Recognized as a pioneer of Narrative Art, Bill Beckley (Hamburg, Pennsylvania, 1946) was one of the first artists to use photography as a means of expression in the context of painting and sculpture, by juxtaposing images with writing.

This book, edited by Studio Trisorio, Naples, tells the evolution of his work through a selection of more than one hundred works of art and is enriched by critical texts of David Carrier and Andrea Viliani. Furthermore, in an insightful conversation with Laura Trisorio, Beckley retraces the salient phases of his career and describes some of his most iconic works through anecdotes that embellish the story and reveal the working method of a conceptual artist.

Bill Beckley’s works are in the most prestigious international museums and art collections including the Museum of Modern Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and Sammlung Hoffmann in Berlin.

BILL BECKLEY AND NARRATIVE ART

9 7 8 8 8 9 2 8 2 2 6 6 5 euro 50.00

Bill Beckley

To my sons Tristan and Liam, To my dear friends Laura Trisorio and Gianfranco D’Amato, In memory of Pasquale Trisorio who I last saw walking in late afternoon sunlight, beside the bay of Napoli

Bill Beckley and Narrative Art

The Word-Image Riddle and the Aesthetics of Beauty

“Bill Beckley” David Carrier

Chapter One – Entry Points

Chapter Two – The Word-Image Riddle

Chapter Three – The Aesthetics of Beauty

Chapter Four – Neapolitan Holidays

Works

From the 1960s to the 1970s

From the 1970s to the 1990s Stems

Neapolitan Holidays, 2019

Florilegium: A Story of Art, as Told to Us by Bill Beckley Andrea Viliani

A Conversation Bill Beckley Biography

6 7 47 137 197 21 59 157 207 228 237 246 264

Contents

of Works

List

“Bill Beckley”

David Carrier

Chapter One Entry Points

We’re looking at Myself as Washington (1969). This small black-and-white photograph shows Bill Beckley dressed up in formal, old-fashioned clothing with talcum powder sprinkled on his hair. It’s a seemingly straightforward picture with a familiar subject. Every American school child has seen Gilbert Stuart’s various paintings of George Washington. And so, initially it’s not hard to recognize what’s going on here. Beckley made a photographic self-portrait imitating one of those paintings. In truth, however, the young Beckley doesn’t look very much like those images of Washington, who is shown as a much older man. Sometimes movie actors transform themselves elaborately to play roles. But here Beckley doesn’t try to elaborately make himself up. And so it’s unclear how to understand this image. Without the title it wouldn’t make sense. Reflection is required to make sense of Myself as Washington

President Washington was famously supposed to have said, “I cannot tell a lie.” Since this statement itself is, so it turns out, a lie concocted by an early nineteenth-century writer, maybe it’s appropriate that here Beckley has constructed a photographic visual lie. At least, that’s the case if we take him to be George Washington. Remove the title and we have here a photograph involved with play-acting. Then, considering the artwork to be the photograph plus its title, we have what might be an allegorical commentary on late 1960s American politics. When Richard Nixon was elected, questions of lie telling by the American presidents were very much in the news. From Washington to Nixon, leftists said that too often presidential lies were as American as apple pie. Maybe, then, Beckley is making an elliptical political statement about the untrustworthiness of American presidents. They tell lies, as does his photograph.

Fourteen years after Beckley made this photograph, my first book, co-authored with Mark Roskill, Truth and Falsehood in Visual Images (1983) took up this very topic, the relationship between true statements and falsehoods in art. And so, it’s unsurprising that I was (and am) much taken by this photograph. As a young conceptual artist, Beckley makes a sophisticated statement. To identify Myself as Washington as a visual falsehood is suggestive but misleading. More exactly, it’s false if you wish to be clearer. For Beckley doesn’t present himself being our first president,

7

but rather truthfully says that he is posing as Washington. No lie is involved. He doesn’t aim to deceive us into thinking that this is a photograph of Washington. It’s an image of Beckley engaged in an act of pretending.

Still, this implied assertion itself, “I show myself as President Washington” is, once we reflect, surprisingly complicated, at least if we take it in a literal minded way. Here we have a form of visual metaphor, treating one person, in some way, like another. Given the photograph of Beckley and the title, we look for similarities between Beckley and George Washington. As Arthur Danto says in his treatise of aesthetics, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace (1981), metaphors set the viewer’s mind in motion, asking that we identify these similarities. That’s a natural way of understanding the significance of the word “as” in the title. Beckley asks that we seek similarities between his appearance and that of our first president. Were the work’s title Myself as Wittgenstein, we would simply be puzzled, for Beckley doesn’t look anything like that philosopher. But Beckley dressing up with his clothing and hair so that he looks a little bit like Washington. He is, if you will, like an actor who plays someone that he could not readily be confused with.

Myself as Washington works as an artwork because there are some vague similarities between the appearance of the two men. Both are white male adults. Beckley couldn’t plausibly present a photo entitled Myself as Mao. But maybe he looks a little like a very young George Washington, as we might imagine him. After all, the Stuart Gilbert paintings portray the president as an older man. As I said, metaphors ask us to look for similarities. When Andy Warhol did the photograph Self-Portrait in Drag (1981), he cross dressed to play that part. A person can be said to be like a donkey if they’re stubborn, like bamboo if they’re supple or like an oak tree if they’re unyielding. But being told that a person is like a light bulb is a conversation stopper, because it’s not easy what similarity is being identified. Similarly, to spell out this point, titling Beckley’s photograph Self-Portrait as a Woman would be puzzling, for he isn’t in drag.

Here it may seem as if I am commenting rather elaborately on an inherently simple photograph. And so refusing to play the game involved here in play-acting. Myself as Washington is the sort of goofy gesture that a smart young art student might make. A party invitation may say: “Come as some historical figure.” That’s the kind of game Beckley is playing. Like any good joke, it’s easy to understand but (maybe) hard to explain. Four years later, in Cake Story (1973) Beckley puzzled over the commonplace truism: “You can’t have your cake and eat it too.” Why, he asked very reasonably, would anyone have that desire, which is obviously contradictory? Here we ask another question: Why does this joke about Washington work? So far as I know, it hasn’t been much written about. And so we have to look and think for ourselves.

What makes this Beckley photograph art is, in part, the fact that it readily solicits so much discussion. Artworks exist, at least nowadays, to be interpreted. A passport photo normally just functions as an ID. No discussion is required, unless it’s a fake in a spy film. The function of Myself as Washington, it might be said, is to engage reflection. It’s no accident that Beckley would go on to teach semiotics, for even here at the start of his career we see that he was

9 8

Myself as Washington, 1969 Black and white print 20 × 16 inches (51 × 41 cm)

engaged with such linguistic concerns. Note, to take just one point, his use of the indexical pronoun, “myself,” in the title. Indexical words, “here,” “now” or “me” are tricky because their reference depends upon who is making the statement when and where. The same photograph with the title Bill Beckley as Washington would be a rather different work of art. That title indicates that it’s Beckley speaking who is to be seen as Washington. At least that’s the case if we treat that title as akin to a statement. Beckley’s title, with the indexical pronoun makes it seem that whoever makes the statement is seeing themselves as Washington. And that, like the statement about both having and eating your cake doesn’t quite make sense.

In the late 1970s, Cindy Sherman became famous for her photographic self-portraits involving play-acting. These Untitled Film Stills have been much written about. Some commentators thought that they allude to recollected scenes in particular B-movies. When that turned out not to be the case, some interpretations focused on the psycho-analytic implications of role playing by a woman. Perhaps her art was making a complex statement about gender. Women, she may be saying cannot escape role-playing. And when Richard Prince employed photographs of Marlborough Man cigarette advertisements, it was possible to look for suggestive comparisons with cinematic male role-playing. Beckley’s early photograph turned out to be part of what became an American tradition. When recently Kehinde Wiley, an artist who is African-American, presents Black youths play-acting in poses adopted for old master European painting, he works within that ongoing tradition.

By the time that Sherman and Prince took up play-acting photographs, Beckley had moved on. As we’ll see, finding a novel theme, developing it and then advancing quickly has often been his style. And since my present concern is to describe the creation of conceptual art at this time from a perspective focused on his art, Myself as Washington is a good starting point. Let’s start by placing this work historically.

