Publicaþie/Publication

Catalog editat de/Catalog published by:

ªtefan Rusu - curator independent

Proiect lansat de/project launched by:

Centrul pentru Arta Contemporanã [KSA:K], Chiºinãu

E-mail: ksak@art.md , Web site: http://www.art.md

Curator - ªtefan Rusu

E-mail: rusu@art.md

Proiect finanþat de/project supported by:

Centrul pentru Artã Contemporanã [KSA:K], Chiºinãu

Fundaþia SOROS Moldova/SOROS Foundation, Moldova

Co-finanþat de/co-financed by: OSI Budapesta, Cultural link program, Pro Helvetia/Arts Council of Switzerland Reseaux

Est–Ouest Under the Auspices of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation

Coordonare tehnicã/Technical coordinator: Veaceslav Druþã

Suportul tehnic/Tehnical support: Marin Turea, Vitalie Stelea

Centrul “CONTACT”- Aliona Niculiþa, Slavian Scafaru

Publicaþie editatã cu suportul/Publication supported by:

Fundaþia PRO HELVETIA/ Arts Council of Switzerland

Reseaux Est-Ouest Under the auspices of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation,

Fundaþia SOROS Moldova, programul Artã ºi Culturã/SOROS Foundation, Moldova, Arts &Culture program

Redactor/Editor: ªtefan Rusu

Traducere/Translation: Iulian Robu

Redactare texte/Copy editing: Iulian Robu

Fotografii/ Photo credits:

Evghenii Ivanov, ªtefan Rusu, Octavian Eºanu, Ron Sluik, Yerbossyn Meldibekov, Piotr Wyrzikovsky, Nenad Andric, Kisspal Szabolcs

Texte/Texts:

Natalia Abâzova, arheolog/archeologist

Pavel Parasca, doctor în istorie/PhD in history

Vladimir Bulat, critic de artã/art critic, e-mail:vbulat@k.ro

ªtefan Rusu, curator, e-mail: rusu@art.md

Emil Dragnev, doctor in istorie/PhD in history, e-mail: emildragnev@yahoo.com

Eugen Bâzgu, architect.

Octavian Eºanu, e-mail:o_e@art.md

Alexandru Antik, artist, e-mail: antik@idea.dntcj.ro

Mulþumiri/Thanks to: Complexul Muzeal Orheiul Vechi/Muzeum complex Orheiul Vechi, Muzeul Naþional de Istorie/National Museum of History, Ministerul Apãrãrii/Ministry of Defense, Muzeul de Arheologie ºi Etnografie/Muzeum of Archeology and Ethnography, Lilia Dragnev, Nicolae Avornic, Gabriela Colþea, Larisa Bârsa.

Concepþie graficã, editare/Layout, printing:

Eugen Coºorean, IDEA design&print Cluj adresa/address: str. Paris 5, Cluj, Romania

+40-260-194 634

invasia

Orheiul Vechi / Moldova 2002

4

Mai multe feluri de invazii

Societatea de consum este, prin însãºi politica sa de a se impune viguros, aproape ireversibil, o invazie. Chiar din start voiesc a clarifica termenii problemei luate în discuþie. Teza mea este urmãtoarea: “imperialismul multinaþional” (Frederick Jemison), care se extinde acum spre Est, îºi ”exportã” în regiunile pe care le controleazã ºi formele sale culturale, precum ºi discursurile instituþionale aferente; acestea reprezintã un efect al “hegemoniei capitalului” (Okwui Enwesor). Încerc sã descriu o schemã ºi lanþul de elemente care articuleazã ideea de invazie în materie de artã contemporanã, una din manifestãrile acestui “imperialism”.

O invazie armatã, din cele mai vechi timpuri, þintea ocuparea de teritorii, strivirea forþei militare inamice, înfrângerea (sau mutilarea) fizicã ºi moralã a stãpânitorului peste teritoriile jinduite. Când puterea simbolicã este rãpusã, pilonii pe care aceasta se sprijinã – se surpã fulgerãtor. Haosul este frate bun cu Thanatos. Aburii lui încep sã planeze imediat ce frica, oroarea ºi anxietatea pun stãpânire pe câmpul de luptã, în tabãra celor cãrora le-a fost hãrãzitã ruºinea, umilirea, defensiva ºi înfrângerea.

Ei, bine, numai unii sunt nãscuþi sã fie biruitori. Sau poate existã puteri nevãzute care “aranjeazã” de aºa manierã lucrurile? Privind înapoia noastrã, ajungem sã vedem mai mulþi învinºi decât biruitori. Mai multe cadavre decât monumente. Ruinele împânzesc lumea, sãrãcia este la ordinea zilei, în cele mai multe pãrþi ale planetei. Ruinelor li se adaugã altele, tot mai apãsãtoare, mai jenante. Lumea este plinã de contraste, diferenþele modeleazã ºi dicteazã politicile, discursurile, ideologiile.

Existã ºi invazii culturale, care funcþioneazã oarecum conform schemei de mai sus. “Performanþele democratice”, susþine Fukuyama, “depind nemijlocit de culturã”, referindu-se la soarta post-totalitarã a statelor din perimetrul ex-comunist. Valorile politice ale democraþiei occidentale se înrãdãcineazã cu multã dificultate în þãrile ortodoxe (Moldova, România, Bulgaria, Macedonia), precum ºi în cele musulmane (Kazahstan, Kirghistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenia), care întâlnesc o rezistenþã adesea crâncenã din partea culturii tradiþionaliste dominante, matriciale, paternaliste, adesea – resentimentar reziduale. Un anume tip de “naþionalism” îºi aratã colþii la toate nivelele; existã o coeziune (ºi o conlucrare) tacitã între forþele conservatoare (de orice naturã: politicã, culturalã, socialã, instituþionalã) în a se opune oricãror forme de nou ºi noutate. Asta este o luptã cu mizã mare.

În cazul Moldovei, pânã ºi noile tehnologii sunt grupate pe criterii etnice; existã furnizori de internet care o fac numai pentru ruºi, care acceptã (interesat) cã existã ºi o limbã “moldoveneascã” (Moldova Cyber Community), iar publicitatea (extrem de firavã deocamdatã) pe WEB este, aproape exclusiv, în aceastã limbã. Iar televiziunea cu cea mai mare audienþã este tot cea “naþionalã”, centralã, care emite doar câteva ore pe zi, în condiþiile unei cenzuri penibile ºi a unui control total asupra informaþiei difuzate. Un câmp televizual independent, privat, capabil sã contracareze ponderea ºi supremaþia quasi totalã a celui oficial încã nu s-a articulat. Au existat câteva tentative, dar aceste eforturi au fost împinse repede spre faliment. Cazul Catalan TV este de notorietate. Oferta TV prin cablu este flagrant limitativã, în care televiziunile ruse deþin majoritatea; acest lucru este reglat în bunã mãsurã de cerere, situaþie pervers speculatã de ideologii deznaþionalizãrii, de falsificatorii actuali ai istoriei. Moldova are o situaþie extrem de delicatã din punctul de vedere al potenþialului uman: câteva sute de mii de oameni au plecat peste hotare (legal ºi, mai ales, ilegal) sã munceascã, sã jefuiascã, sã se prostituieze. Existã, fireºte, ºi exemple onorante. Mulþi tineri ºi-au luat diplome “Magna cum laude” în diverse universitãþi strãine, europene ºi americane. Totuºi, aceastã þarã are o societate scindatã, unde civismul militant este umbrit în mod jenant de lupta rudimentarã pentru supravieþuire. Normalitatea este trãitã aici de doar o micã clicã de nouveax riches

Pe Dealul Schinoasei, în partea de nord a Chiºinãului, avem imaginea idilicã a “raiului” moldovenesc, populat de câteva zeci de vile ºi mici “palate” ale acestei categorii sociale – apãrute peste noapte, în jungla “capitalismului” local. Cred cã peste tot în estul european au rãsãrit astfel de enclave suprapãzite, spilcuite, pseudoamericanizate. Emanaþii sfidãtoare ale acelui sclipitor “Beverly Hills” transoceanic. Avem de-a face în esenþã cu o “altoire” a esteticii specifice habitatului standardizat american pe trunchiul unui model local de vieþuire normatã, cum era în oraºele din ex-urss. Case cu mult spaþiu interior, cu nelipsitul living ºi poate jacuzzi, dar în exterior vedem mai multe turnuleþe, balcoane, lucarne ºi acoperiº din tablã zincatã, mai rar cu olane, au apãrut într-un numãr mare cam peste noapte. Casele ºi vilele din acest perimetru au dimensiuni faraonice, iar fiecare dintre ele îºi “vorbeºte propria limbã” arhitectonicã. Practic, nu gãseºti douã edificii la fel. Nu se aseamãnã. Dar toate sunt împrejmuite, bine pãzite, cu porþi metalice, cu feronerie bogatã, cu sisteme sofisticate de supraveghere, iar zidurile lor funcþioneazã aidoma unor veritabile fortãreþe. Interesant este faptul cã aici îºi au locaþia ºi câteva ambasade, precum ºi unele familii de diplomaþi, afaceriºti. Cum s-ar spune, “aristocraþii” autohtoni au o vecinãtate onorabilã, din “lumea bunã”. E greu de ºtiut cine a avut primul ideea de a popula / defriºa acest perimetru: strãinii sau localnicii. Oricum, ºi unii ºi ceilalþi, se comportã ca niºte indivizi aparþinând aceleiaºi categorii sociale: noua tagmã a “globalizaþilor”. Semnele specifice sunt, în toate, la vedere. Cert este cã acum convieþuiesc laolaltã, într-o “comunitate sigurã”, într-o enclavã în care pot fi (sau cel puþin se cred) apãraþi, protejaþi, ascunºi de ochii impuri ai “proletariatului”, nepoftiþilor, amãrâþilor ºi sãracilor. Este imaginea posibilã a “ghetoului voluntar” descris recent de Zygmunt Bauman, adicã a acelui loc care îþi oferã pe deplin “sentimentul cald” al siguranþei: “Siguranþa ºi securitatea condiþiilor existenþiale poate fi cu greu cumpãratã bazîndu-te pe contul bancar – dar siguranþa locului poate fi cumpãratã doar dacã contul este suficient de mare. “Conturile bancare ale “globalilor” sunt, de regulã, suficient de mari. Globalii îºi pot permite în industria siguranþei echivalentul unei haute couture”.

