Caitlin O’Keeffe-White Matildas, page 11

Misbah Ansari News, page 4

Caitlin O’Keeffe-White Matildas, page 11

Misbah Ansari News, page 4

Caitlin O’Keeffe-White Matildas, page 11

Misbah Ansari News, page 4

Caitlin O’Keeffe-White Matildas, page 11

Misbah Ansari News, page 4

Acknowledgement of Country

institution, predicated on the notion that Western ways of thinking and learning are superior to the First knowledges of Indigenous peoples.

Honi Soit publishes on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. Sovereignty was never ceded. All our knowledge is produced on stolen Indigenous lands. The University of Sydney is principally a colonial

At Honi Soit, we rebuke this claim, and maintain our commitment to platforming and empowering the experiences, perspectives and voices of First Nations students. This basis informs our practice as a paper. As a student newspaper, we have a duty to combat the systems and mechanisms of colonisation.

In this edition

As student journalists, we recognise our responsibility as editors of a radical student newspaper to oppose the inherent racism and exclusivity of mainstream media outlets. We also uphold the struggle of other Indigenous communities worldwide and acknowledge that our resistance is intertwined.

As an editorial team of both Indigenous and non–Indigenous heritage, we are both victims and beneficiaries of colonisation. We are

Editor-in-Chief

Eamonn MurphyEditors

Misbah Ansari, Katarina Butler, Luke Cass, Bipasha Chakraborty, Ethan Floyd, Veronica Lenard, Luke MešteroviĆ, Caitlin O’KeeffeWhite, Andy Park

Contributors

Anonymous, Simar Batra, Nicola Brayan, Josh Clay, Christopher Finnegan, Gus Heesh, Mehnaaz Hossain, Zoie Jin, Zeina Khochaiche, Katarina Kuo, Charlie Lancaster, Zoe Le Marinel, Annabel Li, Rajanikhil Malaramuthan, Angus McGregor, Emily O’Brien, Ira Patole

Artists

Juliette Burgess, Liset Campos Manrique, Christopher Finnegan, Lauren Maccoll, Margot Roberts

committed to unlearning our colonial premonitions and working to hold current institutions accountable.

We are galvanised by our commitment to Indigenous justice.

Editorial

I love to think of the world in doubles.

When I peer into a lake, I wonder what sort of world lies in the reflection. When I look into a mirror, I half-expect a figure to appear behind me: a spectre, or just a little hand on my shoulder. I often wonder whether I have a doppelgänger — it’s always possible. I am fascinated by stories of doppelgängers and secret twins — The Parent Trap is probably to blame for this — and I ponder the alternate world that might exist below our feet: Stranger Things and Us are responsible there. I wonder if there is a utopia to our dystopia, a dream to our nightmare, and how we can bring together what is split in half. So, when I asked our reporters to write on these doubles, I gave them an excerpt from Deborah Levy’s August Blue — a novel that I feel best encapsulates this notion of a world in two. Levy writes: “If she was my double and I was hers, was it true that she was knowing, I was unknowing, she was sane, I was crazy, she was wise, I was foolish? The air was electric between us, the way we transmitted our feelings to each other as they flowed through our arms, which were touching.”

For this reason, I refuse to believe that there is not a better self for each of us, and a better world for all of us, out there. The potential that we hold is limitless, and the stories in this edition address that potential for more.

In this edition’s feature article (p. 12), Katarina Kuo considers an alternate world

Reading the Jacaranda Leaves

Scheduling Clash!

NLS’ decision to doorknock for Yes23 during the Black Lives Still Matter rally drew criticism, climaxing in a tense Twitter standoff between Groots hack Ishbel Dunsmore and NLS headkicker (and Pres candidate) Rose Donnelly. NLS implores us to “understand the harm a No result will do to Indigenous justice,” but can’t seem to turn up to a rally fighting for just that.

Keeping up with the Cunt-dashians

It’s been a characteristically cringe week for the Libs (what’s new?). On Monday, a cute little piece appeared in SBS’ The Feed, where boring Board Director Bryson Constable and wannabe podcaster Satvik R Sharma cleared up some of the “misconceptions” that apparently surround their beloved Liberal Party.

The two seem to believe that the Party has “made strides” in gender parity, are champions of the

newspaper, nor does it endorse any of the advertisements and insertions. Please direct

for pornography: one where we rethink the stifling culture that surrounds pornography, and expand our sexual imagination. Kat’s article is preceded by pieces that also envision better worlds: Misbah Ansari and Rajanikhil Malaramuthan (p. 7) condemn the vilification and violence faced by Muslims in India, and they hope for a world that resists the Bharatiya Janata Party; Christopher Finnegan (p. 8) suggests how we can solve the housing crisis through improving accessibility; and Ira Patole (p. 10) criticises the toxic cult of wellness that pervades our world, and deserves no place in it. Later, Mehnaaz Hossain (p. 14) speaks to how bilingual confusion can split a person’s self into two; Simar Batra (p. 15) ponders the dual worlds that those with chronic illness straddle; Anonymous (p. 16) wonders how gender fluidity can layer one’s identity with possibility; and Josh Clay (p. 17) thinks there are secret panthers in the Blue Mountains.

I would like to acknowledge the artists that have made these stories come to life. Thank you to coffee bean for a cover that perfectly represents the magic of double worlds. Thank you also to Juliette Burgess, Christopher Finnegan, Lauren Maccoll, Liset Campos Manrique and Margot Roberts for their brilliant creations.

I hope that you love the stories that lie between these covers.

Eamonn Murphyenvironment, and that the left should be “very, very scared.” Really, Bryson? We’d consider male-pattern baldness a far more rational fear — that forehead of yours is getting wider by the minute...

The Gig Guide letters only

Dear Honi editors, why the FUCK are the pies at footbridge bakery always sold out when i want one. Sincerely, a pie enthusiast

To, The Honi Soit,

I write to you in anger. Last week, your “comedy” section featured an article in which “Makka Pakka” was caught in a drug bust. Do you think it’s funny to make fun of children’s tv-show characters? Are drugs funny? Is violence against pickle-inspired characters funny? No. It is not. Indeed, the allegations made against Pakka are entirely untrue. You have already had to apologise for your untruths and gossip, I suggest you take down the Pakka article before Night Garden Solicitors come knocking.

PS. Honi fucking sucks.

The Editors,

Last week, on the advice of your gig guide in your Week One Edition, I went to the “One Fine Baby Expo” at the Hordern Pavilion. What a bore. I attended on the assumption that this would be some sort of cool, alternative gig, given the high esteem in which your paper is held. It wasn’t. It was a bunch of fucking babies, crying and whining. I don’t know if this is your idea of fun, but whoever writes these gig guides needs to pull their head in.

Disagree with something that we say? Want to argue? Waiting to profess your love? Send us a letter to editors@honisoit.com

Whorescopes

There’s a lot of beauty in frollicking in the parks, holding hands and laying under the stars with increasing action in your pants.

Aries: Crochet them a strap on! You might not use it but it’s still romantic to weave them kinky things and show all your creativity in bed.

Taurus: What if you switch sides and tie them up? Use your bed frame corners, do soft tickling and eat them out until they come. You look great in power, roar!

Gemini: Cut out bits of your favourite 80s porno magazine and put them on the wall! Claim all that you are: rabbit ears, naked butts on the beach, and organza lingerie.

Cancer: Dirty talk in their ears? Hell yes. There’s no better way than holding them closer and calling them a dirty bitch while they’re inside you.

Leo: It’s your season and cake icing will not be the only creamy thing on you! If you want them to come on you from a different angle and simmer in that sweet, salty glory.

Virgo: Fucking in an alley is fun and totally on the charts for you! Just find the sturdiest door, quietest neighbourhood and slip hands into their pants.

Horny Soit whispers sweet nothings.

Libra: Lighting is so important when getting things going. Play soft Japanese funk, yellow fairy lights and red LED emanating from behind the plants. Look at their face against that ambience and carry them on your bed for a night of immense fun.

Scorpio: House parties can be silly and the balcony is an immaculate place to flirt. A beer in hand, their hand sliding towards yours and steamy eye contact that is just going places now.

