Religious festivals, post event spatialities and everyday life:

Kumbh Mela and the Simhastha Camp

SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT AND ARCHITECTURE

UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI

SHUBH SANKHLA

2022 - 2023

SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT AND ARCHITECTURE

UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI

SHUBH SANKHLA

2022 - 2023

SUPERVISORS : ROHIT MUJUMDAR & MILIND MAHALE

SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT AND ARCHITECTURE

UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI

SHUBH SANKHLA

2022 - 2023

This is to certify that the dissertation titled

“Religious festivals, post event spatialities and everyday life: Kumbh Mela and the Simhastha Camp” is the work of

Mst. Shubh Sankhla whose signature appears below as author.

The Author certifies that this is an original work carried out by the Author and is not paraphrased, or copied in whole or in parts (except for those statements a graphics mentioned along with references) or submitted in any form to any other institution for obtaining an academic degree.

The Supervisors whose names and signatures appear below confirm and certify that the above mentioned dissertation is the original work of the above Author; that it is carried out under their supervision; and that the work is of acceptable quality necessary for partial completion of the course to obtain the Bachelor of Architecture Degree.

The External Examiners whose names and signatures appear below confirm and certify that: they have evalusted the Author’s work in a Viva- Voce; and, the work is of acceptable quality necessary for partial completion of the course to obtain the Bachelor of Architecture Degree.

The Director whose name and signature appears below certifies that the Supervisors and External Examiners are appointed by the School of Environment and Architecture for mentoring and evaluating the above mentioned work. Based on the evaluation of the Supervisors and Examiners, the above work is acceptable for the partial completion of the course to obtain the Bachelor of Architecture Degree from University of Mumbai.

SUPERVISOR

NAME: Rohit Majumdar

DATE:

EXTERNAL EXAMINER

NAME:

DATE: DIRECTOR

SUPERVISOR

NAME: Milind Mahale

DATE:

AUTHOR

NAME: Shubh Sankhla

EXTERNAL EXAMINER

NAME:

DATE:

I would like to take this moment to express my deepest gratitude towards the few people who have pushed me to make this dissertation possible. Firstly, I would like to thank the School of Environment and Architecture, for helping me grow in the past five years, into a sensitive, reasonable and rational person.

Secondly, I am grateful towards all of the colleagues who willingly helped and supported me in my research. Rishabh Chhajer, Diwakar Motwani, Arnav Mundhada, your companionship, honestly and will, to always be there for me, whenever I needed criticism. Tushar Jhanwar, who with his resilience of hard work, motivated me always to be on my toes for newer ideas and thoughts.

Thirdly, I would like to thank my mentors Rohit Mujumdar, and Milind Mahale, for supporting and encouraging me to produce such a dissertation, and guiding me with their dedication and teachings to help me build this thesis. I also thank Prasad Shetty, Rupali Gupte, and all other faculty for tolerating my questions and helping me articulate a better self.

Additionally, I would extend my gratitude to my family. My parents Chhaya & Vijay, who never made me feel alone, even when I

was far from one. My sisters, Jui and Prachi, always check on my well being, and give me constant motivation and inspiration, to work better and accomplish my thoughts and goals. Oreo, to always love me, and greet me everyday with his presence to complete my day.

Bhoomi, your constant presence, and your determination to work harder and better everyday, has motivated me the most. Your help in building my thesis, and literally waking me up everyday, to be my rescue for all the days, I cannot thank you enough.

Lastly, I would like to thank all my colleagues and support from various encounters who have encouraged me to focus on my work.

What spatial opportunities do intense religious festival event spaces create during non-event times? At stake in this question lies the challenge to interrogate the celebratory narratives of temporal / ephemeral / pop-up architecture / kinetic city that have emerged from architectural research on religious festival event spaces in India, on the one hand, and to articulate conceptual tropes beyond those of “death” and “unproductiveness” to describe their post-event spatialities, on the other hand. The field for this study is the land reserved in the Development Plan of Nashik city for the Simhastha Camp, literally a space where sadhus camp for six months during the Kumbh mela. It is a designated space for living and celebrating cultural / religious practices that unfold during the Kumbh mela. Much of the land falls under private property ownership but it is regulated by the state through the Development Plan and Development Control Regulations (DCRs) that do not allow for the construction of new permanent structures, and through the provision of infrastructure like water supply, sewerage, roads and other essential infrastructure.

