1 Architecture 2022

First published for ‘Assemblage 2022’, The Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning Graduate Exhibition 2022.

School of Architecture, Design and Planning University of Sydney Wilkinson Building 148 City Road University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia

We acknowledge and pay respect to the Traditional Owners of the land on which the

University of Sydney is built: the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. We pay respect to the knowledge embedded forever within the Aboriginal Custodianship of Country.

4

5 Contents

Editorial Foreword Conversations Reaching out to New Ways: A Yarn on Country, Culture and Community Michael Mossman, Genevieve Murray MT_VT 08112022 Michael Tawa, Vesna Trobec Where to, Sydney? Caleb Niethe, Melissa Liando Master of Architecture Conversations Brain, Mind and Mallett Street project Chris L. Smith, Donald McNeill, Leigh-Anne Hepburn, Jason Dibbs Futuring the Sonic Dimensions of Urban Protest Clare Cooper, Dallas Rogers Always, Onwards Justine Anderson and Georgia Tuckey Bachelor of Design in Architecture Bachelor of Architecture and Environments Public Programming and Electives Sponsors 6 8 10 12 18 22 26 102 106 110 114 154 182 200

Dean’s Welcome

Dean’s Welcome

Professor Robyn Dowling Dean and Head of School

The Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning sits proudly on Gadigal land, where Aboriginal people have taught, learnt and nurtured since time immemorial. At the beginning of the 2022 academic year the School was delighted to welcome new students from across our disciplines through activities on the site now known as Gadigal Green, once a popular Gadigal fishing spot in Blackwattle Creek. We also welcomed students joining us from dozens of countries across the world, studying remotely from across Australia and the world - Kamilaroi, Dharug, Melbourne, Beijing, Mexico to name a few. The collective learnings across these geographies come together – are assembled – in the 2022 Graduate Show.

Architects, designers and planners came together in myriad ways in 2022. The visit of our Rothwell Co-Chairs and Pritzker Prize winners, Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal, reminded students, staff and our professions of the positive design and social outcomes that come from putting people first and reconsidering the need for demolition. The Tin Sheds Gallery hosted a full program of events and exhibitions, culminating with salient reflections on gender and technology in SHErobots. Through yarning circles and a project on indigenising the curriculum, staff and students continued to reflect on Indigenous perspectives and places in our curricula and practices.

The School will continue its activities to lead thought on designed and built environments into 2023. In conjunction with the University’s Sydney 2032 Strategy, we intend to expand our post-professional offerings, welcome students to our new Bachelor of Design (Interaction Design), and look forward to the return of our Rothwell Co-Chairs to both studio and a Tin Sheds exhibition. There are many other activities too numerous to mention: the Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning will remain a vibrant assembler of communities, materials, and practices for many years to come.

I wish our graduating students well and look forwarding to welcoming you back to the University throughout your careers.

7

Kate Goodwin Professor of Practice, Architecture

Kate Goodwin Professor of Practice, Architecture

The term ‘Assemblage Art’ was coined in the 1950’s by French artist Jean Dubuffet, but it has a lineage that runs back into the early moments of the 20th century with continued currency today. Assemblage Art brings together disparate everyday objects, scavenged and purchased, into physical compositions and experiences that unsettles distinctions between painting, sculpture and performance. It came to challenge the very definitions of art itself. The methods and logic of assemblage came to be associated with the Cubist constructions of Pablo Picasso and George Braque, the Ready-mades of the Surrealists, Kurt Schwitter’s ‘Merz’, the 1950s Abstract Expressionists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, Allan Kaprow’s “happenings” of the 1960s and 70s, Jannis Kounellis’ gallery interventions and recent practises of installation art. Likewise, it has infiltrated architecture, design, and urbanism.

The title Assemblage for the 2022 Graduate Exhibition of the Sydney School of Architecture, Design and Planning, expresses the creation of an experience that brings together a colourful and complex mix of disciplines, ideas, and devotees. Overtaking the Wilkinson building for 2 weeks, the exhibition has been devised over the past semester by a dedicated team of students from five different degrees. Along with the supporting marketing material, website and catalogues it reflects the creative energy emanating from the School. The logo, formed of three shapes –representative of the disciplines and derived from the staircase at the heart of the building – come together to create a form more compelling than any one on its own. In a similar fashion, alongside the work of the graduating students, this catalogue assembles conversations, across disciplines, experience and generations. Through conversations – in the act of listening and speaking – ideas are debated, a common ground is found, and ideas evolve.

Ultimately Assemblage is a celebration of these rich relationships and the captivating manner by which our graduating cohort of 2022 explore and express such relations in a diversity of ideas, forms, materials, places and people. Such assemblages are never entirely complete, but themselves connect into other artforms, architectures, designs and contexts… and extend into the brightest of futures.

9

Editorial

Foreword

Lee Stickells Head of Architecture

Happening.

An assemblage is more than a collection. Assemblages are open-ended gatherings. The decision by students to frame this year’s exhibition through the idea of assemblage resonates with one of the great pleasures I’ve found in this school’s end-ofyear shows—their tendency toward uncoordinated, emergent patternings. They are never just the flattened cohabitation of student projects. While from year to year they may be more or less tightly curated, the school’s exhibitions have consistently provided a vital framework for generative discussion. The exhibited work often reveals sharply differing positions. But it’s a heterogeneity tilted toward serious and transformative debate rather than a placid, all-accommodating pluralism. The students’ capacities of architectural expression, powers of invention, of fabulation, don’t just gather ways of thinking about architecture; they make them. This emergent quality can be felt especially on opening night, drink in hand, amongst the swirling conversational buzz of staff, students, family, friends and the wider profession. Exhibition openings are “happenings” and, this year, they’re happening again! It’s thrilling and rejuvenating for the school to welcome its community back together again, in-person, to celebrate the students’ endeavours. I want to offer sincere thanks here to the staff, students and the huge extended network of family, friends and professional peers that have made the 2022 exhibition (and this catalogue) a brilliant reality. Most especially, hearty congratulations to the students who worked indefatigably to realise the projects on display. Thanks for holding tight, for keeping it together and giving us clear proof that we’re sending another generation of informed, conscientious, creative, and purposeful professionals into the world.

11

Reaching out to New Ways: A Yarn on Country, Culture and Community

MICHAEL MOSSMAN

In an exciting new step, the Architects Accreditation Council of Australia has introduced the National Standard of Competency for Architects that involves applying First Nations knowledge systems as integral to the architectural education process as well as practice. This means the inclusion of First Nations narratives of place, that were invisible or less present in the past, are now enriching the qualities of built environments in Australia. How do practitioners relate to the context of Country in ways different to normative design processes?

It’s always inspiring when there’s practitioners who are reaching out to and engaging with this space and Genevieve Murray is a great example. The School of Architecture, Design and Planning is currently in the process of developing a strategy, a critical review of our current position and how we can engage in curriculum and pedagogies that elevate Country, Community and Culture across the School.

Studios such as the one co-designed by the Blue Mountains Aboriginal community and Genevieve provide solid foundations for new processes that appreciate the confluence of Country and the built environment. How have you found the qualities of the new accreditation criteria on architectural studio practices and its impact on student learning?

GENEVIEVE MURRAY

It’s exciting to see how the accreditation criteria changes are transforming pedagogies within the university, but it will take time as the process is by necessity a slow one. This is a process that is ideally lead by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander practitioners across all years and in all courses within the school. Importantly, the conversations become more sophisticated as students move through their courses.

MM

Part of the process of facilitating these conversations is providing a location to carry out these pedagogies. We are developing strategies to ensure the activation of studios working with Communities are more than just a small cohort of students working with practitioners like you, it needs to be available across the whole school.

GM

The reason that this process must be taken forward with great care is that it takes a long time to overcome firstly the very long absence of First Nations knowledges in our universities and secondly it takes time to build the right cultural competency

12

and relationships to support that. We have some good guidelines, but every context is different. What we know is that universalism is an imperial mindset. From what I’ve been taught, Gadigal or Darug or Dharawal ways of doing and being are very place specific, very contextual, and almost the antithesis of universal. So, in every project and every place there’s always something different and new to learn. For that reason, as practitioners and as students, we have to understand that all of the relationships are ongoing, and not transactional or contained within the context of a particular project.

The beauty I have found within Aboriginal Communities is connection, a caring ethic for you as a person, for you as a practitioner, for you as a member of their Community. There’s a wonderful gift that comes through really deep listening and being present. We often rush into things because we want to get to the conceptual design milestone and the schematic design milestone and the developed design milestone and get the construction underway. These pressures around time are part of an imperial mindset too and can have detrimental impacts if there isn’t the right amount of time built into these processes.

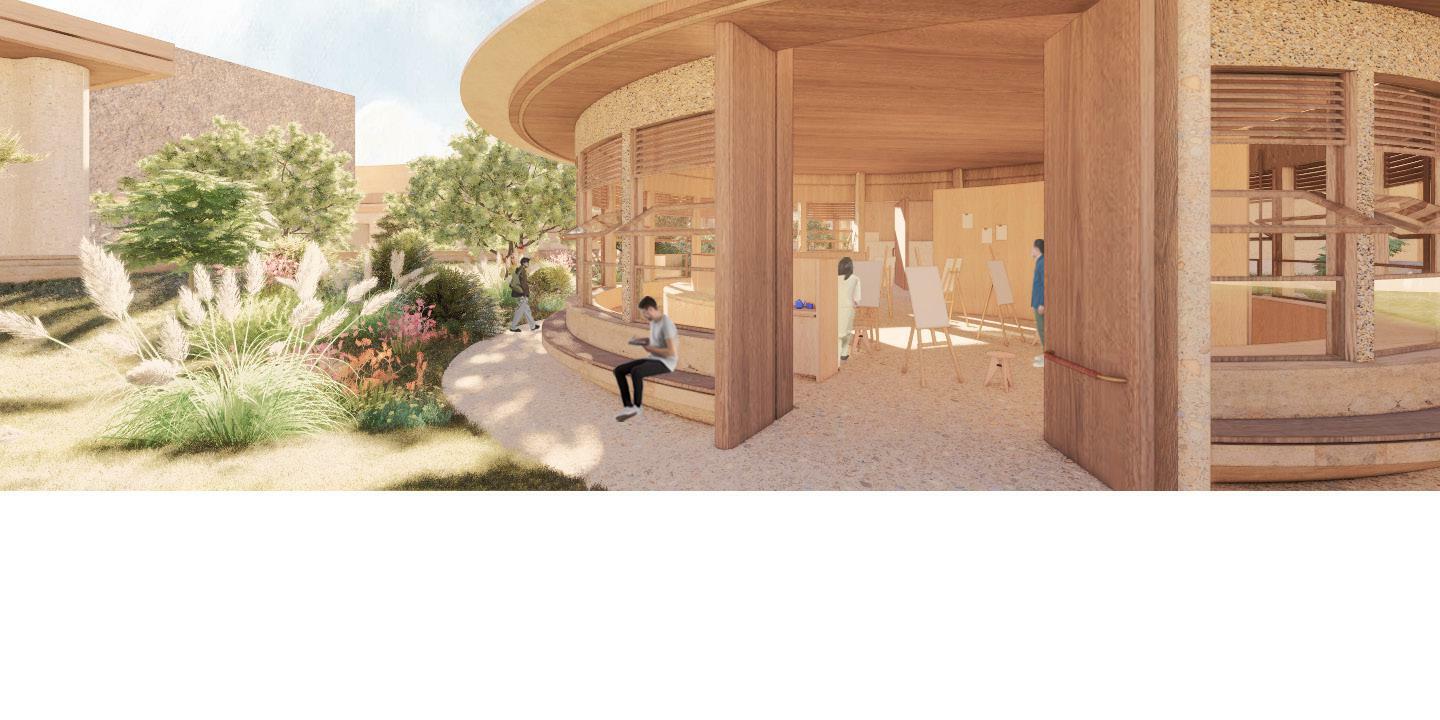

MM You’ve run a graduation studio for the Masters this semester that I think is a benchmark for applying First Nations knowledge systems to teaching and student output and we’ve been engaged to do a workshop and report on the findings and outcomes of the studio to be delivered to the AACA. How did the studio come about?

GM

As an educator I want the students to be able to put their energy and effort into something which can really support an existing initiative that has been established on good cultural protocols. This project has been in development for a year and a half and the relationships with Aunty Carol Cooper and Auntie Jacinta Tobin and Walanmarra Artists, an Aboriginal women elders group in the Blue Mountains are all relationships that my sister and I have had with the Community for many years.

The students are given a window into the process –it’s not a start and finish moment. Once the students finish this semester, I’ll continue to take it forward with all their energy and input and that keeps going.

MM How do you have those conversations with Community about working with a group of students and what was the process of students meeting with Community members?

GM I introduce the idea before I commit to it. Its proper protocol to make sure the Community is happy

13 CONVERSATIONS

MM

to have people working with them. And once the permission was given, we walked Country with Aunty Carol and Uncle Robbie Bell to get the students minds and their hearts in the right place to be able to engage in the studio. Aunty Carol is a Gundungurra and Darug woman, and Uncle Robbie is Wiradjuri but grew up in southwest Sydney, on Dharawal Country and is connected to our family as my sister’s been friends with him for 20 years. It was important to have Aunty Carol introduce the students to her Country so they were not thinking about outcomes but thinking about and for Country and its custodians.

What were the comments or feedback or of inspirations did the students about walking Country and interacting with elder custodians, knowledge holders?

GM

There was some truth-telling that was really important in terms of them expanding their understanding of Country and beginning to learn what that might mean. They didn’t know about Warragamba Dam having displaced Auntie Carol’s family from the Burragorang Valley. They didn’t know how her family and the small Aboriginal Community in Katoomba had to move to The Gully and were displaced again when a decision was made to build a racetrack when their houses were burnt down. It is critical we have indepth knowledge of the history of dispossession and displacement that is quite often driven by planning processes and associated infrastructure such as the dam.

There’s a lot of education needed, particularly in the urban context, of the impacts of colonization. I told the students they need to see themselves creating opportunity for conversations and rich learning collectively – Aboriginal knowledges are not something there for us to have or to take. Reciprocity and relationality are of course key.

MM

How do you think that experience and the workshops with Community impacts the students when they get back into the studio where they’re often disengaged from the reality?

GM

There was a real tension that emerged about how to do anything because we don’t know what’s right and how to do it. I acknowledge it is heavy stuff, but we need to understand that half of the women we’re working with have lived experience of homelessness. They’re all artists, they love creativity, they love community, they love sharing. We need to meet them where they are and in their contemporary life. They’re telling us that they really need some control and agency over housing for themselves. This is what we as architects need to respond to using our set of skills.

14

For me it’s important that we always approach it with joy and generosity and without judgment. And to be listening really carefully and not to be scared. I said to the students, “you’re going to make mistakes”, but I’ve set up processes within the studio, that will minimize the impact on community. One of the things that we don’t want to do as educators is cause harm. We need checks and balances in place - students would present their work in studio and receive some critique and feedback before it is taken to Community.

As settlers, there’s things that haven’t been resolved and there’s discomfort. The students got to experience the tension in themselves, and I encouraged them to sit with it and not walk away from it and really make sure we do work that supports these women in the right way.

MM

It’s a hard process given the limited resources on hand with people with skills like yourself. For me as well, it’s challenging to find the balance –particularly knowing how much to engage in the face of burn out and becoming overly stressed in these situations. How do you deal with the rigors of these types of interactions, knowing how powerful they are?

GM

I’m lucky to live in the Blue Mountains and while everywhere is Country, I’ve got so much more access to the bush in my day-to-day life. One of the things that Aunty Jacinta was saying to me was, “you need to listen to Country” and even though as a settler it makes me deeply uncomfortable, I encouraged myself to start doing it. What I realised was how supported I am by Country - the beautiful grandma trees, the big old, old girls, they sit with you, and they hold you. I think because I’ve been able to slowly develop relationships with Traditional Owners that are full and deeply reciprocal, there’s real love and I feel wonder and support in this place. That’s what takes care of me for the most part.

I think one thing that is a hard for us working in the system is slowing things down. There’s always urgency and students have so much pressure on them to deliver. There’s little space for reflection and contemplation and for just being.

MM

With all of the foregrounding of information and deep listening, you have to apply it to meet the institutional objectives of an architecture school, that’s what accreditation is about. Genevieve, what’s a quality of a student work that has leapt out at you, that has made you think differently or what you think has made an impact on the way that they think about architecture?

GM

One of the students, without me having to teach them

15 CONVERSATIONS

MM

anything, had exactly the right mindset around whose knowledges we were talking about. We went through a co-design process with the studio which they’d never done before and it included conversations around intellectual property - what we can and can’t use, what we can and can’t talk about. And one student did it with the most gentle ease, because in their culture that’s the way they’re taught to relate to their families and their communities. Their lived experience had embedded within it a very different mindset and a very different way of working, which was from a place of collaboration, from a place of deep respect for elders and with strict protocol.

Lived experience is important and covering the accreditation criteria within a one semester studio is a challenge. You need to build people’s literacy and cultural competency slowly over the course of the degree. This is important so when they get to fifth year, they can have sophisticated conversations, going into practice with an incredible skill set. We’re still a long way off but we need to be patient and continue building it up slowly.

Thank you for your time Genevieve. It is a pleasure to reflect on practices and understand the thinking behind the studio. There’s always opportunities for architectural education to interact with Country, Community and Culture meaningfully and to facilitate broader networks of thinking into student learning processes and reaching out to new ways.

GM Thank you Michael.

Genevieve Murray

Future Method is a research and design studio Co-directed with Wiradjuri antidisciplinary artist Joel Sherwood-Spring. They actively push the line between the practical and the abstract — seeking to extend and enrich the field of interdisciplinarity and collective culture and push them into the public domain.

Dr Michael Mossman

Michael is a Lecturer, Researcher and Associate Dean Indigenous at the School of Architecture, Design and Planning. He is a registered architect (non-practicing) and is a committed advocate for Country and First Nations ways in architecture and placemaking.

16

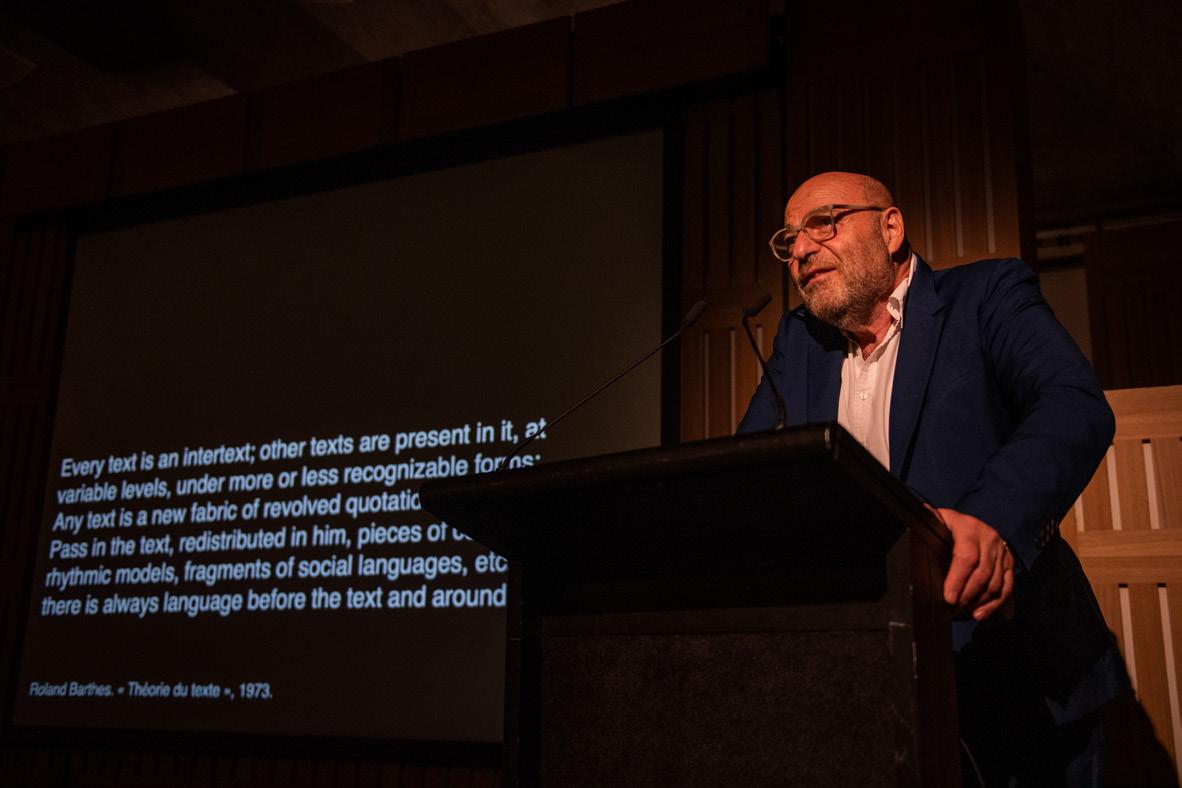

MT_VT 08112022

Professor Michael Tawa, and former student, now colleague and fellow Masters studio tutor Vesna Trobec share a conversation on shared interests and appreciation of one another’s work.

MICHAEL TAWA

I was thinking about my own time at university, what really captivated and inspired me… this came via one of my teachers, L. Peter Kollar, who was charismatic, but also evocative; he took us into a world of symbols, of architecture as a means of connecting with deeper things – though he would have used the term higher things, transcendent things. He was a neo-Platonist, so from him I looked to Plato, Aristotle, the Pythagoreans, from there to metaphysics, mysticism, mythology. These things don’t have much currency now, but I still return to these ideas, and they still inspire me.

What inspires you?

VESNA TROBEC

Two types of experiences at university inspired me most profoundly, and the effects of these experiences still influence and energise me now.

One was the discovery of very abstract thought and its relationship to place-making. My first-year tutor, Marcus Trimble, showed how you could flip a spatial idea upside-down and discover possibilities that you couldn’t have previously conceived. Matt Chan encouraged me to pursue the “irrational”, to see what spaces could emerge. And in my final year you tasked us with designing to “enhance experience,” which led to an intense exploration about how design interventions connect us with “deeper things”. The most inventive design work I do now arises from this kind of abstract thinking.

The other was being totally immersed in real communities, using my skills to respond to real-world scenarios: with Col James on projects for Aboriginal families; on public infrastructure projects in Papua New Guinea; engaging with the local drug user community in Vancouver to stage an architectural protest on the streets and advocate for safe injecting places.

So, what is inspiring, is this combination of abstract thought and very practical application.

MT

I’ve often wondered about this apparent dilemma, so to call it, between abstract thought and practical application.

Abstract means “drawn-away-from.” But from what?

18

And where to? In philosophy, this `what’ and `where’ is the concrete, the material, the practical. Which means that in the abstract we are consigned to being away, absent, impractical. Practical means “pertaining to doing, to action.” With the practical we are always “concerned with business,” with “doing.”

Yet, obviously, abstraction is a practice (in thinking I undertake a process of abstraction) and practice necessitates abstraction (in building I abstract from concrete situations in order to be able to act in other concrete situations, eg. I use abstract geometry to measure out a building).

Ancient Greek thought gave us a dichotomy between the abstract and the concrete, between thinking and doing, between theory and practice. Maybe that dichotomy is no longer useful? No longer practical?

VT

I find the challenge of bringing abstract thought and practical application into one singular thing the most challenging and interesting. To work from a place of abstract thought and to design something that the client can afford to build and see the value in building, is very hard and very rewarding when it works. I agree with you—as soon as you start designing with space using plans, sections, models, the computer, the process of abstraction has begun.

MT

The majority of architecture graduates go into established firms and they are happy with that. Very few start up their own firm. You’ve done that now and are building it up project by project.

What was it that triggered your wanting to set up your own office? Did your architectural education prepare you for that prospect?

VT

There are different ways to practice architecture. I worked full time in established firms as a junior architect before starting a practice with my university classmate Langzi Chiu. We matched each other’s energy, and we were naive as well, which is a good combination because you go out there and try. We did this for two years. It was great. We learned the basics of business and marketing, of preparing contracts, solving problems, working with others. These were new skills for us; they weren’t the focus of our architecture education; but they have been very useful in my career so far. We started to learn how to be confident about our own design ideas. This building of confidence starts at university but is very different once money and risk are involved.

After that, I ran the front-end design team in a commercial office for a few years and then started my own practice Studio Trobec, which happened organically as clients started to come to me for

19 CONVERSATIONS

their projects on the backs of recommendations from previous clients, their family and friends.

I don’t think that my architecture education prepared me for setting up my own office, but I think that is absolutely fine. I appreciated the University of Sydney focus on abstract thought, theory, art practice, experimentation, and philosophy. There is so much time later to work out business and marketing, but there is much less time later to develop the creative mind.

If there was going to be a course at university to better prepare students for the prospect of setting up their own practice, it would be about marketing and the economy. It might look at the different kinds of clients (private clients, developers, government) and how they work and what their end goals are. It would be about who to know and where to position yourself. It might address the sexism in the industry, which is most obvious when working with developers. I also think there should be a focus on women’s voices as they’re too silenced in our industry especially if you’re naturally quiet.

How has it been for you to be in academia?

MT Academia has been everything for me. I’ve designed and built a few things, and I still like building what I can manage, given the temperament and tools at my disposal. Even if it seems a case of overreaching and underdelivering. But really, I have been institutionalised in the academy since I first started teaching in 1980. I could not have run my own architectural practice. My kind of doing, my kind of praxis, doesn’t map well over what is required to run a business. So, ideas have been the focus: theory, abstraction. I think this path presented itself to me when I first tutored and felt comfortable in mediating between ideas and the struggle of someone to engage with them and manage them. And what this has made possible is both a blessing and a curse.

Blessing: the distance and prospects it affords, seeing things that are commonly missed, the labyrinth of words and ideas, the interconnectedness of things, the delight of reading one or another passage of remarkable lucidity... Curse: that same distance means I am often absent, even in-the-midst of intense engagement; or that I seek departure, even before arriving. But that too is a blessing: the joy of travel, of always-already having left.

VT

How do you see architectural education now? How would you reflect on the many cohorts of graduates you have influenced over the years?

MT

The students I’ve worked with at the University of Sydney have been the best of the best, no doubt:

20

intelligent, committed, inventive, insightful… I know they will find ways to make impactful work in practice, in education, in advocacies of all kinds. As for the remainder, it’s a challenge. They are subject to the marketisation of the academy, the pervasiveness of education following business rather than pedagogical models, the mass commodification of attention by digital media, the many personal, logistical and financial constraints... The greatest challenge for an educator now is how to meet this generalised distractedness that forecloses systematic, patient and enduring learning: close, precise readings of texts and buildings; reiterative drawing of implications; slow build-up of complexly layered design propositions; fully embodied practices of looking, listening, drawing… And the institution responds by falling into line, competing for attentiveness, concocting ever new techniques of entertainment: essentially promoting the status quo. There are moments of insight and delight of course; but overall, it looks for all things like a crisis to me. Which is not at all to be regretted, but rather seen as an opportunity to be seized.

Vesna Trobec graduated with a MARCH from the University of Sydney in 2014. She has learned that to create the best architecture she has to stay deeply engaged with it through a combination of teaching, art practice, and collaboration with other designers and clients. She established Studio Trobec to create a working environment for these processes. Recently Studio Trobec won a public architecture competition to design a memorial in Darlinghurst.

Michael Tawa graduated with a BARCH from the University of NSW in 1980 and a PhD in 1990. He has taught architectural theory, history and design for over 30 years in Sydney, Adelaide, Paris, Ottawa and Newcastle upon Tyne. His publications include Agencies of the frame: tectonic strategies in cinema and architecture (2010), Theorising the project: a thematic approach top architectural design (2011) and Atmosphere, architecture, cinema: thematic reflections on ambiance and place (2022).

21 CONVERSATIONS

Where to, Sydney?

Graduating student Caleb Niethe sits down with Architect Melissa Liando to reflect on how context influences study and practice, and what it calls on from architects.

CALEB NIETHE

Melissa, you graduated from your degree at UTS in 2003, how do you feel about that time now? What was the experience of studying in Sydney like?

MELISSA LIANDO

It was great! And maybe a lot of local and international students feel the same way now. I lived in Indonesia until I was 11, which at that time was less free and less democratic under the dictatorship of Suharto. Coming to Sydney as a child was a liberating experience. I was excited to discover SBS - a publicly funded TV channel that plays world movies and world news. For me it was the first place where I got to explore things. To see what a working city with good public space is like and to be exposed to different ideas because you have freedom of speech was great. And it was nice to be encouraged to have your own voice; to find out that learning is not so much about memorising things but understanding processes and understanding how things work. During university I used to spend hours after class just walking around in the city. I think it had a big impact on how I grew up and also how I think today.

CN

Although completely different circumstances, that exploration of the city resonates for me. I moved from regional Australia to Sydney to study, and up until that time I’d only spent a handful of days in any city. Living in a city for the first time I was struck by the raw variety of it: all the different types and ages of buildings and atmospheres of places. And I think exploring the city was, in a way, what led me to study architecture. Did your experiences in the city contribute to you going on from interior design to architecture?

ML

I think the inkling or the curiosity about architecture was always there, it just maybe wasn’t formulated enough. Taking walks, being a flâneur almost, and then travelling and seeing different places contributed. When you travel you experience not just physical environments but people: culture, society and individuals through chance encounters. And then through all this I got to see architecture’s capacity in shaping the city, in shaping place - its capacity to contribute to culture and create change.

22

CN

For me, the mindset you find when you’re travelling, of seeing everything anew is important. You’re more receptive to the beauty of things as they are. I think as architects we can find ways to make sure that outlook comes into everyday life, in familiar places.

I think that your Kineforum Misbar project did that really well. If I understand correctly, that was a project you initiated yourself: to create a temporary, open-air community cinema in collaboration with a local cinema in Jakarta. In that project there is an almost utopic, student mentality of how architects can be activists in their city. What was your motivation for the project, and where has it led you?

ML

It was great. We were new to the city at the time. I had lived there until I was 11, and returned 17 years later after living in Sydney and Europe. One of the things I first noticed was how limited public spaces were. We found that there was only one little cinema that played world movies and independent films and we became very interested in their programme of activities. And so I wrote a simple email. I didn’t know them, they didn’t know me. We wanted to propose an idea that could help promote their work and also explore the idea of an open air cinema.

This is an idea that has been around in Jakarta for a long, long time. You have this thing called Misbar, which loosely translates to ‘drizzle and disperse’. It is a very communal way of seeing a movie, mostly for lower income people. You would have these travelling cinemas that would be erected for a few days within city centres or villages. I grew up seeing them around, but it has completely disappeared now. So it was really nice to bring that idea back. And one of the first things that we decided from our very, very first meeting was that it had to be free and it had to be in the city centre.

For both parties, we had never done anything like that before. We were clueless in a way, and maybe somewhat naïve about how we could get that going and how to get funding because there was no commercial aspect to it. But they were very, very open to the idea and they were very supportive and right away they said, ‘Yes, we like it, we should do it!’ It really just started from that. Then it took a year actually from the first initial meeting to when it was built, because it took a lot of convincing of people to let us do it basically.

We wanted to do something where we could bring people together and also in our own little way bridge the gap between the rich and the poor; to allow the possibility for a certain section of the community who would have otherwise never had this opportunity, to have it. To get something like that built quite fast, seeing your project built in the city centre,

23 CONVERSATIONS

CN

that was an amazing experience. But the most, even more, amazing experience was to see the people using the space. Young and old and those that are more well to do and those that are not. I remember there was this local informal garbage collector who was trying to watch the movie from the outside, because we had these transparent screens so you can still see it from outside. But he was pulled in, to come inside. It’s not something that you see every day or you can do in another setting. So that was probably the best experience out of it.

I can imagine that would have been such a rewarding feeling! On a much, much smaller scale, I helped out with an installation of students’ work here over the mid-year break. It was very simple and very short, but as you say there was a thrill in actually seeing people using a communal space that you’d put work into. And it was encouraging for me that, without lofty theory or grand scale, a project creating even the smallest moments of community could be so rewarding.

At university a lot of our projects are focused around social causes or cultural initiatives and then sometimes there’s a gap between that and the work we find ourselves doing. How do you think about the role of an architect in contributing to a place? And if being back here in Sydney now, are there ways you are seeing the city differently?

ML

I think coming back to Sydney now, coming back during Covid, was a strange thing. But having been abroad you can’t help but compare the good and the bad. So the good thing, especially coming from Jakarta, is having all this space! There’s so much space and there’s so much public space as well. It’s really, really great. And then ‘the bad’ I see is actually the state of housing in Sydney. Especially how social housing is dealt with. It is so different from Europe and it could be so much better. Again, you can’t help but think that if you’ve lived in a city which addresses that issue in a better way. You can’t help but compare and ask questions. Why can’t they do it like that in Sydney as they do it in Holland, let’s say? So, the state of housing and social housing, which in Sydney seems to be perhaps more developer driven is something that surprised me. But I’m still finding these things out, exploring and analysing.

CN Yes, it’s good that there’s some momentum around the renewal of public spaces and cultural institutions in Sydney, but then there’s a whole other frontier tied up in issues like social housing. The life of the city away from its big, glamorous cultural markers. I guess it’s important to think about pushing for a vision of the city on multiple fronts.

24

ML

I would say for architecture students it would be good to see that as architects, you’re not just facilitators. You can be vocal and you can be vocal by initiating things. And it will be a learning process! Because you learn different things in uni and you’ll meet different people later on who will work differently from what you are used to. But give it a chance. Working in an interdisciplinary way, you can learn a lot. Not just in terms of working at different scales but working with different professions.

But my general advice would be to just listen. Listen with your eyes and ears and be open. See things, notice things whether you are travelling or you are in your usual environment. Sometimes at the beginning of your career you’re not necessarily part of certain conversations but you should still listen and try to learn from what you hear, especially if it’s from people who may be affected by what you do.

Melissa Liando is an architect and one half of the multidisciplinary design office, Csutoras and Liando. Melissa moved to Sydney from Jakarta as a child, and would go on to study Interior and Furniture Design at the University of Technology Sydney. After then completing her Masters in Architecture at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, she has since practised in the UK, Indonesia and Australia. She is now back in Sydney, and teaching design studios at the University of Sydney.

Caleb Niethe is a graduating Masters of Architecture student. Caleb moved to Sydney from Woolgoolga, on the mid-north coast of New South Wales, for university and completed his undergraduate architecture studies at the University of Sydney.

25 CONVERSATIONS

Master of Architecture

Introduction

Paolo Stracchi Master of Architecture Program Director

I don’t think architecture school teaches you to be an architect. It spins you around and points you in the direction of architecture. The individual is the only person who can finally become an architect. Nobody can do it for you. You’ve got to do it yourself.*

John Andrews

This is a particularly exciting catalogue for us as it includes the work of the first graduates of our renewed Master of Architecture program, proudly launched in 2021 and conceived with a simple aim at its core: ensuring that the education we give is the most cutting-edge and intellectually rigorous. And so, in the past two years, working together, academics and practitioners have designed and coordinated more than thirty new design studio briefs which have allowed our students to sensitively explore different areas of architecture and play with their creativity to investigate alternative, radical solutions for the future of the built environment.

To our graduates. With your projects, you have attempted to critically reshape our cities and their surrounding landscapes; in so doing, you have also consumed materials and land. You have burnt precious energy in the name of placemaking and sheltering. But, and I am sure of this, you know the impact of your designs on our country and planet. I am confident, as I know in your studies you have been provided the best possible design skills to tackle the evolution and the contemporary significance of the profession of architecture. The results presented here are vivid testimony to being spinning around and encouraged to test new ideas and explore new methodologies and tools, and ultimately to demonstrate your abilities. Your final design projects give us great confidence that we have pointed you in the right direction: architecture is indeed shown here as a wonderful assemblage of poetry, science, and imagination, which has forged socially, economically, and environmentally conscious solutions.

You’ve made it! But wait a second: is this enough? Do you know all you need to know now? Really, you don’t – becoming an architect, as John Andrews (1933–2022) told us, will depend on you alone; I can assure you that it will not be easy, but here’s something to hold on to:

“Don’t forget what happened to the man who suddenly got everything he wanted.”

“What?” asked Charlie. Wonka smiled: “He lived happily ever after.” Congrats to all of you on your final studio.

29

*Barry Simon interview with John Andrews, 1985. Source: State Library NSW, John Andrews architectural archive, 1951-2004. MLMSS 10302.

