44 minute read

3.4 Diversification Action Plan

Tourism has been a key economic activity in Malindi, however the recent decline in tourist arrivals and change in Malindi’s competitive and comparative position as a destination within Kenya and globally makes it important to seek ways to promote economic resilience through the diversification of Malindi’s economy. Malindi is endowed with rich natural resources from sea and land which can provide a good basis to expand into different sectors and economic activities, particularly those that promote value addition and provide a more stable path to economic development minimising exposure to global shifts in tourism. The following section outline actions that can help develop Malindi’s economy, particularly in agriculture, fishing and manufacturing. While these actions and interventions are focused on the municipality’s capacity to advance these sectors, it would be imperative to align with County level and wider coastal region plans for sectoral growth to maximise returns and avoid duplication of efforts.

Malindi - Diversification Action Plan

Agriculture Developing agriculture is a priority for the County. The Malindi coast line is an area of high potential but farming in Malindi is still used mainly for subsistence living15 rather than as a higher economic value activity, with a few companies undertaking large scale farming.16 The ISUDP recognises that agriculture is underutilised in Malindi, though climate change has, and will, impact the sector and where it’s focus may be. Currently the main crops grown in Kilifi include maize, cassava, cowpeas, green grams, cashew nuts, coconuts. Cash crops such as cassava and fruits such as water melon, banana, citrus and mango bring in the highest price, however they tend to be crops that require more water and are more sensitive to drought. Malindi has the water resources to develop irrigation, but there is limited infrastructure currently in place.

Figure 38 - Agriculture sector

Strengths

Diverse output. Key - coconut, cashew, cassava, mango. Some agro-processing - cashew, mango juice, moringa, coconut oil, chillies. Some irrigation of land by the river.

Strategic location. Linked to good markets in Malindi and the wider area.

Challenges to address

Pressure on agricultural land. Climate change - floods, drought, crop pests and disease incidence.

Unsustainable practices - pressure on ecosystems. Lack of equipment and vehicles.

Weaknesses

High dependence on rainfed agriculture, only 1 major river. High youth unemployment, preference for tourist / white-collar jobs. Lack of good post-harvesting practices and storage facilities. Malindi hotels and restaurants buy only small quantities from local farmers.

Unreliable electricity, energy needs for pumping water for irrigation. Urban migration - reduces labour and skills availability and knowledge pass-on. Poor condition areas of road network - limits market access.

Poor marketing and market information.

15 Source: Workshop 2, Inception meeting with stakeholders (20/03/2019) 16 Source: County Government of Kilifi, Kilifi Spatial Plan (2018)

Two key sectoral action areas have been identified for Malindi’s agricultural sector - irrigation and an agricultural centre - with short to long term actions identified below. A Centre for Malindi’s Agricultural Activity An agricultural centre, farmers can go to have their goods valued, to source agricultural inputs, connect with suppliers, access financial support and best practice guidance. In the medium-longer term the centre could provide storage for agricultural produce, support agri-processing businesses and integrate technology into Malindi. Access to finance is particularly difficult for farmers wishing to expand to more mechanised activities given the high seasonality, risks related to weather conditions and the lack of secured land and property rights. Aim of the intervention Period Detail

Provide agricultural inputs and equipment Short term

Long term Establish and provide farmers with the agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertilisers best suited to Malindi's environment. The Grow BioIntensive Agricultural Centre of Kenya worked with the Tumaini Women’s Group to help provide them with the right seeds and equip them with the knowledge on how to use and maintain them, helping them to move closer to food sovereignty.

Once strong agricultural practices are in place in Malindi, consideration can be given to integrating technology such as tractors to farmers to maximise agricultural outputs.

Aim of the intervention Period Detail

Better connect buyers and sellers Short term

Medium term Provide expertise within the centre to fairly assess the quality and value of the produce, providing product certifications can help differentiate crops in the market-place, and justify selling them at a premium. This will also incentivise improved production and can ensure inputs to agri-processing are of a high-quality.

Connect farmers and facilitate better corporation across the network of farmers, small businesses and markets. This could be based on a vouching system or advertising farmers and buyers in the centre.

Encourage and educate farmers to aim for fair trade status on their produce, this will improve the welfare of farmers and the sustainability of the sector alongside the increased produce values. There are examples of promoter farmers working with and training farmers to promote high standards, communication and ties. Such cooperatives have successfully used fair trade certification and farm supply shops. Organisation is crucial to this delivery.

In order for processors to efficiently produce products they need reliable inputs, local farmers, tend to struggle to consistently supply agricultural inputs in the right time frame, to the right quality and the right amounts, connecting with farming cooperative could ensure a diversified stream of inputs to avoid some of these risks. This can be achieved through: › The cooperative been able to ensure the supply and its quality for processors, through buying connecting a collective of farmers and goods; › Encouraging and facilitating primary processing, value addition, post-harvest management and empowerment of women and young farmers will help to reduce post-harvest losses; › Encourage supply of goods with different seasonality, that require similar processing equipment to enable a link all year round (mangoes are only processed for 6 months October - March).

Provide marketing and business advise and training on topics such as accessing markets, providing inputs to processing and enabling value addition. This can enable farmers to sell their own produce.

Aim of the intervention Period Detail

Provide information, training and best practice guidance Short term

Medium term

Help farmers access finance and financial advice Short term

Short term

Long term Establish ties with local education institutions and experts to provide sessions for farmers in the area, the farms could even act as a test bed for agricultural students and professionals. Examples have seen yields on participating farms improve greatly where academia and students collaborate with farmers.

Support businesses who engage with the agri-processing sector, considering the processing steps, packaging, market access, export and marketing. The Manufacturing Priority Agenda highlights the importance of facilitating stronger supply chain linkages and sectoral ties with manufacturing for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) and infant industries. The Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) also provide training and courses to help small businesses develop their business strategy.

For the cooperative to be self -sustaining, training could incorporate aspects of production management, crop harvesting technology, handling and repair. Partners could include NAFIS (the National Farmers Information Service), whilst Farmer Field Schools have been set up to educate farmers on sustainable and profitable farming across Kenya. Training can also develop understanding of the importance of resilient, sustainable and inclusive farming practices to short term and long-term benefits.

