STRATEGIC VISION for Taiwan

Security

Facets of the Gulf Crisis

Implications of Security Transitions

Nayef bin Nahar

Front Command Border Support

Mohammed Ali Khawaldeh

Managing the Crisis

J. Richard Hu

Ankara’s Foreign Policy

A. Engin Oba

The Media Space

Osama Kubbar & Rashid Al Naimi

Family Business

Next Generation of Barzanis to Take Power in Erbil

Dean Karalekas

The Rise of Armed Non-State Actors

Omar Ashour

The Middle East

Special Issue w Autumn, 2018 w ISSN 2227-3646

STRATEGIC VISION for Taiwan Security

Submissions: Essays submitted for publication are not to exceed 2,000 words in length, and should conform to the following basic format for each 1200-1600 word essay: 1. Synopsis, 100-200 words; 2. Background description, 100-200 words; 3. Analysis, 800-1,000 words; 4. Policy Recommendations, 200-300 words. Book reviews should not exceed 1,200 words in length. Notes should be formatted as endnotes and should be kept to a minimum. Authors are encouraged to submit essays and reviews as attachments to emails; Microsoft Word documents are preferred. For questions of style and usage, writers should consult the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors of unsolicited manuscripts are encouraged to consult with the executive editor at xiongmu@gmail.com before formal submission via email. The views expressed in the articles are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their affiliate institutions or of Strategic Vision. Manuscripts are subject to copyediting, both mechanical and substantive, as required and according to editorial guidelines. No major alterations may be made by an author once the type has been set. Arrangements for reprints should be made with the editor. Cover photograph of the ruins at Petra, Jordan,

is

courtesy of Dean Karalekas.

Special Issue w Autumn, 2018 Contents Managing the Gulf Crisis ...............................................................4 Security transistions in the Gulf region....................................... 10 The Gulf Crisis and media space .................................................. 15 Kurdish family values .................................................................. 20 The rise of non-State actors .......................................................... 28 Putting borders front and center ................................................. 37 Turkey and the Gulf Crisis ........................................................... 42 J. Richard

Hu Nayef bin Nahar Osama Kubbar & Rashid Al Naimi Dean Karalekas Omar Ashour

Mohammed Ali Khawaldeh

A. Engin Oba

Editor

Fu-Kuo Liu

Executive Editor

Aaron Jensen

Associate Editor

Dean Karalekas

Editorial Board

Richard Hu, NCCU

Guang-chang Bian, NDU

Chung-kun Ma, NDU

Lipin Tien, NDU

Ming Lee, NCCU

Chung-young Chang, Fo-kuan U

Raviprasad Narayanan, JNU

Chris Roberts, U of Canberra

STRATEGIC VISION For Taiwan Security

(ISSN 2227-3646) Special Edition Number 4, Autumn, 2018, published under the auspices of the Center for Security Studies and National Defense University.

All editorial correspondence should be mailed to the editor at STRATEGIC VISION, Center for Security Studies in Taiwan. No. 64, Wan Shou Road, Taipei City 11666, Taiwan, ROC.

The editors are responsible for the selection and acceptance of articles; responsibility for opinions expressed and accuracy of facts in articles published rests solely with individual authors. The editors are not responsible for unsolicited manuscripts; unaccepted manuscripts will be returned if accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed return envelope.

Photographs used in this publication are used courtesy of the photographers, or through a creative commons license. All are attributed appropriately.

Any inquiries please contact the Executive Editor directly via email at: dkarale.kas@gmail.com. Or by telephone at: +886 (02) 8237-7228

Online issues and archives can be viewed at our website: www.csstw.org

© Copyright 2018 by the Center for Security Studies.

Articles in this periodical do not necessarily represent the views of either the CSS, NDU, or the editors

From The Editor

As we close out the year 2018, we are happy to be able to offer our readers another special issue, which looks at events taking place in the Middle East that have an impact on the military and security issues that continue to affect that dynamic region. We are especially honored to have guest contributors from the region, particularly Qatar, and so the opportunity to examine various aspects and consequences of the recent Gulf Crisis that affected that country and the region so profoundly.

We begin with an analysis by J. Richard Hu, a member of our editorial board and a retired ROC Army major general who is currently a professor of strategy at the ROC National Defense University. General Hu looks at the diplomatic crisis and the comprehensive measures that are needed in order to address this difficult issue.

Dr. Nayef bin Nahar, a political science researcher at the Ibn Khaldun Center for Human and Social Sciences at Qatar University, offers an analysis of how the Gulf Crisis resulted in security transitions in the region, and what the consequences of this are for Qatar. Next, Dr. Osama Kubbar, an international relations expert and strategic analyst at the Qatar Armed Forces Strategic Studies Centre, and Dr. Rashid Alnaimi, a brigadier general in the Qatar Armed Forces, take an in-depth look at the media space, including persuasion and propaganda efforts, during the Gulf Crisis.

Strategic Vision’s associate editor, Dean Karalekas, has just returned from a visit to the Middle East region and offers his analysis of the leadership transition in Iraqi Kurdistan, where longtime President Massoud Barzani, who stepped down after last year’s contentious referendum, is passing power on to the next generation of his influential family.

Next, Dr. Omar Ashour, who is an associate professor of strategic and security studies at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, looks at the rise of armed non-State actors and how today’s Middle East is proving to be fertile ground for this scourge. Dr. Mohammed Ali Khawaldeh returns to the pages of Strategic Vision with an examination of Front Commands and their role in supporting Border Troops in the fight against terrorism. Dr. Khawaldeh is a retired brigadier general in the Jordanian Armed Forces.

Finally, we round out our last issue of the year with an article by Professor A. Engin Oba, a former ambassador and the head of the International Relations Department at Turkey’s Çağ University, who examines Turkish Foreign Policy and how Ankara is dealing with the Gulf crisis.

We hope you enjoy this supplemental issue of Strategic Vision as much as we enjoyed putting it together, and that you will join us in wishing a fond farewell to 2018 and looking forward to another great year in 2019.

Dr. Fu-Kuo Liu Editor

Strategic Vision

4 Strategic Vision The Middle East

photo: Jovi Prevot

The sun rises above an M2A3 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle during Exercise Eastern Action 2019 at Al-Ghalail Range in Qatar, Nov. 11, 2018.

Managing Crisis

by J. Richard Hu

Since 5 June, 2017, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the UAE, and Egypt have severed diplomatic ties with Qatar. Then, on 22 June, 2017, these four countries presented 13 specific demands to Qatar and took hostile measures such as closing their airspace to Qatari aircraft, despite Qatar being a fellow member of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Qatar has encountered a variety of hard hits from immediate food supply shortage, to diplomatic isolation, and even a potential foreign military invasion.

Qatar has been told by those boycotting countries that it needs to accept six broad principles as a precondition to restart the negotiation process. Although this major crisis in Qatar’s history has no end in sight, and an immediate diplomatic and economic block-

ade and military coercion are highly provocative, a willingness for discussion and compromise, at least rhetorically, has been uttered by boycotters from the very beginning.

Leaders in Qatar have criticized and refused to comply with the sweeping 13-point list and six principles given by those four countries because of their ruthless disregard for Qatar’s sovereignty and feelings. Some of those asserted demands and principles are enumerated below.

Qatar must reduce diplomatic ties with Iran, close Iranian diplomatic missions in Qatar, expel members of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and disrupt military and intelligence cooperation with Iran. Trade with Iran must respect US and international

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 5

Comprehensive measures are needed to solve Gulf crisis

sanctions in a way that does not jeopardize the security of the Gulf Cooperation Council, they demand. Moreover, they call for the immediate closure of the Turkish military base which is currently under construction, and the cessation of military cooperation with Turkey inside Qatar.

Disavow terrorists

Another issue is the demand that Qatar weaken ties with all terrorist, sectarian and ideological organizations, in particular the Muslim Brotherhood, Daesh, al-Qaeda, Fateh al-Sham and Lebanon’s Hezbollah, and formally declare these entities to be terrorist organizations. Moreover, Qatar must close Al Jazeera television and its affiliated posts.

Qatar must stop all funding for people, groups, or organizations that have been designated as terrorist

groups by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Bahrain, the United States, and other countries.

Qatar must establish compensation payments for loss of life and other financial losses caused by Qatar’s policies in recent years, and Qatar’s military, social, and economic policies must be aligned with those of the other Gulf and Arab states.

Qatar must accept all requests within 10 days of sending the list to Qatar or the list will become invalid. Moreover, approval of monthly compliance audits must be made in the first year after they have agreed upon the requirements, followed by quarterly audits in the second year and annual audits over the next 10 years.

