PROFESSIONAL PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

MASTER OF URBAN PLANNING

PROFESSIONAL PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF

MASTER OF URBAN PLANNING

This paper is one of two parts of the professional project. The second part is my creation of The UnfoldKit which can be viewed at theunfoldkit.com

The UnfoldKit is a toolkit for developers, architects, planners, and designers to develop real estate with the intentional inclusion of community voice and input.

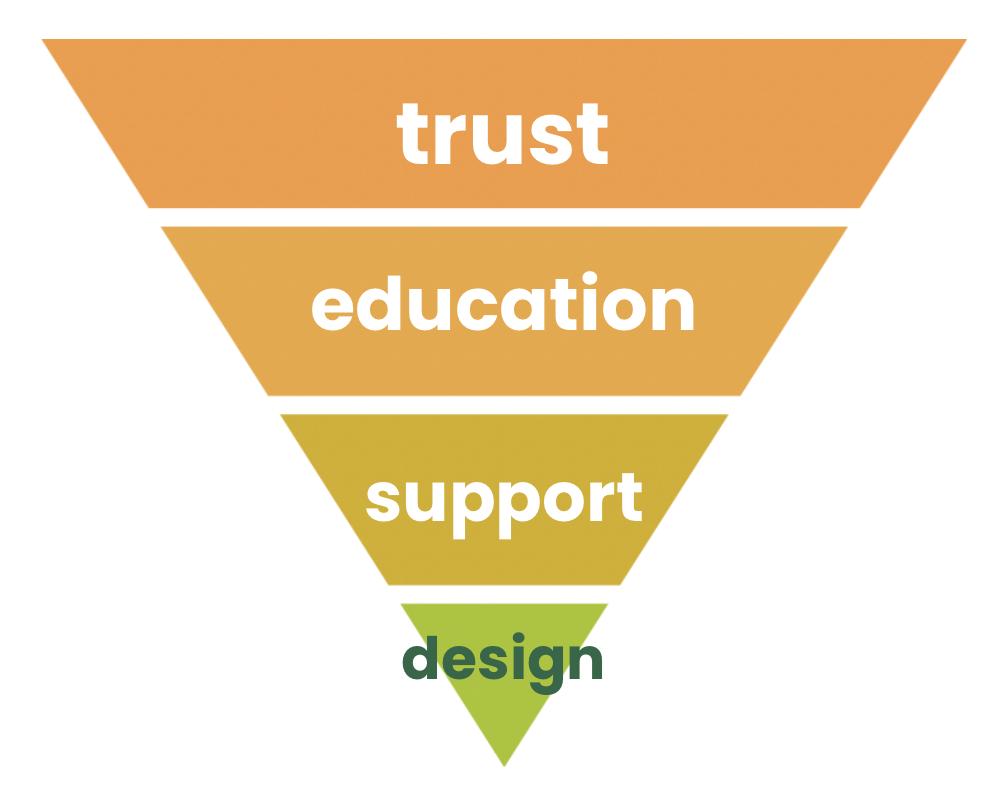

With the application of participatory planning methods, human-centered design, and learned experiences from affordable housing professionals, the toolkit's goals are to help users:

Create frameworks of community-centered design in the real estate development practices of LIHTC housing and beyond.

Move communities towards a place where LIHTC housing and real estate development is understood, welcomed, and advocated for by the public.

Design and build with community-driven innovation, sustainability, and equity.

The structures we design and the impact of the built environment will be experienced by generations of people.

Let's build with community voice.

Founder of prcss studio & The UnfoldKit, I am an MBA & Urban Planning Graduate (2023) from the University of Michigan. This project was inspired by my experience as an affordable housing Project Developer at Eden Housing, Inc.

Anna Lam

Pauline Weaver Senior Apartments Fremont, California

Charles Apartments & Cypress Gardens Marina, California

Anna Lam

Pauline Weaver Senior Apartments Fremont, California

Charles Apartments & Cypress Gardens Marina, California

“We’re in the business of interpreting other people’s cultures… We are conduits for their expression. [Of course,] We’re getting kicks out of it too; we have to be happy with what we’re doing as artists and architects. But, we cannot do it in isolation.

We’re not doing our ‘ own thing’ ever.

As soon as you start doing your ‘ own thing’, you’re just simply imposing on other people's lives and you’re going to eventually do something very stupid.”

Michael Pyatok Activist, Architect, Professor of Architectural Design Principal Emeritus and Founder of PYATOK Architecture + Urban Design

With the continuing and growing need for affordable housing, governments all over the United States are working towards solutions to address the demand for housing particularly for low-income populations that cannot keep up with the rise in rents One of the most prominent solutions in the past two decades is the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program (LIHTC)

Created in 1986, LIHTC is a federal subsidy used to finance the construction and rehabilitation of low-income affordable rental housing. With over 3.7 million units constructed or rehabilitated since its inception, the LIHTC program has impacted over 8 million families and is seen as one of the most successful public-private partnerships among policymakers

Despite its achievements, the "public" is lacking in this public-private partnership As community engagement is not a requirement or even a suggestion within a majority of the LIHTC program at the federal or state level, the presence or lack of engagement is mostly dependent on the planning code in each city and the agency of every developer. While some cities or municipalities will dictate direction for community notices or meetings, in-depth engagement is rarely ever required and most cities have no such direction at all In scenarios where there is some requirement, developers and architects will follow the guidelines but only the smallest subset will venture beyond the minimum suggestions for outreach. Only in community-forward areas facing heightened challenges with affordable housing, such as the Bay Area or New York City, will one see opportunities for in-depth public participation surrounding an affordable housing development

Considering the goals of the LIHTC program and the impact of real estate development, there exists a disconnect between development processes and the communities that the development serves. This disconnect could be bridged to achieve more equitable and sustainable housing solutions. Community engagement can be pursued as a standard to educate the public and build momentum in the affordable housing space all while pushing the boundaries of community-centered design

Through literature reviews and professional interviews with developers, architects, planners, and designers, this project consolidates the context, experiences, and frameworks surrounding public engagement in affordable housing development.

Although housing is a basic human need, a growing number of families are finding it increasingly impossible to find affordable housing. Housing is considered “affordable” if it consumes less than 30% of a household’s total income. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, over 40% of renter households in the country spent more than 30% of their income on housing costs during the 2017-2021 period That’s over 19 million households who are cost-burdened renters ((US Census, 2022) Currently, the United States experiences a shortage of over 7 million affordable homes for households with extremely low incomes or households with incomes at or below the poverty line or 30% of their area median income (NLIHC, 2023). Moreover, as of 2022, there are over 580,000 people experiencing homelessness every night (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2022)

Nationally, there are only 33 affordable and available rental homes for every 100 extremely low-income renter households. Among states, the supply of affordable and available rental homes ranges from 17 affordable and available homes for every 100 extremely low-income renter households in Nevada to 58 in South Dakota. This number is 24 in California and 36 in Michigan (National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2023) This shortage of affordable housing exists in every state and every major metropolitan area

The lack of adequate affordable housing has a host of negative effects on communities Not only does every person need a safe place to rest and recharge for the next day, they also deserve the foundation and stability that housing offers one to grow upon Unhoused individuals and cost-burdened families experience greater challenges relating to food security, physical and mental health, transportation, education attainment, and overall social stability.

While the prevailing public dialogue demands more affordable housing, there are many misconceptions about what it even is, and when the demand is finally answered, community pushback may present itself. The public’s demand for affordable housing is felt on a personal level but hesitation arises when the opportunity to meet that demand is available. Rather than pushing the public away, those in power such as developers, architects, and planners, should invite the public into the process Only by gathering the voice of those who demand housing will we be able to appropriately measure the need and build housing in respect to it

As it currently stands, everyone knows that we need affordable housing but we are not financing and building enough in response to this need that is so clearly told in decades of quantitative research. If more of the public were not only knowledgeable about affordable housing but were also able to take part in the design process, the call for affordable housing would undoubtedly be louder and more abundant.

As affordable housing developers are already following a set of regulations and putting more time into sustainable design to achieve the most competitive application, an opportunity exists for them to lead the way in bringing the public’s voice into the design processes What is overlooked or seen as something to check off the list should really be valued and standardized - public participation not only has the capacity to push equity and sustainability, it also has the power to drive capital into housing programs and initiatives.

Without appropriate public participation, we are planning and designing communities at the risk of long-range and long-lasting problems across a broad social, cultural, income, racial, and ethnic spectrum.

As Michael Pyatok shares, “In any neighborhood or campus, regardless of income and privilege, there is a pride of place universal to all residents that must be respected and put to use; there is a sense of history which any newcomer must get to know, understand, and ingest; that all people are potential sources of ideas about planning, urban design and architecture; that the merging of economic, social, cultural, ecological and technological factors into a poetically inspired environment cannot be done by us alone” (PYATOK, 2023).

Community engagement has a place to drive the public support and human-centered design of real estate development in a direction that is sustainable and sensitive to a community’s cultural and social origins.

