IŠMANUSIS MIESTAS X

PAVELDOSAUGA ŠIANDIEN

Medinės Šnipiškės - Tvaraus Šiuolaikinio Vilniaus Pavyzdys

[org. pavadinimas: Experimental Preservation]

Ieva Davulytė

Ieva Davulytė

University of Cambridge

Medinės Šnipiškės - Tvaraus Šiuolaikinio Vilniaus Pavyzdys

[org. pavadinimas: Experimental Preservation]

Ieva Davulytė

Ieva Davulytė

University of Cambridge

PIRMA

DALIS

ANTRA DALIS

TREČIA

DALIS

1. Summary in English;

2. Literature study and the MArch disertation (only in English);

3. Projekto tikslas, uždaviniai, darbo sudėtis;

4. Esamos būklės analizė ir Teisinės bazės ir reglamentai;

5. Funkcinė, erdvinė ir architektūrinė idėja bei darnios koncepcijos aprašymas;

6. Transporto ir pėsčiųjų srautų sprendimai;

7.Projektuojamų pastatų inžinerinių sistemų sprendiniai bei naudojamos išmanios technologijos;

8. Projektuojamų pastatų energetiniai rodikliai;

9. Tvarieji sprendimai bei atsinaujinančių energijos išteklių panaudojimas;

10. Projekto ekonominiai sprendimai;

11. rėmėjų produktų panaudojimas;

They [The Arcades] are the residues of a dream world. The realization of dream elements, in the course of waking up, is the paradigm of dialectical thinking. Thus dialectical thinking is the organ of historical awakening.

- Walter Benjamin

The term crisis comes from the ancient Greek word kríno, which means to decide. Even though the word crisis has acquired different meanings in different disciplines, the crisis experience typically refers to a feeling of uncertainty with a sense of urgency to take action needed to avoid or minimize negative outcomes. It is the ”crisis of historicity” that this project is concerned with: a persisting inability to integrate knowledge of history with the lived experience of the everyday. The crisis of historicity usually refers to the Western world in the late-modern period, when the cultural sphere became dominated by ”the newly organised corporate capitalism.” Yet, this project explores the cultural crisis of today within the context of transitional capitals: the former Sovietized countries of Eastern Europe. The post-independence race for progress has caused rapid economic and political transformations, resulting in institutionalisation of the slower transitioning cultural realm. As a result, there is a feeling of an increased pace of time and prescribed cultural identity that has little to do with the current way of living. In Vilnius, Lithuania, the current cultural debates are being dominated by state-imposed images of a progressive Western capital. As a result, the existing buildings, sites and neighbourhoods that do not seem to possess the expected Outstanding Universal Value do not classify as part of the presented future. Consequently, with the slightest financial interest in place, they become construction plots for whatever that would. Heritage today does not ”agree” with the present, it comes from the beautiful past and from there carries on to the beautiful future. This, is why there is a need for re-establishing historical present. Only then could it be possible to begin revaluing the qualities of today and seeing those becoming part of the past, the present and the future. Qualities that are real, of every day and even the ones of precarious nature. This essay tries to search for ways, how heritage discourse could help one to start considering the uncertain and unstable as part of our culture, especially in the case of transitional capitals.

The current cultural transformation is different from those experienced before, therefore there is a need for a constant questioning of what the present culture is, should be and how to see it. This project concerns itself with “medinės Šnipiškės”, a central neighbourhood of a transitional capital, Vilnius. It argues that - the economically insecure and socially fragile - “medinės Šnipiškės” is a defining place for today’s culture of Vilnius. The essay attempts to engage with the following questions: To what extent should heritage discourse be institutionalised? How can one explore X capacity as heritage? How are the proposed methods informing about its potential as heritage? The search for answers in itself will contribute to the broader inquiry of how heritage discourse can lead the discussion on the cultural crisis happening today in transitional capitals. The inquiry begins by investigating why “medinės Šnipiškės” could be a place defining current cultural identity of Vilnius. This is followed by a chapter reviewing possibilities for identifying ourselves with the present and investigating if heritage discourse allows that to happen. The third chapter studies conservation of heritage as a public discourse. The fourth chapter proposes two critical conservation methods to gauge the capacity of “medinės Šnipiškės” heritage and tests them as ways to reify one’s cultural present. Finally, the concluding chapter discusses the results and implications of the research.

I wrote this essay through the lens of someone who is not from “medinės Šnipiškės” but was born in Vilnius. Through the lens of someone who has no personal memories of “medinės Šnipiškės” but has been aware of its existence. Even without a close relationship to the location, this essay is undoubtedly influenced by my sensibility to Vilnius past, present and future. Also, in this essay, I see the preservationist as a critic and a determiner of culture. The preservationists choose heritage, they make decisions of what form of the present will become a memory of the future. They always do that through their personal lens. Within the scope of this essay, I am making the choice, and I am the critic. Besides caring deeply for Vilnius, my personal lens also involves an architectural background. Like Lee Friedlander’s photographs,8 this text has a shadow. It is a shadow of me, and I would like to encourage the reader to stay aware of it while reading. This is important because even though within the scope of this essay I took the role of a preservationist - I chose specific research methods, chose what to photograph, chose what to write - this essay argues that the role of the preservationist can be taken up by anyone concerned.

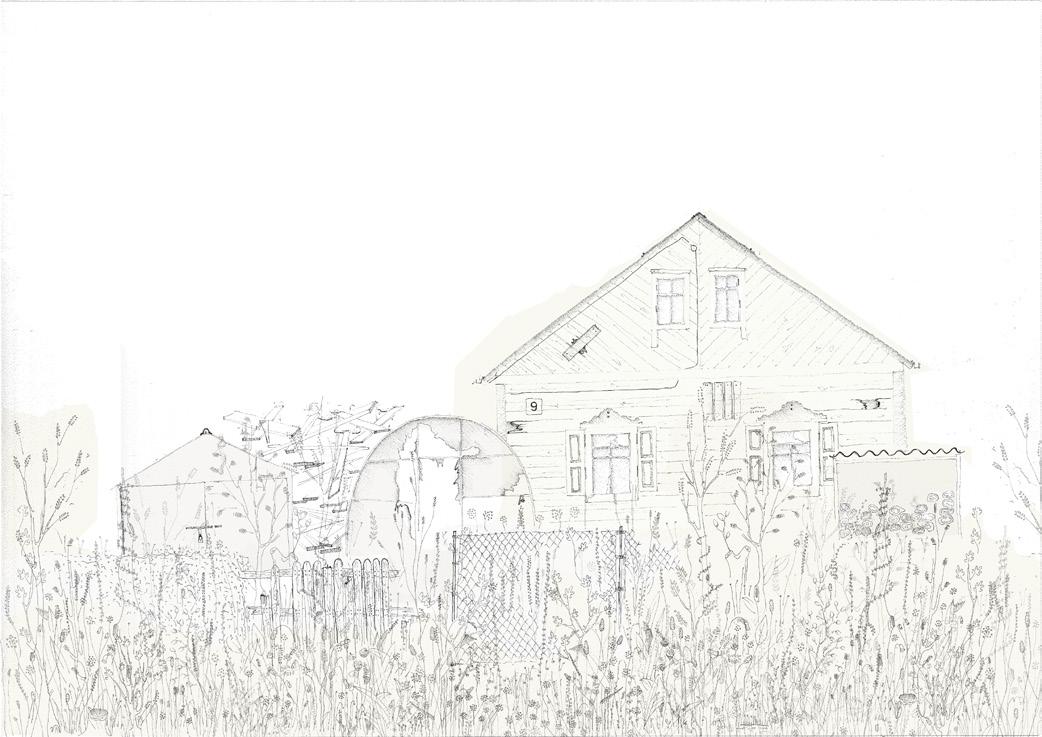

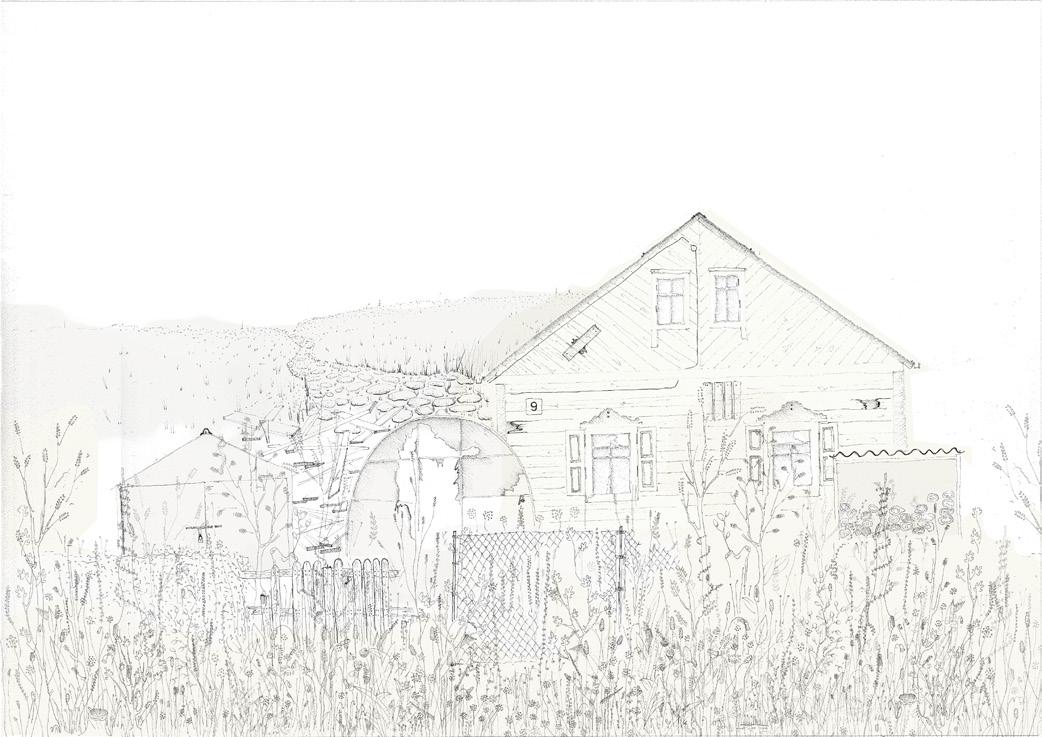

“Medinės Šnipiškės” is a place where collective maintenance is the foundation of domestic living. When an act becomes collective it acquires a broader social and spatial dimension and in “medinės Šnipiškės”, all of these constant acts of exchange have almost encrypted space to something that is hardly readable to a foreign eye and even harder to see its value. Is collective maintenance a lifestyle that provides security and comfort that many in the context of a transitional capital would be seeking? With this project I am not arguing for the informality that the current environment of “medinės Šnipiškės” provides, I aim to decrypt spaces in “medinės Šnipiškės”, identify clear values, and propose a design that would preserve them but also fit the needs of contemporary society.A neighbor mowing a shared lawn is being offered a warm lunch in exchange. This is one example of collective acts in “medinės Šnipiškės”, but it is a good one to see how spatial it can be. So even though I admit that the physical form might need to change there is a constraint to keep locals, their belongings, their habits, and their social and intergenerational connections in place. As if I would insert “medinės Šnipiškės” in Smithson’s essay on 6 East.

Think of [“medinės Šnipiškės”] as a farm building with the mostly old machines from the old farm being moved in… but with some new, for the farm processes that are new.

Think of it as a farm with the old farm workers moving in… with their ordinary old things and their ordinary new things from the ordinary shops for the domestic processes that are changing.

