This chapter of Sparks Magazine has come together to acknowledge the Asian-American Hate that persists after the impactful Stop AAPI Hate movement in 2021. Additionally, we also applaud the commendable APIA inclusivity and representation at the University of South Florida Campus.

In the past two years, racially motivated violence against Asian Americans— including the March 2021 Atlanta spa shootings that killed eight Americans, among them six women of Asian descent—has added urgency to efforts to protect their health and safety after the COVID-19 pandemic. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has documented a 77 percent increase from 2019 to 2020 in hate crimes against Asian people living in the US. The vast majority of Asian Americans (82 percent) agree that, as a group, Asian Americans have faced discrimination as a result of the coronavirus pandemic in this country. We call upon USF to continue to make our campus a safer space for young Asian-Americans to express themselves freely and without judgement.

As USF continues to make a inclusive space for Asian-Americans, the past year has also seen great developments in the student leadership. For instance, we are proud to have our first Asian-American Student Body President and Vice-President, in the history of USF. This serves as a great example for students at USF and beyond, that we can achieve our dreams with passion, determination, and grit. Moreover, there are more than 20 student organizations that celebrate our Asian culture and gather occasionally (Annual Journey to the East) to show our solidarity. USF is a diverse university that promotes all kinds of cultures and ethnicities and we request them to keep doing so.

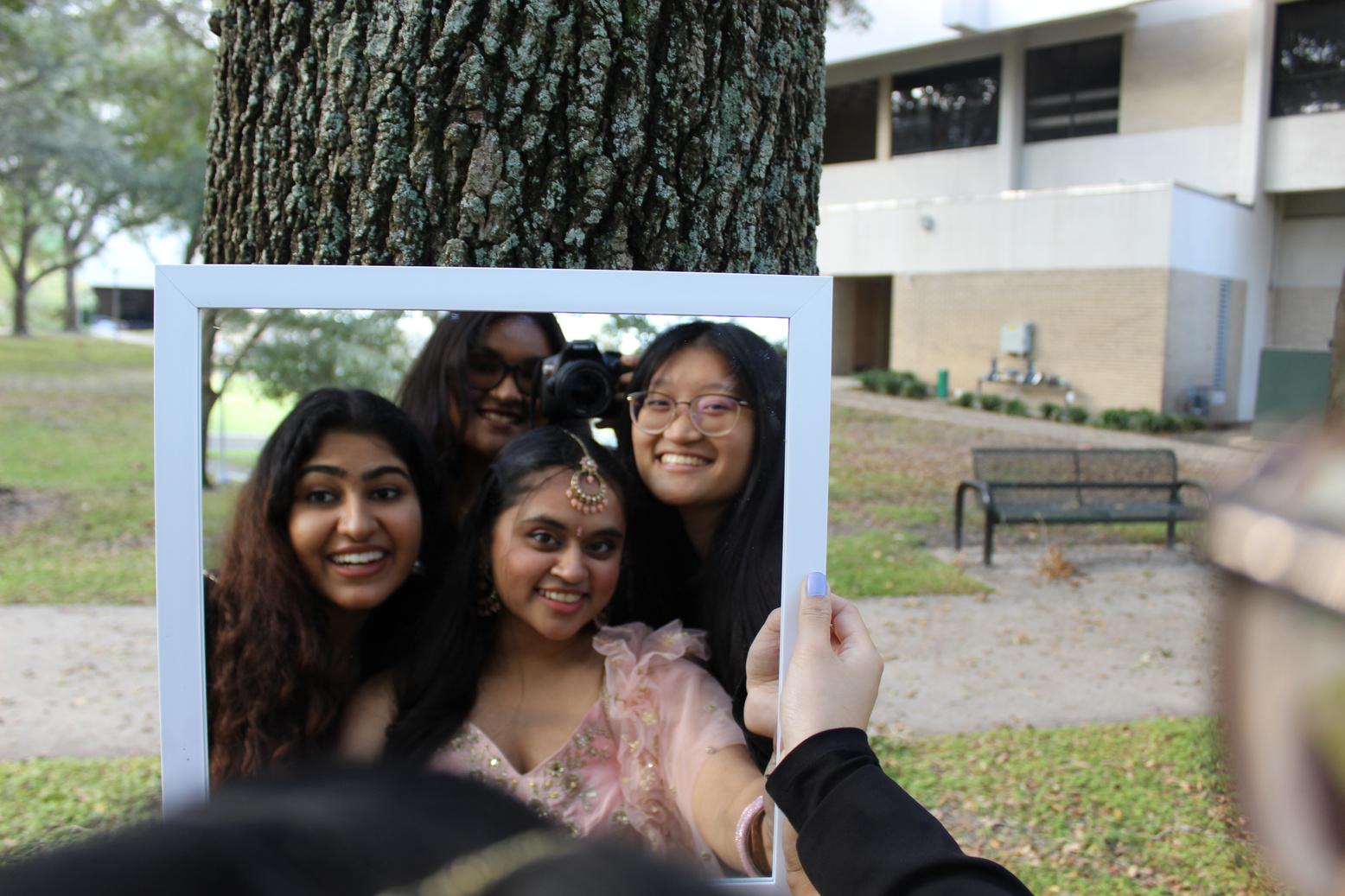

In spirit of showing solidarity among Asian organizations on USF campus, the Hindu Students Council at USF is collaborating and co-sponsoring with the USF Chapter of Sparks Magazine to further spread awareness of Asian American advocacy and representation.

Dear Reader,

Whatever your reason is to open this issue of our beloved Sparks Magazine, I am glad you are here.

One of my writers on this issue, so eloquently said , “How do I know what I want, if I don’t even know what’s missing?” That is exactly how I felt prior to joining the Sparks family. After two years of writing and planning for Sparks, I can say with utmost confidence that I might not know what I want, but I know what I need. What we all need. And that is a safe space to bare our shared cultural experiences, beliefs, and future developments. A space to be naked with our truths and transparent with our identity. Asian? American? No, Asian-American. Yin and yang both.

Being the first first international student elected to be Editor-in-Chief for this year, I might not have grown up with the same experiences that you did. Regardless, I have endured the same feelings of conflict, confusion, and chaos that

the love, community, and cultural closeness, the same as all of you. We have grown up watching aspects of ourselves, our families, and our culture that we would love to rewrite. Here is your chance. In the pages of this issue, you will find yourself affirming your doubts. You will be amused at facts you didn’t even realize. You will be stupefied at how diverse, deep, and dear our identities are. All in all, now is the moment to stand up for yourself, your culture, and your identity. It will be a failure on my part if I, along with all the hard working members of my team in this issue, cannot make you prouder of who you were, are, and will always be.

It is also my first time being Editor and I could not have done it without my backbone- my writers, designers, photographers, and members. Your perseverance to embrace your creativity and share it with the world, is nothing short of epic. Thank you to my E-Board for supporting me through the thicks and thins. Thank you to all my members for giving me more love and acceptance than I probably deserve. As a leader, I may have made mis takes but being your Editor-in-Chief has been the greatest learning opportunity of my life. All the love to my team of talented individuals who help me hold the torch of Sparks’s legacy high.

So, dear readers, immerse yourself in these pages to understand who we are. To understand who you are. Continue expressing yourself in whatever creative means you choose and help me carry Sparks forwards with passion and respect. I hope you always believe in our Representation. Be an advocate whenever needed and Make a statement. Not just for you, but the whole Asian-American community around you. Be Epic.

Wishing you years of creative freedom,

Sanikaa Thakurdesai, Editor-in-Chief

Sanikaa Thakurdesai, Editor-in-Chief

Watching Mahabharta on Sat urday and Sunday nights was a routine I fell into in middle school. Every weekend I would be gasping at Duryodhan and Shakuni’s evil plans, fangirling over Draupadi, and gushing over all of the exquisite outfits, wish ing I could be part of the cast just to wear the costumes. But most importantly, ev ery weekend I fell more and more in love with my culture: the bold and glittering fashion, the simple yet ground breaking philosophies on life, and the dulcet melody of my mother tongue- a melody so rare, I coveted the few times I could listen to it. Watching these Indi an epics on the screen instilled a strong sense of pride in my culture, a pride I needed to nur ture while growing up in the West.

The Mahabharta and the Ramaya ma are two Sanskrit epics set in ancient India amidst gods, demi gods, and demons with plot twists on a Game of Thrones level. The Mahabharata, which is set in an cient India around 5,000 years ago, demonstrates a story revolving around two sides of a family- the Pandavas and the Kauravas, and the cousins’ fight for the succes sion of the throne of Hastinapur. The narrative is rife with political intrigue, betrayal, battles, and phil

osophical discourses on morality and free will. Its sister epic is the Ramayama- a “love story” set in India 7,000 years ago, where King Rama sets on a journey to rescue

the ancient Kurukshetra War from Mahabharata have been found, while a stone bridge that Rama built in the Ramayama has been found underwater off the coast of Sri Lanka. But whether it be on TV or in books, modern retellings of these epics help individuals con nect with their culture, just as I did.

