61 minute read

3.3 Tourism Action Plan

Malindi’s growth and prosperity has been anchored on tourism and the influx of both international and national visitors to its shores coming to experience the Swahili culture, sandy beaches and rich history as a stopover for Vasco da Gamma and home to Portuguese settlers. Over the past 20 years it has seen a significant and impactful decline in tourist numbers mostly due to safety and security concerns but also as a result of evolving trends in international travel demanding new types of experiences. The development of new beach destinations such as Watamu and further south in Mombasa increased competition for the already decreasing international tourist arrivals. This has led to the consequential decline in revenue, and the erosion of the Town’s urban fabric and character through a lack of investment in public and private building and infrastructure. Through the diagnostics assessment it has been shown that tourism remains a core potential offering for the Town. In fact, tourism has been identified as one of the main growth areas within the Kenyan economy and tourism growth and diversification is supported within the Vision 2030, the NSP and the ISUDP. It is also a key objective of the Kilifi County to increase tourism spend within the County through a tourism strategy implementation. The aim of the Tourism Action Plan (TAP) is to build on this strategic direction and develop a series of interventions that can advance the tourism offer within Malindi Municipality. It will therefore be important to base this plan on the comparative and competitive advantages of the Municipality that differentiate from other destinations within Kenya and focus on developing some of its unique characteristics such as the strong cultural and natural environments Malindi has to offer. At the same time, it would be critical to consider the customer base and move beyond just international tourists to include an offer for regional and local visitors that can sustain activity in between seasons. The interventions outlined within the TAP consider both ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ actions that will support the development of the tourism sector in a comprehensive manner.

Tourism

The purpose of the tourism action plan is to provide guidance on the measures and present ideas that should be considered to improve and enhance the local offer, however it does not replace the need for the development of a comprehensive strategy for the sector within Malindi. The latter would be essential to engage and mobilise stakeholders and investments to implement collectively. Figure 10 is an outline of the assessment of sector’s performance as this was developed during the Diagnostics phase. This was key to establish the basis for developing the proposed interventions.

Figure 10 - Tourism sector

Strengths

Malindi is a well-established tourist town that has good growth in the recent past. Local tours, guides and attractions - safaris, forests, water sports and marine activity. Airport with regular flights to Lamu and Nairobi.

Good opportunities and engagement with different social groups. Sectoral links - transport, agriculture, fishing, arts and leisure, real estate.

Weaknesses

Beach erosion from the development of tourist facilities.

Limited local training, few skilled hospitality workers from Malindi. Hotels and restaurants often use food from elsewhere.

Sector has contributed to the increase of undesirable activities.

Past growth attracted high level of urbanisation and immigration - falling incomes and lack of investment.

Challenges to address

The continued decay of the town's charm / aesthetic qualities from rapid urbanisation. Climate change effects - biodiversity, loss of tourist attractions / activities. Risk of over-dependence on the sector, where it is vulnerable to shocks.

Competition from neighbouring towns such as Watamu, and eco-friendly and high-quality tourism.

Malindi and Watamu marine parks constraints. Poor condition road areas and inadequate drainage. Unreliable electricity supply - energy demand gap.

For tourism sector interventions to be successful it will be critical to address existing challenges in a systematic and holistic way capturing both soft and hard initiatives.

Soft initiatives that can prepare and support local stakeholders in delivering an improved tourism offer

Infrastructure projects that improve the image of Malindi

Anchor projects that can generate the critical interest and highlight Malindi’s unique characteristics

Soft Initiatives:

› Establish working group with key representatives from the public sector, businesses and communities (consensus on offer through informed decision making - research into international best practice, coordination); › Marketing (linking key offer and developing a unique brand); › Skills (developing core competencies); › Develop events; › Engage community actively; › Regulations and incentives. Anchor Project Developing key public realm interventions premised around its core offering being the waterfront, cultural areas such as the Shella Village, and the natural coastal and dune areas up to Galana River. These are supported by rejuvenating the central area and creating a new nodal attraction (to the south) and physically linking these assets to promote a complete and connected range of varying experiences and visitor opportunities. These anchor projects will need to be sequenced and managed in order to ensure their success.

These include:

› The Waterfront and Jetty redevelopment; › The Shella Village regeneration; › The north shoreline nature based activities; and › Fishing village. Infrastructure Projects The perception of a city is mostly given by the images that visitors and residents alike retain when using and visiting it. The arrival experience, the ease of movement and security, cleanliness, quality of the public realm and access to supporting facilities are all elements concurring to deliver an attractive and vibrant urban holiday environment that stimulates repeat visits and creates an attractive “economic milieu” for investment and business.

› Waste; › Sanitation; › SuDS; › Road upgrade; › Transportation (water, road). These are described and considered in further detail in the following sections of this report. The TAP has been sequenced in such a way that the first priorities are aimed at improving the Town’s touristic offer, its safety and visual amenity in order to make it more attractive for visitors and residents as well as developing strong local capacity to maintain momentum and improve inclusivity in the delivery of the plan.

SOFT INITIATIVES

Establish working group with key representatives from the public sector, businesses and communities Tourism is a complex sector involving various stakeholders and players in delivering services as well as being affected by activities. It is imperative that from an early stage of planning all relevant stakeholders through the development of a working group / forum to ensure informed decision making in the design of tourism offer and effective levels of cooperation in its delivery. The purpose of the working group would be to raise awareness and knowledge of tourism amongst stakeholders that can influence development of the sector, its competitiveness and sustainability. Key actors include: › Public sector officials from the department of trade and industry, tourism, environment and transportation are critical to ensure integrated planning and effective implementation; › Private sector and tourism industry representatives and associations within

Malindi, such as local businesses active within the sector, local businesses seeking to develop activities in the sector, local businesses within the sector supply chain and financial investors.

It would be important to engage with alternative structures for private sector engagement such as property owners, when public land availability to support

the tourism sector is an issue and requires access to land; › Community groups particularly from areas affected positively or negatively from tourism and NGOs and other civil society interest groups. Additionally, it would be important to maintain close links at national level with key ministries and agencies such as the Kenya Tourism Fund and Kenya Airports Authority who are extending the Malindi airport to international standards.

Strategy and Marketing In a highly competitive global market, it is imperative to create a unique tourism offer that differentiates itself from the rest. Malindi is unique in cultural and historic context within Kenya combined with its abundant natural resources both on the coast, within the core town area and further inland.

A first step would be to develop a longterm strategy that links Malindi’s offer with a unique brand and translates into tangible actions, including focusing infrastructure requirements and tourism development areas. To achieve this, it would be necessary to understand current tourism flows and performance within the region and further afield, the type and scale of target markets and Malindi’s potential to capture and increase tourist arrivals. While international tourism is seen as a target market, domestic tourism can also become an important source of considerable activity covering different seasons and providing continuity throughout the year. With a clear strategy in place and development of a unique brand for Malindi it would be easier to strengthen media engagement and develop a network of national and international partners that will provide a platform to market the local offer. Image building events such as creation of festivals could provide a starting point to attract attention, as will the development and opening of landmark developments which provide added value to the overall offer.

Training Tourism is a labour-intensive activity which focuses on customer service skills. The higher the standard of the services provided, the better the tourist’s experience, thus education and training is of paramount importance. This does not only apply to services directly related to tourism such as hotels and guest houses, but also within the supply chain such as trade, transportation and recreation, both active and passive.

Regulations and incentives Two key requirements for the implementation of a successful tourism strategy are: policy and regulations to promote appropriate tourism practices and provision of incentives that can attract and guide development activity. Tourism policy should take full account of socio-cultural, environmental and economic impacts as well as resource management issues such as water, waste and energy. Equally important is the consideration of potential climate change impacts and how resilience and risk management can be built in particularly for vulnerable areas such as coastal areas.

Ensuring good coordination and appropriate incentives can nurture successful public and private sector partnerships which is important for property/area restoration, regeneration and new developments. The local government should provide a clear framework to promote this type of engagement which is necessary in cases where finance and land is scarce.

