Welcome to this Winter issue of the White Admiral newsletter and what will be my last issue as editor.

After some serious consideration, I have decided to step down as editor to the White Admiral as I am struggling to dedicate to it the time and effort it deserves. The White Admiral is being passed into the capable hands of Hawk Honey, a keen naturalist with an interest in bees and wasps, who has contributed many times to this newsletter over the years. I am sure Hawk will inject the newsletter with a new lease of life and will bring to it new and interesting copy with his work links at the Suffolk Wildlife Trust.

Thank you to all those who have supported me in my role as editor over the last 9 years by sending me in such varied and interesting copy - keep up the good work! I am not retiring from the Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society council as I have taken on the role of website manager, to work on the newly revamped website.

There are a wide range of topics covered in this latest issue of White Admiral; from the last in the series about the National Bat Monitoring Programme (Waterways Survey), to a report on new Odonata recorded at Landguard during 2021. I would like to bring to your attention the date of Suffolk Naturalists Society AGM (see page 2) and the Spring Members’ Evening which will once again take place on Zoom rather than in person. Hopefully, if COVID continues to become less of an issue we can look forward to meeting up again in person. However, we will continue to take a cautious approach at the moment.

7.00 p.m. Wednesday 27th April 2022 | via Zoom

To join the Zoom Meeting visit this link:

https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81400426741?

pwd=S28zc1ZKdUJ5eFFVY3dieVp3eHVIUT09

Or input the meeting ID into your app:

814 0042 6741

Passcode: 322934

The waiting room will be open from 6:50pm

Following the conclusion of formal business there will be a presentation from Simone Bullion called:

‘ The Mammals of Suffolk ’

- what has changed in the last 10 years?

Simone Bullion will review some of the more significant new records and changes in status of the county ’ s mammals.

Contributions to White Admiral

Deadline for copy for Spring issue is: 1st March

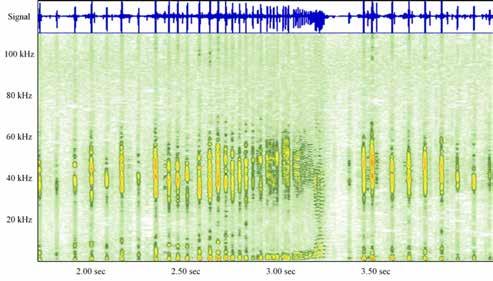

In the last of our articles on the National Bat Monitoring Programme (NBMP) we report on the Waterways Survey which follows on from the Roost and Field Surveys and takes place in August. The focus for this survey is the Daubentons Bat, or Water Bat, which as its name suggests, feeds almost exclusively over water. Its particularly large toes are designed to scoop up food from the surface of the water, either insects caught in the surface tension or swimming at the surface. Not only does it have long toes but also its hind feet are free from the flight membrane so that this does not hinder the sweep for food. Their echolocation is most effective on still water, as with a diagonal approach, the signal easily reflects off the surface of the water away from the bat, while a solid struggling insect will reflect the signal back to the bat, making it easily detected and then scooped up. So Daubentons prefer to feed over open water with little floating vegetation, which would hinder their echolocation, and any agitation of the water makes detection of prey more difficult.

The survey follows a similar protocol to the Field Survey, which was

reported on in the last issue of White Admiral (newsletter 107). In this case a 1km section of waterway is allocated to the surveyor which is then divided to give ten recording points each 100 metres apart. At each point we stand looking over the water, bat detector in hand and count the number of passes of Daubenton bats that occur over a four-minute period. To record Daubentons bats the bat detector is tuned into 35 kilohertz. The sound it makes on the bat detector is a sort of ‘rat-a-tattat’, like a machine gun fire. However, other similar species, all members of the genus Myotis, also echolocate on a very similar frequency and they are difficult to separate in the field. So, to confirm that we are recording a Daubentons bat, we must be able to see it. This requires one additional piece of equipment, a flashlight. On detecting a bat echolocating on the correct frequency, we then scan the water with the flashlight. Daubentons have a very distinctive flight pattern as they dart across the water surface in search of food. They often leave a silvery furrow through the water surface as they trawl with their feet and the tip of their tail trails through the water. Their under-fur is also a

brilliant whitish-grey and this fur can easily be seen under the bright light as they turn. If they detect prey, they will lower their feet and adopt a more upright stance to strike their prey and scoop it up. The body then rolls forward so the food can be transferred into the mouth. They can capture quite large moths and have even been known to take small fish at the surface. However, much of their food consists of non-biting midges.

There are two recording periods, with the first observation between 1st and 15th August and the second between 16th and 30th. As Daubentons tend to emerge from their roosts slightly later than some of the other bats, our survey starts 40 minutes after sunset and so it is quite dark by the time we are recording and stumbling across the fields. In addition to recording bat passes we also note down the temperature, cloud cover, wind strength and any precipitation, although we try to avoid damp nights! Ideally the temperature should be over 7oC, it should be dry and not too windy.

The recording site is allocated by the Bat Conservation Trust. The sites are all along flowing waterways rather than over static water such as a pond or lake. Our first survey site was part of the Belstead Brook at Copdock by the A12/A14 intersection. This rapidly proved to be unsuitable, not just for

the bats, but also for the recorder, as it was very overgrown making hunting difficult for the bats and visual access to the water surface virtually impossible for us. So, after a couple of fruitless years, we were reallocated a much more productive and accessible site on the River Stour at Flatford.

We set off in the twilight and make our way out to the most distant point, start the survey, and then steadily make our way back to the last point opposite the mill pool at Flatford Field Centre. To add to our evenings, we have had some wonderful views of a barn owl as it hawks over the meadows at dusk, but we have yet to see an otter – we live in hope. However, a slightly more memorable encounter was with the herd of cows that graze the water meadows. During the day they tend to keep away from the riverbank and all the human disturbance but come the evening they can be a little more unpredictable. We had one very memorable evening where we were suddenly aware of a stampede towards the gate by the bridge at Flatford and I was all but ready to dive into the river to avoid being crushed under foot.

We have now been undertaking the survey here for 8 years and the results are shown opposite.

