2 SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY ¬ JULY 27, 2023 Imagine your home, totally organized! Custom Closets | Garage Cabinets | Home O ces | Laundries | Wall Units | Pantries | Wall Beds | Hobby Rooms and more... 2023© All Rights Reser ve d. Closets by Design, Inc Call for a free in home design consultation and estimate 312-313-2208 www.closetsbydesign.com SSW Locally Owned and Operated Licensed and Insured SPECIAL FINANCING FOR 12 MONTHS! With approved credit. Call or ask your Designer for details. Not available in all areas 40% O Plus Free Installation PLUS TAKE AN EXTRA 15% O Terms and Conditions: 40% o any order of $1000 or more or 30% o any order of $700-$1000 on any complete custom closet, garage, or home o ce unit. Take an additional 15% o on any complete system order. Not valid with any other o er. Free installation with any complete unit order of $850 or more. With incoming order, at time of purchase only. O er not valid in all regions. Exp. 6/30/23.

SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY

The South Side Weekly is an independent non-profit newspaper by and for the South Side of Chicago. We provide high-quality, critical arts and public interest coverage, and equip and develop journalists, artists, photographers, and mediamakers of all backgrounds.

Volume 10, Issue 21

Editor-in-Chief Jacqueline Serrato

Managing Editor Adam Przybyl

Senior Editors Martha Bayne

Christopher Good

Olivia Stovicek

Sam Stecklow

Alma Campos

Politics Editor J. Patrick Patterson

Labor Editor Jocelyn Martínez-Rosales

Immigration Editor Wendy Wei

Community Builder Chima Ikoro

Public Meetings Editor Scott Pemberton

Contributing Editors Jocelyn Vega

Francisco Ramírez Pinedo

Visuals Editor Kayla Bickham

Deputy Visuals Editor Shane Tolentino

Staff Illustrators Mell Montezuma

Shane Tolentino

IN CHICAGO

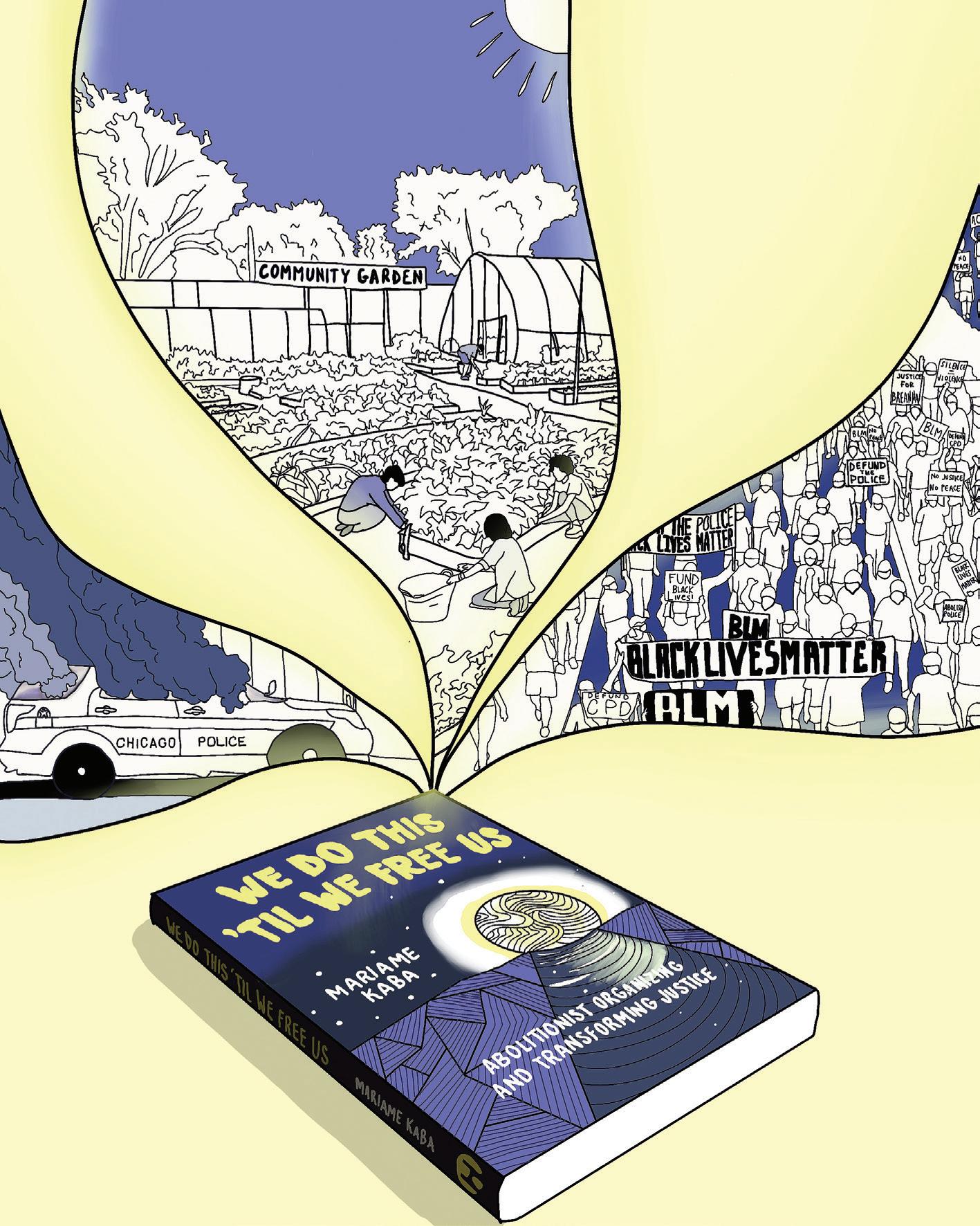

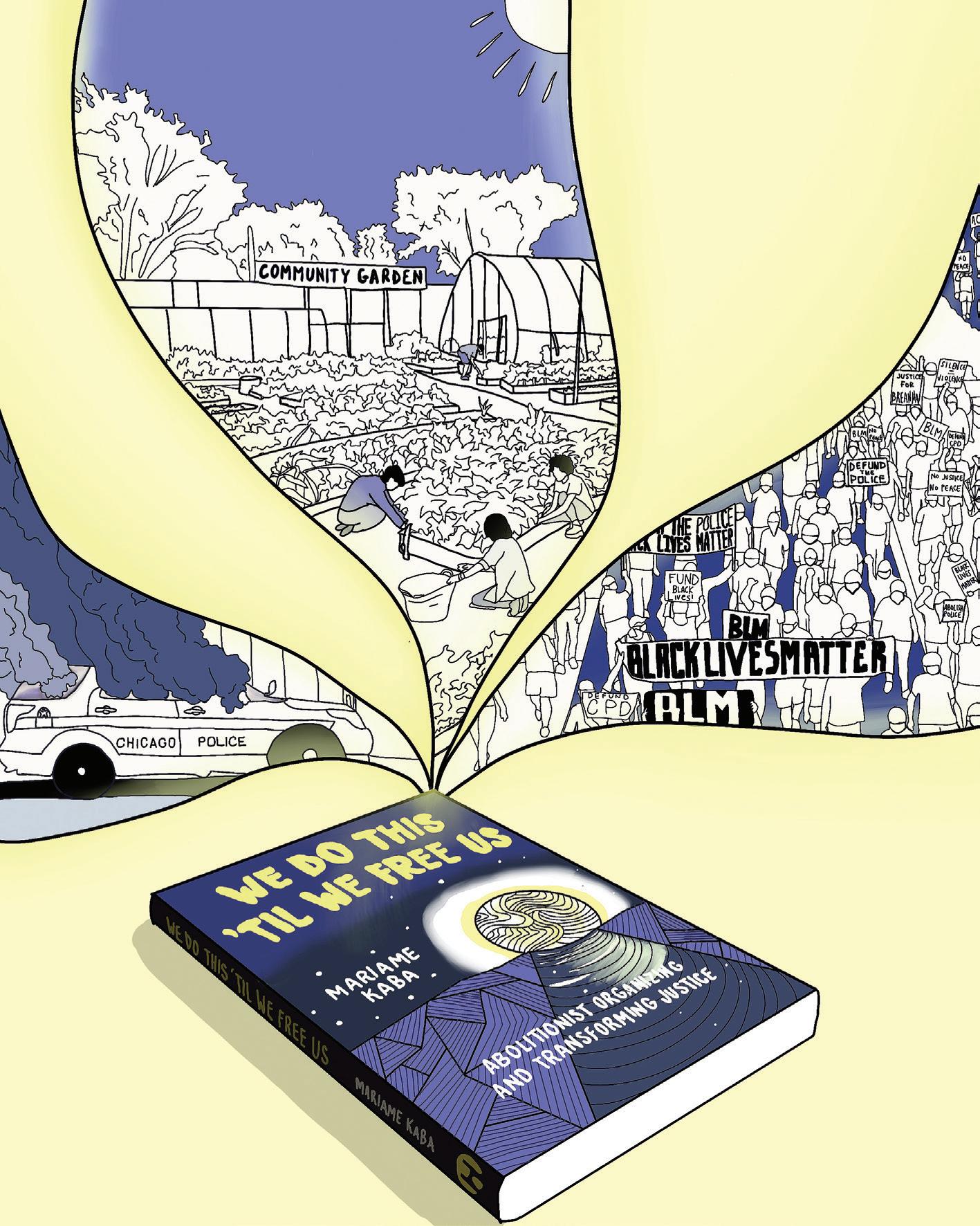

Welcome to the Lit Issue

This year's Literary Issue is centered around radical writing, transformative legislation, community, and self care as an act of resistance. In the featured book reviews, writers explore the complexities of Black art, the grief that comes with rest, and timeless abolitionist writing. This includes a community review of We Do This Til We Free Us by Mariame Kaba, as well as a Q&A with co-author Kelly Hayes on their latest book, Let This Radicalize You. An expanded version of The Exchange, the Weekly’s poetry corner, features poems in response to this issue's central prompt; how do you practice and experience radical self-love, revolutionary thought (or action), or the reclamation of freedom and community? With the help of South Side Weekly’s team and contributors, this special issue was curated by Chima Ikoro, the Weekly’s Community Builder.

First state to eliminate cash bail

The Illinois Supreme Court ruled in favor of eliminating the state’s cash bail system. In a 5-2 ruling on July 18, the court overturned an Illinois judge’s ruling from December which held that a new law ending cash bail in the state was unconstitutional. Around the U.S., about two-thirds of people held in jail have not been convicted of a crime. Many wait weeks, months, or even years for their trial simply because they can’t afford bail. That’s because the system of cash bail has historically allowed income to be the determining factor in whether someone is forced to stay in jail before their trial, effectively criminalizing poverty.

IN THIS ISSUE

illinois outlaws book bans—but not for incarcerated people

It’s the first state to pass legislation enacting penalties for censorship in public libraries.

Director of

Fact Checking: Savannah Hugueley

Fact Checkers:

Sydni Baluch

Lauren Doan

Christopher Good

Kate Linderman

Alani Oyola

Kelli Jean Smith

Layout Editor Tony Zralka

Program Manager Malik Jackson

Executive Director Damani Bolden

Office Manager Mary Leonard

Advertising Manager Susan Malone

Webmaster Pat Sier

The Weekly publishes online weekly and in print every other Thursday. We seek contributions from all over the city.

Send submissions, story ideas, comments, or questions to editor@southsideweekly.com or mail to:

South Side Weekly 6100 S. Blackstone Ave. Chicago, IL 60637

For advertising inquiries, please contact: Susan Malone (773) 358-3129 or email: malone@southsideweekly.com

For general inquiries, please call: (773) 643-8533

In February 2021, Illinois was the first state to completely eliminate this system when Governor J.B. Pritzker signed the Illinois Pre-Trial Fairness Act. This was part of the larger Safety, Accountability, Fairness, and Equity-Today Act (SAFE-T Act), a sweeping criminal justice reform package introduced by the Illinois Black Caucus. Largely in response to disinformation being spread about the law, Pritzker signed a series of amendments and clarifications to the SAFE-T Act in December 2022.

Originally set to take effect in January, the new system will go into effect September 18. Under this law, judges across Illinois will not require people charged with a crime—other than those considered to be a threat to the public or likely to flee—to post bail in order to leave jail prior to their trial.

Howard Brown Health ruling by NLRB

Howard Brown Health, a LGBTQ+ healthcare organization, was found guilty by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) of unfair labor practices and union busting. Last August, employees at Howard Brown Health unionized under Howard Brown Health Workers United, an affiliate of the Illinois Nurses Association (INA). Since then, mass layoffs of more than sixty employees occurred during contract negotiations. This led to around 440 workers striking for three days in January.

Of the sixteen filed complaints by INA against Howard Brown to the NLRB, eight have been found to have merit while the rest of the accusations are still under investigation. NLRB found Howard Brown to be bargaining in bad faith, refusing to negotiate during layoffs, and surveilling union meetings. NLRB is trying to reach a settlement with Howard Brown. If a settlement is not reached, a hearing will determine remedies for workers impacted by the unfair labor practices.

