A COLLEGE FOR EVERYONE

SALT LAKE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

SALT LAKE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

A COLLEGE FOR EVERYONE

INQUIRY METHOD

(2015) “Inquiry Method,” Lisa Bickmore’s first convocation poem, came to her one late summer’s evening while she and her husband were walking past a sculpture called “Sky Grass,” which stands outside the Science and Industry Building. “The grass blades are opalescent, they sparkle with color when the sun hits them, and they’re reflected in the giant glass wall of the building,” says the college’s first poet laureate. “It’s beautiful. And I’m just walking on campus with my husband and thinking about what students would be doing in the few days before classes start.”

In the evening there was no one here, no groundskeeper nor teacher nor analyst just one woman with her dog, and us, walking around. The failing light just caught the Sky Grass’s blades, so that it in turn could reflect its blue; we saw the dry outline on the sycamore leaf. Buildings shut up, the sun gilding their glass. Canal water on the northern edge gliding west, away from the river. When does any story start? Tomorrow, the hour appointed for beginning arrives, the ritual with which we comply, upon which we are fixed: the noise we make of beginning, obscuring the chance-composed music of a thousand quieter commencements: they will arrive on that day, each from her own neighborhood, family, circumstance. She will have arranged for her shift to begin when her two classes end. He will have taken his little boy to daycare. She wants to go to law school. He wants to farm as his father did, but in a better way. Another holds hope like a small amulet he dares not show anyone. For some, it’s a murmur, song made of a laptop opening, the retrieval of a pen, the unzipping of a backpack. The fermata, just before a teacher walks in, uncaps a marker, writes something on a whiteboard and turns to speak her name. When does it begin,

the scraping together of money, the desire powering each arrival, the hazard of effort and aim and will for a barely trusted future? You walk here too, just before the sky gets dark, in the quiet fields crossed by walkways, lined with trees, heat still rising from where it has soaked into the very earth. If you listen closely, you can hear it already, the beautiful and difficult hum of work underway, in a thousand distinct modes: we may call this, this place, a beginning, but it is not the first, nor will it be the last, incident in the record: and if you listen you can hear their accounts, a minim of each single song: the clocks in the classroom are not yet ticking, or at least we can’t yet hear their driving measures: for now, we only sense the soon to arrive, their still potent dreams as yet unspoken — or unspoken to us. When do their stories begin, we ask, and I will tell you: all stories have always already begun, but they also always begin now.

LISA BICKMORE SLCC POET LAUREATE 2015–2019 UTAH POET LAUREATE 2022–PRESENT

prologue ONE IN A MILLION

A FOREVER STUDENT

Natalie Kaddas smiles when asked how she got to be the boss of Salt Lake City plastics thermoformer Kaddas Enterprises Inc. “It’s been quite a journey,” the CEO admits. “I probably wouldn’t be here had I not decided as an 18-year-old kid to sign up for courses at Salt Lake Community College. SLCC is a big part of my story, because I keep going back. I’m kind of a forever student.”

Like many high schoolers, Kaddas had no clear idea what she wanted to do after she graduated. To her father, a union electrician, the answer was simple: get a job. It was 1990. At the time she had a steady boyfriend with a good career of his own. “You’ll get married, settle down and have kids soon enough,” her father told her.

Kaddas wasn’t ready for that, although her alternatives weren’t clear. “A lot of the women in my life didn’t work,” she notes. “Besides, I wanted to travel.”

Her boyfriend (now husband) Jay Kaddas suggested she check out SLCC. He’d studied architectural drafting and electronics there in the 1980s when it was still called Utah Technical College, and he was putting the skills he’d learned to good use in the family business. “They offer all kinds of programs. There’s bound to be something that interests you.”

The idea of college hadn’t occurred to her. “It wasn’t talked about when I was growing up,” she says. “Mom and Dad didn’t encourage me to go to college. Why would they? Neither of them went.” When Kaddas decided to enroll at SLCC, her parents supported her … up to a point. “But they didn’t have the bandwidth to help me, and frankly they didn’t see the value in it,” she says. Common challenges for first-generation students then as now.

“Going to SLCC really opened my eyes. Most importantly, it showed me there were options —

NATALIE KADDAS BEGAN HER COLLEGE STUDIES IN THE TRAVEL AND TOURISM PROGRAM, THENdifferent paths I could take,” says Kaddas, who enrolled in a travel and tourism course.

That first year, the class went on a field trip to Marriott Hotels, the international hospitality company. Kaddas was impressed. “They were a well-known organization in the travel industry with some Utah roots,” she says. “And I loved the environment there. When we toured, I thought, ‘This is someplace I can see myself working.’”

She applied and was hired full time. “That never would have happened if I hadn’t taken that course,” she says, adding that it was her first “grown-up” job. “To me it was a really big deal.”

Over the next 15 years, her career at Marriott soared, and she rose to head up a department.

“I loved every minute of it,” she says. “And I got to travel the world.” In all the excitement, she didn’t forget SLCC. “I went back several times to take part-time classes in marketing and business management. What I love about the college is the breadth of classes they offer. I can go for what I need at the time I need it.”

went to SLCC to bone up on bookkeeping. At first, all went well, but the timing was bad. That year, America and the world plunged into the Great Recession. Business at the coffee shop dwindled, and Kaddas needed a new source of income.

Like many manufacturers, Kaddas Enterprises was hit hard by the economic downturn. “My in-laws, Carol and John Kaddas, started the company in 1966 in their kitchen oven,” she says. “Thermoforming is basically the art of heating up plastic and pulling it over a mold. When they won a contract to make components for Boeing, things really took off.” By the 2000s, the plastics company had grown from a mom-and-pop operation into a flourishing small business creating industrial applications for the utility, aviation and transportation industries. Then came the crunch.

the workforce was excellent at manufacturing products on time and on budget, but their customer communications needed work. “That was my skill set: taking care of people. For example, instead of shying away from supplychain challenges, we addressed them head on and said, ‘Okay, here’s what we’re facing. How can we work through this together?’ That way you build trust, credibility and loyalty. Once we started to focus on making customers happy, things really turned around.”

And then some. When she joined the company, net revenues were just over a million dollars a year. A decade later, Kaddas Enterprises was doing twice that in a month.

an answer,” she says, adding that she pulled out all the stops in her application. “I was part of the very first cohort from Salt Lake City, and it changed my life. It was truly transformational.”

Among other things, it gave her a network of business owners who share her challenges.

Since she took the course, Kaddas Enterprises has grown in dramatic fashion.

and production employees,” she explains. “Before they even hit my shop floor, they spend a week at Salt Lake Community College on shop safety, shop training, power equipment — the works.” The college proudly honored her in 2019 with its Distinguished Alumni Award.

STRONGER TOGETHER

TROUBLE BREWING

In 2008, Marriott wanted to post her to a different city, and Kaddas decided to quit. “I took the leap into entrepreneurship,” she says.

“I opened a coffee shop, which was a lot of fun.”

She learned there were many things she didn’t know about running a business, so back she

“My mother-in-law, who was ready to retire, was running the company at the time,” Kaddas says. “She’d done a fantastic job building it, but it was an uncertain time economically and that made everyone fearful. They had invested everything in the organization.”

Kaddas came in as CEO. “Talk about how the struggle to survive focuses the mind,” she quips. “I didn’t know anything about manufacturing. My background was in hospitality and customer service.” She found

In 2013, the lifelong learner turned to SLCC again. “We were having some success,” says Kaddas, “but I’d reached a point where I felt I needed something to help me take the company to the next level.” That something was SLCC’s Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses program, a 12-week curriculum offered to select entrepreneurs. SLCC is one of only 13 community colleges in the country offering the unique business education program.

“I heard about the Goldman Sachs program and was determined to take it. It’s very competitive, but I was not going to take no for

“Revenues, net profit, employees, capacity, capability — all have skyrocketed,” she says.

“I even have an independent board of directors.”

Thanks to Kaddas and the knowledge boost she got from the Goldman Sachs program, the company found that new level — just in time to take its products to the international market.

She even caught the eye of President Barack Obama, who in 2016 invited her to represent small businesses at a private dinner with German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

And her relationship with SLCC continues to this day. “I’m now partnering with the college on new-hire training for our machine operators

Looking over the different phases of her life, Kaddas feels great gratitude. “SLCC has always been there for me when I needed it. I’ll be back again, for sure. I feel like it’s truly embedded in my journey.” Just as it is rooted firmly in the communities it serves.