Offer farmers advice on how they can access and manage finance, this could involve offering impartial drop in sessions or training sessions to farmers.

Establish simple ways for farmers to access finance in emergencies, this could take the form of Malindi’s fishing cooperative where each member pays a share of their monthly wage into a pot and when one member needs help, they can access this saving.

Establish secure storage facilities so farmers can use surplus as collateral. The Food and Agriculture Organisations provided support to cooperatives in Niger by ensuring there were sufficient secure warehouses where local farmers can store any end-of-season surplus. The cooperatives and bank/microfinance institution retain a key each for the storage facility, where a loan can be negotiated by the cooperative to be given to the farmers when they store their surplus here.

Key organisations and stakeholders for action

› The Municipal Board and County Government; › Producers - Small, medium and large agricultural businesses; › Local market sellers; › Innovation networks could be established with higher education institutions close to Malindi, such as: Pwani

University (Kilifi Main Campus), North Coast Medical

Training Centre, Peretech college, Kipepeo Technical

College and Kilifi Technical College - they could offer courses or use willing farms in Malindi as test beds.

For example, the Manor House Agricultural Centre in

Kitale provides training, student attachment programmes and mini training centres; › Key tourism players / hoteliers; › Banks and local finance players, engage with best practice initiatives such as the World Bank’s AgriFin programme; › Best practice organisations to support or inform early development of the centre, such as the Alliance for a Green

Revolution in Africa (looking to strengthen key links in the agricultural supply chain); and Kenya Agriculture and

Livestock Research Organisation (KALRO). Approach principles

› Organisation. Corruption and mis-aligned incentives have prevented previous cooperatives from being successful. The Hub Model was re-established by Heifer International in Kenya to form a cooperative which wasn’t mismanaged. The Board may seek to identify key expertise and resource to support the initial set-up, with early partners and stakeholder engagement; › Membership fees could ultimately be used to support the centre’s operation, whilst members would buy-in to the centre’s plan and provisions; › Value addition. To support Malindi’s development of its agri-processing sector, the centre can link up with new operations in supporting knowledge sharing across the supply chain to enhance effective input delivery and through to export. Best practice examples can be shared for produce storage, processing steps, packaging, market access and external marketing; › Labour market and education. Few young people in Malindi are interested in having a career in agriculture, where sector perceptions and opportunity access can be addressed. The current education system does not enable or encourage agriculture as a career. A greater integration and communication of agriculture production, processing, management and marketing can be useful, alongside stronger ties between education institutions and the sector to provide insights / experience to young people and ensure the curriculum meets the needs of the sector; › Female participation. Women tend to be excluded from business decisions and in accessing information to help increase yields, despite having an active role on the farm. Encourage female participation through the centre, offering training and financial advice to empower local women; › Land tenure. Farmers experience insecurity, which makes them reluctant to invest in their land.

The problem around land rights will need to be addressed.

Aim of the intervention Period Detail

Ensure Malindi has a resilient water supply capable of supporting its agriculture sector Short - long term Ensure Malindi has the right irrigation infrastructure in place to ensure it can best utilise the abundant fresh water resources of the river Sabaki, take advantage of the natural environment for diverse crops and meet the demands of Malindi’s future ago-processing centres. The National Government is investigating the use of the Galana River to the north of Malindi for irrigation under the Galana-Kulalu mega food security project. The land that is more suitably positioned for irrigation would be best focused on production that will thrive with this enhancement. Appropriate training and guidance should be provided to farmers on utilising irrigation and raising production yields. Water harvesting, supplemental irrigation, deficit irrigation, precision irrigation techniques, and soil-water conservation practices have the potential to improve water productivity. In the short term to improve the ability to irrigate crops, solar irrigation and boreholes could provide a more suitable solution. This is presented in the following page.

Key organisations and stakeholders for action Approach principles - to overcome barriers

› The Municipal Board and County Government; › Malindi Water and Sewerage Company; › Kenya Water Services Regulatory Board; › Kilifi Mariakani Water and Sewerage Co. LTD. › Land tenure. Farmers and partners will be reluctant to invest in land if it is not certain that land will remain theirs going forward. The County and the

Municipality should recognise that land rights will be an important enabler for water infrastructure, and address this for land that is identified as strategic / suitable for irrigation; › Combine with training. Alongside efforts to develop irrigation, appropriate training and guidance should be provided. For example, NAFIS is a government service that provides ad-hoc support to farmers; › Water pumping for irrigation also requires reliable energy supply for periods of low rainfall, these pumps could utilise solar energy. This will support the provision of high-quality produce into the future, as inputs to

Malindi’s developing agri-processing industry.

AGRICULTURE Solar Irrigation and Boreholes

› Improved provision and ability to irrigate crops and provide drinking water to livestock in rural areas currently not served by the electricity grid or by the domestic water supply system; › Reduced carbon emissions through replacement of diesel generators.

Sub-Component Estimated Cost Impacts Delivery Mechanisms

› Mapping of ownership of all agricultural and livestock holdings and current status of their irrigation facilities › Review of abstraction volumes from each borehole › Establishment of needs for solar irrigation and borehole systems › Preparation of design brief for boreholes / irrigation systems › Development of procurement and deployment plan › Maintenance plan › Benchmark:

USD $3,000 per system17

Actual: USD $90,000 based on max 30 systems

Funding (eqpt, installation): IFI / donor finance › Lower costs for farmers where current system is on grid › Consistent service provision for farmers with no powered irrigation › Reduced carbon emissions associated with farming sector › Partner with regional / county government to coordinate activities › Partnering with local equipment specialists to determine solutions › Maintenance - capacity building programme to ensure continued operation of systems › Maintenance - responsibility of individual farmer Challenges

› Effort needed to obtain comprehensive data on current situation › Funding Data Gaps Time Frame

