ATRIUM

In Conversation

In Conversation

It used to be the rule that dinner party conversation must stay clear of certain topics – politics, religion and

sex. Atrium editorials should probably do the same, but it is difficult at the moment.

St Paul’s, and more particularly fee-paying parents and grandparents, are facing up to VAT being charged on fees from January 2025. This is portrayed by our new government as removing a subsidy to independent school customers. Canvassers at the General Election say the policy was well-received on the doorstep. Neither of these is a surprise.

Further into the magazine, David Abulafia (1963-67) writes, “Far more productive for society than taxing school fees would be vocal support for the efforts alumni and benefactors have been making to ensure that the great schools of England, among which St Paul’s has always been counted as one of the most prominent, can offer as many bursaries (including full ones) as possible and move towards needs-blind admission”. Robert Stanier (1988-93) contributes a letter on the same theme.

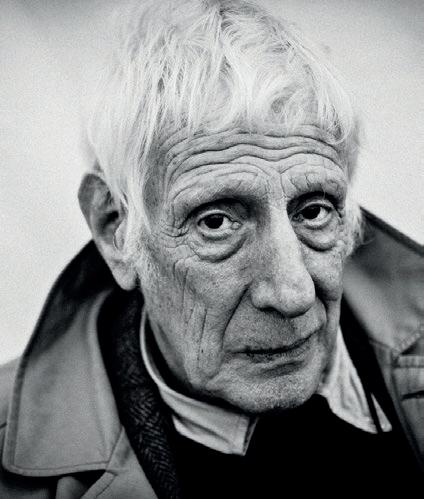

Sir Anthony Jay (1941-48) is most well-known as one of the writers of Yes Minister. Historian and Emeritus Fellow, Ronald Hyam in the Magdalene College Magazine 2016-17 wrote in his obituary of the OP and honorary Magdalene Fellow, “Long before he became famous, he made a film about Cambridge, seeking to widen its appeal to intending candidates and to advise freshers on what to expect. Naturally he sought the co-operation of the College. His 50-minute television documentary, Going Up: a personal look at being a new boy in an old university (31 August 1976) centred upon Magdalene and in particular three of our undergraduates from different types of school (boarding/ independent day/comprehensive)….

Jay’s entertaining narration concluded with an observation that if viewers thought Cambridge was too much about privilege, ‘I’ve always been for the extension of privilege rather than the abolition of it myself’”.

Of course, David, Robert and Tony are right. In July’s OPC monthly newsletter, I proposed that a ‘Bursary Boy’ network be set up. I wrote, “I received a bursary in the 1970s and believe that the luck of being at St Paul’s has opened up opportunities (not always taken) in later life for me…Those of us who benefited from assistance with fees in the past, and that includes the Foundation and Music scholars when the awards had significant financial benefits, can be the foot soldiers in campaigns to help this and future generations of bursary pupils at School. I envisage the network not only having a focus on fund raising for bursaries and partnerships but also as a source of information and advice that can be mined by current and future pupils.”

Whatever tax is in place, we should look to provide as many bursaries as possible and extend privilege (perhaps, ‘opportunity’) to as many pupils as we can. If you want to join, sign up at community@stpaulsschool.org.uk

One of my favourite moments as we pull together Atrium is counting how many contributors we have. This magazine has 21 including our brilliant Archivist, Kelly Strickland and former staff member and honorary OP, John Venning. The oldest contributor arrived at St Paul’s just after the Second World War and the youngest left after the war in Ukraine had started. Articles this

time profile Edward Behr (1940-44) another Pauline who went on to Magdalene, Jonathan Miller (194753) and Leonard Woolf (1894-99). Others describe writing a PhD later in life, setting up a school in Uganda, writing a first novel, and being gay at School.

Finally, it is my great pleasure to send congratulations on behalf of all OPs to David Ambler (2011-16) and Freddie Davidson (2011-16) on their Olympic bronze medals. For once, choosing our front cover image was simple.

Jeremy Withers Green (1975-80) OPC President

The Editorial board thanks all contributors, information providers and proof readers and particularly Kaylee Meerton and Kelly Strickland.

Kaylee Meerton joined St Paul’s as the Marketing and Communications Manager in 2023, taking on the role of managing the School’s internal and external communications, as well as leading the marketing of the Old Pauline Club. Originally hailing from Australia, Kaylee relocated to London in 2022 with a short contract at King’s College London before joining St Paul’s. Prior to that, she graduated from Curtin University with a degree in Journalism and International Relations, picking up work experience in China and the United States. Her career started in the Australian regional journalism landscape, with roles as an editor and reporter for Fairfax Media, Australian Community Media and Student Edge.

Kelly Strickland joined St Paul’s School as the Archivist in 2022. She is the Archivist for both the School and the Old Pauline Club. Kelly is originally from Houston, Texas, and gained her degree in International Relations from Occidental College in California. Following her degree Kelly spent a year in Russia as an English teacher. After that Kelly started working as a financial journalist. She decided to retrain and gained a Masters in Archiving from Simmons University in Boston. She relocated to the UK in 2021 and after gaining experience working at Westminster Cathedral was delighted to take over the Archivist job at St Paul’s.

Tyler John has been the Head of Diversity, Equality and Inclusion at St Paul’s since 2022, after working in both Higher Education and corporate settings. He started a PGCE in PSHE with the University of Buckingham in September 2024.

John Venning was Head of English at St Paul’s from 1989-2014. He read English Literature at Cambridge and taught undergraduates there for a further three years while failing to complete a PhD. He then taught at Manchester Grammar School, Downside School and Malvern College. Since retirement he has done some part-time teaching, further researching and writing, and cultivates his garden in Cornwall.

Michael Simmons (1946-52) read Classics and Law at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He qualified as a solicitor and after two years as an officer in the RAF practised Law in the City and Central London for fifty years. Since retiring, he has pursued a new career as a writer. Michael is in touch with a sadly diminishing number of members of the Upper VIII of 1952.

Malcolm Sturgess (1947-52) spent half his first decade dodging bombs and doodlebugs and being bombed out four times. As a consequence of this peripatetic existence he went to nine different schools, culminating in 1947 with St Paul’s, re-establishing itself in Hammersmith. After School, Malcolm had no idea what he wanted to do as a career. He was a surveyor briefly. Then he embarked on the career he felt he had been born for. Twentynine years later, he was invalided out of teaching. Malcolm eventually began a third career running the recorded music department in an Ottakar’s bookshop. He was advised he could afford to retire in 1994 and has since spent thirty years happily involved in music, travel, steam trains and gardening.

Robin Dodd (1961-65) is a second-generation Pauline oarsman. Son of Ralph Dodd DFC (1935-38), who died in 2012, and who spoke highly of the education he received – sufficient to be accepted for pilot training, despite leaving School a year early. Ralph flew Beauforts and Beaufighters, was shot down in 1943, and spent the remainder of the war in Stalag Luft III. Robin read Rural Estate Management, at the Royal Agricultural College, Cirencester, whipping-in to the College Beagles and hunting, followed by a career in commercial property, becoming a partner of a major West End firm. Later he was a pianist aboard ships and assistant expedition leader to the Arctic, Antarctica and the Black Sea.

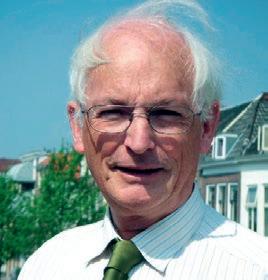

David Abulafia CBE (1963-67) is Emeritus Professor of Mediterranean History at the University of Cambridge, a Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, and a former Chairman of the Cambridge History Faculty. His books include Frederick II, The Discovery of Mankind, The Great Sea and The Boundless Sea which was the winner of the Wolfson History prize in 2020. He is a Fellow of the British Academy, a Member of the Academia Europaea, a Commendatore of the Italian Republic and Visiting Professor at the College of Europe and at the University of Gibraltar. He has been the Apposer at Apposition and is a Vice President of the OPC.

Nick Birbeck (1967-72) graduated from SOAS in 1981 after a prolonged stay in Australia. He worked in Yogyakarta, Indonesia from 1983 to 1995 where he set up an English school and also taught at Gadjah Mada University, training postgraduate students for overseas study. In 1995 he was employed at the University of Exeter as an Education adviser, supporting academics in all disciplines with their teaching, with an emphasis on the use of IT and, latterly, AI. He retired in 2016 but continues to teach and support academics at Exeter. He is fluent in Indonesian and Malay and once presented an English radio programme for Indonesian learners. He was a keen cricket and tennis player until a hip required replacing. He now enjoys gardening.

David Herman (1973-75) studied History and English at Cambridge and English and American Literature at Columbia University. He produced arts, history and talk programmes for BBC2, Radio 4 and Channel 4 (when it was good) for nearly 20 years and since then has written about literature, and Jewish culture and history.

Jamie Priestley (1975-80) after St Paul’s read French at Durham. He spent the first half of his career on external marketing campaigns for well-known brands like Shell and Ford, but the inside of organisations had always interested him and he began to specialise in corporate culture: how ideas take hold at work, or do not. He works with leadership teams to change the culture of their organisation. He hopes to get a version of his PhD thesis into good bookshops once he translates it into plain English.

