From its utilitarian and modest period in the early 1900s, Swedish glass transformed into an artistic triumph – and source of national pride. Today, it remains Sweden’s most celebrated contribution to the applied arts.

By Kajsa NormanDuring the 100s AD, manmade glass from the Roman Empire first made its way to Northern Europe, either by plunder or trade. However, it would take many years before domestic production in the North began. Over the next millennium, the only glass made in Sweden was window glass for churches and monasteries.

In 1555, King Gustav Vasa invited Venetian glassblowers to Sweden to craft glass drinkware for the royal family. At this time, Italian Venice and German Bohemia were the only places in Europe capable of creating clear glass. Throughout the 1600s, glassworks manned with skilled foreign craftsmen begun to appear around Stockholm. While these artisans eventually trained Swedes in glassmaking, foreign experts retained the role of supervisors into the late-1700s.

Originally a luxury, domestic glassware became common in Swedish homes during the 1800s. By the 1830s, technologies such as pressing glass into fixed molds, instead of free-blowing it, reduced costs and enabled the creation of smaller household goods such as drinking glasses and vases.

Between 1870 and 1899, sixty

new Swedish glassworks appeared in rural areas where fuel and labor were abundant. Sweden’s forests provided the vast quantities of energy required for manufacturing, while its rivers powered the machinery.

But while the number of Swedish glassworks increased, foreign designs from industrial nations such as Germany and England still dominated Swedish glass in this period – there was no distinctive “Swedish” style.

At the 1914 Baltic Exhibition in Malmö, the Swedish glass displays were dated and uninspired compared to the avant-garde German and Danish exhibits. One group of artists, members of Svenska Slöjdföreningen (the Swedish Society of Craft and Design), criticized the exhibit and the “deadening” impact of industry on beauty. They advocated for “industrialized handicraft” and the integration of artists into the manufacturing process. Their plea was well received by the factory owners and in 1916 artists began working alongside glassblowers, cutters, and engravers.

Two artists were particularly crucial to the transformation of Swedish glass: Simon Gate and Edward Hald. Gate was a painter, trained in Stock-

holm at the National College of Art, Craft, and Design and at the Royal Swedish Academy Art School. Despite having never worked with glass, he was hired as artistic director of Orrefors in 1916. Gate’s aesthetic first manifested itself in detailed engraved patterns on glass and eventually in complex shapes in layered glass. A year later, Edward Hald, who was a former student of Henri Matisse in Paris, was hired. The two artists had different styles, but they both worked closely with craftsmen to merge art and manufacture, innovating forms and patterns. Within eight years, the new artists had brought Orrefors to international fame. The smaller glassworks in Sweden and across Scandinavia soon followed suit, until most Northern glassblowers were integrating artists into their production.

While the new artists, designers, and engravers won Sweden international acclaim with extravagant exhibition objects and expensive collections, they were also designing drinkware and other everyday objects for the masses. Based on the motto of activists such as Ellen Key, “beauty for all,” these items were successful exports. Soon, Orrefors had sales agents

across Europe, as well as in South Africa, Australia, and the US.

Ahead of the Stockholm Exhibition of 1930 artists like Edvin Palmkvist, Edvin Öhrström and Vicke Lindstrand innovated new colors and shapes. Using the techniques known as graal and ariel, layers of glass were applied on top of one another with air sealed in between. This allowed the glass to shine, with engraving and patterns inside.

Between the World Wars, Swedish glass went from a global unknown to becoming the greatest representation of Swedish modernism. Swedishdesigned glass became popular in

America through exhibitions in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco.

While glass exports completely ceased during the Second World War, Sweden’s avoidance of direct conflict saved the country from destruction and exports recovered quickly after the war.

However, new challenges soon emerged as copies of Swedish designs began to appear on the market, undercutting costs through manufacturing in countries with cheaper labor and materials. Glassworks had to choose: try to compete in the affordable household goods market, or specialize in the luxury, more artistic creations.

Swedish glassworks chose the latter.

Over time, most glassworks in Sweden closed and the industry consolidated. In the 1970s, glassworks Kosta, Boda, Åfors and Johansfors merged to form Kosta Boda. In 1990, Kosta Boda merged with Orrefors to form Orrefors & Kosta Boda.