› No knowledge of current situation › Short to mid-term

Case Study: Grid Alternatives International Program has been helping farmers in Nicaragua with sustainable irrigation solutions for the last five years. One such solution helped the Valle family of Matagalpa. They grew squash, passion fruit and tomatoes on two acres of land to sell at the local market but had trouble making a profit due to high irrigation costs. The monthly electricity bill to run their pump was USD $33, but their income was only USD $103. Also, the supply quality was poor, meaning they could only irrigate on three days instead of every day. Other expenditure reduced their earnings to USD $25 a month. Working with Grid Alternatives and local company Suni Solar, they installed a solar irrigation system. The total cost was USD $10,000, but Valle family was only asked to pay USD $2,000 which they financed via UNAG, their national agricultural organisation. Two solar panels power a pump that abstracts water from a nearby river into a cement tank and to a gravity fed pole mount system that drips onto the plants. With adequate water supply to the plants, they can now irrigate other crops including onions, pipian and pasturage, and also raise tilapia. Their monthly electricity bill is now USD $3, and their monthly earnings have now increased to USD $546.18

17 FAO The benefits and risks of solar-powered irrigation - a global overview (2018), accessed 30th July 2019 http://www.fao.org/3/I9047EN/i9047en.pdf 18 Solar Drip Irrigation Case Study - The Valle Family, accessed 29th July 2019 https://gridalternatives.org/sites/default/files/International%20Valle%20irrigation%20case%20study.pdf

Fishing The estimated annual economic value of goods and services in the marine and coastal ecosystem of the Western Indian Ocean is greater than KES 2.2 trillion, and over KES 440 billion (20%) for Kenya.19 However, the fishing industry only accounts for about 0.5% of Kenya’s GDP, despite Kenya owning a maritime territory of 230,000km2 and having the Victoria Basin and a long coastline. Lying on the coast of the Indian Ocean, Malindi has access to an abundance of fish. The Malindi-Ungwana bay is important to the marine fishery production in Kenya due to the shallow bathymetric formation and the freshwater, nutrients input by Rivers Tana and Galana.20 Around 150 vessels land in Malindi of the up to 300 operating in the County. There is a fish market in Malindi and a few fish shops across the Town. Malindi supplies a range of fish (mainly tuna) outside of the County, with the majority going to Nairobi and Mombasa. There are also exports mainly tuna (frozen), and some live crabs (through Chinese traders), that go out through Mombasa to Hong Kong or Singapore. The Kilifi County Government has planned to spend KES 5 billion on supporting the counties fishery activities. The CIDP highlights flagship projects aimed at developing fish ports and boat building yards and establishing fishery control and surveillance units. The facilitation of larger boats (with landing capability) would allow for the better managed exploitation of deep-sea fisheries, whilst the availability of more and better equipment would support the employment potential in the sector.

Figure 39 - Fishing sector

Strengths

Substantial sea fisheries and good diversity of fish to local and national market.

Established boat building and repairs facility. Some sport fishing experiences, and pond fish farming. Strategic position for ports and A7. Currently a jetty.

Challenges to address

Climate change effects - marine biodiversity. Risk of price rises beyond local affordability. Destruction of mangroves.

Weaknesses

No current fish market, poor marketing information and skills. Limited storage and transport. Lack of resources and skills training. Limited facilities for preserving. Limited processing and packaging value additions.

Inadequate fishing knowledge and equipment. Heavy reliance on imported fuel for the sector. Unlicensed and unregulated fishing risk. Risk of rising illegal activities. Barriers to some groups’ participation e.g. women and PWDs.

19 Source: Business Daily Article, Kenya yet to mine KES 440 bn eco coastal system (2018) https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/datahub/Kenya-yet-to-mine-its-Sh440-billion-coastal-ecosystem-/3815418-4597172-w0rikcz/index.html 20 Source: Kenya marine and fisheries research institute, Annual report (2009)

Three action areas have been identified for Malindi’s fishing sector, where key partners and stakeholders and approach have been set out in the following tables. A series of actions under each area have been recommended, covering the short, medium and long term. These are presented as follows:

Intervention Aim of the intervention Period Detail

Help to better equip Malindi’s fishing sector Ensure there are appropriately placed and sufficient cold, dry, and live storage facilities for catch Short term

Med Term

Consider the potential for fishing boats capable of deep-sea fishing Med Term

Med Long Term This is a cross sector intervention and leaders across the agriculture, energy, education and food sectors must work together to ensure the successful integration of cold chain technology. There are many options and technologies for cold storage food handling, processing, storage and transport. Some are simple and affordable, and others more complex to manage. There needs to be careful consideration around what cold storage will best suit Malindi’s climate, value chain projects, energy and transport infrastructure.

Develop appropriate and sufficient cold storage to support food processing. This should be provided at the most effective points along the sector supply chain. Enable the required supporting aspects - logistics, maintenance, infrastructure, education and management for cold storage. Stronger ties should be facilitated between local markets, the visitor economy and the processing industries with cold transport for wholesale markets, food markets and food service operations.

To achieve the greatest value addition of Malindi’s catch, there needs to be cold distribution infrastructure e.g. cold transport, considering the extent of travel for Malindi’s fish e.g. along the coastline, to Mombasa, to Nairobi and other regions, and as international exports.

Larger fishing boats have the potential to hugely increase fishing output, with equipment that allows longer fishing ventures and the catch of better-quality fish. These boats could integrate technology to improve efficiency.

Key organisations and stakeholders for action Approach principles

› The Municipal Board, County Government and national regulators › Work with hoteliers and local market sellers

Malindi i.e Malindi fish shop and Abdul fish shop › Banks and local finance such as Kenya

Women Microfinance bank, M-Pesa Eco Bank

Kenya, Imperial Bank-Malindi › Malindi is a diverse town with an imbalance in community inclusion, as such support and equipment needs to be fairly distributed to avoid conflicts; › To successfully integrate cold storage and other technology there needs to be significant supporting services and know-how such as logistics, maintenance capabilities, education and management skills; › There needs to be consideration around what storage would be most efficient for Malindi considering the weather and impact on storage costs and operation; › Difficulties in accessing finance Sharia finance may limit the potential for fisherfolk to take advantage of cold storage - financial access support is an important enabler; › Fisherfolk and farmers need to be confident that they will get a return on their investment in cold storage, there needs to be an assessment to understand where to best facilitate the investments and supporting services.

