98 Foreword R. Briggs PAPERS & SHORT NOTES

99 Scottish Birds Records Committee report on rare birds in Scotland, 2022

C.J. McInerny & R.Y. McGowan on behalf of the Scottish Birds Records Committee

122 Hybridisation, courtship and possible breeding of mixed pairs of Black-throated and Great Northern Divers in Highland R.L. McMillan

127 A summering male Great Northern Diver successfully breeding with a Black-throated Diver in 2014 R.A. Broad

132 Great Northern Diver x Black-throated Diver hybrid in Argyll, 2023 D.C. Jardine & J.M. Dickson

137 BTO/SOC Scottish Birdwatchers’ Conference, Troon, 23 March 2024

144 NEWS AND NOTICES

152 OBITUARIES

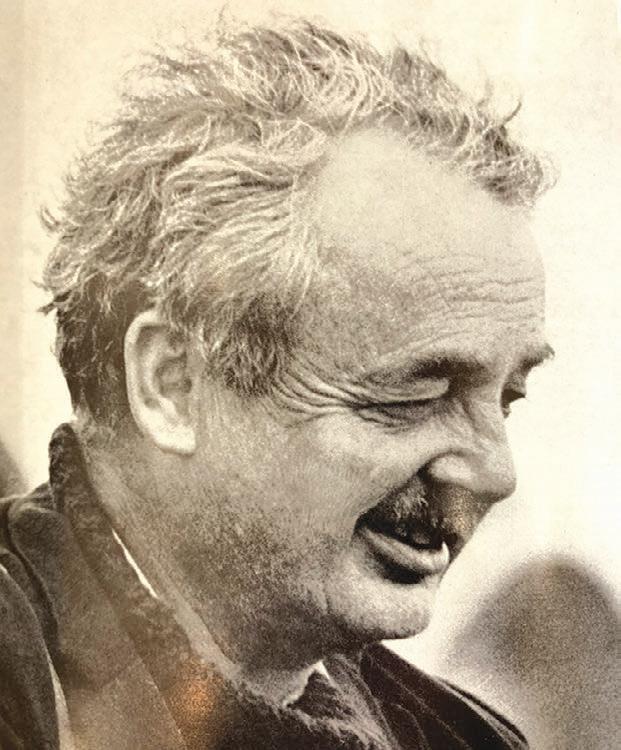

Geoffrey Horne (1936–2023) D. Thompson, with thanks to S. Hewitt & J. Miles

154 SOC brings Motus to Scotland: tracking Rock Pipits with new technology A. Knox, M. Martin, L. Mitchell & R. Wilbourn

157 Do female Pheasants have an acute sense of smell? J. Howie

158 Half a century on: Remembering Maury Meiklejohn (1913–1974) A. Barker

160 BOOK REVIEWS compiled by N. Picozzi

BIRDING ARTICLES & OBSERVATIONS

161 OBSERVATORIES' ROUNDUP

167 Fall of North American passerines on Barra, Outer Hebrides, September 2023 B. Taylor, K. Taylor & I. Ricketts

173 Blackburnian Warbler, Geosetter, 26 September 2023 - first Shetland record W. Carter

175 Stilt Sandpiper, October 2023 - second Outer Hebrides and first Dumfries & Galloway records G. Boner & I. Lang

179 Baltimore Oriole, 5 October to 4 November 2023 - first Fife record M. & R. Boyd

181 Pied Wheatear, Montrose, 20 October 2023 - first Angus & Dundee record S. Ritchie

183 Record numbers of Common Redpolls on the Isle of May in October 2023 K.D. Shaw & D. Steel

185 Western Olivaceous Warbler, Skibberhoull, Whalsay, Shetland, 20–21 October 2023 - first British record J-L. Irvine

188 Squacco Heron, Loch Smerclate, South Uist, 24–29 October - second Outer Hebrides record C. Timmins

190 Red-flanked Bluetail, St Peter’s Cemetery, Aberdeen, 31 October–3 November 2023 - third North-East Scotland record T. Unnsteinsson & D. Thomas

PHOTOSPOT

BC Purple Sandpiper J. Stevenson

(2024)

I make no apology for opening this issue of Scottish Birds with a huge and heartfelt ‘thank you’ to our Club Administrator, Wendy Hicks, who leaves her job with the SOC on 31 May 2024. As Wendy herself notes in our middle pages, she has worked with us for over 17 years and has both seen and led the Club through significant development and achievements during that time, always focusing on the wishes and needs of its members, branches, committees and partners.

