Tall tales and short stories

Dedication

This little book is dedicated to people who love travel; to those who recognise its value and importance to the world around them. To those who travel generously, who seek to give as well as take, who seek to learn and to listen and to conserve and protect. To those who travel in fellowship, who recognise responsibility and the importance of respect, who see the meeting of new people in new places on equal terms as the privilege it truly is.

It’s for those who find inspiration in their now; in sunsets and in sunflowers, who seek presence, who

Foreword

For over 30 years, members of the Steppes Travel team have travelled the world, exploring, listening and learning. They do it for our clients, to make sure that the holiday experiences they create become Beautiful Adventures filled with remarkable, life changing moments.

understand that their travels, their trips, their holidays, aren’t simply about them, they’re fragments of a much bigger picture, a grand tapestry of comprehension that one day, we hope, will bring us close enough to find the answers we all seek. It’s for those who appreciate the good and the bad with the ugly and are willing to find something beautiful and positive in all three, existing in the knowledge that the world can only be truly understood by those who have seen it with their eyes wide open.

Our kind of travellers. This is for them.

They do it for love, for our planet, for flora, for fauna and the people they meet along the way. These are some of their memories. Enjoy them as they did, and go forth to make more of your own.

Discover Extraordinary.

Shrouded in mists

by Chris JohnstonI am driving through a sandstorm on a scuffed salt track in Namibia. The name of the park surrounding me translates as ‘dry land’. The windows of the 4x4 are wound up tight and the air con is off, but I can still taste the desert.

Through the haze I can just make out a group of pale pink flamingos, huddling together in a small lagoon. On the other side I glimpse ghostly wrecks straining against the pounding Atlantic. Up ahead, there is a dry estuary filled with dust and rocks, waiting for water that never comes.

This is not one of the country’s famous parks, but a 35-kilometre-long coastal drive between two of Namibia’s fastest growing towns. Behind me is Walvis Bay – an increasingly industrial but commercially important deep water port, and home to the most delicious oysters. Ahead lies Namibia’s holiday town of Swakopmund. The two places could not be more different, but even on this short journey you find some of the country’s most expensive real estate. Namibia makes its presence felt.

Namib, meaning vast place, tells you everything you need to know. If there is one place that looms large in people’s imagination

and stories

when they think of Namibia, it is undoubtedly the Skeleton Coast. This 16,000-kilometre-long stretch of wild coast, from the Swakop River to the border with Angola, covers nearly a third of the country’s coastline. Often described as a desolate wasteland of bleached bones and rusting wrecks, a land picked clean by scavengers and shrouded in mists and stories, it has a fierce reputation. My journey revealed quite the opposite: a hypnotic landscape, the sculpted, pale dunes softer than those in the fiery south.

As I step out of the 4x4, I look out over a shimmering sea of demerara dunes and the Atlantic Ocean, silvery in the distance. The fresh sea breeze over the surface of the land creates a strange, sandy mist in constant motion. My mind plays tricks as land, sea and sky blur into one, making me feel as though I am floating. I reach down, letting the grains of the sand brush the tips of my fingers, if only to reassure me that I am in fact awake.

I soon leave the dunes and drive down into a small canyon, watching in disbelief as rivers of sand cascade from the cliff tops, dusting the rocky fig trees growing in the cracks below. A lone bull elephant greets us, his

tusks brilliant white against the pale dunes behind him. He was drawn to the spring here, a lush green oasis in stark contrast to the parched surroundings. Dozens of beautiful oryx are also slaking their thirst. Our journey took us south to the scorched NamibRand Reserve – the oldest desert in the world. I arrive at a private reserve late in the afternoon, where the rolling mountains, vast plains and endless desert scenery is as dazzling as Sossusvlei itself, without the crowds. The distant hills, rich in quartz, sparkle in the setting sun, their lengthening shadows creeping across the vast steppe.

The scale of the scenery is so vast it is almost incomprehensible, but before long, the Daliesque landscape has worked its magic. I watch in awe as virga rain falls, evaporating mid-air, never reaching the baked earth. Rainbows and electrical storms hang suspended over distant peaks. A family of bat-eared foxes darts across the plains, which are covered in mysterious fairy circles. No one seems to know their origin. Fungi, gases, meteorites, even aliens have all been suggested as possible causes, but science has yet to offer a conclusive explanation.

The day turns to night as we gather around the campfire. I mention the circles to my local Damara guide, Papa G. As is often the way, local knowledge

trumps all and his explanation was as simple as it was sublime.

“People say this is the land God made in his anger, but they do not understand. When God made Namibia, he was so moved by his creation that he wept. His tears fell from heaven where they remain to this day”.

Looking up at the night sky, the Milky Way ablaze, there is indeed something of the celestial in this vast place.

My favourite place on Earth

by Roxy DukesFlying over the west coast mountains

I feel at home. I am heading back into the depths of British Columbia, my favourite place on Earth. Having travelled to Canada countless times, and being a self-confessed bear lover, the Great Bear Rainforest is always top of my list to visit. So when asked if I wanted to head back, I threw on my outdoor gear quicker than you could say maple syrup.

My trip so far has already taken me to the crème de la crème of wilderness lodges dotted along the west coast, but now I am heading to Nimmo Bay Wilderness Resort which is, without doubt, the cherry on top.

