We design, procure and construct all types of water treatment infrastructure, that is

Ÿ We install water treatment systems for surface and ground water.

Ÿ We design and operate wastewater treatment systems for domestic and industrial wastewater.

We provide basic and detailed designs of engineering processes such as Compressed Air Systems, Chilled Water Networks and Fire Water Systems

We provide technical support for delivery of Construction, Power Mining, Water and Wastewater projects

BOT (Build Operate and Transfer) model for sustainable solar power to large consumers at a discount of national grid rates.

This publication comes on the backdrop of our recent successful conference, which was a fair success. The theme of the conference, Building for Africa’s Urban Million: Infrastructure Renewal and Development resonated well with the challenges and opportunities thereof we face today in our practice.

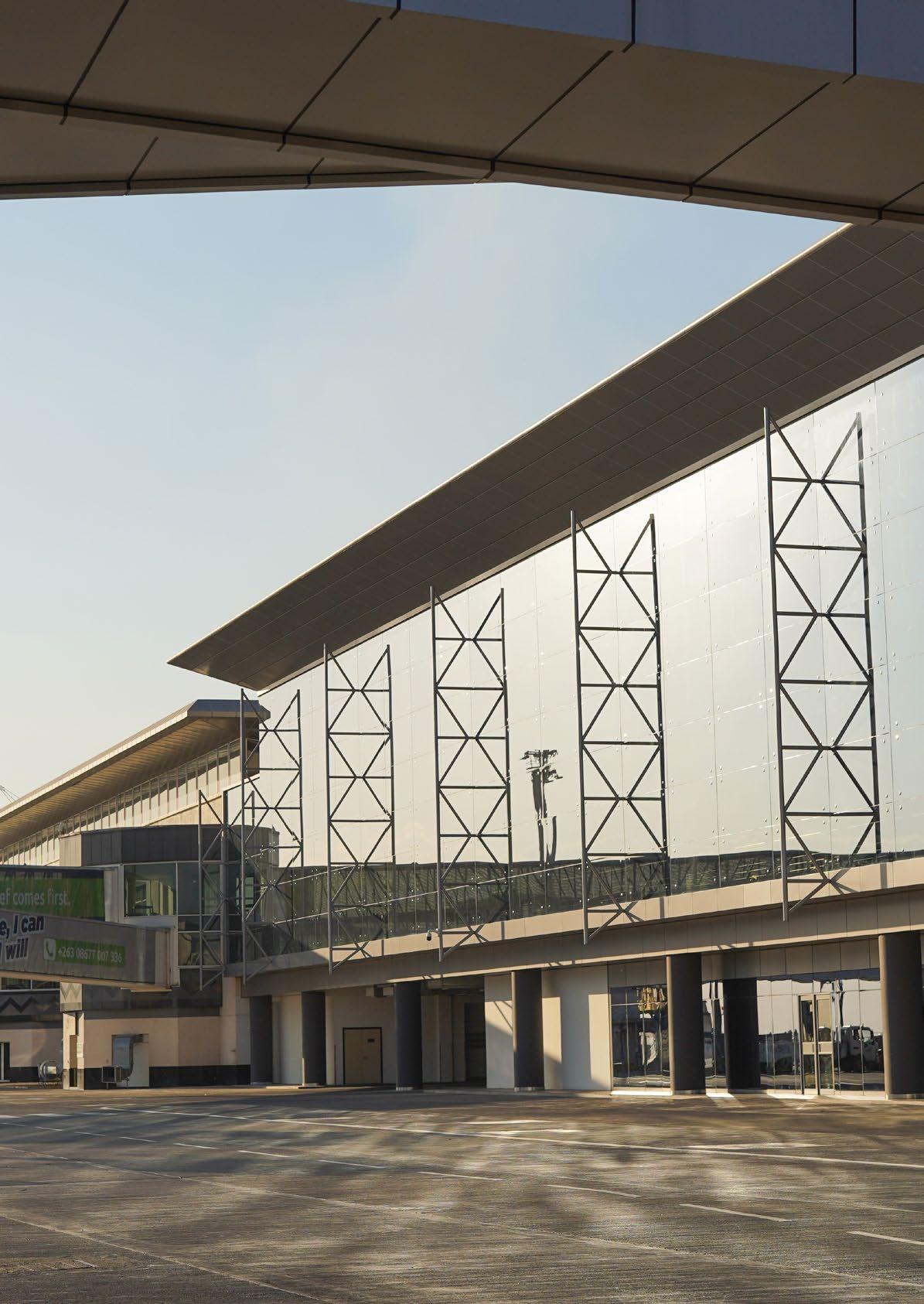

As we speed through 2024, it is clear that construction in Zimbabwe is experiencing a significant upswing. There is a notable increase in construction activities across the country, leading to a lot more architects finding work and more employment opportunities for the graduates in architecture. This positive trend is a win for the architectural community.

However, with this surge comes the responsibility of seeing to it that our built environment is shaped by qualified professionals. Recent incidents in urban areas have made it evermore important for city councils to adhere strictly to the Architect’s Act. It is imperative that only those with the requisite qualifications are entrusted with the design and oversight of public buildings and commercial structures.

As we are in the second half of the year, we can see numerous construction projects underway progressing steadily, some of which are carryovers from last year.

This continuity and growth reflect the relative stability we are experiencing as a nation, which we hope transcends to the built environment, leading to even more projects in the future.There also has been a remarkable increase in the number of architects in the country and we are anticipating to have more. Our Yearbook provides a legitimate and up-to-date list of professionals available to the general public.

Within this magazine, you will also find quality interviews with select architects who have played pivotal roles in shaping the streets and skyline of Harare and beyond. These discussions offer a blend of experience and foresight, celebrating both our veteran architects and the emerging talents who are poised to lead our profession into the future.

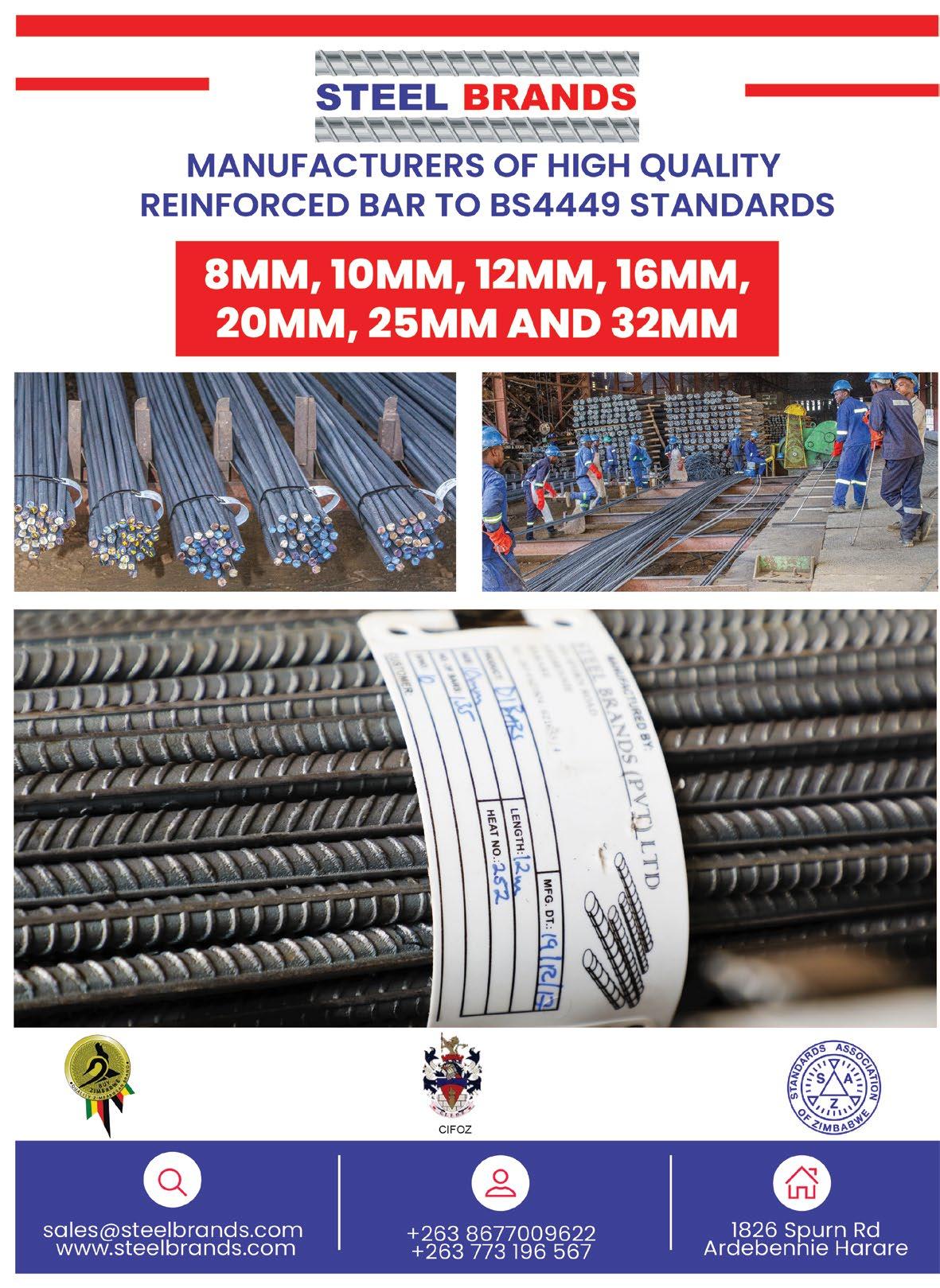

Looking ahead, we are excited about the advent of new building materials and alternative construction methods.

While these innovations promise to revolutionise our industry, it is crucial that they comply with the Standards Association of Zimbabwe and other regulatory bodies. Proper regulation, testing, and certification are essential to ensure safety and quality. Nonetheless, this is an exciting time for architects as we explore these new frontiers in construction.