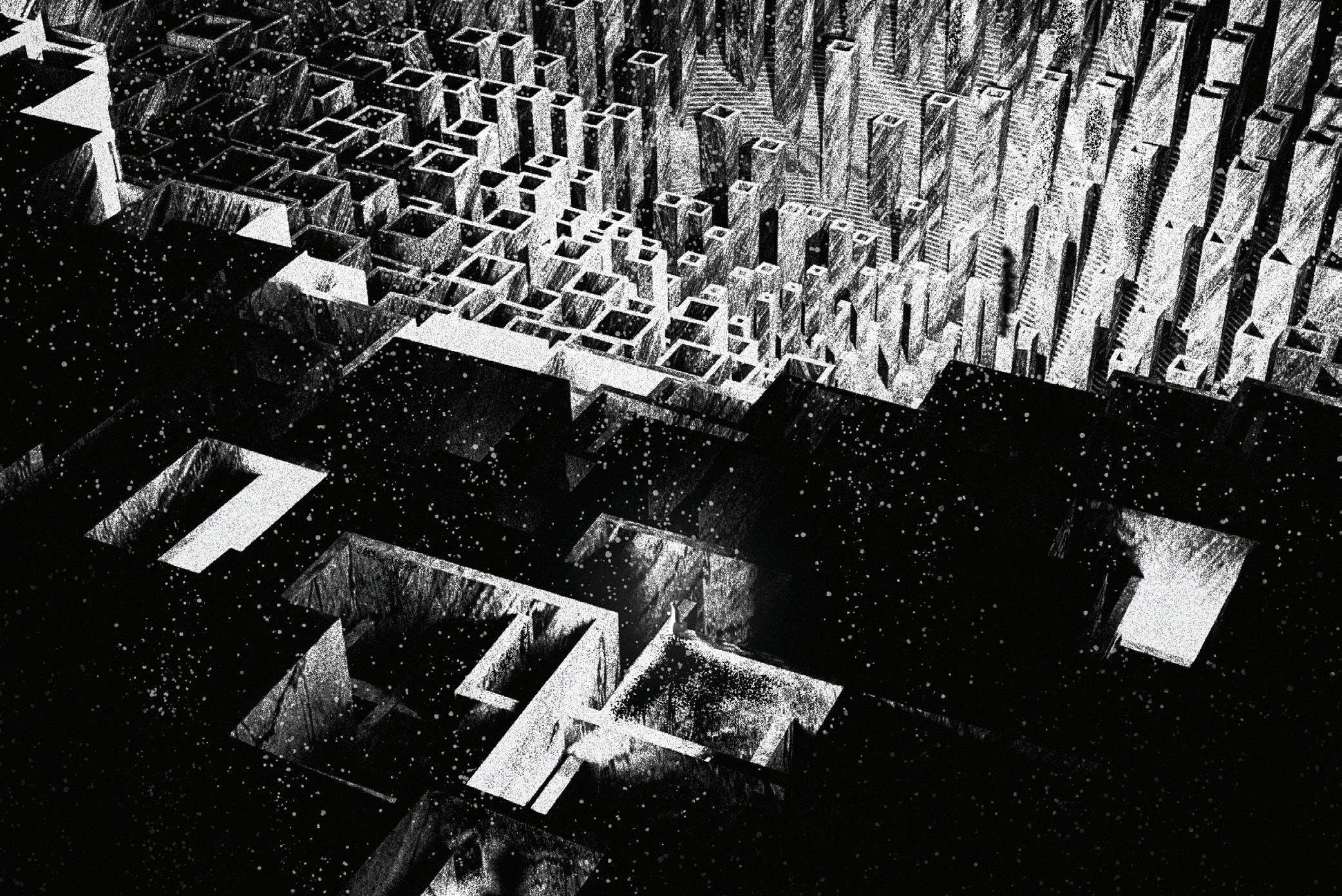

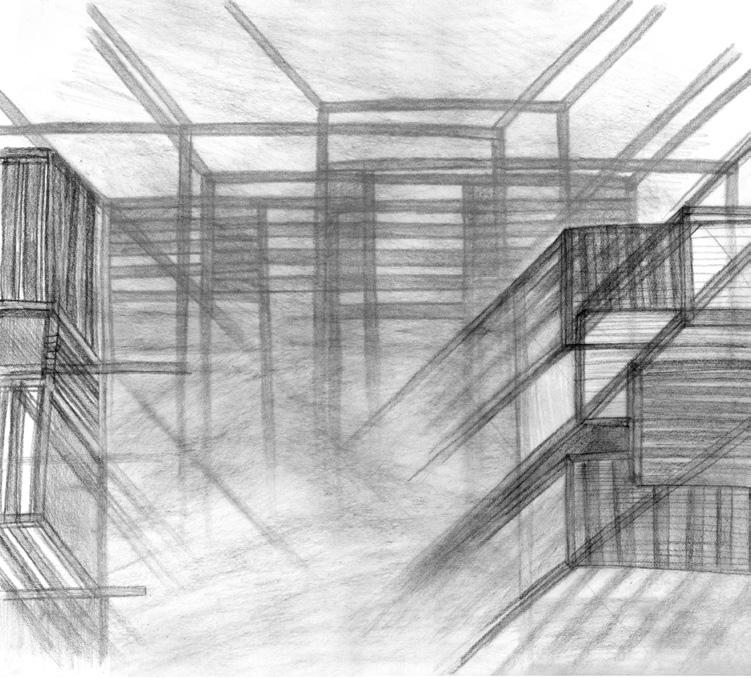

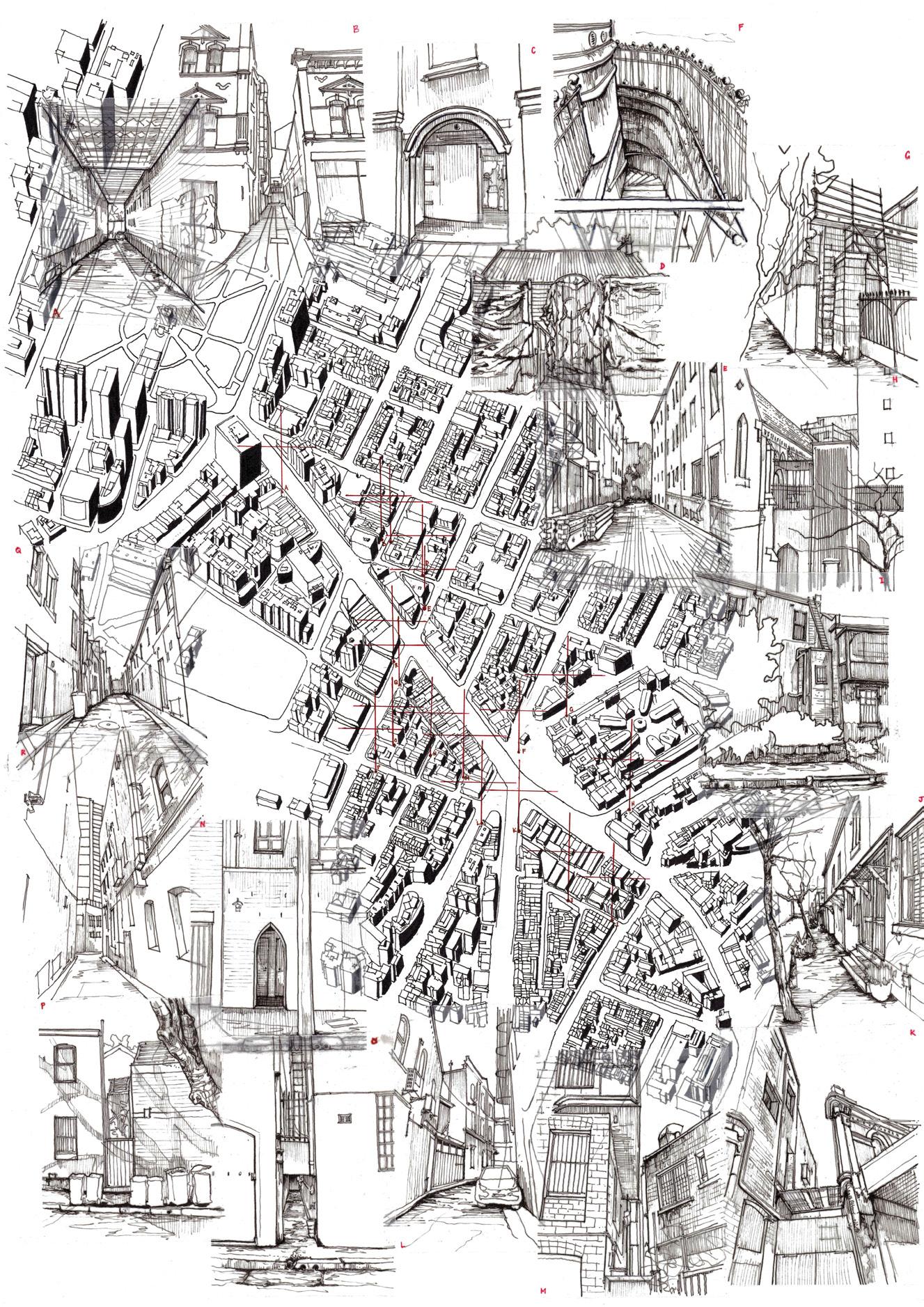

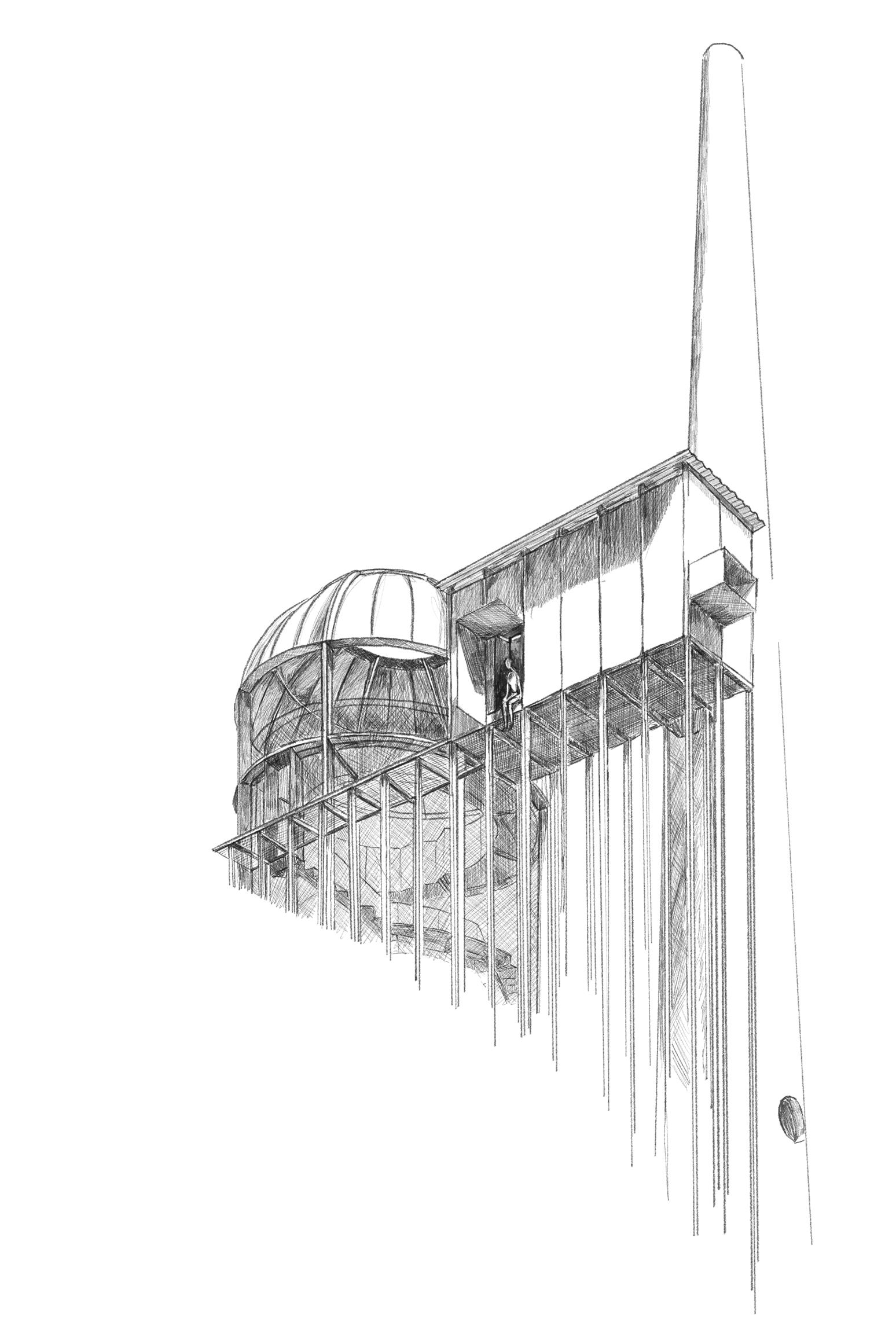

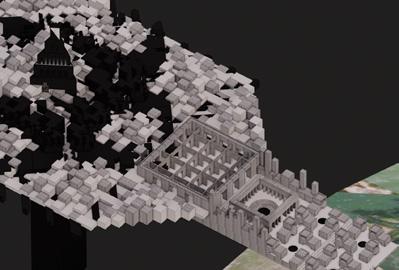

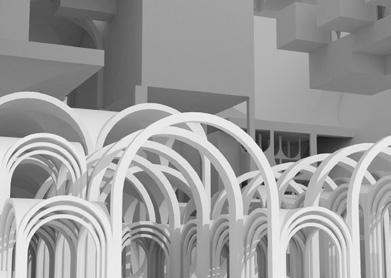

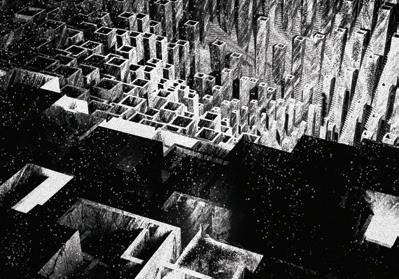

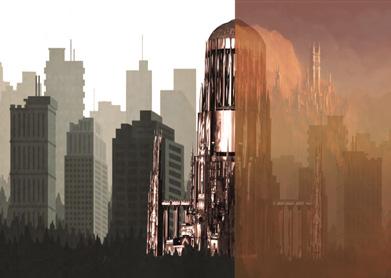

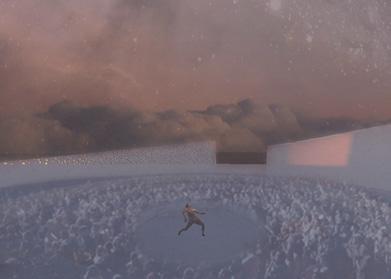

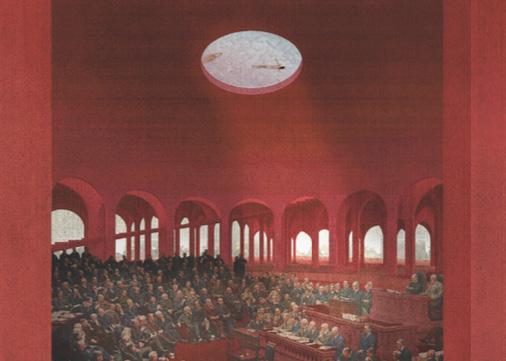

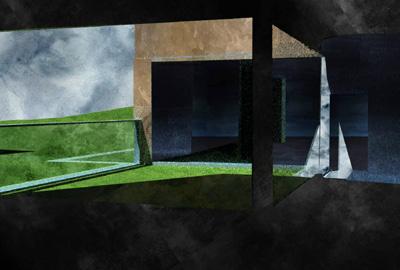

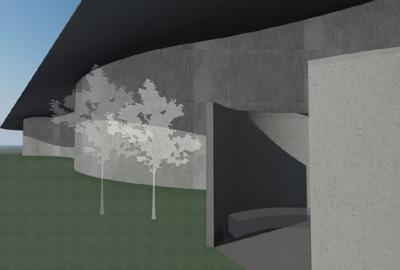

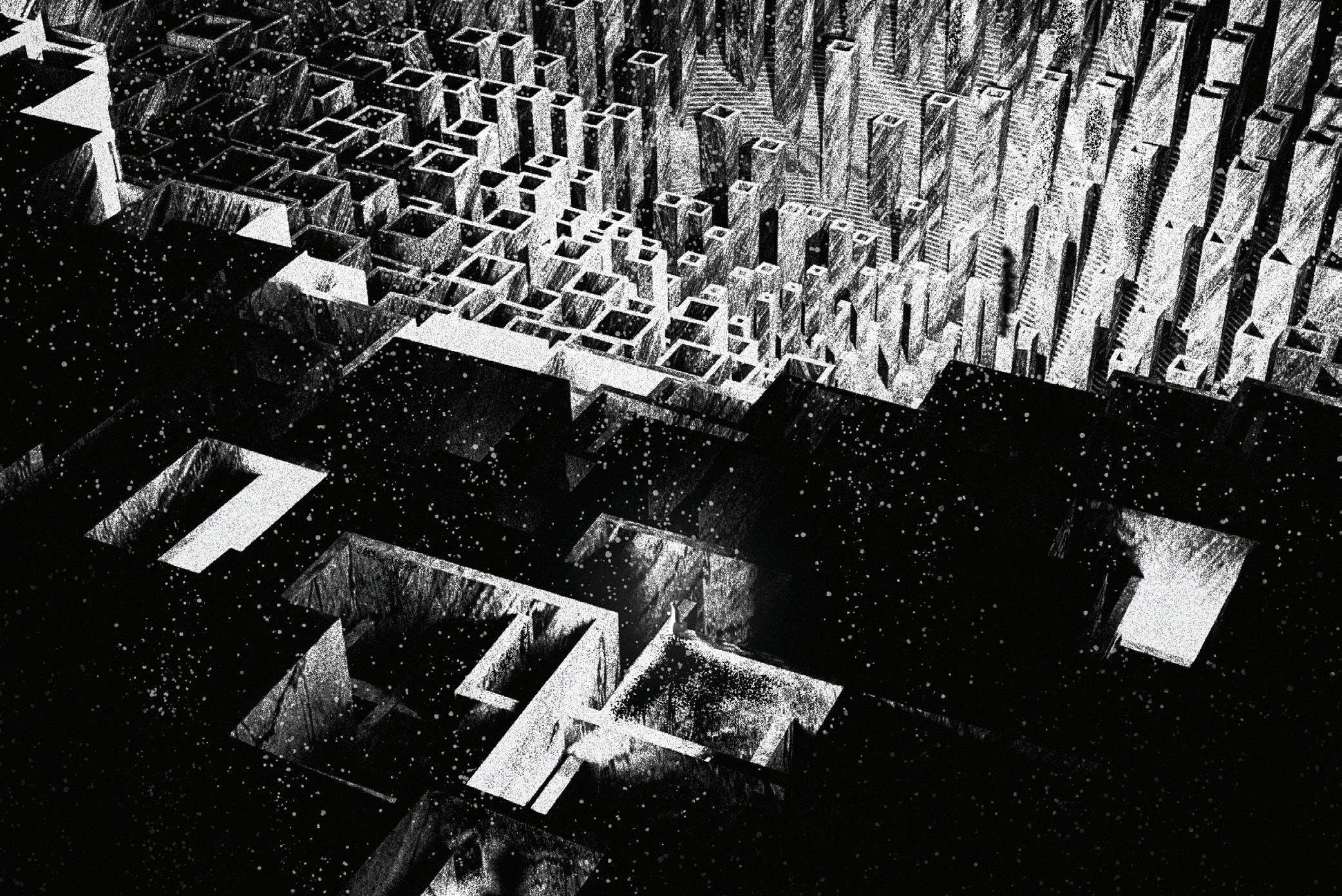

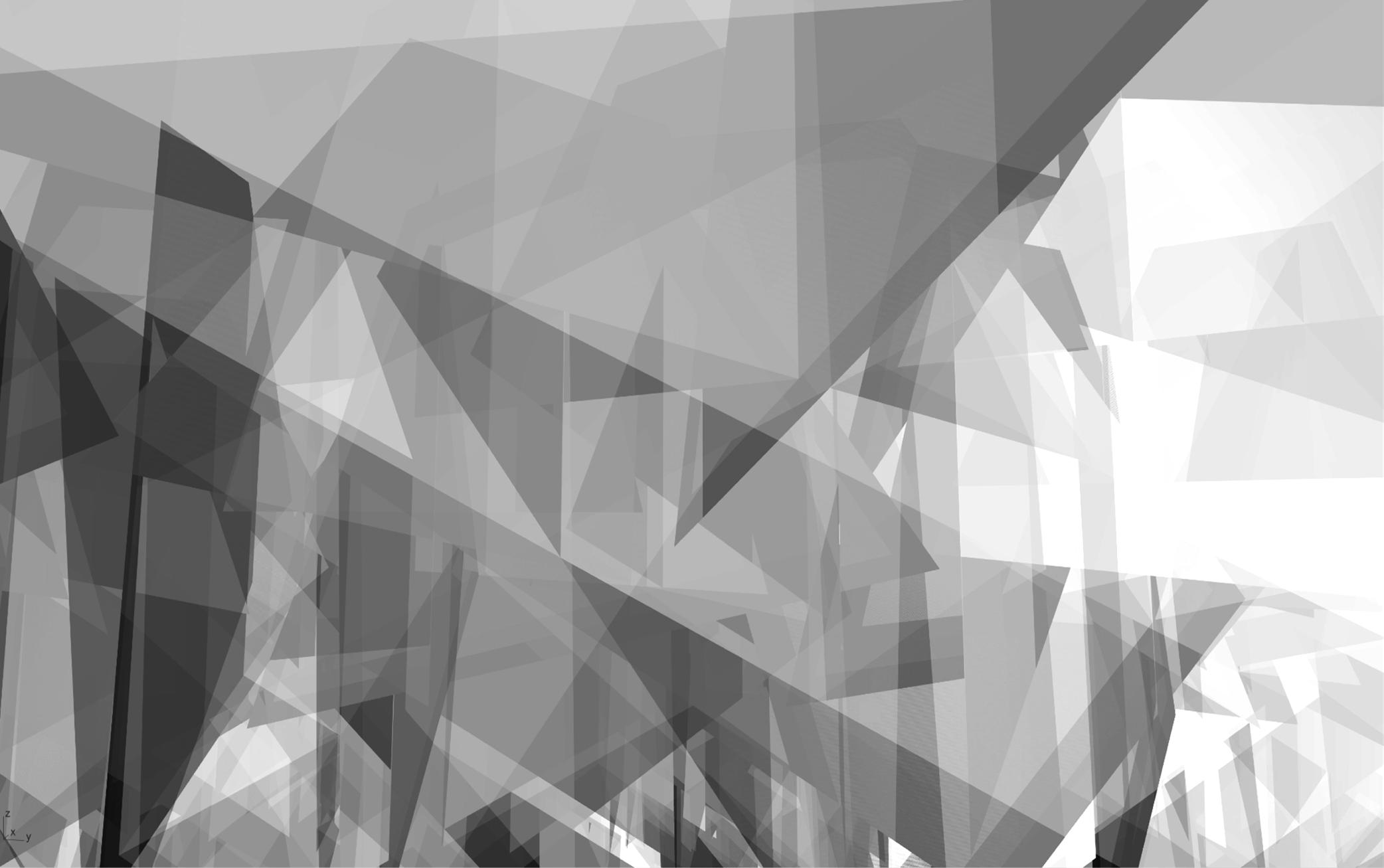

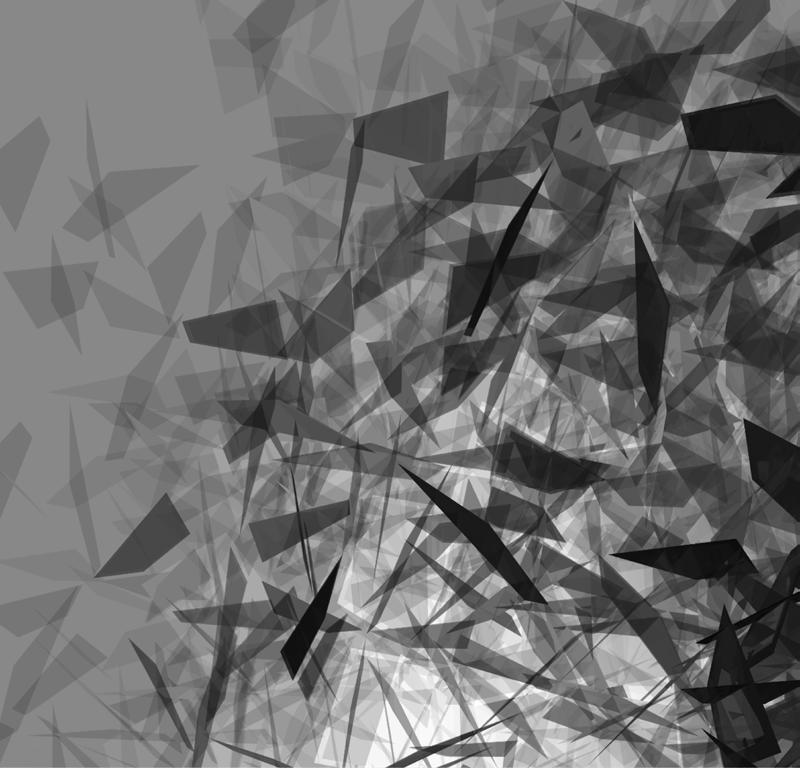

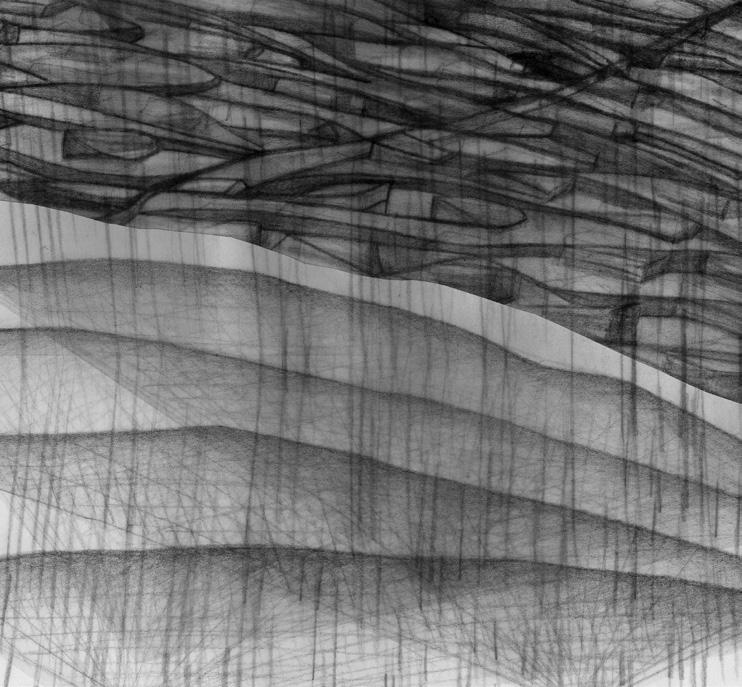

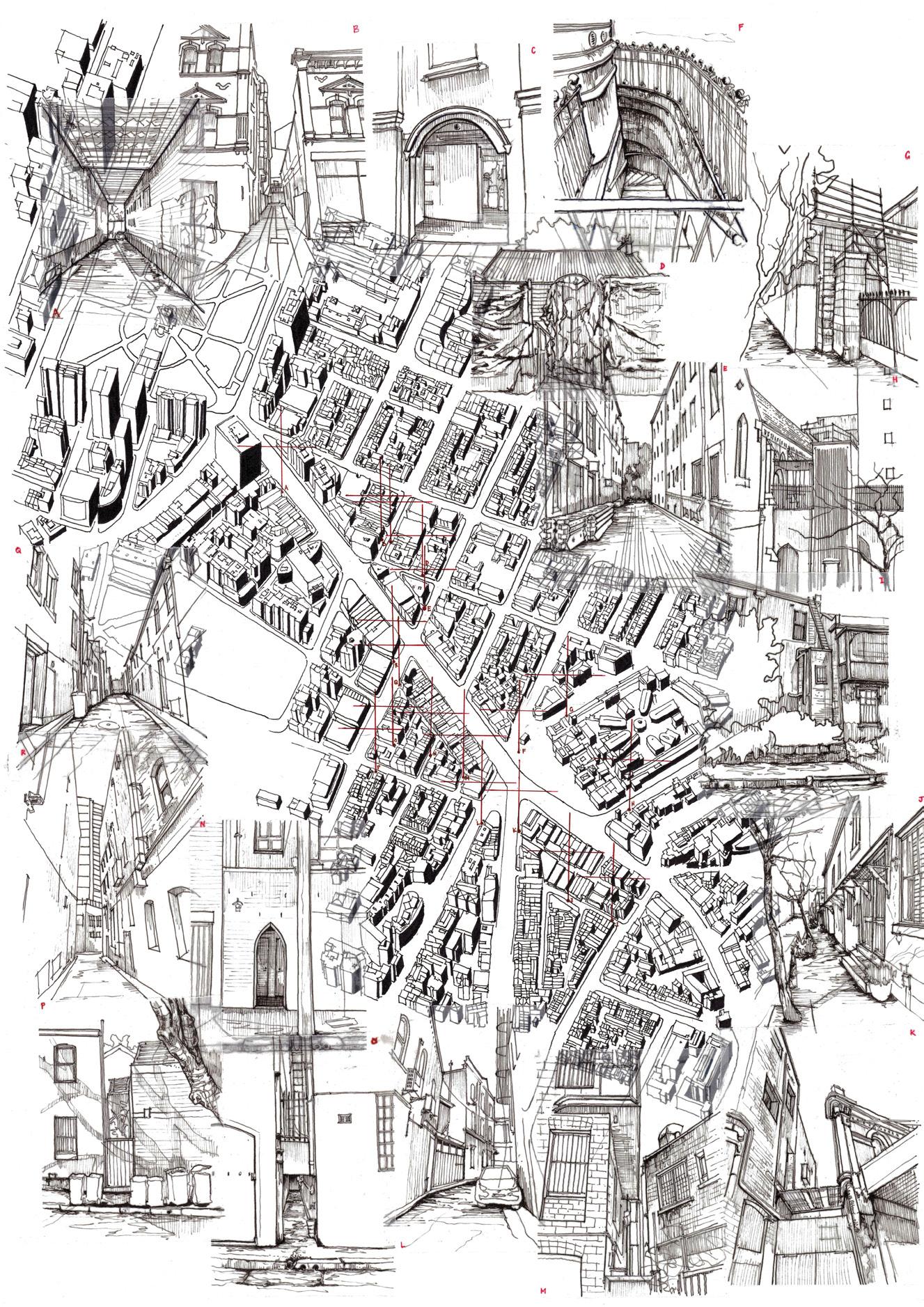

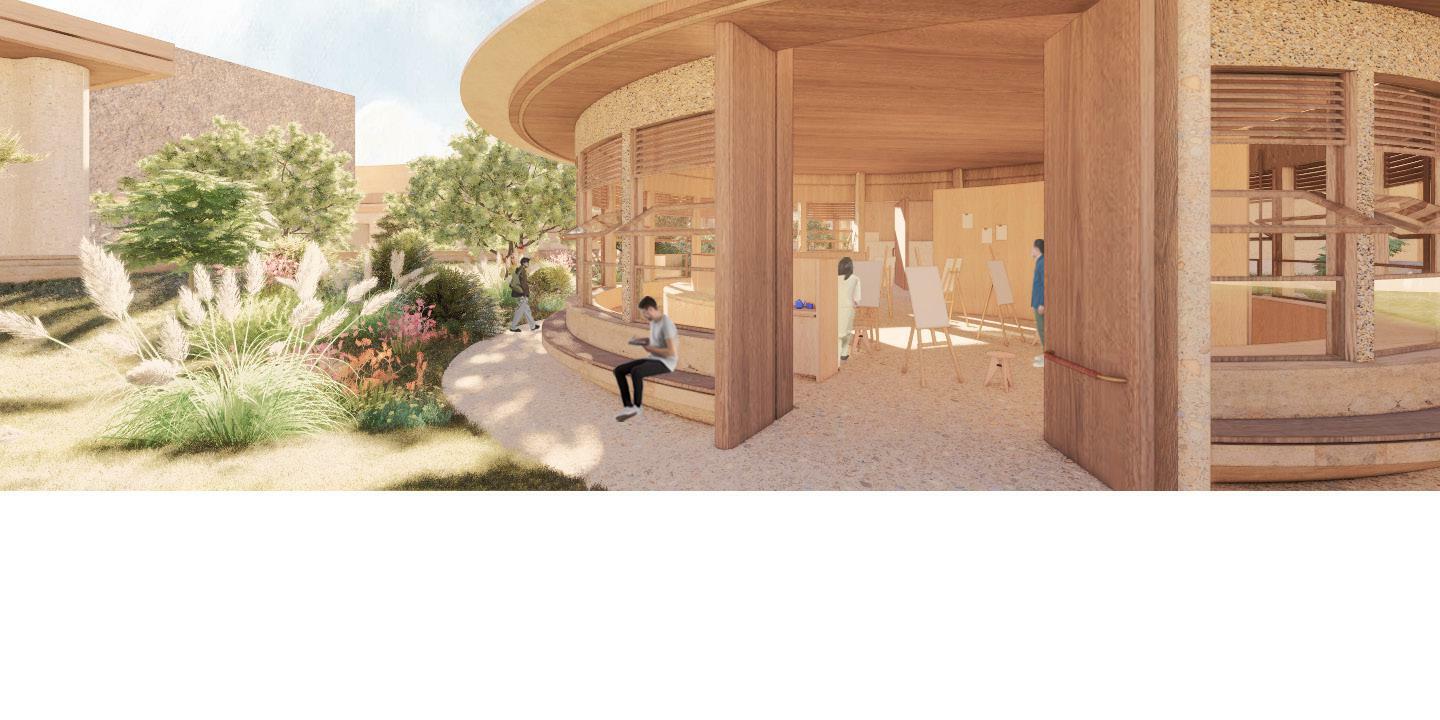

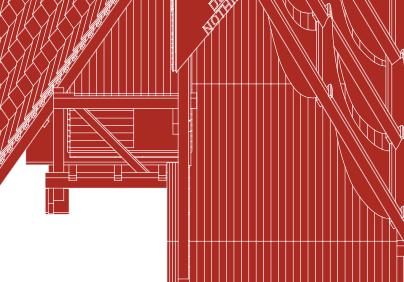

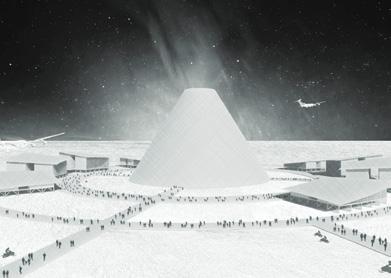

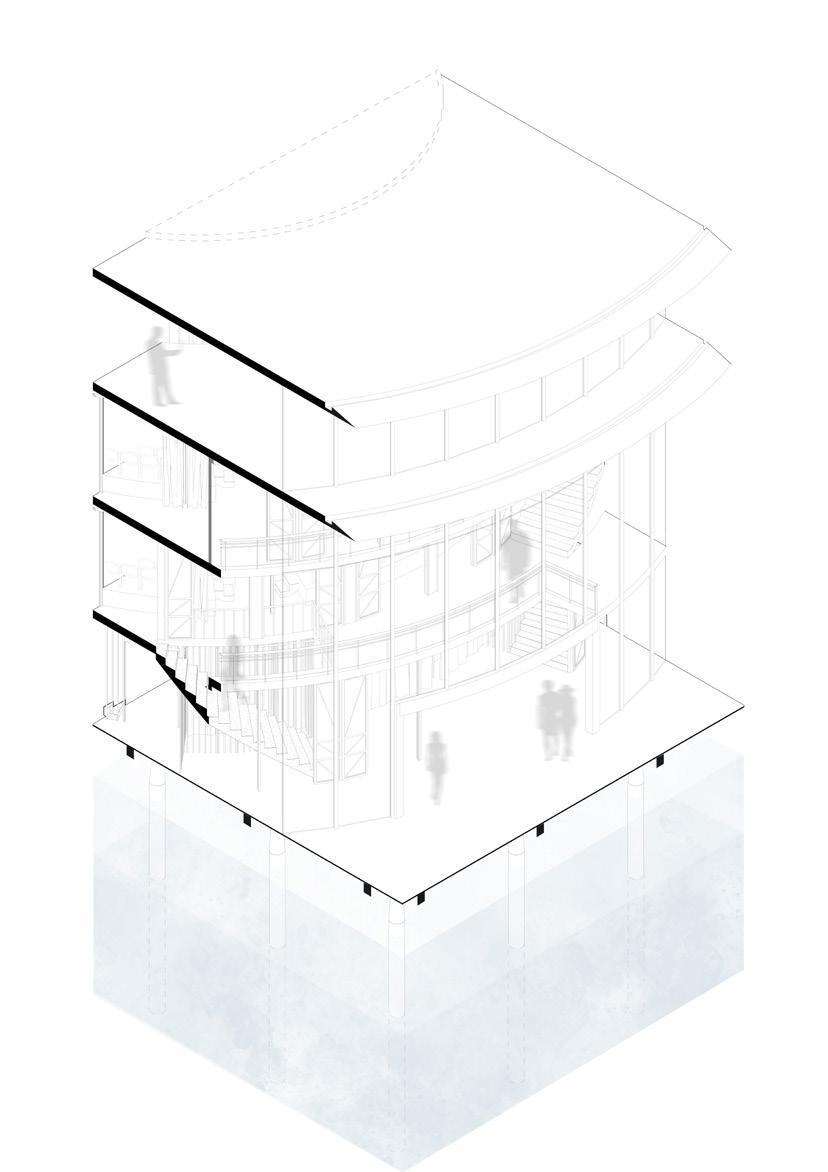

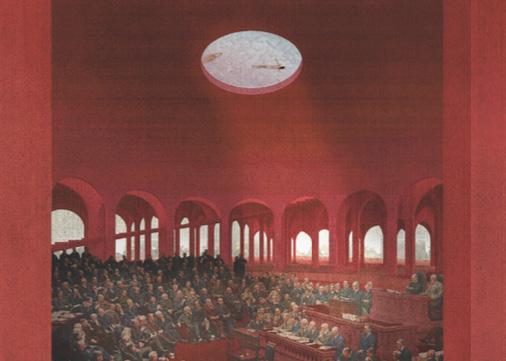

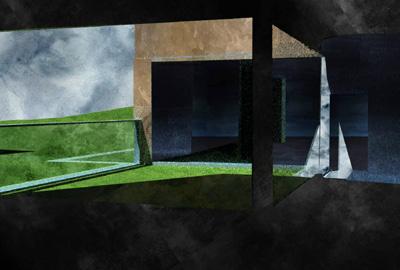

Imagining Kafka’s Castle

Franz Kafka’s (unfinished) novel, Das Schloß (The Castle), published in 1926, follows a surveyor, K, who understands he has been commissioned by regional authorities ruling from an ominous, prescient castle that dominates the village in which he finds himself entrapped. The studio imagines, projects and ‘completes’ the castle—construing its tectonic and atmospheric conditions. K never reaches the castle, and the structure is never fully described in Das Schloß. Hence any indications of its architectural configuration is inferred from occasional episodes and fragments throughout the novel.

These are gathered from implications drawn from at least three aspects of the novel:

• explicit descriptions of the castle itself—generally of its external aspect in the landscape and village setting;

• explicit descriptions of rooms, streets, buildings and other architectural features of the village K finds himself in;

• the circumambient mood of the novel, evident, for example, in the observations, relationships and dialogues (spoken and unspoken) that transpire between characters— specifically between K, the villagers, and representatives of the authority of the castle.

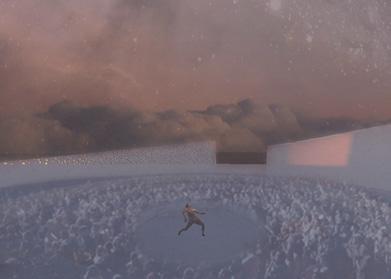

The studio presents the circumambient mood and atmosphere of Kafka’s castle, using a variety of techniques and media including animation, video, rendered drawing sequences and a portfolio. The aim is not to design and document a building but to imagine and convey, as accurately and precisely as possible, the haptic and experiential tectonics that characterise the novel’s setting and, at another level, the human condition envisioned by Kafka.

External contributors and critics:

Vesna Trobec, Studio Trobec

Stanislaus Fung, Harvard School of Design

Kate Goodwin, USYD

Guillermo Fernández-Abascal, USYD

Catherine Lassen, USYD

Ross Anderson, USYD

Matthew Mindrup, USYD

Chris Smith, USYD

30

Architecture Studio 3 Michael Tawa

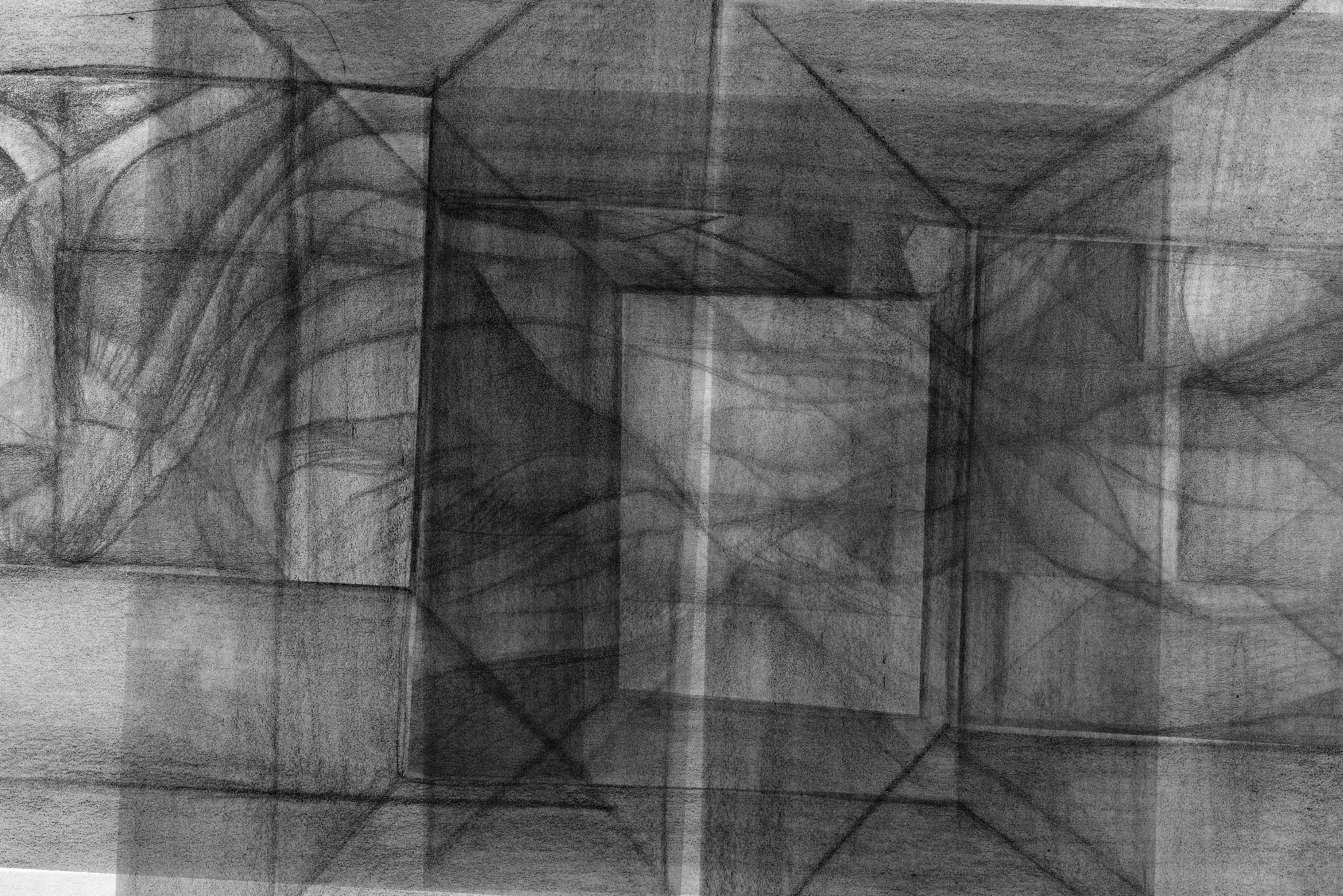

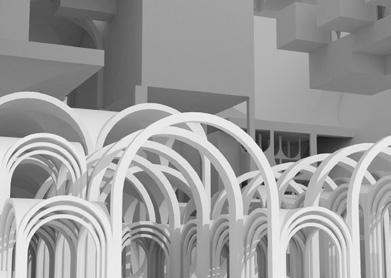

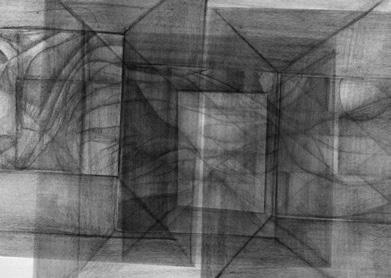

The Cage of the Heart Meichen Pan

Kafka’s The Castle depicts an actuality controlled by ridiculous rules. The entire castle is a reproduction of a panopticon system based on an authoritarian regime, permanent supervision, and everyone’s contribution. In this world, our protagonist, K’s attempts trying to achieve his gold are hampered by a series of problems stemming from the ultimate source of power, the villagers’ active internalisation of the rules, and the change in K’s own mind. This project aims to present K’s journey in the castle from a panopticon perspective to explain the concept of the internalisation of power and self-taming.

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

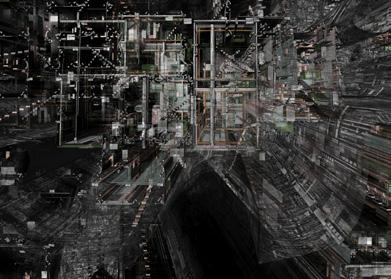

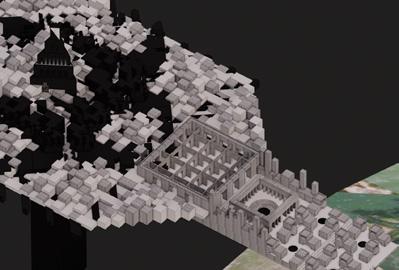

Unforeseeable Intersections: Narrative and Agencement Rebekah Chew

Instead of a single metanarrative, Kafka’s The Castle plot develops through characters being implicated in the lives of others. The novel becomes a series of disjointed scenes, a post-structural narrative. A computation model was built, precisely calibrated to the novel’s characters, actions and scenographies. Kafka’s ‘writing machine’ generates an animated sequence of ambient renders, to bring the novel to life. He was a writer, who lived in his writing, and whose writing became a vehicle for figurative contact.

32

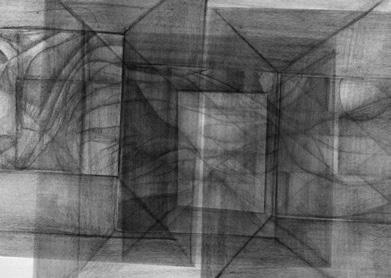

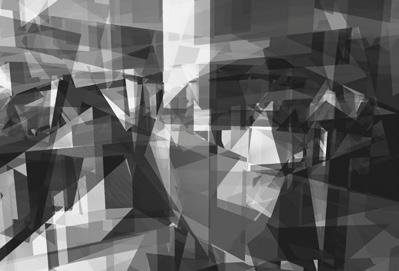

The Faceless Castle Ghounwa Tawk

The project understands The Castle as an interwoven network within the village. This is explored through the landscape, perceived as a rhizome between the ruins of the past and the preservations of the present. The drawings present the thematic framework of the illusion, veil and echo that are prevalent in The Castle. It acknowledges the paradoxes evident in K’s journey and sets out to understand them in a positive light, as traces of proof of the unknown. The drawings evolve through a process of overlaying—open to the possibility of a continual state of emergence. In the same way that the unfinished novel is in a constant state of turbulence and mystery, the drawings result in an exegesis of The Castle

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

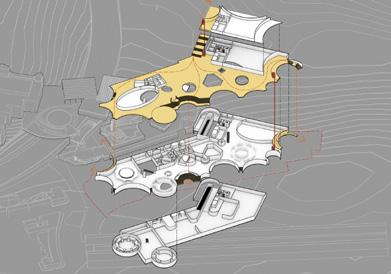

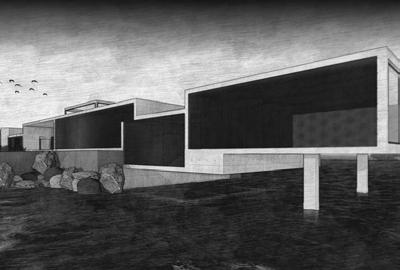

Art Gallery of NSW, 2050: TheatreMuseum of Atmospheric Art

Studio 3 Simon Weir

The visual identity of The Art Gallery of NSW has been long tied to the glorious golden sandstone facade by Walter Liberty Vernon, designer of the Mitchell Library, Central Railway Station and the Anderson Stuart Building at The University of Sydney. Although the Gallery has been renovated several times in the 120 years since, these changes have not altered the public face.

After a century of visual stability, the Sydney Modern project is the Gallery’s largest and most transformative project. An invited competition in 2013, was won by Japanese minimalists Sejima and Nishizawa and Associates (SANAA) with their Australian partner Architectus, and the project opens at the end of the year. Seeing the Gallery engage in this self-transformation, students conceive of the next phase, a yet more radical, 2050 extension with a Theatre-Museum of Atmospheric Art.

In the aesthetic philosophy of object-oriented ontology, all art is theatrical, because we must engage with art to activate its effects, hence a theatre-museum. The object-oriented ontology’s infra-realism insists that art’s illusion of openness is a reminder of the withdrawn closure of reality while acknowledging its presence beneath perception. Artful architecture’s impossible task is making invisible reality appear visible, to help us somehow sense what is beyond sensation.

