Por tico

Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan

Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan

Imagine alternate realities. Decarbonize, de-grow, de-risk. Halt new construction. Replace aluminum with fungal wool. Plan for Michigan boomerangs. Disrupt spatially concentrated homogenous belief systems. Use the university to demonstrate change.

These were among many directives that participants advanced during the symposium with which we launched our Climate Futures platform. Through two days of presentations and debates, linked to an exhibition of faculty work, we discussed a range of approaches through which our abilities in architecture, design, construction, policy, technology, planning, and real estate can help people address and manage climate change.

Our purpose for Climate Futures is to advance our impact in research and education for climate action and environmental justice. We will champion our faculty, students, and partners at U-M and beyond in the important work they do to achieve inclusive, sustainable, and just futures.

My hope is that this initiative equips communities to address climate change so that they can live better in the future. That it strengthens discovery and education here at Taubman College, so that faculty and students lead their fields today and tomorrow. And that it integrates architecture and planning more fully into climate work, so that more partners understand our capacities and seek our help to achieve their goals.

Jonathan Massey, Dean Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning University of Michigan

Professor Larissa Larsen works to protect vulnerable populations against the consequences of dangerous indoor temperatures

With Post Rock, a Taubman College research team led by Associate Professor Meredith Miller is developing an innovative cladding made from automotive plastic scraps 20 Work Spotlight

Network Duality, from Xiaofan Liang, assistant professor of urban and regional planning

Student-led

Student Research Grant program prepares graduates for successful careers

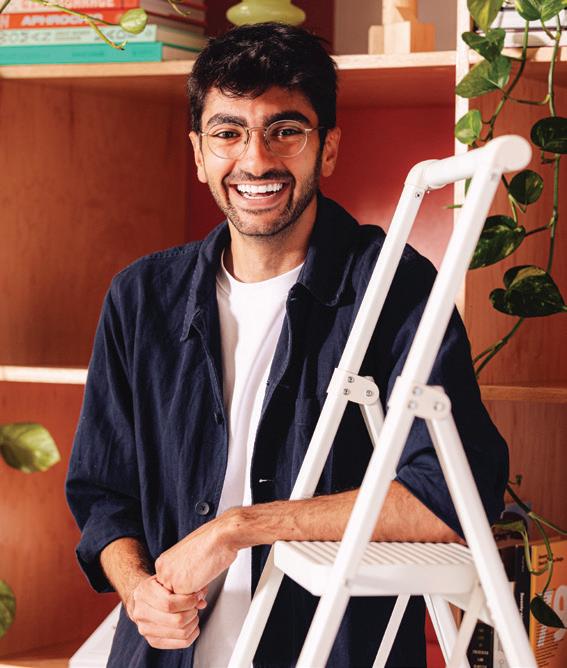

Michael Pukszta, B.S. ’87, M.Arch ’89, Global Healthcare Practice Co-Director at Cannon Design, and Roy Khoury, M.Arch ’25, discuss architecture generalists vs. specialists, giving back, and sustainability

Student study trips to France and India in 2024 highlight Taubman College’s unique experiential learning opportunities

The late Robert Metcalf, B. Arch ’50, continues uplifting Taubman College students through his transformational gifts

What Are You Thinking About?

Jenna Jarjoura, B.S. Arch ’25; Joshua Nicholson, B.S. UTech ’26; Farah Ossaimee, M.Arch ’25

35 The Donor Connection

Individual and corporate contributions support Taubman College’s research enterprise 36 Meaningful Giving

Alan Berkshire, B.S. Arch ’82, and Cynthia Reavis Berkshire, A.B. ’83, are major supporters of Taubman College students and faculty research

42 Fulfilling Lifelong Dreams

Through Taubman College, Damon Healey, M.U.P. ’10, achieved his goals of earning a graduate degree from the University of Michigan and founding his own real estate firm

38 Urban pioneer’ dedicated to community — and U-M

Windom Kimsey, B.S. Arch ’83, M.Arch ’85, funds new architecture course focused on design and sustainability

44 Thanks for the Memories

Alumni share their thoughts and photos during Homecoming ’24

40 Big Resurgence in the Big Apple

Regina Myer, A.B. ’82, M.U.P. ’84, leads sustainable regrowth in Brooklyn using skills honed at U-M

Studio Reassembled is a pilot, 1500-square-foot studio environment on the third floor of Taubman College. Hosting nine studios at the undergraduate and graduate levels in architecture and urban design, this educational model pivots from the traditional one-to-one student-to-desk setup, offering amenities and resources in alignment with new pedagogical trends that would otherwise be out of reach for individual students. “This initiative represents a fresh, unprecedented approach in academia, one where the community is actively involved in shaping the very space they occupy,” says Anya Sirota, associate dean for academic initiatives. The prototype will continue to evolve and will be featured in a future issue of Portico

Lan Deng published a commentary essay in the Journal of the American Planning Association as part of the collection to mark the 75th anniversary of the landmark Housing Act of 1949. Her essay is titled “America’s Housing Affordability Crisis: Time for a New Housing Act?” “What is needed,” Deng writes, “is a comprehensive housing act that would significantly increase direct housing assistance through programs like universal housing choice vouchers while promoting the production and preservation of affordable housing.”

What if, instead of building our aging highways wider and higher, we removed those highways altogether? Journalist Megan Kimble addressed this question during a fall 2024 book talk at Taubman College. Kimble is the author of City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality, and the Future of America’s Highways.

For more: studio-reassembled.com

The 37th volume of Dimensions, Taubman College’s annual student-produced journal of architecture, was one of three publications to win the 2024 Douglas Haskell Award for Student Journals from the Center for Architecture and AIA New York. The Haskell Award was founded to encourage student journalism on architecture, planning, and related subjects and to foster regard for intelligent criticism among future professionals. The award is named for architectural journalist and editor Douglas Haskell, editor of Architectural Forum from 1949 to 1964. Published annually since 1987, Dimensions seeks to contribute to the critical discourse of architectural education by documenting the most compelling work produced by its students, faculty, fellows, and visiting lecturers. The student work in Dimensions 37 reflects a focus on land politics and imagining the future; neon colors and innovative digital representation styles abound.

“

[Solarpunk] is viewing design not so much as being responsible for novel or innovative techniques or forms, but really about taking existing knowledge, distributing that knowledge, and encouraging broader participation in how we live our everyday lives.”

— Matthew Wizinksy, associate professor of practice in urban technology, in ABC Australia, “Solarpunk: How to Design a Utopian Future”

Sharon Haar has been appointed the Emil Lorch Collegiate Professor of Architecture and Urban Planning from September 1, 2024, to August 31, 2027. Haar came to Taubman College to serve as the architecture program chair, a position she held from 2014 to 2019. An expert on urban university campus design, Haar’s research spans topics that include the history of architectural practices devoted to social activism, equitable housing, and urban design. Her continuing research and advocacy regarding affordable housing have been pivotal in creating the Center for Equitable Housing at Taubman College, which she co-founded in 2020. Haar’s contributions to architectural education on a national level include serving as a member of the Board of the Architects Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the American Institute of Architects, and as president of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture in 2022-23.

Two Taubman College faculty members are designing an outdoor alcove featuring a light-inhabiting glass installation at the University of Michigan Nichols Arboretum that will provide space to promote healing for those who are grieving. Professor of Architecture Catie Newell and Professor of Practice in Architecture Upali Nanda are the principal investigators of Inhabiting Light, along with Bowling Green State University’s Alli Hoag. They received support

from the Arts Research: Incubation & Acceleration grant program, a collaboration between the U-M Office of the Vice President for Research and the U-M Arts Initiative. The installation will be in the arboretum’s Magnolia Glade, a site dedicated to the A Walk to Remember and Tree Planting Memorial. Each year, the C.S. Mott Foundation plants a tree at Magnolia Glade to honor and remember prenatal loss.

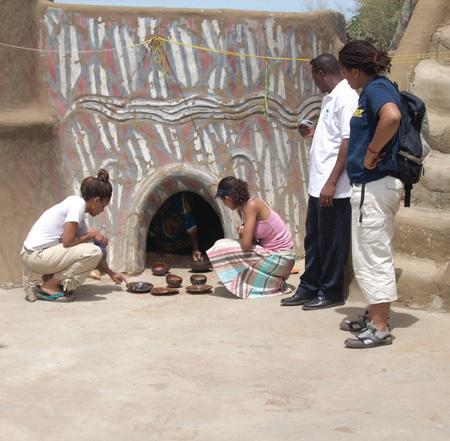

What can U.S. food systems planners and scholars — and specifically those who focus on urban agriculture (UA) — learn from the Global South? Drawing from peer-reviewed and grey literature, including case studies collected by the Milan Urban Policy Pact and Resource Centres on Urban Agriculture and Food Security, this chapter argues that UA in the Global South takes on a much more urgent role as a life-sustaining mechanism in cities facing extreme challenges typically not experienced in the Global North.”