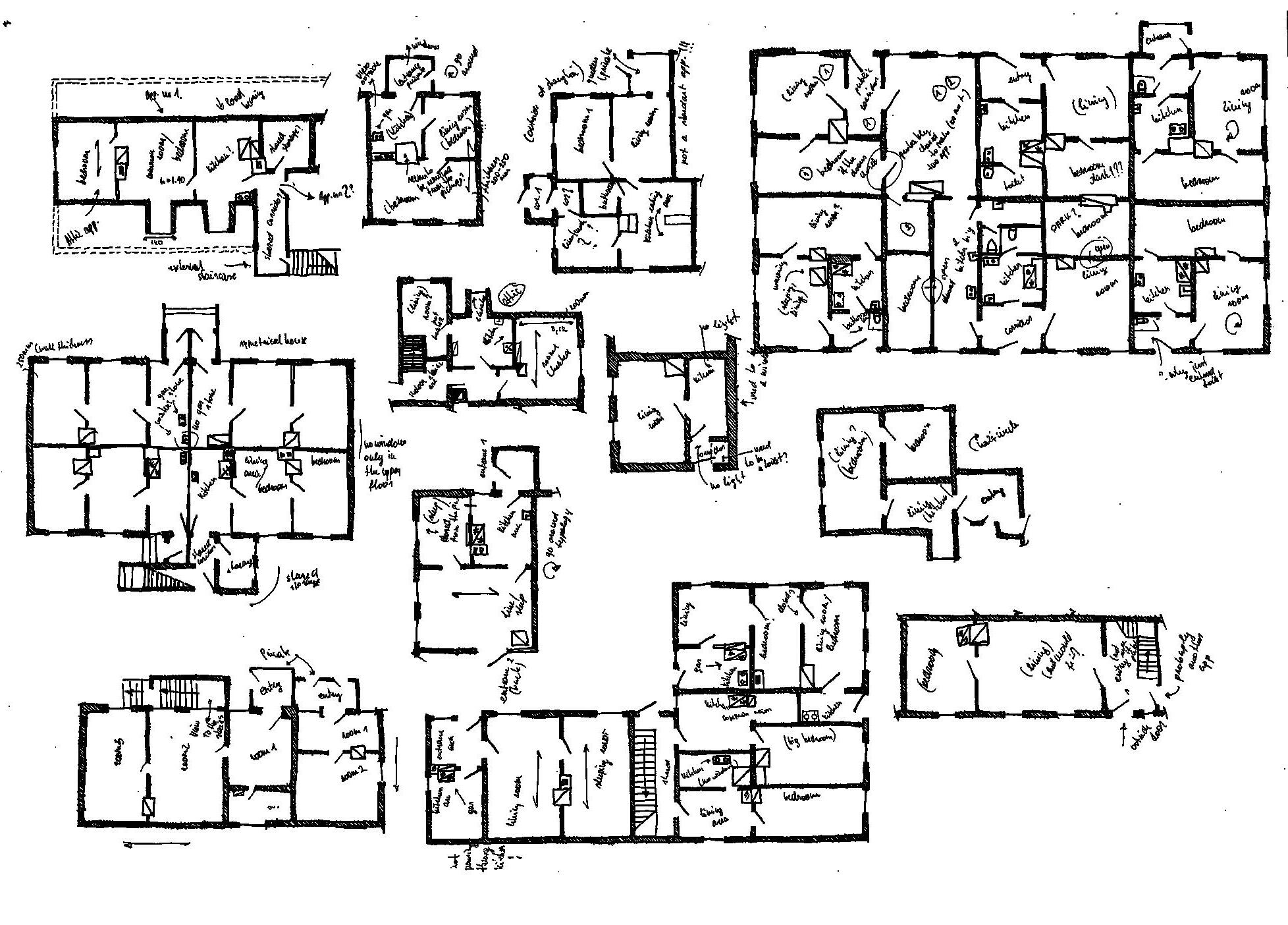

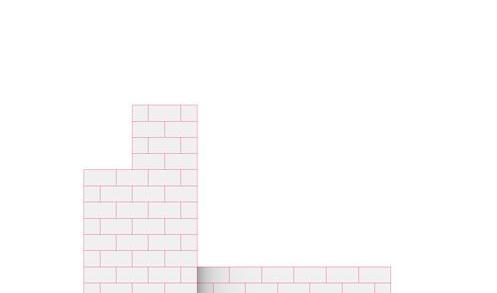

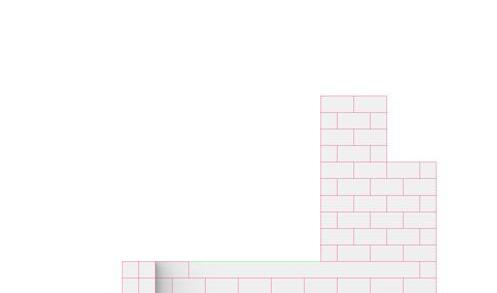

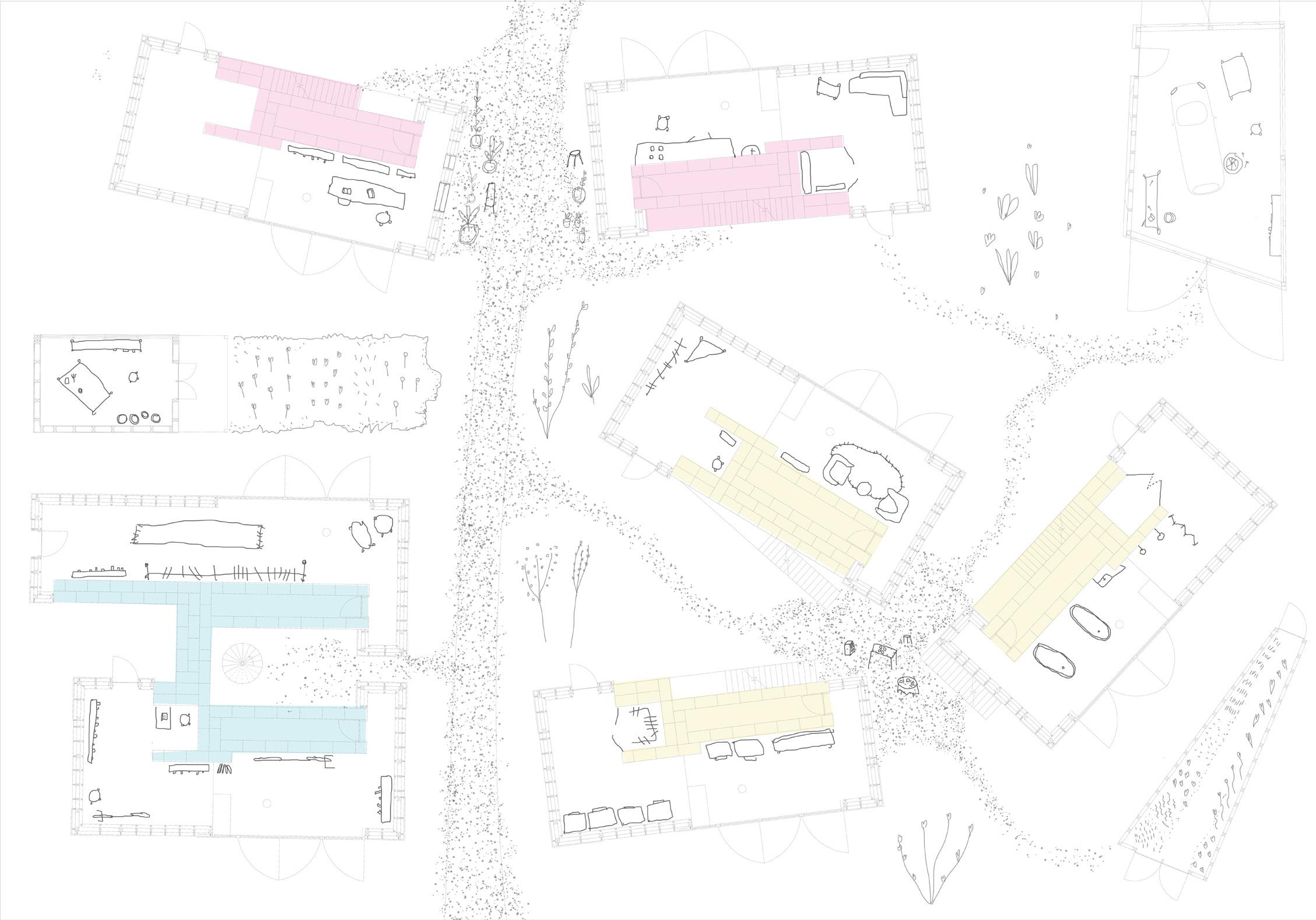

With the design project “Eperimental Preservation” I respond to Vilnius municipality interest in understanding how a city could develop such individualistic forms of urban space while both keeping the current charatcter of place as well as responding to high land price and value. The design project has a scale of a street connecting Krokuvos and S. Fino streets. Currently there is a labyrinth likeunpaved street lingering in a curved line which is hardly defined by any physical objects but rather a feeling. In reality, the complex form of the street is caused by the form of land parcel borders which due to the complex history of the place (please refer to the lit. study) are rather non-uniform (please the land parcel map in the article 4). This design imagines the scenario of needing to densify the neighbourhood and even replace some of the current houses which are not in acceptable condition, therefore the proposition mostly includes new-built structures.

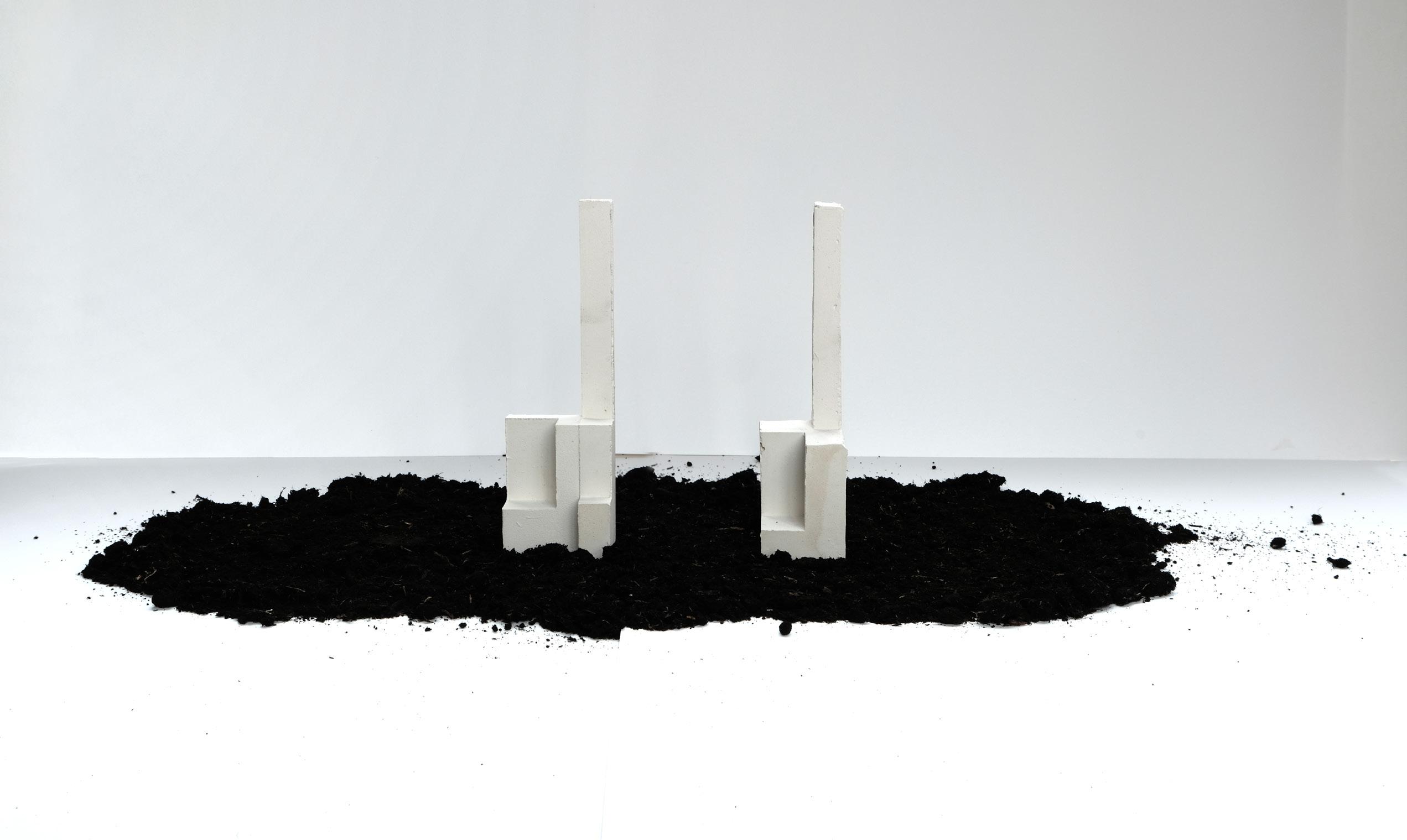

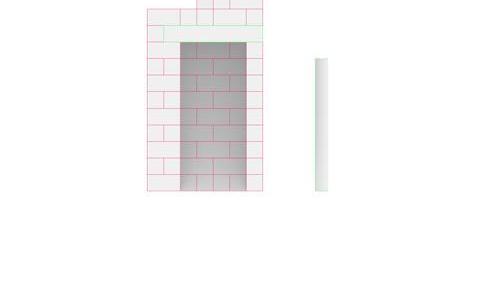

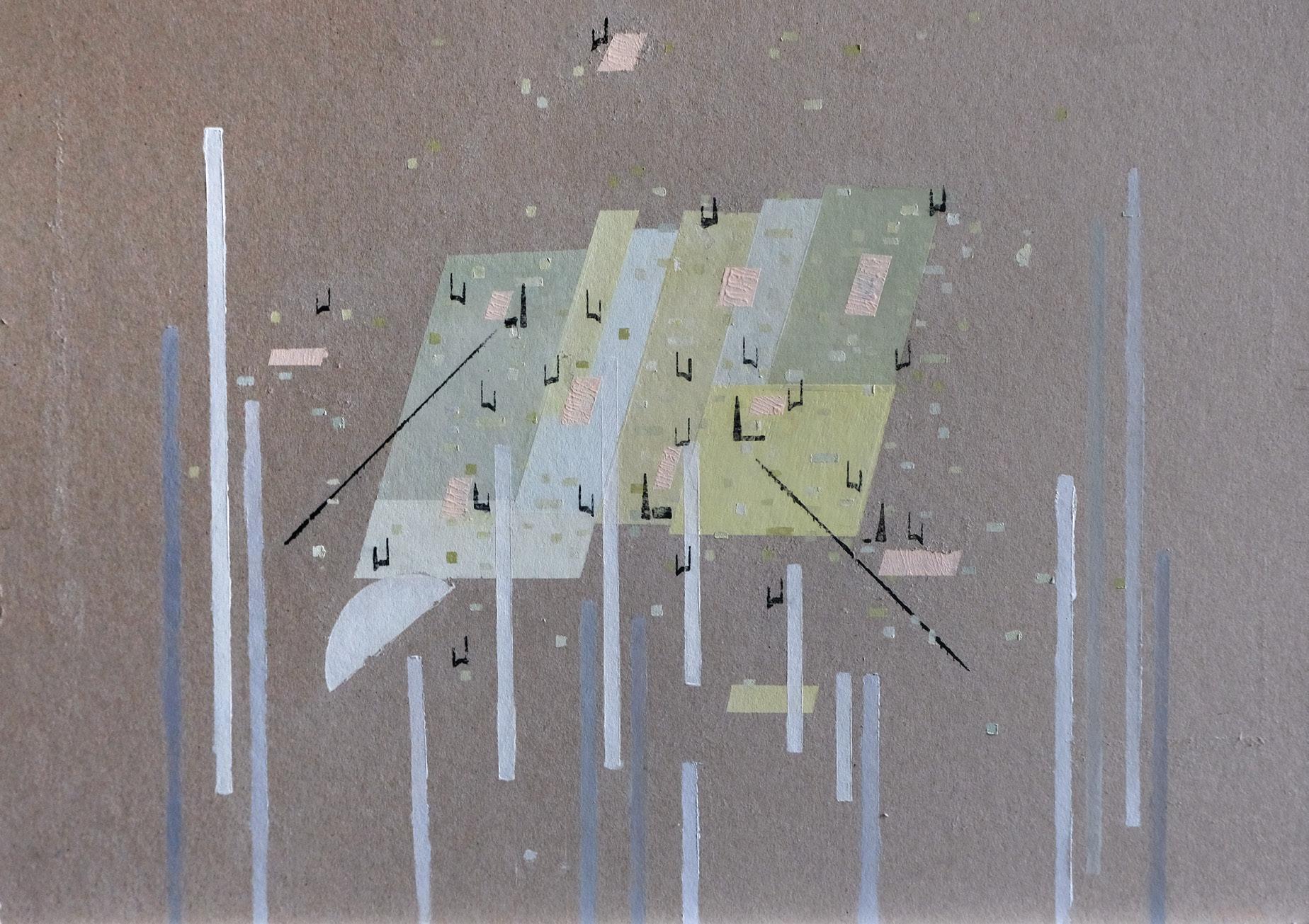

The main ddesign element that forms each of the new structure is a hearth (liet. pečius). A hearth historically has always symbolised the center of the house and household. It used to be place on which we cook, do the washing and even sleep. Hearths have always supplied households with necessary amenties for the domestic life at the time: fire, heat, warm surfaces. However these amenities for the contemporary household are not enough and burning wood for heat is seen as a risk. Therefore this project proposes asustainable way of using a harth while keeping and even enhancing it’s symbolic dimension. The hearth here supplies low-temperature heating radiating through walls of the hearth, pipes of hot and cold water as well as ventilation pipes all built in the hearth. The hearth therefore is the first element built and the most important, that is the element around which the domestic life happens.

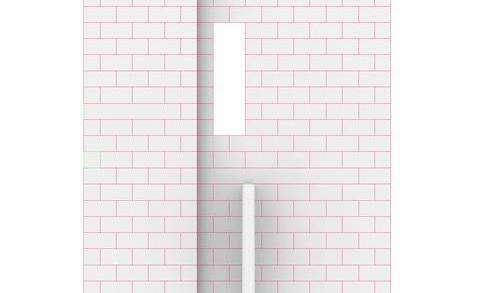

On more urban scale, hearths form different urban spaces. There are three types of them (collective, individual and a hybrid). Households can choose the level to which they would like to be exposed to the street and to their neighbours. Each house is meant to accomodate oWne to two households and meant to offer an affordable housing solution, where places like kitchen, library, living room, garden shed can be shared. Sharing has always been the strenght of this district and therefore it remains an important element of the design. All ground floor (please see the plan) is meant to be shared between the neighbours , while the second and the third floors are individual and have separate access. Since the history of independent Lithuanian urban living is rather short, this project aims to contribute to it and offer a socially and environmentally sustainable form of domestic living in a city.

Untill page 79.

0.1AReflectionofaWoodenHouseintheWindowofanOfficeBuilding. ......3

0.2AHouseEntranceinShanghaiwithaSelfBuiltAwning. ..............4

0.3ThreeHousesinShanghai:AllRegisteredasNumber17. ..............5

1.1SandandSaltMixtureinaDepotatGrinda. .....................15

1.2StatueofPetrasCvirkaStoredTemporarilyatGrinda. ................16

1.3TheCHCMeetingRoom,whichRemindsofaChapel.

1.4AnOutdoorBioMassReserveatCHC.