Arta contemporanã – nu e locul aici pentru a defini acest concept atât de prolix ºi confuz – de la debuturile sale s-a arãtat multora ca o “invazie”, ca o formã de aplomb public, ca o lepãdare ostentativã a lestului tradiþiei. “Negativitatea avangardei” (Thierry de Duve) corodeazã temeliile culturii “afirmative”, fãrã a o nega, pentru cã are nevoie, pentru a exista, de contraste, de tensiuni, de stãri conflictuale…Tocmai lipsa unui consens asupra artei contemporane o face pe aceasta posibilã, reperabilã, analizabilã. Tradiþia ca bornã, ca element de referinþã, ca punct de plecare.

Ei bine, arta contemporanã, sau cum i se mai spune greºit de avangardã, are relaþii tensionate cu acea tradiþie pe care o gãseºte în acel sol în care este “importatã” sau “plantatã”. Tradiþia are rãdãcini viguroase, bine pãzite. Ea s-a constituit ca rod al efortului depus de generaþii de indivizi pentru care “plãmada” existenþialã o constituia chiar ceea ce ei numeau (ºi numesc) “tradiþie”. Este acel ceva infailibil ºi indestructibil, pentru care arta este doar unul dintre suporturi. ªi poate nu cel mai important. “ªcoalã naþionalã de picturã” sau “ºcoalã moldoveneascã de tapiserie”, sunt construcþii teoretico-ideologice (deloc persuasive) edificate pe un suport al sensibilitãþii þãrãneºti; acestea constituie practic primul moment în care moºtenirea trecutului se conºtientizeazã mai mult sau mai puþin ºtiinþific. Sugestiv mi se pare faptul cã despre aceste lucruri au început a vorbi tocmai cei din prima generaþie de intelectuali basarabeni postbelici, ei fiind educaþi într-o culturã sovieticã cosmopolitã, impersonalã, unicefalã, heteroclitã, depersonalizatoare. Contactul lor cu bagajul trecutului istoric era aproape nul, sau în orice caz, puternic diluat ºi mediat. Se naºte aici o chestiune foarte complicatã: în ce mãsurã niºte indivizi ºcoliþi într-o culturã “internaþionalistã” (cum s-a declarat a fi cea societicã), fãrã o legãturã directã cu ºcoala

5

interbelicã, sunt capabili sã poarte ºi sã transmitã altor generaþii “genele” tradiþiei “ancestrale” locale?

Greu de spus unde anume s-a nãscut arta contemporanã, pentru cã este aproape imposibil sã stabileºti produsul cãrei culturi este. Pãrinþii ei au fost niºte emigranþi, niºte dezrãdãcinaþi prin definiþie (Duchamp, Tzara, Joyce, Kandinsky, Jarry, Brâncuºi). Ea e perceputã ca ceva dat, ºi aplicarea criteriilor de judecatã formulate de modernitate par improprii pentru analizarea acestui tip de opþiune artisticã / plasticã. Cred cã existã o legãturã structuralã între “invazia” formelor politice ºi de coabitare socialã pe care ºi le doreºte / însuºeºte o anume parte a Europei – cea de dincoace de fosta Cortinã de Fier – , ºi cultivarea oarecum forþatã, programaticã a artei contemporane aici. Altfel spus, fenomenul este un implant cu care organismul cultural alogen se împacã destul de greu. Iar coabitarea este tensionatã. Este perceputã ca un corp strãin, iluzoriu, bastard, efemer ca un mereu ultim sosit. Arta contemporanã, în varianta sa “moldoveneascã”, nu a devenit nici pânã astãzi un fenomen prea agreat, admis la masã ca un egal. Ea este privitã ca o rudã “bogatã” care-ºi cam face uneori de cap, în voie – “pentru cã are de unde !”. Întreaga reþea a Centrelor de Artã Contemporanã Soros a avut multã vreme un statut privelegiat în toate statele unde ºi-a avut “tentaculele”, a epatat prin posibilitãþi financiare nelimitate, orice proiect era realizabil, orice toanã curatorialã, posibilã. Lumea venea la începuturi sã mai vadã “þãcãnelile” celor “de la Soros”. În anumite spaþii culturale injecþia aceasta de capital în realizarea de proiecte de artã contemporanã a avut efecte benefice în procesul de modelare a unui nou tip de conºtiinþã artisticã. S-au topit gheþarele în relaþia dintre fluxurile artei occidentale, underground-ul estic de altã datã constituie acum un bun material documentar sau de arhivã doar. Artistul estic a început sã circule, sã se informeze cu dezinvolturã ºi sã-ºi însuºeascã configuraþiile design-ului apusean: aerisit, atractiv, spectaculos, aseptic, ce tinde spre o perfecþiune de dincolo de uman. Problema majorã care se pune însã în aceastã deschidere ºi permisivitate este chiar artistul, natura lui umanã, problematica lui interioarã, dacã vreþi. În ce mãsurã oportunitatea care i se deschide acestuia de a se exprima prin alte mijloace plastice decât cele pe care i le-a oferit un sistem de învãþãmânt prin care a trecut îl re-modeleazã ca entitate creatoare? Cãci, sã ne înþelegem: un artist care a folosit peniþa, pensula sau dalta, ca unelte prin care îºi exterioriza ideile, opþiunile plastice, mai greu ar decide / consimþi sã se aºeze în faþa unui calculator sau ar folosi un câmp (la propriu) sau o periferie a unui mare oraº pentru a produce o performance sau o intervenþie. Trebuie sã fii un anume tip de artist pentru astfel de exteriorizãri. Tipul acesta de “exhibiþionism” þine de natura ascunsã a lucrurilor, de o altã ordine a socialului ºi mentalului chiar. Dar ºi de diferenþa culturalã – adevãrat mãr al discordiei. Pe Joseph Beuys l-a putut “secretá” doar o þarã ca Germania, aºa cum pe sculptorul Robert Smithson doar America l-a putut însufleþi, ceea ce nu s-ar putea spune despre Pollock; el este din altã “poveste”. Brener ºi Kulik sunt copiii-anarhiºti ai Rusiei rãmase fãrã incomensurabilul imperiu, iar Miroslaw Balka ºi Tadeusz Kantor reprezintã “sevele” creatoare ale Poloniei sumbre. Mark Verlan este un produs specific al histrionismului superficial, dar atât de “metisat” chiºinãuean; dar el n-a avut nevoie de banii (sau logistica ideologicã a) lui George Soros pentru a sonda în “ºantierele arheologice” ale acestei sensibilitãþi particulare. CSAC doar l-a fãcut cunoscut. Recunoaºterea, însã, este doar cireaºa de pe tort, este, poate, doar partea vãzutã a icebergului. Problemele creaþiei rãmân mereu ascunse, aproape insondabile pentru spectatorul de circumstanþã cum este, de obicei, cel ce viziteazã spaþiile în care se expune arta contemporanã. Exhibiþionismul artistului este de datã foarte recentã. El þine, pânã la urmã, de impulsuri exterioare, provocate de circumstanþe, conjunctural.

Din toate epocile pe care le contabilizãm spre a articula o istorie a artei, a noastrã (“postumanã”?; Post Human – acesta era titlul unei expoziþii realizate de Jeffrey Deitch, deloc întâmplãtor itineratã la Lausanne, Turin, Athena, Hamburg, încã în 1992) este poate cea mai nãbãdãioasã; chiar publicul ºi amatorul de artã, “maºini” raþionale inventate de modernitate ºi educate de curatori, filozofi ºi directori de muzee, par a nu mai conta prea mult pentru artistul de datã recentã – el lucreazã parcã numai ºi doar pentru sine. A nu se înþelege însã, în acest context, cã este vorba despre acelaºi “mit al artistului singur ºi neînþeles” (varianta binecunoscutã, romanticã), pentru cã acesta chiar îºi punea realmente problema comunicãrii – de o manierã foarte, sau aproape, bolnãvicioasã. Artistul contemporan se autoînsingureazã, comunicarea lui devine mai repede una pretinsã ºi mimatã decât voitã ºi trãitã în mod expres. El nu vrea sã aparã în faþa publicului (arta video funcþioneazã ca un paravan protector, conceptualismul dicteazã bariere verbale, non-comunicative), el se prezerveazã de orice atingeri cu potenþialul sãu public. Lumile create, de pildã de Moriko Mori, sunt universuri nelocuite ºi nelocuibile, sterile, virtuale, transparente, fluide. “Carnea” ºi “secreþiile” artistului sunt cu grijã izolate, pitite, fãcute sul ºi “filtrate” pânã la indistincþie. De la Manzoni, cu a sa “Merda d’artista” pânã la Wim Delvoye, cu instalaþia “Caca-Cola”, producãtoare de excremente umane. Orice tip de flexibilitate ºi îndoiala par a fi excluse – ca reprezentînd un pericol permanent, destructiv. Tipul acesta de comportament þine de alte relaþii sociale, þine de timpul supermarketului, de era mastodonþilor comerciali. Erã care dureazã atât cât eºti acolo, înãuntru, în acele hale, unde ai de toate, dar eºti singur, abandonat în ghearele mãrfurilor. De ce oare acolo cântã mereu muzica? Spaþiile întunecate în care se “planteazã” arta video sunt oarecum similare cu acele hangare…

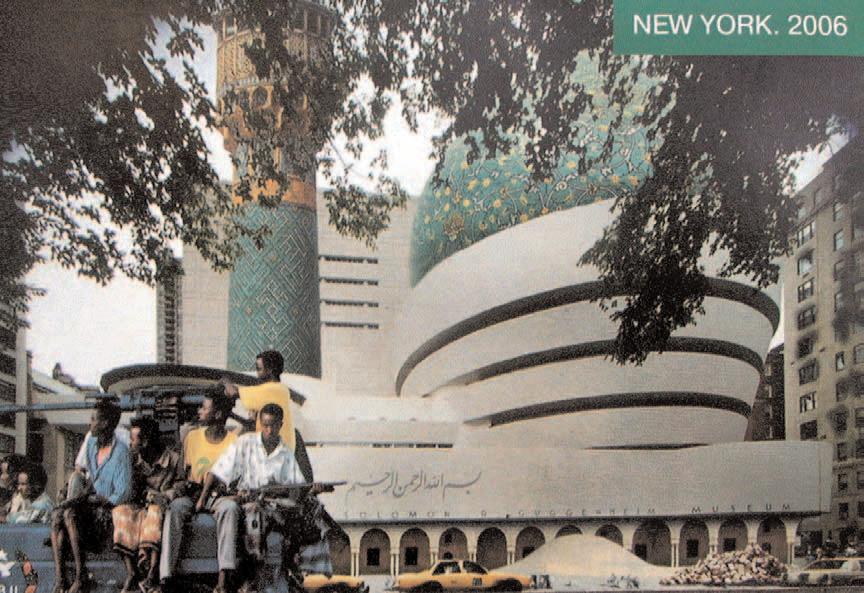

Arta ºi ea e o marfã, iar muzeele tind sã devinã hale de divertisment. Cafeneaua, shop-ul, videoteca completeazã miza vizitãrii unui muzeu; componentele acestea, cãrora le-am putea zice ºi “ingrediente” întregesc tipul de ofertã care se înfãþiºeazã spectatorului. Cartolinele, hãrþile, diapozitivele, ghidurile, cataloagele, ghidajele, ilustratele, ecusoanele – fac parte din expoziþie. Expunerea are o nevoie vitalã de aceste “cârje” ilustrativ-explicative. Subtil, vizitatorul trebuie cucerit, dãdãcit, educat, câºtigat de partea ta. El nu va fi lãsat sã plece cu nedumeriri sau angoase. Grija (maternã? a) instituþiei pentru spectator face parte din chiar releele sistemului artistic.