Why was it the case that Myself as Washington was presented as an artwork only in 1969? Black and white photography had existed for more than a century. And so it would have been physically possible for some earlier artist to make this work. Often in art history it’s interesting to trace precedents. When was the first monochromatic work made? The first abstract painting? The first pure European landscape, as opposed to the landscapes that are behind sacred narrative scenes in Renaissance paintings?

What ultimately counts are not isolated innovations, but getting the art world to take seriously novel art forms. And premature innovations are impossible to understand. To cite one important case, when Duchamp presented Fountain (1917) and the other readymades, they gained little attention; not until the 1960s was the art world ready for these works. Nadar (1820–1910), the great French photographer whose career overlapped with that of the Impressionists, certainly had the skill to make such a self-portrait, say Myself as Napoleon. But in the art worlds of Manet, Seurat or early Matisse, it’s hard to imagine that such a gesture would have been received with interest. Nadar was acquainted with Charles Baudelaire (1821–67), who was mischievous enough to have commissioned a photographic portrait called Myself as Napoleon. But the art world of his day wasn’t ready for that work of art.

Could conceptual art like Myself as Washington have been done in NYC in 1948? In Paris circa 1910? In Rome around 1520? The further we move away from the moment when it was actually made, this becomes harder and harder to imagine. Could Poussin have been doing some conceptual art on the side? Might he have made a joking painting Myself as the King of France (1640)? I think that claim’s impossible to understand. Conceptual art couldn’t have fitted into seventeenth-century Roman artistic life because too much art had to be made before it was comprehensible. Here, then, let’s spell out what was needed.

Around 1969 conceptual art was born in New York. Three concerns are important here for our account of this birth. We will discuss the idea of an entry point, that historical moment when a new artist enters the scene and learns what is possible. We will use the concept of the artist’s brief, as developed by the art historian Michael Baxandall. The brief is the artist’s intended goal, which may be as specific as the Renaissance commission for a portrait with donors identified, or as vague as the command famously given to Pablo Picasso: “Astonish me.” And we are interested in the concept of an art world, that community of artists, critics and dealers that the artist joins. These three concepts will do lots of work.

Thanks to Lucy Lippard’s magnificent Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, originally published in 1973, we have a record of a great many artists who can be associated with conceptual art. And more recently a number of historians have described this movement. This book is something quite different. An historian of this movement would need to consider a large number of artists. Since, however, our book is about Beckley, we focus on him, with side references to other artists. As will become clear, the details of his challenging development soon became entirely singular.

An artist enters an ongoing art tradition, responding to some of his predecessors and, if successful, creating a response amongst his successors. The Shape of Time (1962) by George Kubler, a book famous amongst artists of Beckley’s generation, describes what I will call an artist’s entry point, that moment when she or he enters the art world. This, to say the same thing in revealingly different words, is what’s involved with calling art making an essentially historical activity. What you can then accomplish and how you can accomplish it is a function, to some degree, of what tools are available in your visual culture. Artistic success requires making effective use of your entry point. Choice is involved, for you cannot do everything. Focus is required. And to choose one option is often to exclude others.

Kubler was a specialist historian of the Spanish-speaking world, but his analysis proved to be of significant general interest. Since my account will focus on Beckley’s art world, it’s useful here at the start to briefly note that Kubler’s account is relevant to some of the old masters and the modernists as well as also to contemporary art. In some ways as regards entry point, Nicolas Poussin’s situation when he arrived in Rome, the center of the European artwork in the 1620s was not so different from Édouard Manet’s experience in 1840s Paris, or Beckley’s in 1970s New York. (Of course, the art itself was very different.) There had been in the recent past a grand tradition. Many varied options were on the table, and so the situation of a young artist was exciting and challenging. Just as Poussin could look back on the High Renaissance,

11 10

and Manet at the achievement of Delacroix and Ingres; so Beckley knew that the recent American tradition had been very rich. Deciding what to do next was difficult. And in all three cases, the recent development of the art world meant that there was potential patronage for young artists.

To focus just on the American situation: once the market was established for the Abstract Expressionists, and then in the 1960s for the Pop artists and the Minimalists, it was natural for dealers and collectors to ask what was coming next. In this situation, two thoughts are likely to occur to a young artist entering the art world: success is going to be demanding, given the high level of previous art; and, since this recent tradition involved radical innovation, probably that will continue to be the case. And, of course, there is sure to be competition. Many believe that they are called, but only a few are chosen. Early on, the conceptual artists rebelled against making high priced commodities. Soon enough, however, some of these artists were embraced by the art market, which needed to identify novel art forms.

It’s useful, next, to distinguish between the larger history revealed in the art museum and the history of the immediate past, the works of direct relevance to a young artist. For Beckley Frank Stella’s early black paintings, circa 1959, were very important. Some artists, including Stella himself, saw these pictures as developing the Abstract Expressionist tradition. But it was legitimately possible, also, to see them as marking the end of that tradition, or even the entire tradition of painting. Once art was made by applying black paint in wide regular linear patterns, perhaps that was as far as the art of painting could go. On that reading of this history, the next step was conceptual art.

There’s an important distinction here between such potentially influential precursors and earlier other significant works, which, for one reason or another, are irrelevant to a young artist. Beckley was not interested in doing painterly abstractions, like Willem de Kooning; nor in making Pop works like Andy Warhol. Nor, to look at much earlier art, did he seek to do to cubist portraits like Pablo Picasso or history paintings like Nicolas Poussin. Those prior traditions were simply irrelevant for his immediate practice, however much he might have admired some of this art. We are describing Beckley’s entry point circa 1969. Nowadays of course, the passage of time means that the entire situation has changed. If in 2021 some young artist is taking up the concerns of early Stella, then that artist will have to respond in some way to the large body of work, including some by Stella himself, that has engaged with these ways of thinking. And, also, there are complicated cases of doubling back, as when in 1990 Elaine Sturtevant appropriated Stella’s black paintings, remaking them within her oeuvre, opening up room for a new interpretation of these now canonical works. But Beckley has never been interested in doing appropriations.

An interesting example of crossover of art worlds occurred in the 1980s, when two very different abstract painters, Frank Stella and David Reed took a serious interest in seventeenthcentury, Italian, baroque art. They were not making altarpieces, but the use of space and color in this sacred art was relevant to their works. And Hilma af Klint made both traditional landscapes and radical abstractions. Imagine finding that Beckley had done figurative works on the side.

Would we think him a divided soul because he would be an inhabitant of two different art worlds? I’m not sure. Such crossovers can be tricky to understand.

Mere temporal proximity does not, in itself, determine an artist’s sources. Often artists are most interested in work of their immediate successors. But sometimes they look further back historically. Bob Thompson (1937–66), an African-American painter who at one time lived and worked in Italy, made Poussin one of his key sources, but working in ways that decisively reflect the influence of modernist figuration. What options are available at a given entry point depends, in large part, upon an artist making personal choices from amongst the traditions. And only after the fact is it apparent which were the most promising such choices. Kubler describes how there are better or worse entry points, depending, in part, upon the match of the individual talent with the potential of the tradition. For a painter with figurative skills and interests, 1969 was an unhappy entry point, while for someone with conceptual skills, it was ideal. At least, that’s obvious now after the fact when we observe Beckley’s success.

The phrase “art world” is typically used to identify the community of people interested in the making, interpretation and display of art. Understood in such broad terms, which can be useful, everyone involved with any sort of visual art is part of the art world. Here, however, I adopt a much narrower denotation. For our present purposes an art world consists of that much smaller group of individuals who share more parochial concerns or a sense of how to proceed. As we shall see, the larger art world consists of a number of such smaller art worlds.

In some ways, these art worlds can be productively compared to religious groups. Just as a Catholic can argue about Christian theology with other Catholic believers, but perhaps not with Buddhists or Muslims; so, a conceptual artist can critique and evaluate works by other artists in that community, but not so readily with those from other contemporary or past communities. From Beckley’s viewpoint, for example, however interesting is the recent development of abstract painting, it’s mostly irrelevant to his concerns. And as we’ll see in chapter four, when we get to Caravaggio’s art world, Beckley admires that artist’s paintings whilst acknowledging that their concerns are very distant. It’s very unlikely that he will make a photographic altarpiece. Sometimes there is a certain drama when someone leaves an art world community, as happened when the eminent Minimalist painter Jo Baer decided to abandon abstraction; or, when Philip Guston left abstraction to do his late figurative paintings. Here perhaps there are analogies to a religious person losing their faith.