Kaddas’s is only one of many thousand SLCC stories. Stories that began when a tiny fledgling vocational school opened its doors in 1948 in a rented former laundry with a few hundred students — and almost didn’t make it to its sophomore year. Look at it now. With some 50,000 students, 10 campuses and robust offerings online, SLCC has become one of the largest and most diverse institutions of higher learning in Utah.

“SLCC HAS ALWAYS BEEN THERE FOR ME

WHEN I NEED IT. I’LL BE BACK AGAIN, FOR SURE. I FEEL LIKE IT’S TRULY EMBEDDED IN MY JOURNEY.”

PART 1 A SCHOOL OF VOCATIONS 1948–1978

“THE SOCIETY WHICH SCORNS EXCELLENCE IN PLUMBING BECAUSE PLUMBING IS A HUMBLE ACTIVITY, AND TOLERATES SHODDINESS IN PHILOSOPHY BECAUSE IT IS AN EXALTED ACTIVITY, WILL HAVE NEITHER GOOD PLUMBING NOR GOOD PHILOSOPHY. NEITHER ITS PIPES NOR ITS THEORIES WILL HOLD WATER.”

DR. JOHN W. GARDNER FORMER UNITED STATES SECRETARY OF HEALTH, EDUCATION AND WELFARE

chapter one THE STARVATION YEARS

GREAT OAKS FROM LITTLE ACORNS

The old Troy Laundry stood at 431 S 600 East, barely a mile from the downtown center of Salt Lake City. Its two main buildings stretched almost half a block; behind them stood a disused old hayloft and stables from the days when the laundry made horse-drawn deliveries. In all, the property covered 3.65 acres.

“I guess we could convert the hayloft into classrooms and the stables into welding and auto body shops,” mused Howard Gundersen as he surveyed the setting. His companion, Jay Nelson, nodded. “We could fill in the manure troughs and use the horse stalls as welding booths.”

It was 1948. Utah’s State Board for Vocational Education had acquired a lease with a buy-out option on the Troy Laundry building to house the Salt Lake Area Vocational School (SLAVS). In February that year, the board had appointed Gundersen to set up and run the new school. Nelson was one of his first hires as treasurer/ registrar. The two had worked together during World War II in Utah’s War Production Training School program, which Gundersen had directed.

Arising from an urgent need for skilled labor during the war, the program was part of a nationwide initiative that led to the establishment of adult vocational schools across America, including in Utah and the Salt Lake Valley — the University of Utah and West High School both offered vocational training. With the end of the war, the program’s federal funding dried up, but in Utah and other states, the need for vocational training continued, fueled in part by the veterans flooding back home in search of jobs. When the U of U ceased offering vocational programs, and after several years West High School lost its funding, Salt Lake Valley was left with no place for would-be vocational students to go.

THE TROY LAUNDRY MADE WAY FOR THE NASCENT SALT LAKE AREA VOCATIONAL SCHOOL (FORERUNNER OF SALT LAKE COMMUNITY COLLEGE). IN 1948 ITS HAYLOFTS BECAME CLASSROOMS, ITS HORSE STALLS, WELDING BOOTHS. TODAY, A MALL STANDS ON THE SITE.

THE TROY LAUNDRY MADE WAY FOR THE NASCENT SALT LAKE AREA VOCATIONAL SCHOOL (FORERUNNER OF SALT LAKE COMMUNITY COLLEGE). IN 1948 ITS HAYLOFTS BECAME CLASSROOMS, ITS HORSE STALLS, WELDING BOOTHS. TODAY, A MALL STANDS ON THE SITE.

IN 1948, UTAH’S STATE BOARD FOR VOCATIONAL EDUCATION NAMED HOWARD GUNDERSEN (LEFT) PRESIDENT OF SLAVS.

HE ACCOMPLISHED THE IMPOSSIBLE, OPENING THE COLLEGE ON SCANT RESOURCES, BUT WAS GONE WITHIN A YEAR. HE WAS REPLACED BY ONE OF HIS FIRST HIRES, JAY NELSON (RIGHT), WHO WOULD RUN THE INSTITUTION UNTIL 1978.

WITHOUT JAY NELSON’S DOGGED DETERMINATION TO BRING VOCATIONAL TRAINING TO THE COMMUNITY IN THE EARLY YEARS, THE SCHOOL WOULD NOT HAVE SURVIVED — AND THIS BOOK WOULD NEVER HAVE BEEN WRITTEN.

“THE NEW PRESIDENT [HOWARD GUNDERSEN] HAD GAINED THE REPUTATION DURING THE WAR OF GOING FORWARD AT FULL STEAM.”

ON SEPTEMBER 14, 1948, THE COLLEGE OPENED TO 246 STUDENTS IN 14 CLASSES.

BY YEAR’S END, THE STUDENT BODY HAD SWELLED TO 1,387 IN A MIX OF DAY PROGRAMS AND NIGHT CLASSES. SHOWN HERE: STUDENT BARBERS ON THE TROY LAUNDRY CAMPUS IN 1957.

In 1947, the State Vocational Board and numerous lobby groups succeeded in persuading Utah’s legislature to fund an adult school to meet the community’s need. The lease on the Troy Laundry followed, together with the rush to remodel the building; acquire the necessary supplies, materials and equipment (much of it donated by area high schools); develop training programs; hire faculty and administrative staff; and complete the countless details needed to set up SLAVS. The board told Gundersen he had seven months.

He was up to the task. “The new president had gained the reputation during the war of going forward at full steam,” Nelson remarked in his book, “The First Thirty Years.” Sure enough, the school opened its doors on September 14, 1948, with 246 students in 14 classes, from auto mechanics to dry cleaning, fashion design to welding, with another 25 vocational subjects approved pending resources.

The first days were chaotic, with instructors competing with the noise of construction and equipment installation still underway. To save money on the hayloft conversion, contractors had built 8-foot-high partitions to create classrooms, even though the hayloft had 12-foot ceilings, which meant noise bled between classrooms and students couldn’t resist

throwing paper airplanes and wadded notes over top.

Registration was open to all over 16 years of age (including high school students, space permitting), with preference given to veterans — a primary reason for the school’s existence; the G.I. Bill paid their tuition and fees. Other students who might struggle to find the $80 per year fee ($910 in 2022 dollars) could pay in installments.

By the end of the first year, SLAVS — with 23 full-time faculty and 14 staff — had served a total of 1,387 students: 588 in day programs, the rest in evening classes. President Gundersen and his enthusiastic team had forgone overtime pay to launch the school and should have had reason to think the future was bright. Instead, they faced imminent collapse.

THE AXEMAN COMETH

In 1949, the ninth governor of the state of Utah swept into office on a platform of economic restraint. J. Bracken Lee immediately set about cutting programs he thought were fiscally imprudent; education was a prime target. “We cannot afford the luxury of another educational system,” he declared and refused to support funding for the year-old vocational school or for a similar institution in Provo.

ARISING FROM AN URGENT NEED FOR SKILLED LABOR DURING THE WAR, SLAVS WAS THE RESULT OF A NATIONWIDE INITIATIVE THAT LED TO THE ESTABLISHMENT OF ADULT VOCATIONAL SCHOOLS ACROSS AMERICA.

The legislature ignored the governor’s attempt to scrap the school, instead approving a two-year appropriations bill, with $500,000 earmarked for SLAVS. Lee vetoed it.

This precipitated a political row. The State Vocational Board of Control, the superintendent of public instruction, veterans and labor organizations were quick to weigh in, arguing that the community’s need for trained workers could not be met without the school, and that the veto discriminated against veterans. Lee would not back down, although he did invite Gundersen to submit a trimmed-down budget, which he did. Again, the governor said no, refusing to grant a deficiency appropriation. While Lee did not have the power to close SLAVS outright, he could effectively starve it to death.

But the fight was not over. The Board of Control pushed back again, finding discretionary

money to fund Gundersen’s new bare-bones budget. The school would be able to limp along for another two years, albeit with extreme belt tightening and some layoffs. Beyond that — with a hostile governor and no appropriation from the state government — there were no guarantees.

Amid this turmoil, Gundersen, with permission from the board, left for Germany for six months to advise the U.S. Army on vocational education. On his return in midSeptember 1949, he had a lucrative job offer in his pocket from Kennecott Copper as director of the mining company’s training operations. As Nelson tactfully put it, “This excellent opportunity, coupled with the uncertainty of the continued operation of the school, influenced the president to accept the position.” While Gundersen did offer to continue working part time at the school, the board wanted a leader who could devote all his energies to the crisis at hand. Gundersen stepped down, and in October 1949, the board named Nelson as acting president, giving him the full title at the end of December — and the task to guide the school through the financial storm.

