Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society

Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society

Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society

Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society

Welcome to this very late Summer issue of the White Admiral newsletter. I must apologise for the lateness of this issue, we have moved house over the summer (see my new address below for any written correspondence) and that coupled with a 10 month old who still doesn’t always sleep that well at night has delayed me somewhat.

Thank you to all those who have contributed to this issue. Again, there is a wide range of topics covered in the articles from Stoneworts to Bark Beetles. Please keep sending in your observations, notes and snippets and I will do my best to include as many as possible - the deadline for the next issue is 1st November.

Please can I draw your attention to a couple of SNS events (detailed on page 2). We have our Autumn members’ evening coming up on the 20th November, with a great speaker (Patrick Barkham) confirmed and more to follow and we also have our biennial SNS conference coming up on the 29th February 2020. The conference will once again be held at the very well equipped Wherstead Park and will focus on the importance of roadside verges for wildlife with the aim to share best practice and highlight initiatives from around the country. Tickets can again be purchased securely online and a provisional programme for the day is included on page 3. To purchase tickets and find out more please visit: www.sns.org.uk/pages/conference.shtml.

We are delighted to announce that Patrick Barkham, Natural History Writer for the Guardian, will be giving a presentation on butterflies. He is the author of Islander, Coastlines, Badgerlands and The Butterfly Isles. The evening will also include updates from SNS recorders. A tea/coffee break is provided half way through the proceedings. Please do join us! What

Weds 20th November 2019

7pm for a 7:30pm start

Cedars Hotel, Stowmarket, IP14 2AJ

Sat 29th February 2020

‘On the Verge of Success’ will be a national conference with the aim of sharing best practice on the management of roadside verges. There is increasing interest in these fragments of semi-natural grassland and their potential role as corridors for ecological networking. This will be an opportunity to find out more about some of the pioneering work happening in counties like Lincolnshire and Dorset, in adopting new technologies and county-wide’ wildlife verge management practices, which both benefit wildlife and save money.

We have held tickets price for SNS members at only £13 for the day

Twenty-two people met on Saturday 23rd March in Christchurch Park for the spring walk. Although the park is only a few hundred yards from the bustle of central Ipswich its varied habitats attract a wide variety of wildlife. Thankfully our leader was Philip Murphy, whose vast knowledge of birdlife includes recognising the ‘jizz’ of individual species, even at a distance, and picking out individual birdsong. Initially two species were identified before we started, first the drumming of a great spotted woodpecker then a blackbird’s song. Bird food had been scattered at the entrance to the woodland reserve and along the Wilderness pond path and birds that had gathered included robin, great tits, mallard and mandarin duck. The last mentioned were close enough for everyone to admire the male’s bright and varied plumage and the subtler beauty of the female. The adjacent water produced moorhen and a mating pair of Canada geese. Black-headed gull and a distant diving little grebe were added with the little grebe’s nest, under construction, just visible in the distance. Later there were closer looks at its bright plumage, not evident at a distance. A nesting

coot was a ‘first’ for the park with the female sitting on three eggs and the male still bringing sticks to the nest. The male was vigorously defending its territory, even against the much larger Canada geese.

By then Philip had seen a distant flock of redwing, soon bound for colder breeding areas, a sparrowhawk flew over, blue tit and woodpigeon were seen and the welcome call of a greenfinch, a species recently depleted in numbers by avian disease. A wren, its song such a volume for a small but ubiquitous bird, was the next, with one seen clearly silhouetted on a nearby tree branch. An onomatopoeic chiffchaff was calling and a green woodpecker from the nearby woodland. We stopped at the wet meadow to admire newly flowering snake’s-head fritillary and bright yellows of celandine and marsh marigold. Lady’s smock was just coming into flower, one of the larval food plants of the orange tip butterfly. Our wait was rewarded with views of another declining species, the song thrush, and a pair of long-tailed tits were nesting close by, one bringing a large feather in to add to their superbly constructed nest. Moving north we

added dunnock, chaffinch, carrion crow with nesting material, plus both herring and lesser blackbacked gulls. Goldfinch and magpie followed, then a quick flash of bright plumage from a jay. Philip had already mentioned the possibility of a buzzard and one appeared almost on cue at the top and highest part of the park. Later that same afternoon my wife Marie and I saw four using air thermals as we sat in our back garden, about six hundred yards from the park. This species has rapidly colonised our county - two decades ago it was a rare sighting. A green woodpecker then flew to a distant tree and conveniently gave us good views as

it descended to feed in long grass. Two mistle thrushes were then added to the list, out in the open so their greater size and more erect posture could be compared to the song thrush. A jackdaw was next, with a stock dove nearby on the ground, again clearly visible so the differences between it and a woodpigeon could be noted. This brought the total of bird species seen or heard to an impressive thirty-three and such was Philip’s enthusiasm that when we ended he had added almost a whole extra hour to the scheduled duration of the walk.

Richard Stewart.Joan Hardingham provides an interesting observation with regards to the Common Kingfisher Alcedo atthis catching and presumably eating common newts Lissotriton vulgaris in her garden pond. In a study carried out in the Czech Republic, Čech and Čech (2015) found that among 16,933 prey items that were identified from nest sediment of 15 nest sites on 6 trout streams, 1 reservoir and one river, 99.93% of the prey items were fish and 0.07% were non-fish prey.