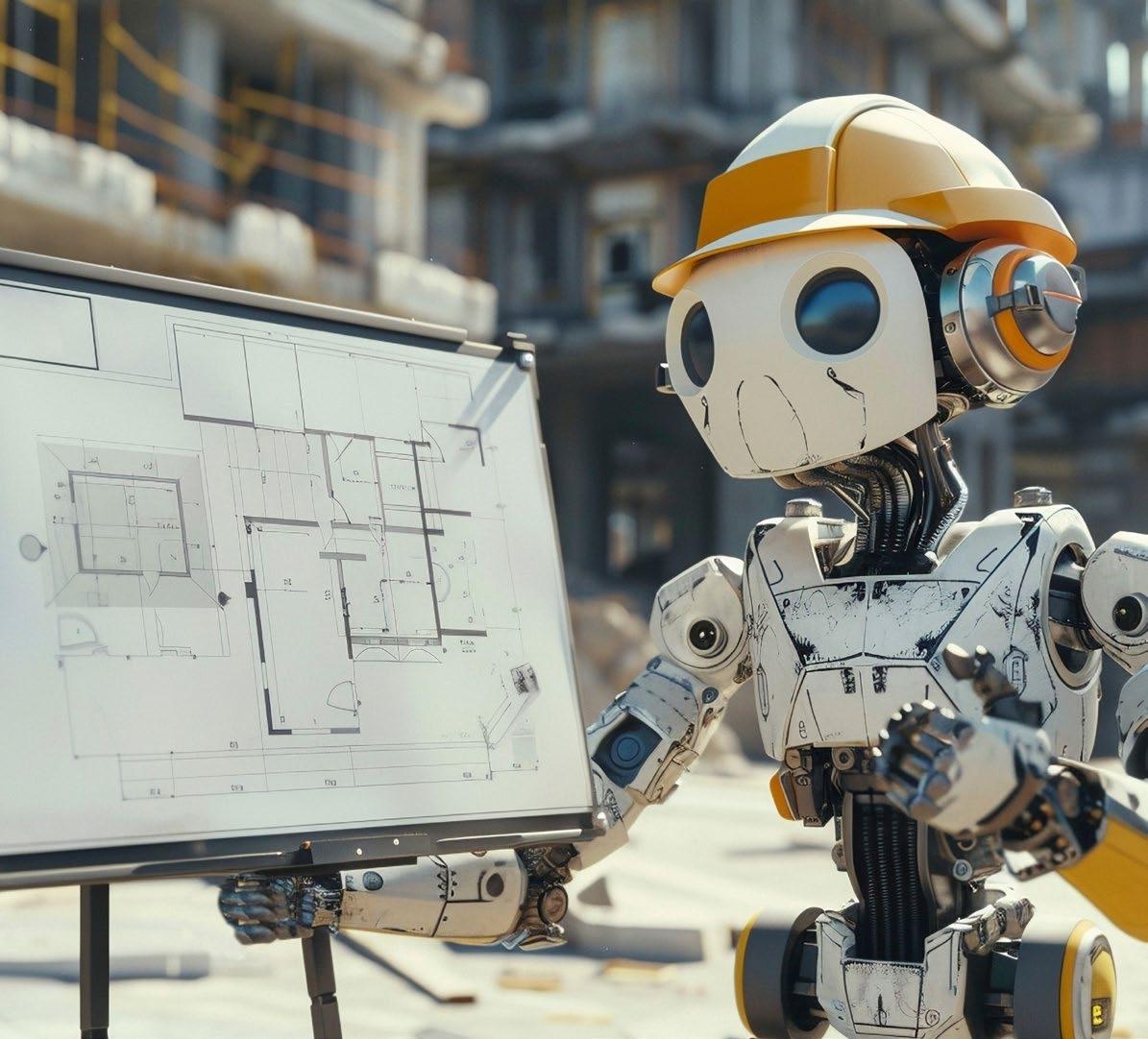

Another topical issue is the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on our profession.AI is becoming increasingly visible in various industries, from automotive to manufacturing, and architecture is no exception.

Architects must stay abreast of the latest advancements in AI technologies and software. These tools have the potential to enhance our work significantly, offering new capabilities and efficiencies.

However, these also demand that we adapt and evolve; embracing these technologies and what they can do for our industry.

We laser cut from 0,5mm to 25mm thickness.

We offer technical expertise & strive to turn your ideas into reality.

The Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe was founded in 1924 as the Institute of Southern Rhodesia Architects and became legally established by the Architects (Private) Act in 1929. The year 1929 therefore marks the legal establishment of the now Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe. Its main objectives are to promote the art of architecture and architectural education in the interests of the community and provide full membership status to Architects who are registered with the Architects Council.

There are various classes of membership open to other than registered architects; graduate, student and members of associated professions or other individuals with an interest in architecture. The Board of the Institute meets on a monthly basis to discuss common problems. Since 1957 the Institute has made every effort to see a School of Architecture established in Zimbabwe and monitors the examination systems of the Architectural Technician’s courses at the Harare Polytechnic College, Bulawayo Polytechnic College and those set by the National Association of Architectural Technicians.

The Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe sets professional practice examinations each year for the purpose of registration with the Architects Council. The Institute holds conferences and lectures on architectural and related topics.

The first school of architecture in Zimbabwe was established in 1998 in Bulawayo at the National University Of Science And Technology (NUST).

ACZ Chairman: Arch. Arthur Matondo

ACZ Vice Chairman: Arch. Tobias Chombe

IAZ President: Arch. Brighton Madondo

Vice-President: Arch. Ishumael Gura

Board Members:

Architect Ratidzo Gumbo

Architect Takunda Chimbwa

Architect Collin Maedzenge

Architect Andrew Sanyangore

Architect Tapiwa Manditsera

Registrar: Arch H. Sakupwanya

An Architect is a trained designer of buildings and building related fields, and has expertise not only as a problem solver, but in being able to analyse and define problems. In analysing a client’s brief the Architect is able to offer alternative solutions from which a client may select and can offer the client alternative ways of viewing the same problem.

The Architect combines creative ability, technical knowledge and managerial expertise to be able to interpret a client’s requirements into built form. He takes into account the restrictions of site and budget, of statutory regulations, of culture, climate and geographical setting and is able to produce buildings and environments that are useful, well designed and pleasing to their owners

combined with his managerial and design skills, give the Architect a unique overview of the building process. He will advise on the appointment of specialist engineers or quantity surveyors and co-ordinate their various services to meet the building programme.

Architects are employed in Government departments and parastatal bodies, large corporates, in Municipal and private offices. Principals in the private sector are required to be registered in terms of the Architects Act (1975). Architects in Government or Local Government service are exempt. An Architect in the private sector in Zimbabwe is a qualified person legally registered and bound by a professional code of conduct. He competes with his colleagues on the basis

1925 -1927 J.R. Hobson

1927 -1928 J. A. Cope Christie

1928 -1929 D. McGillivray

1929 - 1930 W. D’Arcy Cathcart

1930 - 1932 D. McGillivray

1932 - 1933 J. D. Robertson

1933 - 1934 F.A.O. Jaffray

1934 – 1936 J.R. Hobson

1936 – 1937 S. Austin Cowper

1937 – 1938 J. D. Robertson

1938 – 1939 E. Pallet

1939 - 1941 J.R Hobson

1941 - 1942 D. McGillivray

1960 - 1962 R.G.B Wilson

1962 - 1964 P.L. Oldfied

1964 - 1965 H.A. Hotson

1965 - 1969 R.C. Brown

1969 - 1971 R. Densem

1971 - 1973 J. Van Heerdan

1973 - 1975 J.G. Capon

1975 - 1978 P.A Naude

1978 - 1979 R.E. Cooper

1979 - 1981 H.O. Beck

1942 - 1943 E. Pallet

1943 – 1944 J.R. Hobson

1944 – 1946 W. D’Arcy Cathcart

1946 – 1947 R.K. Price

1947 – 1948 W.E. Alexander

1948 - 1949 C.H. Rees

1949 – 1951 R.S. Parker

1951 - 1952 L. Ayers

1952 – 1954 C. Ross Mackenzie

1954 – 1955 A.C. Dold

1955 - 1956 C. Ross Mackenzie

1956 – 1958 J.L. Gauldie

1958 - 1960 W.H.G. Stenson

1985 - 1986 G.M. Mills

1986 - 1987 K.B. Lever

1987 - 1989 S.S. Bais

1989 - 1990 G. Price

1990 - 1993 V. Mwamuka

1993 - 1997 P. Naude

1997 - 1999 Standish-White

1999 - 2001 N. Mills

2001 - 2003 P. Nhekairo

2003 - 2005 J. Dzimwasha

2005 - 2007 D. Mandishona

2007 - 2012 J. McCormish

2012 - 2014 I. Masiyanise

2015 - 2017 A.T. Matondo

2018 - 2019 E. Murwira

2020 - 2022 T. Dzvukamanja

2023 - 2024 Brighton Madondo

The Architects Act of 1975 repealed the Architects (Private) Act of 1929 and established the Architects Council to provide for the registration and regulation of the practice of architecture in Zimbabwe. The Council consists of eleven members, nine of which are elected from the Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe and two appointed by Government. It administers the Act with particular reference to:

1. Registration Requirements — standards are set for academic and professional experience which include the passing of the Zimbabwean Professional Practice examination and a residential qualification.

2. Use of Title and Function of an Architect

1976 – 1978 P. Naude

1978 – 1979 J.A.K. Hope

1979 – 1981 H.O. Baeck

1981 – 1986 P.L. Oldfield

1986 – 1989 P. Jackson

1990 - 1991 V. Mwamuka

1991 - 1992 P. Oldfield

1992 - 1993 E. Gurney

1993 - 1995 P. Naude (ACZ Chairman and IAZ President)

1996 - 2000 P. Oldfield

2000 - 2001 P. Jackson

2002 - 2006 G. Mthupa

2007 - 2008 M.C.R. Vengesayi

2008 - 2011 M.C.R Vengesayi

2012 - 2015 W. M. Kurebgaseka

2016 - 2017 A. R. Mandizvidza

2018 - 2019 I. T. Masiyanise

2020 - 2022 J. McComish

2023 - 2024 A. Matondo

The Architects Council of Zimbabwe (ACZ)’s main aim is to protect the client and the community from improper services of a person falsely claiming to be an architect, an unregistered or unqualified architect, and from gross negligence on the part of a registered architect. It is a statutory body in place to uphold the conditions of the Architects Act and to facilitate the regulation and registration for the practice of architects in Zimbabwe.