Of the numerous programs that exist within this camp space, I have chosen to study houses, nurseries, scrapyards, suppliers of festival and marriage decorations, and a street. The methods for each case differ

as interest is on the transformation of builtform : the scrapyard and decorator supplier have a similar type, hence they are studied through affordance of their type, the house is studied by comparing its form of life during and after the event through a timeline where extensions of the houses create different spatial experiences, the nursery is looked at how the land politics shapes the builtform to hide their house by building a shed over their house, and how the office and shops, operate with the same type of shed, lastly the streets are studied through how the residue of the event produces different spatialities where the city appropriate this residue to create new economies and leisure spaces. My analysis produces a biographic narrative of the Simhastha Camp through thick annotations of the transformations of the urban form and built form by organising them in a linear post-event timeline punctuated by the cosmological cycle of the religious festival event. The thick annotations are meant to develop a narrative of the land politics by focusing on the transformations in property rights (ownership / tenure), activities (post/ event), land claims, negotiations with development control regulations, aspirations of the owners, and the spatial opportunities and affordances that these spaces produce.

I advance five arguments through this thesis. First, since the development control regulations

do not allow for any permanent structures to be constructed in the designated Simhastha Camp precinct, owners, who initially were farmers, have been compelled to rent their property for the activities of the new service economy that provides opportunities for income generation. This transformation is also produced due to the fact that projects of infrastructure provisioning for the Kumbh mela on private property often reduce the fertility of the land.

Second, in the change from an agrarian to an urban services based economy, the builtform response to the DCRs has led to a widespread proliferation of ‘the shed’ as a new building typology on the land reserved for Simhastha Camp.

Third, the shed typology tactically responds to the aspects of temporariness and permanence. Its materiality and tectonics make it appear like a temporary structure that follows the DCRs but beneath its skin, it lends to the everyday consolidation of houses, work and life. For instance, the house expands using the shed; the labour house in the nursery hides by building a shed over a pakka house; the office and shop in the nursery also expands using the shed; the streets are claimed by makeshift tapris and mobile shops. This doubleness - the tectonics of the temporary and the consolidation of life - could offer significant learnings for architectural thought as

against the celebratory ideas of temporal / ephemeral / pop-up architecture / kinetic city, which picture a builtform that emerges during the event, and then dismantles and vanishes.

Fourth, in moving beyond the concepts of the temporal / ephemeral / pop-up architecture / kinetic city, doubleness draws attention to the analogies of the ‘veil’ and the ‘residue’ as tactics to consolidate builtform and life in the post event spatialities.

And fifth, my research makes a methodological contribution by pointing to the lacunae in studying the architecture and urbanism of religious event spaces in opposition to the everyday. It draws attention to the difference that a long duree, longitudinal study could make in developing thick descriptions of the ways in which the event folds into the everyday.