Ben Parkinson (1978-82) at School his main interest was music. He also played in an unbeaten 4th XV. Ben worked as a cruise ship pianist in the Caribbean and he learnt of the income differential between those living overseas and in Britain. This stayed with him in his career when in 2002 he became CEO for a social enterprise, Jericho. In 2007 he left to travel to Nigeria and while there devised a project to train teenage youth to become changemakers. Now known as the Butterfly Project, this project has seven groups, based all over Uganda. In 2020 during the pandemic, Ben was able to build a unique secondary school for developing changemakers in Northern Uganda, with the support of Norton York. Ben was the 2023 winner of the Gandhi Foundation International Peace Award for his work in Northern Uganda.

Norton York (1978-82) met Ben Parkinson at Colet Court and they became friends playing trombone together throughout their time there and at St Paul’s in the School orchestras. Later Norton helped Ben establish his work in Uganda. When Ben was ready to found the Chrysalis School, Norton saw a wonderful opportunity to help fund the construction as well as encouraging others to contribute. Norton’s professional experience as a school proprietor and university professor supported and developed the social entrepreneurial approach and his career in pop music education though RSL Awards, widely known as Rockschool, helped inspire the school’s approach to music.

Jonathan Foreman (1979-83) read History at Cambridge University, then Law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. He has been a war correspondent, a film critic, a leader writer, and has

reported from Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. He is the author of two books, one on Foreign Aid and its challenges (Aiding and Abetting, Civitas 2015), and the other an anthology of American history (The Pocket Book of Patriotism, Sterling, 2005). He has written for many publications on both sides of the Atlantic and in Asia.

Theo Hobson (1985-90) studied English Literature at York University, then theology at Cambridge. He has written some books about religion including God Created Humanism: the Christian Basis of Secular Values and much journalism, including for the Spectator. He is currently a part-time teacher, part-time writer, and part-time artist.

James Grant (1990-95) sits on the Old Pauline Club’s Executive Committee as Sports Director, as well as holding the posts of Chairman of the Old Pauline Cricket Club and Honorary Secretary of the Old Pauline Golfing Society. After a career in event organising and charity fundraising, he now works at St Paul’s as Associate Director, St Paul's Community and still feels nervous entering the staff room.

Lorie Church (1992-97): when he is away from the workplace, Lorie encourages people to put letters in little squares. He has had puzzles published in various titles internationally. As well as contributing to the Listener series, Mind Sports Olympiad and Times daily, he sets Atrium’ s crossword.

Neil Wates (1999-2004) worked in the property sector for 15 years before training as a Psychodynamic Therapist & Counsellor. He is a trustee of a UK based charitable trust and an NGO committed to the alleviation of social violence in East Africa. He also founded Friendship Adventure; a craft brewery based in Brixton. Neil is on the OPC Executive Committee.

Michael Hanson (2002-07) is the CEO and Founder of Growth Genie, a consultancy that empowers sales teams to have better conversations through training, coaching and building sales playbooks and processes. Its clients range from fortune 500 companies like JLL to fast growing fintechs like Dext.

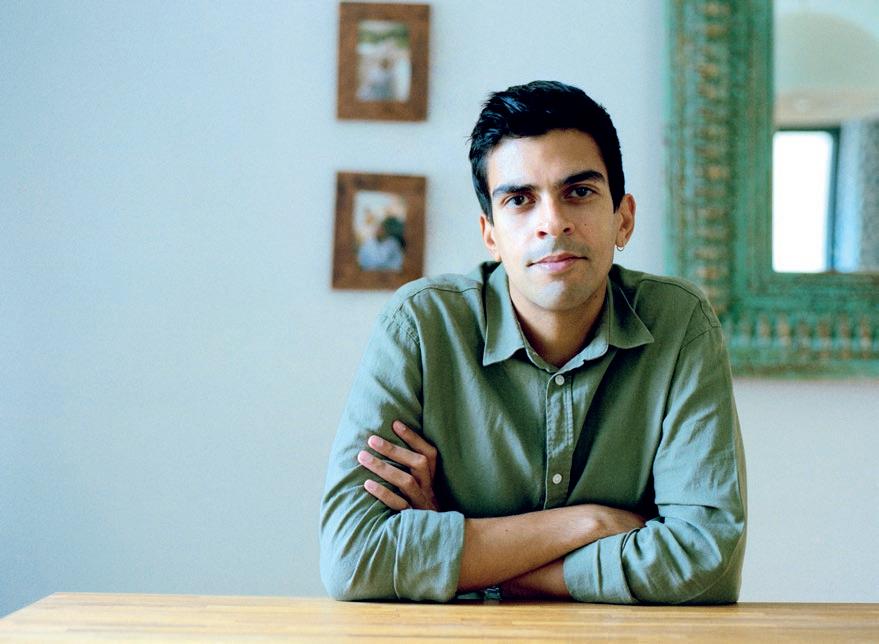

Ammar Kalia (2007-12) is a writer, musician and journalist living in London. Since 2019, he has been the Guardian’s Global Music Critic and he has written for publications including The Observer, BBC, Economist and Downbeat. In 2020 he published a collection of poetry and an accompanying album, Kintsugi: Jazz Poems for Musicians Alive And Dead. He has an essay on music and identity in the 2022 collection Haramacy He was shortlisted for the Unbound Firsts Prize in 2022. His debut novel, A PERSON IS A PRAYER, tells the story of a family’s migration from Kenya to England over three separate days across six decades and was published by Oldcastle Books in May 2024.

Richard Griffiths (2016-2021) is entering his final year as a History undergraduate at University College, Durham. A student journalist, he has been Head of News for PalTV and won the Gold Award for News and Current Affairs at the National Student Television Awards 2024. At St Paul’s he was a keen dramatist and appeared in the film The Lady in The Van and Netflix’s The Crown. He took a gap year in 2021/22, when he worked as an aide in the House of Commons, and in 2024 he was recruited as a researcher for The Times during the General Election.

Omar Burhanuddin (2017-22) currently studies History at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. He is passionately interested in public service, having worked in an asylum relief clinic in New York City and as an English Teacher trainee in Frankfurt. A keen writer, Omar sits on the editorial team of Varsity, the Cambridge University student newspaper. He aspires towards a career in journalism.

Atrium’s Editorial Board: Omar Burhanuddin, Jonathan Foreman, David Herman, Theo Hobson, Neil Wates and Jeremy Withers Green.

More bursaries please

Dear Atrium,

It was good to read about a focus on bursaries in Shaping Our Future: Next Steps. Equally, it is worth challenging the story.

What has been excellent at St Paul's overall in the last decade has been the revitalisation of emphasis on bursaries. As recently as ten years ago, relatively few pupils received means-tested bursaries: between 2013 and 2016 only between 49 and 62 pupils were receiving bursaries, at a value of between £750,000 and £1 million.

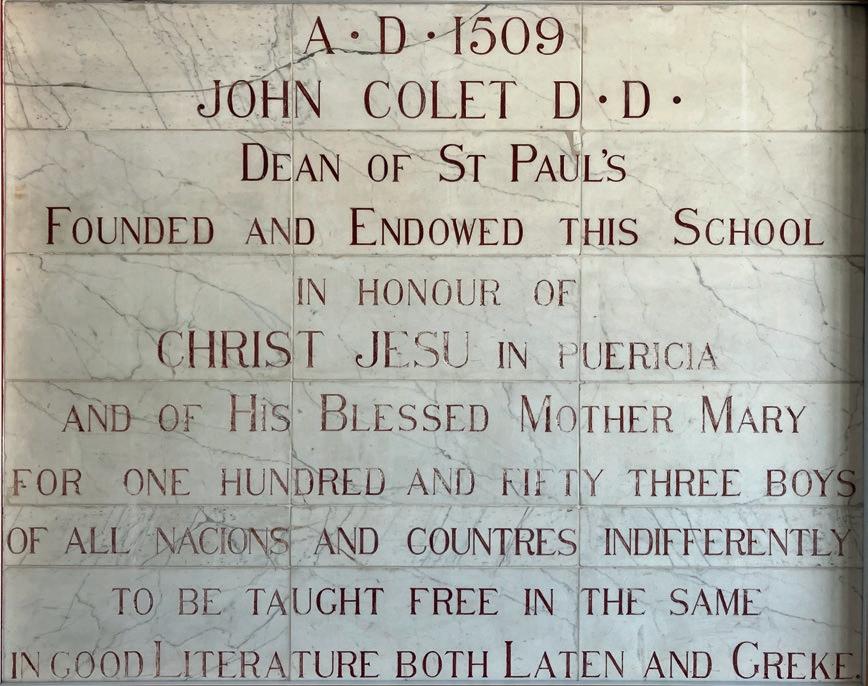

In the campaign launched in 2018, the goal was to increase this so that 153 boys would be receiving bursaries each year. As part of that vision, the number of children receiving bursaries increased markedly every year from 2016 to 2022, at which point 148 boys were receiving bursaries totalling £3.3 million. That represented 10% of the student body at the time, 1,480 pupils.

However, this declined to 143 pupils in 2023 and from the information given about the current campaign, it seems to have further declined this year so that only 132 pupils are currently receiving bursaries. It is worth noting that that is still double what was the case in 2015.

However, the ‘goal’ has declined in this year’s campaign from the previous vision, albeit only slightly: from 153 down to 151. That is perhaps a bit pedantic on my part. More to the point however, the 10% figure given as an aspiration in the current vision was actually achieved just two years ago: since then, it has been in decline, down to 8.7% this year. So, to say ‘continue to grow’ is not strictly accurate.