Intervention Aim of the intervention Period Detail

Develop an educated fishing skills base Foster and establish new ties with NGOs and Education facilities with knowledge and interest in the sector

Facilitate ongoing training and knowledge share. Embed resilience, sustainability and inclusion principles Short term

Short Long term Basic fishing skills such as safety, boat navigation, repairs, engineering, marketing and basic processing are some of the required skills to enable sustainable growth in the sector. Continue to work with work with educational institutions and NGOs with specialisms in the sector, such as the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI) team and facilitate greater interaction between them and local fisheries to disseminate information and provide education and training on best practice.

› To facilitate greater inclusion of women and other communities in the fishing sector, the cooperative should support women into the sector and its supply chain. There are some successful case studies here with women trained in selling fish and negotiating with local hotels and restaurants; › Adult training could in the long run be integrated into a successful cooperatives agenda, to cover the fishing sector and sustainability, coast protection and the wider business opportunities.

Key organisations and stakeholders for action Approach principles

› Key educational players in the fishing sector

Kenyatta University of Agriculture and

Technology, Technical University of Mombasa,

National Maricultural Research & Training

Centre in Shimoni, Kwale County › NGOs and businesses already engaged in the sector, such as M-PAYG, The International

Institute of Refrigeration, The World Food

Logistics Organisation and the Global Cold

Chain Alliance › Perceptions of fishing as a dangerous and ‘last chance’ career choice need to be changed as there is great potential in the sector; › Sea fishing is not currently a diverse community sector, it is dominated by Malindi’s Muslim community and going out to sea is exclusively a male activity. There needs to be awareness and education that fishing and related business activities are available for everyone, with training that empowers those currently excluded.

Intervention Aim of the intervention Period Detail

Make regulation of Malindi’s fishing sector a priority Monitor and Regulate fishing activity Short term

Increase the awareness of locals of the importance of caring for their coast Short Long term

Increase the awareness of locals of the importance of caring for their coast Long term › Understanding, mapping and monitoring fishing grounds is critical for resource management. Local experts who can sample catch from these grounds will also be important to help understand stocks and trends; › Commercial trawlers are overfishing in Malindi. There needs to be greater regulation to reduce the fish stock depletion and to protect local fisherfolk from these impacts. The Kenya Coast Guard Service, only established in 2018, are already having a positive impact on fish stock numbers, however further local support will be needed to monitor and regulate other practices such as beach seines and bottom trawling which are destructive. There needs to be greater enforcement in the area, this could be in the form of local sea policing along Malindi; › This will also be important in the longer term to reduce the risk of illegal activity on this part of the coast.

A cooperative, made of fishermen, fishmongers, boat owners, sellers and other stakeholders, would be a useful way to develop a collective voice for the sector in Malindi. Some best practices from elsewhere include the allocation of areas into no fishing zones (this needs consideration around enforcement), individually stamp registered artisanal boats for identification (a first step in licensing and improving safety and response), development of fisheries management plans and the installation of a Vessel Monitoring System.

Consider how technology can be dispersed into the fishing sector to monitor vessels, for enforcing regulation and protecting smaller vessels with communication and safety additions, e.g. smart phones, can support regulation through photos and safety by providing contact. The World Bank’s West African Regional Fisheries Program is currently working to integrate this technology in West Africa, whilst the KMFRI have already begun to establish the use of technology such as an Acoustic wave and current profiler.

Key organisations and stakeholders for action

› Key organisations with expertise can help develop appropriate and effective regulation such as: International Maritime Organisation and Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute › Cooperate with existing fishing regulators such as the Kenya Coast Guard Service (KCGS) › Local artisanal fisheries, key industries players › Key tourism players / hoteliers / recreational anglers › Key educational players in the fishing sector › Local market sellers and businesses e.g. Malindi fish shop and Abdul fish shop › Scientists, marine biologists who can help to monitor activity along the coast Approach principles

› Sufficient safety precautions to be in place for fisherfolk, with safety equipment and rescue vessels. This will help support its desirability as a career; › It is imperative that the fishing cooperative works in everyone’s best interest and is managed fairly and effectively; › Many fisherfolk are suspicious of and reluctant to be involved with surveillance and monitoring, there needs to be trust established between fisherman and those managing / implementing monitoring equipment. An understanding of how the equipment works and can benefit the sector will be useful.

Manufacturing At present, there is no high concentration of manufacturing activity in Malindi Municipality, however there is potential for growth in this sector. Kilifi manufacturing output was KES 8,456 million in 2017, accounting for 7% of Kilifi’s economy. Ongoing agricultural products processing in Malindi such as mango, moringa, coconut, pineapple, passion fruit, mango pulp production, moringa oil and coconut oil can provide the basis for value additions while the development of Kenya Industrial Estate near the airport has some business already renting premises for industrial activities including the production of moringa oil. Malindi has strategic connections to Nairobi and Mombasa, with a reasonably strong market and retail base to sell locally. The Municipality has the particular potential to a) grow medium sized industries with a focus on processing agricultural and fishing produce, b) support circular economy production, such as expanding plastic and waste recycling, and c) develop and formalise its smaller scale production, including crafts and the Jua Kali sector, for the local and visitor market.

Figure 40 - Industry and Trade sector

Strengths

Vibrant town centre and markets, with various products. Activities include mango juice, moringa and cashew processing, salt production and cotton production. Deposits of natural minerals e.g. salt, silica corral, sand, ballast. Good road connectivity (A7) to the town to major towns and ports.

Challenges to address

Overarching challenges - lacking employment and skills, inadequate markets, limited value addition and risk of environmental degradation. Large scale expansion risks soil, air and water contamination.

Weaknesses

Lack of training and skills development, especially in marketing and management. Unreliable power, where infrastructure is spread out. Little industry within Malindi, with limited marketing, logistics and supply chain links.

Sector dominated by micro and SMEs.

Pressure on land and potential conflict between industrial and tourism uses.

Lack of supporting infrastructure - waste management, water supply, sewerage. Unreliable power and high costs. Lack of parking facilities for heavy commercial vehicles. Road quality issues impact market access.