That said, this analogy between art world and religious communities needs to be used with some care. It’s obviously impossible to be a Catholic believer and a Muslim, because those two religions have opposed beliefs. And so while a non-believer might find, say, Thomas Aquinas an important philosopher with marvelously well-developed arguments, by definition such an outsider would not be a member of the Catholic-community. It’s one thing to admire his claims and another to accept their implications and become a believer. But for an art critic, at least, it’s possible to admire contemporary works coming from diverse communities.

Some such smaller art world groups can be face-to-face communities. In 2012 the upscale art dealer David Zwirner organized an exhibition with catalogue 112 Greene Street: The Early

13 12

Years (1970–1974) that provides a good picture of Beckley’s early art world. When Beckley entered this Manhattan art world, SoHo living lofts were large and very cheap, the market in conceptual art had hardly developed, the conceptual artists were young, and bold experimentation was possible and called for. And that these artists had rough, post-industrial spaces encouraged the development of installations. It was a good time and place to make funky art. Needless to say, that has now all changed radically. That within forty years a grand dealer supported an exhibition including some of these artists from 112 Greene Street indicates the magnitude of the change. Zwirner recreated the rough textured world in the posh spaces now fashionable in upscale galleries.

112 Greene Street reveals many promising artists. Gordon Matta-Clark’s architectural deconstructions, which made active use of the decayed New York architecture, became famous. And a number of these artists, including Beckley, became highly successful. But many of them have disappeared. In that way, this near contemporary art world was like Caravaggio’s Rome in the 1590s or Poussin’s in the 1620s, where, as recent exhibitions have revealed, there were many good painters who did not become well known.

Needless to say, patronage such as Zwirner’s is a double-edged sword. Thanks to this support, the artists could support themselves by selling their works or teaching. And their art becomes well known and much written about. But the gentrification of New York made bohemian lives like those of the pioneering conceptualists impossible, and so it destroyed the conditions of such a community. In this situation, nostalgia is a bad guide, for the entire world economy has changed too much to make going back to the past possible. If the art world is to continue, the next generation will have to learn how to form communities in a very different environment.

A community is a group of people in touch, one with another. And often the function of the art school is to put people in touch with one another. In an art world like Beckley’s where change was rapid, teaching traditional skills was not helpful; he didn’t want to learn to paint like Stella. What art schools, where the faculty come from the previous generation, can teach may be limited. You might say: students need to learn what skills to reject, for that’s the key to moving on.

Let’s place Myself as Washington historically. A photograph like this could, as we said, have physically been made much earlier. But the work of art, photograph plus title, Myself as Washington could, I think, only have entered the art world, the conceptual art world, in 1969. Earlier I spoke of the art world as being ready for a work of art. Just as a person should arrive at an appointment neither too early or rudely delayed, so the same is true of an artwork. The right moment is usually apparent only in retrospect, after the world sees what an artist makes of his entry point.

You might call this early Beckley an imaginary portrait of George Washington. As we’ll see some decades later he took a great interest in Walter Pater’s Imaginary Portraits (1887) a collection of fictional biographies of historical figures. This blurring of the line between historical fact and fiction has remained an important concern for Beckley. It’s characteristically original for him to take an interest in an English literary figure not much discussed in the contemporary art world, and to find a way to employ his concerns in his own art.

Beckley’s description of the origin of this photograph involves an elaborate story. He was painting lines in a Pennsylvania field. When he tried to draw them across the Delaware River, the rushing current took away his paint can. Coming to shore, he found a plaque identifying this as the spot where Washington crossed that river. He celebrated by staying at the George Washington Motel in Pennsylvania and by chopping down a cherry tree. In his photographic narrative works he will develop numerous such shaggy dog stories.

What are we to make of this good story? Perhaps it’s as fictional as Pater’s account of Watteau, as presented in the imaginary diary of a woman who was in love with him. If you think about it, the idea of trying to paint a flowing river doesn’t make sense. Sometimes, of course, it’s a mistake to think about art’s anecdotes too hard, for it destroys the pleasure. Maybe it’s appropriate that Carter Ratcliff, an art writer who is fascinated by the fictions of writing, records this mischievous story. Why, still, does he date this 1969 work to 1971? Is that another fiction? And it seems apt that Beckley is a great reader of Vladimir Nabokov’s fiction, which often plays with alternative realities. To be an aesthete is, perhaps, to see the potential of such fictional realities.

If an artwork is too far ahead of its time, then it may be incomprehensible. In 1855 a Nadar photograph of Baudelaire Myself as Napoleon would, at best, have seemed a puzzling gesture. Such a photograph could have been made, but the art world wasn’t ready for it. And, conversely, if an artwork is too far behind its time, likely it looks derivative. At least, of course, unless some young Beckley student made a photograph Myself as Washington (2021) as an appropriation, or homage to his teacher, responding to his work as Sturtevant did to Stella’s black paintings.

To say, then, that Myself as Washington (1969) entered the art world when it was made is to write a promissory note, a claim that we can offer a plausible historical narrative. There are many histories of conceptual art. Because it became an international movement, with many active participants, a full account would need to be elaborate. Here, however, very briefly, I cash that note, offering the sketch of an account of the origins of conceptualism focused on Beckley. For those purposes I simplify some details, foregrounding discussion of some important philosophical concerns.

Imagine a young artist coming to New York in the late 1960s who in art school has studied the history of modernism in close detail and so has some understanding of the recent history. He knows that recently Marcel Duchamp’s readymades have belatedly become much discussed and influential. He is aware that although some of the Abstract Expressionists continue to paint, that movement belongs to the relatively distant past; and, also, that Pop Art and Minimalism of the early 1960s is now well established. What this history teaches, he knows, is that there is a premium on radical innovation. By 1969, it’s too late to become an Abstract Expressionist, Pop artist or Minimalist, for those positions are well occupied. Belatedness is unlikely to be promising.

This young artist is inspired by his art school study of theorizing to plot his future. Often, he has learnt, new significant work is made by “going further.” Abstract artists went further when they eliminated the subjects of traditional figurative art. Earth artists like

15 14

Dennis Oppenheim went further; instead of depicting their sites, they acted directly to modify these landscapes. And monochrome artists went further when they abolished or abandoned traditional composition. Needless to say, that’s a tricky phrase, “going further.” Most such “furthers” are unproductive; only a few yield success. That said, one reading of the history that this artist might adopt looks to a tradition defined by the readymades, Carl Andre’s plates, Andy Warhol’s silk screens and Donald Judd’s boxes. His aim, then, is to extend this tradition. This was Beckley’s reasoning as now spelt out.

Here is a line of thought justifying this procedure. Traditionally there were two parts to art making: the mental part and the physical part. An artist planned what to do, making drawings or sketches, and then physically executed that plan. In principle, then, the two portions of this activity could be separated. And in some cases, after the artist had done the planning, the execution might be left to someone else. Sometimes, for example, Michelangelo made sketches for paintings executed by other artists. And a number of famous old masters, Rubens and Luca Giordano to name two, had an army of studio assistants. They prepared the canvas, organized the studio and sometimes did the less important parts of the paintings.

When then we get to contemporary art, in some prominent cases the physical part of the activity could be delegated because it was of secondary importance. Warhol’s assistants worked with his silk screens, and Judd farmed out the manufacture of his works; it was Warhol’s concept of working with those photographic images and Judd’s designs for three-dimensional works that mattered. This division of labor goes along with a related development, the deskilling of art making. The influential American art critics associated with the leftist journal October have discussed this concern. In place of “traditional emphasis on virtuoso draftsmanship and painterly finish,” we find “the marks of manual labor.” The dividing line between industrial production and art manufacture was often abolished. In their different ways, Warhol and Judd were involved in deskilling. To speak of deskilling is to identify this transition from manual to physical art making activities.

This process of going further can be tricky, for of course it’s possible to go too far. Imagine someone who, observing that traditionally artists began by establishing a studio, proposes to do just the first step, engaging a studio and nothing more. That person perhaps has not done enough to make art. I say “perhaps” because now there is a tradition of exhibiting empty galleries, showing displaying nothing but that space itself; and so, perhaps having an empty studio could also count as making art. Imagine, for example, that the artist uses the space to develop concepts for artworks.

