ENDINGS

the page turner/ issue 3

A STAHS English magazine that reviews and explores the themes and ideas in literature that shape the world around us

the page turner/ issue 3

A STAHS English magazine that reviews and explores the themes and ideas in literature that shape the world around us

As the editors, we would like to issue a warm welcome to the third issue of The Page Turner We hope that you enjoy reading this magazine as much as we enjoyed putting it together. This year’s theme is ‘Endings’, which we thought to be an apt title to explore how meanings are shaped in literature and real life After all, is an ending not often the most memorable moment of a text, or a death often the most defining moment of a life?

In this year’s issue, we have a satisfying mix of biographical, analytical and creative writing, which we believe highlight the variety of ‘Endings’ that impact literature as a whole Above all, we hope that reading this magazine encourages contemplation about the endings you have read or experienced, within or without literature

Romy Davies and Lucy Harris

cussionsSurrounding ts’Death ucyHarris

Closure: cretHistory

PAGES11-13

WhyDoDifferent PeopleLikeDifferent Endings? ByRosanTrisic

CreativeWriting: WavingGoodbye ByAliceFinnie

ByAanyaApte

A surprise ending is when a plot twist occurs towards the end of the novel, that changes the reader’s opinion of previous events The purpose of surprise endings can be to subvert the reader’s expectations of a genre, tie up loose ends within the plot of a novel or perhaps simply to shock or please the reader.

Whilst surprise endings can certainly be annoying at times (I know that we all hate the “and it was all a dream” ending), when done correctly they can be incredibly effective, leaving readers in awe This is displayed particularly well across the genre of crime fiction, as they effectively serve the purpose to shock the reader.

The emergence of crime fiction skyrocketed in the early 19th century, when Victorian, sensationalised stories of murder and crime cases became public knowledge via the growth of newspapers, photographs and the media. The crucial point of interest in the case was the ending; the point at which the plot twist would always be placed By deliberately laying out the stories and articles in this manner, readers became addicted to the rush of adrenaline that came from the surprise reveal they knew that characterised the stories that they loved. Such endings included a range of possibilities: an unexpected murderer, misjudged deaths and an unassuming suspect all making up the big reveal. Notably this is characterised in Sherlock Holmes - the greatest detective of all time.

Conan Doyle uses a mixture of concrete finality in his endings, through the neat tie-up and dramatic reveal of the killer with sprinklings of science to make readers feel dumbfounded yet intelligent at the same time, as well as a little ambiguity to allow the characters of Holmes and Watson to be reborn across sequels and allow them to be placed within various criminal scenarios as detectives

This is perhaps most prominent in the novel The Final Problem, published in 1893, in which Holmes and Moriarty face off at the Reichenbach Falls and Holmes ultimately meets his end and dies. However, even in this Holmes did not remain in an ending with complete totality and finality.

Thiswasbecauseaftertheendof SherlockHolmes,ConanDoylesawa significantreductioninhisincomeand furthermorethewiderpopulation mournedthelossofHolmesaswell,with thenewspapersevengoingsofarasto publishanobituaryforhim.Ultimately, theseallledtoSherlockHolmes’returnin thenovelaptlynamedTheReturnof SherlockHolmes. However,crimefictionwasthoughtto havetrulyreacheditspeakintheearly 20thcenturybecauseofthechangeof thetypicalendingofthegenre,writtenby the‘QueenofCrime’AgathaChristie This iswidelyregardedtohavebeendone especiallywellinTheMurderofRoger Ackroyd.Inthenovel,Dr.Sheppard narratesthecircumstancessurrounding themurderofRogerAckroyd,whowas apparentlyclosetodiscoveringthetruth abouthisfriend’sblackmailer.Ina shockingtwisttowardstheendofthe novel,itisrevealedthatDr.Sheppardwas infactthemurdererallalong.

This ending is regarded as one of the best and most famous endings because of Christie’s genius setup of her endings that follow a set theme across all of her novels, which makes them truly iconic and timeless. Although Christie's ingenuity towards the plot and the placementofthemtowardstheendingofthenovelswas not what reinvented crime fiction. It was in fact her setting.