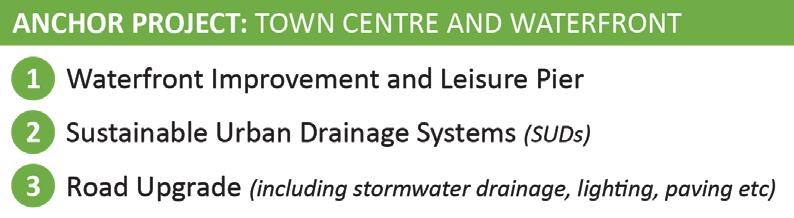

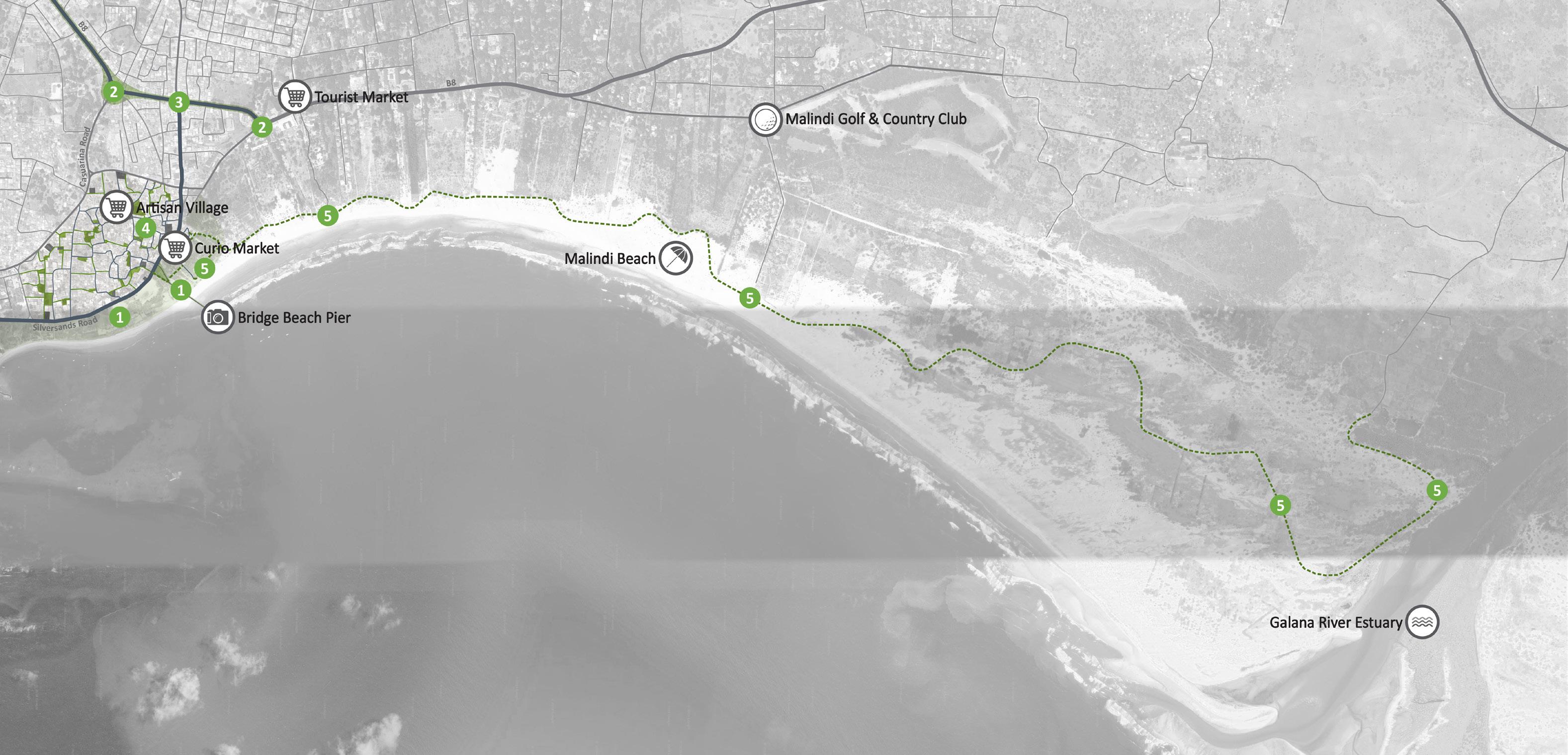

ANCHOR PROJECT: TOWN CENTRE & WATERFRONT

These tourism-based anchor projects include the upgrading of the waterfront area around the existing jetty which is currently the subject of a World Bank (WB) funded initiative to introduce new public amenities and facilities. The proposals within TAP, whilst leveraging, acknowledging and integrating the WB funded infrastructure developments, take a broader view with regards to climate resilient initiatives (mitigations for sea level rise for example) and linking the waterfront with the other activity zones within the Town such as Shella Village, the central area, the northern shoreline and even south to Mayungu Beach. The Shella Village proposals are to improve its touristic potential through better access and circulation linking it to the wider area with targeted signage and upgraded streets and public realm. This will open up opportunities for the areas cultural and artisanal assets to be developed and exposed to a wider visitor audience. This will also introduce opportunities for local tours, artisan workshops & demonstrations, as well as homestays and accommodation focused on women empowerment and job creation within the local community. A village cooperative can be set up in conjunction with the Municipality to manage the upgrading and future operations within the village as well as the neighbouring areas. The TAP also identifies the opportunities within the more natural areas and landscapes of the northern shoreline which stretch up to the Galana River. This is considered to be an “untapped” natural resource which when sensitively developed and well managed can become a significant added attraction to the Malindi tourism offer. Low impact, eco-friendly facilities have been proposed which will create greater access into the area whilst encouraging visitors to experience the natural coastal beauty in terms of landscape, views, flora and fauna. To the south of Malindi at Mayungu Beach it is proposed to develop a small destination facility anchored around the fishing village activities and offering visitors an eco-friendly adventure experience based on non-motorised water sports, food and beverages, low cost accommodation, arts and crafts and marine educational zones.

