by Mirjam Schaub edited by Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Vienna, in collaboration with Public Art Fund, New York

by Mirjam Schaub edited by Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Vienna, in collaboration with Public Art Fund, New York

4

5

by Janet Cardiff

Are you near your computer ? If so, go to Google and type in “binaural audio recording.” You’ll get thousands of hits with links to sites that have pictures of dummy heads and give you recommendations for microphones that cost up to $7,000. There is a community that is obsessed with creating three-dimensional sounds. You’ll find out that the first binaural experience took place at the Paris Opera in 1881. They used microphones installed along the front edge of the stage. The recording was then sent to subscribers through the telephone system, which required them to wear a special headset that had a tiny speaker for each ear … a bit cumbersome at the time, but inventive none the less.¬ Stereo radio had not yet been implemented, so it was only forty years later when a Connecticut radio station tried to create the binaural effect by broadcasting the left channel on one frequency and the right channel on a second. Listeners would have had to own two radios, and plug the right and left ear pieces of their headsets into each radio. This was even more clumsy.¬ When I first used a binaural recording unit and listened to the results, I was immediately hooked, but I couldn’t imagine any way of using it that wasn’t gimmicky. It was only after I literally stumbled upon the format while recording and walking that I got really excited. I had found a way to be in two different places at

once. I was able to simulate space and time travel in a very simple way. I really felt like it was pushing past the novelty of the experience and entering into the type of conceptual dialogue that I was interested in pursuing.¬ I’ve always loved to escape, whether it was through walks, books, films or dreams, and it’s only now that I realize what I’ve been doing this past decade. I’ve been creating portholes into my other worlds. I also think that I’ve produced these walks at a moment in time when people have started to walk again, to get out of their cars and discover their bodies and their senses. It’s a time when relationships, or at least virtual acquaintances, are being created more and more frequently through electronic technology that mediates the voice and words. So, as Bob Dylan said, “I’ll let you be in my dreams if I can be in yours.” I invite you into mine.¬ As Mirjam says in the introduction, you cannot understand a sound by its description, and it is impossible to know how an audio walk works by reading about it. I hope you have a CD -player and headset. Because there are things that I want to tell you that I can’t write down. You won’t enjoy the virtual effect without headphones either, the ‘binaural’ recording only works with stereo headphones. So the first instructions are to find a stereo headset for your CD -player and to take the CD out of the cover of the book, and insert it into the player and press play, then …

4

5

by Janet Cardiff

Are you near your computer ? If so, go to Google and type in “binaural audio recording.” You’ll get thousands of hits with links to sites that have pictures of dummy heads and give you recommendations for microphones that cost up to $7,000. There is a community that is obsessed with creating three-dimensional sounds. You’ll find out that the first binaural experience took place at the Paris Opera in 1881. They used microphones installed along the front edge of the stage. The recording was then sent to subscribers through the telephone system, which required them to wear a special headset that had a tiny speaker for each ear … a bit cumbersome at the time, but inventive none the less.¬ Stereo radio had not yet been implemented, so it was only forty years later when a Connecticut radio station tried to create the binaural effect by broadcasting the left channel on one frequency and the right channel on a second. Listeners would have had to own two radios, and plug the right and left ear pieces of their headsets into each radio. This was even more clumsy.¬ When I first used a binaural recording unit and listened to the results, I was immediately hooked, but I couldn’t imagine any way of using it that wasn’t gimmicky. It was only after I literally stumbled upon the format while recording and walking that I got really excited. I had found a way to be in two different places at

once. I was able to simulate space and time travel in a very simple way. I really felt like it was pushing past the novelty of the experience and entering into the type of conceptual dialogue that I was interested in pursuing.¬ I’ve always loved to escape, whether it was through walks, books, films or dreams, and it’s only now that I realize what I’ve been doing this past decade. I’ve been creating portholes into my other worlds. I also think that I’ve produced these walks at a moment in time when people have started to walk again, to get out of their cars and discover their bodies and their senses. It’s a time when relationships, or at least virtual acquaintances, are being created more and more frequently through electronic technology that mediates the voice and words. So, as Bob Dylan said, “I’ll let you be in my dreams if I can be in yours.” I invite you into mine.¬ As Mirjam says in the introduction, you cannot understand a sound by its description, and it is impossible to know how an audio walk works by reading about it. I hope you have a CD -player and headset. Because there are things that I want to tell you that I can’t write down. You won’t enjoy the virtual effect without headphones either, the ‘binaural’ recording only works with stereo headphones. So the first instructions are to find a stereo headset for your CD -player and to take the CD out of the cover of the book, and insert it into the player and press play, then …

6

7

(A vocal equivalent to Jackson Pollock’s brushstroke)

by Janet Cardiff

4

5.1

by Francesca von Habsburg

8 by Daniela Zyman

5.2 5.3

5.4

11 14

161 163 166 170 177

(A thin layer of deception between us)

185 Her Long Black Hair

1.1 Comments by Tom Eccles

29 30 46

Please call Lynn 244-2730

6.1

186 (Listening to the duet of things)

(Everything is moving, nothing is out of control)

67 69 83

2.1

2.2

197 201

7.1 (How to give people a real fright)

7.2 7.3

208 213

(Walking means reinterpreting space and extending time)

Memory and the unforeseen (Seeing what is not there)

91 92

3.1

221

The affective experience of space

3.2

On the video walks

8.1 8.2

94 (It in us and we in it)

by Philip K. Dick

3.3 3.4

110 122 125

3.5

8.5

8.3 8.4

(Words can be so pathetic)

4.2

All the walks

131 132 144 148

4.1

on Edgar Allan Poe

4.3 The poetry of speech

4.4

224 234 247 251 251

253 Photo Credits, Contributors, Index of Walks, Imprint

340 by Janet Cardiff

156

344

6

7

(A vocal equivalent to Jackson Pollock’s brushstroke)

by Janet Cardiff

4

5.1

by Francesca von Habsburg

8 by Daniela Zyman

5.2 5.3

5.4

11 14

161 163 166 170 177

(A thin layer of deception between us)

185 Her Long Black Hair

1.1 Comments by Tom Eccles

29 30 46

Please call Lynn 244-2730

6.1

186 (Listening to the duet of things)

(Everything is moving, nothing is out of control)

67 69 83

2.1

2.2

197 201

7.1 (How to give people a real fright)

7.2 7.3

208 213

(Walking means reinterpreting space and extending time)

Memory and the unforeseen (Seeing what is not there)

91 92

3.1

221

The affective experience of space

3.2

On the video walks

8.1 8.2

94 (It in us and we in it)

by Philip K. Dick

3.3 3.4

110 122 125

3.5

8.5

8.3 8.4

(Words can be so pathetic)

4.2

All the walks

131 132 144 148

4.1

on Edgar Allan Poe

4.3 The poetry of speech

4.4

224 234 247 251 251

253 Photo Credits, Contributors, Index of Walks, Imprint

340 by Janet Cardiff

156

344

8

9

by Francesca von Habsburg

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Foundation was founded in 2002 as an institution dedicated to commissioning new works by some of the most challenging and creative artists of our time. The cornerstone of T-B A 21’s collection is a work by Janet Cardiff entitled To Touch, a mesmerizing sound installation that inspired my fascination with contemporary artworks that embrace technology, rather than being seduced or merely intrigued by it. Janet helped me understand that while artists are committed to creating great works of art, collectors are their guardians, and it also becomes the collectors’ responsibility to present them as respectfully as possible and to preserve them as well as to insure that others whose hands they may pass through treat them with the same sense of responsibility. Art is not an investment, it is a commitment.¬ While part of our collection consists of works acquired when the collection was founded, it became increasingly important to me to commission new works from T-B A 21’s core artists. Having dreamt of commissioning a Cardiff walk for a long time, I wanted to learn more about how she went about creating them, but I was disappointed by the lack of material available on these extraordinary works. In response, I decided to ask her whether T-B A 21 could commission a book that investigated all of her video and audio walks to date while she was preparing Walking thru’ for Vienna’s first Space in Progress exhibition during the spring of 2004. She immediately agreed and I believe that it was one of the best ideas I have had in a long time!¬ Janet Cardiff conjures anxiety and suspense while inspiring a feeling of claustrophobia within a few seconds before releasing the participant into some dreamy romantic or erotic thoughts. She enables us to visualize dreams that prefigure reality. The intrinsic risk of the experience is the lost contact with the external world, particularly when idealistic fantasies outstrip current

