2 Foreword R.F. Briggs

PAPERS & SHORT NOTES

3 Birds and place: an ornithological toponymy of the Outer Hebrides F. Rennie

16 Observations on Meadow Pipits in mist-net catches during post-breeding moult B. Lynch

20 Bioacoustic tracking of Corncrakes on the Isle of Skye R.M. Arnold

30 LETTER - What does IOC stand for? S.P. Dudley

30 Brood defence by Curlews against unlikely threats R. Summers & B. Kalejta-Summers

32 Sheep’s wool - an additional threat to breeding Curlews R. Summers

33 Breeding Ringed Plovers on a Cairngorms hilltop P. Gordon

34 Recent colonisation of Jays in Caithness and north-east Sutherland R.D. Hughes

ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS

37 SOC Annual Conference 2024: weathering the storm together

42 NEWS AND NOTICES

49 OBITUARIES

Dr. Graham Cooper (1941–2024) D. Balmer, C. Marsden, P. Grant & I. Francis

50 YOUNG VOICES

Field Notes: a trip to Cramond Island, Lothian, 13 October 2024 A. Kane

54 The SOC Donald Watson Collection - a retrospective exhibition at Waterston House, September 2024 R. Filipiak

56 The Big Belly Bin Project R. Hunter Pepper & R. Watt

58 Repelling the invaders: Orkney Stoats & Hebridean Hedgehogs A. Barker

60 Good news (and some bad) from the South of Scotland Golden Eagle Project C. Barlow

63 Glenturret Estate under new management A. Barker

64 BOOK REVIEWS compiled by N. Picozzi

66 RINGERS' ROUNDUP R. Duncan

71 SCOTTISH BIRDS RECORDS COMMITTEE (SBRC) QUARTERLY BULLETIN D. Steel

73 The Balearic Shearwater in Fife C.J. McInerny, A.W. Lauder, K.D. Shaw, J. Wilson & M. Ware

77 Eastern Lesser Whitethroats on the Isle of May in October 2023, including the first record of Central Asian Lesser Whitethroat (Curruca curruca halimodendri) A.W. Lauder, S. Pinder & K.D. Shaw

80 An exceptional birding year on St Kilda, Outer Hebrides C. Nisbet

86 Tennessee Warbler, Fair Isle, 15–19 September 2024 - third record for Fair Isle N. O’Hanlon & R.D. Hughes

88 Spotted Sandpiper at Cameron Reservoir, 25 September to 18 November 2024 - first Fife record J. Wilson

90 Eastern Crowned Warbler, Sandness, Shetland, 3 October 2024 - first Scottish record P.V. Harvey

94 Isabelline Wheatear, nr Collieston, 19 October 2024 - second North-East Scotland record D. Bean

BC Grey Heron J. Stevenson

(2025)

This winter, I spent time looking through very early editions of Scottish Birds, all conveniently available via our website. While the SOC was founded in 1936, the journal, in a form that we can recognise today, was first produced in 1958. As the latter date is within my lifetime, it doesn’t feel that long ago!

I was both humbled and inspired to recognise again the names and words of so many well-known, eminent scientists, ornithologists and leaders - too many to list here. Alongside their professional careers, they were making both the Club and the journal what they were then, and what they still are. The foundations they laid, for research, for fieldwork and for other activities led by the SOC, inform much that members support today. Their achievements certainly influenced my own interest and learning, both as a student in the 1970s and during my conservation career.

The Scottish Birds of 1958 assumed responsibility, previously held by the Scottish Naturalist, for publishing scientific papers about birds in Scotland. But the first editorial also made clear that it sought to provide other material ‘for members whose outlook is not wholly scientific’. Scottish Birds has continued to evolve and we have a strong team of editors who still offer us that balance. They also seek to innovate and in this particular issue I’m delighted to welcome the first of a planned series of contributions from ‘Young Voices’. Perhaps a taste of things to come and definitely an invitation to current students and young birders to share your enthusiasm and experiences through these pages.

Back to the early issues, where I was also fascinated to read notes of birds discovered in the 1950s: the first Scottish record of breeding Collared Doves, in Morayshire; the first Kinross-shire Buzzard; the first Wrens breeding on the Isle of May. How quickly nature changes around us, and hence how important the records are.