There is no real pattern to the data although the number of passes seems to be decreasing. One thing we have noticed is the increase in disturbance. In the early years of the survey, once the light started to fade, we would

have the river bank to ourselves. In more recent years, there has been far more use of the river, even after dark, with stand-up paddle boarders and canoeists floating by in the dark, people setting up camp on the river

side and kids swimming in the river. This was especially apparent during the last two Covid years with more people taking their recreation locally. There are also areas where the amount of duckweed is increasing which will hamper the feeding by bats. One major distraction to our recording is the sheer quantity of Soprano Pipistrelle bats that we both see, and record flying, over the river and adjacent banks. This river section is obviously a prime feeding ground for them, and their echolocation can be almost continuous on the bat detector. They are also very visible and think nothing of swooping over our heads. You can see where the old -

wives-tale of bats getting caught in the hair came from.

This data feeds into the national data set, which has been running since 1998. We are one of 876 sites surveyed and over this time there has been no significant change in the population of Daubentons in the UK and the population is considered to be stable.

If you are interested in joining in with any of the surveys we have reported on in the last four issues please go to the NBMP website for further details –https://www.bats.org.uk or contact Suffolk Bat Group who can loan equipment, advise on training and possibly arrange for you to join a survey to gain experience.

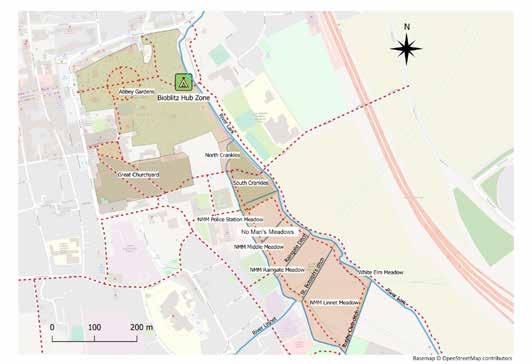

Bury St. Edmunds will be hosting a BioBlitz on Friday 20th and Saturday 21st May 2022 as part of a series of events celebrating 1,000 years since the founding of St. Edmunds Abbey by King Canute.

With the help of school children, members of the public, skilled naturalists and partner organisations, the Bury Water Meadows Group are looking to build on our existing knowledge of the species that visit or reside within the bounds of the Abbey Precinct. The focus areas within the Abbey Precinct include the Abbey Gardens, the Great Churchyard, and the water meadow areas known as the Crankles and No Man ’s Meadows (see Map of Bury BioBlitz).

Kingfishers, Hedgehogs and Bee Orchids are among familiar favourite species which may be spotted within the BioBlitz zone by regular and observant visitors. As management efforts are increasingly focused on improving habitats within the Abbey Precinct for the benefit of wildlife, we are also keen to discover more about some of the less studied groups contributing to the intricate web of life in this historic site.

Are you able to add invertebrates, fungi or bryophytes to the list of 361 species (largely birds, butterflies and flowering plants) recorded by Bury Water Meadows Group volunteers in recent years? Or perhaps you have the skills to help us to revisit the list of

over 60 lichen species found in the Abbey Gardens and Great Churchyard 30 years on from the last concerted recording effort on the site?

We welcome input from naturalists of all levels of expertise to gather observations and share your records with us during the BioBlitz. We would also like to encourage you to stop by at the BioBlitz hub zone in the Abbey Gardens to meet with other naturalists and help members of the public with identifying their own observations. If you have a special expertise that you would be willing to share to help in our

effort, we would be delighted to hear from you in advance of the BioBlitz. Please contact: info@burywatermeadowgroup.org.uk to discuss details and opportunities. There will be a series of free walks, demonstrations, and activities throughout the day on Saturday 21st May which will include some drop -in events and others requiring advance booking. Please keep an eye on the event website for further details: https://www.visitburystedmunds.co.uk/whats -on/abbey -1000-bioblitz.

The Royal Entomological Society (RES) organises Insect Week (formerly National Insect Week). Insect Week encourages people of all ages to learn more about insects. This event takes place every two years, and is supported by a large number of partner organisations with interests in the science, natural history, and conservation of insects. Over a million insects have been described and named worldwide. There are more than 24,000 insect species in the UK alone and we can find insects in almost every habitat. The majority are beneficial to humans, such as pollinators, e.g. bees, hoverflies, and many beetles; the insect decomposers

help the environment too by breaking down decaying dead wood and releasing its nutrients into the soil, e.g. many beetles. Insects are also preyed upon and provide food for fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, humans and other mammals. Relatively few insect species are pests and/or parasites.

The RES website is designed to help you learn more about insects and the people who study them. You’ll find everything you need at Royal Entomological Society (https:// www.royensoc.co.uk/) to join in with events and competitions held during Insect Week.

I’ve been moth trapping regularly in Brantham for 10 years and on and off for some time before this. A continuing source of interest is watching the arrival and disappearance of species through the seasons, reflecting the huge variety in their individual life cycles and the ecological niches they occupy. Although less predictable, it ’s also exciting when the trap reveals

species considered as true migrants, carried here on winds that draw air up from southern Europe or north Africa.

Following the run of south -westerlies in the last few days of December 2021 and having just travelled home on New Year’s Day from an unseasonably warm Devon, it was with some hope and expectation that I switched on the moth light that evening. Next morning

that typically overwinter as adults, but it was the third one that caused a sharp intake of breath.

Although I hadn’t recorded or seen a Gem Nycterosea obstipata before, I knew it well enough from leafing through the field guides, but also more importantly that the timing of this record was extremely unusual.

And so, it has proved. Gem is a small migrant geometrid with a wingspan of around 20mm. Sexually dimorphic, this one showed the pattern and colouration of a male. Migrant females have occasionally been known to produce another home-bred generation, but these typically have flight times in August and September. Although it breeds continuously within its home range of southern Europe and north Africa, Gem is considered unable to overwinter in the UK, strongly suggesting this individual was a true migrant.