Set on the edge of the Great Bear Rainforest to the north of Vancouver Island, Nimmo Bay is a part floating, part stilted lodge set on the water and framed by the forested mountains. I am making the journey to the lodge in a little Cessna full of luggage. I’ve even donned a headset: this is where the excitement ramps up. Low-lying clouds often leave the coastline and mountain peaks shrouded from view, but from up here you can appreciate the vastness.

I jabber to the pilot who was amused to tell me I had already met his

girlfriend just an hour ago when I frantically asked for some directions to the airport; she had called ahead to tell him I might be late! Despite the vast scale, this is small-town Canada so everyone knows everyone’s business.

Banking around the side of a mountain, I recognised immediately where we were. Slowly the pilot made the necessary moves and we glided down towards the water, cutting the surface like a knife to butter. Into view came the striking red roofs of the stilted cabins and the floating lodge beyond.

Greeted by the friendly team, I immediately felt at home. After quick introductions, I found myself tying the laces on my hiking boots and heading off into the forest for a ‘hike to the top’. This was a route that was only just being tested out and they were excited to trial me as a guinea pig. Winding through ancient spruce trees, crawling over mossy logs and scrambling up the soft woodland slopes – this is my kind of adventure.

The forest is magical; shrouded by the canopy above, the mossy forest floor had once been described as a ‘decadent’ forest. It was far from it,

rich and alive with flora and fauna. As I reach the top, I am gifted with sweeping views across the inlet and the surrounding mountains. Just a tiny boat could be seen in the distance, perhaps a local fishing boat, I wonder.

Over the following days I explore both the forest and ocean in turn. I seize the opportunity of a coastal day cruise to explore inlets of the Broughton Archipelago and the Great Bear Rainforest. Cruising through the spectacular scenery of the mountains that tower above, I needn’t have found anything at all but this is not a region that disappoints. During the day we caught sight of Dall’s porpoise, seals, humpbacks and a pod of twenty or more dolphins which danced merrily in the wake of our boat.

Food is an integral part of the experience at Nimmo. Their appreciation of the need for balance and a sustainable approach sparked my interest, so I joined them on an early morning forage by boat. The chef described how the menu is designed to use the ingredients from both forest and ocean when they are in season to include spot prawns, halibut and crab. This morning we were out to collect some sea kelp that is used both in the food and wellness experiences at the lodge. I am told of its vital importance to protect these undersea forests that shelter a huge variety of plants and animals on this coastline.

In the afternoon, we took time out for a picnic lunch set on the lodge’s floating pontoon in a tiny remote inlet. This is where Nimmo oozes style. Stuffing myself on fresh crab salad and tasty cheesecake, I gaze out onto the water’s edge and I spot a big black rock… a moving big black rock that appeared seemingly from nowhere. I grab at my binoculars and peer through to see a beautiful black bear digging away at the rocks in search of his meal – perhaps he plans to feast on a crab salad like me?

The missing piece of my puzzle

by Kate Hitchen

I’m pinching myself as I listen to Bhutanese music being pumped around the aircraft, while I begin the descent into a valley somewhere close to Paro, Bhutan.

The wings almost brush the sides of the valley and scrape the tips of the trees. The tin roofs come into focus. I can sense the precision this landing takes. I love flying but it suddenly dawns on me what the calming music is all about.

This is it. I’ve arrived outside an exquisitely painted façade, with fine detail that looks more akin to a museum of culture than an international airport. The strong wooden structure sits on a vast expanse of tarmac. I am instantly intrigued. If the intricate design of a utilitarian building is this important to a country, what treats of craftsmanship are in store for me on this journey?

I see exquisite detail everywhere. In the way the national dress (Gho for men and Kira for women) is worn, in the tiny badges depicting the royal family, which are carefully pinned to the chests of almost everyone I meet, and in the phallic symbols adorning the sides of homes and shops, that are so detailed they bring out the prude in me. It appears everything has been considered. Even a commitment to maintaining collective happiness and to environmental conservation. Not a political goal, but a way of life.

A way of life that is rapidly changing. While taking a well-earned rest at a café halfway to Tiger’s Nest Monastery, I notice a group of giggling young men crowded around a phone.

“5G is no problem up here,” Ugyen, my guide, explains with raised eyebrows.

It is hard to believe that on my drive to work each day I can’t make calls from my mobile phone, but at 2,920 metres above sea level in a remote area of the Indian Subcontinent, Instagram is well within reach.

Thinley, a young monk I meet, explains that at his monastery, mobile phones are allowed on Sundays, but only for the older boys. It throws up so many questions in my mind. Not least because I have boys myself and the worry of social media is real. But what will happen to the ideals of a remote mountain kingdom when the focus of generations to come is pulled elsewhere? Can collective happiness still be achieved? Will less time be spent considering the details?

All I know for now is that I am grateful my jigsaw puzzle is finally complete and maybe if I fast forward years from now, I might be lucky enough to visit again and get the answers to the questions playing on my mind.

A different Asia

by Paul Craven

I have been travelling to China ever since my backpacker days, way back in the early 80s. And while I’m always happy to share my experiences from across Asia, talking about China is something that continues to grip me.

I am visiting the Gansu and Qinghai provinces in central China. This is a genuine treat, as our leader is an expert on Miao and Tibetan costumes. Travelling to this remote region offers a chance to see a different side of the country – one away from the crowds, which are often so hard to escape –and to get amongst Tibetan people, yaks and the simplicity on offer. It’s too far out for most tourists and is delightfully peaceful because of this.