Killian

gretchen sterba

4 chicago public library turns 150

From the first library being housed in a water tank to becoming an essential location in every Chicago neighborhood, CPL has come a long way.

olivia zimmerman................................... 5 black jewel of the midwest

The Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature is about to become more accessible than ever.

kit ginzky

community review of mariame kaba’s we do this ‘til we free us

Four writers share how the 2021 book has influenced them.

rubi valentin, alycia kamil, melissa castro almandina, chima ikoro

8

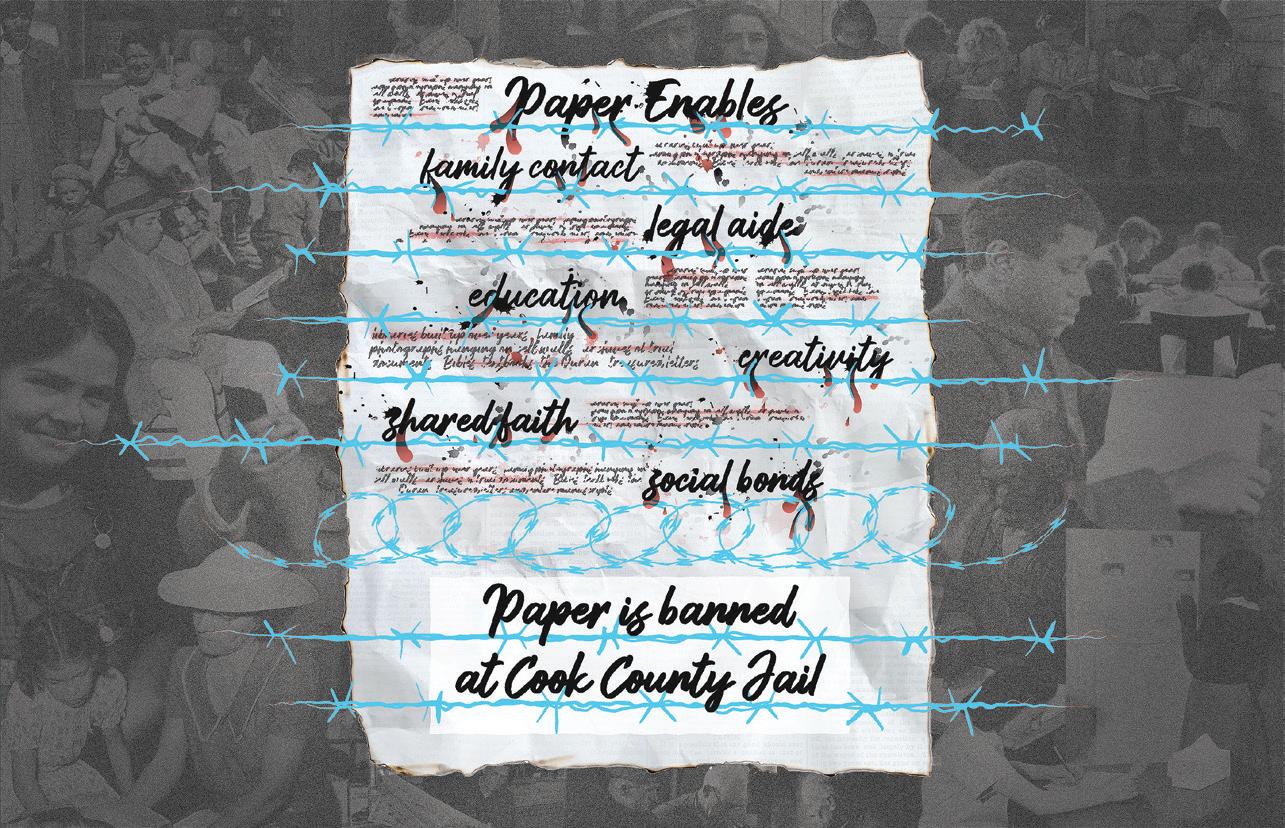

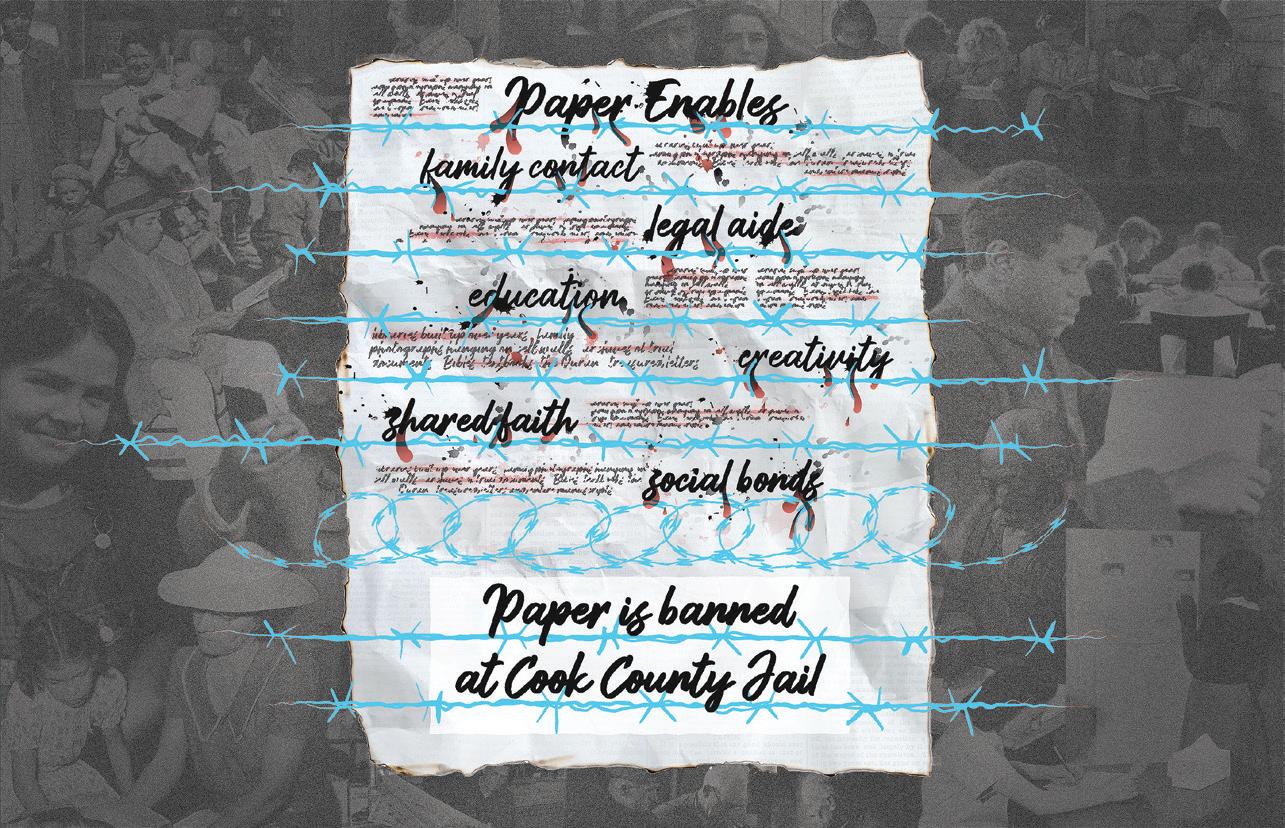

11 op-ed: paper ban at cook county jail restricts access to letters, books and learning material

Altogether, CCJ’s new mail procedures suppress the education and connection that makes life in jail livable.

midwest books to prisoners

15 seeing yourself in the future you’re fighting for

Q&A with Let This Radicalize You co-author Kelly Hayes.

jocelyn martinez-rosales ...................

17 the exchange: marketplace

In this special segment of The Exchange, readers share how they experience radical self love, freedom, and more.

chima “naira” ikoro, c. lofty bolling, arianne elena payne, shivani kumar, lou heron, claude robert hill iv, imani joseph

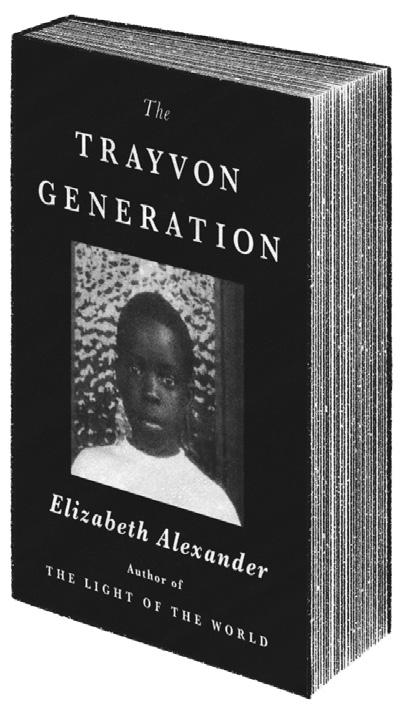

19 the trayvon generation conveys the timelessness of black art

Elizabeth Alexander’s book marries essays with striking visual representations.

sabrina ticer-wurr ..............................

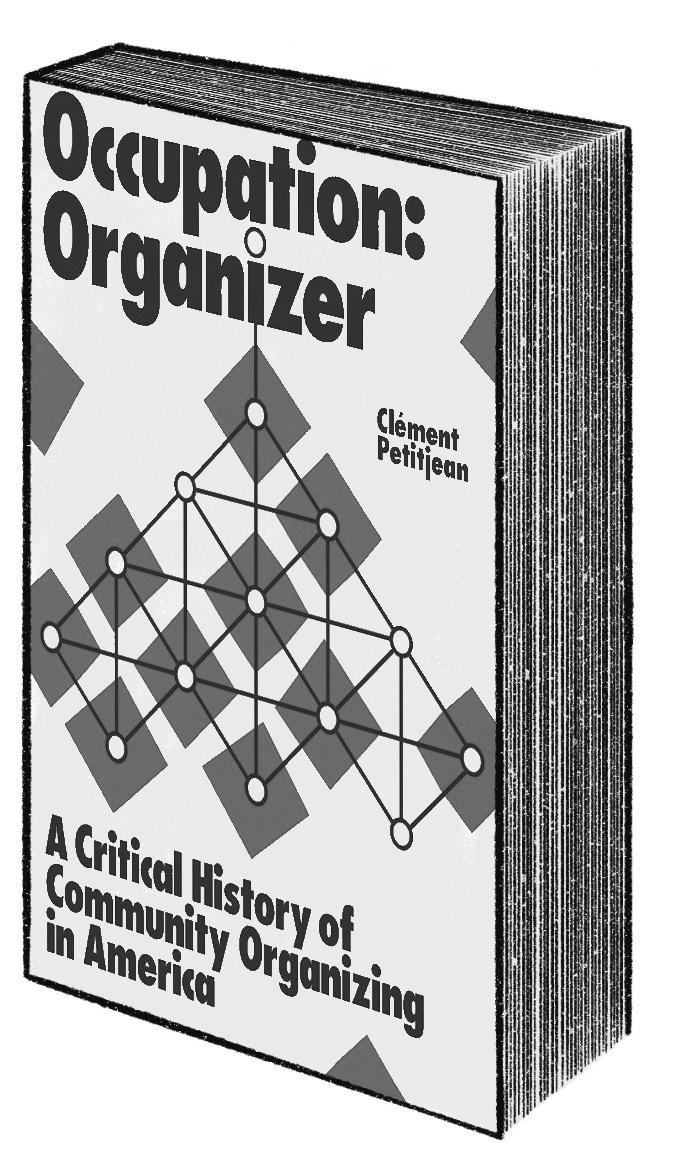

22 organizing and the future of the american experiment

A new book spells out where community organizing has been but stops short of imagining where it might go.

scott pemberton

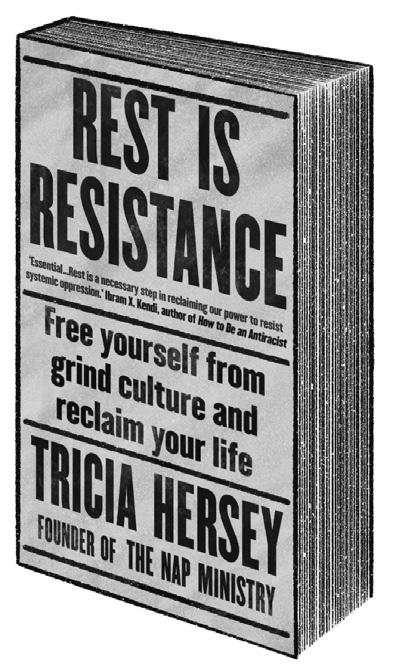

23 the gospel of the nap bishop

Tricia Hersey continues to champion the freedom and grief that comes with resting and dreaming in Rest Is Resistance: A Manifesto.