So began the first of what Nelson aptly termed the “starvation years,” a two-year period during which the school had to find ways to exist without financial support from the state.

Opposition to SLAVS would last until 1957, when Gov. Lee’s second term came to an end.

A LIFETIME OF SUPPORT

Jerry Taylor has fond memories of the classrooms in the old Troy Laundry, the original downtown campus of Trade Tech, as the school became known in 1959. “It was all hardwood chairs and desks and really high ceilings,” he says. “We’re talking old-school. Nothing like the modern labs and classrooms they’ve got now.”

QUALITY SUPPORT

MY OWN BOSS

After a stint in the U.S. military, Taylor signed up for night classes at Trade Tech in 1962. During the day he worked as an apprentice field electrician; two nights a week for the next four years he made the short trip to the school for apprentice training. “I was in a class with 20 to 25 other students. We were all in our early 20s, mostly seasoned people looking to raise our skill levels,” he says. “Great bunch of guys. The instructors were the best too.”

When asked for a story about his student life, Taylor laughs. “About the only thing remember from that time is we’d do three hours of lab work and then head out for a beer at a bar with go-go dancers to blow off steam.”

He passed his course at Trade Tech in 1966 and started working as a journeyman electrician for a Salt Lake City electrical contractor. By 1970, he had risen to electrical superintendent and found himself running jobs for the firm at Snowbird, one of Utah’s premier ski resorts in the Rocky Mountains. “I was up there for three or four years wiring concrete condominiums,” he says. “Then the company I was working for went bust, and I decided to go out on my own.”

In those early days at what would later become Taylor Electric — electrical contractors specializing in commercial and industrial buildings — it was just himself, a couple of apprentices and his mom, who did the books. One day Taylor’s mother showed him an article in the newspaper about a student named Grant Marchant from his alma mater. “That’s the kind of young guy you need to hire,” she said. Marchant had won the state contest in electrical construction wiring for the Vocational Industrial Clubs of America (VICA, known as SkillsUSA today) and gone on to represent the college at the national contest, coming in second. “His instructor later told me he would’ve come first if he’d worn hard-toe shoes instead of sneakers,” remarks Taylor.

He persuaded Marchant, who was then attending the University of Utah, to work for him on Saturdays. After several weeks, bad weather caused Taylor to suspend work for the day on the project Marchant was working on. Rather than send him home, Taylor brought the young fellow into his shop. “He was a bright kid, so gave him a set of blueprints and showed him how to count light fixtures, outlets and all the other stuff, figuring that would keep him busy for the rest of the day. Two hours later, he’d got it all done. Whoa!” Marchant caught on so fast that after a few weeks, Taylor made him an estimator for his growing company. “He’s probably as good as or better than anyone in the business,” Taylor adds.

LEGACY

That was the start of a long relationship between Taylor Electric and the college. Taylor stayed in touch with the instructors, who frequently sent him apprentices. “For four or five years they even had me judge the VICA contest. And we continue to employ graduates coming out of SLCC,” he says, adding that these days he’s retired, having handed over the reins to his son. Today, Taylor Electric boasts more than 250 employees and a firm place in the top ranks of Salt Lake City electrical contractors. In retirement, Taylor has kept his strong ties to SLCC. In 2000, he funded the first of several scholarships at the college, now administered as the Jerry Taylor Endowed Scholarship under the Foundation Board scholarship program. “I love helping students get ahead who might otherwise not manage because of money,” he says. “And these kids — get letters from them that just bring tears to my eyes. ‘I wouldn’t have had another year if had not received your scholarship. I was broke.’ ‘I couldn’t work enough hours to get money and still go to school’ … mean, story after story. It just motivates me to do more.”

For its part, SLCC in 1989 recognized Taylor’s success in building his business with a Distinguished Alumni Award. And in 2020, Jerry and his wife, Edna — who had a career in children’s television as Miss Julie on “Romper Room,” which ran on KSL-TV in the 1970s — were jointly honored by the college with an honorary doctorate of humane letters. ●

STRUGGLE FOR SURVIVAL

Nelson wasted no time in mounting a campaign of ruthless economy in a bid for survival. He reviewed the viability of every program, charging instructors to recruit students or face closure. He scrutinized every expenditure, raised tuition and tapped into every possible source of income. The school curtailed evening classes and ran no summer session in 1950. During this difficult period, he noted, “All members of the staff and faculty exhibited a spirit of determination to operate the school in an exemplary fashion.”

No one received a pay raise.

The austerity measures seemed to pay off.

SLAVS even recorded a small surplus at the end of the 1949–50 school year. But the following year the crisis intensified. Projections clearly showed the school would run a deficit. Without money from the legislature, it would have to close by March 1951.

Nelson embarked on an intensive publicity campaign to garner support and to lobby the governor and legislators to approve deficit funding. The community rallied: the chamber of commerce, the various education boards, the University of Utah, union groups, and military and business leaders all added their voices, stressing the urgent need for vocational training at a time when the country was embroiled in the Korean War. Also on the table was an option to buy the school’s building, which was coming due. At $312,000, the purchase price was a

bargain, supporters argued, since three years’ rent had already cost $110,000.

Gov. Lee was unimpressed, resisting funding requests for the school and deferring the decision to buy the building. He ran into opposition from the appropriations committee of the legislature, which recommended $275,000 for SLAVS in the coming budget, plus money for the vocational school in Provo. “Lee Loses 1st Round to Schools,” crowed a headline in the Deseret News on February 8, 1951.

The battle continued, with proposals, vetoes and counterproposals. When the dust settled, the school prevailed. Not only had the Utah legislature appropriated $37,550 to see SLAVS through the 1950–51 school year, it had also funded the school for the next two years — plus there was money allocated to buy the old Troy building.

The only fly in the ointment was the amount of the two-year appropriation. “They have shown that the vocational school can function properly without requiring the huge appropriation that was originally requested,” stated the governor in an address to the legislature, which duly cut funding to the bone. As Nelson lamented in his book, the school’s success at running on a shoestring budget meant it would now have to manage with less than it had for either of the two previous starvation years. But manage it would.

THE RISE OF GENERAL EDUCATION

In the early days, students attended classes for six or eight hours, spent mostly in practical lab work: welding plates, rebuilding motors, dressing wounds — whatever their particular field required them to learn. They also received one classroom hour on theory delivered by their instructor. But something was missing. Surveys of both students and employers in the community revealed a need for instruction in math, science, English, communications and other subjects useful to graduates once they were in the world of work. Related training, it was called back then. The problem was, who would teach these courses?

FEATURED FACULTY

KAREN KWAN

PROFESSOR, PSYCHOLOGY

With bachelor’s and master’s degrees in clinical psychology from Pepperdine University and a doctorate in educational leadership and policy from the University of Utah, Karen Kwan serves both as a professor of psychology at SLCC and as a Utah State representative — the first Asian American in the Utah legislature. In 2014, SLCC recognized her outstanding work for the college by choosing her as its Distinguished Faculty Lecturer, an annual SLCC honor that culminates in a public presentation. Kwan delivered an impassioned address on the bullying of Asian and Pacific American teens in Salt Lake, as well as student perspectives on how such oppressive behavior could be reduced. ●

SPLITTING AT THE SEAMS

By the mid-1950s the school had all but outgrown the converted Troy Laundry buildings, which were already in serious need of renovation when a boiler exploded in 1955. During the inspection of the damage, a building and grounds committee member named Elmer Christensen commented that it was too bad the whole building hadn’t blown up: “It might have facilitated the acquisition of more adequate, modern facilities.” The governing board decided the $300,000 tab to bring the antiquated buildings up to par “would be throwing money

down the drain.” It authorized stopgap repairs, but the hunt was on for another campus site.

The postwar period in America was marked by a rapidly growing dependence on the automobile. It was also a time when many white middle- and working-class families abandoned inner cities, a trend historically known as “white flight.” Owning a car made it easier to move to the sprawling suburbs that were multiplying in many parts of the country, including the Salt Lake City area. More cars meant more skilled workers were needed to repair, service and paint them. SLAVS responded by ramping up its auto mechanics and auto body repair and painting courses. It was similar in other trades. Through advisory committees and other contacts with business and industry, the school kept tabs on the changing needs of the community, modifying and developing programs to meet them.

By 1959, the school had doubled in size to more than 2,000 students, with a waiting list as large as its enrollment. The school emphasized its need for more space, along with Utah’s growing skills requirements, in a brochure titled “We’re Splitting at the Seams,” which it delivered to the legislature.