A highlight of the tour is the two-day Shaman Festival. Moving from place to place, this festival offers a different perspective on Buddhism compared to what is usually found in the area. The festival itself is enthralling and a hive of non-stop activity. The shamans, accompanied by their helpers, appear in the courtyard. They all seem to froth at the mouth and are completely entranced. One then separates from the group, climbs onto a parapet above the temple and pours alcohol, yoghurt and pine branches onto a fire. I stand and watch as the smoke forms thick, bulbous plumes and swirls up towards the sky.

We venture out into the festivities. The air is filled with the sound of comedy

sketches, dancing and singing. The whole scene is dotted with a flock of stilt walkers and men in paper mache masks. Colour and excitement bursts all around us.

We wander steadily throughout the day, watching the events unfold. It occurs to me that I have only seen three ‘classic’ crimson-robed monks so far. I ponder how there are few pure forms of religions surviving in Asia. Instead, many hazier hybrids coexist – much like Buddhism and Shintoism in Japan, Orthodox Christianity and Shamanism in Russia, and Buddhism and Animism in Myanmar. Often their values and beliefs crossover and creep into ways of life.

The festival continues with a frenetic energy, groups performing elaborate and hypnotic dances. Women with beautifully-plaited hair carrying huge oblongs of cloth move like robots in the courtyard. Children follow their mothers while wearing decorative costumes. This is certainly far different from many of the experiences Asia has shared with me. And I am grateful for it.

As pine-scented smoke swirls in the sky above me and singing echoes across the crowds, I realise the importance of connecting people with these little known places.

Colombian Cowboy

by John FaithfullMy horse is called Flea; a Colombian Criollo or Paso Fino descended from horses brought to South America by Spanish conquistadors and prized for their toughness and endurance, unlike me.

After an ungainly mounting experience, Flea and I canter through the gates of our Hato to be engulfed by the Colombian Llanos – vast eastern plains and wetlands that divide the Andes and Amazon. This is cattle farming country.

Today’s task is to join the Colombian herdsmen, or Llaneros, seek out, round up and corral their livestock. I fear my contribution as a relatively inexperienced horse rider will be nominal (at best) but I’m in the saddle, hugely excited and determined to be a Llanero... for a day.

We drift across the savannah, fording occasional rivers and ducking under branches, passing through stands of forest with reins grasped in one fist. Just finding the cattle in these endless plains strikes me as quite a challenge, but the Llaneros uncannily know exactly where the cattle will be and lead us directly to them.

These lads are tough. Most farm and ride in bare feet. They’ll spend

extended periods camping out as they drive cattle and their appearance has been ‘seasoned’ by time spent in this challenging environment; however, they’re anything but dour. Constantly joking, laughing, singing, whistling and playing practical jokes. It’s obvious they love their job and are exceedingly good at it – I watch them lasso a horse in a herd from twenty metres with pinpoint precision before wrestling the beast to the ground for tick-treatment and a ‘check-up’.

I line up with the Llaneros (Magnificent Seven style) as we collectively scratch chins and consider the 200 head of cattle scattered below us. There’s a very strict leadership structure here with the role of head Llanero often being passed from father to son. It’s not unusual for a fresh-faced twenty-year-old to be ordering wizened and massively experienced herdsmen, but this is accepted without question. Suddenly, decisions are made and instructions barked. I gasp for breath as Flea launches himself forward and we hurtle across the uneven landscape of mounds and rhines, heading for the furthest cattle. I’m screaming, laughing and giggling like a maniac, eyes blurred with tears as Flea enters

hyperspace and everything is green, blue and brown. We stop. I have managed to stay in the saddle. I wipe my eyes and manage to focus; I’m now part of a cordon of herdsman surrounding the cattle. In unison, the Llaneros approach the herd like a closing trawler net. The cattle begin to move and then the singing starts. Well, not so much singing as a cacophony of different songs, tunes, whistles and shouts. The cattle are serenaded, entertained and warned against breaking away as we move slowly but surely in the direction of the Hato. I sense the celebration in the noise being made by the Llaneros; the difficult part is done and before I know it I’m whooping, whistling, howling and (to my shame) singing Rawhide at the top of my voice. I’m one of the boys! I feel involved, accepted and extremely happy. Of course, there’s the occasional dash for freedom by some young pretenders but one of my fellow Llaneros immediately peels off and steers them back into the fold.

My Llanero brothers and I follow the wave of cattle into the corral and it’s with a great sense of satisfaction and pride that I close and latch the gate, but the day isn’t done. My final challenge is to select a cow and separate it from the herd. It’s with some trepidation that I plunge into the sea of cattle, but it’s one of those

moments when something clicks and awkwardness drops away. Flea and I become one and, to my amazement and without much effort, we slice through the herd and very quickly direct and isolate the chosen cow. I am a Llanero! However, getting off Flea at the end of the day was a much trickier operation than getting on.

Citadel of the Sun

by Charlotte Lawton

Sometimes referred to as the ‘Citadel of the Sun’ or the ‘Blue City’, Jodhpur is probably best known for its exceptionally well-preserved ancient fort dominating the city’s skyline.

Approaching the city, I can see the fort looming above me. My tuk tuk winds its way up the steep incline and arrives at the large, arched gate. It’s 5pm and closing time; the last of the day’s visitors have dispersed, allowing a peace to descend on the hill.