In Zimbabwe, a holder of an architecture qualification only gets to practise as an architect or do the work of an architect after registering with the Architects Council of Zimbabwe. The Architects Act of 1975 describes the work of an architect as the designing of buildings or of additions thereof, the supervision of the work of constructing

also offers membership to non-architects, only architects can be members of the Architects Council of Zimbabwe.

The Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe’s main objectives is to promote the art of architecture and architectural education in the interests of the community and to provide full membership status to Architects registered with the Architects Council.

It is also the Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe which sets professional examinations each year for the purpose of registration with the Architects Council.

The IAZ is also responsible for the hosting of conferences, events and lectures on architecture and related topics.

Kindly visit our website at https://www.zimarchitects.com/ for more detailed

An Architect can tackle any building problem, however large or small whether urban or rural. Some offices may have preferences for the type of work they handle, but an Architect coming fresh to a new brief is just as likely to produce a good answer as one who has tackled similar briefs many times.

An Architect may have particular skills in addition to those already described. He may also be a specialist in town planning and urban design, or in interior design, or landscape design, or renovation of older buildings.Most building projects proceed in the following manner, with the Architect taking the project through a number of stages:

1. BRIEF: Discussions with a client, establishing and analysing the client’s requirements.

2. FEASIBILITY STUDIES: Testing alternative proposals, looking at each in terms of value for money and the options each solution offers the client. Research into local regulations, site limitations and other constraints. Some projects do not proceed beyond this or the next stage.

3. PROJECT: Drawing outline plans, sections, elevations and maybe perspective sketches or making a three dimensional model, to communicate the essential characteristics of the proposed building to a client obtaining his approval and producing final design.

4. CONTRACT: Preparation of detailed information required for Building By-laws, Town Planning and other legislative approvals and for

construction. Production drawings show how each building component is constructed and built against another, while schedules and bills of quantities ist and describe all the materials required. Detail design can involve consultation with other specialists, i.e. quantity surveyors, structural engineers, and suppliers of specialised equipment, as well as ith the client and the Local Authority. The tender stage requires the obtaining of prices from builders, making recommendations to the client, preparing the Contract documents for signature.

5. SUPERVISION: The last but not least important part of an Architect’s work is to see that the building is built in accordance with the original drawings and specifications, and to assist in solving any unforeseen problems that may arise on site. The Architect works to the benefit of both the client and the building contractor, and although employed by the client, must remain impartial in any dispute which might arise.

In addition to these tasks, the Architect is often called upon to carry out surveys of existing buildings, advise on defects and maintenance problems as well as to advise on alterations that may be required.

A current list of registered Architects and firms is always available from the Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe.

Architectural firms range in size from one-man offices to organisations employing quite a number of assistants and technicians. Some large offices prefer not to be involved in small projects, while small practices may not be so experienced in larger projects. Some firms have wide experience and larger manpower resources to draw upon. Others may have exceptional design ability and an enthusiastic approach to their work. No matter what the size of the firm, all are controlled by qualified Architects

Such an interview might ideally take place at the Architect’s office where drawings, photographs and models of his work are available. Questions which may be asked include:

• what special expertise the firm can offer?

• how busy is the firm and their capacity to satisfy your programme?

• who will be responsible for your project, and an assessment of how well you might be able to work and communicate together?

• does the firm carry professional indemnity or insurance?

copy.

(d) Certified evidence by way of curriculum vitae, drawing or photographs that the applicant has met the requirements.

(e) Details of the project in Zimbabwe with which the applicant is involved.

(f) Letter of association on the project between the applicant and a registered Architect, signed by the latter.

1. Apply to the Secretary/Registrar of the Architects Council to sit the examination in Professional Practice, supporting the application with documentary evidence as required in paragraph 6 of Guideline’s for Registration by Requirements in Zimbabwe.

2. On passing the Professional Practice Examination, Complete the form Application for Registration as an Architect (AG1) following the requirements of the Architects (General) by By-

Architects Council

• Temporary Registration Fee (for one year only, renewable)

• Registration Fee

• Annual Subscription

Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe

• Entrance Fee

• Annual subscription

MEMBERSHIP FEES*

• Student membership

• Graduate membership

• Affiliate membership

• Retired Membership

*Enquire the Fees from the IAZ Offices

laws 1976, section 3, and section 16(1) of the Architects or Act 35/75, and submit to the Secretary/Registrar.

3. Registered Architects may then complete the form for Application for membership of the Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe, and submit it to the Secretary.

4. Persons applying for temporary registration may apply for membership of the Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe concurrently.

5. All Architects in full time bona fide employment with the State or Local Government are eligible to apply for full membership of the Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe subject to proof of academic qualifications and verification of employment with such organizations. Such members will not be liable to the Practice levy.

All forms are available from the Institute’s offices at Dorking House.

There are four classes of Associate Member

(a) Student Members - persons undergoing a course of study approved by the Board.

(b) Graduate Members — persons who hold a qualification in architecture approved by the Architects Council for registration, but are not registered.

(c) Affiliate Members - persons or body of persons who have affiliated architectural interests.

(d) Retired Members — persons who have been members of the Institute for at least five years and have retired from practice.

Associate membership is intended for those persons who are not registered architects under the terms of the Architects Act 1975 and therefore may not perform the work of an Architect.

No Associate Member is entitled to vote at any General Meeting or to nominate or second any candidate as a member of the Board or to cast his vote for any such candidate, nor shall he be eligible for nomination or election as a member of the Board.

S.I.829 of 1980 (As amended by S.I.222 of 1994 & S.I.110 of 2013)

GENERAL DUTIES OF ARCHITECTS

the provisions of the Schedules on the percentage of14 (3) (a) the final cost of the completed work; or 14 (3)(b) when payments are to be made before the final cost can be ascertained -

(i) an estimate by the Architect or quantity Surveyor for the complete work;

(ii) the lowest bona fide tender for the complete work, excluding any amount in that tender in respect of contingencies, if no contract is entered into;

(iii) the contract sum

or more contracts, the fees shall be calculated separately in respect of the work covered by each contract.

21.(1) Where an Architect provides only part of the services normally provided by an Architect, the fee for that part shall be calculated on a pro rata basis:

Provided that, if only a part of the normal service on any stage is provided, the fee for that part shall be calculated on a time basis in terms of the provisions of the Fourth Schedule.

Provided that, when work is executed wholly or in part with old materials or where material labour or carriage is provided by the client, the percentage shall be calculated as if the works had been executed wholly by a contractor supplying all labour and new materials at such rates as were applicable at the time when the work was executed 14 (4) The fees payable an respect of any stage of the work of an Architect shall be calculated according to the provisions of the

22. (2) Where an Architect has been paid his fee in respect of a commission which has been terminated or deferred, it that commission is subsequently resumed 22. (2) (a) without substantial alteration within two years of termination, the fee so paid to him shall be regarded as payment on account toward the total fee due, based on the final costs of the project; or

any building, the fees charged by him shall be in accordance with the provisions of the Fifth Schedule with a minimum fee to be inquired at the Institute, exclusive of any expenses or changes mentioned in section 19.

26. Where an Architect is appointed as an arbitrator for any dispute in terms of these by-laws, he shall charge26. (a) if there is more than one arbitrator, on a time basis in forms of the provisions of the Fourth Schedule 26. (b) if he is the sole arbitrator, fees should be inquired at the Institute. 43

27. Where an Architect is called to give evidence before any court or tribunal as an expert witness, he shall charge on a time basis in terms of the provisions of the Fourth Schedule, depending on the complexity of the problem.

28. Where an Architect undertakes, on behalf of a client, feasibility studies involving a preliminary technical or economic appraisal of a project in order to enable the client to decide whether and in what form he shall proceed with the project, he shall charge an additional fee for such studies, which shall, unless otherwise agreed with the client, be calculated on a time basis in terms of the provisions of the Fourth Schedule, depending on the complexity of the problem.

29. Where an Architect undertakes any of the following services, the services shall be agreed to and defined in writing, and remunerations therefore shall be in addition to the fees elsewhere enumerated in this Part, and shall be calculated on a time basis in terms of the provisions of the Fourth Schedule -

29. (a) advising as to the selection and suitability of the site;

29. (b) negotiations as to the site and buildings, if any;

29. (c) the preparation of additional drawings necessitated by a material alteration in, or in addition to, the client’s instructions, or altering the working drawings and specification in consequence thereof prior to the commencement of work;

29. (d) altering drawings or preparing new drawings and promoting other services involved in Consequence of variations or additions required by the client after the commencement of work;

29. (e) making extra drawings for the client’s or contractor’s use, drawings for and negotiating with landlords, tenants, adjoining owners, public authorities, licensing authorities, or other services in respect of servitudes, litigation, arbitration or valuations, bankruptcy, negligence of parties, force majeure;

29. (f) any survey or investigation of an existing building;

29. (g) any inspection of building work in progress not referred to elsewhere in the regulations;

29. (h) any specialist consultant architectural services, including the design of residential, industrial or commercial layouts;

29. (i) any interior or furniture specialist joinery design, shop fittings or exhibition work

30. Where an Architect engages to perform work in respect of a building to be erected outside Zimbabwe, he shall, in respect of

31. Where an Architect undertakes any services for which fees are not adequately provided in this Part, he shall apply to the council for guidance in respect of the fees which he should charge.

32. An Architect shall ensure that any agreement entered into with clients provides for -

32. (a) the termination there of at any time by either party on the giving of reasonable notice; and

32. (b) the remuneration of the Architect in accordance with the provisions of Part III for services rendered prior to the termination of the agreement.