Sagittarius: Take a break from people if that’s what suits you. Not all fun needs to be heavily nude, you can just eat crisps in bed and play with their hair. Softness is immensely intimate and mundane romance shall happen for you soon.

Capricorn: Take it all slow and deep down there. Build the tension by stroking things slowly and bring in a hot vibrator to spice things up. See their legs trembling right after, hot!

Aquarius: All this late night texting is getting so raunchy! Step it up (with consent): dirty and intense voice notes, steamy videos in the shower and posing with your ass out in your backyard? It’s all happening.

Pisces: Your joint rolling skills are getting so upbeat, take a few hints of that doobie with your local hottie and let the buzz do its magic!

Art by Katarina ButlerWednesday 23 August

Suhail Launch // Location TBC, USyd Campus // 6.00 am

Thursday 24 August

Cub Sport // The Enmore // 8.00 pm

Ground Level with bella amor, Logan and Lottie World // The Lansdowne // 8.00pm

Amber Rose // The Vanguard // 7.00pm

Law Revue: Evidence Everywhere All At Once // Seymour Centre // 7.00pm

Friday 25 August

Pink Matter // Oxford Art Factory // 7.00pm

The 046 // Oxford Art Factory // 7.30pm

True Vibenation // The Lansdowne // 7.30pm

Big Red Fire Truck, with Wicket Things, Tiger // Factory Floor @ The Factory // 8.00pm

Law Revue: Evidence Everywhere All At Once // Seymour Centre // 7.00pm

Saturday 26 August

Rufino and the Wreckage // Marrickville Bowling Club // 7.30pm

Orion’s Big Backyard with Liam Gale Trio, All Her Years, Rubber Dub // Marrickville Golf Club // 3.00pm

Appiah & Asanti Beats with Afro Moses Spirit Band // Lazybones // 7.00pm

Avatar // Metro Theatre // 8.00pm

High Tropics with Supahoney, Civic Video // The Lady Hampshire // 8.00pm

Law Revue: Evidence Everywhere All At Once // Seymour Centre // 7.00pm

Sunday 27 August

I am Morbid // Factory Theatre // 7.30pm

Zhang Xing Te // Oxford Art Factory // 6.00pm

Monday 28 August

J.I.D // Enmore Theatre // 8.00pm

USyd wants a metro stop

Misbah AnsariThe University of Sydney will be working with the NSW Government to build a metro stop on the Camperdown campus to ease travel for students. This plan falls under Sydney’s Metro West Line from Parramatta to CBD, with considerations of adding more stops on the route.

USyd Vice Chancellor Mark Scott expressed fervent support for the project — “We have always strongly advocated for a station at the University which would serve our students, Royal Prince Alfred

Hospital and health precinct as well as the local community — the need for this is greater than ever and if there are new conversations about the Sydney Metro West line then we are absolutely interested in having them.”

According to Student Representative Council President Lia Perkins, a metro stop “could do well” but the University needs better solutions.

“It’s important to note the other barriers that students accessing campus - in a discriminatory policy of the NSW Government,

international students (and part time domestic students) are deemed ineligible for concession Opal cards doubling the cost of public transport.

“Many more international students are living in Western Sydney as the cost of housing in the inner city has skyrocketed and the University has sold off large amounts of housing stock. We would like the University to act on these other urgent crises for students, or their lobbying attempts for the metro stop will fall short of what students need,” said Perkins.

The project is currently being reviewed by the independent

Sydney Metro Review. NSW Transport Minister Jo Haylen said, “The Government commissioned the Mrdak Yeates Review of Sydney Metro to put the project back on the rails and we’ve put all the options on the table. The final report is due in October and will

Beyond black squares: Black Lives Still Matter rally at Town Hall

Annabel LiThe steps of Sydney’s Town Hall were crowned in red, yellow, and black on Saturday as protesters reunited under the banner of the Black Lives Matter movement that captured the world three years ago.

Attendees echoed the very same calls for justice in addressing the overrepresentation of Indigenous deaths in custody as the watershed BLM protests did in 2020, where 20,000 Sydney-siders took to the streets in spite of burgeoning lockdown orders. Ironically, there was a notable discrepancy in attendance between those protests and this year’s postpandemic rally, which attracted a turnout of about 100.

Organiser and Wiradjuri student activist Ethan Lyons spoke on the matter: “I find it sad that, in 2020, I came with a bunch of friends from high school — they would post on social media, they would post the black square, they were posting the infographics — yet, three years later when it’s not a trend, when it’s not on social media, they aren’t here.

“First Nations people, Blakfellas, are forced to live through that every day — they don’t get a break. We can’t just log off social media.”

Indeed, support for the broader Black Lives Matter movement has fallen to an all-time low, according to findings by the Pew Research Centre in the United States. On home soil, the disproportionate use of police force against First Nations people has only

risen from 2018 to 2022, representing almost half of all cases where police employed excessive force.

“We stood here at this exact same place back in 2020. We said that black lives matter and we demanded so many changes,” said Dunghutti speaker Paul Silva.

“We bawled our eyes out, we set our demands very clearly — yet, they still fell on deaf ears and blind eyes.”

Silva, who has been on the front lines of the movement for almost a decade, pleaded for an independent body to investigate future Indigenous deaths in custody following the death of his uncle, David Dungay Junior.

Dungay Junior was fatally restrained by multiple guards in Long Bay Correctional Centre, after repeatedly pleading that he could not breathe, in December 2015. Dungay Junior’s death mirrors that of George Floyd but, like many other Indigenous fatalities, he has only received a sliver of the public’s attention.

Other speakers advocated for the recognition of injustices against First Nations people beyond the prison system, particularly in regard to the healthcare sector. Ricky Hampson recounted not only the pain from the death of his

son Ricky “Dougie” Hampson Junior — who was fatally misdiagnosed and discharged from Dubbo Base Hospital in 2021 — but the strenuous inquest that followed in search for peace and justice for his family and community.

“This health system is killing our people off slowly as well, and not a lot of people know about it,” said Hampson.

In response, protestors called for the implementation of all recommendations from the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, the closure of Indigenousoverrepresented youth prisons, and for justice when dealing with deaths in custody.

Protesters marched along George Street to the NSW Supreme Court to advocate for such demands, drawing questioning looks from passersby. It seems that the Black Lives Matter movement, three years removed from its peak, has now become an unfamiliar concept for many.

The organisers were deliberate in refraining to align with either camp of the upcoming Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum, with speakers advocating that — regardless of a Yes or a No outcome, mass mobilisation is crucial in the ongoing fight for better outcomes and justice.

If support for the Voice within First Nations communities appears ambiguous, Lyons made one point very clear: “we cannot wait until another Invasion Day rally to mobilise on the streets,” Lyons said. “This is an ongoing genocide against our people.”

Meet Mickie Quick: USyd’s new Printer in Residence

Bipasha Chakraborty and Luke MesterovicMeet Mickie Quick, the University of Sydney’s newest Printer in Residence and current co-Publications Manager at the SRC for Honi Soit

Quick has been one of the SRC’s Publications Managers for almost a decade, a role in which he supervises the publication of this rag. He also delivers the 2000 weekly printed editions of Honi to stands across Camperdown-Darlington campus and the Conservatorium of Music.