With the strong support of the board, legislators responded by passing a bill allocating $200,000 for the purchase of an

initial 72 acres at 4600 S Redwood Road for future expansion. The land, with frontage on Redwood Road and 2200 West, was close to the population center of the valley, which was rapidly moving south. Over the next 12 years, further appropriations increased the size of the campus to 103 acres. The college would have to wait until 1967 before it could move to the new Redwood Campus.

The 1959 bill also changed the governance of the school. Since its inception, SLAVS’s governing authority had been the State Board of Vocational Training, which had originally put in place a board of control — consisting of representatives from all the high schools in the Salt Lake Valley — to oversee operations. At the time this made sense, because the school was seen as a center for high school vocational education. Eleven years later, it was clearly more of an adult educational institution, and legislators decided to uncouple the connection to high schools and give the board direct governance. To mark the change, they gave the school a more adult-sounding name: Salt Lake Trade Technical Institute — or Trade Tech, as it was affectionately known. As a former SLCC history professor, Ernest Randa, joked in his book, “Salt Lake Community College: A College on the Move,” it was no longer “a high school with ashtrays.”

What do a shot duck and a rubber dollar have in common? They were both early attempts to promote the school — and incidentally throw light on how times have changed.

GAG REEL

President Nelson and his team put great stock in getting the message out about the programs they offered and the important role the school played in the life of the community. Until 1970, when Nelson hired Bryan Gardner as the first full-time public relations director, various administrative staff members stepped forward to tackle these promotional activities. They used every tool they could find, from course catalogs, posters and brochures to open houses, slideshows and even movies. Nelson rarely missed an opportunity to deliver a speech at vocational conferences, dedication ceremonies, civic clubs and, of course, the legislature, where he was frequently found lobbying for financial support.

The slogan “Learn to Earn” graced many a promotional piece into the 1970s. With its message of financial rewards for those with vocational skills, it was aimed mostly at prospective students. It was also the title of the school’s film debut, with a “massive” $1,200 budget authorized by the State Board for Vocational Education.

The 16 mm, color-and-sound motion picture “Learn to Earn” hit screens in 1952 to much fanfare. To today’s viewers, it looks hammy and dated, but it did a good job of showing high school students the college’s range of trades and professions.

The school staged a gala premier showing of the halfhour movie, complete with giant spotlights crisscrossing the sky over the theater. Staff and faculty put on stunts and skits for the delight of the crowd. Bernice Patterson, a tailoring and fashion design instructor, featured in one skit as a big-game hunter. Kitted out in safari gear, she was to fire a blank-loaded shotgun into the air and a duck was to fall onto the stage, cleaned, plucked and ready to cook. Things did not go entirely to plan. The gun went off and the duck did fall, but it landed on a pregnant woman in the front row. She was not seriously hurt, but as Nelson (groaningly) quipped, “The event started an untruthful rumor that she subsequently had triplets, which were Huey, Dewey and Louie.”

FUNNY MONEY

Whether the rubber s-t-r-e-t-c-h dollar was Nelson’s idea or one of his staff’s, it was a great success as a promotional gimmick. A thin rectangle of rubber, it looked like a regular dollar bill, except for, as Nelson explained, “spoof drawings and words calculated to raise a laugh” on one side and a sales pitch for the college on the other. The idea was that attending the school would stretch your dollars — a riff on “Learn to Earn.”

The college gave away thousands of the stretch dollars — until the U.S. Treasury came calling. “Anything that could be mistaken for U.S. currency is illegal,” intoned the officious agent. Not willing to risk a fine or a federal hassle, the college public relations director pulled the successful promo. ●

FROM LEFT: AT THE GRAND PREMIER OF THE SCHOOL’S 1952 PROMOTIONAL FILM, “LEARN TO EARN,” INSTRUCTOR TURNED HUNTER-FOR-A-DAY BERNICE PATTERSON TAKES AIM AS PART OF A SKIT; THE SAME SLOGAN, CALLING FOR FINANCIAL GAIN THROUGH VOCATIONAL TRAINING, GRACED MANY A PR INITIATIVE WELL INTO THE ‘70S.

THE CLASSROOM SPACE RACE

When the Soviet Union put a satellite in orbit in 1957, it galvanized American political leaders into action. There was widespread concern that the USSR had moved ahead in the technological race between the superpowers. The country’s Cold War adversary had got one over on America. The following year, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into law the National Defense Education Act. Its goal was to boost America’s educational system to help the country compete with the USSR in science and technology. The act provided loans and grants to students in colleges and universities, including a provision called the Vocational Improvement program that targeted people with skills who happened to be on welfare. Of more significance to Trade Tech was the Manpower Development and Training Act (MDTA) of 1962, which provided both training for unemployed people without skills and retraining for thousands of workers jobless because of automation and technological change.

The school taught 15 short-term courses with MDTA funds. Some, such as waitressing and stenography, lasted three months; others, like auto mechanics and auto repair, ran for a year. The school expanded its faculty considerably to manage the new course load. The MDTA program brought in a flood of new students, and by 1965 the school was truly splitting at the seams. It was forced to rent three annexes in the city to accommodate the influx. One of the buildings, rented to conduct auto body repair and painting classes, was reputed to be a former brothel. Nelson reported that students taking the course came in for some ribbing. “Exactly what profession are you training for in that location?” they were asked. By the end of the MDTA program in 1969, enrollment had more than doubled again to 5,400. Fortunately, by then the school had moved many of its programs to the new Redwood Campus.

COLLEGE CHAMPIONS THE

DUMKE FOUNDATION

In 1988, Kay and Zeke Dumke established the Katherine W. Dumke and Ezekiel R. Dumke Jr. Foundation “for the purpose of better and more thoughtful gift giving in the Intermountain area.” A generous donation from the foundation helped establish SLCC’s Dumke Center for STEM Learning. Opened in 2017 on the Taylorsville Redwood Campus, the 6,000-square-foot, state-of-theart resource center provides assistance to students pursuing careers in science, technology, engineering and math. The foundation also added its financial support to the building of the $43 million Westpointe Workforce Training & Education Center, which opened in 2018. ●

OPERATION BIG MOVE

The land for the Redwood Campus was purchased in 1959. At the time it was hoped that classes could be held there by 1963, but the planning process took far longer than anticipated. There was still cause for celebration that year, though: the college held a dedication ceremony at the campus-to-be, inviting community leaders, educational representatives and the entire school staff, faculty and summer student body. A highlight of the event was the ceremonial demolition of a dilapidated barn, pulled down by teams of students hauling on ropes attached to the barn’s supports.

The first building at Redwood, the heating plant, went up in 1964, followed by the administration and classroom building in early 1967, with space for 700 students. During spring break that March, President Nelson oversaw Operation Big Move: the wholesale transfer of the school’s administrative offices and eight departments to the new building.

The move coincided with another legislated change in name, to one deemed more appropriate for the growing school, now with two campuses. Trade Tech was history. When classes resumed on March 16, 1967, at Redwood, they were held at Utah

A DIFFERENT TIME

“There were very few women teaching when I started at the college,” she remembers. “I was hired as part of the Manpower Development and Training Act program to teach secretarial training to women who wanted to get back into the workforce. Then I found myself standing up in front of a classroom of men in the trades, teaching them math — guys not too much younger than me — which was quite an experience. could tell by the look on their faces that they doubted knew what I was talking about, just because was a woman.”

As Erickson tells it, women in higher education — and in Utah society in general — experienced gender discrimination regularly during this period. It drove her to strive for equal opportunities for women throughout her career. To this end, she joined the American Association for Women in Community Colleges, the Utah Consortium for Women in Higher Education, the International Women’s Forum of Utah and numerous other similar professional organizations. “It was a conscious effort, on my part, because I feel strongly, and have done from the time I was very young, that women were being overlooked,” she says. “Fortunately, things have improved, but Utah still has a reputation of being one of the worst places for women and equality in the country.”

of those national conferences is for professional women to make presentations to high school girls to encourage them to explore careers in STEM — science, technology, engineering and math,” she says. “I vividly remember flying home thinking, ‘We’ve got to get this conference in Utah!’”

Together with like-minded friends and colleagues, Erickson founded the Utah Math Science Network in 1979. For many years, it sponsored STEM events like the EYH conference. “That’s one of the things I’m proud of,” she says, adding that she’s pleased to see that SLCC has been hosting the conference in recent years with superb results. Since 2013, SLCC’s EYH conferences have drawn more than 2,500 attendees — a record 540 girls in 2016. That year, keynote speaker U of U chemist Luisa Whittaker-Brooks won the hearts of attendees with an inspiring story of her childhood struggles in Panama. And in 2018, they were wowed by Gretchen McClain, former NASA chief director of the International Space Station program, on whose watch the ISS was built (outpacing the USSR to do so).