Unlike her counterparts, Christie did not stage her reveals in an abandoned alley or on the edge of a waterfalloratapolicecell-shepickedthedrawingroom. The drawing room typically connotes the home and hearth, the centre of family life and a place in which kindness and love are supposed to dwell Therefore, by Christie placing the reveal of such a horrific and ghastly and shocking event within such an intimate setting could be seen to take the adrenaline rush provided to readers through crime fiction and increase it, by adding in a new level of eeriness and discomfort as everyone is awareofthatkindofsetting.

In conclusion, the power a well-written ending holds in crime fiction is undoubtable, as it truly has the power to make or break the novel and as we have previously seen through famous novels of the past, the ending of crime fiction is ever-changing, so we can only wait with baited breathtoseewhatthenexttwistinthegenrewillbe.

ByAanyaApte

ByLucyHarris

In the span of 6 years, John Keats published only 54 poems. These fit neatly into 3 slim volumes as well as a few magazines and managed to secure his place as one of the most famous British poets in literary history Despite his renown today, John Keats died at the tender age of 25 believing his life’s work and name would inevitably fade into obscurity, lost to time as with countless poets before him.

It might be surprising to some to consider that, originally, Keats wasn’t even associated with the other major Romantic poets. Rather, he was looked down upon and viewed by some critics as a ‘vulgar Cockney poetaster’ capable of only ‘the most incongruous ideas in the most uncouth language’. Indeed, by the end of his life, it seemed that Keats had managed to achieve only moderate success in the literary world.

John Keats came from a socially modest background as the son of a livery-stable manager. At school, he was popular but reported to be fairly unambitious in his studies up until 1809 when, suddenly, he began to delve into literature In the father of his childhood friend, a headmaster’s son, Keats found a mentor who encouraged his literary aspirations. Yet despite this, he experienced little formal literary education; instead, he trained to be a surgeon, undertaking a position at Guy’s hospital in London as a junior house surgeon. Only in 1817 did Keats decide to fully pursue his poetry as a career. He published his first volume of poems later that year and then left for the Isle of Wight, determined to work on his first long poem, titled Endymion. Though the reception of Endymion could hardly be considered a success, Keats continued to write, exploring his ideas with more and more fervour The year 1819 brought about the fruit of his efforts, being the year he wrote most of his most famous poems including his odes, as well as Lamia, The Eve of St. Agnes and the epic, Hyperion. What should have been the beginning of a blooming career, however, was soon to be cut tragically short

In February 1820, John Keats returned to the house he shared with Charles Brown having suffered a lung haemorrhage; he was frantic and convinced that he was dying. Indeed, Keats recognised his symptoms long before they proved fatal. Just two years earlier, he had nursed his dying brother through the final stages of tuberculosis as he had their mother before him. It comes as no surprise then that Keats immediately understood the implications of the blood he found himself coughing up After being helped to bed by his housemate, Keats told Brown, ‘I know the colour of that blood; it is arterial blood and I must die ’ Although Keats did appear to recover from this initial attack, his health was never the same and he died just over a year later.

By the autumn of 1820, Keats’ tuberculosis had developed to the point that it was deemed unsafe for him to remain in England for another cold winter. On medical advice, he left for Rome accompanied by Joseph Severn, a young painter who would look after him in his failing health. They rented two small rooms just above the Spanish Steps in 26 Piazza di Spagna now a museum called the Keats-Shelley House, which is dedicated both to him and his fellow Romantic Percy Bysshe Shelley. There’s no doubt that Keats and his friend Severn were aware of his oncoming death. It’s likely they both knew on their arrival that this apartment would be Keats’ final dwelling place

What’s perhaps less clear is just how Keats felt in the face of his impending decline Keats was no stranger to death as mentioned previously, he’d been

familiar with it in childhood and fascinated with mortality throughout his poetic career but he was equally concerned with the subject of art and beauty. In his poems, the immortality of nature is lauded numerous times, threaded throughout his work, and he affords a similar eternal quality to art like music and sculpture He seems to find comfort in the idea that the art humans leave behind will outlast their short lives What Keats did lament, however, is that he had not succeeded from his point of view in creating any such art. He claimed, ‘I have left no immortal work behind me nothing to make my friends proud of my memory but I have lov’d the principle of beauty in all things, and if I had had time, I would have made myself remember’d’ In light of these words, Keats appears resigned to his death but not necessarily embittered or even afraid. During his final days, Keats even sent Severn to the cemetery he would be buried in, from which Severn returned with news of how ‘peaceful’ a place it was. Keats spoke expectantly of the ‘quiet grave’ that awaited him and, rather than with a fear of death, Severn’s writings are infused with a sense of the stark grief Keats felt over the ‘posthumous existence’ his sickness had reduced him to.