It has been more than one year since the beginning of the GCC-Qatar issue. Apparently, as there is no sign of easing and lifting the current embargo, the

6 Strategic Vision The Middle East

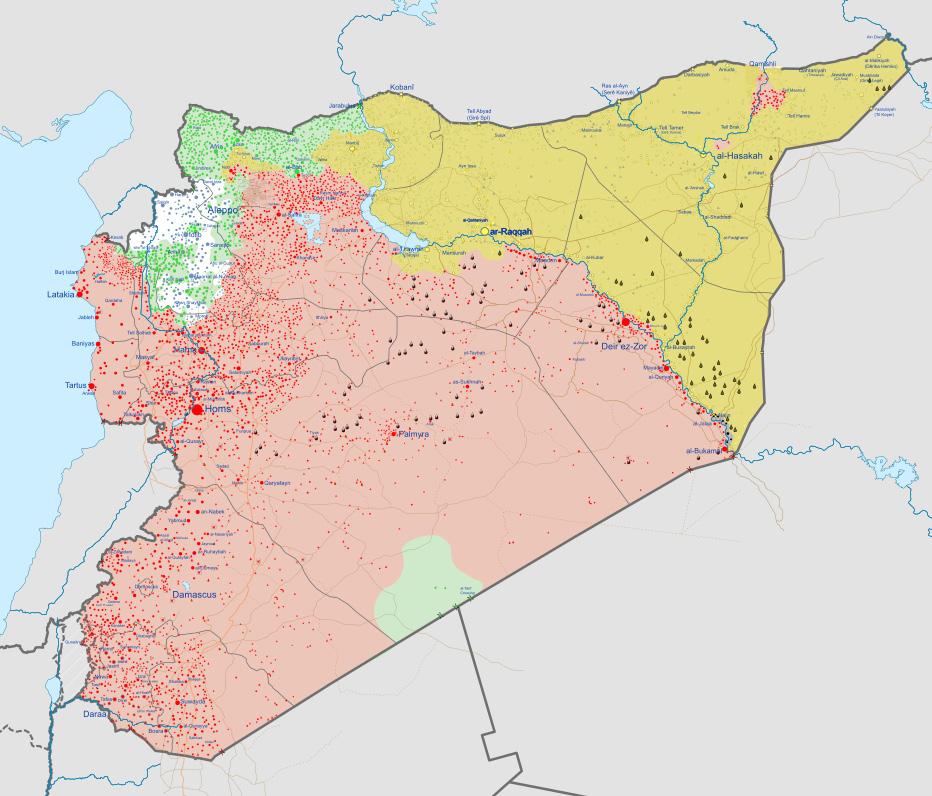

image: CIA.gov

situation is expected to continue to evolve for an extended period of time. This will proportionately inflict a new stage of potentially more severe business losses, economic setbacks, and social and political ramifications domestically on Qatar. As reconciliation endeavors have mainly been thwarted by reciprocal antagonisms, Qatar will still need to boost consensus and unity among its 2.7 million people. Essentially, Qatar, with its still rich resources, could put a more proactive effort into winning positive support both domestically and internationally. Four of those measures are discussed below.

As recommended and illuminated by Sun Tzu in his masterpiece “The Art of War,” “if you know your enemies and know yourself, you will not be imperiled in a hundred battles.” Therefore, comprehensive and effective intelligence is one of the most fundamental elements to guaranteeing foreign-policy decision making and implementation that is pragmatic and successful. Given all the security threats and challenges, including the worst-case scenario of a potential military invasion, from its powerful neighbors, Qatar needs to pragmatically assess past performance and deftly adapt to situations and contexts to

obtain advantages in managing interplays with its rivals and in preparing useful countermeasures. Since Saudi Arabia is the initiator and takes the lead in diplomatic spats with Qatar, Riyadh’s moves and sophisticated nuances are the central focus in terms of intelligence operations. Still, effective national security reactions will essentially be based on sound intelligence.

Secondly, Doha must ensure the presence of foreign troops in Qatar, as they are essential to fending off internal coups and foreign invasions. Qatar cur-

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 7

A Qatari soldier during sniper training as part of Exercise Eastern Action 19 on Nov. 6, 2018.

photo: Jovi Prevot

rently hosts around 11,000 US troops, yet still enjoys a military cooperation pact with Iran. This has spurred hostilities between Qatar and the boycotters. The presence of the Qatari military and foreign troops operating together could aid in the formation of steadfast alliances to deter a potential foreign assault or a domestic revolt. Military and security strength are critical in boosting Qatar’s international negotiation clout and internal political stability. Moreover, through the current construction of a Turkish military base, Qatar could also bring in foreign troops to safeguard Qatari defense.

Third, Doha must promote strategic communication and reinforce the power of narrative. As Harvard Professor Joseph Nye has well remarked, “success depends not only on whose army wins, but also on whose story wins.” The importance of strategic communication and political warfare both internally and externally has increased in dealing with interstate and

intrastate conflicts. To a certain extent, strategic communication, political warfare, and Beijing’s concept of Three Warfares have been employed in dealing with international affairs in a variety of confrontations such as the South China Sea disputes by countries like Vietnam, the Philippines, the United States, and China. Concerning the Gulf diplomatic rift, winning support domestically and internationally will have a tremendous impact on whether Qatar can sustain accusations, challenges, threats of most kinds, and eventually alleviate and solve the dispute.

Effective strategic communication and political warfare also aim at winning the hearts and minds

photo: Joshua Strang

8 Strategic Vision The Middle East

“While Qatar is unlikely to retreat from its ambitious foreign policy, it still needs to further clarify Doha’s intentions.”

The Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) at Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar, provides command and control of air power in 17 nations in the region.

of key decision makers and the majority of people in boycotting countries. In so doing, these forms of warfare, empowered by new tools and techniques of this information age, could be conducted through traditional and non-traditional ways. Traditional ways include passing messages on to targeted audiences via media reports, official news releases, academic conferences, and diplomatic talks.

Non-traditional paths encompass sending messages to selected receivers through social media, websites, and other means of communication, especially those in the cyber domain. In the new era of competition and conflict, strategic communication should first avoid information fratricide: In other words, if you can’t walk the walk, don’t talk the talk. In most cases, the best communication channel usually goes through an indirect approach. Moreover, both theoretically and experimentally, preferred channels for conveying those messages often are third parties such as perhaps Kuwaiti ministers, Jordanian scholars, German journalists, or American businessmen.

Finally, Qatar must transform its image. The crisis shows that Qatar has been asked by its neighbors to soothe the spat, and that Qatar is being pressured into accepting the six broad principles on combating extremism and terrorism. There are actually two key problems at issue which have exacerbated them greatly in recent years. One key issue is Qatar’s support for Islamic extremist

groups. The other is Qatar’s relations with Iran, and this Shia powerhouse is Sunni-ruled Saudi Arabia’s primary regional rival.

Qatar has refused to accept the two demands mentioned above largely because those measures threaten its independent sovereignty. However, while Qatar is unlikely to retreat from its ambitious foreign policy, it still needs to further clarify Doha’s intentions and hopefully transform its national image. From an international and conflict-resolution perspective, Qatar could bridge the gap and act as an important mediator in regional conflicts. It could clearly show that aiding extremist groups linked to al-Qaeda or the Islamic State was, and will continue to be, excluded from Doha’s policies, and simultaneously stress that hosting Islamist delegations such as al-Qaeda is based on good will, to avoid the escalation of regional conflict.

In a similar vein, moderate engagements with Teheran might be critical in cooling down the heat of confrontation between Sunni and Shia Muslims. With no usable communication and conciliation channel between rivals, there is the danger that disputes will become worse, which could spell disaster. b

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 9

photo: Paul Farley

About the author

J. Richard Hu is a retired ROC Army major general and a professor of strategy at the ROC National Defense University.

A Qatar Emiri Air Force Dassault Mirage 2000-5 fighter jet takes off as part of a Joint Task Force Odyssey Dawn mission 2011.

Fundamental Shifts

By Nayef bin Nahar

Gulf Crisis impacts security transitions, holding consequences for Qatar

This paper briefs on the most important security transitions caused by the Gulf crisis and its implications. The paper suggests that there are three fundamental shifts with significant effects on the Gulf security scene: the shift in the security sphere, the shift in the security standards and the shift in the security balance. The shift in security sphere is the transition from regional security to national security. The shift in the security standard is the transition from the customary standard to the legal standard. The shift in the security balance is the transition from the state of dominance represented by Saudi Arabia to competitive situation after the entry of Turkey to the Gulf region. The paper concludes with a reflection on one of the implications of these transformations, which is on the geopolitical weight

of the Gulf States and the balance of power.

In terms of the shift in the security sphere, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) came in to existence in the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq war with an aim to create a regional security system that would stand in the face of emerging threats, especially the Iranian challenge. Following the Iran-Iraq war, a new security threat to the GCC countries emerged, namely the Iraqi invasion and the transformation of Iraq from the circle of allies into a circle of enemies and direct threat. This was followed by the threat from armed groups starting with al-Qaeda and then Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

These security threats were caused by an external source, that is, outside the GCC system. The transfer of the threat from an external source to an internal

10 Strategic Vision The Middle East

source caused a radical shift in the security range, bringing down the security scale from the regional level to the national level. Now, the security determinants of the Gulf States are no longer regional, but rather purely national. A threat to a Gulf state may no longer be classified as a threat according to the determinants of another Gulf state. Thus, each country develops its own security vision in isolation from the security threats of other countries. Qatar, for example, doesn’t have a security vision that is harmonized with a regional security vision, but rather it has its own independent vision, because, the security of Qatar cannot be ensured within a larger vision, and an independent vision was needed for this.

This collapse in the concept of regional security of the Gulf region, and the scaling down of security concerns to the national level, forced the Gulf States to redefine the national security constituents for each country, focusing on three determinants: Threats (re-

lated to the potential for military escalation), Risks (the prospects that may lead to harm to the state in general), and Challenges.

A unified framework

These three determinants changed radically with the Gulf crisis, firmly establishing the idea of national security at the expense of a unified vision of regional security. The unified vision of regional security is not meant to have an absolute parity among the countries in the security perception, but rather it means a unified framework in which the conceptual differences between the Gulf States may be are melted.

In terms of the shift in the security standard, at a lecture at the Ibn Khaldun Center for Human and Social Sciences in Qatar University, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of State for Defense H.E. Dr. Khalid Al-Attiyah said that any kind of restoration

photo: Jimmy Baikovicius

photo: Jimmy Baikovicius

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 11

of Gulf relations must be made in accordance with new standards and rules. The rules upon which relations were previously based are no longer valid for the establishment of a new Gulf cooperation. The rules in effect before the Gulf crisis were fundamentally based on the influence of Saudi Arabia, wherein Saudi dominance determined regional security perceptions and concepts to a great extent. This was reflected in Syrian issue where Qatar allowed Saudi Arabia to define the parameters within which Gulf states dealt with the Syrian opposition. The Gulf countries also agreed with the Saudi appreciation of the security threat in the Yemeni context and in the military action taken to handle it.