With over 3 7 million units of affordable housing constructed or rehabilitated since its inception in 1986, the LIHTC program is one of the most important financial resources for creating affordable housing today While the LIHTC program is seen as one of the most successful public-private partnerships, the public’s voice is missing in this partnership.

To understand the lack of community engagement in the LIHTC development process, it is integral to first understand how the LIHTC program works One can address the problem by proposing solutions at higher levels of government such as at the federal or state level, but additional regulations would not only take time to implement, they may also be inequitable and unsuitable for all jurisdictions under the respective government. One can then recommend solutions at lower levels of government in cities and municipalities, but local governments vary greatly in capacity, innovation, and funding while also managing a number of public administrations and issues

In this section, we will explore regulations as it relates to LIHTC development at the federal, state, and local levels. This is important for understanding the top-down guidance in the program and how the variety of regulations can affect how communities are built - along with how there may be an absence of public participation in the development process. Following this, the agency and responsibility of the developer in bringing in public input should be clear

In the past century, governments at the city, state, and federal level have worked to address the need for housing. They have also evolved in their solutions tackling housing development for low-income populations. In 1923, the country's first public housing project, Garden Homes, was built in Milwaukee; In 1934, the Public Works Administration (PWA) developed the first federally-funded public housing projects; In the 1950s, large-scale urban renewal projects ensued as a result of The Housing Act of 1949 and The Federal Highway Act of 1956 In 1965, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) was created, introducing rent subsidies, and marking the beginning of a shift towards privately constructed low-income housing. Today,

low-income housing is funded by a variety of government programs, but mainly through the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program (Schmitz, 2005).

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program was created by the Tax Reform Act of 1986 and is administered by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and detailed in Section 42 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). LIHTC provides an indirect federal subsidy used to finance the acquisition, rehabilitation, or new construction of rental housing targeted to lower-income households.

The program is designed to encourage the private sector to invest in multifamily affordable housing through the application of tax credits There are two types of tax credits available through the LIHTC program: 9% and 4% credits. The 9% credits come with a larger federal subsidy, are allocated through a highly competitive process, and largely fund new construction of multifamily properties. The 4% credits are considered non-competitive, and are layered with other federal subsidies like tax-exempt bonds (Novogradac, 2022)

Under LIHTC, developers of affordable housing can apply for tax credits to offset their or their investor’s federal tax liability. The tax credits are awarded based on the number of qualified affordable housing units in the development, the level of affordability of the units, and other criteria set forth. There are three ways a development would be considered “affordable” and qualify for LIHTC funding (26 U S Code 42, 1986):

1 At least 20% of the project’s units are occupied by tenants with an income of 50% or less of area median income adjusted for family size (AMI).

2. At least 40% of the units are occupied by tenants with an income of 60% or less of AMI.

3. At least 40% of the units are occupied by tenants with income averaging no more than 60% of AMI, and no units are occupied by tenants with income greater than 80% of AMI

The Department of Housing and Urban Development annually calculates estimates of median family income for every area of the country, which are defined as percentages of median family income and vary by the number of persons in a household (AMI) (Novogradac, 2023).

LIHTC allocates approximately $8 billion in annual budget authority to State housing finance agencies (HFAs) with each state getting a fixed allocation of credits based on its population Developers submit applications which are then assessed against the QAP and awarded in a few "allocation rounds" held each year, on a competitive basis.

As directed by the IRS, the HFA’s credit allocation processes and rules are written under a plan called the Qualified Allocation Plan (QAP) from which applications are evaluated As detailed in IRC Section 42(m)(1)(B), the QAP means any plan:

1. which sets forth selection criteria to be used to determine housing priorities of the housing credit agency which are appropriate to local conditions,

2 which also gives preference in allocating housing credit dollar amounts among selected projects to

a. projects serving the lowest income tenants,

b. projects obligated to serve qualified tenants for the longest periods, and

c. projects which are located in qualified census tracts (as defined in subsection (d)(5)(B)(ii)) and the development of which contributes to a concerted community revitalization plan, and

3 which provides a procedure that the agency will follow in monitoring for noncompliance with the provisions of this section and in notifying the Internal Revenue Service of such noncompliance which such agency becomes aware of and in monitoring for noncompliance with habitability standards through regular site visits.

Section 42(m)(1)(C) dictates that selection criteria set forth in a QAP must include:

1. project location,

2. housing needs characteristics,

3. project characteristics, including whether the project includes the use of existing housing as part of a community revitalization plan,

4 sponsor characteristics,

5 tenant populations with special housing needs,

6. public housing waiting lists,

7. tenant populations of individuals with children,

8. projects intended for eventual tenant ownership,

9 the energy efficiency of the project, and

10 the historic nature of the project

While federal regulations incentivize development in high-poverty census tracts and areas according to Section 42(m)(1)(B), HFAs have wide discretion in creating its QAP and thus determining which projects to award credits. The selection criteria in Section 42(m)(1)(C) are simply criteria needed for applications HFAs can decide any preferences for each criteria and can also include additional criteria for developers to provide in their application

Internal Revenue Code Section 42 outlines some requirements for Qualified Allocation Plans, but they are generally stated in broad terms, which is typical for statutes. The specific interpretation of these requirements is largely delegated to individual state housing finance agencies. This approach is reasonable, given that the distribution of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) must account for varying housing markets and other relevant factors that differ from state to state

The federal code requires state HFAs to notify local government executives of projects funded within their district, and to give them a reasonable opportunity to comment on the project. However, no further requirement is detailed Though the limited federal involvement in LIHTC distribution is suitable as compared to other federal statutes, a selection criteria on participatory planning methods (no matter how lean or robust) would definitively shift the way governments and developers think about the impact of their work. Real estate development particularly for low-income populations is a critical and sensitive endeavor that impacts and should involve community members.

To paint a clearer picture of the relationship between the federal government, states, and the developer, view the diagram to the left The flow of credits moves from the federal government to the state’s housing finance agency (HFA) and then awarded to developers who may then transfer credits to partner investors looking to reduce their tax liability (Preferred Compliance)

When looking at sources of regulation (following page), the developer has to follow two main sources of direction.

The first source delegates how projects are assessed and how tax credits are awarded This is the state housing finance agency’s Qualified Allocation Plan (QAP) which also includes the basic requirements and thresholds as directed in the federal tax code.

Just as important as the QAP is the second source of regulation, local planning and zoning code.

When navigating affordable housing real estate development, the state HFA’s Qualified Allocation Plan (QAP) is the most important document for developers to familiarize themselves with in order to appropriately put together a LIHTC application, competitively obtain a tax credit award, and maintain the award through a post-development compliance period. As was intended by Congress, states vary in the depth and scope of their QAP. IRC Section 42 is purposely broad with the goal of introducing a flexible instrument that could be utilized and catered to diverse housing markets across the country (Novogradac, 2022)

Due to significant housing needs and limited resources, some QAPs prioritize housing opportunities for extremely low-income households, the homeless, the physically and mentally challenged, people with HIV/AIDS, and other severely challenged households.

HFAs leverage the adaptability of the LIHTC program through their QAPs to address the unique conditions and needs of the state Though the goal of the program is to meet the needs of low-income communities, there is little reference to a requirement or need for public input in QAPs However, there are development criteria in every QAP alluding to opportunities for community input. This is the case for the QAPs of all 50 states reviewed with the exception of Ohio Housing Finance Agency which can serve as a leading example for clear and direct engagement requirements at the state level.

The bulk of every QAP speaks to (1) minimum threshold requirements that every project must meet in order to be considered for tax credits and (2) scoring criteria designed by the HFA used to rank projects against each other for the allocation of tax credits. Looking closer at how these criteria manifest in QAPs helps illustrate how states express their priorities and their relationships with community impact and input.

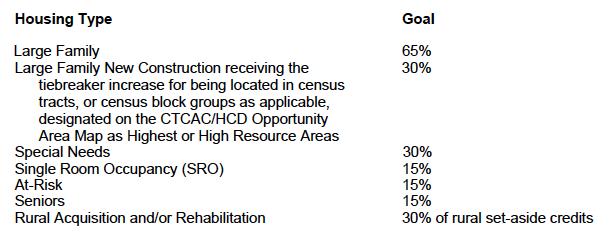

Being the most populous state with over 39 million residents as of 2022, California receives the largest allocation of federal tax credits. The estimated number of tax credits allocated to California in 2023 is $107,904,049 (Novogradac, 2023). The California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (CTCAC) is the state’s housing finance agency and controls how credits are awarded CTCAC allocates credits and categorizes applications into 7 different “Housing types” (CTCAC, 2023):

As detailed in the agency’s 2023 regulations, applications must meet minimum threshold requirements such as demonstrated housing need, site control, financing commitment, local approvals, minimum construction standards, and more As it directly or indirectly relates to public input, under Section 10325(f) “Basic Thresholds”, the request for demonstration of housing need and local approvals are detailed below:

1 Housing need and demand. Applicants shall provide evidence that the type of housing proposed, including proposed rent levels, is needed and affordable to the targeted population within the community in which it is located Evidence shall be conclusive and include the most recent documentation available (prepared within one year of the application date). Evidence of housing need and demand shall include, but is not limited to:

(A) evidence of public housing waiting lists by bedroom size and tenant type, if available, from the local housing authority; and

(B) a market study as described in Section 10322(h)(10) of these regulations, which provides evidence that the items set forth in Section 10325(f)(1)(B) have been met for the proposed tax-exempt bond project.