Or let’s tell a slightly different story. Why not, this young artist thinks, go one step further. If what’s most significant is the artist’s mental activity, then why not skip the physical labor entirely? Why not simply provide some record of the idea and identify that record as the artwork?

A great deal of conceptual art follows exactly that plan. Indeed, Beckley’s Song for a Chin-Up (1971) is one such example. He composed a very short song to accompany chinning, and hired a singer to perform that work whilst chinning himself. And although he made the self-portrait

for Myself as Washington, to some degree that artwork employs the same general way of thinking. A photograph of yourself is easy to make. It wouldn’t matter, I think, if Beckley had hired a photographer, for it was the idea, the concept that showed Beckley’s visual intelligence. Here a brief discussion of my personal background is useful, for nowadays art worlds include not only artists, but also art critics. And so knowing a little about my practice as critic will help us understand this account of Beckley’s artistic development. In the 1980s when I started publishing art criticism, I initially focused on a particular contemporary art world, that of the younger abstract painters. For these artists, the concerns of the grand Abstract Expressionist tradition were a given. The slightly older abstractionists, Brice Marden, Robert Mangold and Robert Ryman, esteemed seniors, came from a different world. The conceptual artists had very different concerns.

The leading younger abstract painters I met in the 1980s included Thomas Nozkowski, David Reed and Sean Scully. For them the critical question was how to develop a way of painting that had come under critical attack. The three of them responded in very diverse ways to these attacks. But for all of them the account of the birth of conceptual art that I’ve sketched was entirely beside the point. The concern with the distinction between the intellectual and physical acts of making, like the whole account of deskilling didn’t provide them useful guidance. Whatever their personal interest in conceptual art, they really faced different concerns. What Duchamp, Andre, Judd and their successors were doing was essentially irrelevant. They really had a different view of history, for they were in another art world.

Some moralizing critics insist that only one way of making contemporary art is legitimate. For them there is only one art world. Often that’s how practicing artists think, for if you’re an abstract painter, looking at the history and options of conceptual art is just distracting. It’s important, however, as an art writer to adapt to a multitude of standards, a variety of criteria. In my experience the richness of the present artistic life lies in the variety of contemporary art worlds, which co-exist. What defines an art world positively is a shared sense of what visual concerns are worth taking seriously. And, negatively, since for members of one such an art world, the concerns of other art worlds are essentially irrelevant. Right now, to take an extreme case, icons continue to be made for Orthodox churches, but the world of icon makers has little connection with the contemporary art gallery world.

Here having a community is important for validating your activity. Joachim Pissarro has discussed the ways in which for such different artist-pairs as Camille Pissarro (his great grandfather) and Paul Cézanne and also for Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg the sharing of ideas is essential. We are only generalizing that account. What’s fascinating and problematic about outsider artists is that they often lack such a community. Having a community is linked to a certain sense of objectivity. Just as I know that you see the same objects as I do, so within one of these communities, discussion reveals that you and I identify the same problems. At 112 Greene Street many other young artists who had similarly concerns validated Beckley’s pursuits. Such validation is especially important for young artists, who need to sort out their influences.

17 16

As an art writer who has written about diverse periods and places, I’m very aware of how the critical agenda varies from one community to another. We Poussin scholars have a wellestablished agenda, a starting point for ongoing research. Two generations ago Anthony Blunt established a paradigm, which has been extended and challenged by more recent scholars. Making a distinction between study of Poussin’s intellectual concerns and study of “Poussin as an artist,” he offered a suggestive framework. Thus, one recent Louvre exhibition argued that in fact Poussin was, contrary to Blunt’s analysis, a seriously religious artist. And a recent book, Poussin as a Painter: From Classicism to Abstraction (2020) by Richard Verdi supplements Blunt’s analysis. As its title indicates, its thrust is an examination of Poussin the painter. Both of these revisionist interpretations thus employ (and critique) the general established ways of proceeding, which have very little to do with the concerns of contemporary artists like Beckley.

If you look just one generation earlier at the Roman art world, when Caravaggio entered that scene, you find a strikingly different perspective. Poussin did, of course, famously denounce Caravaggio, that destroyer of painting, but by his time, the late 1620s, Caravaggio’s immediate influence had been effectively spent. And if you look elsewhere at other periods that I have written about, Jacques-Louis David’s Paris in the late eighteenth-century or Manet’s art world in the mid to late nineteenth-century to mention two examples, the research agendas were strikingly different. For the writer, as for the artist, there are many different art worlds, generally with strikingly different concerns.

18

“My work arose from the Minimalist Art of the late 1960s. At that time, the medium of painting was experiencing a crisis. Conceptual artists painted directly on the landscape or their own bodies. While attracted by them, I found it disturbing their work depended on documentation. What I wanted in my works was that the photograph be an object of art and not a documentation of art. In 1969 I took a photograph in the likeness of George Washington. In considering this work I thought: ‘This is not documentation, this is clearly invention. I am not George Washington.’ That’s when I started my narrative work.”

Works From the 1960s to the 1970s

23 22

Painted Shrubs for Sol LeWitt, 1969

Painted shrubs

C-print

16 × 20 inches (41 × 51 cm)

Painting with Blue Aquares, 1968 (wall)

Painted Bushes for Sol LeWitt 1968 (floor)

C-print

13

25 24

Twigs Painted White, 1969

Painted branches

C-print

13 × 19 inches (33 × 48 cm)

Vertical Horizon, 1969

Painted branches

× 19 inches (33 × 48 cm)

27 26

From Sunrise to Sunset Looking West at Midday, 1969 36 inches wide × ½ mile (0.91 × 805 m) line painted on fields from sunrise to sunset C-print

13 × 19 inches (33 × 48 cm)

From Sunrise to Sunset (sunrise), 1969 36 inches wide × ½ mile (0.91 × 805 m) line painted on fields from sunrise to sunset C-print

19 × 13 inches (48 × 33 cm)

29 28

Washington’s Crossing, 1969

Photo album, postcard, ink on lined paper 13 × 12 inches (33 × 30.5 cm)

31 30

Six Minute Paper Punch Lines April 21, 1969

Ink and graph paper

4 × 22 inches (10.2 × 56 cm) each sheet

33 32

Song for a Chin-Up 1971 Performed by a student from The Juilliard School, NYC

Song for a Chin-Up, 1972 Photocollage and pen on cardboard 20 × 29.7 inches (51 × 75.5 cm)

35 34

Song for a Sliding Board, 1971 Performed by a student from The Juilliard School, NYC

37 36

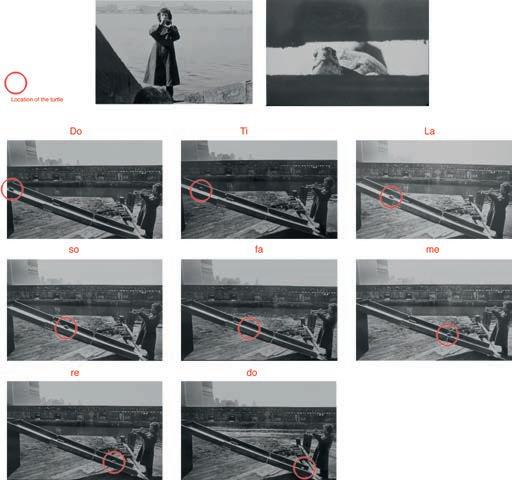

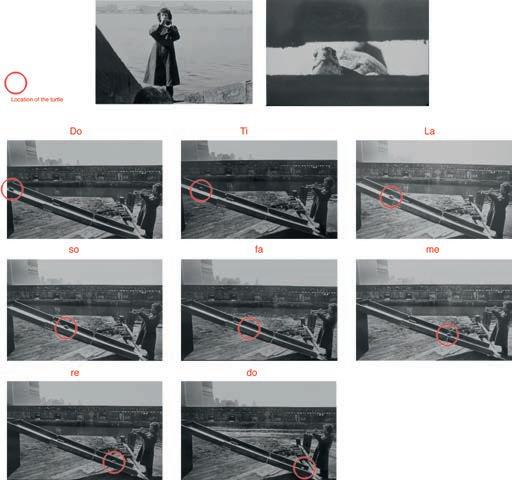

Turtle Trumpet 1971

Performed by Bill Beckley

39 38

Brooklyn Bridge Swings, 1971

Installation view at the Brooklyn Bridge, NYC

41 40

Study for Short Stories for Popsicles, 1971 Wrapper, silkscreened popsicle stick and strawberry flavored popsicle 12 × 16 inches (30 × 41 cm)