Intervention Aim of the intervention Period Detail

Ensure Malindi’s local businesses benefits from the growing sector, through business support Facilitate marketing and business advice sessions for local manufacturers Improve business registry Short term - medium term

Educate and support local businesses to get into manufacturing and processing Short term

Finance, access that is inclusive

Provide a shared space where local businesses can start to process goods Medium term

Support sector inclusivity, sustainability and resource efficiency Short term long term Facilitate local sessions for manufacturers that provide guidance on how they can better market and package their goods for value addition. This could range from early stage organising to later stage branding of goods. Malindi’s sandals are well known for example and there is an opportunity to expand and formalise shoes / sandal making. Taking advantage of the good reputation of Malindi’s sandals and emphasising the ‘Made in Malindi’ brand has the ability to increase the value of the good, in particular in international markets. Improve business registry: the national government is in charge of maintaining track of businesses, and has facilitated business registration through an online process. Micro businesses and the informal sector can be encouraged to register as part of these information sessions.

Local businesses need to understand the next steps they will need to undertake in order to access wider markets, these will be different across sectors and complex concepts to those new to the idea of expansion. Extension officers and training sessions facilitated by experts and university figures should be offered and facilitated by the local authority; these should educate and empower local businesses on how to access wider markets, covering topics such as regulations and extra costs associated with international export, environmental impacts and mitigation, equipment requirements, handling standards, quality assurance, Fairtrade amongst other subjects. From these connections to higher education institutions such as colleges and universities work placements could be organised, and full-time roles could be provided to students after their studies.

Help to facilitate and promote a Savings and Credit Co-operative (SACCO) that it is inclusive of women, PWD, PID, regardless of their wealth, status, size of business, etc.

Within the industrial park, areas with shared processing equipment could be developed to enable local businesses who cannot afford to invest in equipment could pay a rental / membership to use this on a periodic basis. This could help local businesses make the first step to processing. This will require careful planning, education, security and monitoring to ensure that the facilities are used fairly and safely. Kenya’s first makerspace in Nairobi, Gearbox, has successfully provided a space for innovation and place to test ideas of Nairobi’s creative population. This type of space could also have training and links to local universities, offering sessions to local students and young people interested in the sector.

For the manufacturing sector to truly benefit locals, to protect Malindi’s environment and work with rather than against Malindi’s other key sectors, the sector should embed inclusion, sustainability and resource efficiency: › The current manufacturing sector in Malindi has high female participation, with sandal making and fish processing currently conducted almost entirely by women. The Board should establish a system where targets for female, PWD, young persons and other SIGs participation rates are set. Businesses that meet these targets can be rewarded through advertising or awarding; › For sustainability, the sector should be regulated in terms of pollution and waste, with the education of businesses on the importance of sustainability and how to embed this in their practices. An example approach is the instillation of solar panels on new buildings within the manufacturing areas; › The processing of seafood and agricultural inputs, in particular those of seasonal nature, can help to reduce waste especially by linking the sector up with business opportunities in municipal waste processing. Businesses should be encouraged to utilise local supply chains and produce that works with and not against Malindi’s environment, through education on value addition and Fairtrade.

Intervention Aim of the intervention Period Detail

Workforce and skills development Source labour locally Short term

Develop expertise and long-term knowledge share

Establish ties with local education centres Short term Operators will need to make commitments to ensure that a certain amount of their labour is sourced from within the County, some examples of interventions to help encourage this could be of funding work relevant courses, facilitating career events or visitations from key business figures and lecturers within schools in Malindi. Businesses can be monitored (larger businesses) and rewarded (more for smaller businesses) on their employment and training of local, for example a Malindi certification or advertising / support for businesses that perform well here.

Onsite training is effective to ensure there is delivery of relevant and targeted training, that is convenient for workers. The larger-scale manufacturing sector developments can train up locals from the early stages across key tasks, this will suitably include women, PWDs, youth and other SIGs and consider the requirement for a breadth of skills across the sector processes (e.g. operation, machine repair, management etc.) Institutions such as the KAM propose training for factory workers and middle management alike. Ensuring structures are in place to facilitate this ongoing internal training, will not only ensure a reliable stream of employment, it will provide locals with secure employment and transferable skills.

The manufacturing sector will require a range of skills including marketing, machine maintenance and logistics. Facilitating connections to higher education institutions with focused collaboration with specific subject departments to support students to move into the sector, from which placements can be organised, could lead to full time roles for students after their studies, students will also pass their knowledge on to other workers. Engagement with local schools, colleges and universities can increase awareness of opportunities in the sector.

The following projects were identified, assessed and prioritised as having the most potential within Malindi focusing key economic sectors and on value addition.

Project: Fish processing, packaging and distribution centre

Malindi is one of the key landing sites for catch for onshore fisheries, with around 150 vessels operating out of Malindi and some 300 across the County. The overall catch can be substantial (over 2,000 tonnes per year has been landed in Malindi and over 6,000 tonnes across the County) and much of it is high value (e.g. yellowfin tuna). However, the processing, storage and marketing infrastructure is limited. When selling their catch, fishermen are in a weak position, as in many instances they have no alternative but to sell to traders who take the product (and much of the value added) to Mombasa for export. When the catch is high, there is often no market (even at low prices) and post-catch wastage is high. This project then covers the establishment of a processing facility that would provide an alternative outlet for local catch and increase local value added.

Project: Fish hatchery with supplies and training The coast around Malindi and Kilifi County is well suited to mariculture, with a good range of species including shrimp, crab, lobster and several species of fish. Inland there is good potential for pond fish farming, both along the river and elsewhere in the County. While freshwater pond fish farming has focused on tilapia and catfish, there is also potential for freshwater shrimp. Several factors have held back the development of the fish farming and mariculture sector in Malindi, in particular: › The lack of a ready market: this will be addressed with a fish processing facility; › General lack of skills and knowhow; › Availability of young, e.g. fry, fingerlings and zoea (baby crabs). This project sets out to address these last two issues by establishing a hatchery for fresh and saltwater fish and crustacea. By providing a stable supply of fingerlings, etc., for the farms, this project will support the expansion in the fisheries sector in Malindi.

Project: Feed mill There is potential for establishing a feed mill in Malindi that would take waste bi-products from fish and agri-products processing. In addition to the high-protein waste available from fish processing, some of the major crops grown around Malindi have substantial process waste that is of value in animal feed, including mango, cassava and coconut.