The Suffolk Moths website lists on average around eight county records a year over the past 12 years, mainly at coastal sites, with the earliest adult on 9 May in 2021 and the latest on 25 November back in 1997. As light trapping refers to the night the light was switched on, this Gem record is now logged as 1 January 2022.

Captions:

(Top Left) Nycterosea obstipata

(Left) Map screenshot from Migrant Lepidoptera Facebook group, showing air mass characteristics for 1 January 2022.

However, not only is this the first January record for Suffolk, but Les Evans-Hill at Butterfly Conservation kindly checked the National Moth Recording Scheme database and confirmed that this becomes a national record too, the earliest prior to this being on 8 January 2012 in West Cornwall (VC1).

Obvious excitement at this discovery and its significance is tempered by the realisation that it’s yet another

References:

indication that global weather patterns are changing. However, moth records such as this provide additional evidence to support the now incontrovertible atmospheric data.

And the moth? After being photographed and spending the day resting up, it was gently released into a now cooler evening to continue taking its chances, unaware it had made moth history.

Waring, P., Townsend, M. and Lewington, R. (2017) Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland. Third Edition. Bloomsbury Publishing. London.

Data provided from Suffolk Moths www.suffolkmoths.co.uk and the National Moth Recording Scheme, courtesy of Butterfly Conservation.

Suffolk is very lucky to have large areas of land under public/charity ownership and some years ago, GeoSuffolk designated 29 Suffolk County Geodiversity Sites (CGS), all with public access. We chose them for their educational, research, aesthetic and/or historic potential and we monitor them on a regular basis to check that the geology remains accessible. From April 2021, as covid -19 restrictions eased, CGS monitoring, which is mostly outdoor work, presented itself as an appropriate project for

GeoSuffolk to undertake. By the end of September we had monitored: Thorpe Ness; Thorpeness Cliff; Spa Gardens, Felixstowe; Nacton Cliff; Bridge Wood, Nacton; Newbourne Springs; Newbourne Great Pit; Harkstead Cliff and Shore; Aspal Close, Beck Row; Lakenheath Church; Christchurch Park, Ipswich; Holywells Park, Ipswich; Pocket Park, Ipswich; Needham Lake Erratic. I have chosen three to exemplify the variety of our county ’s geology and which can be visited by all.

Harkstead Cliff and Shore CGS is designated for its Harwich Formation and its Pleistocene gravels and ‘brickearth’ deposits. It is in the Stour Estuary SSSI but, unlike the geology of nearby Stutton and Wrabness, Harkstead is not in the citation. It has important research potential and the CGS designation gives it some added protection. The cliff was in excellent condition when we visited. The photograph shows horizontally bedded Harwich Formation clay with ash bands (yellowish) and the ‘Harwich Stone Band’ near the base of the cliff, and with fallen blocks on the foreshore. The top of the cliff shows patches of contorted Pleistocene gravel. We found the orange silty ‘brickearth’ deposit in the southern part of the cliff and on the shore. Bill George’s article ‘A Geological Field

stead, Suffolk

Suffolk Natural History no. 56 is recommended reading before you visit.

Occasionally, Pleistocene gravels provide us with giant specimens – the Needham Lake Erratic CGS is one such example. We love our big stones in Suffolk, presumably because there is so little ‘hard’ rock in the county, and this one was designated for its educational value. Children in particular enjoy it and it has inspired

the installation of an artificial climbing rock nearby. Needham Lake Country Park is Suffolk’s most popular inland outdoor tourist attraction, and this erratic has the added benefit of provenance and fossils, neither of which are common attributes of our big stones in Suffolk. It was dredged from the gravel pits that predated the lakes, and lithology and fossils identify it as Cretaceous Spilsby Sandstone –brought from the area of present -day Lincolnshire by the ice sheet.

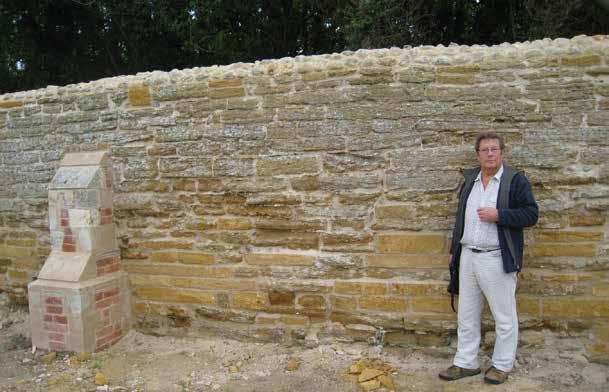

Past cold climate events have also shaped our Suffolk landscape, with the best examples preserved in the Breckland area. Aspal Close CGS has been designated for its relic periglacial landforms –a multitude of ground -ice hollows amid the ancient oak parkland in this West Suffolk County Park. The photograph of GeoSuffolk/ SNS member Barry Hall standing in a hollow shows their approximate size –two or three metres deep and a few tens of metres across. The details of their origin are unknown, but proximity to the Fen edge, with the

that solution processes during permafrost conditions played a part. These are relic landforms and need protection – once they’ve gone, they’ve gone! My article ‘Dips and Dells at Aspal Close’ in White Admiral no. 83 gives more ideas on the origins of these landforms.

The full list of CGS is at https:// geosuffolk.co.uk/index.php/geologyand-sites.

Image Captions:

(Opposite - Top Left) Harkstead Cliff September 2021

(Inset) Fossil molluscs in the Needham Lake Erratic August 2021

(Top Right) Barry Hall standing in a hollow at Aspal Close – photo by Judith Hall August 2021

A while ago several recorders came to do a baseline survey of this piece of land recently handed into the care of Creeting St. Mary Parish Council and they are now seeking volunteers to help maintain it – as well as someone to oversee the whole project. It is hoped that the advice given will be considered and it will not just be viewed as a ‘park’ for dog walkers.

It is a two-acre piece of re -generating agricultural land, originally given to Needham Market Town Council by Mrs. Lilley and extends from the sewage works north along the east bank of the River Gipping (though the river path is not part of the land).