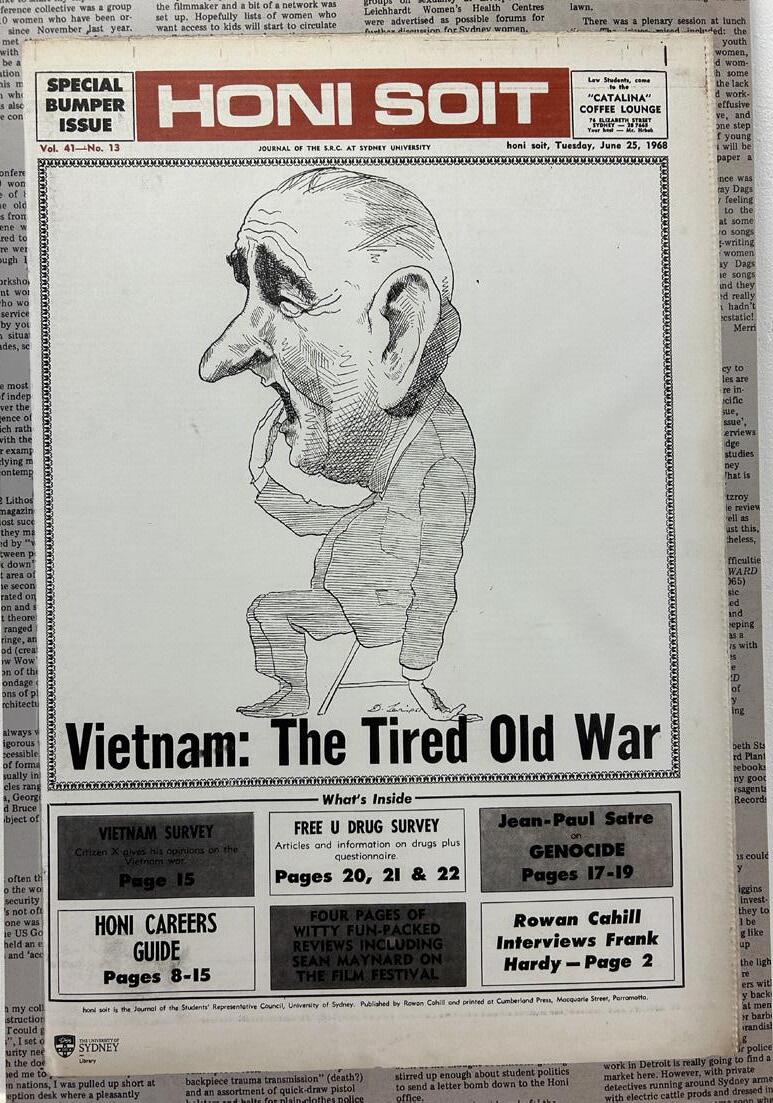

The Printer in Residence program was introduced in 2018, with rotating residents since, as a way for the library to maintain the history of and to encourage the craft of printing with the Piscator Press.

Quick’s 8-week residency, starting from Monday 21 August, is inspired by and will be focusing on the rich history of Honi as both a political and artistic form of history, describing the project as a “link between old style printing, old Honi and current Honi.” As well as Mickie’s long standing relationship with Honi informing

his residency, his long history of graphic design and printmaking are sure to influence the work he creates.

The print room can be found on Level 1 of Fisher Library, near the entrance to the Law Library. It houses antique and authentic printing press equipment, passed down through the decades. This includes an Albion letterpress printer purchased in 1963 and a Sagunuma Chinese typewriter.

Quick will be publishing his printwork regularly in Honi this semester during his residency, so keep your eyes peeled.

As well as attending to the print room everyday for the next few weeks, regular printing workshops will be hosted throughout his residency, which will be advertised on the Fisher Library website.

Invisible LGBTQI+ Australians: ABS apologises for the ‘hurt, stress and anguish’ caused by the 2021 Census

Gus HeeshThe Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) issued a statement of regret on 14 August over the “exclusion members of the LGBTQI+ community encountered in responding to the 2021 Census” as the ABS failed to collect any data on sexual orientation, gender identity or sex characteristics. The statement was released in response to a formal complaint jointly raised to the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) by April Long and Equality Australia.

Long and Equality Australia alleged that the ABS, and then Assistant Treasurer (Michael Sukkar), discriminated against Long who identifies as non-binary and has a child. On census night, Long was not only unable to select “non-binary” as their gender identity, but was also prompted to give the details about the “mother” and “father” of their child, completely erasing their role as a parent. This is just one case where LGBTQI+ people across Australia were

left feeling ‘invisible and excluded’ on census night. In every census to date, LGBTQI+ people who are single, trans and gender diverse, intersex or living in relationships that “pass” as heterosexual have not been counted.

Following the conciliation of the complaint, the ABS has committed to forming an LGBTQI+ Expert Advisory Committee for the 2026 Census to guide survey design and promotion that will more adequately capture data about LGBTQI+ Australians.

This commitment is long overdue. As Equality Australia points out in their campaign “Count Us In”, to

date there is no comprehensive or location specific population data for LGBTQI+ people in Australia. In 2023 the Government, researchers, and policymakers do not know where LGBTQI+ people live, nor accurately how many of us there are. This presents a major barrier when it comes to designing, promoting, and allocating funding for targeted programs and services for LGBTQI+ people. The failure of not only the 2021 census, but every census in previous decades, to show that LGBTQI+ people exist and have needs, has been felt acutely by community organisations such as AIDs Councils (e.g. ACON) and Equality Australia who must campaign for resources

to design much needed services and programs without the rich data afforded to population groups of similar size by the census.

The challenge now lies in designing a survey that is well promoted and designed in meaningful consultation to reflect language that LGBTIQ+ Australians actually identify with. However, Equality Australia outlines that to paint a more accurate picture of LGBTQI+ Australia, this process may involve adding only three additional questions. These three questions must capture gender, sex characteristics, and sexuality as three separate data points, something that the 2021 census failed to do with its addition of “X” as a “non-binary” sex.

The statement of regret and subsequent commitments by the ABS have been welcomed by Equality Australia and other community organisations. Long stated: “This milestone draws us nearer to a census that truly includes us all”.

Inflation is one of the most prominent economic crises facing Australia. While price rises peaked at 7.8% in the December 2022 quarter, annual inflation was still at six per cent by the end of the June 2023 quarter, far above the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) inflation goldilocks zone of two to three per cent. However, Australia’s policy response has disproportionately placed the burden of inflation management on society’s most disadvantaged, a consequence of deeply entrenched neoliberal ideology.

The RBA officially committed to an inflation target of two to three per cent in 1993, pledging to keep the long-term inflation average within this range. Inflation targeting, however, hasn’t always been Australia’s economic priority. The Curtin Labor government’s 1945 “White Paper on Full Employment” advocated for extensive government spending to ensure jobs were easily accessible for all. The post-war boom saw an average unemployment rate of 1.9%, significantly below the recent January 2023 “record low” of 3.5%.

In the 1970s, however, countries around the world adopted the theories of “monetarist” economists, led by neoliberal figurehead Milton Friedman, who argued that an economy’s primary focus should be inflation management through independent central banks. Their legacy lives on today through the RBA’s increasing or decreasing of interest rates in order to change spending habits.

The ultimate goal of raising interest rates is to reduce spending in the economy: in particular, the RBA focuses on the “long-run Phillips Curve”. This theory predicts that if unemployment falls too low, employers will be forced to fight over the smaller pool of available employees, driving up wages and therefore total spending.

Higher levels of people earning wages also fuels greater levels of spending, meaning that increasing unemployment is often a secondary goal of interest rate rises.

Deputy RBA governor Michele Bullock, who will be replacing Phillip Lowe in his role as head of Australia’s central bank next month, noted in a June speech that “employment is above what we would consider to be consistent with our inflation target.” It’s no secret that the RBA believes Australia’s current unemployment rate of 3.6% is too low to keep inflation under wraps.

Stage Three income tax cuts, rather than raising interest rates, would achieve the same goal of reducing excess money in the economy without harming lower-income earners. Both the OECD and Australia Institute have found that super-profits are driving the overwhelming majority of Australia’s inflation.

Many MMT economists have also proposed a renewed focus on full employment through a “Jobs Guarantee,” involving the government guaranteeing a job at minimum wage for those unable to find employment in the private sector. If inflation rises above target and the government needs to raise taxes or reduce spending, those workers who lose their jobs as a result of the decreased economic activity would be pushed into a government guaranteed job rather than unemployment.

Proponents of a Jobs Guarantee argue these jobs could fill niches too unprofitable for the private sector, alleviating labour shortages in sectors such as aged-care or conservation. While the program would require an increase in government spending, they argue that the economic and social costs of unemployment are far higher.