Silent Ping Pong Tables, 1971 Installation view at John Gibson Gallery, NYC (top)

Short Story for Hopscotch 1971 (bottom) 104.7 × 108 inches (266 × 275 cm)

43 42

The Origin of And 1972

Black and white prints with written text 30 × 80 inches (76 × 203 cm)

45 44

An Avoidance of Ann, 1972 Black and white prints with written text 28 × 42 inches (71 × 106.7 cm)

Chapter Two

The Word-Image Riddle

However satisfying were his early black paintings, Frank Stella soon wanted to move on, developing more complex compositions, adding other colors. Analogously, while Myself as Washington was a brilliant invention, obviously Beckley could not be satisfied with repeating that picture, in the way that Stuart Gilbert repeatedly did his painted portrait of George Washington, because it was much in demand. Myself as Washington was a great one-shot conceptual work.

Beckley’s Cake Story (1973), which comes four years later, is a two-part artwork, a photograph of one piece of cake on a table and, below, a full paragraph long printed narrative about eating cake. When we see words within a visual work, it’s natural to connect them to the image. Sometimes, as in cubist collages, these words are physically on objects depicted in the painting. Often, also, Chinese old master ink-on-paper landscapes had both images and calligraphy. And in other Western art, the artist’s name is written out. Here, however, it’s natural to think of Beckley’s words as a separate element spelling out the significance of the photograph, in the way that our earlier account of Myself as Washington provides an interpretation of that photograph. We see a photograph of a piece of cake and read a story about someone eating cake. It’s revealing that we use two different verbs to describe our one activity, responding to a single presumably unified artwork.

Upon reflection, however, the statement below this piece of cake offers what is certainly an odd statement. Beckley’s narrative is built around the commonplace saying, “you can’t have your cake and eat it too,” one of those statements whose very banality is a little puzzling if you stop to ponder its meaning. Consider a simple variation on this statement, “you can’t have your cash and spend it too.” True enough, but who would say that? Or, “you can’t drink your wine and save it too.” That’s also true, and also too obvious to need to be said. There’s something in this statement about trying to have your cake and eat it too that hits the spot, so to speak. Substituting cash or wine for the cake doesn’t achieve the same result.

Gustave Flaubert built his last, never-completed novel, Bouvard and Pécuchet, around received ideas, clichés like this saying about eating cake. He thought that their repetition in print demonstrated the idiocy of contemporary journalism. And so Flaubert loved to collect these examples of stupidity, and make fun of people who used them. That on some occasions most of us

47

repeat clichés doesn’t necessarily demonstrate stupidity. After all, even great creative writers need now and then to repeat themselves or speak in commonplace ways. But Cake Story is an artwork, and so it promotes critical analysis even of a silly statement.

Sometimes foolish repeated ideas can be funny. “A quarter of an hour before his death, he was still alive.” Would that it were my creation! But that remembered example of a foolishsounding cliché comes from Jean-Paul Sartre’s critique of Flaubert’s book. You’d have to be a little thoughtless to say that. And yet, “you can’t have your cake and eat it too” is only slightly more sensible. If someone asks you, “can you eat your cake and have it too?”, it would be natural to doubt their intelligence. Or, maybe at least, to question this speaker’s mastery of the English language. If someone asks, “what does that chocolate cake taste like?”, then their question is sensible. But if they ask, “can you eat your cake and have it too?” it’s not quite clear what they’re really asking. Do they propose to eat their cake and then see if they still have it? Who could want to try to do that?

As Beckley’s narrative rightly notes, it’s natural to ask why someone would have what he calls “the double desire of having and eating a cake.” But what then is really strange is his proposal to order a cake “trying to resolve this question,” as if this was the description of an experimental question. If someone says that they want to learn whether you can carry water in a sieve, one might tell them: try it! Beckley’s question seems as preposterous, which is to say that this “double desire” is a nonsensical non-starter. But why, then, does he propose to order a cake to resolve it? If someone asks you, “is it true that a rolling stone gathers no moss,” you don’t tell them to find a stone and roll it to check.

In Cake Story this obviously silly question, what Beckley calls a double desire, is put in context, in a narrative about loss. The narrator, who is alone on his birthday, has recently been in Rome, not alone, staying near the Pantheon. We get a two-sentence description of that well-known monument. And the narrator remembers dinners with someone, who isn’t identified. These words fit together in a way that naturally allows us to construct a little story. Like most of us, the lonely narrator, who doesn’t like being alone on his birthday, remembers other happier times with companionship in Rome. It’s customary to have cake on your birthday. And so, as he says, he orders cake and broods. In this context, “Can you have your cake and eat it too?” then maybe sounds like a question about the difficulty of sustaining relationships.

Here, as any scholar of rhetoric will immediately notice, I’ve fallen into a trap, a real pratfall organized by Beckley. We’ve not been told by him that the authorial “I” is unhappy. Nor, to spell it out a little more, do we know that traveling with someone made him happier, or, indeed, made a difference at all. We may imagine he traveled because he is involved in a love affair. But perhaps the travels were with a sibling, a parent or a child who had to go home. And in truth, in any case, this narrative framework doesn’t really explain why the narrator broods about this commonplace saying. Traveling with someone can be great or miserable or great-then-miserable. But what has that to do with brooding about “having your cake and eating it too?” Proust’s great novel written in part in the first-person is about a character perhaps named Marcel who is very different, in some ways, from Marcel Proust the author. (Unlike Proust the author, he is straight and has no siblings.) Even to identify the narrator as “he”, as I have done so far, is a questionable assumption.

49 48

Cake Story, 1973

Black and white and Cibachrome prints 32 × 20.5 inches (83 × 52 cm)

After all, women too travel and they too may have cake for desert. Here, as in Myself as Washington, the indexical pronoun does a lot of work, aesthetically speaking.

In any case, there’s no reason given to think that this is a truthful autobiographical narrative about its author, Beckley. After all, Cake Story is an artwork. We don’t think that this picture shows a piece of restaurant cake photographed on Beckley’s birthday. So why believe that the written words must be truthful? In verbal as in visual art lies are permitted. By definition, fiction is not true. Here, it will seem, in focusing on the words we’ve gotten further and further away from the photograph of the cake. Let’s go back, then, to link this discussion to our account of Myself as Washington. In identifying that photograph as an artwork, the philosopher Alexander Nehamas has observed to me, it’s arguable that our analysis was slightly misleading. What is an artwork is the photograph plus its interpretation, such as we provided. Minus that interpretation, all we have is a photograph involved with role-playing. Which, also, is what we have in the upper part of Cake Story. Taken alone, the photograph just shows a piece of cake; without the words, there’s no story. This shows that our analysis needs to interpret the words.

Beckley’s development in the four years between Myself as Washington and Cake Story no doubt was an intuitive process, one that I reconstruct now in bookish art historical terms. Rather quickly, at the start of his career, Beckley made interesting art. But that first development, satisfying as it seemed, was, upon reflection, incomplete. For, while Myself as Washington was an artwork, that photograph’s status as art could only be understood with reference to some theory of art, which was made explicit by Beckley or by his commentators. What really was the artwork, then, was Myself as Washington plus some written commentary. Beckley needs the collaboration of a writer who offers an interpretation to create that work. Of course, he could play that role of the commentator himself, as he has done in response to my recent queries. But there’s no record of it immediately available in the artwork itself.