The fish prey was dominated by European Perch Perca fluviatalis, Roach Rutilis rutilis and Bleak Alburnus alburnus but there was a wide variety of other fish prey. There was also a small sample of non-fish prey including dragonfly larvae, Common Club-tail Gomphusvulgatissimus and Great Diving Beetle Dytiscus marginalis. They also took Spiny -cheeked Crayfish Orconectes limosus and newts Triturus sp. as well as a lizard Lacerta sp.

The authors were of the view that the catching of the non-fish prey appeared to be accidental and so it may but they felt the lizard was important as it was the first record of amniotic prey (lizards), in the diet of Kingfishers

Even so, although Cramp (1985) mentions amphibians, namely young frogs in the diet of the

References

kingfisher it does not mention the taking of newts. Newts taken as blackbird prey is not uncommon and I have seen them feeding on them in my pond. They stand still until one is foolish enough to come near the side and then, goodbye newt.

Jeff MartinCramp.S (ed.) 1985. The Birds of the Western Palearctic Vol. IV. Oxford University Press.

Čech, M. & Čech, P. 2015. Non -fish prey of an exclusive fish-eater: the Common Kingfisher Alcedo atthis. BirdStudy 62: 457-465.

This rather bumpy quite dense specimen (see over page), about 30cm long by 1-2cm thick, was found in the Red Crag at Butley Forest pit near Capel Green. It is a sandy limestone – ferruginous and sand encrusted. Bedding is wellseen in places and some of the irregular lumps roughly follow the bedding. It probably originated by calcareous cementation of sand close to one of the fissures present in the crag here (see Caroline Markham White Admiral 97, Summer 2017).

Also caught up in its formation were several of the tube-like structures at right-angles to the bedding so common in this pit. When found the tubes were agglutinated by sand and shell material (to 2-3cm in width) but this came away to reveal central cores (a number are present in the specimen) of concentrically arranged ferruginous muddy material, 5-8mm width (wider in some other tubes in the pit).

The other tubes in the pit may be over 30cm long. With no actual

organism preserved, they are known as trace fossils. Origins claimed by various authors for such features include crustaceans, echinoids, molluscs, worms and plant roots! They are sometimes

seen to curve at the base, resembling lug-worms in some ways - perhaps with intake and exhalant tubes.

Bob Markham.This article is a synopsis of the presentation I gave at the autumn 2018 Members’ Evening. The Little Ouse Headwaters’ Project (LOHP) was established as a Charitable Company in 2002, building on the work of two voluntary groups on Blo’ Norton and Hinderclay Fens. LOHP is a local community project which aims to reconnect and restore remnant fragments of valley fens and associated habitat along the headwaters of the Little Ouse River, along both sides of the

county boundary with Norfolk. Until June 2017, we were entirely volunteer-run. Thanks to a grant from the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, we now have a Conservation Manager in post. Currently, we own or lease and manage a habitat mosaic of approximately 80ha, some of which is SSSI and or SAC.

Biological surveys and recording are important to LOHP, to identify which species are present, inform our management activities, and monitor the effectiveness of

management. We commission specialist surveys when we have the funding to do so, for example NVC and permanent plots for vegetation monitoring and various invertebrate groups, and have provided training for several volunteers to develop their skills to

Captions (clockwise from top left):

New Fen restoration, from abandoned tree nursery and tall nettles; New Fen in recovery; Grass snakes Natrix natrix ; BMS –brown argus Aricia agestis ; CES –kingfisher Alcedo atthis ; Wet fen with ephemeral turf pond and stoneworts Chara species.

carry out some of the monitoring, such as levelling, soil coring, dipwell measurements and Riverfly monitoring. Many knowledgeable recorders also visit our sites, including SNS and Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists’ Society (NNNS) members and groups. We

also host classes from Garboldisham VC Church Primary School for outdoor learning.

Regular activities include CES bird -ringing (BTO Constant Effort Sites Scheme), bird nest and nestbox recording (Nest Recording Scheme, BTO), BMS transect

(Butterfly Monitoring Scheme, Butterfly Conservation), bat box checks and passive recording of bats (Norfolk Bat Survey, BTO), moth-trapping, recording of Orthoptera and Odonata. Like so many others, we have been recording willow emerald damselflies in

the last couple of years. Our mammal group, affiliated to the Suffolk Mammal Group, is studying otters, using a combination of trail cameras and spraint analysis to investigate activity and diet. The trail cameras provide useful records of many other species too, including water vole, water shrew - and an overwintering chiffchaff! We have also carried out more comprehensive surveys of water voles along the valley. We are always keen to add to our knowledge of the wildlife on the sites in our care and welcome visitors. So, if you want to explore, please do so – we will be delighted to receive your records (also

submitted to the relevant county recorders of course!).

LOHP is highly dependent on volunteers to carry out much of the site management, with contractors doing the heavy work. We have weekly work-parties on Wednesdays and monthly work-parties on the second Sunday of the month (excluding May and June). All are welcome.

See www.lohp.org.uk for more information; the archive contains reports of biological surveys.

Rowena Langston, Founder Trustee and chairs the LOHP MonitoringGroup.