However, using unemployment as a tool to combat inflation clearly impacts the most vulnerable in our society, with those in casual and insecure work typically the first to lose their jobs during recessionary periods. Casual workers were eight times more likely than permanent workers to lose their jobs during the 2021 lockdowns, with young workers bearing 55% of those job losses. Women over 35 are also twice as likely as men to be in casual or part-time work, meaning job losses would exacerbate Australia’s 22.8% gender pay gap.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) economists believe that taxation should be used to combat inflation, shifting the burden of inflation reduction onto companies and high income earners. Increasing superprofit taxes or repealing the

While economists argue that this would be inflationary, there’s a simple lack of evidence that the Phillips Curve accurately describes reality. A significant body of research finds a “flattened” curve that shows no clear relationship between inflation and employment. It’s therefore no surprise that a graph of predictions for the supposed lowest possible noninflationary level of unemployment looks essentially the same as the actual level of unemployment over time.

Economists simply adjust their predictions when proven incorrect and cover their tracks by lamenting the ostensible difficulty of accurate forecasts. Pre-COVID, the RBA believed the magic number to be around five per cent unemployment, however in 2021 Philip Lowe said it could be in the “low fours”, with others even predicting something with “a three in front of it.”

It’s also likely to simply work better at keeping inflation within target. Demand-shocks, such as those caused by sharp and successive rate rises, entrench long-term unemployment as jobless individuals quickly lose skills and the motivation to continue applying for work. This can make restarting economic activity after deflationary periods difficult: post-GFC Australia’s unemployment rate remained above five per cent for most of the 2010s, and from 2015 until 2021 the country experienced persistently below target inflation.

Inflation will stay a key economic debate for years to come, even after the current crisis passes. The recent RBA review recommended no fundamental change to Australia’s inflation targeting framework, a sign of neoliberalism’s resilience in the face of overwhelming failure. Next month, however, Treasurer Jim Chalmers will affirm a full employment target for the first time since the 1945 White Paper. While the exact number remains to be seen, it’s a promising crack in the armour of a decades-old orthodoxy.

Casual workers were eight times more likely than permanent workers to lose their jobs during the 2021 lockdowns, with young workers bearing 55% of those job losses.Daniel Holland investigates Australia’s inflation orthodoxy.

The agony of being Muslim and alive in India

Now that the BJP is comfortably in power at a state and federal level, they have started state-sponsored terrorist activities against minorities — especially Muslims. In April 2023, there were 37 documented crimes against Muslims in India, with likely more undocumented. 90 per cent of the hate crimes against Muslims in India in the 2010s happened after 26 May 2014, when Modi and BJP took

Being Muslim in India is a religious struggle and a deeply casteist one. Dalit Muslims and Christians are currently struggling in the country to fight to be added to the Schedule Caste list. Currently, lower caste non-Hindu minorities are criticising the lack of affirmative action policies for other religions, making the religion-neutral policy of caste reservations a Hindutva policy. Casteism has been reduced to simply a Hindu experience, disregarding the fact that a lot of lower caste Muslims converted to escape the tyranny of casteism.

(RSS). The Party aspires to build a Hindu nation encompassing not just the present boundaries of India, but also Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka. RSS, BJP, and their allies like Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), have campaigned against Muslims even before India got its independence from the British in 1947.

Until the early 1990s these groups were isolated extremists, who didn’t have much influence. That changed when the BJP came to power. The BJP’s campaign was successful, not because they promised progressive policies, but because they promised to build a nation free of Muslims.

At least ten Muslims were killed in various hate crimes in India, last week alone. The RPF officer, after he lynched the Muslim passengers, also chanted in support of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Uttar Pradesh’s hardline conservative chief minister, Yogi Adityanath. He was also recorded on video saying “If you want to live and vote in Hindustan [India], I am telling you, it’s only Modi and Yogi.”

Today,

India is home to the third largest number of Muslims in the world. Islam is the second-largest religion in the world. If this can happen to Muslims in India, no other linguistic, cultural, religious, or ethnic minority group can escape the human rights abuses and stronghold of the Hindu nationalist state. Today, the Indian state headed by the BJP is a threat to its very own people.

Obviously, Muslims are not invariably communities scattered, women’s hijabs and bodies disrespected, and children arrested every day on an unprecedented basis. To be Muslim in a morbidly Hindu society is to be hyper visible and invisible at the same time, resisting BJP’s genocide everyday through our existence.

The BJP’s campaign was successful, not because they promised progressive policies, but because they promised to build a nation free of Muslims.

the Indian state headed by the BJP is a threat to its very own people.

Being Muslim in India is a religious struggle and a deeply casteist one.criticise Hindutva’s violence.

Supply is not the (only) answer

wantstosolvethehousingcrisis.

Riddled with endless price rises, Australia’s property market is a constant source of angst among households and politicians. Although it is widely agreed that there is a national problem, no one seems certain of what to do about it.

Building more homes is an often-raised avenue to relief, but economists are questioning if such a simple solution properly addresses the nuances of Australia’s pervading crisis.

Data from Corelogic, an Australian information and analytics provider, confirm that average real (adjusted for inflation) house prices have risen by approximately 50% since 2003. Broadly, more expensive housing has limited accessibility. From 1986 to 2021, the rate of home ownership fell from 70% to 67%. Younger age groups have seen the worst of the decline, whilst those over the age of 65 now make up 16% of homeowners compared with 11% in 1981.

Renters are also facing pressure as 90% of national rental markets experienced an increase in prices last year. Furthermore, most low-income households are paying over a third of their incomes in gross rent — a proportion that is significantly smaller

incident has wiped out a significant proportion of Australia’s housing stock, most assume that more people are wanting more houses and, in so doing, raising prices. Consequently, both politicians and the media have advocated for a boost in supply to meet demand as a sure-fire solution to the current crisis. However, before we all head to Bunnings for some two-by-fours and an obligatory snag, it is worth considering that simply building more houses may be an unfinished policy response.

Since the 2000s, Australia’s housing stock has increased by 4.3% more than our population has grown. Australia clearly has no issue with keeping construction in-line with population growth, and yet the nation still faces a crisis. There is great need for a shift in rhetoric from this preoccupation with housing availability, to a focus on factors affecting its accessibility.

First, mortgage rates are a key issue. It has been estimated that a one per cent increase in mortgage rates can lead to a seventeen percent decrease in house prices in the long-run. By contrast, increasing the construction of new residential properties each year by 25% will only reduce house prices by roughly one percentage point. This poses a conundrum for policymakers: although lower mortgage rates imply greater affordability for home-buyers in the short term, unaffordability still looms in the future.

The distribution of incomes is another concern, especially regarding rents. Discrepancies in the proportion of income spent on rent between different socio-economic groups, as mentioned above, reflect the fact that the distribution of household income is wider than the distribution of rents. This reflects the central issue of accessibility, not availability, being the issue. There is roughly a supply of “affordable” houses and rental properties, but they are not affordable enough for the people

This also explains the 175,000 households currently on the waiting list for social housing. The Reserve Bank has estimated that there are 440,000 too few for the homeless and in the lowest quintile of household incomes. however, the number of public housing dwellings decreased by over 41,000

Those experiencing homelessness often face mental health problems and disorders which create

greater risk of tenancy failure. In these instances, accommodation and mental health support services are necessary to improve housing stability, where a simple increase in stock could not.

Additional demographic factors are also at play. Australians are entering the workforce and getting married later in life, limiting the budgets of many households.

Fluctuations in immigration have frantically altered demand for housing in and out of the COVID-19 pandemic. Short-term rental platforms like Airbnb have further wiped out a number of options for longer-term tenants. And interestingly, lockdowns and health concerns from the recent pandemic have seen individuals wish to live with fewer people, creating an estimated 120,000 new households in the past three years.

Evidently, the government’s response must account for the complexity of the housing market in lieu of a dogmatic push for increasing supply in big cities. One such approach would be encouraging economic growth in regional centres to alleviate stress on the nation’s densely populated capital cities. Greater investment and creation of higherincome jobs in the country would dramatically shift the concentration of housing demand to regions where there is adequate room and resources for expansion. Policies which capitalise on Australia’s vast geographical space will simultaneously lower the upward pressure on house prices and bolster the economy for future growth.

