290 Foreword R.F. Briggs

291 Breeding waterfowl population trends in Scotland’s eastern Flow Country over 22 years R.D. Hughes, M.H. Hancock, D. Klein & P. Stagg

298 Oystercatchers in the breeding season and stock husbandry in the central Highlands of Scotland N.E. Buxton

308 Observations of nesting and foraging behaviour of Yellow Wagtails in East Lothian K. Ingleby & M. Holling

312 Nightjar in North-East Scotland: a species at the edge of its range A.G. Knox

329 Long-tailed Tits foraging on a beach S.R.D. da Prato

329 Storm impacts to sea duck habitats, outer Dornoch Firth - Moray Firth D. Patterson & D. MacAskill

333 Is ‘hinge-mounding’ for tree planting a hazard for ground-nesting birds? R. Summers & D. Thompson

338 NEWS AND NOTICES

343 SOC at the Biodiversity exhibition in the Scottish Parliament M. Holling & C. Tansey

344 The South of Scotland Golden Eagle Project faces closure - a public appeal C. Barlow

345 Waterston House pond families R. Filipiak

348 OBITUARIES

John Skilling (1935–2024) B. Smith

Alistair James McWilliam Smith (1928–2024) E. Dunn

351 BOOK REVIEWS compiled by N. Picozzi

BIRDING ARTICLES & OBSERVATIONS

354 OBSERVATORIES' ROUNDUP

362 SCOTTISH BIRDS RECORDS COMMITTEE (SBRC) QUARTERLY BULLETIN D. Steel

365 Pallid Swifts at Dunbar, Yellowcraig and Port Seton, October 2022 - first Lothian records I.J. Andrews

367 Pacific Diver, Colgrave Sound, off Brough, Fetlar, 19 May 2023 - second Shetland record B. Thomason

371 Brünnich’s Guillemot, Scrabster, 20–22 June 2024 - third Caithness record R-A. Leak

373 Lesser Yellowlegs, St Andrews, 24 July to 2 August 2024 - second Fife record T. Beckett

376 Sabine’s Gull, Invergowrie, 8 August 2024 - first Perth & Kinross record M. Wilkinson

378 American Cliff Swallow, St Kilda, Outer Hebrides, 11–12 August 2024 - second Scottish record C. Nisbet & T. Wallis

381 Index to Volume 44 (2024)

BC Barn Owl F. Gibbons

(2024)

The Flow Country. How fortunate we are in Scotland to host such an internationally important area of wild land. Dominated by peatland recognised for its extreme importance as a carbon store, it is a majestic, extensive landscape subtly supporting a wealth of plant and animal speciesnot least some 30 species of Sphagnum moss!

Much of the Flow Country’s 4,000 square kilometres (over 1,500 square miles) is covered by international and national conservation designations for blanket bog and its associated wetlands and species, including birds. Celebrations were held this year as nearly half (1,900 square kilometres - 730 square miles) was classified by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, the only one in UK recognised purely for its natural attributes. There are 39 Sites of Special Scientific Interest and Special Area of Conservation, Special Protection Area (SPA) and Ramsar designations. A large RSPB National Nature Reserve, a Plantlife nature reserve and the Flow Country Partnership all aim to protect, restore and enrich the peatland ecosystem.

Change, as everywhere, is a constant for the Flow Country. It certainly has a chequered history. 9,000 years of peat development includes centuries of benign human association and late twentieth century damage (through misplaced afforestation policy). Climate and potential development pressures continue.

So, here’s my point! This issue of Scottish Birds includes a key paper by four authors, including SOC members, reporting 22 years of breeding data for five Flow Country birds. That’s a lot of survey effort! I find the article thought-provoking, particularly because of the variations it describes between the numbers of birds from one set of years to another within the 22-year period. Some trends do emerge but, as the authors say, their work is yet another illustration of the importance of long-term data collection to better inform our understanding of species’ needs and to determine priorities for site management and protection.

Within the SOC, we have many other examples of members participating in long-term studies which are contributing to conservation and, hopefully, more sustainable development planning. I think of members’ work in Orkney on breeding Arctic and Great Skuas and how this contributes to our wider understanding of avian influenza. In a very different scenario, members are sharing their longstanding experience of birds using parts of the Firth of Forth SPA to contribute data towards decision-making about proposed coastal protection measures. Wind farms and their associated structures, recreational activities and urban expansion are other areas where baseline and continuing studies of birds, often by volunteers, have a key role in seeking to achieve sustainability.