Lilley’s Wood is not a wood as such but land that was previously under cultivation. It is part of a registered County Wildlife Site covering the whole of the regenerating woodland between Flordon Road and the sewage works along to Coddenham Road and the car boot sale area. As such it has been extensively surveyed for its wildlife interest (chalk downland plants which are rather rare in the area). The chalk pit adjacent we believe supplied the flints for the buildings at Alder Carr Farm.

Suffolk Naturalists’ Society recorders and the Suffolk Wildlife Trust have

carried out surveys and agree that the grassland is of the greatest importance as it hosts not only orchids – sometimes in abundance - but many other interesting plants. There is a good mixture of shrubs providing food, shelter, and nest sites for birds. A constant effort bird study was carried out for many years so the species using the site are well documented. In addition, the RSPB is funding a Turtle Dove feeding project on the field adjacent because the area has been identified as having nesting potential (the birds have been seen and tried to nest in the past).

The ecologist’s recommendations were as follows: The chalky soils on the site have given rise to a diverse plant community including several notable species such as yellow-wort, burnet saxifrage and ploughman’s spikenard. Ant hills are numerous in open areas. Patches of bare ground and short turf created by rabbit grazing are additional wildlife features. The mosaic of habitats present on the site is of high ecological value for a range of taxonomic groups including birds, reptiles, orthopterans (grasshoppers), butterflies, hymenopterans (bees) and other pollinators.

The aim of future management should be to maintain the existing mosaic of different successional stages from bare patches, rabbit grazed and disturbed ground, species -rich, short, and long grass, young, scattered scrub and blocks of dense scrub of high value for breeding birds and invertebrates. It is recommended that non-native planted trees, particularly grey alder, are removed as soon as possible as they are regenerating and encroaching in the open glades. Plastic

tree guards are littering the ground in a few places and should be removed if possible.

Further surveys would guide management but generally it can be seen that much could be achieved in the first instance by controlling the blackthorn and non-native trees to maintain grassy areas of floristic interest – and remove the plastic tree guards. Decisions need to be taken on how to balance public (and dog) access with the needs of the wildlife.

The local patch has never been that great for nature, a series of equestrian and agricultural fields right on the edge of northwest Ipswich, just outside Whitton. It ’s the place where I access nature and I know the area by hand, so in that context it is important to me. However, it never offered anything rare or unusual, and I got used to that, never expecting much. It was then a surprise to discover a colony of pyramid orchids within this intensively farmed area, as if were diamonds in the rough.

The area where they were found was an agricultural field left to become seta-side in 2018, I guess because it had

become too infertile for crops exhausted by intensive farming.

In the first year, 2018, I was surprised to find some orchids growing in a small colony, with the flowers becoming more numerous the next year, in 2019. By 2020 several hundred spikes had bloomed in what was a small patch of land, and it was obvious something exciting was happening.

With the strange weather of 2021 I wasn’t sure if the orchids would flower. When I looked in early June it wasn’t looking too promising as none had appeared, so I thought the colony had maybe died out. However, with a further look in late June, I was

absolutely surprised to find that masses of orchids had flowered in amongst the long grass, completely taking over the area. In a rough count, over 1,100 spikes had flowered, which is a good number when you consider this land was used for crops just several years ago. It just shows how set-a-side can be so important to wildlife in intensively farmed environments.

I had always assumed pyramid orchids were plants of unimproved, uncultivat -

ed land, land that had been undisturbed for millennia, until I found this colony in some set -a-side. Although pyramid orchids are one of the commonest of that type of flower it was still a great boon finding a colony in such an unusual place.

I don’t know who owns the land or if they know they have orchids growing in the fields, I only hope the colony grows in strength, through careful management or just left on its own, so maybe it can thrive into the future.

Landguard is somewhere no selfrespecting dragonfly enthusiast would ever visit to look for these insects. The site has a natural spring fed pond on the northern half of the nature reserve, a pond in a concrete gun emplacement plus a small, lined pond in the mouth of the observatory Helgoland trap. Additions to areas of

water in 2021 were a new raised pond alongside the cottage garage plus a small, lined pond in the cottage garden. Very few species live & breed on site with most records being of transient individuals. A drought in the hot summer of 2020 resulted in just 12 species noted which was followed by the long, prolonged cold spring and

early summer of 2021 producing an unexpected and unprecedented 21 species recorded.

Three species were recorded for the first time. The “Butts Pond” on the northern part of the nature reserve was responsible for two of these species. Scarce Emerald Damselfly Lestes dryas was first noted in Suffolk in 2007 (Mason et al 2016) with very few Suffolk sites still now, all close to existing populations in North Essex & South Norfolk. The species likes ephemeral ponds which are prone to drying out in the summer. Surely a female briefly visited the Butts Pond unseen in 2020 and left some eggs which developed when the pond refilled in 2021.Two were seen from July 15th to 19th & one from August 20th to 21st.

Also, at the Butts Pond two Southern Migrant Hawker Aeshna affinis were seen July 5th with exuviae also noted from which they had emerged. Further records were one July 8th, one August 11th, two 12th, one 14th, one 19th, one September 4th & one 22nd. The species was first noted in Suffolk in 2015 (Mason et al 2016) and this is another species that likes ephemeral ponds that dry out in summer so, presumably, a female had visited in 2020 unseen when this pond consisted of just a bit of wet mud.

The final new species added to the Landguard list was a Lesser Emperor Anax parthenope on June 14th which is another species only noted in Suffolk this century for the first time but is unlikely to breed at Landguard.

Reference:

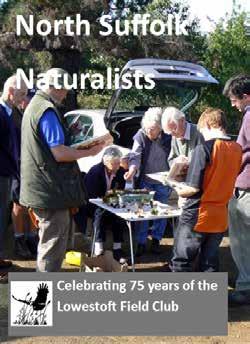

The Lowestoft Field Club was founded in 1946 by a group of naturalists to record wildlife in the Lowestoft and North East Suffolk area. It has thrived throughout that time and has produced a unique and detailed record of the region’s flora and fauna in its annual reports. Over 75 years the Club has visited at least 290 different sites, most in Suffolk, with occasional excursions over the border in to Norfolk! Its records chart the decline of some species such as Turtle Dove and House Sparrow but also monitor the increase

of others that have moved in to the region. These include birds such as Collared Dove and Little Egret, insects such as Willow Emerald Damselflies and plants such as Bilbao’s Fleabane, to name but a few. The Club’s reports are a valuable resource for researchers and can be used to assess some of the effects of climate change in our region. They are sent annually to be included in the database held by the Suffolk Biodiversity Information Service.