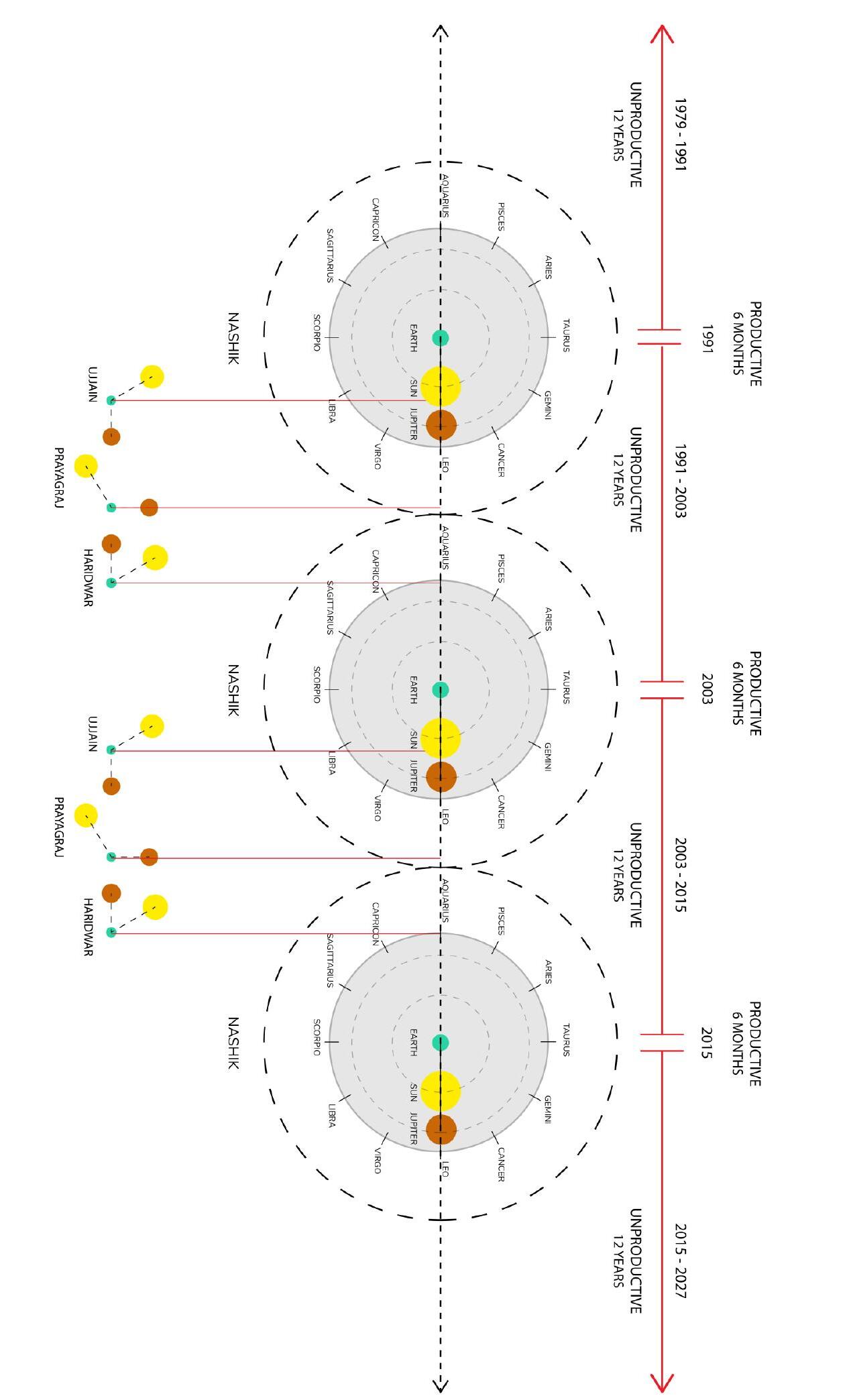

Fig:1.1 Cosmological cycle of Kumbh Mela.

Fig:1.2 Kumbh Mela Street photograph - 2015

Fig:1.3 Kumbh Mela Street photograph - 2022

Fig:1.4 Rahul Mehrotra - toolkit for ephemeral city

Fig:1.5 Rahul Mehrotra - affordances of toolkit

Fig:1.6 Part Development Plan of Nashik - 2001

Fig:1.7 Part Development Plan of Nashik - 2013

Fig:2.1 Diagram of Military camp.

Fig:2.2 Diagram of Refugee camp.

Fig:2.3 Diagram of Adventure camp.

Fig:3.1 Evolution of Nashik city, marking reserved land.

Fig:3.2 Samples of reserved land marked on reserved land.

Fig:3.3 Timeline of cosmological cycle.

Fig:4.1 Timeline of new urban services coming up.

Fig:4.2 Comparision of lifescapes in shed type.

Fig:4.3 Timeline showing consolidation of an agrarian house

Fig:4.4 Spatiality of house during and post event.

Fig:4.5 Timeline showing consolidation of a nursery.

Fig:4.6 Spatiality of nursery in 2022.

Fig:4.7 Timeline showing consolidation of a street

Fig:4.8 Spatiality of street during and post event.

Fig:4.9 Timeline showing different functions active on Simhastha camp space

Fig:4.10 Timeline showing consolidation of spatiality of all cases

Fig:4.11 Diagram of shed type.

Fig:4.12 Diagram of shed growing incrementally.

Fig:4.13 Diagram of shed acting as a veil.

Fig:4.14 Diagram of claiming of residual spaces.

2.

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

2.1

2.2

3.

3.1

3.2

3.3

3.4

A story in Hindu mythology tells us about how gods and asuras came together to churn out the nectar of immortality from the ocean. The nectar was contained in a “Kumbh”, which means an empty vessel. During the process four drops of this nectar fell into the four sacred rivers of Godavari, Shipra, Ganga, and the confluence of Ganga, Jamuna and Sarasvati, at the four sites of Nashik, Ujjain, Haridwar and Prayagraj, respectively. It is believed that pilgrims and sadhus visit these sacred sites to praise the gods and ask for forgiveness of their sins. As per Hindu astrology, the Kumbh Mela occurs when there is a specific congregation of Jupiter, Earth and Moon, which occurs every twelve years in each city. During each Mela, millions of hindu devotees come and visit the ghats of the sacred rivers and take a bath, to wash away their sins. The Mela is more than just a massive pilgrimage, it is a spiritual frenzy. No one knows the germination of this festival, but there are a lot of written and spoken stories across India. These stories are mobilized by various “Akharas” running across India. Akharas are religious institutes or monasteries who defend the religion by educating devotees into martial arts and ritualistic practices, who at the end become sadhus.Akharas are formed by highly influential men, who have millions of followers and devotees. During the Mela, the city provides land for these Akharas to

reside into these“unending landscape of tents”.

