Translated by Tal Goldfajn

Ruth Rocha

Ana Matsusaki

Translated by Tal Goldfajn

Ruth Rocha

Ana Matsusaki

Translated from the Portuguese by Tal Goldfajn

First English language edition published in 2024 by Tapioca Stories

English language edition © 2024 Tapioca Stories

Originally published as Marcelo, Marmelo, Martelo in 1976 by Editora Abril Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil.

English language translation published by arrangement with Base tres, www.base-tres.com.

English translation © 2024 Tal Goldfajn

Illustrations © 2024 Ana Matsusaki

Text © 1976 Ruth Rocha

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023948716

ISBN: 978-1-7347839-9-5

Printed in China

First Printing, 2024

Obra publicada com apoio da Fundação Biblioteca Nacional/ Ministério da Cultura e do Instituto Guimarães Rosa do Ministério das Relações Exteriores do Brasil.

This publication was made possible with the support of the National Library Foundation/Brazilian Ministry of Culture and the Guimarães Rosa Institute of the Foreign Affairs of Brazil.

Tapioca Stories, a New York–based publishing house with Latin American soul, introduces young English readers to the finest Latin American children’s books, originally written in Spanish and Portuguese.

© 2024 Tapioca Stories

55 Gerard St. #455, Huntington, New York 11743 www.tapiocastories.com

Ruth Rocha

Ana Matsusaki

Ruth Rocha

Ana Matsusaki

Marcelo was always asking questions to everyone around him:

“Papa, why does the rain fall?

Mama, why doesn’t the ocean overflow?

Grandma, why do dogs have four legs?”

Grown-ups would sometimes answer his questions.

But often, they wouldn’t actually know how to answer.

“Oh please, Marcelo, how on earth would I know this?”

There was a time when Marcelo became obsessed with the names of things:

“Mama, why is it that my name is Marcelo?”

“Well, because your father and I chose the name Marcelo for you.”

“And why didn’t you choose Martello?”

“Well, my sweet, martello is not a name for a person. Martello is the name for a small tower.”

“And why didn’t you choose Marshmallow?”

“Because marshmallow is a name for a kind of candy, son!”

“Couldn’t we call the candy marcelo and call me Marshmallow instead?”

Every day he would start all over again:

“Papa, why is a table named table?”

“Well, Marcelo, you see, it comes from the Latin language.”

“Really, Papa, from Latin? Is Latin made of gelatin?”

“Not exactly, Marcelo. Latin is a very old language.”

“And why, in this Latin language, is a table not called a chair, and a chair is not called hair, and hair is not called bear?”

“For heaven’s sake, this boy will drive me crazy!”

A few days later, when Marcelo and his father were playing soccer together, Marcelo said:

“You know, Papa, I think this Latin language, and I suspect not just Latin … gave things the wrong names. For example, why do we call a ball, ball?”

“I don’t know, Marcelo, maybe because a ball reminds us of something round? What do you think?”

“Yes, a ball does remind me of something round, but then a birthday cake also reminds me of something round … but Mama always bakes rectangular cakes for my birthday!”

Marcelo’s father was definitely becoming a bit confused.

“Basically it’s all wrong. A ball is ball because it’s round. And round can become ground. And ground can turn into underground. And Mom says that a rose is a rose is a rose. ”

“I think things should have names that make more sense. Take chair for example. Why chair? It doesn’t mean anything. It should be called seater. And pillow? Why pillow? It should be called a headow, obviously! That’s it, from now on I’m only going to speak in words that I think make sense.”

Early the next morning, Marcelo began speaking his new language:

“Mama, can you please pass me the scrambler?”

“Scrambler? Of course! But what is a scrambler?”

“The little thing you use to scramble the coffee.”

“Oh … you mean the spoon.”

“Papa, can you please pass me the cow juice?”

“The cow juice? Hmm, what’s that?”

“You know what cow juice is. It’s over there, in the cowtainer?”

“You mean the milk in the container?

Honestly, Marcelo, who can understand you?”

