From the editor

Hi everyone,

Firstly I must apologise for the delay in getting this out. I had a rather unprecedented incident in my life recently that really threw everything off kilter, but should be back on track now.

I hope everyone had a lovely summer, although a rather cooler one than last year’s heatwave. Did anyone notice any changes in the flora and fauna of the county and if so, could it have been brought on by the noticeable changes in our climate? This highlights the importance of recording so that variations in nature can be seen and examined.

Don’t forget that our Autumn Members Evening is coming up on 16th November at Alder Carr Farm, near Needham Market. I hope to see you all there and please bring along any nature curiosities to place on our nature table. This gives others the chance to see things they may have never seen before. Details on page 19.

We’re also looking for members who want to get more involved in the society. We need someone who would be happy to arrange field trips for starters. We held a couple this year that were well received but unfortunately, I do not have enough free time to organise anymore. We also need members to staff a stall at some events over the next year to talk to people about the society and what we do. Maybe even get some new members, who knows!

All the best.

White Admiral 113 2

Editor Hawk Honey 1 Felix Cottage Athelington Rd, Horham, IP21 5EG whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com

Rasik Bhadresa

It was at the end of June that I received an Email from Harry Elliott (Ecology Tutor at Flatford Mill Field Centre) inviting me to a 7.45am opening of a moth trap (‘attractor’ possibly a better description) switched on the night before. I replied instantly, ‘I will be there!’. It fitted perfectly with my daily morning walking routine. As usual I left home at 7 and made it to the lawn of the 14th century Valley Farm (TM077332) in good time. The moth light was still on. Gingerly, I approached the fairly large stand-alone trap (Photo 1) under the old Mulberry tree (laden with juicy mulberries! Yum yum). Through the somewhat cloudy acrylic lid which had moths and flies clinging to its underside, I spied something quite amazing, an Elephant Hawkmoth Deilephila elpenor. My mind went ‘wow’! I had never seen one before! Just as I was admiring it, the light went off and a few seconds later appeared Harry with lots of little plastic jars for collecting specimens for identification later. He was delighted with my news.

White Admiral 113 3

Top: Moth trap awaiting inspection.

Right: Elephant Hawkmoth, Deilephila elpenor.

Slowly he lifted out the lid and put it aside and gently removed the first of several layers of egg trays. It was like opening Christmas presents! Straightaway we enthused about the sculptural shapes, markings and colours of these fascinating creatures as we started taking a closer look at them, one at a time. For identification purposes, Harry collected those macro moths he was not too sure about. As expected, the Leopard Moth Zeuzera pyrina was playing dead! The Elephant Hawkmoth was simply stunning, greeny-olive-brown with splashes of pink, not only that but also we uncovered a total of seven, yes seven - the most Flatford had ever recorded in their years of trapping. We made sure Small Elephant with the unusual posture of hind wings being held forward was an excellent discovery.

There was one exciting species after another: the (often referred to Burnished Diachrysia moth the Buff-Tip Heart and Dart Agrotis exclamationis, the Black Arches Lymantria monachal to name but a few. There was also one specimen of the ‘notorious’ Box-tree Moth Cydalima perspectalis, glistening white with dark borders, a species which we had incidentally earlier discovered as an infestation of caterpillars on our box topiary at home!

White Admiral 113 4

Left: Gently extracting the moths from the trap. Right: Leopard moth, Zeuzerapyrina

Mother of Pearl Pantaniaruralis

Harry had ‘potted’ quite a few other moths for identification later. Everything else, including a lot of micro moths, were released safely under the shade of trees. It had been an incredible morning.

Extremely pleased, I thanked Harry profusely and took off for the rest of my walk, with beautiful colours and shapes crowding my mind.

Three weeks later I had another Email from Harry inviting me (as a friend of Flatford Mill) for another moth session. This time we came across quite a different array of moths, amongst them the Pine Hawkmoth Scalloped Oak Crocallis elinguaria, Dingy Footman a bit of a mouthful Brownline Bright Rosy Footman Miltochrista miniata. Also I must mention the micro moths Ringed China-mark Parapoynx stratiotata Mother of Pearl Patania ruralis. Although many of the micros are smaller, a lot aren’t and the former one with a wing span of around 3cm and the later one 4cm, they were amongst these. It is really genital differences that set micros apart from macros but even more importantly the micros emerged much earlier than the macros on the Lepidopteran family tree!

The wide variety we had seen was mainly an expression of the varied habitats abounding in the vicinity of the trap: conifers, mixed hedgerows, beech and yew hedges, grassy and marshy areas, scrub, woodland, extensive fruit and vegetable beds, poplars, willows.