To combat prices with increased housing stock, more creative measures could also be allocatively efficient than simply developing new residential areas. For example, implementation of a vacancy tax, such as in Canada, could lower the number of short-term rentals and increase supply for tenants. Furthermore, commercial properties such as office spaces in CBD areas which are no longer being used for office space could be converted into high-density housing.

Finally, greater support services to assist with accessing stable housing is critical, especially for the vulnerable. Those with greater needs have been failed by reductions in available public housing, and should not be made to wait along with hundreds of thousands of others for such a basic necessity.

Increasing supply is important. Without stock keeping up with population growth, Australia’s housing market would undoubtedly fall into further strife. However, boosting housing availability is nothing without a synergistic array of further responses to ensure housing is accessible, safe and stable for all.

Art by Christopher Finnegan

SnowFLflakes: on being white and fragile

Nicola Brayan thinks white people should shut up.

I am white. As a kid, I was told that racism is evil, and that everyone is the same, regardless of their skin colour. This framing of racism is a simple one: if you, a small white child, refrain from being cruel to your classmates, you are doing the world a favour. Good for you! With age, though, this framing starts to fall short.

The term “white fragility” was coined by author Robin DiAngelo in 2011. According to DiAngelo, “White Fragility is a state in which even a minimal challenge to the white position becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves including: argumentation, invalidation, silence, withdrawal and claims of being attacked and misunderstood.” To better understand this, I spoke to a range of POC, who I refer to throughout this article.

Existing in a world that treats you as a priority can predispose white people to feel entitled to priority, and to feel threatened when that priority is re-allocated. This can look like moral panic in response to affirmative action policies, escalating as far as the US Supreme Court’s decision to bar universities from having such policies. Annie tells me that she has experienced backlash from “old white men who are used to having the world conform to them” when doing something as simple as getting on a train before them. She pointed to the trope of a “Karen” — an older white woman who throws a tantrum when she doesn’t get what she wants — as an illustration of how common this entitled fragility is (albeit an imperfect one with sexist implications).

traits, or because, as three-dimensional beings, they likely experience some hardship or oppression themselves. Introducing other axes of oppression is a misguided attempt to de-pedestalise oneself for fear of being cast as a villain. No matter how many other ways a white person is oppressed, they still benefit more from white privilege than a POC does — to downplay that is dishonest.

This deflection derives from the underlying tenet of white fragility: defensiveness. “White people get SO defensive when called out,” Mehnaaz explains, “it often really freaks them out to hear that they are also doing things wrong or can change.” This defensiveness is often born of a fear of being labelled racist. This fear can snowball into active harm: one interviewee described being a part of an activism group led by a white organiser who got so defensive when POC suggested that certain elements of their activism weren’t culturally sensitive that it became “no longer a safe community space”. Constant defensiveness — challenging POC on their interpretations of an action as racist, insisting that they cannot be racist, and shaming those who call them out — is actively harmful. It punishes POC for speaking up about injustice and forces them to console white people, all while continuing to suffer from racism. “Recognising” privilege means nothing if that doesn’t also involve reckoning with it.

Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility, is white. When I pitched this article to my editors, Misbah said, “white people should be more critical of whiteness”. The burden that white people have — that I have — should not be to simply recognise their privilege, but to interrogate it, to wring it out like a wet towel and see what drips out. “I wish white people were okay with taking on that lil discomfort for the greater good,” Aleina explains. Discussions about racism should not be dominated by white people trying to prove that they aren’t racist, but by POC, who know what is racist. “So many white people are allergic to listening,” Mehnaaz tells me. “I don’t need a speech on how lucky you are. I just need you to know when to stop speaking.”

For many white people, it is very easy not to identify with this type of fragility. It’s tempting to think of Karens and old white guys as a unique brand of white people — entitled, ignorant, probably conservative — that we, young, progressive white people couldn’t be less like. After all, we recognise our privilege. The issue, though, is that the bar to clear to have “recognised” something is incredibly low. Recognising just means “identifying”; it does not entail anything further. White fragility is very much prevalent within leftist and progressive spaces; if anything, this identity of progressivism can cause white people who are called out for their whiteness to double down — to be more fragile.

White fragility can result in the equation of racism to other forms of oppression. Multiple interviewees pointed to their own experiences with queer white people or white women downplaying their privilege by insisting that they can relate to the struggles of being discriminated against. Sujin describes it as “annoying” and a “petty competition”; Mehnaaz (in meme format) describes other “axes of oppression” such as queerness as bandaids with which white people use to cover their “white guilt”. In a binary between whiteness and POC, whiteness is, categorically, oppressive. Most white people don’t see themselves as oppressors, either because it is an abstract category with extreme

Throughout this article, I have struggled to choose between first and third-person pronouns when describing white people. I relate to the fears which I have described in this article; I desperately do not want people to think that I’m racist. I have friends who are POC who I would hate to hurt or isolate. I have seen them hurt by systems which I profit from. I’ve heard countless rants about how dumb white people are, and have sat there, nodding, as though I can relate. Even now, writing this, I struggle to attribute my defensiveness to anything but a desire to be inclusive and thoughtful. In reality, though, that isn’t true. This defensiveness stems from the assumption that, unless I make it abundantly clear, the POC in my life will assume that I am racist. This is silly. It presupposes that I am the main character, that all the POC in my life need to be told whether I am racist or not, and can’t work out for themselves that I’ve grown up as a white person with white privilege and I’m doing my best. Of course they can.

Existing in a world that treats you as a priority can predispose white people to feel entitled to priority, and to feel threatened when that priority is re-allocated.

“Recognising” privilege means nothing if that doesn’t also involve reckoning with it.Art by Liset Campos Manrique

Maths Anxiety: Count your days

A dear friend of mine is in the second year of their mathematics degree, and when they tell people this, the response is pretty much ubiquitous.

I could never do that.

There seems to be a strong perception that mathematics is an inherently stressful and difficult area of study. Part of this perception seems to arise from the frequency of maths anxiety.

Far from just hating maths or struggling with it, maths anxiety typically involves strong feelings of dread, stress and anxiety around tasks that involve maths. Maths anxiety is estimated to affect twenty per cent of students, and up to 50% of adults. I’d never experienced maths anxiety in high school, so I didn’t have any idea what it was like until after a horrible, stressful statistics exam last semester. When I got home after the exam, I sat down against my door and cried and cried out of sheer relief that it was over. When I went to pack away my notes later that evening, I saw the sheet covered with formulas and equations, and even the sight of it made my heart start to pound.

Dr Ben Zunica, from the Maths Education department at USyd, hypothesises that maths anxiety is partly a product of the pressure on students to get the answer. Maths, as a subject, involves a lot of trial and error, and Dr Zunica has observed in his years as a maths teacher that students struggle with the pressure to get it right every time. Dr Bronwyn Reid O’Conner, who is also involved in research into maths anxiety, remarked that this trend causes students, particularly women, to underestimate their own abilities and consequently avoid enrolling in STEM degrees that call for mathematics. Dr O’Conner also suggests that maths anxiety is neurochemically different from general anxiety in a way that generates a vicious cycle of negativity — affecting performance and leading students to falsely believe that they’re “just not a maths person”.

Both Dr Zunica and Dr O’Connor identified maths anxiety as much more common in women than in

The Cult of Wellness

I was scrolling through YouTube the other day, and stumbled upon another short by a guy claiming to be a wellness influencer, listing what he eats in a day. I rolled my eyes and swiped past, but something got me thinking, how did I already know what he was going to say? Why is “motivation” content (and there is a lot of it) so repetitive? Why is every guy who’s telling me to drink a gallon of water a day, also telling me to go to the gym and invest in the stock market?

I decided to do a little investigation (i.e., watched motivation channels on YouTube for an hour) and developed a hypothesis. The way I see it, these guys were born into a shitty, messy, confusing, and unjust world. As they grew up, they began seeing it more and more for what it truly was, and that scared the hell out of them. They figured out they couldn’t really change it, so the only way to be happy would be to change themselves beyond recognition. They decided to try to crack the code of how to be “successful” in this world. The world told them that making themselves perfect would be a good start.