“There’s a blur of feet hurrying through ankle-deep mud. Millions and millions of them. Some in plastic sandals, others in rubber boots, many others in cheap city shoes, or trainers, or flip-flops, or brogues. Tens of thousands more are barefoot, some limping, others running. This sea of humanity is surging forward, relentless and unstoppable. Most of them have bundles on their heads. Each one is stuffed with rice and flour, pots and pans, blankets and bedrolls. Many have babies bundled on their backs or toddlers clutched tight to their chests. Eyes squinting into the bright winter sunlight, they are streaming in from all points of the compass towards the vast encampment. A sense of frantic anticipation and complete exhilaration unites them. As it does so, the unending torrent of pilgrims sets eyes on the glinting waters. It is the point where their journey ends just as it begins. This is the greatest gathering in human history, a multitude of one hundred million souls.”

The architecture of the Kumbh Mela has evolved through many years, and many forces and powers have shaped it into this.

As explained by Kama Maclean (2008), in the colonial state of India, large pilgrimages

have the potential to generate power, and they saw these as “powerful conduits of disease as well as news, rumors, sedition and eventually nationalism, and they consistently sought to control the pilgrimage.” The British had a different agenda with the Kumbh Mela, and considered them as “a potentially dangerous festival that demanded tight regulation and control, whereas for the latter it was a sacred sphere in which foreign interference was deemed intolerable.” Kama Maclean (2008). The festival still continues on the politics of regulation and control, where powerful institutes of the nation negotiate with the institutes of religion. There was an urge that emerged to control this frenzy. As these places of pilgrimage hold power, a very different kind of politics emerge in controlling this space of mass movement.

In 2015, Nashik hosted the Kumbh Mela. I grew up in this city to see it grow and expand, but as I witnessed the Kumbh Mela unfold, my perception towards the city changed completely. Nashik witnesses a lot of infrastructural changes to hold this massive carnival together. A lot of money is invested by the state to provide these facilities to the pilgrims. The city also benefits from this. Public infrastructure such as roads and buses undergo a lot of upgrades. Some of these infrastructure remains, and others dissolve after the mela. This experience has left many images of the city in my memory ranging from how the city scape changed itself to how my household used to function during the three months of high footfall. The schools remained shut for a few weeks, as transportation on roads were only limited to essentials.

During these days, I remember my father walking me from our home to the ghats every other day to witness this grand religious gathering. Out of these memories, the one that was most prevalent was of the walk within the sadhugram. For me, I had never seen this part of the city, even though it was in a close proximity to the city center. The streets were flooded with people, engaging in various activities within this designated area, which is uncommon to the everyday life of Nashik. The carnival

is a city, built to host a hundred thousand people and millions more. The walk went on for hours, as I saw the carnival unfold into public demonstrations, performances of bhajans, keertans, kathas, various groups/ akhadas engaging in storytelling of gods, large gathering tents for bhandaras and other religious cultural events. One could roam around the streets to engage with any of these activities, and visit akhadas which were connected through large streets. The city functioned as how a normal city would function, with its own set of clinics, surveillance, sanitation infrastructure, and a visitor center, all built only to last for three core months of the mela. The entire city is built on the idea of “dissolving” back.

In 2021, my mother took me back to Tapovan to buy plants for our home. The experience of space had changed. The hustle and bustle of the mela had vanished and only things remained were the infrastructure like street lights and wider roads. The cries of children, continuous repeating religious chants, millions of simultaneous conversations and tents are gone. It felt like the space “died”. It was stripped from all its characters and vibrant colours of the festival. The memories of the Mela, still were reminiscing in my head, and how the space did not justify what I thought it might have been.

