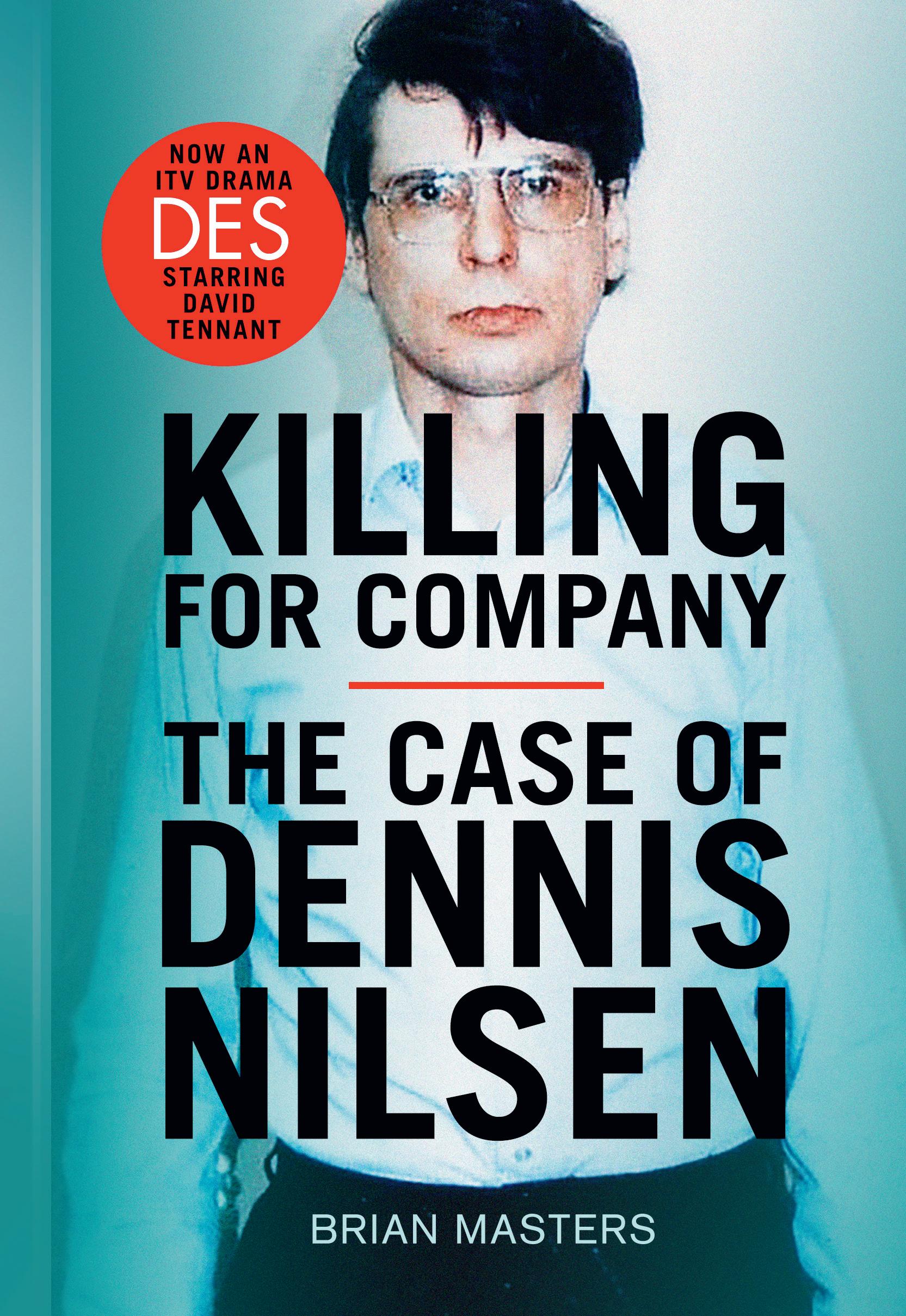

‘A comprehensive and compelling account’

Financial Times

‘Masters has written an extraordinary book, and his achievement has been the ability to recount horrific details without descending to the lurid sensationalism of the instant books and Fleet Street reports’

Police

‘Brian Masters has given us a full, well-ordered, dispassionate account of Nilsen’s life and crimes’

The Times

‘A compelling and remarkable book . . . through Masters’ fine writing the reader suspends his nausea for the crimes, and concentrates with Nilsen on his motives and himself’

The Listener

‘Quite brilliant in its assimilation of the facts . . . KILLING FOR COMPANY is a book that needed to be written, and has been executed with extreme skill and good sense’

Time Out

‘An important book which screams to be read’ New Statesman

‘The book is a perceptive and at times coldly brutal assessment of Nilsen’s psychology’

Daily Mirror

‘Brian Masters can rest assured that the job he undertook with such obvious doubts was one worth doing’

Spectator

‘Simultaneously gripping and repellent . . . I feel confident that I will not read again in 1985 a more fascinating and repulsive tale, be it fact or fiction’