At present, much of the waste bi-products are either composted, dumped or fed directly to cattle, chicken and goats. While this latter use is beneficial, there is greater value to be obtained in providing animals with a proper feed mix that matches their dietary requirements. This project covers the establishment of a feed mill that would focus on taking processing waste from Malindi and the wider county and producing feed primarily for fish, crustacea and chicken farming (key value added sectors), but also for shoats and cattle.

Project: Cassava processing centre Cassava is one of the major crops grown around Malindi and across Kilifi County. There is substantial potential to raise production of this relatively droughttolerant crop, and there are county-level plans to raise the overall acreage and yield. Cassava has a lower water footprint than maize (approximately half), and it is the carbohydrate of choice among farmers in the County. Fresh cassava spoils rapidly (within a week) and processing capacity is required to support the expansion in production. Cassava can be used to produce a wide range of products including flour, crisps, glue, animal feed, bioethanol and alcohol. Cassava is a good source of starch, and equally importantly has low or zero gluten. This opens up the potential for exports to Europe and North America where gluten intolerance is increasing and there is strong demand for cassava flour. This project is for the development of a cassava flour production facility, with potential to expand into other products later.

Project: Food processing centre for canning / jarring fruit Malindi sub-County produces a wide range of fruit and vegetables, many of them suitable for canning and bottling. The key products include mango, pineapple, a range of citrus and passion fruit. There is potential for raising production volumes for many of these valuable fruits, if the offtake / processing capacity is available. For example, for mango the CIDP for 2018-22 includes the “integrated mango value chain enhancement project” under which there are plans to raise the acreage under mango and yields, which together could result in a 50% rise in production. This project is for a food processing centre in Malindi that would have 3 or 4 colocated facilities, benefiting from some shared machinery, storage, marketing, distribution, manpower and supplies (foodstuffs and packaging materials). The first phase would be for a mango processing facility, producing cans and containers of pulp, sliced fruit and juice. A mango processing facility has been built in Malindi but was never commissioned and has been mothballed since 2016 and is now in administration. There is potential for this

facility being rehabilitated and commissioned. The position of this facility (financial, ownership and technical) needs to be assessed to identify how/if it could be incorporated into a general processing centre targeting a range of fruit products.

Project: Recycling of municipal waste As with many towns in Kenya, waste management is problematic. For municipal solid waste (MSW), council funds are stretched to cover regular collection operations, and as a result some of the MSW is dumped and/or burned. A number of waste pickers operate at the municipal landfill site and undertake organised separation of key waste streams (metals, glass - by colour, plastics, etc.). Remaining waste is burnt for hygiene reasons and to avoid an infestation of pests. These pickers work under harsh conditions and sell on to dealers at low prices due to their inability to consolidate volumes and their lack of alternative outlets. There is potential to upgrade the existing separation and recycling to raise local value added and reduce the need for landfill.

For liquid waste there is no sewage network in Malindi, and the Town relies on septic tanks and pits. The emptying of tanks/pits is operated by the private sector, and many are left to overflow. The sludge is dumped out by the municipal landfill site. There are several technologies for processing sewage sludge into commercial products (biogas, fertiliser, charcoal briquettes, etc.), that would raise local value added and reduce the need for landfill. This project is for co-located MSF and sewage sludge processing, creating commercial products. While the Malindi UEP is focusing on fish farming and municipal waste as opportunities that maximise benefit (section 3.5) the aim would be to combine elements and additional processes presented above as these are developed promoting principles of a circular economy - a diagrammatic representation given below.

Figure 41 - Circular economy principle

MSW Recycling

Composted Organics

Mango Processing

Cassava Processing

Other Agri Products

Fish Processing

Feed Mill

Fish Farming

Poultry Farming

INDUSTRIAL CLUSTER (AIRPORT)