“Sistemul artei este un sistem al consumului demonstrativ, sistem care are, fireºte, multiple aspecte comune cu alte structuri ale societãþii de consum – turism, modã sau sport. Dar, fireºte, sistemul artei este incomparabil mai individualizat: dacã în alte sisteme consumul este în grup, în cel artistic, el este practic individual, original, personal. Sistemul artei propune spectatorului nu atât produsul, cât variante individuale ale metodelor de consum a acestui produs. Pe scurt: în sistemul artei se consumã însuºi consumul” (Boris Groys).

Ei bine, cultura tradiþionalã a þãrilor din Est are de înfruntat aceastã invazie a noului, cu toate formele pe care le aduce “imperialismul multinaþional”. Cum va arãta acest “hibrid” intelectual în anii imediat urmãtori?

Vladimir Bulat aprilie-iunie, 2002

6

Different Kinds of Invasion

The consumer society is, by its policy of imposing itself vigorously, an almost irreversible invasion. From the very start I would like to clarify the terms of the issue under discussion. My thesis is as follows: the “multinational imperialism” (Frederick Jemison), which now is expanding eastwards, “exports” to the areas under its control its cultural forms as well as the institutional discourses connected with them; they represent an effect of the “hegemony of capital” (Okwui Enwesor). I will try to describe a scheme and the chain of elements that define the idea of invasion in terms of contemporary art, which is one of the manifestations of this “imperialism.”

A military invasion, from the oldest times, aimed at occupying territories, crushing the enemy’s military force, and defeating (or mutilating) physically and morally the rulers of the coveted territory. When the symbolic power is defeated, the pillars on which it rests crumble instantly. Chaos is the close kin of Thanatos. Its vapors start hovering as soon as fear, horror and anxiety take over the battle field and the camp of those whose fate has been shame, humiliation, defense and defeat. Well, only some have been born to become victors. Or perhaps there are invisible powers that “arrange” things this way? Looking back, we see more vanquished than victors. More bodies than monuments. Ruins cover the entire world, poverty is the order of the day in most parts of the planet. More ruins are added to the already existing ones, which are increasingly heavier and more embarrassing. The world is full of contrasts and differences mold and dictate policies, discourses, and ideologies.

There are also cultural invasions, which work similarly to the scheme described above. Fukuyama argues that “democratic performance depends directly on a given culture”, referring to the post-totalitarian fate of the countries from the former communist world. The political values of Western democracy take root with much difficulty in Orthodox countries (Moldova, Romania, Bulgaria, Macedonia), as well as in Muslim ones (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan), which oftentimes face a fierce resistance from the traditional culture which is dominant, clearly defined, paternalistic, and often grudgingly residual. A certain type of “nationalism” bares its fangs at all levels; there is a tacit cohesion (and collusion) of conservative forces (of any nature: political, cultural, social, institutional) by which they oppose any forms of novelty. This is a struggle of big stakes.

In the case of Moldova, even the new technologies are grouped along ethnic lines; there are Internet providers who work only for Russians, who accept (with partiality) that there exists a “Moldovan” language (Moldova Cyber Community), while advertising on the Web (which so far has been extremely weak) is almost exclusively in Russian. The television that has the largest audience is the “national”, central one, which broadcasts only several hours per day under a horrible censorship and total control over what’s being broadcast. No independent, private television community able to counteract the almost total supremacy of the official one has appeared yet. There have been several attempts, but such efforts have been quickly helped on to bankruptcy. The case of Catalan TV is a famous one. The offer of the cable operators is blatantly limitative, when Russian channels represent a majority; this is largely regulated by demand – a situation perversely speculated by the ideologists of denationalization and current falsifiers of history. Moldova is in an extremely delicate situation from the viewpoint of human potential: several hundred thousand people have left abroad (legally, but mostly illegally) to work, to rob, to prostitute themselves. To be sure, there are positive examples as well. Many young people have received “Magna cum laude” diplomas at various foreign universities in Europe and America. Nevertheless, this country has a divided society, in which the militant civility is embarrassingly overshadowed by the basic struggle for survival. Normality here is the privilege only of a small clique of nouveaux riches

In one of the northern districts of Chiºinãu one can see the idyllic image of the Moldovan “paradise”, populated by several dozen villas and small “palaces” of this social category – they appeared overnight in the jungle of local “capitalism.” I believe such overly protected, dressed-up and pseudo-Americanized enclaves appeared in the entire Eastern Europe. Defying emanations of the glittery transoceanic Beverly Hills. What we see essentially is a “grafting” of the esthetics characteristic of the standardized American living space onto the trunk of a local model of normal life, as it used to be in the ex-USSR cities. Houses with a lot of space inside, with the ubiquitous living room and perhaps Jacuzzi too, while outside we see multiple turrets, balconies, skylights and zinc roofs (sometimes tile roofs) that appeared in large numbers almost overnight. The houses and villas in this area have pharaonic sizes, and each of them “speaks” its own architectural language. Practically one can’t find

7

two similar constructions. They are not alike. But all of them are surrounded by fences, well-guarded, with metal gates, rich ironwork, sophisticated surveillance systems, while their walls function as true fortresses. It is interesting that several embassies are located here too, as well as several families of diplomats and business people. As they say, the local “aristocracy” have honorable, “good” neighbors. It is difficult to say whose idea it was to populate / deforest this area: the foreigners’ or the locals’. In any event, both groups behave as if they belonged to the same social category: the new caste of the “globalized.” The characteristic signs are quite visible. Now they all live together, in a “secure community”, in an enclave in which they can feel (or at least they think so) protected, guarded, hidden from the impure eyes of the “proletariat”, the undesired, the wretched and the poor. This is a possible image of the “voluntary ghetto” described recently by Zygmunt Bauman, that is the place that offers a full “warm sense” of security: “The security and certainty of existential conditions can be hardly bought by a bank account – but the security of the place can be bought only if the bank account is large enough.” The bank accounts of the “globals” are usually sufficiently large. The globals can afford, in the industry of security, the equivalent of haute couture

Contemporary art – this is not the place for a definition of this garrulous and confusing concept – from its very debut has seemed to many as an “invasion”, as a public self-assurance, as an ostentatious discharge of the ballast of tradition. “The negativity of avant-garde” (Thierry de Duve) corrodes the foundation of “positive” culture without denying it because, in order to exist, it needs contrasts, tension, states of conflict. It is the lack of consensus regarding contemporary art that makes it possible, identifiable, analyzable. Tradition as landmark, as reference element, as starting point.

So, contemporary art or, as it is mistakenly called, avant-garde art is in a relationship of tension with the tradition that it found on the ground to which it was “imported” or “planted.” Tradition has strong, well-kept roots. It was created by the effort of generations of individuals for whom the existential “dough” was what they themselves called (and still call) “tradition.” It is that infallible and indestructible something, for which art is just one of the supports. Perhaps not even the most important one. “The national school of painting” or “the Moldovan school of tapestry” are just ideological-theoretical constructions (not at all persuasive ones) built on a carrier of peasant sensibility; they represent practically the first instance when the heritage of the past is looked upon more or less scientifically. I think it important that these things were first mentioned by the first generation of post-WWII Moldovan intellectuals, who were educated in the Soviet cosmopolitan, impersonal, unicephalous, heterogeneous, depersonalizing culture. They had almost no contact with the historical past or, at least, such contact was strongly watered down and mediated. A very complicated issue emerges here: to what extent some individuals schooled in an “internationalist” culture (as the socialist culture used to be called), with no direct link to the interwar school, are able to carry and pass on to other generations the “genes” of the local “ancestral” tradition?

It is difficult to say where exactly contemporary art was born, since it is almost impossible to pinpoint the culture whose product it is. Its parents were emigrants, rootless people by definition (Duchamp, Tzara, Joyce, Kandinsky, Jarry, Brancusi). It is taken for granted, and the judging criteria formulated by the modern world seem inappropriate for an analysis of this kind of artistic option. I believe there is a structural link between the “invasion” of political forms and social cohabitation wanted / assumed by a part of Europe – the one on this side of the former Iron Curtain – and the somewhat forced, programmed cultivation of contemporary art here. In other words, the phenomenon is an implant accepted with difficulty by the alien cultural body. The cohabitation is tense. It is seen as an alien, illusory, bastard, ephemeral body, as an eternal last-come.

Contemporary art, in its “Moldovan” version, has not become a liked phenomenon to the present day and is not looked upon as an equal. It is seen as a “rich relative” who sometimes behaves nasty, at will –“because it’s got the means”! The entire network of Soros Centers for Contemporary Art had for a long time a privileged status in all the countries where it had its “tentacles;” it impressed by unlimited financial possibilities, any project was carried out, any curatorial prank was possible. People used to come at the beginning to see the “potty things” of those “Soros people.” In some countries this injection of capital into projects of contemporary art had beneficial effects in terms of modeling a new type of artistic consciousness. The ice melted between the different currents of Western art, and the erstwhile Eastern underground became good documentary or just archive material. The Eastern artist started to travel, to learn easily and assume the configurations of Western design: clear, attractive, spectacular, aseptic, tending towards a perfection beyond the human. The main problem that appeared in this openness and permissiveness was the artist himself, his human nature, his inner problematic if you will. To what extent does the new opportunity to express himself by other artistic means than the ones taught to him by the educational system he went through remodels the artist as a creative entity? Let’s clarify one thing: an artist who used the quill, the brush or the chisel as tools through which he expressed his ideas and artistic options, will have difficulties sitting in front of a computer or using a field (in the direct sense of the word) or the periphery of a large city to produce a performance or an intervention. One has to be a certain kind of artist for such expression. This type of “exhibitionism” is linked to the hidden nature of things, to a different order of society and even mentality. But also to a cultural difference – a true apple of discord. Joseph Beuys could be “secreted” only by such a country as Germany, just as a sculptor such as Robert Smithson could be given life only by America, which could not be said about Pollock; he is from a different “story.” Brener and Kulik are the anarchist children of a Russia left without the boundless empire, while Miroslaw Balka and Tadeusz Kantor represent the creative “pith” of a somber Poland. Mark Verlan is a specific product of superficial histrionism, but also so characteristic of the crossbreeds of Chiºinãu; he didn’t need the money (or the ideological logistics) of George Soros in order to dig at the “archeological site” of this peculiar sensibility. CSAC only made him known. Recognition, however, is only the cherry on top of the cake, or perhaps only the visible part of the iceberg. The problems of creativity are always hidden, almost unprobable for ccasional viewers as are those who usually visit exhibitions of contemporary art. Artistic exhibitionism is a quite recent phenomenon. It is tied, at the end of the day, to external impulses provoked by given circumstances.

