3Ps Parents, Preschool teachers, and Providers at the healthcare clinic

DOCC Dietary Observation in Child Care

ECE Early Childcare Center

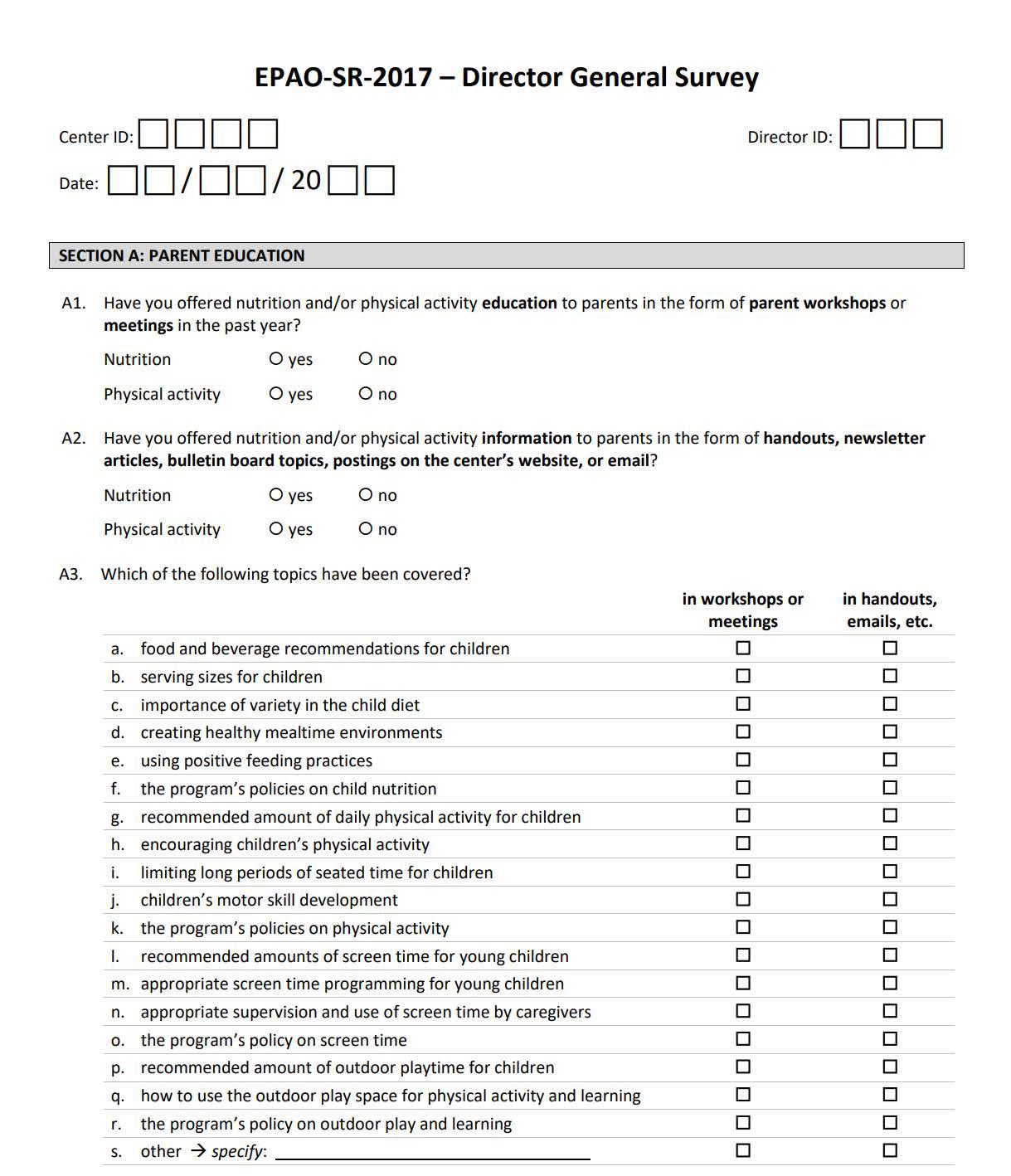

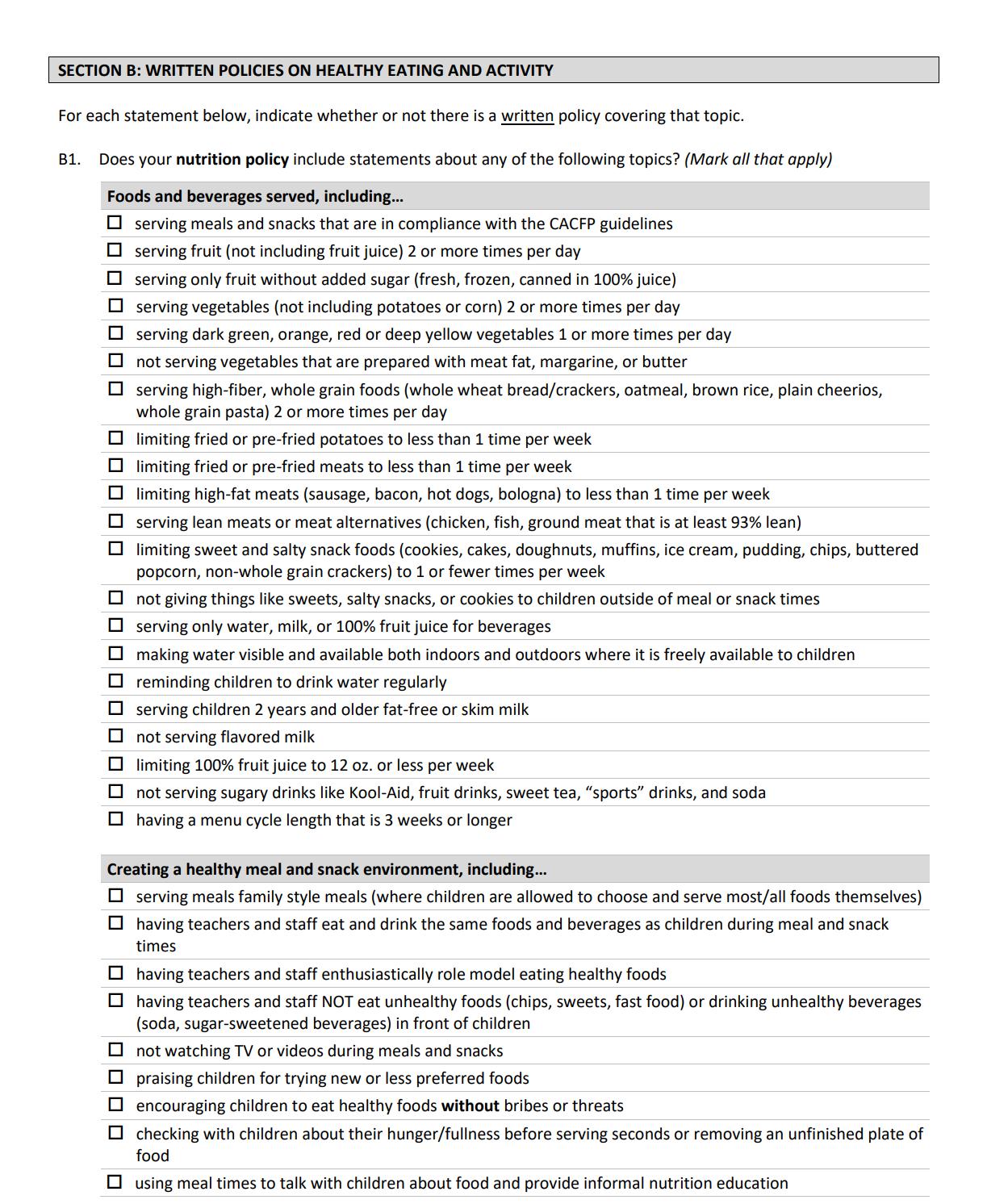

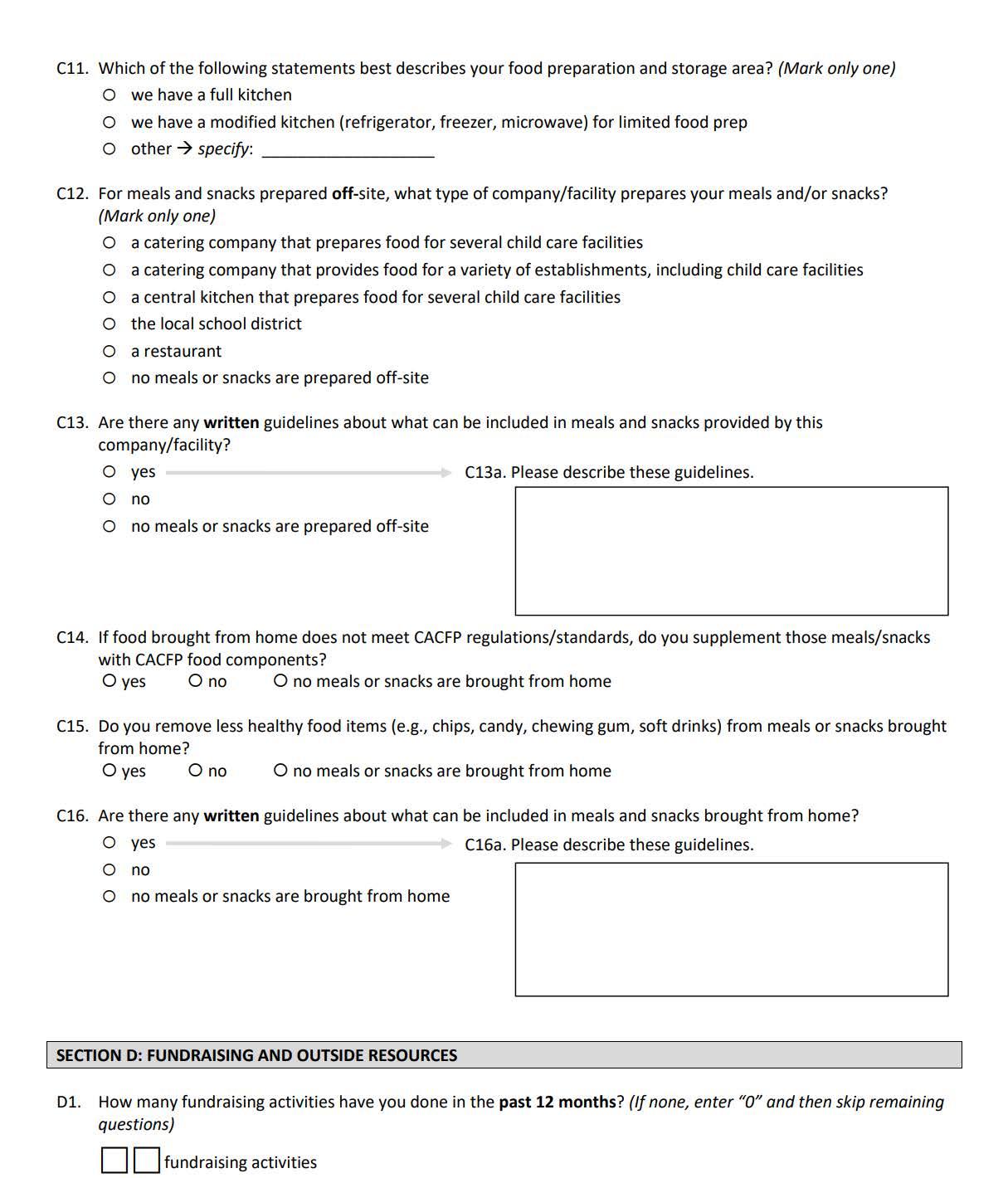

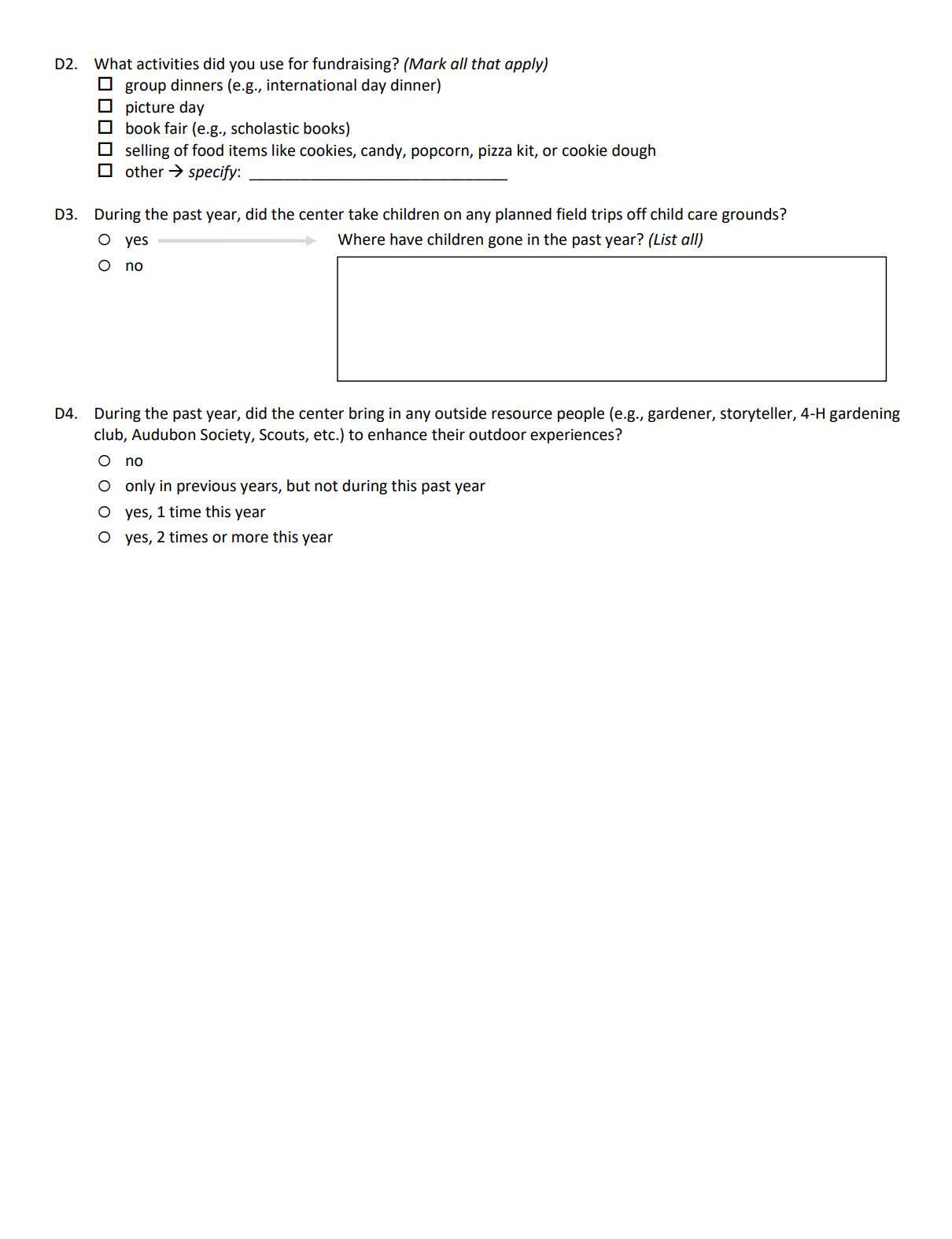

EPAO SR Environment and Policy Assessment and Observation Self-report

HCP Healthcare Provider

IHS Indian Health Service

IRB Institutional Review Board

LOS Letter of Support

MOP Manual of Procedure

MOU Memorandum of Understanding

NAPSACC Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care

NIH National Institutes of Health

OKTEC Oklahoma Area Tribal Epidemiology Center

OUHSC University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center

SPTHB Southern Plains Tribal Health Board

TEC Tribal Epidemiology Center

TECPHI Tribal Epidemiology Center Public Health Infrastructure

WATCH Wellness Around Traditional Community Health

Figure 1 - List of Common Acronyms

Community Partner

Core External Partner

This term applies to a working relationship with organizations, and staff, within the community that WATCH is implemented in.

This term is specific to partners that work in contribution to make up the WATCH program. This includes partners such as Michelle Lombardo from OrganWise Guys, Dr. Dipti Dev and the Responsive Feeding Modules, and Dr. Weedn’s various trainings.

Our Manual of Procedures (MOP) is a handbook that guides the Wellness Around Traditional Community Health (WATCH) program’s conduct and operations. It acts as the program protocol by detailing the program organization, operational data definitions, recruitment, screening, enrollment, intervention, follow-up procedures, data collection methods, data flow, and quality control measures. The purpose of the MOP is to facilitate consistency in program implementation and data collection across participants and community partner sites. Procedures in the MOP should be followed with the same degree of rigor as those documented in the protocol.

This MOP is to be used as a reference document for policies and procedures related to WATCH. All staff members participating in this public health intervention should have access to the MOP and be familiar with its contents. The current version of the MOP and archived versions are housed at the Southern Plains Tribal Health Board (SPTHB) organization. For use of this MOP please contact them at dmedicinebird@spthb.org.

WATCH is funded solely by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Tribal Epidemiology Center Public Health Infrastructure (TECPHI) grant at the Oklahoma Tribal Epidemiology Center (OKTEC) housed in the SPTHB with additional support from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (OUHSC) Department of Nutrition. The current version of this MOP employs a multitude of key players, including Program Manager Marifrances Montell, WATCH Program Coordinator Denny MedicineBird, Evaluator Gary Piercey, Public Health Specialist Alexis Hamilton, all central to SPTHB. The OUHSC Consultant for the program is Dr. Susan Sisson along with Research Epidemiologist, Amber Anderson and a rotating Graduate Assistant. Other SPTHB/ TECPHI staff may assist as needed with WATCH activities and other tasks related to this project.

Marifrances Montell, TECPHI Program Manager

mmontell@spthb.org

Denny MedicineBird, WATCH Program Coordinator dmedicinebird@spthb.org

Gary Piercey, TECPHI Evaluator gpiercey@spthb.org

Alexis Hamilton, Public Health Specialist ahamilton@spthb.org

Susan Sisson, OUHSC Consultant susan-sisson@ouhsc.edu

Amber Anderson, OUHSC Epidemiologist amber-s-anderson@ouhsc.edu

The MOP is a dynamic document that will be updated throughout the program implementation of WATCH to reflect any protocol or consent amendments, as well as the refinement of program procedures. As sections/chapters are revised, the MOP version information and date on the cover page and Table of Contents will be updated.

As the public health intervention progresses, WATCH Program Coordinator will be responsible for documenting any recommended and approved changes to the MOP. The Program Coordinator will incorporate all the approved changes and will update the MOP periodically. When the revisions are final, the MOP will be posted to the WATCH folders within SPTHB and made available to all program personnel. All staff will be notified that the MOP has been updated and is available in the WATCH folders. The author of an updated MOP chapter will ensure that all necessary changes are captured and that the document or chapters reflect the latest version.

If paper copies of the MOP are maintained in the WATCH Program Documents binder, the program coordinator will print and store the updated materials in the binder. Outdated materials will be removed from the binder and filed in another location clearly marked “obsolete.”

Early Prevention of Obesity is Essential for Improving Lifelong Health. Overweight children in kindergarten are 4 times more likely to be obese at age 14, with the poorest children at greatest risk.1 While the national prevalence of overweight in preschool-age children is 23%,2 the prevalence among American Indian (AI) preschool children is 38-48%.3, 4 The prevalence of obesity alone – not including overweight – in AI children is nearly 21%.5 Primary prevention of obesity is necessary to improve quality of life,6 especially in environments where young children spend substantial time such as early care and education (ECE). This is particularly true in Oklahoma where AI populations, obesity, and associated health disparities are prevalent.