Whatever your main area of involvement with birds and the SOC, I hope you find interest and ideas in this issue. The conference and AGM season is ending and, outdoors, winter birds can now capture our attention.

Ruth Briggs, SOC President

Over 22 years, waterfowl surveys were conducted in the Flow Country of northern Scotland, to monitor population trends, revealing increases in Mallards, Wigeons and Tufted Ducks and stable Teal numbers, contrasting with national trends. Greylag Goose numbers were erratic. Potential factors influencing these trends include afforestation, predator dynamics and habitat restoration efforts. This study emphasises the importance of long-term monitoring to understand ecosystem dynamics. Further investigations into breeding productivity and ecosystem health are warranted, to ensure effective management strategies and the preservation of waterfowl populations in the face of ongoing environmental challenges.

Introduction

Waterfowl can be valuable bioindicators of aquatic ecosystems (Amat & Green 2009). In the UK, 12 of the 15 duck species with sufficient population data to monitor changes have shown a declining 10-year trend in breeding numbers between 2010/11 and 2020/21 (Austin et al. 2023). Waterfowl species in the UK face multiple, likely interacting pressures throughout their annual and life cycles. A key pressure on populations is climate change, which can influence migration strategies, distances, and phenology, potentially affecting survival, as well as distribution and reproductive success (summarised by Guillemain et al. 2013). It is not possible to produce breeding trends for all waterfowl species at a UK or Scottish level for various reasons, including the small (often hard to access) populations of species such as Common Scoter Melanitta nigra and Wigeon Mareca penelope. Some species require more targeted data collection, collation of data or monitoring, e.g. through the Rare Breeding Bird Panel (RBBP) or species-specific surveys (Underhill et al. 1998; Miles et al. 2021).

In the Flow Country of northern Scotland, detailed monitoring of the Common Scoter population began in the 1980s (Fox et al. 1989; Hancock 1991). There was a national survey in 1995 led by the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT) and another round of surveying in 1996. Monitoring resumed in 2002, following the establishment of Forsinard Flows National Nature Reserve (NNR), and has continued annually until the present, both on the reserve and neighbouring areas. From 2002 to 2023, while the data were still primarily collected for Common Scoter monitoring (Hughes et al. 2024), all other waterfowl species present were recorded, with numbers, sex, pairs, and brood size data. This forms the basis for this work, where we investigate population trends for the commoner species of other breeding waterfowl. This includes counts for Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula, Wigeon, Mallard Anas platyrhynchos, Teal Anas crecca, and Greylag Goose Anser anser in the study area, allowing us to investigate how these have changed over time.

The Flow Country of northern Scotland is a 4,000 km2 peatland landscape, holding Europe’s largest blanket bog and thousands of nutrient-poor pools and lakes, ranging from a few m2 to many km2 (Stroud et al. 1987; Lindsay et al. 1988; Hancock et al. 2016, Robson et al. 2023). Approximately 1,300 km2 of the area is protected under the European Birds and Habitats Directives (Council

Observations of nesting and foraging behaviour of Yellow Wagtails in East Lothian

K. INGLEBY & M. HOLLING

Yellow Wagtail Motacilla flava are scarce breeding birds in Scotland being at the northern edge of their range and, in the south-east of the country, are mostly confined to arable farmland in East Lothian and the lower Tweed and Teviot valleys. Although populations are generally in decline across the UK (Balmer et al. 2013), those along the East Lothian coast appear to be stable or indeed increasing with an estimate of between ten and 15 breeding pairs between Dunbar and Thorntonloch (Murray et al. 2019). More recently, fieldwork by MH identified territories near Dunbar around Eweford, the River Tyne near Tyninghame and east of North Berwick between Tantallon and Auldhame.