…

4 Local approvals and Zoning. Applicants shall provide evidence, at the time the application is filed, that the project as proposed is zoned for the intended use and has obtained all applicable local land use approvals which allow the discretion of local elected officials to be applied, except that an appeal period may run 30 days beyond that application due date. Examples of such approvals include, but are not limited to, general plan amendments, rezonings, and conditional use permits. Notwithstanding the first sentence of this subsection, local land use approvals not required to be obtained at the time of application include, design review, initial environmental study assessments, variances, and development agreements The evidence must describe the local approval process, the applicable approvals, and whether each required approval is “by right,” ministerial, or discretionary. When the appeal period, if any, is concluded, the applicant must provide

proof that either no appeals were filed, or that any appeals filed during that time period were resolved within that 30-day period and the project is ready to proceed.

Some “Additional Threshold Requirements” include “play/recreational facilities suitable and available to all tenants, including children of all ages, except for small developments of 20 units or fewer” and an “appropriately sized common area” - both with square footage and equipment requirements.

CTCAC applications that meet the threshold requirements are then competitively scored against each other with points awarded based on a number of criteria, such as “General Partner/Management Characteristics”, “Site Amenities” like neighboring transit, parks, supermarkets, schools, or other facilities. Additional points are given for green and sustainable building. As it pertains to residents’ well-being, points are given to “service amenities” or “projects that provide high-quality services designed to improve the quality of life for tenants” (Section 10325(f)(4)(B)) Some examples include:

1 Service Coordinator Responsibilities must include, but are not limited to: (a) providing tenants with information about available services in the community, (b) assisting tenants to access services through referral and advocacy, and (c) organizing community-building and/or other enrichment activities for tenants (such as holiday events, tenant council, etc )

3 Instructor-led adult educational, health and wellness, or skill building classes Includes, but is not limited to: Financial literacy, computer training, home-buyer education, GED classes, and resume building classes, ESL, nutrition class, exercise class, health information/awareness, art class, parenting class, on-site food cultivation and preparation classes, and smoking cessation classes

4 Health and wellness services and programs Such services and programs shall provide individualized support to tenants (not group classes) and need not be provided by licensed individuals or organizations. Includes, but is not limited to visiting nurses programs, intergenerational visiting programs, or senior companion programs.

Other examples include licensed child care, after school programs, case managers for special needs projects (such as those with units dedicated to formerly homeless populations or developmentally disabled populations), adult education, and more Documentation such as a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) or commitment letter must be provided as proof in the LIHTC application.

Moreover, points are designated for developments in revitalization areas:

Revitalization Area Project. The project is located within one of the following: a Qualified Census Tract (QCT), a census tract in which at least 50% of the households have an

income of less than 60% of the area median income, or a federal Promise Zone. Additionally, the development must contribute to a concerted community revitalization plan as demonstrated by a letter from a local government official The letter must delineate the various community revitalization efforts, funds committed or expended in the previous five years, and how the project would contribute to the community’s revitalization

This particular criteria provides a demonstration of local input outside of local zoning approvals. While local zoning is a threshold requirement needed for all applicants, alignment with Community Revitalization Plans adds points and creates leverage for the project application In this way, the QAP puts value on community voice, given that the Community Revitalization Plan is an appropriate representation of community input

In CTCAC’s QAP, the 2 points for “Revitalization Area Project” fall under the category of “Miscellaneous Federal and State Policies” which only allow a maximum of 2 points with a variety of ways to meet these points such as committing to a smoke-free residence This is a notable example of the ways in which individual state HFAs have the flexibility to apportion points as they see fit

As the 10th most populous state with over 10 million residents as of 2022, Michigan receives an estimated 2023 tax credit allocation of $26,132,108 The state’s housing finance agency is the Michigan State Housing Development Authority (MSHDA)

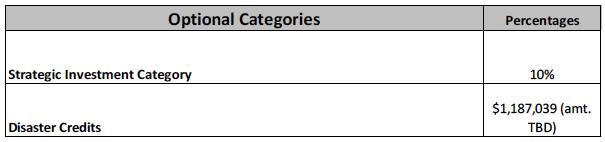

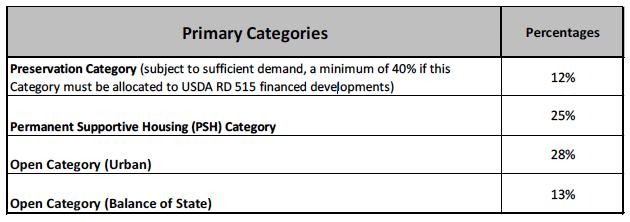

In contrast to CTCAC’s LIHTC development categories, MSHDA separates LIHTC funding priorities into four “Primary Categories”, as detailed in its 2022-2023 QAP: preservation, permanent supportive housing (PSH), open (urban) for areas that are neither preservation nor PSH, and open (balance of state) for all other areas On top of the primary category, projects may also fall under one or both of the two “Optional Categories”: strategic investment and disaster credits (MSHDA, 2023)

Similar to California’s QAP, MSHDA lists general threshold requirements including project narrative, site control, zoning, utilities, market study, environmental Opportunities for public engagement would be possible under zoning and market study requirements:

Evidence from the local governing body of the property’s current zoning designation and what, if any, steps are in process to obtain proper zoning for the proposed development, if it is not already properly zoned …

A market study completed in accordance with MSHDA’s guidelines that indicates the housing needs of low-income individuals in the area to be served A completed market study must be submitted with the application and dated within six months of the application deadline

Upon meeting the threshold requirements, applications are subject to selection criteria where points are designated based on how projects meet the key objectives of MSHDA’s QAP which are “designed with the intent of ensuring that affordable housing is available in areas of high opportunity” Key criteria include:

1. Proximity to Transportation

2. Proximity to Amenities

3. Developments near Downtowns/Corridors

4 Education, Health and Well-Being, and Economic Security

5 Community Revitalization Plan Areas

Under scoring criteria A, points are awarded for proximity to transportation, amenities, downtown locations, education, economic security measures, and more Similar to CTCAC’s QAP, points are also given for items like development team experience, sustainable building, and providing community space such as community rooms for exercise or socializing.

As it pertains to residents of the development, points are awarded for tenant services like job training, health care, child care, and health and wellness Permanent Supportive Housing developments qualify for additional points for services that benefit such residents - rehabilitation services, behavioral health services, and youth development initiatives In both instances, any resident services or supportive services require a narrative and a letter of intent from partner agencies.

Lastly, like CTCAC’s QAP, MSHDA’s focus on neighborhood revitalization is presented in Criteria

A 5 “Community Revitalization Plan Area” which awards projects that are aligned with local revitalization plans where applicable If applying for scores in this category, applicants must provide:

A signed letter or resolution from the local government dated within 60‐ days of the application due date that identifies, supports and outlines the significance of the proposed project, and includes:

If there is a Community Revitalization Plan for the area, the letter or Resolution must also

(1) identify the Community Revitalization Plan for the area, (2) provide a link to the plan if not included in the application, (3) outline the goals of the plan, (4) define the specific boundaries of the target area, and (5) describe how the proposed project compliments the plan goals

Unlike CTCAC’s QAP, MSHDA’s point allotment for alignment with community revitalization plans stands alone in its own category of points; there is no other way to receive the 2 points in this category. In this way, MSHDA puts greater emphasis on alignment with existing revitalization plans than CTCAC does, thus putting greater emphasis on previously-cataloged community input. Again, this highlights how states can apportion points as they see fit

As demonstrated in both California and Michigan’s LIHTC Qualified Allocation Plans, there are no requirements or criteria for public participation or community engagement. However, there are threshold requirements and additional criteria that may be indirectly tied to public input

Table 2: Criteria for Public Engagement

The five criteria outlined above may include opportunities or even requirements for local engagement. For example, local planning and zoning code may require some degree of public outreach whether it’s through a simple notice or through an in-depth workshop. Similarly, though uncommon, market studies may include community engagement as complimentary input to a market analysis combining quantitative data and qualitative findings (Main Street America, 2018). Project facilities and community spaces are a topic which neighbors and community members could provide input directly to developers if given the space, especially if such facilities like a green space are outward-facing. When developers partner with local agencies on resident services and supportive services, this partnership can conveniently serve as a segue to include their input on other aspects of the project. Local social service and nonprofit agencies often have the most direct experience working with low-income communities and have potential to serve as a community’s voice, with expert knowledge to speak for their experiences and needs. Lastly, Michigan’s point allotment for alignment with community revitalization plans is an indirect channel where public engagement likely took place in the formation of the plan, as is common with revitalization plans

While these five criteria may allude to community engagement, it is definitely not guaranteed The onus lies in local planning and zoning code, market research methods, and development practices In both Qualified Allocation Plans, neither California nor Michigan’s state housing finance agencies designate points for direct community engagement

Upon reviewing the QAPs of all 50 states, the following states have the most significant language suggestive of requirements for community engagement

State Language Relating to Community Engagement

Colorado Vague Threshold Requirement

“Narratives must provide a description of outreach to the community and how the Application contributes to promoting equity and economic mobility for residents ”

Connecticut Conditional Threshold Requirement

If development includes existing public housing residents, developers must have a “plan that ensures meaningful resident participation in the planning and implementation process ”

Delaware Conditional Point Allocation

If development includes fully ADA units, developers must have an “accessibility outreach and marketing agreement describing marketing and outreach efforts to the disability’s community.”