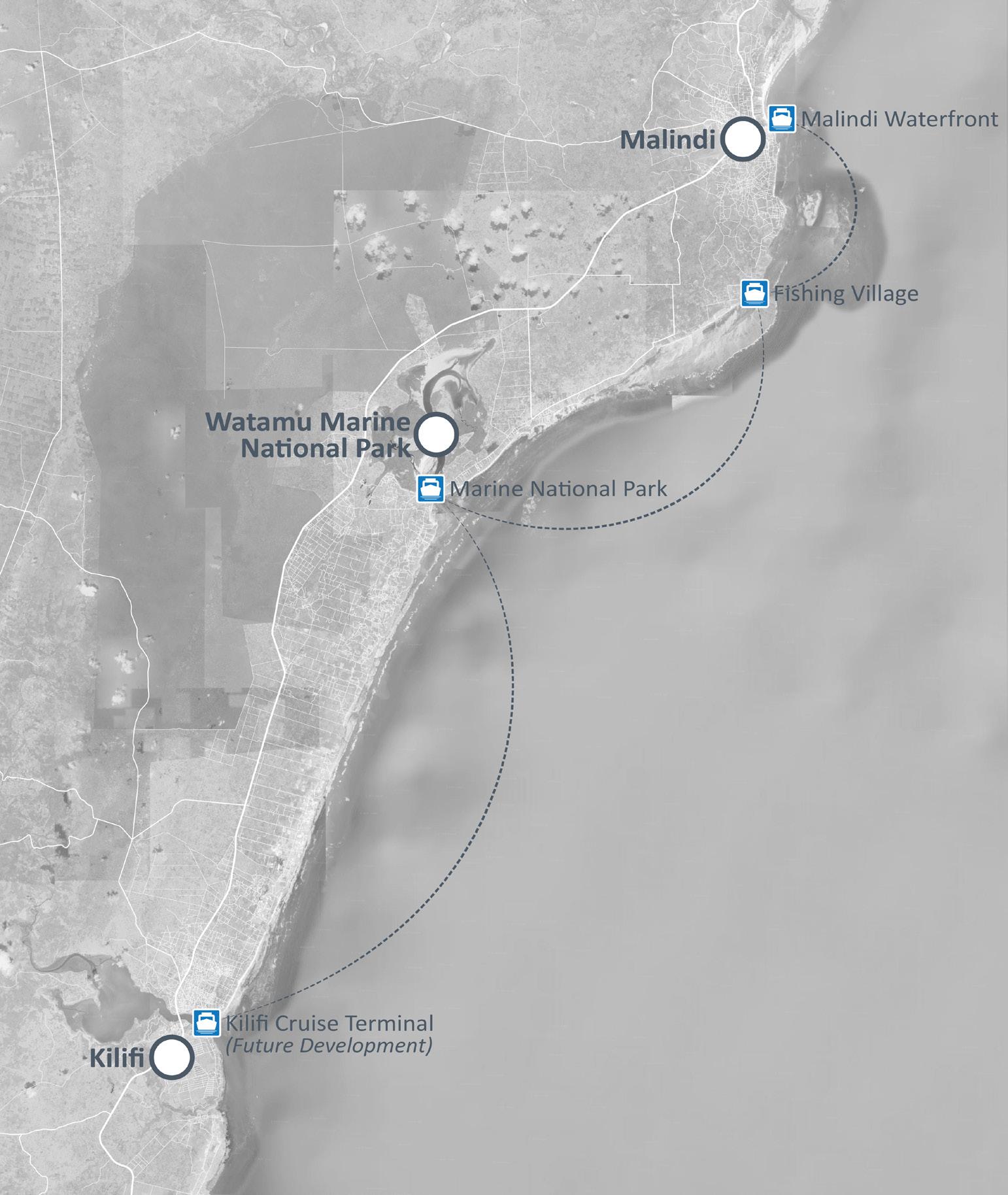

Figure 11 - Town Centre and Waterfront

Figure 12 - Town Centre and Waterfront Detail Study

ANCHOR PROJECT: TOWN CENTRE & WATERFRONT

Waterfront Improvements and Leisure Pier 1

Figure 13 - Waterfront Improvements and Leisure Pier

TOWN CENTRE & WATERFRONT Waterfront Improvements and Leisure Pier 1

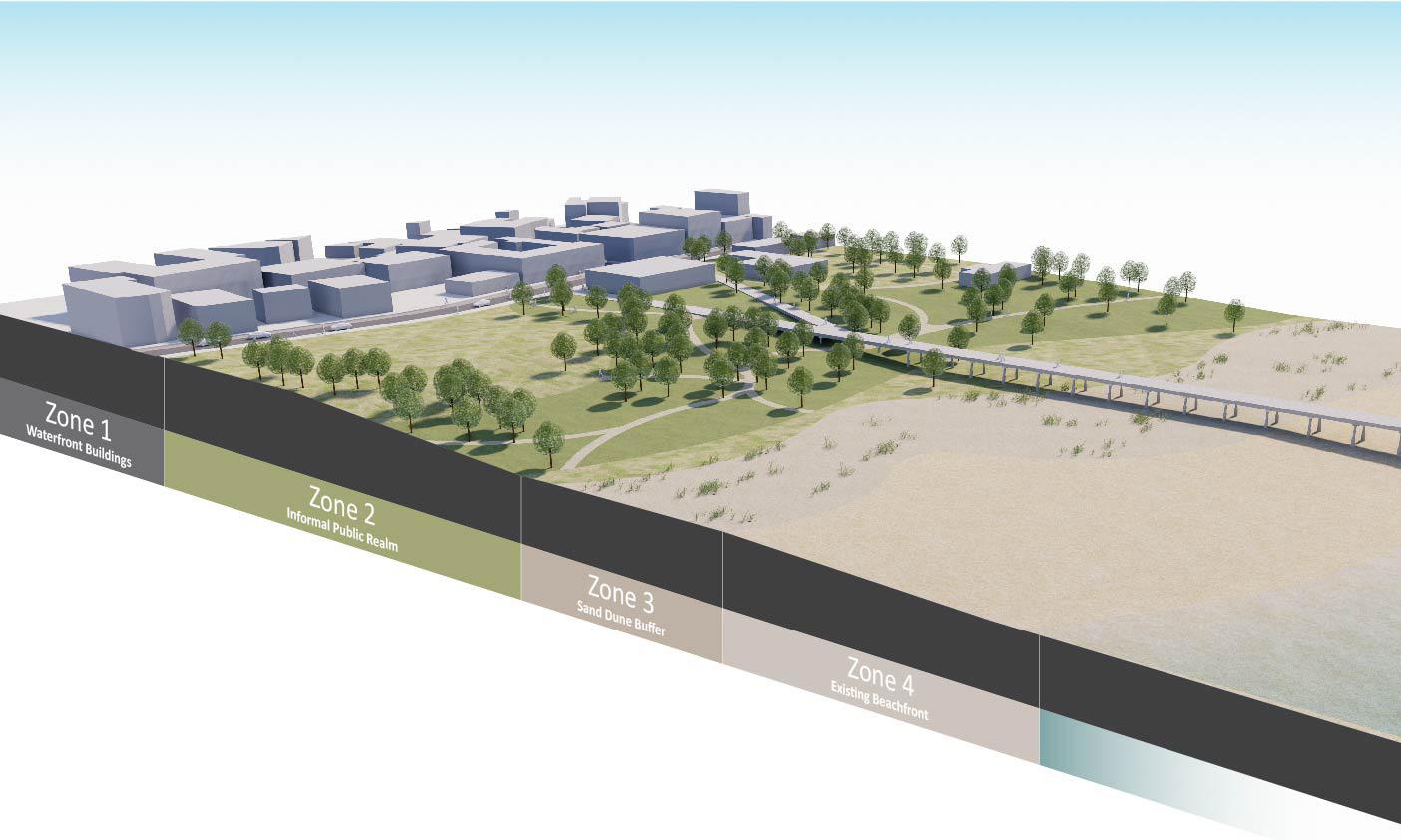

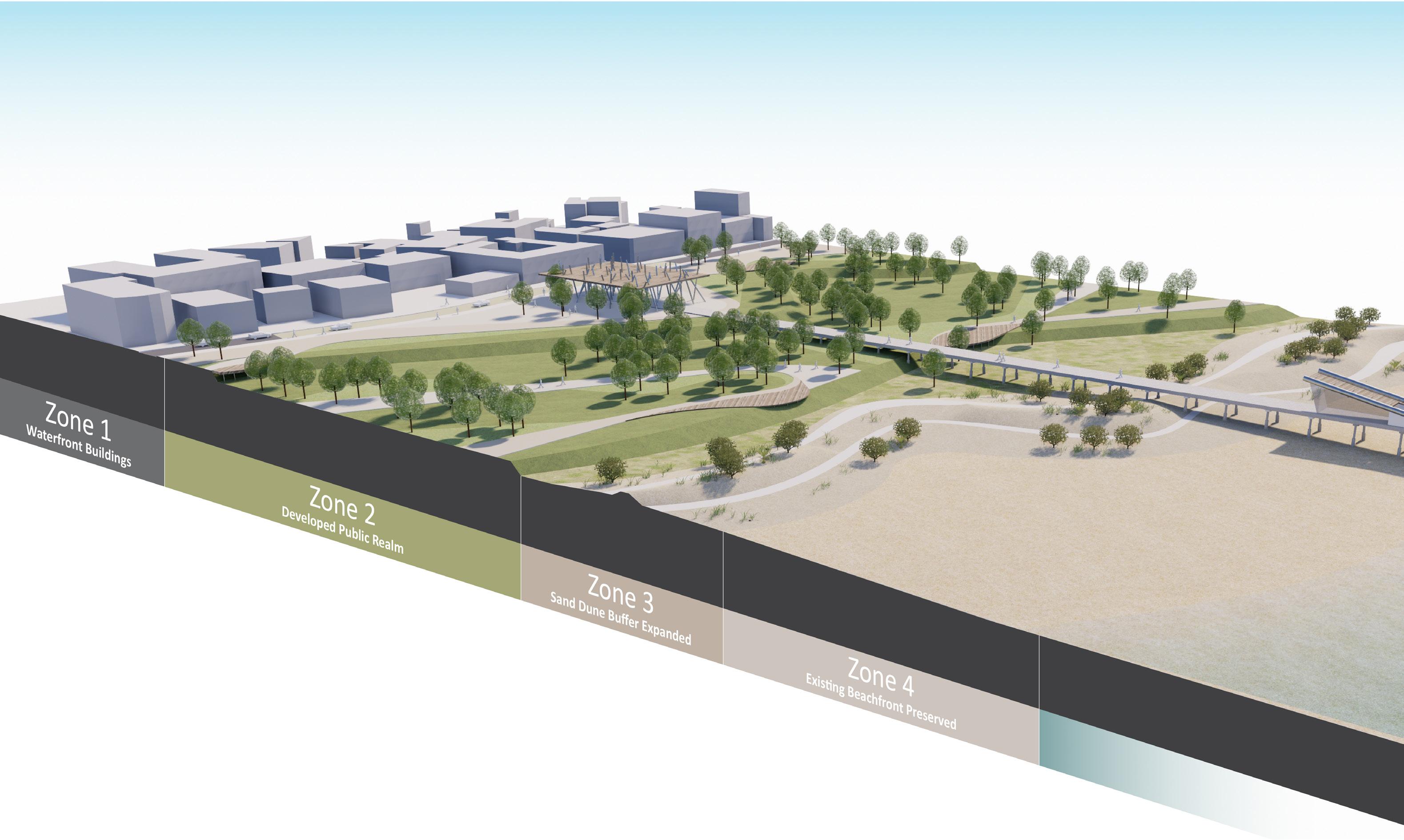

The central stretch of the Malindi’s waterfront is the first regeneration opportunity which includes the transformation and upgrade of both the pier and its interface with the town. The proposal takes in account local business needs, space and impact of the climate crisis, namely sea level rise and potential storm surge effects. The waterfront will be “iterated” by a series of pedestrian boardwalks stretching between the Vasco da Gama Pillar and the Galana river to the North. The proposals include a new set of pedestrian links connecting open spaces, light structures (shelters, kiosks, rest points, etc) sport, social and leisure spaces in the urban section. The arrangements of such places are sensibly located away from the ecologically sensitive dune which will be protected and enhanced to maintain and improve its dual function of biodiversity bank and coastal protection zone. In the central (urban) portion of the coast, the dune should be remodelled, and its heights increased to help shelter Malindi from storm surges. In doing so, new spaces can be carved out and developed with low cost infrastructure to both expedite development and minimise cost of reconstruction in case of extreme events. The pier should also undergo enhancement and redevelopment in order to become a more welcoming landmark and unique tourist attraction for Malindi. It can be used for multiple purposes and offerings, for example, a unique event space suspended on the sea and still functioning partially as a fishing pier. It will also act as the main maritime stop for the LamuMombasa sea link. A new, contemporary market structure is to be located on the waterfront promenade where both fish trade, learning and fish-based restaurants can be co-located with a brand-new visitor centre - the first destination for tourists in Malindi.

All these proposals should be integrated with the existing World Bank funded projects being undertaken within the waterfront area. It is recommended that the existing overall design of the area should be further validated in order to ensure that it is climate resilient, functional and cost effective in its implementation. The pier and the new proposed fish market structure interface with the village. This is the original Old Town in Malindi where a fishing and artisan community has settled over the centuries. The Old Town has been left in disrepair with poor facilities, infrastructure and public realm. The maze of old buildings, some monuments and landmarks are not on the visitor map. Our proposal fully integrates both the renewed waterfront with this historic and rich part of town to enable both visitors and local business to benefit from the culture, craftmanship and resources that Malindi has to offer. More details about the Shella Village strategy are included in the section: TOWN CENTRE & WATERFRONT Shella Artisan Village, Curio Market 4.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms Potential Funding

› Ensure design integration and validation with WB project › Pier - Pier revamp including maritime facilities for Lamu-

Mombasa sea link › Pier - Fish market re-development into Visitor centre,

Contemporary fish market, retail F&B › Pier - Integration of urban storm water drainage facility › WF - Integration of paths, kiosks, play areas and other facilities visitor facilities (small pocket car parking) between

Vasco Da Gama

Pillar and Galana

River mouth › Natural dunes remodeling and increase of height › KES 52,650,000 › State of the art and attractive waterfront destination › Better fishing supporting facilities › New tourist facility (visitor centre) › High-quality sport and relax spaces › Protection of biodiversity › New retail spaces › Public Authority › Potential for concession of leased areas to Private operator › Design and Build,

Operate & Maintain (DBOM) approach › Possible extension to WB funded project to incorporate UEP proposals › Public Realm &

Utilities by LPA › Following completion: additional revenue from leasable spaces, parking, temporary events, etc

Challenges Data Gaps Time Frame Phasing Project Priority

› May require some land acquisition › Integration with ongoing project › Funding › Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies › Actual storm surge levels, flood risk › Short term › Multi-phase › Urban Development Proposals supporting Economic Growth › Public zones by

Municipality (i.e.: cleaning, etc) › Leased spaces / facilities by private operator

Operations & Maintenance

Malindi Pier Zone

Existing pier extended and redesigned with improved high-quality finishes, viewing platforms and attractive design. The design draws inspiration from the traditional fisherman’s boat and sand dunes and is respectful of the local surrounding. It includes an amphitheatre for small performances, a seaside market and highquality sitting and recreational spaces.