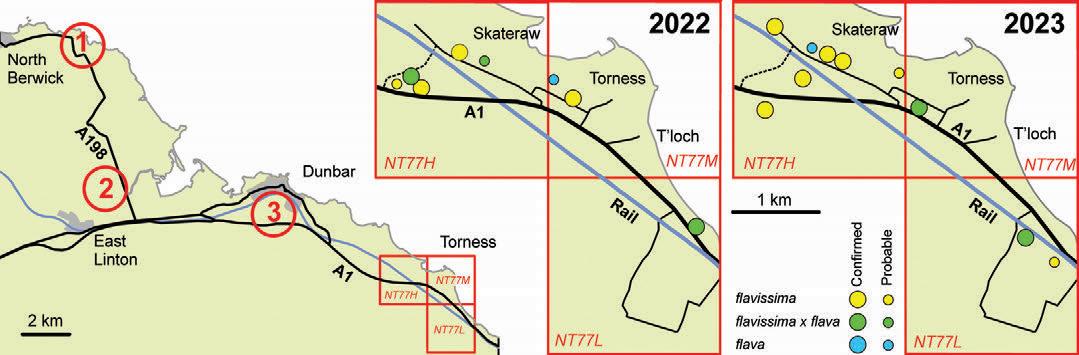

In 2022 and 2023, KI undertook an intensive study of breeding birds within the three tetrads that surround Thorntonloch: NT77H (Skateraw), NT77M (Torness) and NT77L (Lawfield). All areas in the tetrads were visited at least once, with repeat visits made if a bird was present. Birds first appeared from late April into May and, as territories were established during May, male birds would readily investigate any intruders, providing close views and photographic opportunities. Using the criteria established by Andrews & Gillies (2016), male birds were tentatively separated into the British race flavissima or the continental Blue-headed race flava, or hybrids of the two, now commonly referred to as ‘Channel Wagtails’ (Andrews & Gillies 2016). No attempt was made to assign females to a subspecies. Further visits provided corroboration of territories, with repeat sightings of the same male bird, presence of female birds, courtship flights and carrying of nest material, enabling the identification of probable nesting sites within fields. Confirmation of breeding was made at these sites when observations of food carrying or the presence of recently fledged birds were observed.

Results

In 2022, eight nest sites were identified, five with confirmed breeding (Figure 1). Food-carrying was first observed on 11 June and fledged birds were first observed on 7 July. In 2023, ten nest sites were identified, seven with confirmed breeding. Food-carrying was first observed on 10 June and fledged birds were first observed on 7 July. In both years, confirmed breeding was obtained for all three tetrads.

Figure 1. Nesting sites of Yellow Wagtails found in three tetrads (NT77H, NT77M, NT77L) around Thorntonloch and Torness Power Station during 2022 and 2023. Numbered sites 1–3 refer to other areas where breeding has been recorded (see text).

(2024)

A.G. KNOX

Within Scotland, the Nightjar regularly breeds only in the south-west. It became functionally extinct across most of the rest of the country about the time of the Second World War and was last reported nesting in North-East Scotland1 in 1979 and 1944. In this paper, the historical distribution and collapse in records of Nightjar is described in detail at county level for the first time, and the results of a new 11-year study are reported. In contrast to a previous scarcity of records, Nightjars were discovered in potential breeding habitat in ten of the 11 years and at more than one site in eight of those years. The birds’ pattern of occurrence is examined. Acoustic Recording Units played an important part in these findings. Most birds were apparently present only briefly at individual sites at any time throughout the breeding season, from 17 May to 2 September. Nesting probably took place in 2014 and a nest with two eggs was found in 2023. Both attempts failed, most likely due to predation and/or weather. Two nests, from each of which two young successfully fledged, were found in 2024. Vocal behaviour on the probable/confirmed breeding occasions differed to other years and sites. Quite unlike the habitats occupied by Nightjars prior to their local extinction, the birds were primarily found in commercial forest clear-fells and restocks, and on average at a higher altitude than in the past.

Introduction

Historically, the European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus (hereafter Nightjar) was found across mainland Scotland and the Inner Hebrides, with breeding in the 1800s occurring north to the Atlantic coasts of Caithness and Sutherland (Harvie-Brown & Buckley 1887, Forrester et al. 2007). Numbers started to fall in the late 1800s and the geographic distribution contracted rapidly through the early 20th century. The decline was widespread throughout north-west Europe and is generally attributed to habitat loss as open ground was either built upon, converted to agriculture, or planted with conifers after the Second World War (Conway et al. 2007). Their eggs were much prized by collectors and, across the whole of Britain, there has also been a well-documented decrease in the large flying insects which form the major part of the Nightjar’s diet (Conrad et al. 2006, Evens et al. 2020, Mitchell et al. 2022). The species reached its lowest point about the time of the 1981 national Nightjar Survey but, between then and 2004, the number of singing birds in England more than doubled to an estimated 3,680 (Gribble 1983, Conway et al. 2007). This was largely attributed to an increase in suitable habitat as Nightjars colonised open areas created by storm damage and the rotational felling of the extensive conifer forests planted after 1945 (Morris et al. 1994, Langston et al. 2007). However, the significant gains made in England at this time did not extend north of the border. In the 1981 survey, only 33 singing males were counted in Scotland at sites in what was by then their core range of Dumfries, Galloway and Strathclyde (Gribble 1983, Morris et al. 1994). The next survey in 1992 found 41 singing birds in Scotland, one of which was in Strathspey (Morris et al. 1994) but only 27 were recorded during the 2004 survey (Conway et al. 2007).