— Lesli Hoey, associate professor and director of doctoral studies in urban and regional planning, in Planning for Equitable Urban Agriculture in the United States (Springer, 2024)

Abraham Alzoubi, M.Arch ’25, was awarded a summer research grant by the U-M National Center for Institutional Diversity (NCID) to investigate the various land uses in Detroit and Palestine. It was one of 19 grants given to graduate students and teams at the University of Michigan through the provost-funded Anti-Racism Collaborative. Alzoubi plans to use the grant to fund field expeditions to Detroit and Palestine and learn more about the ongoing efforts of activists to fight against land commodification, which is the process by which land is bought and sold as an economic resource. “In the society we live in now, our view on land is that it must be cultivated and improved through extracting resources,” Alzoubi said. “I’m wondering how we can have a non-extractive relationship with land, where we’re not destroying it for cultivation or improving it.”

Nearly 25 Taubman College students and more than a dozen Alumni Council members participated in the college’s sixth annual speed networking event on September 13. The event allows students to practice their elevator pitch and interview skills and connect with college alumni.

Faculty members Anya Sirota and Craig Wilkins won highly selective Graham Foundation grants for their work to expand contemporary ideas of architecture through rigorous interdisciplinary work. Sirota and Suzanne Lettieri won for a book they are co-editing, Junior Architects (Park Books, 2024), which explores the evolving landscape of architectural and design education, propelled by student-led movements advocating for an emancipatory education in the face of broader socio-political divisions around race and class. Wilkins won for an exhibit called if history were told as stories it’d never be forgotten … The exhibit, slated for display at the Detroit Historical Museum in February 2025, will tell the story of the Smithsonian National African American Museum of History and Culture. Despite the plethora of press and publications on the museum, the story of its improbable journey has largely remained untold in its proper context, one that centers on the unique relationship of African Americans to the National Mall and the Mall’s singular importance in the construction, celebration, and aims of national identity.

Taubman College students were lauded for their community involvement, passion for architecture, leadership skills, and academic excellence in winning seven of the 12 scholarships awarded by the Michigan Architectural Foundation (MAF) in 2024. MAF awards merit-based scholarships annually to students completing a bachelor’s degree program and who have been accepted or are enrolled in an academic program leading to a master of architecture degree. This year, the foundation awarded $44,000 in scholarships, with the number of scholarship applications more than doubling from 2023, with 51 applications. Winning students from Taubman were Malak Atwi, B.S. Arch ’25, Jacob Brookhouse, M.Arch ’26, Aaron Comstock, M.Arch ’25, Zariah Hernandez, M.Arch ’25, Cory Hoffman, M.Arch ’26, Riley Montgomery, M.Arch ’26, and Ashlynn Tower, B.S. Arch ’25.

Martin Murray, professor of urban and regional planning, was awarded the 2024 U-M Press Book Award for The Infrastructures of Security: Technologies of Risk Management in Johannesburg (University of Michigan Press, 2022). The book explores the South African government’s shift from human-based private policing to an increasing reliance on technology to respond to crime, particularly in Johannesburg. This includes the widespread use of video cameras, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and automated systems, effectively replacing human watchers with machine watchers. The aggregate effect of such steps is to determine who is, and isn’t, allowed to be in public spaces — essentially another way to continue segregation, the book argues.

The University of Michigan has awarded Bold Challenges interdisciplinary research grants to two Taubman College-led projects — one that would create wearables to help overcome challenging situations for neurodiverse people and another that imagines 3D-printed ceramic building facades to mitigate flooding. Sean Ahlquist, associate professor of architecture, is leading the wearables project with faculty from across the university that will design sensor-laden and sensory-responsive knitted wearables that can gather real-time information about the surrounding environment and deliver feedback. This helps caregivers and neurodiverse people better identify the nature of overwhelming situations and preferred activities, allowing them to respond and adapt accordingly. The project is called Empathetic Multi-modal Behavioral Response and Adaptive Care Environments (EMBRACE).

Tsz Yan Ng, associate professor of architecture, is leading a project called Hygroscopic Envelope: Building Enclosures for Climate Adaptation, in collaboration with Wes McGee, associate professor of architecture, and researchers from U-M engineering and Tulane University. The project aims to mitigate flooding in the context of a changing climate by exploring the use of 3D-printed ceramic building facades to collect, retain, and release stormwater.

German-born Antje Steinmuller

has studied around the world, bringing a fresh outlook to her role as architecture chair

Antje Steinmuller, the new chair of Taubman College’s architecture program, has studied, taught, and worked around the globe. Along the way, she learned to appreciate — and leverage — a fresh viewpoint.

Steinmuller earned college degrees in Stuttgart and Berlin and a Master of Architecture at the University of California, Berkeley. The German native completed a study exchange in Paris and an international summer workshop in Venice. She spent two decades as a practicing architect, faculty member, and college administrator in the San Francisco area, leading numerous travel studios to Asia and Europe.

“I really came to understand the perspective of someone who is not of the place,” she says. “Getting to be in a different cultural or social context with a purpose — be it a job or an exchange — is an incredible opportunity. To have the perspective of the outsider, of not being weighed down by habit or that sort of automatic acceptance — thinking that ‘We’ve always been in it, so that’s all we know.’ I feel very fortunate to have been able to make my professional life with a bit of that outsider’s perspective.”

Steinmuller began a three-year appointment as architecture chair on July 15 and joined the Taubman College faculty as a professor of architecture. One of her short-term goals is to identify and promote the strengths of faculty research and teaching and then examine how the architecture program can further address ever-evolving environmental, social, and technological issues. She sees this as a year long planning process that’s completed in close collaboration with faculty and students.

“Our architecture program has such a diversity of research expertise, like digital technologies, social justice in design, and architecture history and theory,” she says. “These are very different strengths and I think this has led to a perception that we do a lot of things and that the breadth is the value. This is true, but can we identify six or seven things we do really well, like ‘buckets of expertise,’

that we put forward as topics we collectively care about and stand for? This way, we’re strengthening the relationship between research and education and visibility.”

Steinmuller says she’ll develop longer-term plans in collaboration with college leaders and architecture faculty and students. She hopes to focus those plans on what architects can contribute to the climate crisis and how the Great Lakes region is often looked at as a climate refuge.

“I think there is a very specific education that Taubman College can offer based on its location. There should be a reason people want to come here, to study a climateforward version of architecture education. I also think Detroit holds many lessons with regard to economic challenges, racial justice, water issues, and pollution issues from industry. There is so much to be learned here that should attract anybody who wants to study architecture or planning with a more urban lens.”

Previously, Steinmuller was an associate professor at California College of the Arts (CCA) in San Francisco, where she chaired the Bachelor of Architecture program and co-directed the Urban Works Agency, CCA’s urbanism research lab. Her research explores the role of design at the intersection of citizen-led and city-regulated processes in the production of urban space — from new forms of collective living to the agency of architecture in the housing crisis. She holds a Diplom-Ingenieur in Interior Architecture and Furniture Design (Hochschule für Technik Stuttgart), a Vordiplom in Architecture (Technische Universität Berlin), and a Master of Architecture (UCBerkeley). She is co-founder of ideal X, a design consultancy focused on the collective potentials of urban spaces in transition, and previously was a principal at Studio URBIS in Berkeley.

Steinmuller says part of what drew her to Taubman College and U-M was the vast research opportunities and the diversity of students, staff, and faculty.

“I really value the learning at a large research institution on one hand and also think I can bring other experiences and perspectives to this role,” she says. “I love working at U-M with so many people from different countries and backgrounds. That sort of coming together of different perspectives is incredibly rewarding.”

THE FUTURE IS NOW

Taubman College launches timely Climate Futures platform with architecture Professor Jen Maigret at the helm

IN MANY WAYS, THE SEEDS of Taubman College’s new Climate Futures platform were sown about five years ago when the University of Michigan established the President’s Commission on Carbon Neutrality just as new threads of sustainability research were taking root in the college.

Architecture Professor Jen Maigret, M.S. ’96, M.Arch ’04, would co-lead the commission’s interdisciplinary task

force on building standards, along with fellow Taubman College faculty member Lars Junghans. The commission would produce tangible steps to reduce carbon emissions in new campus construction and major renovations.

Maigret’s training and experience in biology and sustainable design inform her approach to architecture as a component of broader environmental systems. A built environment relies heavily on building performance, she notes, yet other environmental, cultural, and social justice factors must also be considered, including water preservation, food systems, and equitable housing.

It’s this integrated, interdisciplinary approach to architecture and urban planning that will help define the Climate Futures platform. Maigret will serve a three-year appointment as faculty director of the platform, which is supported by Taubman College and the Office of the Provost. The timely launch of Climate Futures coincides with U-M’s Vision 2034 and the continued growth of climatefocused work in the college.