There were a few ugly clouds in the sky on an otherwise brightish day but since we had decided to pay a visit to Bull’s Wood on that particular day (13 April), there was no turning back. Once in Cockfield, we made our way to the Palmers farmyard – parking for Bull’s wood and refreshed ourselves with a cup of coffee. Intrepidly, we walked the 500 metres along the track to SWT’s Bull’s Wood. At the point of entry, the clouds looked quite ominous and we did not have to wait that long under a standard oak before the heavens opened and with the heavy rain and hail. But gladly the rain cloud passed over just as quickly as it had come. In earnest, we walked on through this beautifully managed ash and hazel coppiced wood enjoying the icterine yellow of the oxlips, the flowers we had come to admire. They were scattered on both sides of the southern path. On closer examination we noticed that the hail had knocked harshly on the petals of many of the flowers of these beautiful plants with ovate, dark green, wrinkled leaves. True to character, the flower umbels grew in one-sided nodding clusters pointing away from the middle (see photo 1). Also true to character, the

flowers showed distyly. In one morph ‘pin’, the stamens were short and the style long and in the other morph ‘thrum’, the style was short and the stamens long just as in primroses (see inset photo 2).

This heteromorphic self incompatibility’ was to ensure cross pollination, with the flowers on each individual plant either ‘pin’ or ‘thrum’. I thought it might be interesting to count the number of ‘pin’ and ‘thrum’ individuals. In a small and possibly not even a random sample of 20, the ratio of pin to thrum was 35:65. Of course not very scientific, but did this allude to some genetic mystery to maximise diversity?

The rain had freshened everything up. As we approached the eastern end, mixed with the smell of woodland, there was a strong smell of garlic. Thick carpets of ramsons greeted us in every direction. In amongst them was a scattering of wood anemones and we also came across rosettes and emerging flowering stalks of the early purple orchid. Bluebells were out. The silence was striking, especially when sporadically, we heard the loud and distinctive drumming (810 blows lasting a second) of the great spotted woodpecker. Further

along and we spotted a treecreeper, tottering up a tree mouse - like. Delightful. As we neared the western part, we encountered a fence to keep roe deer out from a recently coppiced area (presumably to stop them nibbling on young coppiced shoots!). However, on this side of the fence, there was ample evidence of ‘nibbling’ on oxlips –almost all the plants we saw had their flowering stalks ‘browsed-off’ (see photo 3). Let us hope oxlips will survive this pressure in the long run.

As we left the wood behind, the sun out now, on the field to our left we spotted a couple of hares

chasing each other. It was time for frolicking.

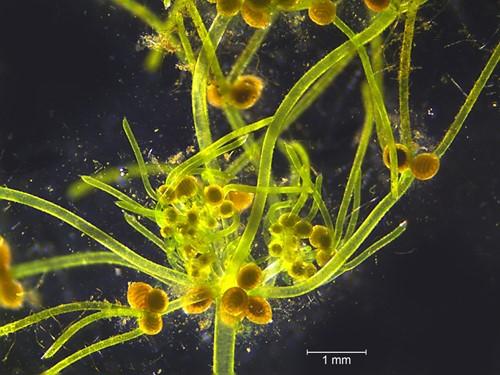

Rasik BhadresaStoneworts are algae and algae don’t sound very exciting, but they are - and over half the British species are threatened. Finding the Endangered Tassel Stonewort (Tolypella intricata) and the Nationally Scarce Clustered Stonewort (Tolypellaglomerata) in one parish was quite thrilling for me in one day in June. But then discovering the Slimy - fruited Stonewort (Nitella capillaris), which was thought to have been extinct in Great Britain since 1959, made this a red-letter day for me! The aptly named, very beautiful but rather slippery Slimy -fruited Stonewort is a fine example of the wider benefits of sympathetic farmland pond restoration beyond improving habitat for the more obvious amphibians and aquatic invertebrates.

I discovered these stoneworts whilst carrying out routine pond surveys for three conservationminded farmers, working together in a cluster, in one North-East Suffolk parish. Six ancient ponds on the three farms were found to host five stonewort species. In

winter 2018, all but one pond had been completely restored by coppicing pond margins and removing decades of accumulated leaf litter or ‘patch-scooped’ to remove a stretch of dense emergent vegetation. The resulting disturbance and increased light had resulted in the very long-lived, dormant oospores (equivalent to seeds) which had lain buried in the pond detritus then germinated a few months later in the spring 2019.

Ticking off the pond plant regulars at the arable field edge pond margins, I noted the distinctively different and very delicate Slimyfruited Stonewort with tiny orange male antheridia (reproductive organs) visible to the naked eye submerged in clear water and I knew that in surveying over 1,000 ponds in the last 30+ years, I hadn’t seen it before! A sample under the microscope back home clearly showed the unique ‘mucilage’ (and kind of mucus that made it quite a slippery little thing!) around the bits of the plant.

Late at night I contacted Nick

Stewart, the national charophyte recorder, with very amateur photographs taken down the microscope and by the morning confirmation had come from experts in Holland and Germany that Slimy-fruited Stonewort was back in the UK!

If you take a look at Martin Sanford’s Flora of Suffolk and you will see how few stonewort records there are for Suffolk, so I have inevitably received plenty of ‘well they are obviously under-recorded aren’t they’ type comments. Rare stoneworts are rarely recorded because they are indeed rare with exacting habitat requirements. It is probably fair to say they are under -recorded but unfair to suggest botanists would not notice them because whilst stoneworts, or charophytes, are a very advanced group of green algae they have a complex structure that superficial-

ly resemble aquatic vascular plants. Most botanists producing a plant list for a wetland site would investigate them, if only to abandon the job later because they don’t have the time, the books or a microscope!