Marcelo’s father decided to have a little talk with him:

“Marcelo, listen, all things have a name. And we all have to call these things by the same names because if we don’t, we can’t be sure we will understand each other.”

“I totally disagree, Papa! Why can’t I invent my own names for things?”

“Marcelo, please stop saying these nonsensical and unpleasant words!”

“You see, Papa? You see, you do understand! How did you know I said something unpleasant?”

Marcelo’s father sighed:

“OK, my son, go and play now, I’m very busy …”

Marcelo, however, could not stop puzzling over the names of things.

“Good sunning to you all!”

Marcelo’s mother and father just looked at each other and said nothing.

Marcelo continued to create his own words:

“You know what I just saw? I saw a schlepper schlepping a draggiage. Then the schlepper ran away and the possessor got furious.”

Marcelo’s mother was getting a little bit worried. She spoke with Marcelo’s father:

“João, listen, I’m very worried about Marcelo, this obsession he has with the names of things. What will happen when school begins? It might get complicated …”

“Don’t worry, Laura! It’s just a kid being a kid.”

But his inventions lingered on …

When guests came to visit, it was a bit awkward. Marcelo would greet them by saying:

“Good sunning!” “Good mooning!” That’s how he called morning and night.

Marcelo’s parents would sometimes feel so embarrassed in front of their guests that they wished the ground would swallow them up.

Until one day …

Marcelo’s dog, Godofredo, had a cute little wooden doghouse that Mr. João had made for him.

Marcelo insisted on calling the little house a dogstayer, and the dog Barky.

All of a sudden, Godofredo’s doghouse caught fire from a cigarette carelessly thrown over the fence. It was awful!

Marcelo rushed into the house shouting:

“Papa, Papa, Barky’s dogstayer blastflamed.”

“What are you talking about, Marcelo? I can’t understand you!”

“The dogstayer, Papa, it’s blastflaming!!”

“I don’t know what that means, Marcelo, please speak clearly!”

“It’s all in blastflames, Papa, it’s a total ashroom!”

Mr. João could clearly sense his son’s distress, but could not make any sense of his words …

When Mr. João finally understood what Marcelo was talking about, it was too late.

The doghouse had burned to the ground. It had turned into a pile of ash. And Godofredo was whining softly nearby … Crestfallen, Marcelo said:

“You know, Papa, grown-ups don’t understand anything about anything at all!”

Marcelo’s mother looked at Marcelo’s father.

Marcelo’s father looked at Marcelo’s mother.

Marcelo’s father said:

“Please don’t be sad, my dearest boy. We’ll build a new dogstayer for Barky.”

And Marcelo’s mother said:

“Yes, we will! A beautiful new brown dogstayer, with a little openance in the front and a blue coverer on top …”

Now everyone in that family understands each other very well.

Marcelo’s mother and father didn’t learn to speak exactly like Marcelo, but they do try very hard to understand what he says. And they don’t care anymore what their guests think …

Time passed …

Marcelo’s eldest daughter is now seven years old.

The other day Marcelo was sitting reading a book when his daughter came up to him and asked:

“Papa, why is a table named table?”