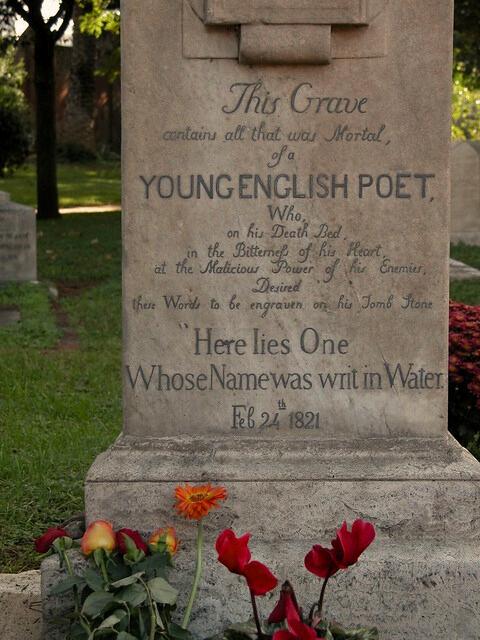

Not only was Keats aware of his oncoming death, he faced it with the belief that his poetry had so far been for nothing. Perhaps this explains why Keats asked that his grave be left anonymous, with only a simple carving on its gravestone: ‘Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water ’

With this last request, Keats sparks an interesting discussion on his philosophy at the time of his death. Did he mean this epitaph in anger? As a protest against the perceived futility of his work and the time which would wash it all away without leaving a trace? Conversely, could we see this as evidence of resignation or even an attempt to find peace with the ultimate impermanence of existence? Keats proposed the idea of negative capability the ability of the poet to accept ‘uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason’ so maybe he leaves his message purposefully ambiguous, understanding at once the unfairness of his ending, the tragedy and the impossibility of expressing the full complexity of his emotions.

In the end, it matters little what his precise intentions were, as his heartbroken friends, blaming Keats’ rapid decline in health on the brutal criticism he faced, carved their own striking message alongside Keats’ own. What is written today on Keats’ gravestone is this:

‘This grave contains all that was Mortal of a Young English Poet Who on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his Heart at the Malicious Power of his Enemies Desired these Words to be engraven on his Tomb Stone: Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water 24 February 1821 ’

This has had the effect of greatly obscuring full understanding of Keats’ death As appreciation of Keats’ work grew, so did this image of the fragile genius of John Keats, brought down by ‘the malicious power of his enemies’. Lord Byron satirised the same idea in his poem Don Juan in which he wrote, ‘Tis strange the mind, that very fiery particle / Should let itself be snuffed out by an article ’

However, this concept nonetheless persists. Many see Keats’ life and death as encapsulating Romantic notions, and equally general romantic ideas – and therefore Keats as the epitome of the Romantic poet. The tale of a young, sensitive poet driven by a harsh society to a tragically early death could be said to exemplify this, potentially explaining why it has remained so popular an idea

Despite how we may choose to interpret the epitaph, it’s obvious that history has since proved his fears unfounded. Recognition of Keats bloomed after his death and throughout the 18th century. During the Victorian era, Keats was greatly admired, inspiring Pre-Raphaelite painters and countless Romantic poets alike. Today, Keats remains one of the most influential figures of early 18th century Romanticism as well as of English lyric poetry as a whole. In Keats’ poetry, readers will find a quality not unlike that of Shakespeare’s sonnets, that invigorates and moves, rendering his poems undoubtedly timeless.

Despite Keats’ fears or his friends’ anger, we can confidently say that memory of him will never be lost to obscurity or carried away on time’s waters Whether it is carved on his gravestone or not, Keats is a name forever marked in British literary history.