I am not a botanist but as Suffolk Wildlife Trust’s Pond Project adviser since 2004, primarily focussed on great crested newt conservation, I was ‘stoneworttrained’ by Tim Pankhurst at Plantlife back in 2008 as I was determined to look at the wider pond ecology too. I did feel it a bit of a duty to get to grips with priority stoneworts - and then I started to enjoy the challenge!

Stoneworts grow underwater in freshwater and brackish -water habitats, mostly standing water but occasionally in moving. The majority, but not all, of species are confined to calcareous or brackish

situations. Like many plants, some stoneworts are spring-fruiting species and thus only have a small window for being recorded (happily this period coincides with newt survey timing). But also, rare stoneworts are uncommon because as pioneer species they require very exacting conditions (and probably more we don’t understand): clean water, lack of other plant competition, sunlight and in Suffolk’s calcareous soils, increased levels of dissolved bicarbonate ions, which stoneworts use as a carbon source in photosynthesis.

Approximately 50% of the UK’s 33 stoneworts are threatened and 11 species are considered conservation priorities. Stonewort experts at the Natural History Museum are

doing DNA research on Tolypella and Nitella stonewort species and Suffolk samples have been sent to London for study.

In Suffolk’s arable field edge ponds, a clean, non-enriched water source is critical in ensuring clean water and where field drains or leachate input water enriched from fertiliser applied to adjacent arable or pasture fields, the water status is likely to be too enriched/ eutrophic. Similarly, a build-up of years of vegetation and leaf decay increases this organic matter and eutrophic status in ponds that are not regularly cleaned out. Historically, ponds were managed to keep them functioning as sources of water for livestock and if the livestock didn’t keep them open

Slimy - fruited Stonewort out of water; Slimy - fruited Stonewort antheridia (male sex organ of algae) above; close up Mucus surrounding the antheridia is evident. Photo credit: Chris Carter

they were periodically cleaned on a rotation by farmers - the organic matter spread on the field added to soil humus in the heavy clay, and the trees and shrubs were coppiced to ensure good access for livestock and provided useful by-products such as hazel rods or tool handles. Stoneworts would have had good periodic opportunities to germinate after a pond cleaning, fruit and set their oospores and lie low for another 10 years or so.

SWT’s Pond Project has resulted in hundreds of ancient neglected ponds being restored by farmers, and especially those in Countryside Stewardship schemes, for wildlife conservation. These priority stoneworts have benefited from this and are very much a part of

the pond community which provide underwater shelter and breeding opportunities for aquatic invertebrates, snails, amphibians - which in turn provide food for grass snakes and farmland birds.

Thank you and congratulations to the three enthusiastic landowners for their excellent work on pond conservation. We are working with them and Plantlife in this stonewort hotspot in North-East Suffolk to try to establish what makes these ponds suitable for these rare stoneworts (soils, water chemistry?), and a conservation strategy to ensure that the ponds are sympathetically managed to ensure they thrive and hopefully spread.

Suffolk Wildlife Trust continues to encourage landowners to undertake thorough ‘before and after’ pond surveys so we can responsibly advise and properly assess the results of pond restoration. And, just a thought, perhaps those amphibian surveyors out there

References:

might like to focus on recording spring-fruiting rare stoneworts too?

Juliet Hawkins Farm Conservation Adviser

Suffolk Wildlife Trust

Sanford, M, & Fisk, R (2010) AFloraofSuffolk. DK & MN Sanford

Stewart, NF (1996) Stoneworts - Connoisseurs of Clean Water. British Wildlife magazine Vol 8: 2: 92-99.

Stewart, NF, & Church, JM (1992) Red Data Books of Britain & Ireland: Stoneworts. JNCC. Peterborough.

There are three related factors, often unconsidered, that contributed to the success of English natural history as a discipline in the Victorian period – indeed in the entire epoch from the later eighteenth century until the eve of the Great War.

First, the ascendancy of the doctrine of natural theology – the idea that provides arguments for the existence of God, and his nature and properties, based on reason and ordinary experience of n a t u r e . This notion was advocated by many nineteenth century (and earlier) clergy, and adherence to this doctrine provided the intellectual basis for the

parson-naturalist genre. To study nature was to seek insight into the mind of God. Investigation of the natural world was to seek greater understanding of the nature of Creation. Clergy therefore often devoted some of their time to the study of natural history, and the parson-naturalist was very much a part of the English nineteenth century countryside. There were clergy who were expert botanists, entomologists and ornithologists. There were those who took it upon themselves to study mosses, lichens, spiders, freshwater snails and the mineral world. No fragment of Creation was to be neglected. Quaint though some of

the writing, mingling science with theology as it occasionally did, appears to the modern ear, it passionately expressed some of the thought-forms of its day.

Second, there was the extraordinary continuity of some English clergy families. There were families where for generations almost all the male children became Church of England clergy, and most of the daughters married into parsonages. Indeed, one third of the children of clergy married children of clergy. Cousins frequently married.

Also, almost all the Church of England clergy had attended one of two universities – four after the foundation of Kings College London (1829) and Durham (1832).

The result was that there existed an extremely dense and tightly knit network of parson-naturalists. A man’s scientific colleagues might also be his clerical colleagues, his kinsmen, and his university contemporaries. Specimens and natural history observations might be exchanged along with ‘clergy gossip’ at deanery or diocese meetings or assemblies such as meetings of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Letters crisscrossed the country containing comments on the date of the arrival of a migrant bird, or the discovery of an unusual plant, as well as family and clerical news.