33. An Architect may agree with his client that any difference or dispute which they may have shall be referred to the council for a ruling, subject to the following provisions -

33. (1) (a) the reference shall be by way of submitting a joint statement of undisputed facts, plus separate statements of disputed facts;

33. (1) (b) the Parties shall agree in writing to accept the ruling of the council as final and not subject to appeal,

33. (2) An Architect shall ensure that in his agreement with his client, provision is made that where any difference or dispute arising out of the requirements of these by-laws cannot be determined in accordance with the provisions of subsection (1). It shall be submitted for arbitration by a person agreed between the parties and that —

33. (2)(a) either party may give to the other a written request to agree on the appointment of an arbitrator

33. (2)(b) if, after fourteen days from the request referred to in paragraph (a), there is no agreement, the chairman of council may, at the request of either party, nominate an arbitrator.

34. The Architects (Conditions of Engagement and Scale of Fees) (Amendment) By-laws. 2000 (No. 5), published in Statutory Instrument 3210 of 2000, are repealed.

N.B. This scale and the Schedules refer to the lowest fees which may be charges by an Architect for his services, for which his client’s formal acceptance is required. See subsections (1) and (2) of section 13.

4. (1) An Architect may recommend to his client that a specialist subcontractor be engaged for the 4. (2) Where a subcontractor is engaged by his client, an Architect unless it is otherwise specifically agreed, shall -

4. (2)(a) be responsible for the direction, integration and general supervision of works executed by the subcontractor; and 4. (2) (b) ensure that the subcontractor accepts sole responsibility for any design undertaken by him.

5. (1) An Architect shall ensure that -

5. (1)(a) before initiating any stage of his duties referred to in Part II, he has the necessary authority of his client; and 5. (1)(b) before deviating in any material respect from a design approved by his client, he has the consent of his client thereto:

Provided that, if any such alteration is necessary as a matter of urgency for constructional reasons or on order to comply with any enactment, the Architect may authorize such alteration, and shall inform his own client thereof without delay.

5. (2) Where an Architect becomes aware of any likely variation of expenditure authorized by his client or the estimated period within which any work for his client will be completed, it shall be his duty to inform his client thereof forthwith.

6. Where an Architect is required to supervise the construction of any work, it shall be his duty to give such periodic supervision and inspection of the work as is necessary to ensure the proper execution of the work in accordance with the provisions of contracts relating thereto, but, unless it is otherwise agreed, constant supervision by the Architect shall not be required.

RESIDENT ARCHITECT

7. Where an Architect has agreed with his client that a resident Architect should be employed in order to provide constant supervision of any works, the Architect shall, unless it is otherwise agreed, be responsible for the employment of the resident Architect and for his remuneration on a time basis in terms of section 15, which shall be recovered from his client.

8. Where a clerk of works is to be engaged by his client, the Architect shall recommend the appointment of a suitable person, and shall advise that any person so engaged will be employed by the client, under the management of the Architect, an remunerated by the client.

9. Where a consultant is engaged by his client, an Architect shall, unless otherwise specifically agreed9. (a) make it clear that the consultant is responsible for the work entrusted to him

9. (b) advise the client that the payment of the fee of the consultant is the responsibility of the client.

COPYRIGHT IN PLANS, ETC

9A. Before concluding a contract with his client, an Architect shall ensure that the contract makes provision for the vesting of copyright in any plans, drawings and other work done in pursuance of the contract.

LIMITATIONS OF ARCHITECTS LIABILITY

10. Before preparing working drawings for his client, it shall be the duty of an Architect to10 (a) hold preliminary discussions with his client for the purpose of determining the requirements and scope of the commission; 10 (b) prepare a brief, outlining the requirements and planning proposals including the necessity or otherwise of appointing any specialist consultant or clerk of works:

10 (c) advise on the form in which the project is to proceed 10 (d) advise on town planning and building by-law legislation and on the financial limitations set by the client, (e) prepare design drawings, which snail show the general layout, design, construction, outline specification and costs of the work sufficient for the purpose of obtaining the approval of the client. 10 (f) obtain the approval of his client of the design, specification, construction and cost of the work before proceeding to working drawings.

11. The Architect shall proceed to contract stage as follows — 11 (a) prepare working drawings, details, schedules arid other documents necessary for the complete carrying out of the works; and

11. (b) co-ordinate the work of any specialist consultants employed, and supply them with all information required by them to complete their part of the work, and 11. (c) ensure that all necessary by-law and other building approvals have been received; and

11 (d) call for, and receive, any tenders required, and advise on their acceptance; and

11 (e) prepare for signature any contract documents required in connexion with the work; and

11 (f) select and recommend a suitable person for appointment as clerk of works

12. Where an Architect is required to supervise the construction of any works, he shall be responsible

12 (a) for approving the programming for the progress of the work set by the contractor; and

12 (b) until the works are completed, for making such periodic visits to the site as may be necessary to ensure that the provisions of the contract relating to the construction of the works are fulfilled, > co-ordinating the work specialist consultants, and issuing any certificates of progress or other certificates which may be required; and

12 (c) for rendering such assistance as may be required to the contractor in handing over the building to a client in a state suitable for occupation; and

12 (d) for presenting the final accounts relating the work.

13 (1) The fees provided in this Part shall not be lower than the scale and variations referred to in the First, Second, Third, Fourth and Fifth Schedules.

13 (2) The Architect shall inform his client and obtain formal acceptance, before he renders the service concerned, of the fees which he intends to charge, whether the fees are in excess of those referred to in subsection (1) or not.

VARIATION OF FEE SCALE

Type of building

Dwelling - house

Hospitals, nursing homes, clinics, laboratory complexes or similar buildings requiring extensive specialized services

Industrial buildings where the Architect is the principal agent

Industrial buildings where the Architect is not the principal agent

HOUSING SCHEMES -

(a) For each prototype building in detached, semidetached, terraced or flatted form

(b) For identical repetitions of (a) and reuse of documentation without site-and-service drawings

(c) Supervision of (b)

(d) Site-and-service plans

(e) Design of general layout, modifications to the drawings and documents of (a)

(f) Landscaping, sewerage and road works

Alterations and additions to existing buildings

THE FEE SCALE -

One per centum of contract cost or estimated cost Third Schedule, 1.5 per centum of contract cost Six per centum of site-and-service costs per unit Fourth Schedule time charges

As consultants

The fee scale + up to 50 per centum, at Architect’s discretion, depending on circumstances

Fee

The fee scale +30 per centum

The fee scale + 20 per centum

The fee scale, but may be reduced by not more than 20 per centum, depending on the proportion of open repetitious or storage space

Fourth or Third Schedule by agreement

Twenty-five per centum of total fee, made up as follows -

(a) Brief: five per centum of total fee

(b) Preliminary design: ten per centum of total fee

(c) Final design: ten per centum of total fee

CONTRACT

Fifty per centum of total fee

Working drawings, schedules and contract documentation

SUPERVISION

Twenty-five per centum of total fee

Issuing interim and final certificates, architects instructions and further drawings

FOURTH SCHEDULE (Section 15)

Rates should be inquired at the Institute.

FIFTH SCHEDULE (Section 21)

Rates should be inquired at the Institute.

“Architectural opportunities in Zimbabwe, let alone Africa are so many as we have not even scratched the surface” Irene Masiyanise

text by Farai Chaka

As the first Black female president of the Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe, Irene Masiyanise reflects on her tenure, the evolution of sustainable practices, and the future of African architecture.

Q: You mentioned that becoming an architect was a "happy accident." Can you recount the moment you realised that architecture was the perfect fit for you, not geology?

A: Yes, coming into architecture was a happy "accident" for me because it wasn't a field that I was aware of at all when I was at school. I was very fortunate that in my family, I had uncles who were professional Geologists and Land Surveyors. In school, I excelled at Geography, which drove my passion to think that Geology was the profession that I would pursue.

When I discussed it with my Mom and told her that I was going to pursue a career in Mining as a Geologist, she raised concerns as we didn’t have enough information on the health and safety of mines. I started looking at it (geology) differently and considered land surveying. I then made an inquiry from the Surveyor General at the time, and when I went to see him, he advised me that land surveying might not be the best field for a young woman.He mentioned other related career paths like engineering, architecture, and town planning.

In my further inquiry into those disciplines, I came across a cousin who is an architect. My parents pointed me to him, and after making inquiries, I found that architecture was more interesting. It offered a variety of work environments — being on-site, working in the office, having outdoor time and indoor time. I liked the transition of creating something from nothing to something and seeing things come together. That’s how my journey in architecture started.

Q: How would you describe your design philosophy generally? What core principles guide your architectural work?

A: I'd say the core principles that guide my designs are circulation, which entails movement and interaction of spaces, whilst incorporating sustainable design theories and philosophies of natural lighting and ventilation.

Q: Who in the world of architecture has inspired you the most, and how has their work influenced your own?

A: My architectural inspiration was more from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who used a lot of the principle of “less is more”, and Le Corbusier who liked to express the elements of the buildings, especially columns and long windows and geometric forms that were very clear and clean. Those two

modernist architects inspired me a lot, and also Team Zoo, who were the architects that I worked for in Japan.

Q: Having worked in the UK, Japan, Taiwan, and the US, how did these diverse cultural environments influence your architectural style and philosophy?

A: The architects at Team Zoo create designs that seem sculptural. Their architectural style of façade treatment and choices of material almost result in buildings that are speaking to the landscape. Then, with Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier, the former influences the way I curate my layouts, and my circulation spaces and Le Corbusier influences the way I treat my facades, the elements that I use, and how I express those elements. An amalgamation of their architectural style and philosophy is evident in the influences of my design work. I have integrated their forms and their design principles in my work to come up with my style.

Q: You were the first Black female president of the Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe. How would you describe your tenure?

A: The dates of my presidency were Vice President from 2008 to 2011 and President of the Institute of Architects of Zimbabwe from 2012 to 2014. After a short break from the board, I returned and was appointed the Chairperson of the Architects Council of Zimbabwe.

My tenure was very interesting. When I was voted president, I wasn't thinking about my gender or my colour. Prior to that, I had served on the board for a substantial number of years, which gave me a good grounding and background in the Institute and at work. I had served under some excellent leaders like Mandishona (RIP) and Jim McCormish, both of whom were presidents before me, and I was on the board serving with them. They ran IAZ during a difficult time, but their commitment to serving the Institute and their dedication inspired me. I picked up a lot from them and the ideas we shared on the board.