By Lucy Harris

Many will recognise the opening line of Donna Tartt’s ‘The Secret History’ Few, however, take the time to contemplate how this beginning connects to and reflects its obverse, the ending, where the principle questions Tartt asks through the novel are cemented in place.

Tartt’s novel is a complex exploration of class, morality, and above all, human nature. In its pages we see the characters, through the lens of the deeply unreliable and displaced narrator of Richard Papen, live a seemingly idyllic life, self-constrained to their small circle of six classics students at Hampden College: Charles, Camilla, Henry, Francis and Bunny Each of these characters is unusual in their own right, the most enticing of whom arguably being the charismatic, intelligent and self-assured Henry.

The illusion of their harmony of lifestyle, punctuated by Richard’s longing to fit into the upper-class loftiness of his peers, gradually deteriorates through the novel as terrible secrets are unveiled and threats made between friends. By the middle of the novel, Bunny is indeed dead as the opening line promises us, murdered by his five friends to keep their darkest secret unspoken; the aftermath of this, however, is where Tartt begins to form her lasting impression.

Slowly but surely, the remaining friends each reach a state of degradation, descending into paranoia, alcoholism and drug abuse as the guilt and terror consequent of murder catches up to them.

This reaches a tragic crescendo as Henry, the instigator of the group’s criminal undertakings, commits suicide after Charles discovers he has been sleeping with his sister, an altercation in which Richard is shot in the crossfire.

What follows is the epilogue, which informs us not only of the ugly reality of these characters but also reminds us of Richard’s “fatal flaw”, which he himself is able to acknowledge as “a morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs”. Here, perhaps, lies Tartt’s lingering question that she asks us with her final words, throwing into ambiguity for her readers whether we can trust a word of Richard’s story, and indeed calling us to question our own tendency to romanticise. Have we, perhaps, found ourselves caught up in the captivating, enticing allure of passion and misdeeds, just as the protagonist has?

Our first shock of the epilogue is Richard’s survival and recovery from his shooting at the end of the last chapter. Here, Tartt reveals how cleverly she has wrapped us up in Richard’s narrative tunnel vision. Despite the obvious physical ramifications of a gunshot wound, the prospect of life without Richard’s tightly enclosed group of friends is just as surprising to us as his recovery. They have, up to this point in the novel, formed the lifeblood of the novel’s compulsion just as they have tethered Richard to his life in Hampton As such, the drifting of the group is almost another death, certainly another loss, following that of Henry. Equally, we understand it as inevitable, with Henry being the “thread which bound [them]”, now “abruptly severed”.

The matter of Henry himself is perhaps the most prominent thread of the epilogue; in death, he is no longer as infallible as Richard had perceived. Left to his own devices, Richard is forced to confront his failures as he is no longer following the guidance of his intensely alluring friends Tartt summarises this clearly in Richard’s melancholic pronouncement, describing him as “the bystander which [he] so essentially [is]”. Similar self-reflection is reached by the other remaining friends, with Francis desperately imploring Richard to “forgive” him “for all the things [he] did but mostly for the ones that [he] did not”.

Once again, Tartt explores the effects of guilt of nonaction and how one’s moral compass, often obscured in the heat of the moment, can catch up to you in time. Perhaps, even, the collusion of Richard’s group is intended to convey the potential influence of others on one’s actions. Alone, we may not be ‘bad’ people, but how much can the group be blamed over the individual? Francis’ mention of “sin” perhaps draws our attention once again to the unavoidable matter that these characters have done bad things, while they may not be bad people.

Through this exploration, Tartt implores us to question if Richard is, indeed, deserving of blame as a “bystander” and consequently inspires a lingering selfreflection of our own responsibility in her novel’s ending.