Erickson advanced her career at SLCC from professor to associate dean to various deanships to academic vice president, a position she held from 1988 to 1997. A former Foundation Board member, she now holds emeritus status at the college.

A NUMBERS GAME

In the late 1970s, Erickson attended a conference at Mills College in Oakland, California, called Expanding Your Horizons (EYH). “The goal

Looking back over her long career, she is encouraged to see the progress her fight to improve the role of women has made. “It’s been three steps forward and one back, but we’re in a much better place than we were years ago.” ●

chapter two

GROWING PAINS

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

As early as 1959, the educational boards in Utah had discussed the pros and cons of setting up a junior college in Salt Lake Valley. Junior colleges had been around in America since the turn of the 20th century. Offering twoyear academic courses to prepare students for university, they were intended to catch those who might otherwise not have continued their education after high school. As community colleges arose to meet the needs of the communities where they were located, the two models overlapped. Community colleges, offering both academic programs and vocational job training, began to grant two-year degrees, and numerous junior colleges added vocational programs. In states like Utah, which had no history of junior colleges but had vocational schools set up during or after World War II, the push to convert them to community colleges was more of a struggle. Utah Tech seemed to many an ideal candidate to convert from technical school to community college. As Nelson remarked wistfully, “The idea was continually reintroduced and hotly debated.” Like many others in the school and the business and trade communities at the time, he strongly opposed any move to expand Utah Tech’s role beyond that of its vocational mission, fearing a loss of focus and a subsequent decline in technical education, for which demand was only increasing.

The conversion debate caught fire again in 1965, after the Utah Coordinating Council of Higher Education published a report that concluded that a junior college was indeed needed in the Salt Lake Valley, and that Utah Tech (or Salt Lake Trade Technical Institute, as it still was then) should become part of this new college. The Utah Legislative Council struck a committee to study the issue. Various sources, including several trades councils and manufacturing associations, joined Nelson in vigorous opposition, while the presidents of several Utah colleges spoke in favor. Discussions continued throughout the year with no conclusion.

Meanwhile, thanks to the postwar baby boom, enrollment soared at Utah’s schools of higher education, including Trade Tech, along with waiting lists for vocational training courses. As a result, the pressure to merge the school with a junior college faded. When legislators renamed it the Utah Technical College at Salt Lake in 1967, its status as a vocational training school seemed assured.

THE 25 PERCENT SOLUTION

The 1967 legislation proclaiming the school’s new name also spoke to its primary mission. “Vocational and technical courses … shall comprise not less than three-fourths of all courses taught at the college,” it ruled, adding that the remaining 25 percent, which it called related training, should be limited to “courses of a general nature necessary in vocational education fields and which can be transferred to academic institutions.” It also gave the college the authority to grant associate’s degrees in applied science. (Associate’s degrees in arts and science had to wait another decade.)

Courses in related training, later called general education, had begun in earnest in the 1958–59 school year. Like all educational programs, these were offered in terms of clock hours rather than credit hours. Responding to recommendations from the Northwest Accrediting Association, the college changed to a credit hour system, which meant students could now transfer credits to other institutions where permitted. Likewise, students transferring to Utah Tech could obtain credit for courses taken at other institutions.

The college also amended its schedule in the 1969–70 school year to four quarters of equal length, bringing it more in line with other twoyear institutions in the state.

While based on the need for accreditation, these changes were also prompted by the growth of general education at the college. By 1968 students could take technical writing, vocational civics, blueprint reading, human relations and many other related instruction classes, as well as basic classes in math, communications, English, science and safety. The basic programs were offered at several levels, some of which were transferable to four-year institutions.

“While Jay Nelson always worried about the impacts on vocational programs caused by the

growth of general education, he had the vision to realize that the college had to answer the needs of those in the community who were looking for a more affordable education,” says Judd Morgan, past interim president, who joined the school in 1976. Morgan adds that in the beginning, it was a battle to persuade four-year colleges to accept their credits. “They viewed us as the second cousin that didn’t know how to teach appropriately. We had to work to win credibility, which we soon did. Nowadays we transfer credits back and forth with no problem.”

As the 1970s progressed, the demand for general education further increased, and the college added courses such as chemistry, sociology and economics. Some students were even taking general education courses exclusively. This growth bumped up against the 25 percent limit on academic education.

As Ernest Randa noted in his college history book, Utah Tech “became adept at creative statistics and class nomenclature to cover the uncomfortable fact that students were primarily interested in transfer classes.”

This did not go unnoticed. In 1974, Utah Tech and its sister technical college at Provo received a rap on the knuckles from Utah’s Advisory Council for Vocational Education for flouting the 75/25 rule. As Nelson pointed out, “The council was of the opinion that funds were being expended unnecessarily on general education and should be used to start new trade

and technical programs.” This precipitated a two-year debate among faculty, education boards, legislators, students and community representatives. In the end, the state board pressed the college to make changes to bring it into compliance with the law.

But the issue was not going away. At heart was the same old debate: should the institution stay primarily technical–vocational or should it transition to a community college? In Nelson’s words, “It will be raised continually by the various constituencies of the community and will undoubtedly be discussed and debated in the years ahead.”

The requirement to maintain vocational education at 75 percent remained in law until 1987, when the college became Salt Lake Community College, although as Randa notes, “its provisions were quietly evaded by teaching mostly college-prep courses under vocationalsounding names.”

A note on college governance: In 1978, the state legislature vested control of the school in the Utah State Board of Regents. Prior to that time, there was a confusing system of dual governance by the State Board for Vocational Education (for day-to-day management) and the State Board of Higher Education (finances, curriculum and capital facilities). Over time, the former board became the Institutional Council, which in 1992 was renamed the Salt Lake Community College Board of Trustees.

DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI AWARD

Since 1963, the college has presented the Distinguished Alumni Award to graduates who have risen to a high level of achievement in their career and in the community. It is the highest alumni award recognized by the college.

GRADUATES OF EXCELLENCE AWARD

Chosen from each of the college’s schools, recipients have demonstrated high academic achievement, leadership skills and a dedication to serving others.

RISING STAR ALUMNI AWARD

New in 2022, the Rising Star Alumni Award recognizes SLCC alumni who show noteworthy achievement and strong community service early in their careers. ●

From the time he took up the reins as the second president in 1949 to his retirement in 1978, Jay Nelson ran the school with military precision.

Nelson made every significant administrative decision, reviewed all major expenditures, made all final hiring decisions and kept close tabs on the quality of instruction and the physical state of the school. Out in the community, he became so closely identified with the college that the two were almost synonymous.

Nelson’s top-down approach meant the school was highly dependent on his leadership. When he stepped down, he left an administration with few established procedures or clear lines of authority, other than those up to the president — a deficit that needed swift remedy.

LAUGHING WITH YOU

TOP BRASS

Nelson’s success in keeping the school alive in the early starvation years through a combination of internal micromanagement, intensive political lobbying and the courting of favorable publicity set a pattern that repeated across his presidency. His top-down administrative style, in particular, led many under him to compare Nelson to a military leader. “He ran a real tight ship,” said Neal Grover, a faculty member since 1964. “On Saturday, he came around with his entourage and checked everything out. It was a lot like the military.”

On his watch, bells were rung for assemblies and classes, keys to shops were returned after class, roll calls were taken and there was a strict dress code for faculty. These procedures continued when the school moved to the Redwood Campus — until one instructor, Parker Pratt, pointed out their impracticality at the more spread-out campus. “Pratt was nominated for the Nobel Prize,” joked Tom Ellison, graphic arts professor.

Nelson enjoyed a joke and often had several prepared for faculty meetings. When he retired, the college gave the grand old patriarch a fine send-off at a gala banquet at the Salt Lake Hilton before 550 attendees. The event coincided with the third recognition awards ceremony, a program set up by Nelson to honor faculty and staff with long-service awards. Always a bit of a showman, on such occasions Nelson would conclude his introductory remarks by lighting an “eternal candle” to symbolize Utah Tech’s continuing public support and acclaim. On this night as he lit the candle, he was surprised by PR Director Ron Ollis, who rushed on stage and presented him with a Liberace candelabra, much to the delight of the audience. More surprises followed, including congratulatory letters from President Jimmy Carter and comedian and actor George Burns — the latter considered an even higher power thanks to his title role in the previous year’s hit film “Oh, God!”