The Revd John Stevens Henslow (1796-1861), the mentor of Charles Darwin at Cambridge, was in some ways a typical node in this network. An all-round naturalist, he successively held the chairs of mineralogy and botany at Cambridge, but was Rector of Hitcham in Suffolk for 24 years (1837-1861) – his lectures in Cambridge being compacted into a few weeks. He married Harriet, the sister of the Revd Leonard Jenyns (1800-1893), Rector of Swaffam Bulbeck (a few miles across the Suffolk border into Cambridgeshire), malacologist, entomologist, meteorologist and botanist, but perhaps best known as the person who wrote up Darwin’s collection of fishes from the Beagle voyage. Leonard was himself a parson’s son, and was married twice, on both occasions to the daughters of clergy. He was also the great nephew, and godson, of the Revd Leonard Chappelow (1744-1820), a Norfolk Vicar, who greatly encouraged Leonard Jenyns’ natural history interests: he too was the son of a clergyman.

John Henslow had two sons who reached adulthood. Both became ordained, and one at least was a distinguished naturalist. The Revd George Henslow (1835-1925) was a well-published botanist, and indeed an evolutionist (which his father

was n o t ). Leonard Henslow followed his father to St John’s College, Cambridge, and then to a curacy at Hitcham.

In those days, the relationship of godparent to godchild was sometimes almost as important as that of parent or uncle, and the Revd Adam Sedgwick, Canon of Norwich Cathedral, was godfather to one of John Henslow’s daughters: he seems to have been very close to the Henslow family, for in a letter written to his goddaughter much later in life he recalled how he used to visit them for tea, and ‘laugh and play’ with the family. Adam Sedgwick (1785-1873) was professor of Geology at Cambridge for 60 years, and he too had an important role in Darwin’s training.

Another Henslow daughter, Frances (1825 - 1874), amateur botanist, married Sir Joseph Hooker (1817-1911), Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. (Sir Joseph was a very close friend of Darwin, and was instrumental, along with geologist Charles Lyell, in getting Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Darwin’s joint paper put before the Linnean Society in 1858). When Frances died, Sir Joseph married another daughterof-the parsonage.

An example of Henslow’s network in operation may be seen in the manner in which information was collected for the Flora of Suffolk: a Catalogue of Plants (indigenous or Naturalised) found in the Wild State in the County of Suffolk (London and Bury St Edmunds, 1860) which he wrote in cooperation with a Mr Edmund Skepper (not inappropriately, of Bury St Edmunds). In the Preface to this typical example of a Victorian county flora – there were many such publications – no fewer than six clergy are acknowledged as assisting. (The Flora is available online: on the Biodiversity Heritage Library site : https:// www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ item/264385#page/1/mode/1up).

As has been shown above the network was an open one – nonclergy were integrated into it. Hooker, Lyell and Darwin were honorary members. All three corresponded widely (over 8000 Darwin letters – to and from - are known). All three frequently used clergy as sources of information. Perhaps due to the proximity of Cambridge, the network seems to have been particularly dense in East Anglia: there were many parson-naturalists, in Norfolk and Suffolk, often the driving force behind local natural history societies and museums.

Today’s twitchers, and other naturalists, exchange observations, and no doubt other gossip and possibly scandal, through social media electronic networks. The tradition is an old one. Parson

Henslow of Hitcham was an important node in the network of his own day.

Patrick ArmstrongPatrick is Adjunct Professor of Geography at the University of Western Australia. He has written extensively on nineteenth century science, including The English Parson-Naturalist, 2000. Before moving to Australia, he lived in Cambridge, and undertook fieldwork in Suffolk. He has been a member of the Society for over 50 years.

Muntjac Muntiacus reevesi and Chinese water deer Hydropotes inermis Book Preview

Many naturalists in Suffolk will be familiar with muntjac and will be aware that the species has been involved, along with other deer, in damaging woodland in the county. Some naturalists, particularly those living close to the coast, will have seen Chinese water deer and may wonder about their potential for environmental impact. Indeed, some may muse how and why these two non-native species came to be so widespread in Suffolk?

I have studied both species continuously since the 1970s. Although, most of my work has been in Cambridgeshire, I have tried to make it relevant for people living in other counties, regions and

countries. This year Pelagic Publishing has produced my book, Muntjac and Water Deer: Natural History, Environmental Impact and Management. I have written about these two unrelated and often confused species because they occur together and interact in parts of eastern England as well as in China. The status of both is giving rise to conservation concern on a global scale.

The book weaves together my own observations with those of other researchers from this country and elsewhere. Much original work on water deer has been done in China, but available information on muntjac is heavily dependent on

studies in England. Several of the most detailed studies on muntjac were undertaken in Suffolk. The first section of the book covers the natural history of both species. I provide detailed accounts of breeding and where and when to encounter these deer in the fieldin addition to basic facts on appearance, size, signs, behaviour, habitat, food, mortality, densities, numbers and interactions. Coloni-

sation and population stability are important topics, so how the species have colonised both Cambridgeshire and the country are discussed in depth, as are population changes over time. Straightforward field techniques are described. Novel methods were needed, especially for monitoring population changes, behaviour and impacts. Some of these methods have subsequently been adopted by

site managers, conservationists and researchers. Various impacts are reviewed, but the focus is on muntjac damage in conservation woodland, particularly in Monks Wood National Nature Reserve in Cambridgeshire. Many of the principles relating to woodland impact by muntjac are also applicable to the activities of other species of deer. By working closely with conservationists and stalkers, I have been able to relate management effort to observed changes in deer populations and impacts. Muntjac have been continuously monitored in Monks Wood for more than 30 years –woodland recovery can take decades and some impacts are irreversible.