It is worth remembering that there have been visions before. In 2006, High Master Martin Stephen launched a plan to achieve needs-blind admission at St Paul’s by 2031, which is now only seven years away. It was reported in newspapers at the time that he realised that it would not be achievable straight away, and so “in the nearer term the plan at St Paul’s is to bring the number of places given to children on bursaries up to 20% of the total”. Of course, the “nearer term” never happened. It is good to encourage support for bursary provision, but it is important to note it has been rather a mixed picture lately.

Kind regards, Robert Stanier (1988-93)

A haven for completing unfinished homework and for gossip Dear Atrium,

I want to say how much I have been enjoying the latest copy of Atrium. You have managed to cover so many aspects of Pauline experience that it has taken me several weeks to reach the point when I simply had to write to you. I keep returning to my copy.

One point you might like to note in the current arguments about antisemitism: I remember (from ages ago) a classmate of mine was asked bluntly in my presence whether he had ever encountered it at St Paul’s. Looking straight at me he replied, “No. The first time I felt that was at Cambridge”. We shared a smile. We had both been in the small lecture theatre (in the Hammersmith building) for years together during the prayer session in the Main Hall. Himself as a Jew, myself as a Roman Catholic. It was a haven for completing unfinished homework and for gossip.

Best wishes, Mark Lovell (1947-53)

Not All Happy Days

Dear Atrium,

In the Spring/Summer 2024 edition of Atrium, Richard Dale remembers his ‘generally happy’ days at Colet Court. There is a poignant introduction to the article that describes an assault by a teacher that Richard was able to manipulate to his advantage in achieving a ‘boost to his street cred’.

I do not believe that Richard would include this incident in his list of happy times at School, however, I would argue that there is an underlying implication that physical violence towards children in schools in the bad old days did, to some extent, make a man or woman of you.

Beating in schools has been a subject for much entertainment and frivolity in popular culture. Dickens wrote about it and Tom Brown’s School Days was a best seller. The Bash Street Kids are no longer threatened with the cane or slipper by the teacher, but this was not the case when I was allowed to buy the occasional copy of The Beano, the final panel invariably ending with a ‘Thwack!’, ‘Swipe!’ or ‘Sting!’. Jimmy Edwards in Whacko attracted a large audience. Perversely, there is also an online game called Whack Your Teacher where children can take revenge on a virtual teacher. Perhaps one wonders why they should want to?

Like Richard, I was also in Miss Sawdor’s 1B class at Colet Court. I remember being afforded nothing but kindness by her, perhaps establishing expectations of similar treatment by teachers, all male I should add, in the following years. These hopes were short-lived. However, I would stress that although teachers frequently used indiscriminate punishments and indulged in humiliation and bullying, most were not violent. It was the few that were who one perhaps remembers most vividly.

The teacher who assaulted Richard in his article was infamous at Colet Court. I was punched on the side of the head once by this man for failing to do my homework. I witnessed several similar attacks on others, one involving a cricket bat. One boy, considerably taller than this short, stocky scoundrel, gave him some lip in the playground and was practically knocked unconscious by a right hook. I remember telling him to tell his parents. I do not know of anyone who ever did.

Mucking around in class could be a risky venture, even with relatively mild-mannered teachers. One could push one’s luck, especially if egged on by peers, resulting in an exhaustion of patience and a physical attack that could be dangerous if uncontrolled. I do not remember it being good for one’s street cred. The well-behaved classmates thought that one had it coming. Those that had encouraged the boy to horse around could take some satisfaction at anticipating the result – a childish schadenfreude. There could be little sympathy for the victim, perhaps more for the teacher.

I cannot say that I was always very scared at Colet Court. Clearly one could avoid trouble by being studious, compliant and well behaved. However, depending on

who was teaching or watching over you in the playground, one was sometimes nervous. The teachers would, I suspect, have endorsed the Freudian view that a bit of fear is needed to learn stuff. I can still remember poetry I had to recite in class, engrained in my brain for fear of a detention, or maybe something worse. Like Richard, I was ‘generally happy’, but at times I certainly was not.

A more formal and sanctioned use of violence was at the discretion of the headmaster and we were all scared of him. I was beaten for having an untidy desk. I was eight. I was also reported by a monitor for using an expletive in the playground and had to report to his office. I was asked if I knew the meaning of the word (I am not sure I did) and quizzed repeatedly. I was then told to go off to lunch while he decided whether he was going to beat me. He did not. I cannot remember what my final punishment was.

There is no doubt in my mind that the headmaster was aware of the violent tendencies of some teachers and was complicit in maintaining this culture. On reflection it beggars belief that no one ever stepped up and complained.

The sexual abuse that occurred at Colet Court and St Paul’s has been thoroughly investigated. I was not a victim, although I did witness a number of incidents that I reported to the inquiry that was conducted many years later. This abuse was utterly appalling. However, it was largely covert and I believe that the majority of children were not aware of it at the time. Physical violence, on the other hand, was overt. I made this point in my testimony. I believe that in many ways the physical punishments on children at Colet Court by a small number of individuals was equally insidious. I suspect this was beyond the terms of reference.

I have talked about these issues with a few school friends. Often there is an acknowledgement that these incidents occurred but it was the way things were at the time – water under the bridge and, anyway, we all came out OK. One can take some solace in knowing that those teachers who lashed out at children would now be behind bars. Violence of any kind towards children in schools is of course unacceptable today, even though there are some who would like to see a return to a more disciplined regime. But did we come out OK? The question is probably unanswerable. What I can say is that I remember waking up in the morning on some occasions and feeling frightened about going to a place I should have felt safe in. I would be surprised if that had had no effect on my psyche and on the many thousands of children who were victims of teacher assault. Perhaps I can understand why some people might want to play ‘Whack Your Teacher’. Past violence towards schoolchildren by teachers may not rate highly in the ‘pillars of shame’ poll alongside slavery, colonialism, antisemitism, abuse in the Church and all the rest. However, it deserves to be there and to be acknowledged. It was not some rite of passage to be looked back on with a comic book nostalgia.

Yours sincerely, Nick Birbeck (1967-72)

Pauline Polo

Dear Atrium,

I do not recall the game of polo being mentioned in Atrium but I have come across some Pauline related material on the subject. The prestigious Inter Regimental Polo Tournament of India that was dominated by famous cavalry regiments of the Indian and the British Army when stationed in India. For example, the 14th Dragoons, formed in 1715 by an Old Pauline, Brigadier General James Dormer (c. 1700), did tours of India in the 1st Sikh War 1848-49, Central India 1858-59 and 1882 -86, after which it was retitled 14th Hussars.

In 1897 an infantry regiment, 2nd Durham Light Infantry, had the effrontery to win the Inter Regimental Polo Tournament. The first time it had been wrested from the cavalry. The regiment had a brilliant polo team which included an Old Pauline, Lieutenant William John Ainsworth (1885-90) (later Lt Colonel) which had suffered only one defeat in five years. At the tournament it beat the 4th Hussars whose team included a young Winston Spencer Churchill, the 16th Lancers, 11th Hussars and the 5th Dragoon Guards in the final 6 – 1.

From the 1890s many Old Paulines served in the Indian Army including Ainsworth’s brother Captain Harry Lawrence Ainsworth (1894-99) of the 10th Gurkha Rifles, who was also an accomplished sportsman in polo, hockey and football. In 1905, Lieutenant John Clementi (1889-95), serving in the elite Queen Victoria’s Own Guides (Frontier Force), won the Cavalry Reconnaissance Cup of India. He later became Colonel Commandant of the 10th Mahratta Light Infantry.

The Wathen Hall at School is named after a member of a family of Old Paulines with Indian connections and, in this respect, Lieutenant Roger Louis Gerrard Wathen (1923-28) of the Royal Norfolk Regiment was killed in a polo accident at Jhansi, India in 1935. At the resurrected Feast Service at St Paul’s Cathedral in February, I noted on the service sheet the name of Simon Wathen as a Governor of St Paul’s Girls’ School, surely a relative, though not a Pauline.

Best regards,

John Dunkin (1964-69)

[Editorial Board: Simon has confirmed he is a relative.]

The Vivians Dear Atrium,

An OP friend lent me his alumni magazine and I was interested to read about my grandfather, Col VPT Vivian (1900-05), in the Spring/Summer 2024 Atrium (page 31).

He was, of course, a Pauline, as was his eldest son, my father JMC Vivian (1931-36, High House). Because of the war, my grandparents sent their younger son (DV Vivian) to King’s School Bruton. My father’s housemaster Rupert Martin (1927-37) had by then become headmaster there.

I followed Uncle David to KSB in 1966.

I recently had to clear out some old family papers and found amongst them Valentine Vivian’s memoirs. I gave a copy to MI6 (SIS) who seemed pleased to have them.

Yours sincerely, Simon Vivian

Diversity in Action

Dear Atrium,

In nearly adjacent articles in the Spring issue of Atrium, F W Walker is described as a ‘lunatic’ running his own asylum and responsible for a classics department of fascist tendencies and ‘great’, running a national academic powerhouse, leading the country in Oxbridge scholarships. It is good to see diversity in action.