“The timing is perfect for Climate Futures,” Maigret says. “The platform will elevate our growing impact in discovery and education for climate action, sustainability, and environmental justice. By supporting students, faculty, staff, and partners in research and creative practice, teaching, outreach, and engagement, we aim to partner across and beyond the university to achieve inclusive, vibrant, and just futures."

Dean Jonathan Massey says Maigret brings scholarly expertise, insights from teaching key sustainability courses at Taubman College, and experience as a practicing architect. “All of this gives Jen a broad and grounded understanding of how the many people and projects in our college contribute to climate-related work,” he says.

In addition to her work on the President’s Commission, Maigret touts deep experience as an award-winning architect and sustainable design researcher. She serves as a faculty affiliate at the U-M Graham Sustainability Institute

and director of the Dow Sustainability Fellows Program, which allows architecture students to tackle environmental issues with students from other disciplines.

“One exciting aspect of Climate Futures is that we can grow interdisciplinary faculty and student work across the university, and I’ve seen how profoundly impactful this can be from a student perspective with the Dow program,” she says. “The students gain so much when they’re working with other students in different disciplines. All of a sudden they’re bringing different expertise together, different processes together, and the solutions they offer are really exciting because of it.”

Joining Maigret on the Climate Futures team is Sophie Gabrysiak, an environmental biologist who previously worked in outreach and community engagement for U-M’s Life Sciences Institute. Gabrysiak will serve as associate manager, a newly created staff position, to handle the day-to-day logistics of the platform. “I’ll be working with students, faculty, and staff across campus and beyond to identify who is engaged in climate work and facilitate connections that enhance the efforts and successes already underway. I aim to bring more voices and perspectives in conversation to address the many critical facets of climate futures,” she says.

Maigret says the first year of the platform will involve taking stock of the climate-focused efforts throughout Taubman College and bringing awareness to that work. Taubman is distinctive, she says, for its wide-ranging expertise across its architecture, urban and regional planning, and urban technology programs.

“Taubman is a very dynamic unit and changes are always underway from a research and teaching perspective,” she

“

The timing is perfect for Climate

The platform will elevate our growing impact in discovery and education for climate action, sustainability, and environmental justice.”

says. “Through Climate Futures, we’ll be hosting conversations across the different groups at the college to allow us to see what everybody has been working on that may not be completely visible to one another. We are starting within our own community to underscore the strengths that exist, identify any gaps, and determine how the platform can help promote and accelerate all the things we as a college are capable of doing.”

Antje Steinmuller, chair of the Taubman College architecture program, said the many consequences of climate change — ranging from climate migration to issues with material availability – have “so much impact on everything we do as architects and planners.”

“The launch of the Climate Futures platform will lend increasing importance to the question of climate as it relates to everything we do within the college,” Steinmuller says. “Like when we talk about material technologies or AI, we should also be thinking about climate. When we talk about housing, we should think about health and climate at the same time. When we talk about formmaking in early design studios, we should also think about climate in some way.”

In the second and third years of the platform, the Climate Futures team will work to expand existing partnerships and build new alliances with organizations across U-M and outside the university, including design and planning firms, municipalities, and nonprofits in Michigan and beyond. Maigret says many Taubman College faculty members are working with local and international partners on climate-focused projects, so in those cases, it’s just a question of supporting and promoting their work.

As an architect, Maigret has worked on regional projects that intersected environmental and cultural concerns, such as stormwater design in Detroit. She sees Climate Futures expanding on larger-scale sustainability work and furthering the efforts to improve building performance by the President’s Commission on Carbon Neutrality.

“There was a lot of work that we couldn’t capture within the President’s Commission that is now starting to gain attention and investment at U-M that the Climate Futures platform can connect with,” she says. “So in some ways, it is a continuation of my involvement in those early efforts and how they’re growing and in new efforts at the university.”

The platform could also lead to completely new ways of creating, designing, and planning. “Some of the innovation may happen by asking questions about expectations of our built environment. How should buildings, cities, and regions interact from a systems perspective?”

Maigret says. “And some innovation will happen physically through the invention of new materials, workflows, and processes to construct the built environment. And through innovations in policies, community participation, and infrastructure.”

Ultimately, there is a lot at stake in addressing climate issues within the built environment.

“I strongly believe that the quality of the built environment has the capacity to foster collectivity, health, and wellness,” Maigret says. “In my view, our future success in tackling climate challenges is intimately related to how architecture and urban planning can foster social justice and environmental justice to work toward everyone having access to high-quality built environments.”

Some of the nation’s top architects, urban planners, and sustainability experts gathered at the Taubman College Commons from October 17-18 to address the dramatic effects of climate change on the built environment — and to explore novel responses to the global crisis

The Climate Futures symposium, part of the college’s new Climate Futures platform, explored climate migration, climate-resilient communities and universities, environmental justice, climate-conscious construction, degrowth, and more. More than 40 speakers participated in the twoday symposium in person or virtually.

The discussions, noted Taubman College’s Anya Sirota, were both “unsettling and inspiring.”

“We are living in what some have come to call the age of ‘apocalyptic optimism’ — a time when the climate crisis is not just an abstraction but an undeniable force,” said Sirota, associate dean of academic initiatives and associate professor of architecture. “Yet we continue to gather, to discuss, as if there is still room, even an imperative, for optimism. Perhaps this reflects our profession’s need to believe in the power of design, the power of the built environment to right some of these wrongs. In tandem, of course, it gets more difficult to deceive ourselves: sea levels are rising, storms are intensifying, and people — communities — are being pushed from their homes, either by the water itself or by the slow degradation of the economies and ecologies that once sustained them.”

The symposium was held along with the Climate Futures faculty exhibition. The exhibition, curated and designed by former Taubman College Architecture Fellow Strat Coffman at the Liberty Research Annex, features a range of works that engage climate change and sustainability: from rethinking material practices, to overlooked ways of living, to new narratives for climate action.

The increasing frequency of heat waves, cyclones, wildfires, and other extreme weather events have fueled climate migration, as people relocate to areas they consider “climate havens.” Michigan is one such place. However, Jesse Keenan, associate professor of sustainable real estate and urban planning at Tulane University, said during the symposium that climate change touches every corner

of the globe. “Warning: Nowhere is safe from climate change,” Keenan said. “Climate havens are a fiction.”

Mél Hogan, associate professor at Queen’s University, discussed a purely human-made danger to the environment: the huge data centers used to power AI. “AI and their massive data centers are consuming resources, polluting environments, and contributing to climate change at an alarming rate on an already mangled planet.”

Robert Goodspeed, chair and associate professor of urban and regional planning at Taubman College, said population growth and economic vitality in Michigan depends on an urban resurgence. That should be fueled by smart growth policies to create thriving, climateresilient communities that attract young talent. “Urban stagnation and decline may continue, even if there is growth, in the absence of the adoption of smart growth policies to curb urban sprawl and encourage infill.”

How are cities and community groups doing their part?

Toronto declared a climate emergency in 2019 and has adopted a strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2040. One program tracks and captures heat wasted from large buildings through sources such as sewage pipes. One Toronto hospital will reduce its emissions by 85 percent just by tapping into a sewer trunkline and reusing that waste heat, said Duncan MacLellan, project manager for the city of Toronto.

In Detroit, the nonprofit Detroit Future City helped the East Poletown neighborhood buy 12 vacant lots and create Circle Forest, a model for neighborhood improvement and resilience. The area includes 500 new trees, wildflowers, a butterfly garden, and an outdoor movie theater. “It’s the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen,” said Anika Goss, president and CEO of Detroit Future City. “People can’t believe that this is happening in Detroit.”

Jen Maigret, Taubman College professor of architecture and faculty director of the Climate Futures platform, said the symposium brought together participants “who share both passion and a feeling of urgency for the emerging range of climate challenges that are rapidly and dynamically impacting the world we all share. My greatest hope for this symposium is that it will model the power of collectivity, and by extension, demonstrate the potential for a Climate Futures platform to help us organize ourselves, our ideas, our passions, and our imaginations around a multitude of futures help generate just relationships with one another and with the earth.”

LARISSA LARSEN’S GRANDMOTHER lived in an apartment building with no air conditioning. She wouldn’t cook hot dinners at certain times and closed the drapes to try and keep out the heat. Reflecting on that experience, Larsen says many older people live in substandard homes, particularly in Rust Belt cities, where they can’t afford air conditioning. “The impacts are really going to be significant as we have more extreme heat,” she says.

The potentially deadly consequences of extreme heat on vulnerable populations is prompting Larsen, a professor

of urban and regional planning at Taubman College, to research and advocate for solutions.

