2024

Architecture with fibre cement

Surfaces that change over time and are allowed to acquire a patina reflect a need for authenticity and closeness to nature. UNTREATED

2024

2 DOMINO

What are the alternatives to mass tourism?

Tina Gregoricˇ answers.

4 FLASHBACK

The Liesing employment office in Vienna by architect Ernst Anton Plischke

6 WHEN THINGS ARE ALLOWED TO CHANGE

In an interview, Thomas Will, Professor for Preservation of Historical Monuments, explains why the enthusiasm for patina is a modern phenomenon.

12 “KREATIVPAVILLON” IN BASLER WESTFELD

SCHEIBLER & VILLARD AND BAUMANN LUKAS ARCHITEKTUR

Vis-à-vis the old hospital building is a commercial building for companies from the creative sector. Its grey façade will attain a patina and become more and more integrated into the ensemble.

24 TRIPLE SPORTS HALL, ESCHENBACH ENZMANN FISCHER PARTNER

28 RESIDENTIAL COMPLEX, DÜBENDORF ADRIAN STREICH ARCHITEKTEN

30 SCHOOL CAMPUS BETHUSY, LAUSANNE ESPOSITO + JAVET ARCHITECTES ASSOCIÉS

34 SINGLE-FAMILY HOME, BIZAU BERNARDO BADER ARCHITEKTEN

36 GARDENER’S BUILDING IN ST. GALLER RHEINTAL EMI ARCHITEKT*INNEN

38 KNOW-HOW Solar façade in colour

40 DESIGN A raised garden bed to stack

42 AT THE START

Vidic Grohar Arhitekti from Ljubljana

Untreated

We find traces of time everywhere. In nature, in our faces, and in the built environment. Aging is a natural process, and those who want to prevent it have to go to great lengths.

When a wood façade turns grey, when moss forms on a roof or a bronze statue becomes green, these changes are called patina. An architecture that allows these changes appreciates the value of aging.

But how do we design architecture that permits change without deteriorating in the process?

“You can’t plan changes,” says the architect Maya Scheibler, who together with Sylvain Villard and Lukas Baumann clad a commercial pavilion in Westfeld in Basel in untreated fibre cement panels. The first changes can already be seen on the grey surface.

When fibre cement is not coated, it develops a whitish, hazy residue, similar to untreated, weathered concrete surfaces. This sign of lime deposits is called lime bloom or efflorescence. Porous surfaces of exposed concrete or untreated fibre cement panels also offer dirt, algae, and fungi a better chance of anchoring on their surfaces.

EMI Architekt*innenen clad their first work, a house for a gardener, with untreated fibre cement panels more than fifteen years ago. Ron Edelaar from EMI says, it is also a question of attitude, whether a house is allowed to change through external influences, and thereby make use, weathering, and time visible.

All the projects in this issue are clad with untreated fibre cement panels. In the more recent projects, the changes are not so far advanced yet. Older projects, on the other hand, show the potential of this building method and serve as models for a current generation of architects.

Hope you enjoy this issue,

Anne Isopp Editor-in-chief

EDITORIAL

WHAT ALTERNATIVES ARE THERE

Three ideas from the Architectural Association’s Nanotourism Visiting School in London: in the French seaside resort Ault, chairs are placed in the water so that people can enter into conversation (Chaises Publiques, 2017). A dedicated market stall (1M2 Market, 2020) in Vienna explores the possibilities of the legally prescribed regulations, and a public jetty in Sekirn (Stare, 2021) counters the excess of fenced-in lakeside properties on Lake Wörthersee.

– We ask a personality from the world of architecture and design a question that moves our society. The Slovenian architect and architecture professor Tina Gregorič answered our question:

TO MASS TOURISM?

For the start, let’s deliberately replace the term “mass-tourism” with “over-tourism” as often as possible and consistently in all media, when addressing the current environmental, social, and economic tourism realities either in the Alps, in the Mediterranean or in other places worldwide.

Over-tourism has been recently acknowledged by the WTO as the impact of tourism that endangers the quality of life of the residents and the quality of visitors’ experiences. Therefore, it’s essential to address over-tourism for the benefit of everyone involved, including the environment.

Being based in Slovenia, with all the natural, climatic, and cultural diversity, we witness mass tourism turning into over-tourism, first on the Adriatic coast, then in the scenic Alpine passes, and recently even in our capital – Ljubljana. In addition, researching the destiny of Venice was the most apparent milestone that called for radical alternatives.

Together with Aljosa Dekleva, we coined the term ‘nanotourism’ in 2013 as a possible participatory, locally oriented, sustainable alternative to conventional tourism. Nanotourism draws inspiration from long-existing responsible tourism models like agriturismo, where locals and visitors connect and exchange to benefit the environment and local economy, engage in food production, and boost social relations. By referring to these existing or novel participatory, sustainable models as nanotourism, we encourage them to become more prevalent. This way, we can make these practices the norm rather than the exception, as Buckminster Fuller suggested: “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

To address the passiveness and superficiality of conventional tourism, we expose participatory as the vital characteristic of nanotourism: immersed co-creation and exchange between visitors and the local community

is intrinsic to apple harvesting or a stone drywall workshop.

A viable alternative to over-tourism is primarily twofold: offering predominately participatory and responsible models of tourist experiences while limiting transportation to and from the destination.

Alpine towns like Hallstatt, Austria face over-tourism due to transportation challenges. To avoid being overwhelmed by tourists, these towns can limit traffic by adopting the approach of islands where the port’s capacity determines traffic density. Such a strategy can regulate the number of visitors, reduce environmental impact, and preserve the town’s uniqueness.

In summer, the Alps could become a profoundly curated territory, similar to the Art Islands in Japan, where visitors need to book their visit months ahead and plan transportation to and from the islands carefully. The regulation of visitor density is critical for a unique, intense, and memorable experience.

The recent introduction of an entry ticket to Venice resembles the implementation of the entry ticket to the Louvre in 1922. A visitor density regulation was needed after more than a century of free entry.

After transforming over-tourism into a new creative, participatory, bottom-up alternative such as nanotourism together with density control, we can visualize the unique alpine landscapes, although clearly altered by climate change, with devoted visitors – nanotourists who not only prearrange their entry tickets in particular time slot but are also exciting to engage in local activities that help and not devastate the local culture or nature, while boosting the local economy.

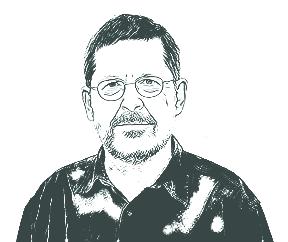

Tina Gregorič is Professor of Architecture and Design at the TU Vienna and runs the architectural office dekleva gregorič architects in Ljubljana together with Aljosa Dekleva. Together they have initiated design research on nanotourism, while Aljosa heads the AA Nanotourism Visiting School.