White Admiral 113 5

Left: Poplar Hawkmoth, Laothoe populi. Right: Burnished brass, Diachrysiachrysitis

While the larvae of some moths had very specific requirements, quite a number were generalists. However, what we had glimpsed was merely the tip of the iceberg (some 900 species of macros have been recorded in the British Isles!). But to claim to have any understanding of emergence and behaviour patterns of different species, one would have to conduct periodic trapping over longer time periods.

Bottom left: Buff-tip Phalerabucephala.Bottom centre: Peppered moth Biston betularisBottom right: Black Arches Lymantriamonacha

But what is certain is that moth trapping has to be one of the most delightful nature’ experiences. When one considers the amazing life cycles of moths, their habits, larval food plants, flight seasons, habitats, and the variety of shapes, colours, textures and markings, one can only

There are literally thousands of stories scattered throughout the Moth Kingdom. The study of their English names too is absorbing and fascinating. My recommendation to you: get a moth trap (or make one!) if you haven’t got one already! And ‘bonne chance’.

White Admiral 113 6

From left to right: Heart and Dart Agrotisexclamationis,Pine Hawkmoth Sphinxpinastri, Brown-line Bright-eye Lacanobiaoleracea,Rosy Footman Miltochristaminiate.

Jeremy Mynott

Jeremy Mynott

Most readers of White Admiral will be familiar with Shingle Street on the mainland Suffolk coast opposite the southern end of the Orfordness spit. The hamlet itself is built on an extensive spread of shingle in front of Oxley Marshes and the shingle banks in front of the line of houses support important communities of rare and protected flora within an SSSI.

Since 2012 we have been conducting regular surveys of the vegetated shingle to record any changes to the diversity and distribution of the vegetation cover. This is a dynamic environment, affected by long-shore drift and storm events that can cause either erosion or, as in recent years, depositions of shingle, in which new configurations of the shingle-banks can be rapidly created. A particular purpose of the surveys is to assess also if there is evidence of anthropogenic impacts on this sensitive environment attributable to increased visitor numbers or changing recreational activities. The surveys have all been carried out by teams of local volunteers, led by professional ecologist Toby Abrehart, and the latest was conducted on 2 July 2022, ten years on from the first.. 1 We again recorded key species in a series of parallel transects. The plant community on the foreshore continues to be dominated by Sea Kale Crambe maritima, Curled Dock Rumex crispus littoreus, Yellow-horned poppy Glaucium flavum, Sea Beet Beta vulgaris maritima together with some Sea Pea Lathyrus japonicus, but Orache Atriplex spp., which is more sensitive to shoreline trampling, was absent from the study area this year.

Left: Yellow-horned poppy Glauciumflavum

White Admiral 113 7

Moving further inland, these communities are joined by larger drifts of Sea Pea and other typical species such as Sea Campion Silene uniflora, Stonecrop Sedum spp., Lichen spp., Buck’s-horn Plantain, Plantago coronopus and Sheep’s Sorrel Rumex acetosella.

A useful innovation for the 2022 survey was to supplement the data with high-quality drone images, which graphically confirmed that the areas most affected by trampling are largely concentrated in the two ‘corridors’ leading from the two car parks to the sea and in the narrower one either side of the popular ‘shell-line’. These strips are virtually bare, but though no part of the study area is entirely free from human disturbance the main plant communities in-between are fortunately still well represented and flourishing.

The two largest changes since 2012 are: first, that the study area itself has increased by nearly 2.5 hectares as the shoreline has progressively retreated and so supports more vegetation overall; and second, that False Oat-grass Arrhenatherium elatius is now

well- established on the ridges nearer the houses, creating an extensive new habitat that attracts hares, skylarks and associated insect life. The overall picture is therefore quite positive, though there are warning signs that continuing vigilance will be required to safeguard these important and vulnerable habitats, of which the residents are effectively the custodians on behalf of the designated AONB and SSSI authorities.

1 We would like to acknowledge a generous grant from the SNS supporting this 2022 survey. The full technical report can be viewed on the Shingle St website at http://www.shinglestreet.org/wp- content uploads/2022/10/SS-survey-report-2022-final.pdf.

White Admiral 113 8

Patrick Armstrong

There are a few Roman and Norman French elements in East Anglian place-names, but most place-name elements in the region are of Viking (Scandinavian, 9th and 10th century) or Anglo-Saxon origin (5th - 8th century). Thus many familiar Suffolk place-names are of quite ancient origin and interpreting them is sometimes a matter of conjecture. Also, very similar place-names may have very different origins. Some interpretations are controversial.