The species’ tenuous foothold in Scotland remains in the south-west (Forrester et al. 2007). Between 2006 and 2015 the maximum number of churring males reported in Dumfries and Galloway was still only 21 (Gallagher 2016), but numbers have more than doubled in some years since then (Dumfries & Galloway Bird Reports). Elsewhere in Scotland, the Nightjar is still a very

1 As used here, North-East Scotland comprises Aberdeen City and the modern county of Aberdeenshire - the latter incorporating the historic Kincardineshire and part of the former county of Banffshire.

On 26 January 2024, while counting waders at Tyninghame estuary, East Lothian, towards the end of a spell of cold weather with the ground frozen, several passerines were feeding among washed up seaweed and other detritus. Besides the expected pipits and wagtails, there were Robins Erithacus rubecula, Blackbirds Turdus merula, Wrens Troglodytes troglodytes and a Dunnock Prunella modularis . These four ground feeding species foraged below or within two metres of cover. Two Long-tailed Tits Aegithalos caudatos appeared, first in a bush overhanging the beach, but then flew onto the sand about a metre from cover to forage among very small piles of detritus. They did this for five minutes until disturbed by a dog walker. A third tit appeared in the bush but did not venture onto the sand. Approximately one hour later, a party of six Long-tailed Tits appeared in another bush; two of them foraged on the sand as before, suggesting they were the same individuals. The other four stayed in the bushes or dropped onto the sand immediately below them. The group fed in the area for ten minutes then moved off. While feeding they did not walk,

but fluttered when changing position. I could not see what they were taking; it must have been very small. The beach is south facing and sheltered so was almost certainly warmer than surrounding areas. Perrins (1979) commented that Long-tailed Tits practically never come to the ground in search of food. Ian Andrews has helpfully drawn my attention to the following two accounts of this species feeding on the ground, one in a London park, the other in Epping Forest also in hard weather:

https://kensingtongardensandhydeparkbirds.blog spot.com/2019/02/the-great-black-backed-gullwas-back-on.html

https://britishbirds.co.uk/sites/default/files/V16_ N11_P306-314_N053.pdf

Reference

Perrins C.M. 1979. British Tits. Collins New Naturalist, London.

S.R.D. da Prato, 25 Fleets Grove, Tranent EH33 2QB.

Revised ms accepted February 2024

It is recognised that extreme storms can cause adverse effects upon marine benthic communities, which may be important as sea duck foraging zones (Rees et al. 1977, Brӓger et al. 1995, Elliott et al. 1998). Elkins (1988) recounts when persistent easterly gales caused heavy mortality to marine life off the Irish coast in January 1963, resulting in a marked decline in wintering Common Scoter Melanita nigra. However, there appears to be few other detailed accounts of storm impacts on sea ducks.

This note reports on sea duck behaviour within the outer Dornoch Firth, where favoured foraging zones are known (see Patterson et al. 2023). Observations suggest that successive extreme storm events in 2023 (Babet in

October and Debi in November) resulted in adverse impacts to near-shore coastal subtidal habitats. Both storms created sustained easterly gales, coupled with high wave/tidal conditions, causing erosion/damage to coastal habitats and shoreline infrastructure along east-facing coasts.

Following these extreme events, sea ducks were surveyed and unusual behaviours by Common Scoters and Long-tailed Ducks Clangula hyemalis were noted as follows:

a Use of known primary and secondary forage zones quickly declined, with birds utilizing unusual locations instead, including ‘high-energy’ near-shore areas (i.e. surf zones and rapid outflow channels).

