14 minute read

Threshing Contractors A reminder of how

LEFT: A Saunderson Model G tractor threshing in Cheshire at around the time of the First World War. Saunderson claimed that the 25hp Model G would drive a full-size drum.

Advertisement

BELOW: The American steel threshing machines were uncommon in Britain, although several peg drums were brought in by International Harvester during the 1930s. This machine, fitted with a ‘wind stacker’, is belted to an International 22-36 tractor.

The David brown VTK1 ‘Thresherman’ was the latest in power sources for the drum in 1946. This tractor is using its front-mounted belt pulley to drive a Marshall threshing machine in Yorkshire. The baling press is a Jones Tiger.

Today, little thought is given to how the harvest is gathered. Massive combines sweep the fi elds and the task is accomplished in the shortest possible time. However, the days when horses cut the corn and steam power threshed the grain are still within living memory.

The idealistic image of a horse-drawn binder striding through elds of golden corn paints a romantic picture, but the reality was not so idyllic. The work was hard and the days were long for both the men and the horses. A er the binder had cut the crop, the sheaves were stooked in the eld. When the corn had dried and ripened, which could be anything from a few days to a few weeks, the sheaves were carted to the stackyard.

In the yard, the sheaves would be built into stacks or ricks. Building the stack was a skilled job and great pride was taken in its appearance. The nished stack would be thatched to keep out the rain until the threshing gang arrived.

The arrival of the threshing contactor on the farm was a greatly anticipated event, heralding a period of intense activity. Excitement would mount as the traction engine turned into the gate with its train of equipment in tow. The steamer was a magni cent sight, but its dominance of the threshing scene was already being eroded as early as the 1920s by the arrival of the internal combustion engine on the farm.

The transition from steam to tractor power had already begun, albeit in a small way. A er the First World War, quantities of tractors, ploughs, traction engines, threshing and baling

A Claas Super combine being used for stationary threshing sheaves from the stack. The combine, driven by a 1957 Fordson Diesel Major, is fitted with a trusser, and DB and Ferguson tractors are on hand to cart away the straw.

equipment, wagons and motor vehicles had been disposed of by the Ministry of Munitions. Several contractors took this opportunity to equip themselves with the latest farm motor.

It was a very slow and gradual change; most stayed with steam, and the traction engine remained the mainstay of the threshing contractor into the 1940s. One of the problems with the early tractors was that they hadn’t got the power to drive the big drums. The standard threshing machines of the time were heavy and bulky, designed for steam power and not very handy for tractor operation.

Early tractor pioneer, Saunderson & Mills, marketed its own drums, the No.1 single-blast 3 6in model and the No. 2 double-blast 4 machine, but only for a short time. Following the launch of its British Wallis tractor in 1920, Ruston & Hornsby introduced its Tractor Thresher, a lightweight machine with all the working parts running on roller bearings.

Although compact in design for tractor operation, weighing just 3.5t, Ruston & Hornsby’s machine was a full-size thresher with a 54in drum.

An International W-30 on the road with a drum and elevator in tow. The outfit was owned by R. P. Watts Ltd of Thorpe Latimer, near Sleaford, in Lincolnshire, and the tractor was used for threshing duties well into the 1960s.

The design was later taken over by Ransomes, Sims & Je eries.

As tractors became more powerful and more capable, an increasing number of contractors were persuaded to make the transition. The International 10-20, 15-30 and W-30 models were popular tractors for driving drums. To drive a drum, a tractor engine needed to be able to run all day with minimal attention, have plenty of torque at a steady engine speed, and a responsive governor.

Other popular models of tractor for driving drums during the Second World War were the International W-9, Case LA, John Deere D, Oliver 90 and Minneapolis-Moline GT. M-M importer, Sale Tilney, o ered a special contractor’s version of the GTA with cast-iron rear wheel

The threshing bill

RIGHT: An invoice for threshing issued by a South Lincolnshire contractor in 1944. The cost of 33 hours of threshing,

Most contractors belonged to the National including labour, was £47 17s 3d. Traction Engine Owners & Users Association, which was later renamed the National Traction Engine & Tractor Association to reflect the change of motive power. This body offered guidance on rates of hire for the threshing tackle.

Most contractors charged by the hour, the bill being calculated on the type of equipment used (drum, baler, trusser, chaff cutter or elevator) and the number of men required. However, some farmers preferred to pay on output with the rate calculated per bushel, sack or quarter of grain.

An Allis-Chalmers Model U powers the drum on a farm in Devon in 1937. The Model U’s responsive governors made it an excellent threshing tractor, and it was also one of the first machines to be fitted with pneumatic tyres.

centres and an improved braking system to handle a heavy drum.

These big tractors could pull and drive the same heavy drums as the steamers. Foster threshers, made in Lincolnshire, were the rst choice for contractors. They were a quality product that produced a quality sample but, more importantly, they were well designed and easy to feed.