Out on local farmland one day this winter, I came across a sizeable gathering of Fieldfares and Redwings. ‘Interesting, but not particularly unusual’ was my reaction, and ‘would anyone really want or need to know?’. Then I recalled the work of Local Bird Recorders and all who compile our Annual Bird Reports and how important it is for us to understand the distributions and numbers of commoner as well as rarer species. So I popped the record on to BirdTrack as a wee contribution to all that. Whether specialist or generalist, we can all do that and contribute to the bigger picture. Nowadays, we might think relatively little about Collared Doves, Buzzards and Wrens, but who knows what the future might hold and how important today’s seemingly unimportant records might become?

Lastly, I just have space to give you a heads-up about our Council’s enthusiastic agreement for the SOC to be Scotland’s partner to the BTO in gathering data and preparing the next UK-wide Bird Atlas. More on this as plans develop; it’s certainly an important project and an opportunity for us all to look forward to. Have a good spring.

Ruth Briggs, SOC President

F. RENNIE

Looking at the maps of the Outer Hebrides, both recent and historical, it is apparent that a great many of the Gaelic place names describe attributes of the topography and landscape. This article explores the specific connection with place names of the Outer Hebrides that relate to birds and are noted on the current Ordnance Survey maps. Changes in the Gaelic orthography over the years, together with a general move from lots of regional names for birds to greater standardisation, make it difficult to translate some place names with certainty, particularly in older accounts, but the list is long and informative. The article explains some of these challenges and identifies a range of localities of interest. Hopefully, this may encourage a more comprehensive study of other geographical areas.

Introduction

One of the pleasures of watching birds is to be out in the countryside and able to appreciate the varied landscapes that provide the habitats for so many different species. With a little additional knowledge, some of the names of the places that have been given to that landscape can provide interesting, and often surprising, insights into the associations of birds with specific places. Some sites bear traditional names, often alluding to the longevity of species association, while others appear to be more cryptic, and still others are marked by their surprising absence from the map. Although bird locations in many regions of the country continue to be recognised by their Scots, including Doric and Shetlandic, dialects or English place-names, the historical decline of spoken Gaelic and its geographical confinement to largely the northwest mainland and islands have resulted in a loss of understanding by many people of the rich nomenclature that persists. The strong oral tradition of Gaelic, however, reveals a deep awareness in the culture of the presence of avian species in the surrounding environment.

For a long period of time, the account by Harvie-Brown and Buckley (1888) was the most important source of information on birds in the Outer Hebrides (ap Rheinallt 2010), but there was also a great deal of information sharing between several near-contemporary sources, including Gray (1871), Forbes (1905), Harvie-Brown, and the multi-volume collection of folklore by Alexander Carmichael (1900–1971). Worth noting is the fact that the names were often collected for different purposes. Forbes, for example, focuses exclusively on information about bird names, whereas both Gray and Harvie-Brown are more concerned with the ornithology, and apparently include the Gaelic names as a contextual background. There were, frequently, multiple local names for the same species (there still are many less-used regional variations) and often contradictory naming which might identify only to the generic level in one district, but with the same name referring to a different species in another region. Unsurprisingly, this is often reflected in the naming of places in the landscape associated with birds. Many of these place names are passed unnoticed by contemporary birdwatchers, hillwalkers, and tourists, but their recognition can tell a lot about the previous human ecology of the area.

The indigenous Gaelic language of Scotland has a finely nuanced lexicon of place names describing the physical topography of the land in considerable detail. In addition to terms discerning the colours, shapes, shades, surface texture, and even the vegetation of a particular

Over 2,000 Meadow Pipits were mist-netted in Glen Clova, Angus, during late July to mid-October from 2012 to 2017. Adults were caught throughout this period, except for 27 days in August each year when adults were undergoing the main part of their post-breeding moult. It is suggested that reduced ability to fly influences the birds’ behaviour.