In a 2022 study, Larsen interviewed 50 mostly low-income families in Detroit and found that only 35 percent had working air conditioning and could afford to use it. By contrast, that number was much higher in Atlanta (57 percent) and Phoenix (95 percent). “It was a really striking statistic,” she says. Larsen initially focused her research on outdoor temperatures and hadn’t considered indoor temperatures and the factors influencing them.

“This is the first time I measured temperatures indoors and realized there’s a whole world of issues that we’re not looking at yet very carefully.”

In 2023, about 2,300 people died from exposure to extreme heat in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and this number is expected to increase as heat waves become more pervasive. Larsen says the focus needs to shift from ensuring that people don’t get too cold in the winter to better understanding the scope of those who are suffering from extreme heat.

To get a better handle on the situation, she is trying to convince government officials to include a question on the U.S. Census American Community Survey asking people if they have working air conditioning and if they can afford to run it. She met with officials from the Department of Health and Human Services in April and again in September to advocate for the change. Having that information, she notes, “will enable anybody who can access Census data to better understand who’s at risk.”

When a flood, hurricane, or tornado hits, it’s easy to see the damage. But heat is invisible, Larsen explains, and so having data on air conditioning will help elevate its importance. In particular, it could provide crucial information on which parts of a city have vulnerable individuals and low prevalence of air conditioning. That way, during an extreme heat wave, city officials could deploy people door to door to conduct wellness checks and transport residents to cooling centers by bus if necessary. “It would help people target who is likely to die,” she says. In the long term, it would help cities decide where to prioritize home weatherization improvements.

One of Larsen’s studies indicates that a significant amount of weatherization is needed in Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Milwaukee. Many people have an old home that is not protecting them from the elements, she says. The study recommends money be spent through the federal Weatherization Assistance Program to make the homes more energy efficient to better protect residents from unsafe indoor temperatures. And because many people get deferred from the weatherization program because their roofs need fixing, she also advocates for reducing the program’s criteria for housing quality. “I look back to what happened in Chicago in 1995 when 739 people died as a result of elevated temperatures, with a majority in their homes,” she says. “I think we could see repeat happenings of this type, which is really frightening.”

“

We used to think of air conditioning as a luxury item, but in a growing number of areas, it has become a necessity, especially for vulnerable people.”

— LARISSA LARSEN, PROFESSOR

Planners typically turn towards methods like planting shade-providing trees to provide relief from heat. But Larsen says they need to think about the indoor environment as well. “Urban planners need to recognize that the next step is the home” and making sure that residences are “efficient, comfortable and safe.”

But even if vulnerable populations can afford to run their air conditioning, that wouldn’t matter during power outages. A separate study published by Larsen last year shows that a multiday blackout during a heat wave “could more than double the estimated rate of heat-related mortality” across Atlanta, Phoenix, and Detroit. The study calls for a more resilient electrical grid and greater use of tree canopies and high albedo roofing materials — reflective surfaces that don’t hold the heat. Larsen says it’s important to incorporate these types of passive cooling strategies into new buildings and building repairs.

Together, all of these measures — affordable air conditioning, better-built homes, and more reliable electricity — could dramatically reduce the mortality rate during extreme heat, Larsen says.

“We used to think of air conditioning as a luxury item, but in a growing number of areas, it has become a necessity, especially for vulnerable people,” she says. “It’s important that we continue focusing on this issue and the other solutions to dangerous indoor temperatures so that we don’t lose more people.” — Julie Halpert

With Post Rock, a Taubman College research team led by Associate Professor Meredith Miller is developing an innovative cladding made from automotive plastic scraps

IMAGINE THE EXTERIOR WALLS OF YOUR OFFICE building were covered with a plastic waste product recovered from automotive plants — a durable, hybrid material that’s also eco-friendly.

Meredith Miller and a team of fellow Taubman College researchers are in the latter stages of a long-running project to create such a building material. Their innovation, called Post Rock, is part of a sustainability movement that’s helping redefine the very nature of architecture.

“There was this idea that architecture could be really different,” says Miller, an associate professor of architecture and director of the Master of Architecture program.

“We could make buildings out of garbage and think that they’re beautiful.”

Miller, the principal investigator, is joined on the research team by Thom Moran, an associate professor of architecture, and Chris Humphrey, a lecturer in architecture. In 2023, the team received a two-year National Science Foundation grant for the Post Rock project.

The team’s plastic-forming process is already patented. Miller wants to commercialize this process by developing a building product made from automotive plastic waste. She says the NSF grant will allow them to examine the largest waste streams from the auto industry and

determine which polymer types may be suitable as a building material.

Automotive plastics are a perfect fit partly because they’re regionally available. Plus, Miller says, cars are well regulated so there are numerous safety and health guidelines about what can go into them. And, finally, any high-quality plastics used in vehicles are strong, durable, and impact-resistant — characteristics that would make them an ideal building material.

The application the team is targeting is a building cladding that makes up the outer layer of an exterior wall. But first, it must meet fire safety regulations. Miller is interested in learning “which of the various types of plastics used in cars would work for our process.”

The effort has been 10 years in the making for Miller and Moran. They were initially inspired by a 2014 article in Geological Society of America journal about a new kind of geological specimen in marine environments — “rocks” that are formed when plastic materials like fishing lines and shampoo bottles are fused with sand and seashells.

While these new rocks signaled the growing pollution problem, they also raised the possibility of combining waste plastics with other materials to make them useful. “There’s a kind of beauty to these objects,” she says. She wonders if “we could harness that beauty” to incentivize diverting that waste in the first place by making architectural materials that have a similar aesthetic — a “chunky hybrid” of natural and man-made materials.

The project started in a fabrication lab as a design experiment. But Miller realized that to create something that could be sold to architects around the country and have

Opposite: An exhibit of Post Rock exterior building cladding by Taubman College researchers is being shown at Craft Contemporary, a Los Angeles art museum, through January 5, 2025.

a significant impact on the waste problem, it needed to be at a much larger scale. Currently, the research team is designing a mockup of a portion of a wall made with this recycled material that will be rigorously tested.

One appealing feature is that Post Rock could have a “regional flavor.” In other words, Michigan Post Rock made from automotive waste could look different from Post Rock made from waste in other areas.

Within the next two years, the team will decide whether the results are promising enough to launch a company and operate as a startup.

Another goal is to quantify and document the environmental impacts across the material’s life cycle and examine the journey the materials took.

While it’s too early to understand the impact of using this alternative material, Miller remains optimistic. “When you account for the whole building impacts of creating a lighter building and sequestering plastic,” it’s a promising technology, she says. “That’s why we remain committed to it.”

The research into Post Rock has given Miller an appreciation of how architecture relies on many other fields.

“We can’t just be laser-focused on our job,” she says. “We have to understand the broader ecosystem behind building construction if we want to improve our building sustainability.”

Ultimately, the research reflects how architecture can be reimagined to better protect the environment.

“Our expectations of what architecture can be can sometimes be limited,” Miller says. “To solve some of the problems of architecture’s disproportionate impact on resources and energy, maybe we have to not only make architecture more efficient but also change our imagination of what architecture can be.” — Julie Halpert

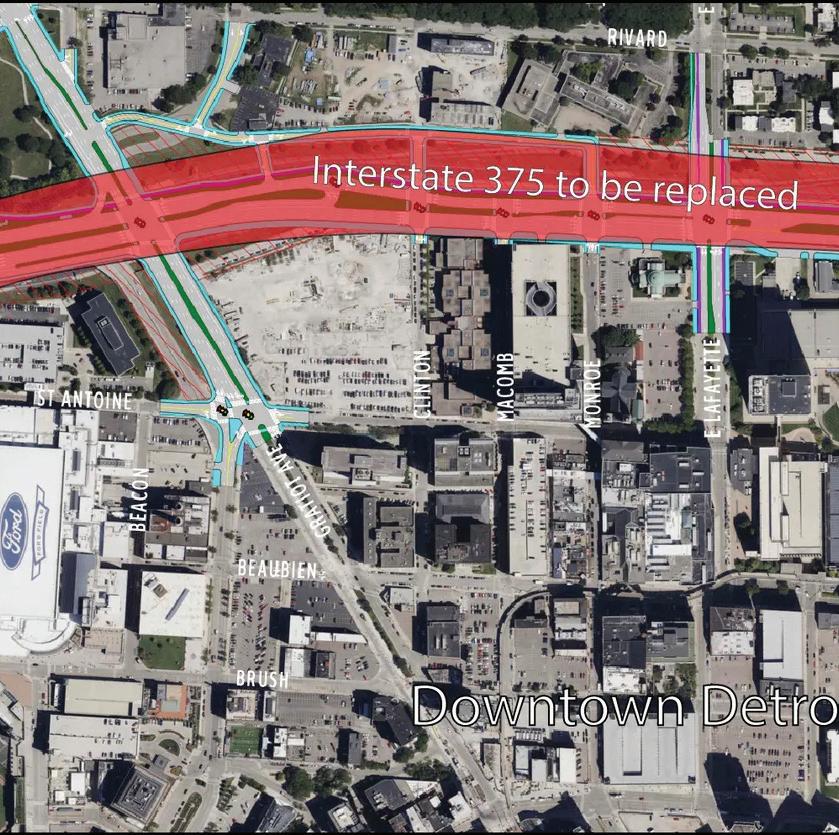

XIAOFAN LIANG, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR of urban and regional planning, has developed a conceptual framework called Network Duality that conceptualizes, analyzes, and contests issues around urban infrastructure. Network Duality acknowledges that such infrastructure — be it transport, social, or digital — can simultaneously be inclusive and exclusive, offering connectivity and access for certain populations, places, or types of flows, while marginalizing or restricting others. The duality emerges as diverse urban network systems interact with each other and with the built environment.