Today, after the Gulf crisis, the great consideration on which Qatar had woven its security cooperation with Saudi Arabia has faded away. The disintegration of mutual trust made it necessary to find an alternative basis for the establishment of mutual cooperation among the Gulf countries, especially between Qatar and its adversaries, according to the Deputy Prime Minister. Those new rules are based on two

fundamental pillars: Non-compliance with what is not a legal obligation; and the adoption of bilateral alliances as a parallel line.

New methodology

The first rule is to abandon the previous methodology of categorizing the threats, risks and security challenges according to the Saudi classification, and to give up all the security consensus arising from the previous moral evaluations of the status of Saudi Arabia, in addition to limiting to a minimum what Qatar needs to do as part of a regional security system that has entitlements in excess of national security entitlements. The second rule reflects the state of loss of confidence that culminated in the aftermath of Gulf crisis because of its comprehensive consequences reaching to all areas replacing the feeling of fraternity with hostility.

In terms of the shift in the security balance from dominance to competition, one of the peculiarities of the Gulf system is that it does have a balance among

12 Strategic Vision The Middle East

US Defense Secretary Jim Mattis meets with Saudi Arabia’s King Salman Bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud in Riyadh April 19, 2017.

photo: Brigitte Brantley

its members. It is not based on cooperation among states which are neither equal nor even convergent in terms of capabilities and geopolitical weight. The reason for the absence of a minimum balance among the Gulf States goes exclusively to the existence of Saudi Arabia within this system, since it possesses the stable geopolitical capabilities far more than all the other Gulf countries.

US and Saudi Arabian military personnel conduct a practice air assault during Exercise Friendship and Iron Hawk near Tabuk, Saudi Arabia.

The mutuality among the Gulf States is based on hegemony rather than on sheer cooperation. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is about 100 times larger in size than Qatar, two thousand times larger than Bahrain, and six times larger than the Sultanate of Oman. In terms of population, Saudi Arabia exceeds Qatar by about thirty seven times. There was no balance in the Gulf security equation, but rather, there was a clear dominance of Saudi Arabia over the region. However, after the Gulf crisis, Qatari-Saudi relations devolved into outright hostility.

Thus, the Gulf crisis brought about a substantial change in the security equation, by paving way to the direct presence of the Turkish military in the Gulf territories. This presence led directly to changing the role of Saudi from the dominant actor to a competitor, and the competition naturally tends to be in favor of the Turkish side.

Qatar has resorted to another way of achieving a

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 13

photo: ROC Navy

photo: Harley Jelis

balance of power, as per international custom, through one or both of the following methods: self-building and joint building.

Self-building suggests that the state should build a military power parallel to its adversaries, without just relying on coalitions for its security. This model didn’t look impressive for Qatar before the crisis and the withdrawal of ambassadors in 2014, but then it was found that Qatar needs to achieve security self-sufficiency, considering the indicators that predict the possibility of non-integration of the Gulf countries for a collective security.

Joint building can be adopted when the state is unable to achieve a balance of power with its adversary on its own. Then it has to seek the support of other countries to form an alliance. The method of joint military building was the only model that the State of Qatar has explicitly adopted since 1996, it is because of the geopolitical power imbalance between Qatar

and its neighbors, in addition to the fact that joint building is less expensive, more flexible and responsive to variables. However, after the Gulf crisis, the situation became different. Although Qatar continued with the method of joint building, at an increased pace and scale, it realized this method could not be adopted as a single option like before, but, rather, as a parallel option to self-building. b

14 Strategic Vision The Middle East

About the author

Dr. Nayef bin Nahar is a political science researcher at the Ibn Khaldun Center for Human and Social Sciences at Qatar University.

photo: James Larimer

A Qatari soldier receives sniper training from a US Soldier in Um Hattah on November 6, 2018, Qatar as part of Exercise Eastern Action 19.

photo: Phil Speck

The Qatari Emiri Air Force Family Cultural Exchange at Al Udeid Air Base is a partnership-building event.

The Gulf Crisis and Media Space

This policy brief presents an analysis of the media campaign by the blockading countries against the State of Qatar in the Gulf Crisis. The countries consist of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt. The media has proven to be highly efficient in molding public opinion, and here we discuss how the media’s propaganda tactics have been used to manipulate public perception and behavior.

By Osama Kubbar & Rashid Al Naimi

Media space and practices are a reflection of the principles, social values and political system in a country, since the exchanged and broadcasted Information and views represent a form of political practices that affect the spheres of life in societies and countries. Such exchange of information shapes internal and external public opinion, and therefore, it must be dealt with as a form of political practice and influence that shapes beliefs, behaviors, and engagements.

One of the most important elements of responsible media is objectivity in handling news based on facts and clear evidence, without any manipulation or exaggeration. Traditionally, media outlets broadcast information in a professional manner through a network of journalists, editorial committees and audit committees, which adhere to professional rules and ethics in accordance with legal frameworks governing the profession.

Today’s news media has changed the framework of traditional media practice, since media space is becoming an open space for everyone to broadcast and exchange information freely with their own editorial comment. The technological revolution has caused a great deal of change in the traditional concept of media. It has broken the traditional monopoly of media ownership by ruling regimes and people in power, photo:

Walter Wayman

and has paved the way for the public to practice the free sharing of information. Hence, journalism is becoming a public practice.

Digital media and cyberspace have opened up a new horizon that is full of opportunities and challenges for the media profession, such that it is no longer acceptable to talk about professional ethics or legal framework. Such a new media space is becoming heavily mixed between the professional and the hobbyist; between regulation and a free press; and between old media and today’s citizen journalists. Today, there are more than three billion Internet users, who have the chance to practice information broadcasting, and influence the public in this information society.

Public utility

Since the birth of television in the early 1920s, major countries realized the importance of the media and the public sphere. The English government has considered the media to be a public utility and the government must control it for the public interest, as did United States.

In the later stages to the West, the political leaders of the Gulf States realized the importance of the media. In 1996, the state of Qatar established the AlJazeera TV Channel, then Saudi Arabia and the UAE established Arabia and MBC TV channels. Then,

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 15

many other TV stations followed, such as France 24, Al-Hadath, and others. All these TV channels have contributed to influencing the ways of thinking in the region, and reshaping it in accordance with a specific agenda. In today’s world, media outlets are tied to sponsors, and therefore they are always operating to serve and propagate a specific agenda. As a result, people in the region are becoming very much polarized and divided among the different views.

The regional media coverage and digital media handling of the Gulf Crisis, especially of those involved countries, have demonstrated the extent to which media Space has become important, and it has been the forefront of the real battlefield.

The strong link between politics and the media comes from the fact that communication—a more comprehensive term than the term media—is a basic activity for all human beings. Most of what we do in our daily lives is different manifestations of what we mean by communication.

Political communication is defined as the means and intentions of the messenger to influence the political environment. The critical factor that makes a public communication

“Political” is not the source of the message but its content and purpose.

As such, communication, political activities, and systems of governance form a power triangle, wherein they blend together with equal importance.

Regardless of whether a political system is democratic or totalitarian, the messages that are broadcast represent the messages that the regime is emphasizing and propagating. In all cases, communication helps the regime to shape the country in accordance with its agenda, and establish the control it deems required.

Monitoring authority

One might say that the media has become the most powerful entity on earth over the last ten years. It makes everyone aware of all activities around them; social, political and economic. In fact, media space is becoming akin to a monitoring authority, overseeing the performance of all, and making the public aware of all details. It is like a mirror which exposes the bare truth and harsh realities. Therefore, the media plays an imperative role in the welfare of society.

The growing use of the Internet and related digital technologies has creating a space for individ -

16 Strategic Vision The Middle East

A controlled detonation is conducted Nov. 27, 2018, at Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar.

photo: Christopher Hubenthal

photo: Pepe Pont

uals to network in ways that enable a new source of accountability in government, politics, and other sectors. With no accountability, no professional editing, or any ethical basis, it is becoming a dangerous realm, where nothing can stay secret or hidden from the public.

Maria Konnikova in “The Confidence Game” discusses how people can be conned by the flood of information that the brain cannot handle or process, and this is how the masses may be deceived or lured into believing in something.

The Pew Research Center has conducted research on how much the masses rely on the Internet to get their information and news, and concluded that 50 percent of the world’s population get

their news from the Internet, whereas it is 60 percent in the United States. These numbers are expected to increase in the next few years.

media penetration

The media played a pivotal role in the Gulf crisis and the siege of Qatar. Perhaps this is the first precedent in modern history in which the media is the main focus in a severe political crisis between neighboring countries. The Gulf crisis began with a media penetration into Qatar News Agency and continues to interact with the media through official media platforms as well as digital and social platforms.

From the very beginning, the besieged countries focused on shifting the dispute from the circle of political disagreement

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 17

image: Brian

A US Army Specialist edits an illustration at the Military Information Support Task Force-Central (MISTF-C) on Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar as part of a joint team tasked with countering propaganda narratives disseminated by Daesh.

between the leaders and the regimes to a wider and more comprehensive circle that included intellectual, cultural, social and religious differences. The countries involved in the siege have employed the media with all its tools, especially the digital media, to engage the peoples of the Gulf in the political conflict between the regimes. They have expanded the circle of political disagreement and moved it to the street. This has exacerbated the crisis.

Intellectual cover

In order to influence regional and international public opinion, the countries engaged in the blockade have been active in holding conferences and seminars and assisting international academic institutions to discuss the dispute in an attempt to give intellectual cover and bolster the legitimacy of their demands. There has been much discussion about the media campaign launched by the blockading countries against the state of Qatar. General opinion holds that they lacked a firm strategy, and their media methods are characterized by chaos, confusion, and lack of

direction, with minimal credibility and consistency. Such a media campaign has created confusion among the general public.

