9 minute read

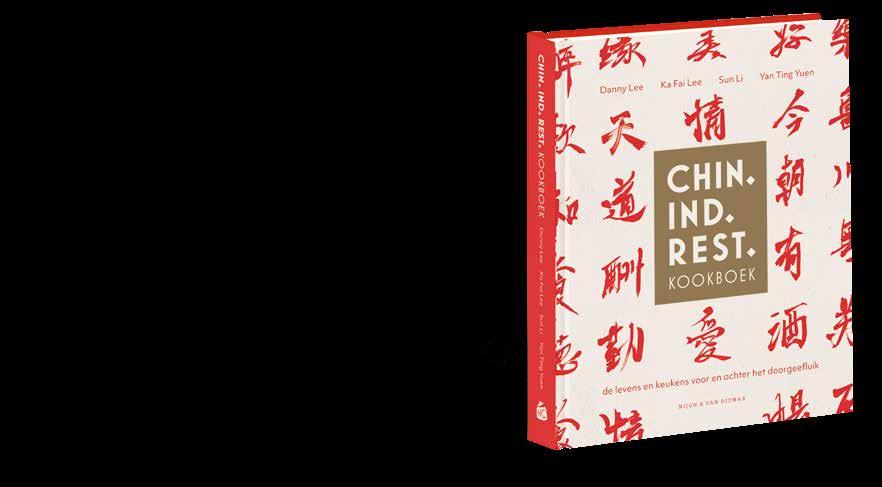

CHINESE INDONESIAN RESTAURANT COOKBOOK

The lives and kitchens in front of and behind the serving-hatch

For more than seventy years Chinese Indonesian restaurants have been a widespread notion in the Netherlands and Flanders. Who doesn’t have childhood memories of the local Chinese restaurant? In fact, in 2021 the Chinese Indonesian restaurant culture was added to the inventory of intangible cultural heritage in the Netherlands.

In Chinese Indonesian Restaurant Cookbook all classics of the Chinese Indonesian restaurant are recorded, from roast pork to perfect chow mein, egg foo yong and sweet and sour chicken. But also, the recipes from behind the serving-hatch are in the book: what does the kitchen staff eat, which diches did they take with them from the east and do they like to cook at home?

Based on the family chronicle of the owners of restaurant Fook Sing in Amsterdam the authors explain the history of Chinese Indonesian restaurants in the Netherlands. Stories of other restaurants throughout the country are shared as well. Chinese Indonesian Restaurant Cookbook is a beautiful and tasteful reference work and an ode to Chinese Indonesian restaurants.

Chinese Indonesian

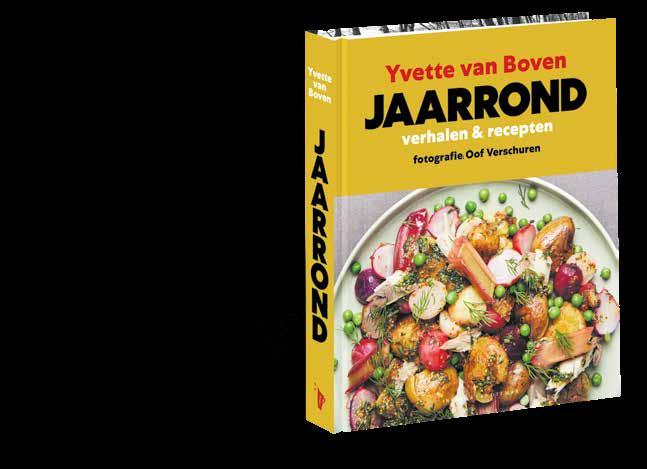

Yvette van Boven is a culinary writer, illustrator and TV presenter. She wrote numerous successful cookbooks, including Home Made, Home Sweet Home, Home Made Basic and Van Boven in het wild (Van Boven in the wild), that were translated into English, French, Spanish and German. Three times already she won the election for Gouden Kookboek (Golden Cookbook). Apart from her books, Yvette is also known for her TV programmes De streken van Van Boven and Koken met Van Boven, her weekly columns for Libelle and Volkskrant Magazine and the culinary podcast Etenstijd! with co-host Teun van de Keuken. The illustrations and design for her books are of Yvette’s own hand. Her husband Oof Verschuren is responsible for the beautiful photographs.