At this point, I realised that maybe they weren’t that different to me. For all my life, I too had been obsessed with the idea of achieving perfection in everything I did. If I was going to write something, it had to be the most perfect way of communicating that idea, or else it shouldn’t exist. If I was going to date other people, I needed to have a perfect body and perfect mental health. The circles that I existed in, were also obsessed with the idea of perfecting relationships. Of being ideal friends and partners to each other. Of never saying anything hurtful, or being messy or needy.

The boundaries of what is an acceptable way to be are shrinking every day. If you’re not going to the gym three times a week, you’re not just neglecting your body, but actively harming it. The same goes for food, if you’re eating anything beyond the perfect composition of macros, you’re causing long-term damage. If you’re buying yourself little treats, you’re careless with your finances and will never be able to save. And you need to be doing all of these things at the same time. You also need to be going to therapy, and working on your

asks: is there a reason why you think you aren’t a maths person?

men. Dr O’Conner discussed the major role of stereotypes in setting up young female students to underestimate themselves. Similarly, demographics stereotyped as being “good at maths” can develop maths anxiety as a result of trying to live up to the stereotype. Considering the effect maths anxiety is having on the representation of women in STEM, there is little initiative to combat its negative influence. The Mathematics Learning Hub is an excellent resource for students struggling with maths content, but offers little avenue for reducing the anxiety that maths can

Unfortunately, I have experienced a negative culture around engaging with maths from the perspective of my Psychology major. Compulsory statistics courses in the program engaged with students from an inflexible, needlessly competitive angle creating undue stress. In our first lecture, the introduction consisted mainly of “none of you want to be here, so let’s just get it

over with.” As the course continued, I witnessed perfectly capable students stumble attitudes may be contributing to the larger problems in STEM recruitment.

Maths anxiety is endemic in education, but it is highly manageable. A dislike of maths is understandable, but chances are it has more the cultural pressure of success than your own abilities. The academics that I consulted recommend moving away from judgements about your own ability, and engaging with a comfortable level of maths in a low-pressure environment. Be prepared to be wrong, and to learn through trial and error. Give it a shot, you’ll surprise yourself.

Ira Patole implores you to take a fucking nap.

communication, and cooking your own food, taking the stairs, wearing sunscreen indoors.

It’s fucking exhausting. I feel like I’m stuck underwater with a million reasons to panic but I’m being told not to breathe too fast or I’d be wasting my oxygen.

So why are we like this? Besides the pervasive capitalist pressure to succeed and become rich, I think Western philosophy is the largest culprit. In contrast to a lot of Eastern philosophy that has been about observing the world and understanding life as it is, with its ups and downs and yins and yangs, western philosophy has almost entirely been driven by the idea of finding answers to what is good and right and best. There is little room for error.

The obsession with perfection causes societal harm. It is never good when the range of what is considered normal drastically narrows. People have never been homogeneous; when restrictive standards of normality are imposed, anyone who existed on the extremities has been outcast.

This is most clear in the realm of psychology: the pathologisation of difference has resulted in the ostracisation and mistreatment of anyone who was neurodivergent or had mental illnesses. People trying to “fix” or “cure” those with different ways of expressing themselves, working, and thinking, have been historically allowed to get away with horrific practices.

The pursuit of perfection is also harmful to all of us at an individual level. The more unrealistic standards we set for ourselves, the more we will fail at achieving them. And the higher the standards get for the “bare minimum”, the worse the sting of failure will be. Because now you’re not failing at being perfect, which most people could accept, you’re failing at being functioning. You’re failing at life. And when you feel like that for most of the things you’re doing in a day, it doesn’t take a genius to figure out that that feeds your anxiety. Even when you have moments of joy or moderate success, they are overpowered by the amount of guilt and worry about aspects of your life that aren’t ideal. Even when you do have opportunities to be happy, you feel like you have no right to be.

What do the Matildas mean to you?

UP THE TILLIES:

From a recent Matildas convert

My first memory of football is my under-7s self practising cartwheels in goal, while my coach yelled at me to keep both feet on the floor and two eyes on the ball. I thought he was being a bit dramatic — the ball was at the other end of the field, and it was boring watching the boys play while I did nothing.* Suffice to say I was never put in goal again, and my formal football career ended after one season. Football left my life, and other sports entered.

I hadn’t thought much about the game since — that is until four weeks ago, when the Matildas had their first game of the FIFA World Cup. I watched it at home, on the couch, more out of procrastination than any genuine interest. Within five minutes my heart rate had increased and I had to keep reminding myself to breathe. Catley’s goal sent me for a run around my lounge room, and I spent the rest of the night obsessively watching old interviews of the Matildas.

By the time they played Canada, I had purchased one of the last jerseys on the rack at Rebel Broadway, knew each of the twenty three players on the team, and had ventured so far back on YouTube I was watching Sam Kerr’s goals from when she was twelve.

My new found love of Matildas, as it turns out, aligned with the rest of Australia. This season’s jersey has outsold past editions thirteen to one, and 7.2 million people tuned into the last game against France — the largest audience for a sporting event in at least a decade. At the game against Canada, my friends and I arrived fifteen minutes before kick off and couldn’t find a seat at the pub. At last week’s game, against France, we arrived an hour before kick off at Tumbalong Park, and were informed that they were nearing capacity and recommended we go to the roof of the ICC to watch the game there. The Inner West Council has wrapped bins with support for the Matildas, and the trendiest cafe I go to (a kind of wankery one, big on minimalist design) had a Matildas’ scarf draped on a shelf, held up by bags of coffee beans. Politicians, journalists, CEOs, the Department of Education — everyone seems to have gotten behind the Matildas.

Caitlin O’Keeffe-White is pacing with nervous energy.While this may seem like a meteoric rise to those on the outside, the truth is anything but. Women’s football in the nation has historically been underfunded — in 1999 the Matildas posed naked to raise money to prepare for the Olympics. Many talented players have had to leave the sport throughout the years, unable to live off the wages that were paid to women footballers. It was only in 2019 that the pay gap between the Matildas and the Socceroos closed. The Matildas are still fighting for equal pay (if they win the World Cup, they walk away with a quarter of what the men do — something they are actively campaigning to change). These pay concerns are coupled by significant injuries from key players in the lead up to the cup — Carpenter’s ACL tear and Raso’s broken back spring to mind. Australia may rally behind them now, but it’s important to remember what our widespread lack of support has meant historically. The sense of community that has emerged throughout this World Cup is unmatched in my memory. At the game against France, my mates exchanged information about how extra time and penalties work to the people beside us, while they shared their rug and gum with us. I have gotten nods and WOOOOs yelled at me while I wear green and gold, and have done the same to others donning the Tillies I know I’ll be giving football another shot next year, and I don’t think I’m the only woman who will be doing this.

have my heart (and my tears). I have found endless joy in realising how many queer and lesbian women are on the national team — never have I felt more represented

than by the Matildas. Sam Kerr earlier this year said “everyone should feel comfortable in whatever skin they’re in, whoever they want to be, whoever they want to love.” This post, representative of the culture of the Matildas, was the first of many that made me cry.

I found myself crying after watching a video of Katrina Gorry’s child running around, thinking about what this means for women returning to sport after childbirth. I cried at the Facebook post of a mum saying Cortnee Vine came back out with her jersey to give her daughter. I cried after Mary Fowler’s Instagram post showing people in Kira Kira, a village in Papua New Guinea that Fowler’s mother is from, crowded around a television, watching the game against France. Supporting this team, alongside everyone else, has made me understand the joy of watching sport, and what being involved in a team looks like.

The Matildas are up against England tonight. Every atom in my body wants them to win. But win or loss, the Australia

Art by Veronica LenardWe need to talk about porn.

In the 1980s, the feminist movement became divided on the issue of porn. Anti-porn feminists argued that porn, as well as the industry that produced it, was fundamentally oppressive and dehumanising to women. Pro-porn feminists saw this position as aligned with the political right’s crusade against recreational sex. If the exploitative aspects of porn could be removed, they argued, porn could serve as a healthy expression of sexuality and as a tool for sexual liberation.