Introduction

In the UK, the Meadow Pipit Anthus pratensis breeds between April and July (Simms 1992, Forrester et al. 2007). Post-breeding populations then form loose flocks and move to lower altitudes during August and September, where both adults and juveniles undergo moults prior to their autumn migration (Wernham et al. 2002). At a site in southern Scotland, using an audio lure of male territorial song, Dougall (1993) and Dougall & Craig (1997) reported very few adult Meadow Pipits being caught in mist-nets during August and September. In their combined studies, adults comprised only 0.37% of all birds trapped; six adults out of a total of 1,619 birds. They suggested there may be an age bias in tape-luring Meadow Pipits during this period.

Methods

Using the same mist-netting methods as in the south of Scotland studies, I mist-netted a total of 2,383 Meadow Pipits during the post-breeding period mid-July to mid-October, at low altitude sites in Glen Clova, Angus (56o N 3o W: 220m asl), over the years 2012 to 2017. From 2012 to August 2015, catching sessions involved the use of two or three 2-shelf mist-nets set near the boundary fences of fields grazed by livestock. In the latter part of 2015 and during 2016 and 2017, three full height, 4-shelf North Ronaldsay super-fine nets were set as an open triangle (Maguire 1985) near the boundary fence of an improved pasture previously grazed by sheep and cattle over the summer. All mist-net sites involved small areas of Soft Rush Juncus effusus and catching sessions lasted between three and five hours. Juveniles and adults were aged on plumage characteristics (Svensson 2002).

Table 1. Proportions of adult Meadow Pipits mist-netted in Glen Clova, Angus during the post breeding period, mid-July to mid-October 2012 to 2017.

Year Adults & Juveniles

The annual proportion of adults trapped (Table 1) was greater in all years, and very much greater in 2015 and 2016, than that reported by Dougall & Craig (1997). In all years, the occurrence of adults in mist-net catches showed a consistent pattern (Figure 1). Adults were caught during July and early August (Days 1–32); no adults were mistnetted during a 27-day period from Day 33 (2 August) to Day 59 (28 August); with adults again mist-netted from 29 August to 18 October (Days 58–110). Generally, the number of adults caught decreased from late September onwards.

This paper describes an attempt to track the movements of male Corncrakes on the Isle of Skye in 2020–23 by analysing the fine structure of their calls, using an established technique, but using new technology, mobile phones and free audio software. It was confirmed that this equipment was adequate for the task, provided the quality of the recording was evaluated appropriately. The intention was to add movement information to the collection of short audio recordings that had already been made for several years. The analysis of results required a modification of the established technique to distinguish individuals more reliably, because of the sharing of patterns by different birds. Movements of individuals were mapped with reasonable certainty and some possible returning birds identified.

Introduction

Breeding Corncrakes Crex crex are secretive, live in dense vegetation and often the only sign that they are present is hearing their call. The males call for long periods in the night, both to attract a female and to repel rivals (Cramp & Simmons 1980). The method used for monitoring the Corncrake population in the UK and Ireland relies on these vocal signals, with interpretation and analysis based on radio-tracking studies of tagged males (Stowe & Hudson 1988, 1991). Peake et al. (1998) established that there is a high level of individuality in the fine structure of Corncrake calls and further study suggested that using the calls as a non-intrusive technique could be applied to test the efficacy of census and monitoring methods (Peake & MacGregor 2001) and also could generate useful conservation information on the behavioural habits of individual birds (Terry et al. 2005).

During the Corncrake annual census and land management work by the RSPB on the Isle of Skye, a collection of about 300 short mobile phone recordings of calling males had been accumulated between 2012 and 2019. The majority were made by the RSPB Skye Corncrake Project Officer, Shelagh Parlane. In 2019, we decided to see if this archive could reveal more information on individual Corncrake

Malcolm Ogilvie’s excellent article on Canada Goose subspecies in the September issue of Scottish Birds refers to the IOC World Bird List as the ‘International Ornithological Congress’. Nigel Collar did the same in his Ibis article, Taxonomy as tyranny (https://onlinelibrary. wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ibi.12569), but corrected it in this corrigendum (https://online library.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ibi.12613)that is, IOC in Gill & Donsker’s list stands for the ‘International Ornithological Community’. (Gill, F.B. & Donsker, D. (eds) 2017. IOC World Bird List (v7.3) at: https://doi.org/10.14344/ ioc.ml.7.3.) Gill & Donsker have seemingly never gone out of their way to correct any misappro-

priation of their IOC World Bird List to the International Ornithological Congress (now IOU of course). When the BOU adopted the IOC World Bird List in 2017, in their submission to the BOU they did not spell this out (we too presumed IOC referred to International Ornithological Congress) and it was only after Nigel Collar’s published corrigendum that the BOU sought clarification from them on this and they ‘fessed up’. I raise this in case others should refer to the IOC World Bird List incorrectly in the future.