Nelson never lost his sense of humor. He was well into his 90s when he was awarded an honorary doctorate from SLCC. On that special day in 1988, he began his acceptance speech by noting, “Old college presidents do not die, they just lose their faculties.” ●

NELSON’S COLLEGE

NELSON’S COLLEGE

BRIDGES TO BE BUILT

The influx of new faculty to teach general education courses fundamentally changed the college. They brought with them attitudes, academic experience and educational credentials that differed significantly from those of their vocational and technical colleagues. One outcome was a self-perpetuating growth in general education: ideas for new academic classes sprang from the interests and backgrounds of the new faculty and were often popular with students. Another effect saw an increase in the assertiveness of the faculty.

Teachers coming from colleges and universities in which faculty had a say in hiring, tenure and departmental budgets lobbied for similar powers at Utah Tech.

Almost inevitably there were ructions between vocational and academic faculty.

Across the country, wherever junior and technical colleges transitioned to community colleges, these institutional growing pains were commonplace. At Utah Tech, some vocational faculty feared losing funding and status to academic programs. “All of a sudden, we began hiring people who were taking the money and using it in programs that weren’t vocational ed: English, biology, chemistry — programs that would transfer to other colleges,” recalls Morgan. Others resented the pay grid that rewarded those with formal degrees. “It took some missionary work, if you will, to smooth the feathers of the vocational faculty.”

There was another effect. As the academic faculty grew, so too did internal support to become a community college. That was not going to happen with Nelson as president. But the seed was sown.

A RISING TIDE

Funding for MDTA programs, which were developed to offer vocational skills training to the unemployed and disadvantaged, ceased in 1969. The Utah Manpower Council took up the slack by establishing programs in several locations the next year, including Utah Tech. These were combined six months later into the Skills Center, which the Utah Board for Vocational Education decided should be located at Utah Tech. But first the college needed to agree. It formed a committee of administrators and faculty to discuss the issue.

The Skills Center was voted into the college, and in 1972 it was given a permanent home on the old downtown campus. Starting with 210 students, by 1978 it boasted more than 2,000. It continued its mission of offering open entry/open exit courses designed to provide basic vocational skills to students who might otherwise not attend college up into the 2000s, when its programs were merged into the School of Applied Technology.

When the Salt Lake Area Vocational School was established in 1948, the Salt Lake Valley was clearly divided east from west along racial and socioeconomic lines. On the east side were white, formally educated middle- and upper-class families; the west was ethnically more diverse, working class and less formally educated.

High schools in the east offered little vocational training but full college-prep courses. For west-side schools the reverse was true: a wide variety of vocational training and few academic courses.

Until the civil rights movement, this east–west divide was reinforced by racially restrictive housing covenants, common in many American cities at the time. Some east-side neighborhoods prohibited house sales to non-Caucasians.

Politically, Salt Lake City’s government system of at-large commissioners effectively meant the wealthier, more educated east side dominated. For decades, there were no west-side commissioners: few residents could afford the expense of a political campaign. As a result, the east got the funds for new school buildings and

well-lit, well-maintained streets; the west boasted few or no new facilities and infrastructure improvements. By the mid-1980s, students were being bussed from bursting west-side schools to empty classrooms in the east. The socioeconomic division of the Salt Lake Valley began to break down in the late 1960s. The west side saw growth in more middle-class housing; its largely working-class population became more interspersed with the white middle class who were moving in. With the development of the Redwood Campus in Taylorsville, and later the Jordan Campus, SLCC played a significant role in reconciling the two sides. The importance that student equity, diversity and inclusion was to play in the college’s future has its roots in the old east–west divide. ●

A GROWING CAMPUS

The late 1960s saw extensive development of the Redwood Campus. During the 1965 session, the Utah legislature granted Utah Tech $2.5 million to construct several buildings on its new campus. Shortly after Operation Big Move in 1967, the machine shop and welding departments relocated from the downtown campus to the newly opened metal trades building. And in 1968, the college made a big public splash with the opening of the automotive building. Students from area high schools, representatives from the automotive industry and hundreds of area residents came to tour the new facilities.

More state funds flowed to the college in 1970 and 1971 to construct the technology building, a state-of-the-art facility boasting an instructional media center, a 325-seat auditorium, classrooms and laboratories for all manner of technological courses. At the building’s dedication in December 1972, the highlight of the show was a large sign with 100 flashbulbs designed to spell out “Technology Moves On.” At the critical moment, J. Campbell, the assistant superintendent, tripped the switch … and nothing happened. There was much joking afterward, with the college

attributing the fault to the switch being thrown by an academician rather than a technician. A local radio station presented the college with its Lemon Award to mark the occasion. At the graduation ceremonies the following year, the college renamed the building the Calvin L. Rampton Technology Building. The governor of Utah, who was in attendance, was delighted at the honor. There was no attempt to redeploy the flashbulb sign.

Since 1956, student leaders and alumni had dreamed of having a student union building at the school. That year, they presented Nelson with a check for $310 to be put into a trust fund for a future building and proposed a building fee be added to tuition fees. Over the years, the fund grew, and in 1964, the president formed a committee to make the dream a reality. It took another decade and a top-up from the sale of revenue bonds before the College Center opened its doors to the student body on the Redwood Campus. It was renamed the Student Center in 1987. The Construction Trades Building came along in 1977, and before Nelson’s long term in office came to a close, the development of the $5 million Business Building on Redwood Road was well underway.

COLLEGE CHAMPIONS

JESSELIE AND SCOTT ANDERSON

Deeply engaged in community affairs, Jesselie and Scott Anderson have lent their support to a range of SLCC initiatives over the years. These span programming, scholarships, cultural enrichment activities and campus facilities. By virtue of her long-standing service on the SLCC Board of Trustees and the Utah Board of Higher Education, Jesselie has been a true champion for the college and its students. She was instrumental in the initial planning of the college’s Washington, DC, internship program and the new Herriman Campus. Her husband, Scott, president and CEO of Zions Bank, has perennially supported the Gail Miller Utah Leadership Cup, a golf tournament that doubles as the primary fundraising event for student scholarships. Together, the Andersons also founded the Bridge Builder Scholarship program. ●

THE INITIAL 72 ACRES OF THE REDWOOD CAMPUS WERE PURCHASED AFTER APPROPRIATING $200,000 ON JANUARY 1, 1959. TODAY THE TAYLORSVILLE REDWOOD CAMPUS HOUSES MANY FACILITIES, AS WELL AS THE ECCLES CHILD DEVELOPMENT LAB SCHOOL, THE STUDENT CENTER, THE DUMKE STEM CENTER, THE MARKOSIAN LIBRARY AND MUCH MORE.

Car problems on campus? Take it to Utah Tech’s automotive repair folks. They’d love to get your motor running. Great learning experience too!

HANDS-ON EXPERIENCE

Brett Baird, longtime automotive technology instructor, remembers when he enrolled at Utah Tech in 1973 to learn about fixing cars. “The instructors in the automotive program were awesome. Each had industry experience in one area of expertise and taught a class just in that area, instead of trying to cover every automobile system. As a result, they were all on the cutting edge of their specialty.” Class sizes were capped at 18 students, allowing them ample one-on-one time with the instructor. They spent about 20 percent of their time on classroom studies and 80 percent in labs. “And it was real live experience,” says Baird. “Students, faculty or staff who had a vehicle needing an automotive repair that fit the curriculum could bring it into the labs and we’d diagnose and repair it. You couldn’t get better lab experience than that.”

The group trooped down to the classroom where Southwick was lecturing and lined up outside the open door. They needed his signature to register. The instructor ignored them for a good 10 minutes. Eventually, Southwick looked over at Baird and the other hopeful students. “What can I do for you guys?” he asked in his authoritative voice.

Baird stepped into the classroom. “Well, we want to know where the line starts to challenge your course,” he said with a cheeky grin.

Southwick reddened. “So you want to challenge my course, do ya?” he boomed menacingly. “I’ll give you a test you’ll never forget.”

“No, no, no. We’re just kidding, just kidding,” Baird said quickly, to general chuckling from the class.

HOLY MOSES!

During his two years as a student, Baird recalls how he and his classmates formed tight bonds and how they jockeyed to sign up for the best instructors. “A bunch of us were determined to take engine repair next quarter from Ray Southwick, who had a fabulous reputation.” At the time, you could challenge a course, which meant if you already knew the subject you just took the final exam. “Nobody ever challenged Mr. Southwick’s courses,” says Baird. “They were so comprehensive. Besides, he was a bit intimidating. He looked and sounded like Charlton Heston in ‘The Ten Commandments.’”

Southwick raised his arms as if he was parting the Red Sea, and the laughter instantly died. Turning back to Baird, his fierce look broke into a grin as he acknowledged the joke. “After that, he was happy to sign our registration forms,” laughs Baird.