2.1AHistoricalMonumenttogetherwithElementsfromtheEverydayPractice ....27

2.2HistoricalMonumentsWithanElementFromtheEverydayPracticeinBetween Them. ..........................................28

2.3AHistoricalMonumentSupportedbyanImprovisationalHand-MadeFixture

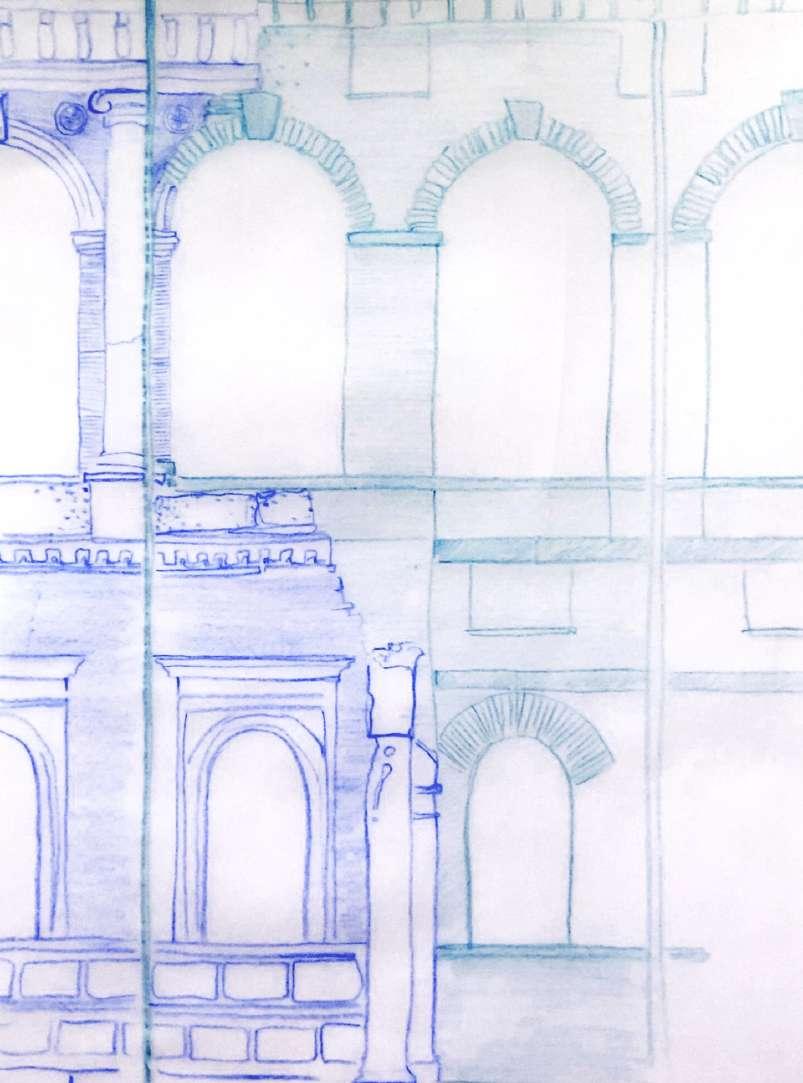

3.1PencilSketchofaFragmentoftheSouthernSideofAltePinakothek.Theoriginal -inblue;thereconstructed-ingreen).

3.2PalazzoAbatellis,IndoorExhibitionSpace.

3.3PalazzoAbatellis:aFragment. .............................38

3.4PalazzoAbatellis,InnerPatioSpace.

3.5PalazzoAbatellis,OneoftheEntrances.

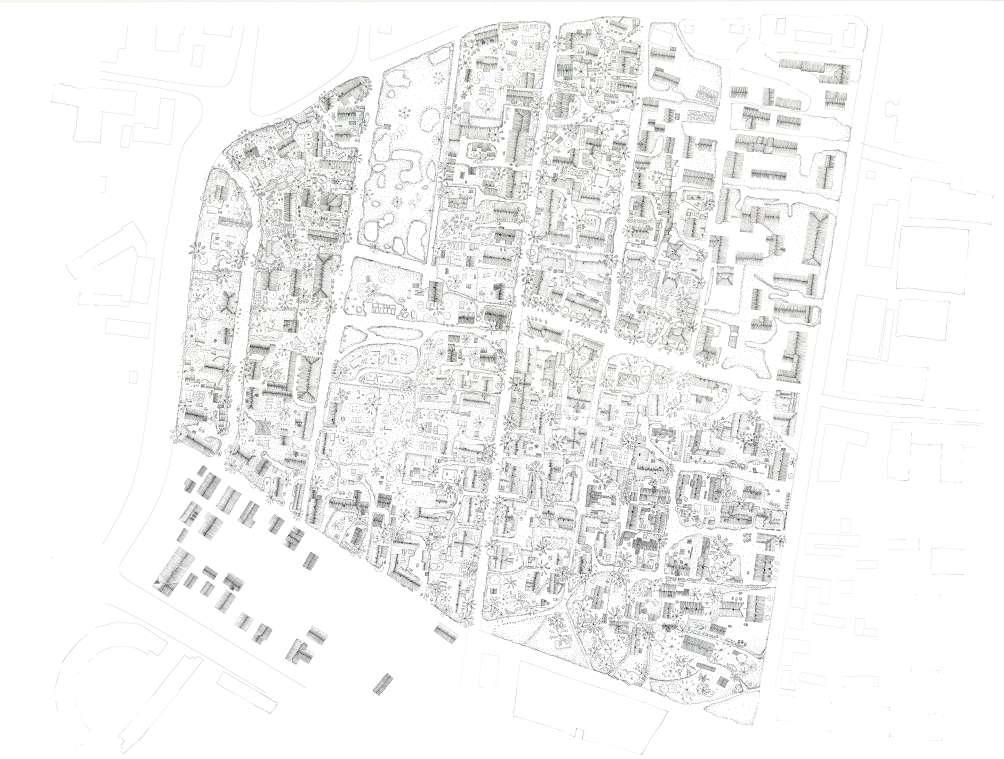

4.1Penonpaper.NeighbourhoodPlan.

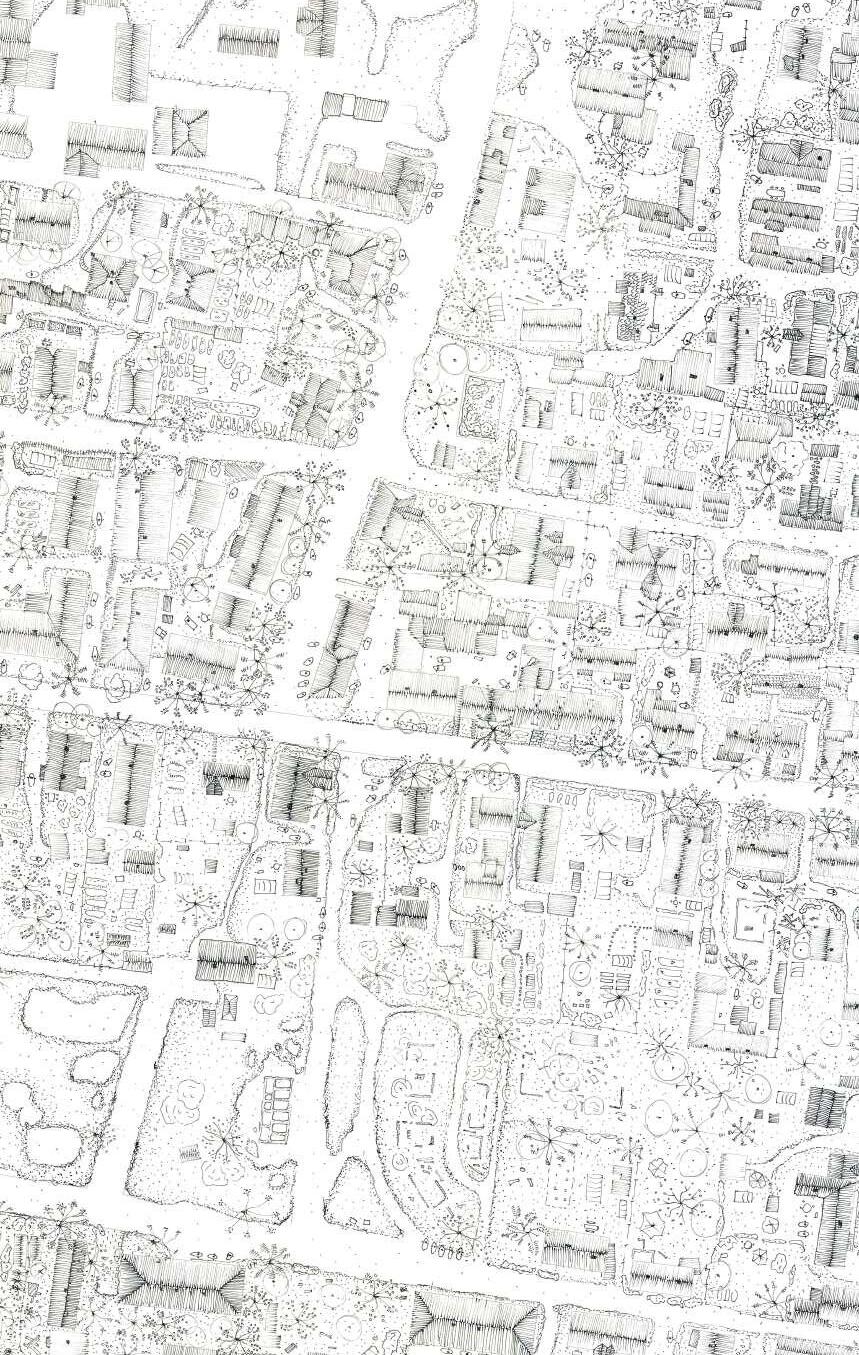

4.2Penonpaper.NeighbourhoodPlanZoomed-In.

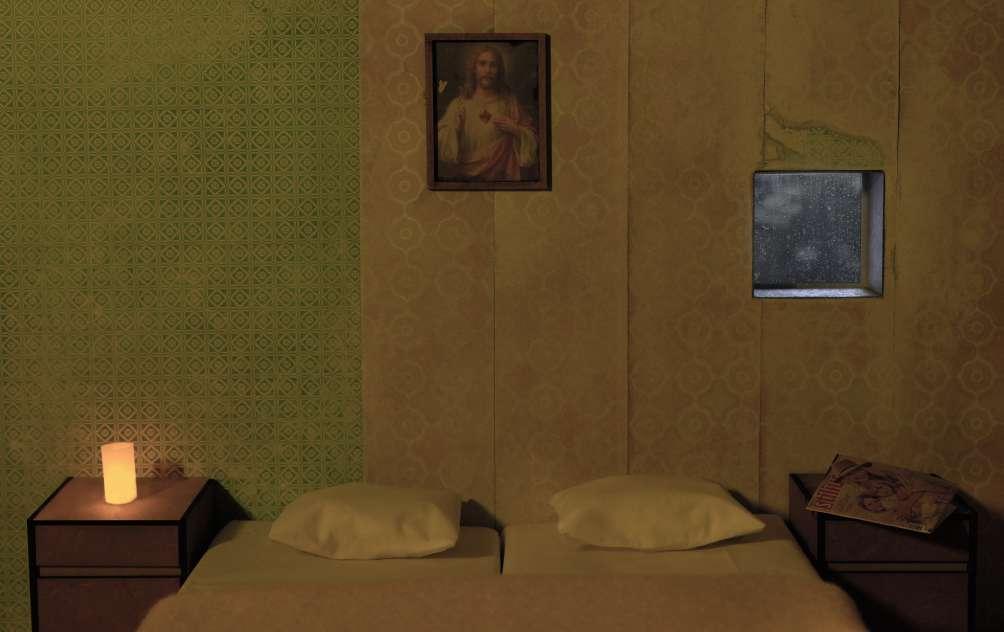

4.3APhotographofAMiniatureModel:anImaginedBathroominaGreenhouse.

4.4APhotographofAMiniatureModel:anImaginedCafeteriainanExisting AbandonedHouse. ...................................47

4.5APhotographofAMiniatureModel:aFragmentofanImaginaryBedroom. ...48

4.6TheExhibition:LaundrythatisCuratedaswellasUncuratedLaundryinthe Background. ......................................52

4.7TheExhibition:LaundrywithPrintedDrawingsonit. ...............53

4.8TheExhibition:anExhibitionSignSaying”EXHIBITION”onthetable. .....53

4.9ActsofMaintenanceinShanghai:PhotoEssayMadewhileontheField. .....56

4.10ActsofMaintenanceinShanghai:PenonPaper. ...................57

Thispageisintentionallyleftblank.

They[TheArcades]aretheresiduesofadreamworld.Therealizationofdream elements,inthecourseofwakingup,istheparadigmofdialecticalthinking.Thus dialecticalthinkingistheorganofhistoricalawakening.

Theterm crisis comesfromtheancientGreekword kríno,whichmeans todecide.Even thoughthewordcrisishasacquireddifferentmeaningsindifferentdisciplines,thecrisis experiencetypicallyreferstoafeelingofuncertaintywithasenseofurgencytotakeaction neededtoavoidorminimizenegativeoutcomes.2 Itisthe”crisisofhistoricity”thatthis essayisconcernedwith:apersistinginabilitytointegrateknowledgeofhistorywiththe livedexperienceoftheeveryday.3 ThecrisisofhistoricityusuallyreferstotheWestern worldinthelate-modernperiod,whentheculturalspherebecamedominatedby”thenewly organisedcorporatecapitalism.”4 Yet,thisessayexplorestheculturalcrisisoftodaywithin thecontextoftransitionalcapitals:theformerSovietizedcountriesofEasternEurope.The post-independenceraceforprogresshascausedrapideconomicandpoliticaltransformations, resultingininstitutionalisationoftheslowertransitioningculturalrealm.Asaresult,thereis afeelingofanincreasedpaceoftimeandprescribedculturalidentitythathaslittletodowith thecurrentwayofliving.

InVilnius,Lithuania,thecurrentculturaldebatesarebeingdominatedbystate-imposed imagesofaprogressiveWesterncapital.Asaresult,theexistingbuildings,sitesand neighbourhoodsthatdonotseemtopossesstheexpected OutstandingUniversalValue5 do notclassifyaspartofthepresentedfuture.Consequently,withtheslightestfinancialinterest inplace,theybecomeconstructionplotsforwhateverthatwould.Heritagetodaydoesnot ”agree”withthepresent,itcomesfromthebeautifulpastandfromtherecarriesontothe

beautifulfuture.This,iswhythereisaneedforre-establishinghistoricalpresent.Onlythen coulditbepossibletobeginrevaluingthequalitiesoftodayandseeingthosebecomingpart ofthepast,thepresentandthefuture.Qualitiesthatarereal,ofeverydayandeventheones ofprecariousnature.Thisessaytriestosearchforways,howheritagediscoursecouldhelp onetostartconsideringtheuncertainandunstableaspartofourculture,6 especiallyinthe caseoftransitionalcapitals.

Thecurrentculturaltransformationisdifferentfromthoseexperiencedbefore,therefore thereisaneedforaconstantquestioningofwhatthepresentcultureis,shouldbeandhow toseeit.7 ThisessayconcernsitselfwithShanghai,acentralneighbourhoodofatransitional capital,Vilnius.[0.1,0.2,0.3]Itarguesthat-theeconomicallyinsecureandsociallyfragile -Shanghaiisadefiningplacefortoday’scultureofVilnius.Theessayattemptstoengage withthefollowingquestions:Towhatextentshouldheritagediscoursebeinstitutionalised? HowcanoneexploreXcapacityasheritage?Howaretheproposedmethodsinformingabout Shanghai’spotentialasheritage?Thesearchforanswersinitselfwillcontributetothebroader inquiryofhowheritagediscoursecanleadthediscussionontheculturalcrisishappeningtoday intransitionalcapitals.TheinquirybeginsbyinvestigatingwhyShanghaicouldbeaplace definingcurrentculturalidentityofVilnius.Thisisfollowedbyachapterreviewingpossibilities foridentifyingourselveswiththepresentandinvestigatingifheritagediscourseallowsthatto happen.Thethirdchapterstudiesconservationofheritageasapublicdiscourse.Thefourth chapterproposestwocriticalconservationmethodstogaugethecapacityofShanghai’sheritage andteststhemaswaystoreifyone’sculturalpresent.Finally,theconcludingchapterdiscusses theresultsandimplicationsoftheresearch.

IwrotethisessaythroughthelensofsomeonewhoisnotfromShanghaibutwasbornin Vilnius.ThroughthelensofsomeonewhohasnopersonalmemoriesofShanghaibuthasbeen awareofitsexistence.EvenwithoutacloserelationshiptoShanghai,thisessayisundoubtedly influencedbymysensibilitytoVilniuspast,presentandfuture.Also,inthisessay,Iseethe preservationistasacriticandadeterminerofculture.Thepreservationistschooseheritage, theymakedecisionsofwhatformofthepresentwillbecomeamemoryofthefuture.They alwaysdothatthroughtheirpersonallens.Withinthescopeofthisessay,Iammakingthe choice,andIamthecritic.BesidescaringdeeplyforVilnius,mypersonallensalsoinvolvesan architecturalbackground.LikeLeeFriedlander’sphotographs,8 thistexthasashadow.Itisa shadowofme,andIwouldliketoencouragethereadertostayawareofitwhilereading.Thisis importantbecauseeventhoughwithinthescopeofthisessayItooktheroleofapreservationist -Ichosespecificresearchmethods,chosewhattophotograph,chosewhattowrite-thisessay arguesthattheroleofthepreservationistcanbetakenupbyanyoneconcerned.

Figure0.2: AHouseEntranceinShanghaiwithaSelfBuiltAwning.

Figure0.3: ThreeHousesinShanghai:AllRegisteredasNumber17.