Steve P. Dudley, Monivey, Westray, Orkney Isles KW17 2DW.

Email: stevedudley787@gmail.com

Although most wader chicks can feed themselves upon hatching, they nevertheless depend on their parents for care. This can involve brooding the chicks when the weather is cold or wet, leading them to favourable feeding areas, alerting them to danger with alarm calls and defending them from threats. The chicks’ response is important if the danger involves a predator. They may either hide in dense vegetation or crouch down, relying on their camouflaged down or feathers to avoid detection.

Here, we describe brood defence by a pair of Curlews Numenius arquata that had a brood of four downy chicks on moorland with grassy patches in Strath Dearn, Invernessshire. In May 2023, we observed the pair and chicks foraging over rough grassland. The male had been colour-ringed on the Beauly Firth where it over-winters and where it was identified as a male based on the length of its bill - males having shorter bills than females.

On 23–24 November, the Club’s Annual Conference brought members and bird enthusiasts together at the picturesque Atholl Palace Hotel in Pitlochry. The hotel’s stately charm provided a perfect backdrop for our programmed gathering, but in reality Storm Bert had other plans, sweeping across the country and making travel a significant challenge. The storm tested the resilience of staff, speakers and attendees alike. While numbers were understandably lower than anticipated, those who made it found refuge, camaraderie, and inspiration, all making for a memorable weekend. We are incredibly grateful to all the speakers who delivered inspiring talks, and to the attendees who managed to join us.

The weekend’s programme offered something for everyone, blending engaging talks, networking opportunities, workshops, and delightful evening entertainment. Delegates cosied up with steaming cups of tea and coffee, ready to absorb a range of thought-provoking presentations highlighting the richness and diversity of our bird life. In true SOC fashion, even the storm couldn’t dampen the adventurous spirit of some

attendees who braved the elements for a walk to the nearby Black Spot Waterfall. With raincoats zipped and binoculars in hand, they trekked through wind and snow to this scenic spot.

‘Young Voices’ is a new series of articles highlighting the contributions and experiences of young birders in Scotland. If you’d like to contribute, please get in touch with Asia Kane: youngvoices@the-soc.org.uk ...we’d love to read your story!

I’m currently attending the University of Edinburgh, so in this first ‘Young Voices’ article I’m writing about our recent field trip run by BirdSoc, the university's birding society. With a committed and growing membership, BirdSoc welcomes students from all disciplines and with all kinds of backgrounds. Our goal is to inspire more young people to take up birding and to spark a passion for the natural world.

On Sunday 13 October, we set out on our second trip of the semester - a visit to Cramond, located in north-west Edinburgh where the River

Almond meets the Firth of Forth. This site is partic ularly good for waders, seabirds, and a selection of woodland birds, all of which can be seen on the waters of the Firth or along the river walkway. We especially hoped to see Kingfishers and Dippers, both of which are regular sights in the area.

Plate 35. Lapwing. © Thomas Richardson

around 12:00 hrs, after taking a bus from Lothian Road. Luckily, the weather was bright and clear, and even the wind off the sea was less biting than we had expected. Due to tide times, we were unable to cross to Cramond Island itself, so we spent some time observing the waders at the mouth of the river. Here, we were rewarded with large flocks of Curlews and

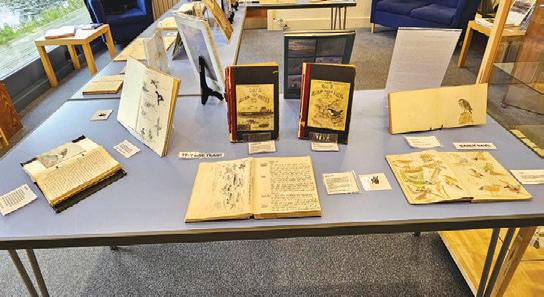

Featuring the paintings of Donald Watson held by the SOC, and archive material ranging from some of his earliest childhood drawings to sketchbooks full of commercial prep work, this retrospective exhibition ran from18–22 September, 2024.