Georgia Conditional Point Allocation

If claiming points in the “Community Transformation” category, the developer must be "partnered with two or more established community organizations" or put together a board with representatives from the local community Development team must have a "Community Transformation Plan" detailing community engagement and outreach efforts

Illinois Conditional Threshold Requirement

If development is not receiving Green Building Standards certification, it must adhere to “EGC mandatory requirement

1.2 Charettes and Coordination Meetings. This criterion requires community-based

QAP Reference

2023-2024 QAP

3.B.4 Threshold Criteria for Preliminary Applications

Threshold #13 Narrative

2022-2023 QAP

III A 16 Public Housing Resident Participation

2023-2024 QAP

Scoring and Ranking

Tenant Populations Served. Additional Fully Accessible Units

2023 QAP

Scoring Criteria.

IX Community Transformation

2022-2023 QAP

VIII Project ApplicationMandatory Components

C Community Engagement

Table 3: QAPS with Language for Community Engagementinput on the proposed Project, asking Sponsors to appropriately collaborate on a vision in agreement with key stakeholders ”

Indiana Conditional Point Allocation

If development is setting aside units for individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities, developers must “seek input from persons with disabilities and provide a housing setting that assists in integrating persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities into the community”

Mississippi Direct Threshold Requirement

Developers must notify the public, including notice to local government and notice to the community Notice to the community requires newspaper publication and signage requirements at the property with information on development with contact information to submit public questions/comments

Montana Direct Point Allocation

Points are awarded for obtaining local community input through neighborhood meetings, local charrettes, City/County Commission meetings, or other forms of input. Developers must provide evidence of notice, attendees, and input

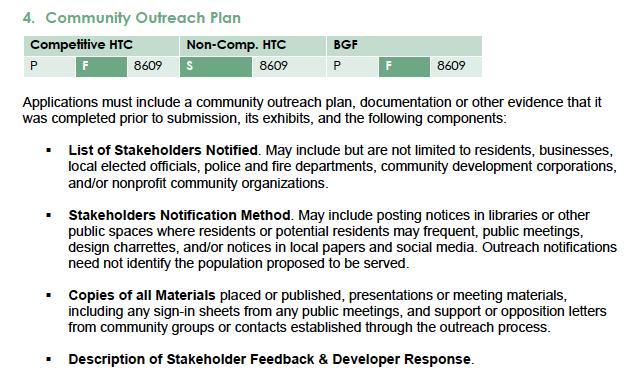

Ohio Direct Threshold Requirement

Developers must submit a “Community Outreach Plan” documenting stakeholders notified and outreach engaged with proof of meeting and input. Developers must describe stakeholder feedback and developer response. Stakeholders “ may include but are not limited to residents, businesses, local elected officials, police and fire departments, community development corporations, and/or nonprofit community organizations ” Methods of outreach

2023-2024 QAP

Section 4 Set-Aside Categories

Part 4.2 Community Integration

2023 QAP

Section 4 Threshold Factors

4 1 Community Notification

2022-2023 QAP

VII Development Evaluation Criteria and Selection

A Development Evaluation Criteria

4. Housing Needs Characteristics

II. HTC Requirements

A Document Submission Requirements

4 Community Outreach Plan

include “public meetings, design charrettes, notices in local papers and social media.”

Rhode Island Direct Point Allocation Points provided for developers who complete “public engagement process that includes community meetings and community input beyond those held for the locally mandated approval process (must be documented).”

2023 QAP

III. LIHTC Review Critieria

B Scoring

Comprehensive Community Development Engagement and Services

As demonstrated in the above table, Colorado has a vague requirement for developers to describe outreach in their narrative. It may be suggestive of engagement requirements but is ultimately up to interpretation. Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, and Indiana all have requirements or points associated with community engagement only for certain conditionssuch as if units are set aside for disabled communities None of these communicate a sense of need for engagement in all affordable housing development projects

In contrast, Montana and Rhode Island have point allotments for local engagement efforts with requirements to show proof of such efforts if points are to be awarded However, community engagement only counts for 30 out of over 1,000 possible points in Montana’s QAP, and 1 out of 138 points possible in Rhode Island’s QAP While developers are encouraged to bring in public input, the associated points awarded are minimal At the end of the day, even for these two states, engagement is not required

Out of the 50 QAPs reviewed, only Mississippi and Ohio have a clear and direct threshold requirement for community engagement. Mississippi requires a newspaper publication and signage. While site signage with development information and contact information is standard for developers, a newspaper publication may open up opportunities for additional input. Despite this, minimal effort is needed for this requirement and it surely does not guarantee that community members will view the publication and provide input to the developer.

At the furthest end of the spectrum is Ohio which requires developers to submit a community outreach plan describing engagement methods, feedback, and results. It calls for input from a range of possible stakeholders and requires proof of outreach with the public’s input.

Described in Ohio Housing Finance Agency’s 2022-2023 QAP, under “Document Submission Requirements”, Ohio requires a “Community Outreach Plan”: THE POLICY

Among the 50 QAPs reviewed, only 10 have some mention of community engagement Six of these 10 are vague in their language or speak of engagement only in certain scenarios that are not applicable to all projects Two of the 10 have points allotted to engagement and one includes a weak requirement for engagement Among the 50 QAPs reviewed, only Ohio’s HFA requires community engagement for all projects in a manner that encourages developers to gather public input beyond the real estate development norm.

An effective Qualified Allocation Plan (QAP) can address various criteria and incentivize the production and preservation of rental housing that caters to the diverse needs of the state (National Housing Conference, 2017). Although the primary objective is to create or preserve affordable housing, an effective QAP should take a holistic approach by considering how housing intersects with the community, including retail, commercial, and office uses, as well as transportation systems such as roads and transit (Texas Housers, 2022)

Beyond the number of affordable units, other considerations must be included - considerations that would benefit from community input For example, a mixed-income housing development that includes market-rate housing may offer residents better access to schools, services, and opportunities. Similarly, housing for older adults should consider the benefits of mixed-age communities rather than exclusive housing for seniors. In addition to housing construction and energy efficiency, serious environmental concerns arise due to housing location and proximity to other uses The most holistic QAPs consider factors like these to greater detail, but they still lack

community input as a necessary criteria to justify the urgency and specific designs of these factors.

A QAP should promote diversity and avoid further segregation of rich and poor, old and young, and explore synergies that could be created by encouraging a variety of housing types The QAP is an essential tool for building healthy communities, and its implications for the broader community should be kept in mind during its crafting

Becoming involved in the Qualified Allocation Plan (QAP) process is a way to advocate for changes to the LIHTC program in one’s state Every state agency must review their QAP annually The reviews must be properly noticed and include a public hearing with opportunities for public comment (26 U S Code 42, 1986)

For example, in Michigan, MSHDA holds annual information hearings to take comments and suggestions for modifications to the QAP In addition to recommendations in these meetings, public comments are also submitted virtually to MSHDA In 2023 alone, letters from 10 different agencies have been published on MSHDA’s website (MSHDA, 2023) These agencies include developers like Community Housing Network and TRIBE Development, and local organizations like Michigan Promise Zone Association and Michigan Rural Development Council. Suggestions include changing the financing structure to adjustment of points for proximity to amenities to inclusion of an incentive for projects close to Michigan’s Education Promise Zones.

MSHDA has also taken the initiatives to implement Racial Equity Impact Assessments, which are “systematic examinations of how different racial and ethnic groups will likely be affected by a proposed action or decision” (MSHDA, 2022). The goal is to reduce and prevent inequities and unanticipated adverse consequences to communities.

State HFAs have annual opportunities for public comment and sometimes administers additional chances for public input like MSHDA’s Racial Equity Impact Assessment. Still, In practice, most input is provided by developers and advocate organizations rather than local community members or low-income residents (Texas Housers, 2022). While the complexities of the LIHTC program and engaging with local government processes can be tedious, time-consuming, and confusing for individuals who do not work in related occupations, developers and affordable housing partners and advocates should reflect on how to build equitable affordable housing development through the improvement of state QAPs.