www.dekleva-gregoric.com nanotourism.org

3

DOMINO

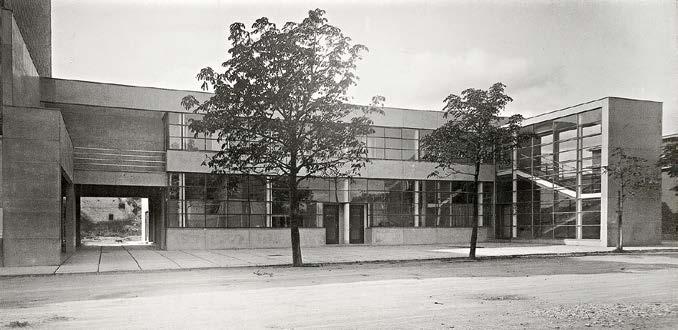

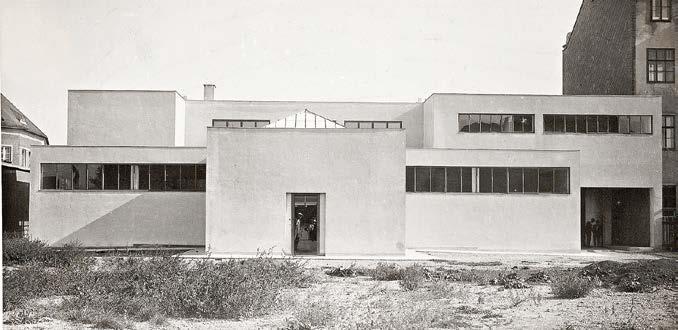

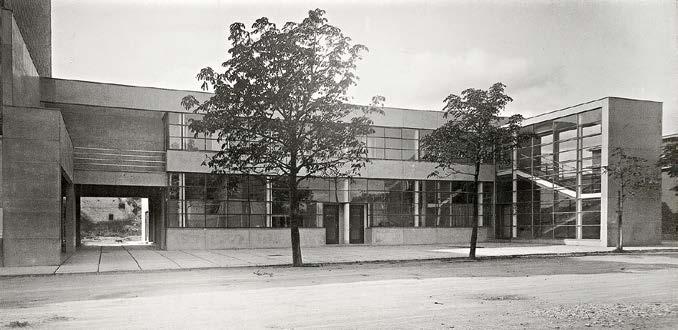

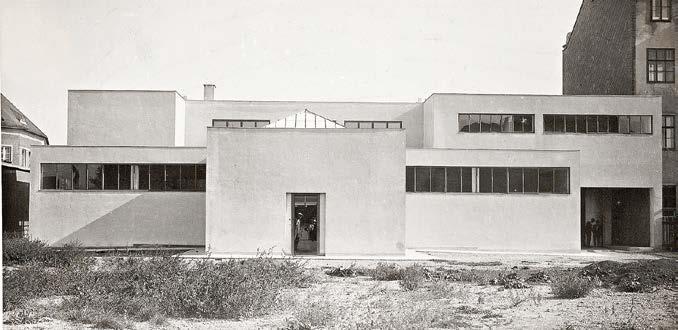

FLASHBACK – The Liesing employment office in Vienna is considered an icon of international modernism in Austria. It was built by the architect Ernst Anton Plischke in 1930/31 and restored by Hermann Czech in the late 1990s. In the course of this, the fibre cement façade was renewed, too, however, visually, it cannot be distinguished from the original state.

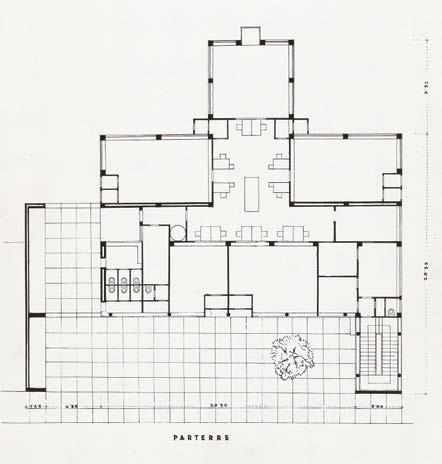

With the economic crisis of the interwar period, socio-politically engaged modern architecture focused on a new building task. The Liesing employment office in Vienna— the first major commission for the architect Ernst Anton Plischke, who was twenty-eight years old at the time—is one of the functionally most convincing examples of this type alongside the employment office in Dessau designed by Walter Gropius (1928/29).

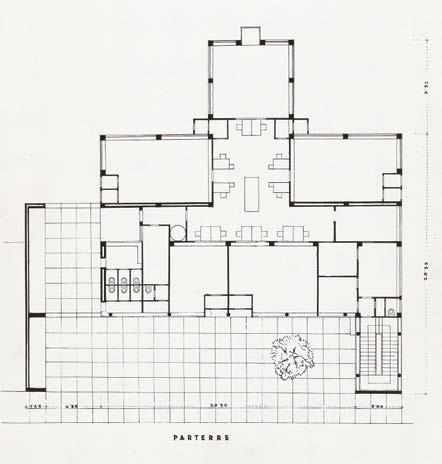

Plischke solved the demand for the smoothest possible flow of public traffic, separated according to occupations and genders, with an ingenious ground plan concept that spared job seekers the usual stuffy, poorly lit, and overcrowded waiting rooms. In a varia -

tion of Gropius’s circular concept, he grouped a ring of five waiting rooms, each of which could be entered directly and separately from outside, around a central top-lit counter hall. The encounter between (seated) civil servants and (standing) clients was brought to eye level through a slight difference in level and regulated via counters with sliding windows.

Plischke broke up the solitary structure, which was at the same time, integrated into the context, with ribbon windows on the street side, and for the façade cladding envisaged grey, fibre cement panels—a very modern and inexpensive material that was still quite new at the time.

Photos of the street side gave the building instant fame: the black-and-white shots staged the glass prism of the protruding stairway, but concealed the subtle material and colour harmony between the delicate, blue profiles of the single glazing and the grey tone of the fibre cement. Nevertheless, they later proved helpful in restoring the building to its original state as the subsequent political upheavals also took their toll. The reinforced concrete skeleton structure lost its transparency during the Nazi era through alterations that deliberately counteracted it; while further disfiguring measures followed in the postwar years. In 1980, the building was finally closed down as an em-

PERFECTLY ORGANIZED

This is how the street and courtyard sides of the Liesing employment office in Vienna looked in the 1930s.

4 ARCH 2024

ployment office, and after remaining vacant for quite some time, was purchased by a housing association on the premise of renovating it in accordance with its status as a landmarked building.

The architect commissioned with the restoration, Hermann Czech, proceeded rationally and methodically, just like his teacher— E. A. Plischke—before him. He removed all later additions and once again exposed the concrete skeleton, which was still structurally sound. He converted the former waiting rooms on the ground level into offices, while the upper floor was converted into apartments. Additional windows and patio doors are clearly different than the original in format and colouring. Czech used the photographs from the construction period to refine his ideas on the reconstruction of the muntin profiles of the ribbon windows, which were made in part from industrial products that were no longer manufactured. Czech therefore deliberately used standard industrial products from the 1990s rather than “sculpturally” duplicating the original. For the fibre cement panels on the street façade, this problem did not come up. “This building material is still available today— even in better quality,” Czech explained. While on the garden side, the hollow sound of full thermal insulation could not be avoided, the street-side fibre cement façade corresponds with both today’s standards and the original concept.

Meanwhile, it has been a quarter of a century since the Liesing employment office was restored and converted into an office and residential building. The traces left behind by wind and weather on the “timeless” fibre cement façade do not detract from its appearance. Unfortunately, the staggered rear façade of the building, which was previously freely visible, has been massively encroached upon by more recent residential buildings. Keeping the space free without a purpose doesn’t seem to fit into an era in which usable land has become such a precious commodity.

Gabriele Kaiser

Back then as well as today, the protruding staircase is the building’s characteristic element. In front of the building an expanded public space arises through the recessed main body.

5

When things are allowed to change

6 ARCH 2024 UNTREATED

Inauguration of the Meret Oppenheim Fountain, Berne, 1983

Everything doesn’t always have to look as though it were new. Nowadays, this applies to more than just fashion and furniture; also architecture is allowed to visibly age and change. In an interview, Thomas Will, architect and professor emeritus of monument conservation at the TU Dresden, explains why patina is a hot topic, and at the same time, an enigmatic and ambivalent concept.

In 1983, a lot of residents of the city of Bern must have asked, “Is that art, or can it be removed?” The artist Meret Oppenheimer had designed a new fountain in the center of the old town. The discussions surrounding the work of art now known as the Oppenheim fountain were heated. The massive cylindrical column with an arcade-like end and spirally arranged sheet metal seemed raw and forbidding. Over time, plants and moss grew on the surfaces. Because of the calcareous water, lime tufa formed in the cushions of moss. The appearance of the fountain changed considerably over the years and with it, the opinion of the population. The fountain has long since become an integral part of Bern and “blends naturally into the cityscape,” as the artist intended.

The signs of time are visible elsewhere, too: wood turns grey, moss and lichen grow on tiled or fibre cement roofs and on exterior concrete walls.

Even when these traces of aging have absolutely no influence on the durability of the object, not everyone finds them beautiful, and not everything becomes more

What image do you have in mind when we talk about patina?