Traditional fishing boat Amphitheatre inspired by fishing boat

Amphitheatre/viewing platform towards the sea Market space towards the city pier

Precedents images

Performance and Gathering Spaces Viewing Pavilions Piers Seating Areas

Figure 14 - Malindi Pier Zone - current situation and key areas. The waterfront zones have developed in an organic way leading to poor space planning and poor facilities.

Figure 15 - Malindi Pier Zone - proposed approach. The proposal includes measures to re-develop the pier, Shella village and adapt the natural coastal zone to climate change and sea level rise. These measures should be incorporated in to the current WB waterfront projects.

Impact of Sea Level Rise Climate change is going to affect Malindi in many ways. Sea level rise in coastal locations is a key issue, particularly during storm surges. The following three diagrams illustrate conceptually the possible impacts that climate change might have on a sample study area around the Malindi pier. Further studies are required to detail the best solution and prepare for extreme events.

Current sea level and coastal transect illustrating both functional and ecological component of the waterfront in the urban section. The conceptual illustration includes the current waterfront proposals promoted by the WB.

Simulation of sea level rise based on expert advice (i.e.: +1m by 2050)

Simulation of extreme event combination of new sea level and storm surge. In such cases the sea could affect and damage the properties being currently developed in the area around the Malindi pier. It is recommended that a more detailed study and review of the on-going projects are conducted to ensure climatic resilience of the new facilities.

Figure 16 - Waterfront Zones

The identification of the Waterfront Zones acknowledges the project designs and implementation being undertaken by WB. However, it is recommended that all upgrading and redevelopment of the waterfront should ensure it is integrated and connected to the adjoining Shella Village as well as the coastal areas to the north and south as proposed within the UEP.

Case Study: Geelong Waterfront Leisure activities - Victoria, Australia Waterfront Geelong is a vibrant cafes, activities and public art has seen recreational and tourism precinct Waterfront Geelong become an iconic located on Corio Bay. It’s unique North location for the local community and facing aspect, range of restaurants, visitors to the region. Case Study: East Side Coastal Resiliency Project - New York The East Side Coastal Resiliency (ESCR) at reducing flood risk due to coastal Project is a coastal protection initiative, storms and sea level rise on Manhattan’s jointly funded by the City of New York East Side from East 25th Street to and the federal government, aimed Montgomery Street.

ANCHOR PROJECT: TOWN CENTRE & WATERFRONT

Figure 17 - Malindi High Street and SuDS

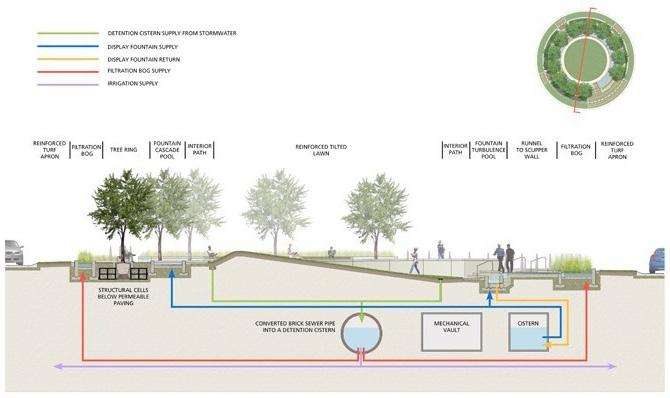

TOWN CENTRE & WATERFRONT Malindi High Street and Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SuDS) 2

Malindi High Street: re-design of the street to address the local flooding issue affecting the area around the round-about. The proposal considers improved drainage and streetscape. Malindi High Street is the first part of town that visitors experience on arrival in Malindi (including from the airport). The High street is also one of thriving spots of town where businesses, stalls and markets regularly locate. From here, side streets branch-off to both north and south leading to the new market area and the bus station. Further down a roundabout split the High Street in two main directions, eastbound toward the waterfront and southbound toward Casuarina Road and later on, along the southern coast. The High Street in its current configuration is broadly unregimented with poor space for pedestrian and, occasionally, unsafe spaces for business. The overall impression on arrival is less attractive that what it could be.

The High Street area around the roundabout, for a radius of 400m, is also affected by localised floods. This is understood as being one of the most pressing issues affecting the local livelihood of the businesses as when this area floods, trade stops with consequent loss in income. As such the High Street development strategy seeks to address both the structure and space articulation issue and overall perception of the high street as well as minimise the exposure to flood. Two strategies have been adopted: a. Re-structure of the high street spaces to allow for more orderly and safe spaces for both pedestrians and businesses. This it is expected to allow for better, greener features to be fully integrated. The proposed layout includes re-arrangement of spaces fronting the shops, and reduction of on-street car parking to make room for people and pop-up stalls.

Car parking can be re-located in the back lanes, fully integrated with business operations where possible. A new green central reservation in proximity of the roundabout is introduced (see detail at b below); b. An innovative and holistic approach to storm-water surface drainage is proposed, this is known as Sustainable Urban Drainage system and entails taking a strategic approach to fully integrated green infrastructure within the new High Street layout to better capture and convey storm water and make fully integrated systems with other neighbouring open spaces in the area surrounding the high street. In this case the central space of the roundabout itself is transformed into a drainage dry pond and other open space plots nearby can become receptors of such storm water (for the detailed approach see SuDS section opposite).

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms Potential Funding

› Upgraded streetscape and activities zones layout › Integration of

Sustainable

Urban Drainage facilities › Integration of more greenery and permeable paved surfaces › KES 88,630,000 › Tackling localised flash flooding › Improved and safer trade zones › Enhanced

Malindi’s image / brand › Better frontage and footfall › Climate resilient street › Public Authority or a mix Public Private such as Business

Improvement

District (BID) › DBOM › Public Funding

Challenges Data Gaps Time Frame Phasing Project Priority

› May require some land acquisition › Funding › Ground infiltration rates (low) › Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies › Impact on road traffic › Short term › Multi-phase › Urban Development Proposals supporting Economic Growth › Municipality (i.e.: cleaning, etc)

Operations & Maintenance

Figure 18 - As existing arrangement of the main roundabout

Informal/unplanned use of space Existing roundabout Petrol Station

Access to petrol station too close to roundabout causing traffic congestion.

Figure 19 - Proposed view of the roundabout showing SuDS elements and some other public realm enhancements Improved roundabout design to better accommodate rainwater runoff Petrol Station

A new green central reservation in proximity of the roundabout to better channel excess rainwater

Informal but planned use of footway space Dedicated cycle lanes Dedicated bus /matatu stops

Case Study: Uptown Water Circle, Normal - Illinois A roundabout with a park at its centre is used to improve traffic flow and create a public gathering space. The circle also serves as a gateway to Normal for those arriving through its new Multimodal Centre. Sustainable stormwater management (SuDS) was implemented by collecting and reusing urban runoff from two of the radial streets in a bog and fountain feature. The sound of the flowing water also helps to make traffic noise less noticeable.

Case Study: Bourke Street - Sydney, Australia Bourke Street is Sydney’s first large-scale bidirectional, separated cycle track, and is part of the city’s strategy to increase the quality and scope of the cycle network in the Sydney area. The 3.4km project is an upgrade of an existing cycle route connecting Cowper Wharf Road in Woolloomooloo Bay to Phillip Street, Waterloo. The design provides improved safety and amenities for cyclists and pedestrians. Case Study: 21st Street - Paso Robles, USA Early in the design process, team members recognised the overlapping benefits of designing for safety, environmental sustainability, and high-quality public spaces. The newly reconfigured corridor transformed five city blocks by calming traffic, improving cycle and pedestrian mobility, and introducing a natural drainage into the transportation network, increasing groundwater recharge.

ANCHOR PROJECT: TOWN CENTRE & WATERFRONT

Road Upgrade 3

Figure 20 - Road Upgrade

ANCHOR PROJECT: TOWN CENTRE & WATERFRONT

Shella Artisan Village, Curio Market 4

Figure 21 - Shella Artisan Village, Curio Market

Further inland, Shella Village will offer an alternative to the waterfront buzz and leisure activities with an injection of traditional crafting and cultural discovery which will elevate the local identity of the area. The village is currently suffering from unmanaged public realm, poor-quality property maintenance and complicated access. As many businesses and workshops are already located here, the community would substantially benefit from an integrated urban regeneration strategy. The necessary upgrade of the public realm, derelict open spaces, crumbling buildings and streets winding through the intricate and historic urban fabric of the old town, will facilitate the exploration of “Shella Old Town”. In any urban revitalisation project community development and cohesion and the provision of appropriate measures for existing and future residents and businesses is a central focus. In the case of Shella village safeguarding the existing community is of paramount importance. › To enable creation of economic opportunities in line with the wider development trends in the area (e.g. lodging, food, activities) through meaningful employment for community members; › To provide means of revitalising intangible or tangible culture (e.g. cultural events, local handicrafts, traditional practices) through making them tourism products. Community led development provides local people with the opportunity to influence and become involved in developing their own communities. It brings about improvements in local social, recreational, environmental and historic amenities for both locals and visitors alike and creates an environmentally sensitive and locally controlled tourism sector, which develops business and employment opportunities for local people, and keeps money within the local economy. It is important that any interventions and projects implemented are carefully designed and managed to avoid any negative impacts on the local community such as unrestrained movement of tourists. Good design parameters developed in collaboration with local residents, should ensure that access to private quarters of Shella village is restricted and at the same time allow for an authentic experience for visitors. Potential community led projects:

› Development of outpost of museums or oral history museum. Community operated museum in collaboration with museums around the country. It would serve as decentralised facility, presenting a limited collection as an introduction to national history and culture and specifically preserve the historic Swahili culture of the Kenyan and showcase past and current livelihoods linked to fishing activities and trade; › Community operated and managed hotel. A business venture favoured by rural communities to generate income, preserve cultural and environmental assets and control tourism. Shella Town could provide for this type of activity benefiting from the historic urban environment and offering an original local experience in a market that concentrates on mainly high-end modern hotels or 2 and 3 star uninspiring accommodation; › Cultural centre. In collaboration with external partners the development of a centre that is operated by the community and showcases arts and crafts from around the country as well as hosting art performances at specific times; › Food and beverage. Central to any travel is a local culinary experience. There are currently few examples of local traditional restaurants accessible to tourists; › Showcasing local products. Artisan workshops, market stalls, artists and makers of all backgrounds will consolidate and expand their businesses to welcome more visitors and expand the “Malindi crafting” brand nationally and potentially internationally, building on existing successes such as the sandal making cooperative.