A uniformed security guard readies himself for his evening shift as the sun slides towards the line of the horizon, casting the last of its soft orange rays over the city.

I’ve come to meet the curator of the Mehrangarh Fort Museum Trust, Karni Jasol, for a private ‘after hours’ tour of the Royal family’s historical art and treasures collection. Karni greets me with a warm and genuine smile, setting the scene with fascinating stories and anecdotes about the various exhibits. His refreshing approach has me engaged from the outset. His love for the fort, its history and its people shines through every word.

We stand on the ramparts, taking in the city below. There are still half a dozen large cannons ready to deter attackers from the neighbouring armies of Jaipur. I can see the imprints of retaliatory cannonballs fired upon the fort’s façade. It would be no mean feat to launch an attack on a fortification such as this. Rajpur ruler Rao Jodha knew what he was doing when he commissioned its construction in the 15th century.

The sky turns from a burnt orange to a dark velvety blue, lights twinkle in the distance and the calls to prayer float up to join us in the night air. As we enter the fort, I am transported back to a bygone age of opulence and grandeur. A time of abundance

and a Maharaja’s rule. I can imagine the fort filled with life, with princes and princesses racing around its echoing halls. We explore vast, empty courtyards covered with intricately carved stone work, rooms filled with silver plated elephant’s howdahs and palanquins and an awesome armoury. We enter galleries containing some of the most exquisite paintings I’ve ever seen, the detail of which takes your breath away.

The prospect of my visit coming to a close intensifies my focus as we enter a series of opulent palaces, arriving in a beautifully decorated hall, the Sheesh Mahal (crystal palace). A single musician sits in the corner of the room playing an instrument that I’m unfamiliar with. The sound is beautiful and melodic. As the lights are dimmed and a few candles lit, the room transforms into a magical, glittering light show – the tiny, delicate cuts of golden glass and mirror filigree work that cover the walls refract the light into a star-like constellation. Built and created with this intention, the combination of the atmosphere and music is utterly spellbinding. Hats off to you, Rao Jodha Rathore.

Sensory overload in South Georgia

by Sue Grimwood“You have to send Sue to South Georgia – it will blow her mind.”

These words convinced my manager that my proposed three weeks out of the office was reasonable. And how glad I was. South Georgia surpassed each and every one of my expectations.

Suspense quickly built from my first sighting of Shag Rocks looming in the fog. But, a blown-out landing at Elsehul reminded me of the importance of travelling with expert captains and expedition leaders with a plan B (C and D…) Abandoned landings aren’t unusual in these parts; huge ocean swells and katabatic winds make for challenging zodiac journeys.

Landing at Right Whale Bay, I am not sure if the noise or the smell struck me first. I was under careful instruction not to approach any wildlife, especially the elephant seals, who my guide endearingly nicknamed ‘blubber slugs’.

They littered the landscape. Tightly packed groups of females congregated with tiny pups, while creches of weaners gazed with the most beseeching eyes I’d ever come

across. Colossal beachmasters, with truncated noses and faces only a mother could love, prepared to fight to keep their harem of females. Huge males would rear up and hurl themselves at each other mouths agape, teeth tearing into necks, gory and visceral but equally as spellbinding. As they battle, snorting and roaring, flailing their nostrils, they let out pungent belches that reek of decaying fish. Meanwhile, less offensively smelling characters nip in to tempt the females, but at their own risk. Given the right motivation, beachmasters can move at a somewhat surprising speed, lolloping along as great ripples of blubber kick up the black sand.

Not wanting to get in the way of these testosterone-pumped beasts, I tiptoed my way past a few slumbering males towards a small king penguin colony. Distracted by photographing this cluster, I was slow to notice a weaner elephant seal wobbling closer and closer to me until it pinned my wellington boot to the ground and started sucking on my knee. I wiggled my foot free from its considerable weight and backed off. I hadn’t been

expecting to wash elephant seal dribble off my trousers at the end of the day, but anything can happen here.

I have an odd collection of inspiring images around my work desk including Edward Wilson’s ‘Blizzard’, a simple pencil sketch of a lone figure battling wind and snow to collect a meteorological reading. Visiting Salisbury Plain felt like I had walked into this scene. The landing was a challenge and a set of flags had been set up to mark our way to the penguin colony. The wind picked up and squalls of snow and sand began to blow around us, almost taking me off my feet. I hunkered down and trudged into the glacial blast. I felt so alive, despite my breath freezing on my eyelashes.

We found grouchy looking adult king penguins coated in snow and a huddle of fluffy brown chicks with their backs to the wind. The clouds lifted and the sun broke through revealing hundreds of thousands of penguins spread as far as the eye could see.

A cacophony of wheezy honking and chitters surrounded us as parents called to chicks and vice versa; how they find each other in all this confusion is unfathomable. The chicks shook off the snow and grew interested in us, the strange and colourful creatures. I sat quietly with my camera poised with its telephoto lens, which proved redundant as curiosity got the better of the

chicks. They approached cautiously, eventually pecking at my boots, nosing through my rucksack and finally breaking the lens glass.

Visiting South Georgia was a pilgrimage of sorts. I had listened to scratchy records of Shackleton’s voice describing his expeditions and read many books about his amazing escape. So when I found myself standing at his graveside in a small cemetery in Grytviken, toasting a tot of whiskey to ‘The Boss’, I was moved. My hankering to return to this magical island has not since diminished. It has captured my heart and blown my mind.