Thereishardlyaregionintheworldthathasundergoneamoredramatictransformationover thepasttwentyyearsthantheregioncomprisingtheformerSovietizedcountriesofEastern Europe.1 Theterm transitionalcountries hasemergedtostudytheprocessandconsequences ofsuchtransformation.Theturbulenttransitionperiodstartedwiththeabruptwithdrawal ofcommunismin1989andthesubsequentdissolutionoftheSovietUnion.2 Eventhough eachofthetransitionalcountriessoondifferentiatedfromoneanotherduetotheirdegreeof democratizationandindividualprogresstowardthefreemarket3 ,thespeedoftransformation andtheextentofsocialturbulenceaccompanyingitarecommonfeatures.4 Theattentionof thisessayisdevotedtoLithuania,wherethestudywascarriedout.However,thereisnoaim toprioritizethecontextofLithuaniaoverthatofanyothertransitionalcountry.Currently, literatureontransitionalcountriestendstofocusonthepassagefromthecentralizedplanned economytothefreemarket.Instead,thisessayarguesforamoremultidimensionalapproach.

Whathappenedwithcultureduringthetransformation?Thetransitioninthisessayisseen asacomplexprocessencompassingeconomic,political,andideological,aswellascultural aspects.5 Infact,havingtheculturaldimensioninmindwhentalkingabouttransitioniscrucial, sinceitdoesnottransformasrapidlyasthepoliticaloreconomicaspects.6 Theadjustment ofculturedependsonsocietyanditscertainculturalorientations,norms,principles,and values.7 Muchlikeinthecasesoftheothertransitionalcapitals,theauthoritiesinLithuania haveoverestimatedtheproportionofsocietybenefitingfromthepromisedbrightfuture,as wellaspeople’swillingnesstoendurethelackofagencythatitprovides.8 Giventheabove, theprojectedprogressiverealitywithitsoften-rushedimplementationhasdominatedVilnius’

socialandculturalspherefordecades.Namely,itistheendlessconstructionofthefuturethat definesthecurrentstateofVilnius.ItisasifVilniushasenteredtheglobalstateofwhatRem Koolhaascalls“Junkspace”:astateof‘endlessbuilding’thatseemstoneverclose.9 HalFoster putsitconcisely:

Junkspacethusconcernstimeasmuchasspace:itisaneffectofthecontinual transformationofspaceaccordingtotheacceleratedtemporalityofconsumption, nottomentionoftheprojectedtemporalityofspeculation.InJunkspaceupgrades aresofastthattheyaredifficulttodistinguishfromthebreakdowns;‘insteadof development,itoffersentropy’,and“underconstruction”becomesapermanent stateofaffairs.10

Thelackofknowledgeaboutthefutureisscaryandhardtoacknowledge.Consequently,this fearoffacingthefutureleadstoinsensitivetransformationoftheenvironmentintowhatseems favourableandprovidescertainty.Forinstance,Vilniusasatransitionalcapitalhasundergone adramaticurbanredevelopmentbecauseofagranddesiretoattainanimageofWestern globalcapital.11 Soonenough,theprojectedfuturehasstarteddefiningthepresent.Even thoughthegrandshifthaspassedandcurrentlythedevelopmentofVilniusisfollowingamore ”natural”pace,theconsequencesofthemajortransformationremain.12 Thisessayfocuseson thefollowingone.Theauthoritiesandinstitutionshavesettheimaginedfutureasthefocus forthepresent,aswellashaveadjustedpoliciesaccordingly,disregardingunderprivileged communities,althoughthetransitionbeingoneofthemainreasonsoftheirdistress.

ObservingVilniusinitsentiretyunfortunatelyrequiresabiggertimeframethanthis researchoffers.Therefore,followingtheadviceofAldoRossiin”TheArchitectureofThe City”,thisstudywillstartlookingatcurrentVilniusthroughtwourbanartefacts: Grinda and CHC.Grindaisamunicipalcompanyanditsmaintaskistoprovidemandatoryinfrastructure maintenanceservicestothecityofVilnius.CHC,alsoknownasCentralHeatingCentre Vilnius,isthemainheatsupplierforthecity.Theaimistoseewhattheirtemporalandspatial complexitiesrevealaboutthecurrentculturalconditionofVilnius.

GrindaisthebackstageofVilnius.TwoemployeesofGrindawelcomemeintotheterritory. ThefootprintofGrindacurrentlycomprisesaround20acresofland.Walkingthroughthose 20acresfeelslikewalkingthroughVilnius.WeenterGrindathroughanenormousfieldof cars.Carsofdifferentsizes,differentshapesbutallinorange.Irealisethatthesearethesame carsIseehummingaroundVilniusstreetseveryday:collecting,cleaning,distributing,fixing, shipping,andevenmore.Continuingfurther,Inoticemountainsofsandandsalt.[1.1]It meansVilniusispreparedforwinter.Whilewanderingthrough,westepongrass-thisisa fieldforVilniuscityrabbits.Weleavetherabbitsundisturbedandcontinueourwalktowards

anenormousstatueofJohnLennon.Inthebackground,wesuddenlyspottallhuman-like objectsallcoveredinblackcloth.Whatarethose,Iwonder.Iamallowedtoliftthecloth andpeakthrough.[1.2]ItisastatueofPetrasCvirka:aprominentLithuanianwriterwho hadaffiliationswiththeSovietgovernment.Nexttoit,Iseemoreofthosestatuesthatjust amonthagowereapartofVilniuscityscapebutarenowallremovedduetotherecently establishedpolicyofculturaldesovietization.ThestatueofJohnLennontogetherwiththese remnantsoftheSovieterastandherewithnocleardestiny.Pastthestatues,weapproacha pond.Thereisapathalongthepondwhichwefollow.Hundredsoftreeguardsliealong thispath.”Whyareyoukeepingthem,”Iask.Theresponseishonestandclear:”Thetree guardswerecollectedlastyearbecauseofthecurrent free-the-trees policy.Theywillchange theirmindssoonanyway.”Wecontinuewalking,climboverafence,continuewalkingagain. GrindaemployeeexplainsthatthislocationistemporaryandthatGrinda’splaceofresidenceis plannedtochangeinthenearfuture.Immediatelyafterthiscomment,wediscoverasitefullof differentobjects,alllaidoutoutdoorsonthelawn.Bricksofdifferentcolours,tilesofvarious sizes,steelpiecesthatdonotremindmeofanythingfamiliar,alotofthings.Apparently,these aretheleftovers:materialsthatweremeanttobeinstalledinthestreetsbutwerenotdueto differentreasons.TheyarenowpartofthelandscapeofGrinda:temporarilywaitingtobe givenawayormaybesoldormaybetofindtheirplacesomewhereinthestreetsofVilnius again.Nooneknowstheirdestiny.WhatkeepscomingbacktomymindisthatGrindahosts allthoseobjectstemporarily,butisatemporaryplaceitself.Beforewepartways,oneofthe employeesofGrindasayswithasmile:”IfyouseesomethingonthestreetsofVilniusandyou don’tknowwhoisgoingtotakecareofit-it’sus”.Itwouldbeimpossibletolistallthethings Grindadoes.ThefactthattheobjectswefoundareallstayingatGrindajusttemporarily, becauseofthecommonfeelingthatthepolicywillsoonchangeagain,indicatesthetemporal natureofVilniustoday.GrindaisaninstitutiondealingwithandreflectingVilnius’temporal complexity.

”WelcometothemonsterofVilnius,”IamgreetedbyoneoftheemployeesofCHC. CentralHeatingCentreisresponsibleforsupplyingheattoover200,000clientsandover7,000 buildings,whichaddsupto758,000metersofpiping.Itisavastlandscapewherehorizon becometangledinpipes,chimneysreachthesky,andyellowvestedfigurespopupunexpectedly intinygapsofmachinery.Iamtakingaguidedtourthroughtheterritory.Whilewalking,I amalwaysfollowedbyagroupofpipesonmyright.Idonotknowwhatthosepipescarry, iftheirsurfaceishotorcold,andwheretheylead.Thepipesmakealeftturn,weturnleft too.WeturnonemorecornerandfindourselvesinwhatIwouldcomparetoamassivecar park.Yet,itisnotfilledwithcars,itisfilledwithhillsofbio-mass.IamnotsurewhyIamso surprised.MaybeitisaheavydoororayellowsignthatIwasexpectingtowarnmeforthis

suddenswitchofscenery.Thereisawallobstructingthehorizonandseparatingtheasphalt groundfromthenaturallandscapebehindit.Yellowpaintedbutsmudgedlinesalsoimply somesortofboundaries.[1.4]Inoticeaverysmallchimneywhichappeartobeconnectedto therecentlyacquiredbio-massboiler.Weleavethehillylandscapeandwalkout,following theasphaltpath,nowcoveredinash.Asthelastpartofmyvisit,Igettolistentoalectureon ashanditsreusepotential.”Thisisourchapel,”ourguidesayswithasmileandcontinues, ”Itisjustsomeplacewedecidedtoholdourmeetings.”Ametalgateopens,andsoonweare walkingdowntheaisletofindseatsforthelecture.[1.3]Whydoesthisplaceraisesomany questionstome?Maybeallheatingstationsacrosstheglobehavesimilarstructures,Idon’t know.Afterthinkingaboutthisforawhile,Ihaveaguess.CHCisavastlycomplexplace, feelschaoticanddisorientingforapasser-by,yetitisthesameplacethatprovidesthepasser-by withastablesupplyofwarmthandcomfortbackhome.Withthepipesimpossibletounknot, naturalhillsofbio-massinthecarpark,andstrangenessofCHC’scontemporaryapplications, thisheterogeneousandchaoticinfrastructureofthings,buildingsandpeoplegenerate”the ambientenvironmentofeverydaylife.”13

ThankyouforkeepingVilniusalive!14 GrindaandCHCarecustodiansofVilnius,highly importantforthefunctioningofthecity.First,Vilniuswithitssocio-economiccontextis changingatapacethatistoofasttoexitthestateoftemporalityandthatisreflectedinthe visitatGrinda.Second,CHC,justlikeVilnius,isacomplexsystemofinfrastructure,whichis heterogeneousandincomprehensible,butprovidesonewithasenseofidentityandstability. Inotherwords,withinanever-changingreality,thereisasenseofstabilitythatiscreated bysomethingconvolutedinitsessence.Theeverydayintimesofchangeisnotnecessarily definedbystabilityorclarity,butratherthroughcomplexity.Thisraisesaquestion:through theconstantlyshiftingrealities,howcouldatransitionalcapitalestablishasenseofcultural identity,evenifthecurrentcultureisbasedonvalueslikeuncertaintyandheterogeneity.To evenbetterunderstandtheculturalpresentofatransitionalcapital,thisstudywillfocusona particularneighbourhoodinVilnius,calledShanghai.15

RadicalurbantransformationinVilniushasincreasedsocialinequalityaswellascaused spatialcontradictions.16 Theseconsequencescanbeidentifiedbystarkcontrastswithinthebuilt environment,whichisoneofthedefiningfeaturesofShanghai.17 Consequently,thecomplex socialandspatialconditionofShanghaihasinfluencedaparticularwayofliving,thatisoften referredtoas rural. 18 Unfortunately,theruralcharacterhasnothelpedShanghaiinensuring itsfuture:currentlyonly5%ofbuiltstructuresareconsideredasheritage,withtherest95% expectedtobedemolishedintheupcomingdecades.19 HalFoster’sterm”pointsofsuspension” mightbeusefultounderstandthecurrentsocio-culturalpositionofShanghai.

Evenasmodernityerasestracesofhistory,italsoproduces“pointsofsuspension”

thatexposeitsunevendevelopmentor,rather,itsunevendevolutionintosomany ruins.20 .

Such“pointsofsuspension”,orrather“blindspots”arecentralinJoachimKoeaster’sart.The term blind means“obstructiontosight”21 andtheterm“blindspots”suggeststhatthosethat arenormallyoverlookedcanstillprovideinsights.22 JoachimKoesterseesthese”blindspots” asunsettledplaces,whicharecombinationsofsomethinguncannyandunusual,“symptomatic ofaneverydaykindofhistoricalunconscious”.23 Fosteralsonotesthatthereisasortofforensic gazesignificantinKoester’swork,onlythecrimehereistheone”ofcapitalistjunkspace,state suppression,andgeneraloblivion.”24 ShanghaiisacrimesceneandthepeopleofShanghaiare witnesses.ItispeopleofShanghaiwhoindeedhavewitnessedtherelentlessandhistorically unconscioustransformationofVilnius.asAlexanderKlugeputsit,thereisnothing”more instructivethanaconfusionoftimeframes.”25 Ultimately,althoughShanghai’ssocio-economic stateisincrisisandneedssupportfromthestate,theneighbourhoodshouldbeseenasan importantculturalwitnessnevertheless.

Thename Shanghai iscriminalised,andthereareother”moreneutralnames, withoutburdensomeconnotations.”26

Theaboveisacommentreceivedfromascholarwhileconductingthefieldworkforthisessay. Yet,thisessayarguesthatitistimetomakethedecisiontoexposethefactthatthepresent cultureofcitiesissometimesburdensome.Thisessayinvitesthereadertothinkofwaystohow onecanachieve”historicalawakening”27 andtalkabouttheactualpresentanditscultural values,evenifthesubjectisatcrisis.

Shanghai’sfuturecameintoquestionwhen,followingtherapidexpansionofVilnius territory,in2008,Vilniusmayorofthattimeinitiatedaradicaldevelopment:buildinga brand-newcitycentreofVilnius.Thevisionwasformed,andimplementationstartedhastily. Astudyofthefutureurbanparametersofthisbrand-newcentrewasinitiatedin2008 andinmid-2009itwasalreadypresentedtothepublic,whereitwasconceivedashighly controversial.28 Thecritiquecomprisedcommentsontheconsequencesofsuchintervention beingirreparable“forthecontinuityoftheidentityofVilniusandfurtherformationofa qualityimageofthecapitalcity”.29 Thedecisiontoproceedwiththeplancompletelyignored thecritiquesofurbanplannersanddisregardedtheculturalandhistoricalvalueofŠnipiškės district.30 Followingthemoveofthemunicipality’sheadquarterstothenewcentre,multiple banksandbusinessesmovedtheirmainofficestoo.Consequently,manyvernacularbuildings intheareaweredemolishedtomakespaceforthenewexpandingdistrict.Aspartofabigger transformation,thisshiftofVilniusfromthehistoriccentretoanewlyconceivedcommercial centrehasimpactedtheculturalrealityofVilnius,31 aswellasredefinedtheimageofitsdirect

surroundings,whichincludeShanghai.Today,Shanghaiisseenasadistinctenclavepositioned ontherightbankoftheriverNeris.SomeofShanghai’sdirectsurroundingscurrentlyinclude agrowingclusterofskyscrapers,anewseatofthecitygovernment,and”Europa”complex inhabitingabusinesscentre,shoppingmall,andluxuryflats.Asmentionedabove,the Shanghaiitselfissubjecttocurrenturbanplanningproposalsthatseetheneighbourhood withitssurroundingsasaprestigiousareaopenforbusinessandluxuriousliving.Shanghaiis surroundedbyurbanelementsthathavebecomeculturalsignifiersofthecountry’stransition toamarketeconomyandacceptanceoftheEuropeanUnionin2004.32 Shanghaiactsalmost likeaghost.Withitspresence,ShanghairemindseveryoneontheonehandhowVilnius wouldlookandfeellikeiftherapidcommercializationhadnothappenedandontheother, whatconsequencesthecommercialisationhasbrought.Putdifferently,Shanghaiechoes somethingthattherusheddevelopmenthasabandonedandavoidfacing:thesocio-cultural reality.Let’shaveacloserlookatthehistoryofShanghai’sdevelopmentandifitcouldbe consideredculturallyvaluable.