Of all the eras usually listed to give body to a history of art, ours (“posthuman”?; Post Human – this was the title of an exhibition by Jeffrey Deitch, which traveled, by no accident, to Lausanne, Turin, Athens, Hamburg, back in 1992) is perhaps the most capricious; even the public and lovers of arts, rational “machines” invented by modernity and educated by curators, philosophers, and museum directors, seem not to count too much for the new artist – he seems to work only and exclusively for himself. One should not understand, however, this in the sense of “the myth of the lonely and misunderstood artist” (the well-known, romantic version), for this artist actually raised the issue of communication in a very, or perhaps almost sickly manner. The contemporary artist alienates himself, his communication is pretended and mimicked rather than willed and lived expressly. He does not want to face the public (video art works as a protective screen, conceptualism dictates verbal,

8

non-communicational barriers), he keeps away from any touch with a potential public. Created worlds, for instance those of Moriko Mori, are uninhabited and uninhabitable universes, sterile, virtual, transparent, fluid. The artist’s “flesh” and “secretions” are carefully isolated, hidden, rolled up and filtered to indistinction. From Manzoni and his “Merda d’artista” to Wim Delvoye and his “Coca-Cola” installation, which produced human excrement. Any kind of flexibility and doubt seem to be excluded as a permanent, destructive threat. This kind of behavior is linked to other social relations, to the time of the supermarket, to the era of commercial mastodons. An era that lasts for as long as you are there, inside, in those halls, where you have everything but feel alone, abandoned to the claws of merchandise. Why does music always play there? The dark spaces in which video art is “planted” are somewhat similar to those hangars...

Art is merchandise too, and museums tend to become entertainment halls. The café, the shop, the video parlor complement the bet of a museum visit; these components, which we may also call “ingredients”, complete the offer before the viewer. Cards, maps, slides, guides, catalogues, pointers, illustrations, badges – they are all part of the exhibition. The exhibition needs vitally these illustrative-explicative “walking sticks.” Subtly, the visitor must be conquered, doted, educated, won over to your side. He will not be permitted to leave puzzled or anxious. The (maternal?) concern of the institution for the viewer is part of the very relays of the art system.

“The art system is a system of ostentatious consumption, a system that has, naturally, many common aspects with other structures of the consumer society – tourism, fashion, or sports. But, naturally, the art system is incomparably more individualized: while in other systems consumption is performed in groups, in the artistic one it is practically individual, original, personal. The art system offers to viewers not so much the product, as individual versions of consumption methods of this product. In short: in the art system consumption itself is being consumed.” (Boris Groys)

Well, the traditional culture of Eastern countries has to face this invasion of the new, with all the forms brought along by the “multinational imperialism.” What will this intellectual “hybrid” look like in the near future?

Vladimir Bulat April-June, 2002

Vladimir Bulat April-June, 2002

9

Invazia invaziilor

ªtefan Rusu, artist, curator al proiectului “Invasia”

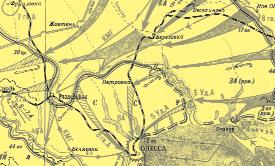

Moldova se întinde în lãþime de la 44’ 54’’ pânã la 48’si 51’’. Lungimea ei este nedeterminatã, dar cei mai mulþi geografi aºeazã marginea ei apuseanã, care atinge Transilvania, la 45’39’’: capãtul ei dinspre rãsãrit, care face un unghi ascuþit la Akerman, numit de locuitori Cetatea Alba, îl socotesc la 53’ 22’’. D. Cantemir. Descrierea Moldovei. Chiºinãu,1992

Huseyin Bahri Alptekin

Proiectul Utopic Invasia

“Sea Elephant Travel Agency” (Istambul – Salonic – Orheiul Vechi / Moldova – Tirana -Istambul)

Post Scriptum pentru Invasia:

Kagan (ca ºi Han, un nume vechi din Asia Centralã) m-a sunat, spunând cã se þine un chef la Salonic pe 13 (septembrie 2001) ºi cã se va duce cu Cessna 340 a lui Korhan, ºi a mai spus cã putem sã ajungem ºi la Bienala de la Tirana pe 14-15, la deschidere, dupã cheful de la Salonic; tot atunci ieºea numãrul 4 al artist-ului (revistã de artã contemporanã din Istambul) ºi anunþurile fuseserã deja fãcute.

Mai ºtiam cã pe 16 în Moldova se þinea proiectul Invasia. Când ne-am hotãrât ce facem, ne-am zis, de ce sã nu mergem ºi în Moldova dupã deschiderea de la Tirana. Chiar dacã aveam probleme reciproce cu vizele între Turcia ºi Moldova, ne-am spus, sã încercãm sã obþinem viza în ultimul moment, iar dacã nu merge zburãm oricum ºi invadãm din cer ca un OZN.

Proiectul Invasia era ca o carte-blanche pentru noi ºi vroiam sã ajungem acolo oricum. Echipa avionului nostru TC-ART (Tango Charlie-Alpha Romeo Tango) se compunea din Korhan Abay, artist pilot, Kagan Gursel, artist de viaþã, Ahmet Senkart, designer, artist bucãtar, ºi eu. Cu Ahmet ºi Kagan fusesem la Odesa ºi Soci, cãutându-l pe Marea Neagrã pe eroul lui Jules Verne Keraban, în 1999 ºi 2000. Noi întotdeauna ne dorisem sã ajungem în Moldova. Aceasta era o sarcinã pe care ne-o pusesem încã în 1999. Totul era pregãtit, ºi eu eram gata sã termin o lucrare pentru o expoziþie, apoi sã mã întâlnesc cu Kagan, care pe atunci stãtea la Swiss Hotel, deci l-am sunat sã ne întâlnim, l-am gãsit, în mod straniu, la hotel, el m-a întrebat dacã ºtiam, nu, eram ocupat cu lucrul la capãtul lumii în afara oraºului. M-am dus la hotel sã vãd dezastrul: 11 septembrie. Vã puteþi închipui deci cum acel dezastru global a afectat chiar ºi lumea artei. O datã în viaþã aveam ºi noi la dispoziþie un avion de dragul artei ºi nu exista nici o posibilitate sã decolãm. Traficul aerian fusese închis deasupra Mãrii Egee, pentru încã cel puþin câteva zile în cazul avioanelor mici, particulare. În plus, nici nu poþi explica situaþia dacã eºti întrebat – patru turci merg cu avionul la Salonic la un chef apoi la Bienala de la Tirana ºi în Moldova la proiectul Invasia ºi retur la Bienala de la Istambul sã contribuie la aspectul conceptual: Ego Fugal. Cãile aeriene erau deci închise, iar noi nu ne puteam urma acel itinerar artistic. Dezastrul acela global ne-a afectat micile noastre vieþi de artiºti. Ce micã e lumea.

Huseyin Alptekin, 24 / 07 / 2002

Utopic Invasia project

“Sea Elephant Travel Agency” (Istanbul – Thessaloniki – Orheiul Vechi / Moldova - Tirana - Istanbul)

Post Scriptum for Invasia:

Kagan (like Khan, an old name from Central Asia) called me, saying that there was a party in Thessaloniki on the 13th (September 2001) and he would go there with Korhan’s Cessna 340, and he said we can make it to the Tirana Biennale as well on the 14-15 for the opening after the party in Thessaloniki; also the 4th issue of artist (contemporary art magazine in Istanbul) was about to be printed and they had put up the announcement already.

We also knew that the Invasia project in Moldova was going to be held on the 16th. When all was decided we said why not head to Moldova as well after the opening in Tirana. Even if we had reciprocal visa problems between Turkey and Moldova, we said, let’s try to get the visa at the last moment, or if that doesn’t work we just fly anyway and do the sky invasion as an UFO.

The Invasia project was a carte-blanche for us and we wanted to attempt it anyhow. The crew of our TC-ART (Tango Charlie-Alpha Romeo Tango) plane was Korhan Abay, pilot artist, Kagan Gursel, life artist, Ahmet Senkart, designer, artist cook, and me. With Kagan and Ahmet we had been to Odessa and Sochi, tracing the hero, Keraban of Jules Verne on the Black Sea, 1999 and 2000. We had always been attracted to go to Moldova. That had been our challenge since 1999. All was set and I was about to finish a piece for a show, I was going to meet Kagan, he was that time based in Swiss Hotel, I called him to meet, he was strangely in the hotel, he asked if I knew the thing, no, I was busy with work in the middle of nowhere out of the city. So I went to the hotel and watched the disaster: 11th September. You can then imagine how that global disaster affected even the art world. Once in life we had a plane for art’s sake and there was no way we could take off. The air traffic was closed in the Aegean sky, and at least for several more days for small, private planes. Besides, you can’t explain the situation if asked – four Turks are just flying for a party to Thessaloniki and Tirana Biennale and Moldova for the Invasia project and back for the Istanbul Biennale to contribute to the conceptual aspect: Ego Fugal. So the air was closed, we couldn’t do that artistic itinerary. That global disaster affected our small lives of artists. What a small world.

Huseyin

10

Alptekin, 24 / 07 / 2002

The Invasion of Invasions

Stefan Rusu, artist, curator of the “Invasia” project

Moldova stretches wide from 44’54” to 48’51”. Its length is indefinite, but most geographers have set its western edge, which touches on Transylvania, at 45’39”, and its eastern edge, which creates an acute angle at Akerman, named by locals Cetatea Alba (White Fortress), at53’22”.

D. Cantemir. Descrierea Moldovei. Chisinau,1992 (written in 1718)

11 P o s S c p P c u e S e a E e p h a n t 2 e p s

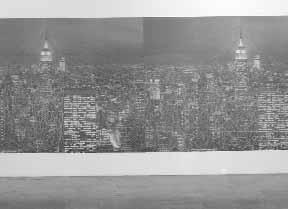

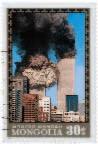

Mongolia a emis timbre poºtale cu imaginea zgârie-norilor din New York [03.11.2001 18:20]

La oficiile poºtale din Mongolia au apãrut spre vânzare timbre noi cu imaginea celor douã clãdiri de 110 etaje fiecare ale World Trade Center din New York, distruse în urma actelor teroriste din 11 septembrie.