In response to the dual effects of the climate emergency (global warming due to excess greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, largely derived from combustion of fossils fuels) and the biodiversity crisis (Scottish Government 2023), the Scottish Government (2024) provides grants through the government agency, Scottish Forestry (2024), to plant native as well as invasive nonnative/exotic species (e.g. Sitka Spruce; GB

Non-native Species Secretariat 2022). The rationale is that trees sequester carbon dioxide from the air, removing and storing it for varying lengths of time, and so helping prevent it from causing atmospheric warming. Some view woodland as being more biodiverse than open, treeless upland habitats, though evidence for this is equivocal depending on how ‘biodiverse’ is defined and the type of woodland involved (Royal Society of Edinburgh 2024).

An exhibition held at the Scottish Parliament in September featured a number of biodiversity projects in Scotland in order to raise the importance of biological recording, volunteer recorders, and biodiversity data to politicians and policy makers.

The exhibition was run by the National Biodiversity Network (NBN) Trust, and was coordinated by the Better Biodiversity Data (BBD) project. The BBD project is working to develop a fit-for-purpose infrastructure facilitating biodiversity data access and services across Scotland. The exhibition aimed to tell the stories of those involved in the collection, collation and use of biodiversity data, showcasing the importance of supporting a good biodiversity data infrastructure in Scotland.

The SOC’s Lothian branch was invited to feature some of the projects coordinated by the branch Discussion Group. This group was established in the 1960s, and during this time has been responsible for organising a raft of different ornithological fieldwork in the Lothians. The group meets monthly from September to April at Waterston House, the Club’s headquarters at Aberlady, east Lothian. Members include both very experienced field birders and relative newcomers to the hobby keen to become more involved in field study. They recognise the huge importance of robust data collected locally in supporting the conservation of the birds and their habitats, as well as the personal benefits that being outdoors with a purpose can bring.

The display featured two key projects coordinated by the group over the last 20 years. Firstly, there was the local bird atlas mapping the distribution of all birds in Lothian and Borders at the tetrad (2x2 km square) level. This was the second such

44:4 (2024)

atlas in the area, following another 20 years earlier, so we were also able to map changes in distribution. Data from these local projects contributed directly to the wider data collection for and publication of two bird atlases of Britain and Ireland led by the British Trust for Ornithology (e.g. Bird Atlas 2007–13). See: https://www.bto.org/ ourscience/projects/birdatlas/results/mapstore

In Lothian and Borders, over 850 volunteers took part in this mammoth project, recording their observations directly into a website set up for the purpose, and 11 organisers and authors analysed the data and published the results in a book (Murray et al. 2019. Birds in South-east Scotland 2007–2013).

The exhibition also showcased some comments from volunteers. Allan Finlayson of west Lothian took up fieldwork for the Atlas as a retirement project, having never done this type of work before. Although a long-term resident of the county, he discovered new areas for the first time, many of which were not only good for birds but also lovely places to walk in. He also met numerous helpful people: “Many people took a great interest in what I was doing. Some wanted to know what the survey was all about; others were very keen to tell me of the local birds they had seen themselves”. Despite initial reservations about the work becoming a chore or his competence in taking part, Allan says “within a few weeks I was completely hooked and enjoyed the whole project immensely”.

Following the success of the Atlas across the whole of Lothian and Borders - in particular how it brought new people into the hobby and how much it was enjoyed - we organised a short follow-up study just in east Lothian, and only in the winter months. We also used that project to invite new birders to team up with a mentor to help them learn the techniques and some bird identification skills. One of those mentored said: “I took a great deal of benefit from the scheme, I encountered new species,

This year Moorhens nested on the wildlife pond here at SOC Waterston House. We think this might be the first time this spot has been chosen by Moorhens for breeding. For the past two years, there had been a single Moorhen living on the pond, but this year, 2024, there were a pair, and for those of us who work in the offices overlooking the pond, and visitors to Waterston House, it provided a summer of drama.

Nest building was clearly in progress in springtime, with strands of reed and grasses being taken into the thick vegetation at the back of the pond. We left the pair well alone and just watched their activity from the windows. Moorhens make a number of ‘platforms’ before selecting one as a nest (Forrester et al. 2007), and through much of April only one bird was seen on the pond at any one time so we were hopeful that meant incubation was underway. Both adults in a pair will incubate the eggs, and, on average, the eggs hatch synchronously on the 22nd day of incubation (Forrester et al. 2007). The first brood hatched around 8 May 2024, we counted five chicks but they were very secretive and spent most of their time deep in the pondside vegetation. By late May though, they were much more confident and could be seen out on the pond feeding with the

adults. They also quickly learnt to hang around underneath the bird feeder for seed dropped by the Tree Sparrows, Chaffinches and tits feeding above.