jasmine barnes

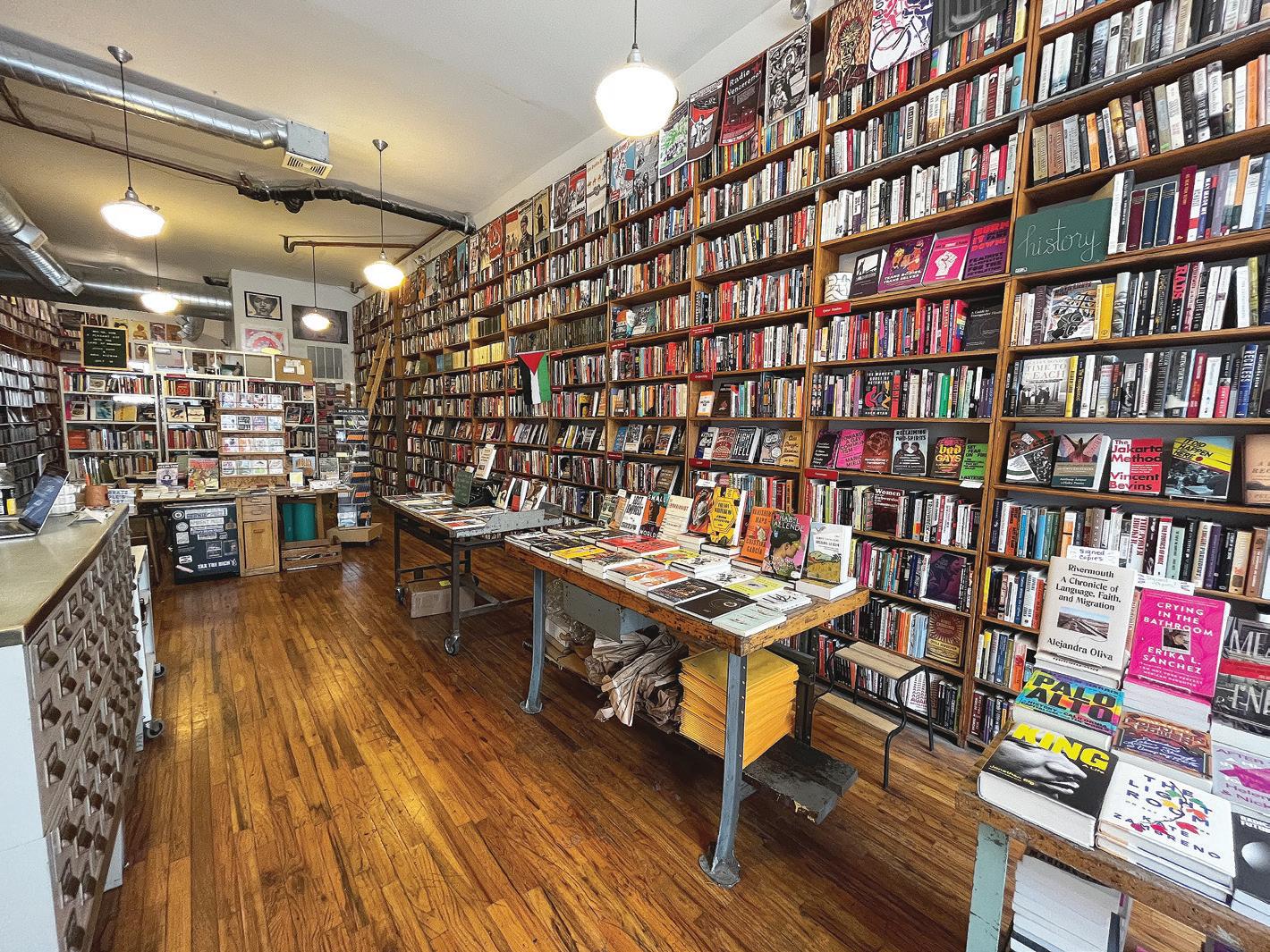

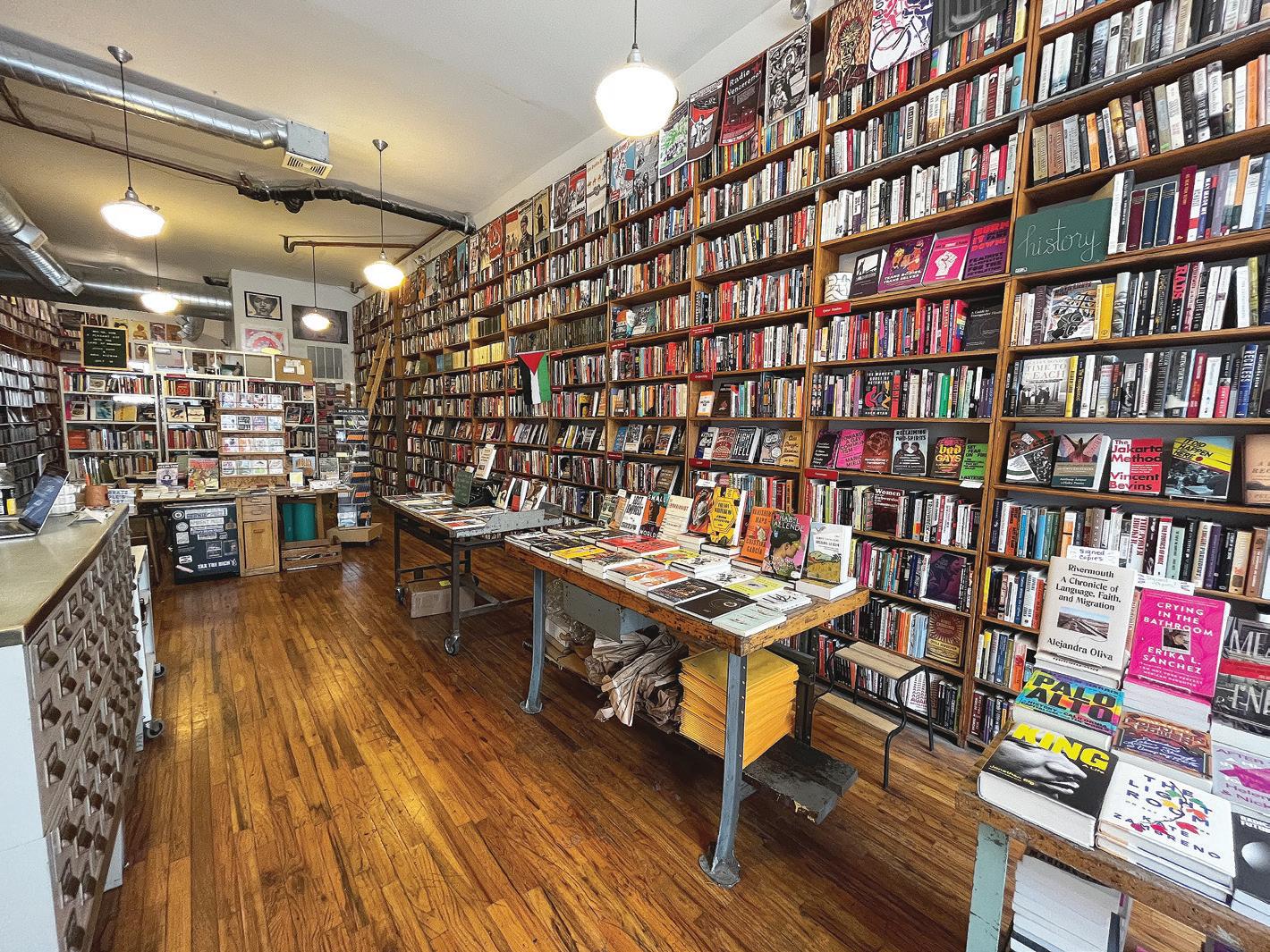

26 your friendly (and only) employee-owned neighborhood bookstore

Co-owner Mandy Medley talks about passion, connections, and how selling books is, ironically, not about getting paper.

chima ikoro 27

Cover illustration by Bridget

Illinois Outlaws Book Bans—But Not for Incarcerated People

With Illinois making national news for being the first state in the country to pass legislation enacting penalties for censorship in public libraries, those who are incarcerated aren’t included in the state’s victory.

On June 12, Governor JB Pritzker signed historic legislation declaring Illinois the first state in the country to remove state funding from public libraries if they were to ban books. The bill is to be enacted on January 1, 2024.

This decision comes after a recordbreaking increase in book challenges in 2022—amounting to over 1,200 challenged books, nearly double what it was in 2021, reports the American Library Association (ALA).

Alex Gough, the press secretary for Governor Pritzker, told South Side Weekly in an exclusive statement, “Across the nation, extremists are targeting literature, libraries, and books in a despicable effort to censor the material students need to thrive in the classroom. Governor Pritzker’s purported goal is to preserve Illinois libraries as bastions of knowledge, creativity, and truth. In Illinois, we embrace facts, and we trust librarians to continue maintaining a standard for what books students have access to at school.”

On July 6, the governor tweeted: “Here in Illinois, we don't hide from the truth, we embrace it. By outlawing book bans, we’re showing the nation what it really looks like to stand up for liberty.”

Even so, not everyone in the state of Illinois can feel included in Pritzker’s stance.

While punchy national headlines announce that Illinois has outlawed book bans, Chicago Books to Women in Prison board president Vicki White can’t help but point out that this bill applies only to public libraries, not Illinois jail and prison libraries, or books sent by mail that are

regulated by the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC).

In response to the governor’s tweet, White, who has been involved with the volunteer-run nonprofit organization for over a decade, urges the state to incorporate incarcerated folks in Pritzker’s declaration to “stand up for liberty.”

“I would just ask Pritzker to spearhead the same type of action in prisons, and not just prison libraries but prisons in general,” White said. “Because there are the books in the prison libraries, but books from organizations like ours go through the mail room. Another thing that would be excellent would be for an [assessment] to

third most challenged for “sexually explicit content.” The 1970 novel depicts incestuous abuse. The young adult novel The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, by Sherman Alexie, was ranked number eight for “profanity” and being “sexually explicit;” the novel details the experiences of a young Native teenager growing up on a reservation.

Moms for Liberty is a conservative organization that advocates against LGBTQ+ and social justice-related content in school and classroom libraries. Although they mainly have found adherents in more conservative states like Florida, Indiana, and South Dakota (not far from Chicago), some Illinois parents perpetuate these

conservative talking point, Jensen says this kind of work has been happening for decades and that right-wing organizers and lawmakers are in it for the “long game.”

“I always like to really emphasize that I don't give a shit about the books,” Jensen says. “I give a shit about the people that are represented by those books, the people that are seeing themselves in those books, the people who can share themselves in those books, and at the end of the day, it's the people.”

Chicago Public Library Commissioner Chris Brown also spoke to the Weekly about the importance of representation and telling the stories of young Black and Indigenous people and other people of color.

In 2022, CPL declared all of its eightyone library branches “book sanctuaries,” meaning those who enter any given CPL space have the “freedom to read” anything, including endangered books.

happen from the top; fold in the prison library system into the Illinois library system and [take it] out of the Illinois Department of Corrections…JB Pritzker, [I] love what you're saying. Maybe just think a little more broadly.”

Last year was a monumental year for challenged books. In 2022, some of the most attempted bans included books about gender or LGBTQ+ issues— such as Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe, which the ALA ranked as most challenged—or books written by Black and Brown authors. Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, despite being a classic, was ranked at

extremist ideals.

Just this past November, parents showed up to a polarizing library board meeting in north-suburban Lincolnwood to debate the inclusion of children’s books discussing LGBTQ+ themes—specifically the picture book The Hips on the Drag Queen Go Swish, Swish, Swish.

Kelly Jensen, an editor at Book Riot, North America's largest independent book website, has worked at the outlet for nearly a decade. Previously, Jensen worked as a public librarian in Illinois and Wisconsin and has since been reporting on book censorship, especially in recent years. While the idea of book bans has become a popular

While Brown cites states like Florida and Texas as being two of the most vigilant about attempting to ban books and enact censorship across libraries and schools, he reiterates that this shouldn’t be the norm.

“I think this representation issue is incredibly important, and the danger, I think, is in creating norms in other parts of our country that others start to look at and think that that's appropriate,” Brown said.

“It's hard to say, what gets normalized in one state down the road, does that get normalized even more? Do we start to see a critical mass of people saying that this is the route we want to go as a country? […] Norms can be rolled back. And I think that's really disconcerting for our diverse communities, especially in Chicago.”

4 SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY ¬ JULY 27, 2023 LIT

BY GRETCHEN STERBA

“Until we are all afforded the same rights and regulations under state legislation, we cannot celebrate Illinois being a champion for all.”

It’s fair to want to celebrate this legislative win in Illinois—after all, Jensen just reported that both Pennsylvania and Massachusetts are proposing antibook-ban bills in the wake of Pritzker’s decision.

But as Illinois Public Media reported in 2018, in the year 2017 alone, the IDOC spent less than three hundred dollars on new relevant educational materials throughout its twenty-eight state prisons. In the early 2000s, that cost was exponentially larger, stacking up to $750,000 spent on books each year, but by 2005 the cost shrank to $264,000.

According to a 2023-updated article by The Marshall Project about banned books in prisons by state, while most of the titles are pornographic, the list also includes books on Asian martial arts, the fundamentals of tattooing, how to write believable fight scenes, and Prison Ramen, which details prison recipes and personal narratives from incarcerated inmates. In contrast, Mein Kampf is banned in Illinois, but inmates are free to read it in Texas, according to a 2019 Illinois Library Association article.

Jensen, whose book ban reporting has also covered prisons, says that prison censorship doesn’t get nearly as much media attention as public schools and libraries because “there’s still this ongoing stigma.”

“People are far more invested in their public libraries and in their public schools than they are in the prison system,” Jensen said.

“There’s this ongoing belief that folks who are experiencing incarceration don't deserve the chance to be people or that they can't be rehabilitated or that they don't deserve that. We know and can cite that prison censorship is the worst censorship in the country.”

WBEZ reported on this in 2018 as well, citing that research showed books have an immense chance to impact an inmate’s release and can help them become more civic-minded.

“So yes, this [Illinois] legislation is awesome and important, but there's also this huge missing component,” Jensen said.

“That all said, there's really interesting legislation at the national level that is looking at prison censorship. I think if we continue to talk about that and continue to advocate for it, if we have folks on the ground who are in the ears of the legislators

at the state level, maybe we can get something going for the next term as well.”

While Chicago Books to Women in Prison is based in Illinois, the organization sends books to women and trans women across state lines to correctional facilities in places like Indiana, Mississippi, and Florida, where book bans can be more restrictive.

White says a popular book that is often requested and that is often sent back is the 2014 comprehensive resource guide Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, which covers health and wellness for trans and gender nonconforming people. And like Jensen, White said she believes that when people are incentivized or held accountable for a shift in cultural norms, that is how palpable change, for all people, especially vulnerable groups, can occur.

“If the prison libraries in Illinois could be run by Illinois prison library systems and be eligible for funding and have the same standards in terms of access to books, as people out here have, that would be excellent,” White said.

“For example, [in] Trans Bodies, Trans Selves [there are] perfectly clinical illustrations that serve an important educational purpose. People change when they're rewarded to change or when there are penalties to not changing. Sometimes that can come through public attention and protests and that kind of action. But, it has to do with the Illinois Department of Corrections.”

While Pritzker’s legislation is monumental for not just our state but as a leader of the nation, in the words of Mariame Kaba (whose book is banned in states like Louisiana), “We do this ’til we free us.” Until we are all afforded the same rights and regulations under state legislation, we cannot celebrate Illinois being a champion for all.

“We’re showing everyone what it looks like to stand up for liberty. As simple as that,” read Pritzker’s tweet. But White reminds us to challenge our leaders and policymakers to include incarcerated people in that same victory. ¬

Gretchen Sterba is a freelance journalist based in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago. She’s written for the Chicago Reader, HuffPost, BUST Magazine, and more. She last wrote for the Weekly about musician Shawnee Dez.

Chicago Public Library Turns 150

BY OLIVIA ZIMMERMAN

Chicago Public Library (CPL) will celebrate its 150th birthday this year, commemorating the opening of the city’s first public library in 1873. While private libraries already existed, the Chicago Public Library system was born out of ashes, opening only two years after the devastating Great Chicago fire. The first library opened in a repurposed water tank on LaSalle and Adams that had survived the fire, and was created as a type of charitable book depository where members of the English Aristocracy donated books to the city . As time went on, CPL evolved to fit the community. What started as free libraries for the public turned into what is now a place for community outreach, teaching, and recreation, bringing Chicago’s neighborhoods together.

In 1897, the library moved to a larger, more permanent location in what is now the Chicago Cultural Center. The land where the building sits required the inclusion of a memorial hall in honor of soldiers and sailors from Illinois. This is the reason the paintings on the walls of the Chicago Cultural Center include Civil War scenes.