Wendy’s energy, initiative, determination and passion for all that the Club represents is palpable. Behind the scenes, she’s worked tirelessly to meet deadlines, support me and other Presidents before me, advise other Council and committee members, lead and support staff, draft reports and organise events. In her piece later in this issue, she reflects on earlier days when headquarters were first becoming established at Waterston House. More recently, she has driven newer ways of working, including our popular online evening presentations for all members and a strong social media profile. She’s made sure that our Club-wide events programme, including the annual conference which she oversees, provides for younger ornithologists. In short, she has been our go-to and lead staff member to answer queries, resolve problems and make sure that things happen. Thank you Wendy, and good luck with your next move.

Thanks of a slightly different nature go to our Ayrshire Branch, hosts of this spring’s joint SOC/BTO conference in Troon and its next-day outings. We were challenged by speakers to think about the impacts of development on bird-rich sites, to understand flyways, to maintain long-term species monitoring on remote sites, to mitigate disturbance to feeding and resting migrants, to see the value of local projects not just in their own right but also in the context of national trends and ambitions - all through illustrated and entertaining descriptions of people, places and, of course, birds. Thanks to all involved in that March weekend.

Now read on. My privileged preview of the suite of papers about divers certainly whetted my appetite for the ornithological pages in this issue of Scottish Birds. And that was before I saw the front cover! Careful, recorded observations, attention to detail, historical research and a good understanding of the species themselves are evident both in this series of articles and in so many others. The SBRC has again collated for us its important annual record of Scotland’s rarities, receiving and ratifying reports from observers and Local Bird Recorders around the country. I personally find the notes about discernable trends in individual species of particular interest.

There is, as ever, much more. I hope you enjoy this issue of Scottish Birds

Ruth Briggs, SOC PresidentThis is the 15th annual report of the Scottish Birds Records Committee (SBRC) describing rare birds recorded in Scotland during 2022. Previous annual reports that cover the period 2005 to 2021 can be found in preceding issues of Scottish Birds or downloaded at www.thesoc.org.uk/bird-recording/sbrc-species-analysis, some of which are cited in this report.

A summary of the rare bird species considered by SBRC, the SBRC List, and other committees is given in Appendix 2, and is shown at www.the-soc.org.uk/bird-recording/sbrc-list-past-lists

Recent changes to the SBRC List include, from March 2022, Scottish Crossbill Loxia scotica removed from the List (Lewis & McInerny 2022a, 2022b; www.the-soc.org.uk/content/birdrecording/sbrc/identification-of-scottish-and-parrot-crossbills). Furthermore, from January 2023, SBRC will consider records of Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina, Little Owl Athene noctua, European Bee-eater Merops apiaster and Marsh Tit Poecile palustris, with local dispensation for recording areas Dumfries & Galloway and Borders for Little Owl, and Borders for Marsh Tit (Lewis et al. 2023). Additionally, Great Shearwater is dropped as an SBRC species from 1 January 2024. For a summary of these changes see Appendix 2 and www.the-soc.org.uk/bird-recording/sbrc-list-past-lists

The distribution and number of most rare birds reported in Scotland during 2022 were similar to other years. However, the most striking change was the increase in numbers of Cetti’s Warblers Cettia cetti, with eight seen across mainland Scotland, almost double the previous total count of five records. Significant numbers of Arctic Warblers Phylloscopus borealis (18) and Red-flanked Bluetails Tarsiger cyanurus (13) were recorded. Exceptionally large numbers of Great Shearwaters Ardenna gravis (142) and Cory’s Shearwaters Calonectris borealis (29) were observed, following recent trends. One recording area, Borders, did especially well for rare birds in 2022, including four new species (Jackson 2023). In contrast, a number of SBRC species were not seen in Scotland during 2022 including Alpine Swift Tachymarptis melba and Night-heron Nycticorax nycticorax.

The species accounts in the report follow a standard format. Nomenclature and taxonomic sequence follow the latest version of the Scottish List, which follows the 10th Edition of the British List and subsequent changes adopted by the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU 2022, 2024; www.the-soc.org.uk/bird-recording/the-scottish-list).