Today the Club still meets throughout the year with outdoor meetings to enjoy Suffolk’s wonderful wildlife sites and to share observations in indoor meetings, complemented by visiting speakers. As such, it is the only naturalists’ Society that has regular outdoor meetings. Experts amongst our members can identify birds and mammals, insects and other invertebrates, flowering plants, ferns, mosses, liverworts and fungi.

To celebrate its 75th Anniversary, with the generous financial assistance of the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society, a celebratory booklet has been produced in which members review the Club’s history and the changes that have taken place in their specialist fields over the years.

The contributions made by previous members are celebrated, with another section including photographs of a selection of the outdoor meetings held in the past. This is followed by a review of a ‘ Top Ten’ of our most favoured sites. Finally, profiles are included of some of the current

members and their specialist interests. The Club would like to encourage SNS members and anyone interested in wildlife, of any age, from beginners to experts, to attend our meetings, where you would find a warm welcome.

Further details and copies of the programme can be obtained from our secretary :Mr T. Brown, 4 Clare Road, Kessingland, Lowestoft, NR33 7PS. E mail :- tonybrownrwt@gmail.com

Indoor meetings are held on Wednesdays at the United Reformed Church, London Rd North, Lowestoft, at 7.30pm.

Photos taken by members and details of forthcoming meetings can also be found on the Lowestoft Field Club Facebook page.

If you would like a printed copy or a PDF. version of the 75 Years Celebration Booklet, please email :- mark.smith29@btinternet.com

Colin Hawes

In late September 2021, while about to cross the Stutton Mill Stream from the parish of Bentley into the adjacent parish, there were what appeared to be several otter spraints (patches of faeces) on the right -hand bank. A hint of a musky, sweet smell came from the faeces, an odour that helps identify otter spraints. After taking photographs of the spraints, one of them was collected in a clean ‘doggy poo’ bag to take home for further

investigation. A month or so later, the bag’s contents were emptied into the bottom of a shallow dish of water and examined using a binocular microscope. Magnification revealed the spraint contents to be several small feathers and some small broken, hollow leg bones, the latter looking as though they had been crunched. Otters feed on a wide variety of prey but mainly fish, especially eels. However, they will also take frogs,

crayfish and occasionally water -birds, for example moorhen and duck, especially their young. The feathers and hollow, crunched pieces of bone in the spraint were evidence that a small bird had been caught and eaten, possibly a young moorhen. Otter spraints may be important in communication as they can discriminate between spraints of different individuals.

Other local evidence of otters includes: one seen by the bridge adjacent to Little Dodnash Farm, Bentley; several sightings at Belstead Brook, especially near the sluice close to Bourne Park, and very recently, two caught on camera taking fish from a pond in the Copdock/Washbrook area. Otters are essentially solitary but if an otter group is seen it is likely to be a female plus her young of the year.

Otter habitat comprises lakes, rivers, streams and marshes but they are

capable of overland journeys between such habitats, sometimes over considerable distances. Home ranges vary greatly in size, depending on food supply. They have very few natural predators but humans are responsible directly or indirectly for most known mortality, they are especially vulnerable to interference from river management, human recreational activities, water pollution, and road traffic.

Otters are protected throughout Britain under the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981). Habitat protection is the principal method of conservation. Please report any sightings of otters or other mammals to www.suffolkwildlifetrust.org and to suffolkmammals@sns.org.uk.

It was with much delight that I watched, over a few mornings in early April, a couple of moorhens ( Gallinula chloropus) constructing a nest with short lengths of dried-up triangular stalks. What was surprising was that the nest was being assembled right next to a brick wall (on the office side) surrounding the ‘Haywain’ pool at Flatford Mill (TM 077332). It was being built on what looked like a mass of dead and decaying ‘floating’ vegetation. I had with some dismay watched, early in the year, the mass cutting back and removal of healthy populations of flowering rush, pendulous sedge, branched bur -reed, arrowhead and reed sweet grass from

a large area in front of the culverts conducting Stour waters from underneath the mill buildings. Of course, this was simply a management strategy to reduce silting up and all those plants were sure to return. But an activity like this always leaves behind debris which in this instance had drifted to the side of the pool. It was on these floating remains that the nest had been crafted (see photo 1).

One morning I noticed the female was not on the nest, so I ventured behind the wall above the nest and caught sight of an elegant clutch of eggs, eight in all (see photo 2). I did think it was a bit brave of them to construct a nest seemingly without much support

underneath. I retreated quickly as I saw the female flagging its yellowtipped red bill speeding towards the nest.

For those who know Flatford, you also probably know how water levels around the mill can fluctuate widely. There only has to be some rain in the Stour catchment the night before for the levels to go up quite markedly the following day.

Just when I was getting accustomed to seeing the occupied nest every morning during my walk, my cheerfulness quickly changed to disbelief and despondence one morning when I noticed that not only had the nest gone but also the supporting floating vegetation. All swept away! The water level was high and the wall completely bare. Relentlessly the water was still gushing out of the culverts – the result of heavy rain the night before. I

peered over the wall but there was simply no sign of the eggs. To birds, nothing could be worse then loosing a clutch of eggs. All that preparation and energy just down the drain! And just when the 3 -week incubation period must have been coming up. And no sign of the parents either. Nature can be cruel!