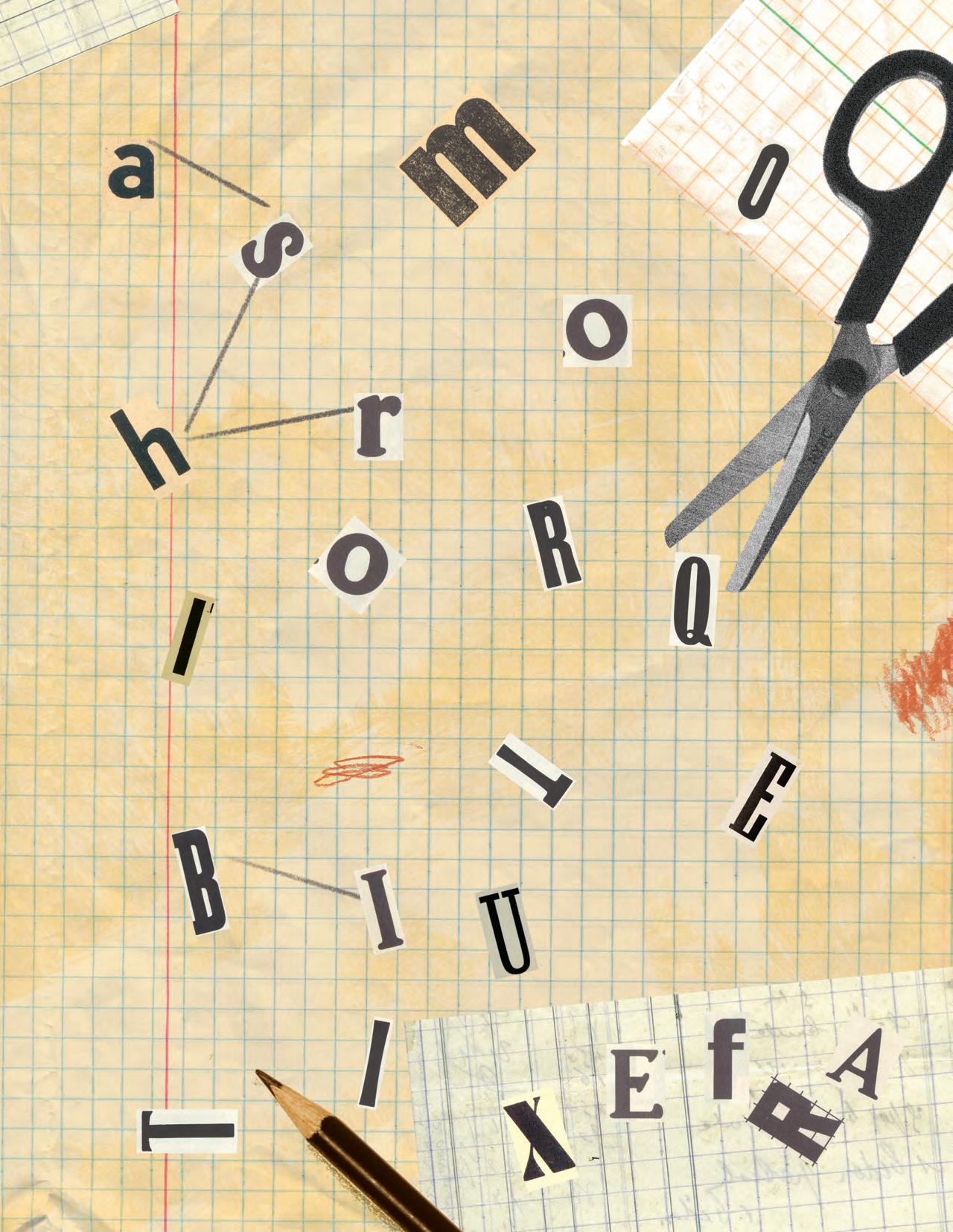

“Ruth Rocha is a magician! Thanks to her ability to find poetry in humor and humor in poetry, she wrote new classics that inspired inquisitive generations. By doing so, her innovative approach resonated around the globe. Her books became a beacon of freedom during the Brazilian dictatorship, a period when the government tried to silence everyone’s voices and thoughts. Marcelo, Martello, Marshmallow freed the minds of an entire generation through the restless, questioning gaze of the boy Marcelo. This is an exquisite book that has now found an impeccable translation by Tal Goldfajn, presented in the always fantastic Tapioca Stories edition! Here, the importance of authorial translation is absolutely evident. Ana Matsusaki’s illustration brings, in its graphic invention, the almost musical aesthetics of Brazil, a country that uses rhythm and of-beat accents, so that the poetic gaze expands and honors the reader and their interpretive freedom. “Dad, why is rhythm called rhythm?” Let’s ask the fabulous Ruth Rocha!”—Roger Mello, Brazilian author, illustrator, and a Hans Christian Andersen Award winner.