Underwater adventure in Raja Ampat

by Clare HigginsonI woke up with butterflies in my stomach. Today was the day I had waited years to experience. Should I jump out of bed now and peek through the curtains, or take time to enjoy the sense of anticipation? What if it failed to impress?

I jumped out of bed; I just couldn’t wait. I held my breath as I took my first glimpse. My eyes immediately fell upon jungle-covered islands that make up the northern part of Raja Ampat National Park. I smiled. I had finally arrived.

We had cruised overnight to arrive early. It was only 7am, but, after a quick caffeine fix, we were on the tender heading to the shores of one of the islands.

“It’s not an easy climb,” warns Jay, as a daring group of us begin the steady, upward pace towards what promised to be the viewpoint that would win first prize of the trip.

We cling onto spiky limestone as we balance on rocks and push our legs to the top. We reach the peak and I glance across Wayag feeling a little overwhelmed. I had seen images before, but nothing compared. This was me, here, right now. I had to pinch myself. A pure, mindfulness moment to hold onto.

The way back down is just as challenging, but with the thought of breakfast motivating us, we all seem to make light work of it. Before we know it, we are speeding back to

the boat ready to be rewarded with a delicious spread.

As my breakfast settles, I head to the second deck to relax and find myself reflecting on how the boat, Rebel, was hand-made in Sulawesi. Every piece of wood was crafted perfectly to create this five-cabin beauty. The finishing touches are contemporary and it’s clear that every detail has been thoughtfully designed to accommodate the challenges of life at sea. The crew are attentive and multi-talented. The waiter is also a divemaster and the housekeeper doubles as a masseuse. Lisa, our cruise director, is a trained marine biologist – the perfect person to educate us about the corals that we are about to experience on our first underwater adventure.

Lisa explains that 75% of the world’s coral species are found in Raja Ampat National Park and are extremely healthy. Despite bleaching incidents across the world, this area has shown strong resilience and with currents sweeping larvae to other reefs, it is encouraging further growth. With eagerness to see for ourselves, we split into two groups: divers and snorkellers. I join the divers as the two tenders take us out to the reef and after checking the current, we all backroll or slide into the glistening water.

As I sink deeper, my mind starts to wonder what the ocean will show me.

I’ve always felt amazingly comfortable underwater and today is no different. I watch the bubbles sneak out of my breathing regulator as I glide effortlessly through the water. Everywhere I look is an explosion of colour; fish going about their daily reef life tasks flitting between the corals.

I am surrounded by huge clusters of yellow fusiliers, rainbow-coloured parrot fish and spotty triggerfish, huge areas of staghorn coral, green cauliflower coral and orange anemone coral. Black tip sharks and blue spotted rays seemingly play a game of hide and seek. The gentle manta rays were yet to come; today was all about the coral and the liveliness of the reef. The perfect reminder that our planet is resilient and, when given the space and support, can thrive.

An hour later, bubbling with our highlights of our initial submarine journey, we were now speeding over to an island for an afternoon of beach bliss. The water invites me in with its blue hues as I relax and breathe. I see Rebel sitting proudly among the islets. She doesn’t know it yet, but she will be the source of much nostalgia. I asked myself this morning, what if it failed to impress? Well, I hope that answer is easy to figure out and it was only day one.

Think like a puma

by Jarrod Kyte“If you want to see a puma, you have to think and act like a puma.”

My guide, Victor, looked serious for a moment.

“Tomorrow we get up before sunrise... but no guanaco for breakfast.”

I am up before the alarm, excited by the prospect of tracking pumas in the wilds of Torres del Paine. I am also apprehensive at the thought of oversleeping and keeping Victor waiting. A lie-in is hardly puma-like.

We drive out of Eco Camp; the wispy clouds in the sky take on a warm, pink hue as the sun rises above the jagged peaks of the Andes. Victor explains that today we will be searching for puma in Laguna Amarga, a private ranch of 7,000 hectares, access to which is granted only by special permission. We drive for an hour, stopping to scan the horizon for signs of a puma.

“If I look left, you look right. If we work as a team then we improve our chances.”

I scrutinise the desolate pampa, lakeside trails and high plateau dusted with snow. I think of what the outrageous odds must be of finding a puma in such a vast and unfathomable

landscape. I know this region has one of the highest densities of puma in Torres del Paine, but if the animal wanted to remain undetected then surely no amount of binocularbashing would shine a light on its feline form. My momentary bubble of pessimism is quickly pricked by enthusiastic guidance from Victor on what to look for.

“If the guanacos are looking alert then this is a sign pumas are around... and keep an eye out for hovering condors as they may have located a kill.”

With empty skies and just a few indifferent guanacos on the horizon, my mind wandered to yesterday, when I joined researchers in the field collecting data from camera traps at neighbouring estancia, Cerro Guido. The snow fell heavily; the only puma I saw were those on video. Condoreras and Lago Sarmiento are areas of land set aside in perpetuity to provide sanctuary to Patagonia’s big cats.

Nobody seems to know exact figures, but it is estimated that there is a puma for every 10 square kilometres in Torres del Paine. As we step out of the vehicle to continue our search on foot, it isn’t long before we see the proof.

The long, curved spine of a guanaco, so picked clean of meat that it looks almost polished, sits in the middle of a collection of smaller gnarled bones and scraggly fur. Less than 50 metres away, another similar pile of bones and then a far more recently predated carcass. Victor draws my attention to how the puma has attempted to cover the kill with foliage to stop scavengers from finding it.