John Venning (English Department 1989-2014)

It was a great pleasure to receive an invitation to the Apposition Dinner for the ‘Lost Years’ of Covid, held at Mercers’ Hall this June – also a bit of a surprise, as I had already attended one a couple of years ago, as a reward for being the Apposer during lockdown, via Zoom, in Mark Bailey’s last year as High Master. But I gratefully accepted the new invitation anyway. And there Mark was in the line receiving guests, one of the great High Masters of a great School. The dinner was a magnificent occasion, with both Paulines and SPGS Alumnae from the Covid years present, elegant speeches, lively conversation, and plenty of toasts in vintage port. It was appropriate that pandemics were on my mind that evening – not just Covid but something far worse, as I shall explain. I have had the pleasure of knowing Mark since he was a candidate for a four-year post-doctoral Research Fellowship at my college in Cambridge, and I was the so-called expert interviewer. I describe myself as the ‘so-called expert’ because his command of the intricacies of the late medieval English economy, and his ability to bring to life the experience of those who lived at that time, when bubonic plague stalked the country, is very impressive. Fortunately, it was impressive enough to win the support of the committee, which included colleagues from the widest range of academic disciplines; he was duly elected to the Fellowship. Mark made a name for himself at that time for his discovery about the importance of rabbits in the medieval economy, about which he expatiated on television; but his research has always been much broader and his most recent book, After the Black Death, explains the powerful economic and social effects of the loss of perhaps half the English population in the middle of the fourteenth century, followed by further assaults of plague that prevented demographic recovery for a long while. That book is based on

the prestigious Ford Lectures in English History that he gave at Oxford a few years ago to a highly appreciative audience.

Although he was the first High Master to bear the title ‘Professor’, as part-time Professor of Late Medieval History at the University of East Anglia, Mark was by no means the only scholar-cum-High Master. One could begin with William Lily in the earliest days of the School; with the support of King Henry VIII and Erasmus his Latin grammar became the standard textbook in many English schools for hundreds of years. Much more recent scholar High Masters included the eminent manuscript expert and medieval art historian Walter Oakeshott, who later became Rector of Lincoln College, Oxford. Oakeshott’s book sales were unquestionably overtaken by Dr Hillard, whose daughter lived almost next door to me when I was a Pauline. His Latin Prose Composition may not have been most people’s favourite schoolbook, but in the now distant days when Latin was the staple of public-school education, it was a desideratum. It was not just High Masters who wrote books. I have the impression that quite a few Classics Masters at the School also produced textbooks. In VIx we used a collection of extracts from the wonderful pioneer historian Herodotus put together by Pat Cotter, the Head of Classics. And then there was the output of Tom Howarth, whose book on King Louis-Philippe was published, I think, before he became High Master, but could take credit in Cambridge Between the Wars for surreptitiously revealing that Anthony Blunt was a Soviet spy. He did not get on with the Head of History, Dr P N Brooks, but Brooks produced a learned monograph entitled Thomas Cranmer’s Doctrine of the Eucharist while teaching at the School – not perhaps bedtime reading. Peter Brooks’s predecessor, Philip Whitting, was a renowned expert on Byzantine coinage and history, and

was awarded an honorary doctorate by Birmingham University in recognition of his scholarship and of his gift of his coin collection to the Barber Museum in the university.

In short, they were a donnish bunch of people who taught in a donnish way, which prepared those of us who were considered suitably academic very well for Oxford and Cambridge. In my day there rather less interest was shown in those who were not so academic, and that is a valid criticism of the School as it once was, and a complaint I sometimes hear from alumni. But the academic achievements were considerable: among historians, we can count prominent figures such as Gareth Stedman Jones (1956-61) and Paul Ginsborg (1958-63); among classicists ML West OM (1951-55), Paul Cartledge (1960-64) and Robert Parker (1964-67). At least three of those stand or stood firmly to the Left politically; but, as Paul Ginsborg remarked to a radical colleague at his Cambridge college who disliked admitting undergraduates from independent schools, “All the best revolutionaries come from public schools”.

Independent schools have for some years felt under pressure as the top Russell Group universities insist they want to concentrate heavily on admitting students from the state sector. And independent schools will soon be feeling the pressure if legal challenges to the imposition of VAT on school fees fail (legislation to impose VAT may well be in breach of the European Court of Human Rights). Far more productive for society than taxing school fees would be vocal support for the efforts alumni and benefactors have been making to ensure that the great schools of England, among which St Paul’s has always been counted as one of the most prominent, can offer as many bursaries (including full ones) as possible and move towards needs-blind admission. The number 153 for some reason comes to mind.

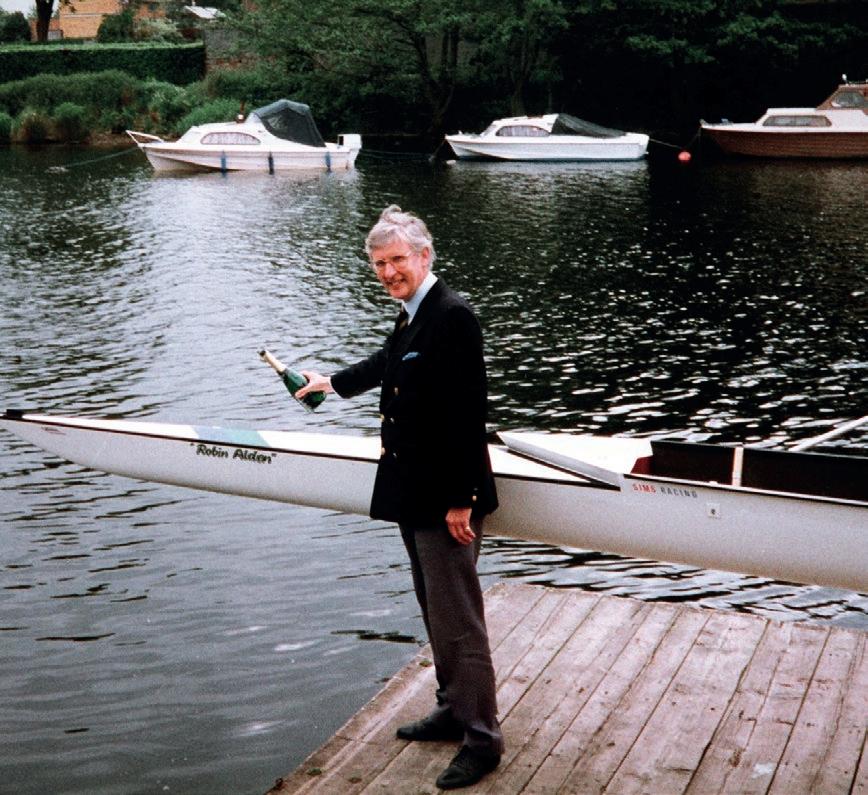

Robin Dodd (1961-65), with much help from his son James, who qualified and competed in the Diamond Sculls at Henley 2024 and received his PhD in Prehistoric Archaeology/Rock Art from Aarhus University this year, shares his memories of Robin Wenham Alden MA, Assistant Master English and History, pioneer rowing coach (1962-65)

Time has come to tell the whole tale of one whose life was giving enjoyment and learning to others, enriching their lives, not least my own. Robin “Bunny” Alden was the first to bring modern circuit training to St Paul’s School Boat Club in 1963, setting the stage for future Henley wins of the luminaries described in Jonathan Whybrow’s (1974-78) excellent article in Spring 2024’s Atrium. Robin was an iconic coach, far ahead of his time, and I would like to recognise his part in laying these foundations, along with his predecessors, such as Freddy Page and Red Brown.

Robin was born and bred in Oxford, where he died aged 81 and his funeral was held in St Giles. St Edward’s (Teddies) was his alma mater, and he would have been very proud of both schools as the blustery, sunny intervals of wind-swept Henley in this year’s semifinal of the Princess Elizabeth Challenge, which saw SPSBC beat SESBC, the defending champions.

Robin’s circuit training was a great shock to the system, but quickly won over sceptics. His boyish, over-the-top enthusiasm is remembered for half killing us in Great Hall, then on the River, where we broke “flat ice and growlers” in the coldest winter in living memory, January 1963. That spring, SPSBC was ultra-competitive, Robin’s Colts A (J16) the most extreme, the hardest seats to get into for us Juniors. His cross training was a tense, fast boot camp – press-ups, vigorous exercise against the clock, weights, isometrics and skipping ropes.

By 1963, Boggo Bennett had succeeded Freddy Page as President of SPSBC, and the autumn before we sang in Alec Harbord’s Revue:

“Old Uncle Freddy and All” to the tune of “Uncle Tom Cobley, Widdecombe Fair”. I helped with the wording of the song, “Mr Brown, Mr Bennett, Mr Allport, Mr Alden and Old Uncle Freddy and All” and sang in the chorus while the audience thundered. In 1964, Robin brought the house down with fellow English Master, Peter Raby in the Masters’ Sketch. They played a pair of complacent civil servants.

At St Paul’s he was angered by the inflexible streaming system that dropped Geography in 6A, and that his talents in German were wasted. He was ahead of his time, same as in SPSBC and his outside coaching of London University.

Robin “Bunny” Alden had an enormous innate sense of fun, the 1965 photograph with me in the Stewards’ Enclosure at Henley says it all about ‘The Two Robins’, when the shutter went down and Bunny’s ice cream

actually broke, in hindsight reflecting a very poignant moment in his life to come. A wonderful raconteur, he had my family in fits over dinner with his story of his climb of Henley Church with a saucepan on his head, after the 1955 Regatta Ball. According to Worcester College, this is not one of their regular “rites of passage”.