When I took up office, I found that some of the ideas we had discussed and that I had thought were not possible to implement due to the economic environment they served under, I was able to implement. I came in in 2012 when things were a bit more stable, and I thought it was time to bring some life into the Institute. We had not had architectural conferences for years, so with the help of my team— excellent board members—we revived the architectural conferences. I'm glad to say that from the time I reintroduced them, we had successful conferences, and they continue to be successful to this day.

My tenure was very insightful and involved. There is a lot of commitment required when you're president, and it can be quite demanding, but I enjoyed it. It gave me opportunities to interact with nearly all the architects, colleagues in the industry, engineering and construction contractors, and a few corporates. It was challenging at times but always interesting.

I was also the first female chairperson of the board since it was enacted in 1975, so it was a huge responsibility. The position came with significant responsibility, which I enjoyed, and I learned a lot. It helped me serve my council and having had that position always lurks at the back of my mind. I'm almost a de facto chairperson in the way I do things though I make it a point not to overstep boundaries.

Q: Sustainability has become a crucial aspect of modern architecture. How do you incorporate sustainable practices into your projects, particularly in the context of Zimbabwe and Africa?

A: Sustainability is a very topical issue now and for the future. In our practice, we make an effort to maximise the use of local materials and ensure contractors source them locally. We focus on using these materials as much as possible and design building forms to optimise natural ventilation and lighting. This approach reduces fossil fuel use and minimises mechanical ventilation, leveraging Zimbabwe's favourable climatic conditions. We also pay special attention to recycling and waste management, incorporating greywater systems and water harvesting where feasible.

Solar energy is another key component of our strategy. Depending on the project's size and scope, we aim to introduce solar farms with the potential to feed into the national grid eventually.

Additionally, we emphasize on vegetation and microclimatic controls, utilizing water features and greening the environment as much as possible to enhance the landscape.

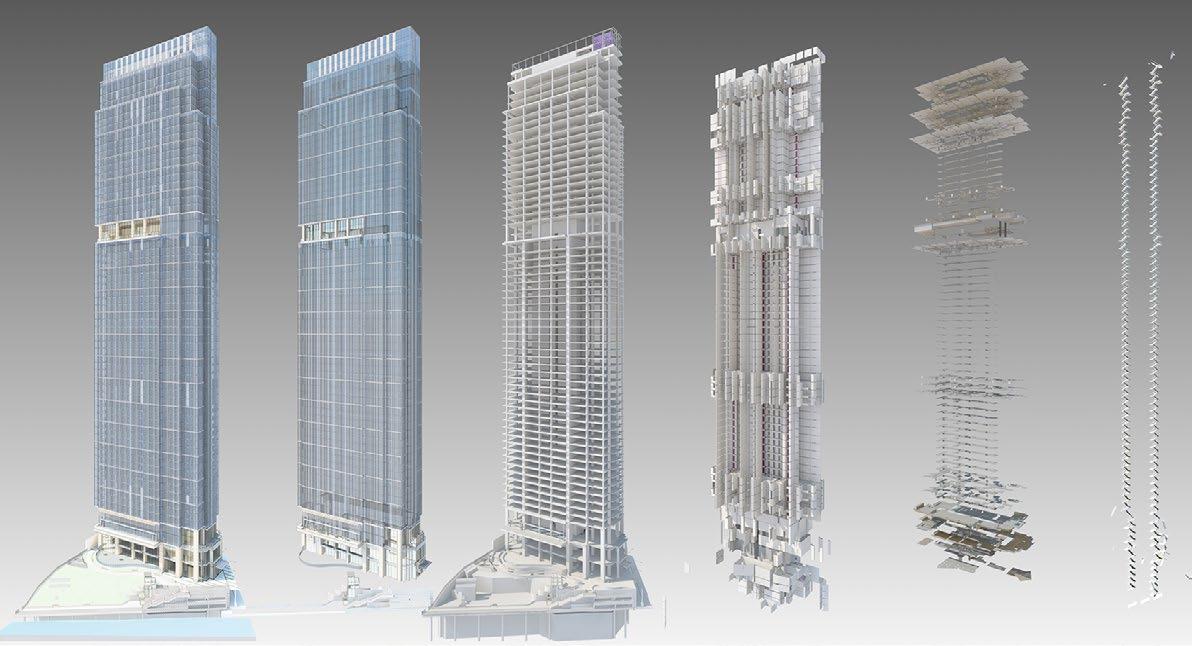

Q: How have advancements in technology, such as Building Information Modeling (BIM) and 3D printing, influenced your architectural practice? How do you feel about these new tools in general?

A: BIM technology has a positive contribution to the architectural practice in terms of project performance, accuracy, and reduced errors where there's repetition. It streamlines the design to the construction planning process and project management, improving collaboration and communication with different stakeholders such as Engineers, Quantity Surveyors, and Contractors

It’s a very positive attribute to the digital transformation of the construction industry which we have adopted in our dayto-day architectural practice. However, due to the project program timeline management, has lessened the architects’ artistic approach of free-hand sketching.

One comes up with an idea, draws a couple of sketches quickly, and straight onto the computer. So instead of pushing through with the free hand ideas and seeing the options that you have by free hand, one quickly migrates to the computer. That's reducing the free-flowing freehand artistic approach. I would say that's the downside of it.

However, in my architectural office, we have incorporated the use of iPads and Tablets which has allowed the design team to enhance their artistic approach of freehand sketching on a digital scale.

Q: You have received numerous awards throughout your career. Which recognition has meant the most to you and why?

A: The awards I received were lovely and unexpected surprises. The first one was the ZNCC Women in Enterprise award. When they asked for my CV, I sent it without thinking much about it, and then I went to the event and found that I was nominated for first runner-up. In the following year, they asked me again, and I won in the construction category,

which was great. In my view, there were some notable brands I recognized and had seen out there that could have qualified to receive the award.

So, it was gratifying to be chosen for these awards. Then the Institute of Architects Award, was recognizing my tenure as president. Being recognized by fellow architects for what I contributed to the office of the president was extremely gratifying as well because I was representing some really intelligent, smart, and creative professionals, and they recognized my contribution to the fraternity as having some significant impact. That was pleasing, hence I'm very grateful.

Q: Congratulations on being on African Columns’ Top 50 Architects list. How do you feel about that one?

A: I received an email from Tom Ravenscourt, who introduced himself as a co-author of an R.I.B.A. book that they wanted to publish on global women architects. At the time of introducing himself, he was confirming if the building he saw in the Institute of Architects Yearbook was ours, to which I confirmed. He said he found the building interesting and wanted to interview me about my architectural inspiration. That's how that selection came about.

The feeling of being recognized as a woman architect who was making some impact on the architectural landscape was phenomenal. It really was a lovely and wonderful surprise.

Q: Are there any upcoming projects or initiatives that you are particularly excited about and can share with us?

A: I am always excited about new work, regardless of the scale. However, due to client confidentiality, I can’t share specifics

until projects are completed and clients are comfortable with publicity. What I can tell you is, we treat every project, big or small, with the same level of attention and detail.

Q: What emerging trends in architecture do you foresee having a significant impact on the African architectural landscape in the next decade?

A: Just like everything else, architecture hasn't been spared from AI. The world is now a global village. Design trends from the Western world, Eastern world, and beyond are creeping into our African context. However, I still believe that the African landscape has much to offer from its own basics of understanding architecture.

In urban areas, there seems to be a proliferation of architectural work, but on a larger scale, it's still a far cry from what it could be. Architectural opportunities in Zimbabwe, let alone Africa are so many as we have not even scratched the surface. We are still on the margins of showcasing our impressions of vertical

developments and their necessity on the African landscape. There are a lot of opportunities to develop solutions for our landscape that integrate both the growing communities and uphold the beautiful environment.

Technological advancements are coming to schools of architecture, where students are quickly moving from learning design principles to dealing with smart buildings and advanced technology. Yet, the economic environment presents challenges. Developers might be able to afford these new technologies, but the market they serve often cannot.

We're stuck between meeting new architectural trends and smart technologies while still catering to basic needs. The world doesn't stop while we wait to address these basics. So, there's a fine balance to be struck between adopting trends and providing architectural solutions that respond to the population's needs.

We're in a very interesting phase of transition in the next decade. It will be cutthroat, requiring designers to consider the environment, the market, and technological advancements. Balancing all these factors is crucial.

Q: Reflecting on your career, what key pieces of advice would you give to young, aspiring architects entering this profession?

A: Looking at my career journey, I would say that what's of critical importance is maintaining professionalism, knowing your product, and knowing when to take the time to think about what you're proposing, especially when you're onsite and brainstorming ideas. It's essential to understand how to create something that can be constructed.

The canvas is vast. Don't be afraid to push the boundaries in terms of design, but ensure that what you're putting on paper can be translated into a structure that will stand the test of time. Safety is paramount, as are aesthetics and buildability. I encourage young architects, especially those who come through my office, to explore as much as possible when they're just starting out. Travel, and see different architectural styles and environments, because every environment influences your architectural vocabulary.

Understand your environment, go out, explore, and have fun in the process, but always maintain your professional integrity. In this new era of sustainable designs, study what works, learn from precedents, and think about how you can improve on them. There's a lot more for youngsters, especially with this technology that's now readily available to them. Literally, the world is their oyster.

“The human touch is still necessary because AI doesn’t catch the nuances of the human aspect of things.”

Structure and Design and Bokani Munodawafa discuss the potential of AI and machine learning in the architecture industry, particularly in Africa. Munodawafa, an architect himself, highlights the slow adoption of new technologies and the potential for AI to streamline the design process, improve communication, and provide valuable insights. He also shares his experience with BIM model software and the integration of technology in architecture, focusing on the challenges and opportunities presented by implementing new technologies. These include the need for resources, compatibility issues, and ethical considerations.

Q: How do you feel about the whole AI/ML phenomenon in general?