Common Suffolk place-name elements include -ham, -ton and -ing, sometimes in combination. Ham, from a very early time meant home, or homestead or group of homesteads. Tun or Ton originally meant enclosure, but by extension an enclosure round a homestead. Ing implies a personal or family name. Thus Framlingham, in East Suffolk can be interpreted as ‘the ham of Fram’s people’; for Dennington, not too far distant, ‘the tun of Denegrifu (a woman’s name)’ has been suggested. Many of Anglo-Saxon names are simple topographic descriptions –Depden might be a rendering of ‘Deep dene’ or ‘Deep valley’. The old English words for wood, hill, stream, slope are often incorporated into East Anglian place-names. Woodland may have long since been cleared, but tree-names may be perpetuated in ancient names. There is a large group of parishes in East Suffolk all with the name of South Elmham, their being distinguished by the dedication of the village church – thus South Elmham St Margaret, South Elmham St Nicholas… … St Cross, All Saints, St James, St Michael. Until the devastation wrought by Dutch elm disease, elm was a common enough tree species in the Suffolk countryside. Some hedgerow specimens remain. The name Occold remembers another tree species‘Oak copse’ - Oakley, perhaps ‘glade where oaks grow’ according to Eilert Ekwall’s English Place-names, is just a few miles north of Occold in the Waveney Valley. The word ‘oak’ also appears in farm names nearby. Ash trees are also remembered. Ashbocking was originally just Ash: the ‘bocking’ coming from a land- owning family. One Ralph de Bocking held the manor in 1338.

White Admiral 113 9

Some East Anglian naturalists will have learnt some of their ecology in Dodnash Wood, in the Stour Valley, as it is close to the Flatford Mill Field Centre (no confusion over that name!).This woodland’s name is possibly derived from ‘Dudda’s ash’. The name (or something like it) has been known since the 13th century. There are still ash trees in the wood, but some reports state that a number of them are diseased.

Plants other than trees have often given their names to locations, The element ‘Red’ may often be derived from ‘reed’. Redgrave Fen (which, along with Lopham Fen, nearby), constitutes an important wetland nature reserve, in the Waveney Valley, West Suffolk, may possibly have a name derived from ‘Reed grave’, the second word meaning simply ‘ditch’, rather than an interment.

The attractive village of Peasenhall, according to Ekwall, despite in the recent past holding a ‘Pea Festival’ and having peafowl wandering around the village, may have been named after some wild plant resembling a pea: marsh trefoil was suggested.

Cultivated plants make their appearance. The element ‘haver’ is said to be derived from the old Scandinavian hafri – oats. This would make Haverhill in West Suffolk ‘the hill where oats are grown’.

Yaxley, close to Eye, is named for the cuckoo: ‘the woodland clearing where the cuckoo calls’ The Old English name for the species was geac, apparently pronounced ‘yay-ack’. Although a cuckoo appears on the village sign the species now calls less frequently in Suffolk than a few

White Admiral 113 10

Left:

The church of St Margaret, South Elmham, Suffolk (Village website)

Right:

The cuckoo’s call is now quite rare in Eastern England, but its former presence is indicated by the occasional place-name. (Archibald Thorburn, c 1920)

decades ago. In Anglo much more abundant.

Lapwings are still reasonably common, however. It has been suggested that the two sister villages Tivethall St Margaret and Tivethall St Mary, just across the border in Norfolk may be named after this species, the onomatopoeic ‘peewit’ being an alternative name: the old form is tewitt or tewhit.

White Admiral 113 11

Lapwings or peewits: Remembered in a few East Anglian placenames. (Archibald Thorburn [1915]).

Another village on the border, just in Norfolk, is Brockdish. In some parts of the country the element brock- might be evidence of the existence – or former existence - of badgers nearby. But the opinion is that in this instance the name is built from ‘brook’ and ‘edisc’, Old English for ‘enclosed pasture or park’. The settlement is right on the River Waveney.

However Foxhall, near Ipswich was ‘Foxhola’ – Fox-hole - at the time of the Domesday Survey (1086), so the association with foxes and foxes’ earths seems pretty firm.

The now rather archaic word ‘hart’ refers to a male red deer (the female is a ‘hind’). The name of Hartest, another attractive village, between Bury St Edmunds and Sudbury, was probably derived from ‘Herthyrst’ , ‘stag hill or wood’. Suffolk, a little surprisingly, is said to have England’s largest population of red deer, a species often now associated with the upland regions of Scotland.