Ransomes came a close second to Foster, but all the others were alsorans. The drum that was least liked was the Marshall, especially its wartime steel threshers, usually referred to as ‘tin’ drums.

Small numbers of steel threshing machines were also imported from the USA. The only one that sold in any quantity, and even then numbers were extremely low, was the International Harvester peg drum. Case, Oliver and Massey-Harris also marketed their machines in Britain, but hardly any were sold.

The trusser and baler were the other tools at the contractor’s disposal. Straw was a valuable commodity, particularly the long-strawed varieties for thatching. In the Fens, straw was in demand for potato clamps and the onset of the potato harvest o en governed the timing of the threshing operation. In the same way, threshing in the stock areas would be timed to meet the cha and straw needs of the over-wintered cattle.

Even during the Second World War, with combines only available in limited numbers, it was still the binder that did the lion’s share of the work when it came to gathering Britain’s vital wartime cereal crops. Nearly 3.5m tons of wheat was harvested in Britain in 1943, and there were 144,000 binders on British farms, so the threshing machine was still in great demand.

The arrival of the tractor not only sounded the death knell for steam, but it also threatened the livelihood of some contractors; tractors and tractorthreshers were more a ordable than steam out ts and many farmers bought their own machines.

In the post-war years, many contractors used Field Marshall or Fordson E27N Major tractors to power their drums. Marshall o ered special Contractors models complete with winches and other equipment. David Brown also marketed its VTK1 Thresherman from 1946-47.

Despite its popularity for belt-work, a Field Marshall was thought by some not to govern as well as it should. One fenland contractor modi ed his Marshall with the governors o a Massey-Harris 726 combine. Although a cheaper proposition, if an E27N Major was in constant use on a drum, its governors had to be renewed periodically.

Binders and threshing machines were still made in Britain into the 1950s, but the relentless march of the combine would soon bring their era to a close. Foster built its last threshing machine in 1961. Most of the later drums supplied by the various rms were tted with pneumatic tyres and were designed for tractor use.

Many contractors made the transition to combines, but several shut up shop and went out of business. For those farmers that persevered with the binder, it was not unusual for a contractor to use a combine for stationary threshing. Some of the last drums to be used commercially in Britain were clover hullers for grass seed.

THE THRESHING DAY

A typical threshing gang would normally consist of eight men. If the drum had no self-feeder, an extra man would be required to cut the bands on the sheaves. The contractor normally supplied just the driver and the feeder, with the rest of the gang being drawn from the farm’s full-time sta or casual labour.

The feeder would double up as the steersman in the steam days, but the arrival of the tractor meant that he had to ride behind on a bicycle when travelling on the road. While moving from farm to farm, the driver and the feeder were paid shi money, normally about half-a-crown.

When the out t arrived in the yard, it would pull between the stacks. An average stack would be about eight yards long by six yards wide and contain about ten acres of

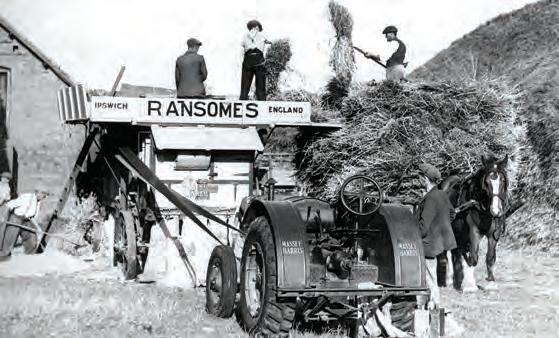

LEFT: A Massey-Harris 12-20 tractor driving a Ransomes Medium threshing machine near Stratford-onAvon in 1936. The Ransomes drum had a good reputation and was popular with contractors.

sheaves – enough for a day’s threshing. The tractor would then run around the drum to line up for the belt. Manoeuvring in the yard was much easier with a tractor than a steamer, with less risk of getting stuck.

Lining up to the belt was also easier with a tractor, which could be reversed to tighten the belt. Positioning a traction engine was a skilled a air, and it was o en lined up using a piece of string cut ABOVE: If you were not wearing your Wellington boots, then it to the correct length of the belt. was customary to keep them upturned on the end of the pitchfork

On some early tractors, where handle to keep the mice from nesting inside. the belt pulley ran constantly, it was a two-man job. The belt had to be tensioned as it began to revolve, and a man had to be ready to chock the tractor’s rear wheels as the driver reversed into position and dropped it out of gear. Di cult and dangerous!