Patina refers to an aesthetic appearance, a trace of age on buildings or artworks that gives us pleasure. Originally, it referred to the greenish coating from oxidation on copper and bronze. The word patina comes from Italian, where it means “varnish,” derived from the Latin word for “a shallow dish,” in which such a coating was originally maintained. Patina shows that something is older, more mature in a sense. Nowadays, we associate certain feelings with such signs of age, which was not always the case in earlier eras. Our appreciative use of the term is a modern phenomenon.

Does patina have a more positive connotation today because it is associated with the desire for something natural? Would you say that?

Entirely. We use the term patina to describe an aesthetic aspect, a layer that makes an object appear “beautifully” aged in a natural way, and what is interesting, by the way, is that it is also a sign of history. Nonetheless, these signs of age have to be moderate. There is a fine line where it turns to neglect, to destruction. Especially in the case of buildings, the two can easily merge. In Italy, for example, when we see plastered surfaces that have cracked and show various patches and layers of paint, this can also be perceived as a kind of patina. In the case of a single building, however, you would be more likely to say that it needs to be renovated. In this respect, patina is an enigmatic term for which we have no precise technical description, one that is involved with our visual habits and emotions.

beautiful over time. So the interesting question is: when do we appreciate that something is visibly aging, and when do we want to prevent this? In the Handbuch Historische Authentizität (Handbook of Historical Authenticity), Oliver Mack explains why not all changes are accepted equally: “The term patina describes visible changes that are evoked through the use and age of an object and which, at the same time, are given—in contrast to the rather negatively connoted term of wear and tear—a changing, often even enriching meaning.”

In order to understand why patina has become a hot topic in contemporary architecture again, and where the enthusiasm for it comes from, we talked with Thomas Will, architect and professor emeritus of monument conservation at the TU Dresden.

Text and interview: Anne Isopp

Regardless of whether bronze, sheet metal, wood, or concrete: all materials attain a beautiful patina. The sculptures are in the open-air storage of the Middelheim Museum in Antwerpen.

The only one who knows the location of this barn is the photographer Georg Aerni. The St. Benedikt Chapel by Peter Zumthor and the Wotruba Church in Vienna, on the other hand, are quite well known.

8 ARCH 2024 UNTREATED

You have a professional view of the subject. As a conservationist, how do you assess whether a building has a patina?

I mentioned earlier that the enthusiasm for patina is a modern phenomenon. Not as a genuinely modern value, but instead, as a counter current: a type of compensation for the loss of familiar, that is, aged surfaces. In the Romantic period, which marks the beginning of modern perception, there was a new interest in traces of aging, fragments, and ruins. These manifestations of the sublime (and noble) were not considered directly beautiful, but attractive and interesting. Then, when industrialization gave rise to new types of objects and surfaces in large quantities, people sought to com-

pensate for the new, smooth, and perfect—the core themes of modernism—through a “romantic” preference for aged surfaces and forms. In light of the perceived loss of the familiar, traces of age took on a new meaning. In the Middle Ages, people tended to be pleased when something looked new—because new things were not created very quickly or in large quantities.

In one of my seminars, I did an exercise with the students: when they left their houses in the morning, they were meant look around and notice how many buildings were younger than them. Depending on where you live, there are quite a few. Due to our enormous building production, we are surrounded by newer structures, except in the landmarked city centres. In premodern times, the opposite was the case. From the nineteenth century onward, people began to see aged buildings and cities in a new light, and appreciate them. The romanticism of ruins is an extreme example, but so-called antiques are also part of this, as are monuments in general, because they bear witness to

9 UNTREATED

a different era. This also includes what the surfaces show us—an aesthetically perceived message. They say that something has aged and in doing so, it has also transformed. In this respect, the image of aging also goes hand in hand with that of naturalness. The artificial is initially new and shiny, and modern materials also age in a less natural way.

We don’t use the word patina with reference to living beings, but here, too, are corresponding sentiments: the search for eternal youth, the obsession with beauty as a modern counterpart to the reverence of old age, which appears again and again in art. Dürer’s painting of his mother comes to mind. The fact that old age can also be beautiful is not really in vogue nowadays— other than those gentle, aesthetically appealing and technically mostly harmless traces of age that we call patina.

When is something worth preserving and when not? As a conservationist, you must have to ask yourself this question time and again. Monument conservation has undergone a major change in this respect: from perfectly restored objects, made to look new based on ideal images, to recognition of their value as historical evidence, and according to Georg Dehio, of the perception-psychology-based “value of aging.” The latter is a momentous, radically modern observation by the Viennese art historian and general curator Alois Riegl from the early twentieth century. Ever since, monument conservation has sought to preserve traces of age wherever possible. Its mission is to preserve a heritage, not to create a new one. Therefore, the statement, “The town hall shines in its former glory,” which was still used in the 1960s, and which we often come across in the news-

10 ARCH 2024

Buildings with patina, such as the home of André Studer, built in Gockhausen in 1959 (left), or the Ricola Warehouse in Laufen by Herzog & de Meuron serve as role models for architects today.

paper, is unpopular among monument conservationists. It would be a new glory, and that is precisely the opposite of patina.

Of course, I wouldn’t categorically reject that. We know that entire city neighbourhoods can make a woeful impression. Sooner or later, they will have to be renovated and also freshened up aesthetically because otherwise they’d be difficult to maintain.

In this respect, patina is ambivalent and the question is: where is the limit? Where do I have to renew something and where can I say those are, after all, beautiful and valuable traces of aging? No one would think of removing the traces on a column in Pompei on which Napoleon had scribbled. There, everyone knows that it is a valuable piece of evidence. But when it comes to more recent buildings, people often consider them rundown and neglected, especially the oftentimes plain buildings of the post-war era. In these cases, the patina loses out, and rightly so at times. A world full of painstakingly preserved signs of age would be contrived, museum-like. For this reason, patinated surfaces are particularly attractive in places where we see them as tourists or art lovers. A 300 -year-old moss covered house in the Swiss Alps is impressive, an experience. But your own house shouldn’t look so aged. That’s what I mean with ambivalence.

Currently, there is a trend in architecture for architects to deliberately choose materials that will attain a patina. They no longer want a building to always look as though it were new. But not everyone likes a façade with patina. It is truly ambivalent, as you say. The more recent shift towards an appearance that consciously allows for the material to age and change is also related to the sustainability debate. It seems to me that it’s an aesthetic-artistic reaction to hypermodernity, to an architecture that comes from the factory and tolerates absolutely no signs of aging. Incidentally, this was already an important topic for the avant-garde more than a hundred years ago—and Vienna played a major role in this. From the turn of the nineteenth to twentieth centuries, there was a strong rejection of historical forms and styles that appeared outdated and used up. As a contrast to these forms of expression of the old order and ways of life, people were practically euphoric in their invocation of the upcoming, the new. Adolf Loos in Vienna and later Le Corbusier in Paris were especially eloquent and effective proponents of the utopia of the new and pure. Le Corbusier wrote that people should no longer hang pictures on the walls because this would only burden them, and recommended the pure, white wall as a modern cleansing of false memories. Thus, at the roots of modernism we find the rejection of traces of aging and patina as an aesthetic reaction to oversaturated historicism and the old orders associated with it. Looking now at our contemporary architectural production, we also see reactions to such external conditions, at least among the more ambitious works—only they are entirely different. We don’t need more and more new things, but instead, a sensitive way of dealing with the enormous amount of existing buildings. In this logic, the traces of aging and, mainly, the ability to age and acceptance of the signs of aging become very important. To this extent, patina is also an issue of sustainability.

Thomas Will is an architect and professor emeritus of monument conservation at the TU Dresden. His book Die Kunst des Bewahrens (The art of conservation) is also relevant to this topic.