circumstances. Imagine a work of art that focuses your mind so intensely on the immediate moment for up to an hour at a time with a frighteningly realistic yet delicately poetic style. The experience of these walks forces us deliberately into her moment(um).¬ When you overly identify your ego with your preconceptions, you defend them as if they were literally your own body. However, when experiencing Janet’s walks, you may find yourself expanding your horizons and opening your mind to her reality, allowing it to permeate yours while abandoning all fear of losing your Self. Intuition can be remarkably powerful, particularly amongst women; it enables us to sense the otherwise concealed causes of human suffering. Janet can make you feel intuitive, even when you are not. It is a seductive experience to be temporarily guided in an intimate, yet voyeuristic manner into darker or lighter corners of your own spirit, where you might not otherwise have allowed yourself to travel. Thus you are living truly that moment, like in a meditating allowing all thoughts to enter your mind, acknowledging them, and then seeing them on their way, while the experience persists.¬ I hope that this book will enlighten and fascinate many other people about the magical world behind Janet Cardiff, her creative talent, and vivid imagination. Hopefully, it will reveal how she works in a playful, yet extremely serious manner and demonstrate how little of her work is left up to chance even though spontaneity is one of her great qualities. Her focus on the moment is so intense that one invariably becomes part of that moment. Janet’s brilliant idea of turning the book into a walk will allow the uninitiated an insight into her work process. The walk that she created for the book is fully integrated and encourages the reader to peruse the chapters in a non-linear fashion. It is not a mere pendant. It is to be experienced as another exquisite aspect of this multi-layered book.¬

8

9

by Francesca von Habsburg

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Foundation was founded in 2002 as an institution dedicated to commissioning new works by some of the most challenging and creative artists of our time. The cornerstone of T-B A 21’s collection is a work by Janet Cardiff entitled To Touch, a mesmerizing sound installation that inspired my fascination with contemporary artworks that embrace technology, rather than being seduced or merely intrigued by it. Janet helped me understand that while artists are committed to creating great works of art, collectors are their guardians, and it also becomes the collectors’ responsibility to present them as respectfully as possible and to preserve them as well as to insure that others whose hands they may pass through treat them with the same sense of responsibility. Art is not an investment, it is a commitment.¬ While part of our collection consists of works acquired when the collection was founded, it became increasingly important to me to commission new works from T-B A 21’s core artists. Having dreamt of commissioning a Cardiff walk for a long time, I wanted to learn more about how she went about creating them, but I was disappointed by the lack of material available on these extraordinary works. In response, I decided to ask her whether T-B A 21 could commission a book that investigated all of her video and audio walks to date while she was preparing Walking thru’ for Vienna’s first Space in Progress exhibition during the spring of 2004. She immediately agreed and I believe that it was one of the best ideas I have had in a long time!¬ Janet Cardiff conjures anxiety and suspense while inspiring a feeling of claustrophobia within a few seconds before releasing the participant into some dreamy romantic or erotic thoughts. She enables us to visualize dreams that prefigure reality. The intrinsic risk of the experience is the lost contact with the external world, particularly when idealistic fantasies outstrip current

circumstances. Imagine a work of art that focuses your mind so intensely on the immediate moment for up to an hour at a time with a frighteningly realistic yet delicately poetic style. The experience of these walks forces us deliberately into her moment(um).¬ When you overly identify your ego with your preconceptions, you defend them as if they were literally your own body. However, when experiencing Janet’s walks, you may find yourself expanding your horizons and opening your mind to her reality, allowing it to permeate yours while abandoning all fear of losing your Self. Intuition can be remarkably powerful, particularly amongst women; it enables us to sense the otherwise concealed causes of human suffering. Janet can make you feel intuitive, even when you are not. It is a seductive experience to be temporarily guided in an intimate, yet voyeuristic manner into darker or lighter corners of your own spirit, where you might not otherwise have allowed yourself to travel. Thus you are living truly that moment, like in a meditating allowing all thoughts to enter your mind, acknowledging them, and then seeing them on their way, while the experience persists.¬ I hope that this book will enlighten and fascinate many other people about the magical world behind Janet Cardiff, her creative talent, and vivid imagination. Hopefully, it will reveal how she works in a playful, yet extremely serious manner and demonstrate how little of her work is left up to chance even though spontaneity is one of her great qualities. Her focus on the moment is so intense that one invariably becomes part of that moment. Janet’s brilliant idea of turning the book into a walk will allow the uninitiated an insight into her work process. The walk that she created for the book is fully integrated and encourages the reader to peruse the chapters in a non-linear fashion. It is not a mere pendant. It is to be experienced as another exquisite aspect of this multi-layered book.¬

10

11

by Daniela Zyman

Thanks I want to thank Janet for dedicating so much time and effort to this work with such grace. I would also like to thank George Bures Miller, who has also patiently allowed his partner in crime and creative expression to take the time for this book. He also graciously spent many hours editing and producing the book’s CD walk. Thanks are also due to Mirjam Schaub, the author of the book, for her industrious research, insightful texts, and her fantastic knowledge of film while keeping this book from being a normal “art publication.” Daniela Zyman has been instrumental in nurturing this project through its numerous stages of development with her typical patience and loyalty to the artist (and to me as well!). She is diligently assisted by the meticulous Eva Ebersberger. I would like to thank Jacqueline Todd for her brilliant translations and Franz Peter Hugdahl for his editing. My thanks reach over the Atlantic to Susan K. Freedman and Tom Eccles for the Public Art Fund’s collaboration on this project and to Anne Wehr for her enormous effort in editing the book. Her Long Black Hair, the audio walk that Public Art Fund commissioned Janet to create for Central Park in New York and which was generously sponsored by Bloomberg, became the subject of the book’s first chapter. My huge faith in Philipp von Rohden and Thees Dohrn from Zitromat, the graphic designers from Berlin has been justified and rewarded by their many innovations especially created for this book. I hope that they never dare use them anywhere else ever again! They are perfect!

Ephemeral, time-based works of art continue to exist only in our memories. Typically, they are constructed for the hours, days or weeks of a particular show or enactment. Due to the specific time and place of their enactment, these works do not generate a physical embodiment beyond their performance. Sometimes photographs, films, and other relics prolong their existence beyond that particular moment. In the case of Janet Cardiff ’s walks, these relics are (recorded) words, (recorded) images, tapes, and audio devices. And yet, as site-specific works of art, Cardiff ’s walks are created in particular surroundings and are inseparable from those physical settings and those moments in time for which they have been created. They incorporate and reveal the hidden nature of the sites and circumstances that are experienced during the process of walking. A Cardiff site is not static; instead, it is a net of possible references and relationships between the inner space of the walker and their external environment. The body moving through space is not guided by the controlling discipline of the eye (as de Certeau has argued). The walker uses his “blind eye,” a corporeal and visceral form of knowledge. The space unfolds through the act of walking, just as a story unfolds in the process of narration. It is a dualistic experience that takes place on two intertwined levels of the body’s movement in space and the continuity of the narrative form.¬ The narration in Cardiff ’s walks, which is spoken softly into our ears, deals with the drifting effects of time. They help us – with uncanny success – to

10

11

by Daniela Zyman

Thanks I want to thank Janet for dedicating so much time and effort to this work with such grace. I would also like to thank George Bures Miller, who has also patiently allowed his partner in crime and creative expression to take the time for this book. He also graciously spent many hours editing and producing the book’s CD walk. Thanks are also due to Mirjam Schaub, the author of the book, for her industrious research, insightful texts, and her fantastic knowledge of film while keeping this book from being a normal “art publication.” Daniela Zyman has been instrumental in nurturing this project through its numerous stages of development with her typical patience and loyalty to the artist (and to me as well!). She is diligently assisted by the meticulous Eva Ebersberger. I would like to thank Jacqueline Todd for her brilliant translations and Franz Peter Hugdahl for his editing. My thanks reach over the Atlantic to Susan K. Freedman and Tom Eccles for the Public Art Fund’s collaboration on this project and to Anne Wehr for her enormous effort in editing the book. Her Long Black Hair, the audio walk that Public Art Fund commissioned Janet to create for Central Park in New York and which was generously sponsored by Bloomberg, became the subject of the book’s first chapter. My huge faith in Philipp von Rohden and Thees Dohrn from Zitromat, the graphic designers from Berlin has been justified and rewarded by their many innovations especially created for this book. I hope that they never dare use them anywhere else ever again! They are perfect!

