7 minute read

Special report

At the 2015 United Nations’ climate negotiations in Paris (COP21), countries across the globe pledged to keep global temperature rise below 1.5°C. But current policy is set to heat the planet by more than 3°C. To help close this gap between promises and reality, Article 6 of the Paris Agreement – the piece of legislation responsible for setting up the mechanisms for a worldwide carbon emissions trading system – was to be fi nalised at the end of last year in Madrid, at COP25. The aim of Article 6 is to create an emissions accounting system that is ‘so transparent that anyone can look at it and see what deals are being done,’ says Clare Shakya, Director of Climate Change Research at the International Institute for Environment and

Development (IIED). However, even after extra days of negotiations, COP25 fi nished with Article 6 unresolved.

Cost of indecision The negotiations ‘can get really complicated – there is a lot on the table, lots of issues and diff erent opinions,’ says Stefano de Clara, Director of International Policy at the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) and one of the authors of the carbon pricing report, The Economic Potential of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and Implementation Challenges.

The report found that international cooperation on decarbonisation could not only cut an additional 5bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent annually by 2030, but also deliver savings of US$250bn every year by 2030, increasing to almost a trillion in 2100. This could be reinvested in additional climate action. Every year that an emissions trading system is undecided, billions of dollars are potentially lost.

Sticking points The negotiations on these savings came to a halt as infl uential nations such as China, the US, India, Brazil and Australia drew impassable red lines. The three major stumbling blocks in negotiations were ‘double counting’, the transition of ‘old’ carbon emission reductions, and the inclusion of a mechanism to create an international fund for climate change mitigation and adaption.

‘Double counting’ is when governments count reduced emissions, but any private companies or agencies that may have assisted the government can also lay claim

What is Article 6 and why is it important?

Article 6 off ers a path to signifi cantly raising climate ambition or lowering costs, while engaging the private sector and spreading fi nance, technology and expertise into new areas, writes Lucy Woods

What is Article 6?

The Paris Agreement off ers three approaches to international cooperation mechanisms: Article 6.2 lets countries strike bilateral and voluntary agreements to trade carbon units Article 6.4 creates a centralised UN governance system for countries and the private sector to trade emissions reductions anywhere in the world. This system, known as the Sustainable Development Mechanism, replaces the Clean Development Mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol Article 6.8 develops a framework for cooperation between countries to reduce emissions outside market mechanisms, such as aid Paris Agreement: Special Report

to these same reduced emissions. Most parties believe private sector emission reductions should be included in a country’s emission count. ‘It is a philosophical diff erence,’ says Shakya. ‘We knew it would be a big issue.’

The second issue is whether or not to include ‘old’ emissions that were reduced under the Kyoto Protocol. The counterargument is that global emissions increase every year, so counting past reductions would skewer the fi nal count. The third debate, climate change mitigation and adaption funding, stalled as island nations, the EU and developing countries spoke with ‘one voice’ to include a funding mechanism, says Sandra Greiner, Lead Consultant at Climate Focus and one of the authors of the report Moving Towards Next Generation Carbon Markets, Observations from Article 6 Pilots. Opposing this are countries with regional programmes – such as the US and Canada – that are concerned it would ‘interfere’

with national tax regimes, explains Shakya. ‘It’s a major red line,’ adds Greiner.

Taking the lead These three issues are tabled for COP26 negotiations. ‘No deal is better than a bad deal,’ says Shakya, adding that ‘the worst thing would be to give countries a “get out of jail free” card.’ But without agreed negotiations, ‘what happens in the meantime, in the absence of rules?’ asks de Clara.

Some companies are making their own rules, ‘taking the lead in voluntary off setting’, as Greiner says. One example is UK airline EasyJet, which has partnered with Climate Focus to become the fi rst airline to announce that it is off setting all its carbon emissions. ‘EasyJet did that without Article 6,’ says Grenier. ‘You don’t have to wait.’ There are also the 31 nations – led by Costa Rica, and including the UK – that agreed on ‘the San Jose Principles’. These exclude ‘double counting’ and ‘old’ emissions, and have no adaptation funding

How do international carbon markets work?