11 UNTREATED

Undergoing Change

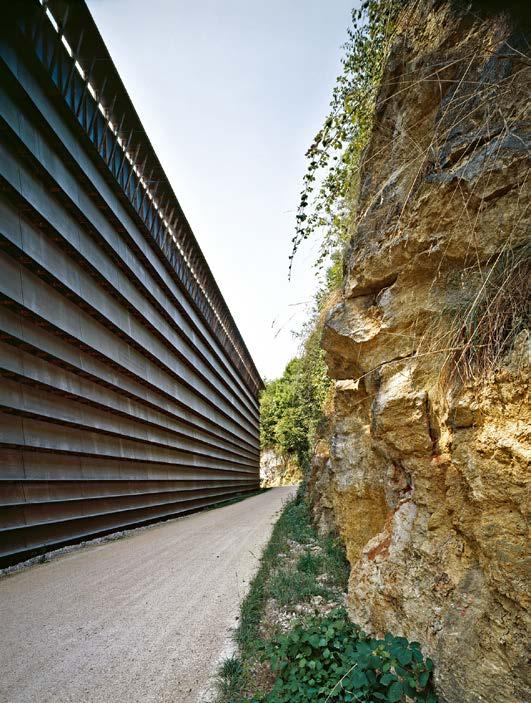

A new, mixed residential quarter has formed on the site of the former Felix Platter Hospital in the west of Basel. Located directly on the main square, vis-à-vis the old hospital building, is the “Kreativpavillon,” a commercial building for companies from the creative sector. With its grey façade, and the patina that will form on its surfaces over time, it blends in well with the ensemble and mediates between the new residential buildings and the existing listed hospital.

Text: Anne Isopp, photos: Niklaus Spoerri, Boris Haberthür

12 ARCH 2024 UNTREATED

The Felix Platter Hospital is Basel’s second largest hospital. It is located in the west of the city, specializes in geriatric medicine, and for a long time, was housed in a typical building from the 1960s. The high-rise designed by Fritz Rickenbacher and Walter Baumann is particularly striking due to its structured façade of concrete grids. While the new hospital building was being built on a neighbouring plot, redevelopment of the site began, and plans were made to demolish the old hospital.

Thanks to numerous protests, the building is still standing today, and is meanwhile a listed building. The building cooperative Wohnen und Mehr purchased the 36,000square-metre plot, including the old hospital, in building lease, and developed it together with other building cooperatives. The old hospital was converted into apartments by Müller Sigrist and Rapp Architekten. Today, the building is the grande dame of the new quarter. In the urban-planning design, which was won by Enzmann Fischer Partner, the old and new hospitals are juxtaposed with another heavy weight: an elongated, eight-storey perimeter block, a common ty-

pology for Basel. This perimeter block development was subdivided into individual components and developed by several architectural firms, which all had to comply with a uniform appearance.

LeNa House was designed by architects Maya Scheibler and Sylvain Villard with Baumann Lukas. LeNa is the abbreviation for “Lebenswerte Nachbarschaft” or livable neighbourhood. The roughly 180 residents are interested in a communal and sustainable lifestyle, and the apartments, which are smaller than usual, have only a minimal kitchen area. Instead, all residents have access to a food depot, a canteen, and a communal kitchen on the ground floor.

The façade is clad with red, corrugated fibre cement panels. Red was a specification from Enzmann Fischer. The architects chose corrugated fibre cement panels as they wanted to generate depth in the façade, and the shadows that are cast supported their desire for a relief.

Scheibler & Villard and Baumann Lukas Architektur also designed two of the three other pavilion-like commercial buildings, which line the car-free “Forum” through the

14 ARCH 2024

The old hospital sits enthroned like a grande dame over Basel’s new Westfeld quarter.

quarter. The middle building is the headquarters of Pro Senectute beider Basel, an organization that offers services for senior citizens and works closely with the hospital.

The pavilion located at the end of the path is the so-called Kreativpavillon. It is located directly on the new quarter’s main square across from the old hospital and assumes a special position among the commercial pavilions.

With it, the client wanted to provide companies and start-ups from the creative sector moderately priced commercial spaces for rent. The architects developed a reinforced concrete skeleton that offers great flexibility of use, and allows tenants the chance to finish their interiors themselves. A spacious meeting zone runs through the middle of the building, like a lung, and promotes synergies between the tenants, even across branches. The architects placed the central access in front of the building. A spiral stairway made of galvanized steel located at the rear, longi-

tudinal side beautifully complements the grey façade, and here is where creative life is now centred. Only the elevator is located inside the building.

The architects and client looked for a façade material that would be suitable for the creative interior. They chose untreated fibre cement panels, which would attain a patina. In this way, the pavilion will blend in ever more with the ensemble over time and form a bridge between old and new.

Wide, all-round ribbon windows make the division into floors visible on the façade.

The building has a closed appearance only towards the square; here, the middle floor has no windows, only wall surfaces clad with fibre cement panels.

All façade panels are inclined, slightly more in the area of the ceilings of each floor, and even protrude like awnings over the ground level. For the montage of the panels, centreboards of galvanized steel were produced, on which the fibre cement panels were as-

sembled according to the respective angle of inclination. Through different inclinations of the panels, the patina will develop at different speeds and to different degrees.

Referring to the change, Maya Scheibler says: “The material will blend into the site over time and make the traces of time visible.” Even now, the panels are no longer a uniform grey. Every panel ages differently. This gives the building the look that the architects and client aspired to for the Kreativpavillon.

15 UNTREATED

So that its creative use can be read from outside, the architects clad the pavilion with a façade of untreated fibre cement panels.

Inside is a simple, flexible building structure that allows tenants to finish their own interiors.

17 UNTREATED

Vertical section 1:20

1 fibre cement panel, 12 mm

2 composite layer

3 drainage gutter, raw aluminium

4 rear ventilation, T-section, galvanized steel

5 window gutter, raw aluminium

6 chipboard panel

7 vapour barrier

8 insulation, mineral wool

9 gypsum fibreboard

10 wind seal

Kreativpavillon Westfeld

Location: Im Westfeld 8 , Basel /CH

Client: Baugenossenschaft Wohnen und Mehr, Basel /CH

Architecture: ARGE Baumann Scheibler Villard: Baumann

Lukas Architektur, Basel; Scheibler & Villard, Basel

Completion: 2022

Façade construction: Neba Therma AG, Zofingen /CH

Façade material:Swisspearl Largo, Purio Classic Grey

18 ARCH 2024 UNTREATED

1:20 Westfeld 12 mm roh feuerverzinkt 7 8 3 4 2 5 6 1 10 1 9 2 3 4 8

Vertikalschnitt

Urban planning model with the winning design by Enzmann Fischer Partner.

The buildings 1 to 3 are planned by the ARGE Baumann Scheibler Villard:

1 LeNa House

2 + 3 commercial pavilions

4 old hospital (converted into apartments by Müller Sigrist Architekten)

5 new Felix Platter Hospital building (Wörner Traxler Richter with Holzer Kobler Architekturen)

19 UNTREATED

B ä ground floor 1:400 first floor second floor 1 2 3 4 5

“We want the building to be allowed to change”

For ARCH, Anne Isopp spoke with the architect Maya Scheibler from Scheibler & Villard.

You designed a residential building and two commercial buildings in Westfeld, the new quarter in Basel. Which one came first?

We started with the residential building for the housing cooperative LeNa, Lebenswerte Nachbarschaft (Livable neighbourhood). The pavilions came later, as a direct commission. But they were always part of Enzmann Fischer’s masterplan.

The residential building is clad with red, corrugated, fibre cement panels, the Kreativpavillon with grey fibre cement. Why did you choose different materials for the façades?

The colour red for the block perimeter development is part of a larger urbanplanning idea and was one of Enzmann Fischer’s specification. We then tested various fibre cement panels and decided on the corrugated panel. We wanted a relief for the façade, a tectonic articulation, and the shadows that the corrugation creates support this idea.

On the other hand, the two pavilions are very different. In one, the program was very clear. It holds the offices of Pro Senectute beider Basel, an organization offering services for senior citizens. In the other pavilion, the client Wohnen und Mehr (living and more) offers low-rent office spaces to enterprises and start-ups from the creative industries. For this, we

developed a building structure that can be used flexibly, which also allows clients to finish the interiors themselves. In the middle of the building is a meeting zone for creating synergies across branches.

The Kreativpavillon is located directly on the new quarter’s main square. It has a central position and an entirely different appearance. How did this come about?