Oklahoma AI Children Have Higher Prevalence of Obesity and Related Behaviors. Healthy lifestyle habits, such as regular physical activity,7-9 limited screen time,10, 11 and nutritious diet12 early in life will prevent weight gain and chronic disease. Our previous research in 7-to-13 year old AI children demonstrate they are consuming more calories/day from sugary beverages (309-38213, 14 vs. 17815 kcal); eating fewer fruits and vegetables (1.913, 14 vs. 3.416 servings/day); spending more time with screens (7.213, 14 vs. 2.2-3.717, 18 hours/day); and fewer participate in sufficient levels of physical activity (32%13 vs. 70%19). National Institutes of Health (NIH)

children’s health initiative, We Can!™, 20 and The National Academy of Medicine’s (NAM) Early Childhood Prevention Policies21 include obesity prevention behaviors.

Health Care Providers Have Multiple Barriers to Effective Obesity Prevention. Many pediatric health care providers lack the time and knowledge to effectively discuss patients’ weight status and health habits during well-child checks,22 which last about 15-20 minutes.23 In preschool years, visits are only once yearly24 and providers either avoid or de-prioritize obesity prevention due to limited time and competing parental concerns.25-28 Childhood obesity prevention in primary care has demonstrated modest effects on improving health outcomes and behaviors.29, 30 Effective strategies have included clinician training,31, 32 motivational interviewing,33, 34 multistakeholder community initiatives,31, 35-40 and family engagement.29 Our current work across Oklahoma indicates that some AI parents feel more comfortable at Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) clinics41 and distrust health care providers.42

ECE is an Untapped Venue for Community-Based Programs to Prevent Obesity in AI Communities. Young children have 120 times greater exposure to the ECE environment and teachers than their health care provider.23, 43 ECE environments are important settings for obesity prevention.21, 44 Recognizing the inherent barriers health care providers face, the NIH,20 American Academy of Pediatrics,45 the World Health Organization (WHO),46 and the NAM47, 48 have encouraged expanding the delivery of health information to other sectors capable of providing health information, such as ECE.47, 48 Furthermore, ECEs have room for improving the quality of their environment for promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors. Children are not eating adequate amounts of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and nutrients49-57 or accumulating sufficient physical activity while at ECE.58-63 Our previous research demonstrates the importance of the nutritional and physical activity environment and teacher practices in ECE settings in general64-68 and in tribal ECE settings.4, 61 However, few Programs have leveraged the important role of tribal ECE teachers for childhood obesity prevention. ECE Programs grounded in behavior change theory and implemented at multiple ecological levels have reduced obesity and improved prevention behaviors.67, 69, 70 While several ECE-focused Programs integrated parent components, none, to date, have included health care providers.69

Interventions to reduce obesity and promote prevention behaviors in AI children have had mixed efficacy.39, 71-93 The majority of intervention studies have included elementary and older children, two included infants and toddlers,39, 86 none have included young children aged 2-to-5 years or utilized the ECE environment. Lessons learned from interventions conducted to date include the necessity of environmental changes that support behavioral modification,39, 93 community integration,81, 88, 92, and use of health workers.39 The limited effectiveness of interventions focused on 3rd through 5th graders87, 90, 94 suggest that approaches focused on younger children may yield better outcomes. While another intervention75 included younger grade school children, it did not include community stakeholders. Further, parent outreach,

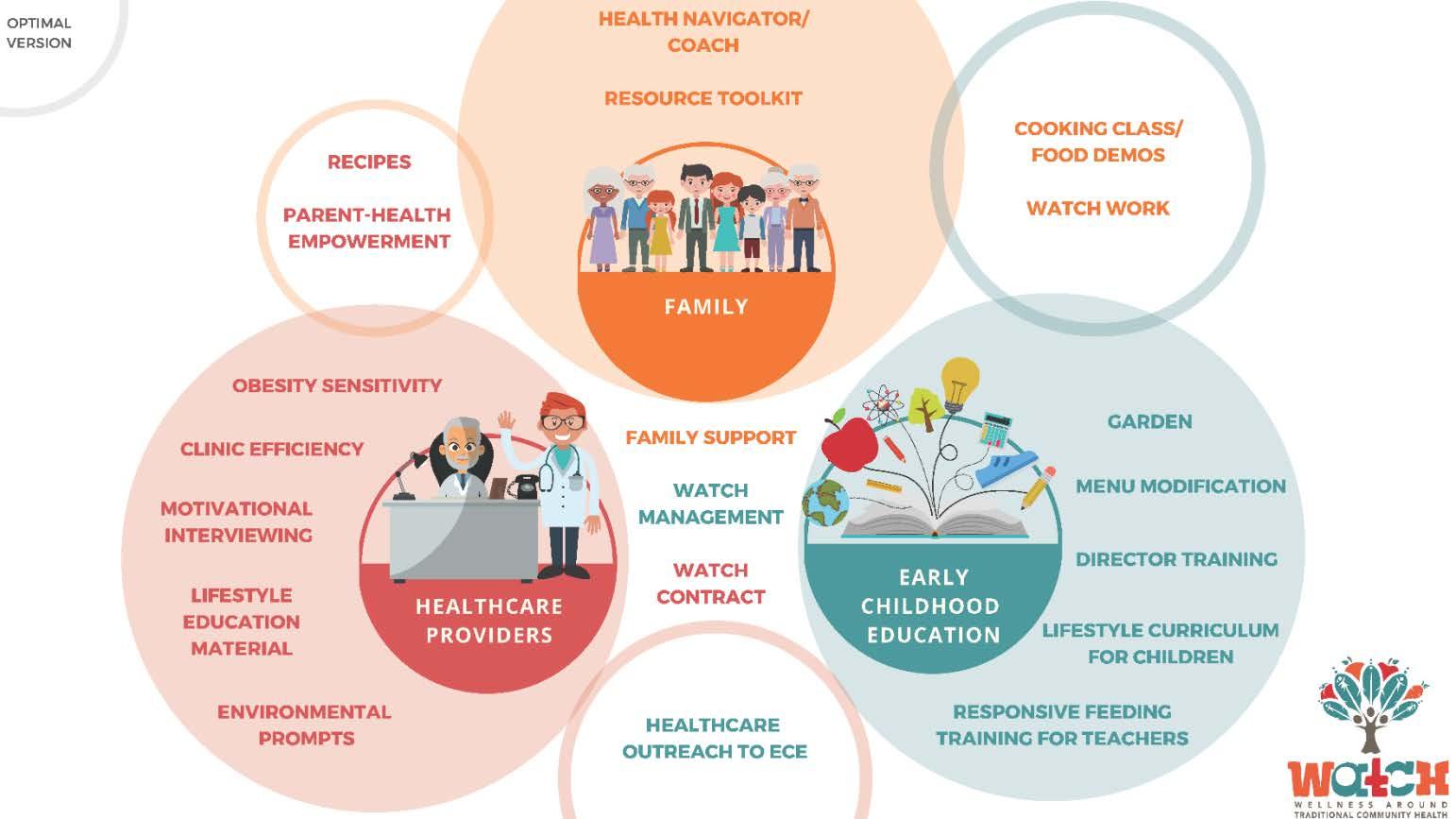

while attempted, was not well-received.75 Partnership with community members and development of advisory board including parents in the intervention development may have enhanced its acceptance by parents. The proposed Wellness Around Traditional Community Health (WATCH) Program draws upon lessons learned from previous intervention studies to maximize the acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy of our multi-stakeholder intervention to enhance obesity prevention behaviors of young AI children in this community. The following conceptual model guides WATCH. This is based on the Social Ecological Model and has been informed by successful evidence-based interventions published in the literature and iterative and formative work with Native American communities in Oklahoma. The details of this process is described in these cited publications.95-97

WATCH strives to enhance the quality of life for children ages 3-5 years living in American Indian communities in the Southern Plains region of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. The overarching goals of WATCH include:

• To create healthy spaces for young children to learn and grow.

• Increase communication within communities from the 3Ps: Parents, Preschool teachers, and Providers at the child health centers.

• Strengthen relationships among the 3Ps.

• Implement an intervention to promote healthy growth and development in children at preschools working alongside preschool teachers.

• Implement an intervention to promote healthy growth and development in the clinics with health care providers (doctors, nurses, PAs, dietitians, etc.).

• Promote healthy weight, growth, and development in preschool aged children.

• Increase healthy behaviors, nutrition, and physical activity, while decreasing screen time within the families of preschool aged children.

WATCH Staff collaborated with the SPTHB Creative Services Department to create a brand icon for the program. The WATCH brand represents an opportunity to tell our story to the communities we serve. It provides a chance for every program coordinator, teacher, parent, tribal member, and healthcare provider to tell a similar story. It also serves to enhances our communication to potential tribal partners.

Furthermore, it provides a logo for flyers, announcements, and guides conversation when talking about the meaning behind the WATCH brand to community partners. The imagery behind the logo emerged from multiple conversations with Native American community members in Oklahoma.

Figure 3a - WATCH logo expanded

Figure 4 – WATCH Logic Model

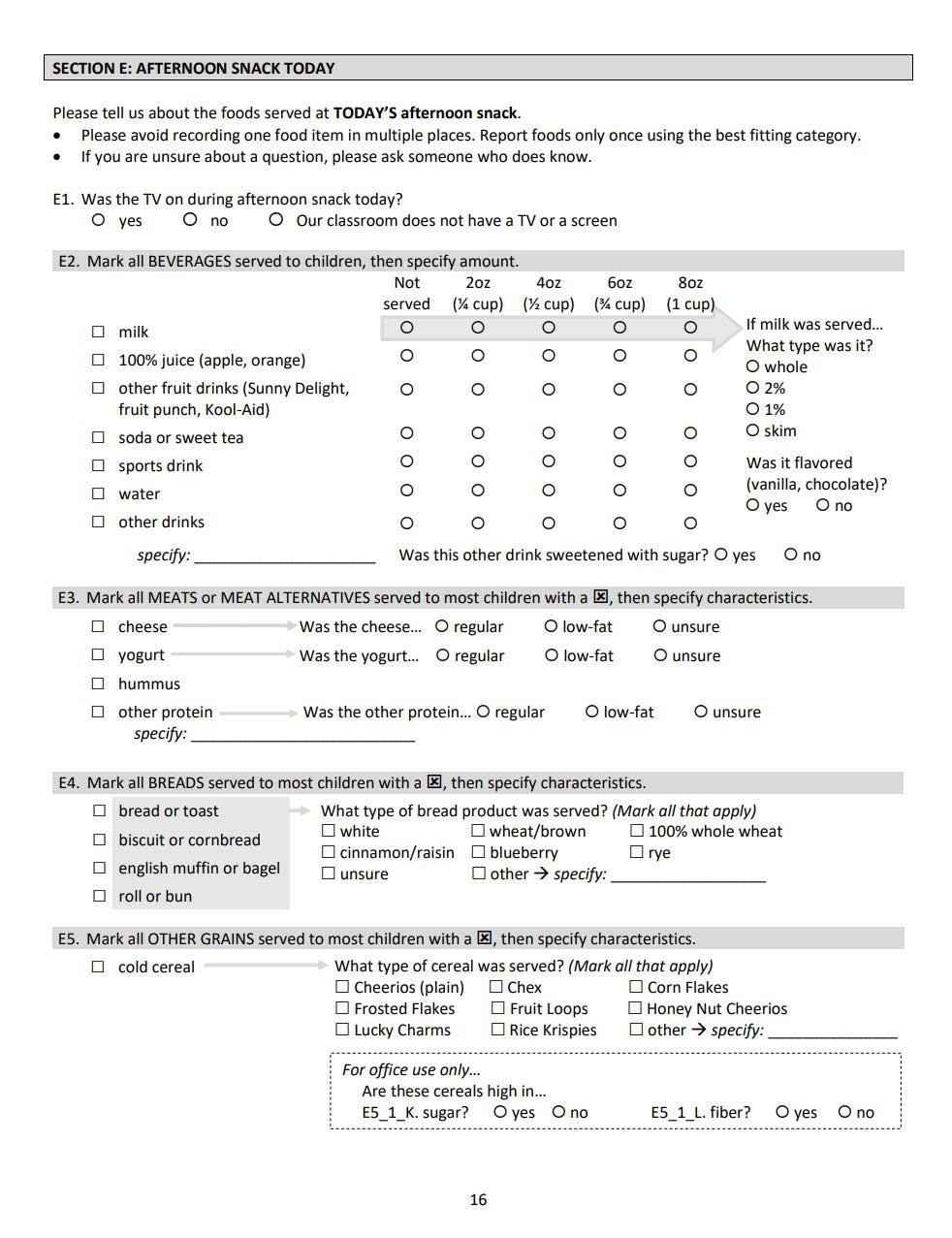

In this conceptual model (Figure 5 – WATCH Conceptual Model) you can see the individual elements of the ECE environment, health care providers, and families influencing each other. Throughout the implementation process, the 3Ps will gain the knowledge needed to improve communication, enhance the environments at schools and clinics, and will be able to promote a healthy lifestyle for each child. It is also evident WATCH will individually strengthen healthy behaviors, which can influence children’s weight and lifestyles across their lifespan.

Figure 5 – WATCH Conceptual Model

While the WATCH program does not conduct research in tribal communities, it does collect various information from key community partners. An application to the Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service (IHS) Institutional Review Board (IRB) was submitted and approved as exempt from research. The WATCH program is conducted in educational settings involving normal educational practices.

The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center IRB also reviews all data collection materials. Intervention materials are not reviewed. The health promotion program evaluation operates under IRB #9773.

This section of the MOP describes some instructions regarding the process of waiving informed consent. Within this document the process for trainings, site requirements, WATCH staff obligations, and expectations are all delineated. Participating ECEs and healthcare clinics prior to implementation will be provided with a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) or Letter of Support (LOS) that informs them that participation is voluntary and can be concluded at any time. These documents also stipulate that any data collected does not include any identifying information.

A waiver of informed consent is approved by the OUHSC IRB to reduce burden for participants and since the purpose of these data collection are not for dissemination or generalization but to improve the program quality for the respective community.

Of these processes any document serving as a tool for data collection regardless of participant states that participation is voluntary, and the use of data is intended only for data analysis. If any results, information, or data are to be shared, the participants will be informed, and they will receive a copy.

Data collected for the purposes of WATCH Program implementation do not contain any health protected information and no data from children will be collected. Children’s weight or Body Mass Index (BMI) are not to be collected. If for any reason any identifying information is collected, it will be de-identified and destroyed. There are no names used when sharing documents or analysis with any of our community partners.

OUHSC and other community partners along with SPTHB staff are eligible for mileage and travel reimbursement following federal guidelines. Those who attend WATCH meetings, trainings and other related events at the community sites are eligible for mileage reimbursement via monthly mileage documents or travel authorization forms. This paperwork will be completed by the Program Coordinator and partner and will be forwarded to SPTHB offices to process.

During WATCH program implementation there will be many opportunities for incentives. Teachers are eligible for gift cards for pre- and post-surveys as well as weekly process evaluation surveys. To be eligible, a predetermined number of weekly surveys are to be completed to meet the completion goal based on the actual number of weeks curriculum was implemented.

The incentives for Parents are awarded through participation in the WATCH parent/family nights. These family events empower parents and guardians to increase healthy nutrition and physical activity with their child as well as provide him/her with resources. Participation allows each family to be eligible for a crockpot giveaway at the end of the WATCH night. Names are drawn at random from participants who were determined eligible to receive the incentive item.

A special thank you is given to all the community partners that have not only been vital to program implementation but for allowing WATCH to be part of their respective communities. WATCH is a collaborative effort in which all community partners play a key role. Without the interest and continued efforts of community partners, WATCH would not be able to flourish and go on to other tribal communities.

Ashley Weedn, MD, MPH

• Pediatric specialist from OU Physicians- Healthy Futures Clinic, will provide training that includes methods and strategies to aid our health care providers with motivational interviewing, obesity sensitivity, and clinic efficiency. Training typically lasts 3-4 hours.

• Child Health Behavior Specialist from the University of Nebraska –Lincoln, leads our teachers through a module of the Ecological Approach To (EAT) Family Style Dining while feeding children at ECEs and Head Starts within the WATCH communities. She uses responsive feeding best practice and strategies for the ECE teachers and staff to use during mealtimes with the children. Trainings typically last 2 hours.

• Creator of the OrganWise Guys curriculum. This curriculum supplies students in the ECEs evidence-based obesity prevention through lifelike characters that encourage smart decisions when it comes to nutrition and physical activity. The teachers receive the digital platform version that allows them to display lessons and videos on their smartboard or laptops within their classroom. This curriculum comes with a physical activity education component called Wisercise and added nutrition education through the Foods of the Months.