External contributors and critics: Sally Webster, Sydney Modern Simone Bird, Art Gallery of NSW Drew Heath, Drew Heath Architects Nicholas Elias, Architectus Dr Niko Tiliopolous, USYD

34

Architecture

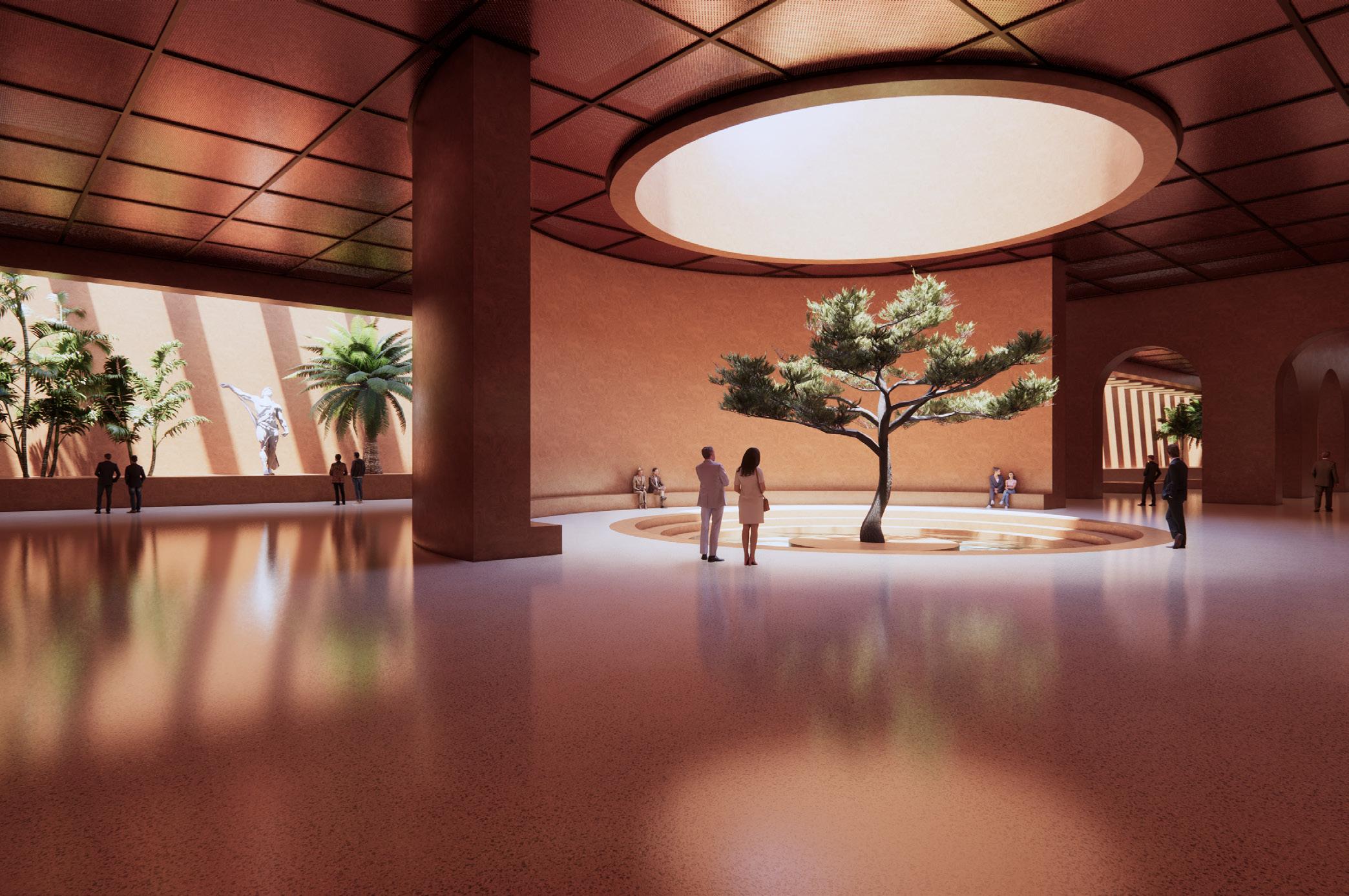

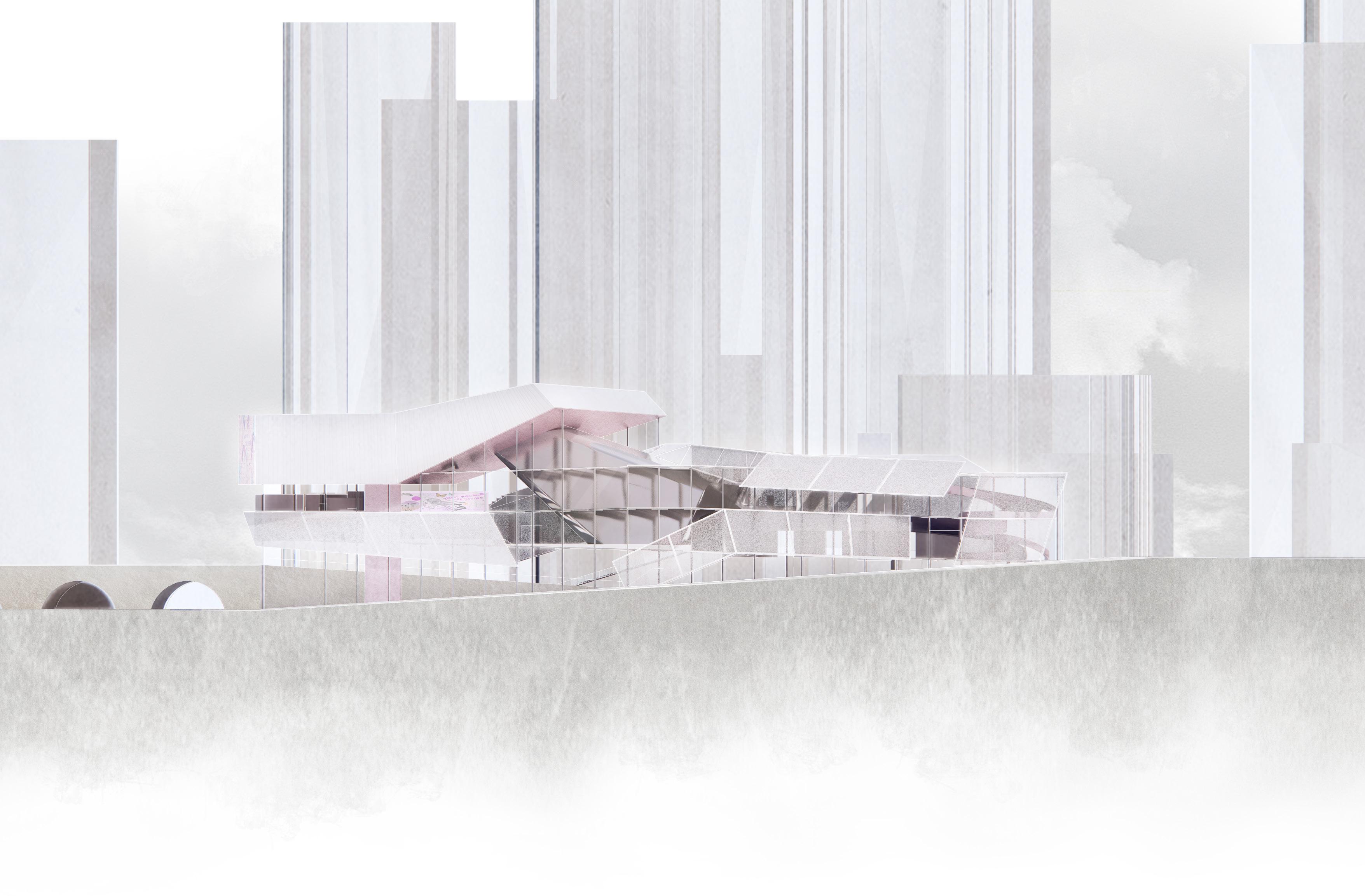

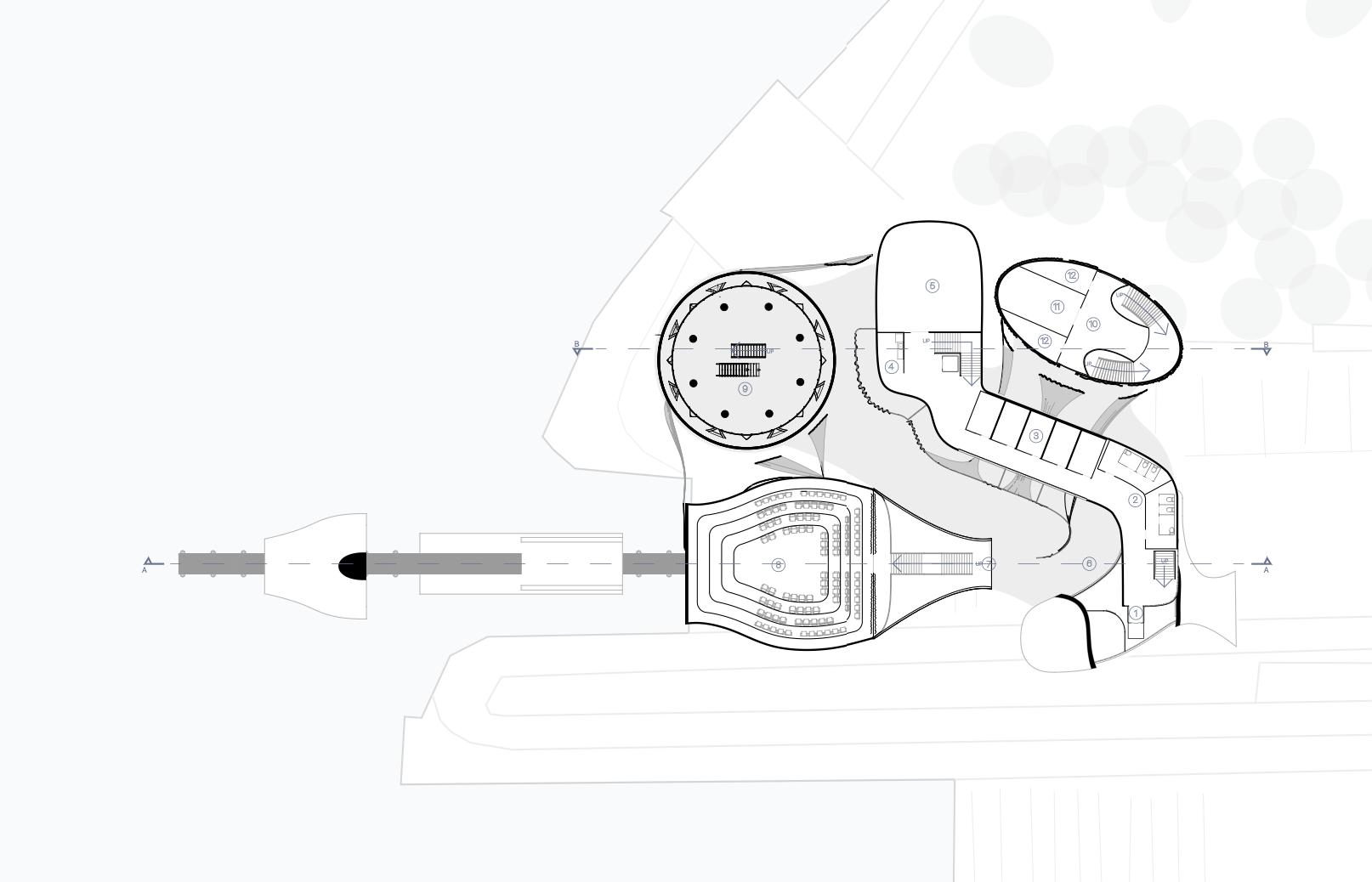

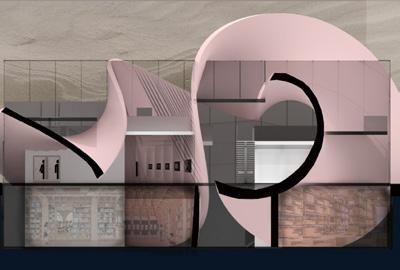

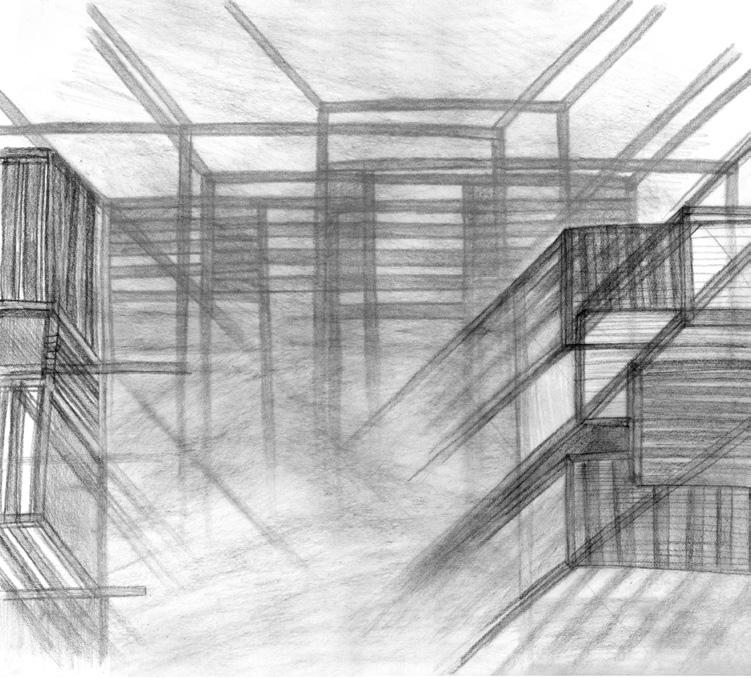

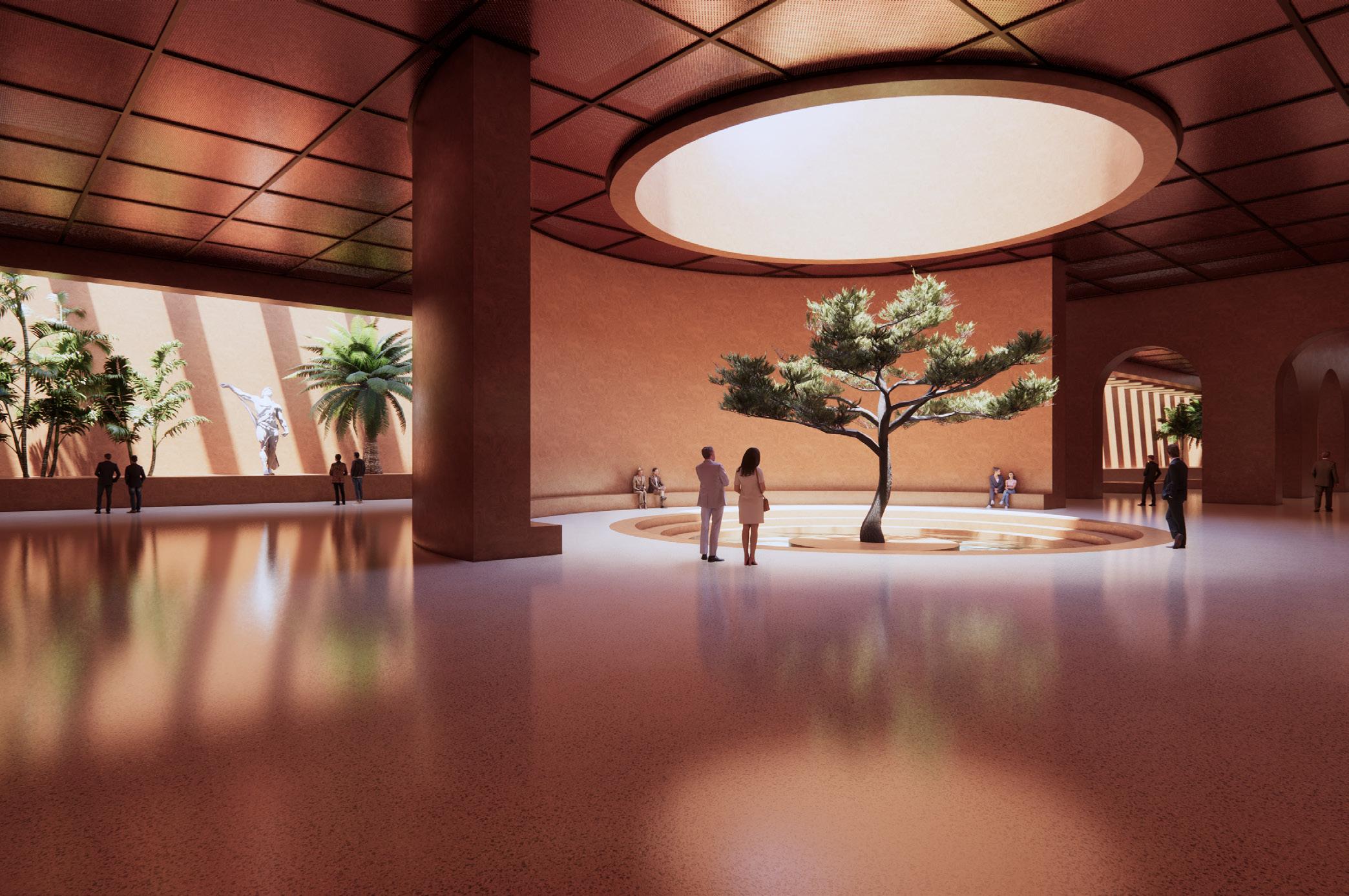

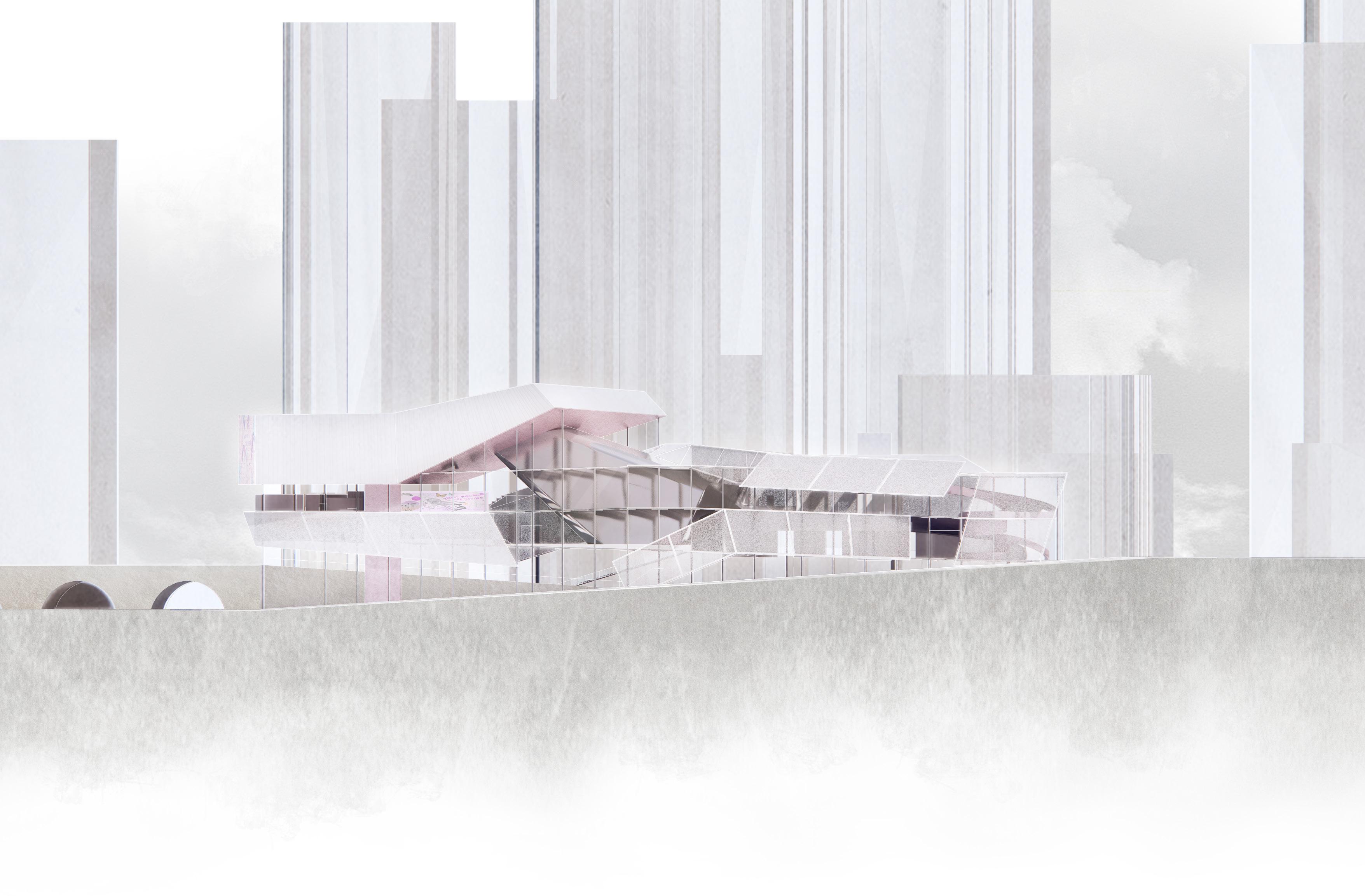

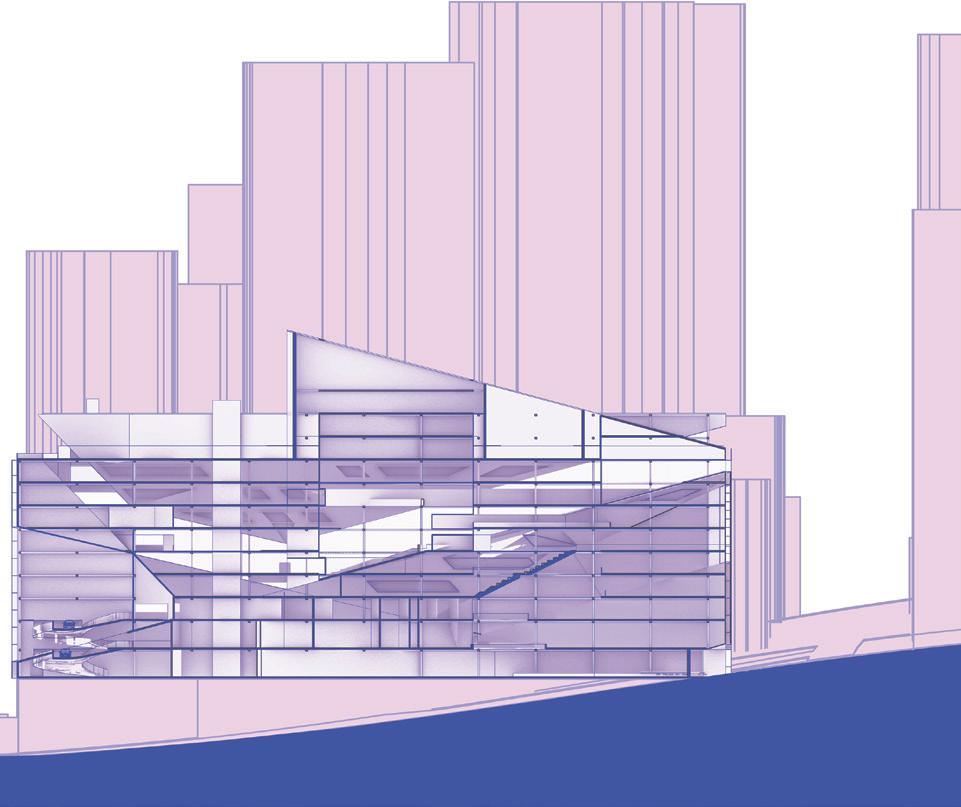

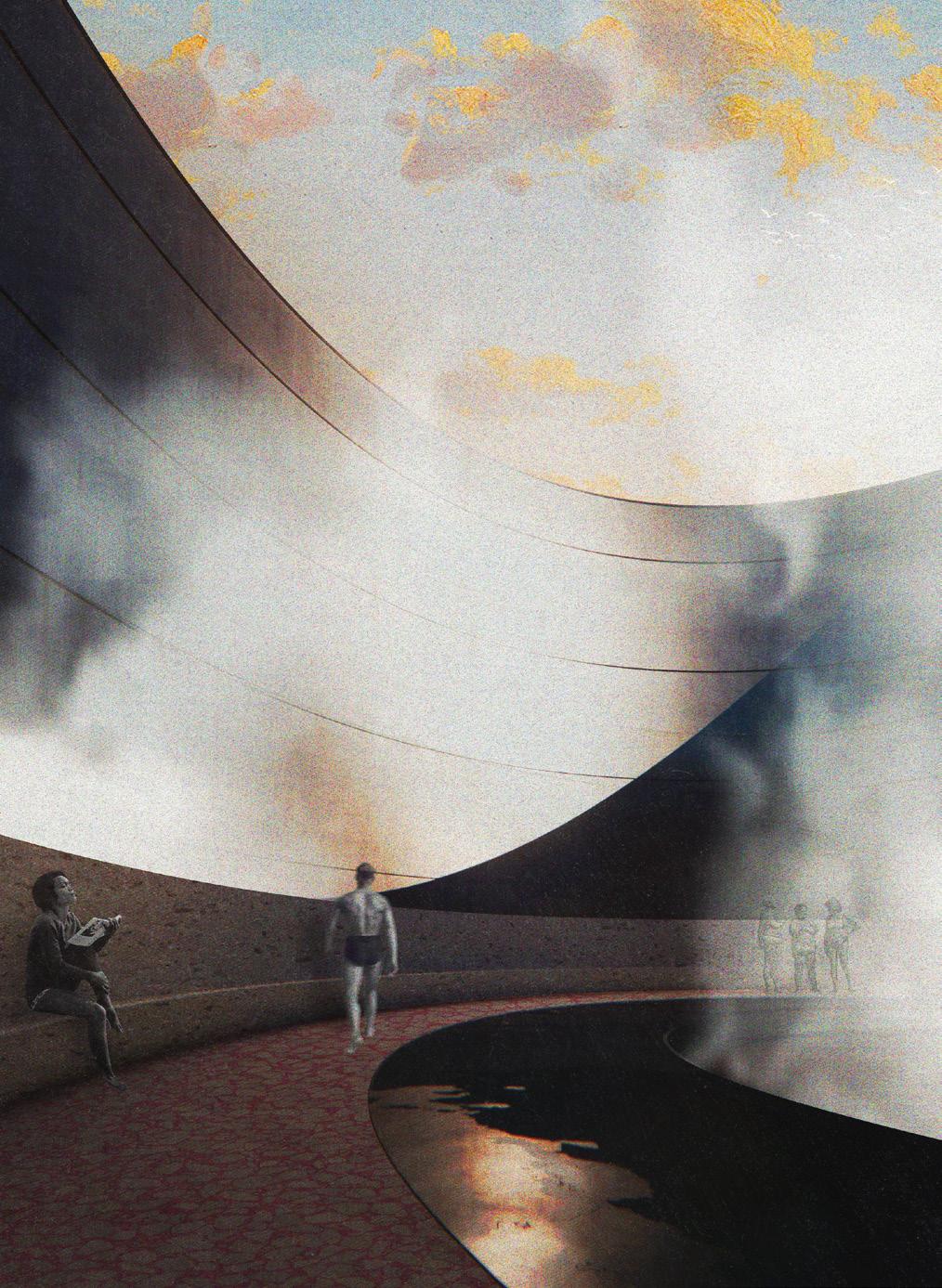

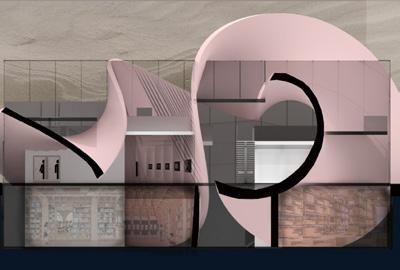

Sydney Contemporary: 2050 Extension to AGNSW and Sydney Modern Rhys Grant

This project is for an extension to Art Gallery NSW and Sydney Modern in 2050, or more specifically, a future unique, special and public gallery experience. Why is this so? In memorable buildings, from entering until leaving, you gain a personal experience. The role of architecture is to emotionally and physically guide you along a journey. To create intrigue, mystery, moments of introspection, and areas for shared experiences. It is an exercise in curating spatial and environmental contrasts. This gallery uses these ideas to remove the viewer from the ordinary and transactional world into a space to celebrate and reflect upon art.

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

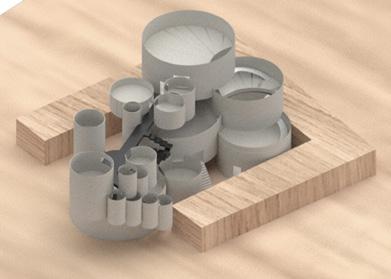

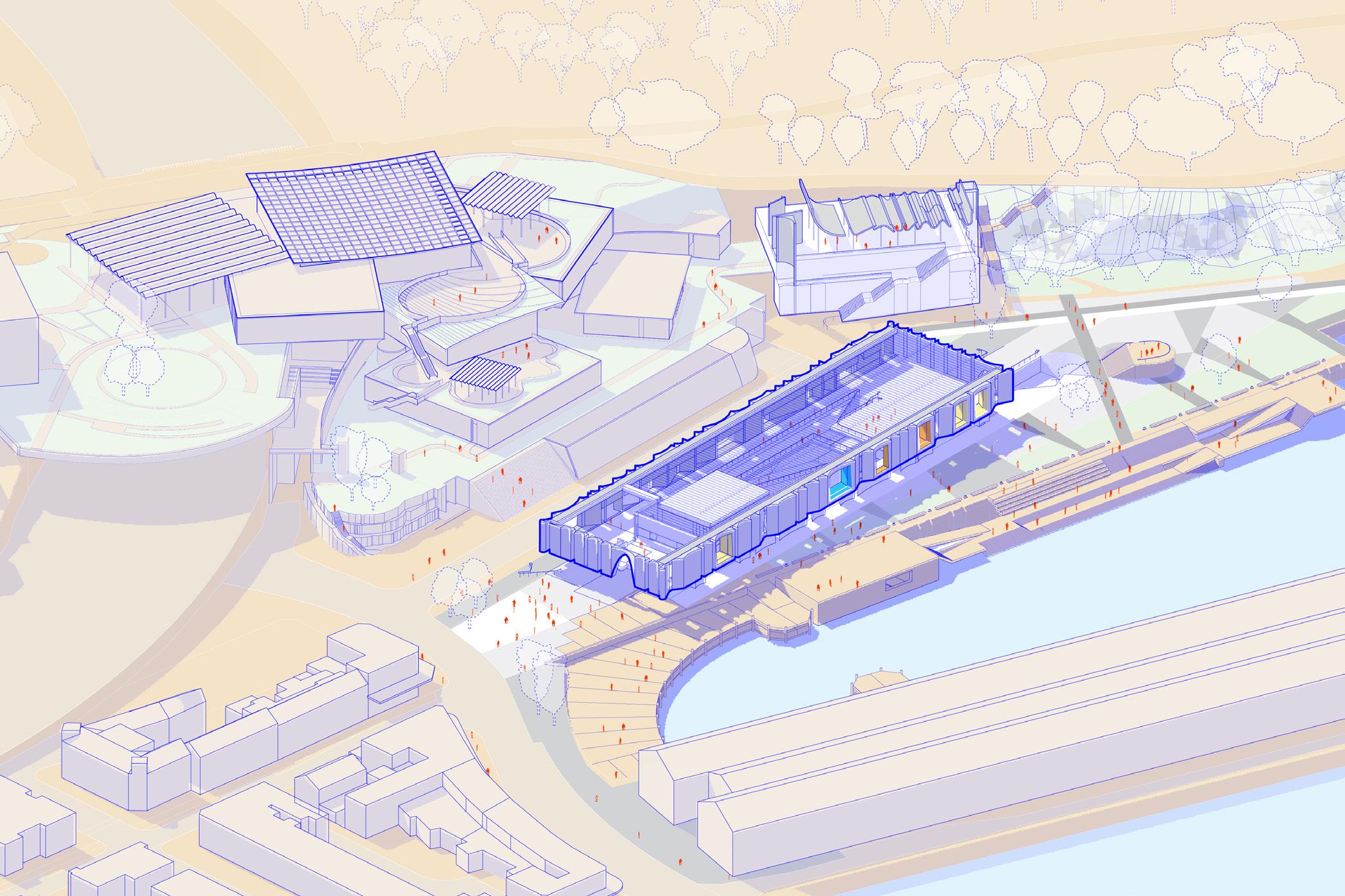

Art City

Alexandra Jablonowska

Alexandra Jablonowska

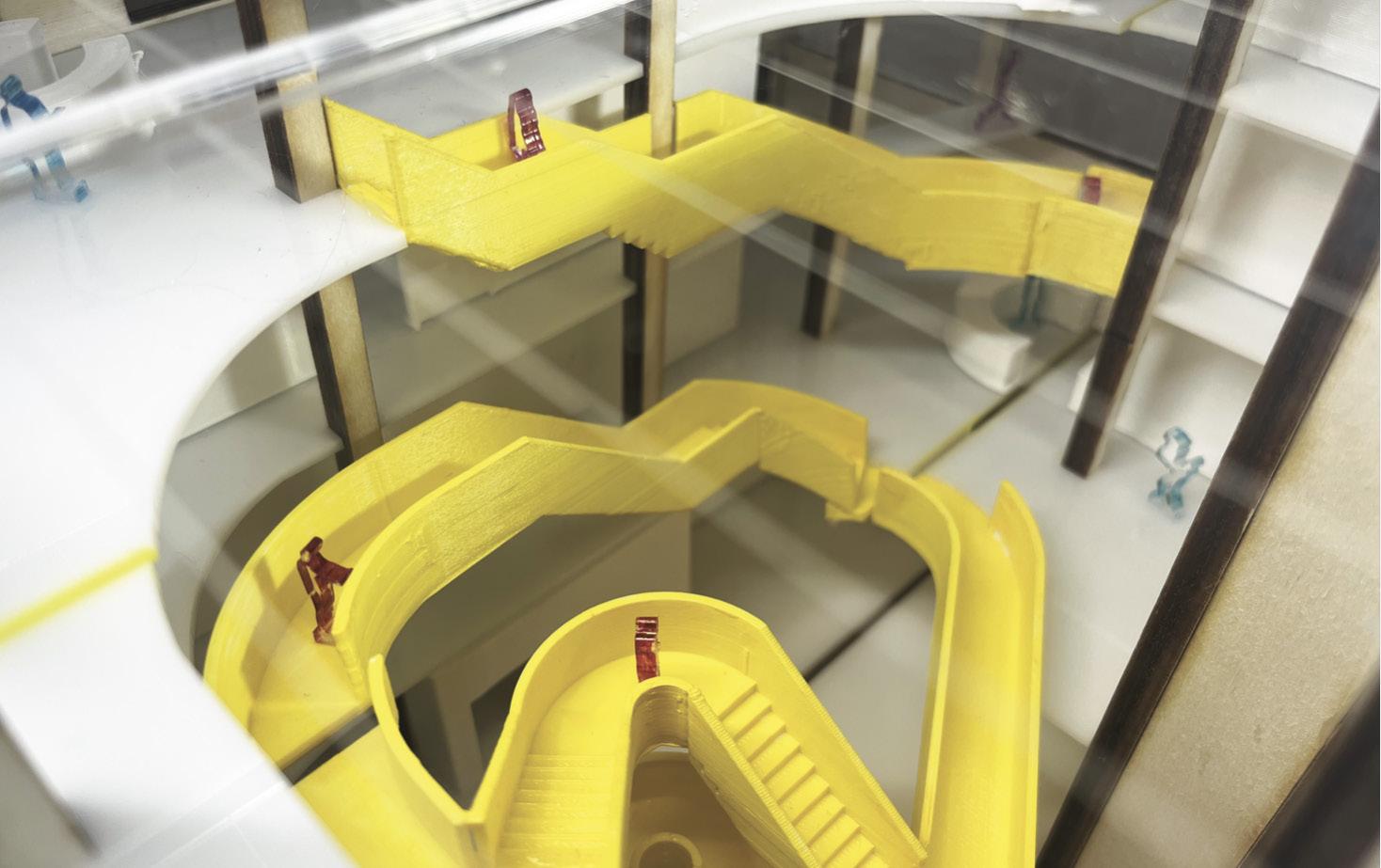

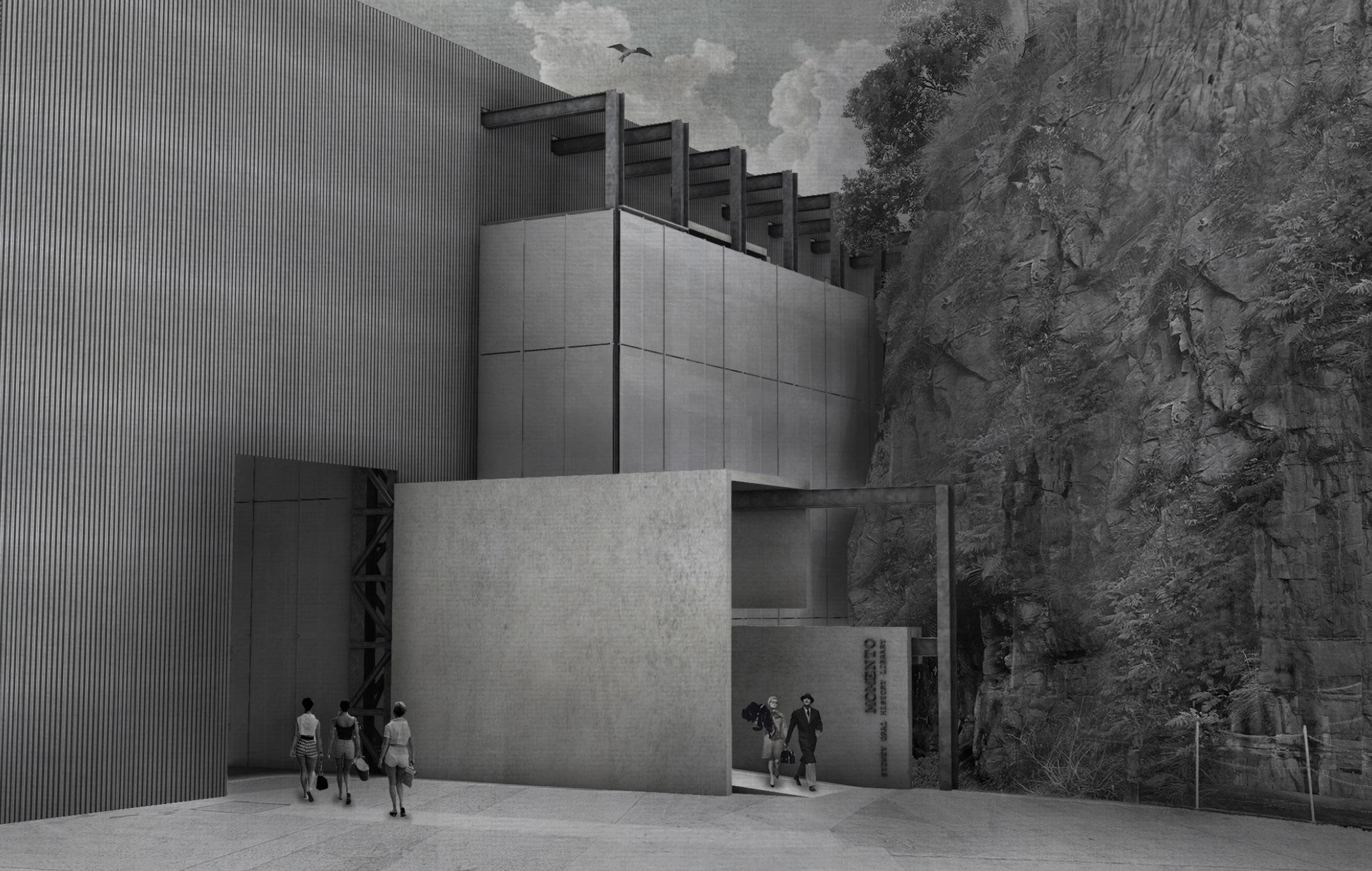

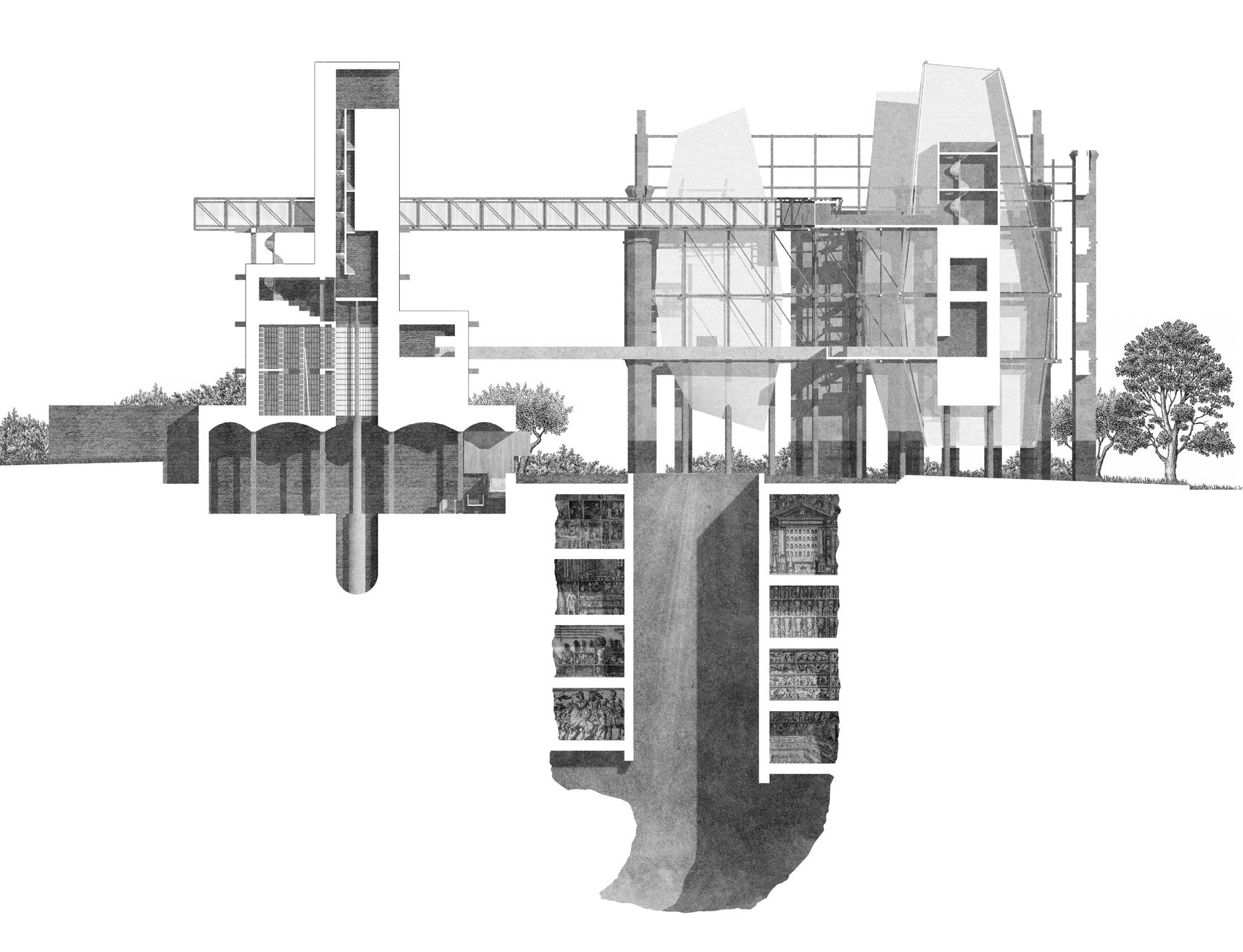

Art City hinges upon a simple question: how to build something in a public space without encroaching on its existing utility. The response is simple: to dig a hole and expand upward. The gallery has a permanent home on a slice of land to the south of the AGNSW, where the T4 train line to Bondi emerges from the side of a slope. This space is populated with a series of gallery towers that erupt from the plinth creating a microcosm of an urban environment. Circulation through the gallery becomes its own source of enthrallment, encouraging users to experience the gallery from different speeds and angles.

36

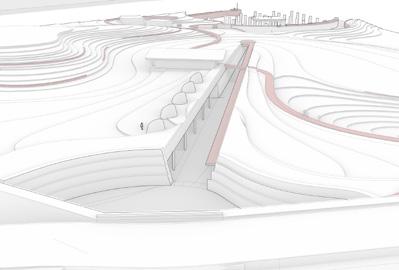

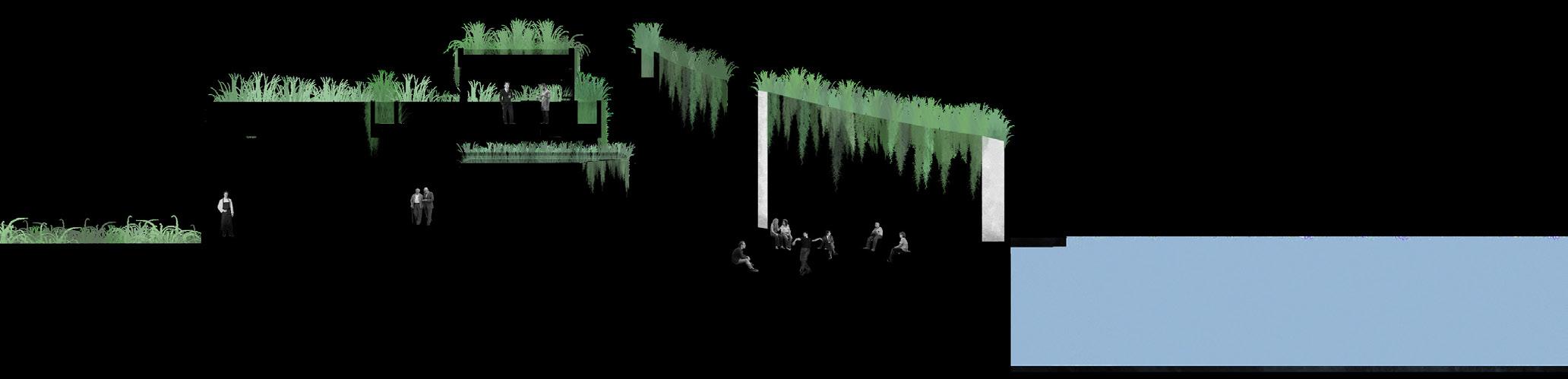

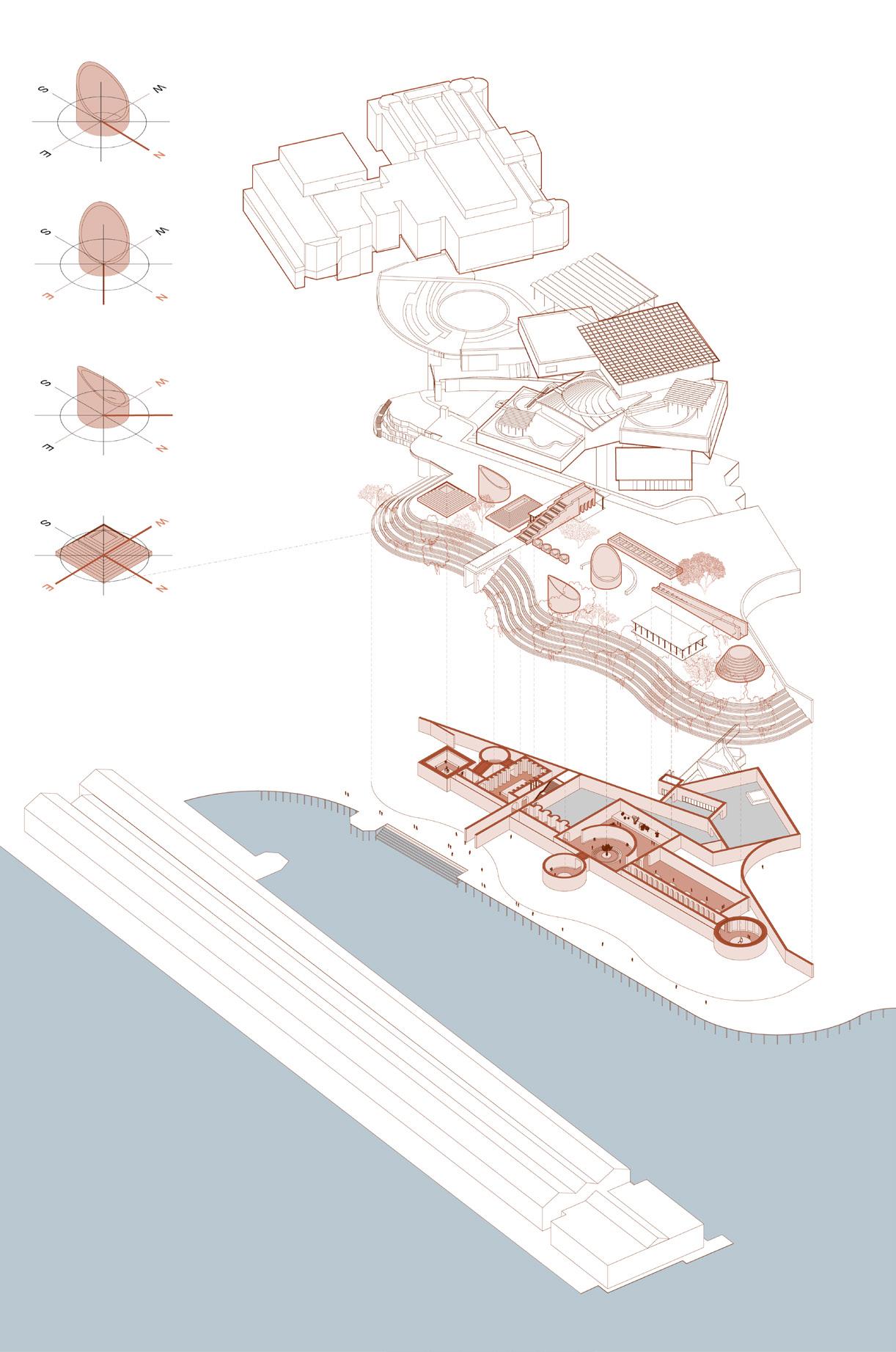

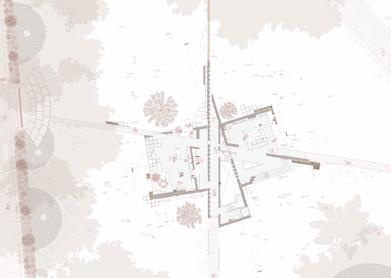

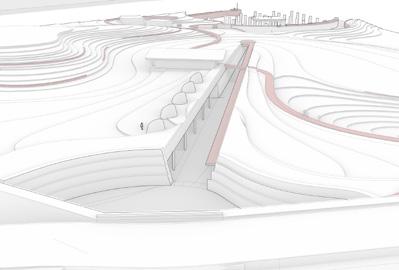

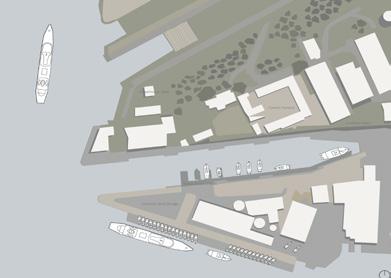

Within A New Landscape Matthew Fuller

The 2050 Expansion of the Art Gallery of NSW has been envisioned as a landscape extension, connecting the existing gallery and Sydney Modern project to the harbourside public domain. Within this new landscape is a meandering gallery beneath a newly created public park. Sculptural forms emerge to direct natural light into the gallery spaces below. These forms vary in orientation to capture dynamic lighting conditions across the year, creating different lighting atmospheres. Interstitial spaces of rest and reflection are located along the viewer’s journey. These spaces are open to the sky and contain seating and native planting to reflect upon art and light within a new landscape.