Dupã cum a informat conducerea societãþii mongole Mongol ªuudan (Poºta Mongoliei) agenþia RIA Novosti, în urma actelor teroriste din SUA în întreaga lume a crescut brusc cererea pentru timbre, cãrþi poºtale ºi afiºe cu imaginea acestor clãdiri. ªi societatea Mongol ªuudan a hotãrât sã emitã un tiraj de timbre reprezentând WTC. Pentru filateliºtii din strãinãtate noile miniaturi poºtale, emise cu un tiraj de 30 mii exemplare, vor fi vândute prin Internet.

Societatea Mongol ªuudan intenþioneazã sã transmitã mijloacele acumulate în urma vânzãrii noilor timbre poºtale autoritãþilor oraºului New York pentru lichidarea consecinþelor actelor teroriste. (RIA Novosti)

Mongolia issued stamps depicting the New York skyscrapers [03.11.2001 18:20]

The post offices in Mongolia started selling new stamps depicting the two 110-story buildings of the World Trade Center in New York, destroyed as a result of the terrorist acts of September 11.

The management of the Mongolian company Mongol Shuudan (Mongolian Post) told RIA Novosti that after the terrorist acts in the USA there was a sharp increase in demand all over the world for stamps, postcards and posters with the image of those buildings. The Mongol Shuudan company also decided to print stamps with WTC. For foreign philatelists the new post miniatures, printed in 30 thousand copied, will be sold also through the Internet. The Mongol Shuudan company plans to donate the revenues collected from the sale of the post stamps to the New York authorities as a contribution towards eliminating the consequences of the terrorist acts. (RIA Novosti)

12

13

Formarea statului Moldova a fost un rezultat al procesului îndelungat de dezvoltare istoricã a populaþiei romanice de est, mersul lent al cãruia se datoreazã, în mare mãsurã, dupã cum afirmã istoricii, situaþiei geografice a þãrii: la capãtul “coridorului” stepei euro-asiatice – calea miºcãrii permanente a nomazilor din Orient.

Istoria Moldovei. Publicaþia Academiei de ªtiinþe a Republicii Moldova, Institutul de Istorie, 1992

Invasia hunilor, de la sfârºitul sec. IV e.n. a avut cele mai nefaste urmãri pentru populaþia din spaþiul dintre Nistru ºi Carpaþi. Ajungând la Nistru în anul 376, hunii au forþat râul, i-au înfrânt pe ostrogoþi, o parte din care, în frunte cu Athanaric, s-au retras spre Carpaþi. Puternica uniune tribalã a hunilor s-a constituit încã în sec. III î.e.n., în stepele Asiei Centrale

Istoria Republicii Moldova. Publicaþia Asociaþiei oamenilor de ºtiinþã din Moldova “N. Spãtarul Milescu”, Chiºinãu, 1997

Nenad Andric

Text fãrã titlu (privind proiectul Life Still)

Lucrarea cu calul alb a fost conceputã prima datã pentru evenimentul din Moldova din septembrie 2001. Îmi amintesc, cã fusesem invitat sã vin la acea întrunire “ciudatã” cu doar o zi înainte de începutul evenimentului.

Deci nu am avut prea mult timp sã mã gândesc.

Vroiam sã vãd acel tableau vivant / performance acolo, pe un deal, cu sunete ambiante ºi sunete de difuzoare, ºi cu ceva vânt. Însã din cauza unui(or) motiv(e) lucrarea nu a fost realizatã. Cal aveam, aveam ºi aproape tot echipamentul necesar, ºi oamenii, stimaþii noºtri spectatori, erau ºi ei prezenþi. Însã lipsea totuºi ceva sau cineva.

Oricum, lucrarea a fost dusã la capãt la sfârºitul aceluiaºi an, în noiembrie, la k / haus, dasKunstlerhaus Passagegalerie de la Viena.

Nu a fost uºor sã realizez aºa o lucrare acolo, deoarece primãria de la Viena are niºte regulamente destul de stricte privind evenimentele publice, mai ales cele “mai marginale” ºi nu prea obiºnuite. Au fost solicitate exact trei permisiuni diferite: prima a fost de la veterinar, care a examinat Calul ºi incinta galeriei. A doua a fost de la aºa-numita “TheaterPolizei”, ºi încã una de la autoritãþile oraºului.

Ideea era de a prezenta un corp “digitalizat” al unui cal alb viu, care sã stea nemiºcat în spaþiul galeriei. Utilizând simplul mijloc de proiectare a unei benzi video curate pe corpul Calului, se atingea iluzia unui “corp video”, creându-se o uºoarã confuzie însoþitã de un anumit suspans: corpul real se transforma într-o sculpturã video tridimensionalã.

Iar suspansul, acesta apãrea probabil deoarece Calul intrase în galerie printr-o deschizãturã în peretele lung de sticlã. Camera era destul de îngustã, ºi nici nu prea înaltã – urechile Calului aproape atingeau tavanul.

Poate ar trebui sã menþionez cã graþiosul animal a trebuit sã vinã prin staþia de metrou de la Karlsplatz, aceasta fiind singura cale pe care se putea evita aventura prea riscantã de a duce calul în jos pe scãrile ce duc spre galerie.

Publicul era destul de tãcut, sau poate precaut, deoarece deranjarea marelui actor alb putea sã ducã la... o situaþie neaºteptatã. O vienezã încântãtoare întreþinea buna purtare a Calului, stând discret lângã el în întuneric.

Aceastã lucrare nu are o “citire” sau “înþeles” ascuns, cu toate cã sugereazã totuºi ceva. Lucrarea a fost realizatã când mã mai interesau piesele legate de un loc concret. Acum probabil nu aº mai lua în considerare circumstanþele istorice sau geopolitice date ale locului concret.

Ideea unei lucrãri în plutire, autodefinitorii (self-specific, un termen pe care l-am inventat cu aceastã ocazie) mi se pare mai interesantã, cel puþin pentru un timp.

Nenad Andric, iulie 2002

Aº vrea sã le mulþumesc ºi urmãtoarelor persoane care au contribuit la lucrarea mea în diferite feluri: Andrej Vucenovic, Zagreb; Elke Krasny, Viena; Gerhard Leixl, Viena; Marin Turea, Chiºinãu; Octavian Eºanu, Chiºinãu; Paul Beekhuis, Eindhoven; Tina Bepperling, Viena; Thomas J. Jelinek, Viena; Veaceslav Druþã, Chiºinãu; Valie Goschl, Viena; ºi chiar lui ªtefan Rusu, Chiºinãu.

Untitled Statement (on the Life Still project)

The piece with a white horse was originally conceived for the September 2001 event in Moldova. I remember that I was invited to come to that “odd” gathering only one day before the thing started. So I did not have much time to think.

I wanted that tableau vivant / performance to be there, up on a hill, with sounds from the environment and sounds from the loudspeakers, with some wind as well. But for some reason(s) the work was not realized. The horse was there, almost all of the equipment was there, and the people, our respected spectators, were there too. But something or somebody was still missing.

Anyway, the work was finally completed later that year, in November, in Vienna’s k / haus, dasKunstlerhaus Passagegalerie.

It was not very easy to perform such a piece there, since the city of Vienna has some rather strict regulations regarding public events, particularly those “edgy,” not so very usual ones.

Precisely three different permissions were requested: first one was from the vet, who examined the Horse and the gallery venue. The second one was from the so-called “TheaterPolizei,” and then yet another one from the city authorities.

The idea was to present a “digitized” body of a real white horse standing still in the gallery space. By using the simple means of a blank video tape projected on the Horse’s body, the illusion of “video-body” was achieved, and a small confusion accompanied by a certain suspense was created: the real body became a threedimensional video sculpture.

And the suspense, it was probably because the Horse entered the gallery through the opening in the long glass wall. The room was rather narrow, and also not very high – the ears of the Horse were almost touching the ceiling.

Perhaps it should be mentioned that the gracious animal had to come via the metro station on Karlsplatz, as it was the only way to avoid the overly risky affair of the Horse walking down the stairs leading to the gallery.

The audience was rather quiet, cautious I guess, as the disturbance of the great white actor might have led to an... unexpected situation. A charming Viennese girl was maintaining the Horse’s good behavior, discretely standing next to him in the dark. There is no implied “reading” or “meaning” of this piece, although it does suggest something.

It was made in the time while I was still interested in site-specific works. Now I would probably not take into account the given historical, or geo-political circumstances of the place.

The idea of a floating, “self-specific” (a new term I coined for this occasion) work appears more appealing, at least for the time being.

Nenad

Andric, July 2002

I would also like to thank the following persons for contributing to the work in various ways: Andrej Vucenovic, Zagreb; Elke Krasny, Vienna; Gerhard Leixl, Vienna; Marin Turea, Chisinau; Octavian Esanu, Chisinau; Paul Beekhuis, Eindhoven; Tina Bepperling, Vienna; Thomas J. Jelinek, Vienna; Veaceslav Druta, Chisinau; Valie Goschl, Vienna; and even Stefan Rusu, Chisinau.

14

The formation of the Moldovan state was the result of a long process of historic development of the eastern Roman population, whose slow progress was due, as historians have shown, mainly to the country’s geographic situation: at the end of the “corridor” of the Euro-Asian steppe – the route of incessant movement of nomads from the east.

Istoria Moldovei. Publication of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Moldova, Institute of History, 1992

The invasion of the Huns at the end of the 4th century A.D., had the most nefarious consequences for the population living between the Nistru river and the Carpathians. The Huns reached and crossed Nistru in 376, defeated the Ostrogoths, a part of whom, led by

Athanaric, retreated towards the Carpathians. The Huns’ strong tribal union had been created back in the 3rd century B.C. in the steppes of Central Asia.

Istoria Republicii Moldova. Publication of the Association of Scholars of Moldova “N. Spatarul Milescu”, Chisinau, 1997

During Attila’s time (445-454), the Hunic “empire” reached the peak of its development, including in its realm a vast territory in central and south-eastern Europe populated by Thracians, Germans, Alans and many other tribes. The devastating invasion by Huns in the second half of the 4th century A.D. lead to an almost complete destruction of the population from the Carpathian-Nistrian area.

15

Pe timpul lui Attila (445-454) ”imperiul” hunic atinge culmea dezvoltãrii sale, incluzând în componenþa sa ºi un vast teritoriu din Europa centralã ºi de sud-est, populat de traci, germani, alani ºi multe alte triburi. Invazia pustietoare a hunilor din a doua jumãtate a sec. IV e.n. a dus ºi la nimicirea aproape completã a populaþiei din spaþiul carpato-nistrean. Doar spre sfârºitul sec. VI în aceste teritorii încep sã pãtrundã triburile slave.