Literary Review

‘Without any doubt one of the most remarkable, complete and most humanely informative accounts of a murderer’s mind ever achieved . . . the book is far superior to any previous English book of its kind and deserves to serve as a model for all future attempts in this genre’

New Society

By the same author

Molière Sartre Saint-Exupéry Rabelais

Camus – A Study

Wynard Hall and the Londonderry Family

Dreams about H.M. The Queen

The Dukes

Now Barabbas Was a Rotter: The Extraordinary Life of Marie Corelli

The Mistresses of Charles II

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire

Great Hostesses

The Swinging Sixties

The Passion of John Aspinall

Maharana – the Udaipur Dynasty

Gary

The Life of E.F. Benson

Voltaire’s Treatise on Tolerance (Edited and Translated)

The Shrine of Jeffrey Dahmer

On Murder

She Must Have Known: The Trial of Rosemary West

The Evil that Men Do Thunder in the Air

Getting Personal

Second Thoughts

PENGUIN BOOK S

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

Penguin Random House UK , One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW 11 7BW

penguin.co.uk

First published in the UK by Jonathan Cape 1985 First published in paperback by Arrow Books 1995 This edition published by Arrow Books 2020

Published in Penguin Books 2025 001

Copyright © Brian Masters, 1985

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Penguin Random House values and supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes freedom of expression and supports a vibrant culture. Thank you for purchasing an authorised edition of this book and for respecting intellectual property laws by not reproducing, scanning or distributing any part of it by any means without permission. You are supporting authors and enabling Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for everyone. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. In accordance with Article 4(3) of the DSM Directive 2019/790, Penguin Random House expressly reserves this work from the text and data mining exception.

Set in 10/12pt Plantin Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorised representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–1–78746–625–8

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

For Juan Melian and Beryl Bainbridge and also David Ralph Martin

FOREWORD TO THE 2017 EDITION

Well over thirty years have passed since the trial of Dennis Nilsen in Court One at the Old Bailey in 1983, and the publication of this book two years later. From the beginning he seemed to be a man of unfathomable depravity (I remember a woman in the front row of the jury staring at him in the dock with visible blunt incredulity, unable to attach the bureaucrat before her to the evidence she was hearing), accused on six counts of murder and two of attempted murder, with more charges that could not be brought because human remains had been reduced to ash mixed with earth, and would forever elude identification. On 4 November, the jury returned with majority verdicts of 10 to 2 on all counts of murder and one of attempted murder; their verdict on the remaining count was unanimous. Mr Justice Croom-Johnson sent Nilsen to prison for life, with a recommendation he serve no less than twenty-five years. A much later political decision by the Home Office determined that, in fact, he would never be released.

My own involvement with the case began almost immediately after Nilsen’s arrest. Like everyone else I read about it in the morning papers, and especially of the bafflement of police officers whose task it was to question him. All their initial evidence was volunteered by him over several days of close enquiry. They xiii

did not have to elicit information through cunning. He would not stop talking. They elected to take the co-operative approach, supplying him with as many cigarettes as he could inhale, and listening to the relentless narrative of admission (not ‘confession’). It was obvious that somebody would need to write an account of the crimes and trial, and I thought that perhaps I could attempt such an undertaking, since all the victims had been male, and it might require a homosexual sensitivity to unravel the sources of such derangement. I had no experience whatsoever, my previous books having been studies in French literature and an aristocratic history. But I wrote to Nilsen on remand in Brixton prison (not knowing one shouldn’t, I was protected by my own naivety), saying that I would welcome the chance to analyse the case, but would not do so without his co-operation, which was quite true – a scissors-and-paste account would be quite worthless. My first letter from him began with a disconcerting sentence: ‘Dear Mr Masters, I pass the burden of my life on to your shoulders’.

There followed eight months of contact before the trial. At least three times a week I would receive a closely-written letter on prison notepaper, demonstrating an eagerness not to waste any space, and it had presumably been passed by the censor. My replies were more leisurely and anodyne. In addition, I received from him a visiting order every few weeks, which permitted entry to the vast room where all prisoners gathered to receive friends and family for an hour. Nilsen and I sat opposite one another at a square wooden table, an ashtray between us. I noticed how other prisoners greeted him, without animosity or fear; he had helped them compose letters home. During the trial, I was taken to the cells underground at the end of each daily session. And finally, he filled more than fifty prison exercise books with reminiscence and reflection, not only on his crimes and how he had come to commit them, but on politics, literature, childhood, the army, and scorn for organised society. Knowing there would always be a danger that these might find their way outside, he planted one hideous story so preposterous that it was designed to appeal to editors of sordid newspapers. But it was not leaked.