Ephemeral, time-based works of art continue to exist only in our memories. Typically, they are constructed for the hours, days or weeks of a particular show or enactment. Due to the specific time and place of their enactment, these works do not generate a physical embodiment beyond their performance. Sometimes photographs, films, and other relics prolong their existence beyond that particular moment. In the case of Janet Cardiff ’s walks, these relics are (recorded) words, (recorded) images, tapes, and audio devices. And yet, as site-specific works of art, Cardiff ’s walks are created in particular surroundings and are inseparable from those physical settings and those moments in time for which they have been created. They incorporate and reveal the hidden nature of the sites and circumstances that are experienced during the process of walking. A Cardiff site is not static; instead, it is a net of possible references and relationships between the inner space of the walker and their external environment. The body moving through space is not guided by the controlling discipline of the eye (as de Certeau has argued). The walker uses his “blind eye,” a corporeal and visceral form of knowledge. The space unfolds through the act of walking, just as a story unfolds in the process of narration. It is a dualistic experience that takes place on two intertwined levels of the body’s movement in space and the continuity of the narrative form.¬ The narration in Cardiff ’s walks, which is spoken softly into our ears, deals with the drifting effects of time. They help us – with uncanny success – to

12

13

Janet At one time you were talking to me about the multiple time periods that appear on the edge of the event horizon. Mathematician At the event horizon, at the edge of physics in some sense, a person wouldn’t experience time in an ordinary sense, you couldn’t be talking about doing things, there wouldn’t be intervals between events most likely, rather there would be transformations going on, but not ones that a person could linearly track. Janet So a person would be in multi-dimensions at the same time ? Mathematician In some sense.

From Telephone, sound-installation, by Cardiff / Miller, T-B A 21 Collection, Vienna (2004)

visualize dreams as a precursor to reality, or even an integral part of it. Equipped with headsets, walking around and following Cardiff ’s words and stories, we sense that past, present, and future collapse into a dense, expanding field of possibilities. The voice that talks to us has a strong prosodic quality, with distinct variations in tone, timing, and vocal inflection. We know this sensation from the intense dream activity experienced in REM 2 stage of sleep and it seems familiar and comforting. Even if we can no longer distinguish between the realities of the surrounding events and the recorded, fictional events, we are intrigued and not disconcerted by the new horizon of possibilities. Our sensation of time and space becomes fictionalized. “Now” and “here” dissipates and coalesces with multiple periods of time and places.¬ In her work Telephone we listen in a conversation Cardiff has had with a mathematician, and which suggests that this multiplicity is not imaginary but a functional attribute of our physical world.¬

Cardiff ’s walks are highly individual and very personal. The voices are talking to “you” and you are not an abstract viewer, disassociated from the object of aesthetic perception. You, the audience, are in a constant process of development, establishing relationships with outer and inner worlds and engaged in a continual metaphorical reading. Although the walks are ephemeral, this publication attempts to counteract the loss of memory inherent in any form of experience and historization by extending the walking / listening /reading paradigm onto the printed page. It collects and rescues some of Cardiff ’s words and phrases that are part of her walks, transposes them in a literary form and yet, as The Walk Book is a walk in its own right, it dissolves all possible determinations and codifications. By resisting definitions, asking questions and engaging audiences, The Walk Book offers different approaches to the nature and the experience of an artistic practice that has revealed itself as one of the most potent and thought provoking sites in contemporary culture.¬

12

13

Janet At one time you were talking to me about the multiple time periods that appear on the edge of the event horizon. Mathematician At the event horizon, at the edge of physics in some sense, a person wouldn’t experience time in an ordinary sense, you couldn’t be talking about doing things, there wouldn’t be intervals between events most likely, rather there would be transformations going on, but not ones that a person could linearly track. Janet So a person would be in multi-dimensions at the same time ? Mathematician In some sense.

From Telephone, sound-installation, by Cardiff / Miller, T-B A 21 Collection, Vienna (2004)

visualize dreams as a precursor to reality, or even an integral part of it. Equipped with headsets, walking around and following Cardiff ’s words and stories, we sense that past, present, and future collapse into a dense, expanding field of possibilities. The voice that talks to us has a strong prosodic quality, with distinct variations in tone, timing, and vocal inflection. We know this sensation from the intense dream activity experienced in REM 2 stage of sleep and it seems familiar and comforting. Even if we can no longer distinguish between the realities of the surrounding events and the recorded, fictional events, we are intrigued and not disconcerted by the new horizon of possibilities. Our sensation of time and space becomes fictionalized. “Now” and “here” dissipates and coalesces with multiple periods of time and places.¬ In her work Telephone we listen in a conversation Cardiff has had with a mathematician, and which suggests that this multiplicity is not imaginary but a functional attribute of our physical world.¬

Cardiff ’s walks are highly individual and very personal. The voices are talking to “you” and you are not an abstract viewer, disassociated from the object of aesthetic perception. You, the audience, are in a constant process of development, establishing relationships with outer and inner worlds and engaged in a continual metaphorical reading. Although the walks are ephemeral, this publication attempts to counteract the loss of memory inherent in any form of experience and historization by extending the walking / listening /reading paradigm onto the printed page. It collects and rescues some of Cardiff ’s words and phrases that are part of her walks, transposes them in a literary form and yet, as The Walk Book is a walk in its own right, it dissolves all possible determinations and codifications. By resisting definitions, asking questions and engaging audiences, The Walk Book offers different approaches to the nature and the experience of an artistic practice that has revealed itself as one of the most potent and thought provoking sites in contemporary culture.¬

14

15

Over the past decade Janet Cardiff has been making binaural audio walks that constitute a new art form. These walks do not adhere to the common classifications of the multi-media installation, performance art, the site-specific artwork, or the audioguide, yet they draw upon all of these genres or categories. Cardiff equips her participants with a portable CD player, or a video camera together with a stereo headset at the point of departure.¬ Then Cardiff ’s voice takes charge. She tells us where to stop which way to go, where to fix our gaze. At the same time our ears are filled with remarkable sounds. They might evoke a sense of the improbable, like the beating wings of a swarm of flies, or the curiosity concerning the scraps of conversation from a nearby bench. They might point out the rustling noise of leaves crushed underfoot, or bring back the drifting notes of a long-forgotten piece of music. While guiding us gently across an invisible stage, Cardiff ’s audio tracks transform the world around us. Commentators have described this effect in terms of ‘physical cinema’: the overwhelming physical immersion in an apparently boundless soundtrack that begins to dominate our shared experience. Our surroundings seem to be recreated entirely out of sound and this acoustic animation of the material world captures our imagination. Our purview suddenly expands into a major cinematic event.¬