But interestingly, after the Kumbh Mela ended, the space transformed itself and the city started to appropriate the spaces. My interest rose in how the space gets appropriated for this duration of 12 years. This interest grew not only because of its vicinity with my home but also because of its vicinity with the city. Being near the ghats of the river as well as highly connected to highways, the space holds a lot of potential, not only for residence but also for industries, but the space is especially reserved for the Sadhugram. This process will continue till the next Kumbh Mela. The idea of reservation of land with respect to an event at such a scale, where there are multiple parties and individuals involved, grew my interest in how the land shapes itself for its timeline. Mainly, during the non-event times, where the land finds itself different user groups and individuals to carry out different temporal activities. These activities are shaped by tradition, by nomads, by citizens, by regulations, by practice and also mainly by the event.

Fig:1.3 Kumbh Mela Street photograph - 2022

Fig:1.3 Kumbh Mela Street photograph - 2022

The idea of temporary is discussed in architecture perpetually. In the modern era, cities started to be theorized with the idea of permanence. Many architects started to critique this practice.

Rahul Mehrotra talks about how cities should be made with this idea of temporary kept in mind. He talks about it by studing the temporal nature of Sadhugram built in the Kumbh Mela of Prayagraj in 2013, and the Ganpati pandals that emerge everyyear in the city of Mumbai. Using this examples, he calls them the “pop-up city”, which is built for an event, by then dismantles itself and vanishes, absorbing itself in its surroundings.

Looking at this, the affordability of this city is due its toolkit of materials, and high coordination of state infrastrucutre. This toolkit consistes of bamboo, rope, nails, a cover material like tarpolene sheets and tadpatri. These materials built the aesthetics of this pop-up city, by forming “tents” as typology to cater to many functions in this city.

In a better understanding, this landscape essentiantially could be understood as a camp space, as it is also called as “Simhastha camp”. An “ephemeral megacity”, having its own logics of organising and production of saptiality.

But in his works, the land on which this megacity is constructed upon, is built on banks of the river. As the cosmological cycle suggests that the event takes place during the month of February, which means the water in the river resides, providing acres of land for the event to harness in the banks. Looking at this, the temporal city, has a clean slate to built on. The metaphor of “pop-up” remains valid due its tabula rasa of banks. Hence a climatical phenomenon affords such a city.

In modern architecture, cities are often theorised with the idea of permanence. Events then are part of the city where

this notion of permanence is seen to be broken. The aesthetics of these spaces are ephemeral, meaning the way we theorise cities need newer analogies. The need to understand this ephemeral nature of the city, temporal activities become ground to study its complexity, form and politics revolving around them. A concern that emerges is that cities are theorized with the idea of permanence, but there is a romanticizing of the temporary city as well which does not negotiate with land politics.

Unlike Prayagraj, in Nashik, the river banks are substantially smaller than the ones in Prayagraj, making the space unsuitable for the Mela to exist. Hence, a strategically chosen space is selected for it. Tapovan is an area in Nashik about three kilometers from the Ram Kund, where the Shahi Snan takes place. Tapovan is beside the river and is in close proximity to the old Nashik. As the city grew, Tapovan remained as an agricultural zone, until 2001, where the first reservation of land was announced by the state. The land allotted was 56 acres to begin with. The reserved land was published in the Development Plan of the city. Reserved land here means that the land is purely allotted for the Simhastha camp. No development on that land would be permitted, and any negotiations were not tolerated by the state. It is important to note that the state is doing this under political pressure from the religious institutes.

The next Kumbh Mela in 2015, required a larger parcel of land and it had much larger imperatives.

1. The reserved land exploded from 56 acres, to 300+ acres. A change in the DP in 2013, was introduced.

2. This reserved land was not acquired by the state, meaning the land is still owned by private individuals.

3. For the Kumbh Mela in 2015, the land

was forcefully taken by the government by the process of requisition (renting of land), and acquisition (buying of land) from these individuals.

4. The private owners had to give up on their parcel of land for the Kumbh Mela, but were allowed to live in their houses (if they had one)

The point where the private stakeholders came into the picture, the land politics of the space saw a shift. Meaning the private landowners could not “develop” their parcel of land. They have to abide by the regulations put forth by the state.

The growth of the reserved land created a larger political turmoil for the state and the land owners. The state being pressured by religious institutions, and the land owners pressured by the state. This generated the current land politics in the reserved land of Nashik. Thus, the event leads to such consequences and forms a different livelihood post event. The post event becomes a space to understand the nuances regarding the “temporary”.

Fig:1.6

Part Development Plan of Nashik - 2001

Fig:1.6

Part Development Plan of Nashik - 2001

Sadhugram, also known as the “simhastha camp”, is this city of “unending landscape of tents” (Tahir Shah, 2013), built within the span of a few months to host the mela. This temporary settlement needs a large infrastructural movement to function. All Kumbh Melas require the mobilization of various government bodies to approve and build this infrastructure. From laying drainage lines, to providing electricity connections to thousands of tents. As discussed by Diana Eck and Rahul Mehrotra (2015), in their book Kumbh Mela: Mapping the ephemeral megacity, “the Kumbh Mela takes form like a choreographic process of temporal urbanization, happening in coordination with environmental dynamics.” The city goes into the process of unfolding itself, and then again folding itself, generating a very temporary context. They narrowed down the city to its built materials : nails, bamboo, rope, and a skinning material like fabric, plastic or corrugated sheets. The materiality of the form of tents generates a carnival like atmosphere.

“On the surface, the tent city resembles something out of a military campaign. In addition to the pontoons and the neat rows of khaki tents, the main thoroughfares are laid with iron sheets so that vehicles don’t get stuck in the mud. There’s electric streetlighting, too, which bathes the camp in an

unnerving yellow glow through the hours of darkness. The lights are run by a series of mobile power stations, set up just for the Kumbh Mela. “ (Tahir Shah, 2013)

1. The military camp , as described by Michel Foucault (1978), is a diagram of surveillance, and power, where the practice of power is solely prescribed to the seat of power. It is a “shortlived, artificial city, built and reshaped almost at will”. For him, this idea of the military camp, pushed towards the urban development where cities were constructed in hierarchy of social class. Such a diagram of power was translated in many institutions, where continuous observation became the prime principle behind its design, neglecting its imperatives socially and politically.

2. Hannah Arendt in We Refugees (1943) , writes about the identity of a refugee: one “who has lost all rights, yet stops wanting to be assimilated at any cost to a newer identity”. A person who is displaced due to a certain crisis. Giorgio Agamben (1995), built on the works of Hannah Arendt (1943), says that refugees are ones who enter a “liminal status between citizen and outcast”. In his observations of the Palestinian refugee camps, he claims them as “sites of ‘bare life’ ”, where a person is deprived of their identity. The refugee camp becomes a “spatial mechanism of control and management”, which generates the politics of power, control, lack and suffering. The camp here not only generates spaces of control and management, but also a space which is constantly evolving by the inhabitants of them.

3. The form and configuration of the adventure camp is shaped through the ideas of leisure and exploration. Usually found in areas where it is inaccessible to the vehicles and away from the hustle and bustle of cities, these camps are vantage points to the popularized idea of living in wilderness. These are temporary settlements built for fun and gathering, of a specific class of people.

Fig:2.2 Diagram of Refugee camp.

Fig:2.2 Diagram of Refugee camp.

To understand the temporal nature of this space, the idea of a camp becomes helpful to device a frame to look at Simhastha camp. Camp helps us explore the ideas of pop-up, ephemerality, impermanence and its politics.

There are mainly three broad kinds of camps: Adventure camps, Military camps, Refugee camps. Other than the Simhastha camp, each of these camps have a sense of temporality embedded in them, but each of them function with different politics. The type of a tent comes out on top, as brings out many of its affordances. The same type produces many spatialities, bringing out the a question. So if the same type can afford different opportunities, the question arises on what are the architectural specificities that form this in a simhastha camp space?

To look at these specifities, a few operational concepts become important to understand the afterlife of this camp space.

• Event and the everyday: It becomes important to understand what is an event and what are its imperatives in everyday life that occurs in space. The event produces an experience for one, which breaks the everyday life. Here everyday life is one of the routines that is followed. The daily negotiations, transactions, experiences are of everyday life. As Henri Lefebrve, in his book The critique of everyday life, defines the everyday life as something that is related to all activities and takes into account all the differences and conflicts. It is a synthesis of these relationships which create the everyday experience for a human. Then defines the event as a social phenomenon of everyday life having two sides, “a little, individual, chance eventand at the same time an infinitely complex social event, richer than the many essences it contains within itself.”

In the case of the Kumbh Mela, the everyday and the event constantly build on each other, where there are overlaps and erasure. The event of Kumbh Mela, requires space that can host and expand for the span of 3 months in 12 years. The everyday space is the one that affords for this expansion to happen, and the event is the one that

constructs a system to do so.

• Afterlife of event space:

In the ordinary, the event becomes the show stopper, where everyone talks about it and starts to romanticize it, but what about the post event? The metaphors of afterlife, help me establish that there is an everyday that exists beyond the majorly discussed period of the event. The afterlife of the event space is usually introduced through sayings of “abandoned” and “vacant”, here I would like to explore beyond these parentheses, as the space holds this land politics even after the event. The afterlife of this particular event spans for twelve years. Within these years, an everyday life exists for the land owners, which is where it’s important to study the afterlife of the event.

• Spatiotemporal opportunities:

The afterlife of the event and the land politics would overlap to produce a spatial opportunity for landowners and people living in the reserved area. As the land becomes a burden for the owners, one would start to engage with them in practices which would have a timeline to it because of the Kumbh Mela. As the event would reoccur every twelve years, the everyday practices would be shaped around this criteria. Hence, the architecture of these practices would have an impact on the larger landscape of the reserved land.

The area of my study is to look at the post event spaces which become spaces for negotiations and transformation. The reserved land becomes the field for this enquiry. But as the reserved land spans across more than three hundred acres, it is necessary to scope down the field to manageable scale for this study. The reserved land or at least part of it, to the best of my knowledge, is stuck between two power structures. One from the DCR, and another from the judiciary. A court case looms around this place, which makes it difficult to get access to document any of the field, as one gets pushed out right from its entry. The land owners filed a case against the corporation after the 2013 Kumbh Mela for:

1. When the corporation took the land from the owners, they scattered 4ft deep gravel all across the fields. (The rationale behind this was to prevent marshy land during the Kumbh Mela, as it is celebrated during the monsoon.

2. The corporation laid infrastructure like underground drainage lines and water supply, on a contract basis which said that after the event ends, the pipelines would be taken back.

3. The corporation failed to manage this exercise, which meant that some of the underground pipelines along with their chambers still remain on site, making it

difficult to manoeuvre on site.

4. As the majority of the economy generated on site was through agricultural and pastoral practices, the gravel made it difficult for the land to produce a harvest. Farmers who could afford the removal of gravel, spent money from their own pockets to remove them.

This change in the landscape pushed the owners to further negotiations with the power structures and brought out a stay order from the court to continue with their daily practice, which again was of negotiations. This landscape of politics, for few, provided an opportunity to change a functioning economy from an agrarian to a urban services based, but the form of this was quite different.

Fig:3.1 Evolution of Nashik city, marking reserved land.

Fig:3.2 Samples of reserved land marked on reserved land.

- Old city of Nashik

1982 - Formation of NMC

1931 - First expansion

2003 - First reservation

1951 - Second expansion

Fig:3.1 Evolution of Nashik city, marking reserved land.

Fig:3.2 Samples of reserved land marked on reserved land.

- Old city of Nashik

1982 - Formation of NMC

1931 - First expansion

2003 - First reservation

1951 - Second expansion

To understand the spatiotemporal nature of space, these become important lenses to look from. Hence some of the questions that emerge are:

• Who owns the land?

• Who are the inhabitants/ tenants? What activities take place on the land during the Kumbh Mela?

• What activities take place on the land post the Kumbh Mela?

What spatialities have emerged on the land?

• What kind of opportunities emerge to shape activities and spatialities?

• What kind of negotiations emerge to shape activities and spatialities? What is the form of life that emerges in the post event spatialities?

• What are the aspirations of the owners and the tenants?

The broad categories of analysis that emerge are of:

• Ownership and Tenure

• Activities

Spatialities

Opportunities

• Negotiations

• Form of life

Aspirations

To study these analytical frameworks, one would need to study the timeline of space, and how the form of space changes over time. Time becomes the field to ask these questions. As more cases come forward, each case will generate a timeline which would help me study and understand the mechanics and logics of the temporary.

To draw the timeline, would mean that I would be drawing out the biography of the space and what politics take place in them. This will not only help me show how the timeline grew, but also help compare with the existing narratives of the temporary to further prove or disprove my argument.

4.5 Compiling field findings

1. As the economy in the land is changing, and the land is finding new rental user groups, who mainly are entrepreneurs ,a new typology is emerging in the landscape, which is of the shed. This type tactically negotiates between the development control regulations and the affords a permanent lifestyle. It neither fallls into the the idea of temporary or permanence. The shed affords a large hollow space, where things can be stored, hidden, can be extended at a cheaper cost.

2. The use of shed helps the house owner in case 2 to expand his house. He extends the house to host various other entrepreneurial urban services like a furniture scarpyard. The larger shed holds this, while the smaller sheds are rented to local enterprises which use them as storage warehouses. The house in itself hosts a shop which is the residue of the event itself. This spatiality does not vanish or disappear, rather it consolidates with the aesthetics of temporary.

New analogy: Increment

Fig:4.12 Diagram of shed growing incrementally.

Fig:4.12 Diagram of shed growing incrementally.

3. The labour house in the nursery ,case 3, shows the example of how these development control regulations affect the kind of living on the camp space during non-event. The negotiation takes place by building the permanent house inside the type of shed. This helps the labour live inside the house comfortablly without catching attention of the local municipal corporation who would break the house.

4. The streets become an example of how the residue infrastructure of the event is re-appropriated by the citizens of the city during the non-event times. These large footpaths surrounded by trees, afford the citizens to stroll or walk or use them as leisure spaces. As there are people who use this space in their routine, tapris and mobile shops start to claim spaces.

New analogy: Veil

New analogy: Residue

Fig:4.14 Diagram of claiming of residual spaces.

Fig:4.14 Diagram of claiming of residual spaces.

1. Since the development control regulations do not allow for any permanent structures to be constructed in the designated Simhastha Camp precinct, owners, who initially were farmers, have been compelled to rent their property for the activities of the new service economy that provides opportunities for income generation. This transformation is also produced due to the fact that projects of infrastructure provisioning for the Kumbh mela on private property often reduce the fertility of the land.

2. In the change from an agrarian to an urban services based economy, the builtform response to the DCRs has led to a widespread proliferation of ‘the shed’ as a new building typology on the land reserved for Simhastha Camp.

3. The shed typology tactically responds to the aspects of temporariness and permanence. Its materiality and tectonics make it appear like a temporary structure that follows the DCRs but beneath its skin, it lends to the everyday consolidation of houses, work and life. For instance, the house expands using the shed; the labour house in the nursery hides by building a shed over a pakka house; the office and shop in the nursery also expands using the shed; the streets are claimed by makeshift tapris and mobile shops. This doubleness - the tectonics

of the temporary and the consolidation of life - could offer significant learnings for architectural thought as against the celebratory ideas of temporal / ephemeral / pop-up architecture / kinetic city, which picture a builtform that emerges during the event, and then dismantles and vanishes.

4. In moving beyond the concepts of the temporal / ephemeral / pop-up architecture / kinetic city, doubleness draws attention to the analogies of the ‘veil’ and the ‘residue’ as tactics to consolidate builtform and life in the post event spatialities.

5. My research makes a methodological contribution by pointing to the lacunae in studying the architecture and urbanism of religious event spaces in opposition to the everyday. It draws attention to the difference that a long duree, longitudinal study could make in developing thick descriptions of the ways in which the event folds into the everyday.

Hence after this research, I ask the question for my design exploration is:

How can this idea of doubleness be explored in rethinking of entrepreneurial and housing practices which have this rhythmic nature of builtform?

Agamben, Giorgio. 1995. “We Refugees.” Symposium: A Quarterly Journal in Modern Literatures: 49:2, 114-119, https://doi.org/10.1080/00397709.1995.10733798

Certeau, Michel de. 2011. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven F. Rendall. 3rd ed. Berkerley: University of California Press.

Eck, Diana L. 2015. Kumbh Mela: Mapping the Ephemeral Megacity. Allahabad, India: Hatje Cantz.

Foucault, Michel, 1926-1984. Discipline and Punish : the Birth of the Prison. New York :Pantheon Books, 1977.

Gibson, James J. 1979. The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

MacLean, Kama. “Making the Colonial State Work for You: The Modern Beginnings of the Ancient Kumbh Mela in Allahabad.” The Journal of Asian Studies 62, no. 3 (2003): 873–905. https://doi.org/10.2307/3591863 , accessed 29 July 2022.

Maclean, Kama. Pilgrimage and Power: The Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, 1765-1954 (New York, 2008; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Sept. 2008), https://doi.org/10.1093/ acprof:oso/9780195338942.001.0001 accessed 29 July 2022.

Shah, Tahir. 2013. The Kumbh Mela: Greatest show on Earth. London: Secretum Mundi Publishing.

TED. “The architectural wonder of impermanent cities | Rahul Mehrotra” Youtube video, 4:47. August 30, 2019. https://youtu.be/Kc6hkHGHQQc

TED. “The architectural wonder of impermanent cities | Rahul Mehrotra” Youtube video, 4:58. August 30, 2019. https://youtu.be/Kc6hkHGHQQc

Tschumi, Bernard. 2004. Event-Cities. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.