Since the beginning of the crisis, the blockading countries have not provided any convincing evidence to support their accusations that the state of Qatar is a sponsor of terrorism, despite the strong media campaign. Initially, they provided minimal information for the public to feed on and understand. The lack of official statements has instigated many journalists and independent experts to jump in with their own theories and explanations as to the reasons, tying them to historical differences, economic competition, and differences in foreign policies.

This has caused flood of information in the media space that was difficult for ordinary people to digest, analyze, and form their own opinions. As a result,

18 Strategic Vision The Middle East

“TheGulfCrisishasseenastrong media campaign from Saudi Arabia,theUAEandEgyptagainst the state of Qatar.”

Qataris celebrate their National Day with a 52km camel ride to commemorate traditional Qatar messengers.

photo: Peter Dowley

they started to accept the opinion of others without further examination.

The blockading countries’ media campaign follows a pattern that is known as propaganda, which was discussed by many scholars, most famously by Noam Chomsky, who discussed the impact of propaganda, and how it engineers opinion through false information being tactically projected as a representation of reality, ultimately leading to the post-truth era in which we now live.

A close examination of their tactics reveals trends of several key strategies, including a distraction strategy; a strategy of creating a problem then offering a solution; the gradual strategy; and the deferring strategy. In addition to these, other common strategies involve appeals to emotion, and keeping the public ignorant.

The six strategies listed above have been used extensively by the blockading countries against Qatar in their propaganda campaigns. All the views and discussions about a lack of coherence or strategy in the blockading countries’ media effort is nonsense.

The Gulf Crisis has seen a strong media campaign from Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt against the state of Qatar, with the objective of demonizing Qatar and characterizing it as a host and supporter of terrorism.

The authors conclude that the media campaign follows the propaganda model, with consistently employs different strategies and tactics for the manipulation of the truth, and creating a false perception, in the aid of managing a change in behavior. Eventually, it creates what is called a post-truth reality, which is a space largely framed by appeals to emotion, disconnected from facts and truth. b

About the authors

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 19

photo: Chris Stone

US Marines conduct a parachute operation during Exercise Eagle Resolve over Qatar.

Dr. Osama Kubbar is an international relations expert and strategic analyst at the Qatar Armed Forces Strategic Studies Centre. He is a politician and political analyst, and can be reached at okabbar@yahoo.com.

Dr. Rashid Al Naimi is a brigadier general in the Qatar Armed Forces and holds a PhD in political science. He is the director of International Studies at the Qatar Armed Forces Strategic Studies Centre.

It was reported 3 December, 2018, that Prime Minister Necherivan Barzani was in the running to take over as president of the Kurdistan Regional Government. Barzani is the nephew of the previous president, Massoud Barzani, who stepped down in the wake of a controversial referendum last year, though by all accounts the elder Barzani has continued to exercise power, albeit from behind the scenes. In addition to putting forward the nomination of Necherivan for the post of president, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) is eyeing Masoud Barzani’s son, Masrour—currently chancellor of the Kurdish Security Council—to take over the premiership. The move illustrates the power that the Barzani clan wields over the KDP and, by

Kurdish Family Values

by Dean Karalekas

20 Strategic Vision The Middle East

Next generation of Barzani family set to take reins of power in Erbil

photo: Dean Karalekas

extension, Iraqi Kurdistan. It also may offer a hint as to what plans the Barzani family have in mind for their consolidation of power in Erbil, and for its relations with Baghdad.

Given the fact that the KDP is the largest in the Kurdistan Regional Government—winning 45 seats, 11 shy of an absolute majority, in the parliamentary elections that concluded in September—there is little chance that these nominations will fail to find approval. While such a transfer of power to the next generation of Barzani family members may smack of nepotism and the kind of hereditary regime the likes

of which North Korea is continually excoriated for perpetuating, both men have earned their reputations for diplomacy and dedication to furthering the cause of the Kurdistani state.

Masrour, 49, joined the Peshmerga at the age of 16 and fought in the 1991 uprising against Saddam Hussein. More recently he has been playing a prominent, strategic role in

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 21

the fight against ISIS, primarily in his capacity as head of the Kurdish military intelligence and security apparatus. Nechirvan, 52, took part in the 2003 US invasion of Iraq and helped build the post-Saddam economy of Kurdistan into Iraq’s most successful regional economy, serving as premier from 1999 to 2012. Both men have been lauded for their diplomatic skills, and their nomination is widely seen as a source of stability and continuity, rather than the consolidation of a family dynasty, although this latter aspect is undoubtedly a factor.

The Barzani family’s influence in the region goes back at least a century, to the very beginnings of the fight for a political Kurdish state. Though many Kurds trace their heritage back millennia, the modern Kurdish identity, or Kurdayeti, is heavily influenced by the nation-building that took place following the fall of the Persian and Ottoman empires and the division of the region into nation states roughly delineated along ethnic lines. While the Arabs, Persians, and Turks obtained their own nations following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the geopolitical gerrymandering that ensued after World War I, the Kurds did not. Today their territory is divided by the borders separating Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria.

The head of the Barzani tribe in Northern Iraq in the 1920s and 1930s, Sheikh Ahmed Barzani, led the

22 Strategic Vision The Middle East

A mural commemorating the Pershmerga.

A Yazidi man in Laliş poses for a photograph with his bird of prey.

photo: Dean Karalekas

photo: Dean Karalekas

struggle to build a Kurdish nation following World War I. He consolidated a number of local tribes and expanded the territory of Barzan in his fight against the Iraqi government of the day. In this capacity, he put his stamp on the character of Kurdayeti through his teachings and actions. In addition to preaching advocacy for Kurdish nationalism, Sheikh Ahmed— who converted to Christianity in the early 1930s—is remembered as a leader who taught the virtues of education, tolerance, and equality, as well as advocating that wealth be shared communally. His rule in Kurdistan is characterized by policies that included elements of what today we would call social reform and environmental protection.

Defining Kurdish values

“If I owned the entire world, I would give it all up to stop the unjust spilling of blood of a single human being,” Sheikh Ahmed is reported to have said, in a quote that sums up his philosophy. Indeed, the defining values of Kurdish society today are largely in alignment with the values and practices nor-

mally associated with Western notions of Classical Liberalism.

In the words of Arif Qurbany, a writer from Kirkuk, the Kurdish nation “has been well ahead of the Turkish and Arab nations in terms of society, cus-

toms, behavior, respect for human values, equality and tolerance of other religions.” This is evidenced by Erbil’s banning of forced marriages and female genital mutilation, restrictions placed on polygamy, and amendments made to the Iraqi Personal Status Law that resulted in a marked decline in honor killings.

According to a report in The Hill, the Kurdistan Regional Government has been largely successful in its efforts to protect members of the nation’s Christian, Jewish and Yazidi minorities from persecution—groups that widely suffer from ethnic-based vi-

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 23

Residents of Iraqi Kurdistan go about their daily chores.

“Sheikh Ahmed—who converted to Christianity in the early 1930s—is remembered as a leader who taught thevirtuesofeducation,tolerance,and equality.”

photo: Dean Karalekas

olence elsewhere in Iraq, and throughout the Middle East. More recently, speaking on the periphery of an event to mark the International Day for Eliminating Violence Against Women, the Head of the European Union’s Liaison Office in Erbil, Clarisse Pásztory, remarked on 25 November, 2018, that Iraqi Kurdistan “has a great reputation of inclusivity” in all aspects of society, ranging from ethnicity to religion. There is little doubt that these cultural values find their roots in the teachings of Sheikh Ahmed. And yet when most analyses of the Barzani fam-

ily’s hold over Iraqi Kurdistan’s political scene trace the roots of the family’s influence, they begin with Sheikh Ahmed’s younger brother, Mustafa Barzani, father of Massoud Barzani and grandfather of Prime Minister Necherivan Barzani. Mullah Mustafa, as he was known, succeeded Sheikh Ahmed in the 1930s as leader of the struggle for Kurdish nationhood and, shortly after World War II, emerged as the head of the armed forces of the Kurdish Mahabad Republic, which was largely propped up with the aid of the Soviet Union as well as forces in northwestern Iran.

24 Strategic Vision The Middle East

In the mid 1990s, a bloody, four-year civil war split the vast area of Iraqi Kurdistan into two separate administrative regions.

More relevant is his role as founder of the KDP in 1946, which to this day remains the most powerful and influential political organization in Iraqi Kurdistan.

With Mullah Mustafa’s death in 1979, leadership of the KDP fell to his son Masoud who, as it happens, was born on the very day his father founded the party, lending a sheen of manifest destiny to the intra-family power transfer. Indeed, he is often photographed wearing traditional Kurdish dress and a keffiyeh. Barzani continued the fight against Saddam

Hussein’s Baathist regime while in exile in Iran, and in 1992, with Saddam’s control over the country weakened by the US-led war to liberate Kuwait, he helped form the Kurdistan Regional Government. That year, the fledgling country held its first democratic elections, in which Barzani’s KDP and Jelal Talabani’s Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) each earned 50 seats in the first Kurdish parliament. The two hammered out a compromise and agreed to a powersharing agreement. This commitment to compromise was unexpected given the antagonistic relationship

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 25

photo: Dean Karalekas

between the two parties, and between the two men.

In the mid 1990s, after a bloody, four-year civil war, the fledgling nation was divided into two separate administrative regions: one based in Erbil and led by Barzani; the other operating out of Sulaymaniyah and led by Talabani. The two eventually reconciled in 2002 when Talabani became president of Iraq after the ouster of Saddam Hussein. Barzani was made president of the newly united Iraqi Kurdistan, and assumed the new role of statesman.

Barzani’s tenure as president lasted 12 years, until he stepped down last year to smooth relations after the diplomatic and military fallout of a disastrous referendum on Kurdish independence. A pyrrhic victory, nearly 93 percent of voters cast their ballots in favor of Kurdish secession from Iraq, spurring Baghdad to shut down Kurdistan’s borders and airports and deploy the Iraqi army to retake oil-rich Kirkuk.

By removing himself from office voluntarily, Barzani

may have been placating the powers in Baghdad, as well as Washington and Istanbul, who are apprehensive about the idea of a de jure independent Kurdistan. By passing power on to the younger generation of Barzanis, however, Masoud will doubtless continue to have a hand in how the state is run. Nevertheless, his retirement has been hailed as historic, given that this is a region in which most leaders cling to power until they are assassinated, removed by coup, or otherwise die in office.

Paving the way

In order to pave the way for handing over the reins of power to the younger generation of Barzanis, Massoud made a high-profile visit to Baghdad 22 November in which he met with Iraq’s new Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi, as well as a side trip to Najaf to sit down with Muqtada alSadr, leader of Saraya alSalam, a Shia militia. This visit represents the first time in a year that the elder Barzani has reached out to federal authorities and power holders to put an end to the enmity that ensued after the aforementioned referendum. The issues discussed on this visit may well offer a hint as to what policies will be addressed following the installation of Necherivan and Masrour Barzani.

26 Strategic Vision The Middle East

photo: Dean Karalekas

A man relaxes in a mosque in Amadiya.

A sign warns of mines.

photo: Dean Karalekas

It was speculated by KDP leader Muhsin al-Sadoun, for example, that Massoud’s tête-à-tête with Sadr focused on the re-opening of long-stalled negotiations on forming the government, and boosting the role of the political party in such talks.

Other goals of the Kurdistan region include securing an equal share of the government and forging a consensus between both sides before any decisions are made. Specifically, Barzani is seeking to raise Kurdistan’s share of Iraq’s general budget to 17 percent, up from the current level of 14 percent, as well as the withdrawal of federal forces from Kirkuk so that the Peshmerga can return. Analysts remain doubtful that these goals can be met, notwithstanding the implicit threat behind these requests being that Erbil could well follow through on implementing the outcome of the plebiscite, citing the will of the people.

According to Rachel Avraham, president of the Dona Gracia Mendes Nasi Center for Human Rights in Middle East, there is yet cause for cautious optimism. Writing in The Washington Times 6 November, 2018, Ms. Avraham opined that the time might be ripe to build a better Iraq now that the country has a new, moderate prime minister in Mahdi, who boats good relations with the Sunnis, Shias as well as Kurdistan.

Certainly now that the younger Barzanis will be pulling the levers of power there is the sense that a new generation can move forward and leave behind the enmities of the former. Still, one wonders what

Ahmed Barzani would make of the political dynasty being consolidated in Erbil this month. Sheikh Ahmed is known to have rejected the traditional method of guarding political power within the same family, advocating instead for a meritocracy and the appointment of leaders based on their qualifications. Time will tell how well tomorrow’s Kurdistan lives up to Sheikh Ahmed’s standards and values. b

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 27

About the author

Dr. Dean Karalekas is the associate editor of Strategic Vision and a scholar whose research focuses on civil-military relations and emergency management.

Sheikh Ahmed Barzani led the struggle to build a Kurdish nation following World War I. file photo

In recent years, non-state actors have risen to challenge more powerful nations, particularly in the Middle East, and state actors have sustained difficulties in defeating them on tactical, operational, and strategic levels. Since the last quarter of the twentieth century, there has been a steady rise in insurgent capacities. There has been a significant increase in insurgents’ victories over stronger incumbents, representing a change in historical patterns.

In 286 insurgencies between 1800 and 2005, incumbents were only victorious in 25 percent of them between 1976 and 2005. In contrast, incumbents won 90 percent of the victories between 1826 and 1850. Other scholars have shown similar outcomes and, overall, regardless of the dataset employed and the timeframe selected, the findings have been consistent. Armed non-state actors have been altering a historical trend: that state actors monopolize the means of violence and therefore are more capable of defeating non-state actors on the battlefield. The trend applies to very different types of armed non-state actors, from the FARC in Colombia to the Taliban in Afghanistan, and beyond.

Security, Military and Strategic Studies literature provides a wide range of explanations to why weaker

28 Strategic Vision The Middle East

photo: Krystal Garrett

The Middle East is Fertile Ground for Rise of Armed Non-State Actors

By Omar Ashour

By Omar Ashour

insurgents can beat or survive a stronger state-backed force. These explanations primarily focus on geography, population, external support, military tactics, and military strategy. Mao Zedong highlighted the centrality of the population’s loyalty for a successful insurgency by stating that an insurgent “must move amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea.”

Hearts and minds

The US Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual concludes that insurgencies represent a “contest for the loyalty” of a mostly uncommitted general public that could side with either the status-quo or non-status-quo, and that success requires

persuading this uncommitted public to side with the status-quo by “winning their hearts and minds.” Brutality by incumbents against the local population also affects their loyalty, and therefore can help insurgents in terms of recruitment, resources and legitimacy. General Stanley McChrystal, the former commander of US forces in Afghanistan, refers to this effect as “insurgent math.” For every innocent local the incumbents’ forces kill, McChrystal calculates, they create ten new insurgents.

The term “accidental guerrilla,” refers to the consequences of indiscriminate repression which leads elements of the local population to be drawn into fighting the incumbents. There are also alternative arguments, showing that the brutal use of state vio-

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 29

photo: Alibaba2k16

lence against civilians may help incumbents to defeat insurgents by alienating the locals.

Geographic explanations also help to explain insurgent success. Rough terrain is one of four critical variables in the success of an insurgency. Mao Zedong argued that guerrilla warfare is most feasible when employed in large countries where the incumbents’ forces tend to overstretch their lines of supply. Similarly, the tiny numbers of armed revolutionaries in Cuba manipulated the topography to outmaneuver much stronger forces and gradually move from the easternmost province of the island towards the capital in the west. Distance is also a key factor, as incumbent forces lose strength when the conflict moves deeper into hospitable territory.

State sponsorship

Another factor in insurgent success in foreign support. In a study of 89 insurgences, those with state sponsorship prevailed by a two-to-one ratio. Once foreign assistance stops, the success ratio of the insurgent side drops to one in four.

Finally, military tactics and strategy can be a huge

factor in insurgent success. Some studies argue that modern combat machinery has undermined incumbents’ ability to win over the civilian population, form ties with the locals, and gather valuable human intelligence. Other observers argue that insurgent access to new technologies in arms, communications, intelligence information, transportation, infrastructure, and organizational/administrative capacities has allowed them to enhance their military tactics to levels reserved historically for state-affiliated armed actors. This significantly reduces the likelihood of being defeated by incumbent forces.

Some elements of these explanations apply to organizations in the Middle East and North Africa,

including Daesh, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), alQaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), Ansar Allah (Houthis), and many others. The political environment in the Arabmajority Middle East certainly has its own particularities: A combination of arms and religion—or alternatively, arms and chauvinistic nationalism—in most of the Arab world has proved to be the most effective means to gaining, and remaining in, po-

30 Strategic Vision The Middle East

“Anylong-termsolutionmustreform the political environment thathasconsistentlyengendered violent radicalization for more than four decades.”

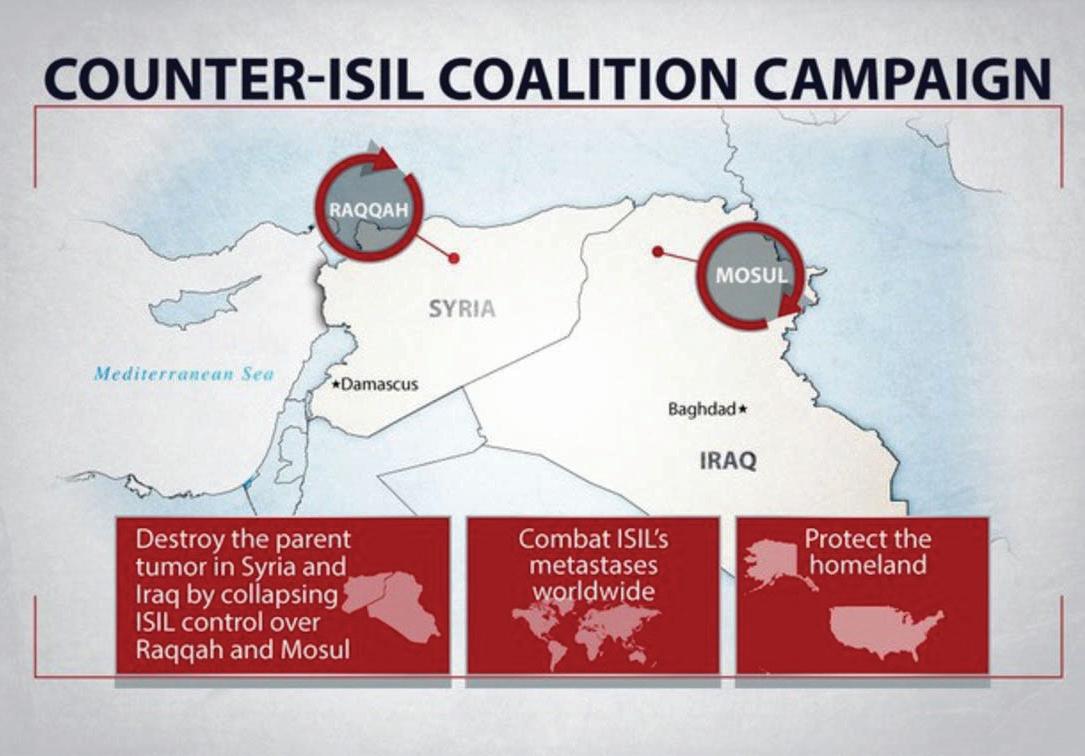

graphic: US Centcom

litical power. Votes, constitutions, good governance and socio-economic achievements are secondary and, in many Arab-majority countries, relegated to cosmetic matters.

Armed non-state actors can certainly endure and expand in a regional context where bullets are more effective than ballots; where extreme forms of political violence are committed by state and non-state actors alike, and then legitimated by religious institutions, and where the eradication of the “other” is perceived as a more legitimate political strategy than compromise and reconciliation. This is not to suggest that the region is inherently violent. However, dominant socio-political ruling elites in the Arab World, with few exceptions, consistently choose to conduct politics via violent methods, ranging from systematically torturing individuals to genocidal policies.

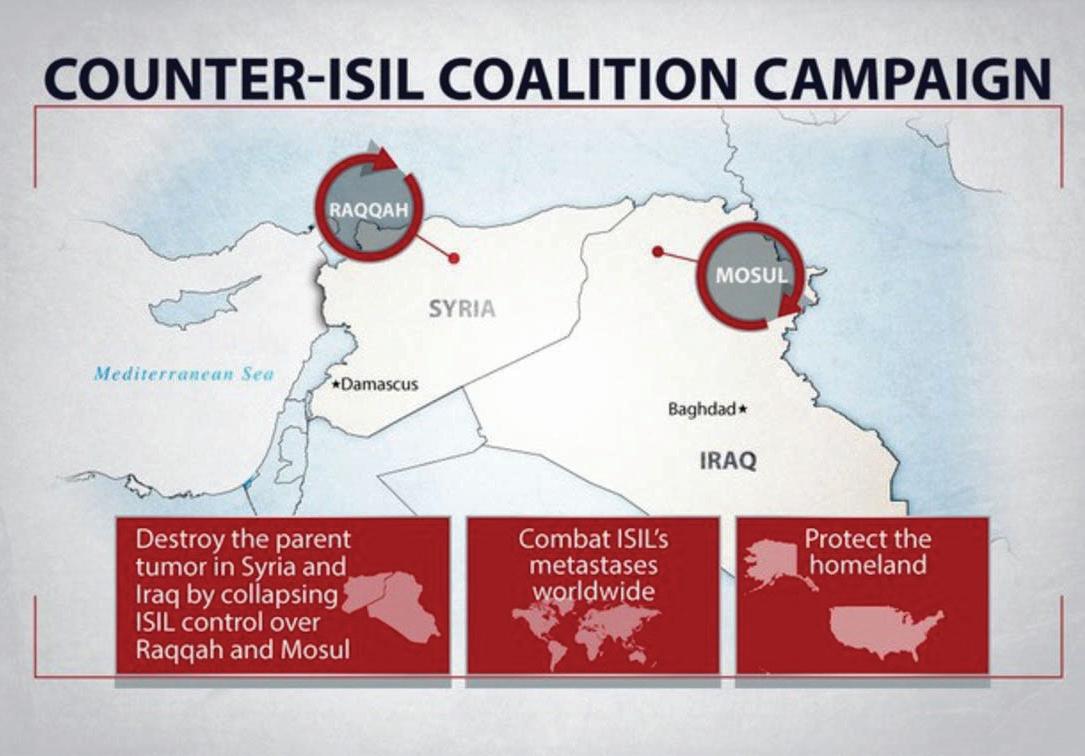

The United States and its allies have developed a strategy to confront armed non-state actors that threaten its

national and strategic security. Other states, including Russia and Iran, followed through with their own strategic modifications. An overview of some of the pillars of these strategies are outlined below.

The United States and its allies have employed air

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 31

photo: Antonio Lewis

Operation Inherent Resolve members have built baseline capacity of more than 130,000 Iraqi security forces trained to defeat ISIS within the Iraqi Security Forces.

strikes, including unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAVs – commonly known as “drones”), to degrade and contain non-state actors which threaten the United States, such as Daesh, al-Qaeda, and the Taliban. UCAVs are more tactical, not strategic. They are used to degrade, and not necessarily destroy. Another element of US strategy has been to arm and support local partners on the ground who attack and, eventually, destroy Daesh and other hostile non-

state actors. This is based on the decision by the Obama administration, as well as by the UK government and other NATO allies, that the United States must refrain from sending in ground troops.

Hence, the alternative is to build up the capacities of local partners. US strategy also acknowledges that Daesh is a symptom, not a cause, of the broken politics of the region. Therefore, any long-term solution must reform the political environment that has consistently engendered violent radicalization for more than four decades. Certainly, defeating Daesh militarily would only temporarily mask the deep structural problems at the source of its emergence, just

32 Strategic Vision The Middle East

Protesters and opposition parties march to Sana’a University during the 2011–2012 Yemeni revolution.

US Air Force F-15E Strike Eagles fly over northern Iraq after conducting airstrikes in Syria.

photo: Noor Al Hassan

photo: Matthew Bruch

photo: Beshr O

as the earlier defeat of the mother-organization, the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI), did in 2007-2008. Given that widespread levels of repression and corruption and a sense of frustration and alienation among Arab Sunnis, the emergence of a new expression of anger would be inevitable, and perhaps one worse than Daesh, which itself is more extreme than al-Qaeda.

Conflict and containment

The outcome of this strategy is not necessarily ideal. It is more likely to be the containment of Daesh, not necessarily the destruction of it, in the short term. Certainly, a failure to significantly boost local partners and find political solutions in Iraq and Syria would de facto lock the United States and NATO allies

into a long-term conflict and a containment strategy.

The strategy employed by American-led forces has had some positive impacts. Airstrikes and an air presence over Iraq and Syria have compelled Daesh to limit the use of conventional military tactics, and ultimately to lose control of significant territory. Airstrikes also provided some space and time for capacity-building efforts and, perhaps optimistically, for political solutions to be found.

It is important to realize that armed non-state actors in the region are a symptom, not a cause, of the deeply dysfunctional politics in the region, especially in Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, and the Gulf. Hence, the military defeat of Daesh will not be enough: A sustained political reform and reconciliation process will eventually be necessary.

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 33

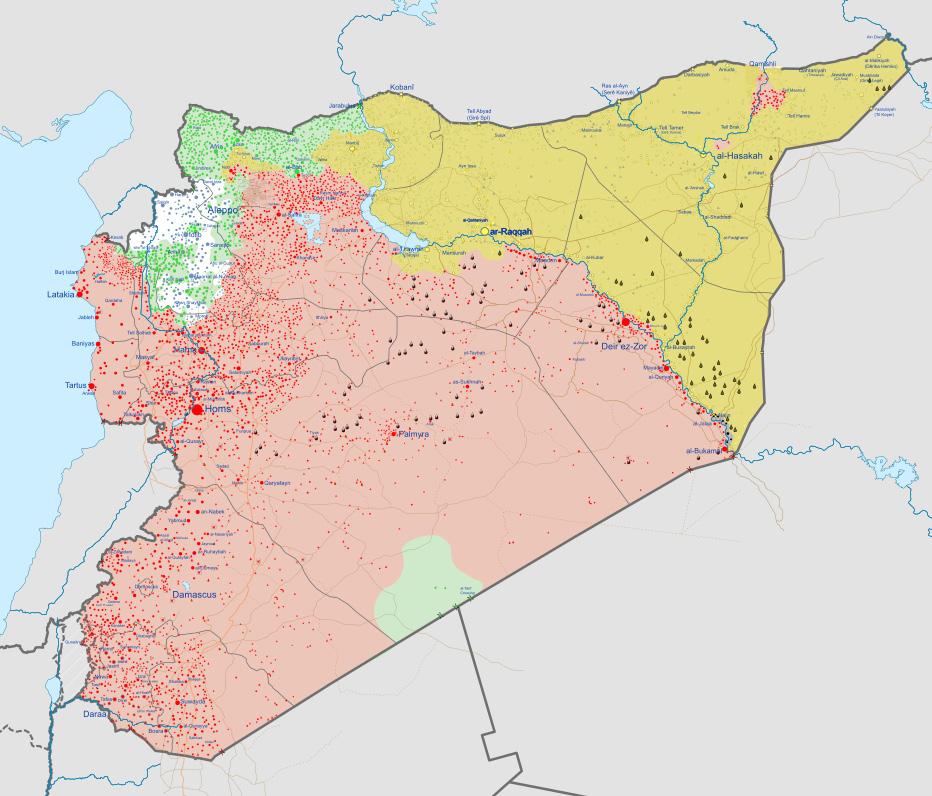

Map of the Syrian Civil War Ermanarich

Arab-majority uprisings have given scholars and practitioners several important lessons about how changes within the political environment can affect the rise or transformation of armed radical groups. Violent extremist rationale, which holds that political violence is the only significant method for socio-political change, was briefly undermined by successful civil resistance campaigns that brought down two dictatorships in Tunisia and Egypt in 2011. The brutal tactics of the Qaddafi and Assad regimes in dealing with protestors have shown the limits of civil resistance. These limits were also highlighted in Iraq during the April 2013 crackdowns by the al-Maliki government on Sunni-majority sit-ins, and in Egypt surrounding the July 2013 military coup.

In the context of partly democratic institutionalized transitions in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Iraq and Yemen (especially between 2011 and 2013), a few critical policy-relevant observations can be deduced regarding the political environ-

ment and the longterm strategic vision. First, formerly violent extremist organizations that transformed into non-violent political activism have notably stuck within their transformation between 2011 and 2013, when a fragile democratization process was still ongoing. Groups such as the Egyptian Islamic Group (IG) and the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, and factions and individuals from the Egyptian al-Jihad organization established political parties, competed in elections, participated in constitutional assemblies, and made significant political compromises to bolster transitions away from authoritarianism. For example, in 2011, the IG became a mainstream political party in Egypt that organized anti-sectarian violence rallies and issued joint statements for peaceful coexistence with the Coptic Church of Assyut (a southern city and an IG stronghold).

Another policy-relevant observation has to do with security sector reform (SSR). From previous research, de-radicalization and transition from violent to non-violent activism is less likely to be sustained unless there is a thorough process of reforming the security sector. The reform process should entail changing the standard operating procedures, training and education

34 Strategic Vision The Middle East

Sayyid Qutb was a leading member of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.

curricula, leadership and promotion criteria, as well as oversight and accountability by elected and judicial institutions. The violations of the security sector, and the lack of accountability to address such violations, have been a major contributor to sparking and sustaining violent extremism. This goes way back; since Sayyid Qutb significantly altered his ideology after witnessing a massacre in former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser’s prisons in 1957.

Overlapping security

Jihadism and Takfirism, in their purist forms, were both born in Egyptian political prisons in the 1960s, where torture was an endorsed systematic practice by multiple and overlapping security establishments: a situation that is not that different from today’s Egypt. Ultraconservative and extremist ideologies such as Wahabbism were also born and developed under authoritarian systems. None of the aforementioned ideologies have come out of a consolidated or a mature democracy.

Related to SSR are the unbalanced civil-military

relations in most of the Arab-majority countries. The supremacy of the military over all other state institutions has engendered a political environment in which state repression has become the most im-

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 35

photo: Dean Karalekas

A Pershmerga fighter in Iraqi Kurdistan stands guard over the ruins of one of Saddam Hussein’s palaces.

photo: Matthew Crane

US Coalition Forces fire an M120 mortar round targeting a known ISIS location in southeast Syria, 10 September, 2018.

portant method for attaining and remaining in political power. Such a context in which state-sanctioned violence is legitimated in various forms (including official religious institutions and hyper-nationalist propaganda) is less likely to lead to democratization or sustained stability.

Demobilization, disarmament and reintegration (DDR) are also critical processes for reducing violent extremism. However, the politicization of these processes and their failures in Libya and Yemen in the aftermath of the Libyan revolution and Yemeni uprising have led to the rise of multiple armed non-state actors. This resulted in facilitating necessary resources and logistics to organizations such as Daesh as well as al-Qaeda affiliated groups. DDR is directly related to SSR. Most armed non-state actors in post-conflict environments will refuse to disband and demobilize if there is no mutual trust or weak institutional arrangements to balance the relations with the official security and military sectors.

This is especially the case when these official sectors have been traditionally above oversight, accountability, and law. This is one reason for the failure of de-escalation in towns and regions such as Derna in eastern Libya to Sinai in north-eastern Egypt, the central and northern parts of Iraq, and the southern, south-eastern, and northern parts of Yemen, where armed actors representing the authorities are deeply mistrusted due to historical violations. SSR and DDR failure can undermine any future political solution in Syria and hence, in the long-term, empower various non-state actors. Popular support for national reconciliation, compromises, inclusion, and general de-escalation is crucial for undermining violent extremism, and the environments that engender and sustain it. b

36 Strategic Vision The Middle East

About the author

Dr. Omar Ashour is an associate professor of strategic and security studies at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies. He can be reached at: omar.ashour@ dohainstitute.edu.qa

A Q-53 radar with the 65th Field Artillery Brigade’s Target Acquisition Platoon scans to determine the point of origin of enemy indirect fire (IDF) during Operation Inherent Resolve, 14 August, 2018.

photo: Jacob Roy

Putting Borders Front and Center

The role of Front Commands in supporting Border Troops in the fight against terrorism

by Mohammed Ali Khawaldeh

by Mohammed Ali Khawaldeh

All countries seek to maintain their defense resources management in order to constantly maximize their efforts and capabilites. Adopting these orientations by utilizing border troops to secure large international boundaries despite the limited capabilities necessitates searching for the best available alternatives that empower the troops to maintain readiness, anytime and anywhere. The desire of governments to reduce wastage of defense resources is inversely proportional to the increase in the terrorist threat matrix and the diversity of various local, regional, and international strategic environments. Front Commands represent a point of balance between dealing with the growing costs incurred by a permanent state of readiness, and the ability to reduce the spread of terrorism across a country’s borders.

photo: Anthony Maw

Border guards from Pakistan and China find friendship at the remote Khunjerab Pass in the Karakoram Mountains.

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 37

Despite the importance of the role that ground troops play in providing security to communities and countries, feeding, housing, and paying a large standing army can be one of the most costly elements of a nation’s military resources. Some coun-

ing deployments to providing security, preventing infiltration, and combating smuggling.

Border troops face many challenges in carrying out their duties. For example, the distance between the fronts significantly affects the preparation of the troops on the operational side, as well as the difficulty of maintaining logistical supply lines. Especially after the emergence of new types of terrorist threats, which significantly came into existence in a number of countries whose stability and security are threatened by internal conflict, such as Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and Somalia.

tries do not have military troops, while others are looking for strategies that contribute to reducing military expenditures in peacetime. For example, some countries have adopted various strategies such as a rebalancing strategy or a redeployment strategy. Other nations choose to maintain a standing army even in peacetime, and they do this by adopting less aggressive policies, such as reducing the dependence on regular troops in service while retaining certain troops equipped with smart weapons, to lower costs. On the other hand, yet other countries endeavor to create a balance between these requirements, limit-

The search for possible solutions and appropriate alternatives that support the performance of border troops gives countries hope to enhance their capabilities in providing security and safety for their citizens. The question that deserves attention here is the ability of the Front Commands to perform duties and tasks efficiently and face the growing threat posed by terror organizations.

Global geopolitics is dominated by a consensus among nations on the importance of avoiding the use of armed military forces along border areas. The reason for this is because it is not commensurate with the principles that constitute the civil state. It is the purview of law enforcement bodies to deal with infiltrators and to combat smuggling, because these are violations of domestic law and therefore the responsibility of the judicial authorities.

Regardless of the name given to forces assigned to protect a nation’s border, these border troops should not be linked to

38 Strategic Vision The Middle East

“Global geopolitics is dominated by a consensus among nations on the importanceofavoidingtheuseofarmed militaryforcesalongborderareas.”

the command chain of the armed forces under any circumstances. Some countries nevertheless continue to engage their regular armed forces in the task of supporting the operations of regular border troops, either by helping to control the border against infiltrations or to carry out troop operations on their behalf, although this is contrary to laws that limit the use of regular armed forces in executing the State law. In the United States, for example, this was guaranteed by the Posse Comitatus Act. The independence of border troops in terms of engagement and self-reliance in operational, training, human, and logistical aspects is the best way to achieve stability and preserve constitutional norms.

Strategic variables

As a result of the nature of the duties of border troops, their large size, and the many variables in the strategic environment at the local, regional, and international levels, border troops face many challenges. First among these is commitment. Although most

countries believe it is important to avoid sending in the military to protect the border, some states consider Border Guards to be an integral part of their military forces. This is often illegal, as the military armed forces themselves are not authorized by law to protect the border, or to deal with border operations including infiltration and smuggling. Second, the vast distances between the fronts limit the follow-up processes and supervision of all aspects of operations, training, logistics and management. Hence, some countries have used their armed forces to assist or replace border troops, although no public mobilization or war has been declared.

Third, terrorist organizations and the fear they foment is especially volatile for neighboring countries, as well as countries embroiled in a civil war or insurgency, such as Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Yemen. Fourth, the mismanagement of the current border troops by their central command—often headquartered very far away—can be a problem, and is not commensurate with the need for training for strengthening and maintenance of advanced sites, in