All this exclusive access carried obvious responsibilities. The first was towards the truth which lay beyond judgement. Judge and jury would deal with the matter of guilt, whilst the writer must deal with matters of interpretation and accuracy. I started writing the book long before the trial, using material supplied by Nilsen as well as police archives, and very early on, I decided that my second responsibility would be to the readers. It was essential that I should eschew explosive adjectives (‘repellent’, ‘disgusting’, ‘horrifying’ and so on), because it was not my job to prod the reader into thinking in a certain way by using ‘trigger’ words. I had to say what happened, and the reader could supply his or her own adjectives to define it as he or she saw fit. I would be a recorder, not an assessor of moral worth or turpitude. Nilsen himself said, ‘I am an ordinary man come to extraordinary conclusion’. The story would be told, and the reader would have to decide whether Nilsen was right or not. Even he himself claimed to be mystified at times. He told me that he was hoping I would be able to reveal to him why it all happened. Indeed, part of my responsibility would be to explain as best I could.

The simmering moral danger for me was that I might unwittingly become complicit, as many suggested was inevitable. I wasn’t, of course, because I was aware of it, not blind, but I soon learnt to avoid using words that could easily be twisted against me. It was important that I did not ‘understand’ the murderer, which might sound sympathetic and is pregnant with peril, but that I should ‘comprehend’ what happened and why, which is safe and neutral. These are subtle, dodgy differences, but they are important if one needs to avoid being pelted with indignation, feigned or otherwise.

Another word I chose to smother was ‘evil’. This is an occult word, meaning nothing precise or measurable, and is simply an excuse for not thinking. It signifies, in effect, ‘I don’t know’, and therefore should not be part of a writer’s vocabulary. I was shocked to hear the word used by the judge in his summing-up; that slip of judicial language deserved censure. Nevertheless, some form of vocabulary had to be found to clarify the mystery of moral degradation. In one of our

conversations, I told Nilsen that logic compelled me to allow that I might be capable of killing another person, though I hoped that such would never happen. After all, in battle it is almost a requirement, in anger, a constant risk. But I could never fathom how he could have afterwards dismembered the bodies, cut them into little bits and flushed them down the lavatory. His reaction was immediate and alarming. ‘There is something wrong with your morals if you are more annoyed by what I did to a corpse,’ he said. ‘It was far worse for me to squeeze the life out of a living man; a corpse is a thing, and it cannot be hurt or suffer. Your moral compass is upside down.’ That gave me pause for a while. It is, of course, the product of logical reasoning. But Nilsen could not see, or feel, that humans are much more than logic; they are creatures with imagination, which allows, nay compels, them to honour and respect that which had once been a life in full flow. Such a concept was totally foreign to him.

It was this same indifference to the emotional impact of his deeds, and of his words to me, that informed his remark one day, ‘You know, you’d be surprised how heavy a human head is when you pick it up by the hair’. This was the man who had been capable of getting breakfast ready, buttering a slice of toast, then lowering the heat of a pot which had been simmering the head of his last victim during the night. He was still able, before taking the dog out for a walk, to eat his toast. The murders were consistent with this moral deadness; he knew very well that what he had done was wrong, but he did not know why it mattered, why people reacted so emotionally.

A lesser display of detachment was his failure to notice how much his mother would suffer when the full details of his crimes reached the newspapers. The weekend before the trial, I went up to Scotland to visit her, and prepare her for what was about to engulf her modest, terraced house within a day or two. It was a wretched experience, although she did her best to make it sunny by cooking me a splendid dinner and gossiping about Dennis’ tender care for pet birds when he was a child. The distance between mother and son was astonishing.

The psychiatrists grappled with their conflicting definitions. Nilsen suffered from a ‘personality disorder’, some said,

without offering an explanation of what might have caused the ‘order’ to be knocked askew in the first place. Had there been a priest in court, he would have said that he knew quite well what had done it, and they called him the Devil. That brings us right back to the occult, and the absence of explanation.

Nilsen told me he was surprised that people should be so fascinated by the macabre, and spend so much time talking about it even as they condemned it. I, too, was often accused of being ‘fascinated’, another word I reject. Fascination involves abnegation of thought, permitting unwanted impressions to be written on the memory. I have quite enough memories without adding to their weight. The police, unusually, showed me the file of photographs they had taken. There was a box containing, I guessed, over one hundred images, of graduating unpleasantness. I was told to say ‘stop’ when I had had enough. I looked at the first twelve, and could go no further. But they will never be wiped from my mind, and they may well come back to haunt me in senility.

Looking back now, it is the paradoxes that perturb. I am no longer prepared to accept Nilsen’s disingenuous claim that he did not know what had caused him to be a killer. I now think he enjoyed it and the thrill it gave him. Why he should enjoy it is another matter. Moral vacuity is an insufficient answer. And yet, when I discovered the letter that had been written to the landlords complaining about blocked drains, I immediately recognised the distinctive handwriting. It was Nilsen’s. The plumbers came, and found human remains. The murderer had engineered his own arrest.

For about ten years after his conviction, I visited him in prison about once every two months. I was chastised for this, too. My reason for so doing was simple: he had opened his memories and his character to me, giving me material with which to write this book. I could not then, in all conscience, say ‘Thanks, but you are now by yourself’. The court had determined his fate; I could still be true to mine.