The impacts of water deer and muntjac in Woodwalton Fen NNR are compared and contrasted.

Water deer have had unacceptable impacts on sallow coppice, but only at exceptionally high densities. Attitudes and approaches to these species have changed; we are actively studying whether water deer might cause environmental problems, not waiting until they have obviously done so.

The book concludes with an overview of management and monitoring - and a consideration of the future of these species here and in their native ranges. Two photographs from the book and its cover are depicted in this article. The book is mainly aimed at deer enthusiasts and people who are concerned about environmental impacts from deer and how they can be remedied. It is available from the main online booksellers.

Arnold CookeIn 2016 our family moved to Suffolk and I was keen to explore the woodlands of the County.

I began with a recording project at Higham, where I found 22 species of bark beetle, including the very rare Lymantor coryli (Perris). A ‘Red Data Book 1’ species, new to the County.

This 2 mm bark beetle was found in dead, dry branches of Hazel, but it can also be found in other broadleaved trees, such as Oak, Pear and Blackthorn. The specimen was sent for identification to Howard Mendel, (Coleoptera Recorder for Suffolk).

In 2017 my next project was at East Bergholt, where I discovered 16 species of bark beetle, including the ‘Nationally Scarce’ speciesDryocoetesalni (George). This 2 mm beetle was found in freshly dead Hazel, and can also be found in Alder, Beech, and Grey Willow.

In 2017 Adrian Knowles (Hymenoptera Recorder for Suffolk) organised a trip to Sotterley Park, and I tagged along. Sotterley Park, owned by the Barne family, proved to be a delightful ancient pasture woodland, surrounded by mature farmland and secondary woodland. The dominant species in the park is mature Oak, but there is also Ash, occasional Hornbeam and Maple and other non-native species. Blocks of secondary woodland at the margins of the park also include Sweet Chestnut. The older trees caught my attention, magnificent Oak specimens 300-400 years old, with

large an cient pol lards and maiden trees, spread out over the parkland.

During six return visits to study the entomology, three small bark beetles (c. 2mm long)

Captions (Clockwise from Top Right): Lymantor coryli (Perris); Dryocoetes alni (George); Sotterley Park; Brood chambers of Lymantor coryli (Perris) in 15 mm diameter Hazel twig.

were found which defied identification. I sent one of them to Howard Mendel, who recognised it as a species of Xyleborini that was new to Britain, but could not name it. The species was not represented in

the National Collection of Coleoptera at the Natural History Museum in London. Harry Taylor at the NHM photographed the mysterious specimen (left).

Howard Mendel sent the photograph to Miloš Knižek, his colleague in the Czech Republic, who is an expert on Scolytinae. He recognised it immediately as Cyclorhipidionbodoanum (Reitter), an adventive species which has now spread to Continental Europe and America.

C. bodoanum targets a range of host trees including Oak, Beech and Sweet Chestnut and the development of young is dependent on fungal growth (‘ambrosia’) in the brood galleries beneath the bark.

There is the possibility that C. bodoanum could have been introduced into Britain with timber products or sapling trees, or by natural wind born migration

across the North Sea, some 100 miles from the Netherlands.

These bark beetles are designed like perfect ‘drill bits’. The adults bore a gallery or tunnel under the bark and in some cases bite little ‘v’ notches in the sides of the tunnel and lay an egg in each notch, and the hatched larvae chew away from the main gallery, thus forming an identifiable network under the bark. The design of these engraved tunnels, and the type of tree chosen are like a signature that can be used to identify the species of beetle present.

From an ecological point of view, bark beetles and ambrosia beetles are crucial components for the functioning of the forest ecosystem. By speeding up wood recycling they make food available to other animals, accumulating nitrogen and initiating complex food chains that feed birds and animals. Their activities create favourable microenvironments for a rich fauna, contributing significantly to an increase in biodiversity and, hence, forest stability.

Jerry LeeCaption: Cyclorhipidion bodoanum (Reitter). Photo: Harry Taylor

Contributions to White Admiral

Deadline for copy for the Winter issue is: 1st Nov

We were treated to a wide variety of talks at a memorable Members’ Evening on 10h April covering orchards, solider flies, an herbarium scanner and the Ipswich Museum’s insect collections. Members’ Evenings are held in the spring

and the autumn every year at the Cedars Hotel in Stowmarket. They enable naturalists (whatever their level of expertise) to share their findings with friends and colleagues within the Society. Everybody learns something new!

Kate Riddington, Collections and learning Curator for Ipswich Museum, enthusiastically demonstrated the new A3 herbarium scanner, for which SNS had contributed £550 in the summer of 2018. The machine enables fragile sheets to be scanned from above without the need to turn them over (as on a conventional scanner). This has made a huge difference to the Museum’s work. The images will be made available via the Herbaria at Home website making the collection accessible to a much wider audience whilst reducing damage to the specimens from handling. Over 1200 sheets have

been scanned so far (one volunteer doing two days a week for six months).