From their hatching as tiny black fluffy chicks which grew into dull-coloured replicas of their parents, the Moorhen family on the pond provided a great attraction to visitors to Waterston House. Looking out the feature windows in the Library or Gallery they were easy to see and provided a frequent talking point.

The book reviews published in Scottish Birds reflect the views of the named reviewers and not those of the SOC.

Avian Architecture: How Birds Design, Engineer, and Build (Revised and Expanded Edition). 2024. Peter Goodfellow. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford. ISBN: 9780691255460. 176 pages, 300+ colour photos and colour & b/w illustrations, hardback, £25.00.

I had not read the first, 2011, edition of this book so this was a ‘new’ read for me. One thing that immediately caught my eye was how attractively it is laid out. The several hundred full colour images make it both a visual delight and greatly add to understanding the descriptions in the text.

Each of the 12 chapters focuses on a different nest construction, increasing in complexity of design from a basic scrape through to mud nests, colonial nests and nests of saliva. The final two chapters consider bowers and food storage. Within each chapter a consistent formula of blueprint, materials, features and technique is given, followed by case studies which are variations on the chapter’s theme. Case studies are taken from across the globe so, for ‘Aquatic nests’, we have Horned (Slavonian) Grebe, African Jacana, Black Tern and Common Moorhen, which I feel maximises the book’s appeal.

Avian nests in particular are truly amazing. The sheer ingenuity of their construction, and especially the engineering analogies, is really brought out in this book. As examples: the Sootycapped Hermit (a hummingbird species) adds mud pellets to the hanging end of its nest as counterweights for stability; the Goldcrest, having first sewn together moss and lichen with spider gossamer, then lines this framework with feathers and hair to provide a thick layer of insulation. As you can tell, I really enjoyed reading this book and learnt much along the way!

Rosie Filipiak

The last of its kind: The search for the Great Auk and the discovery of extinction Gisli Palsson, 2024. Princeton University Press, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-691-23098-6, hardback, 291 pages, 16 colour plates and numerous b/w illustrations.

In the spring of 1858, John Wolley and Alfred Newton (two young Cambridge graduates), embarked on an expedition to SW Iceland. They had long cherished the notion that the Great Auk might still be surviving on the rock stac of Eldey and had previously made an agreement with a Danish merchant to collect a specimen and any eggs they could secure. This fascinating book describes in considerable detail their time in Iceland, where they waited for a sufficiently calm sea to make a landing. They were, however, not idle during this period but spent their time interviewing local fishermen who had seen and taken the Great Auk in recent years and who may thus unknowingly have contributed to their extinction. To his everlasting credit Wolley produced five notebooks, now known as The Gare-fowl Books, which are still held in the University Library in Cambridge and were the primary source of reference for this book.

The author, an Icelandic Professor, explores every possible angle concerning the history of this enigmatic auk. In the final chapters he covers Newtonian Extinction, as befits an anthropologist of some note. Since the publication of this book, the area of Iceland described has seen spectacular volcanic eruptions. This is a reminder that the breeding places of the Great Auk in Iceland were never safe and indeed one of the stacks has completely disappeared under the ocean.

I recommend this book; it is a good, if sad, story well written and nicely illustrated.

David Clugston

44:4 (2024)

Observatories’ Roundup is a regular bi-annual feature about our bird observatories in Scotland. The intention is to publicise the work of the observatories, visiting opportunities, as well as incidental snippets of news from the islands.

Fair Isle Bird Observatory

May on Fair Isle will be remembered by those lucky enough to be present on the isle for a long time to come, with multiple falls of common and scarce migrants, several in record-breaking numbers, and some top-tier rarities bookending the month.

A stunning male Collared Flycatcher was the highlight of the first wave of birds on 2 May, with a supporting cast of 14 Wryneck, six Icterine Warbler, two Red-backed Shrike, two Bluethroat and four Wood Warbler. Throughout the next few days, the birds kept arriving, with peaks of six Red-backed Shrike, 12 Wood Warbler, 55 Lesser Whitethroat and 109 Willow Warbler in the first week of May, as well as two different Common Nightingale, a Little Bunting, Quail and Garganey. A fly-through Black Kite on 9th was the fifth isle record, and Little Ringed Plovers on 12th and 15th were the eleventh and twelth occurrences of this increasing species.