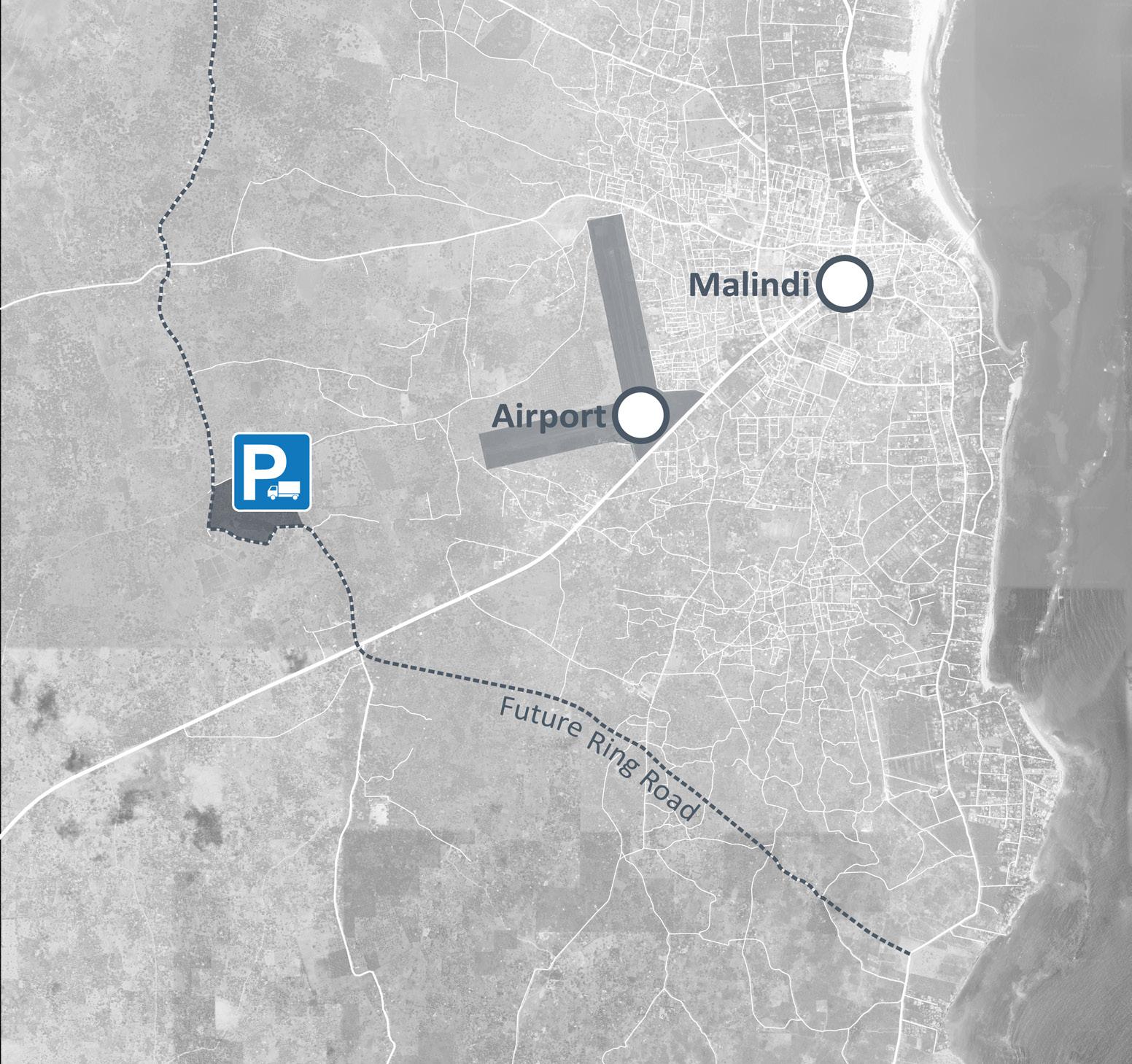

Malindi’s aspirations to revitalise its tourism sector must be complemented by a suitable strategy that helps the Municipality become more resilient to cyclical market trends that, risk to shatter the local economy. As such, the diversification action plan has been put in place which includes industrial activities located across the County. Whilst some of these require proximity to existing or planned facilities (i.e.: waste dumping ground or water treatment plant), other industries can be co-located in clusters and benefit from single infrastructure investments. The study has identified the potential for an Airport industrial cluster, where land is relatively abundant, access is good and the potential proximity to the airport and a future cargo service might attract further investors to locate and invest in Malindi. The plan illustrates the location in principle for the industrial cluster. To enable development, a road upgrade and the installation of suitable infrastructure (water treatment and power plants) are included in the initial investment package. This is further supported by the announcement that in 2020 the airport main runway will be extended to allow international flights to fly directly into Malindi, thereby enabling greater tourism and cargo opportunities.

Figure 42 - Industrial Cluster (Airport) and Detail Study (Inset)

Figure 43 - Industrial Cluster (Airport)

INDUSTRIAL CLUSTER (AIRPORT)

The plotting arrangement for the industrial cluster has been configured based on a phased development approach with access from the nearest point to the upgraded access road. This will minimise initial development costs and allow the servicing of up to ten plots of varying sizes to accommodate the proposed fish and food processing plants along with other private investments that may be triggered by the introduction of industrial infrastructure in the area.

The cluster will be supported by a new low voltage distribution network aligned with the proposed new upgraded road and a waste-water treatment plant (WWTP) for the cleaning and re-use of waste-water for the industrial processes and irrigation purposes. Future development phases can be introduced and extended moving southwards towards the WWTP.

High level costs for phase 1 and possible future phasing are shown in the adjacent table.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms Potential Funding

› Industrial park plot subdivision › Enabling

Infrastructure, namely access, power, waste, water treatment, etc (see following section for details) › UK to provide table for costing › Single investment in infrastructure › Coordinated industries benefiting from good access to roads and possible airport cargo › Off-the shelf investment opportunity › Self-contained eco-cluster development › Climate resilient infrastructure › Circular economy › Significant job opportunities › Design, Build,

Operate, Maintain › Public infrastructure, private or PPP investments › External

Infrastructure -

Public authority,

IFIs › Industrial Cluster internal facilities and industries -

Private

Challenges Data Gaps Time Frame Phasing Project Priority

› May require some land acquisition: › Upgrade access road; › Developable land › Would increase noise and air pollution due to increased motorised vehicles › Funding › Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies › Land

Ownership › Market study › Medium - Long term › Multi-phase › Urban Development

Proposals supporting

Economic Growth › Public zones by

Municipality (i.e.: cleaning, etc)

Operations & Maintenance

INDUSTRIAL CLUSTER (AIRPORT) Truck Park Facility (Potential Locations) 4

There is a high-volume heavy goods vehicle passes through Malindi. Due to the proximity of Kenya’s main seaport, Mombasa, and future port in Lamu, the truck volume is expected to increase. Due to the lack of appropriate parking facilities, a large number of trucks are parked along the local roads. Such an arrangement not only reduces the capacity of the road, but it also creates safety hazards for regular traffic. Malindi ISUDP already identified a location near the airport for a mega truck terminal (as shown in the Figure 44). The location, identified by ISUDP, 1km of the proposed the industrial cluster. The location is around 11km away from the Town Centre. The facility will need to provide appropriate amenities for the truck drivers and operators, including vehicle maintenance facilities, toilets, and shops.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms Potential Funding

› Develop a truck terminal › Terminal amenities such as toilets, shops, vehicle maintenance facilities › (Cost of land acquisition not included) › CAPEX of developing truck terminal + amenities

KES 150k - 200k per sqm › Annual OPEX of truck terminal

KES 15k per sqm › Easy access to the industrial cluster › Ease road congestion at the Town centre › Improved road safety › Support local economy through trade at the station › Provision of public services such as health care at the station › Local tourism › Malindi Municipal

Council › Private sector funded public projects procured in accordance with the PPP act 2013 › Public funding - potentially from National government or international development partners › Private sector funding through concession - private entity builds and maintains truck parking station and enjoys the rights to collect rental income from commercial space. In turn the private party pays a prescribed concession / lease fee to the city council Challenges

› May require land acquisition › Funding › Buy-in from the local stakeholders › Buy-in from the truck operators › Pre-feasibility and feasibility studies › Public consultation › Immediate term › Must have enabling infrastructure

Data Gaps Time Frame Priority

Figure 44 - Proposed location for truck terminal

INDUSTRIAL CLUSTER (AIRPORT) Solar Canopies for Truck Park and Car Parks 4

Provision of solar PV canopies over the new truck park and car parks.