Recently, I’ve begun reading Kaikeyi by Vaishnavi Patel, and to my de light, it is a book that has bridged

the gap between my love of read ing and the Indian epics I grew up watching. Kaikeyi is a book regard ing a female villain in the Ramaya ma, Queen Kaikeyi, and delves into her childhood and the motivations behind her banishing Prince Rama. While male villains usually have an end goal with a twist ed morality, female villains are almost always manipulative and vindictive, spurred on by jealousy and other “weak womanly emotions.” In this nov el, Patel has Kaikeyi step away from the evil stepmother trope and fleshes her out. She was not just an evil stepmother but a woman cheated out of a deal, a mother who wanted the best for her son, a queen who lawfully protected her female citizens, and a mother-in-law who tried her best to pro tect her daughter-inlaw from her husband, Rama. Still, I was elated to see an Indian mythology inspired book in the top books of 2022, especially since the mythology section in the publishing world is primarily recy cled with Greek mythology retell ings, of Hades and Persephone or Helen of Troy.

But in the broader scope of both cinema and publishing, there has been a resurgence of femi nist retellings of well-known stories. For instance, Disney sympathizing with Maleficent

Written By Serena Bhaskar Design By Amreen Naveenand her tragic backstory or Made line Miller taking a deep dive into Circe, Greek mythology’s most in famous witch. This slight shift of perspective in mainstream media takes back the female narrative of these misunderstood mythologi cal women. It fleshes them out as characters of their own destinies, not simply another love interest or temptress to the hero of the jour ney. Joseph Campbell, the creator of said Hero’s Journey, states that “in the masculine dream world… the excellence of the female.. reside[s] in her beauty, her constancy and re spect for the marriage bed and her ability to inspire excellent males to excellent patriarchal deeds.” Wom en have limited characterizations in mythology- their character role must be tied to a man. It is law that in order for a man to prove himself as a hero, at some point, a woman must be placed in danger and saved for the sole purpose of furthering his characterization as a virtuous man. Such is the case with women in mythologies all

her husband rescues her. No, due to societal standards of having a “pure wife,” she has to prove her chastity to Rama after being ab ducted through a test of fire. She eventually goes into exile as her possibly sullied reputation harms Rama’s image as King and raises their two sons alone. When Rama comes back to retrieve their sons and offers her to return after a second chastity test, she refuses to endure further humiliation and goes into the earth, into the arms of her mother, the earth goddess. Surprisingly, even after the amount of humiliation and grief her hus band caused her, in India, Rama is considered one of India’s greatest heroes, and Sita is considered the most ideal woman and wife out of all the epics because of her devo tion to her husband. This glorifica tion of a supportive, obedient wife can be extremely dangerous for young girls and can lead to silence in the face of domestic abuse or increase female violence such as honor killings.

stand up for herself in a courtroom full of men. Men such as her hus band, who gambled her away as

a piece of property, her cousin-inlaw, who attempted to disrobe her publicly, and her other elder male relatives who did not intervene and just watched. And yet, similar to the harmful idolization of Rama, Yudisthir, Draupadi’s husband is considered the most righteous man of dharma.

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, a pop ular Indian author, has specifically rewritten the two epics from the perspective of Sita and Draupadi, correcting the popular misconcep tions about the heroines- the for mer “as meek and voiceless” and the latter as “uninhibited and ar rogant.” Though mythologies may not be wholly real, mythological literature is a reflection of life and

By rewriting these epics through the lens of feminine power, writers such as Vaishnavi Patel and Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, single-hand edly expand literature around In dian mythology and overturn the outdated male model for hero ism. They instead provide young er generations with strong female role models and leaders that have been sidelined or disregarded all throughout history. The female voice has been drowned out for far too long, so make sure to listen for her wherever you

As attendance is taken on my first day of classes, I sense a slight sigh or fumble, and I know right away that the teacher has reached my name. I say “here” as they say the first letter before they even attempt to enunciate my name.

What is your name? One of the sim plest questions someone would ask, but the one I find most difficult to answer. I wonder if I should pro nounce my name with an Indian accent or Americanize it for clarity. Even then I am embarrassed to cor rect my name when pronounced incorrectly. Being stuck as a mi nority as an Indian American, I can feel myself split into two as I step out more into social environments.

This confusing duality of cultures started due to my inability to em brace my Indian culture since I nev er grew up in India near my relatives and my heritage. Having wonder ful parents and friends made up for that and has really helped me stay in touch with my Indian heri tage. But sometimes, this duality can be confusing. What language do I speak with my parents when my friends are here? What food do I bring to school? What music should I play in the car? These may seem like simple questions but they affected

I viewed myself. First-generation Indian Americans who attempt to integrate both cultures into their life frequently experience identity crises as a result of this. This influ ences the way people view them selves and the groups they identify with. The values and attitudes that are common at home and in the local community have an impact on how a person develops their perception of their own. It’s almost like a tug of war - to family you may seem too American but to friends or peers, you may seem too Indian. By our own definitions, we are all unique and we embrace the con trast between Indian and American cultures while cultivating respect for both.

ABCD is a phrase frequently used to describe this identity confusion. This is an acronym that stands for American-Born Confused Desi. A label applied to Indians raised in America and who adopted the cul ture. ABCD encapsulates the idea of cultural acceptance and under standing as it encompasses the idea of assimilation into the two societies. An identity crisis is a de velopmental occurrence in which a person starts to doubt who they are or where they fit in the world. It is a global phenomenon experi enced not only by Indian Ameri cans but by many young adults. Personally, it makes me feel like I am an outsider most of the time. Although I was born here, due to my Indian back ground, I don’t consider my self truly an “American”.

This only escalates during interactions regarding my identity. When someone asks me “where are you

from?”, saying that I am from Flor ida does not satisfy them. Instead, they want to know about my race and ethnicity and not where I grew up. Likewise, I am regarded as a foreigner when I travel to India. My appearance and the accent I have when I speak my language are inconsistent and unalike to their ears.

Embracing and learning about one’s culture is very cardinal even though there are many obstacles that exist. As I grew older, the im portance of studying my mother tongue: Telugu is something I be came more aware of. It enables me to speak with my family and connects my life in America to my ancestral roots in India. However, No matter the case, there are still many times in India when I speak Telugu and they often laugh. They tend to mock my accent and my lifestyle instead of trying to ap preciate that I am in touch with my roots and my upbringing. Even though I was brought up in Ameri ca, not India.

To be honest, I still don’t always know where I actually fit in. I real ized that no one can entirely elim inate a part of their identity, since that would not portray who I truly am. I found my place, as I started appreciating myself and both of my identities. My childhood has undoubtedly been influenced by American culture, but my Indian background has not been over looked. I’m proud of my dual iden tities and the fact that I had the chance to grow up in two different cultures. It has taken me a long time to mature to recognize that my two worlds can coexist as one rather than having to be distinct.

Written By Vaishnavi Yelchur Design By Amreen Naveen

The word “melting pot” often reminds people of the United States of America, but Vietnam, where I was born and raised, is a surprisingly diverse place. 54 ethnic groups with unique cultures and languages share the beautiful S-shaped land.

I belong to the Kinh people, the predominant ethnic group in Vietnam, which constitutes approximately 85% of the population. Unsurprisingly, this ethnic group accounts for the majority in the government body and is the representative voice in the press, TV and other multimedia channels.

“Ethnic minorities are losing their identity to the invasion of popular culture”. “The government introduced policies to bring more minority groups to governing entities”. “Are we misrepresenting ethnic minorities due to our ignorance of their cultural perspectives?”

I grew up hearing these phrases thrown around almost everyday on media outlets with total oblivion. Ethnic minorities, in my mind, were none of my business.

Until I went to the U.S. as an international student and suddenly, involuntarily, belonged to an ethnic minority. My priorities and privileges as the overwhelming majority got rid of all of a sudden. My day-to-day conver sations all switched to English, a language I was not entirely familiar with throughout my childhood. I have to survive all on my own without the guidance and protection of my family. Without this support system, I had to build things from the ground up, constructing relationships and navigating my way around, all on my own. The fact that I live in an educational and social system that is built for a predominantly white population is overwhelming. The cultural differences and language barriers sometimes become a huge problem in my daily life, to which people around me cannot relate.

It is with this experience that news and policies regarding racial and ethnic equality started to grab my at tention. My personal perception of social issues would otherwise not have been challenged if I were only in America. Throwing yourself into a world of hostility and shaking off your prevailing identity could change your thoughts and convince you otherwise about beliefs that you might have assumed as the truth.

