Production notes

Getting Hip

Your daY begins at 4:00am with two successive showers.

You remove any rings or jewelry, dress in loose clothing, drink your permitted four ounces of coffee. Your caregiver drives you to the hospital.

A welcoming nurse guides you to a pre-op bay and comfy chair, asks for your birthdate and gives you a wrist band affirming your identity. You doff clothes, eyeglasses, cell phone and ID into a labeled plastic bag. The too-small hospital gown gapes in the back.

Another nurse drapes you with a metallic space blanket filled with warm air. The anesthesiologist introduces herself and describes her process. You’re given six packets of sterile wipes and asked to sponge yourself clean yet one more time.

The preoccupied surgeon appears briefly, greets you, and autographs your right hip with a felt pen just to make sure he’ll be replacing the correct joint.

At 8:15 you’re wheeled into a room almost blindingly bright, the O.R., and given a spinal anesthetic. When it’s clear it’s working, you’re “put to sleep” for the duration.

The sleep is well advised. Orthopedic surgery can be “a lot of hammering and sawing, like a home renovation project,” according to one nurse. Your arthritic ball and socket and upper femur are cut out. The surgeon installs, with the help of a robot, a metal-ceramic artificial joint in your pelvis. Your new right hip. You awake from sedation in an ICU, oxygen and blood pressure closely monitored, and do breathing exercises to help banish the anesthetic. Teams of therapists outline restrictions on your movements, diet, and sleep posture. Your caregiver fills seven drug prescriptions. You’re helped into your clothes, guided into a wheelchair, and driven home at 4:45pm

Six weeks of rehab and you’ll be dancing the light fantastic.

The medicine of mobility

The imposing offices of Pacific Surgical Institute offer its patients comfortable surroundings and the promise of first class care. But no one, not even one of the region’s elite private surgical centers, escaped COVID-19 unscathed.

“We shut down for seven weeks, immediately,” said Dr. Bill Turner, one of Pacific’s six surgeon-partners. “Never experienced anything quite like it. Then reopening, but operating with all kinds of extra precautions. People didn’t stop breaking their legs and limbs just because of COVID.”

– American Academy of Family Physicians the pandemic, but beleaguered ERs and primary care providers suffered full-on. According to U.S. News, one in five health care professionals lost their jobs during the first two months of the crisis, as caregivers mobilized, improvised, quit or fled. Even today hiring has not yet brought professional staffing back to pre-COVID levels.

“There was a lot of psychological trauma,” said Turner, “and remember, a lot of people just refused to believe it was real. And often by then it was too late.”

Wellness Comes of Age

Specialty practices like Pacific were out of the direct line of fire during

Today, healthcare struggles to return to normalcy. Staffing is still a big issue (see

ONE IN FIVE HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS LOST THEIR JOBS

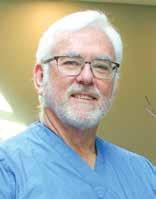

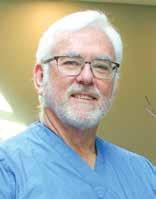

Dr. Bill Turner

sidebar, pg. 19). Patient demographics are changing, with an aging population dominating demand.

On the positive side, the continuing emphasis on wellness — preventative care and medical interventions improving quality of life, not just treating illness — offers benefits for both patients and caregivers. But this too is dramatically changing the healthcare landscape.

As Baby Boomers enter the so-called Golden Years, their extended life expectancies and active lifestyles put more pressure on their aging bodies. The result is not only more attention to diet and fitness, but also increasing demand for “elective”medical procedures.

cont page 18

April 15, 2024 / Columbia River Reader / 17

A monthly feature written and photographed by Southwest Washington native and Emmy Award-winning journalist Hal Calbom

•••

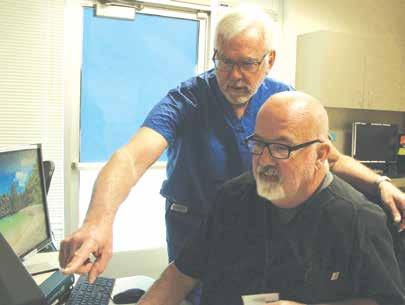

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and other sophisticated technologies have revolutionized health care, especially imaging. (above) Dr. Bill Turner reviews an MRI image with MRI Manager Pat Burns at Pacific Surgical Institute; MRI machine in the background.

from page 17

Hence the rise of specialty practices, and freestanding surgery centers that can offer more nimbleness and focus than large multi-service hospitals.