For this building, we were looking for an industrial aura. People from the creative industries work here. And then there is the strong counterpart, the former Felix Platter hospital with its concrete façade and grid elements. We also wanted to respond to this with our design, colour scheme, and

the rhythm of the façade. We were also greatly influenced by role models. The Voellmy AG joinery building and the Ricola Laufen warehouse by Herzog de & Meuron have exactly the expression we wanted for this pavilion.

You chose fibre cement panels that are untreated. A material that over the course of time, will acquire a patina. Why?

We could have also chosen wood. The wood would have then turned more and more grey over time. But the untreated wood would not have fit in with the old hospital, this stone world. Fibre cement comes much closer to what we were looking for.

20 ARCH 2024 UNTREATED

How do you want the surface, and thus the appearance of the pavilion, to change over time? What would you like?

You can’t plan changes. Over time, the material should blend into the site and make the traces of time visible. We want the building to be allowed to change without falling apart. It shouldn’t deteriorate, but instead, simply be able to move with the times. Like we do, as people.

When you stand on site now, you can see how naturally the panels blend into the surroundings. What is your impression?

Maya Scheibler and Sylvain Villard founded their joint architectural practice in 2012. Together they teach the second-year course at the University of Applied Sciences Northwestern Switzerland, with a focus on residential construction. The buildings in Westfeld were created in collaboration with Lukas Baumann (right).

The change still needs time. In my opinion, it’s good that it’s changing slowly. I think that if it were to happen faster, people would think it was a mistake. This gradual change is exactly what we were looking for.

To what extent do such materials support your architectural language? The pavilion was special in that there was no ready-made commission, but instead, we worked together with the client towards a vision.

Normally, the client comes with a wish, or we have won a competition with an explicit program. The fact that the design was able to develop through dialogue

Below, two projects by Scheibler & Villard: conversion of a historically protected building in Basel and new construction and conversion of a home for the deaf-blind in Langnau am Albis.

Right: two projects by Baumann Lukas Architektur: renovation of the Theater Basel and renovation of a historic wooden house in Andermatt.

here, was a challenge, but also very beautiful.

When it comes to architectural expression, we always respond in a very specific way to the details of a location and the use. That’s why here, we didn’t proceed any differently than with other buildings.

21 UNTREATED

Enzmann Fischer Partner

Proud and Pragmatic

In Eschenbach, Enzmann Fischer Partner are expanding a multipurpose building from the 1980s with a triple sports hall. So that old and new align over time, also the new façades are clad with untreated fibre cement panels.

Text: Martin Tschanz, photos: Edon Miseri, Philip Heckhausen

25 UNTREATED

Expansion of the Eschenbach Sports Complex

The village meeting place in Eschenbach is a rough beauty. The multipurpose hall from the 1980s is part of a group of public buildings that mark the entrance to the village. In addition to the school and a nursing home are also a barracks and a maintenance depot, which are located in front of the hall on the road. Additionally, on the ground level below the hall is a fire station, so that the adjacent park and fairgrounds can be used for different purposes. This is a pragmatic solution, but also a proud one. This raised position emphasizes the size of the village meeting place, in keeping with its importance as a venue for community gatherings and significant cultural events.

The new building, which now complements these facilities with a triple sports hall, makes use of its unique features. It embraces the existing building in such a way that old and new can be used separately, but also together. The new halls adjoin the existing building to the west, whereby a new spatial level links the existing hall and the visitor gallery of the new sports hall.

Also the entrance hall and foyer above it, serve both parts. This opens new possibilities for village life, as large events, such as Mardi Gras and local trade fairs, now have a generous and differentiated space. The old hall with its wooden dress and large stage is a traditional festival hall, the new part with its visitors’ gallery, is a sports arena, but also an event venue for large celebrations. It goes without saying that school sports and clubs use all the spaces on a daily basis, and the military still cooks in the existing canteen kitchen when the corresponding accommodation is occupied.

The new wing takes up and reinterprets the theme of the roofs of the existing buildings. Flat, sloping timber element ceilings over powerful concrete beams give rhythm to the hall and lend the building its own entirely unique expression. The materiality of the façades also echoes that of the existing building. Grey, untreated fibre cement panels and tumbled concrete are supplemented and finished with sheet metal work and ventilation panels of raw aluminium. In this way, a silvery shimmer contrasts with the matte grey of the cement-bonded

materials, whose porous surfaces show the signs of aging. Especially in wet weather, it is already possible to imagine how the new parts will blend in with the existing building. Over the years, this dress of natural grey fibre cement shingles has acquired a dark, dynamic patina, especially on the north side, which fits in well with the unique character of this rural setting.

Martin Tschanz

Location: Rapperswilerstrasse 18 , 8733 Eschenbach /CH

Client: Town of Eschenbach

Architecture: Enzmann Fischer Partner AG, Zürich /CH

Completion: 2022

Façade construction: Hüppi Dachbau AG, Goldingen /CH

Façade material: Ondapress- 57, natural grey

26 ARCH 2024

UNTREATED

A triple sports hall is added to the existing facility. This embraces the existing building in such a way that the old and new can be used separately, but also together.

ground floor 1:1000

first floor

27

ground floor 1:1000

28 ARCH 2024

The four-storey residential complex in Dübendorf impresses with its matte grey, rust red colouring, which offers a beautiful contrast to the green of the garden.

Adrian Streich Architekten Residential Complex Alte Gfennstrasse

Dübendorf, today a town with more than 30,000 inhabitants, is located eight kilometres east of Zurich’s city centre and has long benefited from its proximity to the metropolis. Because Dübendorf is directly adjacent to Zurich and can be reached with the commuter rail in just a few minutes, the town has experienced a steady growth in population. Skyscrapers rise up high near the Stettbach railway station on the city limits. This is why Dübendorf sometimes is also referred to as “Dübai.”

The pressure to densify is also shown further east where the small Glatt river flows through the municipal area. Standing on its banks are still relatively small buildings, while along the Alte Gfennstrasse, the road running somewhat higher above it, large-scale volumes testify to the increasing densification within the municipality. The most recent example of this is the building project that the Zurich architect Adrian Streich realized between 2017 and 2022 for the Swiss Re pension fund. Parallel to Claridenstrasse, which branches off from Alten Gfennstrasse, a compact development was created, which reveals a fourstorey row with loft extensions divided into three buildings. Because the street slopes slightly to the south, the buildings are stepped towards each other. Thanks to

the orientation to the street and an underground garage on the second basement level, it was possible to keep the rest of the plot free of buildings and basements, so that even deep-rooted trees can grow in the garden.

The standard floors in the buildings, which are identical in construction, were organized as four-floor blocks. The side apartments are inserted through the volumes, while the middle ones are oriented towards the garden, where projections sculpturally subdivide the rear façade. The two apartments at each loft level are furnished with terraces rather than balconies.

Floor-high, relatively narrow and foot graded fibre cement panels, that is, mounted with the reverse side facing outward, and a rough surface, characterize the façades on all sides and on all floors. Grey was chosen as a neutral contrast to the rust red of the metal strips and railings and also to the green of the garden that will grow in the future. The rough surface will acquire a patina over time.

Before deciding on the material, the architects visited fibre cement buildings by Max Graf (Pestalozzidorf Trogen School), Eduard Neuenschwander, and Haefeli Moser Steiger. Adrian Streich explains that he was impressed by how well the material had aged on these buildings from the late 1950s, which led him to use rough, untreated fibre cement panels here.

Hubertus Adam

Location: Alte Gfennstrasse, Claridenstrasse 30, 32 – 34, Dübendorf

Client: Pension Fund Swiss RE , Zurich

Architecture: Adrian Streich Architekten AG, Zurich

Landscape architecture: Schmid Landschaftsarchitekten GmbH, Zurich

Completion: 2022

Façade construction: Spleiss AG, Küsnacht

Façade material: Swisspearl Largo, natural grey, reverse side facing outward, with special clearance

29 UNTREATED

Esposito + Javet architectes associés

Mediating Stranger

The new building for the extension of the Bethusy school campus in Lausanne looks strange and yet familiar. The mineral façade conceals a timber construction with bright, comfortable learning spaces.