I belong to an ethnic minority. Tough as it can be at times, it is a life-changing experience.

by Quyen Tran design/ Dan Pham“AND I AM PROUD TO BE ASIAN, AN ETHNIC MINORITY, AN ASTRONAUT EXPLORING THE VAST REALMS OF THE GALAXY.”

A feeling I started feeling since I stepped foot in America but has always felt too guilty to admit is the inexplicable feeling of shame about being Asian. The inability to speak my mind because of the language barrier. The silly mistakes I make in my everyday life due to cultural differences. My unique skin tone, facial features, and physical appearance. This desire to fit into the American society and just to be one of them was often so deep that I used to dearly wish I could change the world around me.

I used to blame people for treating me differently, for asking me questions like “Which part of China are you from?”, associating every Asian possible as Chinese, or “Is Vietnam still plunged in war?”, uncannily holding the belief that the Vietnam War is still plaguing my people. Their limited and rigid assumptions about my rich culture made me the more hesitant to bring my ethnicity to the conversation.

I thought the only way out was for the whole world to change, until time passed by and I reflected deeply on my complex feelings. I came to the realization that it was not the world, it was me that needed a change. Hesitant as I was to face the truth, it was my identity I was doubtful about. I brought it upon myself to change my outfit style, to hide my more Asian lifestyle and beliefs and to refuse to speak about my roots as an Asian to look and feel more American in a predominantly white society.

And so I changed. This came in the form of learning to have a deeper understanding of myself as a Viet namese person currently living in America and proudly introducing my unique culture to American friends through the arts of writing to spread knowledge about my home, Vietnam. Embracing my culture by engag ing more with it and sharing about it with my Vietnamese and American friends will help me cultivate knowl edge regarding how I can put it to use and make a good sense of it in the context of conflicting sets of belief dominant in American culture.

I cannot change the world, but I can change the world in me.

It is magical to think how I am just a small speck of dust in this gigantic universe, but I am also the brave astronaut traversing the vast galaxy. I collect the stars of hopes and dreams and explore dark and deep des tinations of the world throughout my adventures. Tears shed in times of hardships and uncertainties crystal ize into beautiful stars in the sky, shining the light to even more victorious and meaningful explorations of the universe inside me.

In America, I discover not only the world around me but the deepest parts I did not know exist inside me. Going from an ethnic majority to minori ty, I was taught the sense of compassion and empathy lacking in myself. Rather than remaining ignorant of the needs for promot ing diversity and inclusivity in policymaking, I have become an advocate myself and developed huge interests in this area in my day-to-day life. Instead of feeling sour about certain individuals’ disregard for my own culture and identity, I use the writing skills cultivated over the years to publish works in magazines and newspapers to spread aware ness and empower those in my community.

And I am proud to be Asian, an ethnic minority, an astro naut exploring the vast realms of the galaxy.

mmm…sometimes I feel like life would be so much easier if I just inherited the “Y” chromosome.” Growing up as an Indian girl who began to venture into new experiences and explore different opportunities, this thought often popped up in my mind. It was quite common to hear that this was a shared thought of many Desi girls I had the privilege of meeting. It seemed as though we all experienced chains of restriction regarding what we could wear, who we could fall in love with, our career paths, and even our own day-to-day decisions. We all felt it was a double standard that the Indian males in our

lives could go out late with whoever they wanted, drink alcohol without judgement, choose careers they felt fulfilled by, and never seemed to receive backlash from the older generation as Indian girls in the community commonly would.

As I began to reflect about some of the traditions in my Indian culture, there seemed to be a few things I would love to rewrite. For example, I remember being shocked to realize that none of the older, married Indian women I knew in my life were proposed to by their husbands. Being an avid fan of the popular show, The Bachelorette, the idea that all my aunts never received a proper marriage proposal where my uncle would get on

one knee was honestly heartbreaking. To me, the act of the person you love getting down on one knee, to ask to be your life partner is and should be a memory that every couple has the chance to experience. It is a moment they can cherish for the rest of their lives. This was not the only time, however, that I strongly felt a need to break the chains of age-old Indian traditions. I remember I was at my aunt’s house for a family gathering, and she handed me a prepared plate of food and told me to start handing it out to the men at the party. Since I had known my aunt for many years and felt comfortable enough to say this, I asked with curiosity why women were always expected to serve men. At that moment she sounded like

by Sayona Jose design/ Isha Harshea Nike ambassador because she told me to “just do it”. The thing that shocked me even more, however, was that every Indian wife at the party did the exact same thing, and hand delivered a plate of prepared food to their husbands. I remember wondering why such strong and intelligent women enabled this type of 24/7 service-oriented behavior for their husbands. Do not get me wrong - I absolutely believe that acts of service are a genuine way of showing love, however I wondered where were the acts of service by the Indian men? All I could see was hardworking Indian women cooking the food, presenting it to the men, and then washing the dishes while all the Indian men sat around the table drinking alcohol and conversing.

Despite these experiences that make my blood boil with culturequestioning rage, I feel comfort in the fact that the Indian girls of my generation seem to realize that there is a lack of gender equality and chivalry amidst the older generation. It seems that the Indian women of our current generation are boldly grabbing the pen and rewriting the cultural narrative. Many of the Indian girls I talk to today are actively using their voice to stand up for nontraditional values

which are beyond empowering. From encouraging LGBTQIA+ pride, supporting prochoice initiatives, and destigmatizing the idea of divorce, I have grown to admire the current generation of women for working together to empower one another’s passions and pursuits. I am beyond proud to be able to firsthandedly experience the rise of independence and confidence among our current generation of females as we explore dating, find our unique sense of style, voice our political opinions, and ultimately do what makes us happy. By finding power within one another, we can create a life for ourselves where we do not shy away from what we truly desire. In other words, “Get ready… because here comes an army of Little Miss. Breaking Social Stigmas’’.

desires, interests, or goals.

Ultimately, it is our role as current 21st century Desi women to continue to stand up for what we want in our lives, and how there is no need to minimize our

Whether it be wanting to wear a sexy outfit that makes us feel beautiful, exploring new relationships that help us learn more about ourselves, traveling on our own to experience exciting adventures, or simply recognizing the power within ourselves, we can build a life that we truly feel empowered in. If I could tell my younger self anything, it would be “Trust me - you do not want to wish you inherited the “Y” chromosome because a rise of the “XX” chromosomes is well underway.”

South Korea, the Land of the Morning Calm, is the ulti mate example of a pictur esque nation that will ensnare you in its charm. The jocund spring, the ephemeral summers, the se rene autumn, the bone-chilling zephyrs of winter, and the heavy rains. The Korean traditional spirit is unmistakable and can be tasted in the rich traditional, succulent, and zesty flavors of Korean gour met. From the mouth-watering delicacies like Bulgogi, Tteokbok ki, Bibimbap, Galbi, Jjajangmyun, Samgyeopsal to the world-famous Kimchi which is also Korea’s na tional food. The enigmatic history is bound to have you enamored and the aesthetically pleasing sce nic beauties at every step are sure to leave you gawking and wanting for more. The attractions in Ko rea might take an eternity to cov er. The magnificent, jaw-dropping Changdeokgung Palace which is also one of the numerous UNES CO world heritage sites in Korea, the Hwaseong Fortress in Suwon, the colorful, bustling Gwangjang market to feast your senses, the Bulkag-sa terrace which is the most prominent Silla dynasty ar chitecture, the Jeju-do island for an adventure-filled day of hiking and trekking and the DMZ (De militarized Zone) which divides North and South Korea. Busan, the second-largest city is not to be missed.

Split by a hair-triggering and fear some border, the Korean peninsula offers a dazzling range of experi

ences, beautiful landscapes, and 5000 years of culture and history. South Korea is a dream destina tion, an engaging, welcoming place with the benefits of a high-tech nation. The country’s compact size and excellent transport infra structure mean that tranquility can be found within easy reach of the urban centers. The Korean penin sula is a perfect mix of modernity and tradition. The south, a mix of glittering technology and ancient temples and quirky art villages in contrast to a surreal glimpse into the north, the world’s most isolat ed country.

Seoul, the capital city, is Korea’s soul. In contrast to the traditional, calm, and peaceful native villages and monuments, Seoul is teeming with life round the clock. It is a city that never sleeps. From the busy marketplaces to the heavily crowd ed subway station, anywhere you go, you are bound to encounter a crowd. The metropolis is adorned with tourist attractions like the fu turistic Dongdaemun Design Plaza with a park on the terrace, nestled among the historical Gyeongbok gung Palace and the Jogyesa Bud dhist temple. With the surrounding Incheon city which houses the Incheon International Airport, one of the largest and busiest airports in the world, and rated the best air port worldwide, it is the transporta tion hub of South Korea.