All the stages of Donald Watson’s artistic and ornithological life were featured in the exhibition, which provided a rare opportunity to see the chronological development of his skill as an artist and development as an ornithologist.

What did children do before the internet? Playing card games seems to have been a firm favourite with many families, including the Watsons. Donald even made his own cards - from the SOC Archive we had his hand-drawn ‘Happy Families’ cards on display, featuring, yes, birds, very beautifully depicted and coloured. Interestingly, a Watson family member visiting the exhibition mentioned that one of Donald’s brothers also made bird cards so what we have in the Archive may well be a mix of the brothers’ sets.

Throughout his teens, Donald kept meticulous ‘Illustrated Bird Notes’, and several of these notebooks were on display. In his later teens, these morphed into ‘Ornithology Notes’; one of

these records that whilst on the Isle of May in September of 1936, he spotted a bird new to him. After alerting other birders on the island, it was eventually persuaded into one of the traps and definitively identified as a Yellow-breasted Bunting - a first for the Isle of May!

Did you ever have The Oxford Book of Birds? First published in 1964, this book has 96 colour plates, all painted by Donald - at a rate of one plate per week for two years. On show at the exhibition was his sketchbook from those years, with pencil renderings of the mock-ups for each plate - a fascinating insight into how the various stages of this book were produced.

Rubbish bins and birds

Issues with gulls in urban areas continue to make headlines in the media. Problems intensify when the birds are breeding as they can become aggressive when defending young.

A recent survey by Lothian SOC members counted over 1,000 nests of Herring and Lesser Black-backed Gulls in and around Edinburgh, often on flat roofs. Access limitations mean the true figure will be even higher. At the same time, conservationists point to declines in numbers in more natural sites such as sea cliffs and islands. The main factor encouraging gulls into towns is food in the form of human leftovers, easily available from conventional rubbish bins, especially when they overflow.

Providing bins that are bird proof and have enough capacity to deal with what can be large quantities of rubbish can greatly reduce the problem. In North Berwick, Johnn Stevens’ East Lothian Council Amenity Services staff were having to empty conventional bins three times a day in summer. There are now six additional big belly bins. These large, covered bins which each cost c. £5,000 compress rubbish and have a capacity at least five times that of conventional bins. They can communicate electronically when they need to be emptied. Users are encouraged to separate out food-contaminated rubbish before placing it in the bin (e.g. by ripping the top off pizza boxes or chip containers). Local food outlets agreed to stop using polystyrene containers in advance of national legislation. The material then goes to a depot where it is put into a closed skip which birds cannot access. All East Lothian rubbish is now mechanically sorted to maximize recycling. No material now goes to landfill, although some is incinerated, a process not everyone is happy about. All the bins feature seabirds painted by six local artists. Each bin has a QR code with info on the birds, project, and waste recycling.

Thank you very much to the many ringers, ringing groups, birders and the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) who provided the information for this latest round up. Thanks also to the many bird watchers and folk who take the time and trouble to read rings in the field or find dead ringed birds and report them.

If you have any interesting ringing recoveries, articles, wee stories, project updates or requests for information which you would like to be included in the next issue, please email to Raymond Duncan at rduncan393@outlook.com.

For lots more exciting facts, figures, numbers and movements log on to http://www.bto.org/volunteer-surveys/ringing/publications/online-ringing-reports

Interesting ringing movements

Chk = chick Juv = juvenile,

Im = Immature Ad = adult,

Unk = unknown

M = male, F = female

Dead = dead, Sghtd = ring(s) read in field Rtpd = retrapped

Blackbird

Last Ringers’ Roundup featured four foreignringed Blackbirds on the Isle of May in October 2023. This time it’s North Ronaldsay, with three birds ringed there and recovered elsewhere and also an old recapture of an Essex bird in North Berwick.