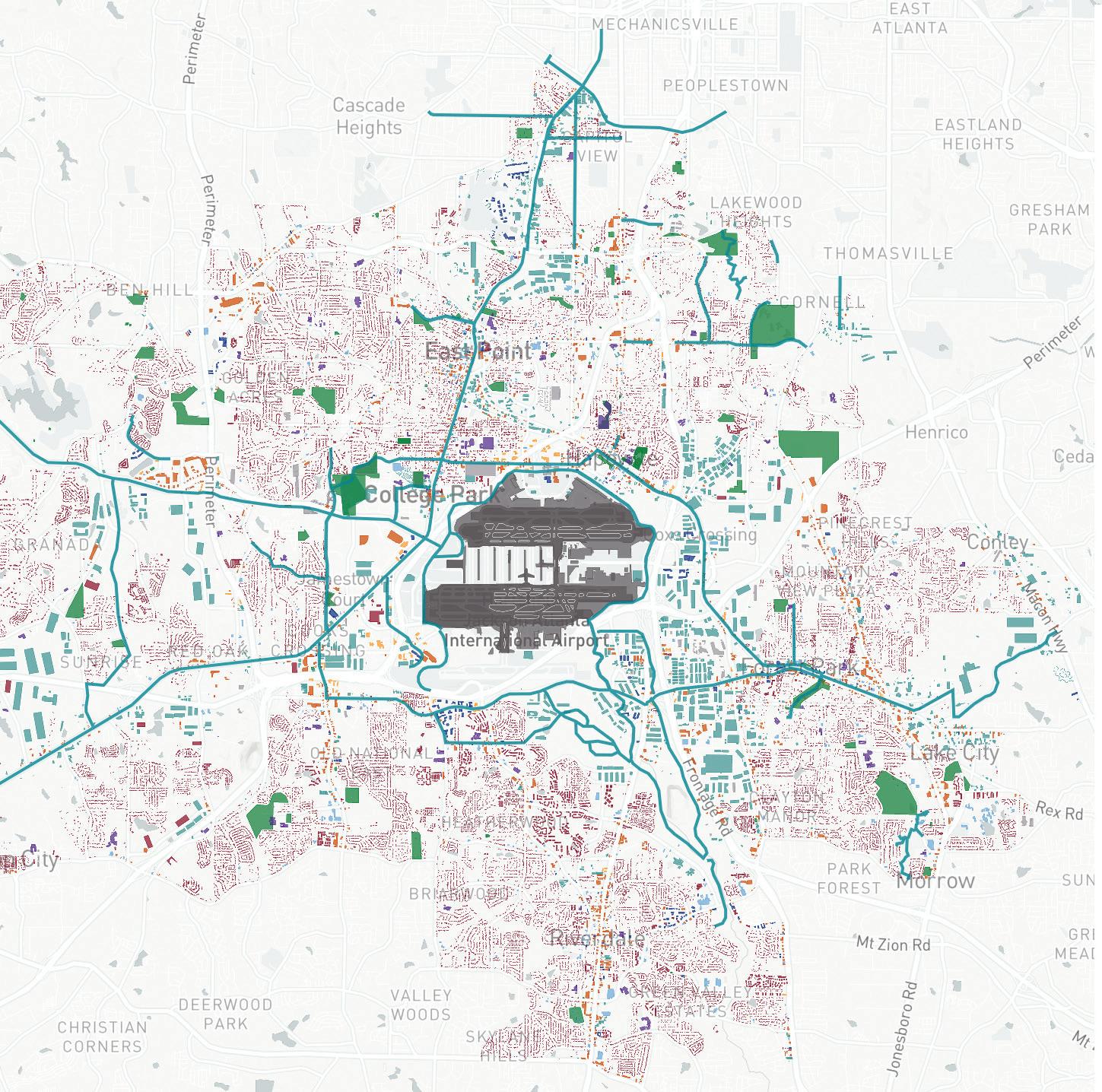

In one case study of the Network Duality principle, Liang and her research team studied how the size of a particular infrastructure — in this case, the Atlanta airport — becomes a barrier to local mobility.

Airports are critical connectivity infrastructures that support regional mobility and elevate cities’ positions in an interconnected global network. Yet, airports can also be mobility barriers that incentivize car-centric developments, preventing locals from getting to non-airport destinations. Using Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport and AeroATL Greenway, a recently proposed trail plan in the Atlanta region called the Aerotropolis, as a

comparative case study, the research team quantified the airport’s barrier effect on Aerotropolis residents’ biking and walking trips and evaluated the effect of the greenway on improving residents’ biking and walking trips distance and experience.

The results show evidence that the airport and its surrounding environment impede local mobility flows. The greenway has a stronger impact on improving trip experience than reducing distance, yet the specific effect varies by segments and implementation scenarios. These results are further validated on the route level with community stakeholders as they interact with a greenway web tool the research team developed in a participatory modeling workshop. Insights are consolidated into community trust and commitment to further the greenway implementation.

The work was developed with Perry Yang, professor of city and regional planning and architecture at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and curated through the Aerotropolis design studio in 2020 and 2021. The project is funded by The ACRP (Airport Cooperative Research Program) Graduate Research Award 2022, and supported by Aerotropolis Atlanta.

multiple forms of urban infrastructure including freeways such as I-375 in Detroit; pipelines; airports, such as Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport; and urban agriculture such as Sanctuary Farms in Detroit.

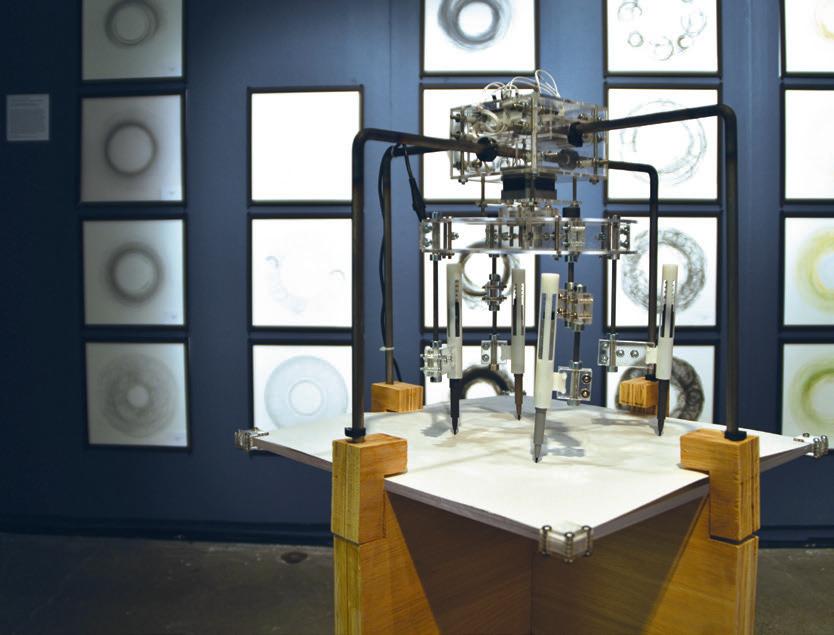

FROM ITS MODEST beginning as a student proposal to fund extracurricular research, the Architecture Student Research Grant (ASRG) program has evolved over the past decade into an annual grant-award competition that encourages young researchers to explore new ideas and showcase their creative projects.

“What makes the program so unique is that it is a student opportunity created by the students themselves,” says John McMorrough, professor of architecture. “It arises from the ethos of research and collaboration here at Taubman College.”

McMorrough was the architecture program chair in 2013 when a group of entrepreneurial-minded students pitched their ambitious idea for establishing a grant award program to support student research projects.

Many of the organizers had worked as graduate assistants with faculty on grant-funded research and wanted a similar opportunity to push the boundaries and possibilities of architecture.