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

ART GALLERY OF NSW SYDNEY MODERN PROJECT

2050 PUBLIC PARK LAND

VARYING ORIENTATIONS OF SCULPTURAL LIGHT WELLS

2050 GALLERY EXTENSION

LOADING DOCK

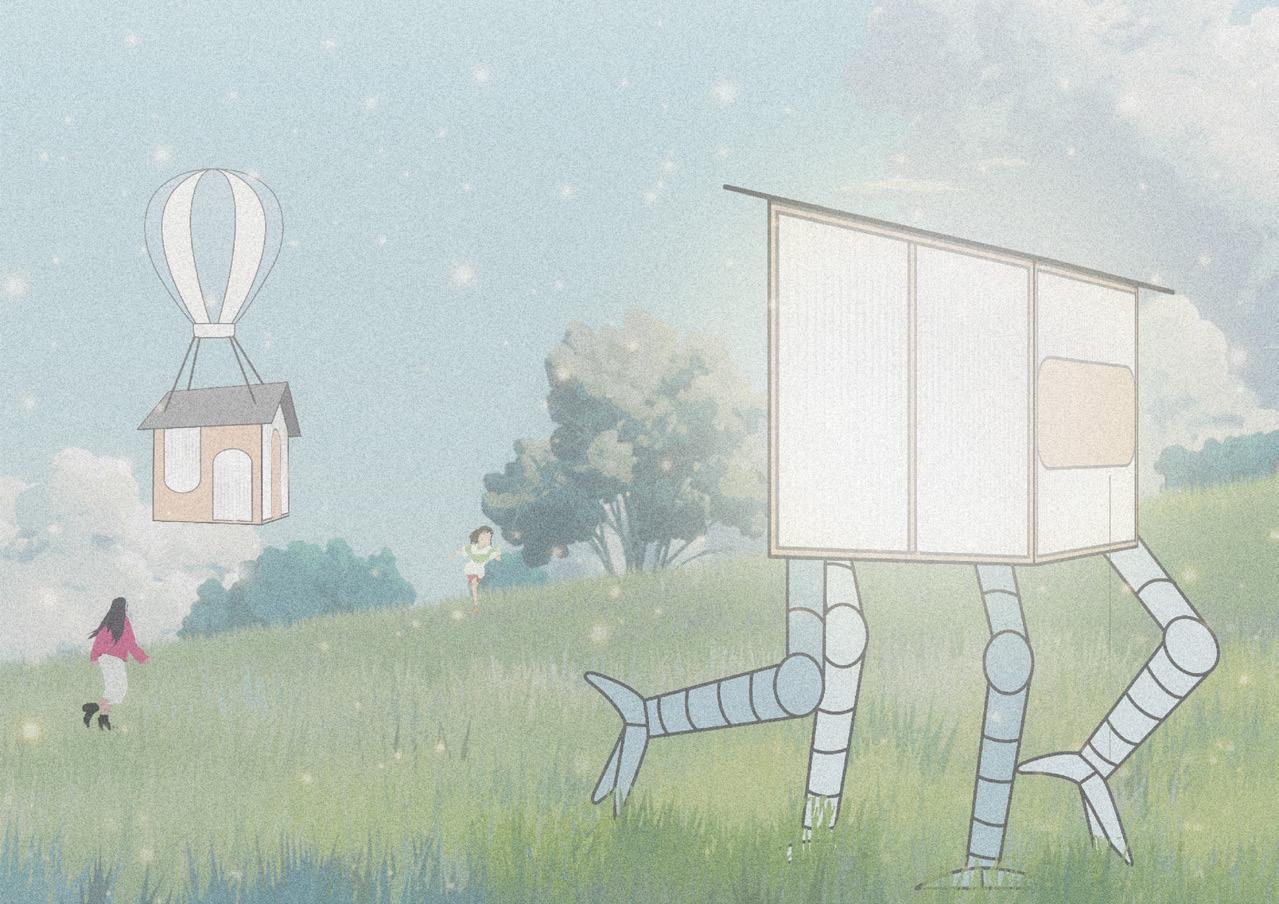

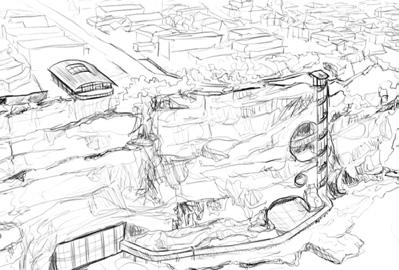

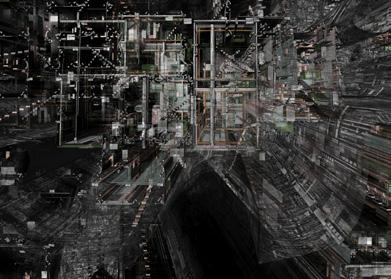

The Uncertainty of Program – Reacting to Displacement

Thesis Studio Sebastian Tsang

By living our daily lives and going about our day-to-day activities, we bounce between our familiar bubbles of space. It is evident that our changing spatial requirements only become more frequent with time. A row of sleepy shops can quickly become compartments of living when adopted by a few hundred residents. Even as children, we subconsciously claim and displace space with our sofa-cushion forts and assign invisible borders in playground corners, only to be dismantled after the games are over. In our global metropolises with skyward towers and sprawling construction, an involuntary and unstable motion of space pervades the senses. This spatial displacement extends to themes of urban sprawl, globalisation, migratory and nomadic movement, and the destruction of the natural environment. Do we need to resign to a conception of “lost” space? How are we to uncover these displaced spaces through the craft of architecture?

This studio explores multiple layers of spatial meaning and coding beyond that of a physical or superficial nature through investigative research and discursive exploration. Sites imbued with contested spatial dilemmas are targeted in the hope of unravelling a set of conditions eager for tectonic input. Students are encouraged to interject, expose, entangle, with one proposition: any preordained reckless program needs to be suspended, to avoid playing the hypocrite and succumbing to the forces that have caused displacement in the first place. As OMA put it elegantly for their proposal for Parc de la Villette – a project should emerge through “programmatic instability through architectural stability”.

Jun Win Choi, Total Alliance Health Partners International, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Andrew Fong, AJ+C Architects

Edward Li, Dreamscapes Architects

Alex Zeng, BVN Architecture

38

External contributors and critics:

Healing Hybrids

Stephanie Cheng, Jeffrey Liu

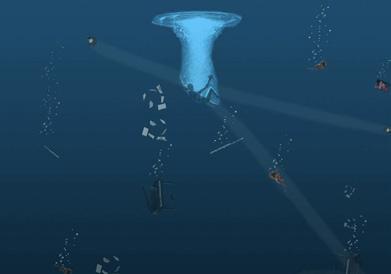

Healing Hybrids explores the process of loss in the physical and digital worlds. Situated in a future where the frequency of disaster events becomes more prevalent, the project serves to address the loss and devastation of individuals who are affected. With the predicted trend of increasing natural disasters; virtual catastrophes and multitudes of digital destruction will also become commonplace. We speculate on architecture’s role in facilitating the rehabilitation of loss in a hybrid, unconventional way. Healing Hybrids is posed as a polemical and satirical proposition to the current and future conditions of loss – to create a new and unexplored reality for rehabilitation spaces.

39 MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

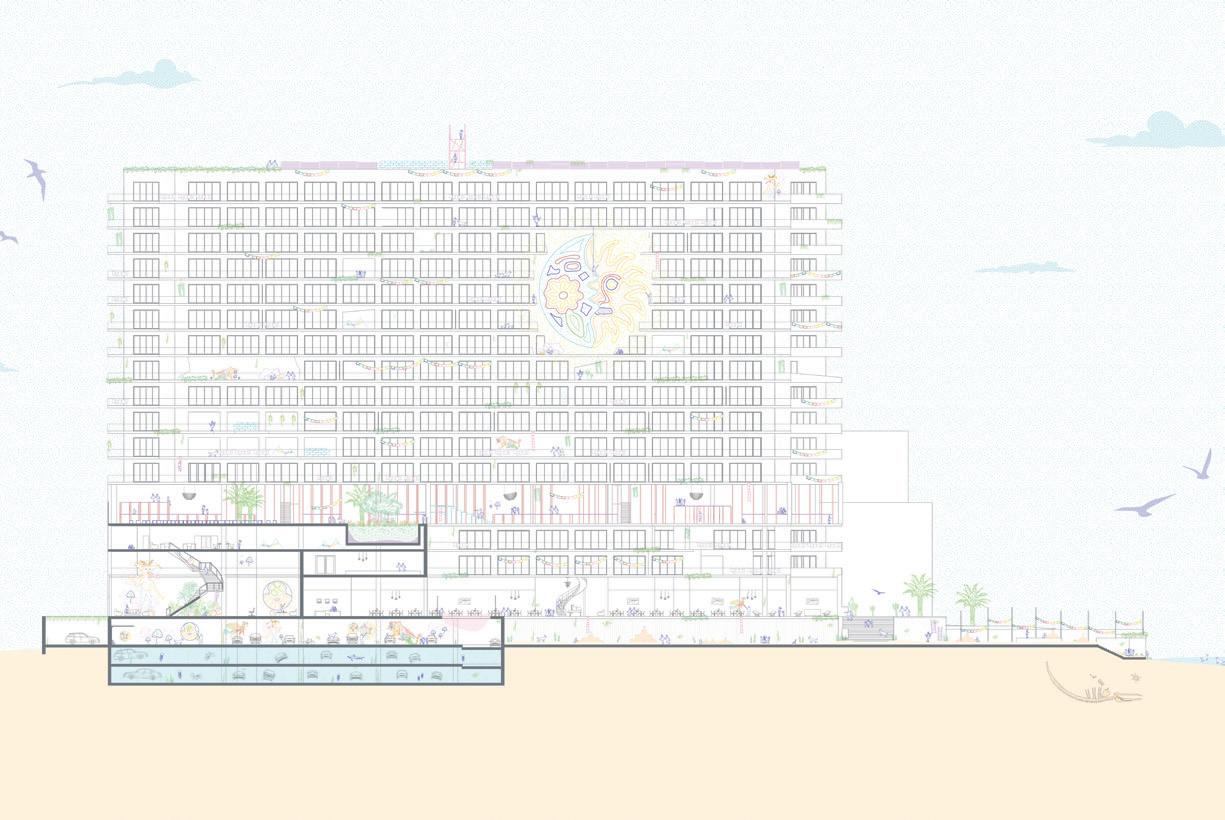

Playscape of the Forgotten Youth Annalise Blatchford

‘Junk playgrounds’ were first created on bombsites in the 1940s to promote creativity and autonomy through informal play. More contemporary versions in post-disaster zones have been used by children to re-enact traumatic climate events as a means of healing through play. Drawing on the pedagogy of these ‘junk playgrounds’, this project imagines how a hotel in Cancún, Mexico, could become a refuge for children in the year 2100 once rising sea levels have devastated the area. The playscape is a combination of degradation from severe weather events and playful interventions by the local children who have used play to reclaim the landscape as their own.

40

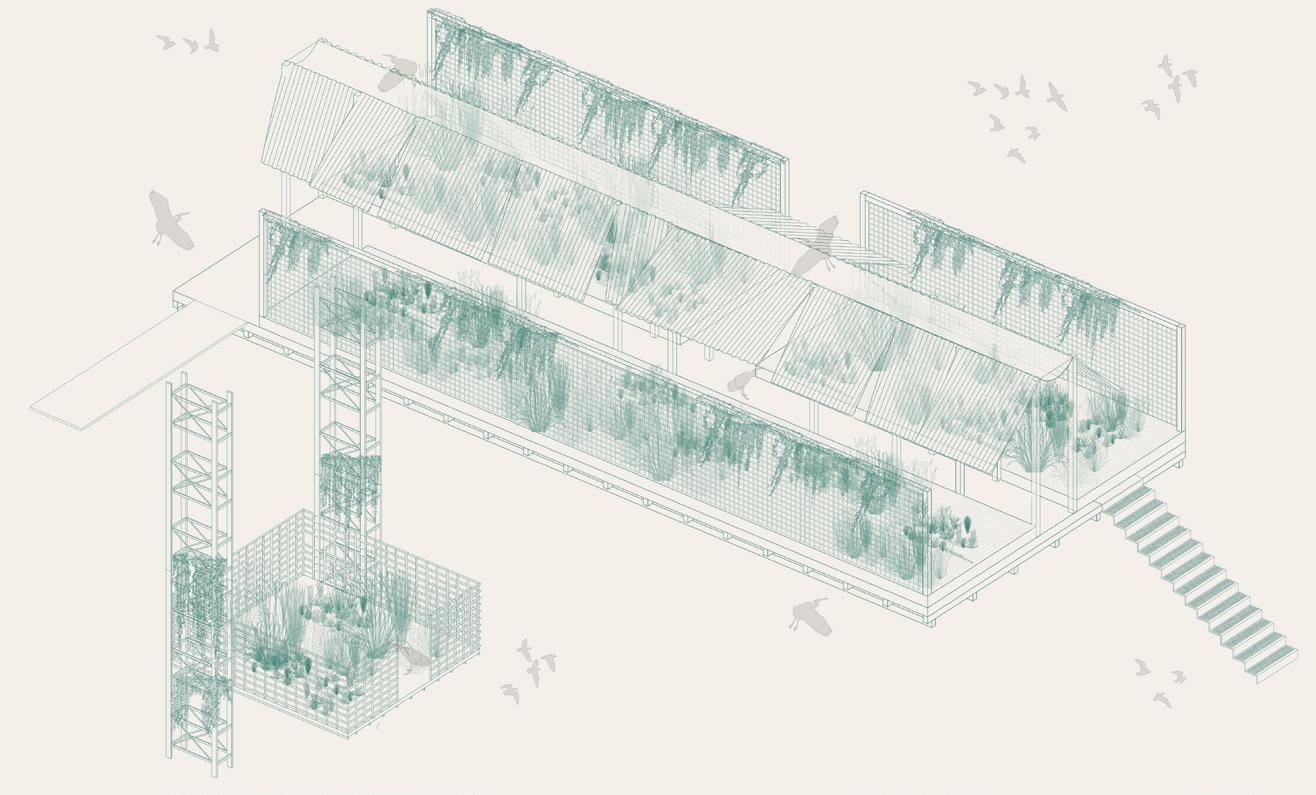

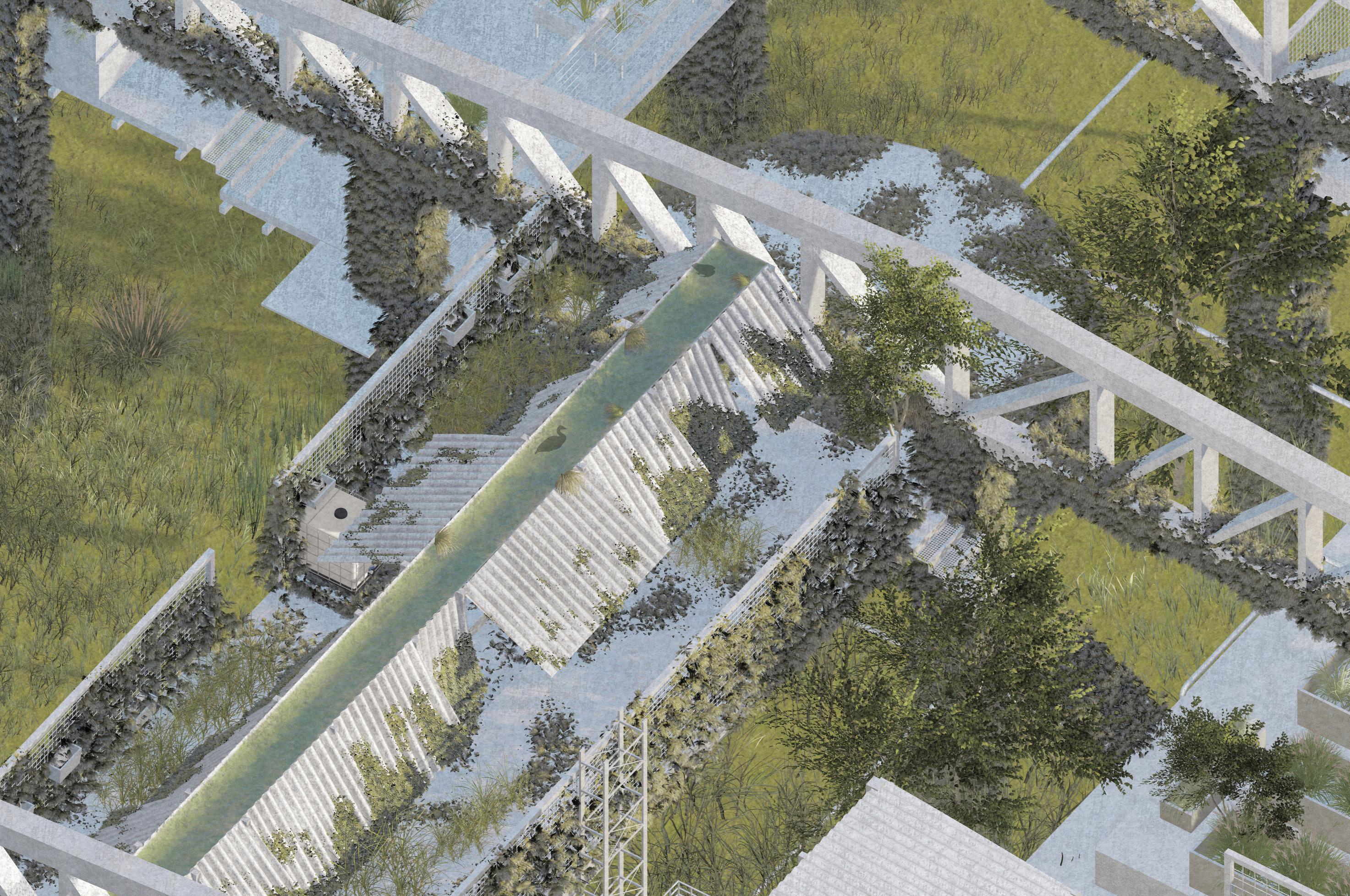

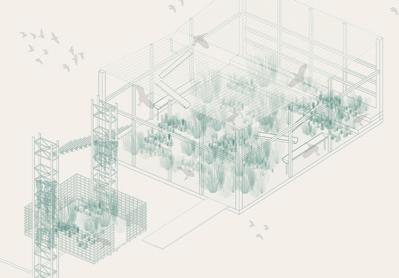

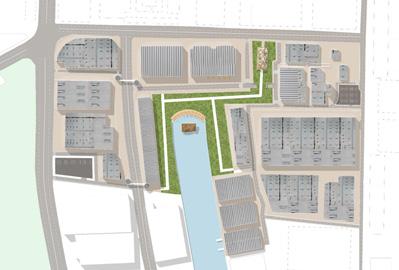

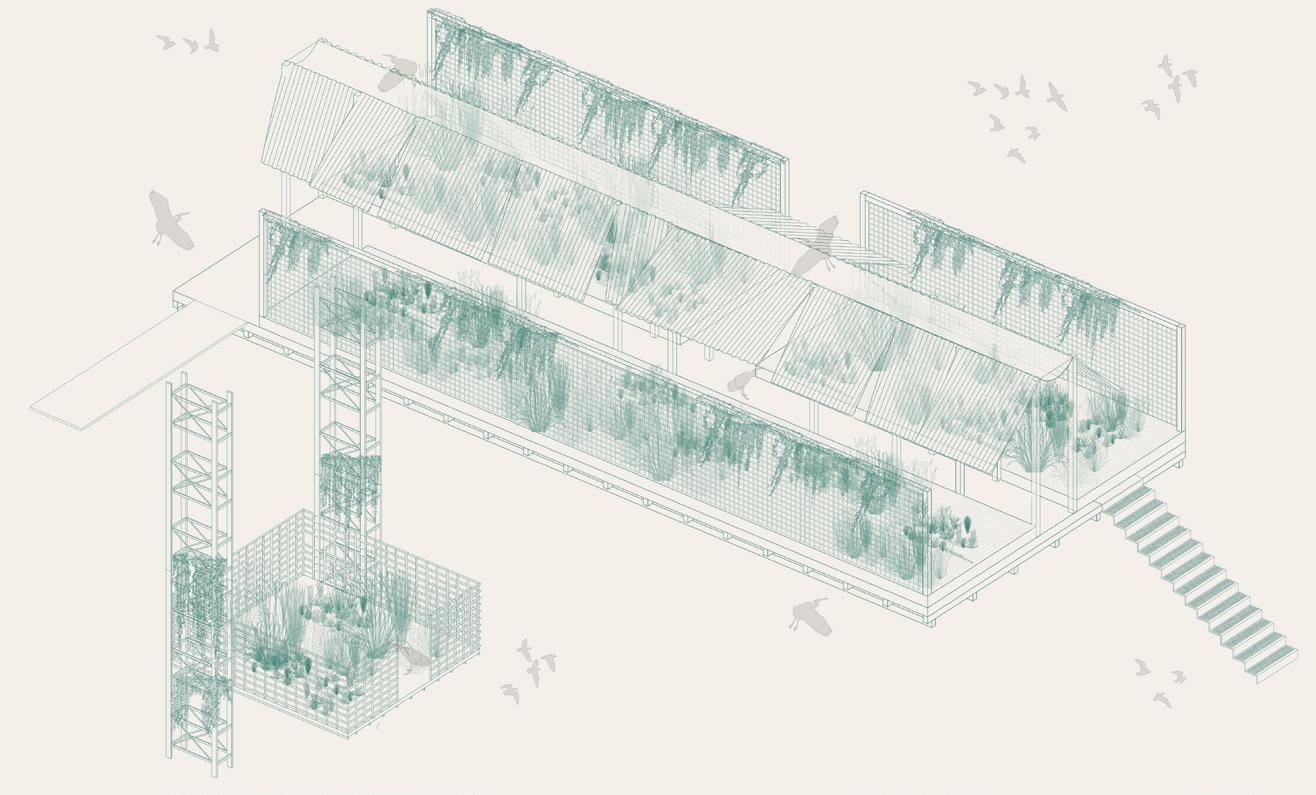

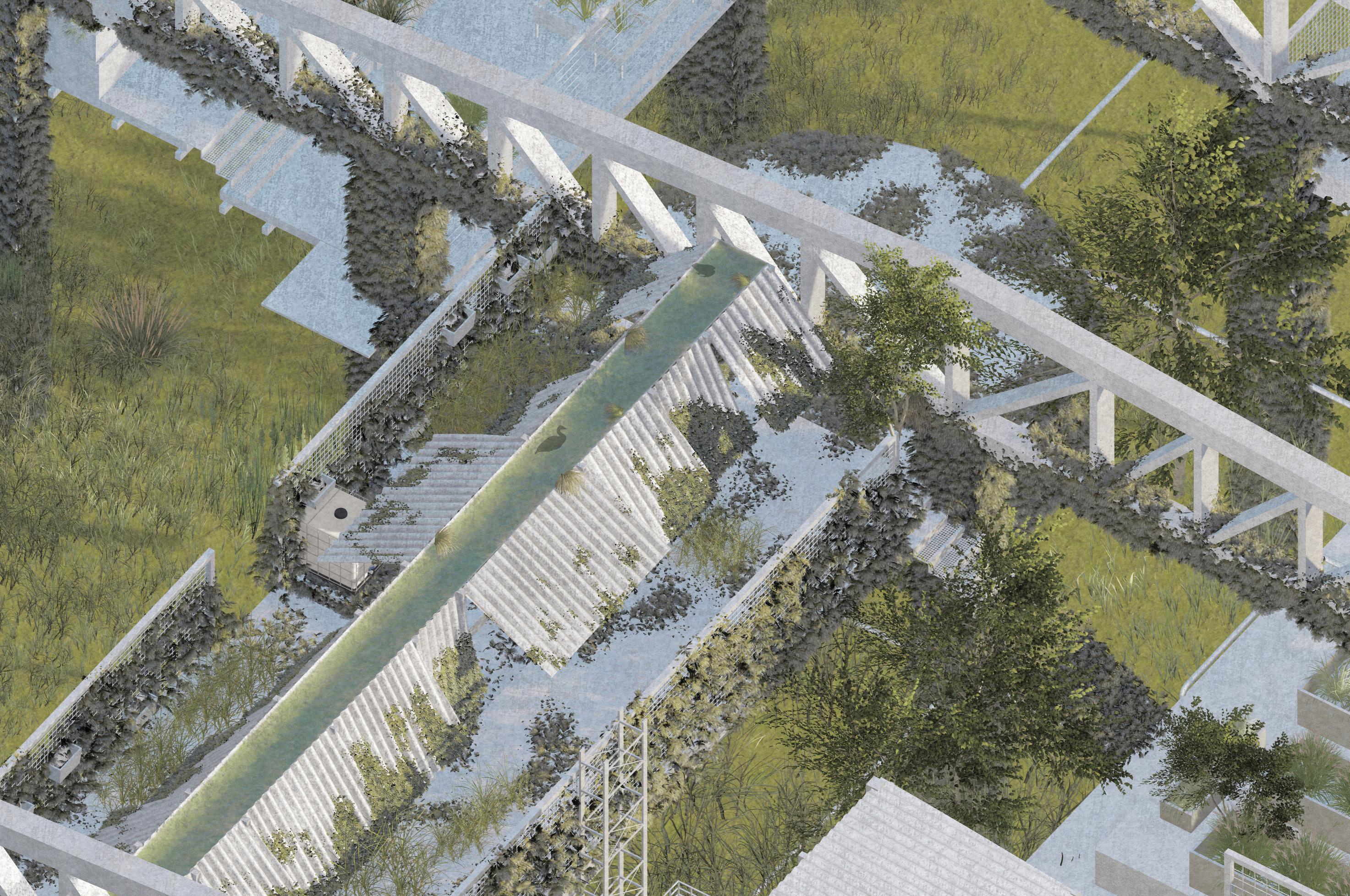

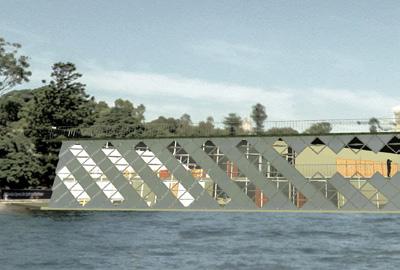

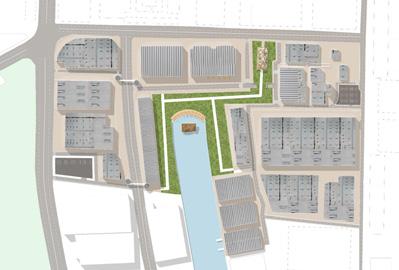

New Encounters: Architectural Ecologies in a Post-Industrial Landscape Ariane Easton, Felicia Perrino

Over the years of industrial occupation, the topology of Alexandra Canal in Sydney has been radically disturbed, displacing natural ecosystems in large quantities to facilitate urban development. Underused warehouses and a buffer of trees lining the rigidly shaped canal now define a highly modified shoreline hidden from public sight by these large structures and low lying position. This project acknowledges the culturally ingrained ideology of humans as separate from their natural environments and anticipates a future that repositions human occupation as a secondary priority to enable the regeneration of natural ecosystems.

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

Heterotopias of Connectedness: Gender, Sexuality and the Body

Duanfang

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, we have been living in an unprecedented unfolding of events. Alongside lockdowns, empty streets and daily reports of infection, statistics show an increase in loneliness and disconnection, with members of marginalised social groups being disproportionately impacted. There are calls for care beyond mere survival: care based on connectedness.

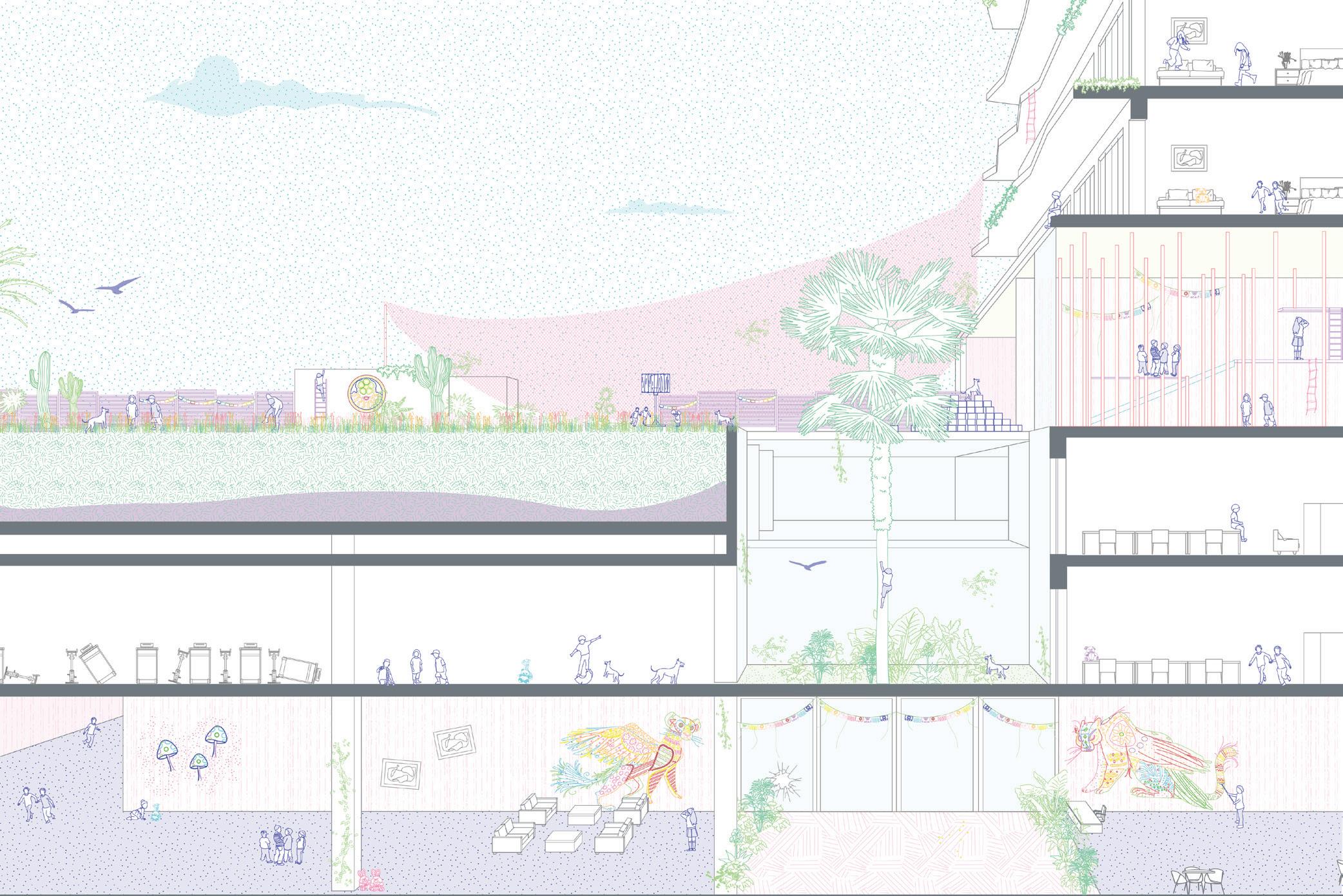

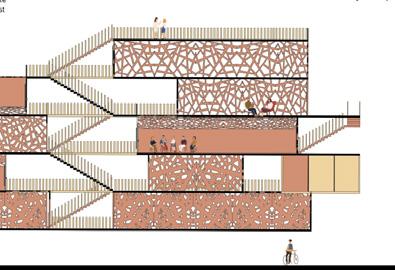

This studio explored the possibilities of developing architecture as critical infrastructure of radical connectedness by rethinking heterotopia. Heterotopia is conceptualised by French philosopher Michel Foucault in his essay “Of Other Spaces” to describe physical or discursive spaces where norms of behaviours and expectations are suspended, hence serving as a means of escape from power and repression. Unlike utopias, which are perfect but unattainable, heterotopias are places where things are different but real, places where the dominant rationalities of ordered society are subverted. In this studio, students create heterotopia(s) of connectedness, which allow marginalised bodies to exist free from fear and violence, to be accepted as equally viable bodies, and to flourish with mutual support and recognition.

Students design a City Centre for Gender and Sexuality to support women and the LGBTQIA+ (stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual) community through an alternative architectural approach to the renewal of the Goulburn Street parking station. They go beyond the conceptualisations of gender and sexuality as binary categories, to investigate the interaction between the body and space, and to explore the possibilities of making new places for empowerment based on contemporary debates around gender, sexuality, identity, subjectivity and the body.

42

External contributors and critics: Chungrong Hao Weijie Hu, USYD Vaughn Lane, Architect Vaughn Lane Yiwen Yuan, USYD

Thesis Studio

Lu

Soft Urban Connection: Soft Architecture in the Future City Jack Suen

This project explores the possibility of soft architecture to revolt attention to apply softness on the urban scale. Soft architecture is bio-informed design practice that requires the study of character of life, ecology, planetary systems, and nature. This project analyses the benefits and limitations of soft architecture on urban design and contributes to a larger-scale urban project that aims to enhance urban connectivity through a soft architecture system that creates soft connections through the built environment.

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

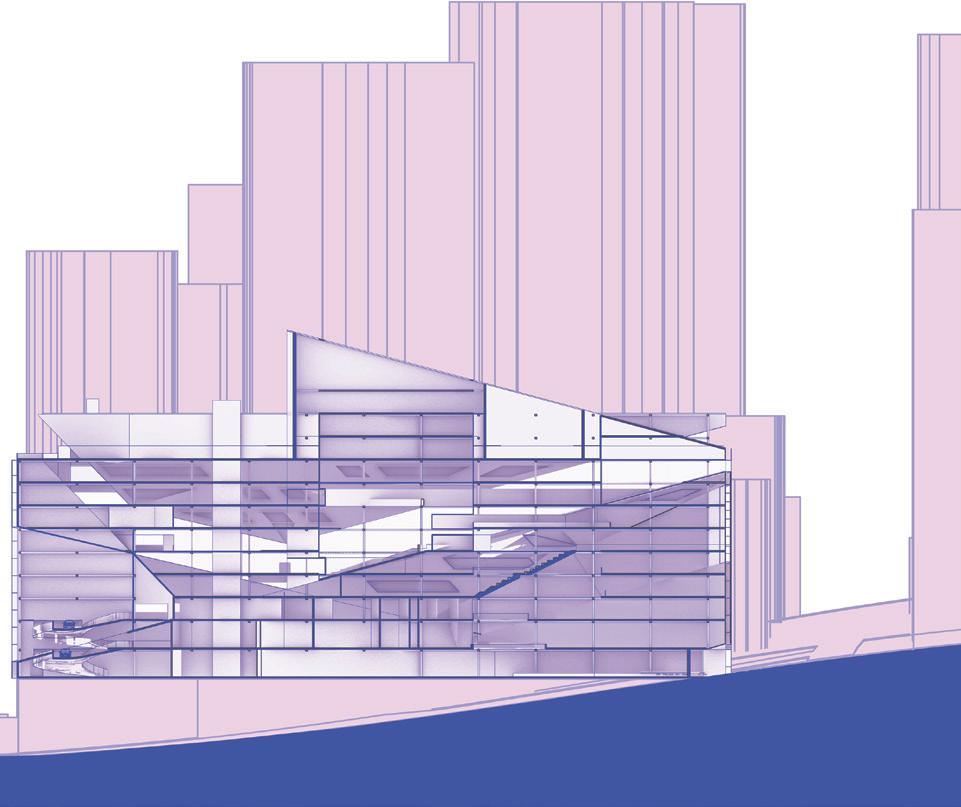

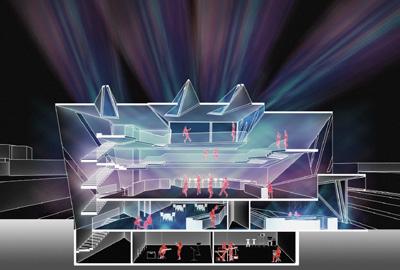

Transgender and Architecture: The Journey between Old and New Sherry Ruiyang Ni, Vincent Gengchen Yang

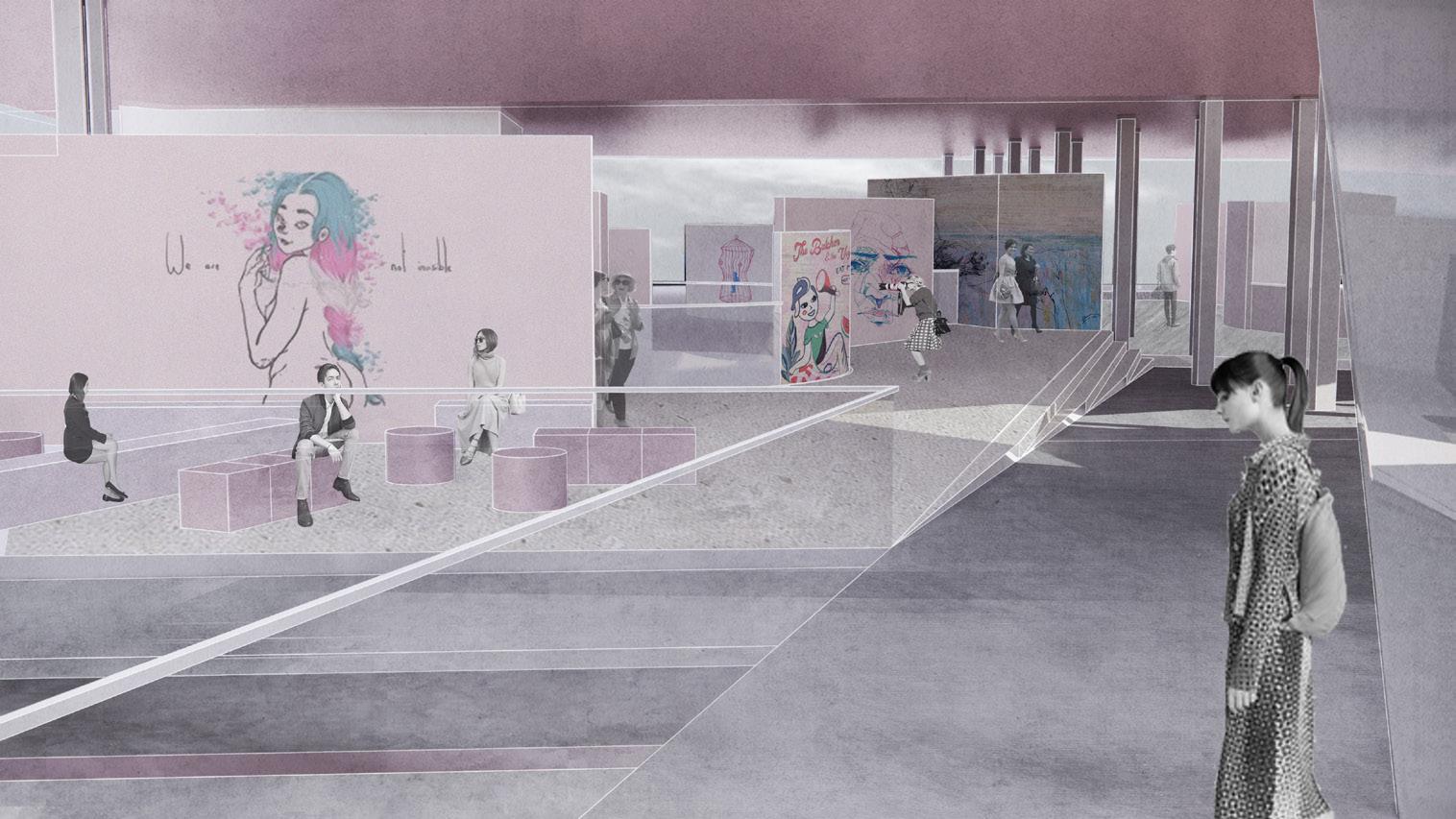

Identifying that art and performance are powerful tools to allow transgender communities to voice for themselves and improve their prescence in the city, the project will be a Transgender Cultural Centre. It aims to encourage communication and remove the misunderstandings between transgender people and the wider cis-gender communities. It emphasises multi-layered experiences and happenings between different groups of users, architecture and the surroundings.

44

Transgender & Architecture: The Journey between Old and New

Interior Moments --- Semi-Open Platform

Feminist Architecture: An Ideal Feminist Community for Working Parents Bingjie

Shi

Shi

This thesis focuses on the study of feminist approaches to architectural design. Since its inception in the 1970s, the concept of feminist architecture has been the subject of much debate and controversy. For example, what is the relationship between feminist architecture and feminist theory, and what kind of architecture can be called feminist architecture? Is there a unified standard and methodology, and is there a classic example to be followed and studied?

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

21

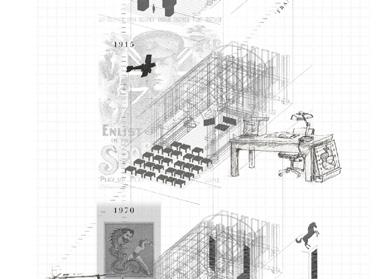

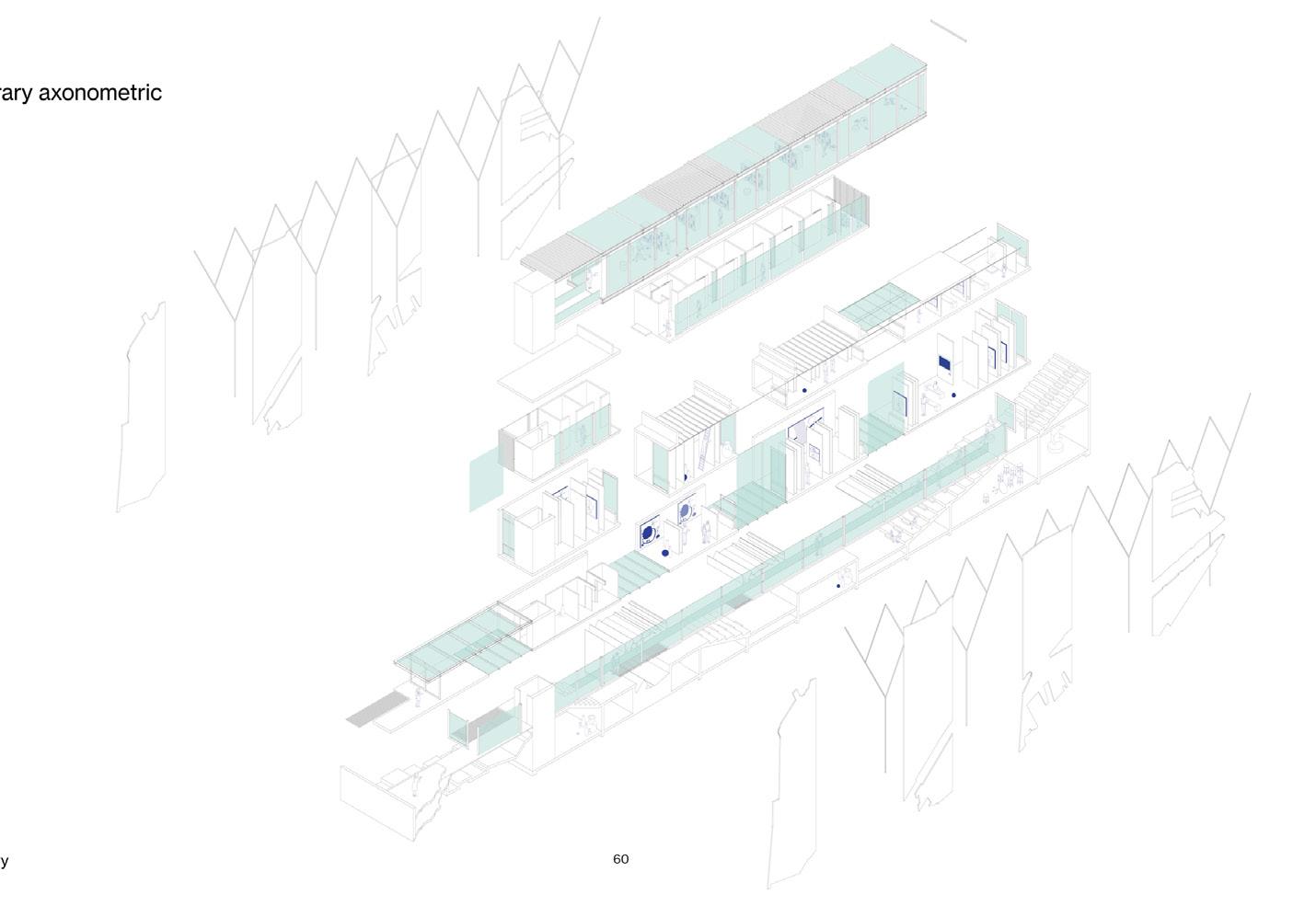

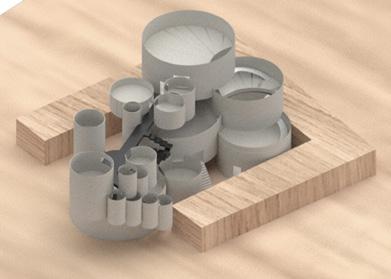

Future Archive

Thesis Studio Qianyi Lim

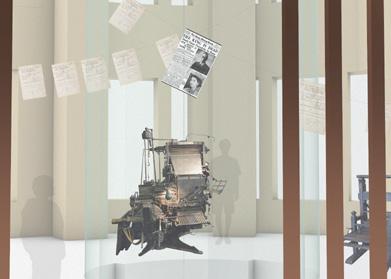

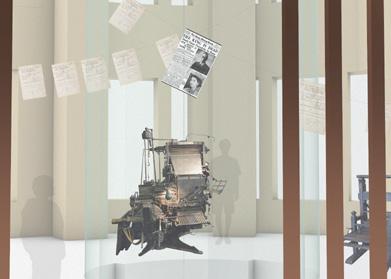

The Registrar General’s Building sits at the nexus of law, culture, commerce and recreation in Sydney’s northern CBD on Gadigal Land. A former physical archive of all post-colonial births, deaths, marriages and land ownership in the state, this early 20th century civic building – and its later modernist addition – now seeks new purpose within the city.

With the archive relocated, the building is now the temporary home for a mixing pot of arts and cultural organisations. Rebranded as RGB Creative, this incubator for creative collaborations hopes to seed new forms of cultural capital for the city, while a longer-term vision to revitalise it into a new ‘Museum of History’ is underway.

With this as a starting point, the studio asks what it means to archive cultures of the past and present, to challenge those of our future? What narratives, rituals and artefacts of today are memorialised for tomorrow? We will experiment and speculate in the adaptation, alteration, and addition of the existing architecture, to generate propositions that are inventive, critical and appropriate to their urban and social context.