In 1965, Robin Alden returned to Teddies, teaching English and coaching rowing under the legendary Cambridge Blue, John Vernon, who retired in 1968. Robin took over and Teddies reached the 1969 National Schools’ Final. In the months before, I met with Robin and Christine before the roaring fire of an Oxfordshire inn; it was like a scene from Falstaff We were lucky to finish our excellent dinner before the arrival of the Bullingdon Club. That evening, Robin told me of the turning point he faced, having achieved as much as he could as a coach in school rowing.

Robin was greatly interested in my pastures new at the Royal Agricultural College, Cirencester, high in the hills, away from rowing. Listening carefully for my response, he told me he had the chance of Head of English at non-rowing Rugby School. I recall telling him: “It doesn’t matter what the rest say, you’re bound to leave them far behind.” which is from the famous song, Old Father Thames. We all agreed, particularly Christine, on the pressures faced in school rowing, by coaches and oarsmen alike, having to be totally focused to the exclusion of everything else.

In hindsight, our conversation exactly fits with a letter Robin wrote to the Provost of Worcester College in 1954, “The results could have been better, and probably they should have, but I knew the gamble when I took on Captain of Boats in October, I think it was worth it and I hope you do not disagree”. As a fresher in 1952, his boat came second in Torpids. He graduated with Third Class Honours, English Language and Literature, and qualified for his MA in August 1958.

He knew the gamble as before, this time he was married, older and wiser, he knew he had to put his growing family and academic career first. The letter to the Provost, I believe, holds the key to the puzzle which I understand has perplexed many of the staff and pupils where he had taught, namely, why such an outstanding school rowing coach turned away from rowing in sight of the summit of his school coaching career.

Teaching history to the Lower Eighth in 1964, Dr Brooks, bizarre as ever, used to eulogise over Renaissance reformers ending up in a “cold douche” for ardent zealots. Like a more practical zealot, Robin decided to get his teeth

“Bound upon the old ways, Splendour of the past comes shining in the spray.”

Songs of the Fleet, Sir Henry Newbolt, 1910.

into something without getting wet.

The Wind in the Willows and The Teddy Bears’ Picnic were over for him. In the same year as his friend and colleague, David Porteus, became SPSBC President, for 20 years, Robin took Rugby School by storm in 1970, as Head of English and Drama, revolutionising the department, leaving a huge impact on the school where he stayed for 24 years. Ever challenging conventional values with his pupils, Robin was true to form in his arrival interview at Rugby School in 1970. “If you’re not going to have a syllabus made up of prescribed texts and dates, and I don’t want syllabus of this sort, then the man teaching becomes more important than what is covered”.

Robin had an expression “However quixotic this might seem”, which he used in a letter to my parents dated 7 March 1963. Like the hero of Cervantes, Robin Alden was an enthusiastic visionary inspired by lofty and chivalrous ideals, but with a difference. Many of his ideals were realisable and not just impossible dreams. The proof of the pudding is Anthony Horowitz, well-known author and screen writer (Series I and II, Midsomer Murders and Foyles War), who was one of Robin’s first pupils, 1970 to 1973 and who was greatly inspired by him.

In 1983, Robin became a House Master at Rugby School, the school magazine The Meteor recorded: “Christine brought to the House a gentleness of spirit and unassuming good sense, recognised by all who knew her.” Robin’s sons joined Town House, as did daughter Philippa in the Sixth Form; the happy photograph of Robin and Christine at their son Jonathan’s wedding was taken two years before she died of cancer in 1993.

Robin sang Floreat Rugbeia for the last time in 1994. He planned to settle back in Oxford, perhaps coaching for Teddies again or Leander, according to The Meteor. His life had turned full circle, a “Dance to the Music of Time” to quote the novelist, Anthony Powell. As the Summer Term ended, Robin announced his engagement to Mrs Anne Carstairs, who had been a bridesmaid at Robin and Christine’s wedding in April 1956 and widow of one of Robin’s oldest friends. They married in September 1994 and The Meteor reported they would be living in Oxford and wished them every happiness.

Robin also taught and coached at King's Chester from 1955 to 1961, before coming to St Paul's. Three days after Robin’s funeral in 2014, the King’s Chester boat which carried his name competed with a black silk ribbon on her bow in the Northern Schools’ Head, as did the other King’s Chester boats, all bearing a black ribbon, and their boathouse flag in Chester, fluttered at half-mast.

His cross training was a tense, fast boot camp – press-ups, vigorous exercise against the clock, weights, isometrics and skipping ropes

Acknowledgement: Thanks are extended to the archivists of the following institutions for kindly supplying material and information: Worcester College, Oxford; St Edward’s School, Oxford; King’s School, Chester; St Paul's School and Rugby School.

Old Pauline Club Archivist, Kelly Strickland, has raided the Club’s trophy cupboard and made some fascinating discoveries.

1. This mug was won by the Science Form in 1899 in a Tug of War competition between Science and Classics. The competition was started in 1877 between current Paulines and Old Paulines with the boys winning. In later years, the competition was between the Science, Mathematics and Classics streams in various combinations. The clipping from The Pauline shows the results from 1877 to 1891.

2. The SPS Cadet Corps Lloyd-Lindsay Competition Trophy was first awarded in 1897 to R Sprague (1892-98). The trophy was awarded until 1919 to TH Just, I Mavor (later School Chaplain), SJ Fisher, W Rowe, CS Wink, CH Evans, M Webb, C Sprague, and TC Hunt. The Lloyd-Lindsay Competition was started in Britain by Colonel Sir James Lloyd-Lindsay around 1873. The Pauline (July 1891) describes the competition as “A half-mile race in uniform over several obstacles, three volleys being fired at each of four halts”.

3. This trophy with amazing dragon detailing was given to the School by the Association of Old Paulines in China in commemoration of the School’s fourth Centenary in 1909. It is currently being used as the House Cup.

5. This SPS Boat Club Senior Sculling mug was awarded to SH Peploe (1934-38) in 1937. Peploe was then entered in the Junior Sculls at the Richmond and Twickenham Regatta where he unfortunately lost in the final by half a length. Peploe was in the 1st VIII and a prefect in 1937.

4. The Mid-Day Cricket Cup which was given to the School in 1921 by Percy W B Tippetts (1892-94). He also gave a similar cup for football.

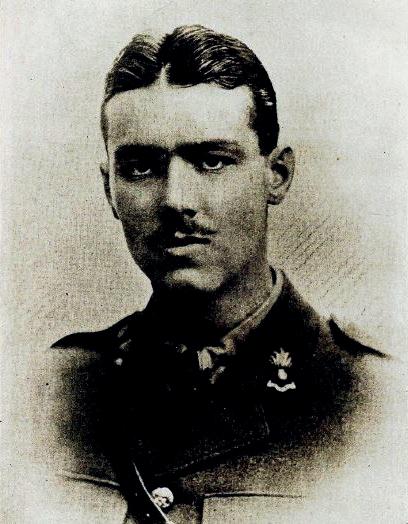

6. The Lambert Cup was given to the School in honour of Lieutenant Cecil JN Lambert (1910-16). Lambert died in World War I on 2 September 1918. The cup was presented by his father in 1919 as a challenge cup for Senior Pairs rowing. Lambert was a Prefect and Captain of the Boat Club in 1916. His picture can be seen here from The Pauline magazine.

Selwyn Jepson (1913-18) was chief recruiting officer or talent spotter for the Special Operations Executive (SOE) French Section.

He recruited agents such as Francis Cammaerts, Violette Szarbo, Noor Khan and Odette Churchill. After service in the Tank Corps in the First World War, he attended the Sorbonne “to improve his French”, travelled extensively in Europe, was involved in film and theatre, and wrote adventure and romance books.

When interviewed after the Second World War he stated: “I was responsible for recruiting women for the work, in the face of a good deal of opposition, I may say, from the powers that be. In my view, women were very much better than men for the work. Women, as you must know, have a far greater capacity for cool and lonely courage than men. Men usually want a mate with them. Men don't work alone; their lives tend to be always in company with other men. There was opposition from most quarters until it went up to Churchill, whom I had met before the war. He growled at me, “What are you doing?” I told him and he said, “I see you are using women to do this,” and I said, “Yes, don't you think it is a very sensible thing to do?” and he said, “Yes, good luck to you.” That was my authority”!

High Master John Bell, when he heard that Lewis Hodges (1931-33), later Air Chief Marshall Sir Lewis Hodges KCB DSO DFC, had been accepted at RAF College at Cranwell said, “they seem to be taking anyone these days.” Hodges joined Bomber Command in 1938. Two years later he crashed landed in Brittany and was imprisoned near Nimes, and then in Spain, before being repatriated. From 1941 Hodges commanded 161 Squadron tasked with

flying the SOE agents into and out of occupied France in short take-off and landing Lysanders. Among his passengers back to England were two future French Presidents, Vincent Auriol and Francois Mitterand. He finished the war based in Calcutta, flying clandestine missions over Japanese occupied territory.

Leopold Marks (1934-37) was chief cryptographer of Special Operations Executive and also briefed agents such as Violette Szarbo. Agents were given poems for cypher purposes and he wrote the famous poem The Life that I Have for Violette Szarbo and it is used in the film Carve her name with Pride (1958). In later life he was a habitué of the Special Forces Club.