Istoria Republicii Moldova. Publicaþia Asociaþiei oamenilor de ºtiinþã din Moldova “N. Spãtarul Milescu”, Chiºinãu, 1997

Procesul de dezvoltare a societãþii nord-dunãrene este grav afectat la sfârºitul sec. IV de invazia hunilor. Aceste triburi de pãstori nomazi au nãvãlit în fosta Dacie, silindu-i pe goþi (triburi vizigote) sã se retragã spre sud, pe teritoriul Imperiului Roman.

Strãbãtând pãmânturile populate de daco-romani, hunii s-au stabilit în Panonia, de unde întreprindeau campanii de jaf pe teritoriile vecine, inclusiv Dacia. Dar dupã înfrângerea lor de cãtre romani în lupta de la Nedav ºi moartea cãpeteniei lor Attila în 454, acest conglomerat de popoare se destramã.

Confruntarea hunilor cu Imperiul Roman, luptele interne din confederaþia tribalã a lui Attila ºi campaniile de jaf au determinat populaþia autohtonã sã se strãmute în locuri mai adãpostite, mai depãrtate de cãile de comunicare ale invadatorilor.

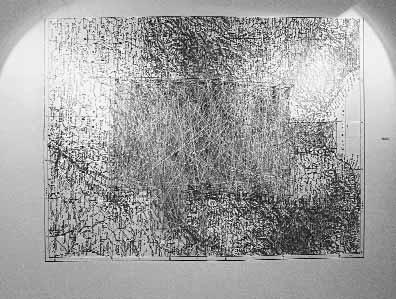

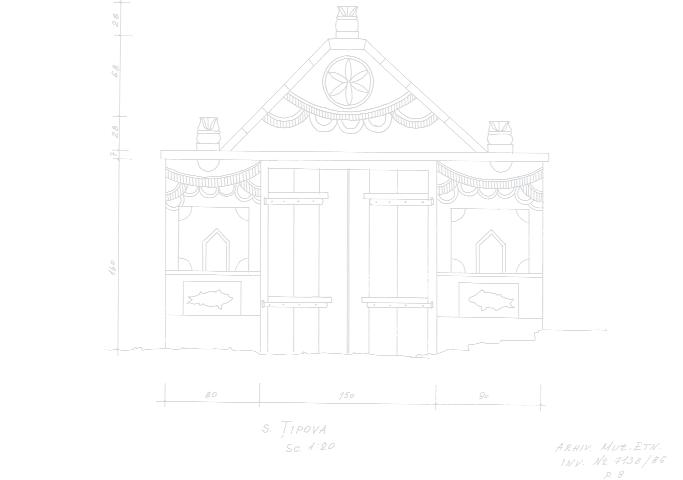

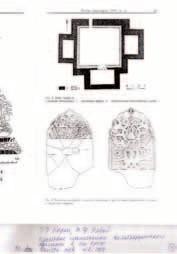

Antik Alexandru

Macheta pomenirilor

Genul: machetã / instalaþie

Tehnica: mixtã (fotografie, carton, sfoarã, lemn, piatrã)

Dimensiunea:100x100cm

2001 Invasia, Tabãra Internaþionalã de Artã, Orheiul Vechi, ºi Simpozion Internaþional, Chiºinãu, Moldova

Expunere

O machetã este întotdeauna o construcþie în miniaturã, oarecum mai schematicã ºi anterioarã configuraþiei reale. Macheta unui obiect sau a unui mediu închipuit este un lucru mai obiºnuit. Mai neobiºnuitã este macheta unei acþiuni artistice, sau macheta unui demers artistic, ºi asta când macheta-schiþã nu se dovedeºte a fi un simplu prospect pentru redimensionarea construcþiei în miniaturã.

În câteva din ultimele mele lucrãri, cum ar fi ºi Macheta pomenirilor, am folosit acest tip de construcþie în miniaturã ca o schiþã tridimensionalã, dar ºi ca o diagramã a timpului ipotetic, substituind motivele declanºatoare ale inspiraþiei cu motivele configurãrii sub presiunea contextului prezent dat.

Requiem Mock-Up

Genre: mock-up / installation

Technique: mixed media (photo, cardboard, string, wood, gravel)

Dimension: 100x100 cm

2001-Invasia, International Art Camp, Orheiul Vechi; and Symposium, Chisinau, MD

Statement

A mock-up is always a miniature construction, which is in a way schematic and downgraded from the real configuration. The mock-up of an object or of an imagined environmental milieu is more usual. Less usual is the mock-up of an artistic action, or the mock-up of an artistic discourse, when the schematic mock-up turns out not to be a simple prospectus of a miniature downscaled construction.

In several of my latest pieces, and in the Requiem Mock-Up too, I used this type of miniature construction as a three-dimensional design but also as a diagram of hypothetical time, substituting for the triggering motives of inspiration the motives of configuring under the pressure of a given present context.

16

It was only towards the end of the 6th century that Slavic tribes started coming to this territory.

Istoria Republicii Moldova. Publication of the Association of Scholars of Moldova “N. Spatarul Milescu”, Chisinau, 1997

At the end of the 4th century the process of development of the north-Danubian society was seriously affected by the invasion of the Huns. These tribes of nomad shepherds invaded former Dacia and forced the Goths (Visigothic tribes) to retreat southwards to the territory of the Roman Empire.

Crossing the lands populated by Dacian-Romans, the Huns settled in Pannonia, whence they undertook pillaging campaigns against neighboring territories, including Dacia. But after they were defeated by the Romans at the battle of Nedav, and after the death of their leader Attila, this conglomeration of peoples fell apart in 454.

17

Istoria Moldovei. Publicaþia Academiei de ªtiinþe a Republicii Moldova, Institutul de Istorie, 1992

O nouã situaþie politicã se creeazã pe pãmânturile carpato-dunãrene în urma evenimentelor ce au avut loc între 558-568, când conglomeratul asiatic al avarilor, împreunã cu germanii-longobarzii îi înfrâng pe gepizi. Avarii invadeazã teritoriul Platoului Intercarpatic ºi creeazã o imensã uniune de triburi numitã Hanatul Avar. Situându-se în câmpiile Dunãrii de Mijloc ºi al Tisei, ei îºi exercitau dominaþia pe celelalte teritorii carpato-dunãrene prin intermediul altor popoare dependente (gepizi).

Istoria Moldovei. Publicaþia Academiei de ªtiinþe a Republicii Moldova, Institutul de Istorie, 1992

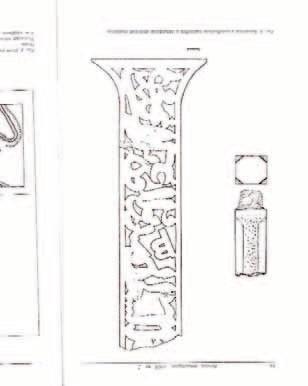

Iurie Cibotaru

“Vama”

TAMGA (tavro)

Tamga (din mongolã), folosit la origine de mongoli ca semn (tavro, marcaj), cu care se marcau posesiunile cu turmele de animale. Mai târziu – sigiliu pe acte oficiale, documente sau acte cu semnãtura hanului. Termenul “T.” a fost rãspândit pe aria þãrilor care au fost afectate de invazia mongolã din sec. XIII. În Asia Mijlocie, în þãrile din Caucaz, in Orientul Apropiat si cel Îndepãrtat “T.” este denumirea impozitului în bani introdus de mongoli ºi perceput de la negustori, meºteºugari, diverºi producãtori. În aceastã formã a existat pânã în anii 70 ai sec. XVI (în Iran a fost abrogat în anul 565). În limba mongolã contemporanã “T.” înseamnã sigiliu, ºtampilã, as în jocurile de cãrþi.

În Rusia termenul “Tavro” a fost folosit in sec. XIII-XV referitor la impozitele asupra schimburilor comerciale. Micii comercianþi din oraºe fie nu plãteau de loc “T.”, ori achitau acest impozit într-o cantitate minimã comparativ cu cei din afarã. Începând cu mijlocul sec. XVI, în legãturã cu trecerea unor impozite în registrul perceput de pe costurile mãrfurilor (într-un fel raportate la valutã – rubla), a apãrut un nou impozit denumit “rubliovaia poºlina” (impozit în ruble)

Soveþkaia

“Customs”

TAMGA (tavro)

Tamga (in Mongolian), was originally used by Mongolians as a marking sign (tavro, marker), which was used to mark the herds. Later it denominated the seal on official acts, documents or papers containing the khan’s signature. The term T was used in the countries affected by the Mongolian invasion of the 13th century. In Central Asia, the Caucasus, in the Far and Near East T denominated the monetary tax introduced by the Mongolians and levied on tradesmen, craftsmen and various manufacturers. It existed in this form until the 70s of the 16th century (in Iran it was abolished in 565). In contemporary Mongolian language T means seal, stamp, and also ace in card games.

In Russia the term “Tavro” was used in the 13th-14th c.c. to refer to taxes on commercial exchanges. The small urban merchants either did not pay T at all or paid a modicum amount as compared to merchants from outside the city. Beginning in the mid-16th c., in connection with the transfer of some taxes into the register based on the cost of merchandise (tied in a way to currency – the ruble) a new tax appeared, which was named “rubliovaia poshlina” (ruble tax).

Enþiklopedia / Tamga (tavro)

Enþiklopedia / Tamga (tavro)

18

Sovetskaia Entsiklopedia / Tamga (tavro)

The confrontation of the Huns with the Roman Empire, internal strife in Attila’s tribal confederation, and the pillaging campaigns forced the local population to move to more sheltered places, farther away from the invaders’ communication routes.

Istoria Moldovei. Publication of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Moldova, Institute of History, 1992

A new political situation was established on the Carpatho-Danubian lands in the wake of the events that took place between 558 and 568, when the Asian conglomerate of the Avars, together with the Longobard Germans defeated the Gepids. The Avars invaded the Intercarpathian plateau to create an immense union of tribes named the Avar Khanate.

Settling on the Middle Danube’s and Tisa’s plains, they exercised their influence over a number of Carpathian-Danubian territories through other dependent peoples (the Gepids).