Figure 22 - Shella Artisan Village, Curio Market Proposals

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms Potential Funding

› Development of Public Realm including, paving of streets and sidewalks › Wayfinding and lighting › Plazas an parks redevelopment › Key historical / strategic buildings repurposing and refurbishment (excluded from costing and proposals - subject to feasibility study) › KES 1.12 billion › Improved access and perception › Better and safe pedestrian facilities for residents, businesses and tourists alike › Attraction of footfall supporting an authentic neighbourhood and experiences › Improved land value › Potential for attracting investments › Public Authority or a mix Public Private such as Business

Improvement

District (BID) › DBOM › Public Realm &

Utilities by Local

Authority › IFIs › Value capture following completion: levies on properties and temporary events

Challenges Data Gaps Time Frame Phasing Project Priority

› May require some land acquisition › Would increase noise and air pollution due to increased motorised vehicles › Funding › Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies › Impact of road traffic due to this new road › Immediate term › Multi-phase › Urban Development

Proposals supporting

Economic Growth › Public zones by

Municipality (i.e.: cleaning, etc)

Operations & Maintenance Case Study: Andaman Discoveries - Thailand

One of the most referenced successful examples of community led tourism development. The project started at the back of the 2004 Tsunami aftermath developing projects for the community. These included over 120 projects in 12 Tsunami-affected communities including: › Community-based tourism development and marketing; › Making local products and crafts; › Youth-led conservation work and environmental education; › Traditional Thai music lessons; › Waste management and recycling; › Community centre to coordinate activities.

Case Study: Mdina - Malta

Mdina is the historic quarter of the Town of Rabat in Malta. Mdina has served as the island’s capital from antiquity to the medieval period and owes it urban pattern of narrow, winding streets to its Arabic influence. Its human scale, car free centre and tranquillity has gained it the nickname of ‘the Silent City’. Following gradual restoration of its buildings and public spaces, Mdina has become one of Malta’s major tourist attractions, hosting about 750,000 tourists a year. Palazzos (ancient aristocratic homes) have been restored to welcome visitors which bring the ancient quarter to life. Some craft shops and traditional food venues and restaurant complete the visitor experience. Case Study: Craft villages - Vietnam The term ‘craft village’ is widely used in Vietnam to identify villages whose key activity is the craft production with master artisans and households of traditional craft - often the tradition of the family. Some of these traditional handicraft villages have become famous in the tourism circuit, namely Bat Trang for the ceramic and porcelain production (see photos), Doi Drum, Non Nuoc for stone carving, etc. Today the term “Craft tourism” is becoming well-known and it refers to tourist visiting craft and artisanal destinations. This type of tourism contributes to the preservation and the development of craft villages in a sustainable way as it both supports local products expansion and the preservation and promotion of the cultural values of these villages. From an economic perspective, the development of craft tourism supports local employment, increases community income, and contributes to poverty alleviation. Vietnam’s handicraft villages have become a reason of pride and income earning tool with products exported to more than 100 markets in the world (Hien 2012). From a cultural perspective, crafts become important factor to raise ethnic pride and maintain and protect cultural practices (Kerr 1995).

ANCHOR PROJECT: TOWN CENTRE & WATERFRONT

Nature Based Activities 5

Figure 23 - Nature Based Activities

Building on the existing strengths of the northern section of the coast, and connected to the central zone, a series of understated promenades on boardwalks will be sensitively weaved through dunes, woodlands and shrubs leading to activities nodes. Picnic areas, leisure/ adventure zones, pop-up sculptures and some viewing tower will be dotted along the trails and act as local landmarks. Links from the National Road down to the coast are also proposed as part of this comprehensive pedestrian network. These facilities are expected to both enhance pedestrian, beach side access to the Galana River mouth and stimulate the village socio-economic development.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms Potential Funding

› Boardwalk promenades, activities nodes, picnic areas, leisure / adventure zones, pop-up sculptures and some viewing tower (subject to feasibility) › Pedestrian access to the coastal zone from hinterland (including small pocket car parking) › KES 2.65 billion › Better and safe pedestrian access to the wider river zone › Formalised opportunities for local businesses › Attract international visitors › Additional open natural space › Diversification of the Malindi tourist experience › Public Authority or a mix Public Private such as BID › DBOM › Local Authority,

IFIs, › Central government › Value capture following completion: levies, leases on temporary events and local businesses

Challenges Data Gaps Time Frame Phasing Project Priority

› May require some minimal land acquisition › Funding › Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies › Site surveys and land ownership › Short-medium term › Multi-phase › Urban Development

Proposals supporting

Economic Growth › Public zones by

Municipality (i.e.: cleaning, etc)

Operations & Maintenance

INFRASTRUCTURE INTERVENTIONS

The infrastructure interventions outlined are proposed to take existing negative impacts within the Municipality as solid waste (littering and dumping) and sanitation (lack of sewer network) and exploiting them to not only improve Malindi’s health and amenity but also to create value chain opportunities through formalising management and implementation measures. The following proposals identify the opportunities for solid waste management and recycling to be formally introduced at Municipal level thereby creating a waste stream from which potential recycling and waste disposal can be leveraged as commercial investment opportunities. This is a three-step process: › Managed waste collection throughout the Municipality; › Formal operation of a land fill site; › Introduction of a recycling facility. The introduction of a waste-water treatment plant is essential to the Town’s future growth and its citizens health. As dumping of sewerage and sludge is currently undertaken at the existing solid waste dump site it is proposed that this site be utilised in a multi-functional manner in order to optimise on infrastructure and operational aspects of the overall facility. Linked to this is the value chain opportunity for the sludge to briquettes, fertilisers and feed mill plant to be located on the same site to reduce travel and local impacts caused by extraneous traffic and activity Finally, the introduction of solar street lighting will improve the security of Malindi’s streets, particularly within the central and waterfront areas, and encourage night time trading and social activities through improved safety and security.

Figure 24 - Infrastructure Projects

INFRASTRUCTURE INTERVENTIONS Formalise Waste Collection and Segregation 1

Formalising and integrating the role of the informal sector into Malindi Town’s waste management system. Introducing source segregation in households and commercial establishments. Encouraging Community Based Organisations to form operational partnerships with private or public waste collectors. › Identifying roles in waste management; › Maintain dialogue and interaction; › Maintaining employment. Develop and implement a smart app / text message system to facilitate town-wide waste collection and segregation. The facility will need to provide appropriate amenities for the truck drivers and operators, including vehicle maintenance facilities, toilets, and shops.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms

› Formalising the

Informal Waste

Collection Services › ~$50 - 100k USD annually › ~$50k to develop and implement smart app for town-wide waste collection › Funding: Internationally

Funded Institute (IFI) /

Donor Finance › Reduced wild dumping of waste and improved sanitation › Provides an increased level of service and engages community and private sector › Improves sanitation and flood and surface water management ability. › Formal employment for waste pickers with adequate wages and health and safety training › Involvement of waste picker organisations to provide support and supervision › Better working conditions for waste sorters › More efficient segregation of recyclables › Higher quality materials which can be sold to recycling brokers › Improved understanding of waste collection and collection days, etc › Introduction of Private

Public Partnership (PPP) into waste collection effort › Support from Non

Governmental

Organisations (NGOs), community groups, waste pickers › Employment and training by Malindi

Municipality or private entity / Community

Based Organisations (CBOs) › Funding for Personal

Protective Equipment (PPE), collection carts, training and wages for the CBOs, etc › Maintenance responsibility of

Municipal Government

Challenges

› Non-biodegradable waste is left on the streets as litter › No formal recycling in place › Lack of health and safety systems in place for collecting and sorting waste by informal sector (waste pickers) › Not all residents have smart phones › Provide adequate training and support systems › Convert existing infrastructure › Launch public awareness campaign › Develop smart app system › Short-term / Ongoing

Data Gaps Time Frame

Case Study: Developing an Integrated Waste Management System12 (Kampala, Uganda) In Kampala, Uganda, the development sector (predominately the landfill pickers of an integrated waste system was and CBOs) as part of an integrated prompted by the lack of formalisation approach across the waste management in the waste sector. Much of the waste value chain. was disposed informally by dumping, burning or burying. Only 55% of the city’s solid waste was officially collected and transported to the city’s landfill by the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA). Several standalone CBO existed offering financial incentives to informal settlements for the collection of recyclable materials, however, the KCCA were not aware of many of these organisations. As a result of the Integrated Waste Management System, a strategy was developed to identify, inform and consult stakeholders; clear objectives and measurable targets for education and knowledge sharing were created; activities were undertaken to educate waste pickers; a new contract was developed to ensure that new landfill operators would formally integrate registered waste pickers; and CBOs The KCCA developed a new Kampala were encouraged to form partnerships City Integrated Waste Management with the KCCA in order make the System System to improve the collection, more integrated. transportation and treatment of the city’s waste and incorporate the informal

INFRASTRUCTURE INTERVENTIONS Remediation of Existing Landfill 1

Remediation and engineering into a sanitary landfill of the existing dumpsite at Casuarina approximately 10km south of Malindi. › Determine level of investment and secure funding (IFI, grant, PPP or direct by government); › Appoint private contractors to remediate and clean the site; › Engage with informal sector and CBOs. Construct and install two barrier lining and leachate and landfill gas collection and treatment systems within the new engineered landfill cells. Construct a concrete slab on the remediated landfill to undertake recycling operations.