The Diagnosis Difference

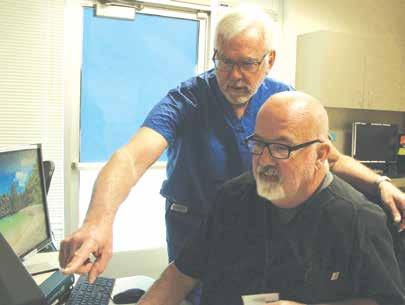

At left: Dr. Turner with longtime patient John Searing, who has had both shoulder and knee surgeries at Pacific Surgical Institute. “The surgeries have allowed me to still enjoy an active lifestyle,” said Searing. PSI employs more than 70 people under the direction of six surgeon-partners, broadening their surgical business with imaging, physical therapy and urology services.

WE HAVE ACCESS TO MUCH BETTER IMAGES NOW

“We have about 50,000 patient visits per year,” Dr. Turner told us, “That’s orthopedics, physical therapy, urology, the surgery center and MRI.” The complex hosts a busy imaging business, dominated by the colossal MRI — Magnetic Resonance Imaging — machine. We are advised to keep our distance from the powerful magnet, which can literally pull metal jewelry from wrists and fingers.

“We have access to much better images now,” said Turner. The MRI and other powerful technologies have accelerated the revolution in the way physicians diagnose, treat and rehabilitate their patients. Pacific even employs the services of specialist medical consultants to interpret their sophisticated images and confirm their own diagnoses.

The result is unprecedented awareness of patient problems, accuracy and efficiency in their treatment, and improved outcomes, often with shorter patient stays and less overall health impact.

‘When I got out of med school, you had a pretty basic response to a potential heart attack,” Turner told us, “morphine, oxygen, aspirin, and maybe catheterization.” Today symptoms can be confirmed almost instantly, a clot busting injection administered, a stent installed if needed, “and the patient goes home the next day.”

Even the veteran surgeon marvels at the changes in technology. “I’m still learning every day.”

Boomer Blues

“The great thing about orthopedics is I get to work with a three year old one day and a ninety-year old the next,” said Bill Turner. But that can be both good and bad news.

Good news because business is potentially booming in health care, but costs, staffing, regulatory policies and insurance hassles remain troubling. And, as with so many other social phenomena we’ve followed over

the last six decades, the Baby Boom Generation is exacerbating these problems.

“There are so many ridiculously healthy eighty-year-olds out there you wouldn’t believe it,” said Turner. But like dependable old cars that run well beyond their expected mileage and life span, there’s a maintenance burden, too. “Joint replacements get a lot of attention,” he added, “and we did around 900 of them last year.” But the bigger burden by far is more mundane: basic maintenance like strains, pulls, trauma, sports medicine, hands and feet, broken bones.

Physician, Heal Thyself

Simply put, we are losing doctors and nurses faster than this accelerating demand. So much so that healthcare organizations and observers see great stresses on existing systems through the rest of this decade and well into the 2030s.

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus uses this “physician” maxim ironically: Many interpreters suggest he’s foreshadowing a life devoted to saving others when in the end he cannot save himself. Such would seem to be the case with healthcare professionals and the Baby Boom: the majority of them are baby boomers themselves. According to the American Medical Association 55 percent of practicing physicians are over age 55; and the New York Times reports that over 650,000 nurses are boomers nearing retirement.

Hence the irony — the Baby Boom wreaks demographic havoc two ways: pressing up demand thanks to their collective aging, and decimating the ranks of healthcare providers thanks to their own imminent retirements.

Planners and health professionals call this a “looming public health crisis” and are encouraging a next generation to embrace the profession.