One of the most popular things in Korea is no doubt the Korean Hallyu wave which first swept the

Written By Ishita Sen Design By Amreen Naveen

country in the 1990s and has ex panded around ever since. The Chinese word Hallyu wave means Korean wave which includes K-Pop and K-Drama spreading their arms far and wide into the 21st-century world. The Gangnam K-star road in Seoul is dedicated to the Ko rean artists or idols as they are prominently recognized, while also including 18 large-sized Gangnam dol (Gangnam idol) of BTS, EXO, and other famous K-pop groups. A K-pop fan can experience paradise while traveling around the K-star road and exploring the various companies like Bighit Entertain ment, SM Town, JYP Nation, home to the world-famous K-Pop groups like BTS, EXO, and GOT7 respec tively to name a few. South Korea has now emerged as the leading power in the music industry. It is a must-visit for K-Pop lovers.

Every step in this utopia has some thing new and engrossing to offer. It is indubitably one of my favor ite countries. I was introduced to South Korea in 2016. It was just another day, of lying on the bed lis tening to music on shuffle when a song I never heard played through the earphones. It was a language I did not really recognise, nonethe less I was engrossed. It was ‘Blood, Sweat and Tears’ by the musical group BTS. Curiosity made me search the song and the group on Google and just like that I fell into the big gaping rabbit hole of their songs, music videos, choreogra phy, mind-blowing storyline, along with their struggles and hardships. With it came the beauty of Korean culture and the county as a whole. What started with just a song and my love for BTS, which is ev er-growing, it also exposed me to Hangul, the Korean language that I have been learning for 3 years now. Moreover, I was engaged to explore the cuisine, music, festi

vals and everything there is to em brace about South Korea. This phenomenal country adorned with pulchritudinous architecture, heavenly cuisines, rich tradition, culture, and the enticing world of K-pop and K-Drama is bound to leave you in awe. South Korea’s camaraderie, its rhapsody and its prismatic essence can make a person euphoric. Donning the tra ditional hanbok, stuffing the back pack, and packing the polaroid for sure, South Korea is the ultimate destination for wanderlusts.

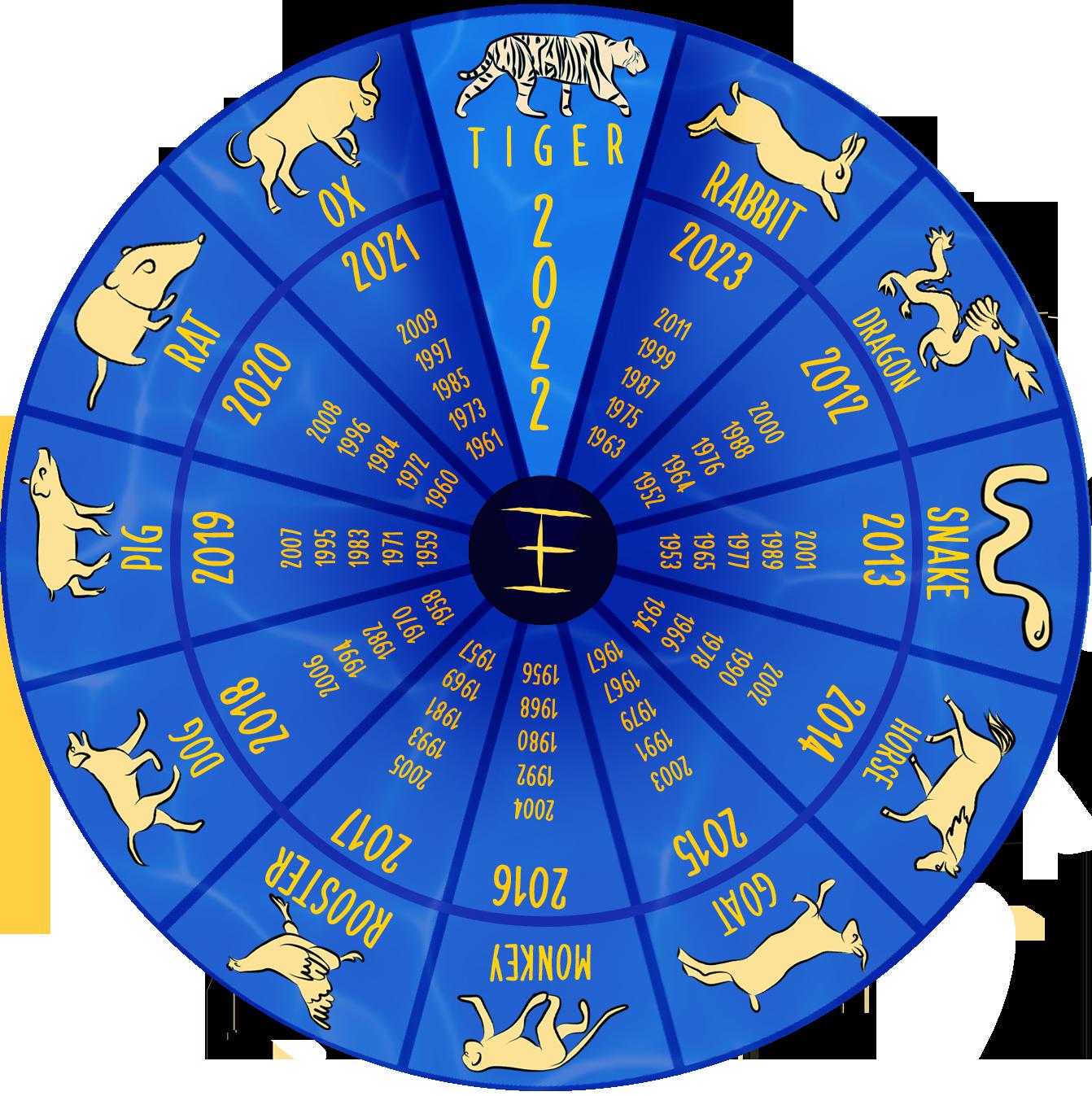

Legend says that long ago, there existed 12 animals of the zodiac: the rat, ox, lion, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog and pig. However, the Jade Emperor who ruled the heavens thought that the lion’s demeanor was too aggressive and hostile, so he removed the lion from the list of zodiac animals. Without the lion’s leadership, the zodiac animals terrorized villages and townships in the human realm. In response, the Jade Emperor decided to send the tiger down to keep the animals in check. In the human realm, the tiger defeated the three animals who were the ringleaders of the chaos: the lion, the bear and the horse, bringing the animals together again. The emperor was so impressed he drew three horizontal lines across the tiger’s forehead, one for each victory. Later, when the tiger was appointed as a zodiac animal, an additional vertical stripe was drawn on its forehead, creating the character “王.”

The history of the Chinese zodiac doesn’t actually begin with animals, rather it was initially a system to keep track of dates and years. The first records of the sexagenary cycle, a cycle of 60 years containing five subsets with 12 years each, began sometime around the Shang Dynasty in 1200 B.C. Almost 800 years later, during the late warring states era, animals were incorporated into the cycle, and the association of years with zodiac animals became widely popularized by the Han and Zhou dynasty. Under Chinese influence, various other

cultures, such as in Thailand, Singapore and Japan adopted similar zodiac systems as the Chinese zodiac. However, there tends to be slight variations. For example, Japan uses the wild boar instead of the pig, and Vietnam uses the cat instead of the rabbit.

The sexagenary cycle carries over into today’s modern zodiac system, which consists of five subgroups: fire“火”, earth “ 土”, metal “金”, water “水” and wood “木”. In addition to the widely regarded 12 animals, each year is then subcategorized into one of the five elements, and people born in a certain zodiac year share respective traits with the year they were born with.

For example, 2022 is the year of the water tiger and incorporates additional water-like traits such as gentleness, but 2010 was the year of the metal tiger and is associated with metal-like traits, such as endurance.

"Tigers have symbolized courage and driving out evil even as far back as the Song dynasty."Model/JiaTing Lions

The tiger is widely regarded as the second most powerful zodiac animal in China, right behind the dragon. While the dragon is seen as the king of the heavenly world, the tiger is known as the king of the physical world— so much so that the stripes on a tiger’s head are seen to resemble the Chinese character “王,” which translates to “king.” In fact, tigers have been long regarded as apex predators in China, hunted by no other animals except humans. Because of their strength and power, tigers have symbolized courage and driving out evil as far back as the Song dynasty in the ninth century, where soldiers bore talismans and shields engraved with tigers.

This year is the year of the water tiger, meaning that along with traits associated with the tiger, the element of water also holds significant meaning. Steve Kory, a professor in the Department of Chinese Language and Culture at the University of Florida, explains that this agent signifies flexibility and the growth of relationships while the tiger symbolizes strength, courage and ambition. This year, dark yin “阴” energy that is typically seen in water helps mellow out the light yang “阳” energy that is seen in the tiger, resulting in a more diplomatic year.