Next, the drum was prepared for work, and it was the feeder’s job to set-up the tables and cross-boards while the gang took out the thatchpegs on the stack. Before threshing commenced, the rat wire was erected. This 3 high netting was very important in the Fens where the many ditches and watercourses harboured a rodent problem. The wire was to contain the rats that came out of the stack so they could be caught and killed. Rat catching was an important sideline for the threshing gang, who were customarily paid a penny a ‘tail’ by the farmer. Many of the gang would keep dogs, usually Jack Russells, just for this purpose. The dead rats would be dropped in a barrel and were counted up at the end of the day. Some large stacks could harbour as many as 500 rats so it could be a pro table exercise, provided you remembered to keep the bottom of your trouser-legs tied up with string. So important was the need to control the rodent population that it was not unknown for the local police to check on the threshing contractors to ensure they were setting up their rat wires correctly.

Most threshing gangs welcomed the move away from steam to tractors because they no longer spent their day working in the smoke. It could be particularly bad on a foggy day when the smoke hung low in the stack-yard. Some of the dedicated engine drivers bemoaned the loss of their steamers, and “A typical threshing gang would normally consist of eight men” there are tales of contractors o ering to sell the drivers their engines for as little as £15 in the 1950s. Once he had lled his tank (a typical petrol/para n tractor used about two gallons of vaporising oil an hour when threshing and its tank would need to be lled twice during the day) the tractor driver had very little to do. This was not always an advantage: the engine driver could

Contractors model

RIGHT: A sales brochure for the Field Marshall Mark 2 Series 2 Contractors model, introduced in 1947.

The Mark 2 version of the Field Marshall, introduced in 1945, was a special Contractors model with a built-in winch, rear wheel brakes, a canvas canopy and lighting equipment. Aimed at the threshing contractor, the tractor had a top speed of 9mph and cost £840. The winch, driven by an auxiliary gearbox, was mounted beneath the driver’s platform.

Launched in 1947, the Field Marshall Mark 2 Series 2 was another Contractors model with a heavy-duty Marshall winch. A light-duty Hesford winch was offered as alternative equipment. The tractor, priced at £870, was primarily aimed at threshing contractors, but sales were also made to timber merchants and the industrial market.

David Brown ‘Thresherman’

ABOVE: A Field Marshall Mark 2 Series 2 Contractors model with a heavy-duty Marshall winch. The tractor belonged to South Lincolnshire threshing contractor, W. Taylor & Son of Sutterton. The Marshall was popular with the threshing fraternity, although some were critical of its governors.

busy himself with coal and water, while the tractor operator might be expected to help the feeder.

Unlike the engine man, the tractor driver didn’t have to arrive 45 minutes early in the morning to get steam up (two hours earlier on a Monday when starting from cold, which meant a 5am start). He could also leave at the same time as the rest of the gang without needing to stay behind to let the steam out. Neither did he have to cycle out to his engine on a Sunday to wash the boiler out.

Threshing, which normally commenced at 7am, was dusty and tiring work. The men would usually have just a bottle of cold tea or ‘dregs’ for refreshment. The sheaves scratched hands and arms, which were already irritated by awns and the odd thistle, so experienced labourers kept their sleeves rolled down.

There was a break for lunch, usually called ‘dinner’ or ‘docky’, at 11am or

ABOVE: A rare colour image of threshing in South Lincolnshire in the 1950s. The machine is a late Foster drum, which is being driven by a Field Marshall Mark 2 Series 2 off-camera. A 1953 Ferguson TE-F20 tractor with a Scottish Aviation cab is also in attendance.

David Brown’s ‘Thresherman’ was officially the VTK1 Heavy Duty Tractor (Threshing Model). Based on the company’s wartime Air Ministry tractors, it was fitted with a petrol/ paraffin engine to the latest VAK1/A specifications.

The equipment included a David Brown winch, sprag, rear towing hitch and a front-mounted shunting socket, ideal for manoeuvring or recovering a threshing drum on soft ground. Heavy-duty electric starting and lighting was standard. A belt pulley with its own gearbox was mounted at the front of the chassis frame. Priced at £750, approximately 85 VTK1 models were built from 1946-47, with others being based on reconditioned aircraft tugs.

11:30am. Sustenance was probably a thick wedge of bread, covered with a piece of fat bacon or a slice of cheese, topped o with a thin slice of bread known as the ‘thumb piece’. It would be cut with the same knife that had probably just gutted a rabbit or even possibly dealt with a rat!

There would usually be another break, called the ‘smoke break’ because smoking was banned on the stack or near the drum because of the re risk, at about 1pm in the a ernoon. The threshing would nish about 4pm, which was a long enough day when the wheat was in 18-stone railway sacks.

Modern combines can cut as much in half a day as the old threshing gangs would do in a season. But can progress replace the bustle and excitement once generated by working to the beat of the drum?

ABOVE: Sales literature for the David Brown VTK1 Heavy Duty Tractor (Threshing Model), produced from 1946-47.