External contributors and critics: Amelia Borg, Sibling Architecture Jack Gillbanks, PostAndrea Lam, Sibling Architecture Eva Lloyd, UNSW

Anthony Parsons, Anthony St John Parsons Architect Eleanor Peres, Sibling Architecture/Mone Studio Isabella Reynolds, Sibling Architecture Amy Seo, Second Edition Kien Situ, Art Gallery of NSW

46

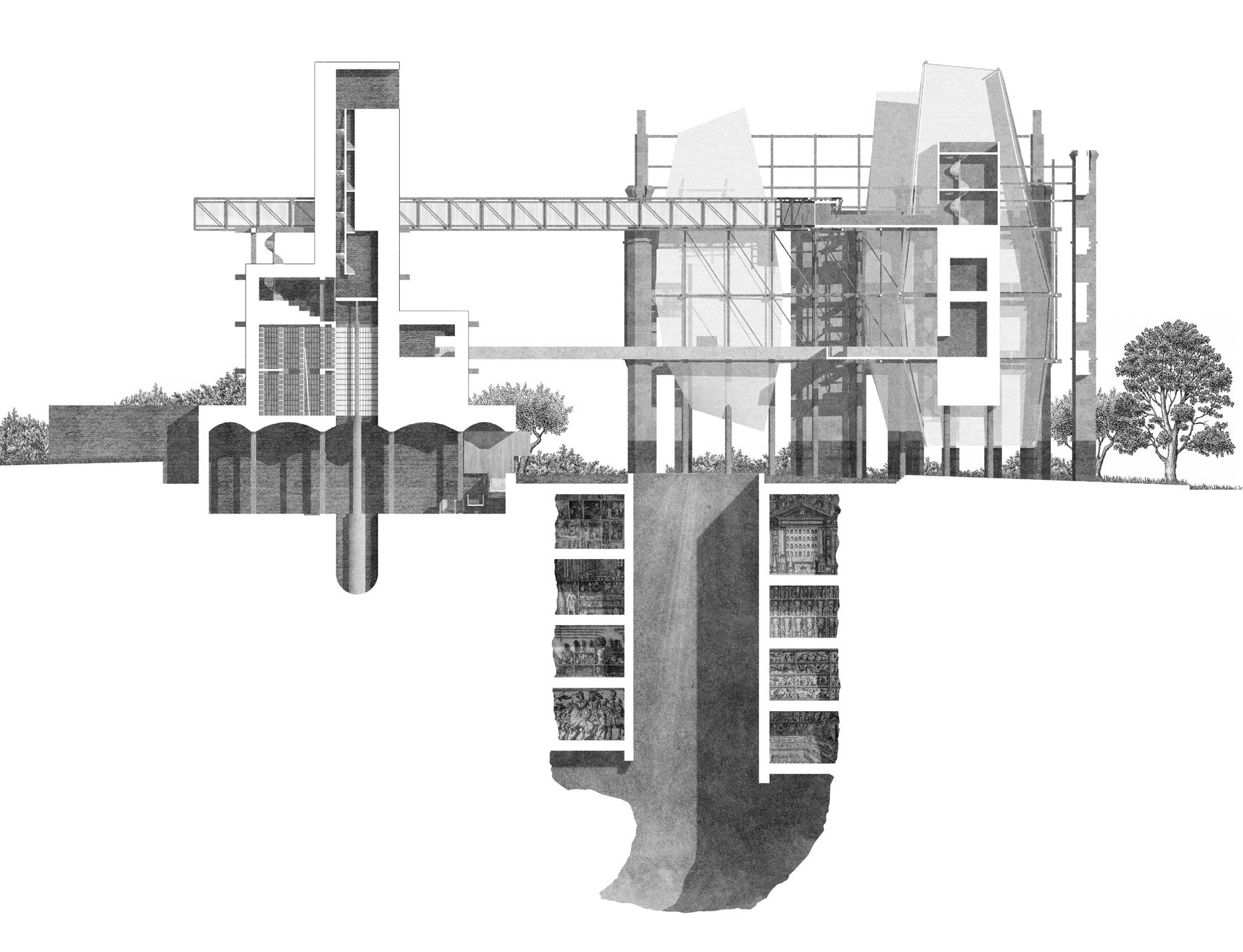

Allegory of the Museum of Fiction Kevin Hwang

The story begins with politicians and historians announcing a proposal to transform the Registrar General’s Building into Sydney’s most prominent museum of history. As a result, the various creative tenants who worked in the building became furious. The Creatives, frustrated with the obsession with history and museums as the absolute truth, demanded a new civic typology that challenges facts with fiction, absolute with imaginary, and tangible with intangible. The Creatives call it the Museum of Fiction

47 MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

Museum of Language

Justin Park

The paradigm of modern museums is such that it elucidates Guy Debord’s assertion that “the spectacle is the guardian of sleep”. The framing of artefacts as spectacles relegates spectators into a zone of passivity. It encourages artefacts to do our memory work, and we permit ourselves to forget our histories and past rituals. This proposal is a reaction against such phenomena, attempting to reverse the power of the spectacle and place it within the activity of the spectators. This ‘museum’ is a place for expressing and sharing language and engages users through sound. Through this active engagement, new memory and history can be overlaid, challenging permanence and championing the ephemeral.

48

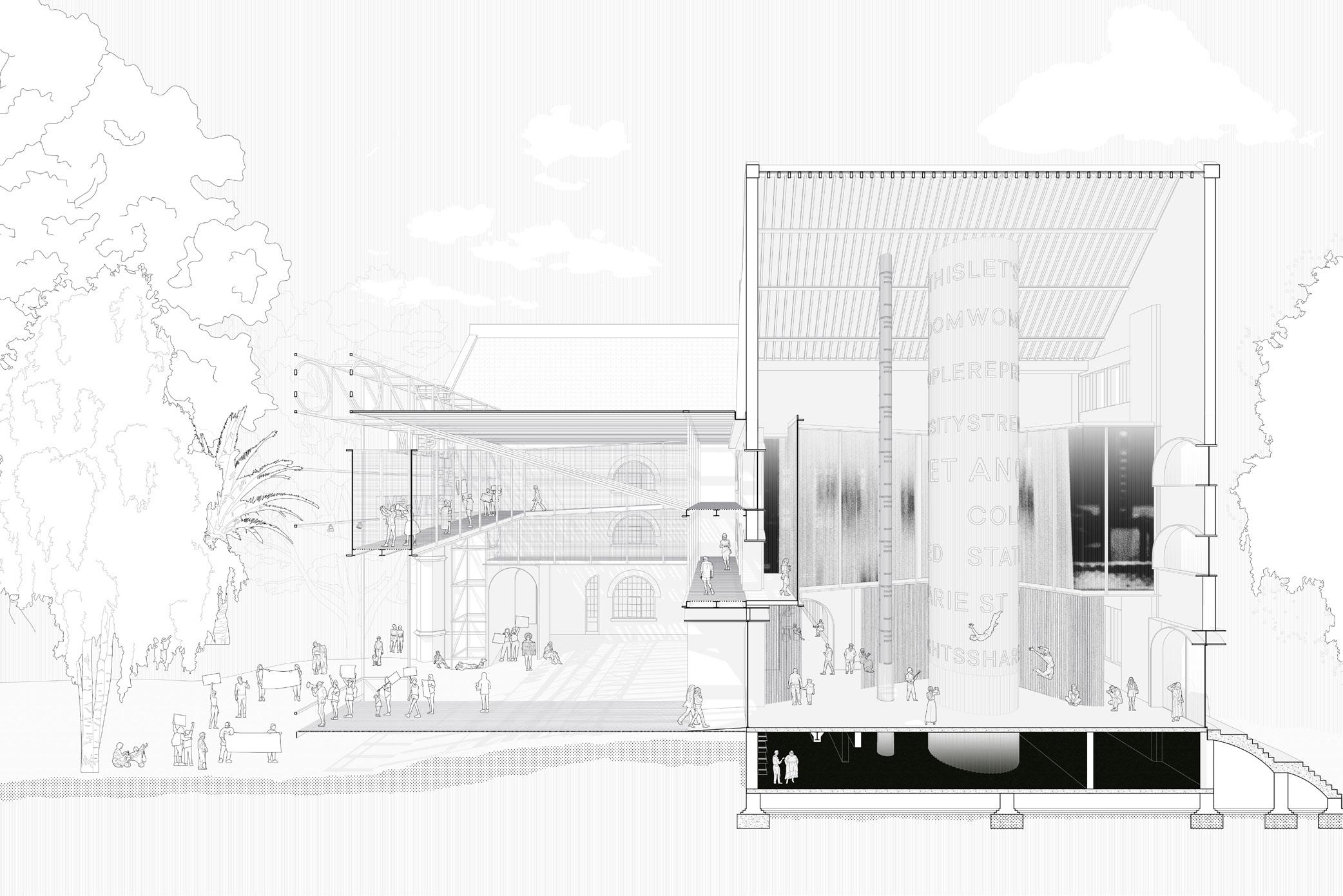

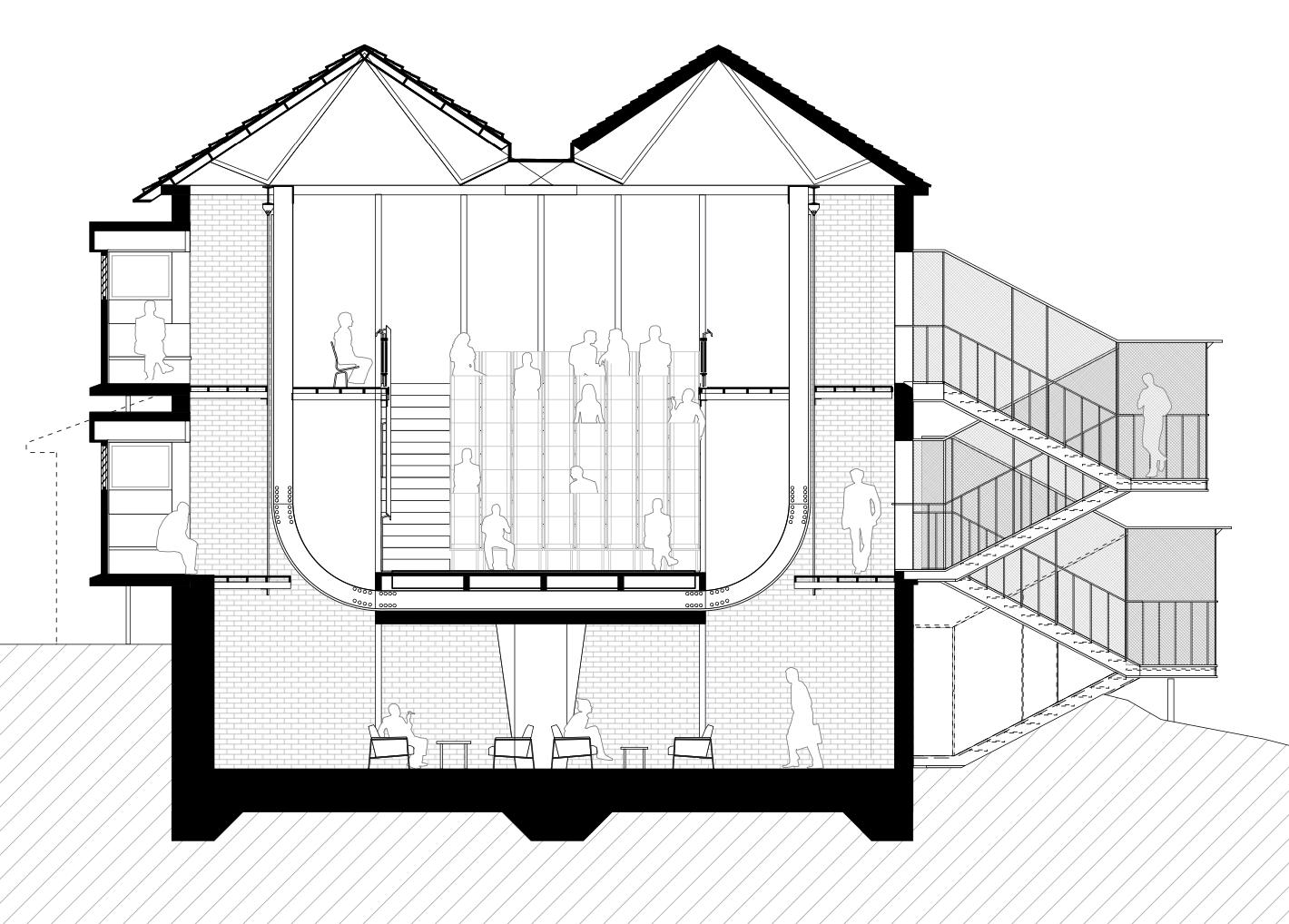

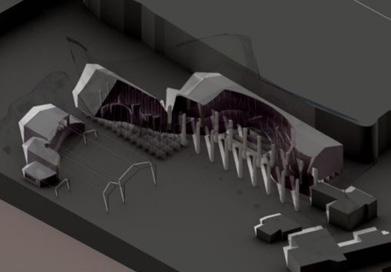

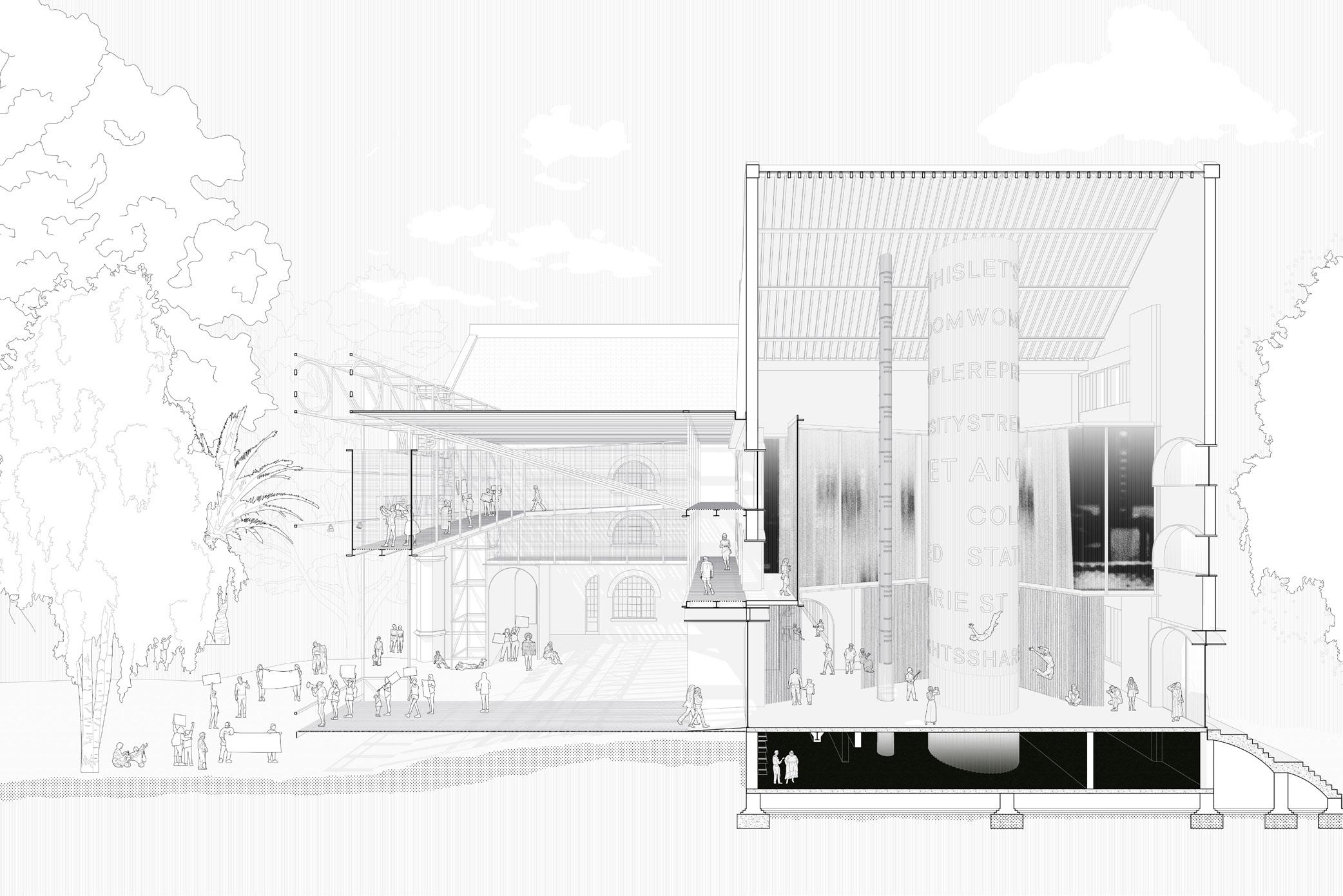

The Counter-Monument: A Museum of Activism Jade Grayson

The Registrar General’s Building is a former physical archive that sits at the junction of two significant sites of protest and activism, The Domain and Hyde Park. The project’s purpose was to connect the two sites, celebrate the history of activism in the area, and subvert the traditional archive to explore alternative, more active forms of remembrance. Conceptualised to align with the proposed plans for Queens Square, the Museum of Activism (MO–A) provides the infrastructure to support discussion, production, and performance. MO–A intends to function as a creation engine, providing a space that facilitates activism while preserving the artefacts and effects of activism.

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

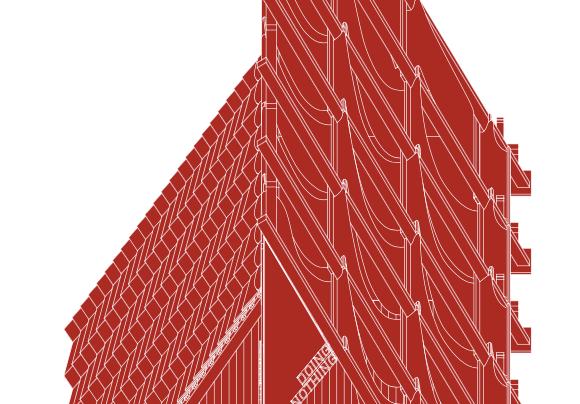

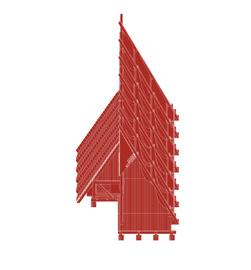

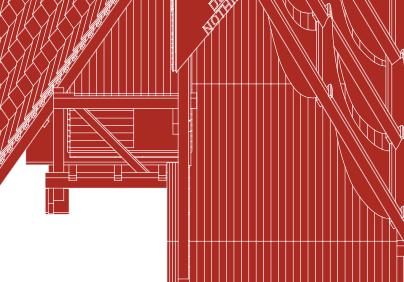

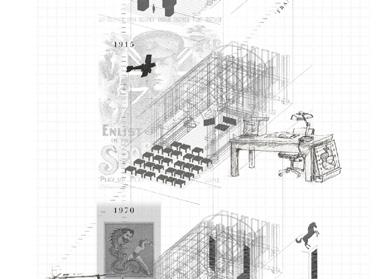

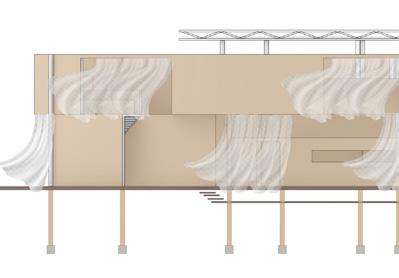

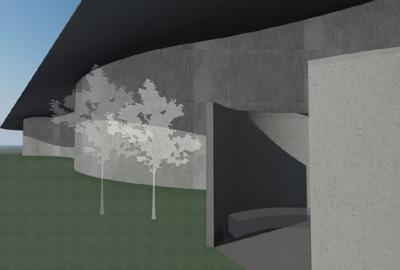

We Are Back: a Pavilion for Doing Nothing

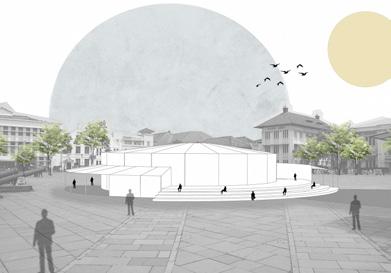

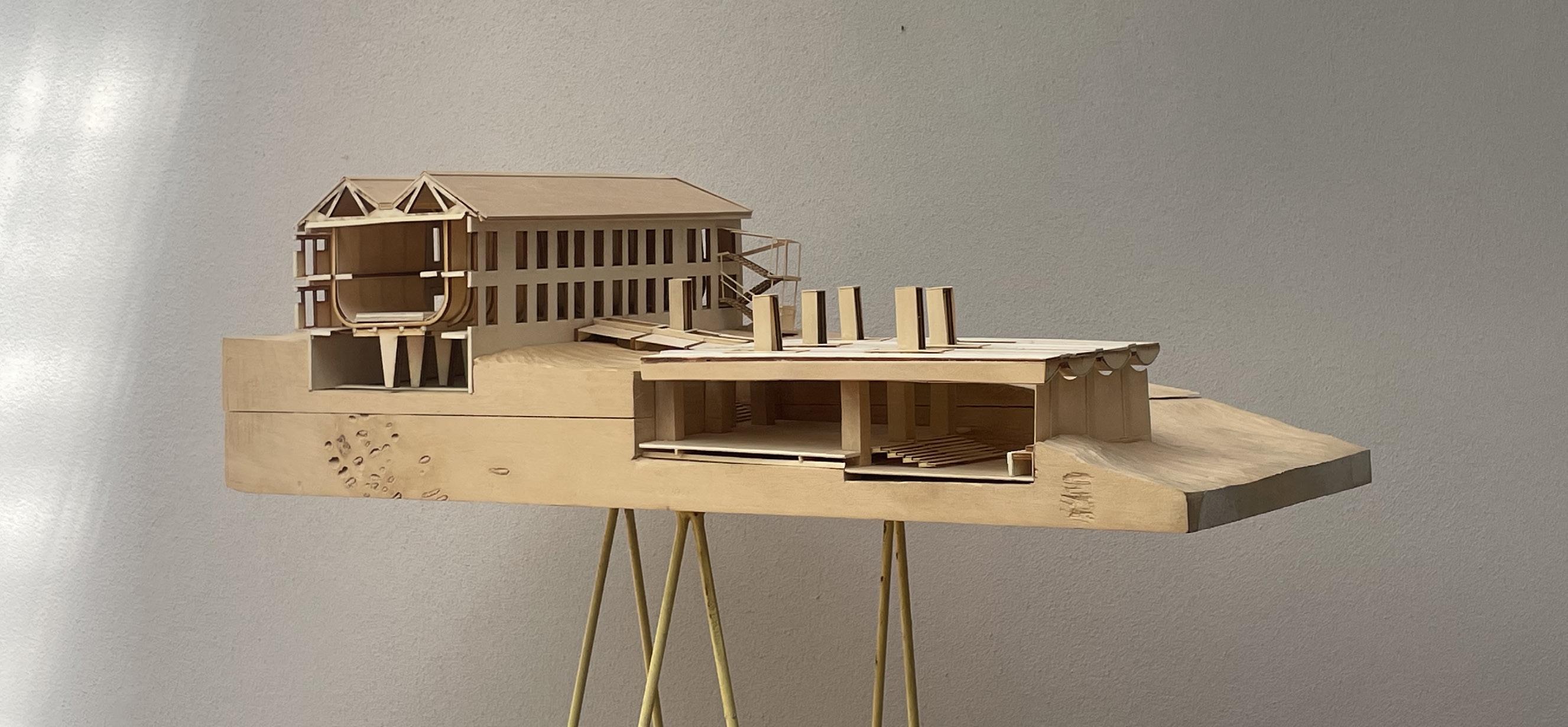

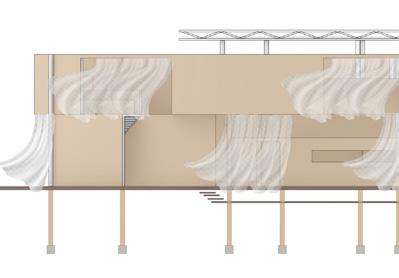

Thesis Studio Guillermo Fernández-Abascal

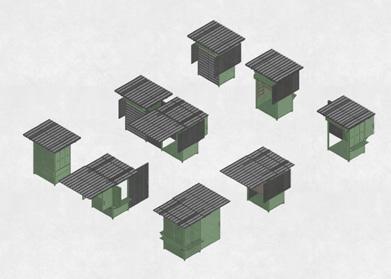

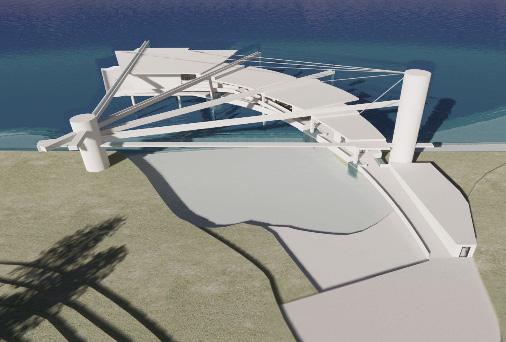

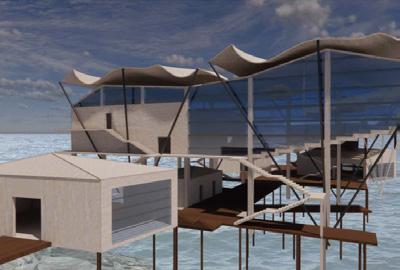

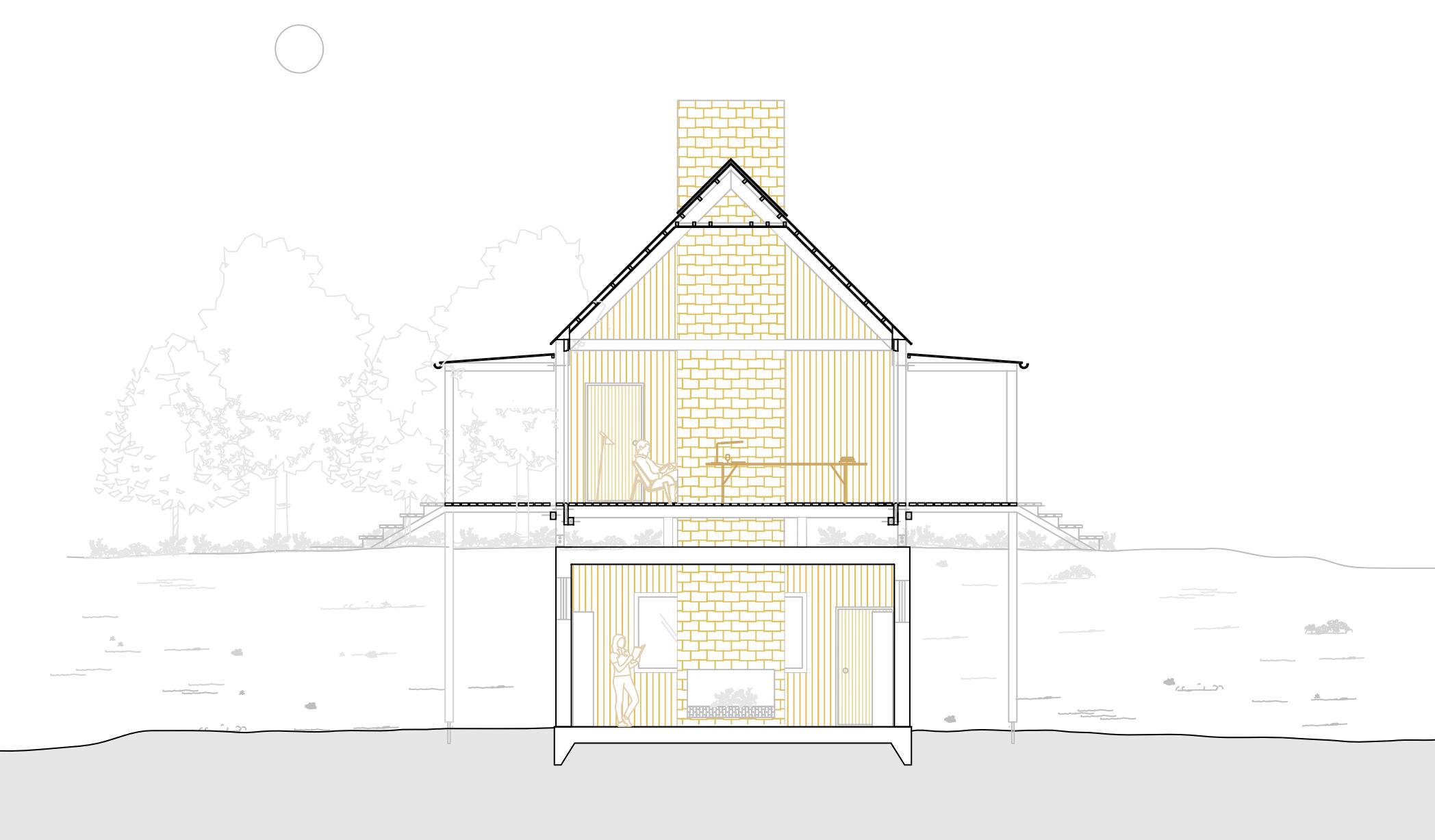

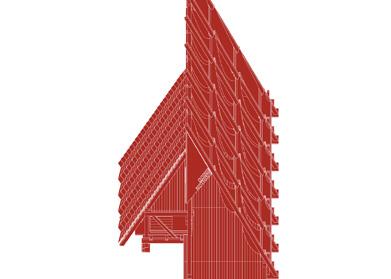

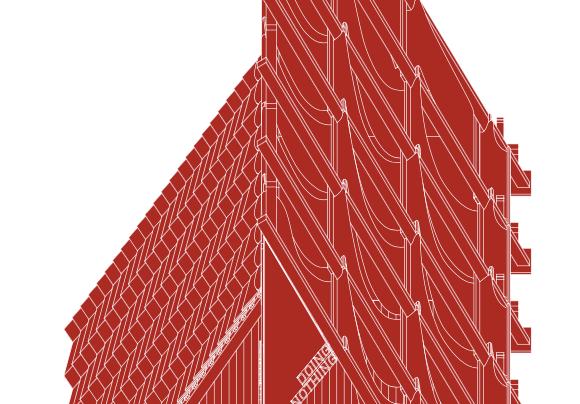

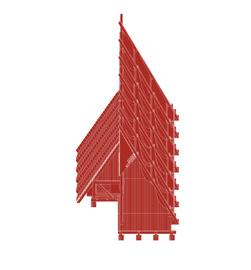

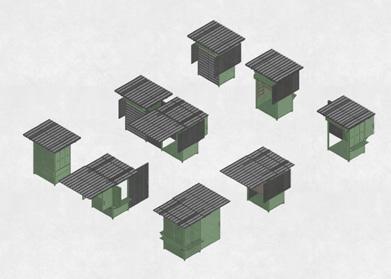

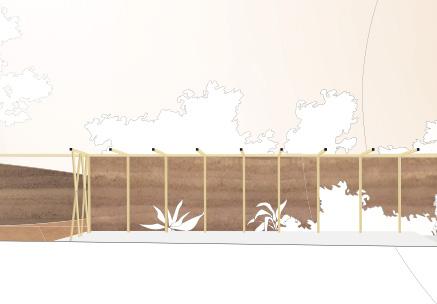

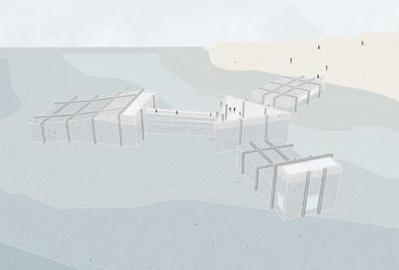

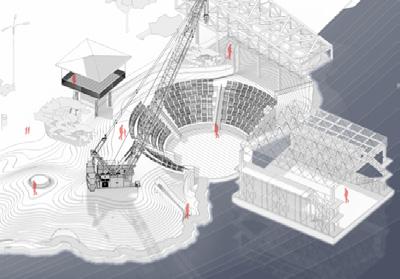

Well before the appearance of Covid-19, a process of global tiredness was already underway—we were undergoing social and political changes as profound as those that transpired in early modernity. Students, kids and the elderly, are the most vulnerable of all. Now, after three years of online education, the situation has been amplified. It is more than urgent to encourage students in the age of post-covid to build things together. In this thesis studio, zoom will be turned off, and students will be disconnected from the internet to instead use their bodies to design and build collectively. Students will explore the architectural potential of bricolage and re-use in a full scale (1:1) construction project designed and built by themselves. During the first weeks of the semester, we will design a pavilion. A clear set of constraints and an economy of means will influence the design process. Simple drawings, excel sheets and 1:1 mockups will be the documents required to conceive this construction. For the following weeks, altogether will build the big artefact. The semester will finish with a one-week series of events to celebrate the final construction and its eventual scenographic disassembly.

Note: Arguably, the most interesting pedagogical experiment at USYD was the legendary Autonomous House. 50 years later, in an analogous political and climatic crisis, it may be the time to build together again.

Sponsors:

Hyne Timber

Natural Brick Company

Bruynzeel

Marmonyx Stone

Cantilever Engineering

External contributors and critics:

Eduardo De Oliveira Barata, USYD

Charles Curtin, Mac & Cheese

Shahar Cohen, Second Edition

Troy Donovan, Prism Facades

Urtzi Grau, UTS/Fake Industries

Eleanor Peres, Sibling Architecture/Mone Studio

Juan Pablo Pinto, Cave Urban

Daniel Ryan, USYD

Amy Seo, Second Edition

Janelle Woo, UTS/WSU

With thanks to all the people that have made this project possible.

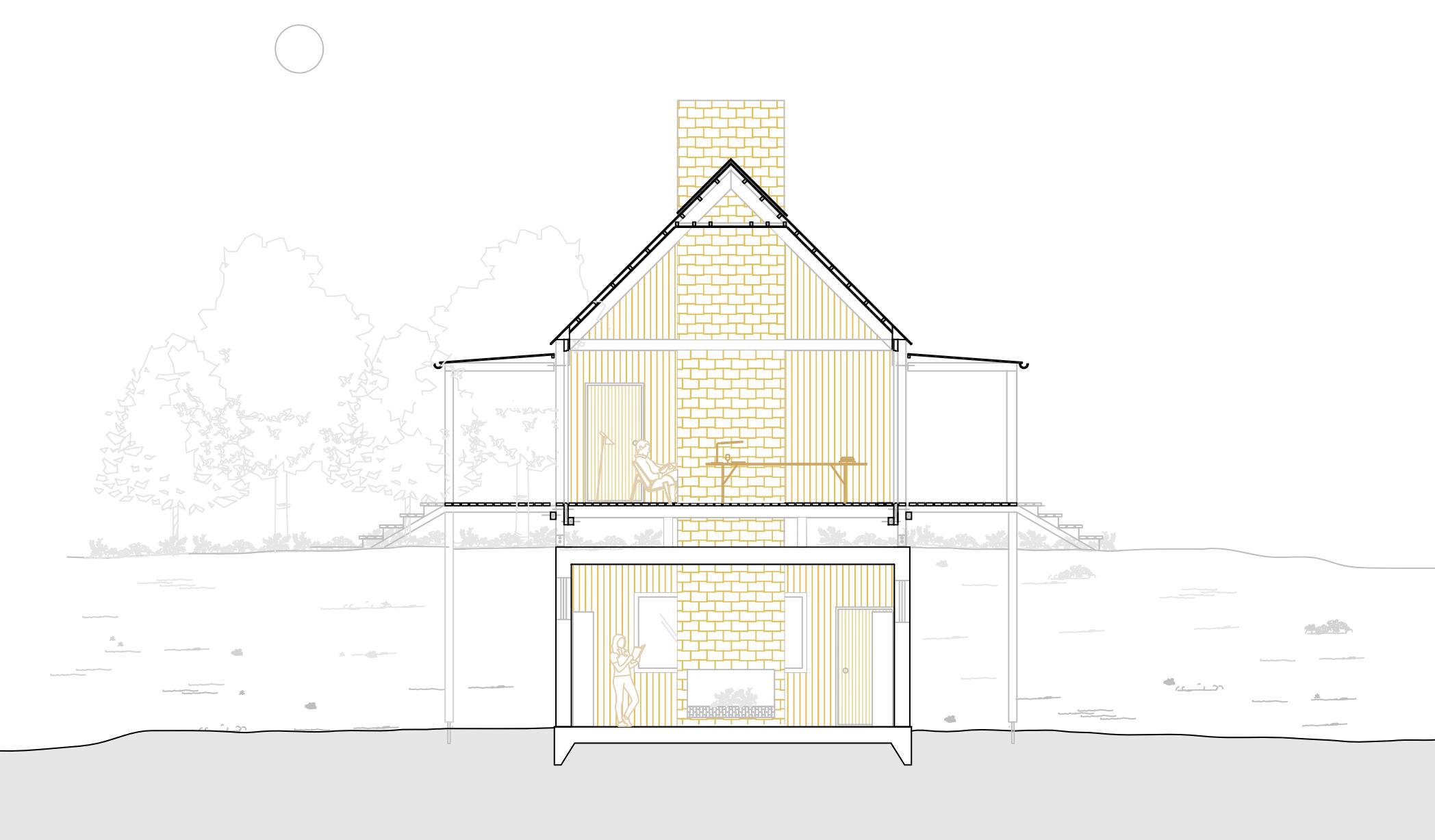

50

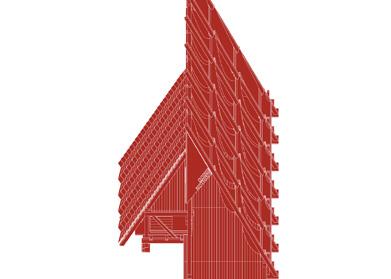

PAVILION

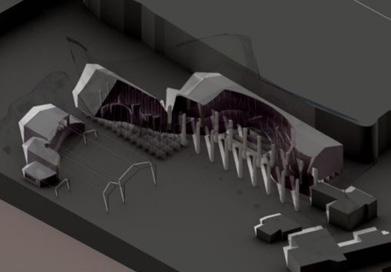

A Pavilion for Doing Nothing

Ryan Cai, Alvis Chan, Elsie Chan, Howen Chang, Wenjing Hu, Kexin Lian, Amy Lieu, Tim Milross, Parantap Patel, Abhishek Rupapara, Magnolia Sawiti Unsur, Xiaoying Tang, Mustafa Vahanvaty, Deborah Wabasa, Dawei Wang, Sam Wong, and Ryan Xie.

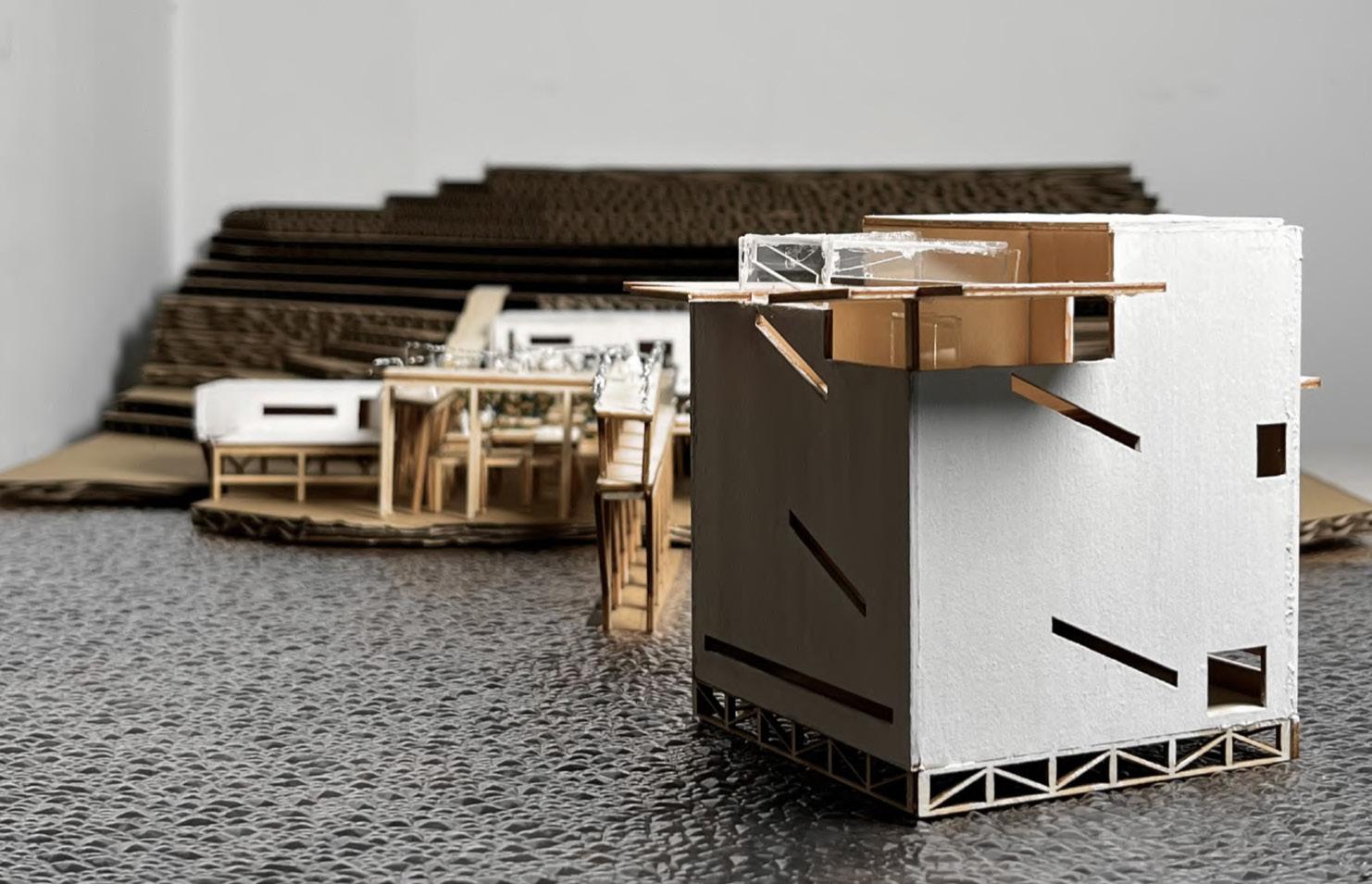

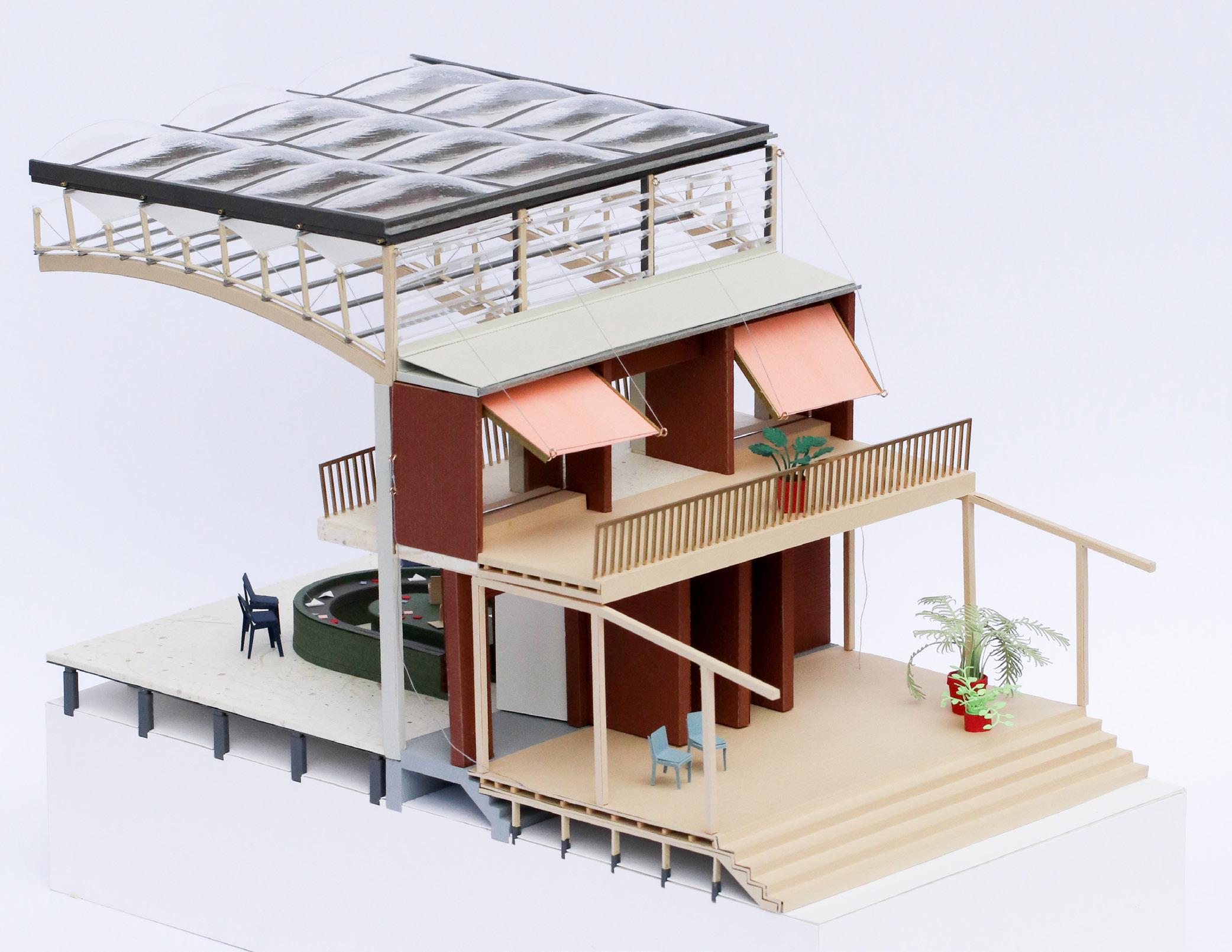

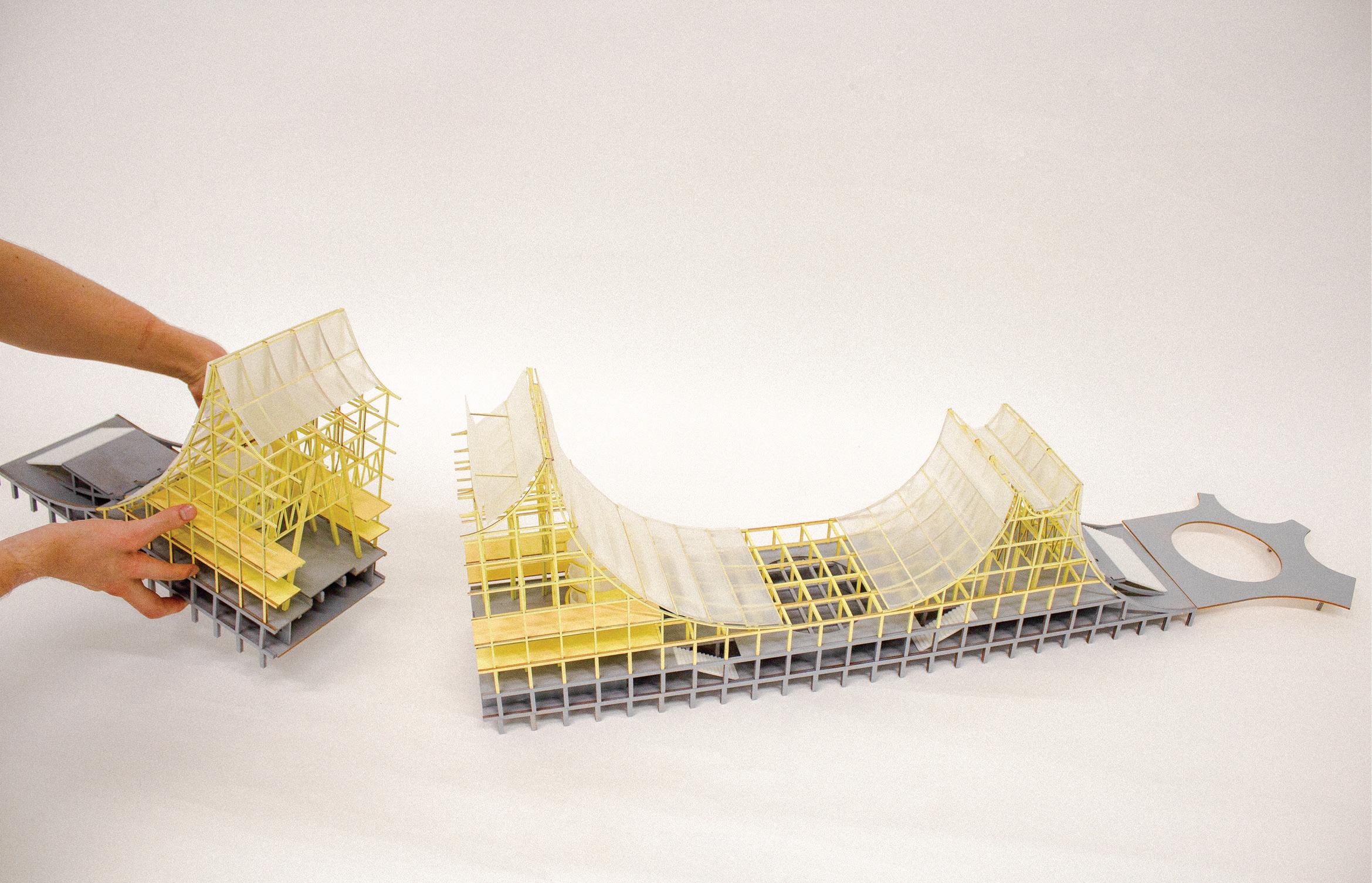

A Pavilion for Doing Nothing is an architectural installation at the Atrium of the Wilkinson Building. The fragment of the pavilion was set up as a 1:1 model to discuss the structure and its larger ambitions. We, now, all know that Doing Nothing is hard work.