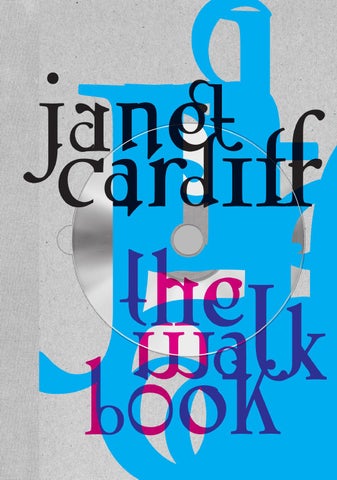

The format of the audio walks is similar to that of an audioguide. You are given a CD player and told to stand or sit in a particular spot and press play. On the CD you hear my voice giving directions, like “turn left here” or “go through this gateway,” layered on a background of sounds: the sound of my footsteps, traffic, birds, and miscellaneous sound effects that have been pre-recorded on the same site as where they are being heard. This is the important part of the recording. The virtual recorded soundscape has to mimic the real physical one in order to create a new world as a seamless Janet Cardiff recording combination of the two. with dummy head in Rome My voice gives directions but also relates thoughts and narrative elements, which instill in the listener a desire to continue and finish the walk.¬ All of my walks are recorded in binaural audio with multilayers of sound effects, music, and voices (sometimes as many as 18 tracks) added to the main walking track to create a 3D sphere of sound. Binaural audio is a technique that uses miniature microphones placed in the ears of a person or dummy head. The result is an incredibly lifelike 3D reproduction of sound. Played back on a headset, it is almost as if the recorded events were taking place live.¬

14

15

Over the past decade Janet Cardiff has been making binaural audio walks that constitute a new art form. These walks do not adhere to the common classifications of the multi-media installation, performance art, the site-specific artwork, or the audioguide, yet they draw upon all of these genres or categories. Cardiff equips her participants with a portable CD player, or a video camera together with a stereo headset at the point of departure.¬ Then Cardiff ’s voice takes charge. She tells us where to stop which way to go, where to fix our gaze. At the same time our ears are filled with remarkable sounds. They might evoke a sense of the improbable, like the beating wings of a swarm of flies, or the curiosity concerning the scraps of conversation from a nearby bench. They might point out the rustling noise of leaves crushed underfoot, or bring back the drifting notes of a long-forgotten piece of music. While guiding us gently across an invisible stage, Cardiff ’s audio tracks transform the world around us. Commentators have described this effect in terms of ‘physical cinema’: the overwhelming physical immersion in an apparently boundless soundtrack that begins to dominate our shared experience. Our surroundings seem to be recreated entirely out of sound and this acoustic animation of the material world captures our imagination. Our purview suddenly expands into a major cinematic event.¬

The format of the audio walks is similar to that of an audioguide. You are given a CD player and told to stand or sit in a particular spot and press play. On the CD you hear my voice giving directions, like “turn left here” or “go through this gateway,” layered on a background of sounds: the sound of my footsteps, traffic, birds, and miscellaneous sound effects that have been pre-recorded on the same site as where they are being heard. This is the important part of the recording. The virtual recorded soundscape has to mimic the real physical one in order to create a new world as a seamless Janet Cardiff recording combination of the two. with dummy head in Rome My voice gives directions but also relates thoughts and narrative elements, which instill in the listener a desire to continue and finish the walk.¬ All of my walks are recorded in binaural audio with multilayers of sound effects, music, and voices (sometimes as many as 18 tracks) added to the main walking track to create a 3D sphere of sound. Binaural audio is a technique that uses miniature microphones placed in the ears of a person or dummy head. The result is an incredibly lifelike 3D reproduction of sound. Played back on a headset, it is almost as if the recorded events were taking place live.¬

16

17 In many of Cardiff ’s audio walks, like those in the Carnegie Library or Central Park, the conventions for city walks or museums tours are overturned. They draw participants out of their habituated view and offer them a different approach to the world ‘out there’. They synchronize the walker’s own breathing which is heard only through headphones with that of a disembodied voice. This experience is akin to a trance in that it simulates incipient consciousness through the connection between the listener and the calm, steady voice of an unknown woman.¬ 1 SFMOMA Comment Book 1

I establish a sense of intimacy through what I write, but also in the way I record my voice. It’s not an acted voice like a radio announcer’s voice. People aren’t going to relate to that. When you’re talking to them very closely – the way I record makes it sound like it’s almost coming out of their head – it’s like it’s coming from between their ears. Then if I talk very calmly and talk as if I’m talking to myself and thinking to myself, it doesn’t make it too creepy. Then other sounds begin to enter in. They are the sounds from your current surroundings. Contact to the outside world is reduced, but not completely lost through the headphones. Conat the same time sequently, you are inhabiting at least two acoustic spaces.¬ Cardiff ’s art involves anticipating occurrences and that anticipation creates strange moments of synchronicity. You see ducks in the Central Park pond just as the little girl on the soundtrack says she sees them. You become more intensely aware of the beyond the headset point of friction between you and the world. Your visual senses are amplified, trying to equilibrate the acoustic experience with what you see.¬ Sounds that belong to the past lead a greedy, vampire-like existence when returned to their place of origin. Reality becomes infiltrated by virtuality. We cannot immediately assign what we hear to the outside world or the world inside the headphones. This inability produces alarmingly rapid synaesthetic effects. It colonizes our unconscious and uses acoustic hooks to engage the whole of our current perception. This is part of what makes Cardiff ’s walks so fascinating: (and therefore our awareness) our attention is guided and modified by what we hear and this influences what we expect to see. What we hear in perfect 3D sound demands to be materialized in visual form. Past and present sounds overlap, take hold of what we have just seen, and

form a kind of audio-visual bridge between them. Like a game of cadavre exquis, reality seems to fan out into different acoustic and visual worlds that partly duplicate and partly complement one other.¬ “Not used to being told where to go, I was resistant at first, and then later relaxed, enjoyed, and experienced confusion between reality and recordings, [I] would pick up [the] earphones, to see if it was really happening or hearing it only […]. Thanks – Susan” 1¬ In À la Recherche du Temps Perdu, Marcel Proust used the notion of ‘the miracle of an analogy’ to describe what takes place here. There is an unexpected merger of something from a long time ago with something that is being experienced in the present. In Cardiff ’s walks, the (mémoire involontaire) magic of involuntary memory suddenly transpires when things that were once thought or just heard coincide with what is presently seen. It is interesting that both possibilities are equally disturbing in that they uncannily convey the dystopian nightmare of a completely predetermined world in the unexpectedly synchronized sounds and the unstaged things we see.¬ It is satisfying but at the same time unsettling if you suddenly spot a pigeon with an injured foot collecting its daily ration of French fries in front of Bishop’s Gate, just as Cardiff ‘predicted’ in The Missing Voice: Case Study B. So what should you believe ? The sound of rotors, which can only come from a helicopter rising up directly behind you ? The vapor trail in the sky that merely confirms the existence of distant airplanes ?¬

Janet I like looking at the rooftops from here. A plane is flying above the buildings. There’s a pigeon walking around me, with a stub as one foot, and only two toes on the other one. Jvox from voice recorder A woman is carrying a shopping bag. someone just left some bread for the pigeons, now they’re all swooping from every direction, down to get a piece. People look at me as I pass. They wonder why I am talking into this thing. From The Missing Voice: Case Study B, Artangel, Whitechapel Library, London, UK (1999)

16

17 In many of Cardiff ’s audio walks, like those in the Carnegie Library or Central Park, the conventions for city walks or museums tours are overturned. They draw participants out of their habituated view and offer them a different approach to the world ‘out there’. They synchronize the walker’s own breathing which is heard only through headphones with that of a disembodied voice. This experience is akin to a trance in that it simulates incipient consciousness through the connection between the listener and the calm, steady voice of an unknown woman.¬ 1 SFMOMA Comment Book 1