The old name for rabbits was coneys, and the element coney is occasionally met with in field-names or informal names for patches of open ground - former rabbit-warrens perhaps. But rabbits were not introduced into the English mainland until the thirteenth century (about 1235 – they were apparently on the Isle of Wight, Lundy and Isles of Scilly earlier), and so are unlikely to appear in village names of Anglo-Saxon origin. Where it does occur in East Anglia, as in Coney Weston, it seems to have been derived from a word element meaning ‘king’ or ‘crown’ Hence ‘The king’s tun’. Things are not always quite what they seem.

Unsurprisingly domestic mammals occur in place-names. Oxen were last used for ploughing in England in the 1840s, but their memory lingers in some parts of the country. There are few ‘Ox’ place-names in East Anglia, but Suffolk’s Yoxford has been interpreted as ‘a ford that could be passed by a yoke of oxen’.

Place names thus can tell us not only something of the people who settled an area, over a thousand years ago, but also something about what was important to them. In an agricultural society that lived close to nature, the plants and animals were a very immediate part of their surroundings and were often remembered in their descriptive place-names. They provide a clue to the ecology and land-use of former centuries. Sometimes the species they noted are still to be found nearby, but in some instance things have changed enormously.

White Admiral 113 12

The following is an email I received from one of our members:

Dear Hawk

This email comes from a very ancient member of SNS (1948). It was provoked by Patrick Armstrong’s fascinating article on Bishop Edward Stanley. He also mentions Bishop Whittingham who was a good friend of my grandfather, Canon A.P Waller. With Claude Morley, my grandfather was one of the founders of the SNS. He and the Bishop started collecting moths using a white sheet and an oil lamp. One night they were out on the Hemley marshes on the banks of the river Deben when they were spotted by one of my grandfather’s parishioners. The whole village was alerted and ever since it was thought that there were ghosts out there. Their other method of collecting was with a mixture of treacle and rum and I remember my grandfather telling me of one evening when he had daubed this mixture on several tree trunks in the Rectory garden. The intoxicated moths were dropping to the ground where they could be easily recovered and boxed. When first a frog and then several toads appeared they were soon gobbling up this feast. Within half an hour all were drunk and rolling on the ground. With mercury vapour moth traps these days there is no such entertainment! My first moth trap was the GPO’s red telephone box at the top of the road near the Rectory. It had a permanent electric light and conveniently placed air vents near the top for the moths to enter. All I had to do was to visit the telephone box early every morning. There was often a financial bonus too since several customers had not pressed the money -return button. The modern mobile phone can not produce such experiences.

My grandfather was a well known amateur entomologist who contributed to Richard South’s The Moths of the British Isles published by Warne. The 1948 printing was one of my standbys. My grandfather was regularly in correspondence with the recorder of moths at the London Natural History Museum, appropriately named Baron de Worms. Having met him I can confirm that it really was his name Perhaps it is not surprising that the British clergy produced a lot of amateur entomologists in the 19th and early 20th Centuries since they only worked one day full time a week. No less than five Wallers were men of the cloth and succeeded each other at Waldringfield so I speak with some experience.

Alfred Waller (reproduced with permission).

White Admiral 113 13

My husband, Rob, and I visited Broomheath yesterday afternoon, in particular, to look for Purple Hairstreaks. Whilst there we also noticed activity on the sandy patches near the benches.

There were several Bee-wolf Wasps including these in the photographs taken by Rob. One female had a paralysed honey bee beneath her but was actually mating at the same time, when the male disengaged and flew off, not without difficulty I should add, the female wasted no time in digging a burrow to take the bee into.

We understand that the species is increasing in numbers but they were fascinating to observe and probably easily overlooked.

Thanks for sharing Kerry. If you have any photos you want to share, please send them to us:

whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com

White Admiral 113 14

Caroline Markham

Caroline Markham

GeoSuffolk’s new leaflet records an aspect of our earth heritage, the historical use of the Rock-Bed as a building stone before it passes from public memory. The Rock-Bed is a creamy-yellow limestone with fossils of marine shells. Those made of aragonite have been dissolved by acidic ground water and their calcium carbonate precipitated to harden part of the Coralline Crag into the Rock-Bed. Fossils made of less soluble calcite - scallops, sea urchins, bryozoans - remain.

A Rock-Bed block in Chillesford Church tower showing fossil bryozoans (corallines) from which the deposit derives its name.

The leaflet has a selection of photos of Rock-bed exposures – most of them are SSSIs and almost all are on privately owned land.

White Admiral 113 15

The pit in the grounds of Orford Castle is the only one with public access to the deposit in situ and for this reason GeoSuffolk has designated it a County Geodiversity Site.

The Rock-Bed in the Orford Castle pit is relatively soft, and quite overgrown in summer, but well worth a visit.