A spell of south-easterlies from 16th heralded the beginning of an unprecedented period of arrival, with Red-backed Shrikes the standout highlight.

An incredible 32 were present on 17th, along with four each of Bluethroat and Marsh Warbler, two Hawfinch and a Wryneck. This total was, amazingly, to be bettered again a few days later, with one of Fair Isle’s best spring birding days ever on 22 May. After a slow start to census, arrivals began from early afternoon, and by the time darkness fell and totals added up, an astonishing 37 Red-backed Shrike, 34 Icterine Warbler, seven Bluethroat, six Marsh Warbler, a rare spring Barred Warbler, Blyth’s Reed Warbler and Common Nightingale had been logged.

Birds continued to come, with a female Subalpine Warbler sp. and Rustic Bunting on 25th, along with three Grey-headed Wagtail and a pair of Dotterel. A Tawny Pipit on 27th coincided with a new day record of 14 Marsh Warbler and a second Nightjar in two days, before the 29th saw a new species added to the island list, with a stunning male Marmora’s Warbler found in the late afternoon. It went on to show very well to the assembled crowd, and was trapped the next day as it moved to the Gully, even singing in the hand (see Scottish Birds 44: 286–288).

I.J. ANDREWS

A month after the departure of our local Swiftsthe last was recorded on 27 September - there was a series of reports of late swifts in east Lothian between 27 October and 2 November 2022. These were identified and accepted by BBRC as Pallid Swifts and represent the first records for Lothian.

There were other accepted Scottish records of Pallid Swifts at this time in Fife (two), Highland (two), Moray & Nairn (three) and North-East Scotland (three) (Bacon et al. 2023). Others were claimed in Angus & Dundee (three), Borders (four), North-East Scotland (additional four), Outer Hebrides (one) and Perth & Kinross (one) (per BirdGuides). I am not aware that any late swifts proved to be Common Swifts at this time.

Separating Pallid Swifts from Swifts in autumn is a challenge. Firstly, proof of identification is greatly helped by photographs, and swifts are notoriously difficult to photograph. Secondly, the definitive identification criteria are only now being confirmed (Larsson 2018, Reyt & Duquet 2020, 2021) and there appear to be some contradictions even within recent publications. Thirdly, swifts are long-distance migrants and the identification of potential vagrant juvenile pekinensis Common Swifts from China in late autumn is, to my knowledge, still to be fully resolved (Lewington 1999, Reyt & Roques 2022).

Dunbar, up to four, unaged, 27 October to 2 November 2022

Rosie Filipiak saw the first of the swifts in the late influx - two at Dunbar Golf Course in the afternoon of 27 October. After reports of three swifts at Barns Ness, Mark Cavanagh later saw three back over the golf course and these were then seen flying towards the harbour at dusk. None were seen on the 28th. Next day, two were seen over Belhaven, but they headed north towards Tyninghame Bay. Four over Dunbar swimming pool on

(2024)

30th were watched by a small group of birders, then three were at Fluke Dub, east of Dunbar on 31st. There were later sightings at Dunbar Golf Course and Belhaven on 1 November and finally, an unconfirmed report at Tyninghame on 2nd. These were all identified as Pallid Swifts and Calum Scott put the submission together for BBRC.

Yellowcraig, unaged, 30 October 2022

Following up a sighting of two swifts over North Berwick by Graeme Buchanan, the disappearance of at least one of these in the direction of Yellowcraig, prompted me to drive round in that direction. Fortuitously, one remained there for several hours in the afternoon and was seen by a small number of people. It was identified as a Pallid Swift.

Port Seton, 1cy, 31 October 2022

Kevin Ritchie reported a swift on Twitter at about 10:00 hrs which was then followed up by several people including Mike Hodgkin, Dennis Morrison and myself.

The following description and annotated montage (Figure 1) are based entirely on photographs taken of the Port Seton bird over a period of 20 minutes - the bird was flying around so fast, silhouetted against a leaden sky, that it just looked dark and little detail could be discerned at the time.