Today, the company manufactures parts of its products at glassworks abroad and parts at the Kosta glassworks in Småland, where designers and glassblowers still work with grinders, painters, and glass cutters, to blend the bounds of what is possible, with that which is beautiful and familiar.

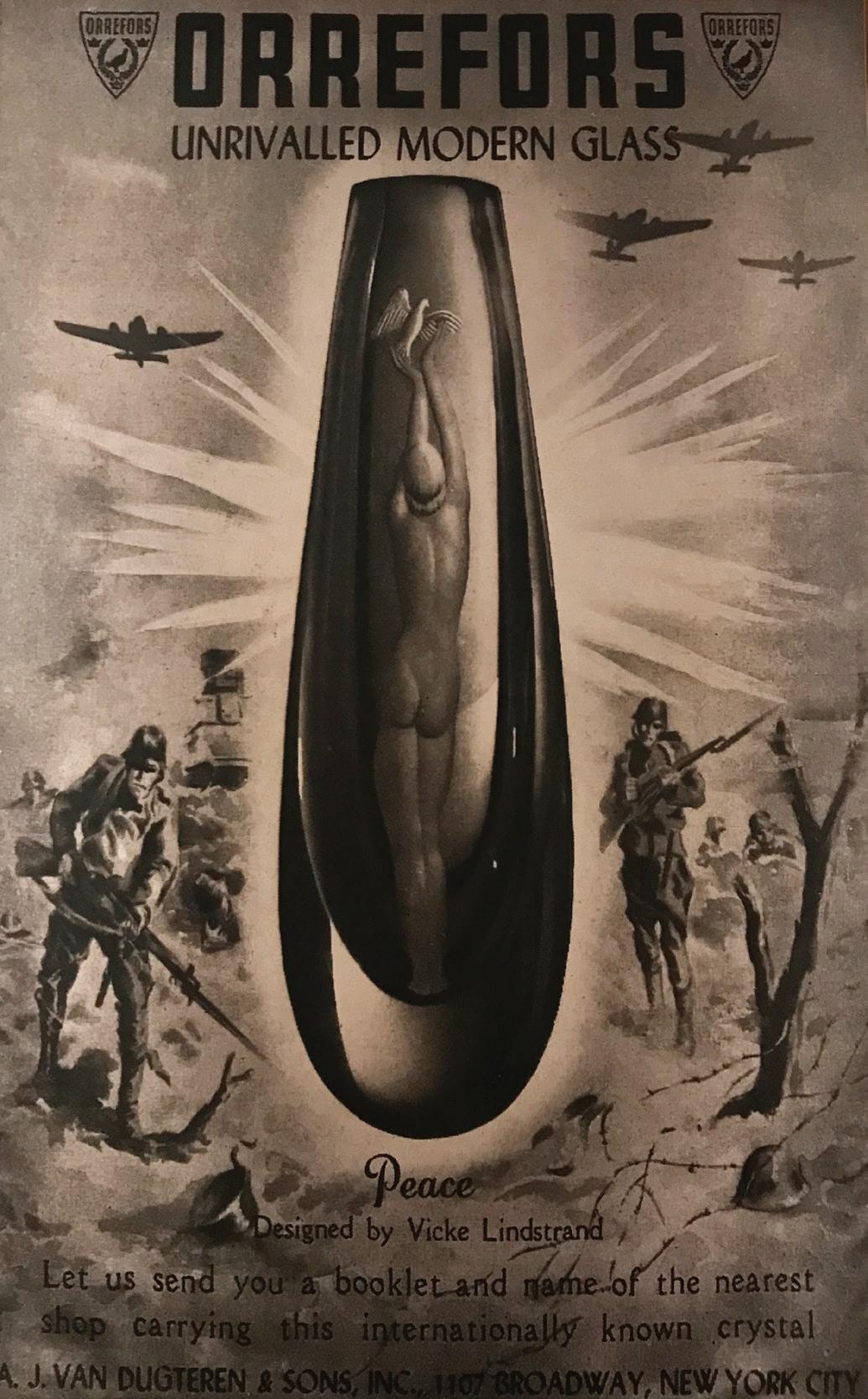

This ad, produced in 1944 by Nordiska Kompaniet (NK), features the “Shark Diver” vase, designed by Vicke Lindstrand. This Orrefors advertisement, produced between 1941 and 1945, features Lindstrand’s “Peace” vase surrounded by soldiers of World War II.Glasriket , or the Kingdom of Crystal, is a geographical area in the southern Swedish province of Småland, where glass has been blown by mouth since 1742. The region offers a plethora of unique glass-related experiences – including swimming and sleeping surrounded by glass.