I establish a sense of intimacy through what I write, but also in the way I record my voice. It’s not an acted voice like a radio announcer’s voice. People aren’t going to relate to that. When you’re talking to them very closely – the way I record makes it sound like it’s almost coming out of their head – it’s like it’s coming from between their ears. Then if I talk very calmly and talk as if I’m talking to myself and thinking to myself, it doesn’t make it too creepy. Then other sounds begin to enter in. They are the sounds from your current surroundings. Contact to the outside world is reduced, but not completely lost through the headphones. Conat the same time sequently, you are inhabiting at least two acoustic spaces.¬ Cardiff ’s art involves anticipating occurrences and that anticipation creates strange moments of synchronicity. You see ducks in the Central Park pond just as the little girl on the soundtrack says she sees them. You become more intensely aware of the beyond the headset point of friction between you and the world. Your visual senses are amplified, trying to equilibrate the acoustic experience with what you see.¬ Sounds that belong to the past lead a greedy, vampire-like existence when returned to their place of origin. Reality becomes infiltrated by virtuality. We cannot immediately assign what we hear to the outside world or the world inside the headphones. This inability produces alarmingly rapid synaesthetic effects. It colonizes our unconscious and uses acoustic hooks to engage the whole of our current perception. This is part of what makes Cardiff ’s walks so fascinating: (and therefore our awareness) our attention is guided and modified by what we hear and this influences what we expect to see. What we hear in perfect 3D sound demands to be materialized in visual form. Past and present sounds overlap, take hold of what we have just seen, and

form a kind of audio-visual bridge between them. Like a game of cadavre exquis, reality seems to fan out into different acoustic and visual worlds that partly duplicate and partly complement one other.¬ “Not used to being told where to go, I was resistant at first, and then later relaxed, enjoyed, and experienced confusion between reality and recordings, [I] would pick up [the] earphones, to see if it was really happening or hearing it only […]. Thanks – Susan” 1¬ In À la Recherche du Temps Perdu, Marcel Proust used the notion of ‘the miracle of an analogy’ to describe what takes place here. There is an unexpected merger of something from a long time ago with something that is being experienced in the present. In Cardiff ’s walks, the (mémoire involontaire) magic of involuntary memory suddenly transpires when things that were once thought or just heard coincide with what is presently seen. It is interesting that both possibilities are equally disturbing in that they uncannily convey the dystopian nightmare of a completely predetermined world in the unexpectedly synchronized sounds and the unstaged things we see.¬ It is satisfying but at the same time unsettling if you suddenly spot a pigeon with an injured foot collecting its daily ration of French fries in front of Bishop’s Gate, just as Cardiff ‘predicted’ in The Missing Voice: Case Study B. So what should you believe ? The sound of rotors, which can only come from a helicopter rising up directly behind you ? The vapor trail in the sky that merely confirms the existence of distant airplanes ?¬

Janet I like looking at the rooftops from here. A plane is flying above the buildings. There’s a pigeon walking around me, with a stub as one foot, and only two toes on the other one. Jvox from voice recorder A woman is carrying a shopping bag. someone just left some bread for the pigeons, now they’re all swooping from every direction, down to get a piece. People look at me as I pass. They wonder why I am talking into this thing. From The Missing Voice: Case Study B, Artangel, Whitechapel Library, London, UK (1999)

18

19

2 George Bures Miller in: Wayne Baerwaldt, The Paradise Institute (Venice: XLIX Biennale di Venezia, 2001) 142

Cardiff ’s works demonstrate the extent to which our hearing influences, infiltrates, and even directs what we see. As her partner and collaborator, George Bures Miller, says: “I like the idea that we are building a simulated experience in the attempt to make people feel more connected to real life.”2 These works maintain a perfect balance between simplicity and technical ingenuity, transparency and magic.¬ Although Cardiff gives her listeners certain points of reference, she also talks about things they cannot see. This often involves recalling something from memory, raising questions – addressed to herself and the listener – related to the status of identity and the occasional desire to become imperceptible. Her comments are philosophically profound and disarmingly direct.¬

Janet Have you ever had the urge to disappear, to escape from your own life even for just a little while – like walking out of one room, then into a different one ? I remember the first time I said it, we were driving to the mountains: Sometimes I just want to disappear, I said … From The Missing Voice: Case Study B

Before the moment of pensive reflection becomes too heavy, (and often male) a second, more down-to-earth voice breaks in.¬

Janet … he freaked out. Afterwards I only thought it to myself. Here’s another banana peel on the ground. From The Missing Voice: Case Study B

3 All excerpts are from The Missing Voice: Case Study B

The recorded voices begin to overlap and interconnect. (Detective – As far as I can tell, she is mapping different paths through the city. I can’t seem to find a reason for the things she notices and records.) Fragments of a love story emerge. (“I feel an emptiness more each day, as if a part of him that was inside of me is now slowly leaking out.”) They can switch abruptly into violent crime. (“He grabs me from behind, his hand over my mouth. I bite his fingers and hit him in the ribs.”) Or, they can dissolve into nothingness. (“It was a sign to tell him she didn’t exist.”) 3 Such sudden changes of mood and shifts in atmosphere are important for holding the participant’s attention and preventing one aspect of the narrative from becoming too dominant.¬

I’ve realized that I have a brain that doesn’t function very well in a linear manner. Some people are very good at conversation and storytelling, working logically from one step to another. I’m very bad at it because I skip from one thing to another – my brain just works like that. I’ve never developed the discipline that’s needed for that. So I think the walks function in a way that I’ve always tried to express the way our minds jump around all over the place. But slowing down the process of telling a story has allowed me to realize what you need in order to build up a certain amount of intimacy, a certain amount of interest in the narrative, but still make it open-ended.¬

18

19

2 George Bures Miller in: Wayne Baerwaldt, The Paradise Institute (Venice: XLIX Biennale di Venezia, 2001) 142

Cardiff ’s works demonstrate the extent to which our hearing influences, infiltrates, and even directs what we see. As her partner and collaborator, George Bures Miller, says: “I like the idea that we are building a simulated experience in the attempt to make people feel more connected to real life.”2 These works maintain a perfect balance between simplicity and technical ingenuity, transparency and magic.¬ Although Cardiff gives her listeners certain points of reference, she also talks about things they cannot see. This often involves recalling something from memory, raising questions – addressed to herself and the listener – related to the status of identity and the occasional desire to become imperceptible. Her comments are philosophically profound and disarmingly direct.¬

Janet Have you ever had the urge to disappear, to escape from your own life even for just a little while – like walking out of one room, then into a different one ? I remember the first time I said it, we were driving to the mountains: Sometimes I just want to disappear, I said … From The Missing Voice: Case Study B

Before the moment of pensive reflection becomes too heavy, (and often male) a second, more down-to-earth voice breaks in.¬

Janet … he freaked out. Afterwards I only thought it to myself. Here’s another banana peel on the ground. From The Missing Voice: Case Study B

3 All excerpts are from The Missing Voice: Case Study B

The recorded voices begin to overlap and interconnect. (Detective – As far as I can tell, she is mapping different paths through the city. I can’t seem to find a reason for the things she notices and records.) Fragments of a love story emerge. (“I feel an emptiness more each day, as if a part of him that was inside of me is now slowly leaking out.”) They can switch abruptly into violent crime. (“He grabs me from behind, his hand over my mouth. I bite his fingers and hit him in the ribs.”) Or, they can dissolve into nothingness. (“It was a sign to tell him she didn’t exist.”) 3 Such sudden changes of mood and shifts in atmosphere are important for holding the participant’s attention and preventing one aspect of the narrative from becoming too dominant.¬

I’ve realized that I have a brain that doesn’t function very well in a linear manner. Some people are very good at conversation and storytelling, working logically from one step to another. I’m very bad at it because I skip from one thing to another – my brain just works like that. I’ve never developed the discipline that’s needed for that. So I think the walks function in a way that I’ve always tried to express the way our minds jump around all over the place. But slowing down the process of telling a story has allowed me to realize what you need in order to build up a certain amount of intimacy, a certain amount of interest in the narrative, but still make it open-ended.¬

20

21

Janet All these people walking past. They all have their secrets. Unwanted memories that creep into your mind in the middle of the night. Even as a child I had things that I couldn’t tell anyone. From Her Long Black Hair, Public Art Fund, Central Park, New York, USA (2004)