Even in this state of acknowledgement, Richard’s “fatal flaw”(as well as those of his friends) is ever-present. Their foolish over-ambition leaks into their failure to accept tragic reality, still “expecting Henry to show up” and they remain almost living in the past, recalling the words of Bunny and their teacher, Julian, alike. Camilla and Richard share a moment where she professes to still love Henry, despite his death, after Richard’s fumbling love confession. Tartt thus leaves us with the distinct impression of crushing inertia; this group will live forever in the past, rooted there by their actions, perhaps as a sort of penance for their unpunished deeds. Camilla remains cold and impenetrable to Rich and smo

Finally, the last scene of the epilogue is that of a haunting and mystifying dream. Tartt portrays Henry, now long dead, appearing in Richard’s dream “steady and impassive” as he was in life The only difference is the bullet hole faintly visible on his temple. When questioned about his death, Henry asserts that he is “not dead”, only “having a bit of trouble with [his] passport”. On the surface a bizarre encounter, accompanied with the preceding reference to Achilles’ dream of Patroklos after his death, Tartt arguably makes a concluding statement on Richard’s “fatal flaw”. His infatuation with beauty is, in the end, that which continually drives him, and in his desire to romanticise he perhaps turns to Classics as a mechanism of finding it in hardship After all, why else does the phrase “beauty is pain” stick in his mind but to comfort, to falsely justify the depth of his guilt?

Furthermore, Henry’s appearance in Richard’s dream may not be an effect of grief but a manifestation of his idolisation, elevating him in death from human to almost divine, just as the Ancient Greek gods could appear to mortals in dreams.

Richard’s role as the observer is further cemented by his ineffectual presence in this moment, whilst Henry’s is affirmed as being the ever-ambiguous representationofRichard’saspirationsanddesires Of course, Henry himself is not a god, nor even a ‘good’ person, only an affluent and compelling character that draws working-class and friendless Richardinwhollyandinescapably.

Yet his presence as the lingering figure, walking away from Richard is a fitting end to a novel all about morality and corruption, illusion and reality, both of which are displayed in varying capacities in Henry himself. Tartt reinforces, with resounding finality, the human capacity for self-deception and warns against moral insensibility, harking back to the first line of the first chapter where we are asked about the existence of a “fatal flaw” In the end, Tarttleavesustoformourownresponseinaworld still lingering in the elitism and immorality as our predecessors.

ByRomyDavies

Fastening the buttons of her ash-grey uniform, she bit her tongue for the third time that morning, her mind too preoccupied to notice the rogue hairs that had escaped her sleek bun. Her appearance was the least of her concerns. A few negative points were nothing compared to the punishment that would be inflicted upon her if the launch failed. Glancing over at the desk in the corner of her room, her gaze snagged on the sheets and sheets of paper where rows of calculations sat completed. They were correct; they had to be correct.

Before she could fall into the chasms of anxiety forged in her mind, the door to her room slid open, revealing a tall young man Just above his heart sat a small tablet, the number 990 proudly displayed on it. With his impeccable uniform and tidy haircut, she was unsurprised that he had a near perfect score.

“Professor?” He asked, his eyes fixed on the ground, “Are you ready?”

She found herself nodding, and he stepped backwards to reveal three more men, similarly attired, waiting to escort her. She followed them as they snaked through the labyrinth of corridors, past laboratories and garages - all of them deserteduntil they reached a set of huge metal doors that seemed to almost peer down at her After a few moments, they clanged open.

The first thing that struck her was the air. When she had been a little girl, playing outside as the sun’s rays had beaten down upon her, she had never really appreciated the freshness of the air in her lungs. The gentle wind that tugged playfully at her hair. Now, taking a deep breath, she stepped outside, as that same wind whispered violently in her ears, her lungs sore as they tried to capture the little oxygen left in the air.

She allowed herself a moment to glance across the desert-like plain, sand dancing at her feet in the wind. How, she thought, had it come to this? How could she be one of the last people ever to inhabit this planet? One of the last people to call it their home? Before she could lose herself in her thoughts, one of the men gestured to the launch facility ahead of them, a piece of cloth pressed to his mouth. He was right not to want to breathe the contaminated air. Her feet dragged her across the sand and up to the facility door, where more guards greeted her.

ByAliceFinnie

Though she spent practically every day inside the facility, the vast expanse of space - a luxury duetooverpopulation-stillmadeherjawdrop.It seemed especially empty today, now that all their supplies had been loaded into the space vessel. After they had gone, she realised, it wouldbeemptyforever;alifeless,hollowshellof a building. The thought made her shoulders begin to quake uncontrollably. Suddenly, a thoughtsprungintoherhead,butshedismissed itentirely

“Professor?” Her escorts all saluted the uniformed man who addressed her, his chest proudly displaying tens of badges and awards. The number next to them read 998. She was not surprised that, on the day of the final launch, this Colonel had received one of the highest scores everpublished.“Iseverythinginorder?”