On the header line, after the species or subspecies name, are three numbers: n Total number of birds in Scotland to the end of 2004, based on Forrester et al. (2007) with adjustments in a few cases, and also including records added in this report. In some cases, older records, ‘At Sea’ records, or records pertaining to the breeding population were excluded from the totals, following the example of Forrester et al. (2007). However, to align with other publications, we have decided to include At Sea records in species totals in this report for the

Mixed pairs of Black-throated and Great Northern Divers in Highland

This paper provides background to the hybridisation and possible breeding of mixed pairs of Blackthroated and Great Northern Divers in the Highland recording area in the last 50+ years.

Introduction

The starting point is an interesting discussion on the possible breeding of Great Northern Divers Gavia immer in Wester Ross in 1970 (Forrester et al. 2007). On the same loch, in the following year, there was a pairing of a Great Northern Diver x Black-throated Diver Gavia arctica hybrid with a Black-throated Diver which produced a chick (Hunter & Dennis 1972). It is emphasised that the Great Northern Diver x Black-throated Diver hybrid looked very similar in size to a Great Northern Diver, but also confirms that hybridisation took place at some time previously. As birds tend to return to their natal lochs (R.H. Dennis pers. comm.), the hybridisation is likely to have taken place in north-west Highland (Forrester et al. 2007). However, these well documented observations cast doubt on the 1970 record of a pair of Great Northern Divers breeding in Wester Ross as above. There is therefore no confirmed breeding of Great Northern Divers in the United Kingdom (Eaton et al. 2023). Given that the 1971 record was not a mixed pair, and though previous hybridisation was suspected, at the time there was no confirmed record of such pairings breeding in Scotland.

In 1985, a mixed pair of Black-throated and Great Northern Divers was present at an inland Highland loch from 8 May to early June, but there was no evidence of breeding. At the same loch in 1986, a male Black-throated Diver mated with a female Great Northern Diver and nested. The first clutch was flooded out. The female re-laid a single egg which hatched a chick which later disappeared. This appears to be the first confirmed breeding of a mixed pair in Scotland. (Spencer et al. 1988 and E. Maclean, pers. comm.). It is worth noting that there is no mention of this record in The Birds of Scotland (Forrester et al. 2007).

Elsewhere, a mixed pair of a female Black-throated and a male Great Northern Diver was observed on Bear Island, Svalbard, which apparently laid a single egg, though the nest was predated (Lovenskiold 1964). A study of Gaviiformes (Roselaar et al. 2005), concluded that there was evidence of hybridisation in four of the five species, though in regard to G. arctica and G. immer it was extremely rare. Further examples of mixed pairs are provided in McCarthy (2006).

Sources

The main source of information in Highland is the annual Highland Bird Report (HBR) published by the Highland Branch of the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club (Joss 2002–22). The Rare Breeding Birds Panel (RBBP) archive also makes reference to several records of mixed pairs in Highland recording area from 1986 to 2017 and some of these reports reflect what is published in HBR. However, data can be sent direct to the RBBP and may therefore by-pass the recorder and not be included in the HBR. The opposite can also apply, so the dataset may be fragmented. The

Great Northern Diver successfully breeding with a Black-throated Diver in 2014

An adult Great Northern Diver reported in 2000 was relocated at a nearby undisclosed site south of the Great Glen in summer 2001. It returned to this same loch in most years to 2023 where it associated closely with Black-throated Divers. Breeding was confirmed in 2014, when a chick was raised by a male Great Northern x female Black-throated Diver.

Introduction

The principal loch in this account is one of several scattered, traditional breeding sites for Blackthroated Divers Gavia arctica (hereafter Black-throats) in Highland, to the south of the main strongholds in north and west Highland. Several of these were visited annually to monitor the breeding success of Black-throats, ideally with early visits to check occupancy (May–early June) and late season visits (July–early Aug) to record any successful breeding attempts (Broad 2018). On 21 July 2001, an adult Great Northern Diver Gavia immer (hereafter Great Northern) was found fishing alone. Later, after recounting this to the head keeper, who was very familiar with Blackthroats, he described what must have been the same bird. He had watched it on several occasions in 2000, when it was often accompanied by a Black-throat at a nearby loch with no previous history of breeding Black-throats, but where they were regularly found fishing.