A: I think it's great. Humanity has to evolve, and AI is a progression of our ability to do things efficiently, especially with machine learning. It's a steep progression, which is somewhat scary, but also quite impressive. We can only imagine how much more humanity can achieve with such drastic advancements in AI and machine learning.

Q: How do you see AI and ML impacting Africa’s architecture industry in the next 5-10 years?

A: I think a 5 to 10-year period is too short for Africa to see noticeable change. We are generally slow to adopt new technologies and trends. We’ll likely sit back and observe how the first world handles these advancements before adopting them ourselves. Only early adopters will be able to maximise on these AI advancements, and I don’t see any significant impact on the overall African market within that time frame.

Q: What specific new technologies or software are you currently using or interested in exploring in your architectural practice? Can you share examples of heavily tech-integrated projects you have worked on, and what made them successful?

A: At SBM, we predominantly use ArchiCAD. It’s a versatile tool that allows us to create detailed drawings and integrate various services into a Building Information Model (BIM). The BIM model can store all necessary project information, with endless possibilities. It enables us to publish a model viewable by the entire project team, clients, and contractors, enhancing understanding in both 3D and 2D.

Each element within the model contains detailed information such as materials, finishes, and volumes, and we can include manufacturer specifications and costs.

For rendering, we use 3ds Max and V-Ray. Recently, we’ve started using Chaos Vantage, a new software that utilises V-Ray technology to create animations and images at lightning speed by harnessing the power of the GPU. This shift from traditional CPU rendering has enabled us to achieve impressive results with real-time rendering, making the design process more efficient and streamlined.

We are also exploring AI technologies. For example, there are tools that automate the design of car parks by generating layouts based on given parameters. This saves time on tasks that would otherwise be labour-intensive. AI can also assist in detailing sections of a project, which is incredibly powerful. We’re moving in this direction but haven’t fully explored these tools yet.

In projects where we have used BIM software, it has greatly improved the understanding of the building for the project team and contractors. Typically, contractors receive multiple drawings and need significant time to understand a design that took a year to develop. A BIM model simplifies this process, allowing contractors to easily refer to it if they have questions.

Q: Do you think technology can ever replace architects, and if it gets to that, what new skills will be required?

A: I don't think technology will replace architects; it will aid them, but not replace them, at least not in our lifetime. The human touch is still necessary because AI doesn’t catch the nuances of the human aspect of things. There are also issues with liability and legislation that need to be addressed. AI will aid architects but not replace them entirely.

Q: What challenges do you face as an architect in implementing new technologies, and have you found a way around them?

A: Technology requires resources, and without sufficient funds, adoption is challenging. For example, Chaos Vantage requires a powerful graphics card, such as the RTX 4080, which is expensive. Without such resources, we can’t use the program effectively. Additionally, all stakeholders need to buy into these technologies, which isn't always easy. Compatibility issues with other programs also pose challenges, but we find ways to integrate various elements, even if it means additional work.

Q: How do you balance technological advancements with sustainability, energy efficiency, and environmental considerations?

A: Balancing these aspects is quite broad and challenging, especially since we don’t have a Sustainability Council or a barometer to measure sustainability effectively. However, we are working on projects that aim to meet green requirements with the help of consultants. It’s a steep learning curve, requiring resources and legislative support, which is easier in first-world countries. We leverage what we have available in our country and adopt a sustainable approach to design in general. Each project is different, but small sustainable design practices help us tick those boxes from the start.

Q: Are there any ethical considerations when using AI and ML in architecture?

A: I’m not sure about machine learning in architecture specifically, but AI does raise ethical issues. AI learns from old data, which can present ethical challenges. Legislation will need to evolve to address these issues. However, a new generation will likely find ways to handle these ethical considerations effectively.

It’s a new era filled with innovation and experimentation for architects. Responding to the challenges of the 21st century, designers and architects are coming up with new approaches that are reshaping the way the built environment is conceived, constructed and experienced.

One of the foremost trends in architecture today is the embrace of sustainability and environmental consciousness. Driven by the pressing need to address climate change and reduce our ecological footprint, architects are incorporating sustainable design principles into their practices. This includes the use of renewable materials, energy-efficient

text by Farai Chaka

building systems and innovative techniques that reduce resource consumption and waste. From the integration of solar panels and green roofs to the exploration of biomimicry - where natural systems inspire architectural solutions—the new wave of sustainable architecture is all about what it means to build responsibly.

In addition, the practice of adaptive reuse is gaining traction. Instead of demolishing old buildings, architects are increasingly renovating and repurposing them, preserving historical elements while upgrading them to meet contemporary standards of sustainability and functionality.

This approach not only reduces waste but also retains cultural heritage and fosters a sense of continuity within urban landscapes. However, some architects argue that as land value increases in comparison to building value, sites that would have been cheaper to renovate in the past may now be more affordable to demolish and rebuild.

Digital technologies are revolutionising the design and construction process. The rise of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and parametric design software has empowered architects to create highly complex and intricate forms, pushing the boundaries of what is physically possible. These digital tools allow for precise simulations, optimisation and the seamless integration of various building systems, resulting in structures that are not only aesthetically striking but also highly efficient and adaptable.

Furthermore, advancements in construction technology, such as 3D printing and robotics, are beginning to change the way buildings are constructed. 3D printing allows for the creation of bespoke architectural elements with minimal waste, while robotics can perform repetitive and precise tasks, reducing human error and accelerating construction timelines.

These technologies are contributing to a more efficient, cost-effective and sustainable construction industry.

The integration of emerging technologies, such as augmented and virtual reality (AR and VR), is transforming how architects engage with clients and the public. These immersive platforms enable architects and designers to create interactive experiences, allowing stakeholders to visualise and navigate proposed projects before they are built. This not only enhances communication and collaboration but also facilitates a more inclusive design process, where clients’ needs and preferences can be better incorporated.

There is also a growing emphasis on human-centric design when designing buildings. Architects are increasingly focusing on the well-being and lived experiences of building occupants, creating spaces that prioritise comfort, mental health, and social interaction.

This shift is evident in the design of workplaces, healthcare facilities and residential spaces, where features like natural light, biophilic elements, and flexible layouts are being prioritised to create a sense of connection.

The new types of architecture are embracing diversity, inclusivity, and cultural sensitivity. Designers are actively engaging with local communities, incorporating their narratives and respecting the unique contexts and histories of the places they work in. This approach has led to the emergence of projects that celebrate cultural identity, challenge traditional building typologies and create spaces that are more accessible and representative of the diverse populations they serve.

This inclusive mindset is also evident in the push for universal design, which aims to create environments that are usable by all people, regardless of age, disability or other factors. By prioritising accessibility and inclusivity, architects are seeing to it that the built environment serves the needs of all members of society.

As the architectural profession continues evolving, it is clear that the new modes of architecture will not just be about aesthetics or technical expertise, but about redefining the very purpose and impact of the built environment. By concentrating more on sustainability, embracing digital technologies, catering to human well-being and advocating for inclusive design, architects are shaping a future where buildings and urban spaces are not just functional, but also meaningful, adaptable, and responsive to shifting needs.

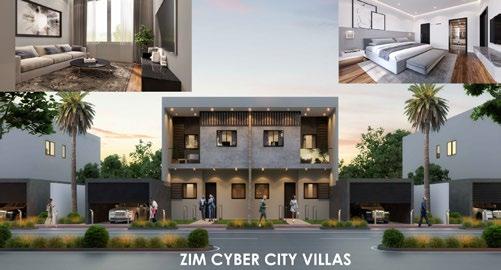

Text by Farai Chaka Renders by Zim Cyber City

In a few years to come, the integration of advanced technologies in the architectural practice will no longer be optional but rather extremely imperative. Architects will be better placed incorporating digital technologies and strategies across all aspects of their operations to stay competitive and relevant. From virtual reality (VR) to Building Information Modeling (BIM), cloud computing, and time-tracking tools, the architectural, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry is on an interesting transition. This shift is not all in all about adopting new tools but about embracing a cultural change that leverages technology to enhance project outcomes and efficiency.

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in their 2024 Artificial Intelligence Report emphasises that digital transformation extends beyond technology adoption. RIBA states that it represents a fundamental shift in culture, facilitated by technological advancements, to create better buildings, improve client outcomes and streamline workflows. This shift is evident in the growing use of technologies such as VR and BIM, which enable architects to deliver more accurate, coordinated, and visually compelling projects. Architects have never had more freedom and versatility in their designs.

Here are some of the new technologies that architects should consider incorporating in their daily operations:

Building Information Modeling (BIM)

BIM has transformed the AEC industry by providing a comprehensive digital representation of a building’s physical and functional characteristics. Speaking on BIM, Bokani Munodawafa of SBM Architects says, “In projects where we have used BIM software, it has greatly improved the understanding of the building for the project team and contractors. Typically, contractors receive multiple drawings and need significant time to understand a design that took a year to develop. A BIM model simplifies this process, allowing contractors to easily refer to it if they have questions.”

By facilitating better communication and understanding among stakeholders, BIM reduces errors, minimises rework and ensures that everyone is on the same page. This technology not only improves project coordination but also enhances the efficiency and quality of the final product.

Virtual Reality (VR)

Virtual reality is another turning point in architecture. Virtual reality allows architects to create immersive, interactive 3D models of their designs, providing clients and stakeholders with a realistic preview of the final product. This technology enhances the design process by allowing for real-time feedback and modifications so that the final design meets the client’s expectations and needs.

3D printing will definitely become a pivotal tool in architecture. 3D printing facilitates the rapid and precise fabrication of prototypes and intricate architectural elements. By enabling the designing of complex geometries that traditional methods struggle to achieve, it opens up new realms of design possibilities making way for peak creativity and innovation in architectural projects. This advancement not only enhances the aesthetic and functional aspects of structures but also significantly reduces production costs and time.

The integration of AI in architecture is rapidly becoming widespread and it can only propel the practice forward. AI can automate routine tasks, optimise design processes and provide insights based on vast amounts of data. This technology should not be viewed as a threat but as an opportunity for architects to enhance creativity and efficiency. AI can assist in generating design options, predicting project outcomes, and identifying potential issues before they arise.