LR70742 JuvM 08/04/24 North Ronaldsay, Orkney

Dead 15/04/24 Sevred, Fristad, Alvsborg, Sweden, 905 km ESE, 7 days

Interesting to see the timing of migration of this Scandinavian Blackbird. Our local Blackbirds will be on territory and the earliest well into nest building/egg laying by mid-April.

LR70154 JuvM 23/11/22 North Ronaldsay, Orkney

Dead 01/05/24 Suopelto, Sysma, Mikkeli, Finland, 1,552 km E, 1 yr 158 days

XN87230 JuvM 06/04/84 North Ronaldsay, Orkney

Ring 22/06/24 Llandyssil, Powys, Wales, 759 km S, 40 yrs 46 days

This one took 40 years to get recovered. Ring was only found with the use of a metal detector. Well done the Detectorist!

LJ50127 JuvF 20/01/17 Essex

Rtpd 26/11/23 North Berwick, East Lothian, 488 km E, 6 yrs 306 days

The tern raft at Montrose Basin: a conservation success by Ben Herschell. The tern raft was launched in 2008 by the Scottish Wildlife Trust (SWT). Named Maid of Sterna Stuff, it is situated about 100 m from the shore near the SWT Visitor Centre, in a channel of the River South Esk. Even at the lowest tides, the raft remains surrounded by water. Its design - floating high above the water surface and edges protected by boards topped with wire mesh - serves as an effective deterrent against all but avian predators. The nesting area on the raft is covered with coarsely crushed scallop shells. The terns create shallow scrapes in this substrate, where they lay up to three eggs. Terracotta shelters are available for the vulnerable chicks.

Access to the raft is carefully controlled to minimize disturbance. Tay RG ringers can visit it during low tide, adhering to strict time limits. Since its launch, a total of 450 birds have been ringed on the raft. The annual numbers are as follows: 2009 = 62; 2010 = 102; 2011 = 128; 2015 = 71; 2024 = 87.

In some years, no ringing was possible due to various circumstances, including maintenance, crow predation, restricted access during COVID19 lockdowns, and outbreaks of avian flu. However, 2024 marked a welcome return to this conservation initiative.

Birds from the raft have been retrapped in several locations, highlighting their migration patterns. These locations include Seal Sands, Teesmouth (twice); Forvie, Ythan Estuary

C.J. MCINERNY, A.W. LAUDER, K.D. SHAW, J. WILSON & M. WARE

The Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus is one of the rarest birds in Europe. The global population is currently estimated to be just 2,900–3,000 pairs, which equates to 5,800–5,900 mature individuals, all breeding on islands in the western Mediterranean Sea. Its main threats are fisheries by-catch at sea and predation at breeding colonies by introduced mammals. Population models predict a 14% annual decline, which leads to a predicted decrease of 80–99% over 41 years equating to three generations, hence qualifying the species as Critically Endangered under IUCN criteria (BirdLife International 2021).

The Balearic Shearwater has had a tortuous taxonomic history (Genovart et al. 2007, Onley & Scofield 2007). Once considered a subspecies of Manx Shearwater P. puffinus it was split from Manx Shearwater, resulting in Manx, Balearic and Yelkouan Shearwater P. yelkouan being considered as three separate species (Sangster et al. 2002). However, more recent genetic evidence suggests that Yelkouan and

45:1 (2025)

Balearic Shearwaters are, in fact, one species (Obiol et at. 2022). Furthermore, it also appears that Manx Shearwater is more closely related to Townsend’s Shearwater P. auricularis and Barolo Shearwater P. baroli

The critically endangered status of Balearic Shearwater has prompted much study of the species to inform its conservation, with monitoring revealing the importance of waters in the north-east Atlantic for this seabird as part of its life cycle. Philips et al. (2021) showed that between 652 (in 2017) and 6,904 (in 2014) individuals were using British and Irish coastal waters through the post-breeding season from July to October, a significant proportion of the global population of the species. Furthermore, Lewin et al. (2024) demonstrated a recent northwards shift in post-breeding distribution, with these changes reflecting the adaptability of individuals responding to variations in environmental conditions and food availability, likely associated with climate change.

C. NISBET

The dust has settled after the 2024 St Kilda fieldwork season and the NTS staff are now able to reflect on one of the most exciting birding seasons of all time on the archipelago. In my role as St Kilda Seabird and Marine Ranger, my main task at the end of the season is to summarize the monitoring and research that has taken place in an annual report, with the seabird data being collated nationally through the Seabird Monitoring Programme.