The new building was larger than the original water tank and designed to be “practically incombustible” in the event of a fire. To this day, the Chicago Cultural Center building is thought to have the largest Tiffany glass dome in the world.

In 1904, CPL opened its first neighborhood branch, Blackstone, in Hyde Park bordering Kenwood. The building was designed in the Greek style, inspired by the Erechtheion in Athens. The inside features marble and gold details, as well as several murals representing labor, science, literature, and art.

While the beauty of the building still draws attention, today the Blackstone Branch holds much more than books. When the <i>South Side Weekly</ i> visited the library for this story, a performer was singing songs for kids, and posters and handouts described not only library events, but also community programming, events, and meetings for Hyde Park residents. Another poster detailed how to use inclusive language when discussing substance abuse.

Simply pulling up the calendar of events for CPL exemplifies how diverse

JULY 27, 2023 ¬ SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY 5 LIT

From the first library being housed in a water tank to becoming an essential location in every Chicago neighborhood, CPL has come a long way.

the patrons of the library are, and how CPL has adapted to meet the needs of many different communities. From teen poetry meetings to classes on computer literacy, CPL has much to offer. This is intentional, according to CPL commissioner Chris Brown.

“Over the last couple of decades we’ve really built our libraries and developed them from what were primarily storefront locations. It really goes back to our history. After the Great Chicago Fire we didn’t have a public library so our first location was in a water tank. It’s also kind of poetic, our first library was something that survived the fire, something that was a beacon of hope, something that didn’t burn down.”

CPL has focused on creating branch libraries that are within walking distance for every Chicagoan, Brown explained. “A lot of our early libraries were inside stores; they were called book depositories. We also had reading rooms out of fieldhouses,” said Brown. “[However,] it was really our chief librarian, Henry Legler, in the early twentieth century who created this plan for walkable library access in every neighborhood. That is something we’ve continued to build upon.”

The first of these libraries was a regional library named after Legler, opened in the West Garfield Park neighborhood. Regional libraries are larger, with more space for programming, more staff, and larger collections of books.

Currently, Chicago Public Library has eighty-one locations serving their mission to “welcome and support all people in their enjoyment of reading and pursuit of lifelong learning. Working together, we strive to provide equal access to information, ideas and knowledge through books, programs and other resources. We believe in the freedom to read, to learn, to discover.”

Through this mission and in more recent years, the role that libraries and librarians play in their communities and branches has evolved.

This year, library cardholders have used CPL computers, which are available to the public and have become a crucial commodity for all, more than 500,009 times.

In response to the current opioid crisis, librarians have been trained to administern Naloxone, a lifesaving drug that can reverse the effects of an overdose.

The library also has “Money Smart” events, partnering with the Federal Reserve of Chicago to give financial literacy classes. For students, the libraries offer free homework help on school days.

In the current political environment, libraries are under attack. CPL has stepped up to the plate against attempts to

History and Literature was then moved to Woodson Library. Harsh was the first Black woman to head a branch in the 1930s, and the collection is “one of the largest repositories of information on the Black experience in the Midwest.”

In 1991, a new central library on State and Jackson was completed—the Harold Washington Library, named after Chicago’s first Black mayor, who had passed away in 1987.

CPL is only growing. “We are building… the first-ever library branch on a presidential center site. It’ll be the first public library that a president has invested in,” said Brown.

“We’ve also just announced this

the Little Italy branch, some on the North Side; but we most recently opened the Altgeld branch on the far South Side. [This branch] includes a childcare center,” said Brown.

For the future of the library, building the staff at CPL is imperative to continuing community support, according to Adams.

“One of the best ways to ensure that we continue to see diverse collections and welcoming spaces is to also ensure that we have a diverse staff. I want the young people in our communities that might be interested in librarianship to have access to a path to this profession. CPL has been partnering with After School Matters for many years to create hundreds of internships each summer for high school students in the library, and I’ve gotten to see former interns apply to jobs at CPL after high school or college to start their career with us.” ¬

The CPL calendar will list events celebrating this major anniversary throughout the city this year, as well as hosting several exhibitions on CPL’s history. CPL is also starting a podcast on their history and libraries.

censor books. “Last year CPL established ourselves as a Book Sanctuary,” said Deanie Adams, a CPL regional director.

“We also hosted the signing of HB2789 last month at the Thomas Hughes Children’s Library in Harold Washington Library Center—which prohibits Illinois public libraries from banning books. These book challenges are particularly insidious once you take a closer look at the titles that are most challenged, which disproportionately are books that are by and about people of color and members of the LGBTQ+ community.”

In 1975, CPL commemorated Vivian G. Harsh by renaming the collection she’d worked on after her. The Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American

year’s funding to update and renovate the Woodlawn library, known as the Bessie Coleman Branch. We are working with the community to really plan, develop, and design that. We have continued to evolve our libraries.”

In addition, CPL has created partnerships with various City of Chicago departments to make their services go further. Library access and the many resources that CPL offers are crucial in disinvested and marginalized communities.

“We have a number of innovations in the last decade that were in partnership with the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA). These are co-locations where we both build affordable housing in proximity to library branches. We have

Olivia Zimmerman is a writer and historian from Chicago. This is her first time writing for the Weekly

6 SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY ¬ JULY 27, 2023

LIT

“It’s also kind of poetic, our first library was something that survived the fire, something that was a beacon of hope, something that didn’t burn down.”

CPL Commissioner, Chris Brown

exp. with advanced signal & image processing algorithms; & 2 yrs. exp. using Matlab, Python & C/C++.. Send resume (no calls) to: Jonathan Gunn, Briteseed, LLC, 4660 N. Ravenswood Ave., Chicago, IL 60640

Help Wanted 001

DENTISTS

The Dental Clinic, LLC in Chicago, IL seeks qualified dentists. Provide dental services to patients. DDS in Dentistry (Will accept DMD in Dentistry) or a foreign academic equivalent plus background or coursework in prosthodontics, periodontics, endodontics, pediatric dentistry, orthodontics, oral pathology, oral surgery, and radiology Dental license req. 40 hrs/ wk. Send cover letter & resume to:

Dental Dreams, LLC, Attn: Peter Stathakis, 350 N. Clark St, Suite 600, Chicago, IL 60654. Refer to ad code DD-102083.

Cleaning Service 070

Best Maids 708-599-7000 House Cleaning Services Family owned since 1999 www.bestmaids.com

Construction 083

JO & RUTH REMODELING We Specialize in Vintage Homes and Restorations! Painting, Power Washing, Deck Sealing, Brick Repair, Tuckpointing, Carpentry, Porch/Deck, Kitchen & Bath *Since 1982* 773-575-7220

Masonry 120

Accurate Exterior and Masonry Masonry, tuckpointing, brickwork, chimneys, lintels, parapet walls, city violations, We are licensed,

Free Estimates 773-592-4535

MICHAEL MOVING We Move, Deliver and Do Clean-Out Jobs 773.977.9000

JULY 27, 2023 ¬ SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY 7 SERVICE DIRECTORY To place your ad, call: 1-7 73-358-3129 or email: malone@southsideweekly.com Ad copy deadline: 1:00 p.m. Friday before Thursday publication date KELLY PLASTERING CO. PLASTER PATCHING DRYVIT STUCCO FULLY INSURED (815) 464-0606 BUSINESS & SERVICE SHOWCASE: Conrad Roofing Co. of Illinois Inc. SPECIALIZING IN ARCHITECTURAL: METAL WORK: • Cornices • Bay Windows • Ornaments • Gutters & Downspouts • Standing & Flat Seam Roofs ROOFING WORK: • Slate • Clay Tile • Cedar • Shingles • Flat/Energy Star Roof (773) 286-6212 Mike Stekala Construction 773-879-8458 www.mstekalaconstruction.com ROOFING INSPECTIONS Roofing License #104.16667 FREE Estimates - Insured PICTURE YOUR BUSINESS HERE! Advertise in the Business & Ser vice Director y today!! Build Your Business! Place your ad in the Business & Service Directory! MOVINGPLASTERINGPLUMBINGMICHAEL MOVING COMPANY Moving, Delivery and Cleanout Jobs Serving Hyde Park and surrounding communities 773-977-9000 KELLY PLASTERING CO. PLASTER PATCHING DRYVIT STUCCO FULLY INSURED (815) 464-0606 Call 773-617-3686 License #: 058-197062 10% OFF Senior Citizen Discount Residential Plumbing Service SERVICES INCLUDE: Plumbing • Drain Cleaning • Sewer Camera/Locate Water Heater Installation/Repair Service • Tankless Water Heater Installation/Repair Service Toilet Repair • Faucet/Fixture Repair Vintage Faucet/Fixture Repair • Ejector/Sump Pump • Garbage Disposals • Battery Back-up Systems Licensed & Insured • Serving Chicago & Suburbs Conrad Roofing Co. of Illinois Inc. SPECIALIZING IN ARCHITECTURAL: METAL WORK: • Cornices • Bay Windows • Ornaments • Gutters & Downspouts • Standing & Flat Seam Roofs ROOFING WORK: • Slate • Clay Tile • Cedar • Shingles • Flat/Energy Star Roof (773) 286-6212 CONSTRUCTIONCLEANING708-599-7000 House Cleaning Ser vices Family owned since 1999 www.bestmaids.com MASONRYMASONRY, TUCKPOINTING, BRICKWORK, CHIMNEY, LINTELS, PARAPET WALLS, CITY VIOLATIONS, CAULKING, ROOFING. Licensed, Bonded, Insured. Rated A on Angie’s List. FREE Estimates Accurate Exterior & Masonry 773-592-4535 HELP YOUR BUSINESS GROW! Advertise in the South Side Weekly’s Business & Ser vice Director y. Call today! 1-773-358-3129 email: malone@southsideweekly.com ROOFINGMike Stekala Construction 773-879-8458 www.mstekalaconstruction.com ROOFING INSPECTIONS Roofing License #104.16667 FREE Estimates - Insured –––CLASSIFIED Section ––He lp Want ed 00 1 Help Want ed 00 1 Help Wanted 001 Polar Operations LLC d/b/a IMC Markets (Chicago, IL), seeks an experienced professional Systems Engineer to play a critical role in maintaining and perfecting IMC’s trading systems. Interested candidates should send resume to: talent@imc-chicago.com with “Systems Engineer” in subject line. Lead Signal Processing Engineer Job location: Chicago, IL. Duties: Develop adv signal & image processing algorithms to achieve real-time ident. & localization of anatomical structures in surgical field. Perform coding & develop. platforms using C/C++, MATLAB, Python, PyTorch, Tensorflow & Git. Develop & optimize deep learning networks for hyperspectral imaging cubes for classification of medical signals. Design optical hardware test rigs & prototypes that utilize unique, linear CMOS sensors, optical filters, & LED illum. specific to Briteseed’s proprietary optical subsystem for surgical tools. Requires: M.S. (or foreign equiv.) in Elec. Eng. or related field & 2 yrs.’ exp. in job offered or 2 yrs.’ exp. as a Processing Eng. Concurrent exp. must incl: 2 yrs.

Movers 123 KELLY Plastering Co. 815-464-0606 Plastering 143 CONRAD ROOFING CO Specializing in Architectural Metal Work, Gutters & Downspouts, Bay Windows, Clay Tile, Cedar, Shingles, Flat/Energy Star Roof 773-286-6212 The Plumbing Department Available for all of your Call Jeff at 773-617-3686 Mike Stekala Construction Gutters - Clean GuttersTuckpointing Chimney Repair - Plumbing Service - Electric Service Windows – PaintingTrim and Cut Down Trees Junk Removal from Houses, Garages, 773-879-8458 www.mstekalaconstruction.com 2007 Toyota Yaris 773-493-9254 Let Us Help Build Your Business! Advertise in the Business & Ser vice Director y Today!! Ad copy deadline: 1:00 p.m. Friday before Thursday publication date. To Place your ad, call: 773-358-3129 or email: malone@southsideweekly.com Let Us Help Build Your Business! The South Side Weekly will get your business noticed! Call: 773-358-3129 or email: malone@southsideweekly.com Let Us Help Build Your Business! Advertise in the South Side Weekly Today!! Advertise in the South Side Weekly Today!!

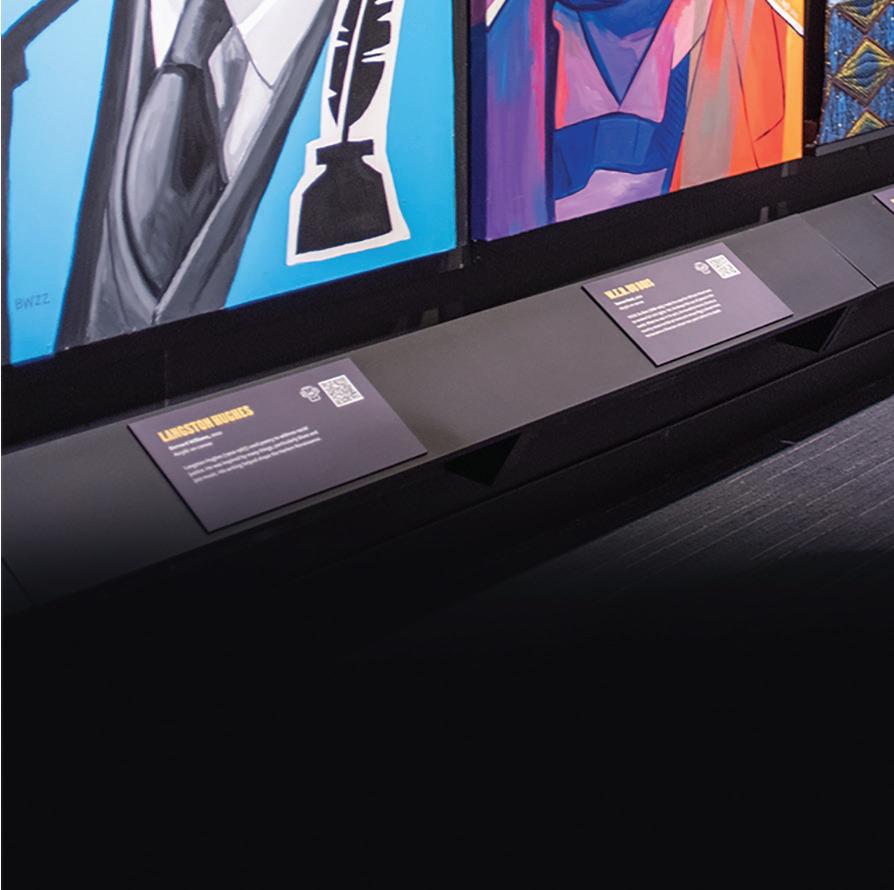

Black Jewel of the Midwest

BY KIT GINZKY

In a 1949 speech celebrating what was then called Negro History Week, W.E.B. Du Bois reflected on the importance of Black history. “It is not merely a matter of entertainment or information,” he said. “It is part of our necessary spiritual equipment for making this country worth living in.”