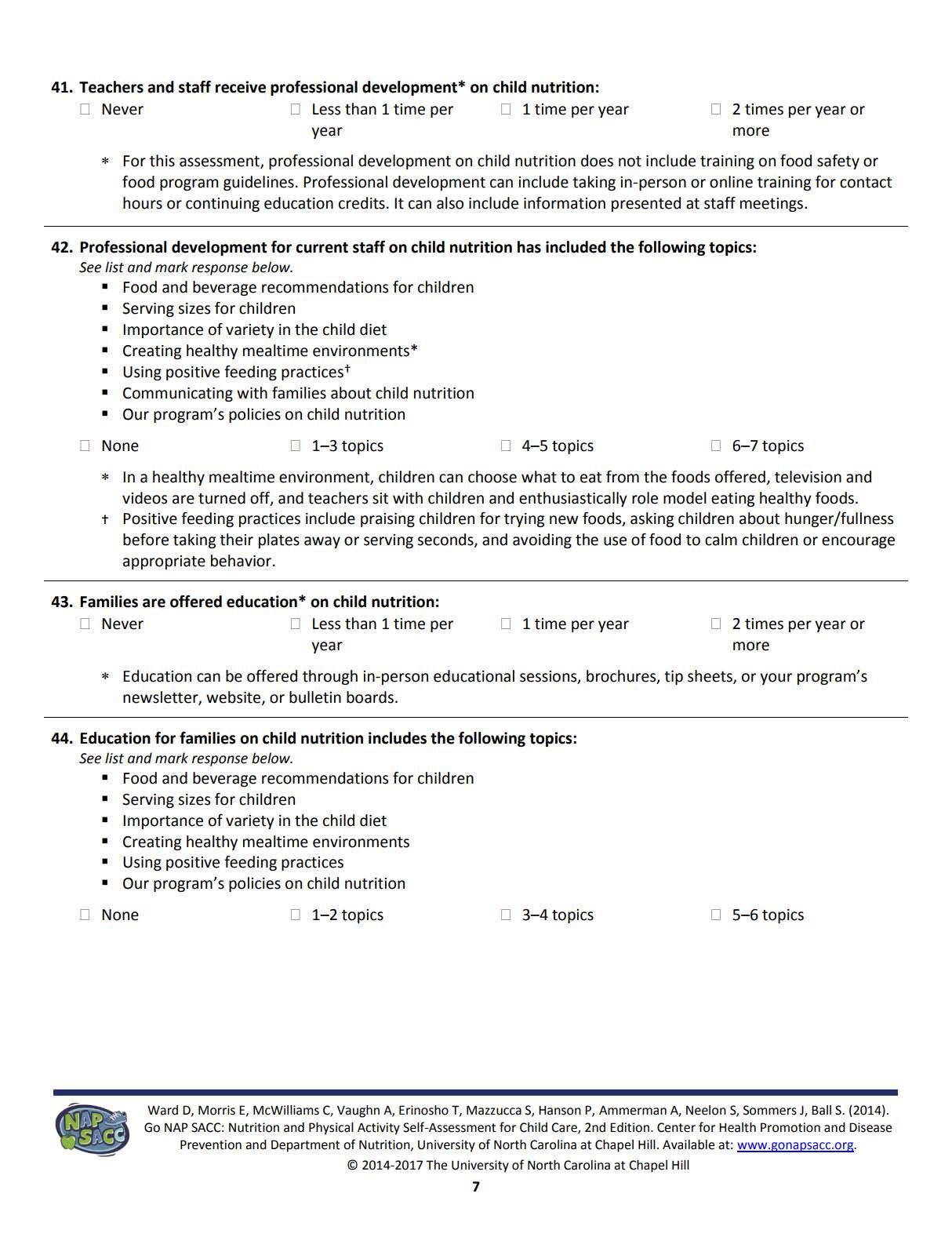

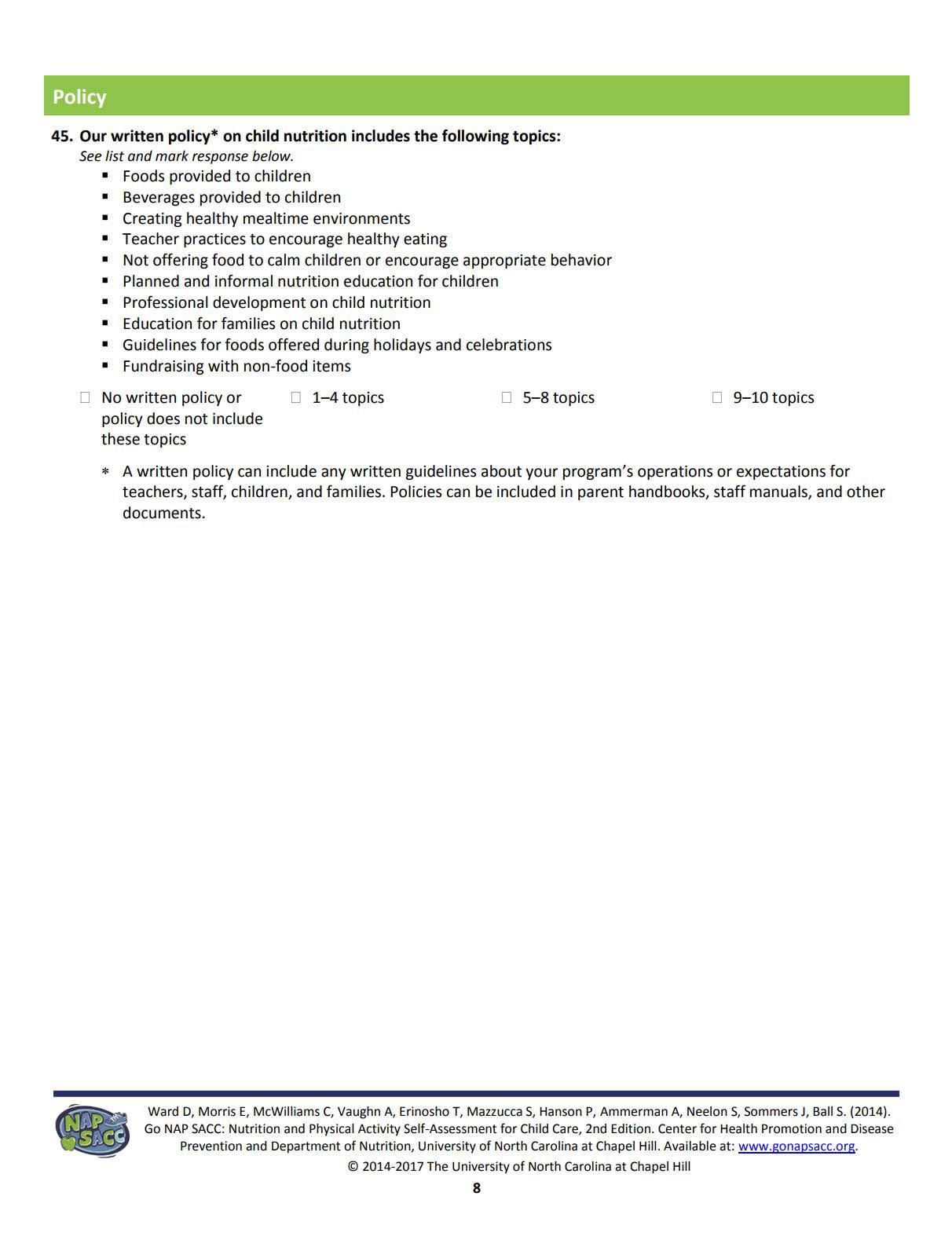

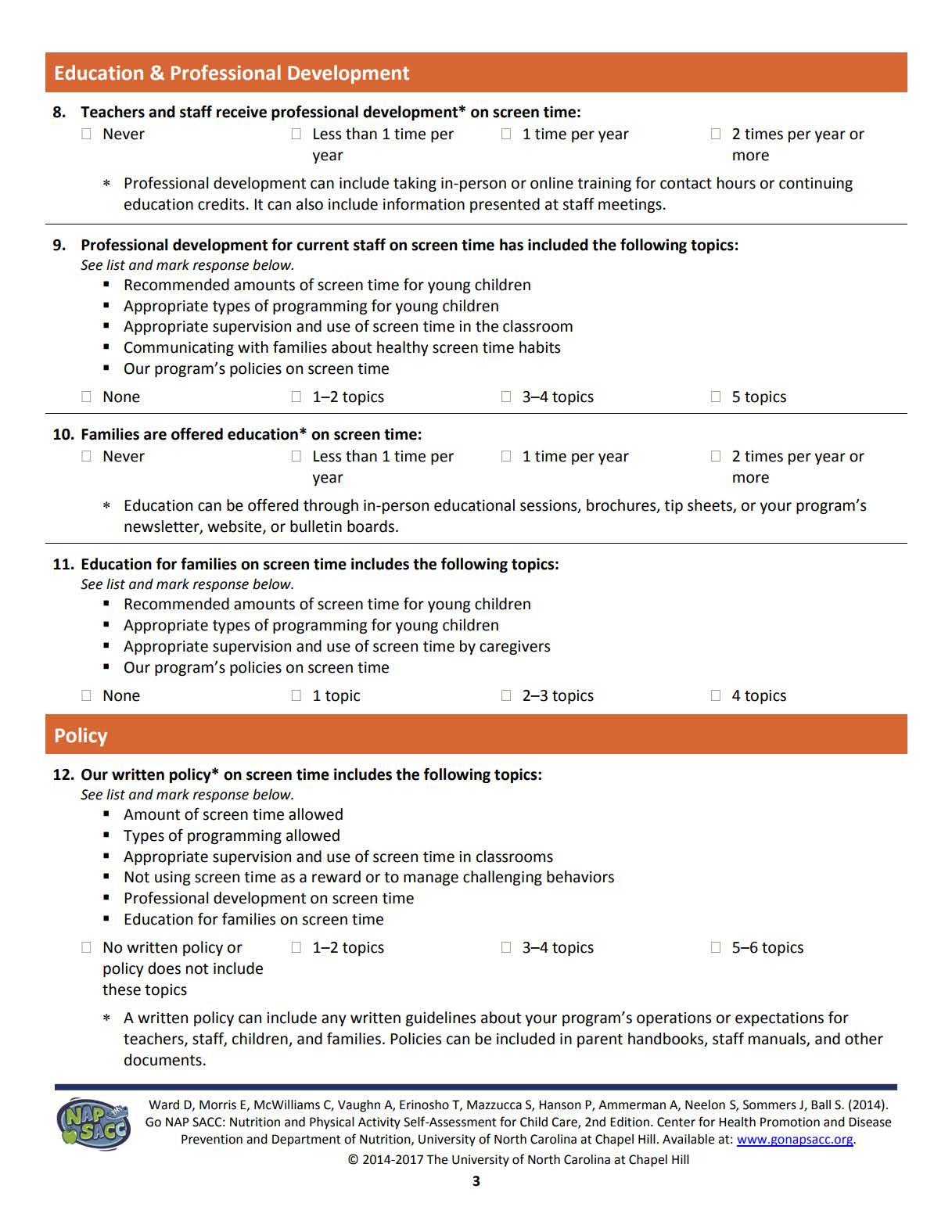

• Go NAPSACC is an online program with self-assessments and training modules to enhance the quality and health of early care and education programs. It is focused on the nutrition and physical activity environment. It has been developed by Dr. Dianne Ward at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Go NAPSACC is available through the Oklahoma State Department of Health. SPTHB WATCH staff are trained and served as consultants on the Go NAPSACC program. The WATCH staff can review the selfevaluations by the participating ECE programs, guide participation in learning modules, assist with goal development, and provide technical assistance and support to meet goals to enhance nutrition and physical environments in ECE. Go NAPSACC has numerous modules that focus on different ages of young children. WATCH programs can participate in any of these modules. However, the priority and role of the SPTHB WATCH staff will be to guide program through the preschool nutrition and physical activity modules before moving onto other modules of interest. The goal of the WATCH staff is to operate as a consultant to the ECE program and guide them through the selfassessment, goal setting, attaining and reflective self-evaluation, provision of resource materials within the Go NAPSACC library.

Bearskin/ Wyandotte Nation/ Eastern Shawnee Tribe community- Early Childhood Learning Centers the Bearskin Clinic (Spring 2018- Spring 2019)

Kelly Friend, Bearskin Clinic Director

Stacie Frieze, Eastern Shawnee Early Childhood Learning Center Director

Tammy Charles / Kristi Hudson, Wyandotte Nation Early Childhood Learning Center Directors

Lindsay Cooper, Wyandotte Nation- Lead Teacher

Cheyenne and Arapaho community- Head Starts, Child Development Centers, and Clinton Service Units: IHS Clinics in Clinton, El Reno, and Watonga (Fall 2019- Spring 2020)

Carrie Whitlow, Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes (C&A Tribes) Department of Education Director

Megan Hart, C&A Tribes Child Development Center Director

Jeneice Hoffman, C&A Tribes Head Start Director

Misty Corwin, C&A Head Start Education Manager

Tara Conway, C&A Diabetes Prevention Program, Registered Dietitian

Dr. Sarah Hartnett, Clinton Service Unit Medical Director

Kristie Purdy, Clinton Service Unit Public Health Nutritionist

Comanche Nation Child Care Centers, Kiowa Tribal Head Starts, and Lawton Service Unit: Lawton Indian Hospital, IHS Clinics in Anadarko and Carnegie (Fall 2021- Fall 2022)

Carolyn Codopony, Child Care and Development Fund Director

Desiree Devine, Comanche Nation Child Development Center – Lawton Manager

Jennifer Kerr, Comanche Nation Child Development Center- Apache Manager

Doah Do Hainta, Kiowa Tribe Head Start Director

Lynn Munoz, Kiowa Tribal Head Start Health Manager

Julie Miller, Lawton Service Unit Diabetes Program Director

Dr. Nancy Collazo, Lawton Service Unit Chief of Pediatrics

Dr. Brian Mauch, Pediatrician

To begin program implementation, WATCH staff have designed a multitude of trainings to enter and collaborate with tribal communities. While this list embodies specific trainings, it is not an exhaustive list and will act as a living document where pertinent trainings can be added depending on the need and will of the community.

WATCH staff and Core External Partner training includes:

CITI Program Training: The Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI Program). This training is in the Protection of Human Research Subjects and consists of modules covering social and behavioral research. It is composed of modules that elaborate on examples and include quizzes as well.

Cultural Competency Training: Weaving Threads of Culture: Working Effectively with American Indian (AI) and Alaskan Natives (AN). This training aims at discovering several aspects of cultural competency that can aid participants in working effectively with American Indians and Alaska Natives.

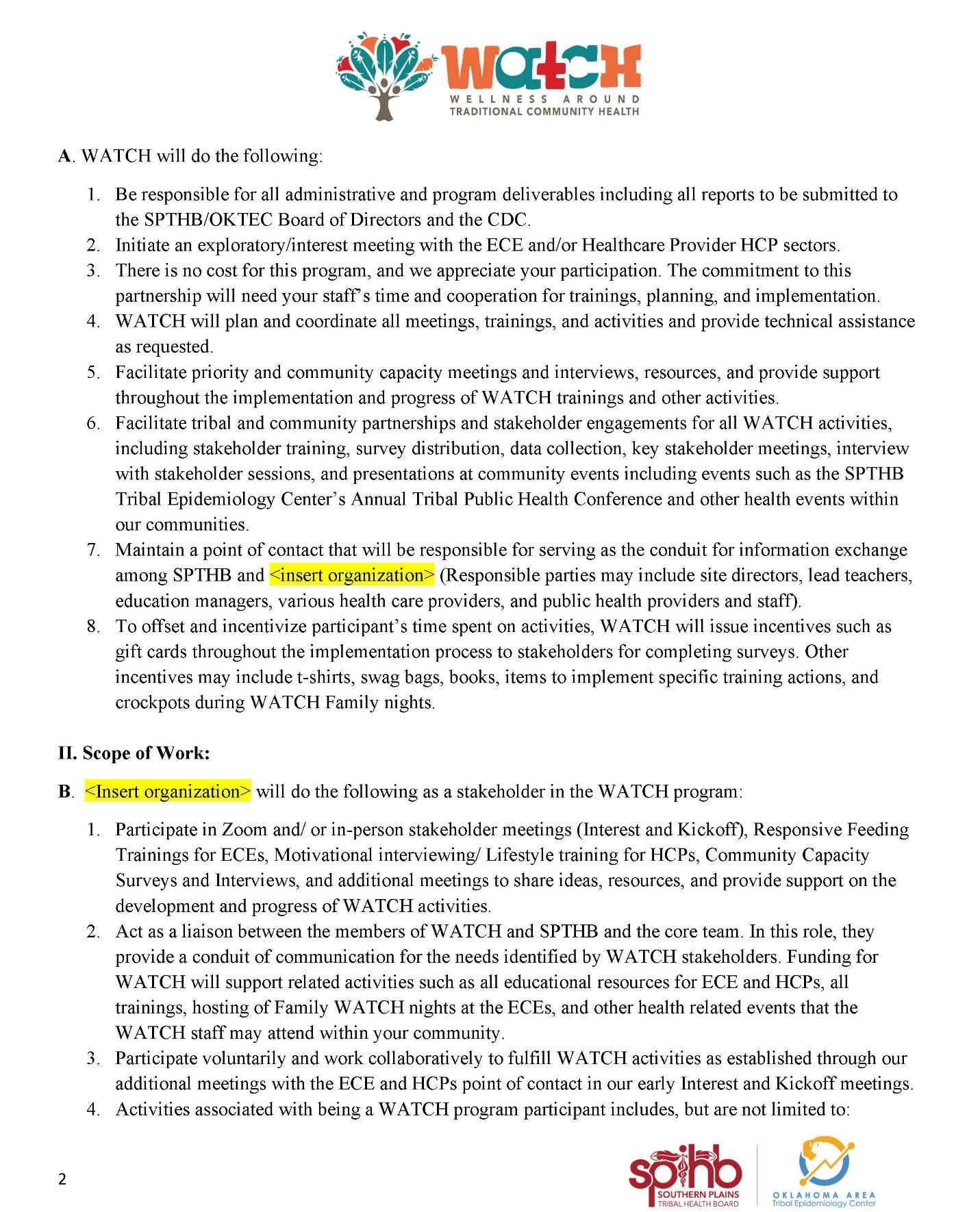

WATCH will reach out to their leadership to create a written agreement (Appendix A: Memorandum of Understanding) that both parties will agree upon when committing to work with a new tribal community. Outlined are what participants can expect from each party from collaboration. Within this agreement, the language used to outline the scope of work to the community partner is displayed with the following responsibilities:

The WATCH Program will:

1. Handle all administrative and program deliverables.

2. Initiate an exploratory/interest meeting with the ECE and/or Healthcare Provider (HCP) sectors.

3. Require no payment; the commitment to this partnership will, however, require time of staff and cooperation for trainings, planning, and implementation.

4. Plan and coordinate all meetings, trainings, and activities and provide technical assistance as requested.

5. Facilitate priority and community capacity meetings and interviews, resources, and provide support throughout the implementation and progress of WATCH trainings and other activities.

6. Facilitate tribal and key community partnerships and engagement for all WATCH activities, including community partner training, survey distribution, data collection, key

partnership meetings, interviews with partners, and presentations at community events, including events such as the SPTHB’s Annual Tribal Public Health Conference and other health events within our communities.

7. Maintain a point of contact that will be responsible for serving as the conduit for information exchange among SPTHB and the participating organization. (Responsible parties may include site directors, lead teachers, education managers, various health care providers, and public health providers and staff).

8. Issue incentives to offset participant’s time spent on activities, such as gift cards throughout the implementation process to community partners for completing surveys. Other incentives may include t-shirts, swag bags, books, items to implement specific training actions, and crockpots during WATCH Family nights.

<Insert organization> will do the following as a community partner in the WATCH program:

1. Participate in Zoom and/ or in-person community partner meetings (Interest and Kickoff), Responsive Feeding Trainings for ECEs, Motivational interviewing/ Lifestyle training for HCPs, Community Capacity Surveys and Interviews, and additional meetings to share ideas, resources, and provide support on the development and progress of WATCH activities.

2. Act as a liaison between the members of WATCH, SPTHB, and the core team. In this role, they provide a conduit of communication for the needs identified by WATCH Community Partners. Funding for WATCH will support related activities such as all educational resources for ECE and HCPs, all trainings, hosting of Family WATCH nights at the ECEs, and other health related events that the WATCH staff may attend within your community.

3. Participate voluntarily and work collaboratively to fulfill WATCH activities as established through our additional meetings with the ECE and HCPs point of contact in our early Interest and Kickoff meetings.

4. Activities associated with being a WATCH program participant include, but are not limited to:

a. Planning, attending, and providing feedback via WATCH interviews and meetings.

b. Assisting with meeting facilitation and presenting, as needed.

c. Providing feedback to enhance current community engagement activities, and evaluation strategies. Feedback will help staff tailor WATCH to meet your needs, concerns, and create opportunities towards optimal child health.

d. Participate in sharing resources with WATCH to align efforts with existing child health initiatives within the community.

e. Regularly attend all WATCH meetings.

Potential communities with tribally operated ECE programs or nearby IHS or tribal health clinics are identified by programmatic staff as eligible community partners. Many considerations are made during the initial selection process prior to community engagement including, previous ECE program interest in nutrition and physical activity programs, existing relationships between WATCH program staff and community leaders in the ECE and health sectors, geographic proximity of tribal health clinic, as well as locations of ECE and health clinic sites.

Once a community has been identified as being a possible partner, an introductory meeting (Appendix B: Documents for Introductory Kickoff and Meetings is scheduled between the WATCH program staff and the community ECE leaders. Prior to any discussions with the health sector, ECE agreement and confirmation of participation is necessary. During the introductory meeting, the project background, history, and development are elaborated. During this meeting, information such as the number of centers, teachers and an estimate of children attending the ECE are collected. A general intervention overview, timeline, and community partner responsibilities are also discussed. The WATCH team looks to understand the current programs context and opportunities and addresses any community questions. Understanding current programs and activities about nutrition and physical activity offered at the ECE, to families, and more broadly in the community is essential. Any ongoing interactions across education and health sectors are identified. Other key community partners are identified as well. Once each community partner agrees to implementation of the program, more individual meetings and emails are exchanged to collect information on existing activities and structural set up of the ECE programs and health clinics. Meetings are scheduled with each community partner in a small group or individual setting to further discuss WATCH.

The WATCH program aims to build on existing structure and success and further integrate education and health sectors. It does not aim to replace or usurp any existing activities or endeavors. WATCH staff can make adaptations and modifications to integrate WATCH into existing initiatives.