Sub-Component Estimated Cost Impacts

› Detailed study of commercial arrangement › Financial modelling › Community / stakeholder engagement plan › Initial technical design, economic, social and environmental analysis › Development of procurement and deployment / implementation plan › Operation plan (including revenue collection, maintenance etc.) › Benchmark:

USD $1,600 per kW › Actual:

Truck Park (100kW)

USD $160,000

Car parks (100kW)

USD $160,000 › Funding (eqpt, installation, maintenance):

Part IFI, part public funded › Reduced carbon emissions › More grid power available for other uses › Improved health, safety and security (through provision of under canopy lighting) › Coordination with Malindi

Municipal Government and other interested parties › Partnering with local / regional solution providers and equipment specialists to determine appropriate design and technology solutions › Maintenance - capacity building programme to ensure continued operation of systems › Maintenance - responsibility

Municipal govt

Delivery Mechanisms

Challenges

› Perceived high cost of solar canopies › Funding Data Gaps

› Detailed information on truck / car park sizes and locations Time Frame

› Short to mid-term

Case Study: SolarAfrica is a solar energy solutions provider that offers tailored solutions for businesses, residential energy users and large commercial and industrial sites in Africa. They are based in South Africa, Kenya and Mauritius. They fund and own the solar panel system, but commit to provide the users with reliable energy that is cheaper than the utility supply, and take care of maintenance. The user doesn’t expend any capital, but enters into a long term contract with SolarAfrica utilising one of two options; paying only for the energy they use, or paying a fixed monthly fee where they can use all the energy that the facility generates. SolarAfrica completed the installation of an 858kW solar PV system at Garden City Mall in Nairobi, Kenya. The system covers 32 acres of the mall car park, and provides electricity to the nearby mall and additionally provides shading to cars during the daytime, as well as lighting (underneath the canopy) during the evening/night.

INDUSTRIAL CLUSTER (AIRPORT) Power to Service the Malindi Industrial Cluster site

On-site distribution

Power distribution on site will comprise a new Medium Voltage (MV) (11/0.4kV) 1,250kVA transformer at a main site entrance. This only needs to be a pole mounted transformer. New Low Voltage (0.4kV) distribution around the industrial cluster will follow the access roads with individual connections into each unit. This will only cover Phase 1, with no capacity for the future expansion of site. Off-site connection

There are three options to get power to site: 1. Connect from an existing local MV supply. This is likely to be along the B8 road.

The capacity of the 11kV distribution infrastructure could be too small, and until tested it should be assumed that it lacks suitable capacity; 2. Upgrade of existing MV distribution from main alignment on B8 road with new spur to site; 3. New MV distribution from Primary 33/11kV substation to site. MV distribution for both options 2 and 3 should be sized for future demands beyond phase 1, estimated at around 6-8MVA. There is not potentially much difference between options 2 and 3. At this stage, option 3 has been selected as a worst case, but the technical solution will need to be confirmed with Kenya Power (KPLC) at the appropriate time.

Sub-Components Estimated Cost Impacts (Benefits) Delivery Mechanisms

› Establishment of power demand for first stage of cluster › Design of system from suitable connection point to site › Development of procurement and deployment plan › Maintenance plan › Benchmark: KES 4.5 million per kilometre plus cost for substation works › Based on 4km distance from primary substation to site › Funding (eqpt, installation): › IFI / donor finance › Consistent service provision for businesses in the cluster › Engage with KPLC to help design, procure and deploy system › Maintenance - responsibility of KPLC

Challenges

› Engagement with KPLC › Funding Data Gaps

› No knowledge of correct technical solution Time Frame

› Short term

Public water supply from Malindi may not be adequate to support the activities of the industrial cluster and a private source and additional treatment is likely to be needed. Groundwater from boreholes will be better quality (subject to confirmation through lab tests) and more resilient to drought and climate change than surface water sources. Volumes of water needed for the planned development in phase 1 and phase 2 are included in Table 1. Limited data on borehole yields in the area was available, therefore further investigations in this area are required. For cost purposes a yield of 11m3/hr is assumed, equating to 2 boreholes in Phase 1 and an additional 2 boreholes in Phase 2. Additionally, an allowance has been made for storage of a days water demand. Due to the proximity of the industrial cluster to the airport, wastewater will be treated in a closed package plant. The plant will not utilise open ponds which could attract birds, as these can be hazardous to aircraft. The treatment plant has been sized to treat 85% of the planned water supply. Sludge will be transported by tanker to the planned value chain Sludge processing plant at the existing solid waste landfill site. Discharge from the plant should be of sufficient quality to reuse for irrigation of surrounding areas, washing (non-food areas), flushing toilets and as fire protection.

Table 1 - Required Volumes of Water for Phases 1 and 2

UK to provide 1.5 Practice Manual for Water Supply in Kenya

Industrial Units (Type 2: 1,500 sqm per unit) 3 Practice Manual for Water Supply in Kenya

Industrial Units (Type 3: 2,500 sqm per unit) 5 Practice Manual for Water Supply in Kenya

Fish Processing Facility (Assuming 5 ton per day) m3 / day Source

Phase 1

Food Processing Facility (Assuming 10 ton per day) 46 Guidance for Fish Processors on Water and Effluent Minimisation

212.7 Practice Manual for Water Supply in Kenya

Total Phase 1 268.2

Phase 2 Industrial Units (Type 1: 750 sqm per unit) 1.5 Practice Manual for Water Supply in Kenya

Industrial Units (Type 2: 1,500 sqm per unit) 3 Practice Manual for Water Supply in Kenya

Industrial Units (Type 3: 2,500 sqm per unit) 5 Practice Manual for Water Supply in Kenya

Industrial Units (Type 4: 10,000 sqm per unit) 20 Practice Manual for Water Supply in Kenya

Industrial Units (Type 4: 12,500 sqm per unit) 25 Practice Manual for Water Supply in Kenya

Feed Mill

Fish Hatchery

Cassava Processing Centre 10

12

125 ADCP/REP/84/21 - Inland Aquaculture Engineering

ADCP/REP/84/21 - Inland Aquaculture Engineering

An Assessment of the Impact of Cassava Production and Processing on the Environment and Biodiversity

Total Phase 2 201.5