51 MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

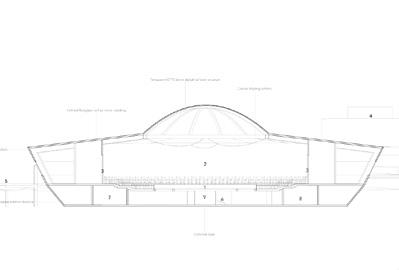

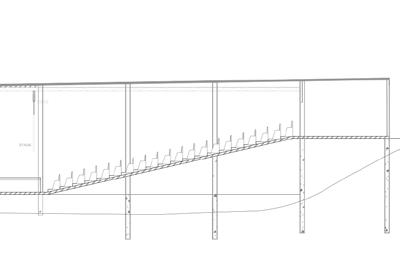

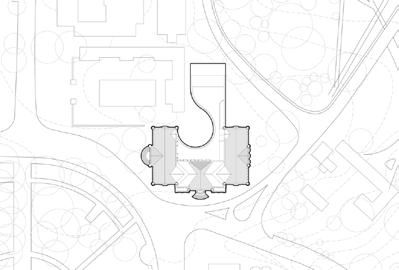

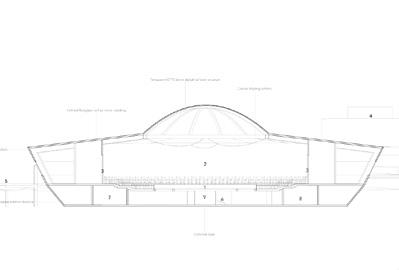

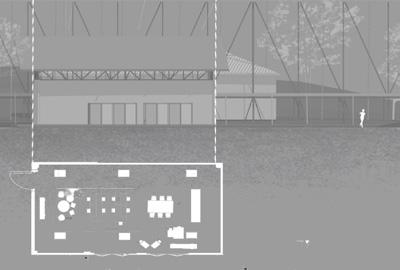

Pavilion Plan 1:50 3

Together, we performed numerous tasks including the deconstruction of a building, the construction of some mockups and fragments, and we will finish by disassembling them collectively. We visited factories, yards and buildings. We learned about timber construction, fabric and recycled concrete panels. We discussed the potential of temporary buildings, the lack of circularity within the industry, the reality of supply chains and the actual economy, and how Australian craftsmanship is a delusion. We read some texts, did some drawings and a bunch of risk assessments, but we mainly built together. We tested our collaboration, sometimes complicated, first hand. We would like to finish by speculating on the possibility of practising like this in Australia today.

Checked by: GFA Date: 05/10/2022 Revision: D MARC60 0 0_Group B WE ARE BACK: A Pavilion for Doing Nothing by: AL

It seems clear to us that we all love the painful act of construction equally. A failed, yet hopefully enriching pedagogical experiment, we tested how to build a relatively big minor architecture with enthusiastic but unskilled labourers in a University context.

52

53 MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE 11

Architecture, Aesthetics and Ideology

Thesis Studio

Felix McNamara

Aesthetics are rarely explicit or central themes in architectural studios. The aim here is to use aesthetics as a field for critical and experimental architectural play, creating a bridge with broader discourses on culture, politics and ideology.

Students develop architectural projects in response to specific aesthetic concepts or categories, such as: Kitsch, Cute, Quaint, Interesting, Zany, Cool, Normal, Boring, Gimmick, Ascetic, Liminal, Lazy, Uncanny/Unheimlich, Disgusting/Grotesque, Ugly, Picturesque, Artificial, Surveillant, Hyperreal, Virtual, Grunge, Vaporwave, Punk, etc (Ad infinitum)......

Students use their design project to dissect and deconstruct their chosen aesthetic category. Someone working with the category of ‘the cute’ for instance might respond to Sianne Ngai’s analysis of cuteness as an aesthetic of contemporary consumer culture which invokes both love and care but also potentially violence and abuse - in this sense, the seemingly mundane topic of cuteness reveals questions of gender, class and economics among others. Someone exploring the aesthetic category of ‘Corporate Punk’ might question how the architecture of Bjarke Ingels or Patrick Schumacher resonates with the political aesthetic of someone like Boris Johnson, which would simultaneously consider how onceradical aesthetic terms can be quite easily commercialised.

External contributors and critics:

Chris L Smith, USYD

Hannes Frykholm, USYD

Shervin Jervani, USYD

Maren Koehler, USYD

Janelle Woo, UTS/WSU/Paradise Journal

Jessica Spresser, SPRESSER

Jack Gillbanks, Building Research Workshop

Peter Besley, Peter Besley Studio

Anna Tonkin, Art Gallery of NSW/Post-

54

Mess Sarah Vy Anstee

Mess is an inarguable product of occupied space. It occurs from life, lingering as its static, visible artefact. The body’s interaction informs the structuring of mess and the continual cycles of its birth and renewal. The project, situated within the social heart of Sydney’s CBD explores the city’s squatting landscapes and incidence of homelessness, artistic and ‘untidy’ spaces and forms of urban expression revealed through the city’s fabric. The range of mediums involved in the project’s output explore architectural, social, technological, and representational dilemmas. The investigation looks within the trajectories of accumulation and the inevitability of a dirty world, operating within an ecosystem of dust, dirt, people, and architecture in the consideration of gestures of care, repair, and maintenance that may inform active and decolonised relationships to architecture.

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

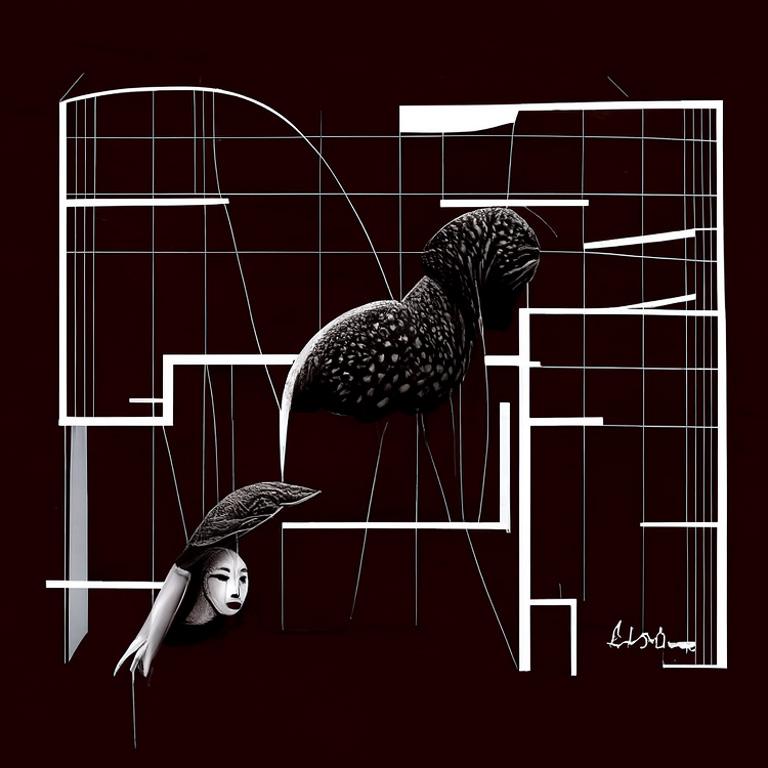

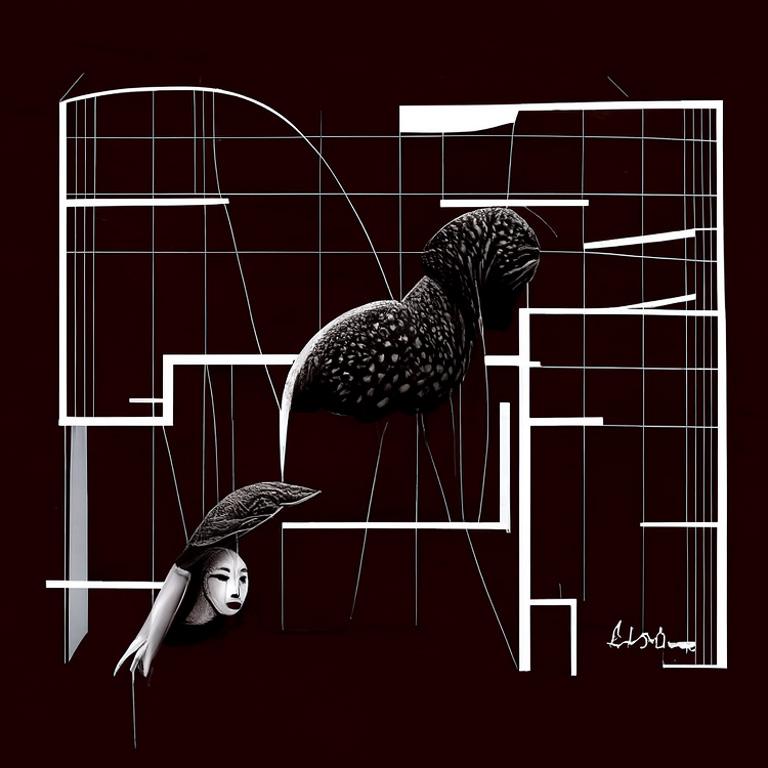

Do AI dream of electric sheep?

Kangcheng Zhang

Do AI dream of electric sheep? The short answer is yes. AI has learnt to with our mementoes, with our most obscene desires. Like Dadaism and Surrealism, the result of the Convolutional Neural Network often presents us with an uncanny scene of dislocation, juxtaposition, and transformation of symbolic images. By short-circuiting the AI, we can use it to embody architectural design with a higher degree of spontaneity and automatism to paranoically re-imagine an art space of torture and terror. As a result, the architecture of surrealist objects is a mediator to psychoanalyse and decipher our collective dream.

56

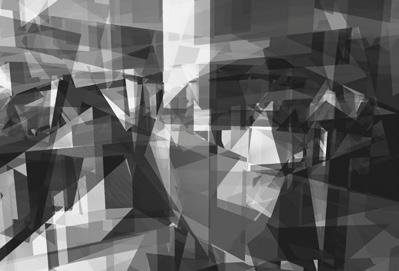

Glitch

Lily The Aye Tha

The digital glitch is random and chaotic. It pierces the veil and, “exposes societal paranoia by illustrating dependence on the digital”[1], a paradigm rooted in the fear of system failure. As Paul Virilio stated, “The invention of the ship was also the invention of the shipwreck.”[2] This project is a documentation of a semesters progress in experimenting with the glitch as an aesthetic concept in Architecture. This process involved three phases – Glitch as Digital, Glitch as both digital and physical, and finally, Glitch as physical.

[1] Jackson, Rebecca. “The Glitch Aesthetic.” Thesis, ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University, 2011. 12.

[2] Paul Virilio, Speed and Politics (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2006).

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

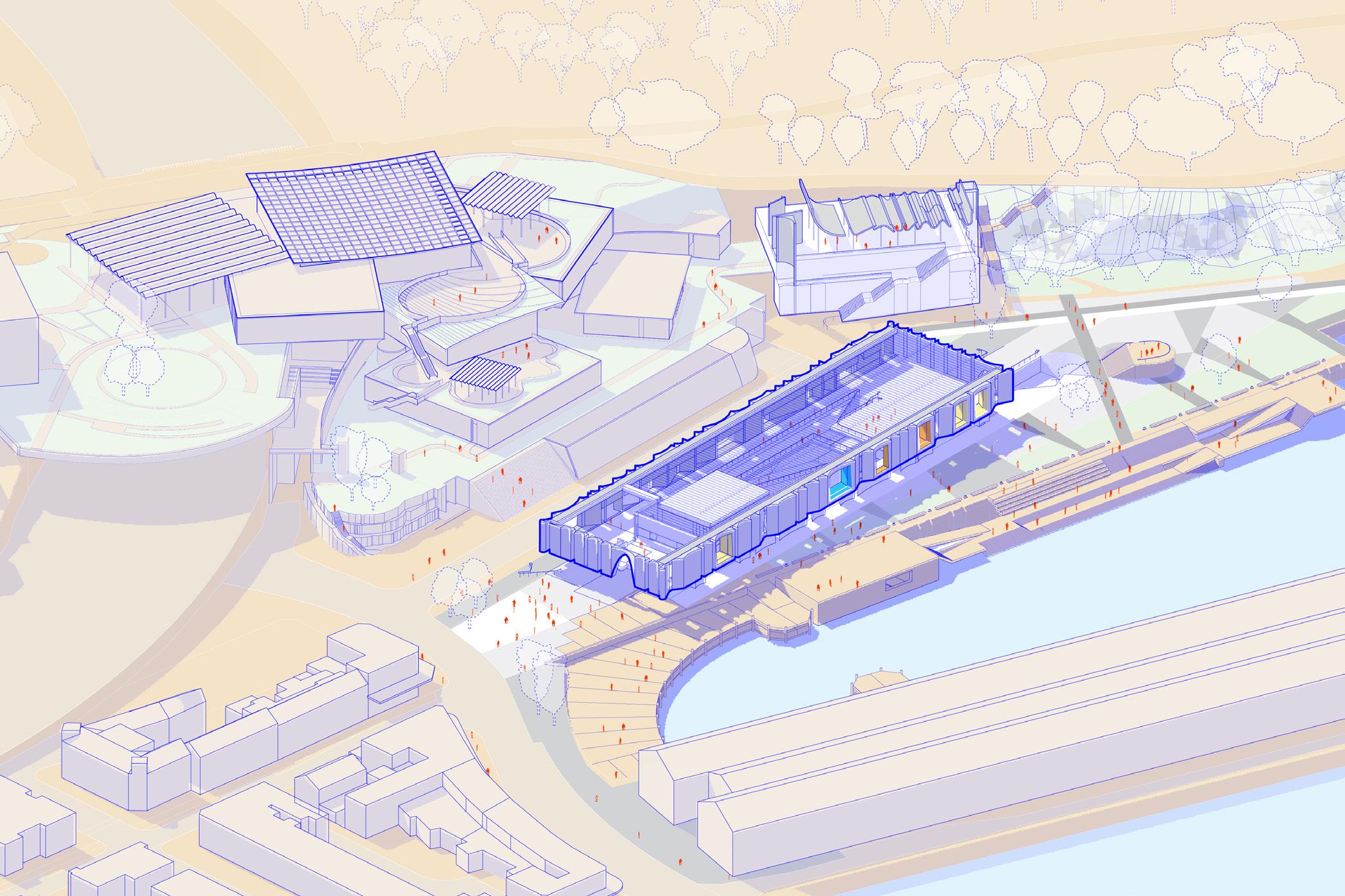

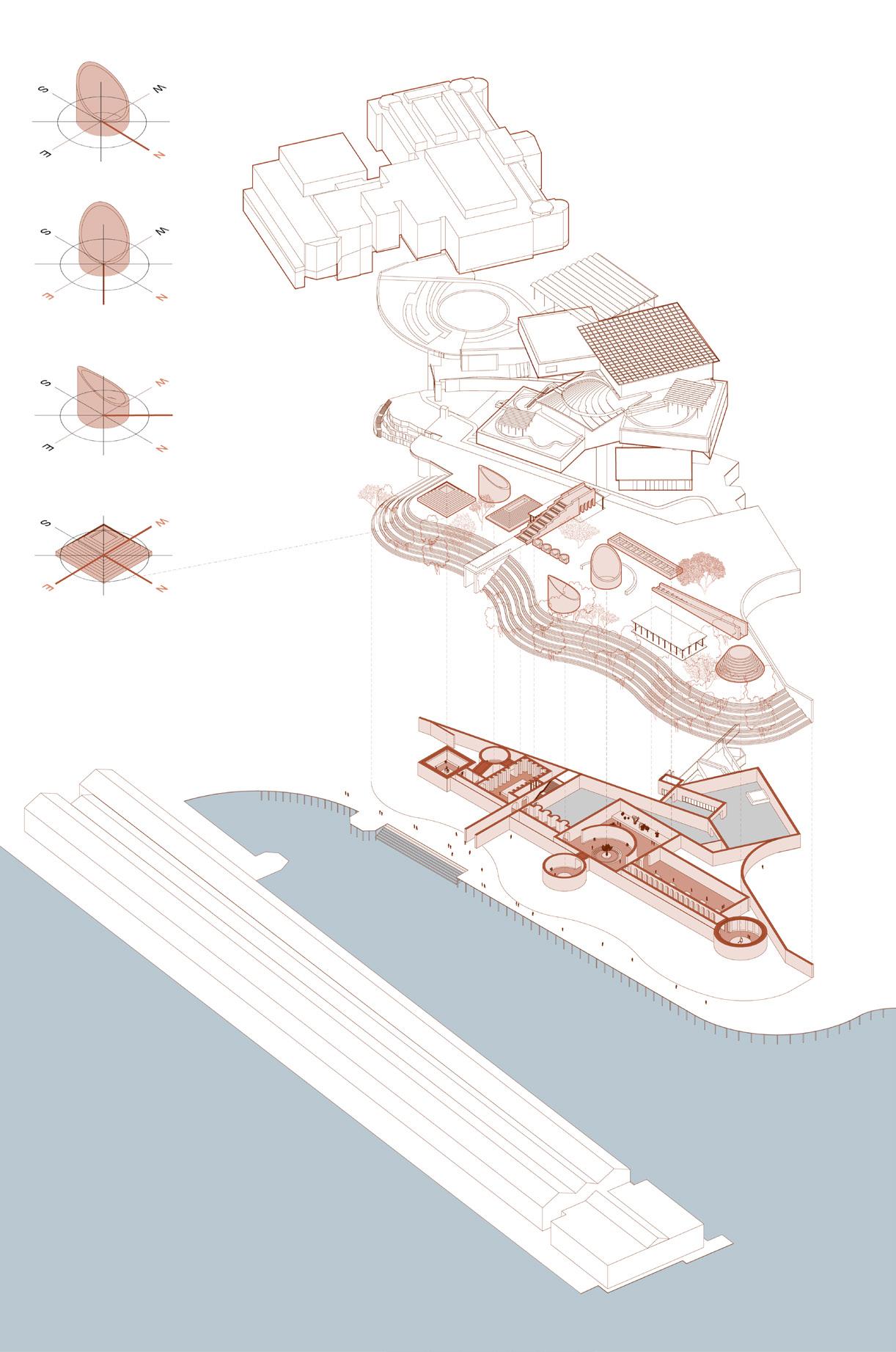

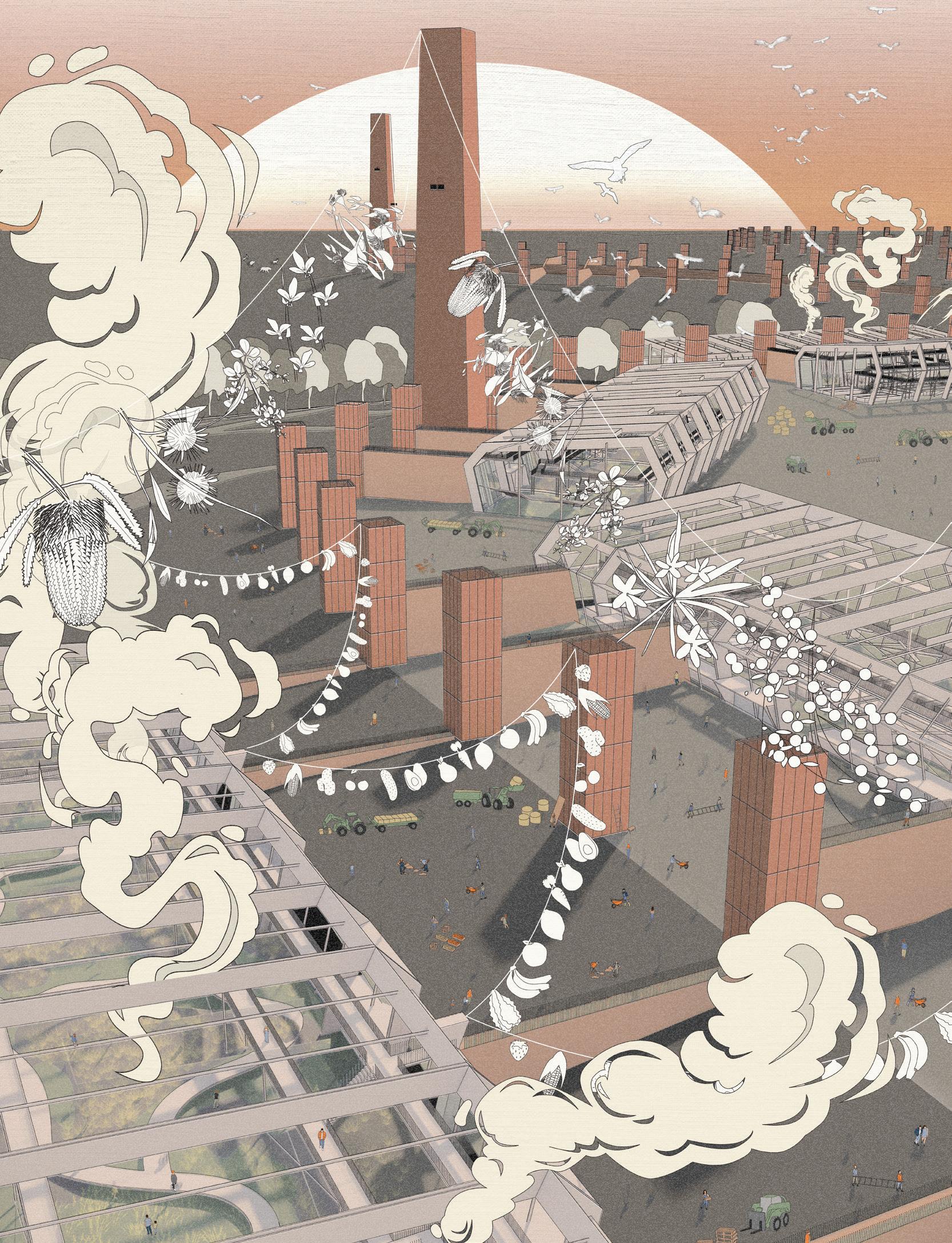

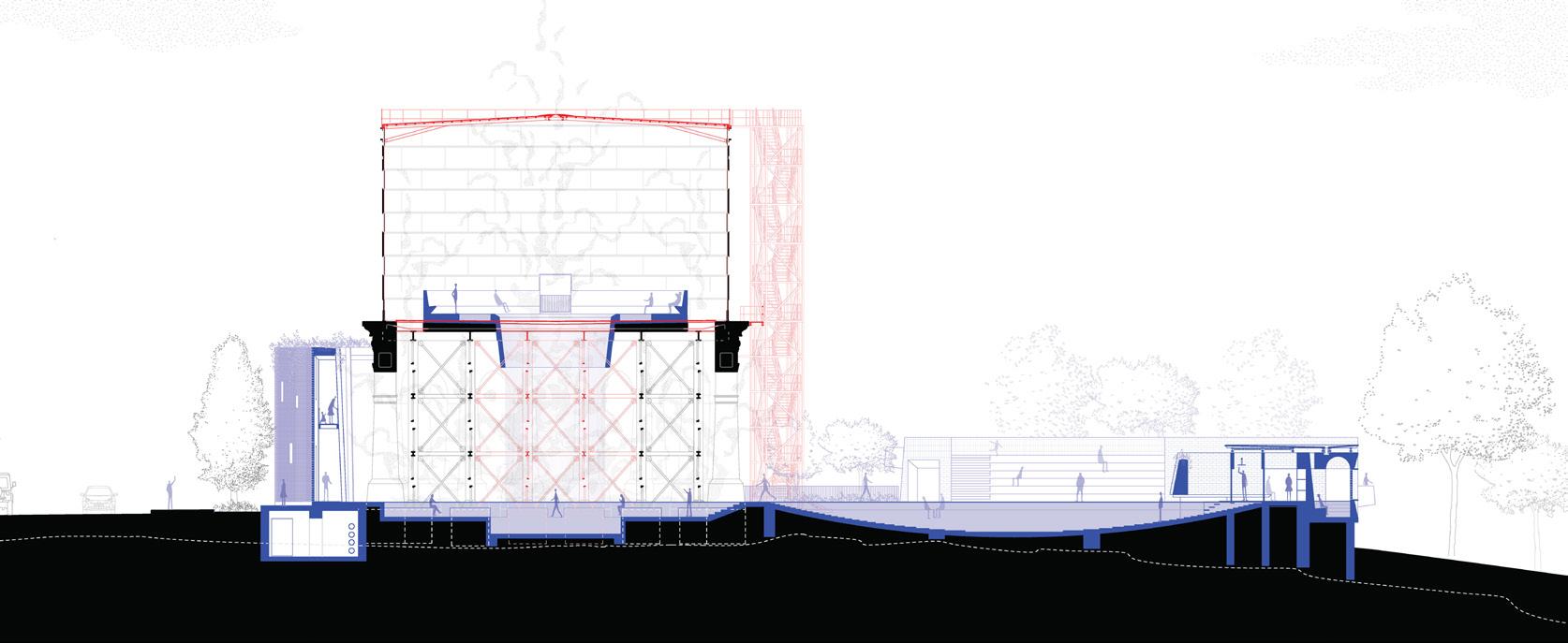

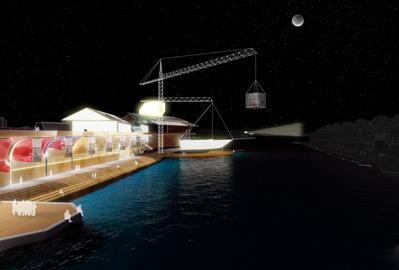

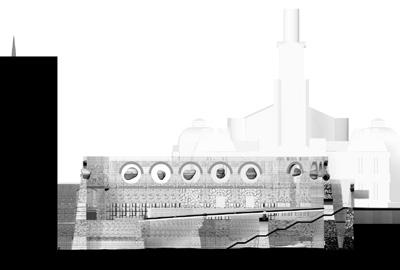

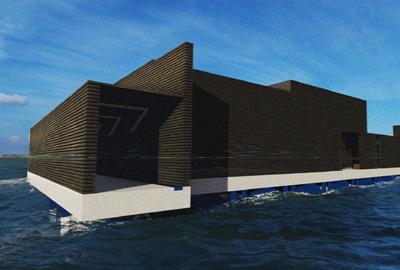

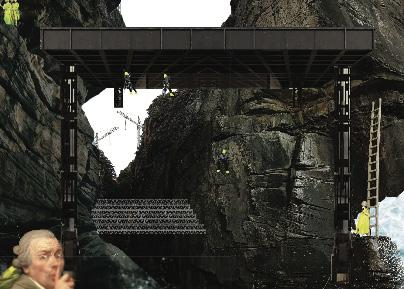

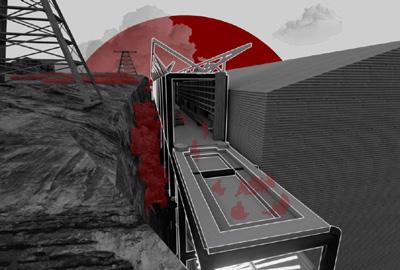

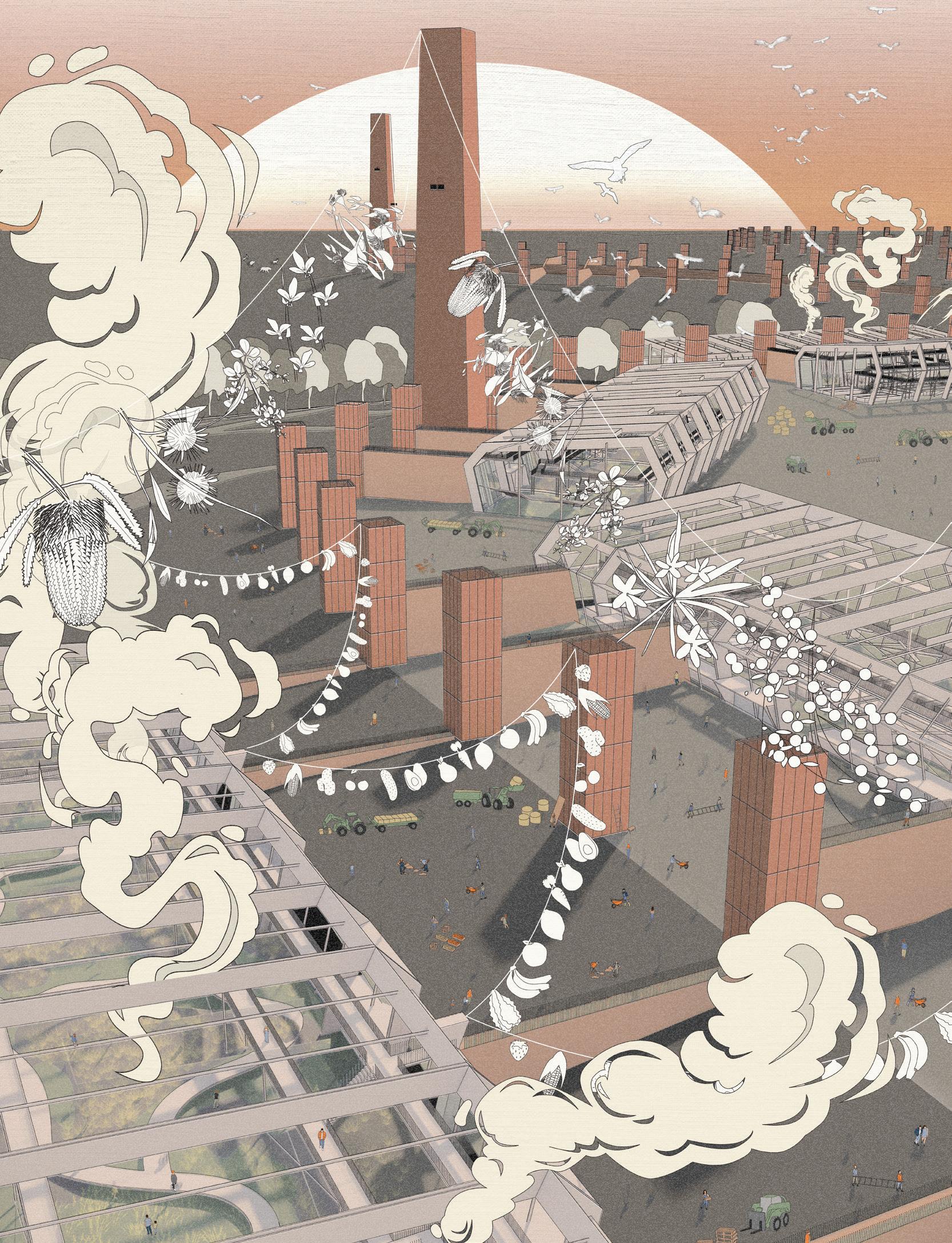

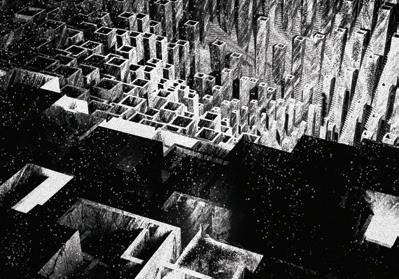

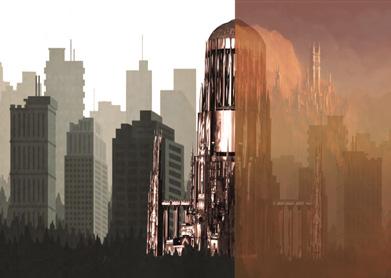

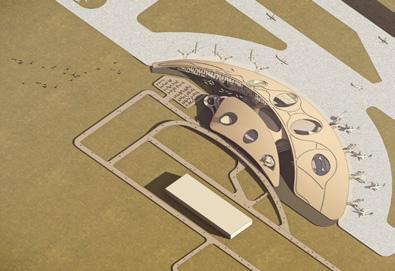

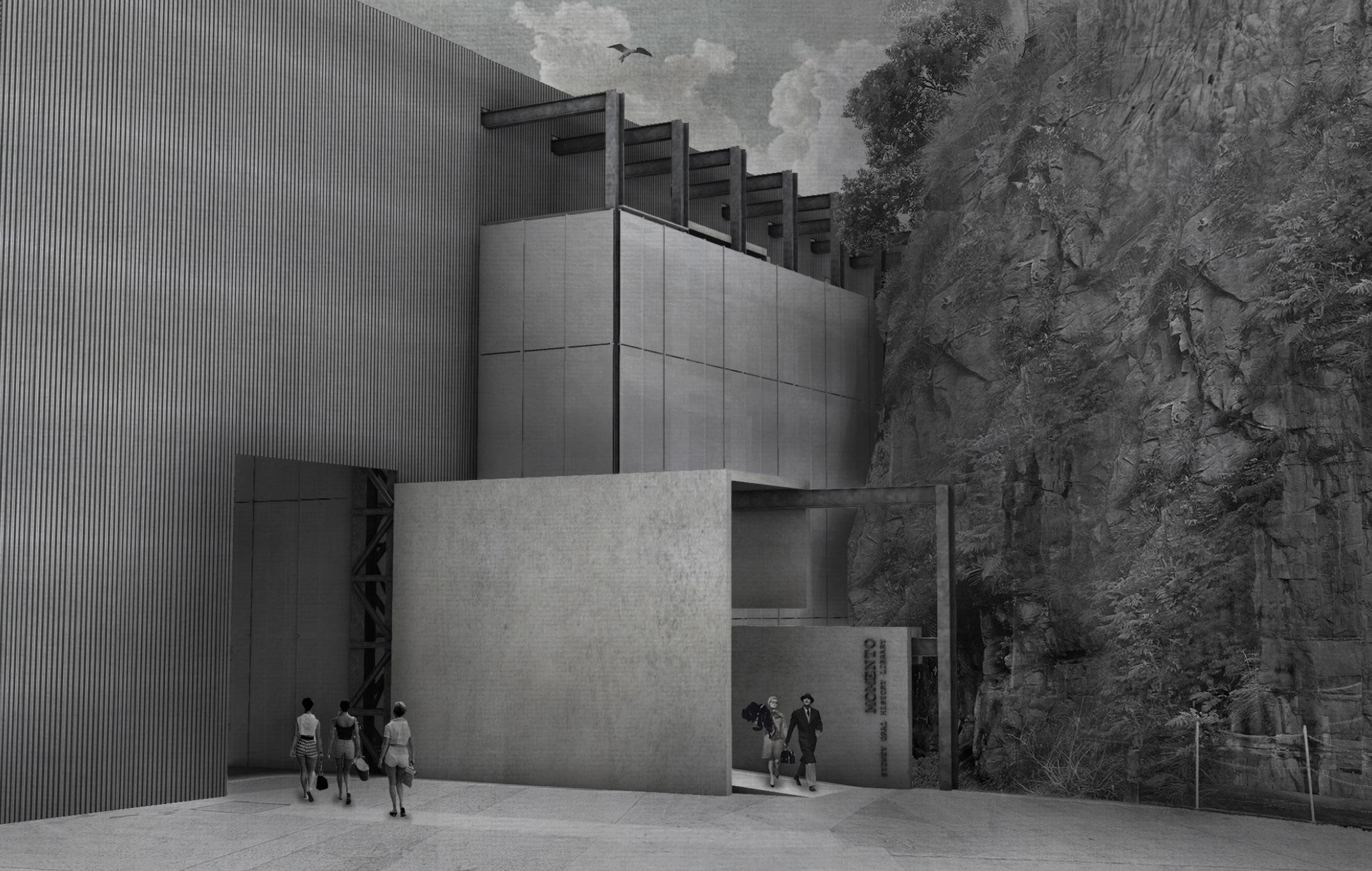

Country Climate Carbon

Thesis Studio

Owen Olthof

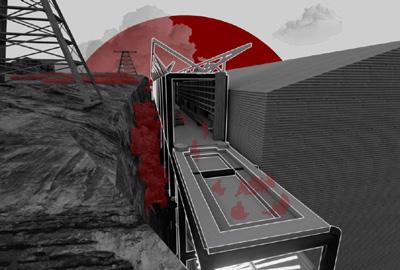

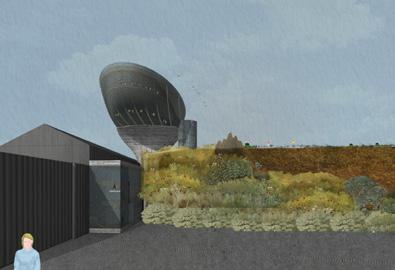

The rapid decline of the fossil-fuel industry has left redundant structures littered across our planet. These relics are a legacy of our industrial past and its damage to the environment. We stand at the precipice of dystopia.

Although these structures remind us of an industry that many of us are ashamed of, it is often forgotten that they also brought pivotal societal changes in terms of economic benefits and new communities. Conversely, the scars left on the land and its indigenous inhabitants are deep wounds that will need to be addressed to reconnect with Country.

One thing is certain; infrastructure can no longer take the approach of mitigation and neutrality. Modern construction has been complicit in the climate disaster and now must actively contribute to combating climate change.

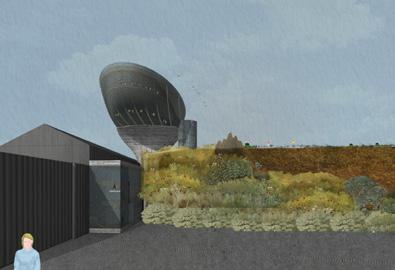

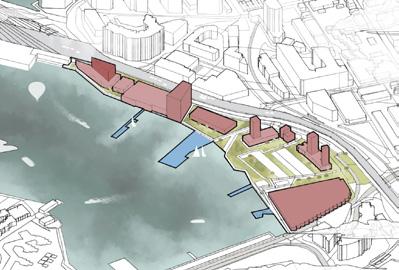

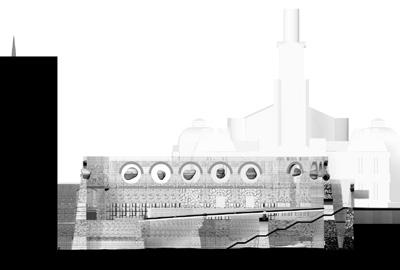

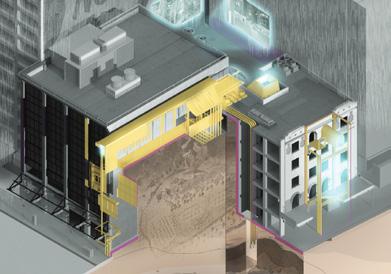

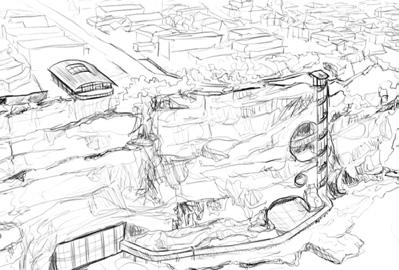

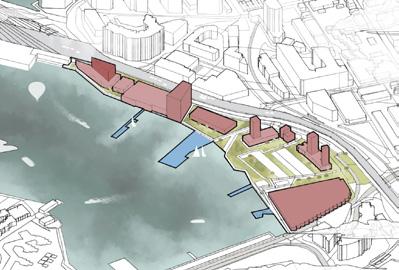

White Bay Power Station, situated at the meeting of gari guard/ nura and nattai gurad/nura (saltwater and freshwater Country) within Gadi/Cadi and Wangal Country, stands as a dormant fossil fuel monument and will be the subject site and focus of this studio.

This studio seeks to explore future directions for our decommissioned industrial heritage. It investigates climatecombating infrastructure initiatives (such as de-carbonising, environmental rehabilitation, etc), to solve the challenges of climate change. How can we reinvigorate our existing infrastructure to positively impact and enrich our communities and the planet?

