April and soon to be May. And there was the old white man again, bent, with eyes sharp, fierce and light blue. And his hands curled on black-suited knees like an old falcon’s talons. And I was sure now.

“Blessings, Dr. Corinth,” I say as I sit down beside him on a folding chair holding a cup of coffee I didn’t even want. “Blessings to you,” he responds. He knows our ways now. I lean in. “Maybe you should leave and not come back.”