Central Park, New York

The dominant force of the work is manifest in the pull exerted on the listener by the artist’s voice. It is a seemingly ageless, pleasantly deep, feminine voice that ranges from matter-of-fact to sexy to solicitous. It is a voice that is neither too harsh nor without knowing why too soft and that you find pleasant to listen to and are happy to follow. It is perhaps the same kind of irrational intimacy on a park bench that allows you to tell your life story to a complete stranger. In Cardiff ’s walks, however, the obverse function allows you to place your confidence in a voice and accept its tempting offers out of a mixture of curiosity and fear.¬

Man beside you Excuse me, but who is she ? Janet I … don’t know. I just found it at a flea market. Man It looks like pictures of my mother when she was young. She had long black hair just like that. Janet It’s taken right here … see ? The exact same spot. Man It’s not her. She was here for a while though. It could have been her. Janet You grew up in NYC ? Man No, I’m just visiting. My mother left us and that’s when she came here. Janet … she left you ? Man For a few years, I mean. sound of crickets Janet How old were you ? Man Only 7 … she’d phone once in a while but dad wouldn’t let us talk to her. He’d sit in the kitchen listening to the radio, drinking. He even stopped talking for awhile except for yelling at us. I blamed him for her leaving. Now I realize how sad he was. I think I would die if my wife left me. Janet But she came back ? Man Yeah, like it was Christmas – presents and kisses. Sorry, what time is it … I have to go. Nice talking to you … Janet Yeah … goodbye. Nice talking to you. pause Put the photo away. From Her Long Black Hair

20

21

Janet All these people walking past. They all have their secrets. Unwanted memories that creep into your mind in the middle of the night. Even as a child I had things that I couldn’t tell anyone. From Her Long Black Hair, Public Art Fund, Central Park, New York, USA (2004)

Central Park, New York

The dominant force of the work is manifest in the pull exerted on the listener by the artist’s voice. It is a seemingly ageless, pleasantly deep, feminine voice that ranges from matter-of-fact to sexy to solicitous. It is a voice that is neither too harsh nor without knowing why too soft and that you find pleasant to listen to and are happy to follow. It is perhaps the same kind of irrational intimacy on a park bench that allows you to tell your life story to a complete stranger. In Cardiff ’s walks, however, the obverse function allows you to place your confidence in a voice and accept its tempting offers out of a mixture of curiosity and fear.¬

Man beside you Excuse me, but who is she ? Janet I … don’t know. I just found it at a flea market. Man It looks like pictures of my mother when she was young. She had long black hair just like that. Janet It’s taken right here … see ? The exact same spot. Man It’s not her. She was here for a while though. It could have been her. Janet You grew up in NYC ? Man No, I’m just visiting. My mother left us and that’s when she came here. Janet … she left you ? Man For a few years, I mean. sound of crickets Janet How old were you ? Man Only 7 … she’d phone once in a while but dad wouldn’t let us talk to her. He’d sit in the kitchen listening to the radio, drinking. He even stopped talking for awhile except for yelling at us. I blamed him for her leaving. Now I realize how sad he was. I think I would die if my wife left me. Janet But she came back ? Man Yeah, like it was Christmas – presents and kisses. Sorry, what time is it … I have to go. Nice talking to you … Janet Yeah … goodbye. Nice talking to you. pause Put the photo away. From Her Long Black Hair

22

4 SFMOMA Comment Book 4

23

Cardiff ’s walks profit from the wealth of stereotypical and idealized cultural images associated with the disembodied female voice. Many of them are connected to the idea of a mother’s lullaby in the darkness.¬ “I love your voice. I would follow you anywhere.”4¬ We are reminded of Scheherazade, who, knowing that she must continue telling stories in order to stay alive, hides herself behind her stories for her unsatisfied listener. The Sirens also come to mind. Their singing arouses feelings of happiness and fantasies of regression while their promises bring unhappiness and ruin upon those who listen. Cardiff often refers to her voice as if it were an independent persona, something separate from her self. This voice draws us Daytime shot from the balcony of the inside a world of ideas all its Hebbel Theater, Berlin own and lets us become part of a story that enmeshes us in a universe parallel to our own, a world in which we encounter ourselves as ‘other’ persons. Perhaps its simplicity is a key to its accomplishment. The mere presence of a voice that seemingly devotes itself to each individual listener is in itself a form of wish fulfillment. It satisfies the desire to experience something out of the ordinary, the longing for intensity and intimacy that lies just beneath the surface of visibility.¬ The video walks and installations produced by Cardiff and George Bures Miller also thrive on this familiar promise of a ‘guardian angel’. Appropriately, it is also the title of their first collaborative piece, made in 1983. In the video Hillclimbing (1999), a friendly yet uncertain “Are you okay ?” suffices to turn the endless loop of George falling down the snow-covered slopes into a meaningful, comforting experience. The frenetic reassurance from David Bowie’s Rock’n’ Roll Suicide that “You’re not alone” might not immediately dry the tears of the distraught woman in the back of the room in The Berlin Files (2003), but most viewers would instinctively assent that they would find profound solace if this amazingly optimistic singer appeared in the bar with this song. Consolation of the participants is a crucial component in

Cardiff ’s walks. Without it, her listeners would never obey the or video walk voice’s instructions. The success of an audio walk is dependent on the collaborative participation of the audience. Each listener makes an individual pact with the voice out of apparent mutual regard.¬

From Ghost Machine

A video walk is similar to an audio walk but functions quite differently because of the visuals. With a video walk, the participants receive a small digital video camera with headphones. George does the recording carrying a professional camera with the binaural microphones in his ears along sections of the route, which have all been planned with actors and props. Then there is an extensive editing process similar to the construction of a film, using the acted scenes, sound effects, and video effects to create a continuous motion. The audience follows this prerecorded film on the camera while my voice gives directions on the audio. The architecture in the video stays the same as the physical world, but the people and their actions change, so there is a strange disjunction for the viewer about what is real. They start to believe that what is in the camera is the real image taking precedence over the real world.¬

22

4 SFMOMA Comment Book 4

23

Cardiff ’s walks profit from the wealth of stereotypical and idealized cultural images associated with the disembodied female voice. Many of them are connected to the idea of a mother’s lullaby in the darkness.¬ “I love your voice. I would follow you anywhere.”4¬ We are reminded of Scheherazade, who, knowing that she must continue telling stories in order to stay alive, hides herself behind her stories for her unsatisfied listener. The Sirens also come to mind. Their singing arouses feelings of happiness and fantasies of regression while their promises bring unhappiness and ruin upon those who listen. Cardiff often refers to her voice as if it were an independent persona, something separate from her self. This voice draws us Daytime shot from the balcony of the inside a world of ideas all its Hebbel Theater, Berlin own and lets us become part of a story that enmeshes us in a universe parallel to our own, a world in which we encounter ourselves as ‘other’ persons. Perhaps its simplicity is a key to its accomplishment. The mere presence of a voice that seemingly devotes itself to each individual listener is in itself a form of wish fulfillment. It satisfies the desire to experience something out of the ordinary, the longing for intensity and intimacy that lies just beneath the surface of visibility.¬ The video walks and installations produced by Cardiff and George Bures Miller also thrive on this familiar promise of a ‘guardian angel’. Appropriately, it is also the title of their first collaborative piece, made in 1983. In the video Hillclimbing (1999), a friendly yet uncertain “Are you okay ?” suffices to turn the endless loop of George falling down the snow-covered slopes into a meaningful, comforting experience. The frenetic reassurance from David Bowie’s Rock’n’ Roll Suicide that “You’re not alone” might not immediately dry the tears of the distraught woman in the back of the room in The Berlin Files (2003), but most viewers would instinctively assent that they would find profound solace if this amazingly optimistic singer appeared in the bar with this song. Consolation of the participants is a crucial component in

Cardiff ’s walks. Without it, her listeners would never obey the or video walk voice’s instructions. The success of an audio walk is dependent on the collaborative participation of the audience. Each listener makes an individual pact with the voice out of apparent mutual regard.¬