A combination of the features noted in Figure 1 was used to identify the Port Seton bird, but the importance of the head pattern should be stressed:

n Extensive pale throat patch, poorly defined and merging with generally pale brown head (c.f. well-defined, clearly demarcated whitish face of Common Swift).

n Obvious ‘eye patch’ or so-called ‘alien eye’an oval dark area encompasses the eye and extends towards the bill. The dark eye contrasts

Plate 288. Pacific Diver, Colgrave Sound, off Brough, Fetlar, Shetland, 19 May 2023. © Brydon Thomason

Ask any Shetland birder how many Blackthroated Divers (hereafter BTD) they have seen here and it is quite likely to be so few that they could recount them all; ask this of summerplumage individuals, the answer might barely be one! This is certainly the case for me, and only once ever have I had the chance to enjoy their full summer splendour. Even back then, well over ten years ago, the careful process of eliminating Pacific Diver (hereafter PD), however unlikely a summer-plumaged bird might have felt at the time, was undertaken. Thinking back to that bird, nothing about its structure suggested anything other than BTD.

That bird, process and the first impressions it gave came right back to me when I picked up a summer-plumaged ‘black-throated’ diver through my binoculars off Brough Lodge, Fetlar on 19 May 2023. I was in the process of facilitating ‘scope views of a flock of five Common Scoter for the birding tour-group I

was leading. Stepping back to the ‘scope and jumping the queue to view, I asked if I could reposition the ‘scope onto the diver, my excitement already elevated at even a Blackthroated Diver. The bird was actively foraging, barely on the surface for 10–20 seconds at first, but working its way towards us approximately 300–400 metres away from where we watched, at the road end by the old slipway.

In the ‘scope, although my first view was brief, its posture when actively foraging made the bill look slim and disproportionally short for the head and overall body, much more similar to profile of Red-Throated Diver (hereafter RTD) as opposed to a Great-Northern Diver, than I would expect for BTD. A second, slightly longer view gave an even better impression to suggest a contender for Pacific. I tried to calmly explain to the group that I needed another couple of views of the bird as it may well be an even better bird than Black-throated. As I did

T. BECKETT

I started university at St Andrews three years ago, having moved up from Edinburgh. From leading regular walks with the University’s Birding Society to twitching rarities on the Eden Estuary and at Kilminning, birding has formed a large part of my student life. Local patch watching has always been at the centre though, and I have spent much of my free time birding in and around St Andrews, as well as doing monthly WeBS counts for the past two years. I had always hoped to find a significant rarity on my local university patch, and heading into my fourth and final year I was aware that time was running out to achieve this goal...

On the evening of 24 July, I decided to go for a quick walk along the coast in St Andrews, a short walk from my student flat. I planned to briefly check for waders, with a friend having seen Common Sandpiper there the previous day,

alongside the returning Redshanks and Turnstones. Arriving by the cathedral just before 20:00 hrs, I stopped to scan through the waders with binoculars. Most were feeding actively along the exposed shoreline as the tide receded, although a few were still resting. I was immediately struck by an odd grey wader resting amongst a couple of Redshanks. I quickly noted its striking yellow legs, in clear contrast to the adjacent Redshanks. I frantically set up my scope and relocated the mystery wader. As the birds started to feed actively, I could see that it was a Tringa. At this point alarm bells were ringing, as I realised I was likely looking at a Lesser Yellowlegs. Compared to the Redshanks, it had a notably more slender build, and much greyer plumage. The bill was much darker too, and evidently straight, eliminating Greenshank (which would itself be a decent bird in this part of the patch) as a possibility.

Plate 303. From the gloom of winter came an unexpected summer. Capturing this Barn Owl in beautiful evening light in June was a really uplifting experience. My own small parliament of friends and acquaintances on Baron's Haugh sadly lost Tony McGowan in January 2023. Finding inspiration in some of the remarkable people around me, past and present, is key to my own self-improvement and motivation to try to capture natural images of nature. Memento vivere

Frank Gibbons, Motherwell, Clyde. Email: frank76g@outlook.com

Equipment used: Canon EOS R3 camera, Canon EF 500mm F4 mk2 lens + 1.4x extender, Manual, 1/1,600 second, ISO 4,000. f5.6.

Featuring the best images posted on the SOC website each quarter, PhotoSpot will present stunning portraits as well as record shots of something interesting, accompanied by the story behind the photograph and the equipment used. Upload your photos now - it’s open to all.