To prioritize equitable, community-driven development, Qualified Allocation Plans should dictate community engagement requirements or at least encourage point allotment for engagement efforts. Provided that there is an annual public comment period for QAPs, suggestions to include engagement criteria could push state housing finance agencies to

address the significance of community voice in real estate development for low-income families These comments can come from any individual, but developers, architects, local nonprofit agencies, and advocate associations would have more appropriate resources to understand the LIHTC program and navigate a coherent response to its state HFA

Community engagement is crucial for equitable and sustainable affordable housing development Unfortunately, there are few federal or state requirements for community engagement in affordable housing. Among the 50 states, Ohio’s HFA is the only one that truly requires engagement for all LIHTC projects beyond the standard practices.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing as real estate development is a complex and contextual process What works well in one community may not work in another, and what is feasible in one location may not be feasible in another As such, it is difficult to create blanket regulations for community engagement in affordable housing development. While some state HFAs have some language and recommendations for community engagement, there are few legal requirements. Rather than being forced into a one-size-fits-all approach, this flexibility allows developers and communities to undergo the development process in a manner that works best for their timeline, costs, and context

However, just because community engagement is not required does not mean it should be ignored. In fact, community engagement can be one of the most important factors in the success of affordable housing development. Engaging with the community can help developers understand the unique needs and preferences of the community, which can lead to more innovative and effective solutions and designs

Additionally, community engagement builds trust and understanding between developers and community members, smoothing the development process and reducing conflicts down the road. When the community is involved in the development process, they are more likely to feel invested in the project and proud of the final product This can lead to greater community support for affordable housing development, which can in turn help reduce NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) opposition and speed up the development process

While the lack of regulation is not necessarily a bad thing, it does mean that community engagement often takes a backseat in the design of housing. However, community input should be championed as a way to increase public support of affordable housing while also pushing the boundaries of housing design In this way, an affordable housing project becomes more than just real estate; it becomes a symbol of community inclusion, ownership, and pride

Developers, architects, and advocates of affordable housing can ask for changes in QAP regulations to encourage requirements for community participation in the development process, but ultimately, the most impactful engagement practices will come from the priorities and agency of developers and architects in every project

The Developer’s Agency for Community Engagement

Michael Pyatok, architect and activist known for his participatory design approach, states that the best architects and planners embrace public input and the notion that “community design is an intense cultural enterprise that should be transparent and inclusive” (Schmitz, 2005) Having designed over 50,000 units of housing, Michael’s design methodology entails active collaboration with clients, users, and community members. From his perspective, local populations need to be treated as partners in a project to mitigate cumulative resistance against development and move the dial towards a social setting where quality, beneficial developments are supported by its community

Though federal, state, and local requirements for engagement may be sparse and varied, some developers and architects like Pyatok Architecture + Urban Design have participatory methods integrated into their practice. In the San Francisco Bay Area, it is common for affordable housing development teams to host at least one to two community meetings at minimum. While a lot less common, there are also projects that allow for more intensive engagement with design workshops or “charrettes ”

Since the needs and timelines of every project are different, it is up to the development team to take agency and initiative in public engagement to the degree to which circumstances allow This requires the intentional prioritization of community input in development processes while also continually laying the groundwork for equitable community design in future projects.

In this section, I will be summarizing the presence, impact, and methods of engagement derived from personal interviews with 36 individuals representing 27 organizations This includes 9 real estate development firms, 5 architecture and design firms, 6 government agencies, 2 community development finance institutions, and 3 universities. All individuals were interviewed for 30-45 minutes over a virtual meeting with a loose outline of questions that can be viewed in Appendix A.

It should be noted that I was intentional in reaching out to developers and architects who have more experience in community engagement With the goal of capturing the nature of engagement in affordable housing development, the findings and takeaways outlined here are mainly

6 Washtenaw County Office of Community & Economic Development (OCED)

Community Development Finance Institutions

1 Invest Detroit

2 Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC)

Other Organizations

1 CoUrbanize

2 Non-Profit Housing Association of Northern California (NPH)

Academic Professionals

1 Ceara O’Leary Professor of Practice of Architecture

2 Christina Bollo Assistant Professor

3 Kit McCullough Lecturer in Architecture

4 Lan Deng Professor of Urban and Regional Planning

5 Margaret Dewar Professor Emerita

6 Robert Goodspeed Associate Professor of Urban and Regional Planning

University of Detroit Mercy

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

To observe what community engagement practices can look like, I attended a handful of meetings virtually and in person

Virtual live

January 25, 2023

In-Person

February 16, 2023

In-Person

March 14, 2023

Virtual live

March 20, 2023

“Joint City Council/ Planning Commission Workshop”

“Resident Participation Meeting”

NeighborUp Meeting“Healing Circle”

“1939 Advisory Committee Meeting”

Riverhouse Hotel

Martinez, California

900 Briarwood Circle

Briarwood Mall

Ann Arbor, Michigan

290 Malosi, Sunnydale, San Francisco, California

1939 Market Street

San Francisco, California

Eden Housing, City of Martinez

Simon Property Group, Hines

Mercy Housing

Mercy Housing

Within the world of real estate development, it is widely accepted that community engagement often takes a backseat to traditional priorities. According to interviewees, the standard practice, especially in real estate development as a whole, is to only do what’s mandatory and enforced by local planning and zoning code

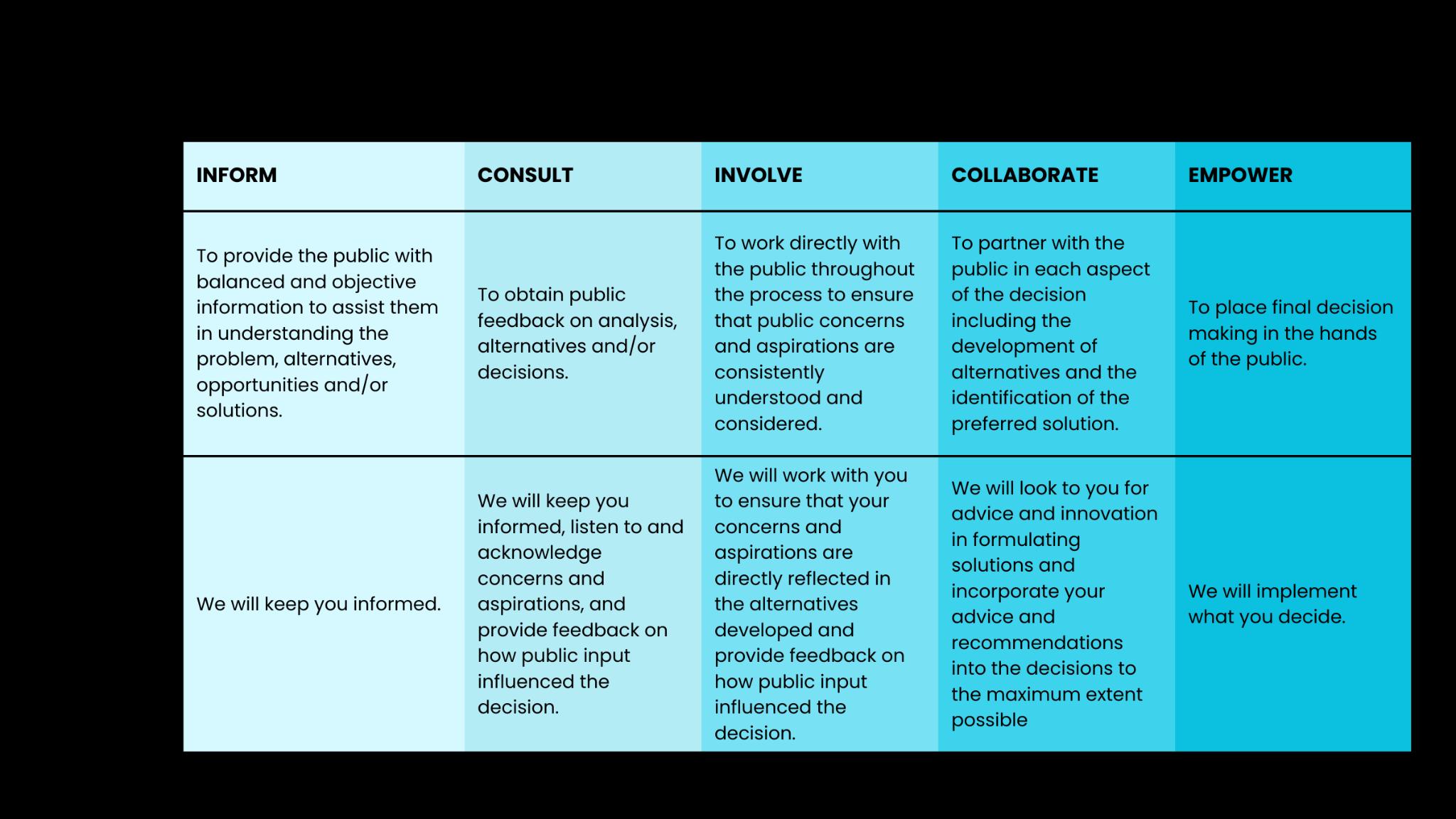

The interview findings suggest that community engagement requirements for affordable housing development vary depending on the location and project. The most common local requirement is to send an informational notice or mailer to residents within a certain radius of the development. Cities may also specify the number of meetings needed, one or two being the most common if any at all These meetings are generally only informational meetings by nature with little room for an exchange of information between developers and the public

In certain circumstances, there may be a requirement for consultation with neighborhood associations or local organizations. In the City of Detroit, the Community Benefits Ordinance requires developers to proactively collaborate with the community if the development is over $75 million in value or receives over $1 million or more in property tax abatement or city land value (City of Detroit) Overall, outside of more progressive areas like the Bay Area or in places that have actively worked to prevent harmful development like Detroit, community engagement is only seen as something to check off a box rather than an opportunity to build a relationship or design with public collaboration.