The rock is quite soft when dug out but hardens after a few days as its contained moisture evaporates – ideal for Medieval stone masons! The entire outcrop is criss-crossed by a series of fissures (near vertical faults) at right angles to one another. These facilitated quarry-working with many of the old quarry faces aligned along them. The leaflet documents some of the structures built using Rock-Bed including Chillesford Church, Greyfriars wall in Dunwich and Orford Castle interior, all of which have public access.

White Admiral 113 16

The Coralline Crag is a marine deposit formed some 3.5-4 million years ago. It is unique to Suffolk, extending across the Orford/Aldeburgh area, reaching the coast at Thorpe Ness. Here it extends for about 3km as undersea rocky ridges which obstruct southwards-moving beach material.

White Admiral 113 17

Much of the east wall of Greyfriars Priory in Dunwich is built of blocks of Rock-Bed.

Small blocks of Rock-Bed on Thorpeness beach - thrown ashore from the submarine outcrop during storms.

This has accumulated at the Ness and helps to protect the Sizewell power stations. (See Where is Thorpeness? In White Admiral 84, Spring 2013.)

Thank you to the Coralline Crag landowners for their help and interest and Coast and Heaths AONB for support through their Community and Conservation Fund. Suffolk’s Coralline Crag Rock-Bed can be found at various outlets around Aldeburgh and Orford and downloaded from the Archive https://www.geosuffolk.co.uk

Is your contact information correct?

From time to time, we change email address, or home address and we forget to let others know. If you’ve changed your details recently, please let us know by contacting enquiries@sns.org.uk

Could it be you?

We are looking for an events co-ordinator to help plan field trips and possibly volunteer events for the Society and its members. Interested?

whiteadmiralnewsletter@gmail.com

White Admiral 113 18

Thursday November 16th 7pm

Alder Carr Farm, Creeting St, Mary, nr. Needham Market, IP68LX

7pm. Chat and Refreshments - complimentary tea/ coffee & biscuits (Alcoholic beverages - beer/wine/ soft drinks are available to purchase), followed by speakers with a further break for refreshments.

"Show and Tell" nature table, please bring along your items of natural history interest.

Natural history books -bring and buy, lend out or give away.

Natural history equipment to sell or share.

Full Programme of talks on Page 29

Directions

from A14 at A140 junction take signs to Needham Market, take 2nd exit right onto Flordon Road; take 1st left and 1st left again (St. Mary's Rd)

From Needhan Market High St. take sign to The Creetings - same side as the Church (Hawks Mill St).

Train - It is a 10 minute walk from Needham Market station. A pick up can be arranged. Train times are convenient from Bury St Edmunds and Ipswich

what3words: farm/renders/influence

White Admiral 113 19

Autumn 2022 was an astonishingly good time for abundant fruiting of edible, and not so edible, Agaricus species – so-called ‘true mushroom’ species - in particular. Autumn 2022 was a bumper year at Milden with Field Mushrooms Agaricus campestris fruiting profusely in places that usually only have one or two at best, pushing up through our neighbour’s recently cultivated naturally regenerated grass and along our grass margins around arable fields. The poisonous Inky Mushroom A moellerii, fruited in one spot in secondary woodland on the farm – only the second time I’ve found it here in the last 30 years. Several of the edible red-staining (to varying degrees) woodland mushrooms were all observed around the farm in 2022 including the Blushing Wood Mushroom A sylvaticus, the Almond-smelling Prince A augustus and the Tufted Wood Mushroom A impudicus.

In 2019 the Yellow Stainer A xanthodermus grew plentifully in long winding troops, with hundreds marching over the lawn and grazed pasture – and it was fairly abundant in autumn 2022 too. And in 2019 the very rare Medusa Mushroom A bohusii grew abundantly in small areas of ancient woodland. In 2014 the edible Macro Mushroom

A urinascens (syn macrosporus) grew to the size of dinner plates with a chunky stature. And every year, in the same place, the uncommon SaltLoving Mushroom A bernardii which looks very like the Field Mushroom pops up on our lawn next to the farm drive.

White Admiral 113 20

Juliet Hawkins

Yellow Stainer Axanthodermus

Right: Salt-Loving Mushroom A.bernardii

In other years we get other Agaricus and several in our lawn that have remained unidentified.