“We are walking across a puma’s hunting ground. Be alert and follow me,” he says.

We climb a vantage point and look across a narrow valley towards an elevated plateau.

To our left is the blue and glimmering expanse of Lago Sarmiento, overlooked by snowy mountain peaks. On the horizon is the iconic Paine Massif. The sky is cloudless and the air feels crisp and new. I have seen images of the three iconic granite towers of the Cordillera del Paine a thousand times, but the pictures do not prepare me for the wild, elemental beauty.

“Do you see him?”

Victor has his binoculars fixed on a point on the other side of the valley.

“Where?” I exclaim.

“There is a puma sitting on the side of the hill.”

“Where?” I repeat, trying hard to stay cool but behaving anything but.

Victor uses all the normal tools to explain – “if the large rock is 12 o’clock then the puma is sitting at three o’clock”, “stand behind me and follow my gaze” – but it takes at least five minutes before the twitch of an ear betrays his location.

“He is going to the higher ground to stalk that herd of guanaco on the ridge. We need to move quickly.”

Following a steady but challenging trek, we reach the slope on the other side of the valley. We stop at the exact point we had seen the puma. Victor tells me to wait a moment while he scrambles up a steep slope to reach the highest point of the plateau above.

A minute or so later, he returns, an enormous smile on his face. He urges me to follow him to the plateau. We reach the top and there, against the backdrop of Laguna Sarmiento and the snow covered Andes, is a puma no more than 50 metres from us.

Victor begins to remind us of the protocol in a situation like this, but before he can finish, the puma stands, stretches and walks towards us. It is a ‘walk-past’ of extreme confidence. As he saunters less than 10 metres from where we are standing transfixed, he locks both eyes on us, leaving no doubt as to who is the alpha in this wild, mountainous terrain.

Nature’s superstructures

by Paul Bird

‘It’s falling,’ someone shouted. I turn to see a sizable chunk of the glacier breaking and crumbling into the lake below. The huge lumps of ice fall, creating large waves across the lake below.

South of Buenos Aires lies the small town of El Calafate. This southerly point is the gateway to unspoilt scenery at its very best. There are few towns further south in the world, leaving you with a rewarding sense of discovery of a faraway land. The reason why? The Andes – plain and simple.

This geographical wall straddles virtually the entire Chilean-Argentine border. Warm air currents flow east across the Pacific, the humidity dramatically absorbed by the mountain range. Over the years, this snowfall has formed some of the massive glaciers that totally dominate the landscape.

At over three miles wide and boasting heights of over 70 metres, as well as an impressive 170 metres below the waterline, Perito Moreno glacier is really quite a spectacle. It’s larger than the city of Buenos Aires. Photos do not do this area justice; in such vast, mountainous spaces, it is not until you get close that you begin to realise just how impressive they are.

The western base of the glacier is where I equipped myself with crampons ready to walk across a

tiny section of this boundless glacier. From here, it looks like a smooth wall of ice, with the edges meeting the water in a completely vertical face. At the top, you can see jagged peaks and bottomless crevasses with an astonishing shade of deep, sapphire blue.

The sounds of the crampons crunching underfoot is strangely satisfying, whilst the creaks and groans of the slowly advancing glacier were not so. What can only be described as the sound of an army letting off cannons would occasionally echo all around; a stark reminder that this glacier is constantly in motion. You do have to completely trust in the knowledge of the guides and the thickness of the ice.

As we headed towards the edge of the glacier, the trek coming to an end, a well-positioned table came into view. This incongruous table was where I was rewarded by my guide with whiskey served over chunks of glacial ice thousands of years old. Without a doubt, my most memorable place for a whiskey.

Sailing away from the glacier, I look back and see people still trekking. It was the perfect illustration of the scale of the scenery; they looked so small against the backdrop of one of nature’s superstructures.

The heart and soul of Egypt

by Rachael Tallents

When exploring Egypt over 15 years ago, I was mesmerised by the temples and tombs, and enjoyed the slow pace of cruising down the Nile from Luxor to Aswan. So, when the opportunity to return emerged, I jumped at the chance.

Luxor was just as mind-blowing as I remembered. Our Egyptologist Ahmed was the most captivating guide, not only for his knowledge of traditions, customs and archaeology of ancient Egypt, but also for his open mind and passion for modern day Egypt too. Ahmed was a kind-hearted and gentle guide, and after discovering his PhD was centred around the significance of ‘the heart’ in ancient Egypt, I wasn’t surprised. His love and passion for his country and its people shone through.