“Imagine walking into an emergency room in your moment of pain,” said AMA President Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld in a recent speech, “in desperate need of a physician’s care, and finding no one there to take care of you. That’s what we’re up against.”

The Quality Community

Bill Turner is not ringing the alarm bell yet, thanks to the strength of his client base and the desirability of life in Longview. “When I started out, people used to see a place like LongviewKelso as a stepping stone to Seattle or Portland,” he told us. “But now, thanks in some ways to what’s going on in Seattle and Portland, they’re doing just the opposite and wanting to be here.”

Turner and his partners recruit physicians and staff typically from three places: fresh from medical schools and residencies; from the military; and from disaffected professionals who simply want to re-locate. “Quality of life is

18 / Columbia River Reader / April 15, 2024

People

Don’t blame the pandemic — entirely

The crisis in U.S. Healthcare has deeper roots and ramifications than the staffing strains crippling the system and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The New England Journal of Medicine highlights four intertwined root causes eroding our healthcare system.

Despite spending exorbitant amounts on care, ours ranks among the world’s poorest compared

CRISIS CAUSES

Insurance Coverage

•30+ million Americans uninsured

•40+ million Americans under-insured

Financial Losses for Providers

•Hospitals and private practices

•Changes in demand

•Reduction in routine services

Racial & Ethnic Disparities

•Urban ethnic poor suffer more sickness

•Minorities are chronically under-insured

Crisis in Public Health

•U.S. has poor health outcomes

•4% of world’s population

•25% of COVID cases

The New England Journal of Medicine

with other so-called developed nations. A recent Gallup Survey shows consumer confidence in the U.S. healthcare system the lowest it’s been in a decade: in answer to the question “who provides good or excellent medical care?” respondents said 8 of 10 nurses; 7 of 10 physicians; fewer than 6 of 10 hospitals; and only 5 of 10 providers of “virtual care” or telemedicine.

It’s impossible to over-estimate the accumulated effects of stress, burnout and low morale on the system and its practitioners. “The journey to becoming a physician has always been a challenge,” said AMA President Dr. Jesse Ehrenfeld, but now he says there are a host of societal factors coming into play.

Concerned planners and healthcare leaders point to a potential shortage of 30,000 to 100,000 physicians in 10 years, by 2034.

In the meantime the rest of us, demanding more and better healthcare all the time, can expect rising costs, crowded ERs not meant to triage the world, and temporary “travelers” filling in for nurses and technicians at exorbitant rates.

incredibly important,” he said, citing the ubiquitous wellness philosophy applied to health care doctors and staff. People want a community they can participate in, educate their kids in, improve their lives.

“Medicine is such a rewarding profession,” he said, “the good you can do, the way you can transform lives.”

Turner encourages young people to pursue medicine as a career every chance he gets. “There are so many different kinds of opportunities. And it’s such a privilege to be an important part of someone’s life. I honestly consider myself the luckiest guy in the world.”

The pandemic did not create a crisis in US. healthcare. For many in the United States, crisis was already a pre-condition of care, delivered in emergency rooms and negotiated through denied insurance claims.”

Dwaipayhan Banerjee, MIT

PHYSICIAN STRESSORS

•Increased administrative burdens

•Attacks on science

•Healthcare consolidation

•Broken Medicare payment system

•Cost of education, fewer med school openings

American Medical Association

And we can hope for aspiring physicians like Dr. Bill Turner, who still considers his noble profession “the best job in the world.”

•••

IT’S SUCH A PRIVILEGE TO BE AN IMPORTANT PART OF SOMEONE’S LIFE

•••

Besides offering diagnostic help, detailed images lend precision to procedures, increasing efficiency and minimizing patient impact. Top photo: Dr. Turner consults with Pat Burns, MRI manager at Pacific Surgical Institute.

Above: John Searing considers Dr. Turner “a friend as well as a doctor. His care is pretty personalized,” he said. “It’s like having your next-door neighbor as your doctor.”

Hal Calbom, a third-generation Longview native and author of Empire of Trees: America’s Planned City and the Last Frontier, produces CRR’s People+Place monthly feature, and is CRRPress associate publisher.

April 15, 2024 / Columbia River Reader / 19 + Place

“