Here it’s possible and interesting to briefly situate Beckley’s development within a broad historical perspective of Western art history. In his Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects (1550) Giorgio Vasari tells a funny story about the minor Florentine painter Buonamico Buffalmacco, who was active 1315–36. Asked for help by a simple-minded colleague, Bruno di Giovanni, who had difficulty making his figures appear lively, Buffalmacco “made him paint some words issuing from the mouth of the woman who is supplicating the Saint, and the answer of the Saint to her.” Here, the great contemporary Vasari scholar Paul Barolsky notes, we find the invention of the modern comic strip. Much later, in the early twentieth-century visual artists made works combining words and images to tell stories. But starting in the early Renaissance, in general European painters expelled words from their pictures. There was a widespread belief that painting should communicate using just images, without any need for words. And so, adding words to paintings is a device roundly ridiculed by various later scholars, including the famous modern connoisseur Bernard Berenson.

Barolsky has written repeatedly about the role of fiction in Vasari’s writing. Maybe this story about Buffalmacco is Vasari’s invention, a mere fiction, but whatever its truth, it’s a good explanation of why words were expelled from Renaissance painting. Whatever the truth of this story, I am saying, a very strong sense had developed that visual art should communicate using

just visual terms, leaving words to literature. The formalist ideal that each art should be pure, making use of only the concerns proper to its medium, is a modernist updating of this traditional belief. In Clement Greenberg’s famous account, not just written words but also storytelling should be left to literature, allowing painting to become an abstract art. This is why, to pick up Barolsky’s point about comics, theorists soundly scorned that art form. To tell stories with a combination of words plus images was to make art as if the pictures alone did not suffice. Comics are a bastard, impure art form, meant for children or adults with poor reading skills. And that’s why in the 1950s, comic books were attacked for combining words and images to tell their stories.

This story of the word-image relationship continues into the present, for what often defines post-modernism is the admission of words into the picture space, as printed or painted distinct visual elements. And Beckley’s combination of photograph plus written narrative in Cake Story is merely one of many recent variations on this theme. It would be easy to compose a long book devoted entirely to these examples of visual art using words. Such varied recent figures as John Baldessari, Mel Bochner, Richard Prince, Ed Ruscha and Christopher Wool use words, sometimes alone on the canvas, sometimes like Beckley in conjunction with images. Because this practice is so familiar, I doubt that Beckley needed to be inspired by reading Vasari to add a text to his artworks. Cake Story and Beckley’s other storytelling works are part-and-parcel of the distinctive recent visual tradition. And so, he didn’t need to look far to find validation for his general way of proceeding. Just as Myself as Washington could only be recognized as an artwork at a moment when conceptual art was developed; so Cake Story achieved success only when many visual artists were involved with presenting words. Cake Story could have been made once photography existed. Physically speaking, it could have been made in 1880, but no one would have understood it then as an artwork. As we said in the previous chapter, entry points matter. Yet, what this general analysis leaves marginal is our primary concern, namely the focus on Beckley’s distinctive personal development. The danger of generalized survey art histories is that they too easily fail to do justice to individuals. Baldessari, Bochner, Prince, Ruscha and Wool developed very differently from Beckley. As we’ve presented this narrative, it might seem as if Beckley merely needed to move an interpretation into the artwork, as if adding a panel with words describing Myself as Washington by quoting the account we provided would resolve the problem. With the added words, its identity as a proper conceptual artwork would be secure. But already our account of Cake Story has revealed why there needs to be more here to the discussion.

Our words in the previous chapter about Myself as Washington aspired to be a truthful interpretation. Any errors about facts were purely unintentional! But the words at the bottom of Cake Story are, so we have seen, artful fiction. Beckley’s narrative is one part of that twopart conceptual photographic narrative, not an explanation or interpretation of that artwork. This conclusion should be unexpected, for after all they are components within an artwork. Now we have a two-part work: the concept, as revealed in a photograph; and the text. But whereas in conceptual art the narrative came from a critic, now, provided by the artist, it was internal, as it were, to the work. Cake Story is a two-part work, photograph plus fictional narrative. It is, in the positive sense, a bastard artwork, a visual work and literature both at the same time.

51 50

And that means that we need to analyze it using the skills of both art historians and literary critics. Let’s begin by looking at its literary significance.

Often novels come with an editorial disclosure, reminding the reader that they are fiction. Before the text of the recent English-language translation of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1955 The Street Kids, an editorial note reads: “This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real locales are used fictitiously.” The novel, set in the proletariat life of boys in suburban Rome, a scene frequented by its author, who in 1975 was murdered, perhaps by some boys like those he loved, names many real places in that city. And the fictional characters are, one assumes, much like the boys Pasolini knew. But that novel is a fiction.

Occasionally, however, fiction presents real people, identified as such. Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time presents artworks, people and places close enough to reality that it has inspired repeated, book length searches for its sources. All in vain, for as Proust explains explicitly at one point, in his novel everything is invented, the paintings of Elstir, the music of Vinteuil and much more. With one exception: He presents a touching story of nationalist familial devotion, the account of a privileged older couple who, during the Great War, come after the death in combat of its young owner, to manage a café day for night. Thanks to such self-sacrifice, we are told by Proust, France survived. Here I deliberately don’t give a textual reference, for if you don’t know this magical long novel by heart, then I urge you to read it in search of this great brief scene. Just as a large painting will sometimes include a small self-portrait of its artist, so here Proust introduces a tiny element of reality into his elaborate fiction.

In general, however, the convention, which Cake Story obeys, is that when a narrative is presented within an artwork, then usually it is fictional. Of course, a visual artist also could choose to reject that convention. Indeed, one important group of recent literary productions blurs the line between fiction and prose with true narratives. But, as we have seen, the little story Beckley tells is a fiction that needs to be interpreted. What gives Cake Story its unity is its conjunction of a playful photograph and a first-person narra<tive story about playacting. Precisely because the words enter into an artwork, they are fictional, unlike our merely prosaic interpretation in the previous chapter of Myself as Washington. And yet, the real world and what I am calling the world of art are not entirely distinct, but overlap. George Washington existed and so does the piece of cake photographed for Beckley’s artwork. Proust’s imaginary art, places and people are rooted in reality, and so, also, are Beckley’s words in Cake Story, which describe a real place, the Roman Pantheon.

The most poetic description known to me of this relationship between fictional and real worlds is found in the novels by an author much admired by Beckley, Vladimir Nabokov, who loved to construct alternative worlds. And the Nabokovian novel of most immediate relevance for our present purposes is Pale Fire (1962). That book, like Cake Story, is a two-part artwork, a relatively short poem and relatively long commentary. At first blush, the commentary seems entirely mad, a story which has nothing to do with this relatively banal, apparently straightforward poem. This novel has inspired an army of commentators. Nabokov, it is often said, was parodying the academic industry of literary criticism, which he despised.

The commentary in Pale Fire tells about an exile from Zembla, an imaginary kingdom, which has maybe some similarities with Nabokov’s lost Russia. The title comes from Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens: “The moon’s an arrant thief, And her pale fire she snatches from the sun” (Act IV, scene 3). And the commentator, Charles Kinbote, cannot recognize that Shakespearian allusion because his Shakespeare text is an (imaginary) Zemblan translation of Shakespeare’s plays. A further twist in the story, so I have argued in my previously published account, consists in the clear explanation of how that translation was carried by the commentator from Zembla to this world. The Nabokovian lesson is that when texts move from the world of art to reality, so called, their identity is changed, but in recognizable ways permitting an attentive reader to chart their passage. Zembla, Nabokov’s fictional creation, is linked to this world in which the poem “Pale Fire” is written. People and also books like the Shakespeare text of Timon of Athens can move from one world to another, changing in the process.

Knowing that Kinbote is reading Shakespeare, we can recognize the source of the title of the poem, “Pale Fire.” Those words are in the text of Timon of Athens. Nabokov’s procedure, here and elsewhere in his fiction, is something more than a clever authorial trick, it’s a statement about the nature of fiction in art. And, so I am suggesting, this novel helps us understand Cake Story. To apply this way of thinking to our present discussion, when an interpretation of a conceptual work moves from the world of prose interpretation into that artwork, it changes. This, then is why Beckley’s statement that appears in the lower portion of Cake Story is a fiction, not an interpretation of the photograph. And what this means for us is that an interpretation of that twopart artwork must deal with both word and image. Here, I hasten to add, I am not imagining Beckley to be a Nabokov-scholar though, as I have said, he has a long-standing interest in the novelist. Rather, I am thinking of him as employing in his own visual art a Nabokovian way of thinking in this conjunction of picture and text. The idea that the borderline between truthful narrative and fiction is porous is often seductive.