Observations of a Great Northern 2000–23

Neither site was monitored in 2002, but in 2003 and 2004 a Great Northern was again found in July at the loch where it had been found in 2001. On both occasions, a Black-throat was swimming within 100 metres, but without any obvious interaction. Whenever possible in subsequent years, additional early visits were made in April–June. During this period, the loch has regularly held a pair of Black-throats and often one or two additional birds have been present. Monitoring was difficult, as the loch could not be adequately viewed from a single viewpoint. In some years, the Great Northern was easily found, but in others it was elusive, giving only occasional, brief views and in two it was not seen at all. In years when it could not be found at the favoured loch, the nearest adjacent Black-throat lochs were also visited without success. During 2000–23, the loch was monitored in 22 years and an adult Great Northern was seen or reported by others in 20 of these, with records between 10 April–5 August. On two occasions, reports of two Great Northerns were received, but neither could be corroborated on follow-up visits. In general, divers are known for their strong site fidelity and there seems little doubt it was the same individual seen in full breeding plumage that returned to the area repeatedly over a period of 24 years.

Divers are also known for their strong pair-bond that endures over years and Great Northerns are described as serially monogamous in North America where territory occupation is maximal (Evers et al. 2020). However, in this account, the Great Northern’s relationship with Black-throats that were almost invariably present nearby could often only be surmised. It was frequently encountered fishing or loafing on its own and, though one or more Black-throats were often visible 100 or more metres away, there was little or no obvious interaction. On other occasions, the Great Northern was seen interacting with a Black-throat, with much close circling and bill dipping, but it was rarely clear whether these were defensive territorial or courtship encounters,

A hybrid Great Northern Diver x Black-throated Diver was photographed in Argyll in late May 2023. This paper describes its plumage and compares this with published photographs of both species from Britain, Ireland and Iceland, and a previous report of a hybrid between these species in Scotland.

Introduction

On 26–28 May 2023, Gareth Thomas visited a loch in Argyll where he saw and photographed what he thought was a mixed pair comprising a Black-throated Diver Gavia arctica and Great Northern Diver Gavia immer (Plate 86), copies of which he sent to the local recorder (JMD). However, when reviewed by DCJ and JMD the photographs revealed that the plumage of the Great Northern Diver did not match the normal summer plumage of this species; the bird was in fact a hybrid G. immer x G. arctica (Great Northern Diver x Black-throated Diver). Neither bird was present when the site was revisited on 3 June (R.A. Broad pers. comm.). The Black-throated Diver was sexed as a ‘probable’ male on head-shape (Lehtonen 1988, Lehtonen & Lappalainen 2017); by inference, the hybrid, which was in its company for three days, was probably a female.

On first inspection, the hybrid was very similar to a summer plumaged Great Norther Diver. It was slightly larger than the Black-throated Diver, had a heavier bill and the steep forehead characteristic of a Great Northern Diver (Plate 86). Five plumage differences were noted.

The hybrid shows a slight downward central v-pattern in the demarcation between the white breast and the black neck/throat (Plate 87b). This feature is found in Black-throated Diver (Plate 89), while absent in Great Northern Diver (Plate 88b).

The wind was blowing strongly off the sea, with the sun shining and flocks of waders feeding on the strandline, as almost 200 like-minded people joined the SOC and BTO Scotland for this year’s spring event, ably hosted at the beautiful Troon Concert & Walker Halls by the SOC’s Ayrshire Branch. We were welcomed to the conference by SOC President Ruth Briggs, with inspired title slides provided, as always, by Lothian SOC member Stephen Hunter. We are grateful to the speakers for providing a summary of their respective talks for this article.

Lynne Bates, Coordinator, Irvine to Girvan Nectar Network, Scottish Wildlife Trust Nectar networks and Sand Martin houses As part of SWT’s Irvine to Girvan Nectar Network, Lynne discussed her work in helping to establish connected nectar and pollen-rich sites along the Ayrshire coast, ensuring the long-term survival of pollinating insects in the area. She discussed some of the projects undertaken in the last two years with the various partners involved, ranging from transforming Council-owned amenity grassland areas into low maintenance, highly

A new SOC project is taking migration studies in Scotland to another level. One hundred and fifteen years ago, the first properly organised bird ringing in Britain began in Aberdeen. Ringing allowed us to understand far more about bird movements and other aspects of avian biology. More recently, the day-to-day (or minute-tominute) lives of individual birds have been followed using a variety of sophisticated tracking technologies. These have been tailored to the requirements of specific projects, but have often been limited to larger species because of the weight or configuration of the devices.