By Kajsa NormanGlassworks was founded in 1742 and was the starting point of what would later become known as the Kingdom of Crystal. At the end of the 1800s, when Swedish glass production was at its height, more than half of the country’s 77 glass factories were situated in Småland. The province had ideal conditions for glassmaking with forests to fuel the ovens, streams to power the machinery, and lake sand to make the glass.

Today, only Kosta and a few other

Located a short distance from the glass furnaces of Kosta Glassworks is the Kosta Boda Art Gallery, designed in the early 1950s by modernist architect Bruno Mathsson. The gallery exhibits works from Sweden’s leading glass artists and since it is a gallery, not a museum, most of the art is for sale.

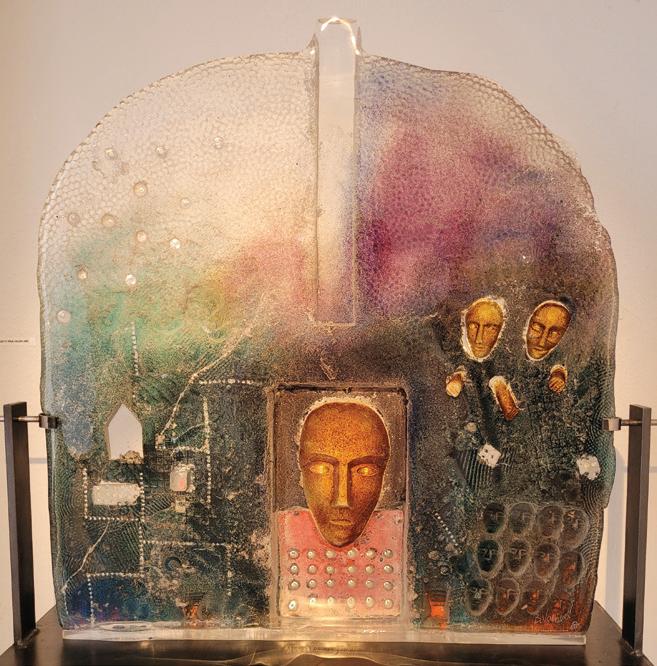

On the left, glass sculptures by Johan Röing. On the right, a piece by Bertil Vallien, one of Sweden's most celebrated glass artists.

Photos: Noelle Norman

glassworks remain, but there is a growing number of small blowing rooms and studios focusing on art glass.

In Kosta’s blowing room, visitors

can watch glassblowers in action as the hot liquid is transformed into beautiful pieces. You can also try blowing your own glass, but for this pre-booking is required.

Kosta Glasbruk

Kosta Glasbruk

KostaBoda Art Hotel is an awardwinning hotel featuring spectacular glass creations throughout the facility. However, most unique of all is

the spa where even the bottom of the pool features glass art. Make sure to pack your goggles so that you can take a closer look at the creations embedded at the bottom of the pool. Or, if

swimming is not for you, admire them from afar in the sauna.

If you’re staying elsewhere, or simply passing by, the spa is open for day visitors.

Boda Glass Bar features a 3.5-ton bar counter made entirely of cobalt blue glass and surrounded by other intricate glass creations. Kosta Boda designer Kjell Engman has created an environment meant to invoke the feeling of being underwater, replete with glass fish and a special glass ceiling reminiscent of how a diver perceives the surface of the water from below. Glass stalactites hanging from the ceiling resemble sunrays breaking the surface. You can enjoy a drink seated in a heated glass chair. The signature cocktail is “1742”, named after the year Kosta Glassworks first opened, and is served in a miniature glass oven.