The herbarium comprises around 17500–20000 specimens including significant collections from:

• Lady Blake – 1371 sheets

• H. Weaver – 1492 sheets

• Rev. Hind – 3000 sheets

• John Notcutt – 603 sheets

• Hortus Siccus – 1024 sheets

• Rev. Prof. Edward Cowell –1511 sheets

• Miss Manning – 847 sheets

• Miss Rickards – 696 sheets

• Prof. John Henslow – 458 sheets

SNS has funds available through bursaries and grants for a range of studies of Suffolk flora, fauna and geology or for equipment such as the herbarium scanner.We would like to supportmore projects – ifyouwould like to learn more, please contact Martin Sanford or Gen Broad through theeditortoseeifSNScanhelp.

3-year Heritage Funding project based at the University of East Anglia (UEA). This large-scale collaborative project works with existing county orchard groups and others to learn more about the past, present and future of orchards in six counties in the east of England. Paul is joint chair of Orchards East with Tom Williamson, Professor of History, at the UEA.

OE is undertaking biodiversity surveys in 20 selected orchards. The selection criteria includes the age of the

trees, location across the 6 counties and various types of orchards such as those found in farmstead sites, parks, institutions, community sites, garden nurseries and commercial sites, but with an emphasis on traditional trees and unsprayed sites.

Some species in orchards are Rosaceae family specialists, such as many aphids, galls, wood boring beetles and wood rotting fungi, which co-exist with more generalist species. Surprisingly little research has been done into the wildlife to be found in orchards, so the study

will reveal new information about the invertebrates and epiphytes (mosses, liverworts and lichens) that live on the trees. The study began by using interception traps to investigate each orchard’s flying insects and doing a detailed invertebrate survey of their leaf, wood and fungus eaters, as well as the associated predators. An overall picture will be constructed of each study orchard, its hedges, ground flora, general setting and history. The project is specifically searching for the Noble Chafer Gnorimus nobilis, a species being researched by the People’s Trust for Endangered Species and not yet found in Suffolk (see photo top left).

Peter Vincent, Suffolk Recorder for Diptera, introduced the international “Year of The Fly”, which was formally designated at the International Congress of Dipterology in Windhoek, Namibia last year. It is intended as a celebration of flies and their role in nature and human society. It is hoped that the fascinating world of flies will be revealed to a wider audience and encourage interest in the group throughout the year.

Peter went on to showcase the Sol-

dier fly family, the Stratiomyidae. Soldier flies are a diverse family with great morphological variation, but the family is distinct from other flies due to their unique wing venation. Their larval habitats are varied, several are aquatic filter feeders, some tolerating high levels of salinity or high temperatures; others are terrestrial. Adults are most often found on foliage near bodies of water or in damp habitats and many genera visit flowers.

A team of volunteers has been established at both Colchester & Ipswich Museums to help catalogue and digitise their collections. I have been working during the past year to verify, catalogue and photograph both the Morley collection of Hemiptera Heteroptera, the Aquatic Bugs and

the Morley collection of Silphidae or Sexton Beetles.

Most of the common species of Aquatic bugs in the county were

of this species came from North Cove, surprising as it is common across the county today. Another revelation was a specimen of the river skater Aquarius najas from the River Stour at Nayland, a site

sounds. Often even the basic information of date and collecting location is either slightly illegible, even when one is used to Morley’s handwriting, or is partially missing. So extra research will be needed using the Morley diaries to find out, for example, where in Ipswich he found the least Plea minutissima, on April 10th 1896. Or from where

Over page left: Nicophorus vestigator

Over page right: Nicophorus vespilloides

the only specimen of the rare micro watercricket Microvelia buenoi was captured. The other task which will need to be undertaken once the spreadsheet is complete will be to disseminate the records to national recording schemes because Morley regularly recorded in Ireland, the New Forest and Wales, amongst other places.

Once the Aquatic Bugs were largely complete the Silphidae were started largely because I was asked by the National Recorder, who follows me

on Twitter, to see if Ipswich Museum had any speci mens. Somewhat different from my usual work, an up-to-date photo key made verifying these beetles easy enough although the same problems cropped up. For example, the only specimen of the very rare Aclypea undata, taken by Morley on 29th September 1912, simply bears the inscription 143-6 but no collecting site! Hopefully once the relevant diary can be located we may find out where Morley was working. Unfortunately, though the diaries were sent to the NHM in London for copying some years

ago, not all of them seem to have been returned. So the hunt goes on.

The Sexton beetles were mostly very well preserved as one would expect from such robust creatures, unlike the delicate Mayflies I have recently begun to look at. Good examples include Nicophorus vespilloides found on a dead hedgehog in Bentley Wood in May 1895 or Nicophorus vestigator, found on a dead mole in Belstead May 1896, this last looking for all the world as if it is wearing a Donald Trump wig!

You can find out more about volunteering at: https:// colchesterandipswichmuseums.vol unteermakers.org/.

Don’t forget that you can apply for a SNS and Suffolk Biodiversity Information Service / Flatford Mill

FSC Recording Bursary if you are over the age of 25. Successful applicants can attend FSC courses on species identification, giving them the skills and experience to identify and record Suffolk wildlife. The courses can be elsewhere in the country if appropriate. The bursaries are designed to encourage people to submit species records and so the funds are only available if the applicant submits a

I post many photos of the museum specimens on Twitter @Box_Valley.

given number of records to Suffolk Biodiversity Information Service after completing the course. To find out more about the Suffolk Biological Recording bursary visit: https://www.field - studiescouncil.org/centres/flatfordmill/ learn/natural - historybursaries.aspx

A huge thank you to Kate, Paul, Peter and Adrian for sharing their experiences, expertise and enthusiasm!