Perhaps the best example of the year of the water tiger is transitioning out of the pandemic, which requires both the ambition and drive of the tiger, but also the flexibility and wisdom of water. With the prevalence of unforeseen circumstances and quick changes, which are common features of tiger years, people have shown incredible resilience and solidarity through world events such as record-high inflation rates, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, monkeypox outbreaks and Hurricane Ian. It can also reflect personal events, such as moving to a new place and adjusting to college life. Moreover, as some aspects of life change back to their pre-pandemic ways and other aspects remain permanently altered, steadfastness and adaptability are two characteristics much needed in the face of new changes.

For the coming year, Chinese New Year occurs on Jan. 22, and it marks the beginning of the year of the wood rabbit and the ending of the year of the water tiger. Kory says to expect a more pacified and laid back year, one far less aggressive and volatile than the year of the tiger. Even if the zodiac animal horoscope isn’t a hundred percent true all the time, each year serves as a way to highlight and focus on different qualities present in their respective animals. In 2022, the Year of the Rabbit will focus on

sensitivity, grace and care, something much needed after the Year of the Tiger’s emphasis on pushing forward and adapting.

Beyond predicting the horoscope and trends for each year, the Chinese zodiac system achieves an even higher purpose by bringing people together. For thousands of years, people have celebrated Chinese New Year with friends and family by watching firecrackers, eating delicious food and enjoying cultural performances. One of the best ways to immerse someone in a culture is through hearing its folktales and experiencing its traditions, and the story of the Chinese zodiac goes hand in hand with Chinese New Year celebrations. The cultural keystones are classic, widespread and enjoyed by both natives and people wishing to learn more, introducing a common ground for the connection between people of all different backgrounds.

At UF the Chinese New Year show is the biggest performance hosted by the Chinese American Student Association (CASA), and it serves as testimony of strength in the community, even as the show is being held an entire month after Chinese New Year and on a campus that is not predominantly Asian. Jason Gao, the president of CASA, explains that celebrating Chinese New Year is an opportunity “to find a home away from home and foster a welcoming environment where our members aren’t afraid to be who they are.”

Perhaps, just like how the tiger brought together all the zodiac animals, the zodiac does the same for people. Kory says it best, “It’s not in the individual and what it does for us…the power of this stuff is in the collective.”

"Chinese New Year is an opportunity 'to find a home away from home'"

- Jason Gao

The aroma of roasting cacao, sweet cinnamon, and nutmeg overtakes the house. Sipping on a cup of hand-ground hot chocolate, I am met with the rich bitterness of the cacao accompanied by a sweet hint of cane sugar. The bitter-sweet takes me back to the overseas journey of my ancestors over a century and a half ago. The British empire had sought out laborers from the Indian subcontinent for indentured servitude in the Caribbean. Their task: harvest cash crops such as sugarcane and cacao. Cutlass swinging, back breaking, whip cracking, the history of my ancestors is one of the earliest accounts of South Asians arriving in the western hemisphere. It is also one of labor exploitation, survival, and community-building in the most foreign of lands. To examine South Asian heritage in the US is to reflect on our workingclass origins, and our roots of solidarity-building while in the belly of the beast.

As the bitterness of exploitation and the sweetness of solidarity continue to linger, let us fast forward about a century to the focus of this essay - the arrival of Bengalis in Ellis Island and of Punjabis in Angel Island throughout the early 1900’s. From

the east coast to the west coast, South Asians descended onto the US, this time under much different conditions, but to provide their labor nonetheless.

Before unpacking this lesser known history, the South Asian monolith must be addressed. When many Americans think of South Asians in the US today, they often think of a homogenous group of recently immigrated families coming from the subcontinent seeking economic opportunity. They identify this diaspora with their search for a better life for their children, to climb the rungs of a meritocracy, and achieve the immigrant’s highest level of enlightenment in western society - The American Dream. This narrow perception of the South Asian diaspora in the US works to maintain the status quo of the ‘good’ immigrants or the model minority. However, to really get to know the history of South Asians in the US is to ground ourselves in an appreciation for the workingclass people who arrived much

earlier, building solidarity with others in the US.

Between the 1880s and the 1940s, Bengalis arrived in the US and built communities with the African American and Puerto Rican working classes in cities like New York, New Orleans, and Detroit. People arriving from West Bengal in the late 1800’s settled among communities in the South such as New Orleans where they sold handcrafted goods. Later in the early 1900’s, Bengalis arrived in cities in the Northeast region of the US like Baltimore and New York City to provide domestic labor. When the US passed the Immigration Act of 1917, targeting mainly immigrants from Asian countries, Bengalis sought out communities where they might be welcomed. Many Bengalis of this wave married into the Black and Puerto Rican communities which they lived

by /Vaidehi Persaud design/ Sanikaa Thakurdesai

by /Vaidehi Persaud design/ Sanikaa Thakurdesai

To examine South Asian heritage in the US is to reflect on our working-class origins, and our roots of solidarity, building while in the belly of the beast.

in close contact with. This led to building neighborhoods and families together. Herein lies the intersection of history for many peoples whose histories have over time seeped into one another, and whose lineages have merged. This leads us to the legacy of the Bengali Harlem. Picture Malcolm X sipping fresh chai, enjoying the delicacy of Bengali sweets in the home of a Bengali family in Harlem. Down the street, famed Jazz musician Miles Davis spends the evening with the music of South Asian artists like Mohammed Rafi lilting through his home. At the corner, Muhammad Ali and Kareem Abdul Jabbar are enjoying a halal dinner prepared in a local Bengali restaurant. This was the Bengali Harlem. This was the emergence of a South Asian enclave that sustained itself from community-building alongside Black revolutionaries, artists, and icons of the time. But the Bengali Harlem did not stop there - today we see the descendants of these communities continuing their solidarity alongside one another. In the decades following Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, many Bengalis continued migrating to the US where their predecessors once settled, finding the same communities left behind. In the wake of the September 11th attacks, and with the rise of Islamophobia across the US, the predominantly Muslim Bengali immigrants reported finding sanctuary in the folds of Black and Puerto Rican populations. These groups have faced centuries of state-sanctioned racism, and know the importance of building community in the face of violence. As the descendents of freedom fighters for Bangladesh’s independence, Bengalis who have remained in the intercommunity enclaves continue their support for social justice, especially with the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement. Nonetheless, these histories and the inseparability of our multiracial

struggles remain unknown to many South Asians. We must learn and remind each other what other communities of color have done to keep us safe in the US, and return this same energy as we move onward to a better future.

In the early 1900’s, a wave of people from the state of Punjab immigrated to the west coast of the US, settling across California. Many arrived to provide farm labor in places throughout the Central Valley. With many similarities in immigration, labor history, and culture, Punjabi and Mexican communities in California developed strong ties. Much as was seen in the Bengali Harlem, Punjabi intermarriages into the Mexican community were not uncommon among the diaspora. Fusions of food, music, dance, and traditions promised a growing harmony among these communities.

The Ghadar Movement gained transnational support from working-class people in the broader anti-colonial resistance. This included members of the Mexican community who supported the prominent South Asian struggle. Along with their resistance to British colonial rule, supporters of the movement also demanded better working conditions and treatment for the working class immigrants in the region. Such demands were aimed to improve the livelihoods of Punjabi and Mexican laborers working in agriculture, and especially for those who were undocumented in the US. These immigration and labor struggles reveal an ongoing interconnectedness in both communities’ histories.

During this same time, the Ghadar Movement emerged among the Punjabi Sikh diaspora in California. Supporters of the movement demanded an end to the British colonial occupation of the then pre-partition India. Unsympathetic to the pacifying nonviolence of Ghandianism, the Ghadar Movement adopted a more politically militant resistance to the colonial occupation of India. Many members of the Ghadar Movement were recently immigrated Punjabi farm laborers, factory workers, and university students.

These less spoken-of forms of multiracial solidarity and community are integral to understanding the histories of the South Asian diaspora in the US. We must always remember the struggles of our predecessors and of those who fought for the freedoms we enjoy today. There have always been parallels of South Asian resistance and solidarity with minority communities in the US. The Dalit Panthers and much of the resistance to caste-based oppression in India has been inspired by the Black Panthers and similar resistance to antiBlack racism in the US. The more recent farmers’ protest in Punjab resembles the marches led by many Mexican farm workers demanding better working conditions in California. The historical struggles of many South Asians are inherently connected to the struggles of other communities in the face of systems of oppression. Although our histories and experiences may be unique, we must never forget what unites our struggles. in the face of systems of oppression. Although our histories and experiences may be unique, we must never forget what unites our struggles.

Although our histories and experiences may be unique, we must never forget what unites our struggles.