The Life That I Have by Leo Marks

The life that I have Is all that I have And the life that I have Is yours

The love that I have Of the life that I have Is yours and yours and yours.

A sleep I shall have A rest I shall have Yet death will be but a pause For the peace of my years In the long green grass Will be yours and yours and yours.

Captain Jenkin R O Thompson (1926-28) RAMC was awarded the George Cross when he was killed in action while serving on HM Hospital Carrier St David.

The ship was repeatedly dive-bombed and ultimately received a direct hit off Anzio in January 1944. He organised parties to carry the seriously wounded patients to safety in lifeboats, inspiring all to prompt and efficient action by his coolness and resource, and was thus instrumental in saving many lives. However, when the ship was obviously about to founder and all were ordered to save themselves, he returned alone to the ship in a last effort to save the one remaining helpless patient still lying trapped below decks and selflessly remained with him when the ship sank.

Thompson had previously served on HM Hospital Carrier Paris at Dunkirk in May 1940.

Citation

The King has been graciously pleased to approve the posthumous award of the George Cross, in recognition of most conspicuous gallantry in carrying out hazardous work in a very brave manner, to: Captain Jenkin Robert Oswald Thompson (115213), Royal Army Medical Corps (Claygate, Surrey).

On 24 May 1941 HMS Hood, nicknamed The Mighty Hood, and The Prince of Wales intercepted the German battleship Bismark and battle cruiser Prinz Eugen in the Denmark Straits between Greenland and Iceland.

At around 6am HMS Hood exchanged fire with Prinz Eugen and, after six salvoes, a hit from the Bismark caused a massive explosion that sank the Hood in three minutes with only three of its 1,418 crew surviving.

Able Seaman Neil Hamilton Douglas (1935-39), aged 19, was one of those who died and whose name is on the Portsmouth War Memorial. His entry in the St Paul’s School Register 1905-1985 shows he was born in 1921, son of W E Douglas, Civil Engineer. He was Captain of Boats.

Another Old Pauline, Commander Douglas Hunt (1929-34) DSC* RNVR was due to join the Hood but had caught measles and was recuperating at home when the Hood was lost. Douglas had been the Old Pauline squash champion in 1939, and regained his title in 1947, holding it again from 1951 to 1957; he was the Old Pauline Squash Club’s honorary secretary from 1938 to 1973. His obituary in The Daily Telegraph concludes, “Duggie Hunt never married; but while some foxes got away from him in the field, few pretty riders escaped his clutches”.

At the last Paris Olympics in 1924, an OP represented Great Britain at tennis, Jack Gilbert (1901-03).

He lost in the last 16 to Harada of Japan in four sets. Jack did not play tennis at St Paul’s but learnt the game from a French intern (along with seven other OPs) at Ruhblen near Berlin during World War 1. In the same year as the Olympics, Jack won the mixed doubles at Wimbledon, partnered by Kitty McKane (later Godfree) who was briefly at St Paul’s Girls’ School.

Atrium (unless otherwise described) uses reviews provided by authors or their publishers.

David Herman (1973-75) reviews a new biography of Sefton Delmer (1917-23)

Peter Pomerantsev is a Soviet-born British journalist and author. His latest book, How to Win an Information War: The Propagandist Who Outwitted Hitler (2024), is about Sefton Delmer, a British propagandist during World War II.

Delmer, known as “Tom”, to his friends and family, was born in Berlin in 1904, the only son of Professor Frederick Sefton Delmer (an Australian lecturer in English at Berlin University) and his wife, Mabel Hook. In 1914 his father was arrested and interned by the Germans. He was released in 1915. In May 1917 the family moved to Britain, but his father returned to Germany after World War I.

Sefton was educated at St Paul’s where he made the rowing team and won a scholarship to Oxford. He later wrote, “I can … look back on my time at Oxford and St Paul’s as a very happy period in my life.” In 1928 he became the Berlin correspondent for The Daily Express. He was the first British reporter to interview Hitler. He then became the Paris correspondent and from 1936 he covered the Spanish Civil War.

In 1940 Delmer’s career took a dramatic turn. From 1940 for five years, Delmer became the Head of Special Operations for Britain’s Political Warfare Executive, making “black propaganda” radio broadcasts to Germany. As Pomersantsev writes, “He edited a daily newspaper and oversaw a whole industry of leaflets stimulating desertion and surrender, fake letters, fake stamps, and a vast array of rumours, gossip… all intended to break the spell cast by the Nazis.”

Many of Delmer’s team were Germanspeaking Jewish refugees. One of their most intriguing radio characters was der Chef, a character who loved the German army but hated the Nazis. He was played by Peter Hans Seckelmann, a mild-mannered German novelist of Jewish descent. There was a strange civil war between Delmer’s team and the worthy intellectual emigres who worked for the BBC German Service and wanted to convert ordinary Germans to their high liberal or socialist ideals. Listening to them, Delmer later wrote in his memoirs, was like “Maida Vale calling Hampstead”. This, Delmer thought, would never work. This antagonism was reciprocated by refugees like Karl Otten. “Everyone at the BBC knows that Sefton Delmer is a fifth columnist”, Otten wrote. But Delmer used the testimony of other refugees to give authentic details to his broadcasts.

Others recruited by Delmer included Peter Wykeman (née Weichmann), Rene Halkett (née Freiherr von Fritsch), Father Elmar Eisenberger, an Austrian priest, and Agnes Bernelle, and the writers, Muriel Spark and David Garnett.

Delmer wanted broadcasts that would speak to ordinary Germans and undermine their faith in Nazism, building a divide between them and the party. He believed that many Germans were not idealists or passionate Nazis and he wanted to tap into this lack of idealism. It worked. Delmer’s broadcasts later moved to the BBC. “The estimated audience for the BBC German broadcasts,” Pomerantsev writes, “was now [in

1945] between ten and 15 million a day – up from one million in 1941.”

After the war Delmer returned to The Daily Express, published two volumes of memoirs, Trail Sinister (1961) and Black Boomerang (1962), and wrote two other books, Weimar Germany (1972) and The Counterfeit Spy (1973). He died in 1979.

Delmer will be remembered for his contribution to the war effort. He and his unlikely team helped break the hold of Goebbels’ propaganda machine and played an important part in helping Britain win the Information War.

Richard Davenport-Hines is the author of biographies of Dudley Docker, W. H. Auden, Marcel Proust, Lady Desborough and Maynard Keynes. He has written histories of sex, drugs, arms-dealing, the sinking of the Titanic and the Profumo Affair, as well as editing three volumes of correspondence and journals of Hugh Trevor-Roper.

History in the House pulls back the curtains on Christ Church, Oxford and reveals its great and lasting historical significance. This is an historiographical study. It shows the evolution of historical ideas, purposes and methods in a clerisy that has enjoyed conspicuous influence in England for six centuries. There was growing recognition in Tudor England that the study of history especially improved the minds, enlarged the imaginations and broadened the vicarious experience of princes, noblemen and administrators. History showed, by precept and example, good government and bad, virtue and vice in rulers, and the reasons for the success or failure of states.

History in the House looks at the temperaments, ideas, imagination, prejudices, intentions and influence of a select and self-regulated group of men who taught modern history at Christ Church: Frederick York Powell, Arthur Hassall, Keith Feiling, JC Masterman, Roy Harrod, Patrick Gordon Walker, and Hugh Trevor-Roper: a Victorian radical, a staunch legitimist of the protestant settlement, a conservative, a Whig, a Keynesian, a socialist and a contrarian.

Nikhil Krishan reviewing in The Spectator writes, “And what of the anecdotes? Here, the author delivers the goods on nearly every page. ‘Jumping your full-stops – that is the Oxford accent,’ one don is quoted as saying. ‘Do it well and you will be able to talk forever’”.

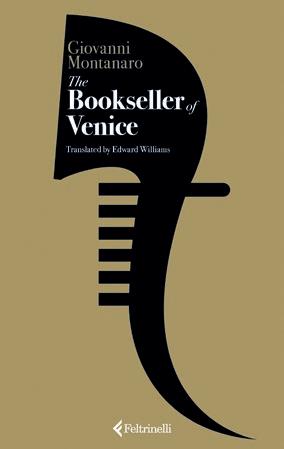

Translated by Edward Williams (Modern Languages and Creative Arts departments 1983-2020)

In Venice’s Campo San Giacomo you’ll find Moby Dick, one of those bookshops “you’re always surprised to discover still exist …” The bookseller is Vittorio, he’s just over 40, lives for his books and fights to be able to go on selling them. One day he meets Sofia, bright-eyed and quick-witted, who makes a habit of going to see him there.

On 12 November 2019, however, 187 centimetres of an exceptional acqua alta, flood the houses and shops, and submerge Vittorio’s bookshelves. The books drown “and the whole of Campo San Giacomo is full of lost books, and at that moment it seems as if everything is lost”.

Giovanni Montanaro experienced first-hand the tragic days of the flood that shook the world. But he also tells another story, not only describing the anxiety of the rising water, but revealing another Venice: the young people, the Venetians, the joy which won out amid the devastation, springing from people’s ability to help each other. And most of all the booksellers, the love of books and the love which books engender, the determination to salvage at all costs the things that are most dear.

Readers and booksellers have been moved by this story, which evokes Venice and its magnificent uniqueness but becoming, at the same time, a symbol for every tragic emergency and every human rebirth.