However, nearly three weeks went by before I re -heard the familiar kek-kek croaks coming from some emergent vegetation further up the millstream. And as I focussed my binoculars onto the Glyceria fronds, a red/yellow beak came into view, and then the second one. My heart warmed up. It was good to see them again! Great, I thought, hopefully they were nesting again. With interest, I looked for them each morning I passed by, and it was over a month before I spied a chick, perhaps there were more. Yet it was another fortnight in mid -June that I could be

certain there were four in all (see photo 3), ungainly long-legged and getting big fast. Grit, tenacity, and

resilience on the part the parents had paid off. ‘If at first you don’ t succeed, try again’, nature’s motto.

published as a hardback by William Collins price £20

Richard StewartAccording to the website of the Suffolk Traditional Orchard Group Suffolk in the early 1900’s had over 6000 orchards. I grew up in what was then a small Norfolk village where orchards were common. These were usually small and to the far end of long back gardens. They were part of a partial self-sufficiency that meant some people seldom visited Norwich, just six miles away. My widowed mother supplemented her meagre income by selling spare Beauty of Bath apples to the village store. Now things have changed and according to ‘Wild Suffolk’ Spring/Summer 2021, celebrating sixty years of the Suffolk Wildlife Trust, there has been an estimated loss of 85% of all orchards. One factor besides grubbing out is neglect, epitomised by the orchard in Christchurch Park Ipswich, once with fertile fruit trees and a long hedge of native species, supplemented by buckthorn planting to attract egg laying brimstone butterflies. It was neglected long before vandals burned

down its thatched building yet a few carefully planned work parties could restore it.

Consequently, this book by Benedict MacDonald and Nicholas Gates, the latter also providing most of the colour plates, is an important contribution about the rich biodiversity that orchards can provide. The orchard studied in detail is in the Malvern Hills, and initially there is a helpful map covering its different habitats then a brief history of orchards, with the actual word progressing from ‘garden yard’ to ‘fruit garden’, with almost all of our cultivated species originating from the foothills of Kazakhstan. The importance of pre-Dissolution monasteries is stressed not just for propagation but also actual spread of orchards. This was reversed in the 1970’s and 1980’s which saw grants for orchards to be ‘grubbed relentlessly from the British countryside ’. Both authors stress their good fortune and privilege to have long term access for their studies from ‘the best wildlife

farmer that I’ve ever met’. The chapters cover each month of the year, both writers taking turns and with no diminution in the quality of dual writing that I could detect. Each chapter is prefaced by suitable quotes from a wide range of sources: Dickens, Shakespeare, Keats, Auden, Thoreau and an African proverb, to name just a few. The orchard itself has been free of any chemical use since the 1930’s and its interconnected and rich biodiversity is perhaps best exemplified by a list of nesting birds, most in decline nationally. These include willow tit, spotted flycatcher, lesser spotted woodpecker, redstart and bullfinch in ‘intricate pair bonds ’. As many as ten pairs of blackcaps overwinter and the rotting fruit has attracted an incredible five hundred plus visiting fieldfares. Goshawks hunt in the orchard and other wildlife covered includes a wide range of trees, vital subterranean fungal networks, battling stag beetles ‘like Sumo wrestlers ’ and an abundance of bat species. Thankfully they also champion ivy, much

Trevor Goodfellow

On my daily walks wandering the garden and field margins, I often find droppings, feathers or feeding signs that intrigue me.

maligned but offering in autumn ‘the latest opening restaurant in town ’ as the umbels come into flower and a ‘thermal winter blanket’ for hibernating and roosting species. The authors also provide many ideas for creating similar wildlife habitats and the July chapter was an inspirational idea, moving the reader to the still existing abundance of small orchards in the Carpathian mountains of eastern Europe where there is ‘an older way of managing the countryside’ and consequently ‘the remarkable soon becomes the everyday’.

This book won the Richard Jefferies and White Horse Bookshop award for nature writing in 2020 and it is also important because the decline of orchards has received much less publicity compared to similar declines in unimproved meadows, peat bogs and ancient woodlands, probably because many of the surviving orchards are commercially managed and privately owned.

I therefore purchased a book (a few in fact) specialising in tracks and signs and with the support of other specialist books, and of course the

internet, I now manage to identify the species most likely to have left their marks.

Winter is a good time to get out and about if there has been some snowfall. Our large pond sometimes freezes over and if the snow settles on the ice for long enough, it is eventually covered by hare, pheasant, moorhen, fox, and other tracks.

Otters regularly visit in the winter months, and I have traced their steps by following their tell-tale footprints with an S shaped mark made by their tail. The most obvious sign they have been is dead fish hauled from the water, even from under the ice, with a bite taken from them. Spraints too can signify where they have entered or left the water.

Nibbled bark of small trees or scores where they rub their antlers tells me that deer have passed through, usually 60cm high = muntjac and 70cm = roe deer.

In the summer, badgers leave their calling card by clawed scent marking on trees or more often, the obvious tell, is a hole in the ground where a bee’s nest once was. Even ground nesting wasps are not exempt from the badger’s excavating.

Scats and pellets are an interesting subject as I am sure Chris Packham would agree. I often find the sausage shaped pellets of barn owl in the cart lodge where a roosting barn owl might have been and sometimes the smaller pellets of a little owl.

Badgers have not exactly been a friend of the hedgehogs here killing many of them a year or two ago, leaving prickly husks after eating them. The resurgence of hedgehogs was pleasing after I found a wet, black, slug like dropping on the lawn. After setting out trail cameras, I recorded both hedgehog and unfortunately badger. Feeding signs can be tricky but with a

little patience one can at least take an educated guess. Leaf damage may point the finder towards moth or butterfly larvae and holes or nicks maybe leaf cutter bee or sawfly. The latter are obvious when the larvae are feeding, and they will strip a small tree or bush in no time leaving leaf veins at the most.

Years ago, I found 10mm holes near the ground on our poplar trees and after lots of monitoring, I eventually discovered that they were hornet moth (Sesia apiformis ) larvae exit holes. Also, just recently I found feeding galleries in a dying willow bush that was cut down. I only noticed this when I split the logs for firewood, so I strapped the split sections back together and crossed my fingers. I put the log in a sheltered wet corner and checked it regularly but silly me I should have netted it, as I later found a hatched chrysalis in an exit hole. My chance to prove what it was, gone. It is very likely that this was a lunar

Trevor Goodfellow

December 2020 was the wettest December I recorded here in Thurston since I arrived in 2007. This was followed by the wettest January (2021).