Case Study: Remediation of open dumpsites in South Asia (What a Waste 2.0, World Bank Group, 2018) Open dumping is common in South constructing new engineered disposal Asia with most open dumpsites lacking sites that can serve a number of islands any form of leachate collection and (World Bank 2017). treatment, landfill gas collection and many also lack any form of liner. However, the remediation of existing dumpsites and the construction of new engineered landfills is underway with the newer official and well operated landfills generally being privately operated. The Maldives is currently mitigating dumping of its waste by improving waste collection systems and

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms

› Construction of engineered landfill and excavation and haulage of existing dumped material into new cells › USD $1 million to USD $4 million

Funding: IFI / Donor Finance › Improved ground and water quality around

Casaurina › Reduces methane production in the landfill › Improves local air quality › Provides employment › Provision of a sanitary and engineered landfill for future management of residual waste › Opportunity for collaboration with private sector

› Construction of concrete slab on remediated area › USD $250k to USD $1 million › Reduced ground and water pollution around

Casaurina › Provides area for formalised recycling and waste composting to take place › Creating employment › Opportunity for collaboration with private sector

Challenges

› Malindi has waste being dumped on the road, uncontrolled fires and pollution of surrounding water bodies › No formal means of treating and disposing of waste › Need to be mindful of employment and social impacts on informal sector that live and work on the existing dumpsite › Obtain funding for remediation infrastructure › Obtain funding for construction of new engineered landfill cells › Construction of new engineered landfill cells: Short-term › Removal of historical ‘dumped’ waste into new landfill cells:

Short-term › Construction of new concrete slab: Short-term

Data Gaps Time Frame

INFRASTRUCTURE INTERVENTIONS Development of Recycling and Treatment Infrastructure 1

Developing basic recycling infrastructure. Construction of a simple material recycling facility (MRF) at the remediated Casaurina landfill to enable informal sector to recycle safely and increase waste awareness and education.

› Determine level of investment and secure funding (IFI, grant, PPP or direct by government); › Engage with informal sector and CBOs (existing Casaurina dumpsite pickers, etc). Development of composting facility for managing organic waste and fish processing waste. › Develop mechanism for implementing source segregation of organic waste (through waste collection and simple MRF); › Develop mechanism for developing in-vessel composting facility (PPP, funding, grants or direct by government) and identify opportunities / impacts of Construction Design

Management (CDM) Develop the facility and secure / ensure end-markets are available - for recyclate and for compost on agricultural land. Develop mechanisms for payment / fees between collectors, municipality and pickers.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits)

› MRF › USD $250k to $750k

Funding: IFI / Donor Finance › Improve community waste awareness › Provides an increased level of service and engages community and private sector › Formalises the sorting process › Employs informal waste pickers › Secures markets to sell the recovered outputs › Provide a safe and regulated environment for waste sorting › Recover and sell recyclable material (e.g. plastics, paper, glass, metals) and receive revenue from sales.

› In-vessel composting facility › USD $250k to $500k

Funding: IFI / Donor Finance › Reduced wild dumping of waste and improved sanitation › Can produce usable fertiliser for agriculture › Reduces methane production in the landfill › Diverts organic waste from landfill › Improves local air quality › Provides a sustainable treatment method for fish processing waste Delivery Mechanisms

› Opportunity for private or public sector to collaborate with informal sector › Would enable wide spread source segregation to be implemented across the Town › Collaboration with recycling facilities to secure markets: locally in Malindi - paper / card and possibly plastics; nationally in Nairobi or

Mombasa - metals and plastics

› Opportunity for private or public sector to collaborate with informal sector › Would enable wide spread source segregation to be implemented › Collaboration with farmers to secure local end markets › Collaboration with fish processors to provide treatment for wastes

Challenges

› Malindi has waste being dumped on the road, uncontrolled fires and pollution of surrounding water bodies. › No formal means of treating and disposing of waste. › Limited formal collection mechanisms › Secure markets for recyclates and land / area for the treatment facilities › Obtain funding for treatment infrastructures › Formalise collection process so that waste is sorted and transported to the appropriate facility › MRF: Short / medium-term › In-vessel composting Facility:

Short / medium-term

Data Gaps Time Frame

Case Study: CEMPRE (Brazil) (www.cempre.org.br) In Brazil, 800,000 waste pickers collect and sort 18% of the recycled waste in the country. In 1992, a group of companies created the Compromissa Empresarial para Reciclagem (CEMPRE) translated to Brazilian Recycling Commitment, which is a non-profit organisation funded by consumer goods corporations, who have partnered to promote recycling and provide safe conditions for waste pickers in Brazil. CEMPRE trains waste pickers, also known as ‘catadores’, through pictures and videos on how to build a business in waste picking and recycling while following health and safety guidelines. The organisation also removes the middle man from the selling transaction in order to allow waste pickers to deal directly with reprocessors and brokers and keep the entire value of the material they collect and sell. Case Study: Heron In-vessel Composting (IVC) The Heron IVC is a containerised South African composting technology that takes unwanted food waste and turns it into a soil conditioner. The technology shreds waste to increase its surface area before being mixed and fed into the composting vessel. The temperature of the material in the composting vessel reaches 60 degrees plus. The process reduces the net weight of the incoming feedstock by around 30%. A 24 cubic meter Heron IVC machine costs around Rand 1.2 million and can process two tonnes of food waste a day. The plant is currently being effectively utilised in South Africa.

This Value Chain (VC) opportunity is for the commercialisation of sewage sludge, either through processing with black soldier fly larva (BSFL) to produce protein and compost, or carbonising and pressing into charcoal briquettes. These two technologies are currently under review to evaluate which provides greater benefit for Malindi Municipality. This review is expected to be completed by the end of 2019.

The key outcomes from this project would include:

› Direct employment at the processing facility; › A suitable method of disposal for the

Town’s sewage sludge that does not impact on the tourist sector; › Providing an income stream for the

Municipality. › Supply of either: › Charcoal briquettes, providing a low-cost alternative to firewood and wood charcoal for cooking and brick making, thereby reducing pressure of woodlands, or; › BSFL as a clean low-cost protein for fish feed and a compost/fertiliser for farmers. Base assessment

For liquid waste there is no sewage network in Malindi, and the Town relies on septic tanks and pits. The emptying of tanks/pits is operated by the private sector, and many are left to overflow. Currently the sludge is dumped out by the municipal landfill site. For sewage sludge there are two technologies being reviewed by Malindi Water and Sewerage Company (MAWASCO) in partnership with Sanivation, with the assessment scheduled for completion by the end of 2019. The two technologies are: › Charcoal briquettes: the sewage sludge is sun-dried and then carbonised in a kiln. The resulting charcoal is then pressed into briquettes for use in domestic cooking or into logs for commercial use. Nakuru has a smallscale plant that is being expanded.

The pilot plant, operated by Nakuru

Water Sanitation and Services Company (NAWASCO), has a capacity of 2 tonnes of briquettes per month which is being expanded to 10 tonnes per month; › Black soldier fly larva: the eggs of black soldier fly are raised on sewage sludge, resulting in mature larva that are high in protein and can be used in animal or fish feed, and a neutralised organic matter that is suitable for use as a soil enhancer/ fertiliser. The BSFL have been approved by the EU as a fish feed. A pilot facility is operating in Nairobi. Black soldier fly (hermetia illuciens) are indigenous to Kenya and many tropical / neotropical zones around the world. They thrive in temperatures between 24oc and 40oc, and have been farmed for many years, being used to compost waste, producing high protein pupae that is suitable for animal and fish feed. Most of the farming has centred on using food processing waste, but recently progress has been made in using BSF to process sewage sludge. Location specific analysis

No precise data on the land requirements are available as both technologies have not progressed beyond the pilot plant stage. A preliminary estimate puts the land required for charcoal briquette processing at around 2,000m2 to 2,500m2. This is based on: › 250 days per year of operations; › Production capacity of around 5,000m3 per year; › 5 days for dewatering the sludge; › 1 day for post-production drying. It is expected that the BSFL processing would require a plot of a similar size. The processing facility with either technology would not need to be permanent and could be moved to a new location if required: › Charcoal processing: the polytunnels and drying racks can be readily moved.

The key equipment (kilns, mixer, briquette making machine, packing machine) could all be installed on skids and moved as required; › BSFL: the polytunnels for dewatering and BSF breeding pens can be readily moved. The vessels for BSFL rearing could be designed to be moveable, together with the drying and packaging equipment. It is expected that there will be some odours from the facility, and as such it should be located away from residential and populous areas. For siting the facility, initially it could be located at the waste dump site, to the south of the Town, where sewage sludge and MSF is currently dumped. Later, the facility could be relocated at one of sites identified for WWTP in the 2017 wastewater master plan.