From Ghost Machine

A video walk is similar to an audio walk but functions quite differently because of the visuals. With a video walk, the participants receive a small digital video camera with headphones. George does the recording carrying a professional camera with the binaural microphones in his ears along sections of the route, which have all been planned with actors and props. Then there is an extensive editing process similar to the construction of a film, using the acted scenes, sound effects, and video effects to create a continuous motion. The audience follows this prerecorded film on the camera while my voice gives directions on the audio. The architecture in the video stays the same as the physical world, but the people and their actions change, so there is a strange disjunction for the viewer about what is real. They start to believe that what is in the camera is the real image taking precedence over the real world.¬

24

5 Janet Cardiff, The Paradise Institute 13

6 George Bures Miller, The Paradise Institute 15

7 Atom Egoyan, On Janet Cardiff, BOMB Magazine, 79 (spring 2002) 3

25 Instinctively you try to locate the source of the things you hear. Maybe this isn’t a walk at all but rather a covert attempt to escape from something ? Maybe you’ve become mixed up in one of those increasingly popular ‘murder mystery weekends’ ? And, who knows, maybe you’re the perpetrator ? Confused, you continue on your way, while Cardiff ’s voice succeeds in makthrough a process of skillful acoustic infiltration ing your own familiar world appear increasingly mysterious. “We’re trying to connect right away to the remembered experiences that your body knows […]” 5¬ “[T]he walks […] make you hyper-aware of your environment around you. I thought it would take away from that because you put a headphone on and walk around with a Discman, but all of a sudden, your senses are alert. They say media kills your senses, but it is not true because it can actually enliven them.” George Bures Miller adds: “It is like MSG for the senses.” 6¬ Considering this ‘physical cinema’, film director Atom Egoyan admits that he is somewhat embarrassed by the comparatively stiff formality of conventional cinema: here you have the audience, there the screen, and opposite it the projector. 7 By contrast, Cardiff ’s method of plucking the drama from the screen and conveying it through the headphones to each participant effectively transforms the world around us into a kind of backdrop. Real life takes on an almost exemplary quality. This does not make reality ‘unreal’, nor is it suddenly ‘pluralized’. On the contrary, Cardiff ’s approach suggests that our seemingly dull everyday and parallel existence has the potential to reveal simultaneous magical worlds of experience. Her work explores some of these barely underestimated visible and often undetected levels of reality and shows how the audible world of invisibility produces its own event horizon.¬

The experience of Janet Cardiff ’s audio walks cannot be compared with listening to a Walkman, just as her video walks cannot be compared with watching a movie in a cinema. In both those cases, the listener or viewer can only become immersed in the audio recording or the filmic illusion if they are able to forget their actual spatial and temporal surroundings and become oblivious to their own body. Neither the jogger’s sound track, nor the darkened cinema attempt to heighten self-awareness. Their primary function is to limit the spectrum of sensory experience and minimize the participant’s on the other hand self-awareness. Cardiff, consciously inverts those typical uses of technology and broadens the spectrum of sensory The Paradise Institute (2001) experience by forcing the spectator to interact with the surrounding environment. The artist has already experienced the space that the participants visit. She has infiltrated the site in a different form and captured its sounds and then she plays them back later. Having observed the environment and taken note of the patterns of movement there, she can anticipate what might happen to us when we visit this place later, what we might see, hear, and feel. When forced to synchronize ourselves with the disembodied pre-recorded voice, our sensory impressions are amplified and we want to reassure ourselves about our own bodies as sensory beings. We strengthen a sense of ourselves from this experience.¬ Cardiff creates a soundtrack for the real out of their darkened theaters world and by taking cinematic conventions she creates a fully cinematic experience in broad daylight.¬ 5

It is interesting how a sound effect can completely transform and affect a location. By adding the sound of rustling leaves, someone running by, or a few bars of scary music, all of a sudden reality turns into a filmic event.¬

24

5 Janet Cardiff, The Paradise Institute 13

6 George Bures Miller, The Paradise Institute 15

7 Atom Egoyan, On Janet Cardiff, BOMB Magazine, 79 (spring 2002) 3

25 Instinctively you try to locate the source of the things you hear. Maybe this isn’t a walk at all but rather a covert attempt to escape from something ? Maybe you’ve become mixed up in one of those increasingly popular ‘murder mystery weekends’ ? And, who knows, maybe you’re the perpetrator ? Confused, you continue on your way, while Cardiff ’s voice succeeds in makthrough a process of skillful acoustic infiltration ing your own familiar world appear increasingly mysterious. “We’re trying to connect right away to the remembered experiences that your body knows […]” 5¬ “[T]he walks […] make you hyper-aware of your environment around you. I thought it would take away from that because you put a headphone on and walk around with a Discman, but all of a sudden, your senses are alert. They say media kills your senses, but it is not true because it can actually enliven them.” George Bures Miller adds: “It is like MSG for the senses.” 6¬ Considering this ‘physical cinema’, film director Atom Egoyan admits that he is somewhat embarrassed by the comparatively stiff formality of conventional cinema: here you have the audience, there the screen, and opposite it the projector. 7 By contrast, Cardiff ’s method of plucking the drama from the screen and conveying it through the headphones to each participant effectively transforms the world around us into a kind of backdrop. Real life takes on an almost exemplary quality. This does not make reality ‘unreal’, nor is it suddenly ‘pluralized’. On the contrary, Cardiff ’s approach suggests that our seemingly dull everyday and parallel existence has the potential to reveal simultaneous magical worlds of experience. Her work explores some of these barely underestimated visible and often undetected levels of reality and shows how the audible world of invisibility produces its own event horizon.¬

The experience of Janet Cardiff ’s audio walks cannot be compared with listening to a Walkman, just as her video walks cannot be compared with watching a movie in a cinema. In both those cases, the listener or viewer can only become immersed in the audio recording or the filmic illusion if they are able to forget their actual spatial and temporal surroundings and become oblivious to their own body. Neither the jogger’s sound track, nor the darkened cinema attempt to heighten self-awareness. Their primary function is to limit the spectrum of sensory experience and minimize the participant’s on the other hand self-awareness. Cardiff, consciously inverts those typical uses of technology and broadens the spectrum of sensory The Paradise Institute (2001) experience by forcing the spectator to interact with the surrounding environment. The artist has already experienced the space that the participants visit. She has infiltrated the site in a different form and captured its sounds and then she plays them back later. Having observed the environment and taken note of the patterns of movement there, she can anticipate what might happen to us when we visit this place later, what we might see, hear, and feel. When forced to synchronize ourselves with the disembodied pre-recorded voice, our sensory impressions are amplified and we want to reassure ourselves about our own bodies as sensory beings. We strengthen a sense of ourselves from this experience.¬ Cardiff creates a soundtrack for the real out of their darkened theaters world and by taking cinematic conventions she creates a fully cinematic experience in broad daylight.¬ 5

It is interesting how a sound effect can completely transform and affect a location. By adding the sound of rustling leaves, someone running by, or a few bars of scary music, all of a sudden reality turns into a filmic event.¬

26

27

The element of fear is a natural choice for the artist, as is indiand science fiction cated by the scattered film noir quotations as well as the murder-mystery elements in the walks. While Cardiff ’s employment of familiar suspense mechanisms triggers our natural alarm system, she uses it to distract us from and assuage our uncertainty about the new format. After all, if the aim is to operate in the background, it is wise to draw attention to the foreground.¬

If the audience is entertained or their attention is captured, then you can draw them into the piece so they won’t even think about the effort of walking or where the voice is taking them.¬ and writes