Giovanni Montanaro (Venice, 1983) is a writer and lawyer. He is the author of Il libraio di Venezia (Feltrinelli, 2020) and also La croce Honninfjord (Marsilio, 2007), Le conseguenze (Marsilio, 2009), Tutti i colori del mondo (Feltrinelli, 2012, Premio Selezione Campiello), Tommaso sa le stelle (Feltrinelli, 2014), Guardami negli occhi (Feltrinelli, 2017), Le ultime lezioni (Feltrinelli, 2019) and Come una sirena (Feltrinelli, 2023). He has been translated into French, German, Spanish and Portuguese. This is the first translation of his work into English.

Hugh Wilford, an historian of US intelligence explores how the CIA was born in anti-imperialist idealism but swiftly became an instrument of a new covert empire both in America and overseas.

As World War II ended, the United States stood as the dominant power on the world stage. In 1947, to support its new global status, it created the CIA to analyse foreign intelligence. But within a few years, the Agency was engaged in other operations: bolstering proAmerican governments, overthrowing nationalist leaders, and surveilling anti-imperial dissenters in the US.

The Cold War was an obvious reason for this transformation – but not the only one. In The CIA, celebrated intelligence historian Hugh Wilford draws on decades of research to show the Agency as part of a larger picture, the history of the Western empire. While young CIA officers imagined themselves as British imperial agents like T. E. Lawrence, successive US presidents used the covert powers of the Agency to hide overseas interventions from postcolonial foreigners and anti-imperial Americans alike. Even the CIA’s post-9/11 global hunt for terrorists was haunted by the ghosts of empires past.

Comprehensive, original, and gripping, The CIA is the story of the birth of a new imperial order in the shadows. It offers the most complete account yet of how America adopted unaccountable power and secrecy, both at home and abroad.

Alex Paseau is Professor of Mathematical Philosophy at Oxford University. His latest academic book, The Euclidean Programme, co-authored with Wes Wrigley, examines Euclid’s philosophical legacy.

Euclid’s Elements, written in about 300 BC, is a famous textbook of ancient Greek geometry. Over the course of 13 books, Euclid derived the geometry of his day theorem by theorem, in a cumulative manner. The Elements took pride of place in at least three brilliant mathematical cultures – ancient Greek, mediaeval Arabic, and early modern European – and was a cornerstone of the school curriculum in the West from the Renaissance until the 20th century.

The Elements embodies a certain vision of the highest form of human knowledge – especially mathematical knowledge – as obtained by deduction from self-evident first principles. Paseau and Wrigley explain how this vision evolved over the millennia, from antiquity to the early modern period and into the twentieth century. They then assess its philosophical merits. Overall, the book offers a superb combined historical and philosophical analysis of the ideal Euclid’s Elements inspired.

Graham Greene meets David Lean in Murder in Constantinople – an historical murder mystery in which a wayward boy from London’s East End is pulled into the hunt for a serial killer on the eve of the Crimean War in London, 1854.

Twenty-one-year-old Ben Canaan attracts trouble wherever he goes. His father wants him to be a good Jewish son, working for the family business on Whitechapel Road, but Ben and his friends, the ‘Good-for-Nothings’, just want adventure. Then the discovery of an enigmatic letter and a photograph of a beautiful woman offer an escapade more dangerous than anything he’d imagined. Suddenly Ben is thrown into a mystery that takes him all the way to Constantinople, the jewel of an empire and the centre of a world on the brink of war. His only clue is three words: ‘The White Death’. Now he must find what links a string of grisly murders, following a trail through kingmaking and conspiracy, poison and high politics, bloodshed and betrayal.

In a city of deadly secrets, no one is safe – and one wrong step could cost Ben his life.

David Arrowsmith is proudly half-Colombian. In fact, he is the great-grandson of a former President and directly descended from four more. He now lives in Hove with his family, where his paternal great-grandfather worked in a butcher’s shop. He has played football for over 35 years and has no plans to stop just yet. David worked in the television industry for over 20 years – originating, developing and producing documentaries and unscripted programming for companies such as October Films, DSP, OSF, Zig Zag, Channel 5, Granada Television and the BBC.

Narcoball uncovers the incredible story of Colombian football during the early 1990s – shaped by drug lords, rivalries, and ambition. It uncovers a football empire backed by cartels where victory was a currency of its own, and defeat, a matter of life and death.

This is a different story of Pablo Escobar and his rivals. A tale of clandestine deals that reshaped Medellin’s football clubs, where fortunes were won and lost. It unveils the extraordinary bonds that Escobar forged with football’s luminaries and why his influence reached unprecedented heights, leading to the astonishing 5-0 victory over Argentina in Buenos Aires, the murder of referees, and the ruthless coercion of officials culminating in the killing of Andrés Escobar – the Colombian defender who paid the ultimate price for an own goal in the 1994 World Cup. It is also an examination of a people’s relationship with both the sport and the nefarious leaders that brought both pride and terror to their communities. Set against the US War on Drugs, international threats, and government clampdowns, this is a gripping exploration of Colombian club football under Escobar’s rise and fall.

Ammar Kalia is a writer, musician and journalist living in London. Since 2019, he has been The Guardian’s Global Music Critic and he has written for publications including The Observer, BBC, Dazed, Mixmag, Economist, Downbeat and Crack Magazine

A PERSON IS A PRAYER is an intensely moving, lyrical and often funny novel about a family whose story of migration from Kenya and India to England is told over three separate days, across six decades.

Bedi and Sushma’s marriage is arranged. When they first meet, they stumble through a faltering conversation about happiness and hope and agree to go in search of these things together. But even after their children Selena, Tara and Rohan are grown up and have their own families, Bedi and Sushma are still searching.

Years later, the siblings attempt to navigate life without their parents. As they travel to the Ganges to unite their father’s ashes with the opaque water, it becomes clear that each of them has inherited the same desire to understand what makes a life happy, the same confusion about this question and the same enduring hope.

A PERSON IS A PRAYER plumbs the depths of the spaces between family members and the silence that rushes in like a flood when communication deteriorates. It is about how short a life is and how the choices we make can ripple down generations.

“An exquisitely written, incisive and evocative family saga. Kalia explores cultural complexity and human frailty with compassion, wit and generosity of spirit” – Jake Lamar, author of Viper’s Dream

Nick Brooks spent 40 years working in the City of London as a chartered accountant. When he retired in 2018, he wrote and published his first novel, Betrayed His second novel, Revenge, is a sequel. Nick is the OPC Treasurer and a Vice President of the Club. He lives in Chiswick and is the fourth generation of his family to live in this leafy suburb.

In Revenge, a London lawyer is under suspicion from both the police and SO15 for two murders and running a business of supplying arms to terrorists. Will Slater had hoped that the terrifying experience in helping to break up a terrorist arms gang was buried in the past. However, a newspaper article questioning the disappearance of the terrorist money awakened old memories and hatred. Hiding in a remote Scottish glen in an ancient mansion with his wife Jay, Will discovers that the house also has secrets that he must unravel.

Unaware that a contract has been placed on his life from inside prison, he has become the target of ruthless killers once again. Convinced that he is being constantly watched and fearful for his family’s life, Will realises that he must act himself if they are to survive. Unwittingly helped by his old adversary Inspector Dawkin, both men converge on the truth that will finally reveal who is seeking revenge.

Sam Grabiner (2007-12) is the 2024/25 Writerin-Residence at The National Theatre Studio and is under commission at Manhattan Theatre Club. He is a MacDowell Fellow, and a graduate of the Royal Court Young Writers Programme. Sam’s play, Boys on the Verge of Tears was the 2024 Stage Debut Award winner for Best Writer, the 2022 winner of the Verity Bargate Award, and has been performed at the Soho Theatre. Alongside his theatre work, Sam is under commission at the BBC and is developing his debut feature with 2AM.

Ollie Madden (1990-95), Director of Film4, is expanding his role to encompass TV drama commissioning as part of the ongoing restructuring at the UK broadcaster. “Ollie is a creative powerhouse who has been at the heart of Film4’s extraordinary success and has a bold and ambitious vision for what Channel 4 drama can be,” said Ian Katz, Channel 4’s Chief Content Officer. There were six Oscar wins for Film4-backed features at this year’s ceremony, including Poor Things and The Zone Of Interest. Further Film4 productions are BAFTA-winners Earth Mama and All Of Us Strangers. Madden became Director of Film4 in May 2022 having been appointed Head of Creative there in 2016. He had previously worked extensively throughout the UK film and TV sector, including at Miramax and Warner Bros, and as Head of Film at Shine Pictures.

Lord Terence Etherton (1963-68) was awarded the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE) in the recent Honours list. A retired judge and member of the House of Lords, he was Chair of the Law Commission of England and Wales, Chancellor of the High Court and Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice in England and Wales. In 2022, he was appointed Chair of the LGBT Veterans Independent Review, published in July 2023.

Louis Wilson (2017-22) was Oxford Union President for Trinity Term in 2024. Louis had been elected Librarian but, following a decision by an Appellate Board, he became President.

James Small-Edwards (2010-15), representing Labour, took the West Central London Assembly seat for the first ever time in the election in May winning by just over 4,000 votes. Small-Edwards promised continued support for the cost-of-living crisis, alongside more affordable and social housing and action to combat climate change.