Value chain opportunity

Key activities The production flow for manufacturing the charcoal briquettes is outlined in Figure 25 below.

Figure 25 - Charcoal production flow

Sludge Supply

› Emptying septic tanks › Trucking to processing site

Mixing

› Combining with binder: waste oil or molasses Drying

› Solar drying of sludge › Geotubes to accelerate process

Forming

› Pressing charcoal into finished balls Carbonisation

› Heating sludge to 300°c with limited oxygen

Drying

› Final air drying Pulverising

› Grinding waste

Bagging

› Packing for sale in 5kg paper sacks

The production flow for the BSFL processing of the sewage sludge is provided in Figure 26 below.

Figure 26 - BSFL process flow

BSF Breeding Colonies

Sewage Sludge BSF Eggs

Sludge Dewatering BSF Rearing Compost

BSF Pre-pupae

Drying Pre-pupae

Feed Mill

Capacity There is no data on sewage sludge production in Malindi and part of the initial assessment by Sanivation will be to assess the potential process volumes. Based on a survey of pit latrine sludge accumulation in Nakuru County, the total volume of sludge in the Municipality could be around 5,000m3 per year (based on an average of 42 litres per person per year). The sludge processing facility would then be scaled to cope with this volume.

With a 57% conversion ratio for charcoal, the current supply of sewage sludge in the Municipality could be used to produce some 2,850 tonnes of charcoal briquettes. This is in line with NAWASCO’s target for Nakuru of 10 tonnes of briquettes per day (2,500 per year). Indicative costs and revenues

For the production of charcoal briquettes, Sanivation have a target production cost for the expansion of the plant in Nakuru of USD $150 per ton, equal to KES 62.5 per kg. This compares well against the average retail price of briquettes of KES 80 to KES 100 per kg. Assuming a sales price of KES 62.5 per kg, total revenues could be around KES 44.5 million per year. There are no cost and revenue estimates for the BSFL process. Potential partners

The key partners for this VC project would be MAWASCO and Sanivation (undertaking the current assessment of the two options for processing the sewage waste), and possibly ICIPE. › MAWASCO is the Malindi Water and

Sewage Company responsible for sanitation in the municipality; › Sanivation is a social enterprise that partners with local governments to help meet the growing waste processing need from septic tanks and pit latrines.

They design, build, and operate treatment plants, focussing on producing biomass fuels/briquettes; › ICIPE (the International Centre for Insect

Physiology and Ecology) is the leading research institute for commercial use of insects and had undertaken much of research into the use of black soldier fly larvae.

INFRASTRUCTURE INTERVENTIONS Street Lighting 3

› Improved provision of street lighting to urban areas and proposed park land area; › Increased safety for residents and improved business activities in lit areas.

Sub Component Estimated Cost Impacts

› Study to determine extent of proposed lighting system picks up all key areas and routes › Lighting design study to ensure suitable coverage of proposed areas › Equipment selection › Development of procurement and deployment / implementation plan › Maintenance plan › Benchmark: £1,250 per pole,13 £30-40k per km depending on spacing

Actual: £60-80k

Funding (eqpt, installation, maintenance): Part IFI, part public funded › Increased safety and security for all residents in newly lit areas › Allows street side businesses to stay open longer › Avoided carbon emissions associated with urban street lighting › More grid power available for other uses › More revenue available for other municipal activities › Partner with Malindi

Municipal Government to coordinate activities › Partnering with equipment specialists to determine appropriate technology solutions › Maintenance - capacity building programme to ensure continued operation of systems › Maintenance - responsibility of Municipal govt

Delivery Mechanisms Challenges

› Long-term operability of stand-alone systems (i.e. maintenance requirements) › Funding › No knowledge of current products on market and installation / maintenance workforce › Short term

Data Gaps Time Frame

Case Study: Jinja is the main city in the district of Jinja, Uganda, with a population of 76,000 and a daily additional working population of 300,000. The Municipal Council has limited revenue generation from taxes and central government transfers, and ran up a significant debt with its electricity provider, so much so, that the provider cut off the street lights. Subsequently crime rates rose, and economic activity was limited to daylight hours. Jinja then became part of national level programmes designed to upgrade informal settlements and urban infrastructure and received over £0.5m to spend on improvement projects. Municipal decision makers indicated a preference for installing solar street lighting over conventional. So far 92 solar street lights have been installed, including 70 along a 2.5km stretch of main road through the Town. The average cost per street light pole USD $1,600 compared to USD $2,350. This is a saving of roughly USD $50,000. Additionally, operating costs are zero compared to traditional streetlights, as they do not consume electricity, and maintenance costs are low, comprising cleaning of the panel, routine checks and servicing of components. The outcome has been that the Municipal Government has drastically reduced its monthly bill, allowing it to reduce its debt and finance other projects, including further streetlighting.14

13 Africa and solar powered street lights, accessed 29th July 2019 https://www.engoplanet.com/single-post/2019/07/22/Africa-and-Solar-powered-Street-lights 14 ibid

FISHING VILLAGE DEVELOPMENT

Figure 27 - Fishing Village Development

The southern anchor point along the coast will be the fishing village in Mayungu beach. Here an existing village living off fishing activities can be regenerated and expanded to become an out-of-town destination for those who want to experience the true life of a fishing community. For tourists and visitors alike, Mayungu fishing village will offer the opportunity to go fishing on traditional boats, live with local families and enjoy traditional coastal recipes with the backdrop of an incredibly varied natural landscape, namely the coral reef coast to the east, a Baobab woodland to the north of Mayungu public beach to the south and a vast and wild nature expanse to the west. Such natural development will contribute to expand and diversify the economy of the local village benefiting residents. New jobs and businesses in hospitality, tourism, eco-adventures and watersports, food and retail will complement and enrich the life of the fishing community and transform the isolated village into a thriving destination half-way between Malindi and Watamu.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms Potential Funding

› Village expansion toward the peninsula including new, small-scale vernacular buildings and public spaces › Low key coastal path promenade including informal seating areas and viewing points › Revamped village green › Upgrade of cold store for local fish catch › Small scale clustered parking (bike, cars, coaches) › KES 2.2 billion › Create a new destination › Diversification of local economy › Bay regeneration › Increased income for local population › Better fishing facilities › Public Authority or a mix Public Private such as › Business

Improvement

District (BID) › DBOM › Mixed funding source: Public realm from Public sector › Private sector › Microcredit from

IFIs › Social enterprise investing

Challenges Data Gaps Time Frame Phasing Project Priority

› Partial land acquisition › Funding › Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies › Land

Ownership › Market study › Medium - Long term › Multi-phase › Urban Development

Proposals supporting

Economic Growth › Public zones by

Municipality (i.e.: cleaning, etc)

Operations & Maintenance

Figure 28 - Fishing Village enhancements

Landscape area buffering properties

Mayungu Beach

Plaza overlooking the bay Village Green Gateway to fishing village

Central piazzas

Overflow temporary carpark

Figure 29 - Phase Enhancements 1-3

The development of the village should be phased to allow it to grow in an organic but structured fashion. This will occur by developing an initial core facility centred around a piazza and providing attractions such as seafood and other F&B outlets, a water sports centre for hiring of equipment, lessons and guiding, an outdoor market for local traders and artisans, a cultural centre relating to the fishing village and a boardwalk with coastal viewpoints. Future developments will include additional F&B, visitor short term accommodation (such as a back packers and guest lodges), events spaces and back of house facilities.

Phase 01 Phase 02 Phase 03 Figure 30 - Phase 1

Figure 31 - Phase 2

Figure 32 - Phase 3

Figure 33 - Fishing village precedents

Case Study: The Ocho Rios Fishing Village The Port Authority of Jamaica (PAJ) is spending $220 million to develop a fishing village in Ocho Rios, St. Ann. Case Study: Akwidda Fishing Village - Ghana Akwidaa is a small town and fishing village in Ahanta West district, a district in the Western Region of south-west Ghana and is one of the southernmost places in Ghana. The economy is primarily based upon fishing, with many fishing boats lining the beach. The Town and fishing village has Ezile bay village and the Green Turtle Lodge with eight thatched solar powered huts facing the beach alongside a bar and dining annex. It is named after the many green turtles that lay their eggs on Akwidaa beach, which has also seen a rare sighting of the species Jaminus Sluginus. Most business is conducted in the village without legal paperwork and many of the surrounding village chiefs own the land and the coconut trees and all purchases must be transacted through them. Business deals are based on trust and spoken words. A new landowner can buy a tree from the village chiefs and has the options of felling it, or keeping the trees standing and harvesting the coconuts on a farm. The recent oil discovery in Ghana also has made Akwidaa a new place for investment due to its oil reserved (Block) near Cape Three Point.

Case Study: Portscatho Fishing Village - UK The fishing village of Portscatho lies in the south west corner of Gerrans Bay on the Roseland peninsula. Portscatho is still a working fishing port. There is safe swimming in the cove itself and many fine sandy beaches close by, including Porthcurnick Sands, a twenty-minute walk north along the cliffs and owned by the National Trust. A short walk in the other direction will bring you to St Anthony Head, with a light house. Portscatho has an annual fish festival.