Text: Marion Elmer, photos: Anne-Laure Lechat, Esposito + Javet architectes associés

30 ARCH 2024 UNTREATED

32 ARCH 2024 UNTREATED ground floor 1:500 second floor

Bethusy school campus extension Via a footbridge lined with mighty pines, children and teens arrive at their classrooms in the new timber element building. It extends the spacious campus of the Bethusy school in the north of Lausanne. Eighty percent of the wood for the fivestorey building is from Switzerland. But this interior is barely visible from outside. Esposito + Javet wanted to trace the mineral character and the relief of the existing stone and concrete buildings with a façade of corrugated fibre-cement panels. The building thereby appears strange and yet familiar. In order to make the qualities of the material more visible and allow it to age naturally, the architects installed the fibre cement panels untreated: some of the panels are now slightly lighter, others darker. Bronze-coloured metal grids in front of the ventilation windows and blinds lend the façade a touch of noblesse. The new construction not only seeks proximity to the old, but also mediates between the different levels of the complex. By way of an external staircase, which begins next to the footbridge, or via internal access routes, pupils arrive at a lowerlying schoolyard, which is shaded by tall linden trees, and the adjacent sports field. The interior of the wooden building has a light, airy atmosphere. Owing to a windmill-like ground plan, in the hallway in front of each of the sixteen classrooms is a light-flooded, cozy vestibule in which the cloakroom lockers are discretely set into the walls. The actual construction is concealed behind the light-coloured wood panelling: twenty-centimetre-thick solid laminated timber walls, together with the central concrete core, support the prefab-

ricated wood-concrete composite ceilings. Internal access and sanitary facilities are located in the concrete core.

Natural light enters the classrooms from two, sometimes even three sides. Fresh air is guaranteed by the ventilation casement in the window, which is secured with a fixed, perforated grille. On the fourth floor, a terrace also serves as an outside classroom for research projects. From there, the gaze extends across the campus and Lake Geneva.

The fluorescent textual art by Elise Gagnebin-de Bons echoes as the pupils move through the new school building in the corridors and on the staircases. They fill and “inspire” the spaces like oxygen fills the lungs when they enter—“INSPIRE,” “EXPIRE”—and empty them “TON AIR,” “MON AIR”—when they leave the building during recess or at the end of the day.

Marion

Elmer

Location: Avenue de Béthusy, 7, Lausanne /CH

Client: City of Lausanne

Architecture: Esposito + Javet architectes associés, Lausanne

Completion: 2021 (competition 2018 )

Façade construction: Atelier Volet SA , St-Légier

Façade material: Ondapress- 36 , natural grey; Swisspearl Largo, natural grey, with special clearance

33 UNTREATED

With its corrugated fibre cement façade, the extension sets itself off from the existing stone and concrete buildings on the school campus.

An organically evolved town has a fragile beauty.

skilfully replaced the previous building with a new wooden house with a pitched roof of black, fibre cement shingles: today, it looks as if it had always been there.

34 ARCH 2024 UNTREATED ground floor 1:400 upper floor

Bernardo Bader

bernardo bader architekten

Single-Family Home Bizau

The Bizauerbach meanders lazily through the lower part of the village Bizau, which is called Unterdorf, and the main road loosely follows its course. Because of the riverbed, there is little development in the north, but in the south, houses line the street into Unterdorf. They adhere to traditional materials and the scale of the village. Rural functional architecture, simple houses, barns, and sheds made of wood, almost all with pitched roofs, marked by wind and weather, adapted to each other. Behind them, the fields stretch out and the houses form small groups along cul-de-sacs. Many of the old farm buildings are no longer in use; also the farmstead next to the carpenter’s workshop on the main road was empty for decades. It was typical for Bregenzerwald: a rectangular ground plan, house to the east, stable to the west, an open veranda-like porch in between, which in the area is known as a “Schopf,” (shed) with a shared pitched roof above. The farmhouse had belonged to the client’s father. Although she wanted to convert it, it couldn’t be saved.

Bernardo Bader then planned a new building on the same site with the same footprint, which he skilfully integrated as if it had always been there. The architect took the structure of the existing building and reinterpreted it. What was once a stable, is now a garage; and what was once a shed, is now a covered open space with a strong connection to the house and the landscape. The timber element construction is clad with a screen of rough-sawn vertical spruce slats, which will turn grey over time. The roof has a slight overhang that protects the wood, its grey fibre cement shingles age well and harmonize with the other houses and their grey shingled roofs. This allows the house to literally grow into Unterdorf. From the street, one could also suspect a barn behind the entirely closed façade. The barn door, with which the Schopf, the passageway, can be opened and closed, runs along a simple brass rail. Once again, and still today, it offers a direct connection to the field, which is now a sunny garden with a view of the landmark mountain, the Kanisfluh. It has become a place for arriv-

ing, storing things, lingering, and passing through. By means of the barn door, it can be expanded from a private, protected open space to a semi-public passageway. The living space on the ground floor is compacted to a square of nine by nine metres. This creates a covered terrace facing the garden on the south side, which is an angular expansion to the Schopf. A new quality. On the south side, the pitched roof has a contemporary look: two balconies are cut into the upper sleeping level. From the main road, you would never know they’re there.

Isabella Marboe

Location: Unterdorf, Bizau /AT

Architecture: bernardo bader architekten

Client: private

Completion: 2018

Façade construction: Peter Dachdecker, Schwarzenberg

Façade material: roof panel “Doppeldeckung” (double roofing), square 40 × 40 in black

35

UNTREATED

“It’s a matter of attitude, whether a house is allowed to change over time”

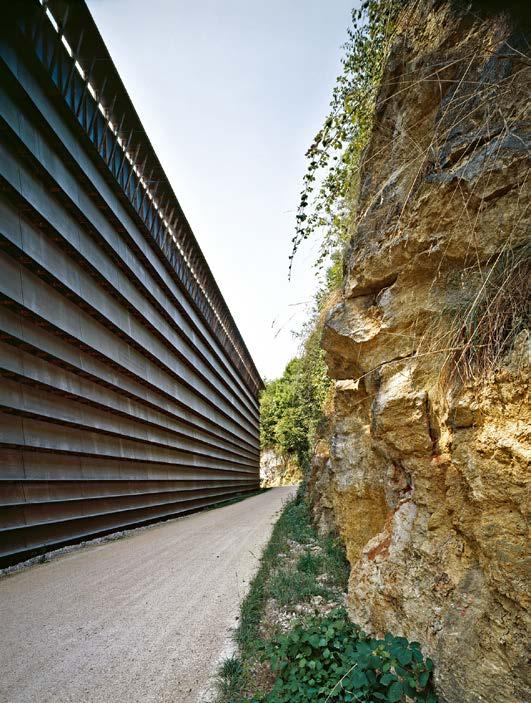

Nearly twenty years ago, EMI Architekten*innen from Zurich built a house for a gardener in the St. Galler Rheintal region. It’s a single-storey house with a flat pitched roof and a façade of untreated fibre cement panels. The client liked the idea that the façade would naturally age and acquire a patina.

In conversation, Ron Edelaar from EMI Architekt*innen explains why the building anticipated many issues that are still relevant for him today, and why they decided on untreated fibre cement panels back then.

Is the gardener’s house your office’s debut project?

Yes, that was our first house. When you’re allowed to build a house for the first time as a young architect, then that’s something extraordinarily exciting. But you can’t live out all your ambitions and dreams in the first house. Nonetheless, I think that with this house, a lot of things that still inspire us now came together, albeit intuitively. The client was a gardener and his partner. Their wish was to accommodate the nursery and a family home on a small piece of land. Next to the building plot was the house of the gardener’s grandfather, a stately home with shingle cladding and a mighty pitched roof. We knew from the start that the new building would have to be subordinate to the existing building, and lower. Because its use is hybrid, that

is, both a nursery and a home, it was also obvious to us that it should allow for different spatial constellations. Of course, the new building would also have to be surrounded by a garden, perhaps even be part of the garden. In order for the two to come together, it seemed obvious that the façade cladding should be capable of ageing. Combined with the extremely tight budget, untreated fibre cement panels proved suitable. At the time, this was a sub-roof panel.

What issues were you involved with, with the house, and which ones are still on your mind today?