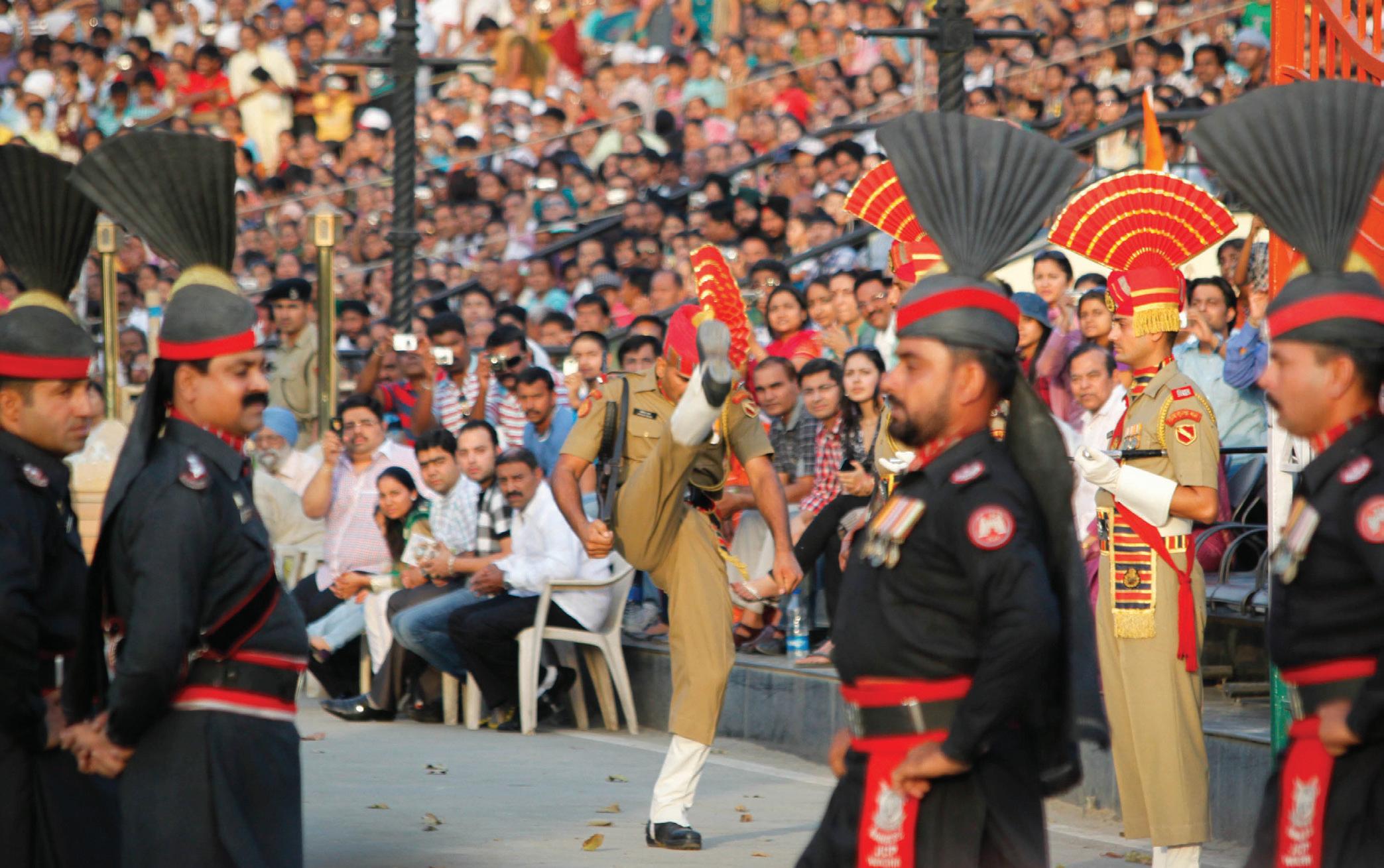

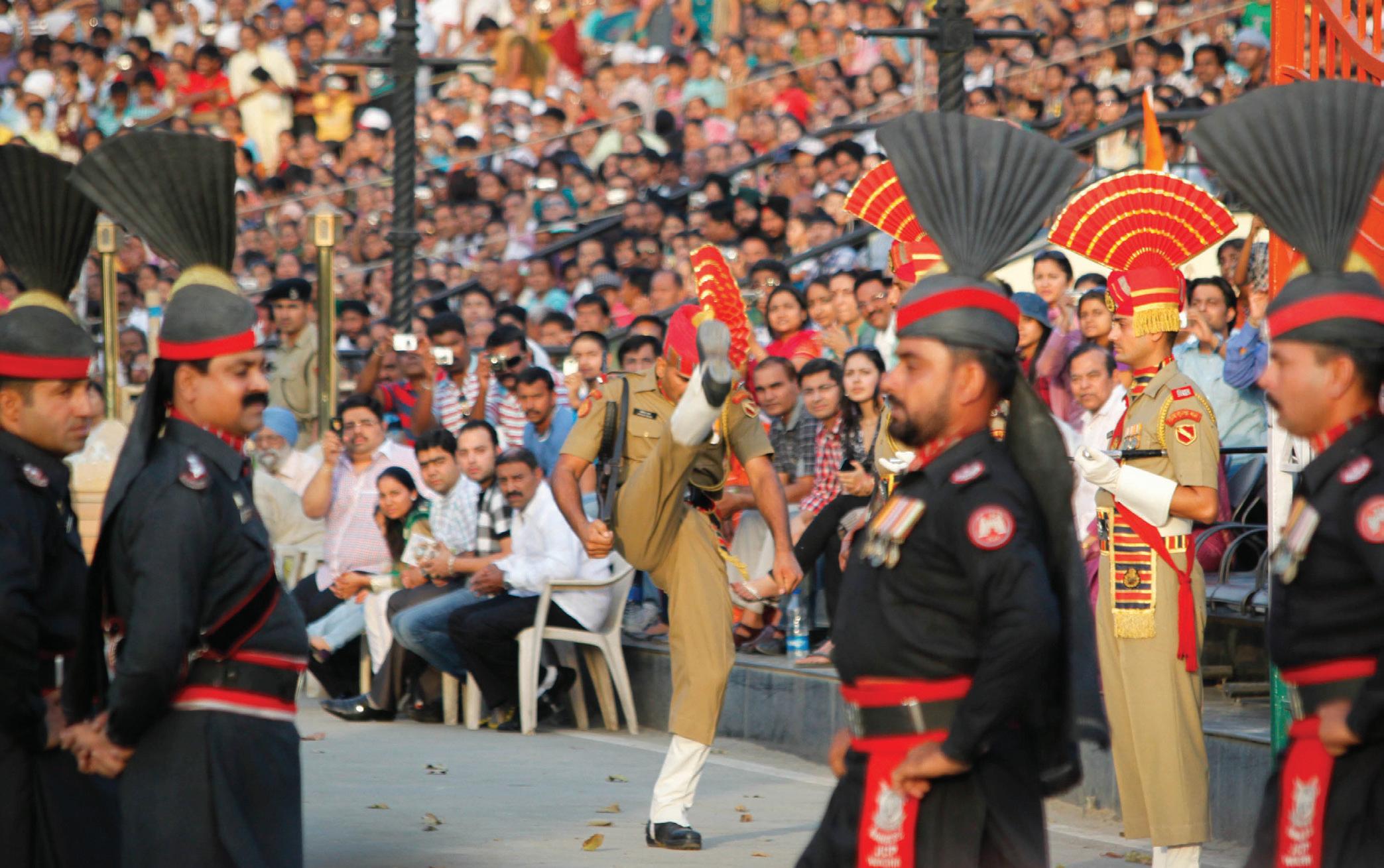

Troops with the Pakistan Rangers and Indian Border Security Force (BSF) both collaborate and compete in the evening flag-lowering ceremony at the India-Pakistan international border near Wagah.

Troops with the Pakistan Rangers and Indian Border Security Force (BSF) both collaborate and compete in the evening flag-lowering ceremony at the India-Pakistan international border near Wagah.

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 39

photo: Komail Naqvi

addition to the processes of supervision and followup of operations.

In order to minimize this problem, the Front Command should be deployed on all fronts, so that each Front Command is independent of the other Front Commands. Second is the issue of location: Front Commands should be located behind the lines of Border Guard forces, which are distributed along international borders. These locations should be between the main command of the Border Guards and border locations. Third is the issue of personnel: Efficient and appropriate staffing is a must to keep Front Command working sustainability in addition to the need for qualified personnel for the purposes of training in cases of force support and switching in border locations. Fourth, handling emergency situations relating to border infiltration, especially armed incursions, requires having a force of Ground Troops to support Border Guards or provide a quick reaction force. Fifth is related to training: as Border Guards are stationed along all international borders, and as these locations are distant from each other, it is necessary to have a specialized training center to qualify troops and train quick-reaction groups so

that they are prepared for the nature of their duties in each station, which may differ greatly from one another in terms of geography and climate. Sixth, in terms of linking and authorization, when these Front Commands are directly linked to the Border Guards’ Central Command with full authority, Front Commands are legally authorized to handle infiltration and smuggling cases correctly, for they are an essential branch.

Indispensible role

Front Command plays an indispensible role in counter-terrorism. In order to stop extremist ideology from reaching its targets, the most important factors are to surround terrorist organization of different affiliations.

Intelligence information about the tactics employed by these groups is essential, as such groups often resort to creative tactics, unconventional channels of communication, and illegal methods of crossing international borders—including doing the latter on foot or in light vehicles at poorly guarded points of crossing. Another tactic is to blend in with immigrants and

40 Strategic Vision The Middle East

photo: Jason Welch

The sun sets along the Iraq-Syria border as seen from a 3rd Squadron, 3rd Cavalry Regiment, observation point overlooking the Euphrates River in Iraq, Sept. 28, 2018.

refugees fleeing civil war and oppression, such as in the refugee crisis that saw millions of Syrian refugees, as well as other migrants from around the Middle East and North Africa, flow into Europe. Extremists and terrorist operatives were captured among this flow. Border guards along international borders must be very cautious when dealing with illegal immigrants, and doing so will force terrorist organizations to avoid threatening border locations directly because of the strict inspection procedures conducted at these locations to screen for weapon and bombs.

Moreover, terrorist organizations have also used long-term tactics such as sleeper cells which can be activated years after reaching and settling within the targeted country. These sleeper agents, as well as domestic converts who become radicalized by the ideology, make use of whatever weapons are available: guns, knives, and in many cases, vehicles.

The importance of the Front Command in the guarding of a nation’s borders is to ensure that the Border Guard force is not just one with the appearance of a military, thereby deterring incursions, but one that actively reinforces the security of the state

and the integrity of its borders by providing the intelligence and training necessary for dealing with today’s terrorist threats. More and more, the Front Command reinforces the civil state concept by enforcement of the state’s laws to deal with infiltration and smuggling, in addition to which it reduces the waste of defense resources by reducing the size of the military in peacetime as much as possible, such as through the activation of reserve forces as needed.

The role that the Front Command plays in the improvement of security and supporting the performance of Border Guards, who are often spread thin, is vital. The outlook for the future of these forces, especially at the level of large international organizations, and their ability to defend the border integrity of countries suffering from armed threat or civil war depends upon the adoption by their governments of forward-looking policies. b

About the author

Dr. Mohammed Ali Khawaldeh is a retired brigadier general in the Jordanian Armed Forces. His research interests include counterterrorism and border security. He can be reached for comment at maakrrrm@gmail.com

An Afghan border police officer assigned to the Nangarhar province 6th Kandak scans the perimeter.

Autumn 2018 Special Issue 41

photo: Tracy Smith

Turkey And The Gulf Crisis: An Analysis Of Turkish Foreign Policy

by A. Engin Oba

by A. Engin Oba

42 Strategic Vision The Middle East