A kickoff meeting (Appendix B: Documents for Introductory Kickoff and Meetings is scheduled with all the health and education center partners to discuss the specific timeline, expectations of community, accountability of WATCH program staff, and to begin to develop relationships across sectors. Again, the global program implementation is shared with the collective group and there is ample opportunity for individuals to ask questions on sector-specific or integrated

components. Discussion on specific requests needed by WATCH program staff is collected and followed by scheduling conversations for the respective sites. At these meetings, a primary point of contact for each center is identified. This group commonly ranges from lead teacher to education manager, site manager or to clinic director. At this time, a Letter of Support (LOS) (Appendix C: Letter of Support is requested from each of the health sectors and a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) from education centers. Once these documents are complete, they are submitted to OUHSC IRB.

Upon approval of the documents, a plan at each of the community partner locations is set in motion to train staff prior to implementation. To achieve maximum staff attendance, ECEs are asked when and if they have in-service training already established to aid in the scheduling of training. WATCH program staff then plan the collection of preintervention baseline measures. Due to COVID-19, all observations in the ECE have been adapted to self-report EPAO (EPAO-SR). To introduce menu assessments and implementation of best practice menus, an additional meeting is scheduled to discuss with directors, center managers, and cooking staff.

Prior to implementation in ECEs and medical centers, WATCH program staff distribute teacher assessments for baseline measures and will collect the same EPAO-SR after the 16th week and final week of implementation.

A graphic to illustrate the training schedule and timelines was created for general meetings and distributed to all associated partners. This graphic is shared with participating partners to aid in the depiction of program implementation within the context of a school year. Figure 5 is used during Kickoff meetings and is updated to the current community’s timeline.

After confirming with each partner within the community, we can schedule the following meetings:

introductory & kickoff meetings, training for the partners, follow-up meetings, and training for the cooking staff and site directors. These are to implement the best practice menu and collect pre- and postbaseline measures. All scheduling is initiated and completed by the program coordinator and aided by the public health specialist. Scheduling for measurements and intervention will vary based on partner availability and response time.

Site visits are scheduled with the site directors. After the introductory meeting is held, the program coordinator stays in communication with the site director or designated WATCH contact to ensure timeliness and information about the intervention that is provided throughout the implementation process. Scheduling is dependent on when it is convenient for the community partners. Before going to sites, it is important to gather location information and contact phone numbers prior to the first visit. Follow-up meetings are scheduled as needed.

Participation in the evaluation measures occurs across multiple ecological levels. Measures are collected from ECE directors (Appendix D: Director Packet Documents, ECE teachers (Appendix E: Teacher Packet Documents, and parents (Appendix F: Parent Packet Documents. The purpose of collecting evaluation measures is to improve upon implementation in real time based on community partner feedback, technical assistance requests, and evaluation forms. ECE teachers that provide program evaluation on their knowledge, attitudes, and experiences with health care providers and families will be provided financial incentives. Families of children ages 3-to-5 years old who take part in the program evaluation will be provided financial incentives for completing surveys. Families that attend and take part in the family event will also receive financial incentives by qualifying to enter a drawing for goods that support healthy lifestyles, such as crock pot giveaways at family nights, gift cards to local grocers, physical activity equipment, and small kitchen appliances. Depending on the community partner, different evaluation forms are used and have different timelines.

The Parent WATCH night is an opportunity for community engagement for the parents of the ECE children to interact with various aspects of the WATCH curriculum. Healthcare providers are invited to the parent WATCH nights as well as all participating ECE parents, staff, and families regardless of site. Activities can include healthy cooking food demonstrations, ways to improve physical activity at home, and ideas to increase nutrition of family meals at home. Scheduling is based on preexisting family meeting times within the site’s semester.

WATCH conducts community partner training prior to the intervention implementation for ECE and medical providers in each community. The training provides education and methods to increase healthy behaviors among the ECE and Health center environments.

Training for teachers begins ideally in the early Fall semester and will include the distribution of curriculum materials so that teachers can get acquainted with the new curriculum and can troubleshoot any issues prior to implementation. ECE teachers and staff receive training on the OrganWise Guys curriculum with WATCH staff. They will implement this curriculum over 16 weeks. This orientation is scheduled prior to Week 1 of implementation. The ECE staff will also complete Responsive Feeding training with Dr. Dipti Dev. The Responsive Feeding training includes learning the EAT family style methods through modules and structured interactive lessons. Each training time will range from 1-4 hours.

The WATCH staff conduct an orientation to the OrganWise Guys clinic materials specifically for the healthcare providers. This training will typically last 4 hours. Additionally, the medical provider community receives and completes obesity sensitivity training, motivational interviewing, and clinic efficiency training with Dr. Ashley Weedn.

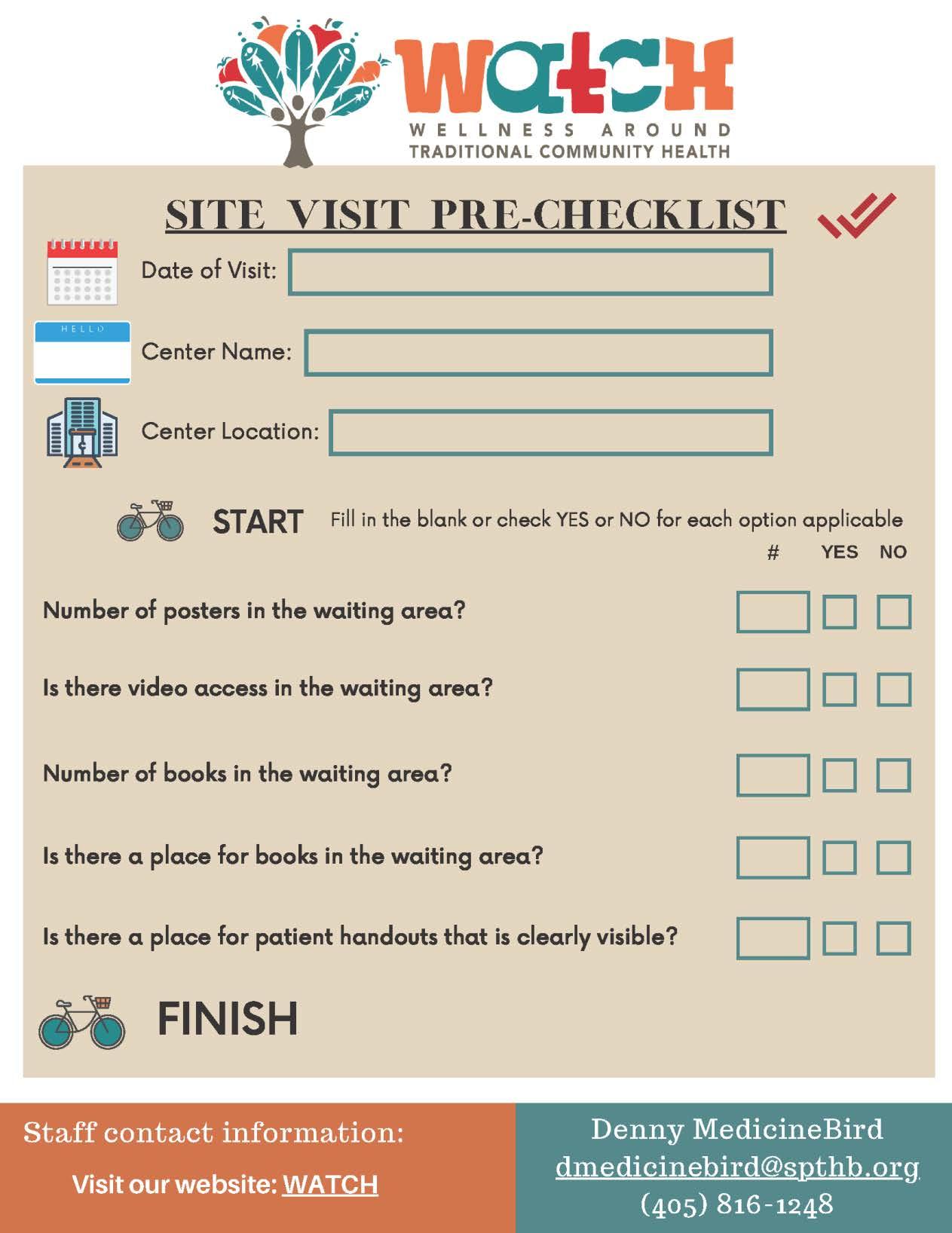

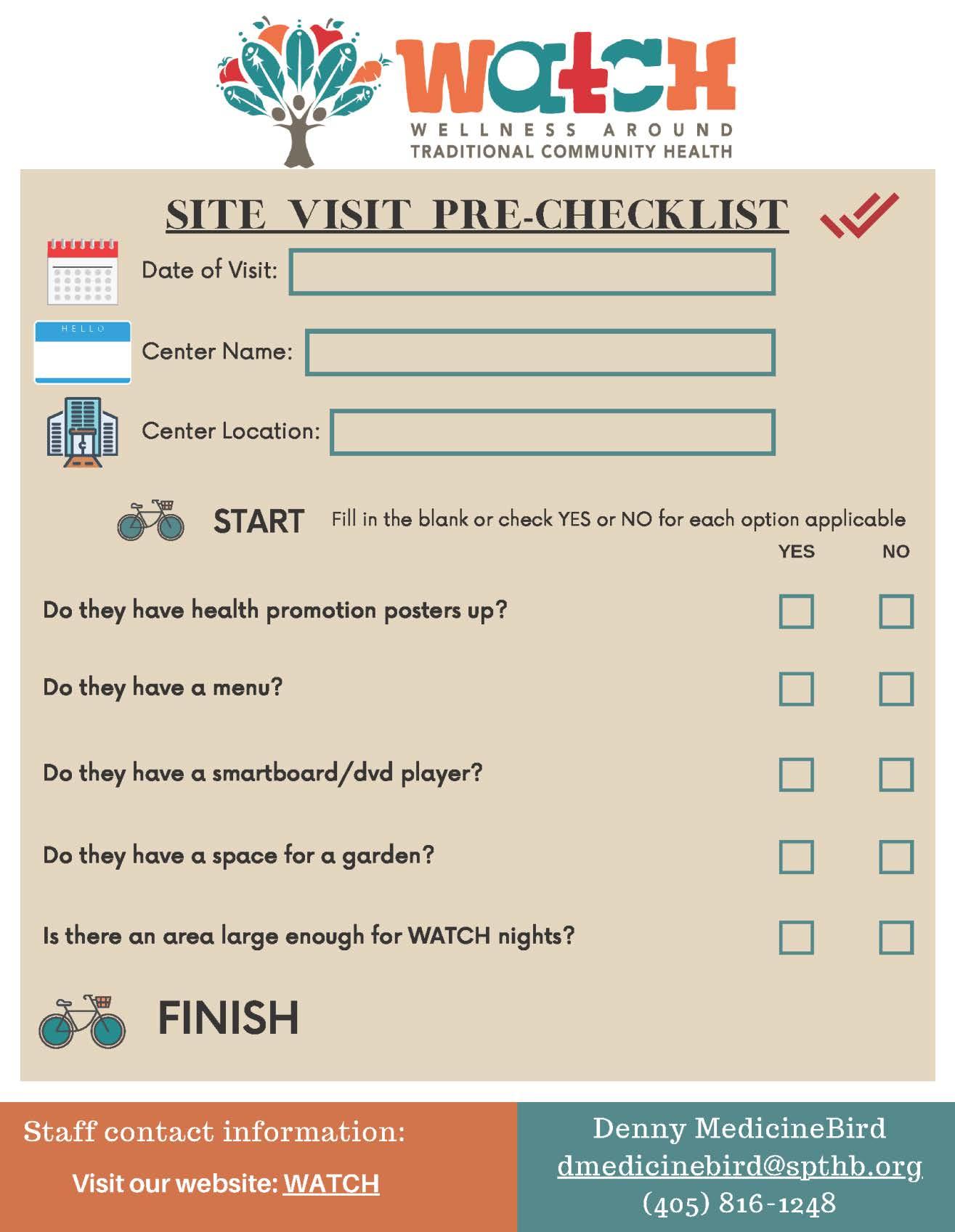

A site visit will consist of touring the facilities for the first time and can include an in-person introduction or meeting with community partners. If a site visit is being conducted, information to be collected may include visual inspection of capacity for health promotion signage that reinforces healthy eating and physical activity. This information will be recorded in the Site Visit Checklist for Tribal Clinics, ECEs and Food Prep Area. While in the field, participant safety is the top priority. If anything, unsafe is seen, notify program coordinator and/or the site director immediately. Staff may wear jeans and a SPTHB/WATCH Logo shirt. Staff strive to build positive relationships with the community partners and give each partner the highest respect. While in the field, always remain courteous and patient.

All personal belongings will remain on person. Leave other belongings in your locked vehicle where they will remain safe. After leaving the field and returning home or to the worksite, please give all materials to the Program Coordinator or Public Health Specialist if they are not present. This will ensure safety and secure storage of all data and materials.

The three site visit checklists (Appendix G: Site Visit Checklist represent the visual inspection within the designated areas. A site visit checklist will be conducted before implementation as a pre-site visit and after implementation as a post-site visit. The only site which will have only one site visit is the Food Prep Area to accommodate food prep for best menu practices.

Once communities are recruited into the intervention, they will be scheduled for evaluation measures before the start of the intervention. Clinic data and health care provider self-reported measures will be collected. ECE Director and Teachers will self-report their environment and children’s dietary intake and menus will be analyzed. Self-report measures from teachers will also be collected. Families will complete survey measures on family health behaviors.

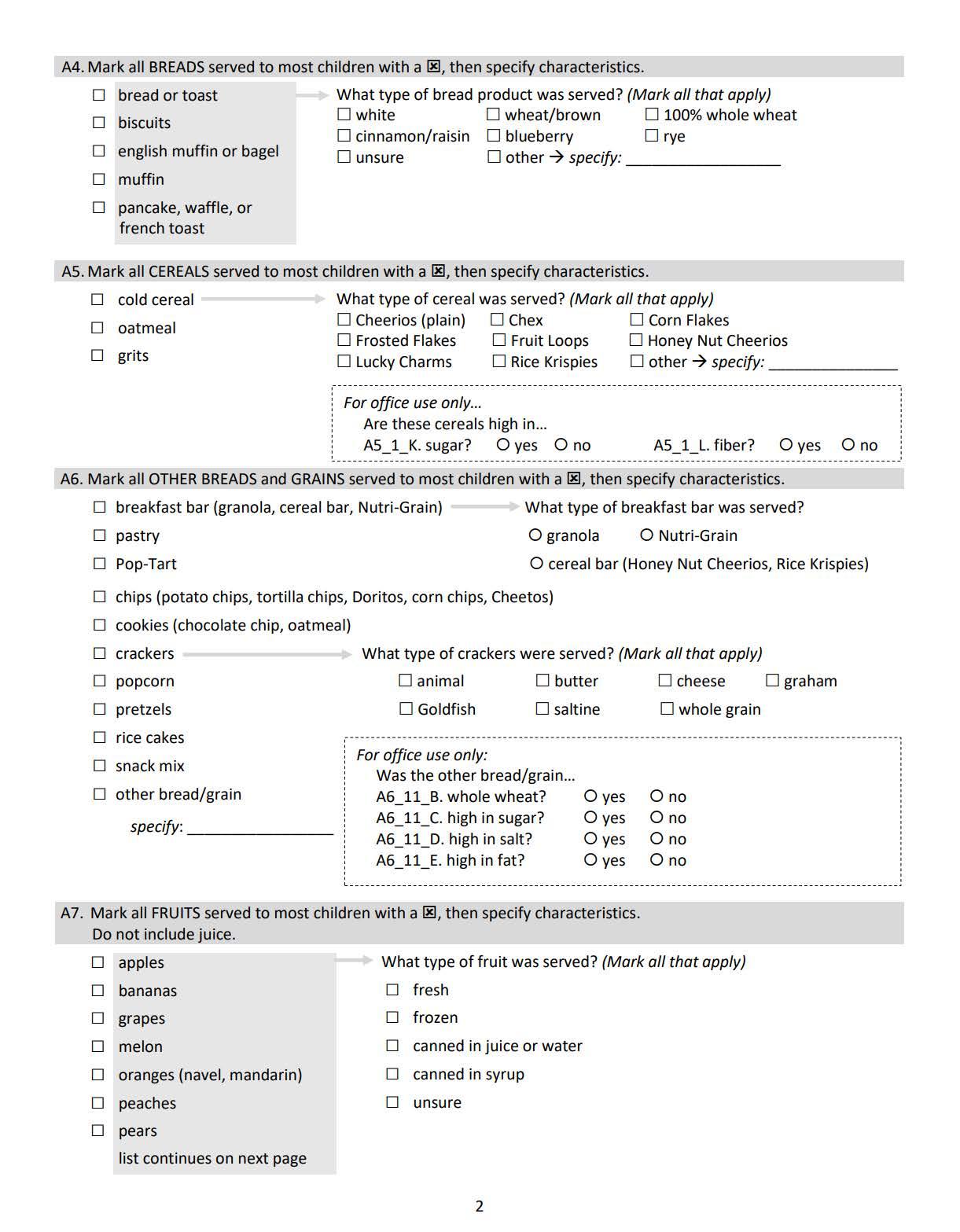

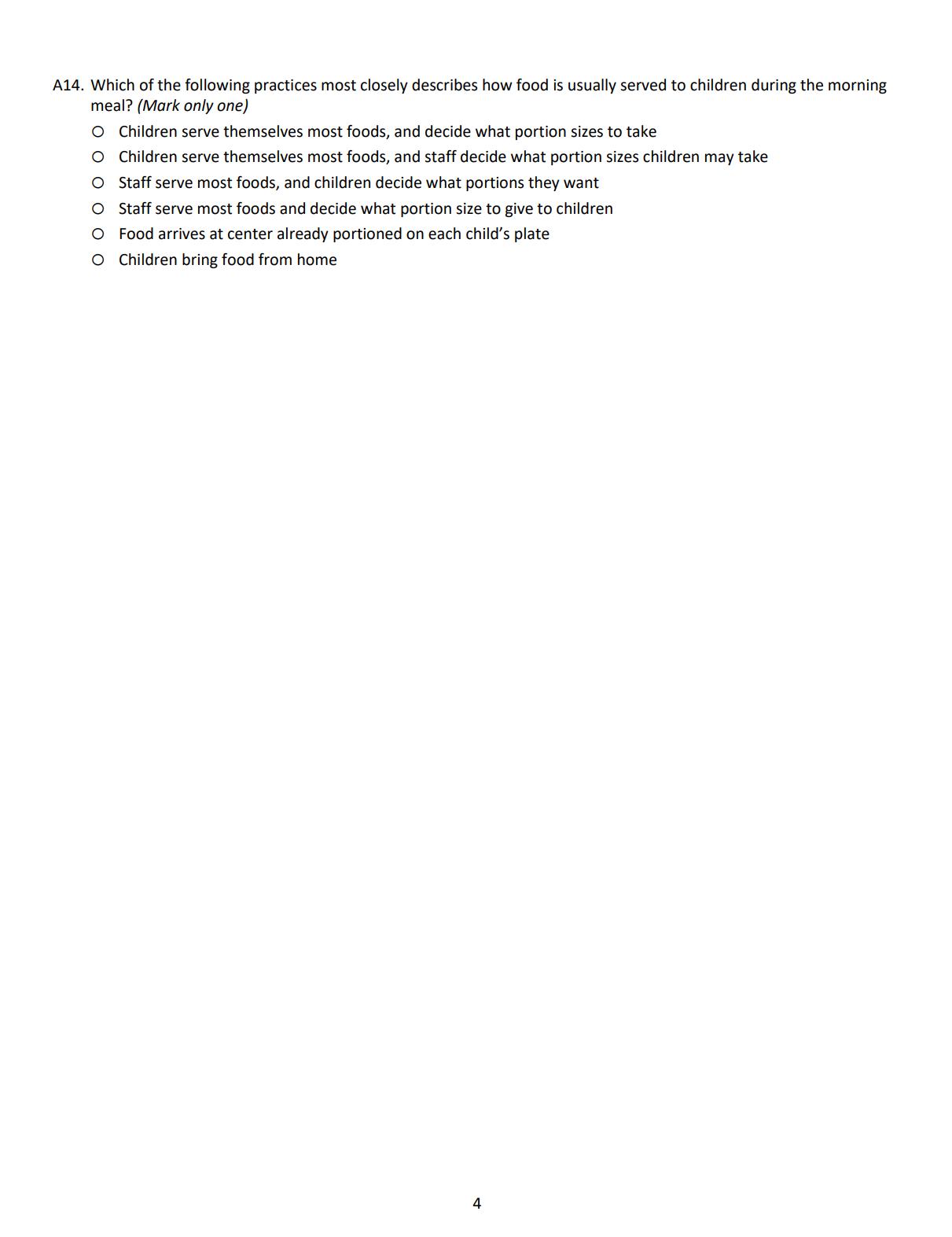

ECE partners will fill out a demographic sheet included in their initial survey packet. These forms will help our staff understand the characteristics of our community partners and their sites as well as create descriptive factors for each.