There are an estimated 40 or so British Agaricus species and Geoffrey Kibby, the country’s leading mycologist, says that “despite a number of major works on the genus in the last 100 years, the genus Agaricus remains a difficult and at times frustrating group to study. The often rather uniform appearance both macroscopically and microscopically serves to make identification at species level challenging” (Kibby, 2011). Well aware of this ‘challenging’ group but armed with some excellent Agaricus identification books and keys, and useful diagnostic chemical Potassium Hydroxide, I spend many hours identifying mystery Agaricus look-alikes – and often end in disappointment without a definitive identification. So, when I get fuzzy photos emailed with ‘Can I eat this?’ or ‘This mushroom doesn’t have any yellow staining and it peels so I assume it’s OK?’ type of questions or arrive home to find someone at the house waiting for me to identify their specimens before they eat them, alarm bells ring! So, to clarify, before delving deeper into the Agaricus genus, I rarely eat wild mushrooms – for several reasons.

We only have one life and the more I know about fungi, the more I realise I don’t know and even experts don’t know, so whatever is the point in risking this precious time we have on eating something that might prove fatal or dodgy? The average fungi identification book only lists a few of the more common Agaricus species which means many are trying to ‘fit’ identification features to a species in the book!

White Admiral 113 21

Tufted Wood Mushroom

A.impudicus

Inky Mushroom

A.moellerii

Roger Phillips’ brilliant Mushrooms and other fungi of Great Britain 1981 & 2006) bravely assesses edibility of lots of species but very few books do. And the ones that highlight the best edibles, with warnings of poisonous look-alikes, are usually very brief indeed. Even if one has the best books and a microscope to go with it, and if we get the identification right, are we sure that we won’t get a stomach upset because it affects me differently to someone else, or you simply had a glass of wine with your mushroom dish. The Common Ink Cap Coprinus atramentarius is poisonous if combined with alcohol consumed 48 hours either side of your ink cap dish, inducing vomiting, palpitations, diarrhoea and even hospitalisation (Harding et al, undated). There is so much we don’t know.

Yellow warning colour – but not always

All Agaricus species are superficially similar –they have free gills that mature purple-brown, a ring that may fall off, and a very dark brown spore print. Field characters such as the colour of flesh, cap and stipe is helpful when identifying Agaricus species. Most foragers, even beginners, would discard a yellow-staining Agaricus, such as the Yellow Stainer A. xanthodermus, as suspicious and not worth risking a stomach ache for. But finding and assessing the yellow-stain and taking into account other diagnostic features takes care. Sometimes the cap and the flesh of the Yellow Stainer hardly stains and if you cut/break off the base of the stipe (stem) when picking it, you can miss the tell-tale chrome-yellow colour at its base. The Yellow Stainer A. xanthodermus (the most commonly occurring Agaricus mushroom) appears to be very poisonous to some with sweating, stomach cramps and upsets, but others have no obvious adverse side effects.

The very dark-grey or blackish-capped and poisonous Inky Mushroom A. moellerii has white flesh except for the tell-tale chrome yellow in the

White Admiral 113 22

stipe base. However, both the cap of the edible Horse Mushroom

A. arvensis ages brassy yellow with age or handling and its flesh can be pale yellow on cutting. Another edible, the Wood Mushroom

A. sylvicola, always found in woodlands, is faintly yellowish in the stipe base.

Other essential or useful diagnostic field characters include the texture of the cap; the length, shape and texture of the stipe and its flesh colour; the structure of the ring on the stipe and the way it is connected; and odour such as almonds, aniseed or even urine, which can be very strong. A drop of caustic soda, diluted Potassium Hydroxide, on the cap surface can produce a helpful positive or negative reaction on the cap. Many species will require measurements of mature spores under a microscope and even analysis of cheilocystidia (large cells found on the gill edges). And, of course, some really good mushroom books (see the reference section). However, for many Agaricus species, DNA sequencing may be the only sure way of identifying a specimen.

A cautionary tale from Norfolk serves to demonstrate that colour, or the absence of yellow on a specimen, is not a reliable identification feature – and how difficult so many Agaricus are to identify. After DNA sequencing to establish the garden lawn culprit of a mushroom poisoning of a North Norfolk couple, a non-yellow-staining mushroom A. bresadolanus was found to be the cause, effecting both victims rather differently with vomiting, abdominal pain and dizziness symptoms for a few hours to several days (Edwards & Leech, 2014). Whilst rather uncommon in Britain, this species does occur in visible, frequented places such as parks and lawns. Edwards & Leech point out that none of the regular fungi books that enthusiasts might have on their shelves would have assigned the A. bresadolanus identification correctly even with microscopic features. They suggest that “the advice that ‘true’ mushrooms that do not turn strongly yellow on bruising, and that

White Admiral 113 23

do not smell ‘phenolic’, are edible, must be revised” (Edwards & Leech, 2014)

Blushing Wood Mushroom

A.sylvaticus

Whilst identification of Agaricus species sounds difficult, armed with good books and some time, many are do-able and a good genus to get your teeth into (forgive the metaphor). Fungi need enthusiasts to record and improve our knowledge but not necessarily the foragers. There is so little really wild habitat in Suffolk that even if we every forager picked one and left nine more specimens for the invertebrates, by the time several foragers have been through a well -walked wood or meadow, there wouldn’t be much left for the moth and beetle larvae to feed on or to shed spores. When a recorder has finished identifying a specimen, it can be thrown back where it came from to scatter its spores to the wind – and colonise somewhere else.