Current feminist attitudes are far more closely aligned with the arguments made by pro-porn feminists. In many ways, it may seem as though we are living in, or at least approaching, the sexually liberated future that they envisaged. It is widely acknowledged that many people consume porn and use it, not only for sexual satisfaction, but as a tool for their own education. Women, many of whom are feminists, consume porn too. For most consumers, porn is a source of genuine enjoyment.

However, is porn becoming the liberatory tool that pro-porn feminists dreamed it could be? Is it just another form of art? A way to express healthy sexuality? Even if we set aside the exploitative elements of porn production (which are important not to understate), I argue that it is not.

As political theorist Amia Srinivasan writes, “While filmed sex seemingly opens up a world of sexual possibility, all too often it shuts down the sexual imagination, making it weak, lazy, dependent, codified.” The problem is not that porn fails to embolden its viewer’s propensity for sexual fantasy, but that it stifles what that sexual fantasy can look like. It programs its viewers with rote responses, conditioning them to seek out and reproduce sexual gratification in a way that is often objectifying and reductive. In short, porn is prescriptive about what sex should be. This is unusual, particularly if we compare

porn to other types of media that we engage with regularly. Engaging with books, films, television, and music expands our imagination. Why is it, then, that porn tends to stifle it?

One potential answer is that porn itself is an unimaginative representation of sex. Historically, this has been one of the most common arguments feminists have forwarded in their attempts to reform our engagement with porn. Porn is homogenous — it too often focuses on heterosexual male pleasure, objectifies women, and fetishizes difference. If we could supply people, the logic goes, with porn that earnestly depicts female pleasure and a diversity of body types and sexualities, it could improve the understanding of sex we gain from it.

Engaging with books, films, television, and music expands our imagination. Why is it, then, that porn tends to stifle it?

However, this argument is becoming increasingly uncompelling. Of course, diverse porn is important, and we should continue to expand its ability to be produced and accessed. But, in our current context, where porn is free and accessible in boundless volume, it is reasonably easy to source porn that is realistic and representative. Porn is diverse — the problem is often that we do not consume the diverse versions of it that would best represent us.

Although it is true that a lot of porn offers a misogynistic depiction of sex, other art that is also produced by a male gaze does not necessarily bear the same detrimental effect on its consumers’ imagination. The overwhelming majority of films are directed by men, Hollywood

routinely fails to cast diverse actors, and most literature historically has been dominated by the perspectives of men. However, we still find ways to use this media to expand our imaginative capacities. Women, for example, commonly enjoy books written by men, often with the acknowledgement in mind that the perspective they are reading need not be authoritative.

Moreover, audiences actively seek out and engage meaningfully with diverse representation where it does exist. Of course, porn consumption habits are often moulded by corporations and the algorithmic categories that drive their profits, but this is also true of almost all other forms of art. While we are good at seeking out television, literature, and films that represent us, we are far more willing to settle for porn that is formulaic, unrealistic, and misogynistic. None of this is to say that the lack of diverse representation that exists in other forms of art is trivial — it is impactful, and we should certainly be doing more to address it — but it does not constrain the imagination quite as profoundly as porn does.

Perhaps it is more likely, then, that we are unimaginative consumers of porn.

Part of the problem is that we are not equipped with the necessary education to consume porn in the way that we consume other media. Education systems tend to be good at teaching the value of critical responsiveness and personal interpretation across a range of disciplines. By contrast, sex education routinely fails to promote

Part of the problem is that we are not equipped with the necessary education to consume porn in the way that we consume other media.Katarina Kuo wonders how we can better approach porn. Art by Juliette Burgess

skills which allow young people to safely incorporate porn into their sexual development. Increasingly, experts advocate for the teaching of ‘porn literacy’. If we want to engage with porn that allows us to be more sexually imaginative, we need to know how to approach it. Particularly given the sheer volume of porn that exists on the internet, we need to develop the skills to navigate it and to critically evaluate our viewing experiences.

Developing education in service of this goal, however, faces a number of hurdles. In his 2022 book, What Do We Know About the Effects of Pornography After Fifty Years of Academic Research? , Professor Alan McKee argues that even the study of porn itself has historically been monolithic, treating all pornography as if it were the same. It is hard to teach students to engage with porn imaginatively when academic research itself is often unimaginative. Additionally, education programs which seek to improve porn literacy are often constrained by restrictions on the kinds of material that can be shown in classrooms.

Not only is developing more robust porn literacy curricula a far-off goal, the lack of this specific kind of education does not fully explain the imagination-stifling impacts of porn. Even without explicit education about how we should consume other media, most people are intuitively able to engage with it relatively healthily. Books and films, for example, expand children’s capacity for imagination long before they are taught to critically engage with them or to critique their content. By contrast, from the moment we begin consuming it, we often afford porn undue authority — we are inclined to view its representations of sex as instructive, and we often expect them to be replicated in private. Srinivasan describes talking to her students about the impact of porn on their lives: “My male students complained about the routines they were expected to perform in sex… my women students talked about the neglect of female pleasure in the pornographic script, and wondered whether it had something to do with the absence of pleasure in their own lives.”

Although increasing porn literacy education would certainly be a step in the right direction, our obsession with viewing porn’s representations of sex as authoritative suggests that resolving the imagination-stifling problem of porn is not simply a question of being taught to navigate it well. The impulse to view porn as authoritative is very different to the impulses we bring to our consumption of other media. Almost no one, no matter how inexperienced they are in consuming art, would so obsessively expect it to be replicated in their personal experience. We don’t see Ibsen, for example, as the authority for how we should engage with our own families, or Love Island as the authority for how we should approach dating.

But porn does not depict just any experience. It depicts sex — a topic about which we naturally face confusion and seek affirmation.

It is regrettable that sex education remains almost universally inadequate. Even in jurisdictions where sex education is mandated in schools (although, notably, the push to mandate this education has been a relatively recent phenomenon which faces staunch opposition in most parts of the world), its actual delivery remains highly varied. Teachers are seldom equipped with the training to supply their students with useful guidance and students are seldom comfortable asking questions that would lead to robust discussion. People often seek out porn as informal sex education. Michelle

Fine describes porn as providing a “discourse of erotics”, offering instructions on how to initiate and carry out sexual activity that we struggle to find elsewhere.

In an op-ed in the New York Times in 2018, porn star Stoya wrote, “I didn’t want the responsibility of shaping young minds. And yet, thanks to this country’s non-functional sex education system and the ubiquitous access to porn by anyone with an internet connection, I have that responsibility anyway. Sometimes it keeps me awake at night.”

Where heteronormative sex education is lacking, queer sex education is non-existent. Young queer people often rely on porn for its educational function and, in the process, similar problems appear. Moreover, the homogeneity of the academic study of porn makes it harder to address the specific nuances of queer porn and its impact.

Not only are we poorly educated about the practice of sex, but we often lack education about its broader sociocultural meaning. Indeed, Australian academic Kath Albury questions the extent to which adding a critique of porn to existing sex education programs would be effective if other areas of the curriculum do not directly address questions of power, gender relations, and sexual negotiation. Despite its entanglement with political issues, sex often feels tangential to classroom discussions of politics and power, and educators feel uncomfortable including it.

to think about what sex could be or mean, we have no natural defences against how porn depicts it — we welcome it with open arms and, in the process, relinquish our ability to be imaginative.

It is important to note that one of the biggest contributing factors to the enduring persuasiveness of the arguments made by proporn feminists was the advent of the internet. In this context, the eradication of porn that antiporn feminists dreamed of became impossible, and pro-porn feminists’ willingness to engage with the possibility of its improvement became far more persuasive. This is undoubtedly for the best. Porn will, most likely, always exist and be viewed widely — it is important that feminists consider how this can be transformed into a tool for liberation. Additionally, attempts to legislate against porn often harm the women who make it and depend on it for financial security — the logic of pro-porn feminists offers the best chance of granting these women safe and ethical work practices.

Nevertheless, it’s worth remembering that feminists engage with porn as an artistic and educational tool, at least in part, out of necessity. Far too often, people assume that porn itself should be the logical site of reform, but this is inconsistent with many of the reasons that we have had to embrace it. Improving the ability for porn to be used as a tool for sexual liberation is an ongoing battle, and requires a far broader effort to reform our consumption than what exists currently.