“It was totally self-organized,” McMorrough says. “The students initiated the idea, organized the program, made the call for entries, invited faculty and students to judge the applications, and awarded the grants. My role was simply to cheer them on.”

A 2013 Master of Architecture class gift provided seed money for the initial round of grant awards. In subsequent years, the program has received funding through the architecture chair’s office and from private donors.

Every year the ASRG program awards up to $1,500 to each of three winning project proposals submitted by individual students or teams of students. The final installations and exhibitions are displayed at the Liberty Research Annex in Ann Arbor.

“The ASRG program gives students an opportunity to do research and realize something,” McMorrough says. “In the process, they also learn many valuable career skills, such as making a proposal, managing a project, dealing with budgets, and the difficulties in getting something built.”

Assistant Professor of Practice Lisa Sauvé, M.Arch ’11, MS ’14, and lecturer Adam Smith, M. Arch ’11, began donating to the ASRG program in 2016. The two are

partners in the Ann Arbor architecture studio Synecdoche, which landed its first project with a budget of just $1,500.

“We felt the ASRG program resonated with our own story on a similar scale and budget,” Sauvé says. “We wanted to contribute to the program to ensure its funding is maintained. For us, this felt like a way to pay it forward and create a similar opportunity for other students.”

Managing all aspects of a creative design project — from the schedule and budget to the construction and realization — provides students with an experience similar to working at an architectural firm and gives them an independent, real-life project for their portfolio.

“The ASRG program serves as a bridge between coursework and professional work while still offering guidance and support from the university,” Sauvé says. “It’s a great way for students to build their entrepreneurial endurance and determine whether they want to continue down that path and start their own venture.”

Taubman College students credit the ASRG program for preparing them to launch successful careers in professional practice, teaching, or sometimes both.

“ASRG provided a moment for me to pursue several opportunities otherwise not offered to me in grad school,”

In the past decade, the Architecture Student Research Grant (ASRG) program has yielded many innovative design projects.

observes Collin Garnett, M.Arch ’23, a design professional at Ply+ and an intermittent lecturer at Taubman College. “Of these, formulating a research project, writing a grant narrative, constructing a budget, executing design research, and planning an exhibition all rise to the top as experiences I am extremely grateful for. These experiences have allowed me to carry the energy from my graduate education into the professional realm, post-degree.”

“The ASRG gave me valuable experience in pursuing independent research, grant writing, documentation, and teamwork,” adds Elizabeth Ervin, M.Arch ’23, an architectural designer at MSR Design and an adjunct professor at the University of Minnesota. “Our team developed the ability to set goals and worked to overcome design challenges. I made lasting professional connections and have continued sartorial architecture explorations.”

The ASRG program not only deepens students’ experiences at Taubman College, but also enriches the overall college culture, which embraces the creative exploration of design’s capacity to propose and realize, says McMorrough.

“This program is a way for our students to shape and contribute to the culture of the institution,” he says. “It serves as an important part of the ecology of ideas, visions, and productions that make the school more than a curriculum. It enhances our educational mission to provide the grounds of possibility for our students.”

— Claudia Capos

‘An

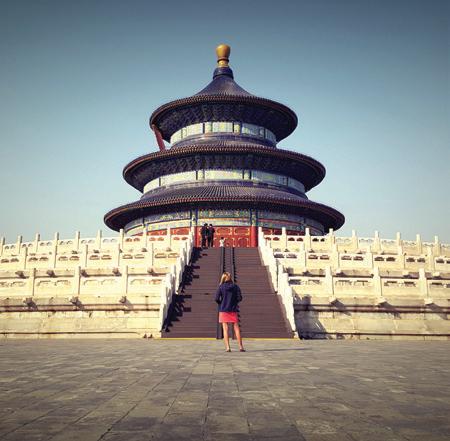

RAYMÓN RICHARDSON, M.ARCH ’25, and a group of fellow Taubman College graduate students traveled to Paris to study the future of commuting just as the French capital was gearing up to host the 2024 Summer Olympics.

The May 10–24 field study, led by faculty member Clement Blanchet, was part of the college’s new Proposition Studio option for Master of Architecture students in their final year. Students engage in international fieldwork and, upon returning to Michigan, are offered the unique opportunity to select electives tailored to their independent thesis research. This approach offers a dynamic blend of global immersion and targeted academic exploration — an evolution in architectural education.

“This opportunity to study architecture and urbanism in a city like Paris was an experience of a lifetime,” Richardson says. “Having grown up within an hour of the Motor City, it was quite invigorating to take on such a thought exercise in an era when the City of Detroit, Ford, and others have begun to redefine their relationship with our, generally, car-dependent culture. As a future design professional, this experience has piqued a new interest and inspired me to expand my architectural studies further into the world of infrastructure and urbanism and the role it plays (or doesn’t play) here in the United States.”

At the same time Richardson and his classmates were studying in Paris, some 4,000 miles away in India, another team of graduate students, guided by Mumbai-based architect Ayaz Basrai, were investigating how traditional craft practices can be reinterpreted through contemporary technology and advanced fabrication tools.

Basrai, who’s with the Goa Collective and The Bus Ride architecture office, challenged students to blend cutting-edge technology with cultural heritage, fostering a deeper understanding of the potential for innovation within craft industries.

Connecting students with leading practitioners around the globe is a cornerstone of the Proposition Studio and the college’s longstanding Spring Travel Course program, says Anya Sirota, associate dean for academic initiatives and associate professor of architecture. The opportunities bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, providing students with invaluable insights from industry leaders.

“These global engagements expand students’ professional networks while enriching their educational experience through exposure to diverse perspectives and cutting-edge practices in architecture and design. This intersection of cross-cultural dialogue and advanced methodologies deepens their understanding of the global dimensions of the discipline,” Sirota says.

Through the Spring Travel Courses, Taubman College students have traveled to more than 40 countries on six continents — from Austria to Ghana to Ukraine — since 2008. The courses, held in May and June, generally span several weeks to two months. Students receive $1,500 in support for international travel and $1,000 for domestic travel.

“Our programs introduce students to design methods that extend beyond the conventional confines of studio or capstone courses,” Sirota says. “This year, for example, our students explored archival research in

Amsterdam, enhanced their on-site documentation skills in Rome, and honed their interview techniques in Zurich. These competencies are invaluable, yet they often fall by the wayside in traditional courses due to the constraints of academic scheduling and accreditation requirements.”

Selecting which courses get approved is akin to a casting process, Sirota said. Faculty with international research agendas present their course proposals, and students then choose topics and geographies they find inspiring.

The program includes three-credit elective courses open to all undergraduate and graduate students. This year, students journeyed to Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland. Other students interested in public interest design studied in Brazil with the U-M Public Design Corps.

Students in the final year of the Master of Architecture program can now take the six-credit travel Proposition Studio. These are the students who traveled to India and France in the spring.

Taubman College students have traveled to more than 40 countries for unique field study opportunities — from Austria to India to Ukraine.

“Visiting a country such as India exposed me to several issues one may need help finding or considering in the United States, opening my views and beliefs,” said Scott Kulis, M.Arch ’25. “This experience started with minimum knowledge of the culture and people and led to a world of knowledge and experience in six weeks. It provided a grand opportunity not only as a student but also as a person.”

Sirota said the insights gained from studying abroad can significantly enhance an architect’s work in the United States. Having led several travel courses herself, she recalls taking students to France to examine the transformation of post-industrial sites into experimental cultural venues. These experiences provided valuable methodologies that could be effectively adapted to the North American context, particularly in Detroit.

“There are myriad interconnected narratives our students encounter internationally, enriching their understanding and sensitivity,” Sirota said. “These firsthand experiences with global practitioners are indispensable, fostering a level of empathy and insight that can’t easily be replicated in the classroom. I consider this an essential component of an architect’s education, especially those who want to make the world better.”

Farah Ossaimee M.Arch ’25

A: Public interest design overseas.

Why is this interesting to you?

My passion for public interest design started during my first internship at the Detroit Collaborative Design Center (DCDC) at the University of Detroit Mercy. Seeing the community actively shape their neighborhoods was inspiring — the kids’ curiosity-fueled excitement, the deep nostalgia in people’s stories — it all changed how I view architecture’s role in people’s lives. Most architects agree our duty goes beyond just designing structures; it is about problem-solving. You don’t design. You problem-solve through design. You don’t design. You listen and then answer through design. At DCDC, our goal was not to get a bunch of 2x4s out there. Our goal was to listen to the community, identify their problems, begin problemsolving, listen to community feedback, and go back to the drawing board for another iteration.