30th November | 2pm – 3.30pm Lecture Theatre 1, Ground Floor, Waterfront Building, University of Suffolk.

As part of the celebration of the ’ Year of the Fly’, Erica McAllister, one of the UK’s top experts on Diptera, will be talking about flies and their role in nature and human society at the University of Suffolk’s Waterfront Building. This is a free event.

Suffolk Wildlife Trust has a wealth of excellent courses for adults, all of which are delivered by experienced tutors and are open to all: for those developing their wildlife knowledge and those wishing to dip their toes for the first time in the waters of wildlife in Suffolk.

Here is a taste of what is available on the Trust’s website at: www.suffolkwildlifetrust.org/wildlearning

• W Wild Weather with Mark Lewis

AtCarltonMarshes,Lowestoft,10.30am-3.30pm,Saturday,November2nd.

• W Woodland Management with Giles Cawston

AtBradfieldWoods,Stowmarket,10am-4pm,Saturday,November14th.

• W Winter Twig ID with Jonny Stone

AtFoxburrowFarm,Woodbridge,10am-4pm,Saturday,December7th.

• W Winter Bird ID with Paul Holness

AtLackfordLakes,BuryStEdmunds,10am-4pm,Sunday,December8th.

• W Winter Bird ID With Paul Holness

AtLackfordLakes,BuryStEdmunds,10am-4pm,Sunday, February 9th

• N Nettle Appreciation with Fay Jones

At Redgrave & Lopham Fen, 10.30am-3.30pm, Sunday, March 22nd.

• T The Magic of Bird Migration with David Hodkinson at Carlton Marshes, 10am-3pm, Saturday, April 25th.

• I Introduction to Hedgehogs with Paula Baker Haverhill, 10am-3pm, Saturday, April 25th.

• S Spring Bird ID with Paul Holness at Lackford Lakes BuryStEdmunds,10am-4pm,Sunday, April 26th.

To find out more or to book, please follow the web link, call 01473 890 089 or email info@suffolkwildlifetrust.org

The Suffolk Naturalists’ Society offers six bursaries, of up to £500 each, annually. Larger projects may be eligible for grants of over £500 – please contact SNS for further information.

Activities eligible for funding include: travel and subsistence for field work, visits to scientific institutions, scientific equipment, identification guide books or other items relevant to the study.

Morley Bursary - Studies involving insects (or other invertebrates) other than butterflies and moths.

C Chipperfield Bursary - Studies involving butterflies or moths.

C Cranbrook Bursary - Studies involving mammals or birds.

R Rivis Bursary - Studies of the county's flora.

S Simp son Bursary - In memory of Francis Simpson. The bursary will be awarded for a botanical study where possible.

N Nash Bursary - Studies involving beetles.

Applications should be set in the context of a research question i.e. a clear statement of what the problem is and how the applicant plans to tackle it.

Criteria:

1. Projects should include a large element of original work and further knowledge of Suffolk’s flora, fauna or geology.

2. A written account of the project is required within 12 months of receipt of a bursary. This should be in a form suitable for publication in one of the Society's journals: SuffolkNaturalHistory , Suffolk Birds or White Admiral .

3. Suffolk Naturalists' Society should be acknowledged in all publicity associated with the project and in any publications emanating from the project.

Applications may be made at any time. Please apply to SNS for an application form or visit our website for more details www.sns.org.uk/ pages/bursary.shtml.

The Suffolk Naturalists’ Society, founded in 1929 by Claude Morley (1874 -1951), pioneered the study and recording of the County’s flora, fauna and geology. It is the seed bed from which have grown other important wildlife organisations in Suffolk, such as Suffolk Wildlife Trust (SWT) and Suffolk Bird Group (SBG).

Recording the natural history of Suffolk is still the Society’s primary objective. Members’ observations go to specialist recorders and then on to the Suffolk Biological Records Centre at Ipswich Museum to provide a basis for detailed distribution maps and subsequent analysis with benefits to environmental protection.

Funds held by the Society allow it to offer substantial grants for wildlife studies.

Annually, SNS publishes its transactions Suffolk Natural History, containing studies on the County’s wildlife, plus the County bird report, Suffolk Birds (compiled by SBG). The newsletter White Admiral, with comment and observations, appears three times a year. SNS organises two members’ evenings a year and a conference every two years.

Subscriptions to SNS: Individual membership £ £15; Family/Household membership £ £17; Student membership £ £10; Corporate membership £ £17. Members receive the three publications above.

Joint subscriptions to SNS and SBG: Individual membership £ £30; Family/Household membership £ £35; Student membership £ £18. Joint members receive, in addition to the above, the SBG newsletter The Harrier.

As defined by the Constitution of this Society its objectives shall be:

2.1 To study and record the fauna, flora and geology of the County

2.2 To publish a Transactions and Proceedings and a Bird Report. These shall be free to members except those whose annual subscriptions are in arrears.

2.3 To liaise with other natural history societies and conservation bodies in the County

2.4 To promote interest in natural history and the activities of the Society.

For more details about the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society contact:

Hon. Secretary, Suffolk Naturalists’ Society, c/o Ipswich Museum, High Street, Ipswich, IP1 3QH. Telephone 01473 400251 enquiry@sns.org.uk