External contributors and critics:

John Caldwell, Woods Bagot

Sam de Jongh, Woods Bagot

Matthew Fuller, Woods Bagot

Luican Gormley, Woods Bagot

John Prentice, Woods Bagot

Paolo Stracchi, USYD

Amanda Tam, Koichi Takada Architects

58

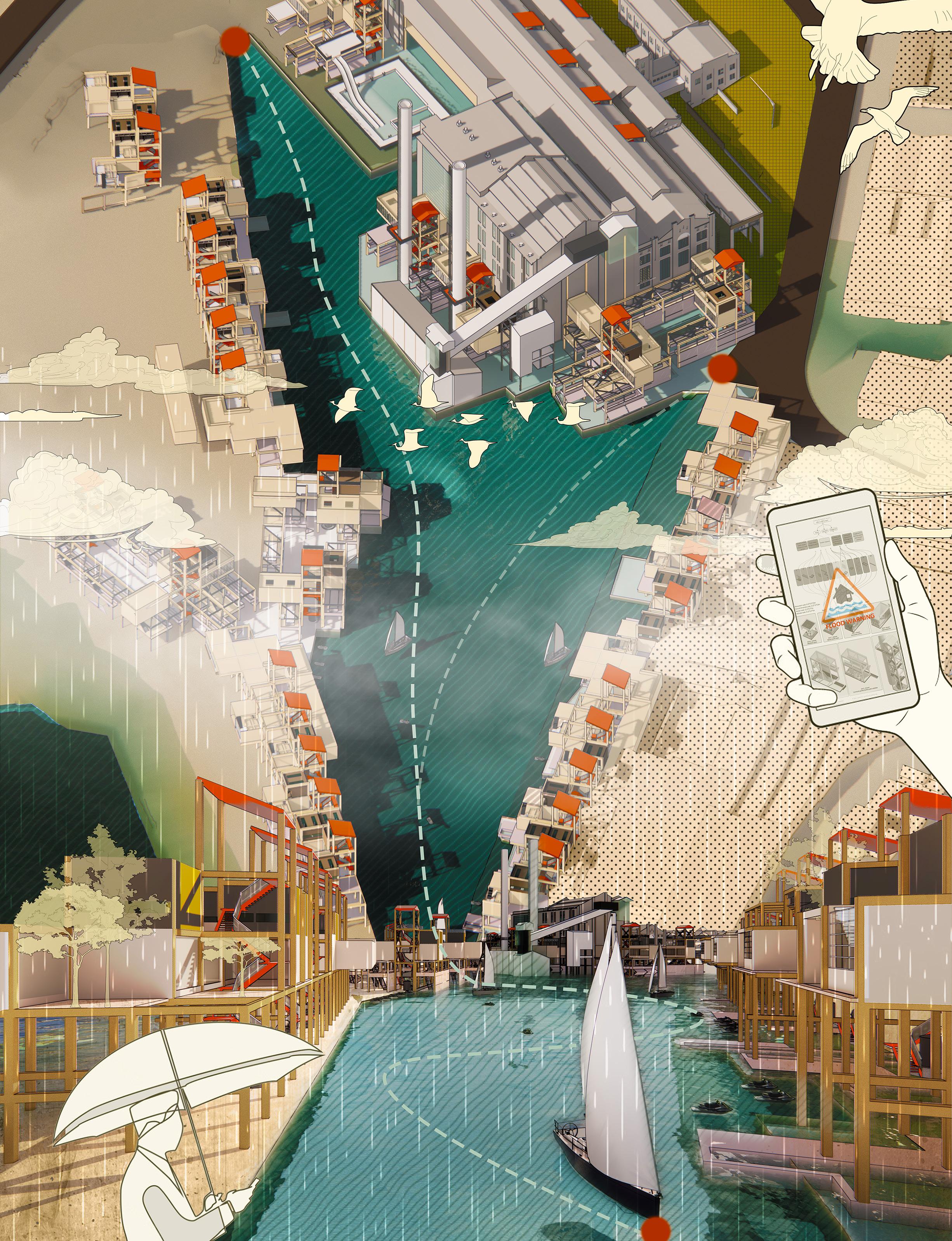

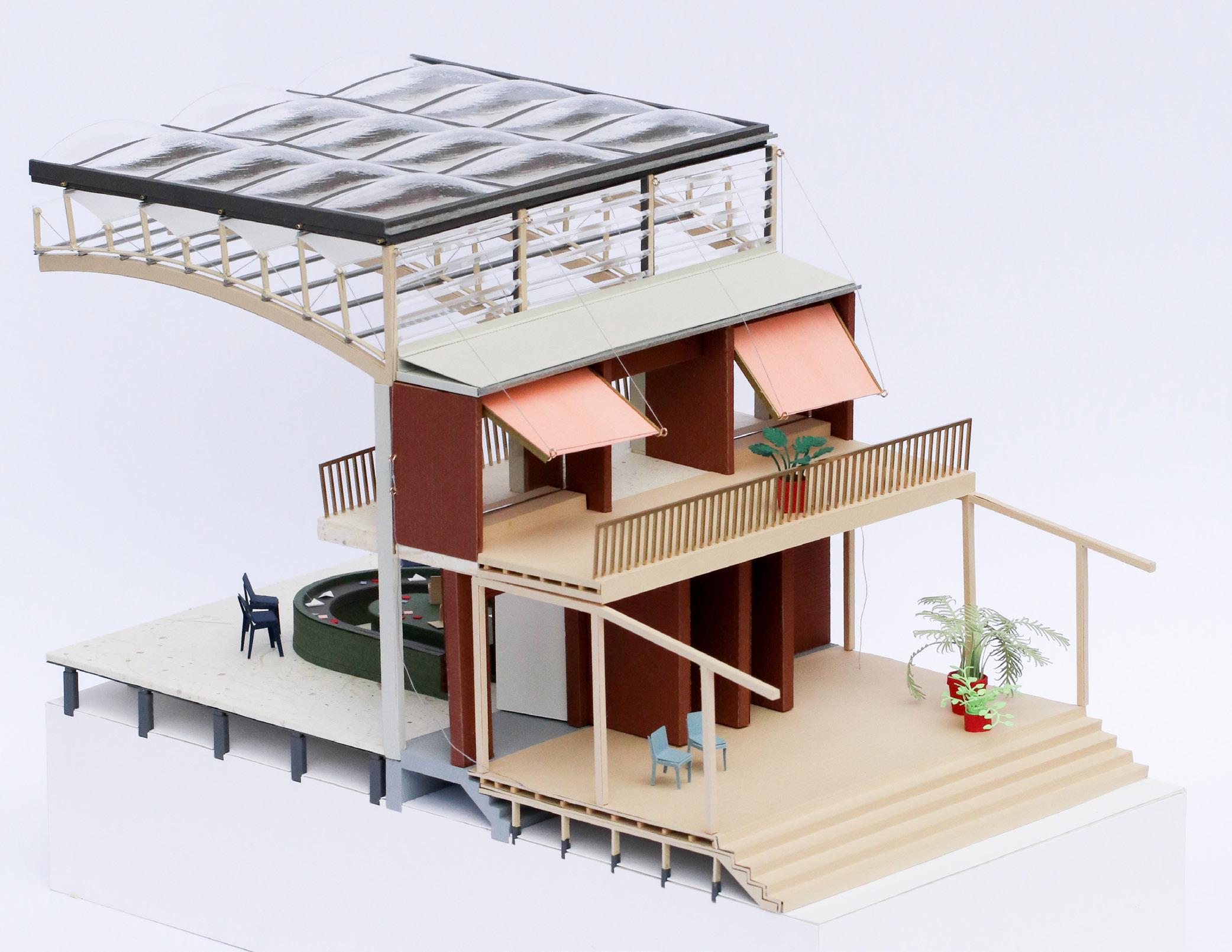

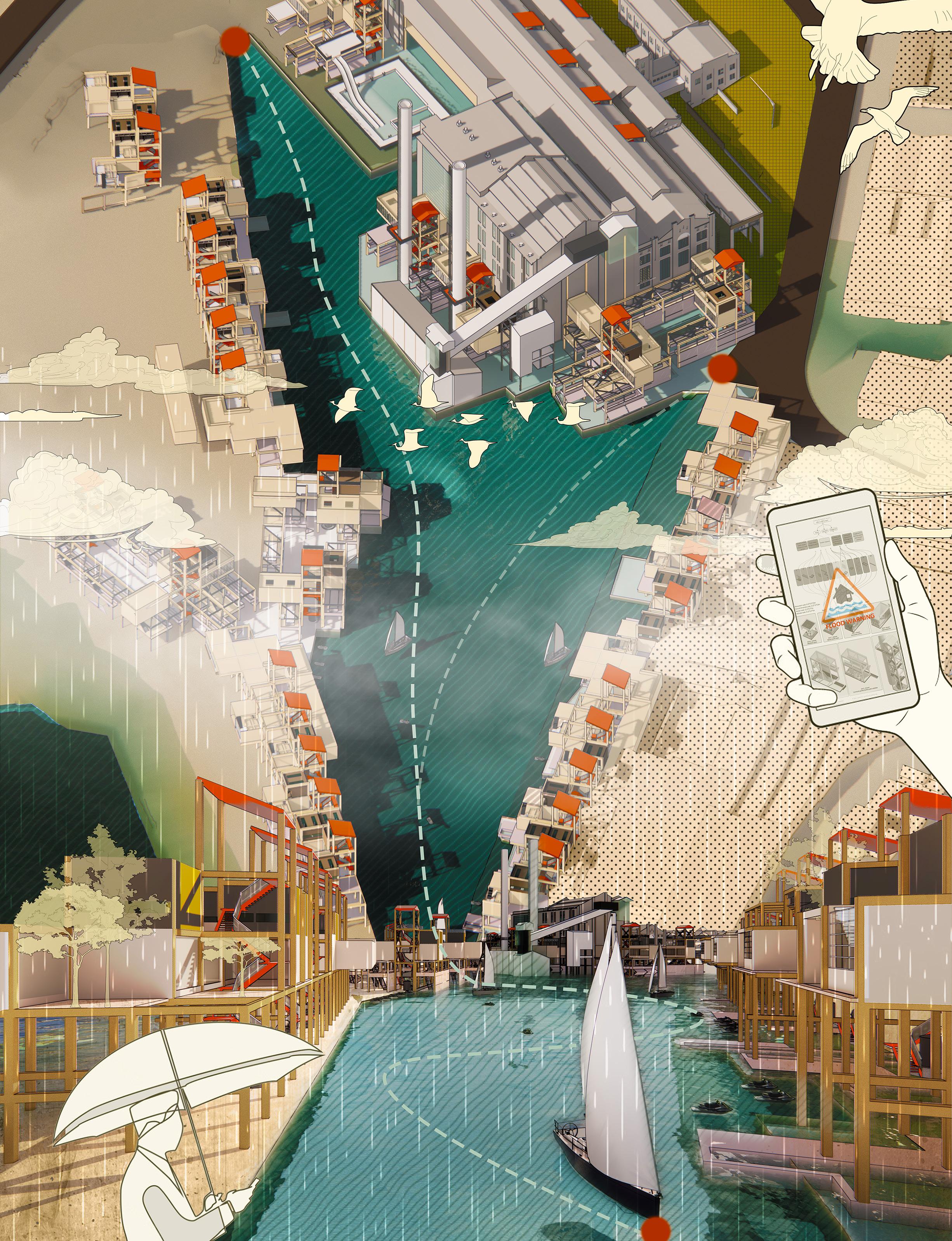

A Resilient Future Zuoting

Li

A Resilient Future is designed to address concerns for climate change and its consequences on mental health. As an experimental renovation, this design explores what architecture can offer to achieve a resilient community. With the guidance of theoretical research on resilience in disaster treatment, the White Bay Power Station site becomes a physical representation of a flood-resilient network in the Rozelle community. It provides a vision of what the potential resilient future would look like with the support of this modular community resilient instrument.

59 MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

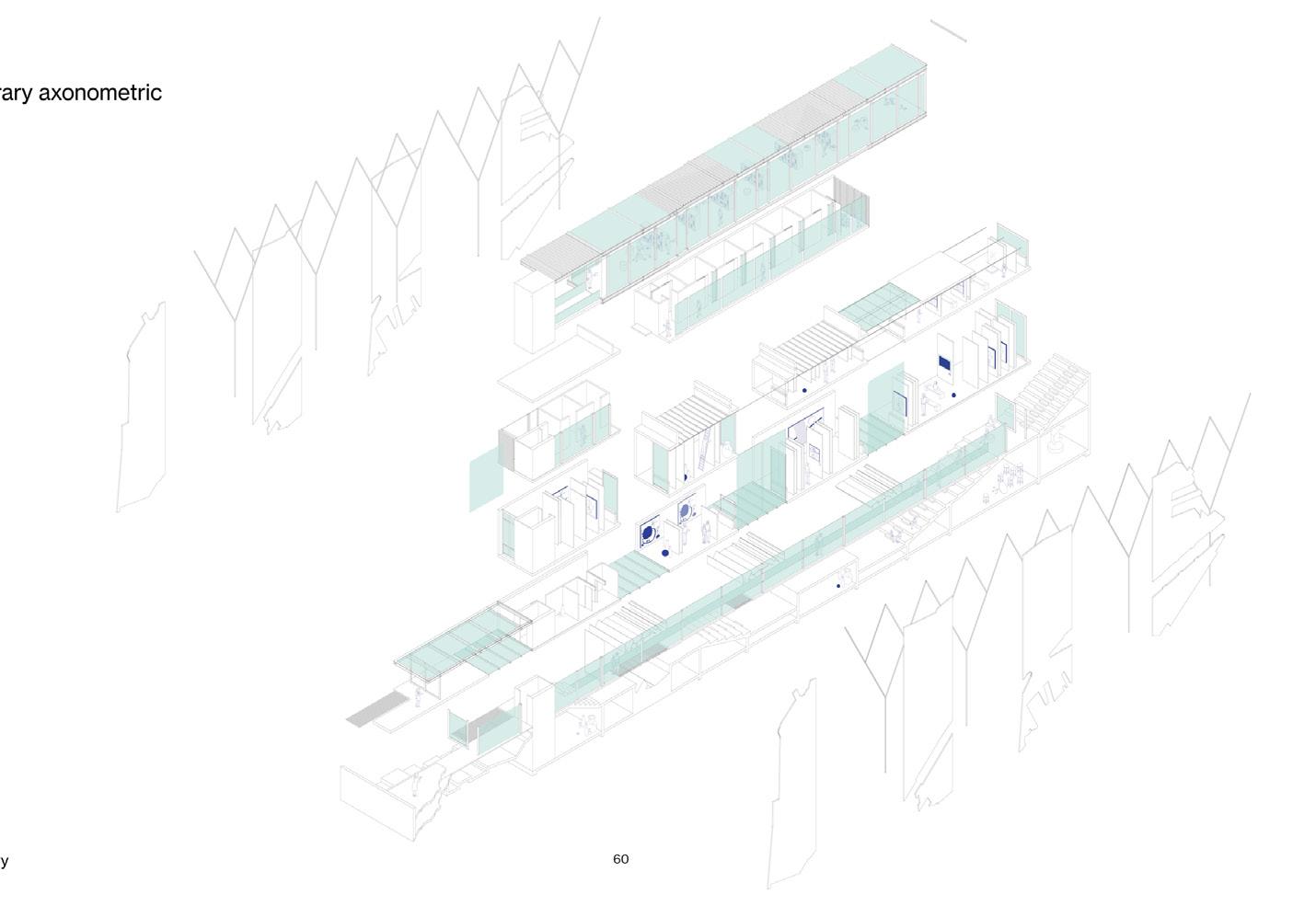

The Museum as a Generator for Sustainable Futures Jessie Mai

As a historical coal-fired power station that once powered Sydney’s railways, the White Bay Power Station is a potent symbol of early industry deeply embedded into the city’s cultural memory. This project proposes the adaptive reuse of the power station as an interactive science museum that educates and entertains. A curated journey through the former power station follows the journey of energy production, allowing visitors to follow the operations of the power station during its heyday. The interplay of old and new elements places the power station within a timeline of technological innovation and progress, creating a space for educating future generations.

60

Ephemeral Yueyun (Rachel) Shen

Evolving from the notions of ‘human absence’ and ‘disordering’ of ruins, Ephemeral aspires to create a botanic industrial ruins park on the heritage site, White Bay Power Station. The concept was stimulated by the desire to establish a balance between the man-made world and the natural environment, which is achieved by the gradual dissolution of man-made structures and the restoration of natural landscapes. Public access will be provided to witness the spectacular reclamation of nature over the heroic heritage building and to retrieve a sense of reverence.

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

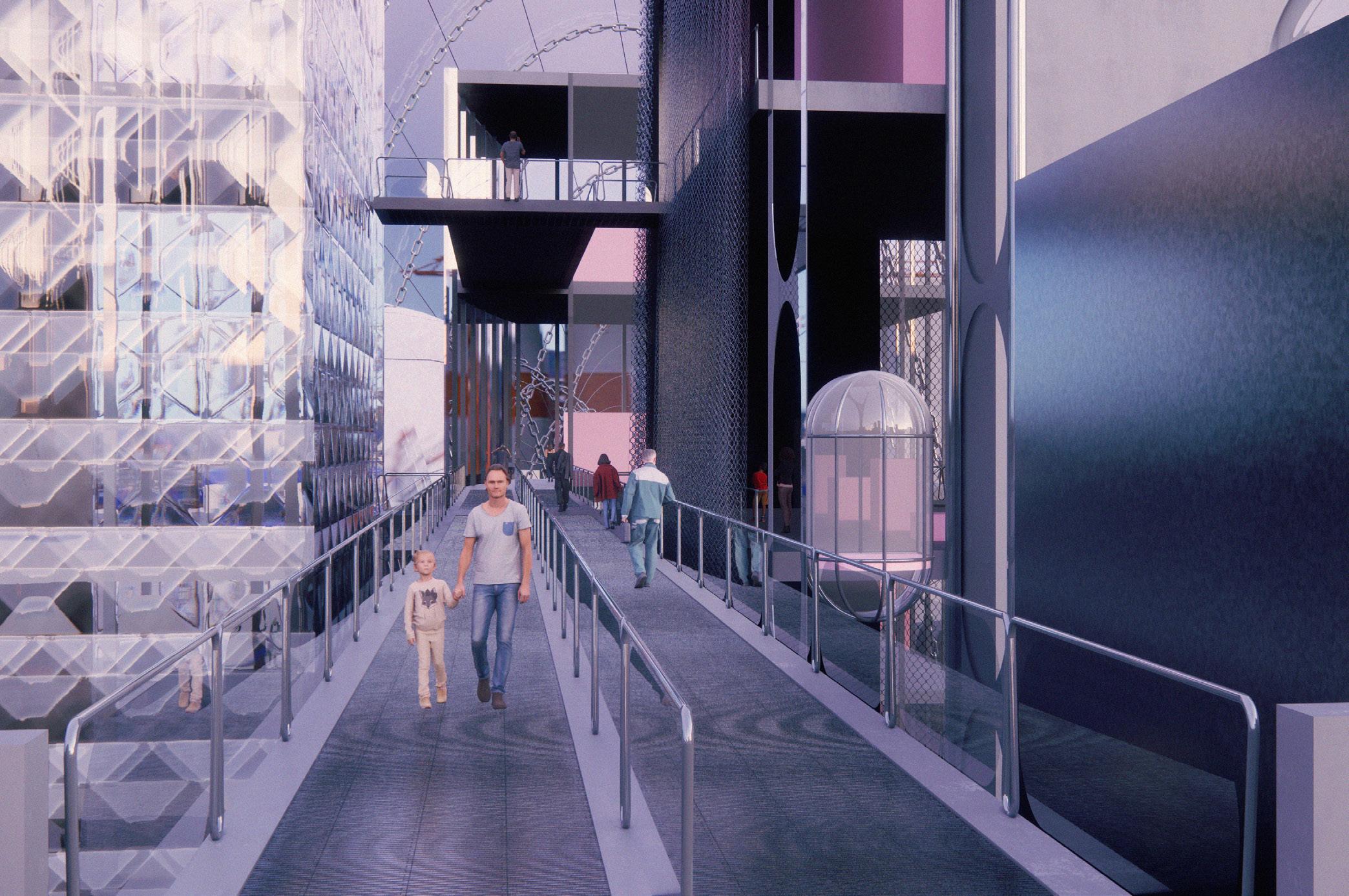

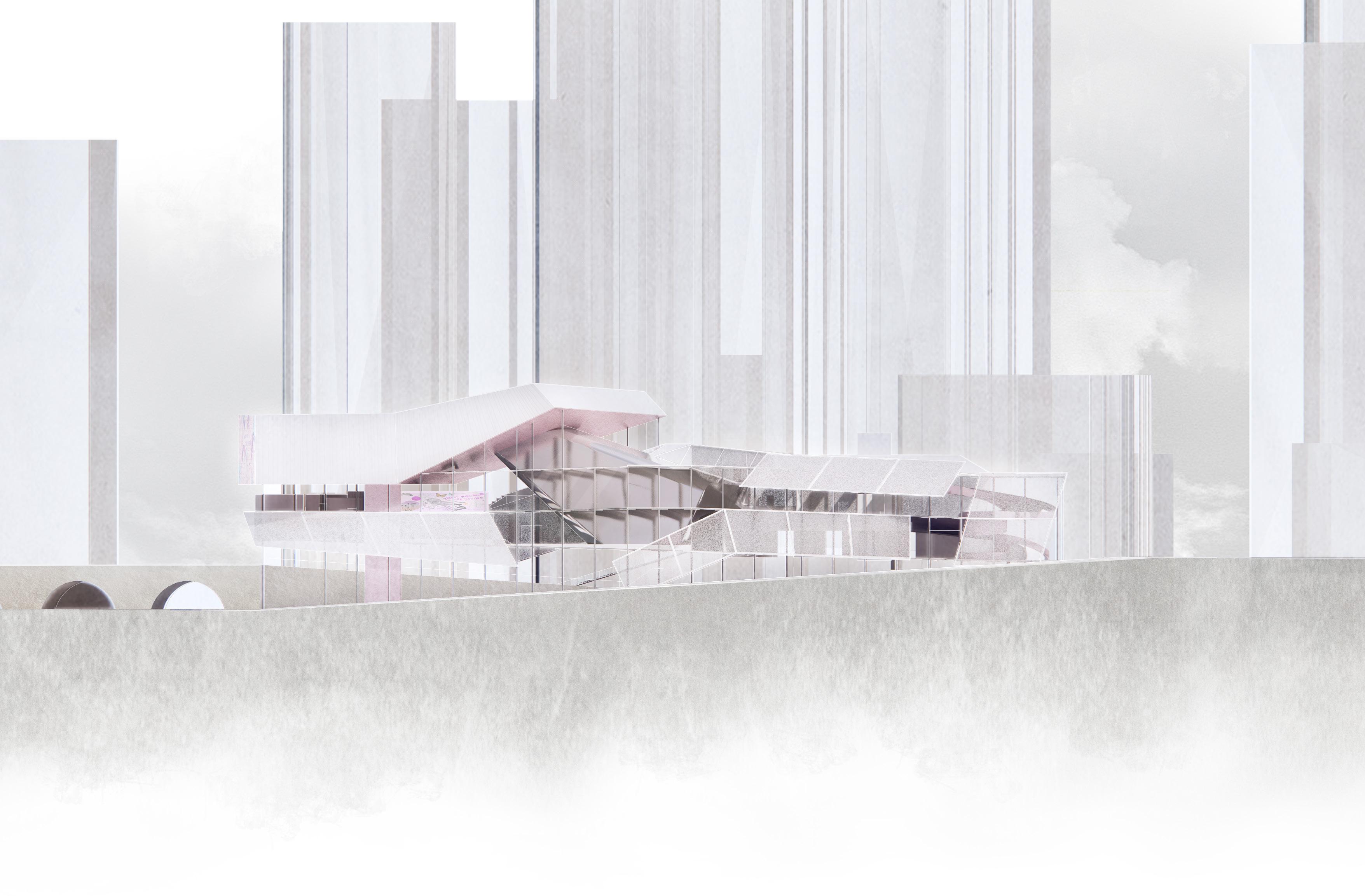

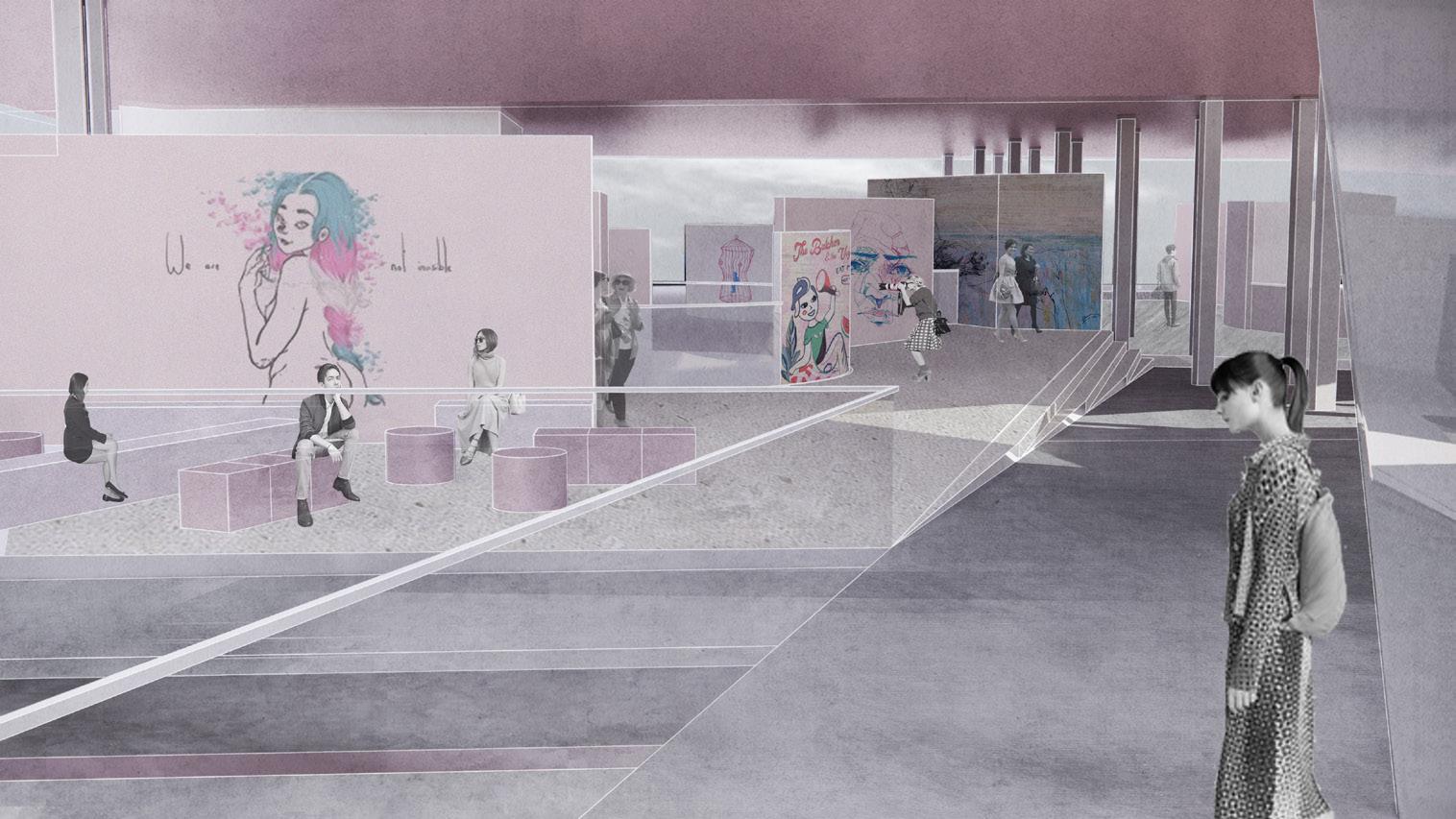

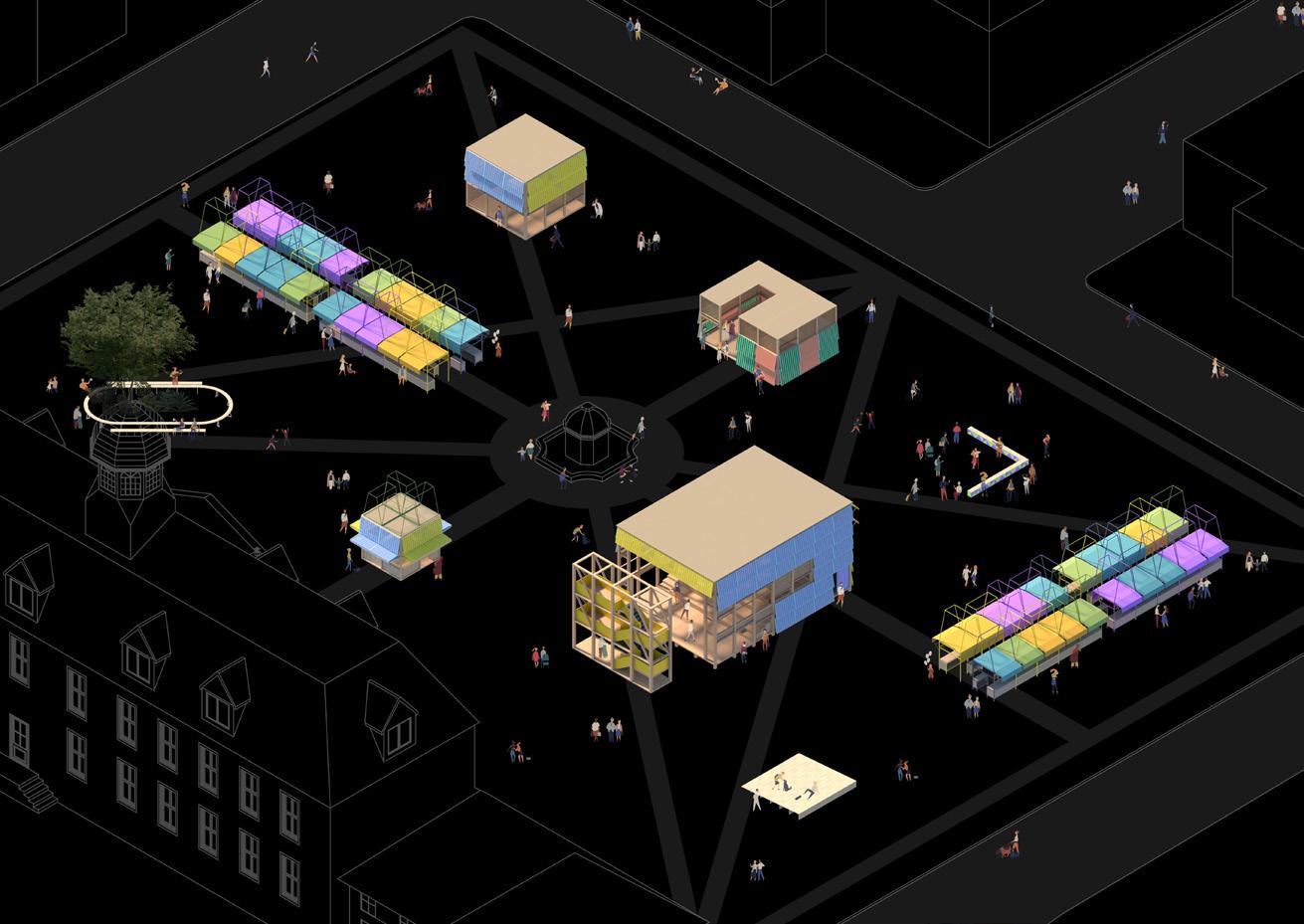

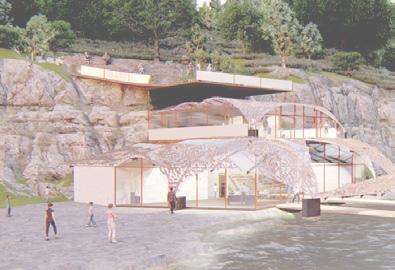

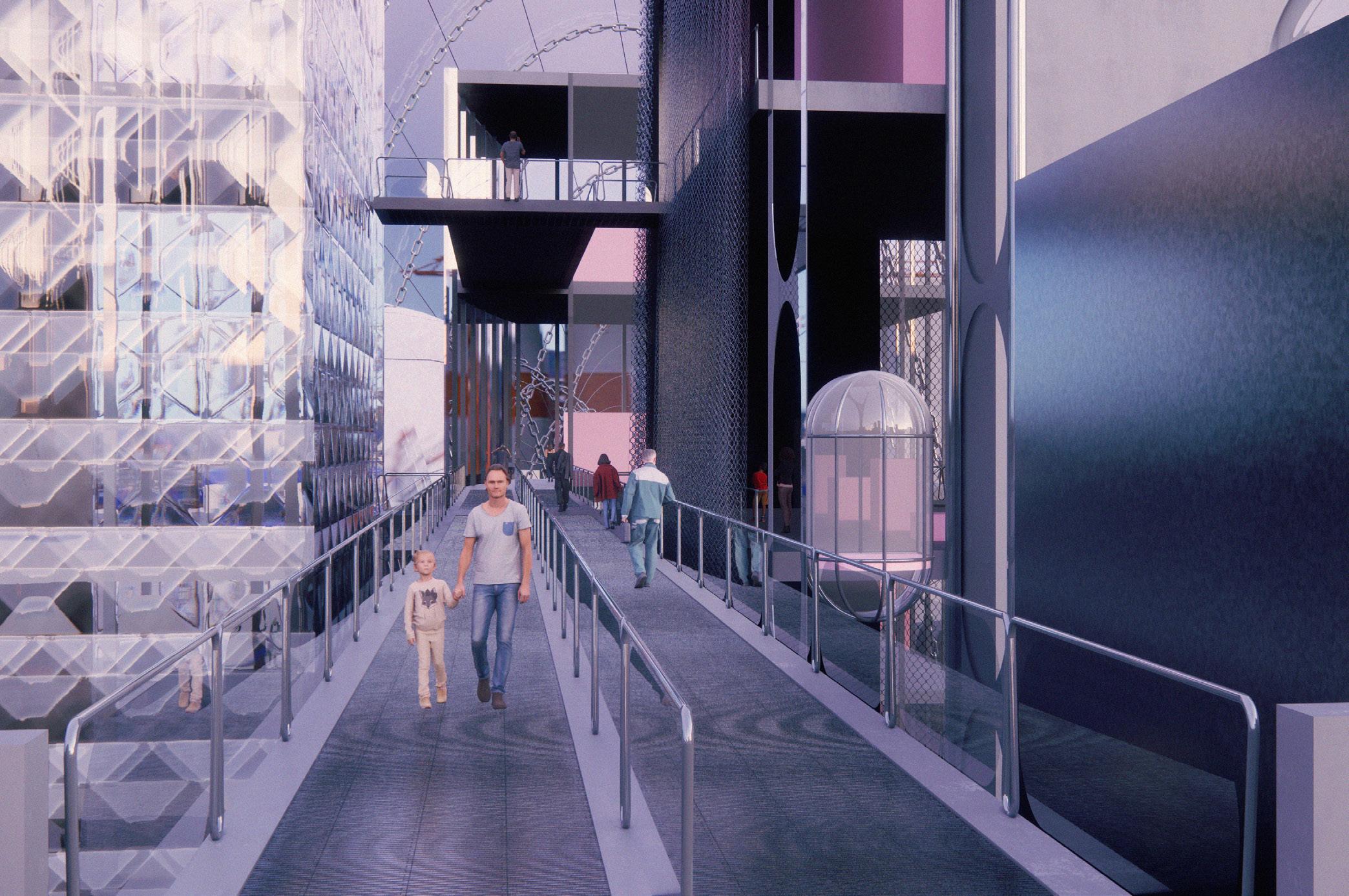

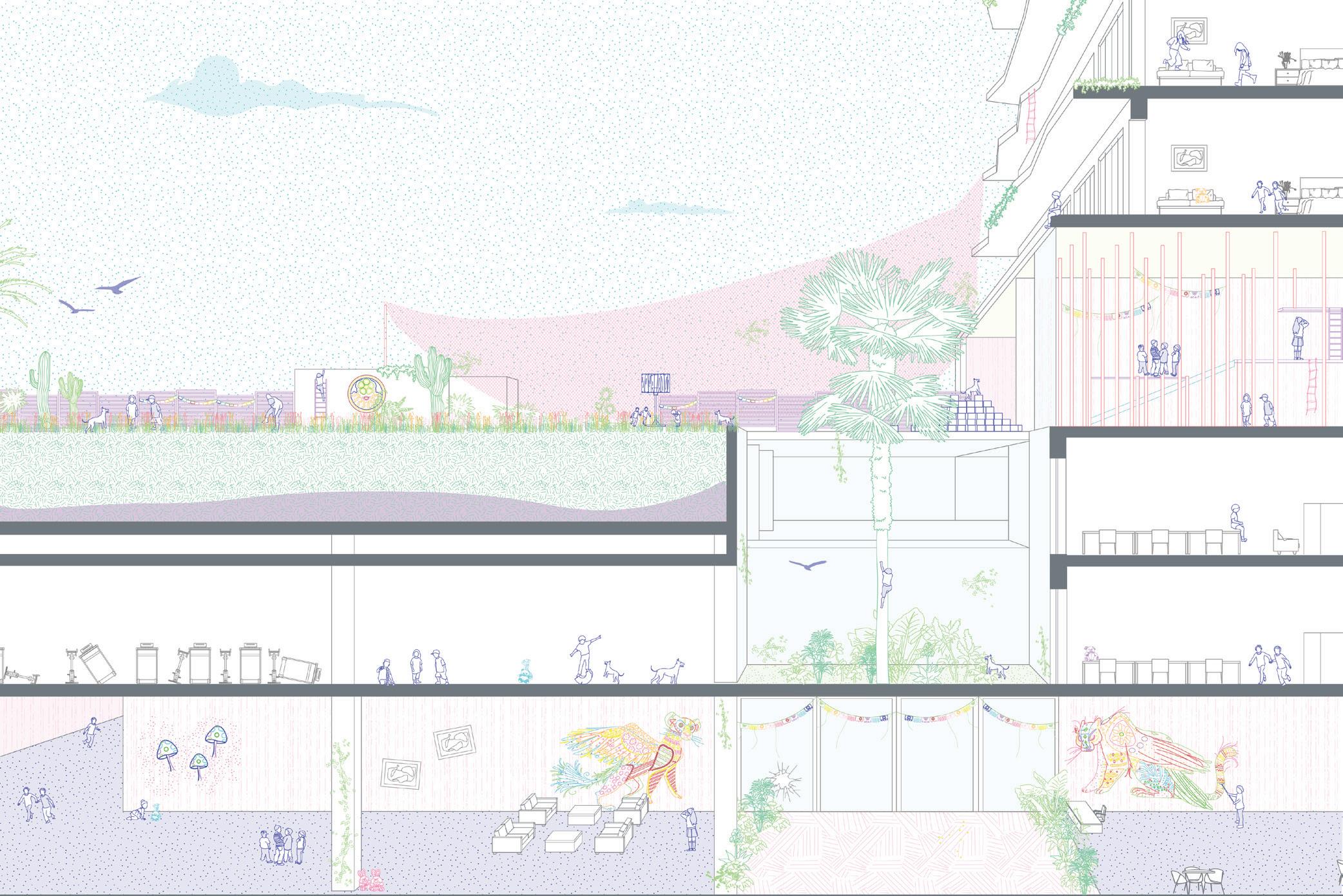

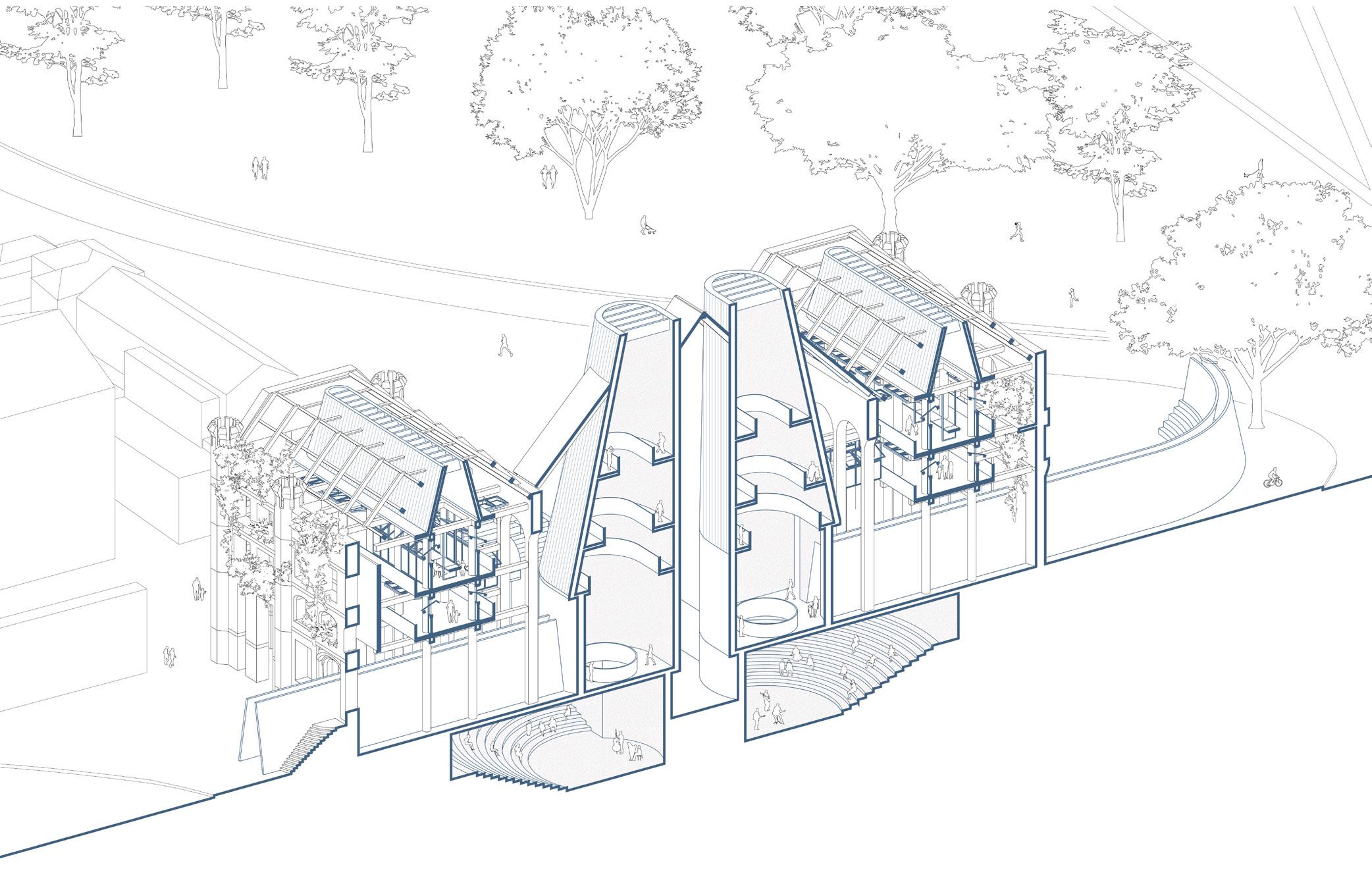

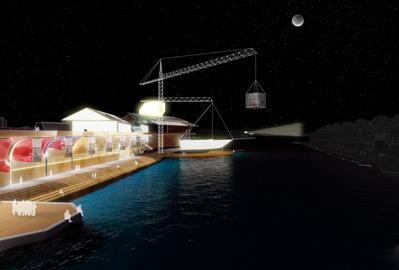

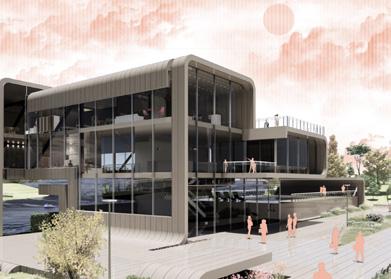

hour Culture Hub

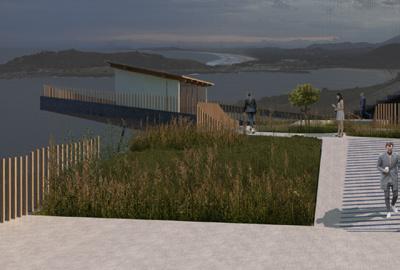

Thesis Studio

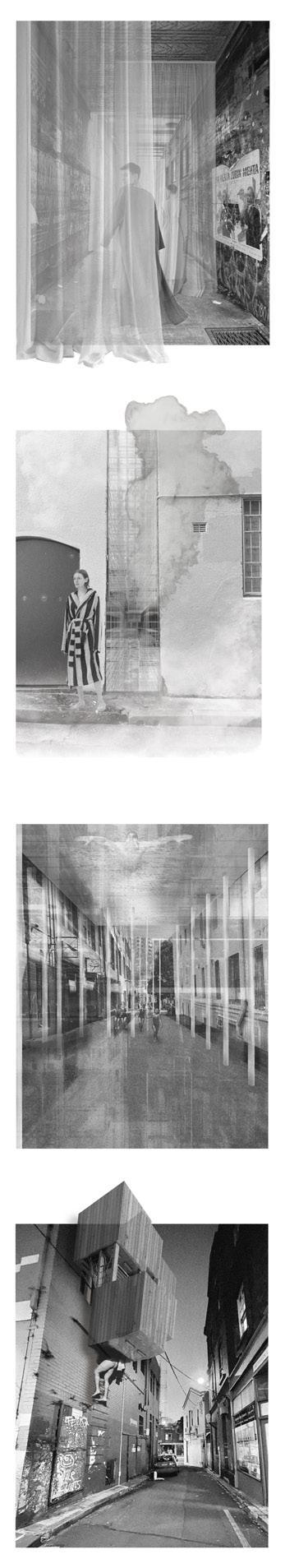

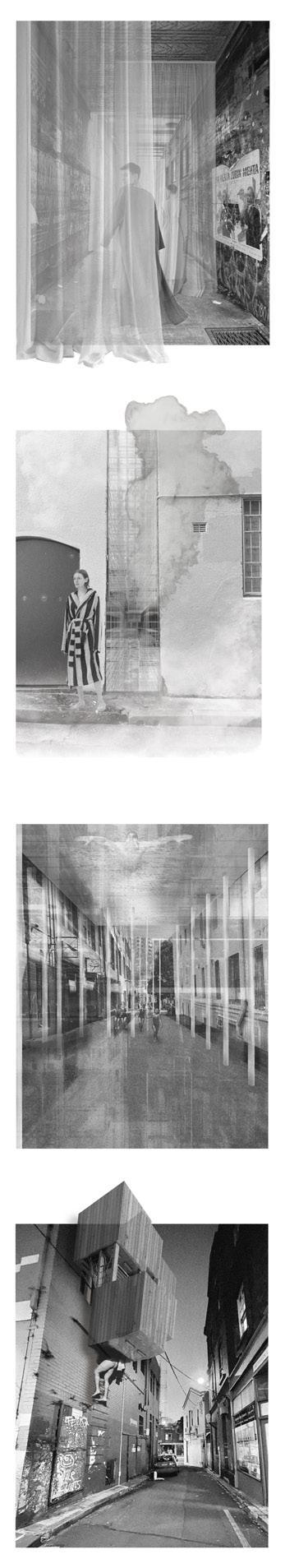

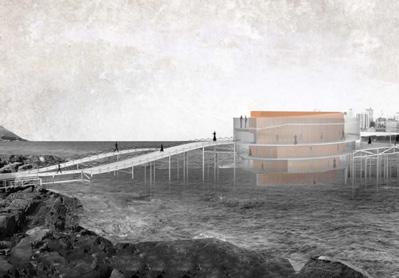

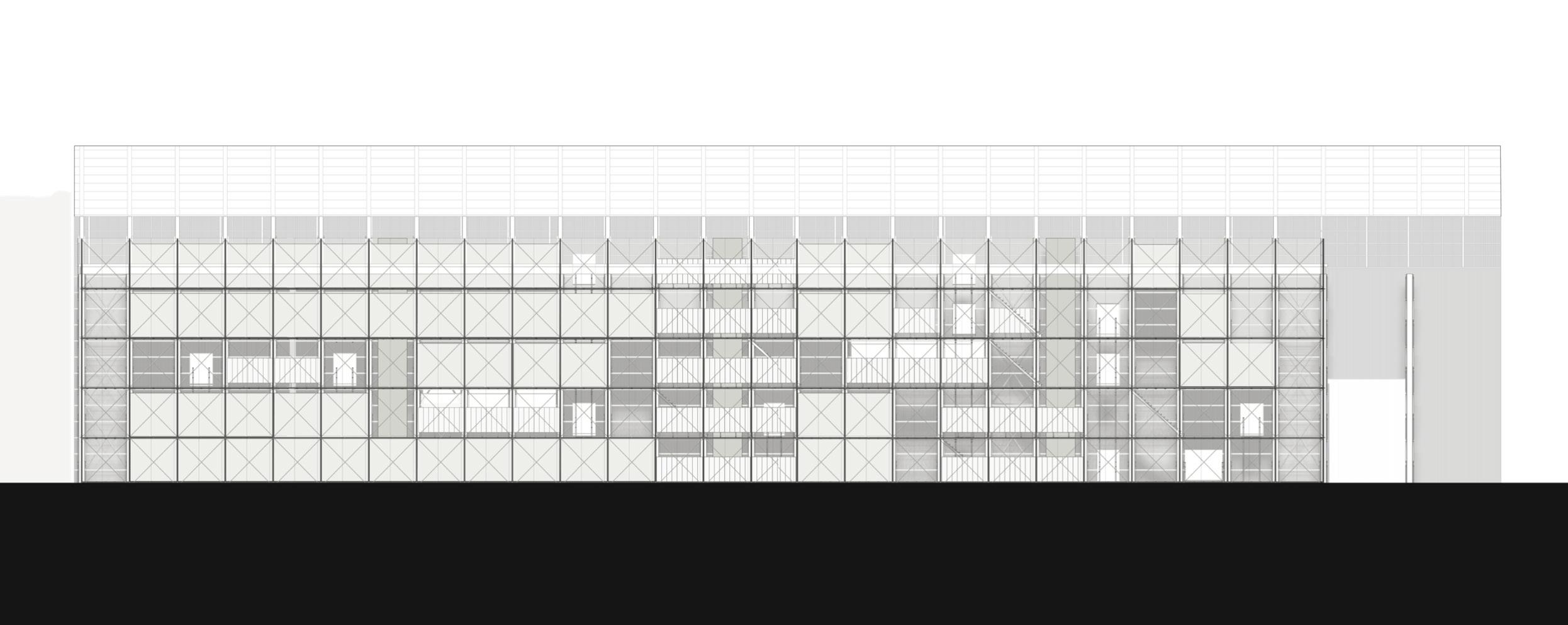

Vesna Trobec

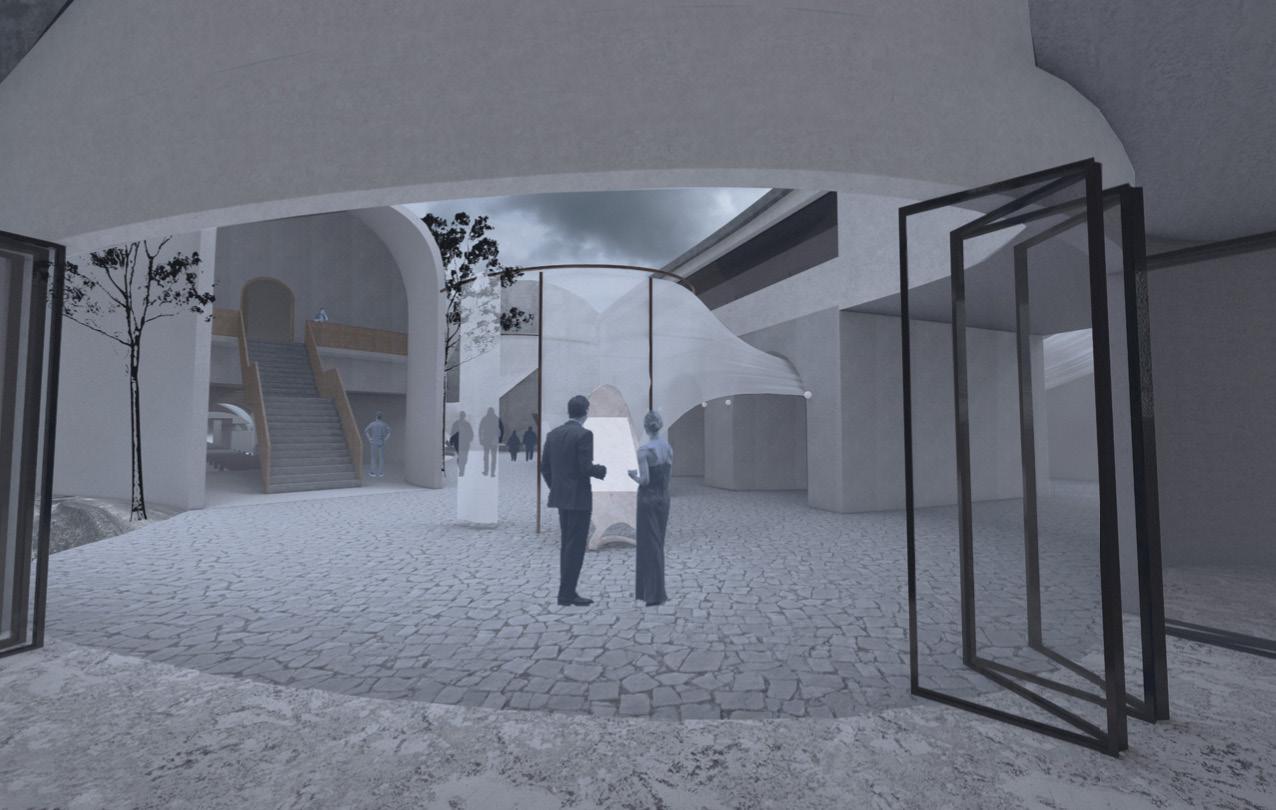

What happens in our city? What and who is found in its “deep interiors”? What parts of ourselves are there? How does architecture and design contribute to the creation of culture?