The packet that Directors and Teachers receive are all self-report measures, and distribution and collection of these measures will be coordinated with each site. Measures included in packets are:

Director Packet Documents

• D.1 Demographic Survey for Directors

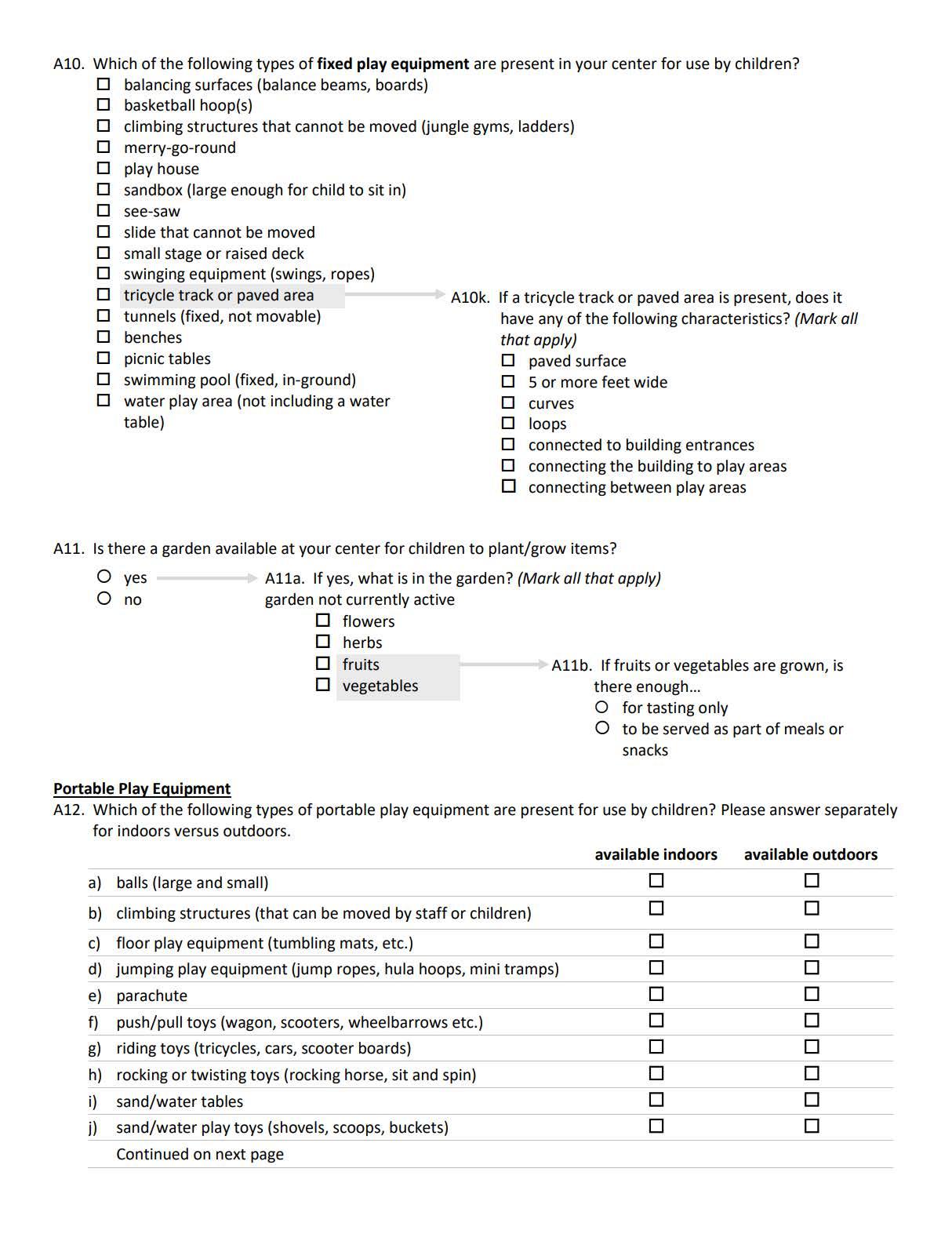

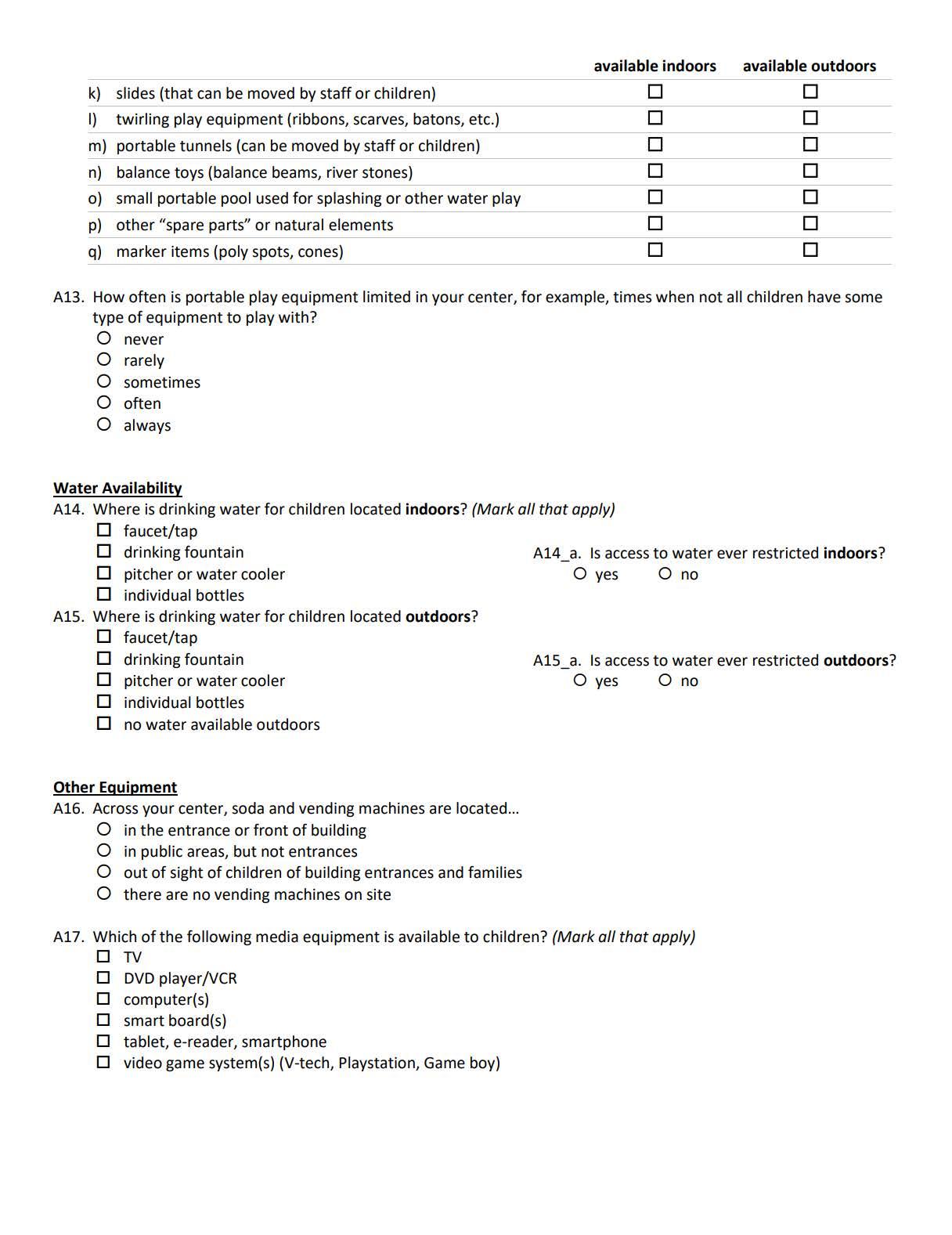

• D.2 EPAO SR for Director General

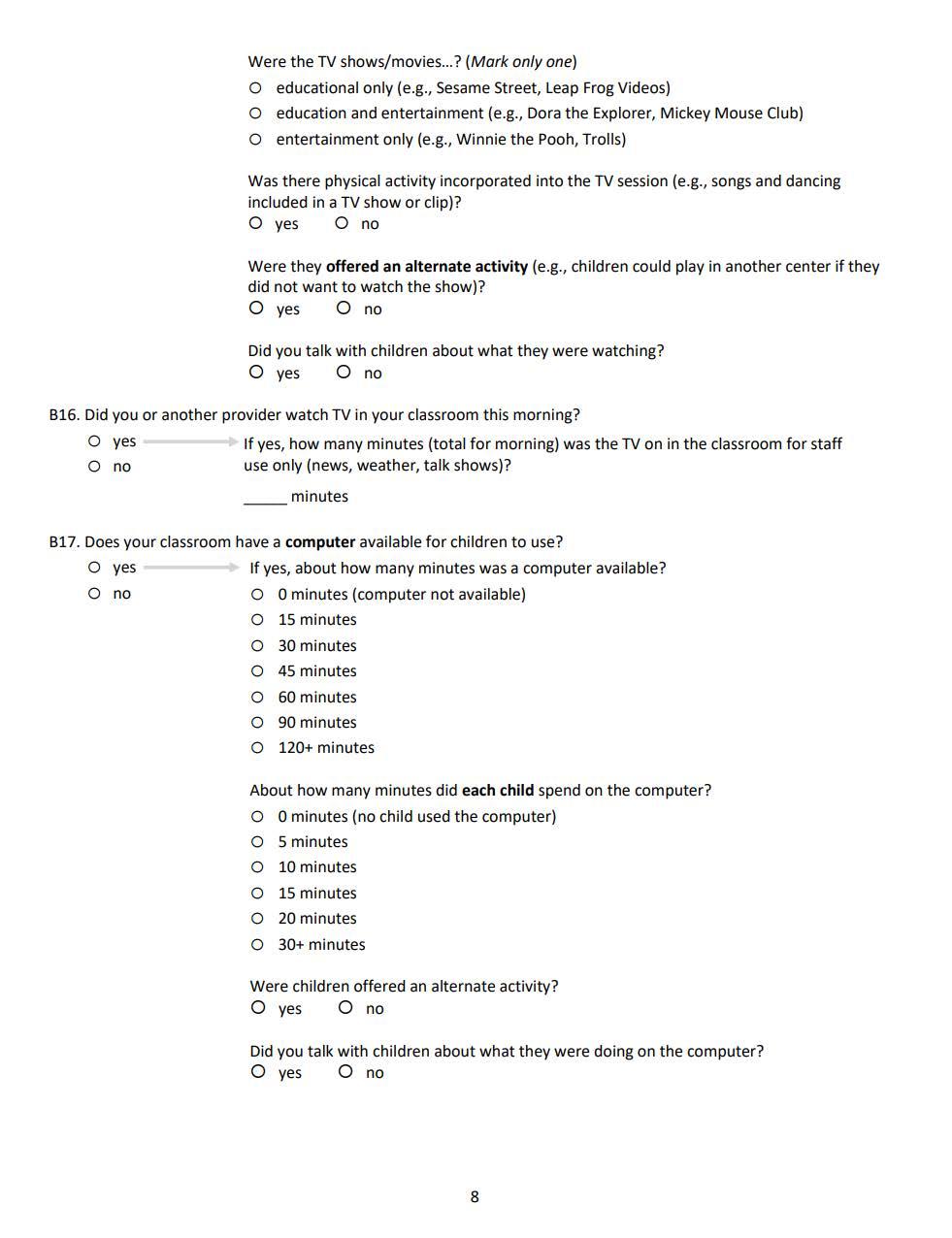

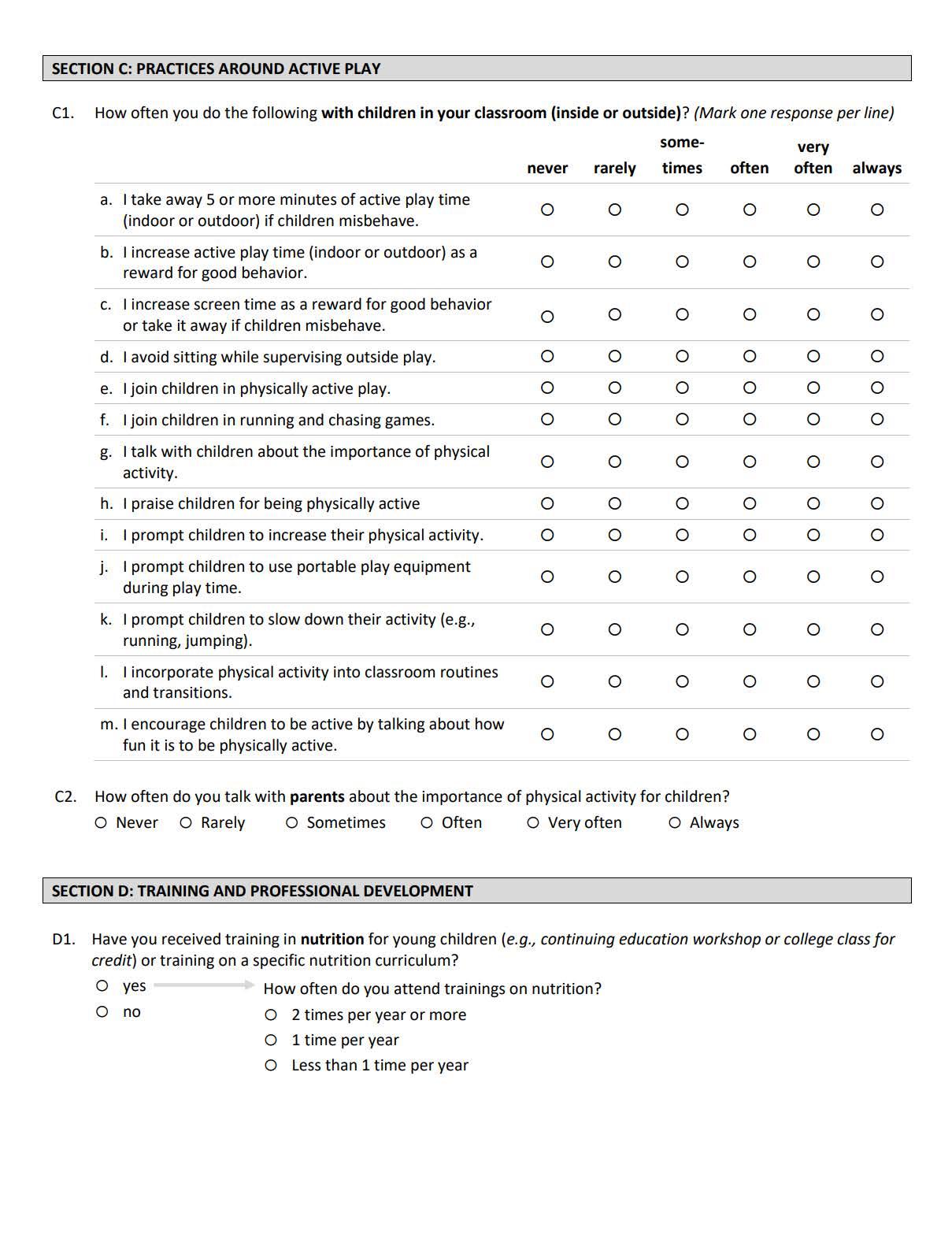

Teacher Packet Documents

• E.1 Demographic Survey for Teachers

• E.2 EPAO SR Staff Daily

• E.3 EPAO SR Staff General

Teachers and staff level will conduct a self-report observation of the ECE for infrastructure and teacher support of obesity prevention behaviors using the validated 174-item Revised Environmental and Policy Assessment Observation (EPAO) (EPAOS SR).98 Menus will be obtained and analyzed during conversations with the Director and Cook throughout the community capacity building process. Consistent with previous studies, we will examine 1 week of meals and input serving size to minimum licensure-required serving, if needed.