March, then Tampa, Florida

The air was ripe with the smell of coffee and a new book. My homework remained open on my laptop, neglected in favor of something far more important.

Sabaa Tahir, one of my favorite New York Times #1 bestselling authors, had finally released her new book, All My Rage. After waiting patiently for what felt like forever, the physical copy lay open in my hands. I eagerly began to read, knowing that I would never be disappointed by anything Tahir wrote. But I never expected her words to touch me the way they did I never expected to find myself within the pages.

September, now Tampa, Florida

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

This is a lesson that Noor and Salahudin know well as they navigate their lives after a tragedy. The story of two Pakistani American children haunted by misfortune comes to life in this book. Noor Riaz is a girl who was rescued from an earthquake in Pakistan and brought to Juniper, California by her uncle when she was six. Her best friend, Salahudin Malik, is a boy with an alcoholic father, a mother with kidney disease, and a family-owned motel. After a fight between the two transpires, they are no longer on speaking terms. That is, until Salahudin’s mother, Misbah, passes away. Noor and Salahudin learn to seek comfort in each other again, grapple with the perception of their culture, and find their own ways out of a situation that appears to have no happy ending. The story alternates between Noor and Salahudin’s points of view, with Misbah making brief appearances in the interludes of the book to tell her story. Her character gives insight as to why Salahudin harbors his fear of touch, and shares how she considered Noor her own daughter.

Tahir’s inspiration for this book was the motel that she herself grew up in. 15 years in the making, Tahir worked on the book any time that she felt upset or frustrated. Because it was not written under a contract, it was raw and

by Fariah Ansari design/ Isha Harsheunfiltered. All My Rage became a story for herself and immigrants everywhere who struggled to find their way in a new world. She pours her heart into discussing the dark side of the American dreambeing pestered about whether or not she had a green card, people mispronouncing her name, and her questioning her own identity. In an interview with TIME, Tahir states that “So many of us who feel marginalized, we hold all this anger inside, and we can’t express it without potentially serious consequences.” The result was a beautifully written story that won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature.

One of the main themes of the book is generational trauma. Both Noor and Salahudin are justifiably angry about the hand that fate has dealt them. Noor struggles with a physically abusive uncle who denies her the privilege of learning more about her culture or applying to college. Although his abuse is not explicitly made clear until the book nears its end, subtle hints of foreshadowing make it apparent. However, the mantra she repeats to herself every time her uncle raises his hands on her makes her stay. “He pulled me out. Got me to a hospital and didn’t leave my side,” she tells herself. “He gave up everything for me. Now it’s my turn.” There is an anger within Noor that she keeps hidden under the guise of gratitude for her uncle. It is the begrudging resignation that many immigrant children feel- to be grateful that their parents sacrificed their livelihoods to bring them to America, the obligation they have to repay their parents for their efforts no matter how difficult it may seem. Salahudin struggles with similar monsters. With a father who loses himself in drink, leaving him to run the motel on his own after his mother passes away, Salahudin finds himself hating the choices that his parents made. Underneath his cool composure, he detests that his father’s need for oblivion is greater than his duty as a parent. He hates that his mother was too afraid of upsetting the delicate balance of their lives by addressing the problem directly. Most

of all, he is angry at himself for not doing more to keep his mother alive, to keep his father from drinking, and to keep his friendship with Noor. Noor describes this feeling beautifully when she says “What’s the word for when someone drinks so much, they are ruining your best friend’s life? Or the word for a man so vengeful about his own past that he wants to destroy your future? What’s the word for a woman who was sick for months, but refused to go to the doctor until it was too late? The word for the girl at school whose personal mission is to mess with your head? Anger’s not the right word. Rage. That’s what this feeling is, eating me up.” Noor and Salahudin are a reflection of every child who lost their innocence too young, who had to grow up too quickly, who were denied the easy lives of the people who were born into them.

The book is littered with references to Pakistani culture. From the way Tahir describes the cardamoms, pistachios, and almonds in Kashmiri chai to the scent of raat ki raani, Tahir artfully describes how Pakistani culture is kept alive by the few Pakistani residents in Juniper, California. Both characters live with the label of “other” in a predominantly white area. Salahudin’s classmates prefer to call him Sal and Noor is accused of being an illegal immigrant on several occasions. Noor longs for a connection to her culture. Her uncle is vehemently opposed to this and forbids her from visiting Misbah or the mosque. Despite her uncle’s opposition, Noor finds her connection to her roots in Misbah, who makes her Pakistani meals and watches drama serials with her. She finds it in Imam Shafiq, the head of

“ “

the Muslim community, and his wife Khadija, an attorney. She finds it in the small room in Juniper’s military base that is used for a mosque on Fridays. In contrast, Salahudin seems apathetic to his roots. He refuses to drink chai when his mother makes it for him and gets a girlfriend despite knowing that it is verboten. However, Noor and his mother’s voice keep him company. They tell him how important it is to forgive, and how a hand extended to God is never returned empty. Slowly, he begins to inquire about his father’s upbringing and his parent’s life in Pakistan. At the end of the book, he finally visits his mother’s grave for the first time and pours them both a cup of chai.

Additionally, religion is represented tastefully throughout the course of the book. Often, religion is used as a means to an end. A fleeting mention of a character’s religion is not representative of how integrated the religion is in their lives. In contrast, All My Rage weaves Islamic teachings into Noor, Salahudin, and Misbah’s lives. Instead of making Misbah’s hijab a pivotal aspect of her character, Tahir normalizes it to show that the character’s religions are not reduced to a scarf wrapped around the head. Rather, she makes Misbah’s character a testament to how Islam is a way of life for the characters. Noor wakes up to pray Fajr, the dawn prayer. Salahudin frowns upon the normalcy of drugs and alcohol in society. Misbah understands that people’s actions are only for God to judge. The character’s willingness to relinquish control over their lives and place their fates in the hands of God shows just how much religion was integrated into their daily lives. Misbah’s steady presence in

Salahudin’s life, even after her death, allows him to connect with his religion in a way he was previously unable to. He remembers what Misbah told him“The more you ask for, the better. Because it means you’ve put your faith in something greater than yourself”. One of the most poignant themes in the book is how a hand extended to God is never returned empty. The characters learn that perhaps the aid that God sends may not be what they want, but it is certainly what they need.

Writing a book with such heavy themes of loss, found family, and hope is no easy feat. As I was reading, I saw myself in the characters who felt that they were in an inescapable situation with no real good choices. Noor, Salahudin, and Misbah were victims of their circumstances. All My Rage goes beyond the basic immigrant story- it reveals the losses that families endure to achieve the American dream. The angry undertone of the book is a response to racism, parents who failed to show up, and the loss that people must navigate on their own. I saw myself in Noor, and how she felt that she would never be able to pay her uncle back for saving her life. I saw myself in Salahudin, and how angry he was at God for presenting him with one difficult situation after the next. I saw myself in Misbah, and her own quiet struggle that no one understood until it was too late. As the daughter of immigrants, I realize that I have been privileged to live the life that I have. However, this has not come without compromise. Subtle accusations of terrorism, purposeful mispronunciations of my name for comedic effect, and jabs at the culture I hold dear have taught me that no matter how much I try to integrate myself into American society, I will always have the label of “other”. My story is not one for others to understand, or even hear. It is one that I write for myself, as my experiences become my motivation to keep going, and my thoughts the ink with which I write my next chapter.

Engaging, touching, and introspective, All My Rage is a culmination of the stories and silent struggles that go unnoticed in pursuit of the American dream.

So many of us, who feel marginalized, we hold all this anger inside, and we can’t express it without potentially serious consequences.

“

Walking down a cramped, humid backstage hallway shouldn’t feel like striding through a royal corridor. Yet here I am, in unbearingly scratchy garments, ghungroos on my ankles, and layers of expired makeup caked across my face, head held high with regal poise. Children are scurrying throughout the backstage area, with their skirts, dupattas, and coats rippling behind them in colorful waves. Ankle bells and jewelry are clinking in the hallways to the rhythm of a broken clock.

Days like these are rare, where I don’t feel like I have to hide this part of me and tuck it away in a dark corner until I forget it exists. I feel like I belong, dancing to music I’ve grown so connected to - it’s an inseparable piece of me. On the stage, the spotlight hones into my tiny, gleeful, dancing frame, but it also illuminates the beauty of my culture and my innate way of life. It illuminates me. This feeling is reminiscent of smelling the aroma of attar at home during a pooja, crafting decorative garlands for a festival, strolling through the narrow streets of my parents’ homeland, and enjoying the company and comfort of family.

But the stage lights are dimming now - slowly, slowly, until they’re small beams of light, barely there, glimmering in the dark. I feel taller and heavier, too large for the stage. The garments I’m wearing feel so scratchy, it’s almost painful. My wrists have grown too thick for the bangles constraining them. The jewelry around my neck pierces through

my collarbone and hairpins stab at my scalp and pull at my hair. I want to pry it all off.