It was in the summer of 2022 that I, with the team of DCDC, designed a playscape for our client Brilliant

Detroit: a nonprofit aiming to increase educational levels and create a flourishing environment for the kids of the community, celebrating all their beautiful abilities. We held engagement events where kids got to model their hopes and dreams for the project. My job was to translate ‘kid language’ into architectural logic. After the initial iteration, kids were invited to critique our work. After more iterations, our final ‘show-and-tell’ that concluded our schematic phase of the project was filled with gasps and excitement from the kids. The Littlefield Playscape was officially kids-approved (and Brilliant Detroit, of course) and ready to be built. Currently, the project is on hold waiting for funds being raised by Brilliant Detroit. My experience working at DCDC introduced me to another side of architecture that is not completely taught in schools. The community has a powerful voice. If you combine that with an architect’s power of problemsolving, the results are beyond beautiful.

Coming from Egypt, a country deeply affected by the 2011 Arab Spring, I want to bring public interest design back home. Even though participatory design isn’t widespread in Egypt, I was able to hunt down and talk to some design centers similar to DCDC. While they do great work, working with a population of over 100 million, a lot more needs to be done. More people need to be heard. More stories need to be listened to and preserved. With various economic, political, cultural, and historical factors at play, my experience at DCDC has made me think critically about adapting the American model for Egypt, and similar third-world countries. I believe my people’s voices can drive incredible design solutions, and I’m determined to explore how to make that happen.

Joshua Nicholson B.S. UTech ’26

A: Housing commodification.

Why is this interesting to you?

During the urban technology Spring Intensive, we spoke with many community leaders on housing affordability and sustainability. These conversations sparked my interest in novel ways to conceptualize the housing issue and how it connects with transportation and economic planning. Why does building cities with good urban fabric lead to a drastic rise in housing costs and how can we create both walkable and affordable cities?

Many cities renowned for their strong urban fabrics, walkability, and good social scene are also exceptionally unaffordable. In many ways, this is because of the lack of housing supply and emphasis on single-family zoning across the country. However, it’s also because of the demand for good cities in general. In places like Logan Square in Chicago, new transit-oriented developments have drastically increased the rents and property taxes of neighboring homes, partly because many people will pay a premium to live near mixed-use zoning and transit connections at the expense of existing residents.

I’m interested in learning more about how we can solve this problem and where technology and data fit into the picture. If we can’t achieve complete housing decommodification, can we make models to predict at-risk neighborhoods for gentrification and preemptively freeze or control their rents? I’ve learned to love good urban spaces, and I want everyone to be able to afford to live in them.

Jenna Jarjoura B.S. Arch ’25

A: How food can be incorporated into architecture. Why is this interesting to you?

A lot of what I like to do outside of school is surrounded by food. I have worked on the U-M Campus Farm since my sophomore year and I love being on the farm. Along with the long hours I have spent working laborious shifts, I also work at the farm stand. I spend my Thursdays working on central campus sharing information with the U-M and Ann Arbor community about what it means to grow your food, make it available for all, and set it at a reasonable price that fights against healthy food having to be overpriced.

Once I entered UG1 I knew that I wanted to find ways to bring plants, specifically food, into my work. I found small ways at the beginning by finding ways to connect a house, like the University of Limerick President’s House, to the outdoors and its proximity to a river and natural landscape. Then, I was asked to build a field house and found it difficult to not see a site as a place to grow food for the local community. I created a crop rotation that benefited from the interaction between people of all ages coming onto the site to play sports as well as plant crops.

This past summer I had the opportunity to live in Amman, Jordan. I was surrounded by fruit trees and a culture that loves to share food and come together around food. I love to consider what the world would look like if this was the reality of the United States. And, I hope to continue creating hypothetical architecture through my studio career at U-M that considers this relationship more closely than what already exists.

Michael Pukszta, B.S. ’87, M.Arch ’89, Global Healthcare Practice Co-Director at Cannon Design, and Roy Khoury, M.Arch ’25, discuss architecture generalists vs. specialists, giving back, and sustainability

Michael Pukszta

B.S. ’87, M.Arch ’89

PUKSZTA: There is absolutely no way that I would be doing what I am doing today without my time at the University of Michigan and connecting with the people that I connected with. Just as I was getting my graduate degree and trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life, I was at a meeting and the principal of a healthcare design firm was there. As we were leaving, he said, ‘Do you want a job?’ He was a Michigan grad as well, hired me and became my mentor in healthcare architecture. So here I am today leading one of the top healthcare architecture firms in the world, and it was all through my connections and my education at Michigan that got me where I am today.

KHOURY: My time in graduate school at Michigan has been all about trying every single thing I can get my

Roy Khoury M.Arch ’25

hands on, whether it’s trying the student publication, trying leadership positions on the student council, doing the crazy project with an abstract idea, or doing that very tangible sustainable project, so it’s very much all over the place. Sometimes I worry that I am trying too many things. At one point do I hit the brakes and focus on one approach?

PUKSZTA: That’s a good question. I got lucky that I just happened to fall into something I really enjoy and made a career out of it. I feel like I’m making social investments, creating positive environments for people when they’re either at the worst moment of their life, possibly dying, or at their best moment, having children and celebrating life. And it’s so cool to realize that through the built environment I can have an impact as an architect on people that

“

I LOVE TALKING TO STUDENTS AND MY ADVICE IS ALMOST ALWAYS, ‘IF THERE IS A DOOR THAT IS PARTWAY OPEN, YOU SHOULD PROBABLY GO THROUGH IT. YOU NEVER KNOW WHAT’S GOING TO BE ON THE OTHER SIDE.”

— MICHAEL PUKSZTA B.S. ’87, M.ARCH ’89

I don’t even know. My recommendation usually for students is to do what you are doing: explore all kinds of things. I really think you should be well-rounded. To be successful as an architect you need to be insanely curious — curious about all kinds of things. I love talking to students and my advice is almost always, ‘If there is a door that is partway open, you should probably go through it. You never know what’s going to be on the other side.’ And while I am a subject matter expert, I can’t design a hospital on my own. I need to pull in 10 other people who are social anthropologists, experiential experts, and design experts focused on the environment. I need to surround myself with a whole team of people who have different backgrounds.

KHOURY: When I think about how architecture can improve society, I think about what have I done vs. how can I do it bigger or better. Going into my thesis year, I’m in a studio that’s dealing with degrowth, so that’s a topic of interest, but the reality is, construction isn’t going to stop. We need it; it’s intrinsic to our continuation. The biggest tool we have is knowing how to build properly. How can architecture influence societal change towards something that’s more sustainable, more ecological, something that can alter the day-to-day lives of people in a better way and in a more healthy way?

PUKSZTA: Our impact on society is huge. I’ve worked for one firm for a very long time, and we kind of reinvent ourselves every five years. This last time we asked our entire staff, ‘What do you want to accomplish as a person, and how can we be a firm that helps get you there?’ So many of the answers came back as, ‘I want to make the place I live better, I want to make my neighborhood better, I want to make my city better, I want to improve the things that are around me and my family.’ We took a look at that and asked how we could create a firm that would allow us to do just that. And it changed our entire business model. We’ve focused more on local work and local opportunities. We’ve created something we call Open-Hand Studio where our designers provide their services to people in need with pro bono work. An example is an area north of St. Louis that’s really challenged as a healthcare desert.

We worked with a woman there, a midwife, who is creating a birth village that’s designed for people who have limited access to healthcare.

KHOURY: On the topic of climate, this has been a subject that’s been very present in the college. My entire year has been around sustainability and climate change. I’m also a graduate student instructor for the sustainable systems course with the professor who is spearheading the college’s new Climate Futures platform, Jen Maigret. So it has been the headline topic of my year.

PUKSZTA: This is one that’s evolved in my career because when I started practicing, sustainability wasn’t a word we used very often. We really didn’t think deeply about the environmental impact of what we were doing. Spin that forward a couple of decades and we think a lot about the environmental impact of what we’re doing. Part of the challenge we have is convincing our clients that it’s an important conversation when they’re in the middle of a capital investment. Architects are really pushing the environmental aspects, but we still have a long way to go as a society to embrace a lot of those principles.

KHOURY: How do you navigate those conversations when you’re talking to a client whose project is in their hands and the capital is in their hands?

PUKSZTA: That’s a tough question. When you walk in and start this conversation, just about any client I’ve ever talked to says, ‘It costs more money to be sustainable. I don’t have more money.’ The reality is that there may be some premiums associated with it, depending on the level of sustainability, but we’ve been able to start to turn the question into a vocabulary that they understand. So we ask the question, ‘Do you want your employees to be healthier and have fewer sick days, and be more productive when they’re here?’ Of course, the answer is yes. And when we say we can improve the air quality, use safer building materials, improve natural light and all of that, they’re all about it. In that way, we can start to achieve more of our sustainability goals if we start presenting things differently to our clients.