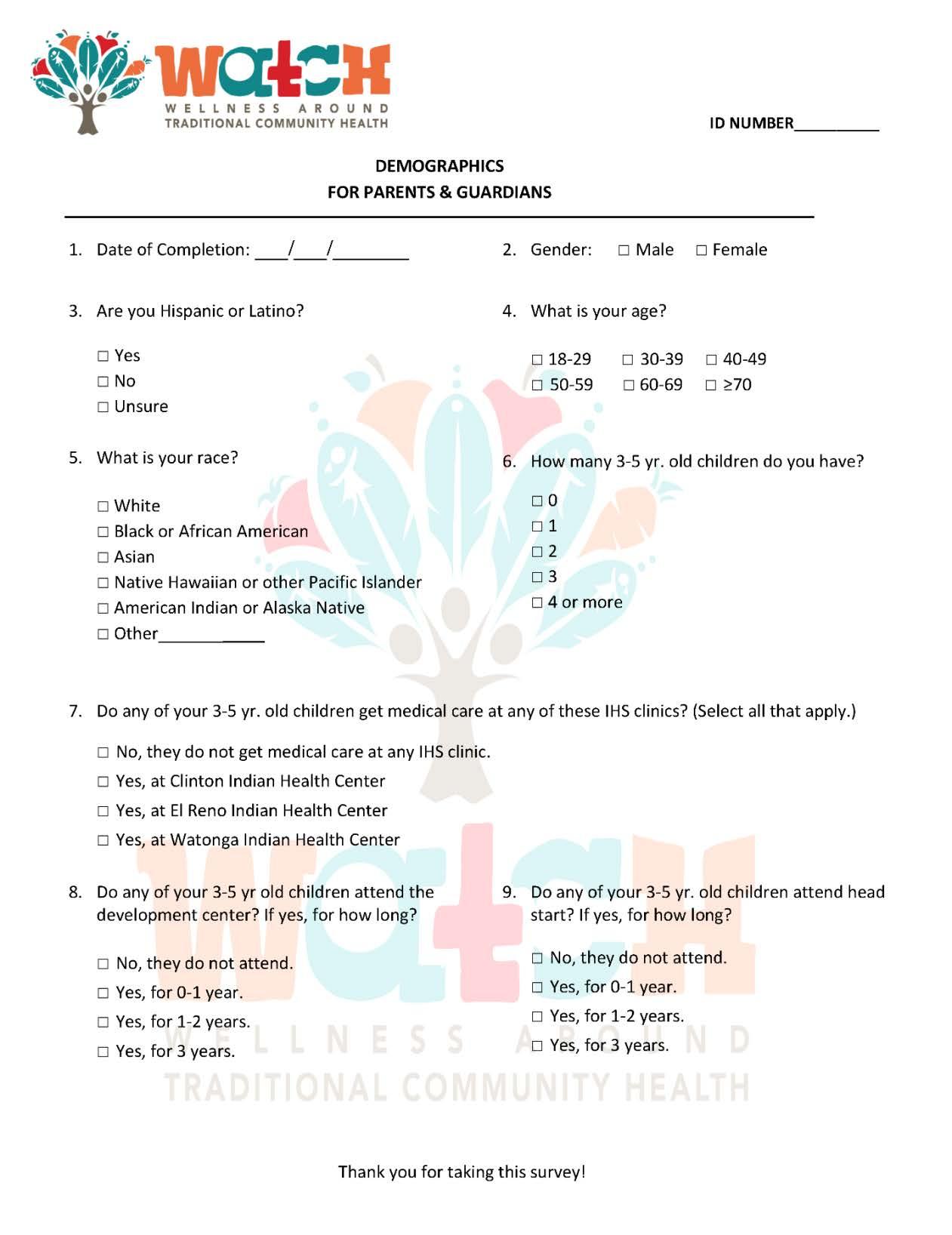

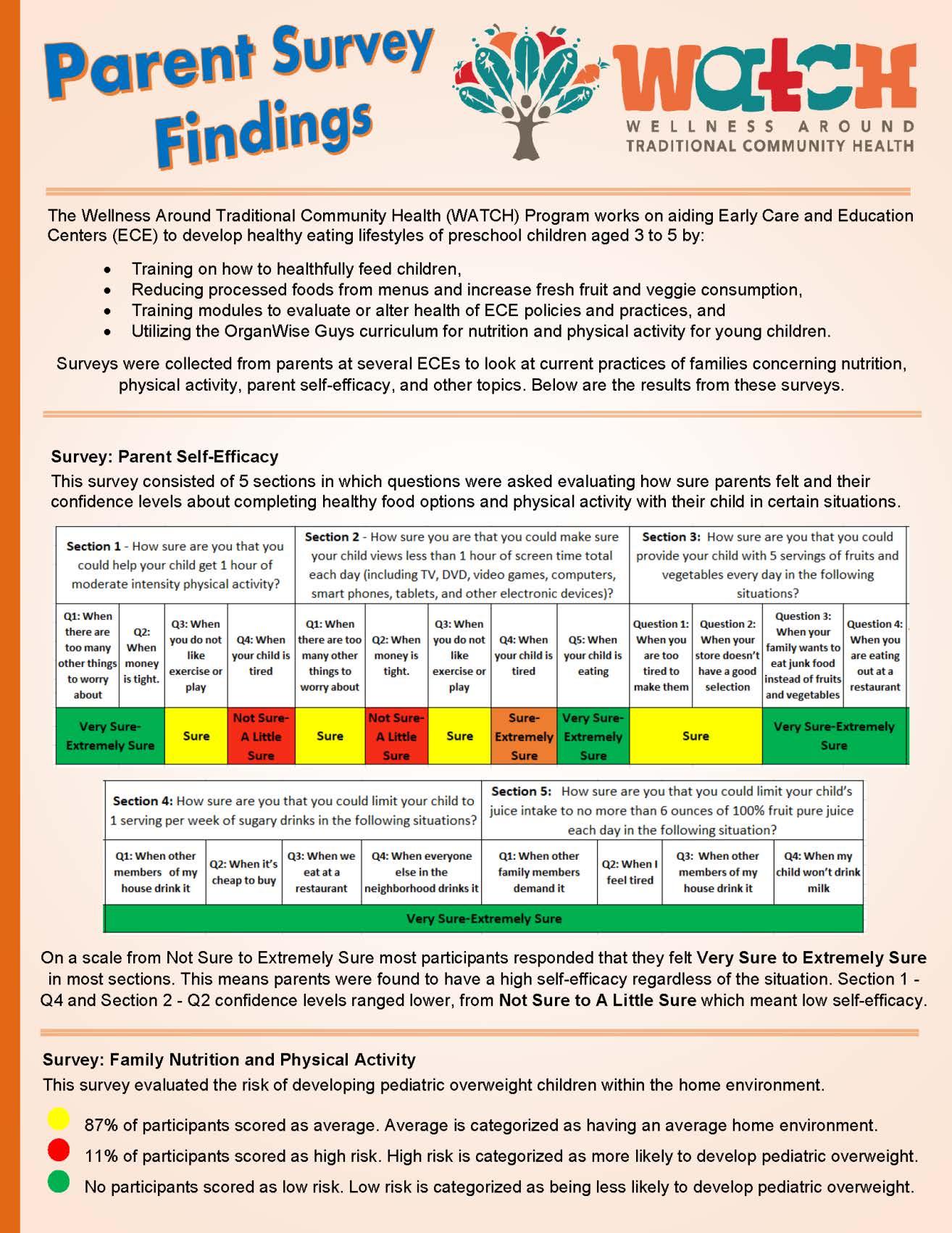

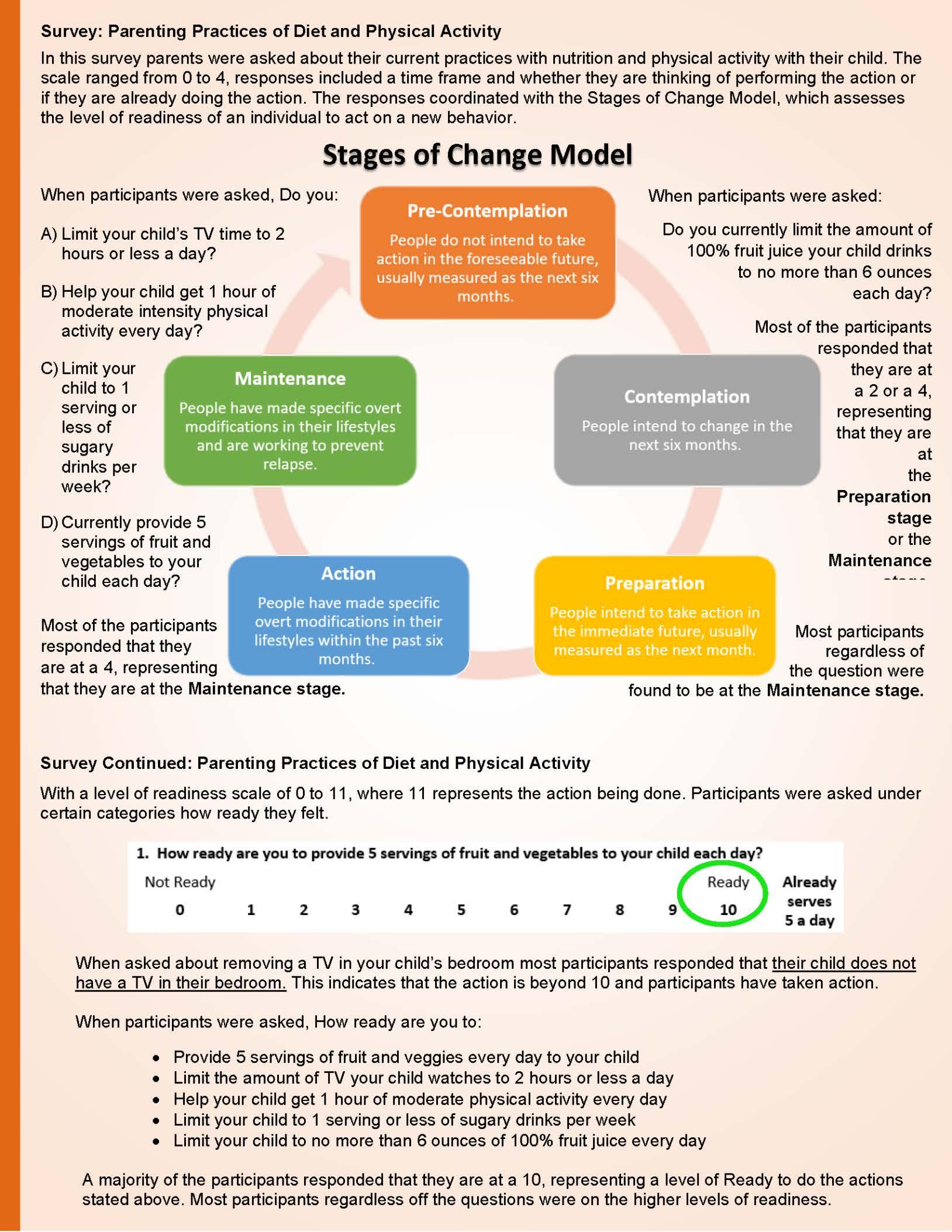

Parenting Practices of Diet and Physical Activity Parents will report on family obesity prevention behaviors using the 20-item Family Nutrition and Physical Activity Screener (FNPA). There are 10 subscales of the FNPA which are all related to specific family practices, as well as a total score of the survey. Constructs are significantly correlated with total score in (0.32-0.66, p<0.01), and family meal patterns significantly correlated to overall score (0.532, p<0.01) and screen time to overall score (0.32, p<0.01).99

• F.1 Demographic Survey for Parents and Guardians

• F.2 Parenting Practices of Diet and Physical Activity

The following measures listed below are intended to be distributed for data collection at specific time intervals. As stated above, the site visit checklists are conducted before and after implementation except for the food prep site visit; they will only receive one prior to implementation. Process evaluations and surveys begin the very first day of implementation of curriculum. Within ECE’s the teachers will receive a weekly survey over the 16 weeks and the healthcare providers will receive one monthly over the course of the implementation.

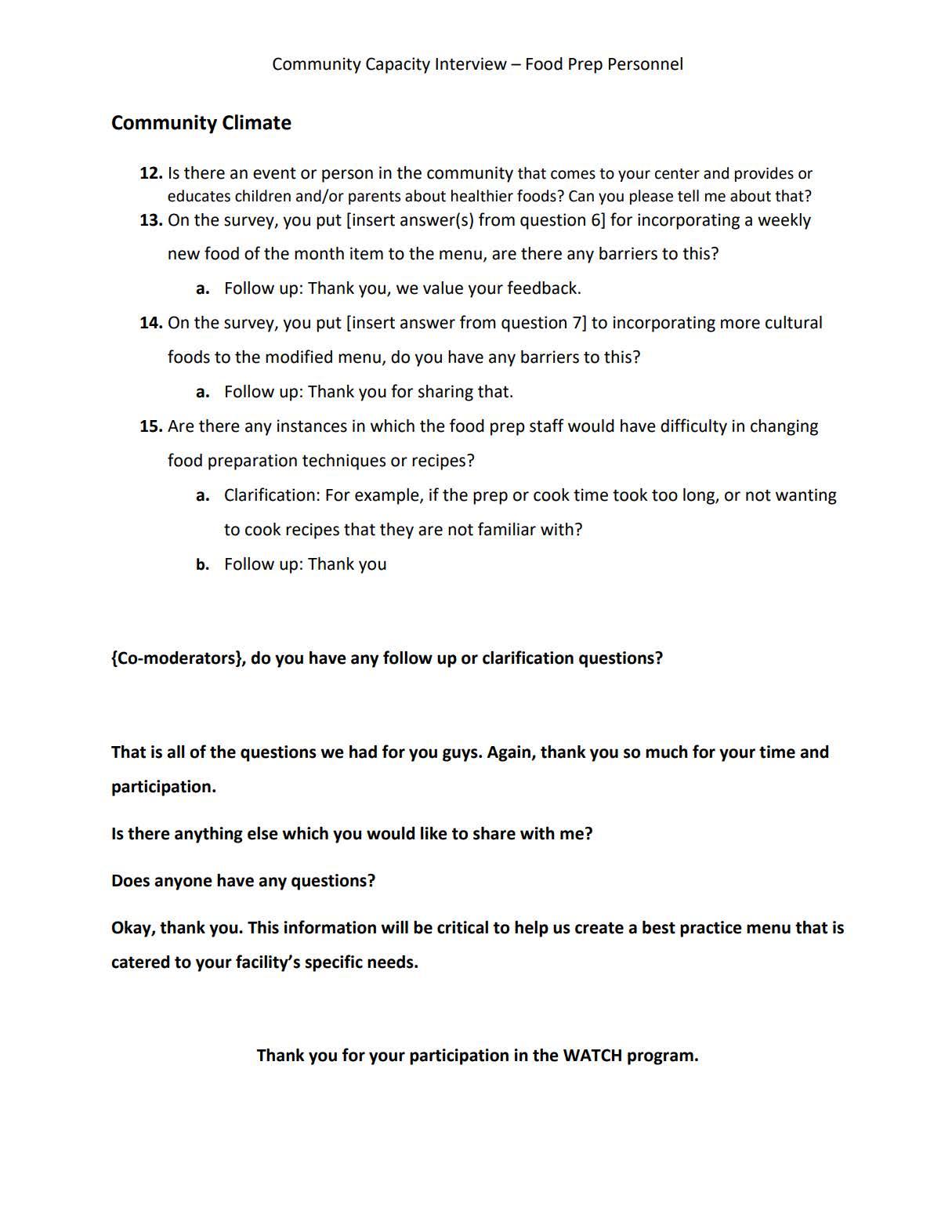

The community capacity tool is used prior to implementation to gauge readiness among our community partners. For food prep personnel, it is intended to develop a best practice menu before the first day of school. For teachers this is intended to gather information about physical activity lesson plans, establish or continue cultural and traditional practices related to nutrition and physical activity, and learn about community engagement of parents and healthcare providers within their respective community. For providers it is intended to collect information about current cultural practices within their healthcare setting, community outreach, and current physical activity and nutrition information or resources provided to parents. The interviews for each partner are a follow-up to the community capacity survey and provide time for them to give in-depth feedback.

The menu feedback form is to gain insight from the food prep personnel about utilizing the best practice menus. With this feedback WATCH staff can provide technical assistance and address the topics within the form. This can include troubleshooting about what snacks and meals concern them, what menu items they are enthusiastic about, and how well it is being received

by children. This form initiates communication and establishes a regular monthly check-in about best practice menu principles.

HCPs:

• G.1 Site Visit Checklist for HCP’s- Pre

• G.2 Site Visit Checklist for HCP’s- Post

• H.1 Process Evaluations for HCP’s

ECE Centers:

• G.3 Site Visit Checklist for ECE’s- Pre

• G.4 Site Visit Checklist for ECE’s- Post

• H.2 Teacher Weekly Process Evaluations

Food Prep Personnel

• G.5 Site Visit Checklist for Food Prep Personnel- Pre

• I.1 Community Capacity Survey for Food Prep Personnel

• I.2 Interview for Food Prep Personnel

• I.3 Menu Feedback Form

Teachers and Directors

• I.4 Community Capacity Survey for Teachers and Directors

• I.5 Interview for Teachers and Directors

This tool (Appendix J: Go NAPSACC is used as an environmental scan of Child Nutrition and Infant & Child Physical Activity within the ECE. This is a scan which the director can fill out online. The results are then populated so WATCH staff can act as consultants to the director of each ECE and work toward action plans and goals that will improve identified areas of need. The self-evaluation tool guides programs participation in the Go NAPSACC training. The online modules also share how to improve and go beyond the results to show how to make adaptable changes.

• J.1 Go NAPSACC Child Nutrition

• J.2 Go NAPSACC Infant & Child Physical Activity

• J.3 Go NAPSACC Outdoor Play and Learning

• J.4 Go NAPSACC Screen Time

Food and nutrition practices and staff behaviors using the Nutrition and Physical Activity SelfAssessment (NAPSACC).100 Dr. Sisson has used the NAPSACC state-wide.101 The NAPSACC has been validated,102 used in numerous ECE Programs,69 and is expected to take 10 minutes to

complete. Key items of interest include frequency of encouraging physical activity and reduced sitting and role modeling fruit and vegetable consumption.103

When engaging with community partners, specifically the ECEs, staff refer to the WATCH Conceptual Model. This model guides the overall implementation and serves as a base to introduce specified changes within the classroom and the menu modifications. In the classroom and healthcare centers, OrganWise Guys curriculum is given to provide resources related to nutrition and physical activity.