In California, there is actually a shift that has reduced public participation efforts through fast-tracking the entitlement process California Senate Bill 35 is a statute streamlining housing construction to meet the high demand for affordable housing. This bill reduces local engagement requirements and moves projects along the entitlement projects at a quicker rate. Despite this, some developers still choose to bring community voice into a development. Within affordable

housing development, there will almost always be at least one community meeting even if there are no requirements for engagement.

Regardless of local planning and zoning code, those who prioritize public input are intentional in doing engagement beyond the bare minimum because they have learned that the value of community voice not only outweighs the cost and time to engage communities, it has significant potential to translate into cost and time savings. Moreover, engagement builds local trust and ensures positive outcomes.

Interviewees shared that in contrast to most market-rate developers, affordable housing developers tend to be more responsive to the community’s needs and opinions In many ways, developers who prioritize community voice are also those who reimagine what the relationship between developers and the residents for which its development impacts can look like. These developers combat the narrative of villainous developers and victimized residents. It just so happens that affordable housing developers are the ones doing this work, whether it’s because they are more impact-driven or because they need to be sensitive to the stigmas and misconceptions of “affordable housing” and be careful to not perpetuate it (Badger, 2019)

There are few developer organizations like Mercy Housing who have a full-time Director of Community Engagement and architecture firms like FORA whose “ process starts with people, prioritizing keen listening and meaningful community, client, and civic engagement ” This regard for community voice is more commonly seen among affordable housing real estate developers, particularly in politically progressive areas

Ultimately, the level of engagement taking place varies. Some of the most important indicators for the presence of community engagement are:

1 Ethos, practice, and belief: Different developer organizations and architecture firms have varying levels of community engagement integrated into their practice Many value community input, but have not built out a framework around engagement processes.

2. Project timeline: Funding deadlines and short development timelines can prevent adequate engagement from occurring This is also why starting early in the process is important, prior to having all the funding awarded and in line The most in-depth forms of engagement are where developers approach the community prior to even having a drawing to invite them into the early conceptual stages.

3. Local requirements and/or political need:Local zoning and planning code may require some level of community engagement that developers need to follow However, some contexts demonstrate the political need for engagement due to public opposition that can lead to delays in the entitlement process, stall a project for years, or even kill a project in

its entirety. In these contexts, efforts to understand the community and build a relationship with stakeholders are vital.

4 Costs and resources: It is common to think about the costs of engagement efforts without weighing it against the long-term benefits (as detailed in the previous page) While the most thorough engagement practices can add anywhere from 10-20% on top of architectural fees in a model that accounts for 10 meetings or workshops, the leanest event can cost as little as $500.

Even for firms that wish to practice greater engagement strategies, the frequency and depth of engagement is often contingent on the timeline of the project It may be the case that funding requires construction to start soon which can make effective, in-depth engagement difficult to fit into a schedule. In this way, developers need to be very intentional in prioritizing engagement at the beginning of every project when they’re thinking about the long-term timeline of the project. Representatives of Mercy Housing and Eden Housing suggest that for the most comprehensive engagement, it is pertinent to start public outreach as soon as developers have a concept and before kicking off design development

Lastly, it is important to be mindful of the politics and context of the neighborhood. If citizens have previously hindered new development or have made the development process contentious and challenging, developers need to put an intensive engagement strategy together Similarly, if the neighborhood has endured histories of trauma or discrimination, collaboration between developers and residents can be seen as a necessity In these scenarios, multiple engagement opportunities from the very beginning of the project will be critical for the success of the project.

As Associate Professor at the University of Michigan Robert Goodspeed said best, the presence of community engagement is often “based on ethical need and political need ” While some developers and architects may be ethically called to integrate community design into the development of LIHTC housing, there are also more urgent political pressures to consider which can have a significant impact on the life of the project.

Prior to delving into the methods of effective community engagement, it is important to discuss the value of participatory design in practice These positive and lasting impacts can justify the extra time and cost of engagement efforts while also calling for increased integration of community input into developer and architecture firms’ ethos.

Regardless of the degree to which their organization practiced community design, all interviewees spoke of its value In order of societal to project-scaled impact, community engagement is crucial in the design of affordable housing for several reasons:

1. Building trust and fostering collaboration: Engaging with the community builds trust and fosters collaboration between the development team, local government, and the community. As voiced by a developer at Eden Housing, engagement leads to community members feeling a sense of ownership and pride in the project This in turn makes it more likely that the community will support the project and future developments over the long term Community engagement done the right way acts as a force for activism that changes the relationship between real estate developers and community members into one that values collaboration

2. Educating the public about affordable housing: A lot of resistance comes from a place of fear and misunderstanding. Meeting with community members provides a place to build collective understanding in what affordable housing is, how the LIHTC program works, who the development will service, and how these future residents are critical members of the community A representative from Mercy Housing shared that she seldom runs into people who are truly prejudiced or bigoted. “It’s usually because they’re scared.” Education can help bridge these fears while also building support.

3 Addressing concerns and overcoming resistance: Involving the community in the design process allows the designer to identify and address concerns and overcome resistance to the project This can help prevent delays, conflicts, and legal challenges that can arise from community opposition. Pyatok says that “although speed and efficiency are critical to housing production, avoiding the collective design process will only delay production in the long run.”

4 Ensuring that the design meets the community's needs and enhances social and environmental sustainability: Community engagement provides an opportunity for community members to have a say in the design process, allowing them to express their

needs, concerns, and preferences. This ensures that the housing design responds to the specific needs of the community it serves, rather than entailing a prescriptive top-down or one-size-fits-all approach This also increases social and environmental sustainability by identifying and incorporating suggestions that promote social cohesion, safety, and well-being, as well as environmental sustainability in respect to an area’s culture, setting, and climate.

Of the developers and architects interviewed, there are a number of projects where community input changed the final design of the project In one of MidPen Housing’s developments, the community helped design which corner of the site the development would be built on and where the entrance would be In another example, the developer decided against designing the project for homeless veterans because the community brought to light the lack of local services for this population. Instead, they shifted to a development for low-income families.

While this project focuses on engagement in the predevelopment phases, community input is also valuable post-construction once tenants have settled in Some developers like Mercy Housing and architects like FORA send out post-occupancy surveys to assess resident well-being and gather input on service offerings and design recommendations, like cabinet arrangements and elevator placement, which are taken into consideration for future developments.

The impact potential of community input and design is best represented in the following case studies: Mitchell Park by Eden Housing, La Joya Gardens by Cinnaire Solutions, and 290 Malosi by Mercy Housing

Case Study: Mitchell Park Place in Palo Alto, California

525 East Charleston

Developer: Eden Housing

Architects: Architects FORA

Located at 525 East Charleston Road near Mitchell Park in Palo Alto, California, Mitchell Park Place is a new mixed-use development that will contribute to the vibrant neighborhood around Mitchell Park with a new office space for public social services as well as 50 units of high-quality affordable housing for lower-income households, including special needs housing for the intellectually and developmentally disabled (IDD) community

Eden Housing and Architects FORA will be building a 2,750-square-foot office space and 50 rental apartments for individuals and households earning at or below 80% of the area median income.

“You

During a set of snowball interviews, the development team was advised to not underestimate the Palo Alto community because they had halted a project in the past. While FORA architects has a practice ingrained in community engagement and Eden Housing values opportunities for engagement, they made sure to take this comment to heart throughout their design process.

Situated on the site is one of the offices of AbilityPath, a nonprofit supporting children and adults with disabilities The building will be demolished to make way for a 50-unit apartment building

Figure 4: Rendering 1 (Architects FORA)with AbilityPath’s presence on the ground floor. The project will not only be serving low-income households, Mitchell Park Place also has a focus to serve the intellectual and developmental disabled (IDD) community Since the very beginning of the project, the development team worked closely with AbilityPath to ensure appropriate input from this special needs community (Simitian, 2023) Once the project is complete, AbilityPath will also be providing on-site programming and supportive services to IDD residents of Mitchell Park Place.