DREAM JOB

When he graduated from Utah Tech in 1975, Baird walked straight into a career with a local automotive company, as did most of his classmates. For 14 years he rose through the company, ending up in corporate training before seizing an opportunity to teach at SLCC in the automotive program, which he did until his retirement at the end of 2020. “It was kind of a tough decision to retire,” he says. “I’m a very fortunate person because was able to get up and go to work at my dream job every day for 31 and a half years.” ●

THE STUDENT BODY SHOPTHE END OF AN ERA

After 30 years at the college, 28 as president, Jay L. Nelson submitted his resignation on February 16, 1978. Reading between the lines in his book, “The First Thirty Years,” it’s clear he was reluctant to go, having to bow to the retirement policy of the State Board for Vocational Education.

His legacy is clear: without his dogged determination to fight for funding to deliver vocational training to the community in those early years, the school would not have survived — and this book would never have been written.

Judd Morgan remembers a leader who had a great love of the college. “He was a straight shooter who gave it his all. The college, in my mind, is the college because of Jay Nelson.”

Over the years, Nelson presided over a vibrant and growing college. From converted horse barns and make-do equipment, the college soon boasted technical facilities comparable to industry. Its trade-prep programs expanded from 16 in 1948 to 43 in 1978, not including the numerous Skills Center programs. Then there was the development of numerous general education courses, many transferable to other institutions. Over the same period, headcount figures kept by Nelson recorded an almost tenfold growth in the student population, surpassing 11,000 in his final year.

Under his tight personal control, the school delivered on its mission. “During most years, well over 90 percent of its graduates found jobs in the area of their training,” Randa noted. He added that Nelson left the college as an established part of Utah’s education system. “No legislature, governor or interest group could contemplate defunding the school or dispersing its functions to other places.”

During his tenure, Nelson defiantly held back the forces propelling the school toward a future as a community college. From his perspective, he had the best interests of the college — and the community — at heart. In his letter of resignation, he pleaded one last time that those who follow him resist the community college temptation. “It is my personal philosophy that Utah Technical College at Salt Lake should be perpetuated as a two-year technical college. In spite of our good intentions and strong desires, we are not meeting the need for trained craftsmen in the state of Utah. Until we are able to meet the objectives for which the school was established, it is my view that all academic concepts of the traditional community college should not be incorporated.”

It would take almost a full decade and three more administrations before his vision was reversed.

BOB ASKERLUND

ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT EMERITUS, FACILITIES SERVICESDuring his 32 years at Salt Lake Community College, Bob Askerlund was steadfast in his dedication to the campuses, facilities and buildings across the valley — all spaces that transform lives integral to the college community. And he applied himself with a winning demeanor that reflected his firm belief in SLCC’s larger mission. ●

“HE WAS A STRAIGHT SHOOTER WHO GAVE IT HIS ALL.

THE COLLEGE, IN MY MIND, IS THE COLLEGE BECAUSE OF JAY NELSON.”

PRESIDENT

“THE FUTURE IS NOT SOMEPLACE WE ARE GOING TO, BUT ONE WE ARE CREATING. THE PATHS TO IT ARE NOT FOUND, BUT MADE; AND THE ACTIVITY OF MAKING THEM CHANGES BOTH THE MAKER AND THE DESTINATION.”

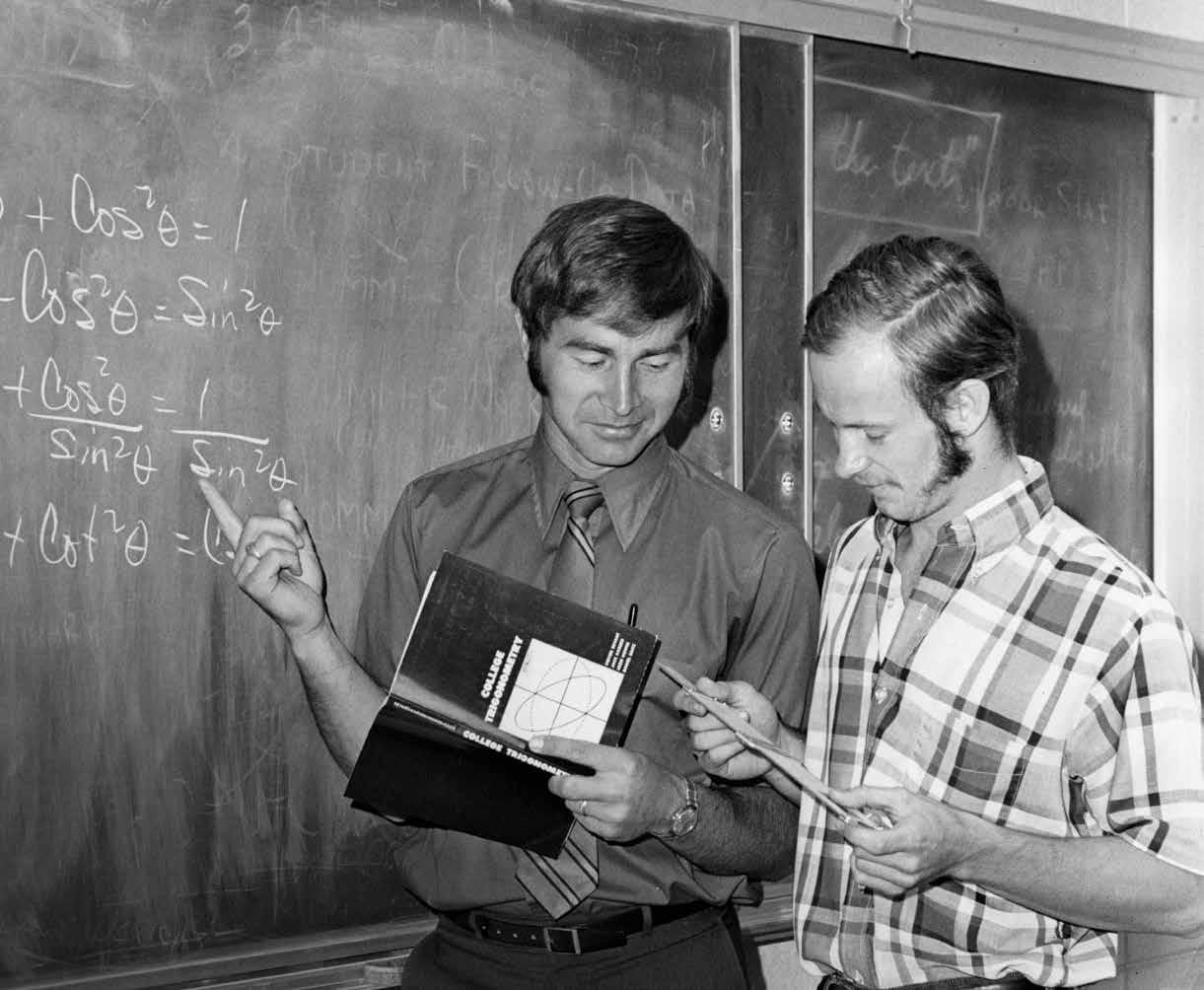

WITH THE ARRIVAL OF DALE COWGILL IN 1978, THE COLLEGE SOUGHT TO ENHANCE ITS TEACHING EXCELLENCE IN BOTH THE VOCATIONS AND IN GENERAL EDUCATION, WHICH HAD FIRST ARISEN AS “RELATED TRAINING” WAY BACK IN 1958. GENERAL EDUCATION INCLUDED TRIGONOMETRY AND ALGEBRA, AS SHOWN HERE (NOTE THE STUDENT’S SLIDE RULE).

chapter three YOU SAY YOU WANT AN EVOLUTION?

A NEW DIRECTION

Dale S. Cowgill assumed the office of president of Utah Tech on October 16, 1978. Formerly the dean of technology at Weber State College, Cowgill represented a marked change from his predecessor. Not only did he bring a looser management style, he also championed the transformation to a community college — qualities the search committee considered essential.

One of Cowgill’s first and most controversial innovations was to reorganize the college’s administrative structure. Students were given the highest priority; faculty and staff who worked directly with students next; administrators and indirect staff were given third priority. The office of the president was to support all levels. “Some people found it hard to understand this flat organizational structure,” says Judd Morgan. “But it worked for me. I could maneuver through it and have success.”