ShanghaifindsitselfinsideŠnipiškėsdistrict.Šnipiškėsishistoricallyoneoftheoldest suburbsofthecapital.Itstarteddevelopinginthe16thcentury,mostlyduetowarehousesfor merchandisebeingplacedontherightbankoftheriverNeris.33 AswascommoninVilnius, thestudyofthehistoricalplansofVilnius(1737,1784-1790,1798)indicatesthatmostofthe buildingsintheformersuburb,theneighbourhoodofŠnipiškės,werebuiltusingwood.34 It followsthatŠnipiškėsisseenasanillustrativecaseportrayingthehistoricalpeculiaritiesof Lithuanianwoodenvernaculararchitectureusingwoodasthemostaccessible,easy-to-handle, andcost-effectivebuildingmaterial.35 Eventhoughtherewereclayandlimepitslocatedin thedistrictandtheneighbourhoodwasbusyrunningbrickandtilemanufacturingworkshops, brickwasnotseenasasuitablematerialforresidentialconstruction:itsthermalconductivity wasfivetimeshigherthantheoneofwood,itwasmorecostlytomanufacture,andittookmuch longertoworkwith.Therefore,brickworkbecameperfectforhearthpartmanufacturing.In fact,whilewalkinginShanghaitoday,onestillnoticesthatmostofthehousesinShanghai arebuiltusingtimberandhavehearthsastheirmaincentralelement.Besidesthehouses beingculturallandmarksoftemporalcontinuity,thecontinuityinbuildingtraditionisalso prominent. EventhoughShanghaiisnotacentreforclayandceramicworkshopsanymore, bycontinuallytakingcareofthehouses,Lithuanianbuildingcultureisstillbeingpractisedin Shanghaitoday.

Mostofthewoodenarchitecturethatisstillstandingtodaywasbuiltbetween1890 and1930andbecamehometoalargeJewishandPolishpopulation.Afterasevere depopulationduringandafterWorldWarII,theemptywoodenhouseswereusedbythe Sovietstateasareserveoftemporaryhomestoresolvehousingshortages.Thedomestic

spaceswereredistributedtoaccommodatealargeruralpopulation,whichwasbroughtfrom LithuanianvillagesorotherpartsoftheSovietUniontoprovidealabourforceforthequickly industrializingVilnius.Denselivingconditionsresultedinaconstantneedforrepairsand sharingofcommonspacesandbasicfacilitieswithneighboursofdifferentages,backgrounds, andethnicities.WiththefalloftheSovietUnionin1991,privatizationbroughtanother chanceforre-adjustments.Between2000and2007arapideconomicboomledtothewooden housesbeingburnedfornewconstructionstohappen.VaivaAglinskaswrites:”Infact,cases ofarsonthatclearedspacefornewconstructionsweresofrequentthatthenumberoffiresin thedistrictinthefirstdecadeofthe21stcenturyexceededthenumberoffiresovertheentire nineteenthcentury.Someresidentsjokedinajadedtonethatthesefiresbecameatraditional partoftheŠnipiškėslandscape.”36 Afterthecrisisin2008,whenthehousesstoppedburning, peoplehadtostartreadjustingtheirhomesagain,foraseeminglymorecertainfuture. Somehouseholdsrenovatedthehouses,somebuiltadditionaltemporarystructuresorfences fragmentingthespaceand,inthisway,formingthecurrentspatialcondition:adynamic labyrinth-likewebofspaces.Shanghaiwasatemporaryplacesinceitscreation.Thefearof demolitionhasalwaysdefinedtherealityoftheinhabitantsofShanghai. Theuncertaintyof thefuturehashauntedShanghaifordecadesandisreflectedinitsmaterialfabrictoday.

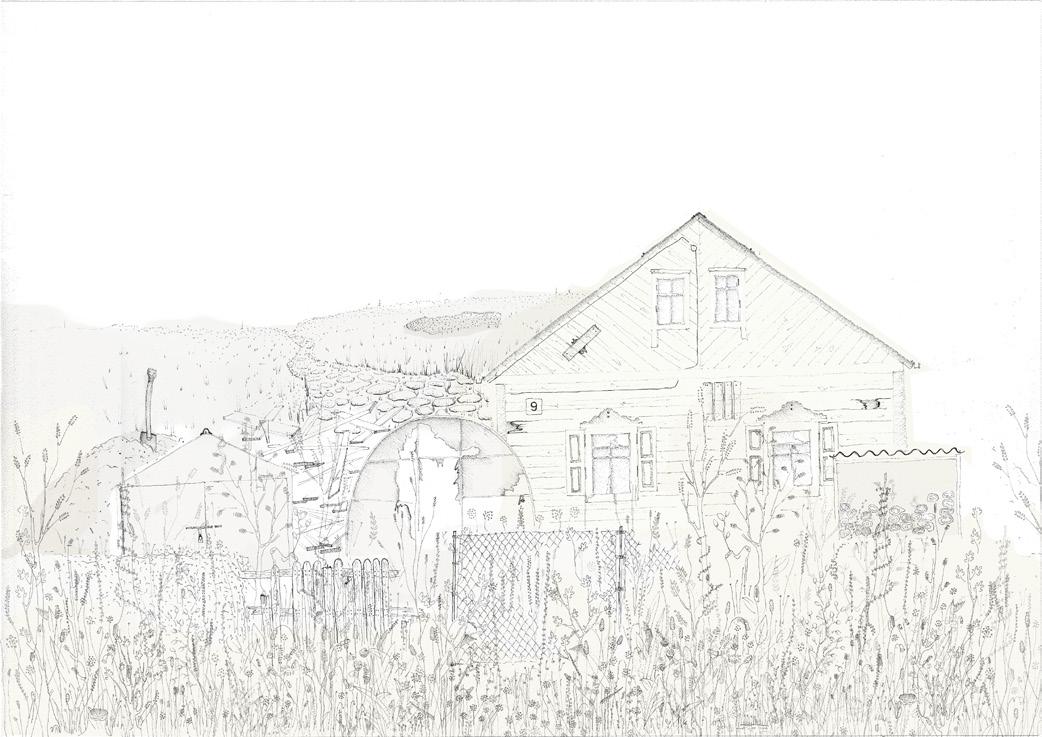

ShanghaiisanexceptionalpartofŠnipiškėswherestilltodayonecanfindavastnumberof laconicwoodenbuildingswithceramichearths.Buildingsdonotfollowanyrationalgridand arerathersmallandlow.Elongatedrectangularplans,gabledroofs,andscatteredexternal structureslikegreenhousesandbarnsdefinethecurrentmateriallandscapeofShanghai.The mostprominentfeaturesarevisible:patching,exposedstructures,repurposedmaterials,and creativemaintenancesolutions.Itisimportanttonotethatthispartofthecityhashistorically beeninhabitedbypeoplenotwell-offtoimprovetheirhomesaccordingtothestandard oftoday.37 Eventhoughthescarcelivingconditionsdidleadtoaratherslowpaceofits development,Shanghaiwithitsruralcharacterhassurvivedtotodayandisaninseparable partofthenaturalecologyofVilnius.Withtime,thewoodenhousesstartedtotakeup thecharacteristicsofurbanarchitecture.Theybecametaller,floorheightandopenings becamelarger.Mostofthehouseshaveturnedintoelongatedoriginalstructurescomprising multipleflats.Eachhouseholdhasbuilttheirporchasanentrance.Slowly,anewtypology hasdeveloped.ApartfromShanghai’smaterialculture,itisimportanttonotethat,unlike anywhereelseinVilnius,moststructureswerecreatedandbuiltbytheresidentsthemselves.38 InhabitantsofShanghaitookuptheresponsibilityofbuilding,rebuilding,renovating,and repairingthedwellingswiththeirownhands,whichisstillthepracticeoftoday.Allinall, Shanghai’smaterialconditionencompassesthesocialrealmofShanghai.Evenwiththescarce livingconditions,peoplemanagedtomaintaintheirhousesontheirownthroughcenturies.

OnecantrulyfeelandseethatShanghaireflectsacontinuousecologyofurbandevelopment withoutanyexternalintrusions,withitssuccessesandfailuresclearlyvisible.

Shanghaiisnotlistedasaheritage,onthecontrary,itisannouncedasmisrepresentative. PublicopinionsaboutShanghai’sfuturehaveformedalocalculturaldebate,makingitacase forfurtherexploration.ThisessayarguesthatShanghaishouldbegivenheritagestatusbecause ittellsthestoryofthepast,remindsofhistoricalpresent,andshouldbecarriedtothefuture. ThereareatleastthreequalitiesthatShanghaipossesses:continuityinbuildingtradition,the evidenceoftheresiliencetotransitions,andcontinuousnaturalecologyofurbandevelopment. VeryimportanttonoteisthatthisessaydoesnotsaythatShanghaiisanexemplarycase ofaculturalobject,butitratherarguesthatexhibitingthe”confusionintimeframes”and failurestogetherwiththesuccessesmakesShanghaiarelevantculturalwitnesstocherish. Therefore,ShanghaiisasiteofculturalheritagewithqualitiesthatShanghai’scommunity andcontemporaryVilniussocietyidentifywithandthereforecannotlivewithout.Arelevant questionnowis:Canourculturalrealitybedefinedbythingsofthepresentthatshowsuccess aswellasfailures?

Thereareculturalpractices”mimicking”today’sinstablesocietalcondition,howeverthere isaneedforthatuncertaintyandheterogeneitytoalsobecomeitssubject.39 KellyBaum questionswhatwouldhappenifheterogeneitybecamethepursuitinsteadofaffliction.She suggeststhinkingofheterogeneityasasignalofpossibilityandnotofdysfunction.40 Thework ofartistThomasHirschhornisdescriptivehere.Especiallythe”Ur-Collage”41 whichtheartist describes:

Iaffirmtheworldinwhichnegativityisshownandinwhichthehardcoreofreality, ofnegativity,isnotbracketedoff.Iwanttoshowthishardcore.Iwanttoturn towardthenegative;Idonotwanttobeacynicoracunningdevil.Idonot wanttolookaway,Idonotwanttoturnaway,andIdonotwanttobeoverly sensitive.Iwanttobeattentive,andIwanttocreateanewworldalongsideandin theexistingworld.IwanttodothiswithUr-Collage.Itshowsthat,itassertsthat, anditdefendsthat.TheUr-Collageistheformofthisnewlycreatedworld.To makeanUr-Collagemeanstobeinagreementwiththeworld.Tobeinagreement doesnotmeantoapprove.Tobeinagreementmeanstolook.Tobeinagreement meanstonotturnaway.Tobeinagreementmeanstoresist,toresistthefacts.42

Hirschhorncreatesartfromthe”badnewdays”insteadofthe”goodoldones”43 .Hetriesto confrontthepresent,torespectit,ortoagreewithit.Theartistassertsthatinordertoattest tothefragilityoftheeveryday,theprecariousneedstobegivenaform,aplaceinourculture. Hirschhornnotesthatitistheonlywaytoexperiencethe”awakenedpresent”.44 JudithButler

inheressayonEmmanuelLevinashasinvestigatedthenotionof“theface”,which,according toLevinasistheimageof“theextremeprecariousnessoftheother.”AccordingtoButler, respondingto”theface”equalsunderstandingtheprecariousnessoflife,yetwearebeing turnedawayfromit.45 Withhisart,ThomasHirschhornrefusestoturnawayandaimsto meetthegazeofthepresent.Thenextchapterswillarguethatheritagecouldbethediscourse thatencouragesunderstandingandagreeingwiththeprecariousconditionoftoday.

Shanghaiisaneighbourhoodwheresuddenpoliticalandeconomictransitionswere experiencedstronglyandresultedinsocioculturalcomplexitiesandaperplexedspatial condition.AlthoughShanghaiisincrisis,isitnot almostalright ?46 Thisessayarguesthat Shanghaiisawitnessofculturalchangeandmighthavecapacityasculturalheritage:it displayscontinuityinbuildingtradition,theevidenceoftheresiliencetothetransitions,and continuousnaturalecologyofurbandevelopment.Yet,Shanghai’spossibilitiesasheritage areslim,astoday’sculturaldebatefocusesonfeaturesthatfitwithinthedesiredfuturewhile refusingtofacetheinstable,uncertainorprecarious.Tobegintacklingthis,thefollowing chapteraimstostudyhowcouldonetalkaboutthefuturethatisnotplannedorprojected, butratherhistorical?

Figure1.1: SandandSaltMixtureinaDepotatGrinda.

Figure1.3: TheCHCMeetingRoom,whichRemindsofaChapel.

Thefuturehasalwaysbeenuncertain.Thelackofknowledgeaboutthefutureishardto accept,thusinventingitstillisthemaincopingmechanism.1 Eventhoughthefearofthe futuredependsonthecontext,insomecasesitprovokesanextremedominanceoverthe environment.2 Landmarks,asobjectsmarkingatransitionalmomentintime,couldbe consideredaspropsforasustainabletransitionintothefuture.3 Therearelandmarksall aroundus,andShanghaicouldbeconsideredoneofthem.Theseplacesarestillaround onlybecausecommunities,preservationists,andstatehaveinvestedenergyinpreservingand maintainingthem.However,someofthoseplacesarelosingtheinterestoftheauthorities,and thusitbecomeshardforthecommunitytomaintainitalone.Duetoarapidcommercialisation, Shanghai,forinstance,desperatelyneedshelpfromthestatetoprovideitwithaheritage statusinordertostopthedemolition.Yet,sincetheconstructedtemporalityhasreplacedthe historicone,4 Shanghaidoesnotseemtoqualifyforheritagestatus.Thusthereisnoneedto inventanotherutopianfuturethatShanghaiwouldfitin,butrathertotrytoseethefuturenot asplannedorprojectedbutratherashistorical.Yet,itisimpossibletohistoricizethefuture withoutidentifyingthepresentashistorical.Heritagediscourseisarguablyaplacewhere suchculturaldiscussioncouldhappen.

Howcanheritagehelponetalkaboutthefuture?AccordingtoFredricJameson,in currenttimesofanultimatehistoricistbreakdown,onecanhardlyimaginethefutureat all.Thefuturewillremaininconceivableaslongasonedoesnotexperiencethepresentas historical.5 Jamesonnotedthathistoricity“is,infact,neitherarepresentationofthepastnor arepresentationofthefuture[…]:itcanfirstandforemostbedefinedasaperceptionofthe

presentashistory.”6 Thissuggeststhatthereisaneedforarelationshipwithapresentthat wouldbysomemeansdefamiliarizeitandprovideonewith“thatdistancefromimmediacy whichisatlengthcharacterizedasahistoricalperspective.”7 ProfessorRodneyHarrisonnoted thatthiscrisisinhistoricityis“relatedtoanincreasinginabilitytoreconcileanunderstanding ofhistoryaspresented(throughhistorybooks,heritagesites,museumsandthemedia)with thelivedexperienceofeverydaylife.”8 FollowingJameson’sthought,JorgeOtero-Pailoshas suggestedonetoreifytheirimmediateexperience,byimaginingitasathingfromeveryday.9 Forexample,thecollectiveexperienceofsharingfoodwithmembersofafamilyeveryFriday evening,foramoment,couldbeconsideredasaweeklyfamilydinner.Thatsaid,lookingat thepresentfromahistoricalperspectivemaysoundeasierthanitis.Jamesonhasexpressedhis concernthatreificationismadealmostimpossibleduetolate-capitalistmodesofproduction. Byconstantlyanticipatingpeople’schoices,marketingandtrend-forecastingcompanieshave “erodedpeople’sabilitytofreelychooseobjectsinwhichtoreifytheirpresent.”10 Therefore, tofacilitatetheculturaldebateonwhatshouldandshouldnotbepartofthefuture,one needstogetagraspofhistoricalpresenteventhoughthesightisblurredbythelate-capitalist reality.Aboveall,itwasneversohardtohistoricisethepresentbut,nonetheless,oneneeds todoittotakeupadiscussionaboutthefuture.