Istoria Moldovei. Publication of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Moldova, Institute of History, 1992

Towards the end of the 7th century, from the east, from the Azov Sea basin and towards the lower Danube a movement of proto-Bulgarian Turanic hordes started; they were led by Asparuh. After they invaded the sub-Carpathian territories, the hordes crossed the

19

Spre sfârºitul sec. al VII-lea dinspre rãsãrit, din bazinul Mãrii Azov spre cursul inferior al Dunãrii, se îndreaptã ºi hoardele turanice proto-bulgare, conduse de Asparuh. Invadând teritoriile subcarpatice, hoardele trec peste Dunãre ºi pun temelia unui stat nou – Primul Þarat Bulgar, care în anul 864-865 a adoptã creºtinismul.

Istoria Moldovei. Publicaþia Academiei de ªtiinþe a Republicii Moldova, Institutul de Istorie, 1992

În cronica veche rusã Povesti vremennîh let (înc. sec. al XII-lea) ”volohii” sunt menþionaþi prin anul 898 în legãturã cu invazia triburilor ungare dinspre est, prin partea de nord a litoralului Mãrii Negre spre ºesul Dunãrii de Mijloc. Istoria Moldovei. Publicaþia Academiei de ªtiinþe a Republicii Moldova, Institutul de Istorie, 1992

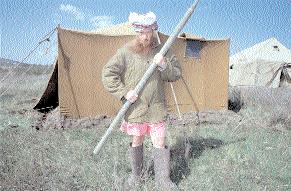

Vsevolod Demidov “Pomul vieþii”

Eu sunt rus de origine, însã pentru mine acest lucru înseamnã puþin. Eu locuiesc pe pãmântul Kazahstanului. Mã simt foarte comod aici. Ei bine, nu mã pot trece nici la neamul kazah, însã ca artist absorb mirosurile acestui pãmânt. Avem aici foarte mult spaþiu. Dar, dupã cum ºtim, am avut ºi mai mult. Popoarele care au locuit aici aveau o tradiþie de marcare a teritoriului lor legând cârpe de tufiºurile, copacii, pietrele din jur.

Deoarece Hoarda de Aur a ajuns ºi în Moldova, eu am hotãrât sã amintesc de vechea ei prezenþã prin obiectul “Pomul Vieþii”.

Acest obiect este remarcabil ºi prin faptul cã foiþele de aur reprezintã unul din materialele mele preferate, pe care le folosesc în lucrãrile mele grafice. Privitor la costumul meu, acesta nu este deloc un costum tradiþional, cu toate cã poartã urma mai multor culturi, fiind mai degrabã veºmântul festiv al artistului Vsevolod Iurievici Demidov, cetãþean al Universului.

The Tree of Life

I am Russian by blood, but for me this holds little meaning. I live on the land of Kazakhstan. I feel very comfortable here. Of course, I cannot say that I am a Kazakh either, but as an artist I imbibe the smell of this land.

We have a lot of space here. But there used to be, as we know, even more. The peoples who used to live here had a tradition of marking their territory by tying pieces of cloth to nearby bushes, trees, stones, etc. Since the Golden Horde made it all the way to Moldova, I decided to remind of its ancient presence by my object called The Tree of Life. This is important also because gold foil is a favorite material with me, which I use in my graphic work. Concerning my outfit, this is by no means a national costume, although it does have imprints of various cultures; this is rather the festive attire of the artist Vsevolod Iurievich Demidov, citizen of the Universe.

20

Danube and founded a new state – the first Bulgarian state, which adopted Christianity in 864-865.

Istoria Moldovei. Publication of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Moldova, Institute of History, 1992

The old Russian chronicle Povesti vremennykh let (early 12th c.) mentions the “volokh” in 898 in connection with the invasion of Hungarian tribes from the east, from the northern coast of the Black Sea towards the Middle Danube plain.

Istoria Moldovei. Publication of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Moldova, Institute of History, 1992

Eross Istvan

Loc marcat 1 ºi 2

Marked Place 1 & 2

In the late 10th c.-11th c., the largest part of the Carpathian-Nistrian territories were invaded by the Patzinaks. But their domination was short-lived, since in the early 11th c. the Patzinaks were taken over by other Turkic nomads. Under their pressure the Patzinaks had to cross the Danube into the Byzantine Empire.

During the 11th and the following centuries, the progressive process of development, especially in the extra-Carpathian space, stagnated just like at the turn of the 4th and 5th c.c., when a new wave of invasions by nomads (Patzinaks, then later Cumans, Tartars) destroyed a great part of local settlements. During the 12th-13th c.c. the population from

21

Începând cu sfârºitul sec. X-sec. XI, cea mai mare parte a teritoriilor carpato-nistrene a fost invadatã de pecenegi. Însã dominaþia n-a fost de lungã duratã, cãci în prima jumãtate a sec. XI asupra pecenegilor au venit alþi nomazi de origine turcicã – torcii. Sub presiunea torcilor pecenegii au fost nevoiþi sã forþeze Dunãrea ºi sã intre în posesiile Imperiului Bizantin.

În decursul sec. XI ºi al celui urmãtor, procesul progresiv de dezvoltare a societãþii, în special în spaþiul extracarpatic, stagneazã ca ºi la intersecþia sec. IV-V, când un nou val de invazii nomade (pecenegi, uzi, iar apoi ºi cumani, tãtari), distruge o mare parte a aºezãrilor bãºtinaºe. În secolele XII-XIII populaþia din zonele afectate de invaziile nomade se deplasase în mare mãsura din câmpie în preajma marilor masive forestiere, regiunilor deluroase ºi a

Text ºi imagini selectate de Octavian Eºanu

Text and Images selected by Octavian Esanu

depresiunilor submontane.

Istoria Moldovei. Publicaþia Academiei de ªtiinþe a Republicii Moldova, Institutul de Istorie, 1992

Cãtre mijlocul sec. al XIII-lea o mare parte a pãmânturilor dintre Carpaþi ºi Nistrul au rãmas destul de slab populate în rezultatul multiplelor incursiuni ale nomazilor, care s-au încheiat cu invazia Hoardei de Aur din anii 1241-1242.

Istoria Moldovei. Publicaþia Academiei de ªtiinþe a Republicii Moldova, Institutul de Istorie, 1992

În sec. XII-prima jumãtate a sec. XIII Regatul Ungar ºi-a extins sfera de influenþã politicã ºi în partea de sud a Carpaþilor Rãsãriteni, însã cãtre mijlocul sec. XIII aceste teritorii au fost invadate de hoardele mongolo-tãtare. În 1241, în drum spre Europa Centralã, ele au

OTHER PEOPLE THINK

b y J o h n C a g e

T h i s e a r l i e s t o f C a g e ’ s e x t e n d e d w r i t i n g s w a s p r e s e n t e d i n 1 9 2 7 a t t h e H o l l y w o o d B o w l , w h e r e C a g e , r e p r e s e n t i n g L o s A n g e l e s H i g h S c h o o l , w o n t h e S o u t h e r n C a l i f o r n i a O r a t o r i c a l C o n t e s t

W

hen Washington was proclaimed President of the United States, our country possessed most of the territory between the Atlantic and the Mississippi River. After the Mexican War, the Stars and Stripes were flown from ocean to ocean, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes. Today the United States is a world power. In the New World, she calls Alaska, Porto Rico, and the Virgin Islands territories. She exerts a strong influence over Haiti, Nicaragua, Panama, and the Dominican Republic. She has circulated her dollar throughout the Latin American countries until she is spoken of as the »Giant of the North« and thought of as the »Ruler of the American Continent.«5 6 7 3 4 8 2 MARTA

22

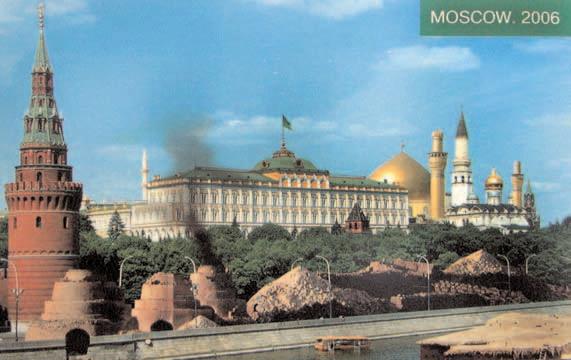

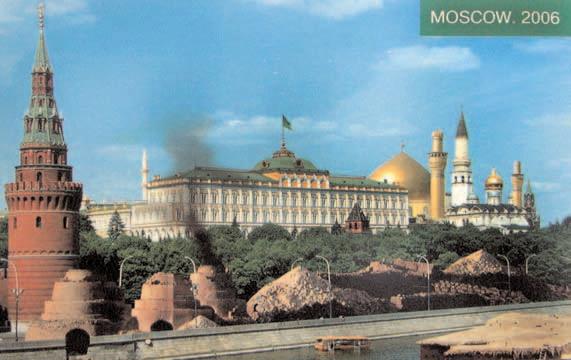

Extracts from »John Cage: An Anthology« edited by Richard Kostelanetz, A Da Capo Press, 1970 R E P R O D U C T I O N S : 1. AES ‘Witness o the Future Moscow 2006’ postcards 1996 2 Ch ldren Moldova 2001 3. September 11, 2001 Photo Reuters 4. See You Soon peg www yahoo com 5. Mark Verlan German Bombardier Fa l ng nto the F e d’ (canvas oil) 1993 6. L bertyfinger peg www yahoo com 7. A exander Cul uc ‘K ng Ste an the Great’ http://www sander ournet md 1999 8 Manhatan September 11, 2001 Photo Reuters

Latin America is a land of the future. It is the potential producer of most of the food and raw products for all the world. A1ready each of the twenty Latin American countries is noted for a product upon which the rest of the world is dependent. We rely on Brazil for our coffee, on Cuba for our sugar, and on Argentina for our wheat. These twenty countries also represent a market for the

the areas affected by nomad invasions moved from plains closer to wooded areas, hilly regions and submountainous recessions.

Istoria Moldovei. Publication of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Moldova, Institute of History, 1992

Towards the middle of the 13th c. a large part of the lands between the Carpathians and Nistru had become sparsely populated as a result of multiple incursions by nomads, which ended with the invasion of the Golden Horde of 1241-42.

Istoria Moldovei. Publication of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Moldova, Institute of History, 1992

world’s manufactures. Without doubt Latin America will experience a Golden Age in the near future. To cultivate friendly relations between North and South America will be a greater advantage mutually than it is at present or has ever been in the past.

Because of Uncle Sam’s military power, Venezuela has been protected from Germany, Cuba from Spain, Mexico from France; we have defended all weak countries from European domination. We are governing Santo Domingo because the natives tried but failed. We are educating the Negroes of Haiti so that they may learn how to handle their own affairs. The United States has rid many countries of the curse of revolution. Many of the smaller republics have progressed in civilization because of American Finance. Panama is Panama because of our interests in the Canal. All in all, our intervention in Latin America has been actuated by altruistic motives.

Why, then, is there any misunderstanding between the Latins and the Anglo-Saxons of this continent?