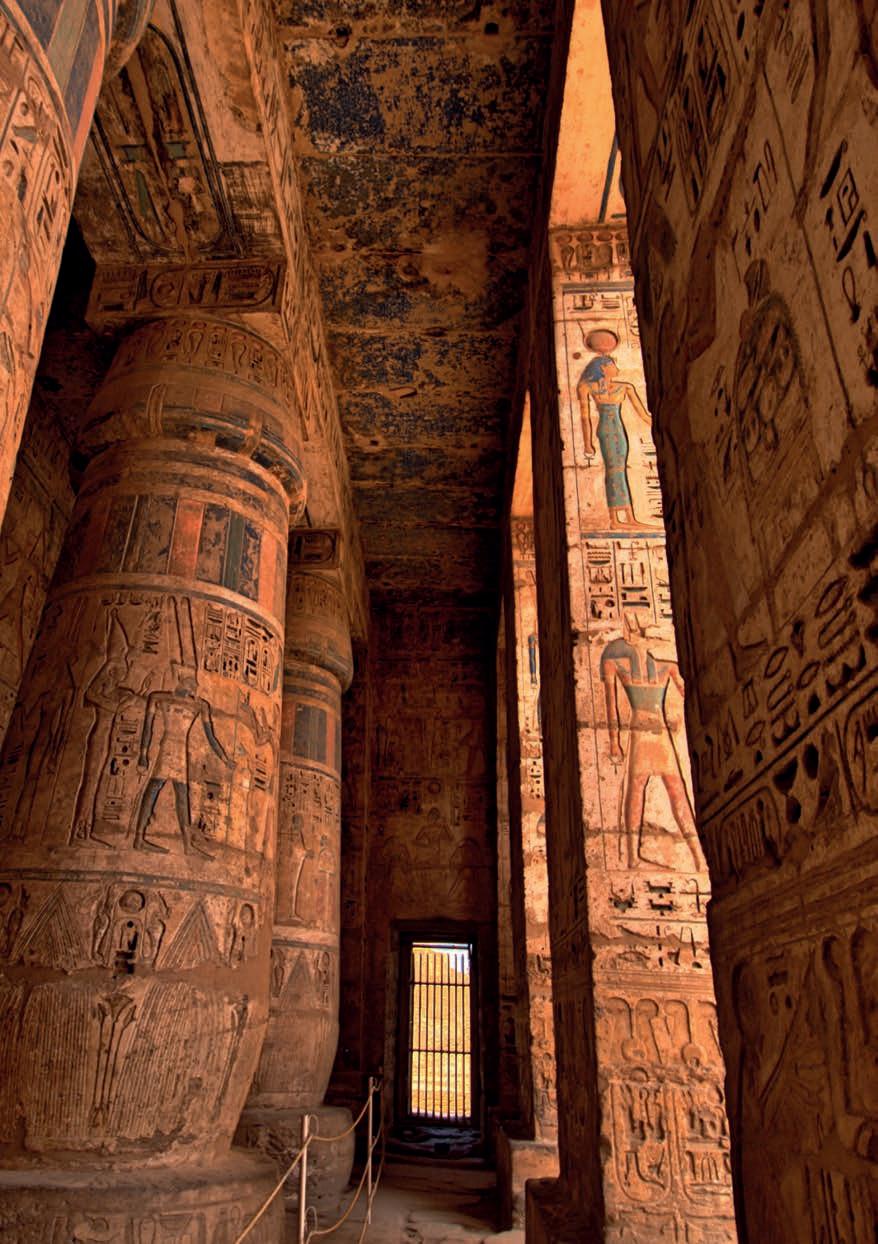

I stood captivated in the main hall of Karnak temple, listening to Ahmed speak of ancient rituals and traditions, of how nature and astronomy guided the lives and afterlife of this intriguing civilisation. Ahmed described how magical it is to be at Karnak temple on the winter solstice. The sun’s rays gleam through the hypostyle hall as it rises, celebrating the return of the sun god Amun-Ra, the beginning of the germination season and to commemorate the winter solstice.

To honour the living Pharaohs and the Gods, religious temples were constructed on the east bank of the

River Nile. While Luxor and Karnak temples are vast, it was when visiting the mortuary tombs of the west bank, where the sun sets, that made me realise the significance of the afterlife to the ancient Egyptians. We glimpsed into the mysterious underworld of this culture, descending into the tombs of the Pharaohs, intricate hieroglyphics and carvings filling the walls. Ahmed described the rituals of the preparation for the afterlife and the treasures stored with the bodies. Having our own Egyptologist was a special experience and one I would recommend to anyone.

Our memorable journey along the Nile concluded in the beautiful riverside setting of Aswan and a visit to Philae temple. Dedicated to the goddess Isis and the tragic love story of her husband Osiris’ death, Philae temple is thought to be the place where Isis found Osirirs’ heart. In Egyptian mythology, the goddess of healing and magic resurrected Osiris and gave birth to their son, Horus. The mythology and beauty of these sacred monuments undeniably connects to your heart.

I do not have enough cows

by Justin Wateridge“Have you come to see a cow?”

The immigration official greeted me on arriving at Juba International Airport.

I am in South Sudan, a county of 644,000 square kilometres (roughly two and a half times the size of the UK) and 10 million people. There are many more cows.

Indeed it was an excellent question as a few hours later I arrived at a Mundari cattle camp. The Mundari are a semi-nomadic Nilotic peoples whose prize possession is their cattle, the Ankole-Watusi.

Conical mounds of dung smoked away. The Mundari burn the cow dung to give off heat to keep the cows warm at night and for the smoke to keep away flies.

Young boys meticulously sweep the area, others attend to the mounds ensuring there is enough dung to create both warmth and smoke. Their bodies are covered in grey ash as protection from both sun and insects.

The Mundari women are on the periphery, preparing food and looking after the very young children.

A few men are seated on rickety stick platforms. The greeting, “Adida”, is exchanged. Huge hands engulf mine in welcome. Questions are exchanged.

“Why do you only have three children?”

My reply of “Because I do not have enough cows,” creates a laugh, although I am unsure whether it is with me or at me, in terms of my diminished status for having too few cows.

As the power of the sun fades, the cows are brought into camp and we walk around largely ignored. The Mundari are more interested in their livelihoods as they tether their cows with short ropes to stakes driven into the ground.