Firstdefinedin1917byaRussianformalistViktorShklovsky,theterm ostranenie (eng: defamiliarisation)hasadopteddiverseappropriationsinbothpracticeandtheoryof20th centuryartandaesthetics.11 Thisessayintendstoseewhatdefamiliarizationwouldmean inthedisciplineofheritage:howheritageallowsonetounderstandthepresentthroughthe lensofthepast.Toillustrate,nomatterhowfaithfullykeptorimpeccablyrestored,heritage existsatpresentandisdefinedbythepastfilteredthroughmodernminds.12 Heritageisabout negotiation-“aboutusingthepast,andcollectiveorindividualmemories,tonegotiatenew waysofbeingandexpressingidentity”atpresent.13 HeritagescholarLaurajaneSmithexplores heritageasasocialandculturalprocessthataimstoengagewithandunderstandthepresent. Infact,heritage,accordingtoSmith,canbeusedbyarangeofsubalterngroupstochallenge thewaytheyareperceivedandredefinetheimposedvaluesandidentities.14 Ascanbeseen fromabove,heritageallowstheprocessofdefamiliarizationtohappen:usingthepastasalens tolookintothepresent,aswellasusingthepresenttochallengewaysoflivinginthefuture. Yet,therearethingstobeawareof.Smithhasnotedthat“althoughoftenself-regulating andself-referential,heritageisalsoinherentlydissonantandcontested.”15 Indeed,heritage tendstopromotea“consensusversionofhistory”byelitesandstateinstitutionstoregulate theculturalandsocialtensionsofthepresent.16 Thissuggeststhathistoricizingthepresent ispossible,thoughoneneedstostayawareofthetop-downcriteriabasedonhistorically immutable“universalvalues”establishedbytheAuthorizedHeritageDiscourse(generatedby

institutionslikeUNESCO),whichdisregardspossibilitiesofchangeovertimeand,therefore, discountspeople’schoice.17 GettingbacktoJameson’sthoughts,thenegotiationbetweenthe pastandthepresentbringsdiscussiononthefutureforward,andheritagediscoursecouldbe aplaceforthisnegotiationtohappen.

BothJamesonandSmithareinfluencedbyMichelFoucault’scritiquesofhowinstitutions “codifyhumanexperienceinordertonormalizeit,andexercisesocialcontrol.”18 Jameson andSmithhavenotedhowinstitutionsdistortone’sabilitytoreifyone’spresentintocultural objects.Bydoingthat,theyalsohavepresupposedsomesortofnaturalandundisturbedway toperformthisprocessofreification.However,bothJamesonandSmithexpresslittleonwhat thislessinstrumentalapproachtograspingourhumanexperiencecouldlooklike.19 Jorge Otero-Pailoshasstartedthedebateconcerningthedegreetowhichheritagepreservationcould befreedfrominstitutionalstateapparatuses.Thisessaytakesasimilarapproach,butwitha deeperfocusonhowcanthisprocessofreificationtakeplace.

Investigatingthematerialworldisawaytobegin.Differentsites,objects,andplaces donotactinthemselvesasheritagebutarenecessaryculturaltoolsthatfacilitateit.20 Since heritagecouldbeseenasaplatformfornegotiationbetweenthepast,presentandfuture, thisessay,therefore,makesanassumptionthatlandmarks(sites,objects,andplaces)are necessarytoolsforthenegotiationtobegin.ContemporaryphilosopherKendallLewisWalton notesthatinordertounderstandhowculturalobjectswork,onemust”lookfirstatdolls, hobbyhorses,toytrucks,andteddybears.”21 Walton’sideaofpropsisamorerecentapproach toDonaldWinnicott’sscholarshipontransitionalobjects.22 Paediatricianandpsychoanalyst DonaldWinnicottintroducedtheterm TransitionalObject in1951.23 Itisatermusedto describeobjectslikesofttoys,blanketsorbitsofclothtowhichchildrentendtodevelop intenseandpersistentattachments.AccordingtoWinnicott,itisatransitionalobjectthat givesspacefortheprocessofbecomingabletoacceptsimilarityanddifferenceandtoturn fromthepurelysubjectivetoobjectivity.24 Ifthetransitionalobjectisablanket,then“washing itshe[amother]introducesabreakincontinuityintheinfant’sexperience,abreakthatmay destroythemeaningandvalueoftheobjecttotheinfant.”25 Therefore,transitionalobjects helpchildrentransitionfromaninternalrealitytoanexternalone.Moreover,thetransitional objectisthefirst‘not-me-possession’,whichimpliesthattheinfantcandistinguishthatthe objectispartoftheobjectiverealityasis‘not-me’.Furthermore,itisimportanttonotethat atransitionalobjectisnotonlyimportantbecauseitisa thing,butratherbecauseofhowits thingness isperceived.26 Winnicottstatesthat“itsthingnessiscrucialonlybecauseithelps thechildtosustainagrowingandevolvinginnerrealityandhelpstodifferentiateitfromthe not-selfworld.”27 Theexperienceofthetransitionalobjectisaprocess“throughwhichwe becomefamiliarwiththesocialstructuringofreality,learningitasweparticipateinit”28 .Up

untiladulthood,transitionalobjectsactasrealmswithinwhichonecanexperiencereification oftheirinnerworldintoouterobjects.Transitionalobjectsinurbancontextbecomepropsfor testingthereality,testingwhichpartsoftheenvironmentoneidentifieswith.Ifeitherofthe subjectswithdrawsfromthisexchange,thenone’sabilitytoreifytheirexperienceintoasense ofrealityisdamaged.Justasparentsnevertrytotakeawaythepieceofblanketfromachild, oneshouldhavearighttobeensuredwiththecontinuousexperienceofrealitythroughasite orabuilding.JorgeOtero-Pailoselaborates:

Identifyingthequalitiesofthosebuildingsthatweassociatewithrealityisvery important.Becausefromthereyoucanbegintounpackthequestionofhowdo we,asasociety,defineourreality,orunderstandourreality?Whichispartof whatculturedoes.Cultureisawayofthedustsettlingonouragreementsof what’srealandwhat’snot.Whatweconsiderimportantandwhatweconsidernot important.29

OnemightthinkofMichelSerres’quasi-objecthere.Bothtransitionalobjectsand quasi-objectsintroducetheideathatobjectsgeneratesocialrelations.Thequasi-objectislike aballinafootballgame.Theballparticipatesinagameandisresponsibleforco-producing thehumaninteraction,whichweknowasfootball.Justasaballgeneratesagame,apiece ofblanket“allowsparentsandchildrentoengageinlearningwithouteithernecessarilybeing fullyawareofthelessonbeingtaught.”Bothtransitionalandquasi-objectsareephemeral andcanneverbeseenasseparatefromourrelationshiptothem.Eventhoughtherelationship betweenpeopleandobjectsisoftenownership-basedandobjectstendtoservepeople,this essaynotesthatoneshouldratherestablishacommunalone.Ownershipdoesnotplaya rolehere,itisonlytherelationshipbetweenpeopleandthingsthatgenerateculturalvalue. Otero-Pailosdescribesit:

Thetransitionalobjectisanobjectthatoperatesattheleveloftherelationship betweenpeopleandthings.It’sacommunalobject,inaway.Whatthechildis askingisforthatobjecttoberecognizedasarealcommunalobject,notonlyas theirobject.Theinsighthereisthattherealityofobjectsissociallyconstructed fromthebeginning,aschildren.Weonlyrecognizethingsasrealbecauseoftheir socialconstruction.Sowecouldtalkabouttransitionalobjectsasplayingacentral roleinthesocialconstructionofreality.30

Objects,therefore,arefundamentalinthisconstantprocessofreconstitution.Objectshelp ustoestablishsomesortofartificialcontinuitywithinthepermanentexperienceofradical discontinuity.31 Itiseasytogetobsessedwiththedecayofobjects,asitcanhelponerecollect

andexperiencecontinuitywiththepast.Inotherwords,themainfunctionofmonumentsisto helprecall.Iftheobjecthascompletelychangedtothepointthatonecannottelliftheobject isthesame,itdoesnothelponetoreconstituteoneself,orone’sculture.32 Therefore,heritage objectisrelatedtotransitionalobjectinawaythatithas”amaterialitythatisbothslowly changingbutstayingthesamesomehow.”33 Yetdoesthecurrentheritagetraditionfacilitate thethoughtthatobjectsprovideacontinuoussenseofrealityandgeneratesocialrelations?

Firstly,thecurrentunderstandingofheritageemergedinWesternEuropeduringthe periodofnineteenth-centurymodernity.34 TheoriginalWesternnotionof heritage tendsto accentuateitsmaterialbasis,anditsvaluesoftentendtobedefinedbyattributessuchasage, monumentality,andaestheticsofaplace.35 Lately,theconcernthatthephysicalityofheritage tendstoovershadowitsimmaterialfeatureshasbeenheardandconsidered.Forexample, TheConventionfortheSafeguardingoftheIntangibleCulturalHeritage(2003)following theProclamationofMasterpiecesoftheOralandIntangibleHeritageofHumanity(1997) togetherwiththeUNESCOUniversalDeclarationonCulturalDiversityin2001,havestressed theimportanceofnotionssuchasintangibleandculturalheritage.Eventhoughthereexistsa commonbeliefthatsuchnotionsarerapidlyhavinganimpactonnationalandlocalpolicies,36 thisessaynotesthatseeingintangibleandtangibleheritageseparatelyismisleading.Although theAuthorisedHeritageDiscoursestartsacknowledgingtheintangibilityofheritage,itdoes notmeanthatitiseasywithit.37 Forexample,inLithuania,theterm intangibleheritage tend tobeincludedforthesolepurposeof”tickingthebox”andisnottakenintopractice.38 It isnotsurprisingthattheso-calledintangibleheritagehasnotreallybeenimplementedin localpolicies,because,asalocalheritagescholarSalvijusKulevičiushasnoted,itisnotclear whatthesubjectofthatheritageis.Thisonlyprovesthatintangibleandtangiblearewords todescribequalities,buttheyshouldnotbeusedtodifferentiatebetweentypesofheritage. KulevičiusdescribesthatthecurrentstructuringoftheculturalheritagesysteminLithuaniais stillverymuchfragmented:39

Lithuania’sheritagepolicyischoppedinpieces.ThisisnotaproblemofLithuania perse;itderivesfromaclassicalmodelfunctioningfromthe19thcentury.What ismaterialweputtoonesideandwhatisimmaterial-totheopposite.Thenwe endupwithaconflict:thepurposeofallintangibleheritageiscontinuity,whilethe materialheritageintheEuropeanschoolisdefinite.Intangibleheritageistradition –it’salive.Materialheritageisthecultureofthedead,wherenochangesare allowed.Shanghai’scaseisaboutthecontinuityoftraditionthrougharchitecture. InLithuania,wecan’tmakethisconnection.

SalvijusKulevičiusexpresseshisconcernthattheseparationbetweenmaterialand

immaterialisprominentinLithuania.Inthetheoreticalfield,theheritagediscourseis concernedwithamoreintegratedstructure,howeverinpracticetheytendtostayseparate. Indeed,asprofessorRodneyHarrisonpointsout,“heritageisnotathingorahistoricalor politicalmovement”onitsown,instead,itreferstocertainrelationshipswiththepast.40 Especiallywiththeoftenheardnotionofintangibleheritage,theserelationshipswiththepast mightsometimeslooklike“intangiblepracticesthatappeartobeseparatefrommaterial things.”41 Yet,evensuchpracticesarealwaysembeddedinone’sphysicalrelationshipto anobject,andsotoseeintangibleheritageseparatefromtangibleheritageisinaccurate.42 LaurajaneSmithstartsherbook”UsesofHeritage”bystatingthatallheritageisintangible. Shenotesthatsheisnotseparatingimmaterialfrommaterialordisregardingthephysicality ofheritage,butonlydenaturalizingitastheself-evident.43 Thereisnoharminspeakingof itseithertangibleorintangiblequalities,yetitisessentialtonotseparatethemasdifferent kindsofheritage.Smithnotesthat”heritagewasn’tonlyaboutthepast–thoughitwasthat too–italsowasn’tjustaboutmaterialthings–thoughitwasthataswell–heritagewasa processofengagement,anactofcommunication,andanactofmakingmeaninginandfor thepresent.”44 Thewell-knownexampleofIsecomestomind.Iseiswherethedemolition andreconstructionoftangibleobjectsestablishestheintangiblewithinthem.Inotherwords, itisthematerialimpermanencethatestablishespermanentprinciples:thegoalmightappear astransient,butitisinfactabouttheeternalvalues.45 So,whatmakesStonehengeheritageis indeednotacollectionofrocksbutratherculturalactivitiesthatareundertakenat,around, andwiththem.46 Heritagethusneedstoacceptthatmaterialandimmaterialareonething, becausethenobjectswillbeabletohelpusunderstandtherelationshipsbetweenus,the everydayobjects,andtheworld.Thisessayaimstocontributetothecurrentparadigmatic shiftfromartefact-basedheritagethinkingtoanactor-basedapproach.47

Harrisonnotesthatbureaucratisationandprofessionalisationofheritagehastakenit”out ofthehandsofamateursandenthusiasticmembersofthepublic,andputitscontrolintothe handsof‘experts’”whichhadamajoreffectofheritagebecoming”lessaboutwhatpeopledid aspartoftheireverydaylives.”48 Asheritagebecameafieldforexperts,itmadeaturnfrom thelocaltoastate-controlledprofessionalizedpractice,whichbroughtheritagefurtherfrom theeveryday.49 YurikoSaitohasnoted:50

Ifwearesearchingforthecultureoftoday,weneedtolookintowhatpeopleare doingtoday,intotheeverydaypractice.

Thecurrentcriteriasetforheritageislookingfor outstanding andatthesametime universal values51 ,inotherwords,forsomethinguniversallyacceptedasextraordinary.Thatimpliesthat theextraordinaryisbeingconsideredbetterthantheordinary.Nevertheless,thisessayisan

investigationoftheconditionsunderwhichdifferentculturalparadigmsexerttheirdominating influence,thereforetypicalsituationsofeverydayexistencearethefocus.52 Thisessaytriesto bringheritageclosertothequotidian,sincehereheritageisseenasaculturalprocesswhere “humanandnon-humanagentsareseentoworktogethertorecreatethepastinthepresent througheverydaynetworksofassociation.”53 Yet,evenbelievingthateverydayhasthepower togenerateculture,54 onemaystillfinditchallengingtoquestiontheeveryday.GeorgePerec famouslywrites:55

Toquestionthehabitual.Butthat’sjustit,we’rehabituatedtoit.Wedon’tquestion it,itdoesn’tquestionus,itdoesn’tseemtoposeaproblem,weliveitwithout thinking,asifitcarriedwithinitneitherquestionsnoranswers,asifitweren’tthe bearerofanyinformation.Thisisnolongerevenconditioning,it’sanesthesia.We sleepthroughourlivesinadreamlesssleep.Butwhereisourlife?Whereisour body?Whereisourspace?

Howarewetospeakofthese‘commonthings’,howtotrackthemdownrather, flushthemout,wrestthemfromthedrossinwhichtheyremainmired,howtogive themameaning,atongue,toletthem,finally,speakofwhatis,ofwhatweare.

Itiscommontoownabookthathasaword everyday initstitle,eventhoughverylittleof thesebooksmentionthesamewordintheirindex.56 RitaFelskinotesthattheeverydayis like“theblurredspeckattheedgeofone’svisionthatdisappearswhenlookedatdirectly”: it“ceasestobeeverydaywhensubjecttocriticalscrutiny.”57 Therearescholarshipsonthe everydaythatdoanalyseitthoroughly,buteitherseeitasanon-intellectualrelationshiptothe world,ortrytoassertasupremesignificancetoit.58 Thisessay,however,arguesthatwhen studied,theeverydayshallkeepitscharacterofthemundaneduringthewholeinvestigation. Inotherwords,thepurposeisnottoredefinethevalueofeveryday,butseethevalueofthe existing.It’sundoubtedlyachallenge.ArchitecturalhistorianDellUptonproposestothinkof everydayasa“bodilymemoryinstilledbyrepeatedactioninorganizedtimeandspace.”59 Since itcomprisesrepeatedand“seeminglyunimportantactivities”itisalmosteasiertoidentifyit bywhatitisnot,thanbywhatitis.60 Duetoitsintangibility,theeverydayissuitedasabranch ofphilosophy,butisclearlyatoddswiththingsandmaterialculture.61 Therefore,maybethe quasi-objectsgeneratingtheintangiblemighthelpsustainthehappenings,ritualsortraditions thatdefinethecharacteroftheplace.Itisimportanttokeepinmindthat theeveryday is notequalto theeverydayenvironment (whicharchitectstendtomixup)asthewaywelive initisanequallyrelevantaspect.62 FrançoisPenznotedthattheeverydayactsasan“agent ofchange.”63 Indeed,thecreativeaspectofeverydayexistsbecauseitistheeveryday,that

generatesourpresentculture.64 Consequently,inthisessaytheeverydayisseenasatoolto graspthereality,aswellastogetinsightonthefuture:

Therealcanonlybegraspedandappreciatedviapotentiality,andwhathasbeen achievedviawhathasnotbeenachieved.Butitisalsoaquestionofdeterminingthe possibleandthepotentialandofknowingwhichyardsticktouse.Vagueimages ofthefutureandman’sprospectsareinadequate.Theseimagesallowfortoo manymore-or-lesstechnocraticorhumanistinterpretations.Ifwearetoknow andtojudge,wemuststartwithaprecisecriterionandacentreofreference:the everyday.65

Wemustidentifythewayweliveandwhatculturethatwayoflivinggenerates.Asking questions,suchas“Whyisthishere?Whoputithere?Who’sbenefitingfromthisthingbeing here?Whogetstodecideaboutthisthingbeinghere?”isagoodwaytostart.66 Harrison mentionsaterm everydayheritagepractice anddefinesitasacontinuousheritagepractice, emphasisingthelinkbetweenthepastandtherealquotidianpresent.67 Therefore,ifweare searchingforthecultureoftoday,weneedtolookintowhatpeoplearedoingtoday,into theeverydaypractice.[2.1, 2.2, 2.3]Thatmeansusingheritagediscoursetolookforeveryday transitionalobjectswhichhelpusidentifyourselveswiththepresentthroughthepast,andgive insightintothefuture.