In our rapidly advancing world, students excel through life-changing educational experiences, and faculty thrive with support for opportunities that enable them to flourish and take on complex challenges

THE WORLD CALLS FOR CHANGE , and at Taubman College, we answer that call. Our size is a strength. Our agility is an asset. Our commitment is unwavering. For more than 100 years, we have been redefining the power of higher education with a diversity of thought and innovative design culture that enables us to go beyond ideas, translating them into future-focused, real-world, interdisciplinary action.

At Taubman College, we rethink building methods and material systems as sustainable solutions to decarbonize the built environment. Our experts lead the way through initiatives such as our Architectural Computational Design and Construction Cluster and Low-Carbon Building R+D Initiative.

We pursue strategies to expand housing access and affordability through our Collective for Equitable Housing. We engage communities in socially driven design through our Public Design Corps. We activate collaborations in climate action, resilience, and equitable city-making with experts from across Taubman College and U-M, as well as with industry and community partners, including our new Climate Futures platform.

We focus on the health and well-being of people and the planet by confronting design-driven inequality through our Design and Health group, finding new ways to protect our water as an invaluable and finite resource, enabling sustainable food systems, and understanding and mitigating the impact of heat to ensure communities develop resilient planning strategies.

In high-tech, collaborative maker spaces like our renowned Digital Fabrication and Robotics Lab,

we explore how technology can improve the built environment and promote equitable outcomes. In the Taubman Visualization Lab, we develop novel visualization techniques that use virtual and augmented reality to communicate innovative ideas.

These and other uniquely Taubman initiatives show how we design, plan, and build a more beautiful, sustainable, and just built environment.

Creating new knowledge starts with life-changing learning in our classrooms, where we equip today’s students to become tomorrow’s leaders. That learning comes from a dynamic faculty developing bold solutions through research and creative practice.

Donors play a vital role in our mission. Your support fuels creativity and collaboration, the driving forces behind Taubman College’s bold design for a future that builds on our legacy to create new approaches that meet a fast-changing world.

Our goal is to raise $25 million to support students, faculty, and experiential learning.

We aim to ensure that financial constraints do not hinder students’ potential, creating pathways to a more inclusive, diverse, and dynamic profession. We must support field-leading faculty who pursue solutions and inspire the next generation. Join us in building a world where every aspiring architect, designer, planner, city-maker, and real estate professional has the opportunity to make a meaningful impact. Together, we can shape a future where innovation flourishes, diversity thrives, and the built environment improves life for people and the planet.

Talent and ambition know no bounds, but financial barriers often prevent promising students from pursuing higher education. At Taubman College, scholarships play a vital role in ensuring that every student has the opportunity to excel.

Socioeconomic disparities continue to limit access to higher education, particularly for underrepresented groups. By providing scholarship support, we create pathways for high-achieving students from diverse backgrounds to enter the architecture and planning professions, enriching our academic community and reflecting the diversity of the world we collectively want to make better.

Endowed Scholarships last in perpetuity, creating sustained impact — starting at $25,000 (paid over a five-year period).

Expendable Scholarships make an immediate impact on students — starting at $15,000 (paid over a three-year period).

At the heart of our excellence lies a commitment to fostering a culture of discovery and imagination as our field-leading faculty members push the boundaries of knowledge and shape the future of the built environment. This centers on recruiting, retaining, and equipping the best minds to do their greatest work.

Our faculty are more than educators; they are trailblazers in their fields and experts in research and creative practice. They are award-winning innovators recruited by industry partners and academic peers to lead professional and scholarly organizations and initiatives.

Endowed Professorships —

$2,500,000 to endow (paid over a five-year period). In our pursuit of excellence in a highly competitive market, one of our primary objectives is to establish endowed professorships that will attract and retain exceptional faculty. Endowed professorships honor outstanding teaching and research and provide the resources and freedom for professors to conduct innovative research and inspire future generations.

Visiting Professorships —

$1,500,000 to endow (paid over a five-year period). Visiting professors who join us from other institutions or professional practice bring invaluable expertise and diverse perspectives to Taubman College, enriching students’ educational experience and elevating our global reputation. Establishing endowed visiting professorships allows us to host renowned scholars and practitioners who inspire and mentor students with fresh insights and ideas.

Faculty Development Professorships —

$1,000,000 to endow (paid over a five-year period). Investing in faculty development professorships enables Taubman College to nurture emerging talent in our fields, providing crucial support for junior faculty to excel in teaching and research. These endowed positions empower rising stars to achieve their full potential, driving innovation and inspiration in our classrooms and studios.

Growing up in Detroit, Naomi Bailey, M.U.R.P. ’25, felt a true sense of community. She rode bikes around the neighborhood with her friends, played freeze tag and cartoon tag, climbed trees, and knew most of her neighbors, including the older woman across the street, Miss Brenda. Today, Bailey, 23, feels that sense of community is being replaced by “crime and hatred” and as an aspiring urban planner, she hopes to start bringing people back together.

“We need to get back to that sense of trust, where people say, ‘Hey, I’ll be out of town for a few days, will you watch my house?’” she says. “I know there are a lot of people my age who don’t have that sense of trust and community. But I want them to realize that community is very important. At some point, our parents and grandparents will pass the baton to us, and I just want my generation to be well prepared and well equipped to handle that.”

Bailey earned a bachelor’s degree in landscape architecture from Michigan State University. She plans to use that training with her urban planning degree to design outdoor spaces such as parks while collaborating closely with community members. Interning at the Lord Aeck Sargent design firm for the past year, Bailey has been involved in neighborhood planning projects in Cincinnati and Flint. Her long-term plan is to use her experience and skills to make a difference in her hometown. “I really want to make an impact on the city, on the neighborhoods, and the best way for me to do that is to be a resident of Detroit.”

Bailey was awarded a Taubman Scholar award and also is the recipient of the Stanley and Margaret Winkelman Fund scholarship. “I’m very grateful that I have the scholarships that I have so I am not drowning in debt,” she says. Graduate school is difficult, Bailey adds, but she is passionate about succeeding and making a difference in the world. “It took some time to find my footing, but it’s important to have someone who is willing to put in the work to teach me, and I’ve really gotten that from the professors here,” she says. “I’m a growing person, and I know in 20 years I’ll still be growing, and there will still be people who are willing to teach me. And I appreciate them and I appreciate myself for not giving up.”

A gift to Taubman College supports future leaders like Naomi.

taubmancollege.umich.edu/give

THE LATE ROBERT METCALF’S LEGACY of giving to Taubman College lives on through grateful students like Nicholas Pettigrew, B.S. Arch ’25. Pettigrew, a Washington, D.C., native, is supported generously by the Robert and Bettie Metcalf Architecture Scholarship to pursue his undergraduate architecture degree as long as he maintains a 3.0 grade point average.

“The scholarship definitely provides relief in terms of affording an education here at the University of Michigan being that I am an out-of-state student,” Pettigrew says. “And it’s motivation for me to keep progressing and making sure my GPA remains well above that 3.0 threshold.”

An Ohio native, Robert Metcalf established deep roots in Ann Arbor. After serving in World War II, he earned a bachelor’s degree in architecture from U-M in 1950 and remained in the area with his wife, Bettie, a fellow Ohioan. In addition to running a successful architecture practice in Ann Arbor, Metcalf had a long teaching and administrative career at U-M, ultimately serving as dean of the College of Architecture and Urban Planning from 1974 to 1986.

When Bettie died in 2008, Metcalf donated $200,000 in her memory to create an endowed scholarship for

talented Master of Architecture students who, like him, come to U-M from outside Michigan.

Metcalf’s philanthropic legacy continued after his 2017 death with a planned gift. His estate gifted $3.17 million to Taubman College to create a scholarship for nonMichigan-resident architecture students in both the undergraduate and graduate programs.

The transformational endowment exists in perpetuity, supporting many future generations of Taubman scholars from across the country and the globe. The gift is attracting the best and brightest students to U-M — students like Pettigrew — allowing them to pursue their educational dreams while reducing their financial burden.

Growing up in the nation’s capital, Pettigrew developed a passion for the visual arts and worked hard to refine his craft. This determination “allowed me to present a portfolio that successfully got me into architecture school.”

“Being an architecture major,” Pettigrew says, “I hope to go into the field with a long-term goal of becoming a licensed architect so that I can uplift communities through building design.”

INNOVATIVE UPCYCLED building material sourced from regional waste. Passive cooling systems for selfbuilt housing in low-income communities in Brazil and Colombia. An interdisciplinary research collective dedicated to addressing pressing issues and opportunities in housing and urban development.

These are just a few of the many research initiatives led by Taubman College faculty with the support of donor funding from individual and corporate partners.

Keeping the college’s research pipeline full of innovative architectural and urban-planning projects is central to the University of Michigan’s mission as a public institution to serve society through education, inquiry, and knowledge creation, says Kathy Velikov, professor of architecture and associate dean for research and creative practice.

“Our job as educators is to maximize the potential of our students, and, thereby, society in the future,” she says.