8 Atom Egoyan 3

Cardiff talks quite openly in interviews and publications about the recording techniques she and George Bures Miller use. She does not hesitate to present Shirley, the polystyrene dummy head painted over in blue with its modeled auricles. She deftly describes the 30 soundtracks that have to be mixed together, and the “hmm” and “sss” sounds that are painstakingly edited out by Miller. There is a distinct advantage in deploying this collage technique in that the cuts between two sounds cannot be heard, while it is easier to determine where cuts have been (even when they are superimposed in one shot) made between two images. Of course, the soundtrack can also be edited in such a way so that a change of atmosphere can be felt, for example, by changing the background sounds from that of an outdoor to one of an indoor space. Cardiff and Miller occasionally do this in order to suspend the perfect illusion of an acoustic space for just a moment, but this remains the exception that proves the rule. As Atom Egoyan concludes: “The degree of interaction is profoundly respectful, yet extremely invasive.”8¬ It is good for participants to have a rough idea of how the walks function from a technical point of view, so that they don’t spend too much time thinking about the technology behind them. This is not a goal in itself, nor does it explain the wide range of emotions and disturbing effects triggered by these seemingly simple audio and video pieces. It cannot the loneliness explain the poetry, the beauty, or the melancholy of Janet Cardiff ’s works.¬

An irreproducible experience The Walk Book is not intended to be an exhaustive travel guide through the world of past walks. It simply offers some associative aids, knowing that it is impossible to recreate the walks through pictures and words. If the book has one overriding theme, it resides in its preoccupation with what, ultimately, is a lost experience. Text and voice, book and CD all compete for the ‘truth’ of this loss, because neither the ‘sound pieces’ of past walks on the CD , nor the photos of the original locations in the book, nor the printed extracts from the scripts can attain or recreate the experience of the sensory impressions taken in by the walkers on their own journeys.¬ In its skillful exploitation of the fundamental principles of synaesthesia, Cardiff ’s art reaches a place beyond truth and fiction, beyond reality and illusion. Welcome to the realm of the unforeseen, a world of involuntary memory, that form of erratic recollection, which allows sexual us to confront ourselves as thinking, multi-sensual, and utterly temporal beings. Cardiff ’s walks offer a gentle reintroduction to ourselves. How long has it been since our last encounter ?¬

26

27

The element of fear is a natural choice for the artist, as is indiand science fiction cated by the scattered film noir quotations as well as the murder-mystery elements in the walks. While Cardiff ’s employment of familiar suspense mechanisms triggers our natural alarm system, she uses it to distract us from and assuage our uncertainty about the new format. After all, if the aim is to operate in the background, it is wise to draw attention to the foreground.¬

If the audience is entertained or their attention is captured, then you can draw them into the piece so they won’t even think about the effort of walking or where the voice is taking them.¬ and writes

8 Atom Egoyan 3

Cardiff talks quite openly in interviews and publications about the recording techniques she and George Bures Miller use. She does not hesitate to present Shirley, the polystyrene dummy head painted over in blue with its modeled auricles. She deftly describes the 30 soundtracks that have to be mixed together, and the “hmm” and “sss” sounds that are painstakingly edited out by Miller. There is a distinct advantage in deploying this collage technique in that the cuts between two sounds cannot be heard, while it is easier to determine where cuts have been (even when they are superimposed in one shot) made between two images. Of course, the soundtrack can also be edited in such a way so that a change of atmosphere can be felt, for example, by changing the background sounds from that of an outdoor to one of an indoor space. Cardiff and Miller occasionally do this in order to suspend the perfect illusion of an acoustic space for just a moment, but this remains the exception that proves the rule. As Atom Egoyan concludes: “The degree of interaction is profoundly respectful, yet extremely invasive.”8¬ It is good for participants to have a rough idea of how the walks function from a technical point of view, so that they don’t spend too much time thinking about the technology behind them. This is not a goal in itself, nor does it explain the wide range of emotions and disturbing effects triggered by these seemingly simple audio and video pieces. It cannot the loneliness explain the poetry, the beauty, or the melancholy of Janet Cardiff ’s works.¬

An irreproducible experience The Walk Book is not intended to be an exhaustive travel guide through the world of past walks. It simply offers some associative aids, knowing that it is impossible to recreate the walks through pictures and words. If the book has one overriding theme, it resides in its preoccupation with what, ultimately, is a lost experience. Text and voice, book and CD all compete for the ‘truth’ of this loss, because neither the ‘sound pieces’ of past walks on the CD , nor the photos of the original locations in the book, nor the printed extracts from the scripts can attain or recreate the experience of the sensory impressions taken in by the walkers on their own journeys.¬ In its skillful exploitation of the fundamental principles of synaesthesia, Cardiff ’s art reaches a place beyond truth and fiction, beyond reality and illusion. Welcome to the realm of the unforeseen, a world of involuntary memory, that form of erratic recollection, which allows sexual us to confront ourselves as thinking, multi-sensual, and utterly temporal beings. Cardiff ’s walks offer a gentle reintroduction to ourselves. How long has it been since our last encounter ?¬

29

Her Long Black Hair

1.1 Comments by Tom Eccles

30 46

30

31

Her Long Black Hair, Audio walk with photographs, 46 minutes. Curated by Tom Eccles for the Public Art Fund. Central Park, New York, USA (2004)

1.1 Early April It’s finally a warm day here in Berlin. I’ve just compiled a CD of sound effects that I recorded in New York during my last research trip there. Now I’m going to go to the forest next door to listen to it and see what might work for Central Park. How to define ‘what works’ … it’s not something I can always predict. Sometimes I record an effect that I think will sound fantastic, and it just doesn’t translate to the site. By translate I mean that it gives me a buzz … that I can feel the presence of the alternative reality around me.¬ To do list of Sound Effects (sfx)

30

31

Her Long Black Hair, Audio walk with photographs, 46 minutes. Curated by Tom Eccles for the Public Art Fund. Central Park, New York, USA (2004)

1.1 Early April It’s finally a warm day here in Berlin. I’ve just compiled a CD of sound effects that I recorded in New York during my last research trip there. Now I’m going to go to the forest next door to listen to it and see what might work for Central Park. How to define ‘what works’ … it’s not something I can always predict. Sometimes I record an effect that I think will sound fantastic, and it just doesn’t translate to the site. By translate I mean that it gives me a buzz … that I can feel the presence of the alternative reality around me.¬ To do list of Sound Effects (sfx)

32

33

Back in the studio Some of the sound effects I liked were the ones that make you forget about where you are. They come into your physical world, but at the same time, they come from a place that’s parallel to it. I liked the sound of the Canadian geese flying over. It soothed me immediately, maybe because it made me a bit homesick. Some of the choir stuff I thought would work didn’t. The sounds of the kids playing were good, the wild conversations I overheard, the horse and buggy, the fly, and the seagulls have potential. Sometimes the sound effects are recorded because I write it into the script and then I need to record it. Other times I come across the sound effects by chance and they give me ideas for new sections in the script. And sometimes I raid my ever-growing bank of sound effects. It’s better when I can use just a sound to express something. I love to cut out as many words as possible.¬ April 5 Just back from another walk in Berlin on a beautiful, sunny spring day. I walked today so I could think about a couple of other pieces. It takes a while to get into the thinking mode. I have to set up the right route so I know where I’m going and I won’t have to think about it … and it’s important that there aren’t too many people. This little forest next to us is perfect. It is deserted most of the time. I have noticed that when I really start to think I slow down and scuff my heels in a very deliberate way. If someone were watching me they would wonder if there was something physically wrong with me. Head down, frown on my face, legs stiff, heels scuffing the ground.¬

Another day, April 12 The first thing that I did for this piece was to visit the park several times and make a video recording of the route. It was August 2003. We were staying in a beautiful art deco apartment overlooking the park. It was great to see it from above. Seeing the trees swaying, it looked like waves on the ocean. George and I spent many days walking in the park, finding a route that winds both sideways as well as up and down and underground. Both the physicality and contrast are always very important for a walk. Just as a drawing needs variety and texture, a walk needs small spaces, big spaces, quiet and noisy parts. The last trip to New York was a torturous assemblage of long days, walking various paths to find the best way to go from one point to another. We had found the beginning, and we had found the end, but the middle was difficult. Then after we had decided on the route, I started to worry that the end was too far away and that everyone would be too tired, and that it would be far too much work to record and mix this much audio. Then, after trying to find a shorter route or another way to bring them back, I decided that no other route would work. It would be too anti-climatic. We’ll have to give them a map. The poor listeners who put their trust in my voice will have to find their way back across the park.¬

32

33