Figure2.1: AHistoricalMonumenttogetherwithElementsfromtheEverydayPractice

Figure2.2: HistoricalMonumentsWithanElementFromtheEverydayPracticeinBetweenThem.

Figure2.3: AHistoricalMonumentSupportedbyanImprovisationalHand-MadeFixture

Preservationistsproduceobjectsthatstabilizeourpresentandinthatwayprovideexperiential continuityforourculture.1 Itisanillusionofcontinuity.Theprocessofconservationprovides onewithasenseofcontinuitywiththepast,yetitgentlyfrustratesit.Thecriticalpracticeof conservationisamodelofculturalchange,butnottherevolutionaryonethatencouragesto startover.Instead,criticalconservationsays:wearegoingtochange,itisgoingtobereally difficult,itwillcreatealotofanxiety,butlet’stalkaboutit.2 Theconservationprocessis abletoextendanobject’slifespantowhatFedericaGofficalls“quasi-eternity”.3 Yet,itisnot enoughtojustchooseanobjectasheritage:theobjectsthatstayaroundaretheonesconstantly takencareof,maintained,andregenerated.TheredevelopmentplanofShanghaihascaused asocioculturaldebate.Isthatnotbecausesomeofthoseprotestingtheredevelopmentthink thatShanghaibelongstoVilniusculturalpresent?Itisthepreservationist’stasktodecideif Shanghaiisatransitionalobjectandhelpspeopletransitionfromoneculturalstagetoanother. Thischapterinvestigatesthequestionofwhoshouldbetakingtheroleofapreservationist. Heritageisnotfoundasheritage.Heritageisoftencreatedbytheactofconservation: observation,preservation,mapping,andmanagementoftime.Criticalconservationisthusa creativeactofnegotiationbetweenthepast,presentandfuture.SalvadorMuñozViñasnotes thatclassicalconservationtheories(fromRuskintoBrandi)arecharacterizedbytheirclose adherencetoTruth.4 Heelaboratesthatthesetheoriesarecurrentlydominant,butcriticism andnewalternativesaregainingmomentum.5 MuñozViñasaddsthat“theoldbeliefthat damagecouldbeclearlyandobjectivelydefinedispresentlyseenasanillusion,andmany conflictsonconservationprocesseslieindeepdisagreementsonwhetheragiven,orearlier,

alterationshouldbeconsidereddamage.”6 ProfessorDanielBluestoneraisesthefollowing questionregardingthecurrentunderstandingofconservation:“Whyshouldn’tweaccept changewithitsdestructiveforcesandsimplygreetnewformswithenthusiasm,ratherthan engagingintheconservativepracticeofholdingontoolderandmoretraditionalformsof materialculture?”7 Lowenthalin PossessedbythePast hasdistinguishedbetweenhistory andheritage.Lowenthalsuggestedthatfalsehoodisnecessaryforsomethingtobeestablished asheritage.8 Cosgrovehasarguedthatinconservation,realityisnotrevealedbutcreated.9 Therefore,itbecomesevidentthatconservators,experimentalpreservationists,andarchitects haveagencyonlyiftheconservationofheritageispractisedinafreerway.Lowenthal,McLean, andaboveall,Cosgrove,havedemandedthe”possibilityofgreatercreativefreedomonthepart oftheconservator.”10 Theyhaveaskedforconservationtobe”morecreative,lessdeferential tocanonicalideology,moreopentotheradical,theiconoclastic,andtheinvented.”11 Federica Goffisaysthatconservationisaformofinventionandreimagination.Shequestions,”Isit possibletoconceiveofconservationasaformofinventionallowingforthemakingofmemory throughtheunfoldingoftime,revealingthepossibilityforanimaginationofconservation?”12 Inshort,thoseconservingheritagearetryingtoprovideanillusionofcontinuity,whichisa creativeprocessandrequiresfreedomfromthosecuratingthediscipline.13

Thisessaywillfirstintroducetwowell-knownexamplesofwhatcouldbeconsidered ascriticalconservation.Eventhougharchitectsareoftencritiquedtonot”viewhistoric buildingsaslikelycanvasesfortheircreation,”14 thisessaytendstobelievethatthereare greatprecedentsnevertheless.Let’stakeanexampleofaGermanarchitect,HansDollgast, andhisprojectforAltePinakothek(1957).ThereconstructionofAltePinakothek(1957) identifieshowthearchitect,eventhoughbeingattunedtothequalitiesoftheruin,didnot intendtopreservethebuildingasone.Dolgastworked”throughandwiththetemporary.”15 Dollgastmanagedtoturnthe”ephemeralandcontingentintoarchitecturalopportunities.”16 “Thecontrastofthebrickworkisonlystarkwhenyoulookclosely.[3.1]Thenyounotice Dollgast’s”judgmentbyinsertingaconcretelintelhereandthere.”17 Dollgastencouraged peopletoacceptthatthemuseum,too,hasitshistory.Dollgastleftthewardamagevisible, whichwasconsideredadisgracebythepublic,protested,andremovedafterward.Maximilian SternbergdescribesHansDollgast’sworkas”attentivetotheaccidentalandcontingentas muchastotheunderlyingpossibilitiesofcontinuity.”18 AltePinakothekisanexampleof conservationpracticethatprovidesthepublicwithatemporalexperienceofthepresentthat hastheelementofhistoricitywithinit.Completedinthesamedecade,PalazzoAbatellisby CarloScarpaalsocallsforattentionhere.JustlikeHansDollgast,CarloScarpawasnot interestedinruinsorfragmentssolely,butwasfocusedin“thesumofartefactsproduced withinaculture.”19 BeforeScarpa’sintervention,PalazzoAbatelliswasalreadyanarchitecture

oftransition.MarcoFrascariconsidersScarpa’scontributiontoPalazzoAbatellisasa“visual transcriptionoftheinvisibleprocessesofhistoryandculture.”20 PalazzoAbatellisisatime machineandatheatreofmemory.21 PalazzoAbatellisisundoubtedlythearchitectureof surrealism:throughadoringthenatureofrealityandthroughthepowerfultooloffantasy, therealbecomessurreal.22 ItisessentialtonotethatScarpa’sefforttoescapethemundane realityforthesurrealwasnotmeanttocreatean”unreal”butrathertoexpose“theheart ofreal.”23 Scarpa’sdesignatpresentisanegotiatorbetweenthepastandthefuture.24 Alte PinakothekandPalazzoAbatellisaredifferentintheirarchitecturalapproaches,yettheyboth seemtospeakoftheircomplexhistories,arefreedfromtraditionaljudgmentsandleftopen fornewinterpretations.25 Inbothofthosecases,pastandfutureliveclosetogether,meetingat diversematerialandspatialsolutions.Thesearejusttwoexamplesofarchitectureascritical conservation,providingthepublicwithanillusionofcontinuitywhilefrustratingitslightly withthepast.

Whatexperimentalpreservationhasproposedisthatwe,asarchitects,asartists, aspeopleworkinginthevisualfield,canhelptoattunepeopletocertainrealities. Toreallyshapeourrelationshiptowhatweconsidertobereal.I’mnotgoingto saydirectit,butinfluenceit,inapositivedirection.Wehaveanenormousamount ofagencybutwehaven’tuseditbecausepreservationistshavebasicallywaitedfor thejobtoarrive.[...]Experimentalpreservationismoreguerrilla-likeinthesense thatpeoplearenotwaitingforthecommission,theyareactingonhistoricobjects directly,withorwithoutpermission,asawaytobegintohaveagency.26

JustlikeJorgeOtero-Pailos’quoteabove,thisessayacknowledgesthatarchitectsandother agentsfromavisualfieldhavethepowertoshapepeople’sculturalrealities,yetitdoesnot arguethatthecriticalconservationpracticesshallonlybeperformedbythem.Eventhough theexamplesdiscussedaboveincludedtwobuildings,oneshallnotprioritizetheirphysicality overtheirconsequences.Conservationshallalwaysbecarriedoutforthesubjectsinsteadof theobjects.27

MuñozViñashasnotedthatforheritageconservationtobecomeacreative,criticaland progressiveprocessitsagentshavetobeawareofnotimposingthedecisionsontheaffected subjects.Multipleauthorshavealreadynotedthisbycallingconservation”negotiative”,a ”pact”,a”discussion”,a”consenso”,an”equilibrium”,oraformof”trading.”28 Itis“astep towardcooperationindecision-makinginafieldthathastraditionallybeenelite-oriented.”29 Inshort,heritageshouldshiftfromtheexperts’fieldtowardsa“broaderpublicdomain.”30 Itisclearnowthatthediscourseisnotonlylegitimizingwhatheritageis,butalsodeciding whocanspeakofit.Thetop-downheritagediscoursehasconsequences,andoneofthe

mostprominentonescurrentlyisthatheritageisslowlybecominganeliteconcerndiscussing socialissuesrelevanttoonlytheeconomicallyandsociallycomfortable.31 Apowerful critiqueregardingstateinstitutionschoosingandgatheringculturalheritageisexpressed byBosnianartistAzraAksamija.InthecontextofBosnia-Herzegovina,Aksamijacreated aparticipatoryprojectcalled”FutureHeritageCollection-Office”32 whichinvitedcitizens andvisitorsofSarajevotobringartefactsthattheyconsidertobeimportantgeneratorsof Bosnia-Herzegovina’sculturalheritage.Inthisway,theprojecthasexperimentedwiththe publictakingtheroleofconservationistsandchoosingheritagethatwouldneverbechosen bytheinstitutions.Theroleofacriticalconservationist,is,therefore,tochooseandtestthe objectsconsideredbyofficialinstitutions unworthy,becauseofacoupleofreasons.Primarily, thoseobjectstendto“embodythematerial,socialandenvironmentalcostsofdevelopment whichgovernmentsandcorporationsseldomaccountfor.”33 Anotherreasonisthatcritical conservationisoftenlessconcernedwithobjectsthemselvesbutratherhowtheactofkeeping theseobjectswouldenrichourlives.Andfinally,itisoftenthechoicetoworkwiththose unworthy artefactsthatquestionstheexistingheritagecriteriathatwerecreatedinthelate 19thcentury,atatimewhenmostofwhatdefinesourcurrentenvironmentdidnotexist.34 Bychoosingtheobjectsincrisis,theconservationistexposesthemselvesandthepublictothe consequencesoftherapideconomicandpoliticaltransformation,allowingthediscussionon thehistoricalpresentandfuturetohappen.Mostimportantly,thecommunitiesexperiencing thoseconsequencesthestrongestshouldbeallowedtotaketheroleofaconservationistand decideiftheircurrentculturalrealityisvaluable.

Furthermore,criticalconservationisnotonlyapublicbutalsoacreativeact.Inhis book ExperimentalPreservation,JorgeOtero-Pailoswrites:“Iliketheideaofare-enactment. Comingbackfromthefutureisasortofsciencefiction.Insomeway,theideaofpreservation issciencefiction.Whenwesaidthatitwasanartandascience,wecouldalsosaythatit isafictionofscience.”35 Otero-Pailosarguesthatwhencreativityisthetopicofdiscussion, everyonegetsseriousandavoidsmentioningit.36 Butifpreservationistsaresubjectivemakers ofcultureandpreservationisanewculturalproduction,37 creativityissomethingthatneedsto bediscussed.Let’sthinkofthearchitecturalexamplesprovidedabove.Theyarebothcreative solutionstoconservingaplace.Theybothhavesuccessfullycreatedbridgesbetweenthepast, presentandfuture.Thecreativeaspectallowsonetoexperiencethethresholdoftherealand surreal,ofthepresentandthefuture,toemploythetransitionalobjectstohelpdistinguish theimaginedfuturefromtherealpresent.Allinall,ifcriticalconservationbecomesapublic discourseandcreativeaspectwithinitgetsestablished,theactofconservationandtheactof maintenancebecomeratheralike.

MierleLadermanUkelesinhermanifesto(1969)distinguishedtwobasicsystems:

developmentandmaintenance.Developmentisaboutprogress,newness,andexcitement broughtby”theadvance”.38 Yet,havingthedevelopmentimplieshavingapartofsociety maintainingit.Theactofmaintenanceisto“keepthedustoffthepureindividualcreation; preservethenew;sustainthechange;protectprogress;defendandprolongtheadvance;renew theexcitement;repeattheflight.”39 HannahArendt’sthoughtsondistinguishinglabourfrom work,raisesanideathatmaybemaintenanceisanewtypeofwork,“alastingthing.”40 Maintenanceissomethingthatisnotreproductiveonitsownbutratherallowsthosedoingit tobeawareoftime,change,andquestionsthatthethoughtoftemporalityraises.Itallows forthejoiningofthespatialandtemporalexistences.Therefore,maintenancemakesthe reificationprocessviable:everytimeonerepairssomething,onefindsoneselfinamoment ofspatialandtemporalawareness.Itisaprocesswherethepastmaterialstatedefinesthe presentone,whichisthestartingpointoftheoneinthefuture.ChristopherAlexanderputsit concisely:41

Inthecommonplaceuseofthewordrepair,weassumethatwhenwerepair something,weareessentiallytryingtogetitbacktoitsoriginalstate.Thiskindof repairispatching,conservative,static.Butinthisnewuseofthewordrepair,we assume,instead,thateveryentityischangingconstantly:andthatateverymoment weusethedefectsofthepresentstateasthestartingpointforthedefinitionofthe newstate.

Besidescontributingtothespatialandtemporalawareness,maintenanceisawaytodevelop socialconscience.AgnesDenes’cultivationandharvestofcropsinDowntownManhattan42 createdamonumentalimageof“thecomplexrelationshipbetweenenvironmentalresources, urbanism,architecturalandspatialpractices.”43 TheWheatfieldproducescropsthatwere grownasaresultofcare.InthecaseofAgnesDenes,theportrayedcareconcernslabour, irrigation,fertilizers,Denes,andherteam.44 Denesintendedtocallattentiontomisplaced prioritiesandinsteadofdesigninganotherpublicsculpture,shecreatedatemporalecology, whichwassustainedbypeople,nature,andtechnology,startedwiththegrowingand endedwiththeharvest.The”Wheatfield”provides“evidenceofnature,evidenceofhuman relationshipsbeyondthetechnical”45 and,inthisway,provesmaintenance’simportancein developingoursocialconscience.