On the other hand, Bruce Rowlands of ArchitextureSpatial Design provides an interesting take on AI in architecture: “In 100 years’ time, a poorly designed chair hand-crafted from solid oak will be more valuable than an AI-designed IKEA chair that is machine-made of plastic. Why?

I’m not sure; perhaps because it has a relatable human ‘back-story,’ so humans are more moved by it. Or because solid oak is rarer than plastic.”

This brilliantly underscores the enduring value of human touch and craftsmanship in architecture, even as we embrace technological advancements.

The efficiency gains from these technologies are unmatched. Advanced digital tools streamline workflows, reduce manual labour and lower the barriers to entry for younger architects. This popularity in design tools means that innovative and original designs, particularly those inspired by cultural heritage, will become more accessible.

For instance, Zimbabwean architects can now more easily incorporate elements of African heritage into their designs, creating unique and culturally significant buildings.

Again, these new tools also make for better connections between architects and clients than has ever been experienced before. Through enhanced visualisation tools and collaborative platforms, architects can engage clients more directly, incorporating their feedback throughout the design process.

In this interview feature, Bruce Rowlands of Architexture

Spatial Design shares the influences that shaped his path, from an unexpected start at the University of Cape Town to the inspiring work of local thatcher Terrance Bragge. He goes into his design philosophy, emphasizing the importance of working with available resources and the artistic instinct developed through hands-on creation.

Rowlands also reflects on the evolution of architectural education and practice in Zimbabwe, advocating for a balanced blend of technical skills and artistic creativity.

Q: If you had not pursued a career in architecture, what other profession do you think you would have chosen and why?

A: Music composition. Why? It was just something I used to do when I was much younger. I liked telling stories with lyrics and music.

Q: Your architectural journey began with a degree from the University of Cape Town. What inspired your decision to enrol for an architecture degree?

A: Last minute panic. I had not given university any thought, and when my friends started signing up, I just photocopied their application forms and copied what they were doing.

Q: Who in the world of architecture has inspired you the most and how has their work influenced your design philosophy and creative process?

A: I grew up near Terrance Bragge, a brilliant thatcher, who could pull a house out of a rocky mountainside as if it had spontaneously grown there. For us kids, his creations were not buildings: they were adventures.

Q: You blend functionality with aesthetic appeal. Can you elaborate on your design philosophy and what influences your creative process?

A: We work with what is readily available. It's a bit like painting a picture. Once we have studied and understood the site, we have our "canvas". Once we have a good grip on what materials and skills are at hand, we have our "limited palette". Once our client brief is clear, we have our "content", and then we just play with concepts until the overall composition "clicks".

Q: Looking at the architectural education currently being offered in Zimbabwe, what changes or improvements would you advocate for to better prepare future architects?

A: Prioritise that students work with their hands; sketch, paint, sculpt, model – this is where you build up your artistic instinct. Anyone can learn to operate software to "draw something up neatly", but to solve a 3D puzzle artistically requires more than technical skill.

Q: One of your award-winning projects, The Gota Dam

Residence, is a unique project set on a granite rock. Can you briefly share insights into the design and construction challenges of this project?

A: Vision, perseverance, and teamwork. Those are the main ingredients required to see an ambitious vision through to completion. There is nothing that ego or "artistic temperament" can help you with on a real project – so don't bother bringing them along. The Gota Project was completed during Zimbabwe's most difficult economic years. It was actually conceptualized by a very talented London design firm, and our role was to adapt their vision to make it possible to construct on an incredibly difficult site, in the middle of history's worst hyperinflation. I believe that it was working within these very harsh constraints that actually forced the project's creative originality.

Q: Having contributed to both residential and commercial projects, which type do you find more fulfilling and why?

A: Commercial projects are much easier and are great fun; they come with enough resources to warrant large and loud "brush strokes". But residential projects, whilst being more challenging, are far more satisfying; it's more about serving the needs of a family than making a corporate statement. Because a residence is highly personal, the families engage more deeply with the process – and it feels as though the resulting spaces have a longer-lasting impact on their lives.

Q: Can you tell us about a project that you are particularly proud of and why it stands out to you?

A: For reasons mentioned above, I'm proud of all the private residences; not that they are all equally architecturally photogenic, but because they are about more than architecture, they are about family. They often represent a client's most meaningful and significant personal investment. Aside from residences, we have done several schools and an orphanage. Because of budget constraints, they may not stand out in our portfolio as obvious examples of stunning architecture, but I am extremely proud of the fact that they provide a happy space for children.

Q: How do you stay inspired and continue to innovate in your field?

A: I personally lack "big-picture" vision, so I jump at any opportunity where I recognize this gift in a client. With their vision and my puzzle-solving abilities, we make a good team. I am very careful to recognize all the different natural aptitudes of our staff, and try to give them free range when they're operating in their areas of strength. This opens up the possibilities of innovation way beyond what I could do on my own.

Q: In what ways has the architectural landscape in Zimbabwe evolved since you started your career?

A: When I started, there was very limited access to local examples of great design. Now, with online access to great

international architecture, Zimbabweans have developed a taste for far more adventurous design solutions. Also, cautioned by so many unfinished house ruins littering the suburban hillsides, I have found Zimbabwean clients are now far more likely to spend time with an architect on perfecting a smaller, more efficient plan than launching recklessly into an oversized, under-thought mistake.

Q: What emerging architectural trends do you foresee having a significant impact on the African architectural landscape in the next five years or so?

A: As mentioned above, it's becoming too expensive to waste labour and resources on building mistakes, so careful, efficient planning will (I hope) begin to trump wild showboating. Also, I've noticed that as land value increases relative to building value, sites that would have previously been cheaper to renovate will start to become cheaper to demolish and build new.

Q: As an architect, how do you envision the role of public spaces in urban settings, particularly in the context of Zimbabwe's growing cities?

A: In our context, I think that as long as the overall city zoning is professionally thought out, the details of each public space are best governed by the community that uses it. The

community, if incentivized or at least allowed the freedom to manage the public space, will probably evolve more practicable and relevant solutions than those thought up by remote "social designers".

Q: Are there any upcoming projects or initiatives that you are particularly excited about and can share with us?

A: We have just completed phase one of USAP Community School, a new school for exceptionally gifted students. Watch this space for future world leaders.

Q: You have your own architectural firm, Architexture Spatial Design. How do you mentor young architects and what advice would you give to those entering the profession?

A: We take interns on their gap year, and throw them in the deep end. They are selected purely on the merit of their portfolios, so we know they have the raw talent to contribute value. Our experienced staff supervise their work, keeping a safety buffer between them and actual on-site demands.

Advice? If you love sitting and drawing for hours on end and the time flies by without you noticing, then this job is for you. If you don’t, then it’s not.

text by Farai Chaka

The advent of new innovative materials holds significant promise for those in construction and architecture. These materials are not only innovative but also align with the continent’s unique environmental, economic, and social contexts. Exploring these materials can lead to more resilient, efficient and aesthetically pleasing structures as urbanisation accelerates and sustainability becomes of the essence.

One of the most exciting developments is the use of cross-laminated timber (CLT). Cross laminated timber is an engineered wood product made by layering timber at an angle, creating slabs that are considerably strong and versatile.

For African countries with abundant forest resources, cross laminated will offer a sustainable alternative to the traditional concrete and steel. It provides excellent thermal insulation, reduces carbon footprints and makes for faster construction times.

On top of that, if done right, its aesthetic appeal, with natural wood finishes, can enhance the integration of buildings into their surroundings, promoting a harmonious balance between built and natural environments.

Another material gaining traction is rammed earth. This

ancient technique has been brought back into the fold with modern engineering to create durable, energyefficient structures. Rammed earth involves compacting a mixture of earth, sand, and a stabilising agent, such as cement or lime, into molds. The resulting walls are not only robust and thermally efficient but also have a distinct, organic look. As traditional building materials become more expensive, rammed earth presents a cost-effective and environmentally friendly solution. Its use can reduce the reliance on imported materials and support local businesses by utilising readily available resources.Complementing these materials is the innovative use of recycled plastics in construction. With plastic waste being a significant environmental issue everywhere, repurposing this waste into building materials offers a dual benefit.

Companies are now producing plastic bricks and panels that are not only strong and durable but also resistant to water and pests. These materials can be used in various ways, from low-cost housing to infrastructure projects, providing a sustainable alternative to conventional materials while addressing waste management challenges. Furthermore, the integration of nanomaterials into construction is opening new possibilities. Nanomaterials, such as graphene, enhance the strength, durability and functionality of conventional building materials. For example, grapheneenhanced concrete is significantly stronger and more crack-resistant, extending the lifespan of structures and reducing maintenance costs.

While still in the early stages of adoption, the potential

of nanomaterials to move forward construction practices in Africa is immense, particularly in countries like Kenya, South Africa and Mozambique prone to harsh weather conditions and natural disasters.

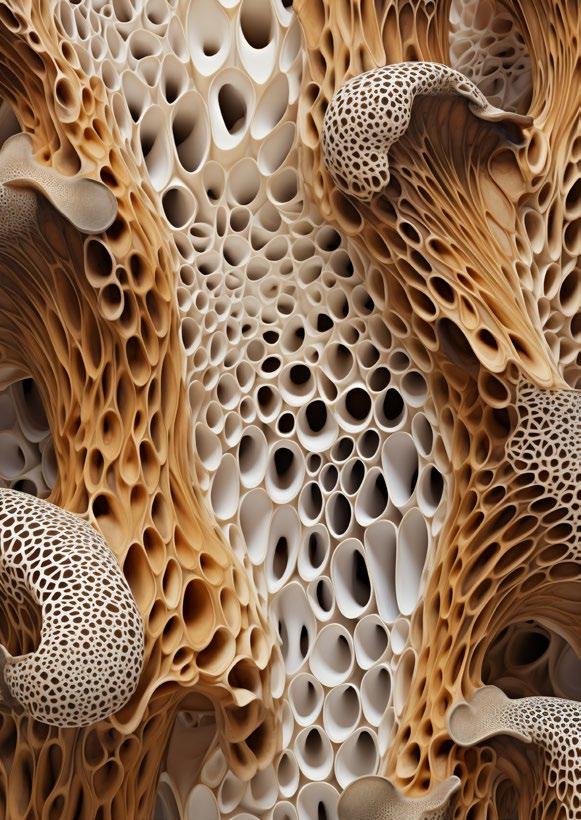

In the quest for sustainable and resilient construction, bio-based materials are also making strides. Materials like mycelium composites, derived from the root structure of fungi, are being developed into biodegradable building blocks and insulation.