But in twentieth-century America, even as Black literacy rates increased, educational resources and materials for the study of Black history remained scarce. In Chicago, residents of the segregated “Black Belt” waited decades for a single public library. When Bronzeville’s first Chicago Public Library (CPL) branch finally opened its doors in 1932, head librarian Vivian G. Harsh (1890-1960) worked tirelessly to build one of the nation’s premier collections of books, photographs, manuscripts, and periodicals on the African American experience.

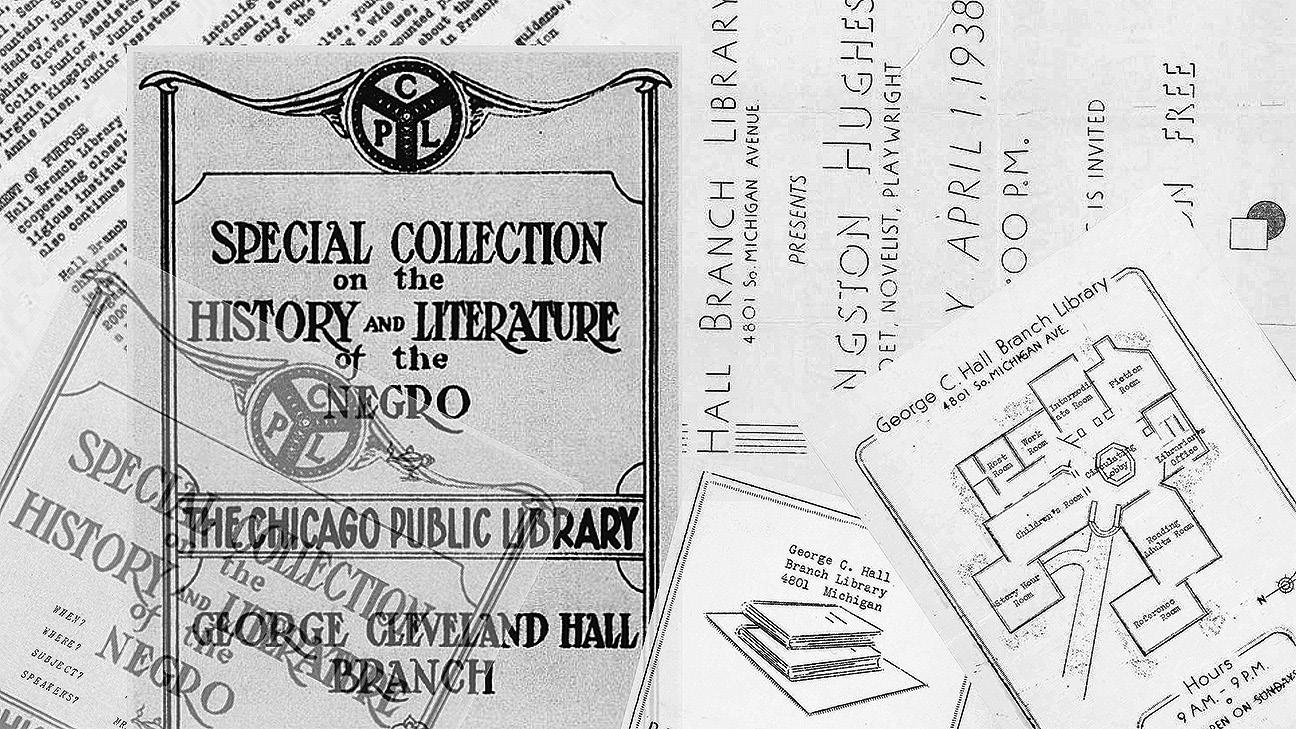

As Harsh built her collection, the CPL branch she ran in the heart of Bronzeville became a community resource and hub for the literary and journalistic laborers of Chicago’s flourishing creative movement known as the “Black Renaissance,” including Richard Wright, Margaret Walker, and Gwendolyn Brooks. Now housed at the Carter G. Woodson Regional Library on the far South Side, the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of AfroAmerican History and Literature has been called the “Black Jewel of the Midwest.”The collection serves as an invaluable resource for writers and students researching African American history, artists looking for inspiration from the past, and anyone interested in a hands-on encounter with the history of Black Chicago.

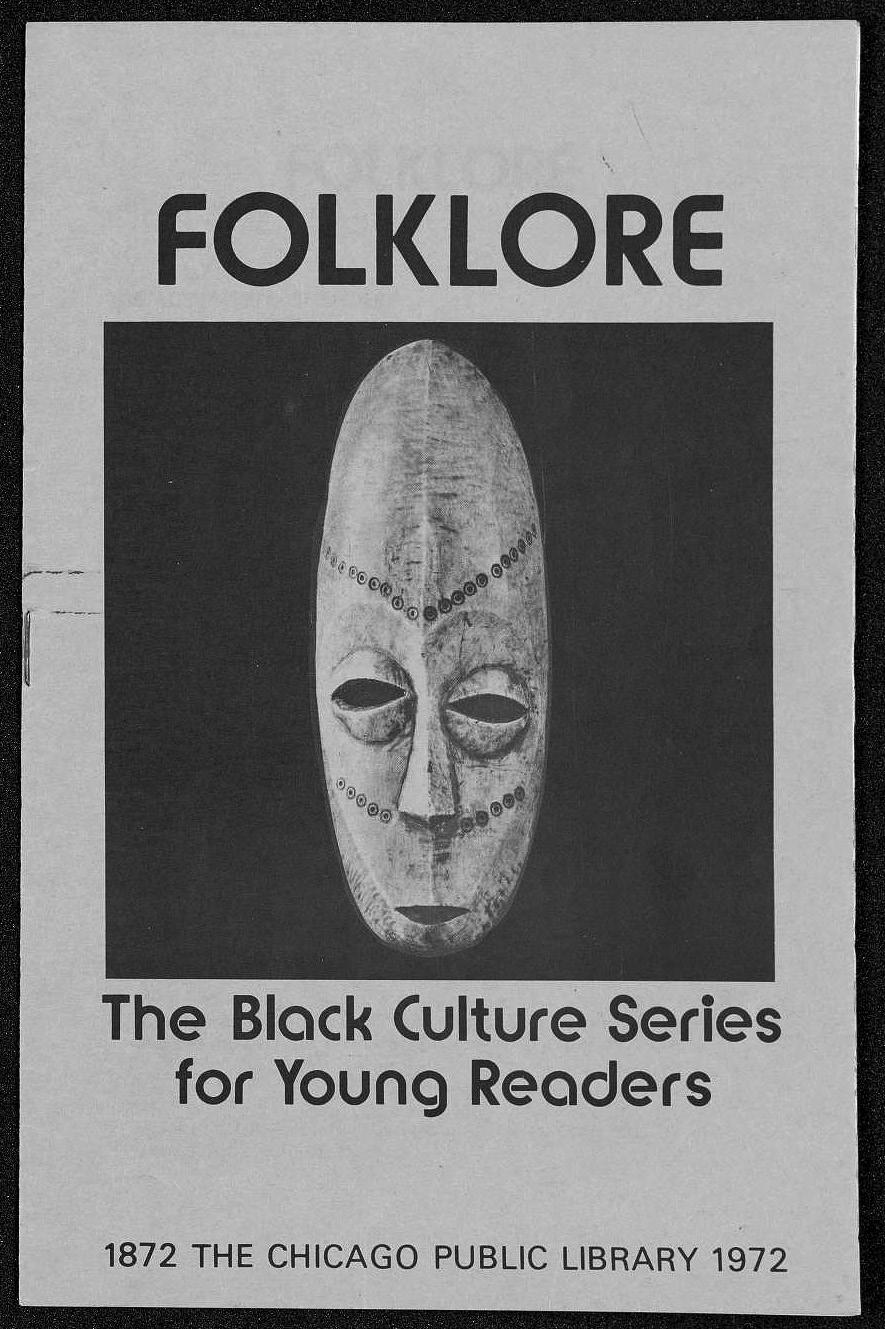

And the collection is about to become more accessible than ever: CPL was recently awarded a $2 million grant from the Mellon Foundation to digitize and

process documents from the collection, including the records of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party, the National Alliance of Black Feminists, the papers of communist and civil rights and labor leader Ishmael Flory, the Chicago SNCC History Project, and a selection of Harold Washington’s political papers. The work is already underway and scheduled to be completed in March 2027.

Harsh’s collection lives on under the stewardship of archivists such as Stacie Williams, chief of archives and special collections at CPL, who celebrates Harsh as someone who “believed very much in the importance of researching Black lives,” and who deeply “understood that Black lives matter.” With this grant and an increased emphasis on digitization, “CPL will continue to honor Harsh’s work by fostering greater access to Black-history-

related collections for everyone,” Williams said in a press release.

Vivian Harsh was a pioneer in Black archiving and librarianship. As the first Black “librarian-in-charge” in Chicago, she was tapped to lead the George Cleveland Hall Branch—the first CPL branch in a Black neighborhood— before it opened at 48th and Michigan in 1932. In this role, she raised funds for the library, assembled its collection, and managed a racially integrated staff of fifteen library workers. Her commitment to building what she called the Special Negro Collection established the Hall library as an eminent destination for Black writers and intellectuals, and cemented Harsh’s position as a leader in the Black Renaissance.

As construction of the Hall Branch

was underway, Harsh received critical support from philanthropist and Sears executive Julius Rosenwald, whose foundation donated the land for the library. A grant from the Rosenwald Fund allowed Harsh to travel around the country purchasing books and visiting libraries that served Black communities, including the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Collection, which became a guiding light for the Special Negro Collection.

Back in Bronzeville, Harsh drew upon her extensive social ties to secure donations of books, clippings, photographs, and ephemera. She especially relied on fellow members of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, a group founded by Carter G. Woodson to promote the preservation, study, and teaching of African American history as a way of fostering Black pride and contesting white supremacy. These early donations, including the bequest of 200 books from Dr. Charles Bentley, a prominent Bronzeville dentist and founding member of the Chicago chapter of the NAACP, marked an important transfer of Black cultural resources from private collections to the public trust.

The George Cleveland Hall Branch opened on January 18, 1932, in the depths of the Great Depression. The library’s opening day celebrations were scaled back due to a lack of funds, but the building itself— designed by the same architectural firm as the Art Institute of Chicago and many of the neo-Gothic buildings on the University of Chicago quadrangle—showed no signs of the market crash. The stone building’s four large reading rooms opened off of an airy octagonal lobby, and the extensive use of dark English oak created a visual continuity between the reading room shelving and an elegantly carved circulation desk in the library rotunda.

8 SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY ¬ JULY 27, 2023

The Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature is about to become more accessible than ever.

LIT

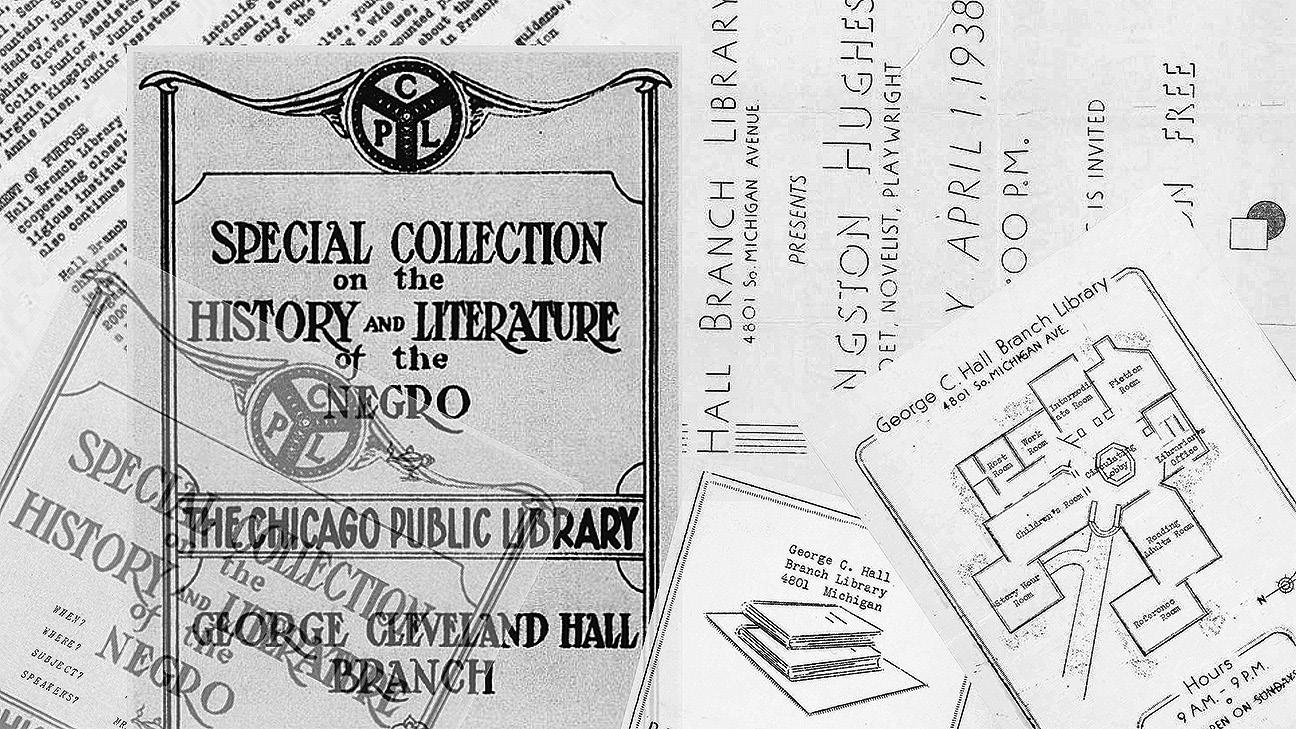

GEORGE CLEVELAND HALL BRANCH DIGITAL COLLECTION, CHICAGO PUBLIC LIBRARY

Like all libraries, the Hall branch issued library cards, circulated books, answered reference questions, and hosted public events. Its resources for leisure, education, and information became all the more vital in light of the economic crisis, and it quickly became a hub of community activity: Harsh led a Great Books discussion group and a club for older adults called “Fun At Maturity,” which was designed to promote friendship and combat isolation. Children’s librarian Charlemae Rollins, a pioneering Black librarian in her own right, organized story hours, a puppet club, and a Negro History Club for high school students. And adult education was at the center of library programming: course options included Spanish, creative writing, social science, and African American History.