We need, then, still to interpret Cake Story, taking into account both photograph and words. Here it will help to look at a second Beckley example, another photographic conceptual narrative created the next year. De Kooning’s Stove (1974) shows, on the right, the photograph of a stove with one burner on, and on the left panel a narrative by Beckley about Willem de Kooning and stoves. Beckley’s text has in effect two parts in its one long paragraph. There is the story that de Kooning was afraid of a blank canvas, and so liked to write the name of something in his studio on that canvas. The note adds that there were two kinds of Abstract Expressionists, those like de Kooning and others Beckley admired more, who were precursors of minimalists and conceptualists. Those artists in the latter group would include Barnett Newman, who later, as we will see in the next chapter, became important later to Beckley, and of course Stella, who, as we have seen, had been important for him earlier. Beckley’s text says that he removed all the furniture from his studio, except for the stove, which he uses to keep warm. And his chair, which we see reflected in the shiny red stove.

In a more complicated way than is the case with the narrative in Cake Story, this too is a nonsensical narrative. Since it comes a year later, it’s possible to legitimately imagine that Beckley refined his mastery of this technique. Again, let’s start by being oddly literal minded.

53 52

Assuming, as they say, for the purposes of argument!, that the story about de Kooning’s fear of the blank canvas is true, why in the world would that artist have emptied out his studio in response to his fear? How, I wonder, would that procedure have helped him master that fear of putting something on the canvas? And why, given that Beckley, as he says, admires other different Abstract Expressionists more, would he, too, have emptied out his studio, except for the stove, which the narrator says that he uses to keep warm. Why then would Beckley imitate de Kooning in this way? None of this, neither the story about de Kooning nor about the narrator makes any sense.

Here too, as in the story about eating cake and Rome we have nonsense accompanying a photograph, which is a sort of illustration of the words. And, again, also, we have a firstperson narrative which need not be about Beckley. No doubt Beckley has visited Rome and so it’s likely that he saw the Pantheon. So the narrative in Cake Story has some roots in reality. And for all I know, perhaps sometimes he traveled with someone and at other times alone. A similar account maybe is true of the narrative in De Kooning’s Stove. Many de Kooning stories have been told. Beckley, too, has a studio and when very young he did paint, so maybe he too had a stove. But so far as I know, he doesn’t need to turn on the stove to keep warm in the studio where he makes photographs. And even if his studio is sometimes too cold, the story of de Kooning’s fear of the empty canvas doesn’t seem to be relevant to Beckley’s working procedure.

Again, of course, the “I” here, the person making this statement doesn’t need to be identified with Beckley himself, for this text too, like the one in Cake Story, is another fiction. The question, then, is how to understand De Kooning’s Stove. When, over the years I’ve looked at Beckley’s artworks from this period, I’ve often thought of how they are close to being funny. Close but not quite funny. His narratives remind me of some of the jokes involving illogic that Freud analyzes. Consider one from his Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (1905). A rabbi at Cracow cries out that the rabbi in Lemberg has just died. However, when people from Lemberg arrive at Cracow, they reveal that in fact this rabbi is still alive. In response, one of the Cracow rabbi’s disciples says: this “makes no difference… Whatever you may say, the Kück (distant view) from Cracow to Lemberg was a magnificent one.” Freud’s making fun of rabbinical wisdom is a very Jewish tradition. And, analogously, maybe Beckley is joking about de Kooning. Both stories, it seems to me, are almost funny. But here of course, as always one’s response to humor is personal. When I taught philosophy and discussed psychoanalysis, I needed examples of jokes. Then I discovered that many of Freud’s jokes were very much an acquired taste. First Jew, “Did you take a bath?”; second Jew, “Why, is one missing?” That joke only makes sense if you know that poor Eastern European Jews, who didn’t have bathing facilities in their homes went to the public bathhouse. Obviously, a bath, unlike a jar of gefilte fish say, isn’t the sort of material thing that one can steal. But many of Freud’s Jewish jokes need some explanation if they are not to seem simply nonsensical. We often make sense of the nonsense in jokes, Freud argue, by recognizing the role of aggression. The two jokes I’ve presented are both good examples. To laugh at a joke, he implies, is to interpret it, by acknowledging how it permits us to say something that if said in so many words would be simply hostile. This, of course, is why the goyim should resist trying to tell Jewish jokes. But we non-artists can tell de Kooning jokes.

55 54

Joke about Elephants 1973 Black and white prints 25 × 18 inches (63.5 × 46 cm)

Another Beckley, Joke about Elephants (1973) seems a commentary on this situation. It contains the photograph of a piano and a narrative about the story: “How are elephants and storks alike” Answer: they both can’t play the piano. The narrator says that initially he didn’t find this joke funny. But then after his piano technique improved, he came to understand such humor. Again, the illogic is transparent. There’s no reason to think that improving your piano technique helps you understand jokes about playing the piano. And it’s obvious why neither elephants nor storks can play the piano. That’s too obvious, surely, to need any explanation.

Whatever we make of Freud’s theory, what by contrast is revealing here about Beckley’s nonsense is that it isn’t funny, at least, not in my experience. In some of his narrative paintings, Richard Prince writes clichéd psychiatrist jokes, which are intended to be funny. Such humor often, of course, involves hostility to psychoanalysis. But Beckley’s stove story isn’t hostile to de Kooning. It’s slightly silly, a bit of nonsense, which is close enough to sense to be puzzling, but not, on reflection, clear. Here, as is also the case with the narrator of Cake Story, it’s puzzling to realize that the narrator’s mental processes are illogical, as certainly were de Kooning’s. Many artists were much inspired by de Kooning, but so far as I know none of them were inspired to remove the studio furniture except for their stoves. Maybe that’s Beckley’s point: making art is inherently illogical. Often de Kooning’s recorded conversations had a charming illogic. Here maybe, as with George Washington, a literally false story may be revealing.

This story about de Kooning’s fear of the blank canvas, which leads into an account of the two schools of Abstract Expressionism, is a short shaggy dog story. Maybe that phrase “shaggy dog story” is an oxymoron, for by definition shaggy dog stories are supposed to be long! More recently Beckley has published some longer shaggy dog stories. The source of this illogic is worth identifying. I mean: It’s not really clear what this account of that artist’s desire to look at a stove, or some object depicted on the canvas, has to do with Beckley’s desire to have a stove in order to keep warm. Here, as often with jokes, with such statements one feels oddly literal minded, foolish in fact, in spelling out the meaning, which doesn’t make sense.

In the 1990s, two decades later, Beckley happened to find in a used bookstore a late nineteenthcentury book that intrigued him, Walter Pater’s Imaginary Portraits (1887). Although known to academic scholars, Pater’s book is not one likely to be read by contemporary artists. But Beckley was fascinated, and so reprinted this volume with his new introduction, in 1997. His reprint offers a subtle characterization of Pater’s prose. Pater’s imaginary portraits, fictional accounts of real individuals, use this supplementary information to provide an interpretation of that person’s work. Often biographers add surmised information to enrich the story. Pater makes the implications of that procedure explicit, by making it clear that his stories are of imagined lives based upon real history. In particular, “A Prince of Court Painters” is an imaginary portrait of Jean-Antoine Watteau (1686–1719), the great, relatively short-lived French painter.

Relatively little is known about Watteau’s life. In an essay published in 1856, the brothers Goncourt, champions of old regime painting, published what they claimed was an old missing life of Watteau. Building upon that account, Pater’s life is an imaginary diary by the sister of another painter, Jean-Baptiste Pater, his namesake. She is imagined by Pater to be in love with Watteau. Watteau, she argues, depicts that world with such grandeur “partly because he despises it.”

To understand Watteau’s subjects, you must know, she says, that he always remembered once being a poor boy, who was outside of this grand world. This is a plausible speculation. Pater’s imaginary life makes sense; it isn’t funny. Beckley offers in De Kooning’s Stove an imaginary, almost nonsensical portrait of that artist, supplemented with a photograph. But unlike “A Prince of Court Painters,” it doesn’t claim to be possibly true.