Right now, the major issue that we are all dealing with is sustainability. At the same time, it is not just about ecology, but also about economic and social issues. In 2006, when we were planning the house, this wasn’t yet an issue. But we realized that economy and ecology can go hand in hand. The cost pressure was high. We saw that as an opportunity to take a new path with little money and a great deal of trust from the client. One aspect of saving money is minimizing materials. Fewer materials

Edelaar

EMI

means less investment costs. There is no basement, and the house is adaptable and changeable. Many components are screwed or plugged in. Parts can be easily dismantled and replaced.

Why is the house partly clad with fibre cement and partly with plywood panels?

Part of the nursery is unheated and uninsulated. The uninsulated area is clad with wood on the outside. The rear-ventilated façade of the inhabited part of the house is made of fibre cement.

36 ARCH 2024 UNTREATED

Ron

founded

Architekt*innen together with Elli Mosayebi and Christian Inderbitzin in 2004.

How has the façade changed?

Has anything been replaced yet?

The last time I was there was four or five years ago. Back then, the fibre cement panels had already become a bit lighter and patinated. The plywood façade still serves its purpose, even though the edges of the panels—as expected—have swollen. In the end, it is also a matter of attitude, a matter of wealth, when something is replaced. If you think that things have to always look new, then you have to invest money in them. Ultimately, that’s not particularly environmentally-friendly.

The question of whether the house still has to look new after twenty years’ time, or whether it should be allowed to age, also applies to the fibre cement façade. You opted for uncoated panels here, which attain a patina. That was a conscious decision. These suggestions usually come from us architects, and we also have to point out the consequences to our clients. I’m sure that the fibre cement façade will be around for another fifty years. Provided that there’s no change in ownership, and with that, the attitude of the owner with regard to the building.

What role does the aging process play for you?

It depends on how the house is designed. This house is allowed to show the effects of time, to change due to external influences, such as the weather and use. But it can also be changed again and again by the owners. As soon as a house is built, it is exposed to the forces of nature and of use. It wears out. And there, you have to decide whether you like the idea or not.

Interview: Anne Isopp

37

The house for a gardener is in Hinterforst in St. Galler Rheintal (year of completion 2007). The façade of plywood panels and fibre cement roof board has aged well, as the current photo shows.

UNTREATED

KNOW-HOW – Swisspearl offers not only fibre cement panels, but also photovoltaic systems. In order to provide these with the highest performance per surface area currently available, the entire solar range is being converted to one of the most modern cell technologies. In the future, the solar panels will also be available in colour.

The aim is clear: solar panels should offer the highest possible performance, and at the same time, meet high demands in terms of design. To achieve that, Swisspearl is working on two innovations: coloured solar panels and integration of cutting-edge solar technology.

The firm has offered solar panels for more than ten years now. In the beginning, they were simply photovoltaic elements mounted on the roof, so-called rooftop models. This type of construction still accounts for roughly 95 percent of the entire solar market today. Swisspearl, on the contrary, nowadays offers only solar panels that can be integrated flush in the roof and façade cladding, so-called integrated panels.

From now on, Swisspearl will equip all solar panels with one of the most modern cell technologies, TOPCon technology. The acronym TOPCon stands for Tunnel Oxide Passivated Contact. These highly efficient silicon solar cells are already used for rooftop modules, but not yet for integrated modules, because

it is a highly sensitive technology. “TOPCon cells react very sensitively to water vapour,” explains Ammar Naji, product manager for the solar sector at Swisspearl. “This can lead to delamination. That’s why you have to encapsulate the cells well. We do this in very stable glass-glass standard modules.” Compared to the PERC technology used until now, with TOPCon technology efficiency increases from 18.5 to 20.15 percent.

The solar cells are now protected between two 3.2-millimetre-thick glass plates. Currently, the glass is available as standard solar glass or glazed. In the future, however, the plan is to offer these solar panels in colour. This development is still in the pilot phase, but you can already see the added value that colour brings to design at the Swisspearl factory site in Niederurnen.

In autumn 2023, a new 8,000-square-metre production hall was opened there; the roof and parts of the façade are coated with photovoltaic modules. Here, one should pay attention especially to the longitudinal side

DESIGN SCOPE FOR

38 ARCH 2024

The solar panels can be complemented with fibre cement panels of the same colour (on the edge of the roof) or blank modules (e. g., under the windowsills).

PHOTOVOLTAIC FA Ç ADES

with the double gable. While from a distance the matte green façade cladding creates a homogenous façade image, up-close the fine resolution of the solar cells behind the green glass panels can be seen. Only on second glance is it apparent that the solar modules in the area of the gable and the door reveals have been combined with fibre cement panels in the same green colour. At the end of the pilot phase, these coloured solar modules will be available in other standard colours in addition to green.

Anne Isopp

39

DESIGN – Zurich-based industrial designer Sébastien El Idrissi has designed a stackable raised garden bed. The bottom shape and the insertable frames are made of uncoated fibre cement. Like the plants, the material will also change its appearance with the weather and time, and therefore fits well in the urban environment.

A STACK OF EARTH

40 ARCH 2024

By definition, a raised garden bed is an elevated bed. Some people build raised beds so that they don’t have to bend down anymore, others because they see it as the only possibility to plant a small garden in an urban space.

“There is a great desire to plant things in the city,” says industrial designer Sébastien El Idrissi. For the plants to thrive, they need generous amounts of soil. The raised beds that El Idrissi encountered in the city were mainly wood-panel-framed or galvanized boxes. They all serve their purpose. El Idrissi, who values coherent concepts, durable design, and efficiency in all his works, wanted to design a raised bed for Swisspearl that would be more beautiful, more durable, and could also become an integral part of urban architecture.

He designed the stackable building system Stack, which consists of a rectangular or square base shape with a drain, and different size extension frames. These frames can be stacked on top of each other. All elements are thirty centimetres high, seventy-six centimetres wide, and of different lengths.

The ability to stack frames of different sizes makes it easy to combine plants of different heights and allows for many creative variations. The raised beds can be placed directly on the ground, on a base, or on wheels.

A prototype stands outside the industrial designer’s Zurich studio. “I like to see how the fibre cement changes with the weather,” says Sébastien El Idrissi. “When it has rained for a few days, the pot is very dark. And because the pot is so deep, you can also see how the soil and the frame slowly dry from top to bottom. Over time,

patina will be added, which means that the raised-bed will integrate more and more into the urban environment.”

The raised bed is already being produced in small quantities in Swisspearl’s hand molding shop. Although these are still prototypes, the product has already won the Good Design Award and been nominated for two other design awards. Anne Isopp

Sébastien El Idrissi Studio: www.seis.studio

With this stackable construction system of rectangular and square shapes, everyone can design their own customized raised bed garden.

41

AT THE START – Vidic Grohar Arhitekti is a young architectural firm from Slovenia that focuses on the conversion of former industrial buildings, a building task that first gained importance in Slovenia over the last decade. Anja Vidic and Jure Grohar are convinced that good architecture can also be created with limited resources.

Your portfolio includes numerous renovations and adaptations of industrial buildings. What led to that?

It happened by chance. Our first project was a restaurant that a client wanted to set up in a hall in the former Litostroj industrial area. Although the area was neglected at the time and without any public use—which is why a lot of people questioned the decision to open a restaurant there—the restaurant was successful. It became a catalyst for the further development of the industrial area. Gradually, other users moved in who needed space, so new project commissions followed.

What aspects of industrial heritage would you highlight in particular?

Architects can approach the conversion of industrial buildings in a casual, radical way since they usually are not strictly protected buildings. Industrial halls are unassuming in terms of structure and design, but they have a special character and numerous spatial qualities. The size and universality of the space allow for unconventional architectural solutions, and also flexibility in the program.

What are the greatest challenges when renovating these types of industrial buildings: architecturally and also technically? The generosity of the space is a great feature, but also a challenge. The huge dimensions of industrial halls result in high costs. To optimize energy consumption, we often set up different heating zones. Repeating the same elements saves costs, too. With such a large area, only some of the visible elements need to be designed uniquely, while we look for standardized solutions for the others. This gives the space its own character and, at the same time, allows the project to be realized within budget.