Adam Jacobs (198892) has become Chair of the National Association of Jewellers. After graduating from Bath University with a degree in Business Administration, he worked between 1997 and 2003 for Marks & Spencer on their graduate training scheme, as well as a marketing agency in Clerkenwell. Joining the family jewellery business in 2003, he grew the business into an award-winning, nationally-recognised independent retailer. Supporting fledgling gold and silversmiths, he founded an Emerging Designers competition, now in its tenth year. He is also a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths and serves on the advisory panel to the Court of Wardens.

Floyd Steadman OBE has been appointed as one of five new Deputy Lieutenants for Cornwall. Floyd’s careers have spanned elite rugby, as captain of Saracens, and education as Headmaster at several prep schools after his time at St Paul’s. Amongst his other commitments, Floyd, now travels the length and breadth of the country to talk to people and students about unconscious bias. He was awarded an OBE in the King’s first New Year’s Honours in 2023 for services to rugby, education and charity. Peter King (1967-71), Classics Department and non-academic staff since 1976, writes “Floyd was the first black teacher at St Paul’s and a superb colleague. He remains incredibly proud of his status as an Honorary Old Pauline”.

The recent General Election saw several OPs elected as Members of Parliament. James Murray (1996-2001) continues as MP for Ealing North. He was appointed Parliamentary Secretary (Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury) at HM Treasury on 9 July 2024. For the Conservative Party Tom Tugendhat (1986-91) retained his Tonbridge seat and Lincoln Jopp (1981-86) was voted in as the new MP for Spelthorne.

In December 2023, the Old Pauline Club convened the first online meeting of an LGBTQ+ discussion group. There have been three meetings so far of gay and transgender Old Paulines and allies, and the group has been named Old Pauline Pride with a mission to support the network, promote itself to the community, and to socialise.

As part of the promotion, Atrium asked me to coordinate a conversation with some members of the group, and a wide cross-section of ages, from a 1968 leaver to the current OPC Secretary who left in 2016, has participated.

I think some initial contextualisation is important as the unanimity with which our contributors declare that the School, across five decades, did nothing to support their development as gay people needs some explanation.

My own experience and perspective as a member of staff is perhaps helpful here. In 1967, the year I went to Cambridge, private homosexual acts between two consenting males aged 21 or over were decriminalised. In 1994 the age of consent was lowered to 18, and to 16 in 2001. I taught at St Paul’s from 1989-2014. From 1988-2003, Section 28 of the Local Government Act prohibited the promotion of homosexuality in schools. The negative atmosphere that generated permeated most of my career at the School. It meant that one High Master vetoed an article for the School newspaper in which a Pauline wished to explain how difficult it was for him to be gay in a school with a prevailing homophobic culture. It meant that when a tutor pupil asked me about my sexuality, I felt obliged to prevaricate, compromising a relationship which should have been founded on trust and truthfulness.

In 2007, when I entered a civil partnership (the first in the Common Room), I informed the next High Master

and he offered to announce it to the CR. That brave new world did not last long because accusations of historic sex abuse were levelled against the School. In the press and in the Serious Case Review at the end of Operation Winthorpe, the disgraceful elision of homosexuality and paedophilia was all too readily made. One positive outcome of the safeguarding provisions subsequently introduced is that the School has a Head of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI): Tyler John has contributed an afterword to our conversation.

Let me introduce our participants.

Lord Etherton (1963-68) has had a most distinguished legal career culminating in the office of Master of the Rolls. Terence met his husband, Andrew, 45 years ago and has been openly gay since being sworn in as a High Court judge. After a civil partnership in 2006, he was married in December 2014 on the first day on which this was possible. The majority of the senior judiciary attended the ceremony. He became a peer in 2020 and, in 2022, was commissioned to conduct a review of the official policy of HM Armed Forces between 19672000 to ban LGBT people from military service. All 49 recommendations of his report, published in 2023, have been accepted in principle.

Tim Cohen (1974-79) is a Chartered Accountant and is in a professional and personal partnership with his husband, the sculptor Bruce Denny. They have two children. He is the coordinating chair of OP Pride.

James Croft (1997-2001) had a distinguished academic career at both Cambridges, with a D.Ed from Harvard where he was a Teaching Fellow. He

became Senior Leader at the Ethical Society of St Louis and is now University Chaplain and Lead Faith Adviser at the University of Sussex, the first Humanist Lead Chaplain of any UK university. He is married to Kolten.

Joe Mathewson (1998-2003) created the Firefly Learning Platform with a Pauline contemporary while at the School and after Oxford grew the business to serve 900 schools in 50 countries. He is currently a selfemployed Strategic Adviser. He is married to Jim.

Adam Swersky (1998-2003) is the CEO of Social Finance, a not-for-profit organisation tackling social problems in the UK and globally. After Cambridge and an MBA from INSEAD, he worked for the Boston Consulting Group and was for eight years a Harrow councillor.

Sam Turner (2011-16) is on the OPC Executive Committee. He graduated from Buckinghamshire New University and is a First Officer at British Airways. He has worked part-time at the School in various roles, including as a rowing coach. He married Finlay in September 2024.

John Venning (JV): What was your experience of growing up gay at St Paul’s?

Terence Etherton (TE): I was certainly aware by that time that I was sexually attracted to other boys and men. My parents, however, were traditional Jews and my father was quite a strict person. I went to a youth group in our synagogue, which included several Paulines. I wanted to fit in and so I had girlfriends. The constraint on any gay activity was reinforced when, in the early part of my time at St Paul’s, I became aware of a rumour that a boy had been expelled for sending a love letter to another boy.

Tim Cohen (TC): At 13 I was aware of my attraction to other males and had quiet crushes on a number of boys at School, mainly older ones as they seemed more manly than my age group. I didn’t act on any desire and it was a very frustrating time. I was dating girls of my age during my teenage years, as that was what was expected. There was nothing for me to read about or explore or to talk to anyone about. I didn’t really mind as it was all taboo anyway, so I wasn’t missing out (as I saw it).

James Croft (JC): I was 17 when I first tried to tell my parents that I’m gay. The signs were all there. I’d never had a girlfriend. I spent all my free time performing in the theatre and singing in the choir, and for years I’d studied ballet. Boys at Colet Court used to make fun of me for dancing. This was compounded by insensitive teachers, including a woman. One PE teacher was the first person to call me a ‘fag’ – which I didn’t really understand, but I knew it wasn’t good. The teasing and taunts and jokes continued throughout my time at the School until one

I must say there were some positive experiences. Having been involved at the school for eight years since leaving, I have seen positive change and I hope that the change continues.

morning in a School assembly, the then High Master intoned: ‘Homosexuals deserve our pity and our prayers.’ [He used the same formula when refusing permission for the newspaper article. JV] I was sitting among my friends, but I felt totally alone.

Joe Mathewson (JM): Despite a generally excellent education, St Paul’s classroom coverage of sexuality was woefully inadequate. The only reference I can remember was: ‘Sometimes boys have unusual urges but they pass, so don’t worry too much about them.’ Outside the classroom we just didn’t discuss it.

Adam Swersky (AS): I didn’t feel it was a particularly hostile environment, although homophobic slang was common as a form of abuse. I didn’t perceive this to be actively intended to be homophobic – mostly just the vernacular of the time.

Sam Turner (ST): The age-old insult of being ‘gay’ was bandied about regularly, but not being ‘out’ meant that others weren’t to know the full impact of their words on me. It was used as a derogatory term amongst my peers up to when I left; used outside teachers’ hearing, but I am sure it was widely known to be happening. I had a torrid time at St Paul’s. I did not feel comfortable in the macho, repressive culture of my peers. I saw how someone in my year who was ‘out’ was ostracised, made fun of and insulted. The biggest omission was the lack of non-heterosexual sex education in School. I think it says a lot that I learned more from TV programmes than I did at School.

JV: When did you come out? And was this an easy process?

TE: It was not until I was 27, a very junior barrister, that I stopped dating women and met my partner, Andrew. From the time I met him I became comfortable with my sexuality and had many gay friends.

TC: The summer after I left School, I was on a naturist beach in San Diego, California with some gay men. I was chatting to an American who said his boyfriend had just left school in Britain. He was a Pauline in the year below me. I wasn’t aware of him at School. He told me all sorts of things that went on at School of which I was unaware, even some of the boys in my year.

After leaving School I trained as a Chartered Accountant. In those days there were no DEI departments, no LGBTQ+ groups in the workforce and it was as closeted as it was at School. I don’t think that my experience at St Paul’s affected me negatively: we were living in a time when things were different so we kept quiet. It didn’t stop me exploring from the age of 19 to see how life might be, even if it was far less open than now.

JC: I didn’t hate St Paul’s – in many ways I thrived there. I’m enormously grateful for the life the School made possible. But it was not a welcoming or safe space to be LGBTQ+. I sometimes wonder about the experiences I missed out on because I went to a School with a homophobic atmosphere. But now, being a proudly out gay person with a public-facing role in an educational institution, I hope to show young queer people that they can live successful, fulfilled and public lives while being entirely themselves. For me that feels like a moral responsibility and a way to honour the ballet-dancing, choralsinging, scruffy-haired ‘fag’ I used to be.

AS: There was, to my knowledge, no one ‘out’ at St Paul’s during my time there, including me! Ironic given that I found out my best friend (JM) is gay a few months after I left. I felt that being outed at School would be a source of enormous interest and gossip: a disincentive to telling others.