However, the Motus Wildlife Tracking System (https://motus.org/) is changing this. Motus tags weigh as little as 0.2 g, and as a result, they can be safely fitted to our smallest birds, bats and even larger insects such as dragonflies. They send out signals at a pre-programmed rate which can be as often as every second. These are picked up if a tagged bird passes within about 10 km of a receiver at a base station with directional antennae.

Although tags can be detected by just one receiver giving information at a local scale, more stations are needed to track wider movements. An expanding network of Motus receivers has been built along the south and east coasts of the UK and on the European continent. The first receiver was recently installed on the Isle of Man, where the team will tag juvenile Wheatears at the Calf.

The initial results from Motus in Europe have been exciting, including one Yellow-browed Warbler Phylloscopus inornatus tracked from Ottenby in Sweden via four different receivers around the German Bight before it disappeared inland in the Netherlands (https://twitter.com/ OttenbyBO/status/1715437381149479033), and another tagged in the Netherlands on 8 October last year which pinged the Dungeness, Kent, receiver between 01:00 and 02:00 12 days later. The first tagging project in the UK focused on Blackcaps Sylvia atricapilla and two of these have been detected travelling in an easterly direction through Germany, where the signal is often lost due to a lack of receivers.

So far there are no receivers in Britain north of Yorkshire, where one was installed at Bempton in 2023. This is now changing, thanks to an exciting new SOC project. In April 2022, the North-East Scotland branch hosted a Zoom talk on Motus by Dr Lucy Mitchell, Chair of the UK Motus Steering Group and then at the University

A few years ago, I planted some newly-bought crocus corms and a few weeks later I kept finding the soil disturbed where they had been planted and the damaged underground stalks lying on the surface of the soil with no sign of the corms. Eventually, I managed to see the culprits in action and, to my surprise, they were female Pheasants.

Attempting to save the remaining corms, I tried putting gravel then small stones on the soil above the corms, but to no avail. I concluded that the birds must have been able to smell the corms, so I then put anything which might mask any smell over the remaining corms: lemon, orange, and grapefruit peel, then coffee grounds, pepper, lime, ‘Growmore’ and bone meal - nothing worked! And, of course, I chased the birds away any time I saw them.

Since corms which had been in the soil for years were not attacked, did this mean that the new corms had a distinctive smell? Or had the corms been treated with some chemical, which told the birds that something edible was under the soil? Whatever the reason, I can only conclude that female Pheasants must have a really acute sense of smell to detect anything they fancied at a depth of 10 cm/4 inches (which was the length of the underground stalks the birds dug up). Although there was also a male in the garden, I never saw him joining in the destruction of my precious crocus corms!

Has any other SOC member had the same or a similar problem with Pheasants?

Joan Howie, New Galloway

During Dr Alan Knox’s presentation of material from the Club’s archive of sound recordings at the 2023 SOC conference in Pitlochry, delegates were once again entertained (and possibly baffled) by the unique tones of the extraordinary Matthew Fontaine Maury Meiklejohn, who died 50 years ago on 14 May 1974. Not to be confused with his heroic namesake, the one-armed Gordon Highlander Major Matthew F. M. Meiklejohn V.C., Maury was SOC president (1960–1963), founder editor of Scottish Birds (1958–1961), and an inaugural member of the British Birds Rarities Committee (the ‘ten rare men’). He was even credited by some with the notion of birders keeping a ‘life list’. The multiple accomplishments of Glasgow University’s polyglot Professor of Italian and the Glasgow Herald’s prolific columnist (byeline M.F.M.M.) are evoked in a masterly tribute by another SOC legend, the fellow-artist and writer Donald Watson (1918–2005). This can be found online in the Obituaries section of the SOC website: www.the-soc.org.uk/about-us/clubhistory/obituaries

Maury’s ashes were scattered on his favourite Isle of May, whose every rock he claimed to know ‘except those that are precipitous’, and to whose observatory logbook he was a tireless contributor. He continued in the same vein on his visits to Fair Isle, where he instituted the Meiklejohn Prize for the fewest birds seen in a day. As was his wont, on an unpromising day for eastern rarities, he would break into verse:

There was an old man on the May Who knelt down on the North Ness to pray: ‘O Lord I have sinnedBut why need the wind Blow westerly day after day?’