I’m reaching out to the lights as if I can magically bring back their warmth. It feels so cold without them. But I’m seeping deeper into the dark. The frigid air wisps against my skin, soothing and gentle. Now, I think I’ve found comfort among the shadows. Nobody can see me here, in my awkward clothes, eccentric makeup, and heavy jewelry. I’m wraped in a soft, protective

felt when I was younger, remind me that everything I loved, I loathe now.

The spotlights remind me of how I should be enjoying the company and comfort of family. I remember the excitement I would feel at the thought of visiting them thousands of miles across the globe. All I see now is a string of broken pasts woven from generation to generation. Nobody talks about it; maybe it’s hidden underneath a cover of arguments, dysfunctional relationships, and declarations of what everybody should or shouldn’t be doing. Often, these have to do with solidifying patterns of patriarchal values and traditions and pushing heavy expectations for following a “safe” path onto children and grandchildren. There is also stigma against the things that are still misunderstood among previous generations. They’re reflected in the same script I’ve heard echoed over the years:

by Anushri Gade design/ Prerana Patibandlablanket, hidden from the dimmed stage lights that dance under my gaze. I want to run away from the spotlights that I was yearning to dance beneath when I was younger. Years ago they shined upon the beauty of the culture I grew up with. But today, they also cast light upon all the shortcomings and conflict it carries. Over the years, these burdens have become unmasked. I’m forced to reflect upon them in a clear view, under blazing spotlights. The spotlights that magnify the burdens I never

Your mother shouldn’t visit her own family too much, she’s married into ours now. You shouldn’t be talking to a therapist, they’ll brainwash you into hating us. You should study and get married on time, your life will be set if you do.

There’s that yearning to feel understood, both by myself and the watchful eyes they call a “tight-knit community”. But it’s hard to be understood when sensitivity and vulnerability are seen as weaknesses instead of traits that mold an audacious character. Growing up with a multitude of mental health issues meant feeling isolated,

“Growing up in a bubble where I’m pressured to adhere to long-standing rules makes me feel like I’m living in an endless performance...”

and oftentimes confused as a child. My family never really knew why I shut down in loud environments, always had multiple missing assignments in my school gradebook, or why I threw fits over wearing scratchy clothes. These behaviors were perceived as a failure to remain obedient and steady enough to be successful. The confusion within myself stemmed from not knowing why I behaved this way, and I kept feeding myself the narrative that I wasn’t resilient enough to meet anyone’s expectations. It’s only now, as a student in college, that I’m able to recognize the role that mental health issues have played in shaping my childhood and reconcile with the fact that it’s okay to be open about my vulnerabilities.

I’m also reminded of how stifled I feel under the pressure of molding myself into something that’s good enough, acceptable enough. I feel the frustration of not being adequately malleable to shape myself into whatever that means. If only I tried harder. There’s a war inside of me over wanting to be accepted, to be good enough to belong somewhere, yet at the same time, I have no desire to conform.

In my family, everyone looks as if they’re seamlessly transitioning from one milestone to another in their lives, just as they’re expected to. It’s like they’ve followed a blueprint that’s been carefully prototyped for decades, a blueprint that guarantees stability and acceptance from those around you. I see how my cousins are praised for getting a master’s degree right after college, obtaining a prestigious job, and settling down with a spouse, all by their mid-twenties. I also see

24 | spring 2022

how family members mumble under their breath about the 30 year-old guy who can’t seem to find a partner yet, or the distant relative who underperformed in school and now works a job that doesn’t pay much. I’ve been told that failing to meet such expectations not only poses a failure to yourself, but to your family as well. Sometimes, I wonder, if I don’t uphold the promise that I’d make my family proud, how would I be perceived? How lost would I look, wandering around, wallowing in my own pride, and ultimately failing everyone else? After all, it’s not only my family that will have something to say, but everyone else as well. Everyone will always have something to say.

Growing up in a bubble where I’m pressured to adhere to long-standing rules makes me feel like I’m living in an endless performance, costumed in a layer of fear that stops me from venturing outside these unwritten boundaries. I’m young, and also scared of doing anything that would bring shame to those who have sacrificed so much for me. I’m afraid of being seen by others as the one that has failed, or the one that my parents have failed to raise. But over time, as I’ve trudged

through this performance, the fear seems to have slowly started molding into something else: a conviction to forge my own path, an identity unwavered by the pressure of expectation. I’ve grown tired of dancing to the same, monotonous song over and over. I want to be able to break free from the stifling values, generational issues, and expectations that I carry as a first-generation IndianAmerican. I’m gradually building the courage to explore the bold, unapologetic aspects of myself, regardless of whether they would clash with the community I grew up in.

As I’m standing on this stage, I’m ready to bring myself under the spotlights again and let them light up both the beauty and the burdens of the culture I grew up with. This time, I’m not wearing a costume. I’m basked in the comfort of my identity and all the flaws it brings. I’ve realized that my roots don’t have to conceal me. As I’ve gotten older and reflected on the dark side of the values and traditions I grew up with, I’ve grown to resent an essential part of me. However, I hope to unconditionally embrace my culture one day, flaws and all, and still have the courage to explore the parts of myself I’m afraid of expressing. I don’t have to find comfort among the shadows anymore because I can perform with courage and authenticity. There’s one thing I’ve learned from years of dancing: only you can have command over the performance and its audience.

This story is by students at the University of

For as long as I could remember, I have always loved dance. Whether it be learning a new dance in class, performing at events with my dance team or dancing on my own. I remember running home from school one day and asking my mom if I could join a Bollywood dance team, and she sat me down and said, you should focus more on studying, you don’t need to do dance right now. She was right, I don’t need to. But I wanted to. I wanted to dance because I loved to, but I couldn’t because I didn’t need to. A few years down the lane, I remem ber running home from school and my mom would be in the hall, watching my sister practice for her up coming performance at a Diwali event, or a Sankran ti event. It wasn’t jealousy that ran in my mind, but the question of why I couldn’t do it a few years back? It wasn’t a money problem, it wasn’t a time problem, it wasn’t related to studies, even my sister went to school. I didn’t realize that it was because my par ents needed time to understand that it always isn’t just what your daughter needs. They needed time to understand that sometimes it was about what we want. It was about what brings us happiness. That we are entitled to have desires and dreams and they can never be too big. Yes, my parents needed that time, but more so often, by the time my parents un derstood their first-born, it’s too late to go back. But it is just in time to not make those mistakes with our siblings. And this is just one of the many struggles of older sisters.

Being an older sibling is more than taking care of your younger sibling. The way we are raised, the expectations and responsibilities put upon us,start from the moment we are born. Our journey starts off as the first-born; uncondi tional love may not pour

in all the time, but the restrictions do. Our parents have seen it all, the good and the bad, and they want to make sure we are safe, guided, and perfect. And while constantly being worried about that, they forget that in order to live out our best life, we need to ride the roller coaster, go through those ups and downs. They want to teach us everything. They want to tell us everything they know rather than let us live out the life lessons. So much so that they end up creating an invisible border around us, one built with over-protectiveness, fear, and restrictions.

However, by the time our siblings roll into the world, they now understand the reality of raising a child. Yet, the pressure doesn’t go down on the older sib lings. With first-borns, every step of our lives are new to our parents in their point of view: from the first days of school, hitting puberty, to writing the SATs, applying for college, and living away from parents. Especially with many Asian-American families, as immigrants, everything they experience is new. It’s a new life, new generation, and new experiences. All this newness makes them more overprotective, hence adding layers of restrictions. Raising younger siblings is like repeating an experiment, they’re more confident and know what to expect and how to sup port them. As for older siblings, parents raise them in a way that prepares them for the worst.

However, if you look closely, being an older brother often results in being given less responsibilities. And they aren’t seen as selfish for doing what they want. All this toxic patriarchal nurturing leads to older brothers developing feelings of entitlement while older sisters developing feelings of guilt.

Guilt from being expected to sacrifice our

by Yasiswi Nimmagadda design/ Dan Pham & Kristin Kavilaveettil

by Yasiswi Nimmagadda design/ Dan Pham & Kristin Kavilaveettil

desires and happiness and put ev eryone else before ourselves, and guilt from living out our dreams regardless of being expected to succumb to the stereotypical expectations of women. Older siblings, sisters, often more than anyone else, are placed under the constant pressure to live up to the harsh expectations of our parents, and live under constant scrutiny and criticism of the society. As important as it is to uphold our cultural, religious, and geographical traditions, not all are entitled to be carried forward. Some need to be stopped from being nurtured in households.

dysfunctional family, Priyanka Chopra’s character breaks her parents’ toxic views on life by putting her happiness and peace first in a “non-traditional way.” She supports her younger broth er by standing up to her parents and emphasizing how personal happiness is more important than wealth or conforming to social expectations. She pushes herself and her parents to let her choose her own freedom and her actions let her brother achieve his

dream of flying and marry a girl out of their religion, all which their parents would have revolted if it weren’t for their daughter being the torch bearer.