With AbilityPath as a partner, Developer Eden Housing and Architects FORA started engagement in the concept phase and continued gathering input throughout the pre-development phase The breadth and depth of their engagement includes:

● 20 + snowball interviews with neighbors and community members at the earliest stages of the project. Because the project includes special needs housing for the intellectually and developmentally disabled (IDD) community, Santa Clara County provided contacts for organizations serving this community

● Mailers to residents within a 500-600 feet radius

● Setting up a website with project and contact information

● Focus group interviews with individuals, parents, and advocates of the IDD community.

● 3 intensive design workshops held virtually over Zoom and facilitated through Miro, an online whiteboard (conducted in the summer of 2021). Each workshop lasted approximately one and a half to two hours with an average attendance of 30 individuals, including members of the development team The first workshop was a community needs assessment, the second workshop facilitated a design charrette with focus on takeaways from the first workshop, and the third summarized the goals and results of the first two workshops while showing the final proposed design.

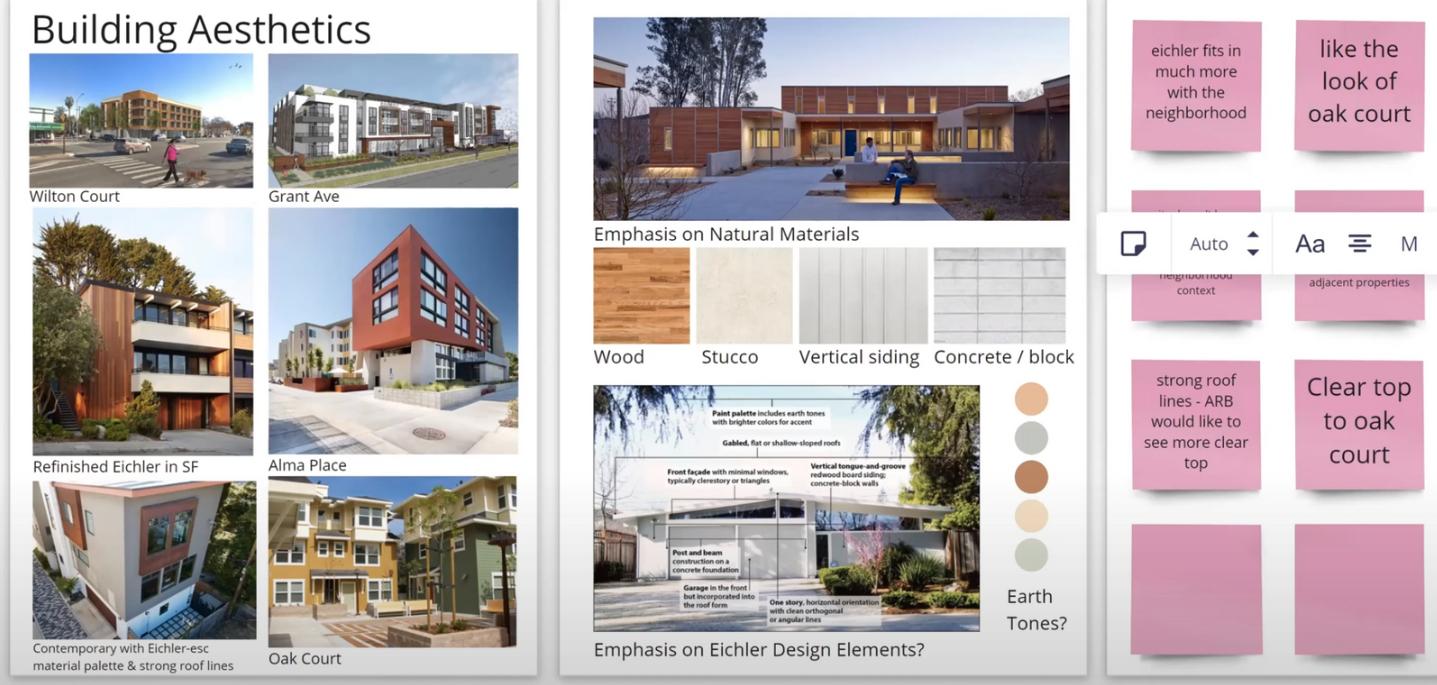

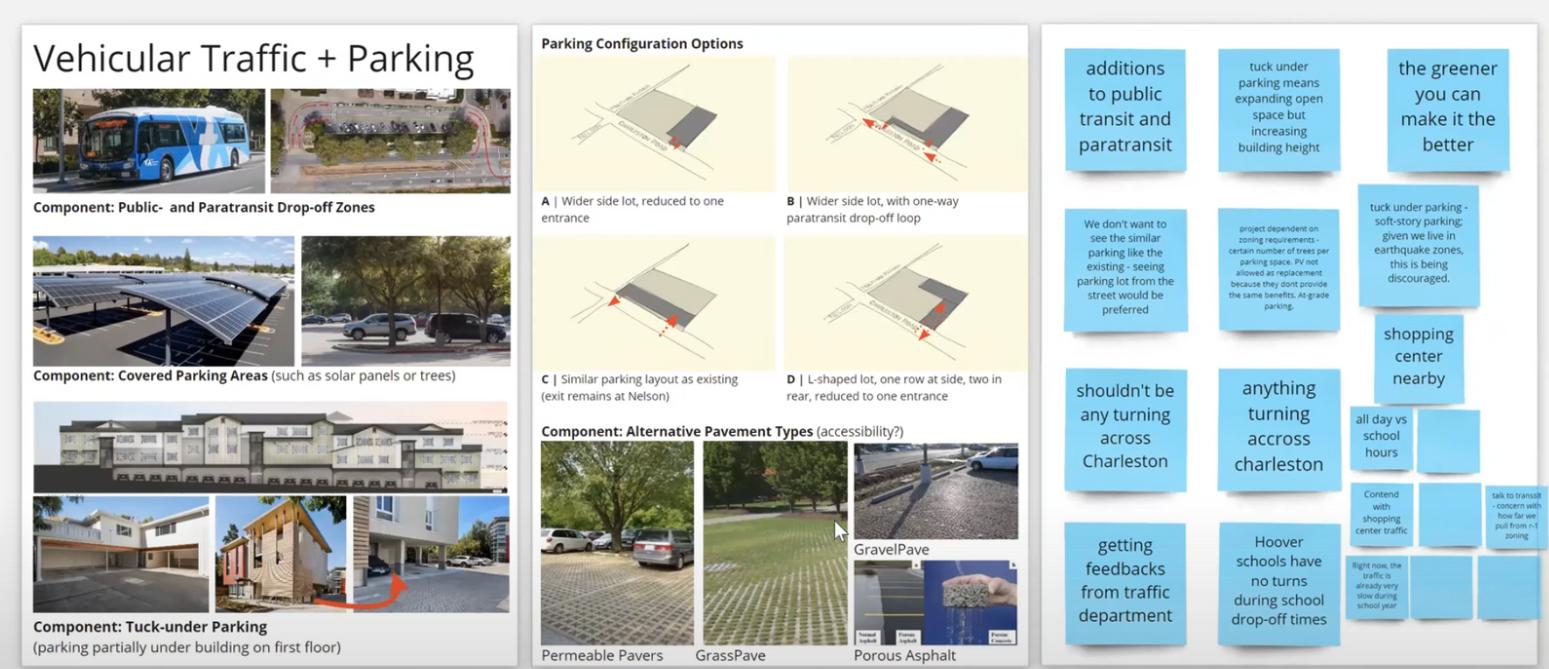

The outreach and interviews conducted provided the necessary social context for the development team to set up the design workshops and ensure that appropriate representatives of the community were present In the design workshops, attendees were able to provide input on 8 “Design Topics” including:

● Bike Traffic & Safety

● Vehicular Traffic & Parking

● Street Trees & Site Trees

● Gardening on Site

● Building Aesthetics

● Building Height + Massing

● Neighbor Privacy

● Resident Safety

Community input changed the design direction in several ways Some of the most significant impacts include:

● Finalizing on a mid-century style to honor the historic design of the surrounding neighborhood. This architectural design choice would not have happened without community input. Attendees suggested for the development team to find inspiration from the Eichler Design Guidelines This impacted a number of aesthetic choices including the saw-tooth edge, low-sloping roof, clerestory windows, vertical siding, and other details (Nelson, 2022, Sheyner, 2021)

Figure 6: Workshop 2 - Building Aesthetics (Eden Housing, Architects FORA)

Figure 6: Workshop 2 - Building Aesthetics (Eden Housing, Architects FORA)

● Driveway placement to prevent interference with bike lanes and the path to school that both adults and children use on a daily basis. A number of attendees spoke to the use experience of the sidewalks and bike paths adjacent to the development

● Planting and placement of trees to provide a subtle mask of the building from the street view

While the County requested robust engagement on this County-owned site, Eden Housing and Architects FORA “went beyond expectations”, according to the City of Palo Alto The development team was intentional in conducting outreach throughout the concept and design phases The city lauds the team for going through many design iterations that they weren’t obliged to do It resulted in positive feedback from neighbors. “Here’s a developer interested in responding to our concerns,” as expressed by a representative at the City heard from several residents that participated in the engagement process

Figure 7: Rendering 2 (Architects FORA)

A representative at Eden Housing shared that the level of community engagement work on Mitchell Park Place was the best she’d ever seen during her time working in affordable housing real estate development.