YEAR-ROUND Stories & recipes

Every weekend Yvette van Boven cooks a recipe for krant Magazine, mostly with vegetables, sometimes with fish and only once in a while with a bit of stray meat, or a savoury or sweet baking – just what she fancies, as long as the ingredients are in season. So don’t expect fresh tomatoes or strawberries in winter, but an unexpected preparation with kale, brussels sprouts or celeriac. She always tries to come up with dishes that are doable for anyone, without too much of a fuss, but special all the same. This way you will learn that everyday ingredients can have many – even unfamiliar –preparations.

Each recipe is accompanied by a column: an atmospheric description, a small observation or a short story from Yvette’s own life. This will immediately give you an appetite for the recipe on the page next to it. Also, each recipe come with a garnishing tip, as Yvette obviously doesn’t throw away anything. Every scrap can make something new. She always tries to surprise her readers with new ideas. Which will make you a better cook.

A new book by the winner of the culinary prize among others, national daily newspaper de Volkskrant After stays in Moscow, Berlin, The Hague and Washington she now works and lives with her family in Amsterdam. For years Sylvia wrote a weekly cooking column in the culinary section in de Volkskrant and she is the author of successful cookbooks.

Het Gouden Kookboek 2022 (The Golden Cookbook).

Rijst

In mijn jeugd heerste er over rijst een opmerkelijk misverstand: die moest droog zijn, met losse korrels. Dat effect bereikte je met Lassie Toverrijst, die trouwens nog steeds bestaat. Die droge, losse korrels smaakten naar niets, en de structuur was... droog en los. De korrels vielen van je vork, tenzij je er een hoop saus overheen gooide, wat de meeste mensen dan ook deden. Mijn moeder niet, trouwens. Die had het geloof ik niet zo op saus.

Tip!

De afhaal-/bezorgchinees/-thai/-indiër geeft altijd VEEL TE VEEL witte rijst. Meestal blijven er hele bakken over. Die kun je de volgende dag opbakken, of in de vriezer schuiven voor barre tijden.

Sylvia Witteman

Cooking tips for those who can’t even fry an egg

Poetry is like cooking: ‘Chuck it all in, is a way to begin,’ says poet Riekus Waskowsky. That is so true. Sylvia grew up as a frustrated foodie in the culinary vacuum of a family that mostly ate potatoes, vegetables and meat. Nevertheless, or perhaps because of that, she developed a love for cooking and eating that grew even stronger during her poor college time and her stays in various foreign countries.

Soep

Van alle goedkope gerechten is soep wel de allergoedkoopste. Soep kost bijna niets. Denk aan het stokoude verhaal van de hongerige soldaat die in een dorpje terechtkwam waar niemand van de gierige bewoners hem iets te eten wilde geven.

Hij ging op het dorpsplein zitten, maakte een vuurtje en zei hardop: ‘Nou, dan kook ik wel stenensoep.’ De omstanders lachten hem uit.

Je kon toch geen soep koken van stenen? Maar de soldaat kookte een pan water, gooide er een paar kiezelsteentjes in, roerde, proefde en zei:

‘Heerlijk. Alleen een paar stukjes ui erin zou wel lekker zijn.’ tip

HANDIG Ieder mens verdient een rijstkoker Zo’n ding kost 20 euro en het is werkelijk een feest.

De afhaal-/bezorgchinees/-thai/-indiër geeft altijd VEEL TE VEEL witte rijst. Meestal blijven er hele bakken over. Die kun je de volgende dag opbakken, of in de vriezer schuiven voor barre tijden.

‘Soep kost bijna niets.’

A

(de Sättigungsbeilage, verzadigingsbijlage, zoals de Oost-Duitsers de koolhydraat-component van de maaltijd ook alweer zo droog noemden) vonden mijn broertje, zusje en ik er dus niet veel aan. We bewaarden de rijst daarom liever voor het toetje: dan mochten we er boter, suiker en kaneel door roeren. Daarmee kon je je goed volmetselen en het was heerlijk. In de jaren 70 gebeurde er iets vreselijks. Mijn moeder, bevangen door reformideeën, schakelde over op bruine rijst. Dat was gezonder, heette het. Vrijwel wekelijks kregen we een door haar bedacht, ‘hukkie smukkie’ genaamd gerecht, waarin de bruine rijst met rul gehakt en seizoensgroente dooreen werd geroerd. Een tragische, zompige variant van nasi. Ik vond het nog best lekker ook, want we waren weinig gewend. Maar met de witte rijst met boter, suiker en kaneel was het afgelopen, en dat verdroot me zeer. Toen ik begin jaren 80 het huis uit ging had rijst voor mij afgedaan. Er bestond inmiddels pasta, dus wat zou je nog tobben? Pasta was lekker, goedkoop en het mislukte nooit. Pas veel later, toen er een zekere pastamoeheid over de wereld neerdaalde, ben ik rijst 13 weer gaan waarderen. Maar geen droge, losse korrels. Die wil ik nooit meer eten. En ook voor boter, suiker en kaneel zijn betere landingsba- nen te vinden dan rijst. Basmatirijst, die is lekker. Niet droog, los en saai, maar zacht, veerkrachtig en een klein beetje kleverig. Ieder mens verdient een rijstkoker. Zo’n ding kost 20 euro en het is werkelijk een feest. Er zit een maatbekertje bij dat je onmiddellijk kwijtraakt, maar dat maakt niet uit. Je giet water bij de rijst tot het één vingerkootje boven de rijst staat en dan komt het vanzelf goed. Rijst is zelfs een van de weinige spijzen waarbij het geen ramp is als je het zout vergeet. Probeer dat eens met pasta: als je die kookt in ongezouten water is het werkelijk niet te vreten, al strooi je er na het afgieten nóg zoveel zout over. Rijst maak je altijd veel te veel. Niet alleen omdat je geen idee hebt hoe enorm de korrels uitzetten, maar ook expres, omdat je dan de volgende dag gebakken rijst kunt maken, een van de lekkerste en goedkoopste gerechten die er bestaan. Zelfs als je nooit rijst kookt, omdat je daar te lui voor bent, kun je nog gebakken rijst eten. De afhaal-/bezorg-chinees/-thai/-indiër geeft altijd veel te veel witte rijst. Meestal blijven er hele bakken over. Die kun je de volgende dag opbakken, of in de vriezer schuiven voor barre tijden. Nasi of gebakken rijst kún je niet eens maken van versgekookte, nog warme rijst. Dan wordt het niet krokant met bruine korstjes. Dus oude, koude rijst is je beste vriend.

As a self-taught cook she learned the tricks of the trade with ups and downs and a lot of improvising, but always without a fuss. Through a cooking column in this led to a number of popular cookbooks, such as met Sylvia Witteman

Witteman explains in her familiar jocular no-nonsense way to every beginner what it really is all about in the kitchen, and especially: how it is done. Comprehensible for anyone, from the fresh student in lodgings to the just divorced pensioner who all of a sudden finds himself alone behind the stove and wondering: ‘Is this water boiling?’

P rompt kwam er iemand een ui brengen,die in de soep ging. Weer proefde hij en zei: ‘Perfect. Alleen een worteltje erbij zou het nóg iets lekkerder maken,’ en daar kreeg hij al een worteltje. Zo ging het door, met een restje spek, een paar aardappelen, een lepeltje zout; en uiteindelijk was de soep klaar. Hij deelde hem met de dorpsbewoners en iedereen was het erover eens dat stenensoep de állerlekkerste soep ter wereld is. Gelukkig gaat het ook zonder gierige dorpsbewoners of kiezelstenen: in plaats daarvan hebben we tegenwoordig bouillonblokjes, die bijna even goedkoop zijn als kiezelstenen. Ja, je kunt ook zelf bouillon trekken van kippen- of koeienbotten en dat kost ook niets, maar daar moet je maar net zin in hebben. Moeilijk is het trouwens niet: gooi een runderschenkel of ’n paar kippenpoten (of het karkas van een afgeknaagde gebraden kip) in een pan koud water, met wat worteltjes of een winterpeen, een stengel bleekselderij (zo’n harde, taai aan de buitenkant, die niet lekker is om te stoven) een doormidden gesneden ui (gewassen, maar met schil en al, dat geeft kleur) een takje tijm, blaadje laurier, en als je ze hebt wat peterseliesteeltjes

(of een peterseliewortel). Breng alles op zacht vuur aan de kook en laat het een halve dag héél zachtjes trekken. Niet koken dus. Neem zo’n sudderplaatje. Doe de bouillon door een zeef. Nu kun je er zout bij doen, maar ik gebruik meestal een groentebouillonblokje, dat is hartiger en lekkerder. Waarom geen kippen- of rundvleesbouillonblokje, denk je nu, maar die smaken wel heel erg naar... bouillonblokjes. En het hoeft dus niet, want je bouillon smáákt al naar kip of rundvlees; dat groentebouillonblokje haalt die smaken een beetje op zonder te overheersen.

Wat mij lang weerhouden heeft van zelf bouillon trekken is het gelul dat je er altijd bij krijgt, in kookboeken. Afschuimen, zeven door een ‘fijne doek’, ‘klaren’ met eiwit, dit alles met het tamelijk bespottelijke oogmerk een ‘heldere’ bouillon te krijgen.

Net of dat wat uitmaakt! Ja, als je in een restaurant zit en 12 euro betaalt voor een consommé (let op, die komt weer helemaal terug, voorspelt uw trendwatcher) dan moet die er ook perfect uitzien.

Maar voor de soep die je thuis eet is al die aanstellerij nergens voor nodig. En als er peulvruchten of aardappelen in je soep gaan, zie je het verschil zelfs helemaal niet.

Onno Kleyn is a well-known wine and culinary journalist. Since 2005 he’s been writing the wine section on Saturday for Volkskrant Magazine and he is the author of over forty books.

Wine By Kleyn

Stories for the wine lover

Wine is a magic drink, each bottle a story written in liquidity. One glass is enough to take you on a journey to other regions, to memories and dreams for the future, to better seasons. This book is an account of a journey through life, from Onno Kleyn’s first encounter with European wines to an idea of what the future of wine will look like. It encompasses stories, anecdotes and adventures, but also a lot of infor mation – you may even learn something from it. He mixes philosophy, ponderings and information to a very tasteful whole. Wine by Kleyn

Raghenie Bhawanie is a culinary writer and communications strategist. For Het Parool she writes columns about small food adventures in the big city and she posts food video’s on Instagram (@raghenieb). Her search for quick, simple and tasty recipes with flavours she is acquainted with brought her back to Surinam, the country where her parents were born and bred. There she learned about (centuries-old) cooking techniques, the use of vegetables and herbs and combining unusual Surinam ingredients from the different communities and satisfied her curiosity for the vegetables the country boasts. At home she develops recipes with Surinam flavours and Dutch vegetables or experiments with anything green from the Surinam grocer’s.

Raghenie Bhawanie

MADAME JEANETTE Quick Surinam vegetable dishes

Madame Jeanette will forever change the way you think about Surinam food. For who says that meat and fish should always be the main part of good Surinam food? Raghenie’s innovating but simple vegetable recipes are quick, easy and spicy. With this cookbook you will discover the culinary foundations of the melting pot that is Surinam cuisine. Take a deep dive into the Hindustani, creole, Javanese and Chinese influences that add colour to Surinam cuisine, with the by every Surinamese loved madame jeanette as the connecting factor.

With stories, ingredients and recipes for the best-known Surinam dishes – like roti, saoto, tjauw min moksi and brown beans with rice – Raghenie explains how the flavours of the different cuisines are built up. Subsequently she gives Surinam vegetables the star part they deserve and shares new recipes with local Dutch vegetables that go together perfectly with the different flavour profiles that Surinam boasts.