My immediate reflections on this season, however, brought up an altogether more remarkable story. Alongside my primary role on the island, I also collate biological records annually. This involves recording interesting and unusual plants, fungi, invertebrates, cetaceans, and, of course, birds as they pass through, or are blown onto St Kilda. Any birder will tell you that spring and autumn migration seasons always bring with them a great deal of hope and promise for what may come to their local patch. Weather systems are watched, wind speeds and directions analysed, and habitats are regularly searched for any surprises that may be lurking

on one’s doorstep. On St Kilda, as with much of the western seaboard of the British Isles, there is always the chance of a Nearctic (American) vagrant being blown over the Atlantic, particularly when hurricanes disorientate birds on their otherwise typical migration routes.

The number of migrant species that have been recorded on St Kilda is relatively low in comparison to Shetland, Orkney and counties down the east coast of Scotland. In these northeastern and easternmost regions, common, scarce and rare migrants from European and Asian countries to the east make landfall every year. St Kilda, however, sits so far out in the Atlantic to the west of mainland Scotland that species from the east are much rarer, and instead it is migrant species from the north and west that are the norm, especially from Iceland and Greenland. For example, species such as Pink-footed Goose, Barnacle Goose, Whooper Swan and the Icelandic subspecies of Redwing (Turdus iliacus coburni) commonly occur on passage and in some years pass through in relatively large numbers.

P.V. HARVEY

It had been a tough early autumn for me and my regular autumn birding companion, Roger Riddington. Despite many long days in the field, we had little to show for our efforts: an adult White-tailed Eagle and a couple of Little Buntings were the best of pretty meagre pickings. Roger’s stepson, Rory Tallack, had managed to get a day off on 3 October, however, which meant only one thing - we’d be heading out west! Rory has long maintained his enthusiasm for the generally unfancied west Mainland and, with a hatful of finds under his belt, topped off by a Black-billed Cuckoo in September 2017, it was difficult to argue with him. The other great advantage with heading west is that you avoid at least some of the droves of birders that now visit Shetland annually between mid-September and midOctober. We were also accompanied by Dan Pointon who, for reasons unclear to me, I seem to have inherited as a regular house guest for several weeks every autumn.

On a generally fine day, with light SW winds and variable cloud, our first port of call was the Dale of Walls, where a couple of Yellowbrowed Warblers were the pick of a notably sparse handful of migrants present - not the most auspicious start to the day. Then it was on to Sandness. We passed Transition Turriefield en route, a community-based project focused on promoting local food production, which Rory had suggested we visit later in the day. Its mix of vegetable plots, willow hedges and scrub, and plots of Phacelia certainly looked like it would be attractive to migrants. Melby, Norby and Bousta between them provided a further six Yellow-browed Warblers but little else to get the juices flowing and so we arrived at Turriefield soon after 14:00 hrs.

We decided to walk around the area clockwise, which yielded another three Yellow-browed Warblers, and then, upon reaching the far side, we split up. Roger and Rory went further on, to

Plate 99. On 16 November 2024, while I was scanning the surrounding area at RSPB Lochwinnoch Reserve, Clyde, with my binoculars, I spotted a Grey Heron. Herons are common in this area, but what caught my eye was that this bird was wading out into deep water!

As the heron was continuing to move out in to even deeper water - this is not their normal behaviour - I decided that I had better start getting my camera prepared. Then, while it stood motionless, having a ‘deep soak’, I managed to take this shot before it proceeded to wade back to the shore and indulge in a serious preening session. I was quite pleased to capture such an unusual Grey Heron photograph that day.

John Stevenson, Houston, Renfrewshire. Email: ziggysteve777@gmail.com

Equipment used: Canon EOS R7 camera, Canon RF 100–500mm F4.5–7.1 IS USM lens, Manual, 1/800 second, ISO 2,000. f6.3.

Featuring the best images posted on the SOC website each quarter, PhotoSpot will present stunning portraits as well as record shots of something interesting, accompanied by the story behind the photograph and the equipment used. Upload your photos now - it’s open to all.