It was to one such disappointing day, 20 September 1949, that we owe the first scientific description of the Hoodwink (Dissimulatrix spuria), a species ‘polymorphic but usually unbridled’, the male of which ‘flies in ever decreasing circles, evoking no response whatsoever from the female’. When writing up his observation in the RSPB’s Bird Notes (1950), Meiklejohn noted how birders best recognise the species by its ‘blurred appearance and extremely rapid flight away from the observer’.

Citing McSporran, Meiklejohn also reports that ‘haggises are the pellets of the Hoodwink’. Not everyone was charmed by Maury’s lighthearted, occasionally risqué (for 1950) prank. The eminent American ornithologist H.G. Geignan (1951) grumbled that ‘one could wish that articles of this nature be omitted from the pages of serious journals’. Not so po-faced, Rachel Warren-Chadd and Marianne Taylor (2016) concluded that the Hoodwink was imagined as a ‘representation of all birds that cannot be properly identified by the birdwatcher’. But they also call it the Barefronted Hoodwink, which it isn’t! According to Bob McGowan, formerly Senior Curator of Vertebrates at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, most on-line descriptions and images of ‘Hoodwink’ refer to the Bare-fronted

Observatories’ Roundup is a regular bi-annual feature about our bird observatories in Scotland. The intention is to publicise the work of the observatories, visiting opportunities, as well as incidental snippets of news from the islands.

A productive late autumn was had on Fair Isle last year, as an exciting spell of birding from the middle of September saw two Arctic Warblers on 15th and 17th, a Red-flanked Bluetail skulking in the dark recesses of Troila Geo, and a rather scruffy Lanceolated Warbler trapped at Quoy - the 100th record of this iconic Fair Isle species. A Rustic Bunting at the Airstrip was swiftly followed by a stunning adult male Redtailed Shrike the next day, which showed well to a very appreciative crowd, and went on to linger around the south of the isle for three weeks. A second Lanceolated Warbler was found at Setter on 24th, showing extremely well as it scurried along the dry stone walls, and a Cattle Egret flew past South Light the next day - the first isle record of this expected, but nonetheless exciting, addition to the Fair Isle list. A smart juvenile American Golden Plover and a Radde’s Warbler were further quality additions to the year list in the last week of September, along with a flighty Richard’s Pipit on Meoness - a difficult species to see in recent years, as records have dropped away quickly.

One of the highlights of the year for many was the concentration of cetaceans that spent several days feeding off the south and east of the isle at the end of September, with a huge Humpback Whale sharing the sea with up to 30 Minke Whales and 50 White-beaked Dolphinsan incredible spectacle to see in UK waters.

Sadly, the early October birding struggled to match the cetaceans for excitement, though a large arrival of birds on 9th saw impressive totals of 255 Goldcrest and 18 Short-eared Owls, alongside a sizeable arrival of thrushes. Rarities were headed up by a female Amur (Stejneger’s) Stonechat that showed well in Boini Mire, and two confiding Olive-backed Pipits at Utra. Another rather quiet spell followed, with a handful of Waxwings the

(2024)

highlight, until the Coal Tit irruption occurring throughout Europe finally reached the isle, with an amazing 14 of these striking continental birds scattered along the SW cliffs, many actively feeding in small vocal groups. Joining them were a cliff-dwelling Blackbellied Dipper, a ‘Northern’ Treecreeper and a Bewick’s Swan, the latter looking very out-ofplace taking shelter at the base of Helli Stack. A stunning Pallas’s Warbler at Setter on 24th was a very welcome sight, accompanied that day by a large arrival of Goldcrests, with birds in every sheltered section of the cliffs. A striking Coues's Arctic Redpoll amongst good numbers of Mealy Redpoll, a growing flock of ‘Northern’ Bullfinches around Boini Mire and a late Olive-backed Pipit were the highlights of the latter part of October, and the final week of what has been another excellent season, before the team left the isle for the year on 31 October.

After a wild and windy winter that saw major damage to several of the Heligoland traps, spring got underway early with some southeasterly winds delivering the isle’s earliest ever Chiffchaff on 7 March, a good ten days before the migration of the seasonal staff back to the island. The expected early spring arrivals followed, punctuated by a Woodlark on 21st

Bruce Taylor relates the events of this extraordinary autumn.