Reference services at Hall were especially popular: according to the Chicago Defender, Hall Branch staff answered more than 20,000 questions in 1938 alone, in person and over the phone. But it was the Special Negro Collection and Harsh’s unique point of view that generated national interest and acclaim for the library.

Within the collection are materials from a cohort of luminaries Harsh mentored and gathered into salons: manuscripts by Richard Wright, handwritten poems by Gwendolyn Brooks, letters home written by Timuel Black while he was fighting in the Battle of the Bulge. It also holds vast records of Bronzeville’s professional class— names recognizable by the institutions named for them, like Walter Henri Dyett, Earl B. Dickerson, and a long roster of Black doctors, realtors, artists, journalists, and socialites.

The collection reflects Harsh’s orientation toward community-engaged librarianship and commitment to Black public history: it preserves critical sources of Black history, and its formation is itself an important episode in the history of Black cultural and intellectual life.

Harsh was raised in one of Bronzeville’s Old Settler families, and her social life among the Who’s Who of Black Chicago was frequently reported in the Chicago Defender. This social milieu would have oriented Harsh toward notions of middleclass respectability and race consciousness. In the economically stratified and densely populated Black Belt of the early twentieth century, members of Bronzeville’s elite worked in different ways to distinguish

themselves from the flood of poor, scarcely educated Black migrants moving into the neighborhood from the South.

But Harsh was convinced that promoting education, literacy, and African American history would inspire and uplift the race as a whole. Her Bronzeville upbringing—along with years of experience working her way through the CPL ranks and a degree in library science from Simmons College in Boston—forged Harsh’s approach to librarianship.

to serving this broad public, even as it extended beyond the boundaries of the Hall branch’s main service area.

When patrons showed interest in studying African American history and culture, Harsh encouraged them to take their scholarly pursuits seriously and to contribute to the knowledge base. The late Vernon Jarrett, an eminent Black journalist, remembered Harsh as a singular source of intellectual encouragement when he arrived in Chicago from Mississippi

legendary artist Charles White, who was fourteen when the Hall Branch opened near his home on the South Side. After finding The New Negro by Alain Locke “quite accidentally” on a library visit and devouring its essays on African American art and literature, White was inspired to dig into the collection to read about great figures in Black history, including Paul Robeson, Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Booker T. Washington, and Frederick Douglass. It was at the Hall Branch that White “became aware the Negroes had a history in America,” he later recalled.

Indeed, Harsh and the Hall branch staff were committed to serving a broad public, which also included W.E.B. Du Bois, who addressed a letter to Harsh in 1936 thanking her for “the opportunity of looking at your very interesting library” and requesting that she send him a copy of her “bibliography of the Negro in Chicago.”

Throughout the 1930s, the Hall branch served as an informal clubhouse for the Chicago members of the Illinois Writers Project, a group which included Arna Bontemps, Margaret Walker, Richard Wright, and Jack Conroy. Harsh’s special collection was a crucial source for their research project on “The Negro in Illinois,” which explored the history of African Americans in the region from 1779 to 1942. In addition to reference material and workspace, the library also provided a critical source of creative and literary inspiration for members of the group. As Wright later attested, it was while working at the Hall Branch during his Writers Project years that he first discovered the work of Gertrude Stein, whose short stories became a major influence on his own.

As Harsh continued to collect rare books and historical materials on the African American experience, the Hall Branch gained a national reputation.

“Although the district which Hall branch serves is said to be from Forty-third street to Sixty-first street,” wrote a Chicago Defender columnist in 1939, “in reality it is from northern Wisconsin to southern Mississippi, because from far and near, requests are received for special lists of books, aid in preparing programs, material for lectures, etc.” Harsh was committed

during the Great Migration. “I'd sneak right up to that library because I felt very self-conscious, being from the South and assuming that everybody in Chicago knew more than I did,” he said in an oral history interview. But Harsh quickly recognized the young man as a regular visitor to the collection, and approached him with some words of encouragement. "I hope you're not self-conscious, young man, about trying to be a scholar," she told him. "Nobody should ever apologize for being a scholar.”