The camp consists of some 70 men, women and children and at least 10 times that number of cattle, a hundred or so goats, a handful of chickens and a litter of puppies. With each cow or bull being worth up to $500, the herd is quite some display of status.

Hence the cows are rarely killed for their meat. Instead, they are a walking larder providing both milk and yoghurt. It is not just the Mundari that benefit from the milk of their cattle. A young boy helps a kid – baby goat as

opposed to one of his friends – suckle from the teat of a cow.

For the Mundari, their cattle are a resource maintaining a way of life. The Mundari cows act as a pharmacy – cow urine is used as an antiseptic. The cows give aesthetic choice – the ammonia in the cow’s urine is used by the Mundari men to colour their hair orange. Cattle are used as a dowry –the taller the woman the greater the dowry, the more cows. They act as friends, many having names.

The guttural bellow of the cows, goats bleating, bells tinkling; dust and smoke fill the air as the Mundari and their cattle bed down for the night.

Dawn rises. Young boys are diligently and silently trying to clear up, sweeping the dung into piles with their hands to carry it to the edge of the camp where it is dried before it can be burned. It is hard work and some boys are still asleep by their cows, literally.

Cabals of men stand, chatting and chewing twigs of the arak tree, an evergreen commonly known as the ‘toothbrush tree’. They begin to work, taking their precious cattle out to graze. They lovingly rub the ash from the dung fires into their cattle’s skin and adorn them with ornamental tassels to keep off the flies.

Horns are blown; the cattle bellow in a guttural response. The expectation of

imminent movement is palpable. Young boys scamper around collecting final jugs of milk before the cows depart.

The boys tug and pull the cows, urging them into motion. Others push from behind. There is obstinate reluctance from the cattle but they are coerced into action. The herd moves slowly out of camp, leaving behind many of the young.

Uninhibited by the scrutiny of their elders, the shyness of the young evaporates and they show a curiosity in me, not least the hair on my arms. Many have phones – one even a small solar panel to charge his phone – but not phones with cameras. They are intrigued by images of themselves –they love taking selfies with my phone – and so too of the cattle, mentioning many by name.

One man is intrigued by the tent we slept in and its cost. He is told that it is roughly the same as a cow. I ask whether he would swap a cow for the tent. He guffaws in outrage.

Moonface is absent

by Illona CrossGrowing up with German parents I spent my younger years immersed in the Brothers Grimm, adoring fairy tales and their shift from light to dark to light and back again; but being in apartheid South Africa meant that the breadth of my reading was often limited by the politics of the day.

Instead, I learnt and loved African folklore, taking ancient stories and beliefs from local peoples and intertwining them with my own. My love of a good tale well told never waned.

It’s no surprise then that, after moving to England and having started a family of my own, a secret treat was always listening in to my husband reading, at bedtime, to our boys. How they loved Treasure Island, begged for another chapter from Gobbolino the Witch’s Cat and sat, goggle eyed, through Where the Wild Things Are.

The real favourite was Enid Blyton’s ‘The Faraway Tree’, that ever-changing, otherworldly home to fascinating fauna and wondrous arboreal dwellers; that focus of adventure, that singular, unique, freak in nature; that tree like no other, that marvel, never to be completely understood, never failing or ceasing to amaze.

And now, in the teeming rainforests of Madagascar, I’m standing in front of it, realising that it’s real.

Everything here starts at extraordinary. The baobabs astound with their height and girth, the forests, brim-full with wildlife and colour, where it’s nigh on impossible to take a step without seeing the freshly astounding; the air, whether it be night or day, jam-packed with unfamiliar, startling sounds, the way the tightly packed trees cascade onto perfect beaches meeting turquoise sea rich with vibrant, busy and nigh-perfect reefs. Here is a place where breath is easily stolen.

But this is something different again. The tree in front of me, I am told by my excellent guide, has no name in science. It’s called ‘The Unknown Tree’; and it’s not that it’s unique to Madagascar that makes it fascinating. It’s not that it’s unique to this forest. It’s that it’s unique in any forest. It has no twin. There is only one. Anywhere.

No one knows why. The solitary French scientist who studies it, chosen by local elders, the only person allowed to touch it, can’t explain it. It doesn’t germinate. No one knows how it came to be; and no

one knows why, every time this tree is studied, it appears to be a ‘different tree’, with different leaves, bearing different fruits. Just like in the book.

It’s no wonder that the locals revere it, regularly asking from it, praying for future bounty.

So, no Moonface, no Silky, no Slippery Slip; no Dame Washalot, no Angry Pixie. But who needs them? In some places, the magic of fairy tales is surpassed by that of reality. I am in an ‘enchanted wood’, where sorcery is everywhere, where impossible is every day and where the opaque alchemy of our natural world conjures nothing but treasure.

I will go home richer with fine stories to tell.

Travel is a personal journey as much as a geographical one and it should take shape exactly as you see fit. We believe in providing you with a blank canvas to create your holiday, sharing our expertise when and where it matters most, and then making it happen for you. We exist in a place where inspirations meet, where yours become ours. Let us help you create your next Beautiful Adventure.

Share your journey with us

#mysteppes

UK: +44 1280 460 084

USA: 1 800 571 2985

inspireme@steppestravel.com www.steppestravel.com

When you’ve finished reading me, please pass me on to a friend or recycle me.