“Ibelieveso,sir.”

“Youbelieveso,Professor?”

Yes, sir,” she replied, ignoring his tone. “I ran through the calculations last night and everything seems to add up ” He nodded slowly, gesturing for his men to start boarding. His eyes ran over her face, as if he was examining every cell of it under a microscope. After a moment of agonising silence, he stumbled back slightly, his mask cracking, before the stern expression that she had to come to associate with him returned. “Program in the launch, Professor,” he ordered, before turning to direct his men. She dipped her head in recognition and then felt her feet drag her to a small room where the control panel sat The sea of brightly coloured knobs and buttons usually required little extra thought - she had dedicated years of her life to creating it; it would take more than a night’s restless sleep to erase that - but her head could not focus. Instead, her attention lingered on the last few rows of soldiers waiting to board. None of them, she realised, understood the significance of this moment. Some of them were too young to comprehend the reality of what they were leaving behind as a species. The history that stretched back thousands of years Others were too focused on the promise of a new future, of new opportunities, to mourn what they were losing.

Unlike many of them, she had no one waiting for her on the other side. Too many years dedicated to saving their species had cost her the people she had loved the most. None of those people had lived to see the future that she had built for them.

As her fingers hovered above the buttons, she locked eyes with the Colonel. A moment of understanding passed between them

A whirring sound filled the air as the space vessel’s engine purred to life. Her hands clung to the control board, as she watched the craft rise into the air, breathless. She saw the young soldier who had fetched her this morning pushing to the front, his hands pressed up against the glass as he shouted at the others to help. They all looked to the Colonel, watching her for a moment before striding away from the window. She squeezed her eyes shut, letting the noise drown out any of her emotions, until the whirring had faded, replaced by the whistling of the sand outside the facility as the roof inched closed Then silence

By Alice Finnie

ByRosanTrisic

The endings of books, films and stories often have a large sway on how we feel about the media that we consume. ‘Oh, the movie was great, but the ending ruined it for me,’ is a sentence you’ve probably said or heard. Sometimes we can feel frustrated by the dissonance between the enjoyment of experiencing the art and the dislike of the ending. When discussing ‘I Who Have Never Known Men’ in Book Club, many of the group found that the ending affected their whole attitude to the book. Furthermore, the group felt that that endings in general factor greatly in how much we get out of reading a book. The results of a survey by writer and qualitative researcher Barbara Linn Probst seem to confirm this; it showed that one of the most frequently cited reasons for loving a novel, among other things, was how satisfying the ending was But this leads me to wonder, why is it that endings seem to affect us so much? And why is it that certain people receive them differently? Above I mentioned how it can feel frustrating when your recollection of a novel is ruined by the ending, even if you enjoyed the majority of the content. Psychologist Daniel Kahneman considers this conflict to be due to what he

According to Kahneman (1993), the experiencing self is the present self, the one that the Doctor approaches when asking, “Does it hurt when I touch your injury?”, and the remembering self is the one that keeps record, the one that the doctor approaches when asking, “How did it feel when you got injured?” But, as we all know, memory can be subject to bias Kahneman conducted a study in the 1990s, in which patients underwent a colonoscopy and were asked to report their pain on a 10-point scale every 60 seconds. In group A the procedure was longer and more painful for the participants than those in group B. However, when asked about the overall experience of pain after the procedure, patients in group B had a much worse memory of the colonoscopy than those in group A.

Why was this, when objectively one experienced more pain than the other? Well, the ending of the experience had a huge impact on the memory as a whole. It was found that when the patient experienced a spike in pain towards the end of their colonoscopy, even if it was shorter and had lower pain overall, they reported an overall worse experiencethanthepatientwhohadmorepainbuta consistentlevelofitthewholewaythrough..