Another young patron was the

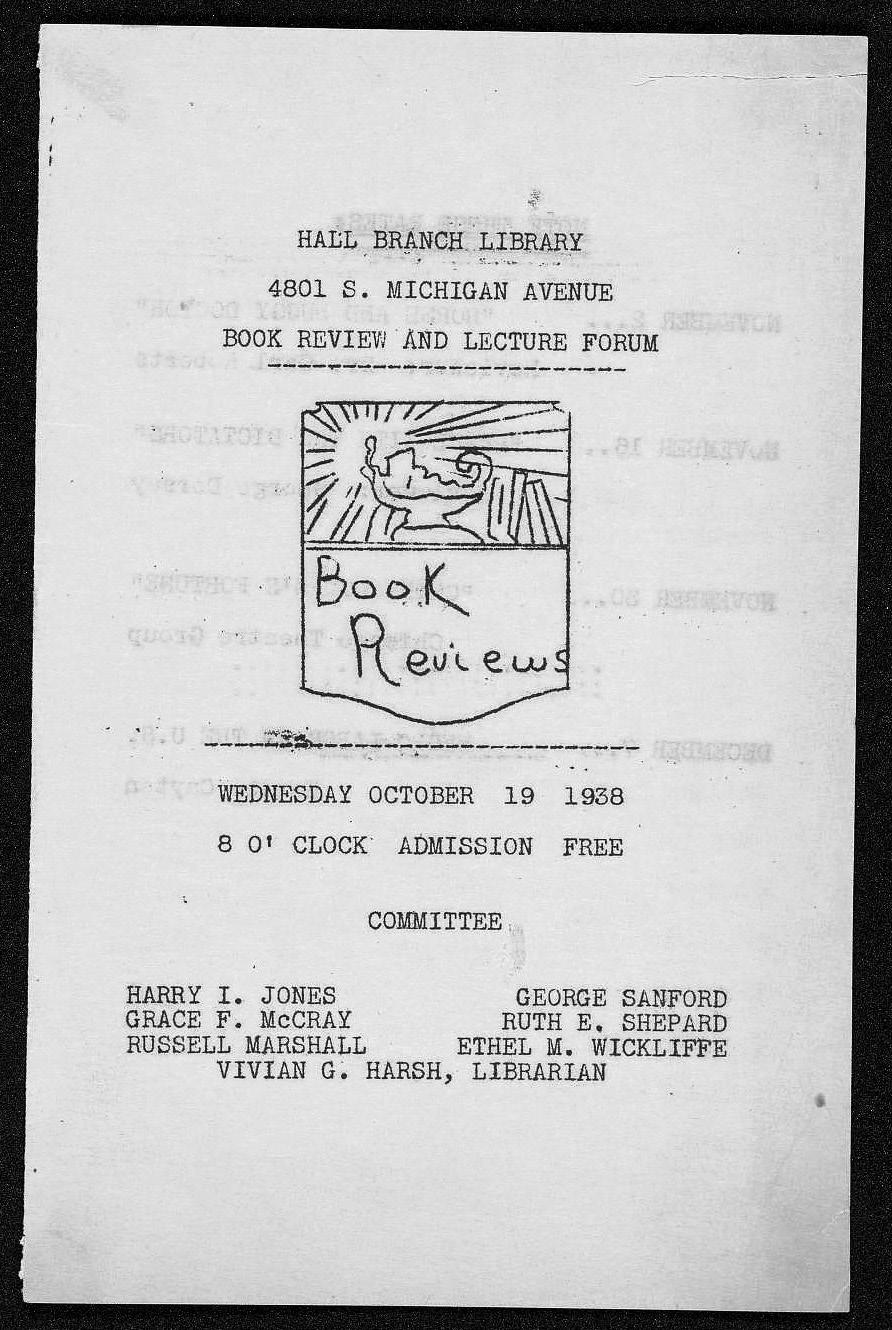

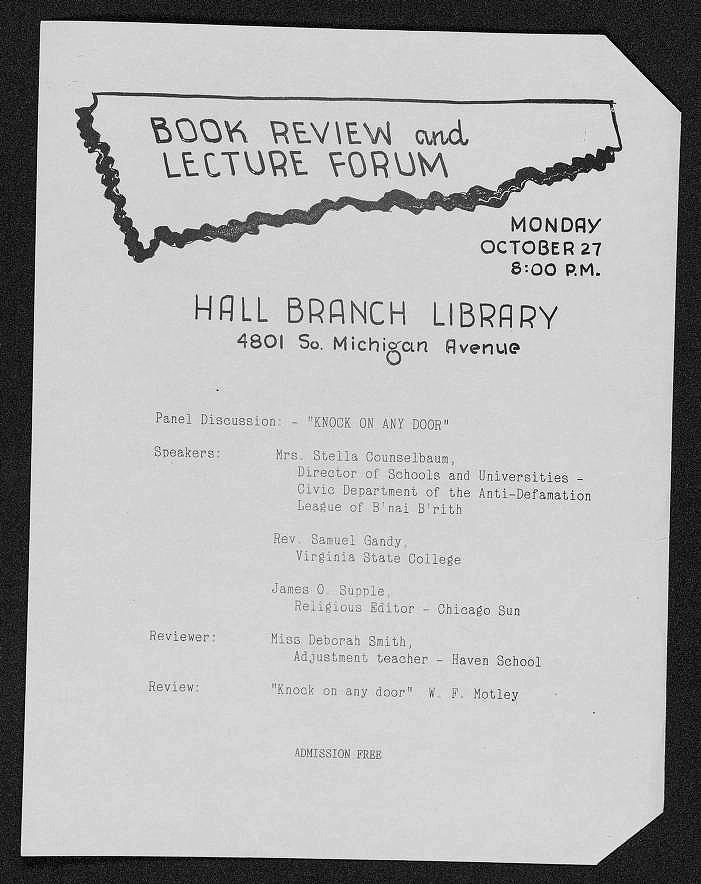

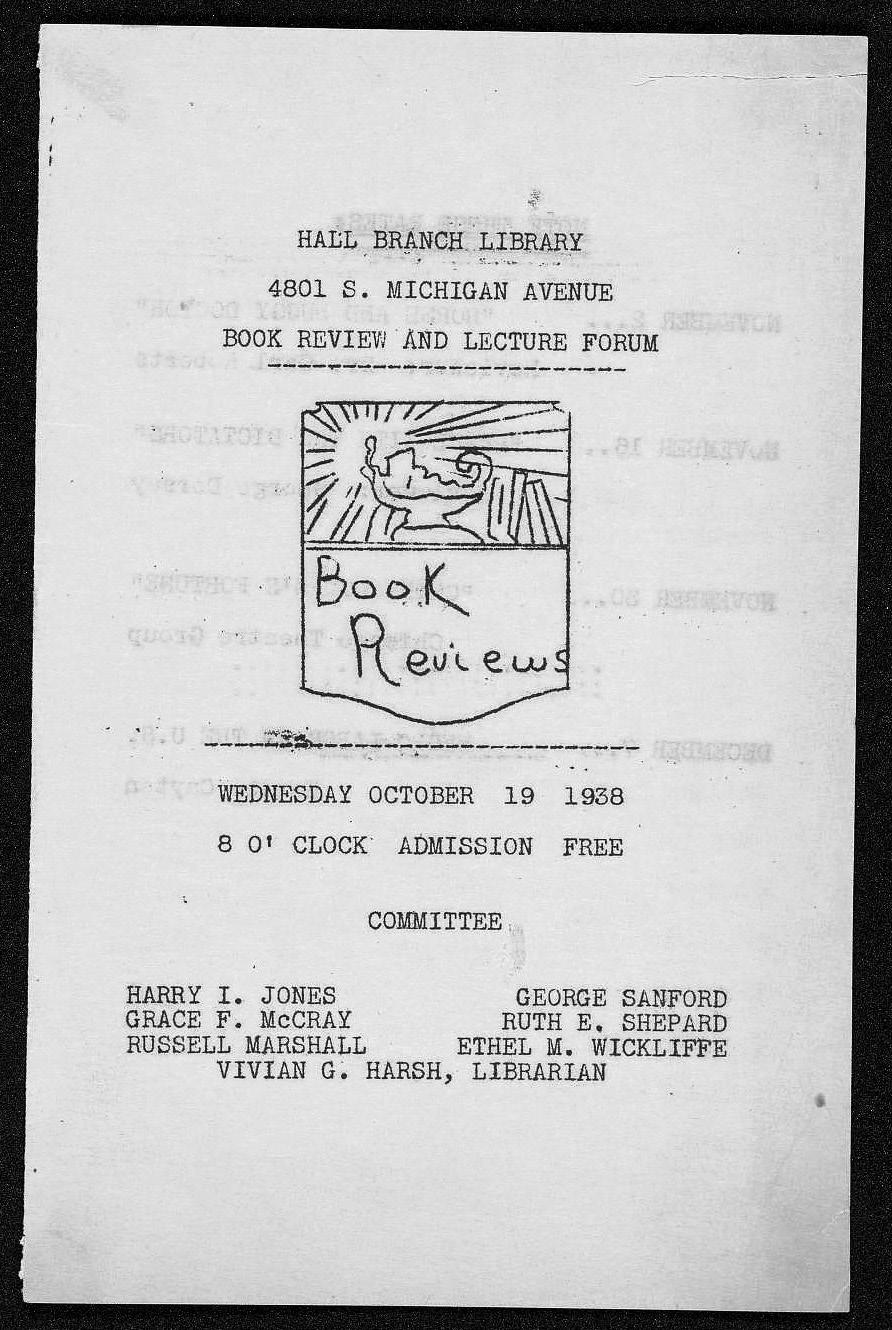

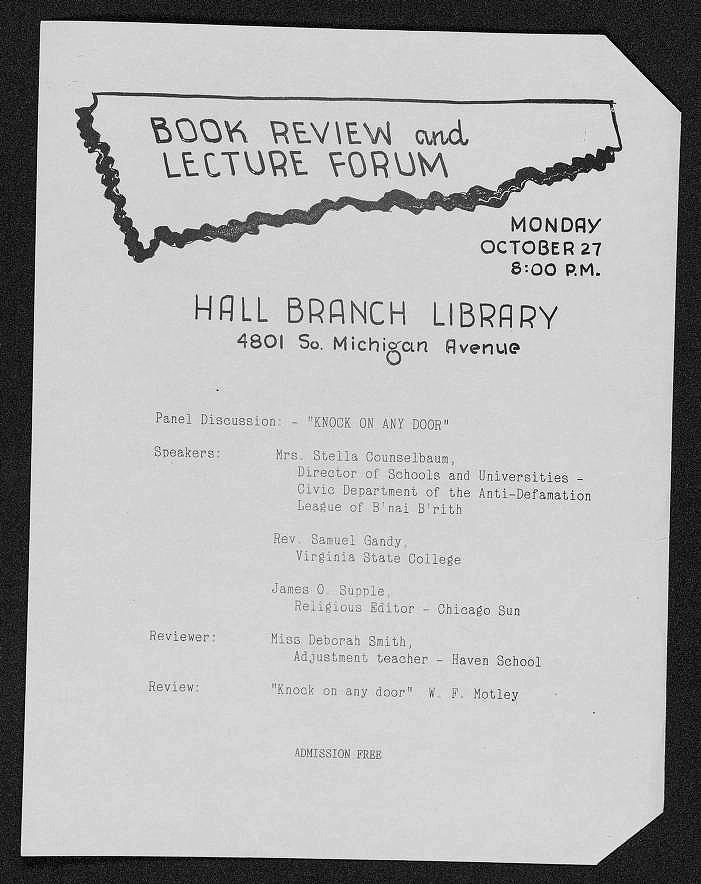

Harsh took advantage of this influx of literary luminaries by founding a semimonthly Book Review and Lecture Forum, which met at the library on Wednesday evenings from October through April. In the tradition of Chicago’s public forum movement, the forum at Hall Library offered the masses an opportunity to refine their literary tastes and join in scholarly, political, and artistic debates. Each season, a committee of library patrons and staff worked to select a list of books for members of the forum to read and review. At forum meetings, attendees packed the library, dressed in their Sunday best, to summarize, critique, and debate the books du jour.

JULY 27, 2023 ¬ SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY 9 LIT

Exacting and meticulous in her librarianship, Harsh was remembered as an enigmatic perfectionist who demanded that patrons give the library the respect it deserved.

Collage of materials from the collection, by Kayla Bickham. GEORGE CLEVELAND HALL BRANCH DIGITAL COLLECTION, CHICAGO PUBLIC LIBRARY

“This circle aims to enrich the leisure time of confirmed readers while at the same time it brings to the library others who may not be familiar with all its services,” wrote Arna Bontemps in a feature on the Hall library for the Defender. “It seeks to draw attention to books and authors which might not otherwise be discovered by every reader. Above all, it aims to develop through discussions the critical faculties of its members.”

Active participants hoped to ascend to the selection committee. Jarrett was “thrilled to be asked” because participation held an important status in the local literary community. “It meant that I was becoming somebody,” he recalled.

In addition to the Writers Project members, the Hall Library forum drew in a plethora of notable literary figures— including Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, Zora Neale Hurston, and Claude McKay—to the library to share their work. White, who was then working as a painter for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project, was an avid attendee and credited the forum as an influence on the political and historical content of his work.

In a series of forum meetings in 1938, Arna Bontemps reviewed C.L.R. James’ Black Jacobins, Margaret Walker reviewed the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay and read some of her own work, and Langston

Hughes presented on his trip to the front lines of the Spanish Civil War. In a letter to Arna Bontemps, Hughes reported on a “most delightful” meeting of the forum, in which the “Overflow crowd fill[ed] two rooms, [and] Gwendolyn Brooks [was] well received and encored to read a second poem.” Hughes later returned to the library to work on his memoir, and in his list of “Things I Like About Chicago,” he cited, “The Hall Branch Library whose Negro book collection is excellent and whose librarians are charming.”

In allowing writers the opportunity to present works in progress to an engaged community of readers, the forum served as an important institutional link between the Harlem Renaissance and the flourishing literary scene of 1930s and ’40s Bronzeville. Community life was central to Chicago’s literary and artistic movement, as Hughes observed in the Defender: “More so than in Harlem, Chicago writers tend to work and study in groups, and to listen and learn from each other through discussion and criticisms.” And while the forum was anchored by Black literary stars, it was thoroughly open to the public. As a columnist reported in the Chicago World,“The book review and lecture forum…constitutes a veritable powerhouse for the dissemination of knowledge to all who attend them, and the public is always

invited and made welcome.”

The forum was a critical node in the network of Chicago’s avant-garde cultural production, and Harsh leveraged these relationships with eminent writers to expand the Special Negro Collection. She actively solicited library patrons to donate manuscripts, ephemera, and signed copies of their work to the library. When the Illinois Writers Project was disbanded in 1942, Harsh acquired the research files of the unfinished “Negro in Illinois” project. Independent scholar Brian Dolinar edited and published the papers more than seven decades later, an example of the kind of work made possible today by Harsh’s incredible commitment to the preservation of Black sources.

Exacting and meticulous in her librarianship, Harsh is remembered as an enigmatic perfectionist who demanded that patrons give the library the respect it deserved. As erudite as she was, Harsh was committed to public education in the broadest possible sense. Her patrons included Bronzeville’s cultural and professional brokers as well as steelworkers and meatpackers, housewives, and children. In fact, the late historian, educator, and civil rights activist Timuel Black—who eventually donated his personal archive to the collection—recalled that Harsh once threw him out of the library for mocking a group of less educated patrons who had recently migrated from the South, enforcing the rights of all classes to patronize the library with dignity. Even the Book Review and Lecture Forum was radically public and attended by people of “every walk of life,” according to the Defender, which deemed it “a milestone for the Negro and Chicago.”

“With more facts, figures and information about the Negro and American history stored in her phenomenal mind and memory, Vivian Harsh died, two years after retiring from the Chicago library system,” the Defender announced. Her obituary foreshadowed the legacy of her collection: “It would not be unlikely that [at] a future date, the more than 2,000 books she gathered on the American Negro and placed in special collection at Hall branch might someday be called ‘The Harsh Collection.’ Similar to the Schomburg collection in New York’s Harlem branch library, the collection of Miss Harsh is regarded among the finest in the country.”

The collection was renamed in 1970 and was relocated to the Carter G. Woodson Regional Library five years later, where it is housed today in a facility that includes a reading room, exhibit gallery, preservation facilities, and a large bronze and brass sculpture by acclaimed African American abstract sculptor Richard Hunt.

While visiting the collection might take a bit more gumption than accessing other library services—it does require

appointments and a bit of advance planning to visit—don’t be intimidated: the Harsh Collection is open to the public, and its treasures are collectively owned by Chicagoans. ¬

Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, 9525 S. Halsted Street. (312) 745-2080, harshcollection@chipublib.org Open by appointment on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays from 10am to 5pm, and on the third and fourth Saturday of every month from 10am to 4pm.

Kit Ginzky is a Hyde Parker and a PhD candidate in history and social work at the University of Chicago. She recently wrote about the history and politics of street basketball in Chicago

10 SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY ¬ JULY 27, 2023 LIT

Flyers for the Book Review and Lecture Forum, hosted at the George Cleveland Hall Branch.

GEORGE CLEVELAND HALL BRANCH DIGITAL COLLECTION, CHICAGO PUBLIC LIBRARY

Flyers for the Book Review and Lecture Forum, hosted at the George Cleveland Hall Branch.

GEORGE CLEVELAND HALL BRANCH DIGITAL COLLECTION, CHICAGO PUBLIC LIBRARY

GEORGE CLEVELAND HALL BRANCH DIGITAL COLLECTION, CHICAGO PUBLIC LIBRARY

Community Review of Mariame Kaba’s We Do This ‘Til We Free Us

BY RUBI VALENTIN, ALYCIA KAMIL, MELISSA CASTRO ALMANDINA, CHIMA IKORO

We Do This ‘Til We Free Us is a collection of essays and interviews that explore the abolition of police and the prison industrial complex (PIC) and the power of transformative justice, written by and conducted with organizer, educator, and abolitionist Mariame Kaba.

Published in February 2021, editor Tamara K. Nopper notes in the introduction that Kaba had “declined previous requests from Haymarket Books to publish a collection of her writings,” but that “as calls for defunding the police accelerated” in the wake of the 2020 uprisings, “so did broader conversations about abolition.” In an effort to get “as many people as possible to learn more about abolition,” Kaba agreed to compile and publish the anthology.

We Do This could be said to have many authors. Several of the essays are co-written with other people, interviewers interject with their thoughts while asking Kaba to elaborate on her own, and even Kaba herself often invokes the words of fellow writers, comrades, friends, mentees, and family.

It seemed fitting, therefore, that when several writers expressed interest in reviewing We Do This for South Side Weekly, we accepted more than one perspective. In the end, we landed on four writers, each with different experiences and backgrounds, sharing what it was like to read and react to this book.

What follows is less a collective review than a collection of personal reflections on We Do This and how the book has shaped these writers’ and organizers’ lives and thinking about justice, care, and the possibilities of tomorrow.

Review by Rubi Valentin

In We Do This ‘Til We Free Us, Mariame Kaba writes time and time again, “abolition is not about your fucking feelings.” The meaning is simple: emotions shouldn’t cloud political commitments to

the basic principles of abolition, but Kaba demonstrates that it’s more difficult to do so than it seems, even for committed abolitionists.

I experienced that difficulty in my own life. Then, in my freshman year of college, my uncle was murdered in Mexico.

I saw the distress it put on my mom and two aunts living with us at the time. He was the baby in the family, nineteen years old, when it happened, only a year older than me. I felt useless at home when my mom and aunt flew to Mexico to handle the services.

When my mom came back, I learned that my uncle had been killed by another family member. That alone left permanent chills down my spine. She told me how the police in Mexico didn’t do anything to help, no arrests or investigations. If anything, they had to be paid by families to do their jobs. She said that the police were corrupt in Mexico, and I stood silent as she spoke. After what happened, I tried to talk to my family about abolition, and my mom and I would go in circles around the idea. Sometimes I was able to change a little in her thinking surrounding prisons and punishments, but in other moments she was rigid as a steel bridge. However, I didn’t want to push her and be insensitive, I always had to talk as if walking on eggshells.

In the essay “Transforming Punishment: What Is Accountability without Punishment?” Kaba and Rachel Herzing discuss users on Twitter, including self-proclaimed abolitionists, who were happy with R. Kelly’s conviction because there was finally “justice” for his history of harm and abuse of Black women. #RKellyisgoingtojailparty was trending on the site and countless tweets were excited by the news. But Kaba and Herzing write, “Let’s be clear though: advocating for someone’s imprisonment is not abolitionist. Mistaking emotional satisfaction for justice is also not abolitionist.”

JULY 27, 2023 ¬ SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY 11

LIT

Four writers share how the 2021 book has influenced their organizing and conversations with friends and family.

Kaba admits that her instinctual response to these situations is not always abolitionist. However, she continues to ground herself in her political commitment to abolition, constantly fighting our conditioning of punishment equating justice, because as she states, “they are systems that live within us, that manifest outside of us.”

I remember not too long ago at a family party, when I brought up abolition to my aunt, she asked a lot of questions I couldn’t answer. Still, she said that even if we started all over, not only would it not happen in our lifetimes, but we would recreate the same systems. And I was worried she was right. If “they are systems that live within us, that manifest outside of us,” how do we fight this?

When harm is done against someone you love and care about, more often than not, we want the person to be harmed, often in a worse way. In the case of R. Kelly and other famous abusers, people approve of their incarceration from a distance because it’s our measure of justice. Abolition invites us to interrogate our preconceived notions of justice and ask whether the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) eliminates harm from our world in its rendition of justice. As Kaba and others show, the answer is no; it just continues to cause more violence, an endless cycle.

In another chapter, “Moving Past Punishment,” an interview by Ayana Young,

policing, arrests, criminal records, prison, or cruel punishments—but this only adds fuel to the fire.

Kaba mentions potential alternatives to punishment, such as removing R. Kelly and his accomplices from their positions of power and not being able to produce any more music. Another idea is that the money from his estate, including incoming music sales and streams, be allocated among the survivors. The potential for accountability outside of prison is experimental, but endless in its possibilities.

Human nature is not absent of emotion. We are allowed to feel hurt, angry, sad, resentful, and more. Mostly, we need to grieve when harm has been done, and it must be done in community. Violence does

how we address harm. The reason I’m an abolitionist is because I know that prisons, police, and surveillance cause inordinate harm. If my focus is on ending harm, then I can’t be pro deathmaking and harmful institutions. I’m actually trying to eradicate harm, not reproduce it, not reinforce it, not maintain it. We have to realize that sometimes our feelings—and our really valid sense of wanting some form of justice for ourselves—gets in the way of actually seeking the thing we want.”

Rubi Valentin (they/she) is a recent graduate from the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) and studied Gender and Women Studies and Professional Writing. They are a first time contributor for South Side Weekly,

actions that we forget to step back and dream about what the world we’re working towards will look like. Removing the imagination from the work we do can lead us to severe levels of burnout, anguish, and ultimately feeling hopeless about whether or not we can reach that liberated world.