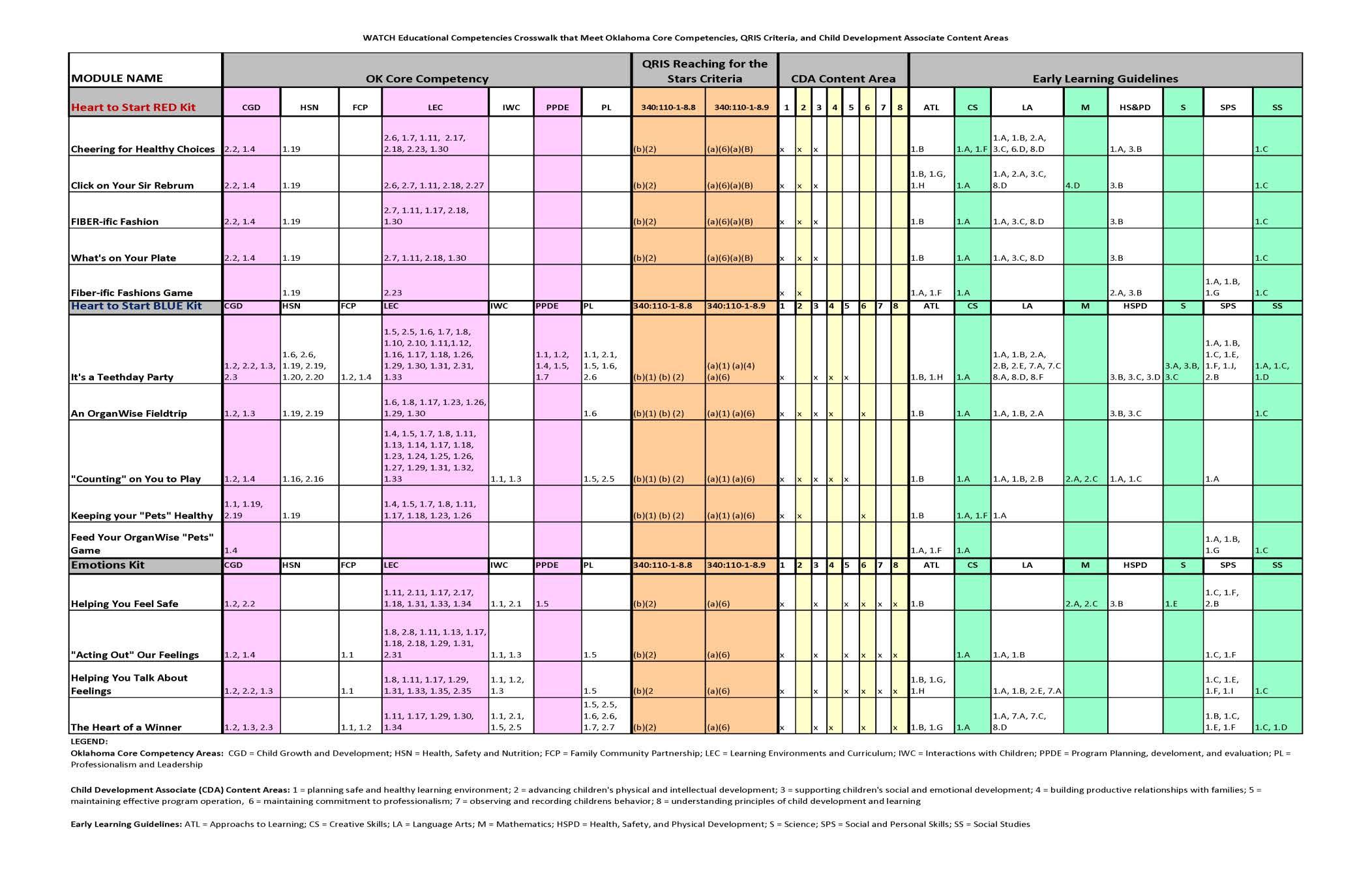

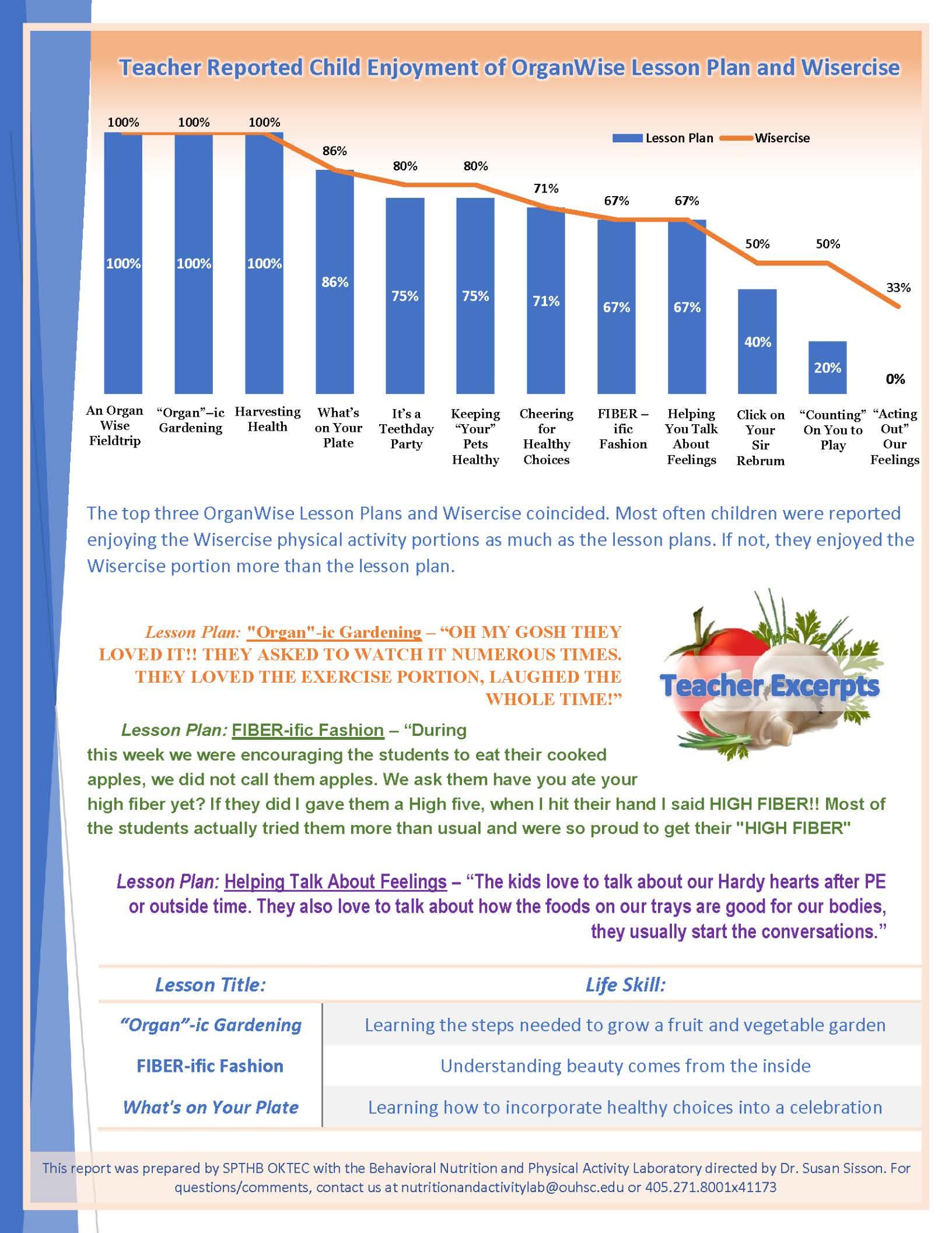

The Educational Competencies Crosswalk (Appendix K: Educational Competencies Crosswalk was developed to show teachers how the OrganWise Curriculum will fit into their existing lesson plans. The OrganWise Guys curriculum was selected to be a component of WATCH because of its best practice in preventing childhood obesity. The eight lessons and videos that each classroom receives aligns with the Oklahoma Core Competencies, Quality Rating, and Improvement System (QRIS) Reaching for the Stars criteria, Child Development Associate (CDA) content, and Early Learning Guidelines. These areas highlight the importance for early childhood development and each lesson promotes the enhancement of healthy nutrition and physical activity within each learning center. (Figure 9 - OWG Intro for meetings)

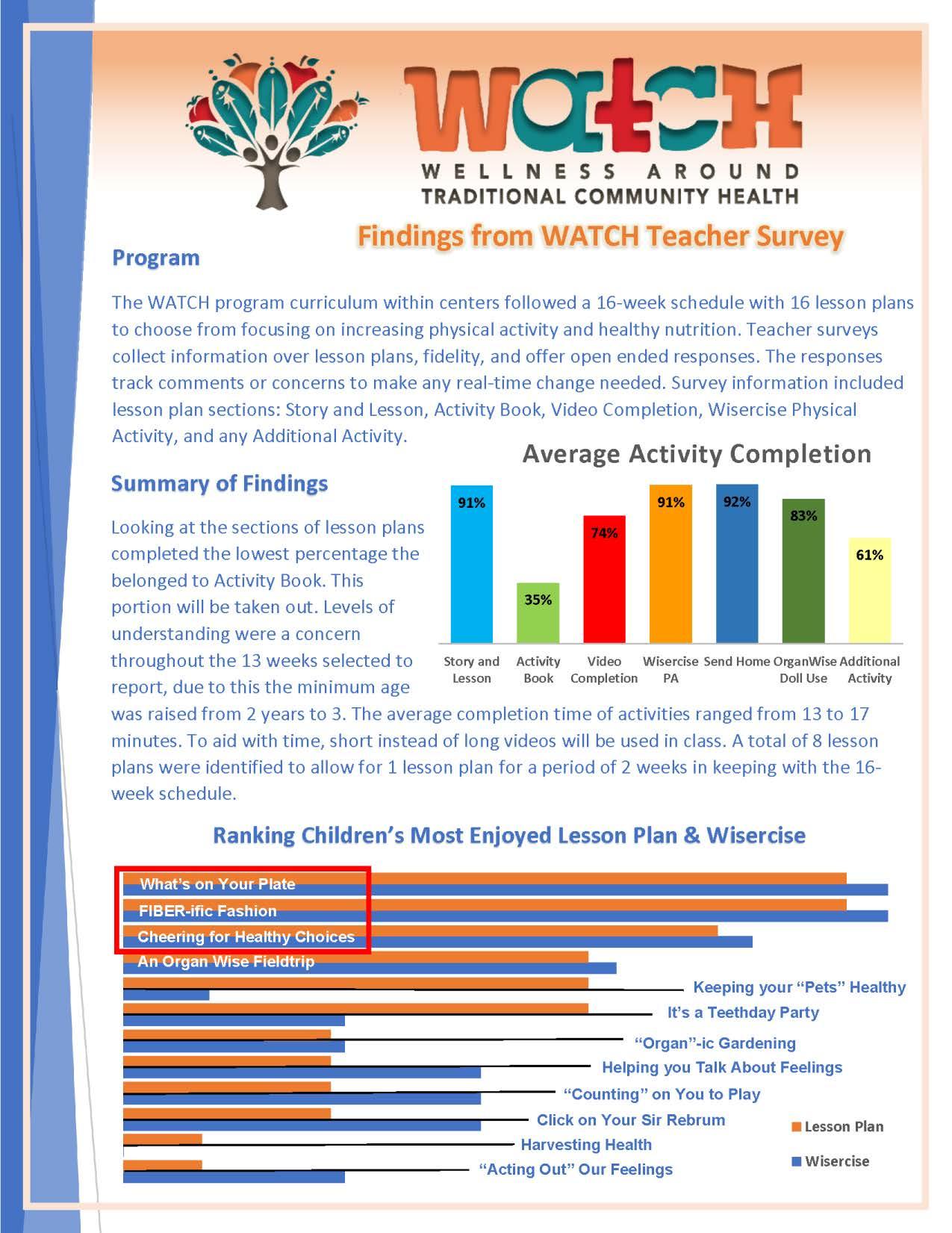

Each ECE center will receive an OrganWise Guys curriculum kit. Each kit has two components, the Red kit and the Blue kit. Collectively, they make up the 8 OrganWise Guys lessons. Each classroom is expected to focus on one lesson for the duration of 2 weeks to allow ample time for content. WATCH staff work with teachers at the ECEs to implement these lessons over their 16-week semester.

These lessons also have an accompanying video, book, and Wisercise activity completed within the classroom. Teachers also have the Foods of the Month newsletter and activity sheets that are sent home. Supporting materials include the activity books, activity sheets, stickers, a physical activity calendar, posters, and a Wisercise book. One of the more well received materials included in the kit is the OrganWise Guys doll, that has caricatures to represent organs of a healthy body. The kit also includes foods of the month materials which have a newsletter, temporary tattoos, buttons, and stickers. (

Figure 10 - OWG Lesson Plan)

Figure 10 - OWG Lesson Plan

Another part of implementation of the curriculum includes a Weekly Process Evaluation for teachers and teacher assistants. These are brief weekly surveys scheduled across the 16-week semester. These surveys allow the teachers to provide feedback in real time and give WATCH staff the opportunity to provide technical assistance. This also serves as a link to open communication between WATCH staff and ECEs. This communication is vital to making on the spot corrections to tailor the program to meet the specific needs of the communities.

Best practice for menu modifications is initiated with the results from the community capacity survey for food prep personnel to gauge readiness. From these results, staff can use the survey to prepare for the interview to learn more about feasible implementation of menu modifications. During the interview, a review of the current menu will look at what foods have been successful, favored recipes, and identify what menu items to keep or modify. This is followed by menu analysis conducted by the WATCH programmatic assistant following the CACFP guidelines to create a new menu. The new menu is sent for review to the food prep personnel for review and approval. A menu feedback form I.3 Menu Feedback Form is initially used after the first month of menu modifications to assess utilization and feasibility. After the first assessment is completed if further edits or changes are needed, it can be discussed through the established monthly check-ins. The menus are created for a three-month cycle that incorporates a “Try it Tuesday” Food of the month and Traditional Thursday food item or meal. The purpose of “Try it Tuesday” is to incorporate the food of the month for children to taste and learn about the specific food item.

Traditional Thursday is a concept about bringing opportunity for children to try traditional foods during mealtimes at each center. Including this to the menu encompasses adding traditional foods specific to the tribal community and area of which the learning center is located. Staff will be working with parents and families to engage communities to be involved and gather input about what traditional foods are to them and how they would like WATCH staff to incorporate them at the learning centers. While some ECEs may be in a specific tribal jurisdiction, we aim to be inclusive of all tribes within the area. This effort is focusing on wellness and traditional health, which embodies what WATCH is.

The WATCH family nights are interactive nights planned throughout the semester which are coordinated with already established ECE parent teacher nights. Each night is designed to promote the NIH’s Eat, Play, Grow curriculum. Components from the OrganWise Guys curriculum are utilized when planning each event. One night is dedicated to a specific theme

which can be physical activity, nutrition, or a food demonstration. The duration of each night depends on the established agenda and can vary due to planned activities and housekeeping.

For the food demonstration an indigenous chef is invited to prepare a meal for families to sample a healthy recipe. These nights are meant to be interactive and introduce families to both aforementioned curricula. It gives staff time to show parents what the kids are learning at school. This will give families a better representation of what children learn at school and continue learning within the home.

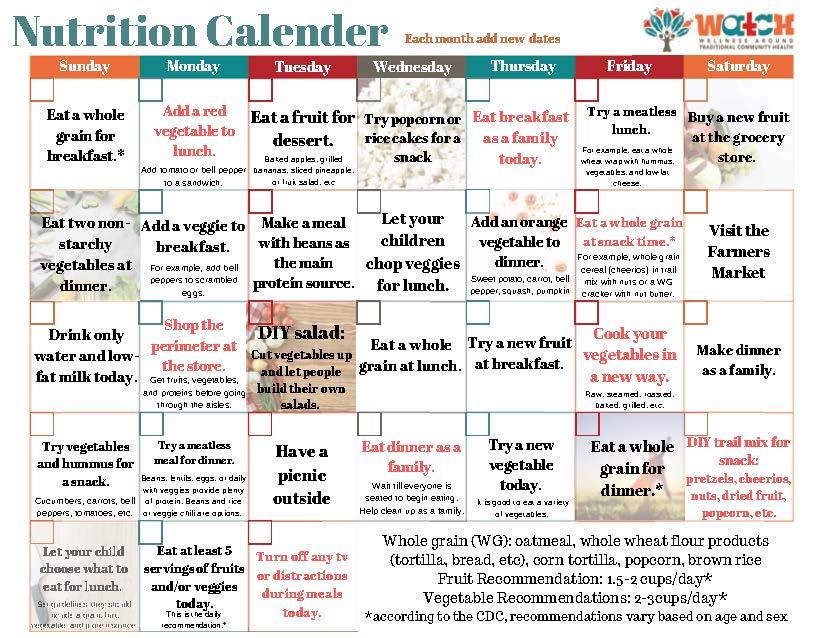

In the beginning of the night, families are provided a toolkit, which can be found on our website. The toolkit given to the families includes two different laminated calendars that allows the parents to engage daily with the child. The Physical Activity Calendar (Figure 11 - Activity Calendar) provides easy and fun exercises with a goal of being active for a total of 15 minutes a day as a family. The Nutrition Calendar (Figure 12 - Nutrition Calendar) offers ways to add in healthy choices based on the child's age. The toolkit contains guides for being safe outdoors, activities for small spaces, information on how to be cost-effective with a slow cooker, and a gas station and dollar store guide for selection of healthy foods. Other materials included are a physical activity book for families to read to their children and healthy recipe notecards. At the end of each night, there is an incentive raffle for participation which includes the opportunity to win a crock pot and gift cards. These activities provide a unique interaction to involve WATCH community partners and encourage healthcare providers to attend the family nights as allowed. Figure 11 - Activity Calendar

After healthcare providers have established their participation and given a letter of support, staff can begin planning activities based on their capacity. The next step is to gather feedback from the providers through open communication which asks about cultural centered care, materials that encourage physical activity or nutrition, and where WATCH can fit within their clinical setting. After this feedback is collected, providers are given Dr. Weedn’s training focusing on motivational interviewing, obesity sensitivity, and clinic efficiency.

The purpose of the healthcare provider training is to bring innovative ways to the health care providers to talk about their pediatric patient’s healthy weight through methods of motivational interviewing. The training provides recommendations on how to be clinically efficient and utilize pediatric patient referrals to other areas of the clinic like the Special Diabetes Program and Clinic dietitians. Dr. Weedn strives to bring the most recent and best practiced methods to her training that provide ways to increase child health.

WATCH staff developed a Site Visit checklist for Health Care Providers to gather a baseline for WATCH staff to learn how we can incorporate OrganWise posters, a video loop within the Pediatric clinic waiting area, and patient handouts. These handouts boost parent interaction in ways for them to track their child’s daily water intake, healthy foods & fiber, and physical activity. These handouts are strategically placed within the clinic to make it easy for providers and clinic staff to distribute handouts to children and their families.

The Healthcare providers also take part in monthly process evaluations. This evaluation allows feedback from the health care provider and their staff members. This feedback alerts staff in areas needed to improve programming and other methods of technical assistance.

All data collected throughout the WATCH program implementation with community partners is transported, stored, analyzed, and housed at SPTHB. Data gathered from community partners will be analyzed for the purpose of evaluation and to give back to the community. It is with the best intention that data is collected for the benefit of those the program serves. During data collection, staff work to ensure safety and security of all participant information. Staff and team members are instructed to always keep participant information and activity confidential. All documents with identifying information will be locked in storage at the SPTHB office.

Staff at SPTHB dedicate special attention to the right of the tribal community to govern the collection, ownership, and application of data collected. Any information collected should not be burdensome and should be for the benefit of the tribal community without causing any unintended harm. If the community partnership has identified specific instructions for the collection, storage, transport, or destruction of data, the SPTHB staff will respectfully oblige. No data will be shared if not explicitly approved from the community partners.

Data entry will occur after the collection of measures. Authorized staff from SPTHB or OUHSC will be able to enter data on secure software. Data entered will then be transferred to the SPTHB organization’s drive. Data entry will be done with codebooks created in Excel. The use of codebook will reduce data entry errors and create ease when analyzing data. Other data entry has been automated by online survey platforms such as Constant Contact to not only collect information but provide an analysis thus minimizing data entry errors as well. After the completion of the analysis, a synopsis is given to the community partners for their review and approval. With reciprocity in mind the information analyzed and approved is put into a 1-page format to distribute to the community partners (Appendix L: Community 1-Pager Analysis will focus on the ability to make real time changes within implementation and for enhancing future implementations in new tribal communities.

WATCH staff make it their mission to tailor this program to fit the specific wants and needs of each participating community. To tailor the program, we encourage all feedback from our partners. This allows us to make programmatic adaptations and shows our flexibility and willingness to serve this program to each community. SPTHB staff began implementing WATCH into tribal communities in August 2018. Since this time, staff have learned many valuable lessons. Most adaptations come from the weekly/monthly process evaluations.

Wyandotte Nation and Eastern Shawnee ECEs were our very first learning centers to take part in WATCH. During this implementation period, we adjusted our target age population from 2to 5-year-old children to 3- to 5-year-old. Through the weekly process evaluations at these centers, we learned that the curriculum being served to each classroom was not at the 5 year and under reading level and that the Gardening and Emotional health kits in the OrganWise Guys curriculum did not match the seasons in which they were taught. Teachers also shared that these lessons were far too advanced for the children attending each ECE. The teachers managed to read the books and watch the videos with these kits, but these kits were removed when WATCH was implemented into the next community.

As WATCH expanded into newer communities in the following year, 2019, WATCH staff learned that it was vital to share our purpose and mission of the program with all community partners. Staff began to schedule introductory meetings and we learned that it was beneficial to bring all ECE and HCPs together in a kickoff style meeting. This was helpful to not only share our mission, but to gather more feedback related to schedules, capacity, and willingness to take part in the WATCH program. As we embarked into the communities of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes ECEs, we included tribal Head Starts. This allowed us to serve more 3- to – 5-year-old children. The communication from the WATCH program staff remains open, flexible, and the staff strives to give our community partners the most respect as they work to implement the program in new communities.

WATCH staff understand that time given to the program by each participating partner is valuable. Staff work to align meetings and training with existing schedules, especially when collaborating with the healthcare provider sector. The lesson learned here is that all meetings need to be purposeful, and time given for the partners to respond to emails is needed because of their remarkably busy schedules. Training and meetings are vital for the HCPs, and staff understand that not all the times provided may be aligned with their current schedules. Added training dates and times should be provided to allow for flexibility in the event the HCPs shift to operations not related to WATCH.

WATCH has adapted to the COVID 19 pandemic. These lessons include the understanding the HCPs may not be available due to shifts strictly related to COVID, meetings have shifted from in person to ZOOM, and in person observations have halted due to COVID protocols at each ECE and HCP site. WATCH does adhere to COVID 19 protocols and mandates at all participating centers, and we have learned that delays in meetings may be interrupted to a shift in schedule due to quarantine, site closures, and full dedication of HCPs to COVID operations within their health systems. COVID has allowed WATCH baseline measures, pre and post, to be selfreported by each participating group, which has cut the need to do EPAO/DOCC observations in person.