Our seasonal ditch which we call ‘the

hornet moth (Sesia bembeciformis) whose larvae live for 2 years feeding inside the trunk or branch and later exiting near ground level like the hornet moth.

Feathers may be easier for a birder to identify although some that I find remain a mystery. The easiest may be the jay’s wing tip, the small vivid iridescent blue feather is unmistakeable.

Owl’s feathers appear different with the help of a hand lens - the adaptions to facilitate silent flight can be seen.

In the area that you are familiar with, you may know what birds are about and a process of elimination would be key. Nocturnal birds may however be off your radar.

I strongly advise readers to familiarise themselves with tracks and signs as the subject is both interesting and often revealing.

Books: Animals. tracks and signs –Hamlyn Guide and Bloomsbury pocket guide to tracks and signs.

moat’ hosts smooth and great crested newts (GCN) and they had their best year with nearly a hundred GCN counted on one night.

The lake desilting interfered with future toad and frog population and

Buzzards are much more common nowadays and in January, one fed daily on fish carcasses left by otters. Once stripped to the bone, a kestrel found morsels too.

Red Kite are becoming a more frequent sight which are always a treat

Stoat and weasel by day and badger and fox by night all find something to

unfortunately despite moving thousands of tadpoles to safer places, I saw no evidence that any survived.

The toad/frog count was down on the average, but hopefully immature ones will show through this Spring.

Despite the desilting upheaval, odonata did very well, probably helped by the saving of about 40% of the lake water. Another reason for the plethora could be that some larvae that might have taken 2 years to mature, might have matured earlier through some kind of trigger, perhaps, I am no expert. 16 species showed but the missing 2 species: small red -eyed damsel and hairy dragonfly, were not seen.

Sightings of yellow wagtail, siskin, and brambling were pleasing though fleeting.

I just recently found a dead juvenile barn owl in the garden and when I weighed it the scales showed 200 grams, suggesting that it starved. The adult barn owls have paired and seemed to be finding voles.

It was an average year for moths too as I recorded 342 species which includes 20 new species towards the 730 accumulated list. All records were sent to Suffolk Moth Group.

We planted another 100 or so trees which all needed good protection from deer damage. Muntjac seem to be the worst for ring barking young trees and roe deer, grazing a little higher are a pest too and between them they would ruin a few trees each night.

Now this is January 2022 (feels strange even writing that) woodpeckers are drumming and blue tits guarding potential nest boxes.

The Dixon family moved to Suffolk (to near Hadleigh) in 1950, with Roger when aged 8 being sent to St Andrew’s school in Eastbourne. In 1960 the family moved to Melton Hall near Woodbridge, with Roger attending Stowe School in Buckinghamshire. In 1968 Roger commenced reading Geology at Kingston Polytechnic (Kingston University, London). He also joined the Ipswich Geological Group and one of his undergraduate projects – Foraminifera from the Scrobicularia Crag at Chillesford - appeared in IGG Bulletin 12 (1975). In 1973 Roger was

appointed Demonstrator at North London Polytechnic (North London University), enabling postgraduate research into the Red Crag. His thesis ‘Studies of the Mollusca of the Red Crag….’ was submitted for a University of London PhD in 1977 with the section on Neutral Farm, Butley appearing in IGG Bulletin no 19 (1977). Roger then moved to Shoreham -bySea, teaching Geography at St Mary ’s Hall, Brighton from 1978 -1991. After being runner up in the Sussex Evening Argus - Segas Cookery Competition 1978, he edited (1986) the St Mary ’s

Hall Cookbook. A move to Saxlingham Thorpe near Norwich saw him running a B&B which won national accolades. He became a regular contributor to Suffolk Naturalists’ Society publications, including on Sutton (2006 and 2009); Bawdsey; Nacton and Harkstead (2012); and Dunwich (2013). He also (2000) edited the Geological Society of Norfolk ’s 50th Anniversary Jubilee Volume. In 2001 Roger moved to Woodbridge, helping to set up GeoSuffolk in 2002 and becoming its Treasurer. He also became Overseas Field Excursions Secretary for the Geologists’ Association – he ran the 2002 GA trip to Gondwanaland of Southern Africa. He married Rosie in 2011 and, with her help, produced ‘A

Celebration of Suffolk Geology’, GeoSuffolk’s 10th Anniversary volume in 2012, engaging 40+ authors, obtaining sponsorship, and writing three articles himself – the Silurian borehole of Stutton; Building Stones; and a culinary trawl through the Red Crag. Roger and Rosie then moved to Eastbourne. Roger was a keen traveller and, only last year, he published (‘Kept me well-occupied during lockdown’, said Roger) ‘The Mabel Trail….’, a Great Aunt’s 19091910 world tour diary together with his own tour in her footsteps. Roger and Rosie also visited Suffolk to investigate property – the Red Crag was calling him. But it was not to be, for Roger died on June 21st 2021.

‘ A good friend and fellow Crag enthusiast for over 50 years ’

Bob Markham‘A good friend and fellow Crag enthusiast for over 50 years ’

I wrote this in GeoSuffolk Times no. 50. How better to remember Roger than by looking back at Saturday 22nd May 2010, a day spent on the Bawdsey peninsula? This was a Geologists ’

Association field meeting – Roger and I were leaders, ably helped by others. But it was Roger who organised, wrote, and produced field notes for the participants, and afterwards wrote up the meeting in a professional journal (Proceedings of the GA, vol. 122, 2011, pp 514-523).

Photo Captions: (Top Left) Waldringfield Heath Pit

September 1973: Working towards his PhDdecalcified Red Crag with trace fossils tubes. Photo by Bob Markham. (Top right) Butley Forest Pit CGS October 2012: Demonstrating the Red Crag and its current bedding at a field meeting. Photo by Caroline Markham. (Opposite) Rockhall Wood SSSI, Sutton November 2012: Overseeing the clearing of a face of Coralline Crag. Photo by Caroline Markham.