What role does the conversion of industrial heritage play in sustainable urban development?

Industrial buildings are usually located close to urban centres and present an area of urban expansion and densification. For that reason, considering how to reanimate industrial zones and integrate them in the urban fabric both programmatically and in terms of infrastructure are extremely relevant. In Ljubljana, a change in the spatial development plan would be necessary: the current plan does not allow for any residential building programmes in industrial areas, as is already a common practice abroad.

One of your projects is the Hall L56 in the Litostroj industrial zone in Ljubljana. What do the concept and the choice of materials look like?

The project was carried out during the Covid-19 epidemic. Since it was difficult to coordinate the details and watch over the realization, we planned the renovation in a very rational and simple way. As main building material, we used common hollow blocks that in contrast to concrete, allow for later corrections and quick work. Finally, we coated the hollow blocks with a thin layer of silver paint to lend the otherwise raw interior a certain refinement or sophistication. Another decisive factor in the concept

for Hall 56 was its programmatic flexibility. In a few months, the Slovenian National Theater will use this hall as a temporary home while the theatre in the centre of Ljubljana is being renovated. For this, we had to design theatre halls, offices, foyer, and the like. This resulted in temporary and permanent interventions.

What insights have you gained from your work on industrial buildings?

Good architecture can also be created with minimal means, or regardless of the means. Often, it is strict criteria that yield the most creative solutions.

The interview was conducted by Eva Gusel, designer and architecture critic in Ljubljana. www.vidicgrohar.com

42 ARCH 2024

For the new installations in the L56 multipurpose hall, Vidiv Grohar used hollow blocks that were coated with silver paint.

VIDIC GROHAR ARHITEKTI

AAnja Vidic and Jure Grohar founded their architectural firm in Ljubljana in 2017. Together, they teach at the Faculty of Architecture in Ljubljana. In the course of their teaching, they have developed their own approach to architectural design. By critically confronting modern social phenomena, they incorporate them into the architectural project.

Dear readers,

For us, ARCH is more than a trade magazine for building with fibre cement. It reflects our great interest and enthusiasm for high-quality architecture.

Over the many decades that we have published this magazine, not only its design and selection of themes has changed, but we, too, have continually changed as a company.

As you probably know, Swisspearl has meanwhile grown to become the second largest fibre cement manufacturer in Europe and is thereby represented well beyond Switzerland, Austria, and Slovenia. We have factories and sales organizations in sixteen European countries and numerous representatives throughout the world. For that reason, starting with this issue, ARCH will be published not only in German and French, but also in English. This will allow us to communicate our desire to contribute to building culture to all the countries in our group. ARCH also serves us for further education internally, in matters related to building culture.

The theme of this issue is the untreated: currently, there is great interest in untreated fibre cement panels that acquire a patina over time. This expresses a current development that we, as a company, are also intensely involved with: the issue of sustainability. We have now been able to make an important step towards greater sustainability: over the coming months, we are switching the production in all Swisspearl plants to a new, more sustainable cement mix. In addition, we are building a large solar installation on the roofs of our Swiss location in Niederurnen, with which we can produce roughly 50 percent of our energy needs. We take the issue of sustainability very seriously, and are constantly striving to adopt further measures to combat climate change.

I am therefore all the more pleased to be able to present you with the new ARCH, in which sustainability plays an important role.

I wish you inspiring reading.

Marco Wenger, CEO Swisspearl Group

ARCH. Architecture with fibre cement

Suscriptions /changes of address arch@ch.swisspearl.com

ISSN 2673-8961 (German)

ISSN 2673-8988 (French)

ISSN 2813-9518 (English)

Publisher Swisspearl Group AG, Niederurnen www.swisspearl-group.com

Advisory Board

Martin Tschanz, lecturer ZHAW Winterthur

Gabriele Kaiser, architectural publicist, Vienna

Hans-Jörg Kasper, Swisspearl Group AG

Marco Pappi, Swisspearl Schweiz AG

Project manager: Gabriella Gianoli, Berne

Editor: Anne Isopp, Vienna

Editing: Marion Elmer, Zurich

Translation: Lisa Rosenblatt, Vienna

Design: Schön & Berger, Zurich

Detail plans: Deck 4, Zurich

Printing company: Galledia, Flawil

Photos

Cover page Niklaus Spoerri

p. 1, 12–16,17 above, 22–23 Niklaus Spoerri

p. 2 above left, right AA Nanotourism

Archive

p. 2 below left Paul Sebesta

S. 3 dekleva gregorič architects

p. 4 Graphic Collection of the Academy of Fine Arts

Vienna

p. 5 Gregor Graf

p. 6 Keystone/STR

p. 7 Keystone/Gaëtan Bally

p. 8 Tom Cornille

p. 9 above left Georg Aerni, Essertes, 2019

p. 9 below left alamy

p. 9 right Johannes Stoll/Belvedere, Vienna

p. 10 Jürg Zimmermann Fotografie

p. 11 Architekturzentrum Wien, collection, photo: Margherita Spiluttini

p. 17. below, 18, 21 right Boris Haberthür p. 19 Yves Kubli

p. 20 Scheibler & Villard, Baumann Lukas

Architektur

p. 21 above left Weisswert.ch

p. 21 below left Rasmus Norlander

p. 24, 26 Edon Miseri

p. 25, 27 Philip Heckhausen

p. 28–29 Roland Bernath

p. 30, 31, 33 Anne-Laure Lechat

p. 32 Esposito + Javet architectes associés

p. 34–35 David Schreyer

p. 36 Anne Morgenstern

p. 37–39 Samuel Trümpy

p. 40–41 Sébastien El Idrissi Studio

p. 42 Anja Vidic

p. 43 Larry Williams

Back page Franz Hubmann/private archive Hollein

Legal notes

Texts, images, photos, and graphic work in this publication are protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights. The contents of this publication may not be copied, distributed, altered, or made available to third parties for commercial purposes. The publisher cannot guarantee freedom from error and the complete accuracy of the information it contains. The plans have been kindly provided by the architects. The detailed plans have been reworked for greater legibility.

EPILOGUE IMPRESSUM

www.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Schweiz AG Niederurnen

Phone: +41 55 617 1111 Mail: info@ch.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Österreich GmbH Vöcklabruck Phone: +43 7672 7070 Mail: info@at.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Fassaden- und Dachprodukte DE GmbH, Nittenau Phone: +49 9436 903 3297 Mail: info@de.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Belgium NV. Aartselaar Phone: +32 3292 3010 Mail: info@be.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Česká republika a.s. Beroun Phone: +420 311 744 111 Mail: info@cz.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Danmark A/S Aalborg Phone: +45 9937 2222 Mail: info@dk.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl France SAS Briançon Cedex Phone: +33 492 212 465 Mail: info@fr.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl GB Ltd Warrington Phone: +44 20 3372 2300 Mail: info@gb.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Ireland Ltd Ballycoolen Dublin

Phone: +353 1 9058300 Mail: info@ie.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Magyarország Gyártó Kft Nyergesújfalu Phone: +36 33 887 700 Mail: info@hu.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Nederland B.V. Enter Phone: +31 85 489 07 10 Mail: info@nl.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Norge AS Slemmestad Phone: +47 31 29 77 00 Mail: info@no.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Polska Sp. z o.o. Warszawa Phone: +48 22 395 72 80 Mail: info@pl.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Slovenija d.o.o. Deskle Phone: +386 5 392 1572 Mail: info@si.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Suomi Oy Lohja Phone: +358 19287 61 Mail: info@fi.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Sverige AB Stockholm Phone: +46 08 506 608 00 Mail: info@se.swisspearl.com

Time travel in a fibre cement pipe

Hans Hollein passed away exactly ten years ago, in 2014. However, with his expanded concept of architecture, the Austrian architect continues to influence the younger generation to this day. His oeuvre includes not only numerous buildings, drawings, and design objects. Exhibition designs are also a part, such as this one for Swisspearl (formerly Eternit) on the occasion of the International Water Management Congress in the Vienna Hofburg in 1969. Back then, the company still produced pipes from fibre cement.

www.swisspearl.com

Swisspearl Magyarország Gyártó Kft