That is what Priyanka Chopra is in Dil Dhadakne Do. In this

paths, but for now I just want to dance.

As older sisters, we are left out to figure out the world ourselves. Furthermore we experience the family pressure, which under mines our accomplishments, making us feel that we aren’t do ing enough. Even though we walk alone many times, we are the lies. Despite all the struggles we endure, being born first into our families is no easy feat. We are the first ones to shatter ceilings and achieve new heights. We figure out the world alone, and come back to walk our siblings

My parents expect me to be a role model for my sisters and refrain from doing things like getting a tattoo, dyeing my hair, getting a second ear piercing, etc. There have also been times when I have been blamed for their mistakes and the reason being ‘they learnt it from me’. Something I would think to myself then is who is responsible for my actions then? Who did I learn it from?

- Aksa Merin Santosh -

“As an elder sibling who has already finished high school and is in college, my parents expect me to guide my brother so that he won’t make the mistakes that I have made.... So they expect me to be a good role model to him and help him make good decisions.”

- Sri Hasini -

“As an elder sister, you are expected to know wrong for right, what to do, and solutions to just about anything. Those expectations make you forget that you’re still a child and it’s okay not to know.”

- Nidhi Patel -

- Nidhi Patel -

“I feel like the most recent struggle is probably feeling like a complete failure because I didn’t have anyone to guide me and I kind of had to figure everything on my own and I didn’t get the best.... Now I have parents who want the best for their second child and want me to help him and a brother who doesn’t care because he already knows he’s smarter than I can ever be.”

- Akshitha N. -

Iam not beautiful. A girl that looks like me cannot be beautiful. At least that was the subconscious narrative running through my head.

Playing with Barbie dolls was an integral part of my childhood. I had all the accessories, the outfits, the tiny plastic heels, I had it all, except for a doll that looked like me; a doll that had black hair, small-eyes, and tan skin. Besides maybe a Mulan doll, my collection was full of blonde hair, blue eyes, and that notorious Barbie body type. Though the first Asian Barbie, “The Oriental Barbie,” was released in 1981, dolls that looked like me were not readily available. In 2015, Mattel launched a line of two dozen dolls featuring eight different skin tones and a few different hair textures. They also released curvy Barbie, petite Barbie, and tall Barbie. By that point, I had aged out of playing with dolls, but I do remember the release of these diverse dolls being all over the news. I have a vivid memory of sitting in an airport terminal watching one of those daytime television shows where women sit around a table and yell at each other. They were discussing how the proportions of the original Barbie were literally impossible and that it was detrimental to the way young girls viewed their own bodies. I remember thinking, I played with those Barbies, and I turned out fine.

nineteen students, I was the only Asian. In third grade I was one of three Asian students (I think that’s a record). In those elementary school years, being the only one wasn’t something that bothered me because I was never given a reason to think about it. Never once was I made to feel like the odd one out or as different.

"

I played with those Barbies, and I turned out fine."

Despite its lack of diversity, the community that surrounded me in those formative years was supportive and loving. For that, I am thankful, because I know that not all are lucky enough to say the same. In middle school, however, something changed. Almost immediately I felt like the other. The bliss of childhood ignorance was hijacked by the anxieties and hormones of teenagehood. The feeling of “other” followed me throughout high school. Like my life prior, I wasn’t necessarily given a reason to feel different, but suddenly, my eyes were opened to all the ways I was different from everyone else: my family wasn’t as wealthy, I wasn’t as skinny or as athletic, I didn’t have the right brand of shoes, my uniform skirts were too long. The only thing any thirteen year old wants is to fit in and for the first time, being the only one that looked like me was so glaringly obvious. But at the same, I was never able to pin-point how that affected me. It’s hard to want something that you don’t even realize is missing.

by Reagan Huynh design/ Jessenia AbrigoGrowing up in an upper-middle class family and attending private schools whose student body was primarily white, I can count on one hand the Asian-American classmates I had. Prior to college, I attended school with the same group of people and was used to being the only Asian in the room. For example, in my second grade class, out of

It was only once I got to college that I truly experienced diversity. Walking through Cooper Hall you’ll hear people speaking multiple different languages and see so many different ethnicities. On my walk to class today, I saw more diversity than I ever saw growing up. I realized the

lack of representation and diversity in my upbringing. A few months ago, during a late night conversation with my childhood friend, we realized that when we thought of someone who is pretty, we imagined the same blue eyed, blonde haired, fair skinned girls we grew up with. Through fits of laughter, because our realization was too sad and too real for us to cry, we realized that in our minds, we always thought we’d never be pretty in the way that those girls were.

The first time I thought that I could possibly be considered pretty was this summer, while watching Amazon Prime’s adaptation of Korean-American Jenny Han’s novel, The Summer I Turned Pretty. The adaptation stars Lola Tung an Asian-American actress. Lola Tung’s character, Belly, is a mixed race teen with a Korean mother and white father. The show is centered around Belly coming into womanhood and growing into her beauty. Belly is constantly being praised for how pretty she is and her looks garner attention from several boys throughout the series. While watching, something finally clicked. If everyone thinks that she is pretty, and she has similar features to me, maybe I’m pretty too. I saw myself in this character. Never before had I felt represented. Finally, I was able to verbalize that subconsciously, I thought it was impossible for myself to be considered pretty. I was able to realize that my idea of blonde hair and blue eyes as the only form of beauty was false. Just because I’m not white doesn’t mean that I can’t be pretty too.

Prior to this realization, did those subconscious thoughts keep me up at night? No. Before realizing this, did I have an awful self-image and low self-esteem? No, I had always appreciated who I was.

So why does this matter? Maybe my false idea of beauty

wasn’t something that tormented me inside, but I can look back on places where it limited me. I never dated in high school. There were people I liked and looking back, I’m almost certain they liked me back. But I could never push myself to pursue it because in the back of my mind I thought that a guy wouldn’t want to date a girl like me. He wants someone pretty and I’m not pretty. In high school I had plenty of friends, but I never had a solid friend group. Those girl friend groups intimidated me, I never felt like I was truly a part of the group. In reality it’s more likely that I didn’t allow myself to belong because there was something in the back of my mind telling me I was lesser than them. This reflects in my work as a writer. All of the main characters I’ve created are white. Even though their race is never important to my story, in my mind, my characters have always been white. I think it’s interesting to note that Belly in Jenny Han’s original The Summer I Turned Pretty novel was white. In a creative writing class, we discussed how writing tends to be autobiographical in some ways. I automatically gravitated towards writing white characters because that was what my experience was based off of. But it’s up to me to change the narrative and write characters that are more representative of me. Maybe one day I’ll write a novel that will resonate with someone in the same way that The Summer I Turned Pretty resonated with me.

Representation is more than a buzzword. Actually feeling represented is more than a warm and fuzzy feeling. Seeing yourself represented in someone else lets you know that you are not the only one, and for most of my life I thought I was the only one. I was the other. I didn’t belong in a room full of pretty white girls. Because I was the Asian one. But now I know I am a pretty girl and I belong in that room too.

" Just because I'm not white doesn't mean that I can't be pretty too."

"It's hard to want something that you don't even realize is missing."

tilted heads, rosy cheeks, hidden under their bronze skin. hidden, implied. whispers, giggles conversations my ears weren’t invited to but my eyes sneaked into. their eyes glance around failing to meet mine as i pry into a world that fails to be mine. intertwined hands clasp and unclasp. my hand over yours, or yours over mine?

the tickles of an awkward, yet innocent love. the rush of a novel, yet forbidden love.

elbows brush, the slightest graze, still failing to meet my gaze.

i speed past, my own cheeks blushing

the red of the stoplight. adjusting a mirror reflecting a life opposite of my own.

his hands mold around her chin, gently pulling her in, breaths hasten lips tickling one another, finding their rhythm tasting each other.

a minute lasts longer than it normally would, for even time itself savors the taste of love.

the clock refuses to turn. their lips refuse to leave. the light refuses to turn. my eyes refuse to leave.

the shackles of longing clang with every step, for these are the moments I stole for my scrapbook of their memories.

You don’t like spicy food?”

“You don’t like Bollywood?”

“You’ve never taken Indian dance classes? You’re so uncul tured.”

As a United States-born girl of Tamilian descent, I have by no means been immune to being told any of these statements. I have often been criticized for “failing to meet the standards” of my own culture. Sometimes it seems like regardless of the environment I am in, there is always some factor of my cultural identity that is so often misinterpreted or wrongly assumed.