In the first chapter alone, which only encompasses four pages, we’re being challenged to reanalyze our understanding of crime versus harm, the ways we as individuals can be complicit in the perpetuation of harmful ideologies onto other community members, practices we can engage in to lessen contact with the carceral state, breaking down the many ways the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) is thrust into our everyday lives, and most importantly, being open to change by answering that very important question, “What can we imagine for ourselves and the world?”

Young states how it feels irresponsible to apply a personal quest for justice to a society as the standard, and then asks, “so where is the balance between having policy and response that is both less personal but is still informed by survivors?” In policy, the response to harm is more harm, either with

not heal wounds or the pain in our hearts, only lets them fester and blister until the hurt consumes our entire body. Wanting to hurt another because we were hurt is falling into these systems of violence. “Vengeance is a lazy form of grief,” Kaba wrote, a line I remember vividly because as much as we wouldn’t want to admit it, it is.

This chapter made me think about my uncle and what would be justice for him and for my family that doesn’t include the PIC, but I’m not sure yet. I know if I ever tell my mom about these ideas, she might get upset. I’m not going to tell my family what they should feel because we’re allowed to feel all of our emotions. One day, I’ll slowly introduce these abolitionist ideas to my family, I just don’t want them to feel like I’m trying to force them into anything.

We Do This ‘Til We Free Us doesn’t have all the answers, but it was a good start for me to think, learn, and reflect on what it means to be an abolitionist.

My practice and thinking is grounded by this section from Kaba:

“As an abolitionist, what I care about are two things: relationship and

and is currently an editor and writer for Bonfire News

Review

by

Alycia Kamil

Ipicked up this book in low spirits from the hardships that transpired in the summer of 2020. After an exhausting past three months of seeing so many of my friends, myself included, being harmed by the systems we were fighting against, stepping away from the frontlines was painfully needed. I turned to what initially brought me into these spaces—literature. I was familiar with abolitionist concepts like transformative justice and the carceral state, and thought this book could help add more language to my organizing vocabulary.

Within two pages of the first chapter, I was prompted to reflect on something I haven’t been asked to in years: “Let’s begin our abolitionist journey not with the question ‘What do we have now, and how can we make it better?’ Instead, let’s ask ‘What can we imagine for ourselves and the world?’” As organizers, we spend so much time on the logistics of planned

The question has weighed on my heart in the years since first reading the book, and especially as it relates to themes throughout the book: imagining and experimenting with strategies of community care instead of depending on punitive systems to do things that they weren’t created to do; and viewing hope as a discipline to be practiced while engaging in our fight for liberation.

We Do This ‘Til We Free Us calls attention to the generational trauma marginalized communities have experienced at the hands of the state and the cycles that continuously repeat when the majority relies on the same systems that evoke massive waves of harm in the first place. Through Kaba’s research, onthe-ground experience, and narratives from those she’s in community with, readers are shown the domino line of disappointments that the PIC and its many offspring project onto Black and Brown individuals. These sections may be eye-opening for those who believe there has to be at least some aspects of the system that are worth preserving.

In Part 3’s “We Want More Justice for Breonna Taylor than the System That Killed Her Can Deliver,” Kaba writes about the slippery slope that comes with trying to find the silver lining of the justice system after the conviction of a police officer. Arresting one cop will not eliminate the embedded systemic policies that allowed for the death of Breonna Taylor to occur. Thinking an arrest is a solution to that problem only works to validate the same

12 SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY ¬ JULY 27, 2023

LIT

“Let’s begin our abolitionist journey not with the question ‘What do we have now, and how can we make it better?’ Instead, let’s ask ‘What can we imagine for ourselves and the world?’”

ILLUSTRATION BY JULIE MERRELL

system we’re trying to move away from. In her analysis, Kaba is pushing readers to see for every one occurrence where the justice system provides a sense of “justice,” there will be hundreds of other cases where there will be injustice. Why bite on our fingernails awaiting an outcome we’ve rarely been shown when we can do the work intra-communally to see what real justice, investment, and compassion look like?

Until we truly push ourselves away from the dependency of harmful structures, we’ll be forced to see different faces relapse into the same heart-wrenching stories community members and freedom fighters have been fighting against for centuries. These systems don’t guarantee us safety, at any point we could fall prey to the mosh pit of identities in which the carceral system shows up. Just because we step away from a punitive frame doesn’t mean we aren’t working toward accountability. As Kaba states, “We want to direct our energies toward collective strategies that are more likely to be successful in delivering healing and transformation and to prevent future harms.”

Hosting grieving circles, food pantries, mutual aid services, educational workshops, and creating spaces where these tough conversations can happen are just some of the strategies we can use toward those aims. In the process, we can come to see the power that lies within spaces that are led by community for fostering community power.

“I believe ultimately that we’re going to win, because I believe there are more people who want justice, real justice, than there are those who are working against that,” writes Kaba, an expression of her journey in developing hope as a practice.

It’s a rollercoaster ride doing organizing work and often you find yourself becoming quite cynical after experiencing so much loss and grief. It’s easy to put yourself on autopilot, floating by in a constant loop of actions, vigils, and City Hall meetings. It’s a routine where if you don’t find something to keep you grounded, you begin to lose yourself in it.

Being hopeless in work that requires you to create a future world where these problems don’t arise as often seems counterproductive. Hope doesn’t erase feelings of disappointment or frustration, and it doesn’t only encompass moments of joy. It’s the willingness to continue doing the work regardless of what the outcome may look like. It’s moving forward knowing a change will come either way, and you’re still working towards the end goal no matter what direction the circumstance may blow you in. It’s knowing the work doesn’t start nor end with you—we’re simply marking our particular spot of the movement timeline by laying down a foundation for those after us to follow. It’s a lifelong practice that will exist as a hovering presence while battling a tough fight.

Alycia Kamil is a multi-disciplinary artist and educator from the south side of Chicago.

Review by Melissa Castro Almandina

Ididn’t have the words for it. I grew up with abolitionists and organized as a teenager in revolutionary collectives, read zines and distros, and attended community abolitionist trainings, workshops at the Allied Media Conference, community meals and community political education readings. I learned abolitionist politics by living through the world created by the most caring individuals who dared to see a world where we aren’t disposable.

My commitment to abolitionism solidified when I was arrested and cops swarmed me on the ground and handcuffed me, and later when they starved me. It solidified through the money I lost just to get forced to take a plea deal and lose my most precious commodity—my time— and then pay the state $50 a month for over a year of probation. I was lucky to be around family, around community, and with an abolitionist politics that kept me grounded as the terror of the state was unleashed upon me.

Mariame Kaba’s We Do This ‘Til We Free Us gave me the words and guidelines of imagining a life where our relationships to others were the most valuable asset we have against a common enemy; a world where there is this understanding that while we are all capable of harm, we are deserving of the dignity to change; a world where there is no carceral state, where there is only us reaching for one another.

This book was a going back to basics, the perfecting of a tendu, the instructions on how-to-unfurl and strengthen my toes to create a strong base and form a solid view of the world through previously read abolitionist texts, through my lived experiences of seeing how the police terrorized my community and terrorized me. It served as the first formal text of how to maintain accountability in an actual abolitionist and taut way.

The book challenges the reader to envision a world where we are to politically uphold abolitionist principles and have designated safe spaces where it is normalized to address harms in ways that involve the community. These should be spaces where we solve problems collectively, don’t shame one another, work with both the survivors and abusers, and where we’re not separating families as the PIC does or working with the police as the NPIC does, but collectively figuring out how we can mutually get our needs and our need for safety met.

We deserve safe spaces within our communities where we make mistakes— and yes, where we address harm, because all have the capacity to cause harm. Throughout the book, this notion that none of us are exempt from that held me and gave me hope that the sooner we all realize this, the sooner we can be better with one another and the sooner we can be on our way to building a better future.

That’s how Nebula, the mutual aid organization I’m part of, was born, as a gaseous nursery full of pulsating brilliance and possibilities. It happened while I was tenant organizing. I, along with other organizers, realized that we weren't only dealing with landlords, illegal lockouts, and the rampant inequities caused by the COVID-19 pandemic—we were also dealing with domestic violence within these family units.

We decided to create this space that wishes to collectively identify and attempt

to address the root causes of harm within the community. We don’t have the answers, but we are trying to build and inspire others to build similar organizations grounded in mutual aid in their communities. We want others to build more organizations that value community cooperation, selfdetermination, healing, rehabilitation, and dignity.

Having a neighbor being harassed by the police can put the entire community in danger. What is the alternative? Nebula, along with the input of the community, are attempting to figure that out. We, at Nebula, are learning as we go, through lived experiences, being on-the-ground, listening to our neighbors, making art and being in community with families in crisis—collectively figuring out what needs are what it means to operate from a revolutionary love ethic.

Some of us come from the background of working directly with men who have caused harm, some of us are yoga instructors and some of us are artists and art educators that use what we’ve learned in our fields to make art in community, to express, to dance, to make beautiful things—because we have the right to heal. We make time in our lives for building and organizing because our collective liberation is of utmost importance, and as Kaba puts it, “My conviction is that we ought to be organizing steadily always. All of the time. When the protests and the uprisings happen we can meet those moments, because we’ve actually been building all along.”

It can be very isolating when going through trauma, so it’s integral to have a community around who are calm, who are compassionate and who can welcome you to your new life. A lot of us in Nebula are former survivors and former non-profit workers who understand the role that NPIC has with PIC and we have seen how this affected those people who didn't follow the perfect victim narrative, who are criminalized, and who don’t have the resources needed to receive the help they deserve. They fell through the cracks. As we collectively envision and build that new world, we want to be ready.

In the book, Kaba writes about how her father, who is not only an important organizer in his own right but also her influence, encourages her to solve issues with one another and reminds her, “You

JULY 27, 2023 ¬ SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY 13 LIT

ILLUSTRATION BY JULIE MERRELL

are interconnected to everyone, because the world doesn’t work without everyone. You may think that you’re alone, but you’re never actually alone.”

Moving with dignity and working through conflict while maintaining our relationships through struggle is a seed that Nebula attempts to embed in the anti domestic violence work we do. At this time, Nebula is still in its seed stages and is at capacity. We are currently helping six families and could really use the support to grow and build our organization to add more members.

The new world is possible, it is here, and it exists, we are it, we’re all we got, and with all the love in the world, I encourage you to build mutual aid organization, talk to your neighbors, your friends, and build stronger communities now, because we will win, we will win, we will win.

Melissa Castro Almandina is an anarchist, poet, & resident artist at AMFM gallery. They write poetry, make zines, & dance ballet in their spare time. Find their work online, in zines, & in The Breakbeat Poets Vol. 4: LatiNext.

Review by Chima Ikoro

It was easy for many of us to agree we didn’t like the police before we ever had the language to describe why. We saw law enforcement jammed into every crevice of our lives, creating more problems than solutions.

Many young Black and Brown folks from disenfranchised neighborhoods interact with the police for the first time early on. Whether directly, by being adultified on the street or ordered around at school, or indirectly, by seeing an adult in their life harassed during a traffic stop.

For a lot of my life, I lived at the edge of the city in a neighborhood called Beverly Woods. Here, I was part of Beverly enough to have close friends whose parents were cops, and close enough to walk to the houses of friends who those police officers did not want their children hanging out with.

My dad always preferred I hang out with kids whose parents were cops, assuming that he knew he could trust them. But why? He was afraid of the police; he tells stories of cops stopping him and roughing him up, knowing that

ILLUSTRATION BY JULIE MERRELL

he could not do anything because he’d recently immigrated.

He saw cops everywhere in South Shore, where we originally lived, and folks still got their cars and homes broken into. He’d never described one positive experience with a police officer, and yet always mentioned that badge when talking about my friend's parents.

Part of me believes it was because they

without the full scope of what abolition really is, people may not know they align with these ideas.

My father, like many others, does not want to defund the police despite never being helped by them. Being harmed by cops has not stopped him from thinking that there needs to be more police. This is probably because he’s also been robbed and harassed by people who look like him, so the idea of fewer police means more chances for his safety to be at risk.

That’s not what abolition is. The abolitionist framework looks to remedy the circumstances that would make a young man hold a cab driver at gunpoint in the first place—poverty, unresolved mental health issues, housing insecurity, etc.

Food and a safe place to live can stop more crime than an officer ever could considering that police show up as a response; there’s no way for them to get ahead and determine when something is going to happen before it does. Black and Brown people in marginalized communities know this already, they’ve

conflict resolution tactics, for example, can be the difference between life and death.

In this same section, Kaba goes on to write “...only building power among those most marginalized in society holds the possibility of radical transformation.” So by that logic, the “work” and its ideologies must be made accessible to the most marginalized.

When asked where to start on the journey to understanding abolition, justice, and liberation, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us has taken its place at the top of my list since being published. The usage of concrete examples, whether they’re providing factual evidence or detailing a personal experience, give context that allow the reader to relate their own understandings and experiences. And that’s what makes abolition tangible; folks being able to understand how it directly affects them and their communities, and why they should care about how it affects everyone else.

Literature that is as transparent and comprehensive as We Do This ‘Til We Free Us becomes a guide for individuals who have been doing the work to continually transform their thinking, and grow as well. For example, Kaba implores readers to challenge the idea that indicting police officers is a viable solution.

“Beyond strategic assessments of what is most likely to bring justice, ultimately we must choose to support collective responses that align with our values,” Kaba wrote.

were Black; this created a separation in my mind as well at the time. But I started to form my own resentment toward them as adults because of the language they used to describe my peers just because they lived on the other side of the tracks.

Abolition is about more than just a disdain for policing. It compels us to understand how many of the traps designed to cage Black and Brown folks revolve around the construct of policing.

Abolitionist writing like We Do This ‘Til We Free Us is vital because, despite our desire to create a better world, the language of these movements is yet another barrier for reaching the people who would benefit from them the most. It’s hard to imagine that words like “defund” are jargon, but

probably seen it with their eyes, but they might not make the connection.

“Defund the police” is an abolitionist demand not only because that is where the money for these other services will need to come from, but because the police are actively harmful. In section three, ‘The State Can’t Give Us Transformative Justice,’ Mariame Kaba explains that she never calls the cops. “It takes practice to do this,” she wrote. “As such, we need popular education within our communities about alternatives to policing.”

Some people would agree that the police are not helpful, but without knowing what else to do, they might still resort to calling them. Educational materials and books that teach community members