On the educational front, Cowgill promoted several forward-thinking ideas, including educational research to improve teaching. Teachers who were keeping up with their field and incorporating new ideas into their curriculum were essentially conducting research, and that should be recorded. He believed the college had a duty to preserve and transmit knowledge, and to develop new knowledge. He introduced the concept of “master teachers,” who, in his words, were “those who master both their subject matter and the art and science of teaching.” They would be paid more and expected to teach not only students but also other teachers. In his view, there were already some on faculty who were capable of taking on this role. There were definitely some who were skeptical of these ideas. As Randa wrote, “President Cowgill himself was clear on what he meant by master teachers, but the idea was not communicated adequately to all faculty, and some faculty may have used incomprehension to avoid an uncomfortable subject.”

His ideas on master teachers and educational research may have been unpopular at the time, but like many of his innovations, they were taken up later. In the 1990s, under President Frank Budd, the college embraced the idea of master teachers and set up the Faculty Teaching & Learning Center to promote educational research and help faculty become better teachers.

Cowgill never saw the fruits of his labors. These programs hardly got started before he was forced to resign. Suffice to say, it was clear that the new broom was encountering resistance in the corners.

THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY

Perhaps Cowgill’s best remembered innovation was his foray into strategic planning, a first for the school. Made up of 34 members from all areas of the college, the Committee on Development had three functions: “To define the college’s place in the world, to find better ways to administer the college, and to introduce new teaching innovations and improvements.”

The committee quickly became known as Codfish, a nickname encouraged by the president to remind team members to use their power wisely lest they become too self-important.

“Codfish are very ugly creatures who yield that hated dosage called codfish oil,” he remarked.

“Indeed, some of what we were going to do would be seen as fishy to some because they had never heard of such things before.”

Cowgill liked to quote futurist John Schaar to the committee so they would better understand the philosophy behind their activities. “The future is not someplace we are going to, but one we are creating,” he’d say. His vision was that the college could define its own future by understanding global trends and adapting accordingly. Codfish, with its collaborative chorus of the best minds in the college, was the vehicle to realize this vision. But it was not to be. While the committee indeed worked to fulfill its mandate, Cowgill’s time at the college was cut short and the committee’s ambitious plans shelved.

Codfish did produce a final report that detailed its predictions of worldwide trends and how the role of the college should change in response. Three stand out as prescient:

• The college will become a more integral part of the community.

• As population density increases in this area, the size and location of settlements will lead to less centralized college facilities on multiple campuses, with more emphasis on the needs of the individual areas they serve.

• Minorities will play an important part in the development of the college. Attitude changes toward minorities should be developed throughout the college.

COWGILL

KNOWLEDGE,

PRESIDENT

BELIEVED THE COLLEGE HAD A DUTY TO PRESERVE AND TRANSMIT

AND TO DEVELOP NEW KNOWLEDGE.DALE S. COWGILL SERVED AS PRESIDENT FOR ONLY TWO YEARS (1978–1980), BUT HIS EARLY AND FAR-SIGHTED THINKING ON THE ROLE OF THE COLLEGE HAD ENDURING EFFECTS.

STUDENT LIFE THROUGH THE YEARS

like for earlier generations.

Student leaders in smart blazers, ties, slacks and dresses? Student clubs set up and run by faculty advisors with little input from members? Until the 1970s, that was the norm.

A DIFFERENT ERA

In the early years, students had less time and inclination to get involved outside the classroom. As students at a vocational school, they were there to “learn to earn”; the focus was on the outside world of work they were training for. Unlike in more academic settings, there was little interest in debating ideas and promoting causes. The school was a commuter college: with social lives and families waiting at home, students had less incentive to get involved with on-campus events. There were no intercollegiate sports until the late 1980s. While SLCC today is still primarily a commuter college, its curriculum has become more academic, it boasts a number of men’s and women’s sports teams and its student population has become more interested in campus social life.

Students involved in the college today, whether through clubs, student government, sports or just the daily experience of life on SLCC’s many campuses, may well boggle at what it wasGOVERNMENT BY THE PEOPLE

Ever since the first classes in 1948, there has been student government at the school. Elected through classroom ballots in the early years, student-body officers organized extracurricular activities such as parties, dances, assemblies, athletics, awards and publications under the watchful eye of faculty advisors, very much as in high school.

By the time the school moved to the Redwood Campus and became Utah Technical College in 1967, student government had matured into something more recognizable today, with more status and with studentspecific issues of more concern. Officers also had their own student government offices for the first time in the Nelson Administration Building. Today, the SLCC Student Association serves and advocates for students through a number of offices located at student centers on the Taylorsville Redwood, South City and Jordan campuses.

WELCOME TO THE CLUB

As he did with everything else during his presidency, Jay Nelson kept tight control over student clubs, often personally assigning staff or faculty advisors to oversee them. Advisor meetings to discuss club activities were held with no members present, and often the push to form a club came from above rather than from the students themselves.

Nelson encouraged the development of student clubs, often promoting them at orientations at the beginning of the school year. At one such event, he spied the president of the Rodeo Club in the audience and called him up on stage. “What President Nelson didn’t know was that Shorty had been in an accident a few days before school started,” related Earl Bartholomew, chairman of the business department.

“So Shorty got up, he had a bandage around his head, one arm in a sling, a brace around his neck, another on one leg and was using crutches.” As he hobbled up to the stage, the audience went wild. “All the faculty and students were laughing like crazy and wondering if Rodeo Club was one activity to bypass.”

This centralized control began to change in 1974 with the opening of the College Center on the Redwood Campus. Hired as its first director, Curtis Smout believed in students running their own affairs. He slowly changed how clubs were organized. By the mid-1970s, student clubs could send reps to quarterly advisors’ meetings and a few years later choose their own advisors, subject to administration approval. By the late 1990s, students could set up and run a club with the approval of the student government and the ratification of the student senate — pretty much as things are done today.

ROOMS FOR ALL

With more than 60 clubs and student organizations at SLCC, there’s one for just about everybody. As the student body has become more diverse, the interests and needs of students have changed. Along with general interest clubs such as astronomy, chess, dance and drama, students have come together to form clubs that reflect their ethnicity — such as LuchA (Latinx/as/os United for Change and Activism), the Black Student Union, the Asian Student Association and American Indian Student Leadership — or their gender, such as the Society of Women Engineers. These groups enhance the quality of student life by fostering social interactions and leadership development by promoting diversity, service and learning outside the classroom. ●

FOR THE COLLEGE,

TOO FAR TOO FAST

Dale Cowgill’s primary mission of making Utah Tech into a community college was at the root of his unpopularity. As the 1980s began, vocational faculty still strongly resisted the idea, fearing loss of status and position. In the larger community, support for him was mixed.

The time was not right. Or his methods were wrong. A no-nonsense engineer by training, he came across as abrupt and confrontational. Yet Cowgill continued to push for change. He once remarked that the school’s transition to a community college should be done all at once, because trying to do it gradually was like performing an appendectomy one inch at a time.

It didn’t help that a looming recession caused the legislature to cut the college’s appropriation by a quarter of a million dollars, and Cowgill had to tighten the financial belt. People had to be let go; programs had to be cut. Unfortunately, many wrongly linked the subsequent losses and job insecurity to Cowgill’s efforts to change the college.

Not all his initiatives were unpopular. Fourday weeks in the summer quarter met with popular support, as did dropping dress codes for faculty and creating an on-campus daycare center, set up in 1979 in response to student requests. But on balance, Cowgill’s agenda was uncomfortable for a significant number of faculty.

Although Cowgill resigned in November 1980 after a little over two years in his position, Randa noted that his vision for the college would largely be realized in the years ahead.

AN EASYGOING REPLACEMENT

Within days, the Board of Regents appointed James Schnirel, then director of planning and budgets, as acting president, while a search committee looked for a successor. Schnirel had been at the school since 1962. He knew the problems and the people involved, and he was seen as someone who could settle things down.

He had his hands full as he set about smoothing the ruffled feathers of faculty and staff so they could get back to serving the students.

To help him manage this task, Schnirel brought together a core group of administrators, including Dean of Students Judd Morgan.

“Jim Schnirel could hardly have been more different to the departing president,” remarks Morgan. “Jim was an easygoing guy who worked well with people. He was a good communicator, not forceful like Cowgill.”

Schnirel worked hard at improving communications both internally and with the larger community. He often visited departments; personally reinstated all-personnel meetings; shared bag lunches with the Classroom Teachers’ Association, the bargaining organization for faculty; invited student leaders to join various committees; and agreed with PR Director Bryan Gardner’s suggestion to start The Spotlight, an internal newsletter.

Improving the college’s public image was another initiative. At Schnirel’s direction, Gardner increased outreach to the community through more numerous news releases and by encouraging faculty to give media interviews.