While their proposed solutions may no longer be tenable, it is worthwhile revisiting the concerns expressed by anti-porn feminists. Feminists like Catherine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin saw pornography as a tool of the patriarchy, which violated women’s civil rights by ordering attacks against them. They argued that porn robbed women of agency by forcing them into symbolic roles from which they could not escape, and that it trained men to see the violation of women’s bodies as an act of sex in itself. All of this, they argued, became an exercise carried out for profit.

Outside of the classroom, the taboo surrounding sex also looms large. Even after years of advocacy in favour of normalisation, we still struggle to talk about sex. We often feel that it is unacademic or uncivilised or we feel embarrassed to admit that we don’t fully understand it. Even in more progressive circles, narratives which seek to preserve people’s privacy often produce the undesirable side effect of discouraging people from asking any questions about sex at all.

Our inability (or, perhaps, our unwillingness) to talk about sex is incongruous with how much it means to us. Most people attach significant personal and cultural significance to sex. Sex is intimate — it connects us not only to other people, sometimes even as an expression of love, but to our own bodies. Sex can also be socially validating — we perceive that it confirms our sense of attractiveness or prowess in a way that is deeply intimated with our self-image.

I would argue that what stifles our imagination is not just porn illiteracy, but a broader illiteracy surrounding sex itself. It is rare to care so much about something, for it to be such an important part of our lives, and to not be able to talk about it. By the time we come to porn, we are willing to grant it authority because what it offers us is so rare. Awestruck and relieved by the opportunity

None of these concerns suggest that the act of filming sex, or watching filmed sex, is a problem, but that the conditions under which we would do so are problematic. Given this, the hope that the harms of porn could be resolved simply by widening the scope of content that porn delivers, or through simple sex education, is a false one. Porn is not consumed in a vacuum — it is a small piece of a broader picture, and it is not solely responsible for its own failure to expand our sexual imagination.

The legacy of anti-porn feminists is messy. Many of the claims made by feminists like Dworkin and MacKinnon have translated poorly to the current realities of porn and, indeed, have been invoked in support of policies that shame and exclude sex workers. I want to be clear that these are not the claims I suggest we revisit or endorse.

Nevertheless, anti-porn feminists’ concern that porn could stifle the sexual imagination remains a pressing one. In 1987, Dworkin warned of the danger of allowing porn to consign the sexual imagination to “a nearly bare junkyard of symbols manipulated to evoke rote responses”. Banning porn is not a viable solution to make porn less imagination-stifling; we must be more imaginative in solving its problems.

Our obsession with viewing porn’s representations of sex as authoritative suggests that resolving the imagination-stifling problem of porn is not simply a question of being taught to navigate it well.

No. I can’t read his mind.

I wouldn’t blame you if your first thought when I mention twins is of matching outfits, indistinguishable physical features, and eerily similar first names. Throughout popular culture, twins have garnered a somewhat eerie reputation, however in real life the experience is completely mundane.

The idea that twins are something kind of magical seems to be almost universally acknowledged. Whenever I mention offhand that I happen to have a sibling with whom I share a birthday, I hear “woah, no way!” or “wait, are you identical?”. But for us, it’s nothing special.

I am a twin. My twin’s name is Josh. And to us, the universal admiration for our genetic anomaly is unrecognisable.

Other than the fact we have different gender and personal identities, we truly only felt like twins when we were young. We were defined not by our features or our likeness but by our differences. Josh was the Maths brain and I, the

English brain. We clung to what differentiated us. Our identities were inherently linked to what we were most “talented” at and it felt like the borders of our interests and potential were defined before we could even decide for ourselves. This led to a sort of unbreakable ownership and competitiveness of those areas.

Now we just feel like siblings lucky enough to be the same age. But why? Is it because of our seemingly opposite identities? Sometimes I theorise that our conception as test tube twins — each sperm manually inserted into an ovum in vitro and incubated for 5 days — has left us more disconnected than true fraternal or identical twins. Does this justify our inability to fulfil the stereotype everyone so desperately wants to paint? We have been to primary school, high school, and over a decade of extracurricular activities together and yet our twinhood still feels so atypical.

Most importantly, unlike some twin-media may suggest, we

absolutely cannot read each other’s minds. If my stomach hurts, he doesn’t know about it. If someone we hate walks in the room, we don’t need telepathy to know. And we’ve hated each other at one point or another.

We didn’t want to be with each other in every waking moment. And we definitely avoided each other in school.

Now with that off our chests, I thought you should know this week my twin and I turn twentyone. Even after twenty one years growing up in the same schools, the same house and the same environment, our twinhood will remain something uniquely original to us. We differ from typical siblings, having experienced the same seasons and milestones together, but as time has gone on, we feel less and less like twins.

I asked Josh what he thought about our experience. Lazily diverting his attention from his laptop he said, “Sometimes I forget we are twins but it’s cool. You’re cool. We’re just different twins, I guess. Nothing crazy. Yeah.”

We were never dressed in the same clothes (although we truly wish we were, so this one doesn’t count).

And to that magnificently introspective and thought out response from my fellow genetic anomaly I say, “Yeah. What he said.”

Art by Lauren MacColl

Art by Lauren MacColl

The idea that twins are something kind of magical seems to be almost universally acknowledged.

ilingual

There is a version of me that is perfecting herself constantly: an English major, a voracious reader, with an exponentially growing vocabulary. I find joy in the fact that 19 year old me is more articulate than 18 year old me, and that this is a steady reliable pattern throughout life. This pattern does not exist in my mother tongue. Bangla does not adhere to the rules of exponential growth. There exists another version of me that is stuck at the age of 13, operating on a conversational level, frozen in a specific time and age. I hit the child-of-immigrants-languageabsorbency-ceiling; I can make lovely dinner party small talk, but attempting to convey a nuanced opinion feels suffocating.

It feels disconcerting to bring these two versions together — to come home from a long day of analysing literature at uni to find myself armed with what feels like only a handful of elementary words. Two disparate selves, each with a different capacity for communication. My “double selves” are not equivalent to each other: there is an asymmetry between them that influences how I operate in each language.

Living

When speaking to my grandparents, I am acutely aware of the asymmetry in my fluency. Unlike conversations with my parents or other Bengalis my age, I cannot resort to English loan words or the language itself at all in conversation. I rely entirely on the limited arsenal I possess in my mother tongue, which is frustrating. It means topics of conversation are semi-limited to baseline feelings and daily routines instead of what I’m studying or what I’m thinking. “How was your day?” is a question that yields itself many answers in English. I can respond with a detailed recap of my coursework, a proper evaluation of why and how the cafe food I purchased wasn’t worth it, or a thorough complaint about my teammates on a group project. In Bangla, the recap isn’t as detailed, the cafe food was simply overpriced, and my teammates just suck. When my grandparents and I converse in English, the script is flipped. Now I have the luxury of eloquence, but they have the burden of articulation. Every conversation, no matter the language, is a Sisyphean attempt at perfect communication from both sides.

I often wonder how my

in two

worlds:

Navigating Chronic Illness and Invisible Disability

Living with a chronic illness in a latestage capitalist, ableist society gives rise to various complexities. There are many metaphors that explore the reality of existing in the midpoint between these dualities, including Susan Sontag’s conceptualisation of the realms of the “Kingdom of the Sick” and “The Kingdom of the Well”. Individuals, not just those who live with chronic illness, spend their lives traveling between these two worlds — constantly trying to reconcile their identities. Societal attitudes and structures intersect with the experience of illness to privilege productivity over wellbeing, pay attention to visible more than invisible illnesses, and separate the private and public experience of illness — i.e. the way you are treated by friends, family and the medical system.

Individuals with chronic illness also navigate dualities that are both positive and negative. For example, Sontag delves into the duality of hope

and uncertainty that accompanies a diagnosis of a serious illness. This is seen when Sontag writes that, “Illness is the night side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.” People with disabilities often seek to maintain hope, yet the unpredictability of illness can lead to a constant oscillation between optimism and anxiety.