Glass art at the bottom of the pool. Photo: Kosta Boda Art Hotel

Glass art at the bottom of the pool. Photo: Kosta Boda Art Hotel

Vallien is Sweden’s most famous glass artist and designer. Vallien studied pottery at the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm and the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. He began his career as a radical ceramic artist in New York City before returning to Sweden and the Kingdom of Crystal in 1963. He worked at Åfors Glassworks for many years before joining Kosta. This year, he celebrates his 60th year as an artist.

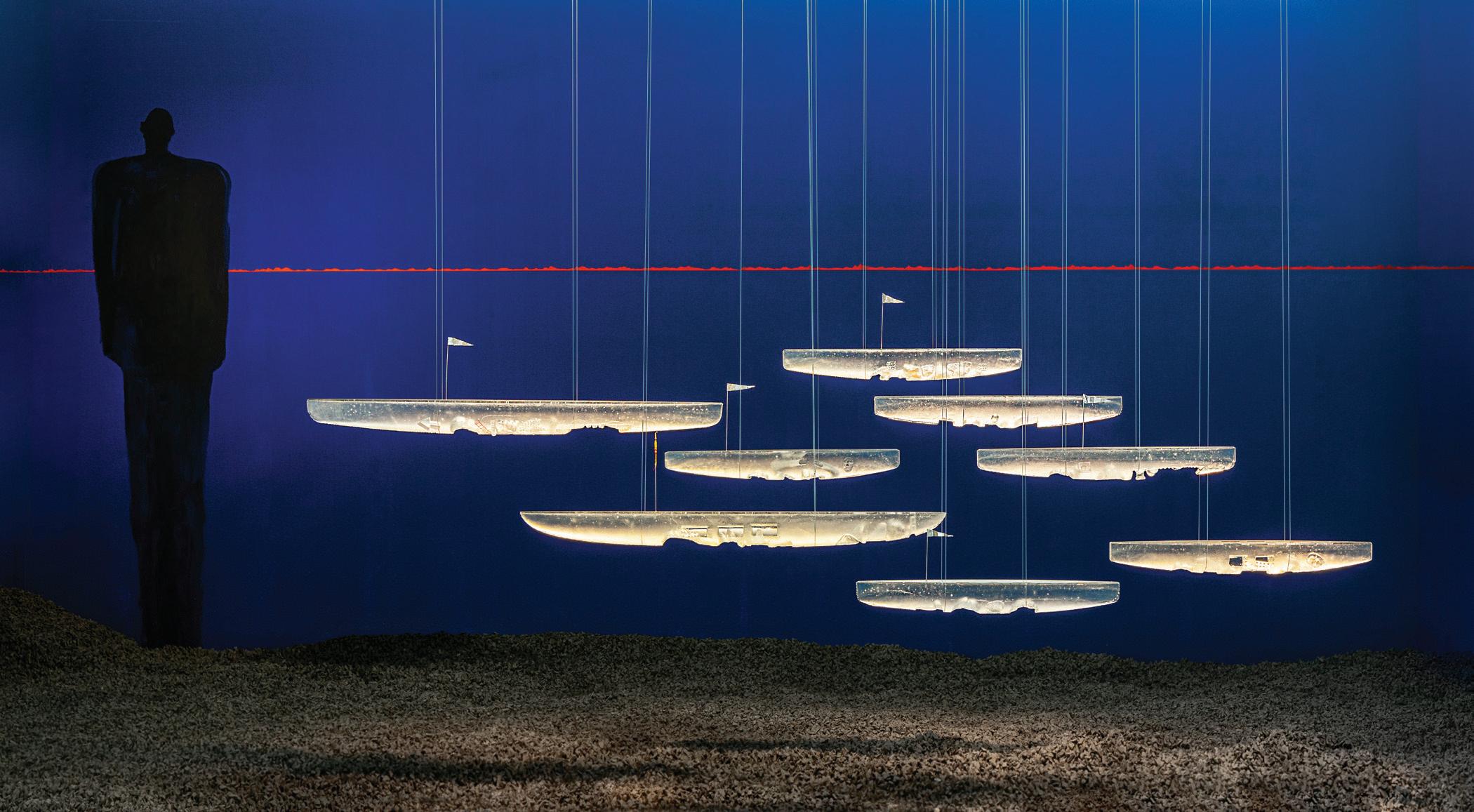

Vallien has won numerous awards for his work which is displayed in museums around the world. He is best known for his sand-cast sculptures and his glass ships.