There are two sides to every question. For other people think otherwise.

Concerning the question of American Intervention in Latin America, many people are thinking otherwise. The foremost literary men of the Southern Countries, led by Manuel Ugarte, are instructing their readers how to think. The professors of the great South American Universities are teaching the students what to think. The statesmen, guided by Dr. Honorio Pueyrredon, are thinking and beginning to make their countries think.

This thought, that has penetrated the intellectual life of the Latin Republics so effectively, has been influenced by the actions of certain citizens of the United States. The great majority of these are capitalists who have zealously invested money in the Southern Republics and eagerly exploited them. They have not the hope of progress of others, but only the desire for their own material advancement. They are of the family of the utterly selfish. They have not only been financially successful; they have succeeded in gaining for themselves the contempt and the aversion of men. They belong to a crazed congregation of Gold-Worshippers. And it is difficult to convict them of wrong-doings, for they are extremely sly and hypocritical. These are our Ambassadors to Latin America. In the eyes of the Southern People, these men are the United States. These are the books in which Latin Americans read our history, the pictures which portray for them Anglo-Saxon ideals.

Six years ago, three American Banking Companies loaned 26 million dollars to the Republic of Bolivia. It was provided in the contract that 10 per cent of the principal should be paid annually in monthly installments, with the interest at 8 per cent. In the case of a default on the part of the Country, the Bankers will be given complete control of the Bolivian National Bank, certain Bolivian railroads, and the Revenues of the Republic. According to this contract of 1922, the Government of Bolivia is forbidden to borrow other money without the consent of the American Bankers. For the administration of these provisions and the supervision of Bolivian Finances, a permanent Fiscal Commission was formed. It consists of three members appointed by the President of Bolivia, two of whom are recommended by the Americans. As a result, the economic future of Bolivia is subject to the will of a handful of Bankers. This is, however, but one instance of the actions of American Capitalists. There are ties that have fastened the hearts of every Latin American Country inveterately with the countinghouses of Wall Street.

Is Latin America correct in calling our altruism masked imperialism? Should we continue to intervene in Latin America? What would the great men of our history do in this dilemma? Would not Lincoln champion the cause of the weak? But would not Roosevelt justify American Intervention?

What are we going to do? What ought we to do?

One of the greatest blessings that the United States could receive in the near future would be to have her industries halted, her business discontinued, her people speechless, a great pause in her world of

In the 12th-early 13th c.c. the Hungarian kingdom expanded its sphere of political influence over lands south of the Eastern Carpathians, but towards the middle of the 13th c. those territories were invaded by the Mongolian Tartar hordes. In 1241, on their way to central Europe, they devastated the northern regions of the Carpathian-Nistrian space, and in 1242 Batu’s hordes, on their way back to the northern Pontic steppes, passed through the southern regions of that space, destroying everything in their way.

Istoria Republicii Moldova. Publication of the Association of Scholars of Moldova “N. Spatarul Milescu”, Chisinau, 1997

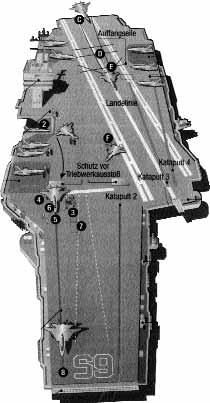

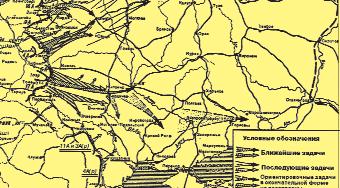

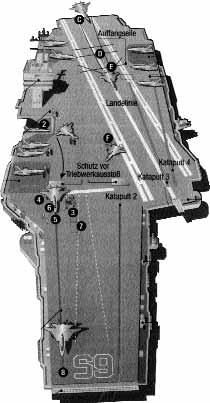

So funktioniert ein USFlugzeugträger

ge b Leiten-Flugzeug-Manöver an Deck grün arbeiten am Katapultund am Fngseil violett Betanken

blau bringen die Flugzeuge in Position braun koordinieren Arbeiten an einzelnen Flugzeugen

342 m

• Breite:40.80 m

• Tiefgabg: 11.30 m

• Besatzung: 4935 Mann

Pilot steuert Landebahn an

Pilot richtet sich nach Lichtsignalen, dieihm sagen, ob er richtige Flughöhe einhält Flugzeug setzt mit ca. 300 km-h auf

23

3 bis zu 86 Flugzeuge: • F-14 Tomcat • F/A-18 Hornet • EA-6B Prowler • E-2C Hawkeyes • S-3A/B Vikings • SH/HH-60 Seahawks

1 2 4 6 7 5 B e s p e U S S E n t e r p r s e

Länge:

•

A B C F-14 Tomcat 8 Schiff dreht in den Wind. Jet wird mit Lift an Deck gebracht.

Maschine

Startposition.

wird

Katapult gehakt. Pilot gibt Signal: startklar. Katapult-Offizier gibt Startzeichen. Katapult beschleunigt Maschine in gut 2 Sekunden auf 300 km/h.

Raketen und Bomben werden.

rollt an

Jet

ins

silber

Rettungskräfte

devastat regiunile de nord ale spaþiului carpato-nistrean, iar în 1242, întorcându-se în stepele nord-pontice, hoardele lui Batu, nimicind totul în calea lor, au trecut prin regiunile de sud ale spaþiului.

Istoria Republicii Moldova. Publicaþia Asociaþiei oamenilor de ºtiinþã din Moldova “N. Spãtarul Milescu”, Chiºinãu, 1997

În 1284-1285 Hoarda de Aur întreprinde o a doua invazie împotriva Regatului Ungar (prin Regatul Halici-Volîn) în frunte cu hanul Telebuga ºi emirul Nogai, ale cãror seminþii duceau o viaþã nomadã pe litoralul de nord-vest al Mãrii Negre. Dupã aceastã campanie devastatoare a hoardelor lui Nogai ºi Telebuga, primul, urmând drumul pe la Braºov, trecãtoarea Oituz

ªI ALÞII GÎNDESC*

(Acest text timpuriu al lui John Cage a fost prezentat în 1927 la Concursul Oratoric al Californiei de Sud, Cage reprezentând Liceul Los Angeles ºi câºtigând concursul.)

Cînd Washington a fost proclamat preºedinte al Statelor Unite, þara noastrã poseda cea mai mare parte din teritoriile dintre Oceanul Atlantic ºi rîul Mississippi. Dupã rãzboiul cu Mexic, steagul american fu arborat de la ocean la ocean, de la Golful Mexic pînã la Marile Lacuri. Astãzi, Statele Unite sînt o putere de rang mondial. În Lumea Nouã, þara noastrã numeºte Alaska, Porto Rico ºi Insulele Virgine teritorii. Þara noastrã exercitã o puternicã influenþã asupra insulei Haiti, asupra Nicaragua, Panamei ºi Republicii Dominicane. ªi-a circulat dolarul prin þãrile Americii Latine, fiind pomenitã drept „Gigantul nordului" , despre care se gîndeºte drept „Cîrmuitorul continentului american".

Privind problema intervenþiei Americii în America Latinã, pãrerea multora este de altã naturã. Bãrbaþii de primã însemnãtate ai literaturii Þãrilor Sudice, în frunte cu Manuel Ugarte, îºi instruiesc cititorii cum sã gîndeascã. Profesorii de la marile universitãþi ale Americii de Sud îºi învaþã studenþii ce sã gîndeascã. Bãrbaþii de stat, fiind ghidaþi de Dr. Honorio Puyerredon, gîndesc ºi încep sã-ºi facã þãrile lor sã gîndeascã.

Aceastã gîndire, care a penetrat cu atîta eficienþã viaþa intelectualã a republicilor latine, a fost influenþatã de acþiunile unor cetãþeni ai Statelor Unite. Marea majoritate a acestora sînt capitaliºtii care au investit stãruitor bani în republicile sudice, exploatîndu-le setos. Ei nu sînt conduºi de speranþa cã alþii vor realiza progrese, ci doar de dorinþa propriei avansãri materiale. Ei fac parte din familia egoiºtilor totali. Ei nu au realizat numai succese financiare; ei au reuºit sã capete dispreþul ºi aversiunea oamenilor. Ei fac parte din congregaþia înnebunitã a Adoratorilor Aurului. ªi este greu sã-i învinuieºti de nelegiuiri, deoarece ei sînt extrem de vicleni ºi prefãcuþi. Aceºtia sînt ambasadorii noºtri în America Latinã. În ochii populaþiilor sudice, aceºti oameni reprezintã Statele Unite. Aceºtia sînt cãrþile din care latino-americanii ne citesc istoria, imaginile care reprezintã pentru ei idealurile anglo-saxone.

Acum ºase ani, trei bãnci americane au dat Republicii Bolivia un împrumut de 26 milioane de dolari. În contract se stipula cã 10 la sutã din valoarea împrumutului trebuie achitate anual, în rate lunare, la o dobîndã de 8 la sutã. În cazul defaultului þãrii, bãncile obþin controlul deplin al Bãncii Naþionale a Boliviei, al unei pãrþi a Cãii Ferate naþionale, cît ºi al Veniturilor Republicii. Conform acestui contract semnat în 1922, guvernului Boliviei i se interzice sã împrumute bani din alte surse fãrã consimþãmîntul bancherilor americani. Pentru a administra aceste prevederi, cît ºi pentru a supraveghea Finanþele Boliviei, a fost formatã o Comisie Fiscalã permanentã. Aceasta constã din trei membri numiþi de preºedintele Boliviei, dintre care doi sînt recomandaþi de americani. În consecinþã, viitorul economic al Boliviei e la discreþia unei mîini de bancheri. Acesta însã este doar un exemplu al

dintre Carpaþii Orientali ºi Meridionali, ºi mai departe prin regiunile sudice de stepã dintre Nistru ºi Dunãre, s-a înapoiat la nomazii sãi.

Istoria RSS Moldoveneºti. Chiºinãu, 1968

Ungurii au invadat Moldova în rezultatul evenimentelor internaþionale, în care ea a fost implicatã în cea de-a doua jumãtate a sec. XIII ºi în prima jumãtate a sec. XIV dupã invazia Hoardei de Aur.

Istoria Moldovei. Publicaþia Academiei de ªtiinþe a Republicii Moldova, Institutul de Istorie, 1992

affairs created, and finally to have everything stopped that runs, until everyone should hear the last wheel go around and the last echo fade away . . . then, in that moment of complete intermission, of undisturbed calm, would be the hour most conducive to the birth of a Pan-American Conscience. Then we should be capable of answering the question, »What ought we to do?« For we should be hushed and silent, and we should have the opportunity to learn that other people think.