Figure 7: Rendering 2 (Architects FORA)

A representative at Eden Housing shared that the level of community engagement work on Mitchell Park Place was the best she’d ever seen during her time working in affordable housing real estate development.

The affordable housing project started demolition in February of 2023 and is expected to finish construction in 2023

"Building and developing housing must be intentional, delivering what the community needs, and I am very proud of our investment of $3 million to move this important affordable housing project forward," says Palo Alto Mayor Lydia Kou (Palo Alto Weekly, 2023)

Figure 8: Rendering 3 (Architects FORA)

Figure 8: Rendering 3 (Architects FORA)

Case Study: La Joya Gardens in Detroit, Michigan

4060 W. Vernor Hwy.

Developers: Cinnaire Solutions, Southwest Detroit Business Association

Architects: SITIO Architecture + Urbanism, 511 Design

Located in Detroit’s Southwest neighborhood in Michigan, the La Joya Gardens mixed-use development brings urban vitality to a longstanding vacant block along a Main Street corridor that connects to the Michigan Central Station, future home of Ford’s Corktown Campus (SITIO)

Cinnaire Solutions and SITIO Architecture + Urbanism have designed a 53-unit building providing a combination of market-rate and affordable rental apartments, community amenities, and retail. Surrounding these vibrant spaces is a lush landscaped plaza, connected by a community pavilion, that provides a welcoming location for social gathering and events. The project brings essential density into the community, integrating modern design within the existing context through varied massing and scale considerations

This project is unique in that it is made possible by a $1.5 million investment from Invest Detroit, a mission-driven lender and investor. As part of the Strategic Neighborhood Fund, Invest Detroit works in partnerships with corporate and philanthropic donors, the City of Detroit, and its neighborhoods to invest in “commercial corridor revitalization, catalytic park investment, streetscape improvements, and housing stabilization” depending on the needs of each neighborhood (Hyde, 2021) The Fund is focused on community-driven projects and requires all of its investments to include community input to some degree (Branche & Wileden, 2020). They even have community engagement grants for developers to establish themselves in the neighborhood, apply equitable and restorative practices, and build relationships with local organizations and

Figure 10: Rendering 1 (SITIO Architecture + Urbanism)residents. These grants, up to $25,000, can be especially helpful for smaller developers or those who are unfamiliar with engagement methods and the cost associated with such efforts.

La Joya Gardens was a partnership between Invest Detroit and Southwest Detroit Business Association (SDBA), a place-based community development organization in Southwest Detroit SDBA brought in Cinnaire Solutions as an experienced developer to lead the project. On the architectural side, Philadelphia-based SITIO Architecture + Urbanism led the design with 511 Design as a local partner whose architecture practice highly values the human-centered design thinking process (511 Design) 511 Design was particularly important in executing some of the door to door canvassing that was completed

Shared by representatives at Cinnaire Solutions, community input was not only required by Invest Detroit in the development of La Joya Gardens, it was particularly important in the context of the diverse and historic neighborhood.

Similar to Mitchell Park Place, community engagement occurred early in the development process even prior to any design being drawn up To start with, the team showed up to the neighborhood and just had a conversation with the community. Throughout the engagement period between September 2018 and January 2019, the project’s partners used a variety of outreach methods (Cinnaire Solutions, 2020), including:

● Mailers within a 300-feet radius to engage property and homeowners who live nearby

● Online survey sent out to community members and organizations with the option for in-person engagement through door-to-door canvassing which was organized by 511 Design

● 4 affinity group meetings with local organizations

● 4 in-person “community participatory design meetings” with childcare and food with a Spanish translator available at every meeting (with translation equipment)

● 2 meetings with the Hubbarb Farms Neighborhood Association

● Project naming competition

Figure 11: Community Participatory Design Meetings (Cinnaire Solutions)

Demographics from the community meetings and door-to-door canvassing were collected and shared online (Cinnaire Solutions, 2020):

● 91% of those surveyed (200 surveys completed) live in the project impact area

● Almost half (46%) of those surveyed have lived in the area for more than 7 years

● Most participants (28%) are in their 30’s.

● More than half (54%) are female

● 39% are Hispanic / Latino and 35% are African American

● 46% own their home versus 54% who rent

Cinnaire Solutions shared that throughout the process, they aimed to be as transparent as possible because “transparency is key” for building trust. They made sure to focus on asking for feedback that would actually be considered. The project team talked about what was possible for the development to make the budget work “People appreciate honesty and being in the know”

Community engagement influenced the project design in several ways, with the most impactful being:

● Design of the central event/community space or the “jewel piece” . After narrowing down 15 massing options, the top three were voted on by the community and resulted in the massing selection of a linear court option This was further refined with community input Originally, the linear court was designed to feature an open green space, but one resident

Figure 12: Rendering 2 (SITIO Architecture + Urbanism)

Figure 12: Rendering 2 (SITIO Architecture + Urbanism)

pointed out that it was too much open space considering Clark Park was just around the corner. This led the development team to reimagine the space into the event/community space that is now the “jewel piece”, as described by a representative from Cinnaire Solutions

● In response to the desire for opportunities for residents and neighbors to gather, the design also features street-front retail spaces on adjacent sides of the building. Community members voiced that a coffee shop would be particularly attractive to serve as a community-gathering space.

● Brick facade and vibrant colors were selected to reflect the historic nature and cultural heritage of the neighborhood

● The community also impacted building height and setbacks with a staggered design for better integration with the existing buildings surrounding the project site. This also provides a more intimate and human scale as one walks along the sidewalk of the building.

● Naming the building “La Joya Gardens” In Spanish, “la joya” means “the jewel ”

La Joya Gardens started construction in March of 2023.

At the groundbreaking event, Mayor Mike Duggan voiced, “In neighborhoods across Detroit, the Strategic Neighborhood Fund is helping us build new affordable housing and bringing new life to our historic commercial corridors like West Vernor.” The location of La Joya Gardens has been left vacant for over a decade in an otherwise thriving commercial district in the heart of Hubbarb Farms (City of Detroit, 2023) Many are looking forward to the La Joya Gardens development as a

Figure 13: Rendering 3 (SITIO Architecture + Urbanism)way to bolster equitable development through affordable housing and adding commercial corridors to the neighborhood.

Julie Schneider, director of The CIty of Detroit’s Housing & Revitalization Department, said “The deep affordability La Joya will bring is also essential in our efforts to build back neighborhoods everyone can afford to call home.”

Case Study: 290 Malosi in San Francisco, California

290 Malosi, Sunnydale

Developers: Mercy Housing, The Related Companies

Architect: Levy Design Partners (LDP) Architecture

Completed in 2022, 290 Malosi was co-developed by Mercy Housing and The Related Companies as part of San Francisco’s Sunnydale HOPE SF partnership, a community-led initiative designed to create vibrant, well-supported neighborhoods while preventing the displacement of current residents The 167-unit affordable housing development boasts amenities including a community room, secure podium-level courtyard with barbecue area, community laundry rooms, onsite parking for 78 vehicles, and bicycle storage for 167 bicycles.

In this partnership with Related, Mercy Housing is developing affordable housing in phases as part of the larger 50-acre Sunnydale HOPE Master Plan A large portion of this housing will replace distressed public housing properties originally built to house wartime ship builders Today, the 775 public housing units have deteriorated, are not compliant with building codes or ADA, and host conditions that pose health and safety risks to residents and visitors. Utility lines and infrastructure need to be replaced. This project will require the relocation of hundreds of residents (Mercy Housing, 2016).

When the full transformation for Sunnydale HOPE is complete, the larger site will consist of approximately 1,770 residential units (775 replacement affordable housing, 200 additional affordable housing units, and approximately 694 market-rate units) Residents and neighbors will be able to take advantage of new neighborhood infrastructure and amenities including “the Boys & Girls Clubs of San Francisco’s Sunnydale Clubhouse, a Wu Yee Children’s Services Early Learning Center, a recreation center operated by the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department, landscaped play areas, a welcoming courtyard, a café, and space for fitness and cooking classes, special events, and casual community gatherings” (Mercy Housing, 2023)

While the development team will be building safer and newer housing, they are cognizant of how demolishing and replacing homes can be stressful, especially for residents who have lived in them for decades. With this in mind, Mercy Housing has been paying acute attention to residents’ voices and needs. To keep residents up to date and to provide a channel for open feedback, Mercy hosts regular “NeighborUp” meetings with residents and neighbors in this Sunnydale project In the month of March 2023, they hosted four healing circles

Figure 15: Original public housing in Sunnydale (Merch Housing, 2016)Featured in the February 2023 neighborhood newsletter, Mercy Housing and Related featured “Healing Circles for Residents Every Tuesday in March”: