A

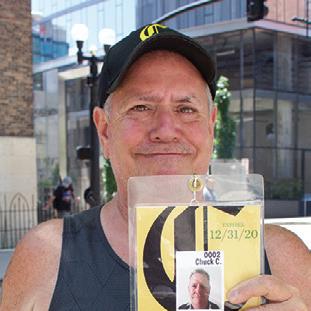

Chuck C., Vendor #0002, has been selling The Contributor for 12 years, but that's not even the most interesting part.

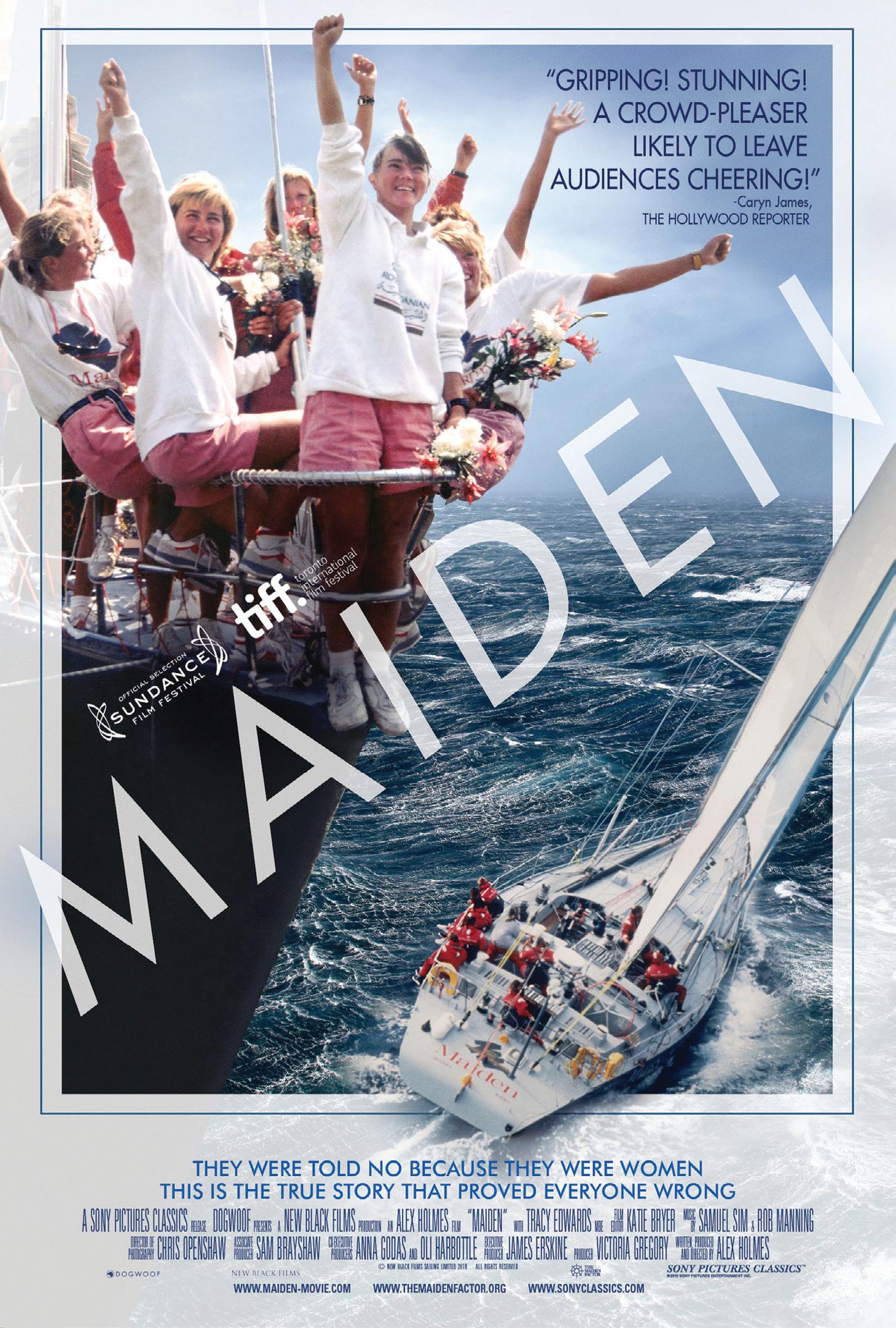

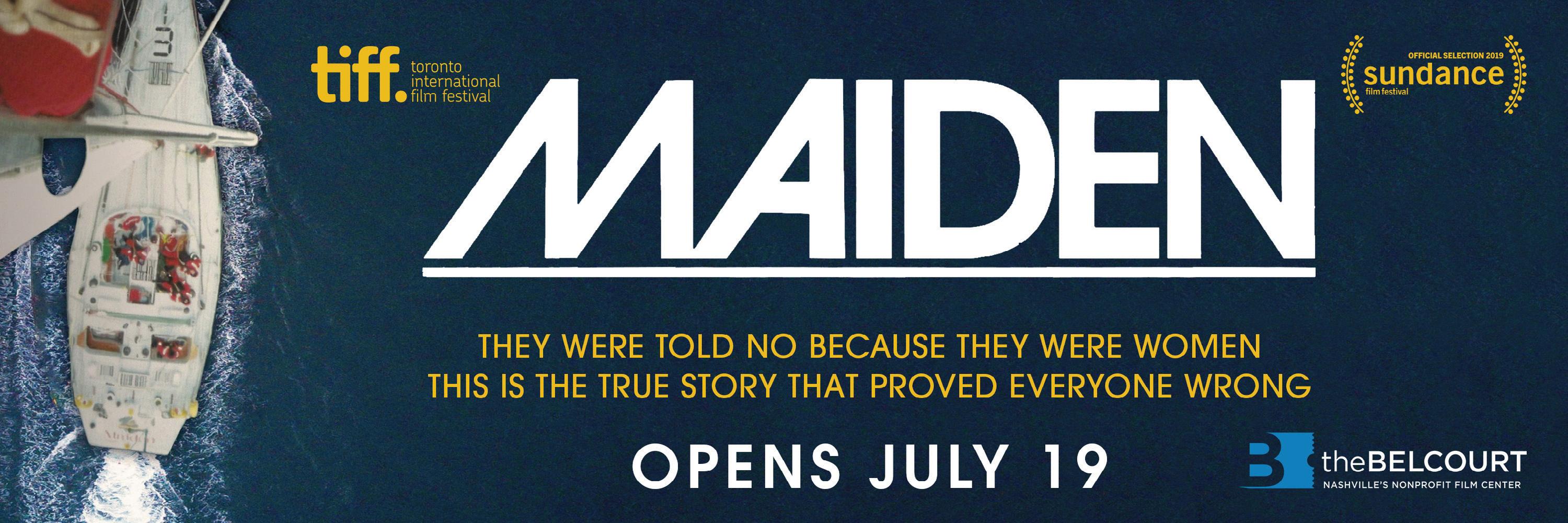

Joe Nolan reviews Maiden, a documentary about women sailors competing at a race in the '80s, when the sport was dominated by men.

Our vendors write in this issue about dogs, Father's Day, racism, open paths, limitations, eyes, and learning to get away.

Contributor Board

Cathy Jennings, Chair Tom Wills, Bruce Doeg, Demetria Kalodimos, Ann Bourland

Amanda Haggard • Linda Bailey • Iris Gottlieb • Tom Wills • Hannah Herner • Laurie Goering • Ridley Wills II • Lindsey Krinks • Joe Nolan • Michael "Smiley" G. • Harold B. • David "Clinecasso" C. • Ken J. • Victor J. • Chris W. • Mary B. • Theresa S. • Mr. Mysterio • Cynthia P. • June P. • Jamie W. • Maurice B. • Loum O. • Henry Nicholls

Cathy Jennings • Tom Wills • Joe First

• Andy Shapiro • Michael Reilly • Ann Bourland • Patti George • Linda Miller •

Deborah Narrigan • John Jennings • Barbara Womack • Colleen Kelly • Janet Kerwood • Logan Ebel • Christing Doeg • Laura Birdsall

• Nancy Kirkland • Mary Smith • Andrew Smith • Ellen Fletcher • Anna Katherine Hollingsworth • Michael Chavarria

Will Connelly, Tasha F. Lemley, Steven Samra, and Tom WIlls Contributor Co-Founders

Editorials and features in The Contributor are the perspectives of the authors.

Submissions of news, opinion, fiction, art and poetry are welcomed. The Contributor reserves the right to edit any submissions. The Contributor cannot and will not endorse any political candidate.

Submissions may be emailed to: editorial@thecontributor.org

Requests to volunteer, donate, or purchase subscriptions can be emailed to: info@thecontributor.org Please email advertising requests to: advertising@thecontributor.org

Mailng Address

The Contributor P.O. Box 332023, Nashville, TN 37203

Editor’s Office: 615.499.6826 Vendor Office: 615.829.6829

Proud Member of:

Printed at:

Follow The Contributor:

Copyright © 2018 The Contributor, Inc. All rights reserved.

BY TOM WILLS, CO-FOUNDER

BY TOM WILLS, CO-FOUNDER

The paper you just paid for was bought by someone else first, otherwise it wouldn’t exist. That’s how The Contributor works. A vendor who experienced homelessness paid 50 cents for this paper and then sold it to you. By buying it and taking it with you, you’ve just encouraged that vendor to buy another. BOOM! That’s the solution. Now keep reading. This paper has something to say to you.

Street papers provide income for the homeless and initiate a conversation about homelessness and poverty. In 2007, The Contributor founders met at the Nashville Public Library downtown to form one. In a strike of lightning we named it The Contributor to infer that our vendors were “contributors to society,” while their customers could contribute to their work. But, thunder from lighting is always delayed …

It took three years, but Nashville embraced us like no other city in the world. The Contributor became the largest selling street paper per-capita on the globe. And today 50 percent of our six months or longer tenured vendors have found housing. BOOM! The thunder has struck.

The Contributor is a different kind of nonprofit social enterprise. We don’t serve meals or provide emergency shelter. We don’t hire people in poverty to create products or provide a service. Rather, we sell newspapers to homeless people who work for themselves. We train them to sell those papers to you, keep the money they earn, and buy more when they need to replace their stock.

Our biggest fans don’t always get this. Like lightning without the thunder, they see the humanity of the vendor but misunderstand the model. Case in point: In 2013 during a funding crunch, a representative of one of Nashville’s biggest foundations exclaimed, “I’m such a big fan that I never take the paper!” We responded, “Well, that’s why we are in a funding crunch.” BOOM! Thunder was heard. Taking the paper makes our model work — not taking it breaks it. And selling the paper twice doesn’t just fund the paper, it funds housing and change. BOOM! Our vendors report their sales to qualify for subsidized housing and even for standard housing deposits and mortgages. They don’t consider your buying the paper a “donation.” It is a sale. When they sell out, they buy more and build the paper trail of a profitable business. Until making these sales, many of our vendors had never experienced the satisfaction of seeing their investment pay off. And when it does, it liberates! They have become “contributors” to their own destiny. And Nashville has become a city of lightning and thunder. BOOM! Now that you are a SUPPORTER , become an ADVOCATE or a MULTIPLIER You are already a SUPPORTER because you know that taking the paper makes the model work. You bought the paper and you are reading it. Now your vendor is one copy closer to selling out, which is exciting! Now you can become an ADVOCATE when you introduce your friends to your favorite vendor, follow us and share our content on social media, contact us when you witness a vendor in distress or acting out of character, or explain why others should pick up a copy and always take the paper when they support a vendor. And, you can become a MULTIPLIER when you advocate for us AND directly donate to us or become an advertiser or sponsor of The Contributor. Our income stream is made of 50-cent- at-a-time purchases made from our vendors, matched by contributions, ad sales and sponsorships from multipliers like you. Because our vendors are business owners, your donations are seed-money investments in their businesses and multiply in their pockets. Every donated dollar multiplies four-to-seven times as profits in the pockets of our vendors. Thanks for contributing.

El periódico que usted acaba de pagar fue primeramente comprado por alguien mas, de otra manera no existiría. Así es como funciona The Contributor. Un vendedor que está sin hogar pagó 50 centavos por este periódico y después se lo vendió a usted. Al comprarlo y llevarlo con usted, usted animo a este vendedor a comprar otro. BOOM! Esa es la solución. Ahora continúe leyendo. Este periódico tiene algo que decirle. Los periódicos vendidos en la calle proveen ingresos para las personas sin hogar e inicia una conversación sobre lo que es la falta de vivienda y la pobreza. En el 2007, los fundadores de The Contributor se reunieron en una librería pública en Nashville para formar uno. Y como golpe de un rayo, le llamamos The Contributor para dar a entender que nuestros vendedores eran “contribuidores para la sociedad,” mientras que los consumidores podrían contribuir a su trabajo. Pero, el trueno siempre tarda más que el rayo. Nos llevó tres años, pero Nashville nos acogió como ninguna otra ciudad en el mundo. The Contributor se volvió uno de los periódicos de calle más vendido en el globo. Y hoy el 50 por ciento de nuestros seis meses o más de nuestros vendedores titulares han encontrado casa. BOOM! Ha llegado el trueno.

JENNINGSThe Contributor es una empresa social sin fines de lucro muy diferente. Nosotros no servimos comida or proveemos alojo de emergencia. No contratamos gente en pobreza para crear productos or proveer un servicio. En vez, nosotros vendemos periódicos a las personas sin hogar para que ellos trabajen por ellos mismos. Nosotros los entrenamos como vendedores, ellos se quedan el dinero que se ganan, y ellos pueden comprar más cuando necesiten reabastecer su inventario.

Nuestros mas grandes aficionados no entienden esto. Como un rayo sin trueno, ellos ven la humanidad de el vendedor pero no comprenden el modelo. Un ejemplo: En el 2013 durante un evento de recaudación de fondos, uno de los representantes de una de las fundaciones más grandes de Nashville, exclamó: “Soy un gran aficionado, y es por eso que nunca me llevo el periódico.” Al cual nosotros respondimos: “Y es por esa razón por la cual estamos recaudando fondos.” BOOM! Y se escuchó el trueno! El pagar por el periódico y llevárselo hace que nuestro sistema funcione, el no llevarse el periódico rompe nuestro sistema. Y el vender el papel dos veces no da fondos para el periódico, pero da fondos para casas y causa cambio. BOOM! Nuestros vendedores reportan sus ventas para calificar para alojamiento subvencionado y hasta para una casa regular, depósitos e hipotecas. Ellos no consideran el que usted compre el periódico como una “contribución” pero más lo consideran como una venta.

Cuando se les acaba, ellos compran mas y asi logran establecer un negocio rentable. Hasta que lograron hacer estas ventas, muchos de nuestros vendedores nunca habían experimentado el placer de ver una inversión generar ganancias. Y cuando logran hacer esto, da un sentido de Liberación! Ellos se han vuelto contribuidores de su propio destino, y Nashville la ciudad de el trueno y el rayo. BOOM!

Ahora que te has vuelto nuestro SEGUIDOR, vuelve te en un ABOGADO o un MULTIPLICADOR. Ya eres nuestro SEGUIDOR, porque sabes que al llevarte este periódico sabes que esto hace que nuestro modelo funcione. Compraste el papel y lo estas leyendo. Ahora nuestro vendedor está a una copia más cerca de venderlos todos. Que emoción!

Ahora que te has vuelto nuestro ABOGADO cuando presentes a tus amigos a tu vendedor favorito, siguenos y comparte nuestro contenido en social media, contactanos cuando seas testigo de un vendedor actuando de manera extraña o fuera de carácter. O explicale a tus amigos porque ellos deben de llevarse el periódico cuando ayuden a un vendedor.

Te puedes volver un MULTIPLICADOR cuando abogues por nosotros, Y directamente dones a nosotros o te vuelvas un anunciador o patrocinador de The Contributor. Nuestra fuente de ingresos consiste en ventas de 50 centavos hechas por nuestros vendedores, igualadas por contribuciones, venta de anuncios, y patrocinios de multiplicadores como usted. Porque nuestros vendedores son dueños de negocios, las donaciones que den son dinero que es invertido y multiplicado en sus bolsas. Cada dólar donado se multiplica de cuatro a siete veces en la bolsa de nuestros vendedores. Gracias por Contribuir.

London high-school student Anna Taylor used to lament the lack of protest over what she saw as the growing threat of climate change — until her friends told her it was time to act.

"They said, 'Instead of complaining, why don't you actually do something about it'," she remembered.

So last December, inspired by teenager Greta Thunberg's lone climate protests outside Sweden's parliament, Taylor met with other students in south London, where they set up the UK Student Climate Network and began planning a first protest for February.

"We thought we might get 100 people maximum," said the 18-year-old in an interview during London Climate Action Week.

Instead 5,000 turned up in London — and 10,000 across the country. It was "way bigger than I ever anticipated," she said.

Taylor has just finished her taxing final high-school exams while simultaneously helping run a high-profile national campaign on climate change.

"I'm not really sure how I survived," she admitted. "I never would have thought it would have grown this quickly."

"A lot of the time I think I'm dreaming, to be honest," she added. But "it's a really powerful time to be a teenager".

Just how powerful is evident in British politics. After increasingly disruptive protests by students skipping school and Extinction Rebellion activists, Britain in May became the first country to declare "a climate emergency."

Last week, the government committed to reducing its planet-warming emissions effectively to zero by 2050.

Those moves are just a start in Taylor's view.

"We're not discussing the climate crisis as much as we should be," she said.

Negotiations over Brexit — Britain's troubled plan to leave the European Union — are pulling attention from more serious issues such as climate change and the environment, Taylor said.

"It's time we should be working together - and we need to be working together - to tackle climate change," she said.

Britain needs "a new government that takes the climate crisis as its priority and understands the deep connection between (that) and social and economic inequalities", she said.

For now, she and her peers feel "betrayed by the politicians that talk and talk and talk, and fail to act".

But as the young climate strikers gain the vote — one of the movement's de -

mands is to lower Britain's voting age from 18 to 16 — that may well shift, Taylor said.

"We should stop waiting for politicians to change and start replacing them," she told business, government and civil society leaders at a climate week event, to thunderous applause.

Companies and individuals also need to step in and quickly do all they can to reduce emissions, she urged.

"We're calling for you to make the changes and stand alongside us as we take drastic climate action," she said.

Taylor — straight-talking and quietly confident — coordinates with her loose but fast-expanding network of activists largely online, using social media and other tools.

And the protests are quickly growing in size. London has seen up to 20,000 students turn out, she said, with 50,000 joining a weekly strike across Britain.

Thunberg's example, of solo vigils outside the Swedish parliament, combined with pointed warnings about climate threats in a flagship science report released last October, are driving growing student involvement, Taylor said.

Some schools have supported their pupils taking Fridays off to join the protests, while

others have banned them from attending or even suspended them from school, she noted.

Meanwhile, inside the classroom, education on climate threats remains mostly inadequate, she said.

"In the last nine months I've learned more than I had the entire time at school," she said.

Reform of Britain's national curriculum "to address the ecological crisis" is one of the movement's demands.

Internationally, student activists are now preparing for their next big school strike on Jul 19 — and in Britain they’re planning for one in September, which they think will be the largest general strike in Britain since 1926, pulling in adult members of the public too.

Nearly a century ago, 1.7 million workers stopped for three days to protest an effort by the British government to cut wages and protection for coal miners.

This time, students are hoping their parents and many others will join them on the streets to demand swift action on climate change stoked by the burning of coal and other fossil fuels.

"Students recognise the threat to our future and now the public is beginning to recognise that as well," Taylor said.

Courtesy of Reuters / Thomson Reuters Foundation / INSP.ngo

In 1880, W.W. Clayton wrote, in a history of Davidson County, “Fisk University is the leading institution in the great Southwest for the education of colored people.”

In October 1865, Fisk was born as a school for black students in several abandoned hospital buildings known as the Railroad Hospital. Located near the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad Depot, the school was sponsored by the American Missionary Association, and the Western Freedmen’s Aid Commission. Fisk School and later Fisk University were named in honor of General Clinton B. Fisk.

Following the war, General Fisk, “an avowed abolitionist who neither drank nor swore,” was named assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau for Kentucky and Tennessee.

He is considered the founder of Fisk University, which was chartered on Aug. 22, 1867.

By 1870, the university buildings and location were inadequate for a school of such promise and popularity. George L. White, music teacher at Fisk since its early days, came up with the idea of taking his small company of student singers to the North to sing popular songs and raise money to purchase a more appropriate site for the school. The singers raised $20,000 by May 1872.

In the spring of 1874, White took his singers, who were known as the “Fisk Jubilee Singers,” to England, where they were received enthusiastically and where they performed before her Majesty the Queen. In a year abroad, during which time they toured six

countries, the Jubilee Singers raised $150,000.

Fisk built a chapel in 1892, a superb example of High Victorian Picturesque architecture. The Fisk Memorial Chapel features a Romanesque arched and columned front entrance, flanked by twin stone and stucco towers and a tall bell tower pierced by Gothic stone windows.

The most imposing of the 20th Century buildings on the Fisk campus is the Administration Building, and Erastus Milo Cravath Library, built in 1929 and named for the first president of the university.

In 1930, Fisk became the first African-American institution to gain accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. Twenty-three years later, Phi Beta Kappa, the nation’s oldest

and most widely known academic honor society, granted Fisk a charter to establish the first chapter of the Phi Beta Kappa Society on a predominantly black campus.

Fisk struggled financially during the 20th Century. Integration brought enormous benefits to the nation, but was a mixed blessing to Fisk as outstanding African-American high school seniors, who in the segregation era would have chosen to go to Fisk or one of the other highly-rated African-American schools, could then go to Princeton, Yale, Harvard and other highly-rated historically white universities. Fisk remains a predominantly African-American institution with a strong liberal arts and sciences emphasis and approximately 800 students.

Chuck C. holds vendor badge number 0002. For a frame of reference, The Contributor trained its 3,472nd vendor as this article went to press.

Chuck has been selling The Contributor for nearly 12 years. He remembers when it printed once every other month, just 2,000 copies distributed among six or so vendors (now we’re at between eight and 10 thousand per bi-weekly issue). He is very nostalgic about it all — and even went so far as to get a small “C” and torch from The Contributor logo tattooed on his left forearm. He chose to have his photo taken at the site of a long-gone public bench, where meetings for The Contributor used to be held. Chuck has a full-time job and an associate degree and doesn’t sell papers very often now, but he finds reasons to stick around.

Can you first tell me the story of how you ended up becoming a vendor for The Contributor?

It was right after I got into housing, Ray Ponce de Leon, the very first vendor, number 0001, told me that idea. I had been working through agencies and finishing up my time with the Kroger company, and he persuaded me to come down. I was skeptical at first because [I had] never actually heard of a street paper. At first it was very slow, people were skeptical. Businesses were skeptical about whether or not it was legitimate. Larger cities like Chicago were doing it before, but it was something that had never happened here. Ray is the one that got me to come to the first organizational meeting right in the living room of the church.

It’s been about 12 years since then, and you were telling me about some of the things you’ve accomplished in that time. I finished my time with Kroger, which I had started when I was 17. I did enough time to start drawing a pension, which I did at age 55. I went back to school and got an associate in clinical medical assisting from Daymar College, and went on to get nationally certified as a clinical medical assistant and

have been working in hotel and hospitality-related fields. I’m hoping to break into something medical soon.

Do you still get a chance to sell papers?

I do, occasionally. I’ve been at the site of my old high school, where Father Ryan High School was, at 23rd and Elliston, by the Nama sushi restaurant on the corner. I sell maybe a day or two, maybe four days a month — enough to keep my badge going. There have been some people that I have run into and have gotten to know me over the years and like to get a paper, to know what’s going on, especially transitioning from the newspaper to the magazine and then back to the newspaper. I kind of keep some people abreast of what’s going on.

Now that you have your degree do you think you’ll stick with keeping your badge up like you have been?

Oh, yeah.

And why is that important to you?

I just think it’s something they can recognize and maybe kind of be an inspiration to people that hey, this guy has been doing it since the beginning and he’s still doing it. I take this from a country music star that’s deceased, Tammy Wynette. The late Tammy Wynette kept her beautician’s license up until the time she died because she never knew when her voice was going to play out. So I’m holding on to this badge in case something [happens] otherwise. It’s also good for people to see, wow, this thing’s been going for that long when you look at the number. I have no idea the number of vendors now...

If nothing else, for nostalgia and extra income between paychecks. You never know when you might need it.

Tell me why you wanted to get into the medical field. Is that something you’ve always been interested in?

No, I was visiting a friend at an assisted living, and as I was leaving I heard a woman screaming and I happened to look

and this woman had rolled out of the bed and she was on the floor with no clothes on and the door was open. And there were aides and techs that were saying “she’s not one of my patients.” And that really bothered me, and I said they really need to have some compassionate, caring, conscientious people in health care. Having a medical clinic on our complex at Mercury Courts, I was able to see how a medical clinic like that would work, especially to the marginally poor, the working poor, and the homeless. It seemed like a natural fit for me, and that’s where I did my internship. It’s very important because they serve the underserved there.

Where do you think that compassion comes from for you?

...having been out and witnessed things that you see out on the street that normal people wouldn’t see, and probably how people have been passed up and have been created more or less a number assigned to them rather than being seen as an individual. Having seen that, I think that people need to be treated individually rather than numbers and stereotypes. Having an inside track on things, especially seeing people go months and years without medical treatment, that’s given me a great sense of compassion, for it not necessarily being their fault, but a lot not being available. Especially with the uninsured and the questions with Obamacare, how is somebody going to be able to really treat and understand if they haven’t been there?

Is there anything else you’d like to talk about?

I’d just like to challenge the community to keep taking the paper, reading the paper and know that their purchase makes a difference and there’s living proof. Hundreds of people, I could say, like myself, that have been given the opportunity to advance based on not only the purchase, but the many benefactors that are silent, that we don’t know about but probably saved the paper at one time. Thanks to the people that are supporting us.

A damp and heavy dawn thickens around the hackberry tree in my back yard. Without leaves, the limbs reach out like the wiry fingers of crones. March fog hovers above the dewed grass and I wrap myself tighter in the blanket that was once my aunt’s. My hands fold over the rim of my mug to hold in the heat and my palms warm with steam as if the coffee is breathing into them. This is my ritual when I rise before the sun, when I’m haunted and held by the ghosts that visit me. They shake the slumber from my eyes, ask questions for which there are no answers, and whisper worlds past and worlds to come. This morning, the ghost is Horace.

For the last decade, I have lived my life on the side of Nashville, Tennessee you will never see in tourist guides. I hear roaches scuttle, see bedbug bites on the bellies of children, and smell the stench and rot of untended wounds. As a homeless outreach worker, street chaplain, and housing rights organizer, I go, as one of my friends on the streets put it, “where the devil fears to tread.”

I recently met with the Emergency Department staff at a local hospital to help them better navigate the housing resources and service providers in town. As our meeting was drawing to a close, they began to ask me questions about my experiences. A social worker with a pencil skirt and neatly tucked hair leaned in, keen with interest. “What’s the worst thing that has ever happened to you?” she asked.

The room fell silent. I shifted in my seat. The worst thing? I thought. Really? Recollections of trauma rippled through my body like aftershocks of an earthquake. I managed to mask them with humor. “If you really want to know,” I joked, gripping the seat of my chair to steady myself, “you should ask my therapist.”

I don’t remember how the session ended, only that memories flooded my senses.

Police lights flashing.

My ghost-white knuckles. The smell of pavement and smoke.

Horace’s tattoos and the last words he said to me.

***

The first time I met Horace was over the phone. He got my number from Tommy, one of the men I’d helped move into housing. Horace called me because Tommy was desperately sick but refused to go to the hospital. He wanted to see if I could convince him to go. “He’ll listen to you,” said Horace. And he did. Tommy went to the hospital and Horace saved my number.

After meeting Horace in person some time later, I realized that he was the kind of guy you did not seek out. He was 5’8’’ with a small frame that held a wicked temper. His piercing steel eyes rarely warmed, and his grayish-blonde mustache flanked a near-permanent scowl. Tattoos of demons and women ran up his limbs and a grim reaper cast its shadow across his entire back. Everywhere he went, he carried two pocketknives, ready for a fight. The only time he appeared happy was when he put on his headphones and mixed a drink to drown out the voices of the ghosts that haunted him.

When Horace moved into a tent in a patch of woods on the east side of town, he asked if I would help him find housing. At first, I was hesitant. As hard as I tried, I couldn’t see him being able to maintain housing once he got it. How long would it be until he started fights with his neighbors? Failed to pay his rent? How long would it be until he was back on the streets? But there was something desperate about him. Something grave and heavy about the way he asked. It was as if he thought that working together might be his last chance to break free from the living hell of his life on the streets. Somewhat warily, I agreed. “Okay Horace,” I told him, “we’re a team now.” And we went about trying to pick up the broken pieces of his life.

Most days, Horace swam in all that was negative, spewing curses on everything and everyone with his vod-

ka-soaked breath. To try to lighten the mood, I joked with him that his nickname should be “Grumpy.” He was not amused. But then there were days when the scowl disappeared from his face, when the ghosts that haunted him lifted. On these days, he was gentle, thankful, even kind. He watched the deer at Shelby Park and fed the birds and “critters” at his camp. He gave my number out to random people he met on the bus so they could call me and “get help.” He volunteered at a local food pantry and offered to cook for our outreach team. With a grin spread across his face, he even invited me, time and time again, to partake in the cup of his suffering: Hawaiian Punch spiked with Skol vodka.

his camp, where he was convinced his campmates were stealing from him.

On a gray frigid morning in early February, Horace called me, begging for help. Some quiver in his voice made me pause, sent a chill down my spine. I scraped a thick coat of ice from my windshield and drove to meet him. Our outreach intern Haley met me in East Nashville and we found Horace huddled on a sidewalk, rocking back and forth. A charcoal beanie was pulled low over his brow and he was visibly dirty, sipping his mixed drink. This time, he was not only suicidal—he was homicidal. “I’m gonna break, I’m gonna snap,” he said. “Help me. Help me please.” As he spoke, pillars of steam issued from his lips, dissipating into the morning like prayer.

Horace agreed to “get help.” He needed to go to a hospital where he could detox safely and receive psychiatric care. We climbed in my car and turned the radio to classic rock—Horace’s favorite. My Honda CR-V wove through the shadows of a rapidly developing Nashville. We passed the shiny new police precinct and countless cranes stretching cold steel into luxury condos and expensive hotels. It was clear what class of people the new Nashville was being built to serve. And it wasn’t Horace.

Haley and I tried to keep Horace calm by talking about music and assuring him that he wasn’t alone. The song “Come Sail Away” by Styx started playing, its other-worldly piano melody dancing around us, ascending toward an invitation. As we neared the hospital, something in Horace shifted, and he began to sob uncontrollably. Was it the song? Something we said? He rocked back and forth in his seat, burying his head in his hands. “I want to go home,” he cried with unnerving conviction. “Get me out of here! I want to go home.” The misery in his voice chilled me. After his sobs subsided, I managed to ask, “What is home to you, Horace?” But he couldn’t answer. He only kept rocking back and forth, uttering the same words over and over again—“I want to go home. Get me out of here! I want to go home.”

Where was he so desperate to go? I tried putting pieces together from our past conversations to see what kind of picture they formed. Was “home” Kentucky, where he was born? Was it Knoxville or Dickson, where he lived before coming to Nashville? Was it his tent in the woods? Was it the apartment we had just filled out the application for — the one that was set to have an opening in a matter of weeks? Or was it somewhere else altogether?

His good moods, however, never lasted long. Like the hackberry tree in my backyard, Horace was layered, weathered, and deeply wounded by the years. For well over a decade, he had spun through the revolving doors of jails, prisons, and hospitals, always landing back on the streets. His past relationships were brittle, snapping like winter twigs underfoot. He had a double hernia and was in constant pain but had to wait months for surgery because he didn’t qualify for health insurance. He was on the list to get a Section 8 housing voucher subsidized by the government, but that was a waiting game, too. He tried going into detox and rehab, but two weeks in, he blew up at one of the counselors and stormed back to

When Horace was young, home was a place of abuse and loss. I sometimes wonder if we underestimate the power of past traumas, the way they ripple through our present lives. I sometimes wonder how deep in our bones our demons can bury. Horace was no stranger to trauma, to demons. When he was four or five years old, a family member slipped alcohol into his juice to calm him down. By the time he was in elementary school, he knew how to come home and mix his own drinks to calm himself, to lessen the sting of his abuse.

Four decades later, he was still mixing drinks. When he told me how bad things were, I tried to affirm his struggles by responding, “I know.” “No!” he responded sharply. “You really don’t know. You really don’t.” And he was right. I couldn’t grasp the depths of his trauma. I could never know

how much he had lost. He was a man who had been hurt and had done his share of hurting others. So he withdrew. He self-medicated. He isolated in feeble attempts to lessen the damage. If he was alone in the woods, no one could hurt him and he couldn’t hurt anyone else. Right?

That gray February morning, Horace was admitted to the hospital. In less than 24 hours, however, he left AMA — against medical advice. How had he not been involuntarily committed? Had he spun lies to say he felt better, that he no longer wanted to hurt himself or someone else? When Horace returned to his camp, tensions ignited, and more arguments and fighting followed.

A couple days later, on my 31st birthday, I took him to another hospital after he begged for help. He assured me that this time, he would stay, but a few hours later, before they could get him a bed, he left. He hated being confined, poked, and prodded. “It’s like being in jail again,” he said of the hospital. Something in him felt caged when the walls closed in. Despite his hatred of walls, however, I’ve never seen someone long for his own apartment the way Horace did.

Two days later, on Transfiguration Sunday, my phone rang. It was late, but I recognized the number. The call was from Jack, a fellow outreach volunteer. “Something happened,” he said, his voice unraveling. “Can you meet me at Horace’s camp?” I left the house in a matter of minutes, my heart beating against my ribs like the wings of a trapped bird. My hands trembled as I drove, as darkness gathered overhead.

Transfiguration Sunday invites us into the story where Jesus is said to have undergone a strange transformation. In the Gospel of Luke, this story comes after Jesus sends the disciples from village to village to drive out demons and heal the sick, after he miraculously feeds the five thousand and begins hinting that his own death looms on the horizon. As the story unfolds, Jesus leads Peter, James, and John up to a mountain to pray. While they are praying, Jesus’s body begins radiating. His face and clothes become blinding, “as bright as a flash of lightning,” says Luke. He is changed. Transfigured. Light pours through him. The ghosts of Elijah and Moses appear, and the disciples are astounded. They stumble over their words, saying that perhaps they could set up some tents for the unexpected guests. Then, a thick cloud wraps around them and a voice issues from the shifting haze. After the voice speaks, the cloud dissipates, the ghosts lift, and the disciples are stunned into silence as they descend down the mountain.

As I drove to the camp, thoughts of Horace and the transfiguration swam through my mind. My hands were shaking, my knuckles white from gripping the wheel. A dizzying number of blue police lights burned my eyes as I pulled up to the camp’s entrance. The road ahead was blocked and officers were taping off the area. My stomach dropped. Emptiness filled me. I was a balloon, lifting, anchored only by a fraying string. I floated out of my body and looked down at the scene.

Do you know if Horace had any tattoos on his legs? the voice of an investigator asked.

The me below answered, yes, and described the woodland man tattooed on his left leg. The body they found at the camp had been burned beyond recognition with fire as bright as lightning. The neighbors had noticed the smoke and called the police. The tattoos I described matched the body they found. It was Horace.

My string frayed even more and I began to drift away. What happened? Where were his campmates? I knew all the men well. I hovered further outside myself, felt the world blur and darken like a nightmare from which I couldn’t wake.

Gradually, the investigators filled in the details. There

had been a fight between Horace and one of his campmates, Jordan. It escalated beyond control. Scuffle marks and the blood of both men splayed on winter soil throughout the camp and around the fire pit. Only one survived. Jordan was younger, stronger. He had his own ghosts, his own way of numbing their voices. Before Jordan fled, he tried to cover his tracks by setting his own camp on fire and frantically burning the evidence that cried out against him. What had he done? Perhaps Horace didn’t feel the flames, the investigators said. Perhaps he was already unconscious, knocked out by the large rock that was found beside his body.

Well after midnight and still in shock, Jack and I drove around the east side with Julie, another outreach worker, looking for Jordan. We knew many of his hiding spots. Perhaps if we found him, we could convince him to turn himself in. Perhaps we could make sure there were no more casualties. As we drove, the streets and homes around Shelby Park were eerily quiet, unaware of the horrors that

Conde-Frazier, speaking to a group of students and ministers, “is the curiosity of what to do with brokenness. When Jesus ascended into heaven,” she continued, “he took his wounds with him. Why? What is it that comes from brokenness?” Dr. Conde-Frazier’s words poured back through the recesses of my mind as I thought of Horace and the deer. She talked about how a broken bone that is not set correctly “heals falsely.” It heals, but is not whole. In order for it to be made whole, it must be re-broken, reset. Just as healing oil is released when olives are crushed and pressed, we sometimes find our own healing through our wounds. So what are we to do with brokenness?

***

The hackberry tree in my backyard is an unsightly tree. Scars climb the length of its trunk and many of its branches have snapped off, leaving disfigured nubs. Some branches reach spindly twigs toward the sky, while others bow low over our lawn, laden with their own deadening weight. When my husband and I moved into this house, several people told us we should cut the tree down, have it removed. Perhaps they were right. What if one of the larger limbs fell on our porch, our fence, our roof? But something in that tree calls to me. I know the different holes and hollows where starlings roost, where cardinals build their nests and raise their young. I see life in its scars and love the summer shade it brings. Perhaps we’ll find someone who can help us prune away what is dead. But until then, the dead and living branches will continue to sway together, singing songs of brokenness and praying God knows what. From time to time, beneath the hackberry tree or near the Cumberland River when the morning haze hovers above the water, Horace visits me. It is mostly his unwavering steel eyes that I see. Some days they seek answers, on the prowl like a hawk flying low in ever-narrowing circles. Some days, the frantic words he said in the car that day — “I want to go home” — replay over and over in my mind, skipping like a record on repeat. “What is home to you?” I whisper into the fog. Other days, his eyes soften. He tells me everything is okay and offers to make breakfast for our outreach team. We sit around his campfire beneath a fraying blue tarp. Pots and pans hang from nails on a nearby tree. A mockingbird sings over us, her notes crisp and piercing, edged in sorrow and strength. Horace is wearing his favorite camo shirt, blending into the woods around him. He smirks as he holds out the spiked Hawaiian Punch to me again. An offering. Here is my body, broken. Here is my blood, poured out. This time, I take a drink. Welcome home.

had taken place. Horace was killed while everyone ate their dinners, while children prayed their nighttime prayers and fell asleep in their parents’ arms.

The air thickened as we neared the Cumberland River. A late-night mist settled along the riverbank, spilling low over the grass of the park. We got out of the car and left the headlights on to walk to an old camping spot. Two beams burned through the fog, and as it drifted, the light fell on half a dozen deer grazing in a field. Their necks bent low, but when they heard our steps, their sleek heads lifted, turning toward us in unison. Among the deer was a wounded buck with only one set of antlers. My breath caught in my chest when I saw him. He held his head high, the single ashen branch stretching toward the moonless sky. Our eyes locked. I felt his heart quicken. An instant later, the buck bolted. I held my breath as he raced through the fog, as his phantom hooves kicked up evening mist from the grass.

“What we’re holding now,” said theologian Elizabeth

This piece of writing was first published by the Nashville Review: It was the 2019 Porch Prize Winner in Creative Nonfiction.

KRINKS grew up in the foothills of South Carolina and moved to Nashville in 2003. She is the Co-founder and Education Coordinator of Open Table Nashville, an interfaith homeless outreach nonprofit. For over a decade, Lindsey has worked on the “underside” of Nashville — the streets, encampments, jails, slums, and underpasses — while also working with faith leaders, community organizers, and public officials to make the city more equitable, hospitable, and just. Lindsey blogs at drybonesrattling.wordpress.com and, on any given day, she can be found in tent cities, working on a variety of writing projects in a coffee shop, or foraging for native herbs and plants.

LINDSEY

Just as healing oil is released when olives are crushed and pressed, we sometimes find our own healing through our wounds. So what are we to do with brokenness?

In the first frames of Maiden, massive, stormy ocean waves engulf the screen in slow motion while a number of women speak in voice-over: “The ocean is always trying to kill you. It doesn’t take a break;” “The probability of just not making it is high;” “You’re on your own. There is no hope if anything happens.”

Another wave. The screen cuts to black then slowly fades in on a tan young woman with a shy-smiling face, athletic shoulders and a deep suntan. She looks into the camera and introduces herself, “Hello, I’m Tracy Edwards, skipper of Maiden, the first all-female challenger in the Whitbread Round the World Race.”

The race was named for the brewer that sponsored the triennial globe-circling regatta. The 1989-1990 iteration that’s featured in the new documentary Maiden started in Southampton in Hampshire, England, before departing for ports in Uruguay, Australia, New Zealand and the U.S. before racing back to England — 30,000 miles.

Edwards was a happy child whose mother was as sporty as she was liberated — she met Edwards’ father while she was a competitive go-

cart racer and he was her engineer. Her father became a successful entrepreneur in the hi-fi audio market before dying of a heart attack when Edwards was 10 years old. Her mother tried to take over the audio business, but the male-dominated industry eventually froze her out. She married an abusive alcoholic in what reads like a desperate move to provide for her daughter. In high school Edwards was suspended 26 times

before being expelled and becoming a runaway. She met a boat skipper at a bar and joined his crew as a steward. Out at sea she found a family of misfits and outsiders, and she learned how to sail. Maiden isn’t a Tracy Edwards biography, but these details tell us a lot about how she became the captain of this pioneering crew.

Yacht sailing in the 1980s was a space dominated by men. Those yachtsmen were

seeking adventure, glory, and prizes. The Whitbread race offered no cash prize as competing in such an esteemed contest was seen to be its own reward, and established yachtsmen agreed that Whitbread’s circumnavigation challenge was the ultimate test for a sailing captain and his crew.

Director Alex Holmes tells the tale of the Maiden, her captain and crew by combining archival film, television reports and profiles alongside new interviews with a host of boat captains, crew members and journalists who offer their own takes on these women sailors who insisted on their place in a race that nearly none of their male peers thought they could finish. The vintage images from the archival footage look great and these remarkable sailing women are wonderful tellers of their own story — and that’s the real magic here. It’s a savvy choice by Holmes to present this mariner’s yarn sans frills or cinematic experimenting because this true story about remarkable daring women wins the audience on its own terms.

It’s natural that some will want to interpret Maiden as a salty feminist fable, but that would mean ignoring the actual women the film celebrates. In one archival scene a reporter asks Edwards about feminism and she tells him she hates the word. And while there is lots of empowered boundary breaking celebrated in this film, Edwards isn’t interested in being co-opted as a symbol for a movement. Recalling the lead-up to the race Edwards says: “We were living in this parallel universe where everyone else thought we were going to die and we thought we were going to win.” We may want to make these womens’ stories underscore a contemporary cultural agenda, but what they’ve always wanted is to be respected as the smart, gritty, professional competitive sailors that they always knew they were.

Aye aye, captain.

Maiden opens at the Belcourt Theatre on Friday, July 19. Go to www. belcourt.org for times and tickets

It is the same for all of us. We are each given one life — just one. But there the similarity ends, because no two lives are the same. Each of us is unique – even identical twins have different personalities.

We develop our own relationships and skills. We make choices that determine how our lives will unfold.

Also, we are open to the ‘unknown’ — things that happen to us. We cannot choose how others will react to us, or select how many welcome or unwelcome circumstances may come into our lives. These things affect us all as individuals — and we react in different ways.

We each develop preferences — things we like or dislike, find helpful or unhelpful. Yet however we develop, we only have one life.

We all experience that moment when we realize, “Life is not a rehearsal. This is the only life I’ve got.”

It’s the same for all of us.

What will I do with today, this hour, this minute... my one life.

Life is a Story of Self Life is a story of self in community. The community determines the quality of life opportunities.

You determine your quality of life goals. Your life become part of the quality of community we experience.

Reflecting Quality of Community In the Lives of Others Increases the Quality of Life of Us.

Major Ethan Frizzell serves as the Area Commander of The Salvation Army. The Salvation Army has been serving in Middle TN since 1890. A graduate of Harvard Kennedy School, his focus is the syzygy of the community culture, the systems of service, and the lived experience of our neighbors. He uses creative abrasion to rub people just the wrong way so that an offense may cause interaction and then together we can create behaviorally designed solutions to nudge progress. Simply, negotiating the future for progress that he defines as Quality of Life in Jesus!

I matter

My Pain and My Fears Matter

My Life and My Dreams Matter You matter Your Pain and Your Fears Matter

Your Life and Your Dreams Matter

I acknowledge your humanity

I assert mine

As life matters, we both matter You and I

~Athol Williams Social Philosopher

MICHAEL "SMILEY" G.

MICHAEL "SMILEY" G.

There’s a bridge you should not cross There’s a path just for the lost Over and beyond a haunted mountain pass

No turning ‘round No coming back

Some tend to call darkness, their friend and home Some quit dreaming Left to roam

Though light is always the road to find Some will not look they remain blind

Keep on a road though hard, but true

Honest character will see you through Be sure though to say a prayer

For a greater One has blessings to share

BY DAVID "CLINECASSO" C ,FORMERLY HOMELESS VENDOR

The sun’s shining bright In some pretty eyes That’s really all right Blue are the skies

Truly thankful Really having a ball Most I can say That’s almost all

In the blink of the eye without a moment’s notice life can change so unaware light goes out did not see life to be what surrounds do not know to disconnect curtain draws

Things in life have limits

Cars have limits

Money has limits

People have limits

But love has no limit

I had some interesting dogs through the years, but the one I will never forget is Bocephus.

I was told he was a beagle when I first got him, but as he grew you could tell he wasn’t. His legs were way too long and I doubt he even knew what a rabbit was. I left him with my mom and pa when I first moved to Tennessee 30 years ago, and when I moved back, he would not hunt. I think he was brainwashed by my mom. (Plus, my girlfriend at the time was nicknamed Bunny — maybe that was it!) What he lacked as a hunting dog, he made up for with heart.

Bo did turn out to be a great truck-driving dog. I had him in about 20 states when I drove a truck. I hauled glass moulds all around the U.S. and Canada, and all the shipping and receiving people would bring food to work just for Bo. I was like, “What about me?!”

One night in North Carolina I was stopped by a state cop because my tail and bed lights were out. When I opened the door to hand him the paperwork, Bo jumped

down by my feet and was face to face with the trooper. So I had this big ’ol state cop petting and making baby talk to my dog. It was funny. He glanced up at the paperwork and said, “I don’t need that, I just wanted to tell you your tail lights are out.” Not your average interaction between a cop and a trucker.

One of my loads was to Pittsburgh International Airport where I had to drive out to the terminal on the tarmac. Bo would get so freaked out by the planes that I would leave him home. One time I called Bunny from the road and she said, “You will not believe what this dog does every night. He gets your clothes out of the hamper and lays them out in order: shirt, pants, underwear, socks.” She said she would pick up the clothes, put them back in the hamper, and the next night Bo would do the same thing. He would never do that when I was home.

Bunny wanted me to stop driving the truck because I was gone all the time, so I started a furniture repair business. To get it off the ground, I helped a friend out that

dug graves. After the service I would shovel the grave in. I would go check the grave in the morning to make sure it didn’t cave in or have water in it. One morning I checked it and left. I made it about two miles and noticed I forgot Bo. I thought, he will be fine by himself for a while. When I got back, there was still some people there — including the priest. I asked him if he’d seen a dog around.

“A black and white one?” He asked.

“Yes,” I said.

Everyone started laughing, and the priest told me that when he started the service, Bo came down between the rows of chairs and sat right in front of him and stared at him like he understood every word. I thought, oh crap. I told him I was so sorry, and the priest said, “Don’t be. That little dog brought a lot of happiness to a lot of sad people on a very dark day. Maybe he was God sent.” Maybe he was.

Years later, I was out of town working on a movie, when my mom called and said Bo died. He was 19 years old. Most dogs don’t last that long. Maybe it was his sense of humor!

In May 1909, Sonora Dodd Smart, a girl from Spokane, Wash., was in church listening to a sermon given to the mothers of the church. As she sat there listening to the pastor honoring the mothers she decided she wanted to designate a day to honor dads. Especially her dad: William Jackson Smart.

You see, her dad was a single parent. William was a widower after Sonara’s mother had passed away during childbirth. William raised six children and was a Civil War veteran.

Sonora originally suggested June 5, 1910 — William’s birthday — as a holiday to hon-

or fathers everywhere. Needing more time to arrange their sermons, the celebration took place on the third Sunday of June instead.

On June 19, 1910 young women of Spokane handed out a single red rose to their fathers during church service. The attendees were encouraged to wear a white rose in honor of their deceased fathers and a red rose in honor of their living fathers. After the service, Sonora and her young son rode through the town in a horse and buggy passing out roses to those fathers that were homebound.

Thanks to Sonora’s Father's Day celebration,

the tradition spread rapidly and gained popularity. President Woodrow Wilson celebrated Father’s Day in Spokane in 1916 during a visit to Washington. In 1924 President Calvin Coolidge urged the governments to observe Father’s Day. It was a no go, but Sonora never gave up.

In 1972, when Sonora was 90 years old, President Richard Nixon signed a proclamation making Father's Day an official holiday. It took 62 years for Father's Day to become an official holiday and it took six years for Mother's Day to become an official holiday.

In today’s world we are being challenged on all levels of our lives. The times we live in now are rife with division and just plain mean-spiritedness. This entire country is being confronted with dissolution that could prove to be more deadly than the Civil War of the 1800s. There are many of us who try to maintain some semblance of decency about ourselves. For the homeless African Americans, this presents a unique struggle to exist in a hostile social climate. The most compelling fact about today’s brand of broad-spectrum hatred is that it reaches homeless people of any race — black folks are not the only the targets of this hatred.

The lack of leadership in the spiritual and political arena has brought out the worst kind of behavior in our fellow Americans. All races, however, have to remember that there are many beacons of light, hope and decency. I will relay to my gracious readers a story of a split-second crush of negativity concerning race.

This story concerns my adventures as a Contributor newspaper vendor. My spot for sales is in Bellevue next to Walgreens. This is a predominantly white neighborhood and they have treated me very well during my time in this area of town. I have had very few encounters with racism.

One day while selling papers I noticed a man approaching the corner with huge plumes of very dense, black smoke coming from his exhaust pipe. I could just see the hatred and contempt he had for me in his face, but I like for my assumptions to be confirmed before I decide to act.

This Caucasian man proceeded to come to a complete stop at the stop sign where I’m standing, and he made sure that his exhaust was pointed directly at me so when he proceeds to take off I will be sprayed with black soot from head to toe.

It would have been a really bad scene in these racially-charged times. God was so

kind that when the man went to take off this huge cloud of black smoke came out and a soft breeze whipped up out of nowhere and blew the smoke away from me before it even hit me.

Well, I thought that was the end of it but about three cars back an elderly white lady saw the entire incident. It was so sweet what she said. She said, “All of us ain't like that.” Then she proceeded to give me a crisp $100 bill that made my day. I forgot about the racist. This story just proves it. In these trying times we must pay attention to and become beacons of hope, decency and cooperation. In a nutshell, beacons of light. This is the most powerful thing we can do for future generations.

OK, I’ve got one. Your house is on fire and you only have time to grab three things. (Let’s assume any people or animals you love are already at a safe distance.) What would you take? Would you go straight for the valuables like your collection of firstrun limited-edition Pokemon cards? Or maybe something sentimental like that picture your great-aunt painted of Don Rickles eating a corndog (or is that Dwight Eisenhower holding a microphone?). You might go for something super-practical like that box with your birth certificate, passport and old report cards in it. Make a list of your top three things. Now, imagine your life if those three things were gone. What would you do? How long would it take you to recover? Would you replace them, or just move on? It’s good to know what we’re holding on to the tightest and what we could maybe even live without.

Yikes! I think that watermelon vine just moved! No, wait, you’ve just got a snake in your garden. A startling revelation to be sure, but before you start jabbing at it with your trowel, maybe you need to take a closer look. Sure, there are a few bad ones out there, and it’s important to know when you’re dealing with somebody venomous, but most of the snakes you see around here range from harmless to beneficial. A good rat snake in your garden will go after any fuzzies that might have their eyes on your tomatoes. If you’re lucky enough to get a king snake, he’ll take care of pest-control and even keep the poisonous snakes out of your yard. The same can be said for other “snakes” in your life. Be sure you know just what kind you’re dealing with before you jump to conclusions.

The pay is good and the benefits package isn’t too shabby. The hours could be worse and there’s that two weeks of vacation time you still haven’t used. But somehow it doesn’t all seem worth the crushing sense of dread you experience every morning as you pull into your parking space. Every day you hope that the building will be closed for asbestos removal or that your boss will be lost in Sri Lanka with anti-malarial-induced amnesia; anything so that you could just turn around and go back home. Dissatisfaction is a sign that you might be ready to make a change. My only advice on the matter is that you make a plan first and stick to it. Don’t jump ship until you’re sure you know how to swim.

I can’t believe how much you have to get done this week, Libra! And I can’t believe you’re just out in the backyard pulling weeds again! Look, friend, productive procrastination can be a beautiful and worthwhile sport, but eventually you’re really going to have to come back inside and hunker down. And so, I would like to direct you — ever so gently — that this is a great time to get back on course.