Kahneman put this difference between the perspective of the experiencing self and the remembering self down to the purpose of memory; to tell a story, that we may learn from it, and inform our decisions by picturing the future as ‘anticipated memories’ He viewed the remembering self as the one who takes the highlights of our everyday lives and shapes them into a narrative. The remembering self, therefore, will be the one to choose whether and how to have that colonoscopy again (for example). Indeed,Kahnemanfoundthattherateofparticipants returning for a colonoscopy was higher in the participants who had a better memory of it but a worseoverallexperience(GroupA).

When reading about this, I found myself comparing storytelling and memory. From an anthropological perspective, stories can be viewed as the memories of those that have survived - instruction manuals to help us do the same. Fables such as Little Red Riding Hood teach us about keeping on the path, Myths of Tantalus and Sisyphus about the danger of hubris. Through linguistic analysis, researchers havetracked certain stories such as Jack and the Beanstalk through Slavic and Celtic languages, concluding that some tales may be up to 6,000 years old! This means that we are passing on information that was deemed valuable even in Proto-Western-Indo-European life. In the words of Margaret Atwood, storytelling is quite literally ‘builtintothehumanplan.Wecomewithit.’ So, what does all of this have to do with the last few pages of a book? Well, since we use memories, like stories, to help us understand the meaning of an experience and direct our behaviourinthefuture,woulditbereasonableto conclude that our emotional response to endings in everyday life mirrors how we respond toendingsinstories?

University of Cincinnati’s Heather Vough and colleagues (2015) proposed that the particular ending of retirement creates psychological challenges because it forces us “off script.” It also requires us to form a new self perception, something that Vough and her team describe as “sensemaking”, in which the event can become a part of their “life narrative” In interviewing 48 Baby Boom Canadian retirees, all employed in companies in the private sector, Vough et al. found that an individual’s sense of self was largely impacted through the type of ‘careerendingnarrative’,ofwhichtheyidentifiedsix.

Among these were ‘cashing out’, when the retiree was offered an incentive or wanted to get out of the company for a particular opportunity, and ‘being discarded’, when individuals felt that they were no longer needed or were actually laid off. Vough et al. organised the types of endings and into ‘identity opportunities’ and ‘identity threats’. Interestingly, though the ‘narrative’ of the ending greatly influenced personal takeaways and identity re-evaluations, the study found that therewasstillvariationbetweenindividuals.They proposed that the situational constraints ‘orients our attention towards the subjective meanings’, but that it was down to the individual the extent and manner in which this affected them. In other words, the biggest determiner in how they respondedwasthemannerinwhichtheyleft,but factors personal to the individual were also at play. I feel this makes sense; an employee has a similar trust-based relationship with their employer as a reader has to their author. As such, howwerespondtotheendofajob-ortheendof anovel-isdowntohowthatendisexecutedand our individual world view. For example, a breakup may lead you to become introspective and understand more about your priorities in life. Alternatively, you could commit to the ‘being discarded’ narrative and cope by vilifying the partnerwholeftyou.

So, if our responses to certain endings depend on boththe‘category’ofendingandoursenseofself,itis possible that those are the factors that may determine how we respond to the ending of a novel. For example, a classical or resolved ending, in which all ‘loose threads’ are tied up and the events are totally resolved, often leaves the reader with a sense of harmony, neatness and satisfaction. As a result, they are often used for complicated farces or for romance fiction. To compare this to Vough’s six narratives, it could be compared to “following a script”, in which a career comes to a natural conclusion due to age or length of employment, which leads to acceptance more completely and quickly, not requiring much self analysis or ‘sensemaking’. Another ending might be utilised to have a more discordant, and, as a result, thought-provoking ending, such as the implied or open ended ending, common in contemporary literature This may require the reader to look more closely at the hints left behind by the author, possibly leadingtoagreaterpersonalresonance.

Of course, there is a large amount of nuance in all storytelling, and certainly real life endings are not fully synonymous to the endings of books; one (real life) is unavoidable and material, and the other (reading a story’s ending) is a vicarious experience, the strength of which is determined by your engagement. However, the reason we feel so deeply impacted by stories ending may be because the ending of an experience, like in real life, causes us to cognitively reset and re-evaluate both our sense of self and, indeed,theworldaroundus.

ByRosanTrisic

StAlbansHighSchoolforGirls TownsendAvenue,StAlbans, HertfordshireAL13SJ info@stahsorguk stahsorguk