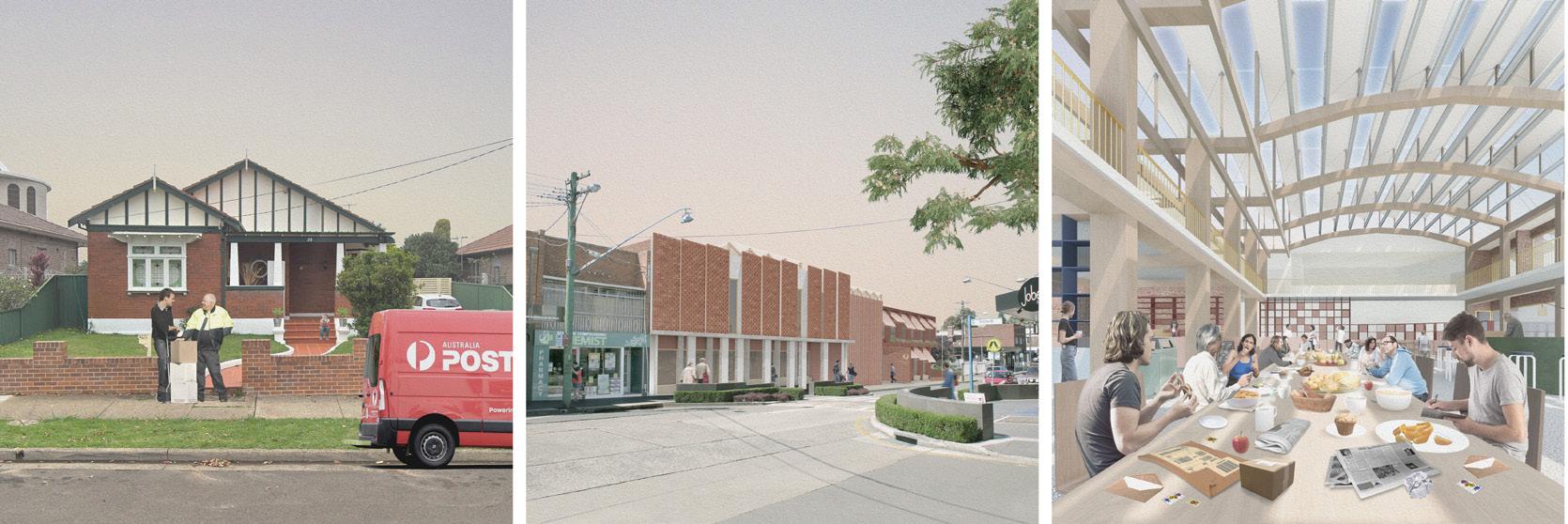

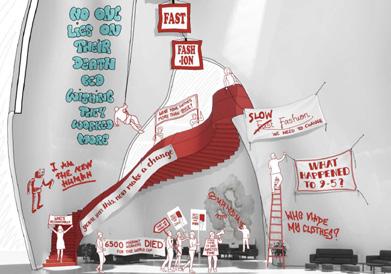

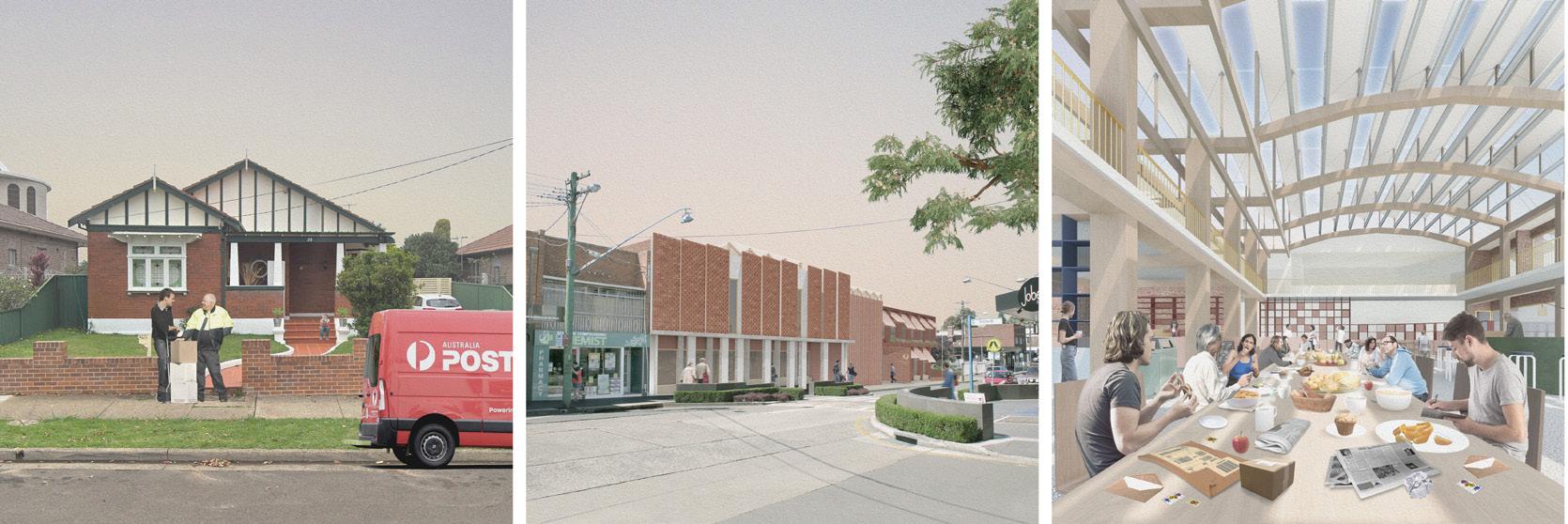

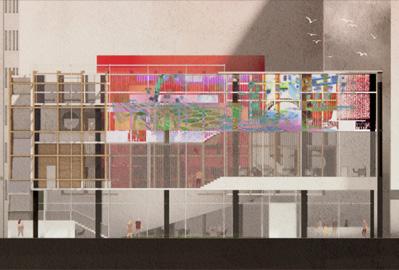

More than 176 Sydney city venues were closed due to the lockout laws that were introduced in 2014. Businesses continue to close today due to the aftermath of Covid lockdowns and other current events. Many more Sydney venues have shut down for other reasons.

People have lost their spaces in the city: the punks, goths, gays, queers, immigrants, insomniacs, teenagers, skateheads, musicians, DJ’s, leather scene, karaoke singers, ethnic minority groups, activists, squatters, students, the middle-aged, the elders, young liberals, kinksters, clubbers, perverts, introverts, gamers, criminals, artists, sex workers, lovers, the broken-hearted, performers, and those who want to eat a meal, drink a coffee, or go for a walk at 4am. Not to mention the Indigenous people for whom the site that is now Oxford Street was a trackway.

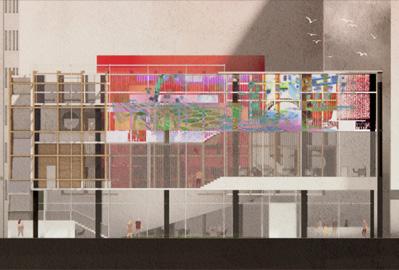

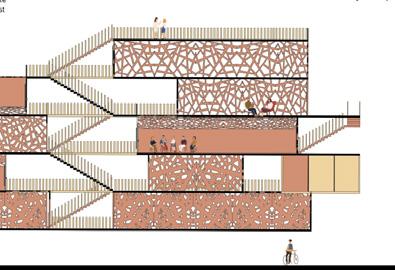

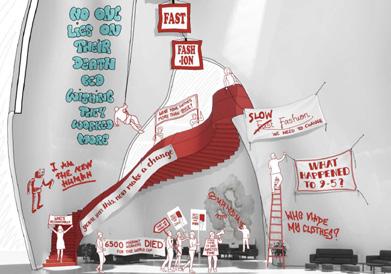

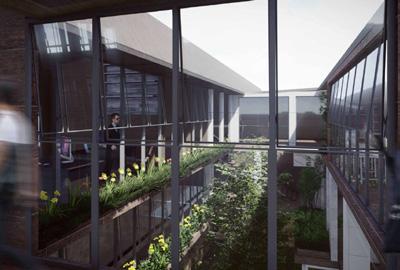

The studio looks at international precedents of spaces that create and facilitate culture in cities. It then researches and maps lost spaces of Sydney city through articles, stories, photographs, music, film and fashion. Building upon this research, a day and night program is defined for a chosen site on Oxford Street. The architecture explores how space is shared, divided, and transformed over the course of the day and the night to create fine-grain in Sydney. Interiors are inspired by the research and program; the elevation could become a kind of “stage” from the street to frame the activities and subcultures within the building. Perhaps there is opportunity for program to “spill out” and further activate the public domain.

External contributors and critics:

Ross Anderson, USYD

Min W Dark, Andrew Burges Architects

Anastasia Globa, USYD

Kate Goodwin, USYD

Olivia Hyde, USYD/Government Architect NSW

Rowan Lear, Tonkin Zulaikha Greer Architects

Jesse Lockhart-Krause, Lockhart-Krause Architects

Chris L Smith, USYD

Lisa Trevisan, Olsson & Associates Architects

62

24

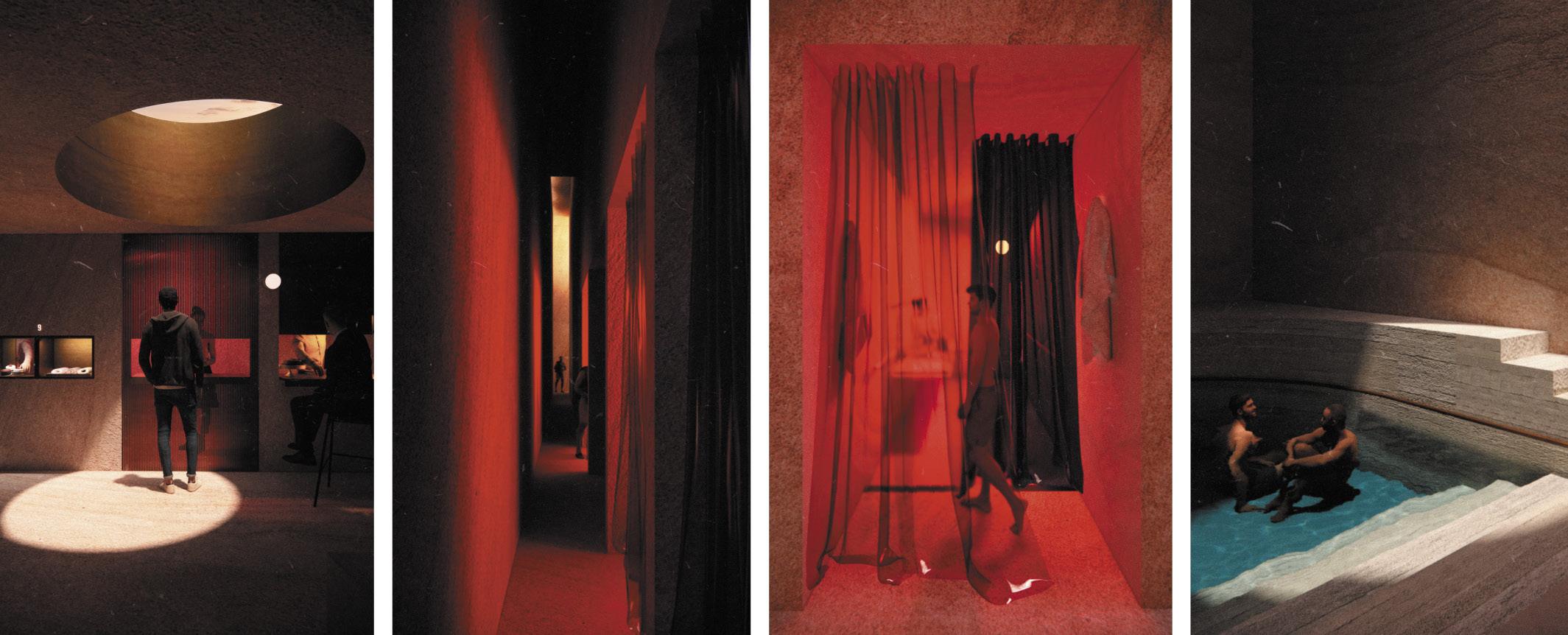

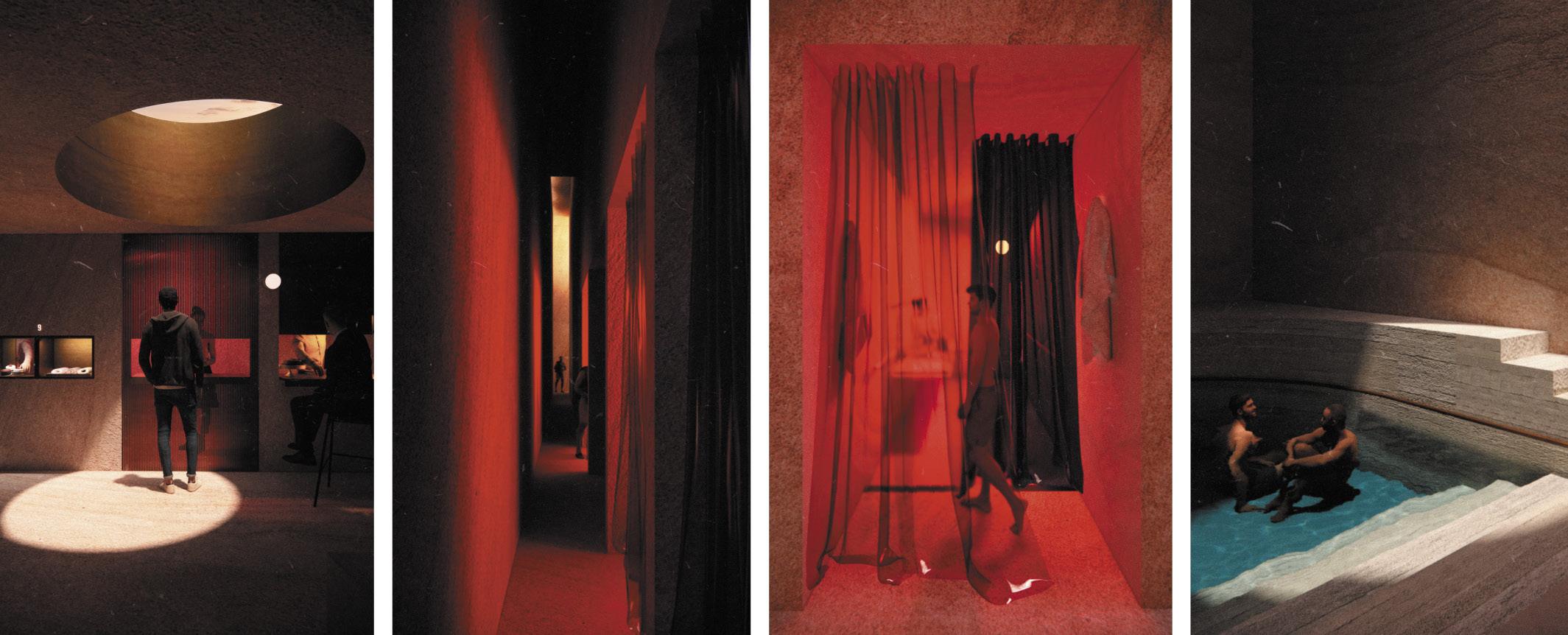

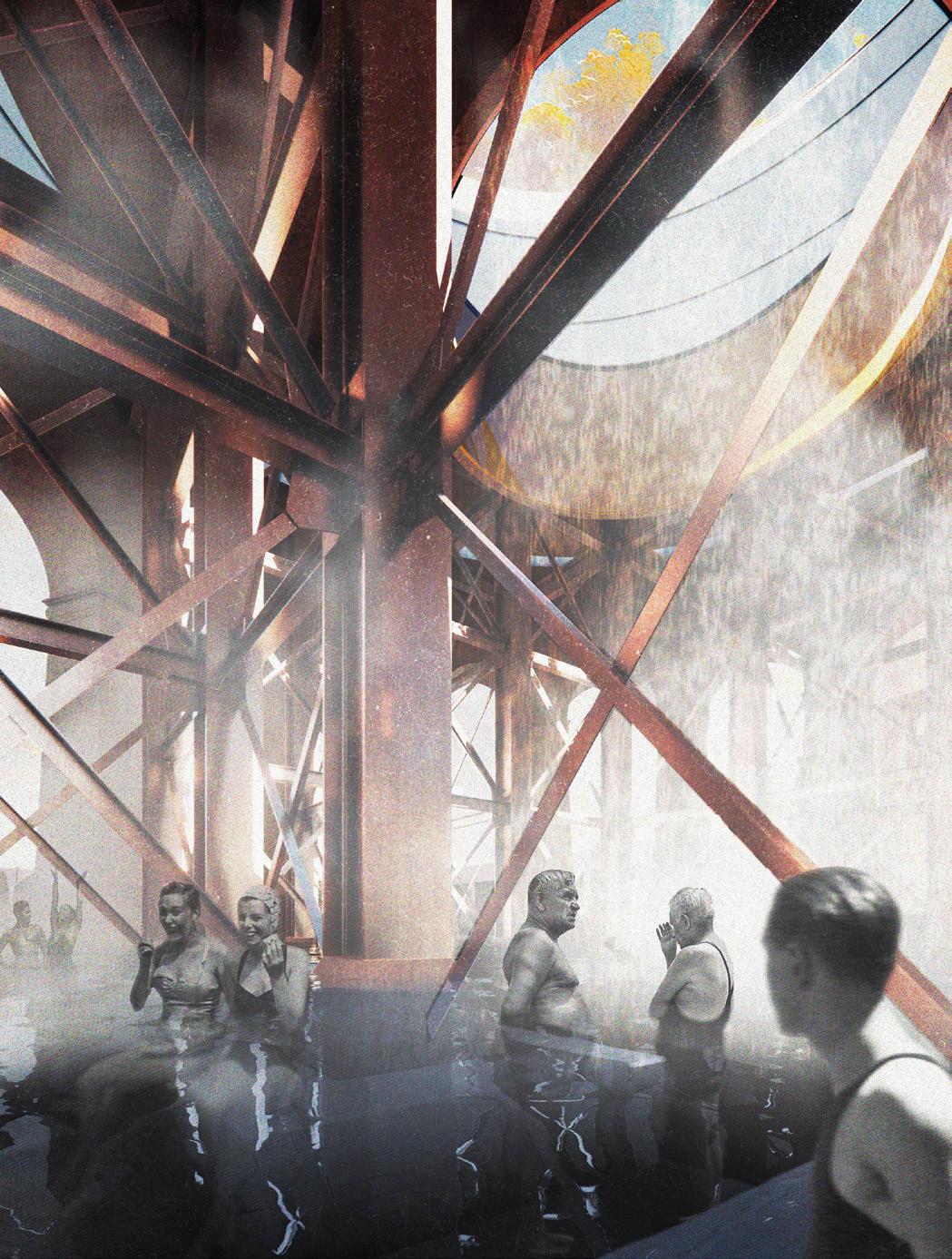

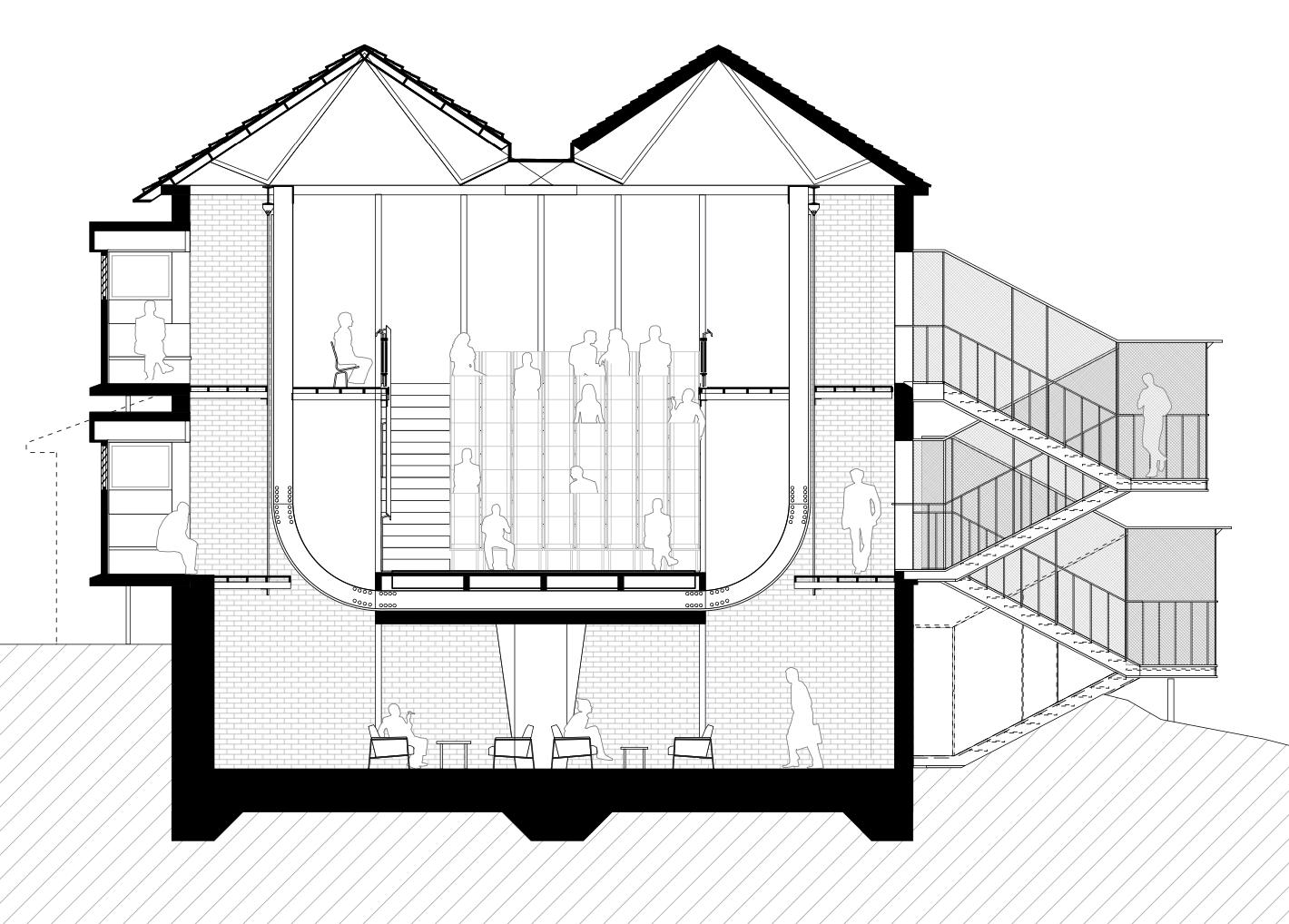

Architecture, Liberation, and the Pursuit of Eros Rohan Gemin

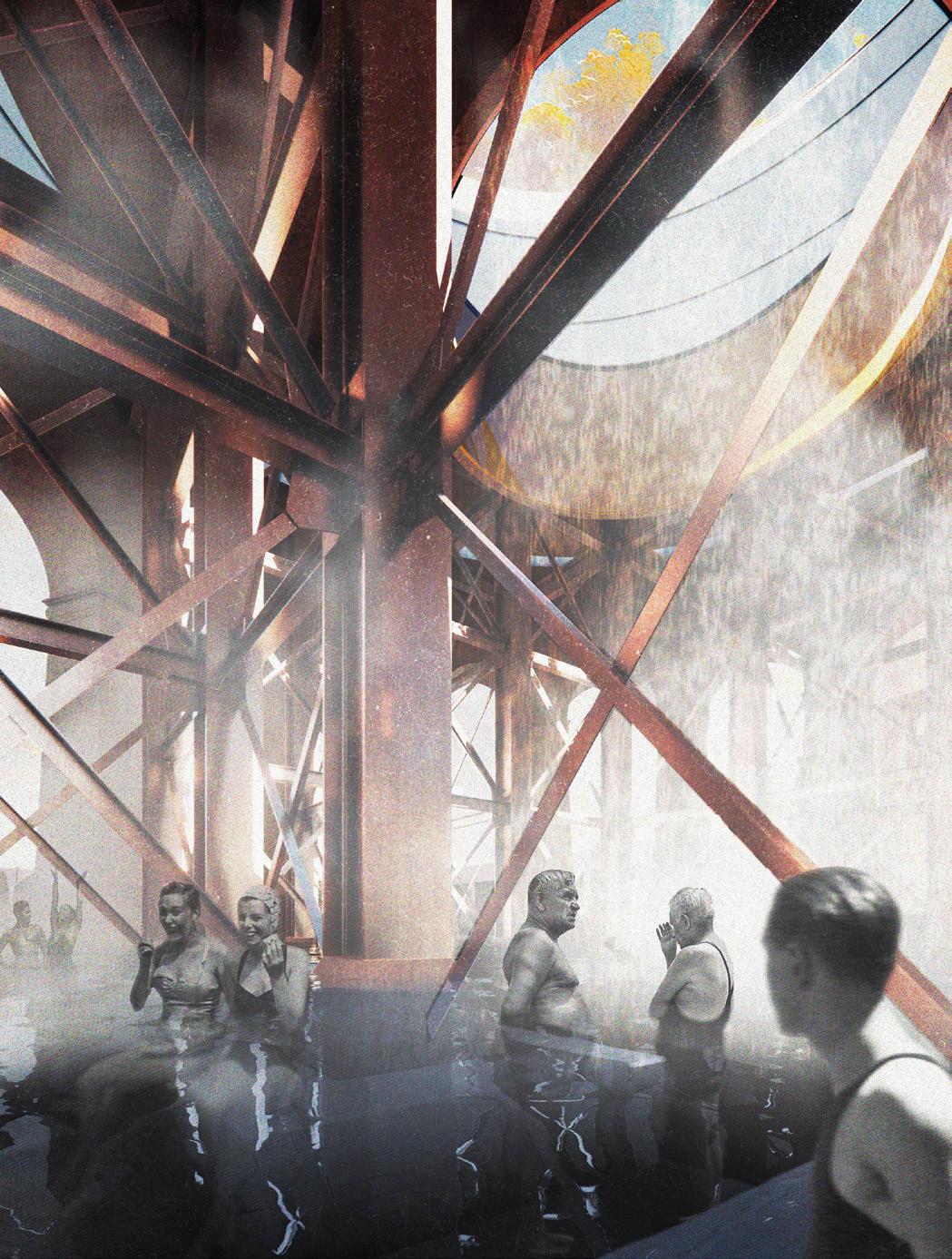

Architecture’s inclusion in the categorisation of fine art remains trivial due to its practical and functional nature. However, its elements of beauty, cultural significance, and ability to impact large masses contribute to a compelling connection to Herbert Marcuse’s argument that art can be used to liberate individuals within systems of repression and shift class consciousness. This project incorporates this theory through a dessert bar and bathhouse to challenge the social and cultural norms perpetuating a culture of shame towards sex and sexuality, affecting those historically oppressed and forced to function in the basements of Oxford Street, Sydney.

MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

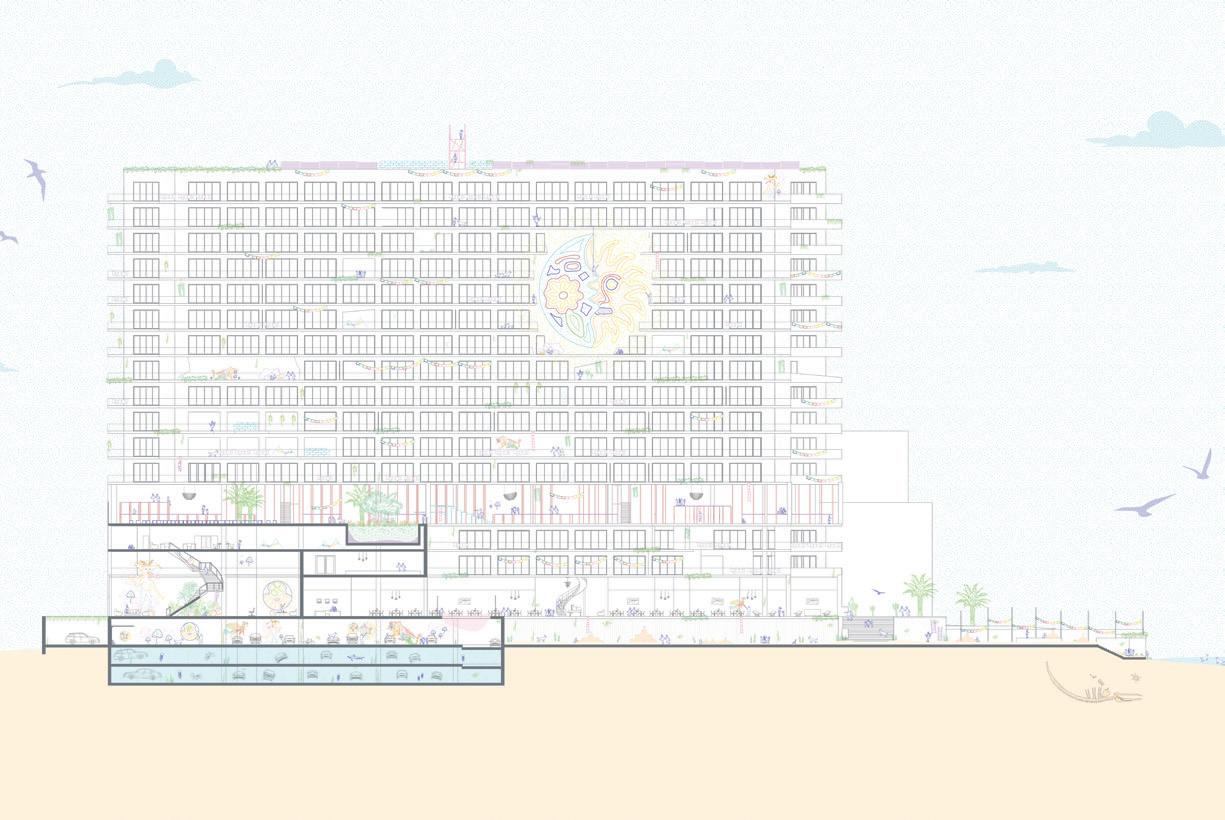

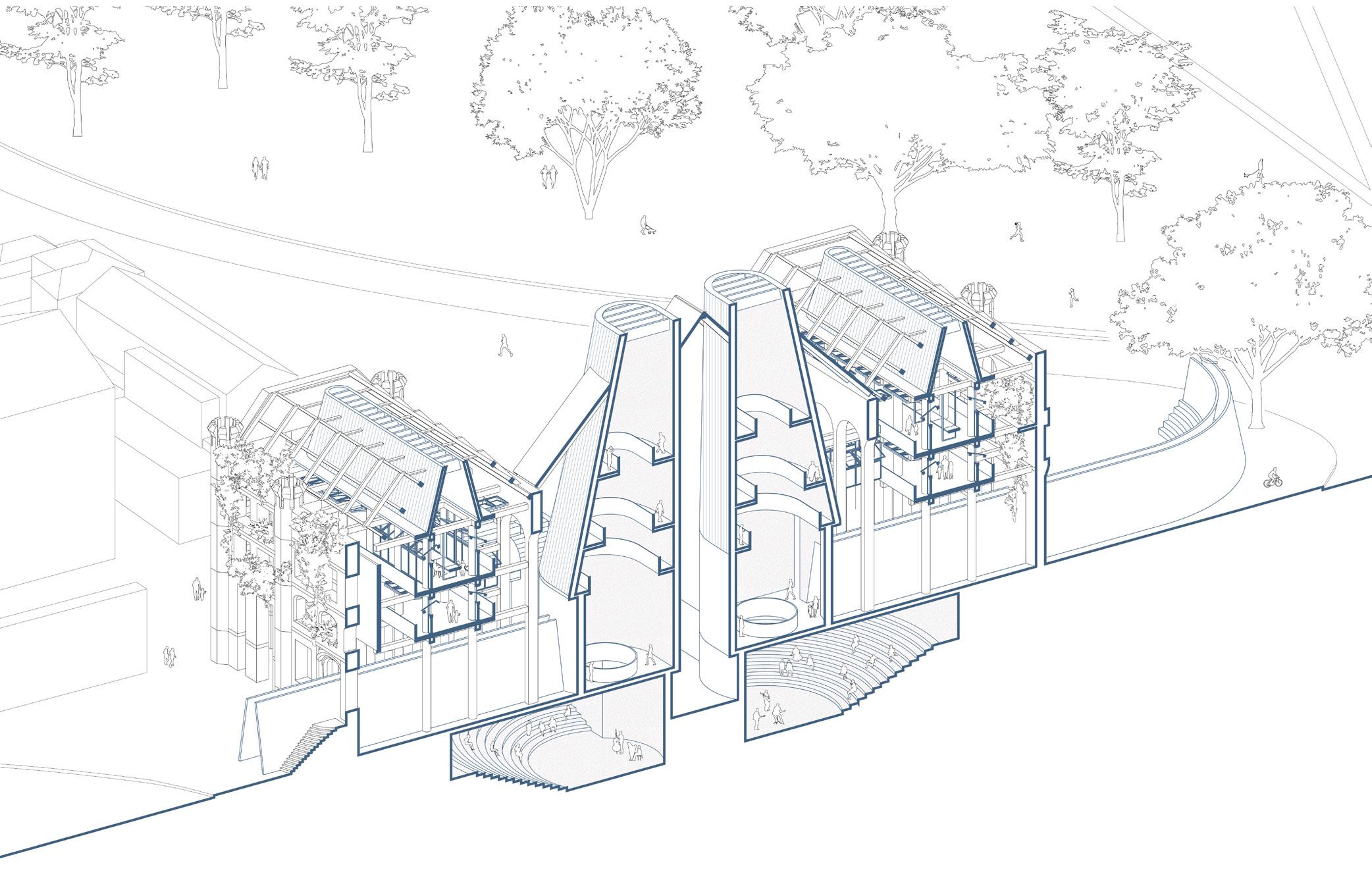

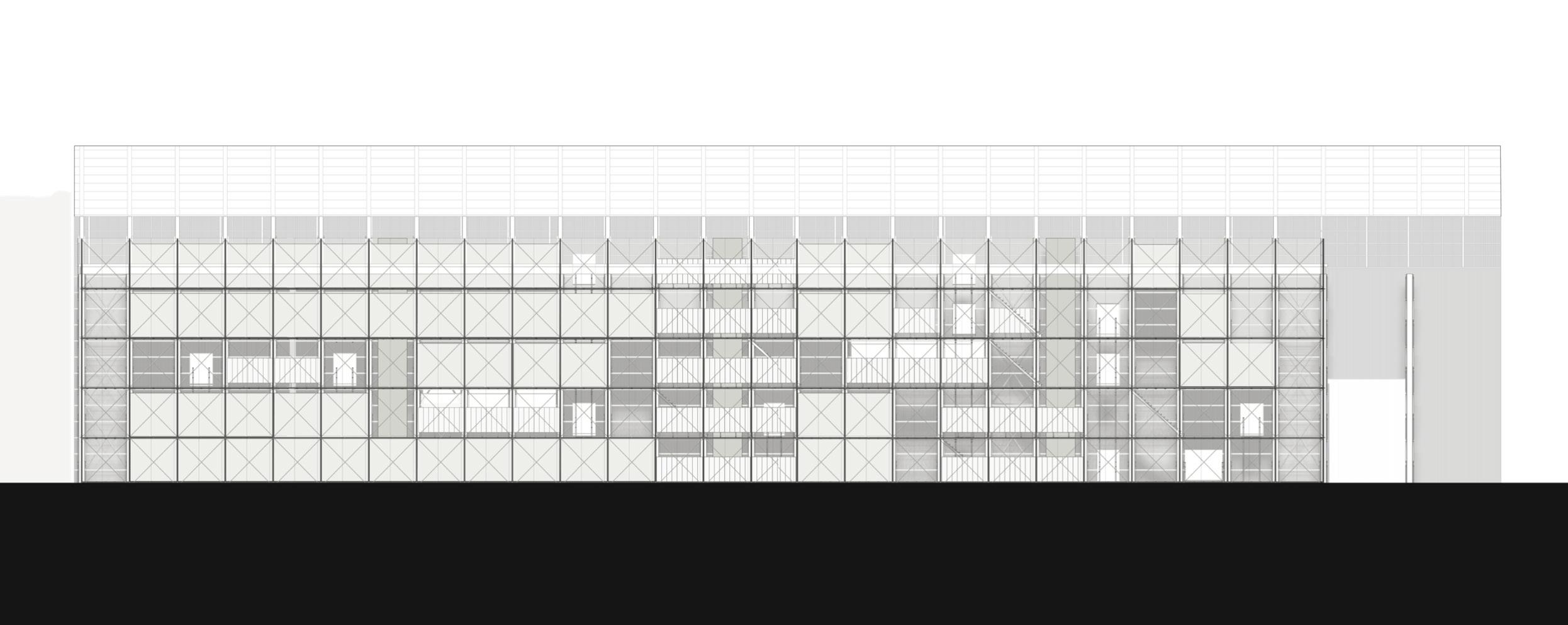

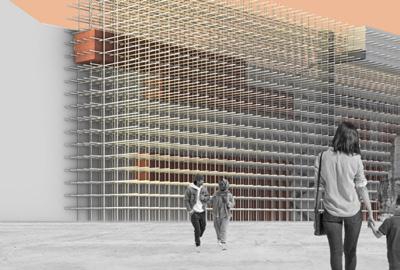

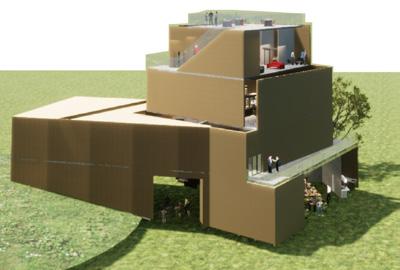

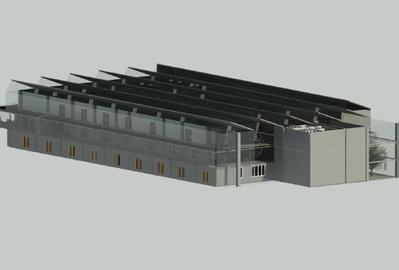

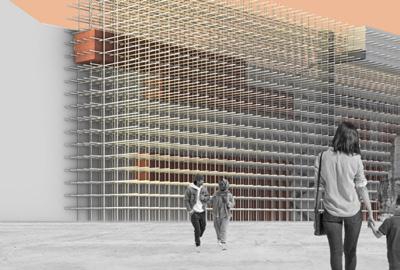

Tower for Artists: Retaining Creative Spaces in the Inner-City Amidst Increasing Gentrification

Nikita Chaudhary

Tower for Artists responds to the exodus of creatives from the inner-city amidst increasing gentrification and urban development. The loss of creative and cultural activity puts our future cities at risk of cultural and class homogeneity. This project investigates how architecture can retain and encourage creative and cultural activity within a gentrified, highdensity, inner-city urban environment. It is sited within the development proposal for Darlinghurst’s new creative precinct, which was criticised for dedicating only 10% of floor space for creative/cultural activities. Tower for Artists is an alternative proposal that revolts against the lack of creative infrastructure while setting a precedent for creative mixed-use buildings.

64

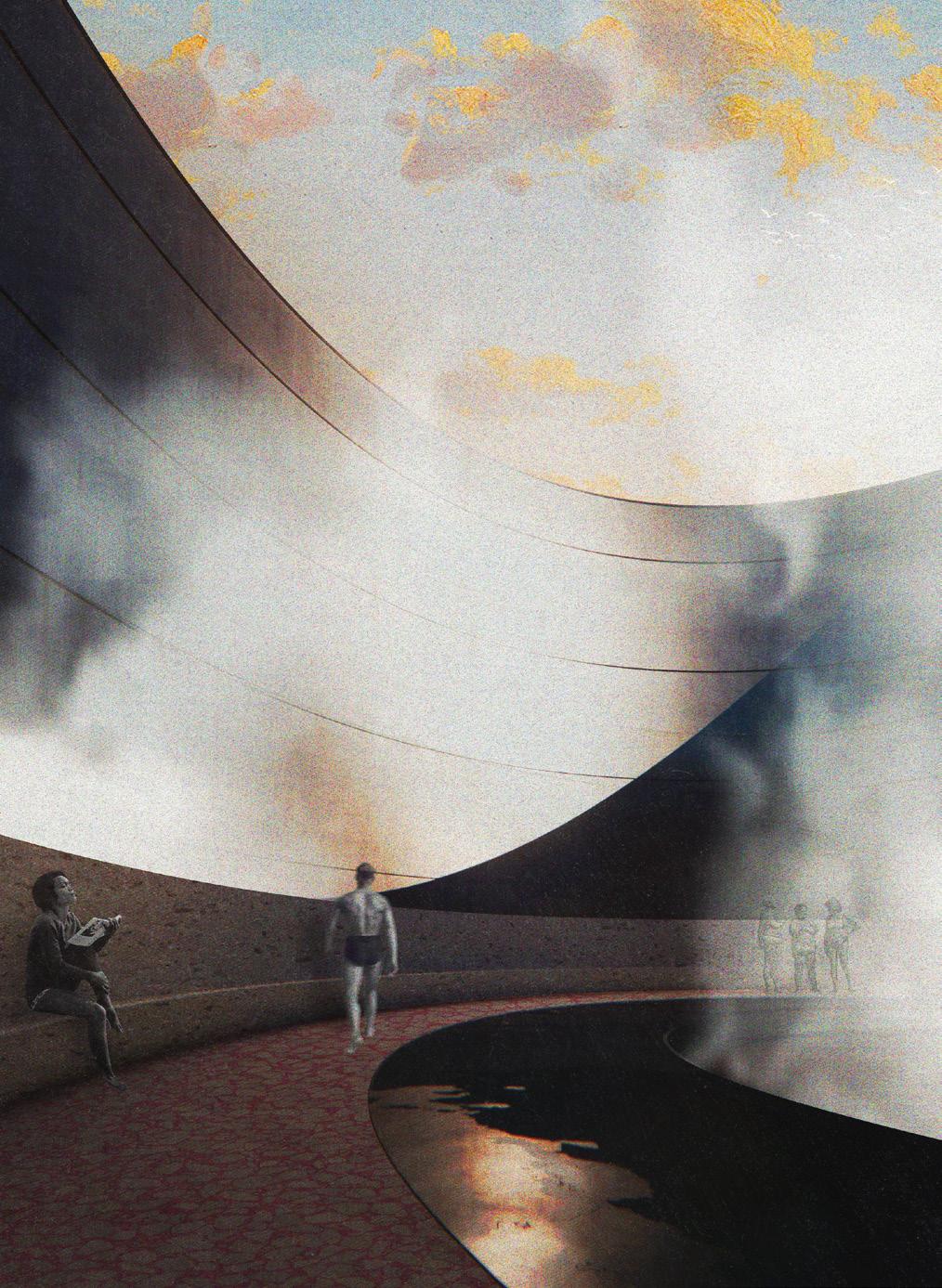

Betwixt and Between Beverley Lim

This project threads together the forgotten landscapes, ruins, thresholds and alleyways on Oxford Street to re-stitch a disparate landscape. The architectural program, a bathhouse, is not restricted to a singular building Rather, the programs that make up a bathhouse have been divided and re-fitted into a series of spaces across the site. To experience the city is to move through it—by separating these functions and shaping a constellation of liminal spaces, the architecture enables individuals to aimlessly wander and traverse the terrain, creating a more playful and activated Oxford Street. Each function of the bathhouse acts as a catalyst to encounter new ways of being in a body, in a crowd, and in a city.

65 MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE

Liminal Nexus

Thesis Studio

Catherine Donnelley

Healing through Architectural Activism + Spaces of Hope

The Uluru Statement from the Heart is a live call to the people of Australia, amplifying the expressed wish of Indigenous Australia for recognition, Voice, Treaty and Truth. Our Prime Minister is determined to honour this call, yet how do architects authentically “walk with” and “listen deeply” to the ancient wisdom of the First and original custodians whose sovereignty has never been ceded.