Apartfromitsreifyingpower,practisingmaintenancecouldalsoofferanapproachtoa differentlifestyle:maintenanceoffers”awayofholdingontothatmostpleasurablepartofthe cycleofconsumeristdesire.”46 Ifthelusttoconsumeisimpossibletosatisfy,sotryingtodoso mightnotbethegreatestidea.47 Let’stakeShakers’48 attitudehereasanexample.Although Shakersbelievedthattheendoftheworldwasnear,theydidnotmaketemporaryfurniture,

instead,theycaredforfurnituretooutlastthem.“Therearen’tmanyshakersleft”,EulaBiss writes.49 Nowadays,itiscommontopracticeownershipmorethantheactofcare.However, whatifwetakeShanghaiasanexample,wherebuyingahouseisnotanoptionduetothe lackoffinanceandanoverlymessyprivatizationprocess.Itisclearthatthereisaneedfor moresustainablewayoflivingwheremaintenancebecomethenewownership.Thetradition ofmaintenanceandrepairinShanghaiwasdevelopedduetoanextremesenseofuncertainty. Nooneknowshowmuchofitwouldbeleftiftheplacereceivedastatusthatitcanstaythere forever,however,examplesinthecountrysideshowthatamaintenancelifestyleneedsmany yearstodevelopandcanexistwithnoexternalthreats.Couldthisperceivedacceleratedpace oftimethatkeepsoverthrowingthetraditionandconsciousness50 ofthepresentslowdownand meettheoneoflongstandingtraditionsofmaintenanceandcare?Thequestioncallsforthe attentionofthelocalstate-ruledinstitutionsandinternationalonesresponsibleforforming currentheritagepolicies.Thereisaneedforspaceforacknowledgingthepreservationists outsidetheofficewalls:thecommunitiestakingcareoftheirenvironmentfordecades,seeing valueinit,anddedicatingtheireverydaytocare.Ultimately,maintenanceisapublicand socialactthatisnotboundtoownershipandwhich,initself,isaneverydayinterrogationof therelationshipbetweenpeopleandthings.Assumingthatpreservationcouldbeperformedby theauthoritiesaswellasthepublic,thefollowingchapterwilldiscusspossiblemethodswhich couldbeemployedbythepublictotestandexaminetherealnessandcapacityofaplaceasa potentialmemoryofthefuture.

Figure3.1: PencilSketchofaFragmentoftheSouthernSideofAltePinakothek.Theoriginal-inblue; thereconstructed-ingreen).

Figure3.2: PalazzoAbatellis,IndoorExhibitionSpace.

Thisessayproposestwotypesofapproachesforreificationwiththeeveryday:(1)experiencing theordinaryasordinaryand(2)experiencingtheordinaryasout-of-the-ordinary.Thechapter issplitintotwopartsaccordingly,andtheywillcoverseveralmethodseach.Foremost,the essaydiscussesintensiveobservationcanbeusefulintryingtoconsidereverydaywithoutlosing theordinarinessofit.Thesecondpartwillfollow.Defamiliarizationisawaytobeawareof adirectpresence.

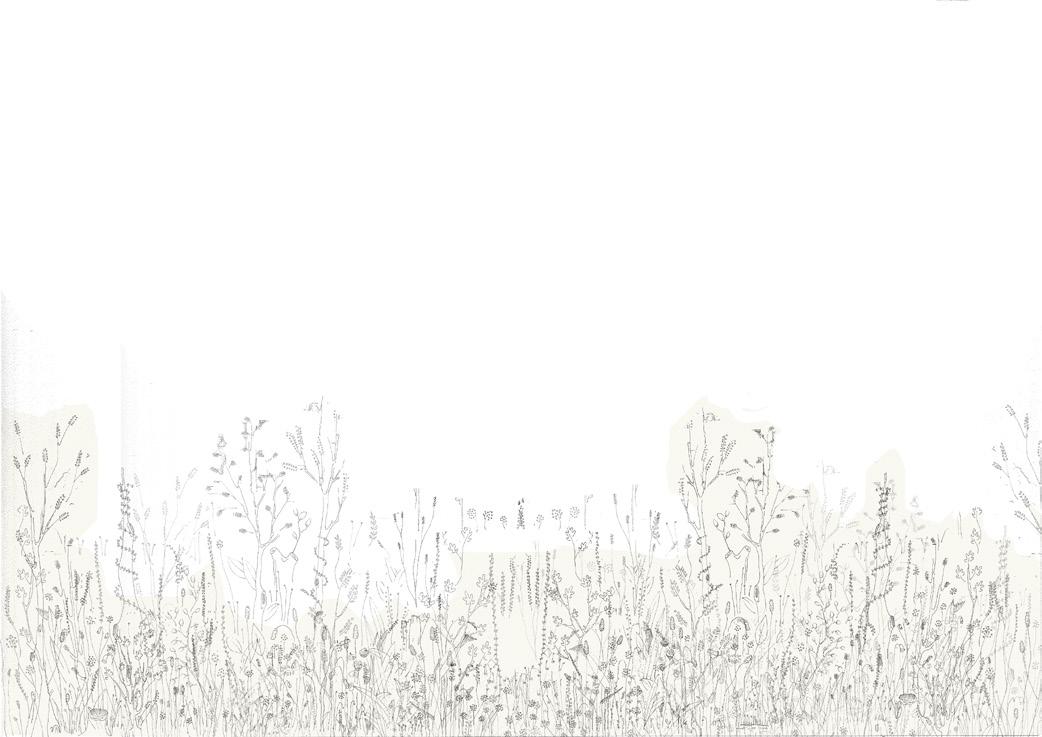

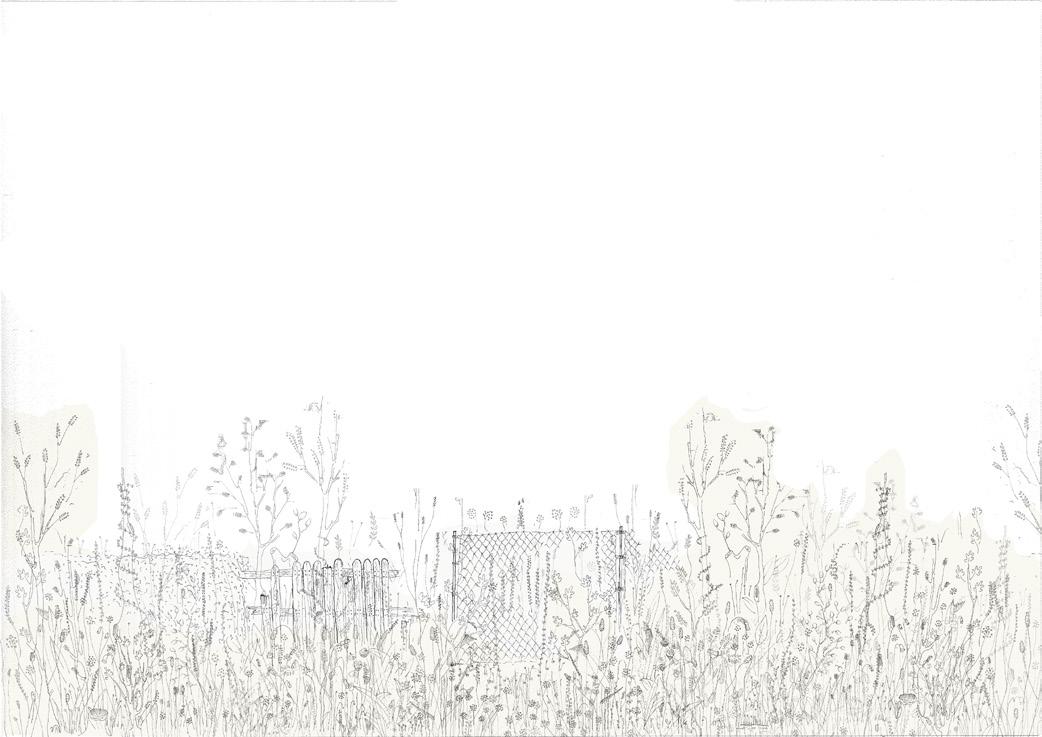

Experiencingtheordinaryasordinarycanbedonethroughanin-depthdescription.The firstmethodexploredistheoneofarchitecturaldrawing.Bythewordarchitectural,thisessay doesnotintendthatthedrawingneedstobemadebyanarchitect,butratherforittohave aspecificpurpose.Thepurposeofsuchdrawingisasstatedconciselyintheoriginalcallfor papersfortheModelsandDrawingsconference.Thearchitecturaldrawing“teachesthegaze toproceedbeyondthevisibleimageintoaninfinitywherebysomethingnewoftheinvisible isencountered.Thusthetrue’drawing-gaze’neverrestsorsettlesonthedrawingitself,but insteadreboundsuponthevisibleintoagazeoftheinfinite.”Nowadays,duetotheobsession withproductivityandrationalization,thereislessspace“fortheinvisibletoemergefromthe processoftranslation.”1 However,beingconsciousofthathelpstoallowtheinterpretation processtohappen.Theinterpretationprocesshereisnecessaryforthemomentsofawareness betweencapturingtherealandcreating.Becausethatmomentallowsustounderstandwhat isitactuallythatisknownaboutthecurrentreality,whatwasmemorable.AsWaltonputs it,byperformingthismake-believegame,we“findourselveswithawayofdistinguishing fictionfromnonfiction.”2 Today’spracticestilltendstoseparatethe“asbuilts”fromthedesign

Figure4.1: Penonpaper.NeighbourhoodPlan.

drawings,3 whichformsthefirstchallengeofthischapter:architecturaldrawingsshallaimto rejointhesetwotemporalconditions:retrospective(orthenon-fictional)andperspective(as thefictional)character.Thisessayarguesthatthepointwherethesetwomeet,realization happens.Insuchawaythedrawingcanbeatoolwithintheritualfuturearchival,whatisreal andwhatisnot,whatwillstayforthefuture.Thegameofmake-believehelpsonetoposition oneselfintherealworldandunderstandone’srelationshipswithpeopleandthingsbetter.4 ThepreservationistinthischapteristestingtherealnessofthingsandtryingtoseeShanghai’s potentialasthe”memoryofthefuture.”5 Thisarticleconcernsbothpen-on-paperdrawing techniques,photographsofhandmademiniaturemodels,andwrittendescriptions.

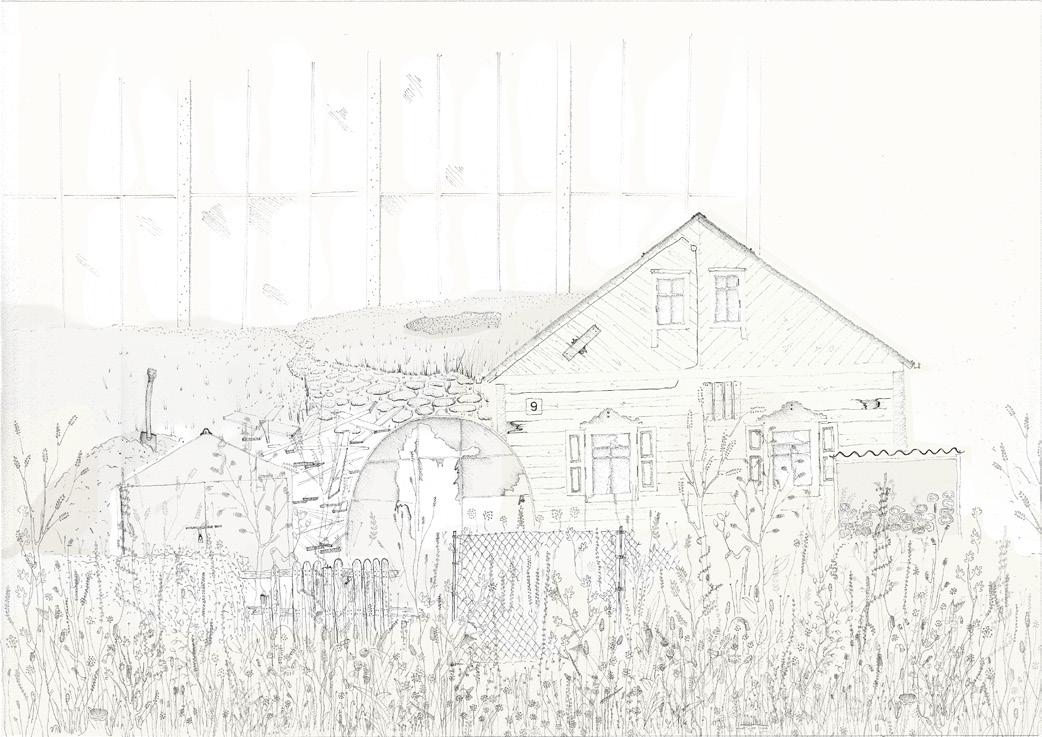

Theprovidedpen-on-paperdrawingrepresentsthecurrentplanofShanghai.Itisdrawn onanA0sizepapersheetwitha0.05mmthickpen:themediumallowsspacefordetail.Itis notarealisticdepictionbuiltonlayers.Whilepreparingforthedrawing,itbecameclearthat inShanghai,layersarehardtodistinguishfromoneanother.One,insteadoftryingtodetangle thechaoticcharacter,immersesoneselfinthestoryofShanghaiandjustfollowsitnaturally

Figure4.2: Penonpaper.NeighbourhoodPlanZoomed-In.

unfolding.Thisishowthedrawingwasmade.Itstartedfromabottomcornerontheleftside andevolvedaroundit,beingguidednotbyarationalebutratherbythememoriesofobjects, howtheycorrespondtoeachotherandtheintuitionoftheonedrawingit.Thehandmovedup thepage,thenwentsidewaystotheleft,thenupwardsagain.Themovementsomewhatrecalls theonedescribedbyHusserlas“zigzagfashion.”6 Insteadofusingpreconceptionsasguides,an artistusedmaterialconcreteconditionsasclueswhichledtomoregeneralinsights.7 Therefore, lookingatthedrawingfromanobserver’sperspectivethelayersmaymayberecognisablebut notseparable:thedrawingratherappearsasonecontinuousentity.Thereadingprocess becomesmorechallenging:withnoindicationofstartandfinish,areaderneedstogothrough thesamejourneyofperception.Eventhoughthedrawingwascreatedfromablankpage andwasnottracedoveranything,differentmedia,suchasvideos,photos,satelliteviews,and memorywereusedtoconstructit.Itisclosetoimpossibletorecreateanexactimageofthose thatarebeinglookedat.Therefore,thedrawingprocessincludedtwotypesofinterpretations: 1.Whentheartistrememberstheplacebeingdifferentfromitappearsinthereferencemedia; 2.Whenthereferencemediafailstoprovidesufficientinformationonasite.Therefore,even thoughthedrawingencompassesahighlevelofdetail,onehastobeawareofthefactthat detailsalsocomefromimagination.Theprocessofinterpretationwasasimportantastheone ofdepiction.Theartistwasresponsiblefordecidingwhentoputthehatofthecreator,when totakeitdown,andwhentowearitbackagain.Thisquestioningofwhatisrealandwhat isnotwasaconstantprocessofmake-believeandhasbeenfrustratingthepastagainstthe presentandthepresentagainstthefuture.Thesemomentswereoneswhentheartist,andthe casethepreservationist,becameawareofobjectsandtheirmeaningatpresent,asremnants fromthepastandpotentialmembersofthefuturefabric.Importantly,somepartsofthe drawingareleftunfinishedornotasdetailedasothersintentionally.Evenifthedrawingis “invisibleinitswholeness”,itengagestheimaginationofthereaderinrevealingthefullness ofit“bywayoftheunfoldingofacontinuumofitsmanifoldvisibleaspects.”8 Thosespots areplacesleftforthereadertoperformtheirreification.Therefore,bothfortheartistand theaudience,thedrawingactslikea“thinkingmachine”whichcreatesspacefordialogues “betweensubjectsandobjects,heresandtheres,nowsandthens.”9 Drawing,almostlikea veil,unveilsa“supratemporalpresence”.Itactsasa“dialogiccounterviewpointrelationship betweenmemoryandimagination.”10

Tocontinuestressingtherelevanceofsucharelationshipbetweenmemoryandimagination, anothertechniqueofdrawingisintroduced:photographsofminiaturemodels.Photographs ofminiaturemodelsdifferfromthepreviouslydiscussedtechniqueinitsmaking.The pen-on-paperdrawingalloweddiscoveryhappenthroughtheprocess,throughwandering throughthesystemoftheneighbourhood,asasystemofdailyinfrastructures.Thesecondone

ismuchmorefocusedononeimage,andlookingintodailyremnants,andhavingadeeper lookintodailyobjectsandwhattheymean.

Itrytoreconstructanideaofrealitywemightallshare–‘illusion’alwaysimplies there’satrickoratrap,amomentwhereyousay‘oh,Iwasfooled’.I’mnotafter thatatall,I’mtryingtopictureanideaofrealitywhichischangingallthetime. It’ssomethingthat’sinterestingforanartistbecauseyouspendsometimemaking pictures,andyourealisethatthenotionofrealityweallshareischangingrapidly, especiallywhenitcomestopictures.11