Handed out at the start of the meeting, the field notes included maps, directions and much to look forward to. At Sutton Knoll SSSI the sections had recently been cleared by Natural England and by GeoSuffolk members. We were promised both Coralline Crag and Red Crag; fossils including one of Britain’s largest brachiopods; a ‘Pliocene Island’; and pits with names like Bullock -yard pit and Chicken-pit. (Were there still

bullocks and chickens in them?) We would also visit the intriguingly named ‘Pliocene Forest’. The next stop would be to see the London Clay (and some Red Crag) at Bawdsey where storms had recently removed the shingle beach and the cliff section was being rapidly eroded. We would finish the meeting by visiting Red Crag pits at Alderton and at Ramsholt. Safety information was not forgotten – we were informed about tetanus; tides

(low tide, Caroline Markham noted was at 12.58 for Bawdsey); that London Clay was extremely slippery to walk on; and that toilets were not usually available. Most sites were on private property with permission obtained.

So how did the day go? It was gloriously sunny, as it often is for visits to Suffolk geology. Sutton Knoll was visited first, with excellent exposures of Coraline Crag and some Red Crag, with interpretations as ancient cliffs, wave-cut platforms and beaches being the subject of much discussion. Barry Hall then guided us around the Pliocene Forest’, where a new extension (its enclosure funded by the

GA’s Curry Fund) was officially opened by GA member David Bone cutting a traditional red ribbon. The party then drove to East Lane, Bawdsey (and a lunch break), where the London Clay and overlying Red Crag were being actively eroded. Here, the fossil find of the day was undoubtedly a lower cheek tooth of a rhinoceros, found in the Red Crag by David Bone. Coastal protection boulders provided additional interest at this site, with Larvikite from Norway and Carboniferous Limestone from France. The party then drove to a Red Crag pit at Alderton, where Roger produced a percentage frequency table of

Ben Heather

In January, Discover Suffolk, Suffolk County Council’s guide to getting outdoors, launched a brand new app. The Discover Suffolk App was created as part of a two-year project funded by Suffolk County Council’s ‘Suffolk 2020 Fund’ with the aim to raise awareness of the countryside, and to promote outdoor activity to new and existing audiences.

The app contains over 100 guided walking, cycling, riding and easy access trails throughout the county. It is also a handy tool for anyone who enjoys the great outdoors by giving it’s users

molluscs, his work showing that sublittoral Glycymeris and Venerupis molluscs were replaced by intertidal Mytilus and Mya towards the top of the section, reflecting shallowing water depths. The final step of the day was a Red Crag pit at Ramsholt. Besides the usual fossil shells, one person found a much rolled (and derived) belemnite. The meeting ended at 17.30 after a splendid day with Roger.

A list of Roger’s many publications has been published as GeoSuffolk Notes no.72 see https://geosuffolk.co.uk/ index.php/archive/geosuffolk -notes

free access to high quality Ordnance Survey mapping and accurate GPS location tracking.

To find out more about the app and to download it for free please visit https://www.discoversuffolk.org.uk/ discover -suffolk -app/ or scan the QR code below.

The Suffolk Naturalists’ Society offers six bursaries, of up to £500 each, annually. Larger projects may be eligible for grants of over £500 – please contact SNS for further information.

Activities eligible for funding include: travel and subsistence for field work, visits to scientific institutions, scientific equipment, identification guide books or other items relevant to the study.

Morley Bursary - Studies involving insects (or other invertebrates) other than butterflies and moths.

Chipperfield Bursary - Studies involving butterflies or moths.

Cranbrook Bursary - Studies involving mammals or birds.

Rivis Bursary - Studies of the county's flora.

Simpson Bursary - In memory of Francis Simpson. The bursary will be awarded for a botanical study where possible.

Nash Bursary - Studies involving beetles.

Applications should be set in the context of a research question i.e. a clear statement of what the problem is and how the applicant plans to tackle it.

Criteria:

1. Projects should include a large element of original work and further knowledge of Suffolk’s flora, fauna or geology.

2. A written account of the project is required within 12 months of receipt of a bursary. This should be in a form suitable for publication in one of the Society's journals: Suffolk Natural History, Suffolk Birds or White Admiral.

3. Suffolk Naturalists' Society should be acknowledged in all publicity associated with the project and in any publications emanating from the project.

Applications may be made at any time. Please apply to SNS for an application form or visit our website for more details www.sns.org.uk/pages/bursary.shtml.

The Suffolk Naturalists’ Society, founded in 1929 by Claude Morley (1874 -1951), pioneered the study and recording of the County’s flora, fauna and geology. It is the seed bed from which have grown other important wildlife organisations in Suffolk, such as Suffolk Wildlife Trust (SWT) and Suffolk Bird Group (SBG).

Recording the natural history of Suffolk is still the Society ’s primary objective. Members’ observations go to specialist recorders and then on to the Suffolk Biological Records Centre at Ipswich Museum to provide a basis for detailed distribution maps and subsequent analysis with benefits to environmental protection.

Funds held by the Society allow it to offer substantial grants for wildlife studies.

Annually, SNS publishes its transactions Suffolk Natural History, containing studies on the County’s wildlife, plus the County bird report, Suffolk Birds (compiled by SBG). The newsletter White Admiral, with comment and observations, appears three times a year. SNS organises two members’ evenings a year and a conference every two years.

Subscriptions to SNS: Individual membership £15; Family/Household membership £17; Student membership £10; Corporate membership £17. Members receive the three publications above.

Joint subscriptions to SNS and SBG: Individual membership £30; Family/Household membership £35; Student membership £18. Joint members receive, in addition to the above, the SBG newsletter The Harrier.

As defined by the Constitution of this Society its objectives shall be:

2.1 To study and record the fauna, flora and geology of the County

2.2 To publish a Transactions and Proceedings and a Bird Report. These shall be free to members except those whose annual subscriptions are in arrears.

2.3 To liaise with other natural history societies and conservation bodies in the County

2.4 To promote interest in natural history and the activities of the Society.

For more details about the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society contact:

Hon. Secretary, Suffolk Naturalists’ Society, c/o Ipswich Museum, High Street, Ipswich, IP1 3QH. Telephone 01473 400251

enquiry@sns.org.uk