References

Edwards, Anne & Leech, Tony (2014) Agaricus bresadolanus - a toxic mushroom, Field Mycology Vol 15(4) – see https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/fieldmycology/vol/15/issue/4

Harding, Patrick, Lyon, Tony, & Tomblin Gill (undated) How to identify Edible Mushrooms, Collins

Kibby, Geoffrey (2011) The genus Agaricus in Britain, self-published

Kibby, Geoffrey (2021) Mushroom and Toadstools of Britain & Europe, Vol 3

Phillips, Roger (1981 and updated 2006) Mushrooms & other Fungi of Great Britain & Europe, Pan Books

Sterry, P & Hughes, B (2009) Collins Complete British Mushrooms and Toadstools: The essential photograph guide to Britain's fungi, Collins

White Admiral 113 24

For those of you with an interest in our Diptera fauna, I caught this fly (see right) on 21st August this year at in my garden at Hollesley. It was caught by my moth trap. It is Tachina magnicornis. I identified it as such but was rather hesitant owing to it supposedly only being found in the Channel Islands for the UK. So I posted it on the Diptera UK Facebook site asking for expert opinion. It has been confirmed as T. magnicornis which is similar to T.fera as the first mainland UK confirmed record. However it is very likely that more will be found. There are a number of differences between the two species in which only the male characters have been used to separate them. However the easiest to look for are that the frons at its narrowest point is significantly wider than the width of the eye. It is less than 1.08 for T.fera and the fore tarsal claw is around the length of the last tarsal segment. T.fera has a claw as long as the last two tarsal segments.

Raymon Watson

White Admiral 113 25

Left: Moth fly - Psychodidae

By Stewart Belfield.

White Admiral 113 26

Right: Wasp spider at Aldburgh by Dot Richards

Belowleft: Black Sexton Beetle Nicrophorus humator and below right: Noon fly Mesembrina meridiana from Bill Davis’ garden in Bungay

Below: A blowfly Stomorhina lunata from Brantham.

Justin Gant

Left: Convolvulus Hawkmoth Agrius convolvuli by Alan Thornhill

Andrew Goodall

There have been so many amazing photos on our Facebook page that there’s not enough room to show here. Please keep sharing though and importantly of all, keep recordingthosesightings.

White Admiral 113 27

Musk thistle and a lovely bumblebee enjoying its flowers at CWS Baylham. Paul Gilson.

Left: A beautiful male Hornet Vespa crabro enjoying the Ivy flowers at Hinderclay.

White Admiral 113 28

Left: Bird’s nest fungi at SWT Lackford lakes

Right: Devil’s Coach Horse Ocypus olens casts its curse in the editorsgarden

Left: Lesser Willow Sawfly Nematus pavidus in Liz Cutting’s garden in Bently

This will be a ‘hybrid’meeting’with some speakers on Zoom, if technology allows.

7.30 – on Zoom - a talk on Birds and People -

Andrew Gosler Professor of Ethno-Ornithology

Oxford

His work inspired Gen Broad’s current project on what birds mean to people in Suffolk.

After this in no set order, each about 10 minutes :

David Basham about his bee nest project at Westerfield funded with an SNS bursary.

On Zoom

TobyAbrehart on the Shingle Street flora

Colin Hawes on Stag Beetles

Simon Jackson – update on the Ipswich Museum developments

Ross Piper on something entomological

Hawk Honey on the possibility of holding Society field meetings in 2024 and other things.

Rather invertebrate themed - but they are "the little things that run the world"!

If you would like to give a talk on a subject of your choosing at a future members’ evening, please let us know.

White Admiral 113 29

Trevor Goodfellow

Home highlights of 2023 for me came in many forms. Last year I saw my first Clifden Nonpareil (Blue underwing) moth Catocala fraxini and this year I counted 4 possibly 5 separate individuals indicating that they are possibly breeding in our poplars or our solitary aspen tree, it remains for me to monitor these in 2024. Hornets were a constant problem as they killed, cut up or ambushed moths as they reached the light trap and even cutting the wings off and escaping the trap.