Over recent years, the isle of Barra has amassed an enviable list of rare North American vagrants, but it’s important to point out that we go through long dry periods without any rarities: indeed, a whole year may go by without any Yanks. Nevertheless, we live in hope. We watch the weather, pay attention to the jetstream position and hurricane activity and flog our patch daily, just in case. We had long harboured the hope that one day the island might host multiple American vagrants at the same time; we can all dream, after all. However, the events that unfolded in late September 2023 were way beyond our wildest fantasies.

A promising-looking weather system, the remnants of Hurricane Lee, swept up the

eastern seaboard of North America before speeding across the Atlantic, hitting Britain and Ireland around 20 September. News kept breaking of rare Yanks being found to the south of us; it became clear that the storm had delivered an incredible number of American birds to Wales and Ireland. Meanwhile, Barra was virtually unbirdable with heavy rain and a westerly gale relentlessly battering the island.

Kathy and I were out birding from first light on the 21st, eager to see what birds had appeared with the storm. The first few hours were wet and largely bird-free but things were about to get a whole lot better. We arrived at Eoligarry Church around mid-morning, just as the rain finally stopped. Behind the church is a small clump of

Our late autumn week on the Isle of May was scheduled to start on the 21 October 2023. However, it had been a stormy autumn and we did not get across until the 23rd. The crewMike Martin (lead), Eleanor Martin, Kevin Harris, Derek Robertson, Chris Broome and KDS - was assembled to carry out a full ringing programme while ‘covering the ground’, counting all species, and where possible and appropriate, photographing them.

Meanwhile, on the night of 22/23 October, the Firth of Forth was swept by east winds originating from the southern part of the Baltic states. When we arrived we noted there was a small arrival of birds on the May; 400 Redwings, 150 Song Thrushes, and 40 Robins. Amongst the birds logged that night was a single Common ‘Mealy’ Redpoll. Through the next night Derek Robertson went out and, using his thermal

(2024)

camera, noted six Jack Snipe close to the Low Light. We prepared ourselves for a bigger arrival on the morning of 24 October. We were right to do so! Basically, all species had increased in numbers and there were new arrivals, including singles of Firecrest, Hawfinch, and Waxwing, and two Ring Ouzels. We realised that there had been a large increase in Common Redpolls and we put 55 in the log that night. The next night - of the 24/25 October - was a wild night with the strong wind moving from north to northeast and finally east. The next morning there were more arrivals including four ‘Northern’ Bullfinches, 26 Bramblings and we logged Common Redpoll at 70! If anything, this was an underestimate, as Redpolls are difficult to count with lots of small, mobile, interchangeable flocks. The next night - of the 25/26 Octoberthe strong wind was basically east. As the weather was set to deteriorate further, four of

On the 20 October 2023, I was birding on my home island of Whalsay, Shetland - it was day three of a good period of fresh to strong SE winds with a decent scatter of common migrants. A ‘Northern’ Treecreeper and three ‘Continental’ Coal Tits on the 19th added a bit of quality to the many Goldcrests, Robins and Blackbirds etc.

The morning of the 20th was fairly quiet, with lesser numbers of birds at the north of the island and nothing new in, except for a single Reed Bunting at Skaw. In the afternoon, a look around the south turned up a Little Bunting on a small rig at Sandwick, so I decided to try my luck among the small tree plantations at Skibberhoull. When exiting one of the small, but dense, plantations known locally as

(2024)

Plate 158. On the morning of 24 February 2024, I was sitting amidst large rocks close to the water’s edge looking to get shots of birds flying by. The light was good, however, passing birds were keeping a distance from the shoreline. Patience was rewarded when a single Purple Sandpiper suddenly flew in directly towards me to land on the shore. At the last moment it must have become aware of my presence and swung to the left allowing me to take a few shots as it flew by.

John Stevenson, Houston, Renfrewshire. Email: ziggysteve777@gmail.com

Equipment used: Canon R7 camera, Canon EF 400mm F5.6L lens + EF1.4x III Extender, Manual, 1/1250 second, ISO 400, f9.0.

Featuring the best images posted on the SOC website each quarter, PhotoSpot will present stunning portraits as well as record shots of something interesting, accompanied by the story behind the photograph and the equipment used. Upload your photos now - it’s open to all.