Carbon markets provide an economic incentive for countries to reduce their carbon footprint

A country that struggles to meet its emissions reduction targets under its climate action plans (nationally determined contributions) can purchase carbon ‘credits’ from another nation that overachieved in reducing its own carbon footprint

mechanism. A lack of UN rules ‘does not prevent countries from improvising on their own,’ says de Clara. Nations can use the Principles and the Article 6 draft to trade until the COP26 meeting in Glasgow in December this year.

All eyes on the UK As host of COP26, and with the general election over, it is hoped that the UK government will rectify policy to stay within – or even exceed – the targets of its Climate Change Act (2008), setting an example for the global conference. The Act’s target is for the UK to be carbon neutral by 2050, although current emissions projections show the UK falling short. Success ‘will require the government to apply more challenging measures’, according to the Committee on Climate Change. Ambitions must be improved for COP26, says Shakya, with the UK ‘at the front of the pack’.

Capturing opportunities Hosting COP26 and meeting national zero-carbon targets will bring new opportunities to the UK, says de Clara. Innovative countries, and industries with digital trading platforms, robust accounting legislation and emissions measuring technology, will be needed to meet the carbon accounting needs of businesses. ‘If there is one thing that is wanted by all parties,’ says de Clara, ‘it’s integrity and good accounting.’

Technical issues in verifi cation and tracking were a major reason parties could not agree on Article 6. Unfortunately, ‘some countries do not have the technology to provide the necessary data – data that is needed to improve carbon trading,’ says Shakya. This leaves many parties unsure of the numbers around key issues – ‘no one knows about carbon numbers or volumes,’ as de Clara says. Companies that can provide data from blockchain, artifi cial intelligence, GPS satellites, advanced data platforms and satellites to monitor and verify emissions can all help to give parties ‘full confi dence’ in emissions accounting systems, and will ‘help make carbon trading understood,’ says Shakya.

There is also demand for verifi cation services to ensure that funding from countries such as the UK reaches local levels. In one of its studies, the IIED found that only US$1 in US$10 out of US$60bn in climate fi nance reaches those who need it.

These gaps mean there is ‘huge potential in transparency and tracking,’ says Shakya – an ‘opportunity to innovate’ with ‘lots of potential for UK companies to step in.’

If the rules are structured appropriately, both countries meet their climate commitments

Analysts say international emissions trading could almost double global emissions reductions between 2020 and 2035

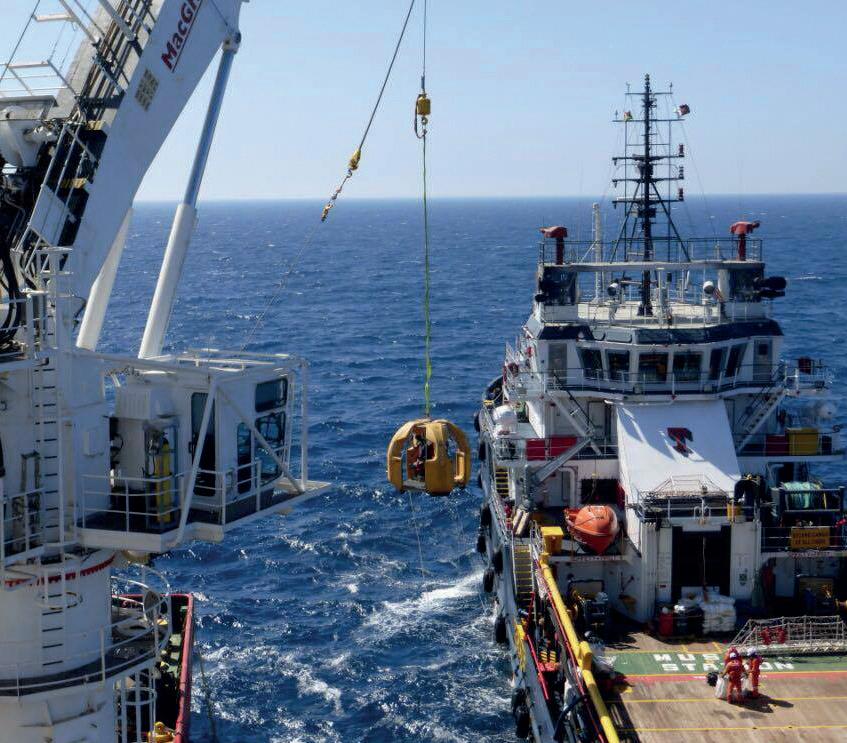

FROG-XT CREW TRANSFER