How complex De Kooning’s Stove is! This short narrative and simple-seeming photograph inspires a whole chain of reflections about semiotics. And our analysis has barely begun, for each point here could be developed at much greater length. Beckley has developed numerous satisfying variations on this theme, narrative photographic art. Combining words and images allowed telling funny stories, as Cake Story (1973), and erotic scenes such as Bus (1976). Clearly this was a marvelous form of art making that might have been extended indefinitely. His prior development from conceptual to photographic narrative art was occasioned, I think, by the felt insufficiency of the conceptual works lacking, as we have noted, the supplement of a narrative explanation. But here that problem had been solved.

And yet, Beckley’s ability to be self-critical meant that there was more to come. Beauty had been expelled from his art. But since ultimately he wanted beauty, not just humor in his art he needed to bring it back. Beckley’s reprint of Imaginary Portraits included a related short story published separately, “A Child in the House.” As Beckley explains, that essay gave him some ideas about how to bring beauty into his art. Pater turned out to be an essential resource.

57 56

“1969 marked the beginning of my so-called ‘narrative art.’ I was basically writing a story and taking pictures at the same time. The text evolved with the photos. Some of the works didn’t have text, but they were still narratives. In the 1980s, I used various materials, and my work became more sculptural and pictorial. By the end of the 1980s, I had found a way to integrate these materials with photography. The integration of photography and pictorial surfaces is an important aspect of all my works.”

Works

From the 1970s to the 1990s

61 60

De Kooning’s Stove, 1974

Black and white and Cibachrome prints

41 × 61.8 inches (104 × 157 cm)

Roses Are, Violets Are, Sugar Are, 1974

Cibachrome prints

37.4 × 89.8 inches (95 × 228 cm)

63 62

Paris Bistro 1974

Cibachrome prints

73 × 40 inches (185 × 102 cm)

65 64

67 66

Circle Line, 1974

Cibachrome and black and white prints 40 × 120 inches (102 × 305 cm)

69 68

The Elevator, 1974 Cibachrome and black and white prints 65 × 120 inches (165 × 305 cm)

71 70

Snake Story 1974

Cibachrome and black and white prints 30.5 × 20 inches (77.5 × 50.8 cm)

73 72

Rabbit Turtle, 1974

Black and white prints

38 × 205 inches (96.5 × 520.7 cm)

Sad Ending, 1975

Cibachrome and black and white prints

23.6 × 78.7 inches (60 × 200 cm)

75 74

77 76

Drop and Bucket, 1975

Cibachrome prints 187 × 60 inches (475 × 152.4 cm)

Cibachrome

40 × 90 inches (102 × 229 cm) and

60 × 150 inches (152 × 381 cm)

79 78

Hot and Cold Faucets with Drain, 1975 and 1994

prints

81 80

Mao Dead 1976

Cibachrome and black and white prints 40 × 120 inches (101 × 304 cm)

83 82

Boat, 1976

Cibachrome and black and white prints 40 × 120 inches (102 × 305 cm)

85 84

Bus, 1976

Cibachrome and black and white prints 80 × 90 inches (203 × 229 cm)

87 86

Elements of Romance, 1977

Cibachrome prints

40 × 120 inches (101.6 × 304.8 cm)

89 88

The Bathroom, 1977

Cibachrome and black and white prints 51 × 120 inches (130 × 305 cm)

91 90

The Living Room, 1977

Cibachrome and black and white prints 50 × 120 inches (127 × 304.8 cm)

93 92

The Kitchen, 1977 Cibachrome and black and white prints 110 × 80 inches (279.4 × 203.2 cm)

Roses Are, Violets Are, Sugar Are, 1978

Cibachrome prints

96 × 135 inches (243 × 343 cm)

95 94

97 96

Rising Sun, Falling Coconut, 1978

Cibachrome prints 120 × 40 inches (305 × 101 cm)

99 98

Shoulder Blade, 1978

Cibachrome and black and white prints 120 × 40 inches (305 × 101 cm)

101

100

Deirdre’s Lip, 1978

Cibachrome and black and white prints 70 × 120 inches (177.8 × 304.8 cm)

103 102

Pipes and Hics 1980

Cibachrome prints and aluminum pipes 107 × 87 inches (272 × 221 cm)

Cah Beneath the Grass, 1980

Cibachrome prints and aluminum pipes 105 × 92 inches (267 × 234 cm)

105 104

Cherubs V.S. Saucers 1985 Mixed media on Arches paper 41.3 × 29.5 inches (105 × 75 cm)

History of Handles and Spinning Wheel of Fortune, 1985 Mixed media on Arches paper 41.3 × 29.5 inches (105 × 75 cm)

107 106

Peaches, 1985

Mixed media on Arches paper 41.3 × 29.5 inches (105 × 75 cm)

Mixed media on canvas

73.6 × 32 inches (187 × 81.5 cm)

Mixed media on canvas

73.6 × 32 inches (187 × 81.5 cm)

109 108

Gardens of Pompeii, 1986

Gardens of Pompeii, 1986

111 110

House of Pompeii, 1986

Mixed media on canvas

73.6 × 32 inches (187 × 81.5 cm)

113 112

Villa of the Mysteries, 1986 Mixed media on canvas 60 × 40 inches (152.5 × 102 cm)

House of the Red Capitals, 1986 Acrylic on canvas 60 × 40 inches (152.5 × 102 cm)

115 114

BiPlane or How to Tie a Bowtie in Four Easy Lessons 1987 Plywood, rubber, black and white prints 120 inches (304.8 cm) wingspan

117 116

Bess Truman Having Tea with Her Friends, 1987 Black and white prints, plywood, cloth and rag dolls 51 × 60 inches (130 × 152 cm)

Sunday Paper, 1987 Black and white prints, plywood, cloth and wood 51 × 60 inches (130 × 152 cm)

119 118

Frank (Homage to Frank O’Hara) 1987 Black and white prints, wallpaper, piano leg and “The New York Times” (all from the same day) 80 × 120 inches (203 × 305 cm)

Front Porch, 1987

Photographs, ferns, and screen 60 × 192 inches (152 × 488 cm)

121 120

The Juggler, 1990 Cibachrome prints, plaster, lead and snake skin 96 × 96 inches (244 × 244 cm)

123 122

Study for # 5 of Seven Sins, 1991

Mixed media on museum board 39.7 × 32.2 inches (101 × 82 cm)

Study for # Seven of Seven Sins, 1991 Mixed media on museum board 39.7 × 32.2 inches (101 × 82 cm)

125 124

Study for # 3 of Seven Sins, 1991

Mixed media on museum board 39.7 × 32.2 inches (101 × 82 cm)

Study for Apple Pie, 1991

Mixed media on museum board 39.7 × 32.2 inches (101 × 82 cm)

127 126

Study for Chopsticks, 1991

Mixed media on museum board 60 × 40 inches (152.5 × 102 cm)

Study for Fish Fry # 3, 1991

Mixed media on museum board 39.7 × 32.2 inches (101 × 82 cm)

129 128

Bloody Mary, 1994

Cibachrome prints, felt and bronze with patina 29 × 60 inches (73 × 152 cm)

131 130

Mixed Drinks: Margarita (Gabon, Mexico, United States), 1994 Cibachrome prints, cloth and bronze with patina 29 × 60 inches (73 × 152 cm)

133 132

Niçoise at Sunrise, 1997

Cibachrome prints

54 × 109 inches (138 × 278 cm)

135 134

Down the Drain “Weeping Woman,” 1997 Wood construction and Cibachrome print Ø 90 inches (229 cm)

Down the Drain, Black, 1997 Wood construction and Cibachrome print Ø 90 inches (229 cm)

Chapter Three

The Aesthetics of Beauty

Up to this point, so we have seen, Beckley’s conceptual art was heavily involved with innovative uses of words. His distinctive works shared this concern with a great deal of contemporary art. Myself as Washington needed an accompanying text to be an artwork. And Cake Story and his other conceptual photographic narratives incorporated texts directly into the visual work, which then still required written interpretation. But the art we will now consider, his photographs of beautiful flowers involved the apparent escape from this reliance upon words. These works were highly original, and so were our discussion needs at the start to deal with two distinct questions. Why did Beckley develop this new interest in beauty? And given that interest, why did he make photographs of beautiful flowers? To answer these questions, we start by looking at his amazing literary activities. In the 1990s Beckley edited four books, and wrote introductions to all of them. This writing informed his art.