FISHING VILLAGE DEVELOPMENT Road Upgrade 2

Silversand road will be critical for the proposed waterfront improvement proposal. The road provides the only access to the waterfront. The road is paved; however, the current condition is poor. The drainage along the road is not comprehensive. Due to the waterfront, the road will experience high pedestrian movement. Around 3km of the road has been identified for rehabilitation, as shown in the figure below. The section starts from the Silversand Road-Uhuru Road junction to the Silversand Road-Casuarina Road junction. There would be a possibility of increased through traffic due to the improved condition. Several traffic calming measures need to be taken so that Casuarina road, which is parallel to Silversand Road, remain attractive for through traffic. The traffic-calming measures should include lower speed limit, regular speed humps, and potentially creating a one-way traffic flow and restricting access to heavy goods vehicles. The rehabilitation will need to include resurfacing of the road, appropriate stormwater drainage, sidewalk, and appropriate on-street parking space.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms Potential Funding

› Resurfacing 3km road › Provide pedestrian walkway › Drainage facility › Covered drainage to create footways › On-street parking facility › Speed humps › Bus stops › CAPEX of resurfacing

KES 60m › OPEX of resurfaced road KES 21m › CAPEX of footways (covered drainage)

KES 30m › OPEX of footways

KES 3m › CAPEX of

Stormwater drain KES 45m › OPEX of stormwater drain KES 6m (covered drainage) › CAPEX of two bus stops

KES 2m › OPEX of two bus stops KES 500k › Easy all-weather access to the waterfront › Better and safe pedestrian facilities › Improved land value along the road › Potentially Kenya

Urban Roads

Authority (KURA) as road falls under agency’s jurisdiction › Standard procurement procedure as outlined in Public

Procurement

Regulations 2013 and The Public

Procurement and

Asset Disposal Act, 2015 › PPP Act 2013 › Public funding - potentially from National government or international development partners › Potential for some contributions from the developers of the waterfront or creation of business improvement district at the waterfront area Challenges

› May require some land acquisition › Would increase noise and air pollution due to increased motorised vehicles › Funding › Traffic flow in the surrounding network › Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies › Impact of road traffic due to this rehabilitated road including traffic calming measures › Public consultation › Immediate term › Must have enabling infrastructure

Data Gaps Time Frame Priority

Figure 34 - Proposed bus stops

FISHING VILLAGE DEVELOPMENT New Bus Stops 3

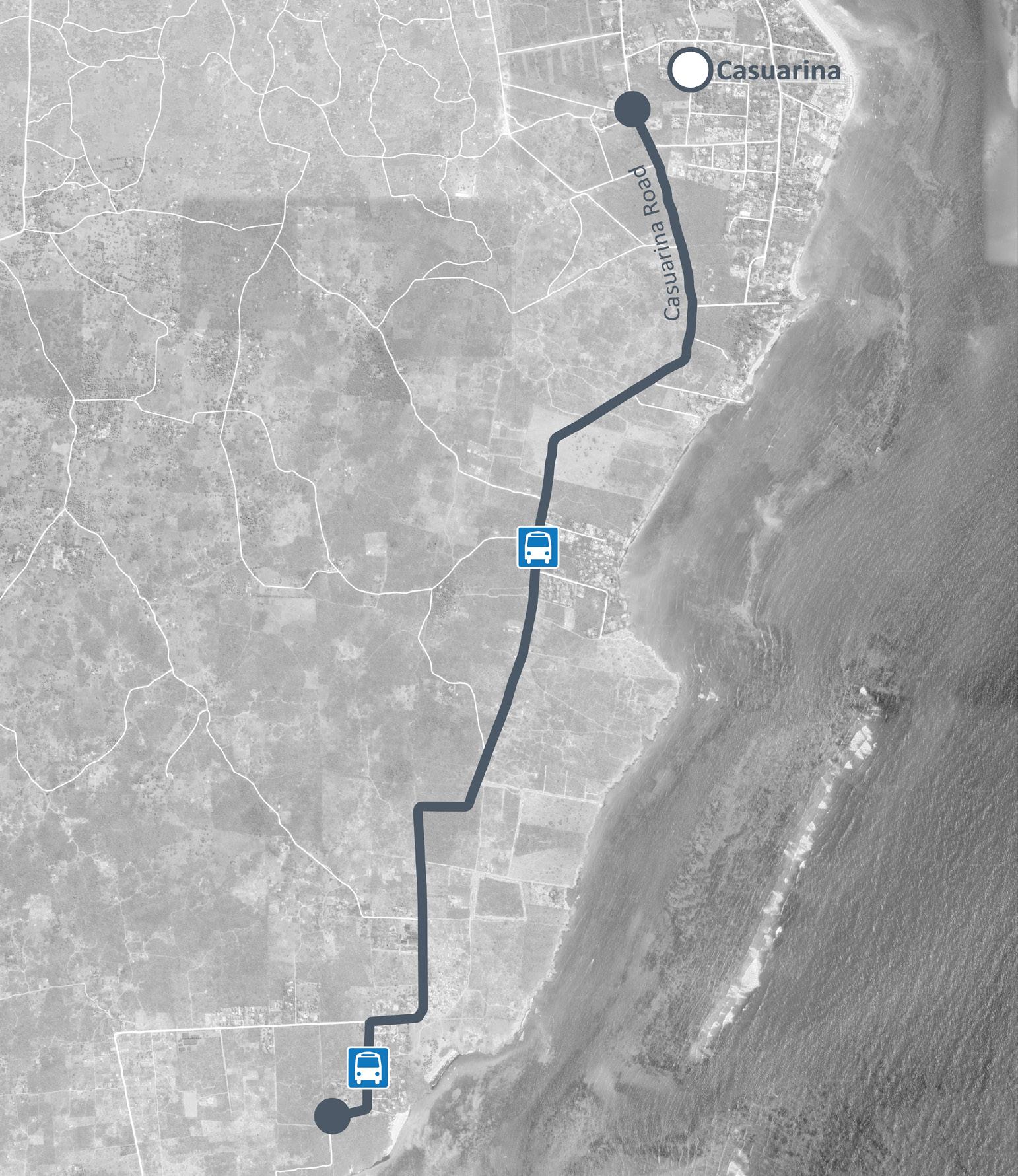

Part of Casuarina Road, leading to the fishing village, is gravel. The road will be an important linkage to the proposed fishermen village improvement proposal. With the increase of tourist and other economic activities at the fishermen village, the traffic is likely to increase on that road. The proposal is to upgrade the gravel section, which is 4.4km in length, to a paved road. The proposed section of the upgrade is presented in the figure below. There are a number of high-end luxury resorts along that road. By upgrading the road, businesses along the road will also be benefited. Improved road surface would attract public transport along that route. Hence, installing four bus stops (two in each direction at two locations) would benefit the mobility.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms Potential Funding

› 4.4km gravel road upgrade to bitumen standard › Four bus shelters › CAPEX of upgrading road

KES 490m › Annual OPEX of road KES 32m › CAPEX of four sheltered bus stops KES 4 million › Annual OPEX of the bus stops and boda-shelter

KES 1 million › Better access to the fishing village by bus › Improved access road to the finish village and other economic activities › Improved land value along the road › Kenya Urban Road Authority (KURA) › Public funding - potentially from National government or international development partners › Some revenue can be generated through leasing or selling of advertising rights at bus stops. That would contribute towards maintenance

Challenges

› Local stakeholder buy-in › Would increase noise and air pollution due to increased motorised vehicles › Funding › Attract bus / matatu services on the new upgraded road › Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies › Bus route rationalisation › Immediate term › Essential enabling infrastructure

Data Gaps Time Frame Priority Figure 35 - Proposed bus stops

FISHING VILLAGE DEVELOPMENT Water Transport (along coastline) 4

The proposal for the waterfront and the fishing village development presents an additional opportunity to develop water transport along the shoreline of Malindi. The route can potentially support both the tourist movements and passengers. The water along the shore is understandably navigable for small to medium size boats. However, a detailed study will be required to create the specification of the boat size and the navigation route. The Kilifi County Investment Guide, 2019, has already identified a major project to introduce water transport along the 264km coastline. The document identified the following locations which the water transport route would serve: Maya, Kilifi, Takaungu, Kikambala, Mtwapa, Mombasa, and the stretch between Malindi and Lamu. The investment guide also proposed to construct a cruise ship terminal at Kilifi to attract international tourists. The Kilifi county development pipeline presents an excellent opportunity for Malindi to leverage these facilities. Hence, the proposal is to create at least two water transport routes that would mainly attract tourists to Malindi. The proposed routes are: Short route

A route that would attract tourists already visiting Malindi and would like to enjoy a sea experience while visiting some of the attractions in Malindi. The proposed route is: The new waterfront Development - Vasco De Gama pillar - Fishing Village - Watamu Beach. Long route A route that would connect Malindi with the Cruise Terminal at Kilifi as proposed by the Kilifi Investment Guide. The route would bring the international tourists to Malindi from the cruise terminal. It would also be attractive to the tourists who already landed in Malindi and interested to visit some different attractions than the Short route. Due to the length (more than 50km), the long route might even provide a better alternative to road transport for some regular passengers. The proposed route is: The new waterfront development Fishing Village - Watamu Marine National Park - Kilifi Cruise Terminal (Future). It is recommended that this water transport proposal is developed along with the Kilifi County Investment plan, therefore, the Malindi water transport proposal is in sync with the regional development.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms Potential Funding

› Develop loading bays along the routes › Develop designated mooring and maintenance facilities for the boats › Developing ticket kiosks with amenities › To be determined following detailed study › Increase international tourism › Increase local tourism › Provide alternative to road transport › Support local economy › Malindi Municipal

Council › Private sector funded public projects procured in accordance with the PPP act 2013 › Public funding - potentially from

National government or international development partners › Good potential for

Private sector funding through concession for operation

Challenges

› Ecological impact › Funding › Buy-in from the local stakeholders › Attract private sector for investment › Time-scale for development to allow to integrate with the regional developments › Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies to identify routes and navigability › Demand and revenue forecasting › Public consultation › Medium term › Must have enabling infrastructure such as loading / unloading facilities

Data Gaps Time Frame Priority

Figure 36 - Short Route: Malindi Water Transport Figure 37 - Long Route: Malindi Water Transport