Other moths new to my list were: Oak Rustic –Dryobota labecula, Tawny Wave – Scopula Rubiginata, and Gypsy Moth – Lymantria dispar to name just a few of 33 new species here. Box-tree moths Cydalima perspectalis were found for the first time in the garden which was not really a surprise as we have many Box bushes, all of which now show larval feeding damage. This recent ‘Asian invader’ is now rampant causing many garden centres and nurseries to stop selling Box trees, instead, a similar looking species of Euonymus is offered.

Box-tree moth

Cydalimaperspectalis

Repeat sightings of Hornet –Sesia apiformis, Lunar Hornet –Sesia bembeciformis, and 6belted – Bembecia ichneumoniformis

Clearwing moths confirms that they survived last year’s drought.

A record annual count of well over 420 species of moth recorded using MV Robinson, 12v Actinic heath and LED Skinner traps plus daytime observations

Caterpillars of Eyed Hawkmoth and Pebble Prominent were found feeding on saplings of white willow and aspen respectively.

sponsa.

White Admiral 113 30

A pleasant surprise to find a common Emerald damselfly after several years of absence and the return of Small Red-eyed damselflies which were not seen after lake desilting, have now re-established.

Willow Emerald damsels still in good numbers and pond skaters –Aquarius palladum still thriving.

An occasional sighting of Ravens flying overhead, and more frequent Red Kite could only be topped by an autumn sighting of a Short-eared Owl, another first for home. First sighting of Nuthatch on the feeders and regular Sparrowhawks about too. no evidence that our Barn owls bred successfully after having Kestrels nest a few feet away rearing four young.

White Admiral 113 31

Left: Clifden nonpareil Catocalafraxini

Right: The tell-tale diamond shaped tail of a Raven Corvuscorax

Below: Emerald Damselfly Lestes sponsa.

Right: Short-eared owl Asioflammeus

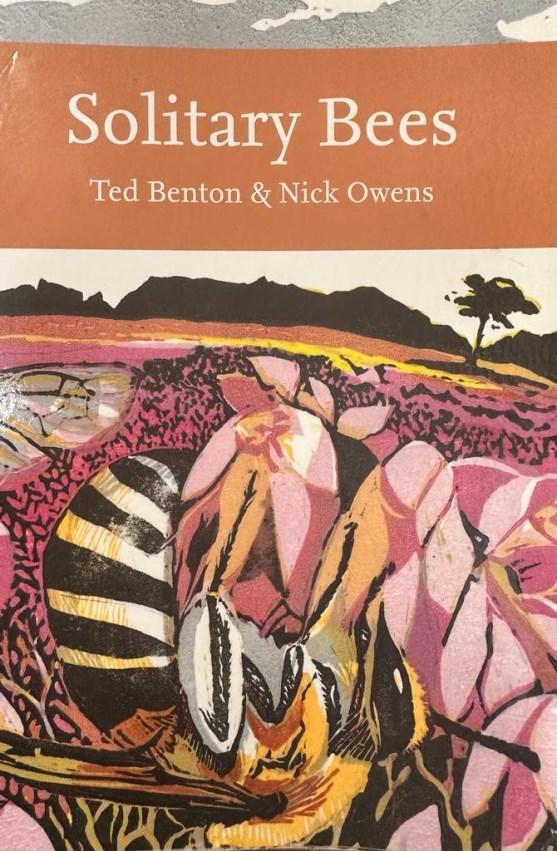

Solitary Bees by

Ted Benton & Nick Owens.

New Naturalist Library, published by William Collins, 2023, 496pp. Softback £27.00

ISBN 978-0-00-830457-7.

Anyone familiar with the long-standing New Naturalist series will know what they are getting for their money: a tour de force of the subject at hand, and this latest offering is no exception. This is not an identification guide and nor does it set out to be. Rather, the authors’ stated aim is to explore the behaviour and ecology of the 240+ solitarynesting bees within the U.K.

Chapter 1 explores the diversity of bees within the topic, describing basic characteristics of each family and the main genera within. The nature of a solitary (versus social) nesting system is discussed as is the occasional instance where the differences between such life-cycles becomes blurred.

A large part of the book is rightly dedicated to the relationships between bees and flowers, including their pollen and nectar resources. The book draws heavily on worldwide research as well as published work from, the U.K. and is liberally augmented with personal experiences and observations from the authors.

However, the authors readily admit that there remains many gaps in our knowledge concerning these vital insects and this book should go a long way towards inspiring new generations to fill the gaps through further research, evoking the spirit of Sir Issac Newton’s “standing on the shoulders of giants”.

White Admiral 113 32

Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society

Suffolk Naturalists ’ Society