“I make boats that sink. Sink

through memories and dreams. I make boats that don’t need latitudes. They navigate like glazed containers towards the horizons of the imagination. One container for Moses and one for the Viking chieftain. The traveler must trust in the thin skin that’s the only thing

separating her from the unknown.

Boats have always fascinated me, for the beautiful shape and for what they mean: livelihood, adventure, travel, birth, and death – a symbol that belongs to our collective consciousness.”

Bertil Vallien Entrance by Bertil Vallien. Boat Oracle by Bertil Vallien. Clear Water by Bertil Vallien.Ellen Ehk Åkesson and Markus Åkesson are an artist couple who live and work together in the forests of Småland, the region where they both grew up. The forest and its mystique inspire the work of both artists.

Ellen Ehk Åkesson is particularly fascinated by mushrooms – their supernatural beauty and strange life form as neither plant nor animal.

“Mushrooms are incredible,” she says. “We don’t know very much about them. Trees communicate through mushrooms, for example. And they have chemical, shamanistic, psychedelic properties that are being researched more and more.”

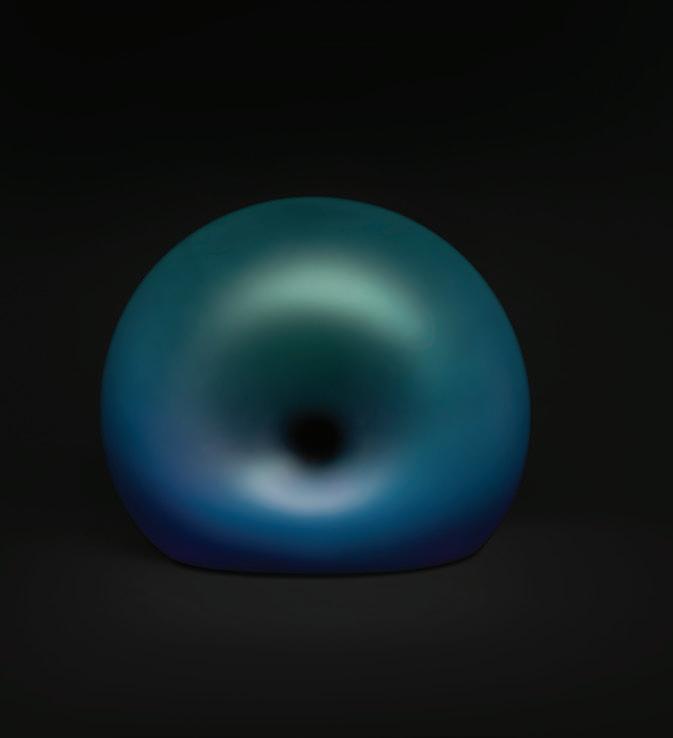

Primarily known for his oil paintings, Markus Åkesson is fairly new to glass, starting his work at the Kosta Glassworks as recently as 2021.

“I’m currently working with semiabstract shapes that are blown freehand, and after that, I work on the surface together with the cutters,” he says. “What makes glass such an interesting material, is that it is translucent and very fast. Compared to working in bronze and with oil painting, you need to make decisions quickly and work together. I love to work with others and the communication it requires. Many intuitive things happen all the time. That speed and communication bring an energy I really like.”

The Åkesson couple recently had a joint exhibition called The trailing moss and mystic glow at the Bruno Mathsson Hall in Kosta.

“We’ve both always been interested in spiritualism,” says Markus. “You don’t always have to seek out mystical and poetic things on the other side of the world; these things can be found nearby.”

Markus Åkesson and Ellen Ehk Åkesson together with Bertil Vallien at the exhibition The trailing moss and mystic glow.

Chesterfield glass by Markus Åkesson.

Wonderland by Ellen Ehk Åkesson.

Markus Åkesson and Ellen Ehk Åkesson together with Bertil Vallien at the exhibition The trailing moss and mystic glow.

Chesterfield glass by Markus Åkesson.

Wonderland by Ellen Ehk Åkesson.

Hope you enjoyed this sample of Swedish Press.

To read more, please click the link https://swedishpress.com/ subscription to subscribe.