The final lesson staff would like to mention is the implementation of the best practice menu. In the earliest community, this process was not feasible in any of the ECEs. Challenges that WATCH staff encountered were related to changes in leadership, some center menus were not provided, and menus were not consistent across all centers. These challenges led WATCH staff to the development of tools to measure readiness and capacity for the implementation of the best practice menu. This was helpful and guided scheduling conversations with partners within the ECEs that had firsthand experience with menu item purchasing and preparing the meals at each center. A Community Capacity survey was developed and is sent via email to ECE staff. Once it is filled out and completed, WATCH staff reviews the submissions and prepares an additional meeting that is a focus group style meeting. At this meeting, WATCH staff has learned what is needed to get the menu created and implemented within each center. An additional lesson learned is to have monthly check-ins with the center to work through any challenges that the centers may face, and this provides a way to make real time changes to following menus. This process has led to the success of implementation of the best practice menu.

Figure 1 - List of Common Acronyms .............................................................................................. 3

Figure 2 - WATCH logo.................................................................................................................... 8

Figure 3a - WATCH logo expanded ................................................................................................. 9

Figure 4 – WATCH Logic Model..................................................................................................... 10

Figure 5 – WATCH Conceptual Model 11

Figure 6 - Kickoff Meeting Timeline 19

Figure 7 - Outcome Evaluation Measures..................................................................................... 21

Figure 8 - Site Visit Checklist for ECE's – Pre 23

Figure 10 - OWG Intro for meetings 28

Figure 11 - OWG Lesson Plan 29

Figure 12 - Activity Calendar 31

Figure 13 - Nutrition Calendar 32

Appendix A: Memorandum of Understanding ............................................................................. 38

Appendix B: Documents for Introductory Kickoff and Meetings ................................................. 41

Appendix C: Letter of Support ...................................................................................................... 48

Appendix D: Director Packet Documents ..................................................................................... 49

D.1 Demographic Survey for Directors 49

D.2 EPAO SR for Director General 50

Appendix E: Teacher Packet Documents ...................................................................................... 57

E.1 Demographic Survey for Teachers 57

E.2 EPAO SR Staff Daily 58

E.3 EPAO SR Staff General 81

Appendix F: Parent Packet Documents 89

F.1 Demographic Survey for Parents and Guardians 89

F.2 Parenting Practices of Diet and Physical Activity 90

Appendix G: Site Visit Checklist .................................................................................................... 92

G.1 Site Visit Checklist for HCP’s- Pre 92

G.2 Site Visit Checklist for HCP’s- Post.......................................................................................... 93

G.3 Site Visit Checklist for ECE’s- Pre............................................................................................ 94

G.4 Site Visit Checklist for ECE’s- Post .......................................................................................... 95

G.5 Site Visit Checklist for Food Prep Personnel- Pre................................................................... 96

Appendix H: Process Evaluations.................................................................................................. 97

H.1 Process Evaluations for HCP’s ................................................................................................ 97

H.2 Teacher Weekly Process Evaluations ..................................................................................... 99

Appendix I: Community Capacity Tools ...................................................................................... 101

I.1 Community Capacity Survey for Food Prep Personnel.......................................................... 101

I.2 Interview for Food Prep Personnel........................................................................................ 103

I.3 Menu Feedback Form ............................................................................................................ 108

I.4 Community Capacity Survey for Teachers and Directors ...................................................... 109

I.5 Interview for Teachers and Directors .................................................................................... 111

Appendix J: Go NAPSACC ............................................................................................................ 116

J.1 Go NAPSACC Child Nutrition.................................................................................................. 116

J.2 Go NAPSACC Infant & Child Physical Activity ........................................................................ 124

J.3 Go NAPSACC Outdoor Play and Learning .............................................................................. 129

J.4 Go NAPSACC Screen Time...................................................................................................... 134

Appendix K: Educational Competencies Crosswalk.................................................................... 137

Appendix L: Community 1-Pager 139

L.1 WATCH Teacher Survey Findings 139

L.2 WATCH Teacher Survey Findings .......................................................................................... 141

1. Cunningham SA, Kramer MR, Narayan KM. Incidence of childhood obesity in the United States. N Engl J Med. Apr 24 2014;370(17):1660-1. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1402397

2. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. Feb 26 2014;311(8):806-14. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.732

3. LaRowe TL, Adams AK, Jobe JB, Cronin KA, Vannatter SM, Prince RJ. Dietary intakes and physical activity among preschool-aged children living in rural American Indian communities before a familybased healthy lifestyle intervention. J Am Diet Assoc. Jul 2010;110(7):1049-57. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2010.04.009

4. Sisson SB, Li J, Stoner JA, et al. Obesogenic environments in tribally-affiliated childcare centers and corresponding obesity rates in preschool children. Prev Med Rep. Jun 2016;3:151-8. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.01.003

5. CDC. Obesity Among Low-Income Preschool Children. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity. Accessed July 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/pednssfactsheet.pdf

6. Hoelscher DM, Kirk S, Ritchie L, Cunningham-Sabo L, Academy Positions C. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: interventions for the prevention and treatment of pediatric overweight and obesity. J Acad Nutr Diet. Oct 2013;113(10):1375-94. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2013.08.004

7. Janz KF, Burns TL, Levy SM, Iowa Bone Development S. Tracking of activity and sedentary behaviors in childhood: the Iowa Bone Development Study. Am J Prev Med. Oct 2005;29(3):171-8. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.001

8. Janz KF, Kwon S, Letuchy EM, et al. Sustained effect of early physical activity on body fat mass in older children. Am J Prev Med. Jul 2009;37(1):35-40. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.012

9. Moore LL, Gao D, Bradlee ML, et al. Does early physical activity predict body fat change throughout childhood? Prev Med. Jul 2003;37(1):10-7.

10. Peck T, Scharf RJ, Conaway MR, DeBoer MD. Viewing as little as 1 hour of TV daily is associated with higher change in BMI between kindergarten and first grade. Obesity (Silver Spring). Aug 2015;23(8):1680-6. doi:10.1002/oby.21132

11. Danner FW. A national longitudinal study of the association between hours of TV viewing and the trajectory of BMI growth among US children. J Pediatr Psychol. Nov-Dec 2008;33(10):1100-7. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsn034

12. Skinner JD, Bounds W, Carruth BR, Morris M, Ziegler P. Predictors of children's body mass index: a longitudinal study of diet and growth in children aged 2-8 y. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. Apr 2004;28(4):476-82. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802405

13. Dennison ME, Sisson SB, Lora K, Stephens LD, Copeland KC, Caudillo C. Assessment of Body Mass Index, Sugar Sweetened Beverage Intake and Time Spent in Physical Activity of American Indian Children in Oklahoma. J Community Health. Aug 2015;40(4):808-14. doi:10.1007/s10900-015-0004-6

14. Dennison ME, Sisson SB, Stephens L, Morris A, S., Dickens R. Obesogenic Behaviors, Self-Efficacy, and Depressive Symptoms in American Indian Children. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research Journal. 2017;24(2):1-23.

15. Han E, Powell LM. Consumption patterns of sugar-sweetened beverages in the United States. J Acad Nutr Diet. Jan 2013;113(1):43-53. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2012.09.016

16. Guenther PM, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Most Americans eat much less than recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc. Sep 2006;106(9):1371-9. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2006.06.002

17. Foulds HJ, Rodgers CD, Duncan V, Ferguson LJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of screen time behaviour among North American indigenous populations. Obes Rev. May 2016;17(5):455-66. doi:10.1111/obr.12389

18. Marshall SJ, Gorely T, Biddle SJ. A descriptive epidemiology of screen-based media use in youth: a review and critique. J Adolesc. Jun 2006;29(3):333-49.

19. Fakhouri TH, Hughes JP, Brody DJ, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Physical Activity and Screen-Time Viewing Among Elementary School-Aged Children in the United States From 2009 to 2010. JAMA Pediatr. Jan 7 2013:1-7. doi:10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.122

20. NHLBI. We Can! Ways to Enhance Children's Activity & Nutrition. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Accessed March, 2018. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/wecan/

21. IOM. Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies. The National Academies Press; 2011.

22. Spivack JG, Swietlik M, Alessandrini E, Faith MS. Primary Care Providers' Knowledge, Practices, and Perceived Barriers to the Treatment and Prevention of Childhood Obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) Nov 12 2010;18(7):1341-7. doi:oby2009410 [pii]

10.1038/oby.2009.410

23. Merline A, Olson L, Cull W. Length of Pediatric Visits Actually Increasing. presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting; 2009; Baltimore, MD. https://www.aap.org/en-us/professionalresources/Research/Pages/Length-of-Pediatric-Visits-Actually-Increasing.aspx

24. AAP. AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits. American Academy of Pediatrics. Accessed June, 2017. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/health-management/Pages/Well-Child-CareA-Check-Up-for-Success.aspx

25. Klein JD, Sesselberg TS, Johnson MS, et al. Adoption of body mass index guidelines for screening and counseling in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. Feb 2010;125(2):265-72. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2985

26. Shreve M, Scott A, Vowell Johnson K. Adequately Addressing Pediatric Obesity: Challenges Faced by Primary Care Providers. South Med J. Jul 2017;110(7):486-490. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000670

27. Brown J, Weedn A, Gillaspy S. Childhood obesity management in primary care: a needs assessment of pediatricians to guide resource development. J Okla State Med Assoc. Sep-Oct 2014;107(9-10):518-22.

28. Rhee KE, Kessl S, Lindback S, Littman M, El-Kareh RE. Provider views on childhood obesity management in primary care settings: a mixed methods analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. Jan 30 2018;18(1):55. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-2870-y

29. Seburg EM, Olson-Bullis BA, Bredeson DM, Hayes MG, Sherwood NE. A Review of Primary CareBased Childhood Obesity Prevention and Treatment Interventions. Curr Obes Rep. Jun 2015;4(2):157-73. doi:10.1007/s13679-015-0160-0

30. Hearn LA, Miller MR, Campbell-Pope R. Review of evidence to guide primary health care policy and practice to prevent childhood obesity. Med J Aust. Apr 21 2008;188(8 Suppl):S87-91.

31. Vine M, Hargreaves MB, Briefel RR, Orfield C. Expanding the role of primary care in the prevention and treatment of childhood obesity: a review of clinic- and community-based recommendations and interventions. J Obes. 2013;2013:172035. doi:10.1155/2013/172035

32. Denney-Wilson E, Robinson A, Laws R, Harris MF. Development and feasibility of a child obesity prevention intervention in general practice: the Healthy 4 Life pilot study. J Paediatr Child Health. Nov 2014;50(11):890-4. doi:10.1111/jpc.12671

33. Resnicow K, McMaster F, Bocian A, et al. Motivational interviewing and dietary counseling for obesity in primary care: an RCT. Pediatrics. Apr 2015;135(4):649-57. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1880

34. Cloutier MM, Wiley J, Huedo-Medina T, et al. Outcomes from a Pediatric Primary Care Weight Management Program: Steps to Growing Up Healthy. J Pediatr. Aug 2015;167(2):372-7 e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.028

35. Chang DI, Gertel-Rosenberg A, Drayton VL, Schmidt S, Angalet GB. A statewide strategy to battle child obesity in Delaware. Health Aff (Millwood). Mar-Apr 2010;29(3):481-90. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0742

36. Chomitz VR, McGowan RJ, Wendel JM, et al. Healthy Living Cambridge Kids: a community-based participatory effort to promote healthy weight and fitness. Obesity (Silver Spring). Feb 2010;18 Suppl 1:S45-53. doi:10.1038/oby.2009.431

37. Cousins JM, Langer SM, Rhew LK, Thomas C. The role of state health departments in supporting community-based obesity prevention. Prev Chronic Dis. Jul 2011;8(4):A87.

38. Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Goldberg JP, et al. A community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: Shape Up Somerville first year results. Obesity (Silver Spring). May 2007;15(5):1325-36. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.155

39. Karanja N, Lutz T, Ritenbaugh C, et al. The TOTS community intervention to prevent overweight in American Indian toddlers beginning at birth: a feasibility and efficacy study. J Community Health. Dec 2010;35(6):667-75. doi:10.1007/s10900-010-9270-5

40. Samuels SE, Craypo L, Boyle M, Crawford PB, Yancey A, Flores G. The California Endowment's Healthy Eating, Active Communities program: a midpoint review. Am J Public Health. Nov 2010;100(11):2114-23. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.192781

41. Weedn AE, Blucker RT, Hopkins M, Gillaspy SR, Spicer P, Taveras E. Qualitative Examination of Health Perceptions and Obesity Among Mothers of Low-Income Preschool American Indian Children. presented at: International Meeting on Indigenous Child Health; 2017; Denver, CO.

42. Smith CL, Walker DR, Kerr KE, et al. Parent’s Role in Obesity Prevention and Healthy Development of Young American Indian Children. presented at: College of Medicine Pediatric Research Day; 2017; Oklahoma City, OK

43. US Dept of Education Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statisics. Digest of Education Statistics. Accessed October 5, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d09/tables/dt09_044.asp

44. Reynolds MA, Jackson Cotwright C, Polhamus B, Gertel-Rosenberg A, Chang D. Obesity prevention in the early care and education setting: successful initiatives across a spectrum of opportunities. J Law Med Ethics. Winter 2013;41 Suppl 2:8-18. doi:10.1111/jlme.12104

45. Donoghue EA, Council On Early C. Quality Early Education and Child Care From Birth to Kindergarten. Pediatrics. Aug 2017;140(2)doi:10.1542/peds.2017-1488

46. Winch PJ, Leban K, Casazza L, Walker L, Pearcy K. An implementation framework for household and community integrated management of childhood illness. Health Policy Plan. Dec 2002;17(4):345-53.

47. IOM. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. National Academies Press; 2005.

48. IOM. Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation. 2012.

49. Ball SC, Benjamin SE, Ward DS. Dietary intakes in North Carolina child-care centers: are children meeting current recommendations? Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S. J Am Diet Assoc. Apr 2008;108(4):718-21. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.014

50. Erinosho T, Dixon LB, Young C, Brotman LM, Hayman LL. Nutrition Practices and Children's Dietary Intakes at 40 Child-Care Centers in New York City. J Am Diet Assoc. Sep 2011;111(9):1391-7. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.06.001

51. Rasbold AH, Adamiec R, Anderson MP, et al. Macronutrient and micronutrient intakes of children in Oklahoma child-care centres, USA. Public Health Nutr. Jun 2016;19(8):1498-505. doi:10.1017/S1368980015002372

52. Nicklas TA, Liu Y, Stuff JE, Fisher JO, Mendoza JA, O'Neil CE. Characterizing lunch meals served and consumed by pre-school children in Head Start. Public Health Nutr. Dec 2013;16(12):2169-77. doi:10.1017/S1368980013001377

53. Bollella MC, Spark A, Boccia LA, Nicklas TA, Pittman BP, Williams CL. Nutrient intake of Head Start children: home vs. school. Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S. J Am Coll Nutr. Apr 1999;18(2):10814.

54. Padget A, Briley ME. Dietary intakes at child-care centers in central Texas fail to meet Food Guide Pyramid recommendations. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. J Am Diet Assoc. May 2005;105(5):790-3. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.002

55. Benjamin Neelon SE, Vaughn A, Ball SC, McWilliams C, Ward DS. Nutrition practices and mealtime environments of North Carolina child care centers. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S. Child Obes. Jun 2012;8(3):216-23. doi:10.1089/chi.2011.0065

56. Briley ME, Jastrow S, Vickers J, Roberts-Gray C. Dietary Intake at Child-Care Centers and Away: Are Parents and Care Providers Working as Partners or at Cross-Purposes? Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1999;99(8):950-954.

57. Worobey J, S. WH, Adler AL. Diet, Activity and BMI in Preschool-Aged Children: Differences Across Settings. Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 2005;44:455-66.

58. Alhassan S, Sirard JR, Robinson TN. The effects of increasing outdoor play time on physical activity in Latino preschool children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2007;2(3):153-8. doi:780590239 [pii] 10.1080/17477160701520108

59. Pate RR, Pfeiffer KA, Trost SG, Ziegler P, Dowda M. Physical activity among children attending preschools. Pediatrics. Nov 2004;114(5):1258-63. doi:114/5/1258 [pii]

10.1542/peds.2003-1088-L

60. Reilly JJ. Low levels of objectively measured physical activity in preschoolers in child care. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Mar 2010;42(3):502-7. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181cea100

61. Sisson SB, Stoner J, Li J, et al. Tribally Affiliated Child-Care Center Environment and Obesogenic Behaviors in Young Children. J Acad Nutr Diet. Mar 2017;117(3):433-440. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2016.10.015

62. Vanderloo LM, Tucker P, Johnson AM, Burke SM, Irwin JD. Environmental Influences on Preschoolers' Physical Activity Levels in Various Early-Learning Facilities. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2015;86(4):360-70. doi:10.1080/02701367.2015.1053105

63. Vanderloo LM, Tucker P, Johnson AM, van Zandvoort MM, Burke SM, Irwin JD. The influence of centre-based childcare on preschoolers' physical activity levels: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Feb 2014;11(2):1794-802. doi:10.3390/ijerph110201794

64. Swyden K, Sisson SB, Lora K, Castle S, Copeland KA. Association of childcare arrangement with overweight and obesity in preschool-aged children: a narrative review of literature. Int J Obes (Lond). Jan 2017;41(1):1-12. doi:10.1038/ijo.2016.198

65. Birch L. Psychological influences on the childhood diet. presented at: Experimental Biology 97; Feb 1998; New Orleans, LA. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9478037

66. Nahikian-Nelms M. Influential factors of caregiver behavior at mealtime: a study of 24 child-care programs. J Am Diet Assoc. May 1997;97(5):505-9. doi:S0002-8223(97)00130-2 [pii] 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00130-2

67. Ward S, Belanger M, Donovan D, Carrier N. Systematic review of the relationship between childcare educators' practices and preschoolers' physical activity and eating behaviours Obes Rev. Dec 2015;16(12):1055-70. doi:10.1111/obr.12315

68. Hoffmann SW, Tug S, Simon P. Child-caregivers' body weight and habitual physical activity status is associated with overweight in kindergartners. Bmc Public Health. Aug 9 2014;14doi:Artn 822

10.1186/1471-2458-14-822

69. Sisson SB, Krampe M, Anundson K, Castle, Sherri. Obesity Prevention Interventions in Child Care: A Systematic Review. Preventive Medicine Reports. Jun 2016;87:57-69. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.016

70. Ward DS, Welker E, Choate A, et al. Strength of obesity prevention interventions in early care and education settings: A systematic review. Prev Med. Feb 2017;95 Suppl:S37-S52. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.033

71. Weber JL, Cunningham-Sabo L, Skipper B, et al. Portion-size estimation training in second- and third-grade American Indian children. Am J Clin Nutr. Apr 1999;69(4 Suppl):782S-787S.

72. Tomlin D, Naylor PJ, McKay H, Zorzi A, Mitchell M, Panagiotopoulos C. The impact of Action Schools! BC on the health of Aboriginal children and youth living in rural and remote communities in British Columbia. Int J Circumpolar Health. Mar 19 2012;71:17999. doi:10.3402/ijch.v71i0.17999

73. Teufel-Shone NI, Gamber M, Watahomigie H, Siyuja TJ, Crozier L, Irwin SL. Using a Participatory Research Approach in a School-Based Physical Activity Intervention to Prevent Diabetes in the Hualapai Indian Community, Arizona, 2002-2006. Preventing Chronic Disease. Sep 2014;11doi:ARTN E166 10.5888/pcd11.130397