A good amateur astrologer is like a good mechanic. You don’t want a mechanic that gives you a list of 65 things that are wrong with your car in no particular order and tells you that if you don’t fix them all (for one non-itemized flat-rate) you’ll end up crying in a ditch. You want a mechanic who can prioritize. Fix the breaks first. Worry about the missing stereo volume knob later. So, Scorpio, I have to let you know that while your future looks promising, there are a couple of major repairs you ought to take care of before you get back on the road. Luckily, you know just what they are. Give the big problems some attention this week. Leave the small stuff for another 10,000 miles.

All your summer gigs are booked. The plans are made. The flights are all reserved with window seats and everything. It’s hard to remember when it all started, but it all seems to be pushing forward with or without you. So what if, somewhere down deep, your gut says this isn’t the right time. This isn’t the season for the big tour. There isn’t really enough money and there isn’t really enough time and this wasn’t really the plan in the first place. Don’t be afraid to take a step back. You may find that your stomach is just churning with a mixture of excitement and uncertainty. Go with the flow and let the plans take you away. Or it may really be time to put on the brakes. Don’t be afraid to reconsider.

Do you remember Bandura’s Bobos? No, they weren’t the band you saw open for The Spin Doctors in ’91. You probably learned about them in your college psychology class. Allow me to refresh. There was this psychologist, Albert Bandura, and he did these experiments where he would take these three-foot-tall punching-bag clowndolls called “Bobos” and put them in rooms with kids to see if certain conditions would make the kids act aggressively toward the Bobos or be nice to them. It was all about how society makes us act violently or politely based on what we see or experience. You remember, right? But I was just thinking about how sometimes, Capricorn, you’re pretty hard on yourself. You tend to kind of beat yourself up. And I was thinking about those Bobo clown-dolls and how you can punch them and they bounce straight back. And I can see why you thought you could be so mean to yourself and expect to just pop right back into place. But you can’t. You need to take it easy on your inner-Bobo.

Man, Aquarius, it’s so hot out there you could fry an egg on the sidewalk! But despite the seeming convenience of cooking breakfast in the public right-of-way, there are probably better ways to fry an egg. Maybe a nice skillet on a stovetop would do the trick. Or go for one of those big flat commercial griddles. That way you could cook up a couple of strips of bacon and maybe some pancakes at the same time and you wouldn’t

have to worry about getting dirt or rocks or pieces of old gum in your breakfast like you do when you cook it on the sidewalk. Just a general reminder that while there may be a lot of ways to get the job done, using the right tools tends to yield a better result with fewer complications.

An ice tray full of warm water will freeze faster than one full of cold water. I learned this in a sixth grade from Ms. Linsey — a flustered student-teacher who was trying to demonstrate how to use the scientific method. The freezing phenomenon is called the Mpemba effect, named for the Tanzanian student who published his ice-tray research in 1969. The strange thing is that the phenomenon is contrary to the laws of thermodynamics. Nobody really knows why the warm water freezes faster. From Aristotle to Descartes to Mpemba to Ms. Linsey, everybody has theories. But nobody has figured it out. So, Pisces, remember that in this age of smartphones, satellites and nanotechnology, science still doesn’t understand what’s going on in your freezer. Why not ponder that over an ice-cold glass of lemonade.

In some traditions, fireworks are considered a good way of getting the attention of a god. They are a cry exploding into the heavens. “Look at me! Pay attention! I’m down here and I’m blowing stuff up!” It’s a bold move for a puny, finite being with a pack of Texas bottle-rockets. I can’t say whether it works or not, but I do like the idea that a good loud pop and a flash of sparkling light might get a second look from the divine. So, if you have the opportunity to set off some fireworks this month, I’d say go for it. But just in case somebody up there notices, maybe you should prepare a statement.

This month’s Taurus Hoboscope features vibrating bristles and a pivoting head that can rotate 360 degrees for maximum foretelling power! (If yours isn’t working, you probably broke it. Pick up another copy of this edition. It’s totally worth it!)

George Orwell is best known for his novels Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm, both of which explore the dangers of fascism and the inestimable importance of free speech. In a slightly less well-known work, Orwell took a bold stance on another danger facing Britain: that is, the epidemic of weak tea. In “A Nice Cup of Tea”, Orwell insisted “one strong cup of tea is better than 20 weak ones.” At a time when tea was in short supply, Orwell insisted that each cup should be brewed to the highest standard, even if that meant drinking tea less frequently. Consider this, Gemini, as you choose where to put your energy on a given day. There is only so much to go around. You’re better off putting enough of yourself into a few cups than trying to put a little bit into so many.

Mr. Mysterio is not a licensed astrologer, a trained nacho-cheese dispenser repairman, or a vigilantly-verified unnamed source. This set of Hoboscopes first ran in July 2013. Check out The Mr. Mysterio Podcast. Season 2 is now playing at mrmysterio.com

There are so many ways to get away from that ’ol repetitive cycle of doing the same things over and over. There are so many avenues and so many individuals that can help. Getting away is something you can pay for or you can receive it free.

I am going to touch on just a few. Looking at getting away from that ol' repetitive cycle of doing the same things over and over in many different styles and types of ways, but expecting different results. It should have you tired by now. We can keep up the hope that one day we'll overcome and come up with our own formula of how to beat the system. Or, we can learn from other information/ideas from individuals that have worked it out through their trial and error. See, to have a support group is a wonderful thing. If we work with a “we thing” instead of just a “me thing” things will be much better.

Consider giving yourself some true quality time: reading some deep novels while in a warm bubble bath or a love and fantasy novel by a warm cozy fireplace. Better yet, get a good full eight hours rest with no interruptions.

Let’s also look at going to another place to get around different people. No matter what it is, if you are doing the same things over and over you must expect the same results. To actually get away is to look deep into and analyze yourself deeply. Now what you come up with you might not end up enjoying, but that there is something that you will have to learn to accept. Once you accept it and you truly learn how to love yourself and learn how to enjoy things in life, then and only then will you be able to escape and come to the reality that getting away is an easy process.

So, stop doing what you have been doing and take in a deep breath of fresh air by giving yourself a break surrendering to a power greater than yours and sincerely following some suggestions from those that can love you unconditionally even though you might be a mess. Understand that you are like an onion and every layer that you peel off just might stink but as long as you keep surrendering, the smell will pass, and you'll start to observe freedom. So to get away, my suggestion is to surrender.

My sister Pam was a great person. Very well loved and liked. I hate it that she is not with us anymore. She had been battling with a blood infection called MRSA from shooting up heroin. She beat it twice, but this time it got her. She was 50 years old. She will be very, very missed.

I went to see her at the hospital on a Saturday and she was alert, but she did not know who I was or who her husband was. I went back and saw her the following Sunday afternoon, and she still did not know who I was and I knew it would not be long. She passed away soon after. I love her very much even though she was a drug addict. I’m gonna miss her. I

can’t believe she is gone.

This is such a huge shock to me. When they moved her out of ICU I was thinking maybe when I find her new room I’ll find out she will be OK again. She’ll know who I am. I was hoping she would come out of this infection, but it was so bad it spread to her brain. She got worse and there was no hope. It’s crazy because she was fine at the beginning of the month. At least she is not in anymore pain.

I love her and miss her a whole lot. She leaves behind four kids: Kayla, Heather, Rosa and Noah. And three grandbabies: Levi, Paisley Raye and Isabella. My heart hurts so bad. She will be missed a lot.

I have gained a lot of experience both in attracting customers and gaining more money each day and every week by being a Contributor vendor and entrepreneur.

One way of attracting my customers to buy my Contributor newspapers is by waving my hands at every driver that passes by so that they will be excited and buy the paper.

Another way to sell more papers is by selling in the same location and constantly moving back and forth along the line where I stand. By moving around, my customers know I am really working hard and they will be

more likely to stop and buy a paper from me. My smile is a big deal to my customers. Each time my customers drive by they see my smile as a real guy in business because to be a businessman is to create a loving environment that will attract customers easily. Last but not the least, as a Contributor vendor, my dress code need not to be too professional because customers will never view you as a working person in life. So my dress code is always less professional in comparison to my customers so that they can feel on top.