Mycelium is lightweight, fire-resistant, and has excellent insulating properties. Its use not only reduces the environmental impact of construction but also supports the development of circular economies, where materials are continuously repurposed and regenerated. Biobased materials like mycelium can offer a path towards greener and healthier built environments for African nations committed to sustainable development .

Finally, the adoption of 3D printing additive technology in construction is poised to revolutionise the industry.

3D printing allows for the creation of simple or complex structures with minimal waste and reduced labour costs.

Where rapid urbanisation demands quick and costeffective housing solutions, 3D printing can produce homes and infrastructure at unprecedented speeds. Moreover, 3D printing technology offers design freedom and customisation options, enabling architects and engineers to easily bring innovative and sustainable designs to life.

The adoption of these new materials can play a huge role in shaping the future of its built environment as Africa continues to grow and urbanise. Even as officially integrating these materials into mainstream construction practices will require ongoing research, investment and collaboration across sectors, the potential benefits are clear. Above all, these new materials will reduce the cost of building structures considerably.

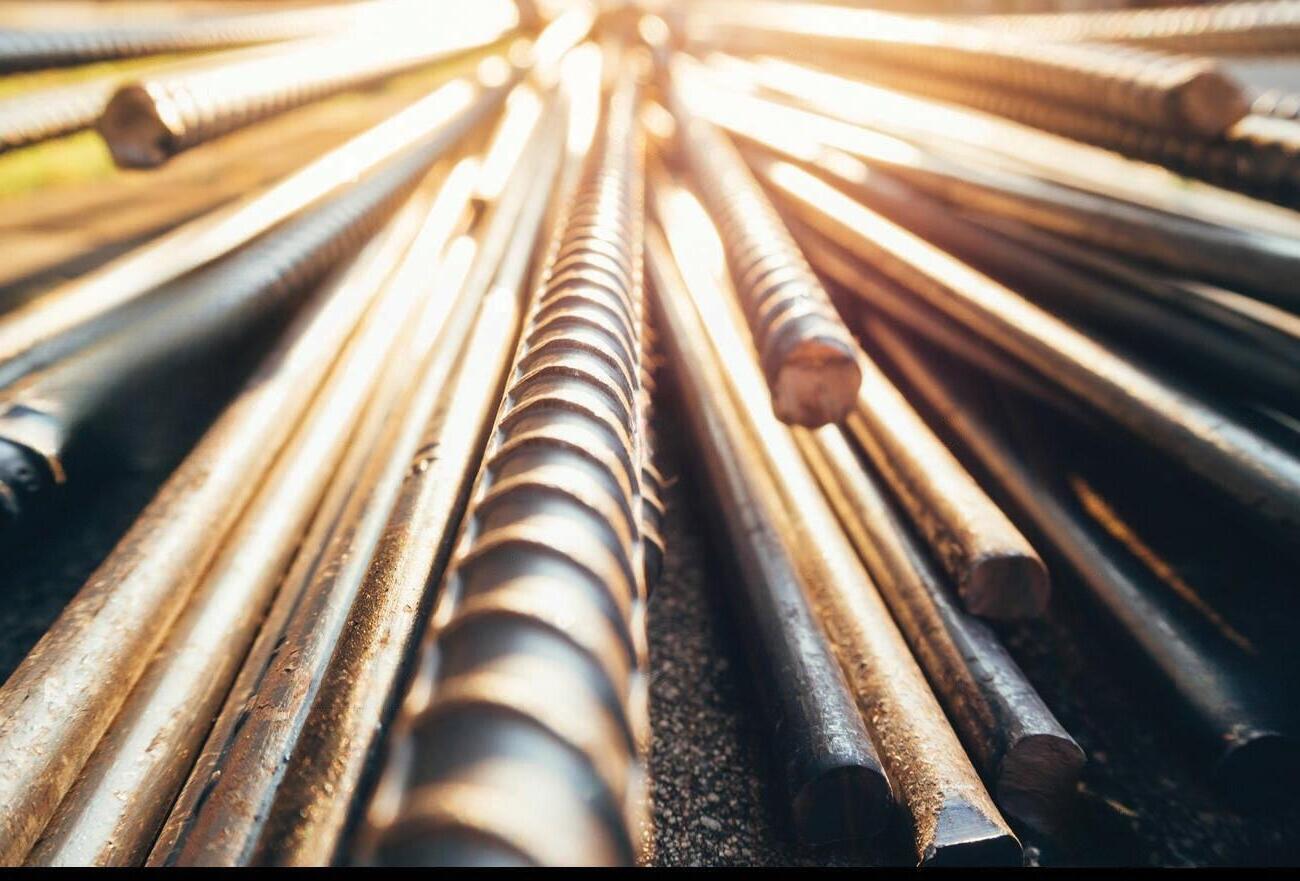

•IPE Services

• Roofing

•Deformed Bars

•Fencing

•Flat Sheets

•Accessories

•Round Tubes

Arch Banda M. BAS, B Arch (NUST) Metamorphosis AIDPM

74 Selous Ave (Btw 7th & 8th), Harare 024 (2) 792802 0772251345 masauso@metamorphosis.co.zw

Arch Beattie R.H.S. BArch (Hons), Dip Arch (Mackintosh), RIBA, ACIArb Stone / Beattie / Munodawafa Architectural Studio

39 Arcturus Road, Highlands Harare 0242496342 0242497342 0779 659 400 0777463244 richard@sbmarchitects.com

Arch Chibika K.A, MSc Arch, Bsc Hon Arch Chibika Architect

Suite 8, Lonhro Building, Corner Nelson Mandela Avenue/ 3rd Street, Harare 0777821112 kchibika@gmail.com

Arch Chiwara S. Msc Arch, Bsc Hon Chiwara S Architect

2166 Tokwane Close, New Marlborough, Harare 0777510806 samuel.chiwara@gmail.com

Arch Chombe T. BAS (Hon) (NUST) M.ARCH (NUST) Fluidity Design Studio (FDS)

9th Floor West Wing, Bard House, 69 Samora Machel Avenue Harare 0717205826 0772776986 teejaycee70@gmail.com

Arch Claypole M., BArch (Natal) Architectural Planning Studio (APS)

17 Balmoral Road, Borrowdale, Harare 0776667332 mark@architecturalplanningstudio.com

Arch Cochrane G., BAS (UCT) MArch (NMMU) Architectural Planning Studio (APS)

17 Balmoral Road, Borrowdale, Harare 0776667332 0772143314 graham@architecturalplanningstudio.com

Arch Da Cunha Jose Luis Pinto Dip Arch (Brazil) Diagraphis Architects

541 Brooke Drive, Borrowdale Brooke Harare 0775842669 0712200716 0777959060 jolumapicu@gmail.com

Arch Dzimwasha S.J B Arch M Arch (NUST), (PMP) (PMI-ACP) J. Dzimwasha Architect

No 4. Meredith Drive, Eastlea, Harare 0772309290 08677212069 shingi@jdazimbabwe .co.zw

Arch Dzinotyiwei G. B.Arch MCPUD Mugedeza TAJ Architect

21 Northampton Crescent, Eastlea, Harare 0242746524 0772211100 gdzinotyiweyi@gmail.com

Arch Dzvukamanja T.E. B Arch Hons (UCT); BAS (UCT) Studio Arts Inc

4 Kempden Close, Borrowdale, Harare 0242885820 0242885763/ 93 0772300287 tsitsidzvuk@gmail.com

Arch Fox Geoff - BAS M Arch (UCT) Architectural Planning Studio (APS)

17 Balmoral Road, Borrowdale, Harare 0776667332 0779659597 geoff@architecturalplanningstudio.com

Architectural opportunities in Zimbabwe, let alone Africa are so many as we have not even scratched the surface

If you love sitting and drawing for hours on end and the time flies by without you noticing, then this job is for you. If you don’t, then it’s not.

Bruce Rowlands

Arch Gacic M. Dip Arch (Belgrade) Archiplan Architects

19 Natal Road (gate from East Road) Avondale. P.O. Box 5105 Harare 0242332043 0772773377 0772773377 0733300700 archplanzimbabwe@gmail.com aahreoffice@gmail.com

Arch Gumbo R. BAS. B Arch (NUST) Up North Architect

Suite SW09 No 1 Adylinn Road, Marlborough Harare 0242312022 0772814273 architectupnorth@gmail.com

Arch Gura I. BAS, B Arch (NUST) Gura and Associates Architect

Stand No 1019 Off Nursery Road, Mt Pleasant Harare 08677114688 0772265543 0719265543 igura@gaazim.com ishumaelgura@gmail.com

Arch Gwenure G. Barch (Hons) M Arch (NUST) Gwenure Gede

72 David Livingstone Harare 0772518185 gwenzo76@gmail com

Arch Honde T B Arch, BAS (NUST), M.Arch. (EMU- Cyprus) Studio 5 Architects

No 5 Chaifont Rd, Greencroft Harare 0242332987 0772807122 hondet@studio5architects.com admin@studio5architects.com

Arch Kamwaza M. BAS, B. Arch (NUST) Memorage Architecture

1826 Area D, Westgate Harare 0772778566 memoragearchitecture@gmail.com

Arch Kanyanta C B B A Hon Arch, Dip Arch Architrave Design Group

4 Hill Road, Highlands, Harare 242443311 0772232185 adjzim@gamil.com

Arch Kawadza R., BAS M Arch (Natal) Rumbidzai Kawadza

1A Stewart Road, Greendale Harare 0775859509 rumbi.laura@gmail.com