WINTER 2019

KOREAN CULTURE & ARTS

SPECIAL FEATURE

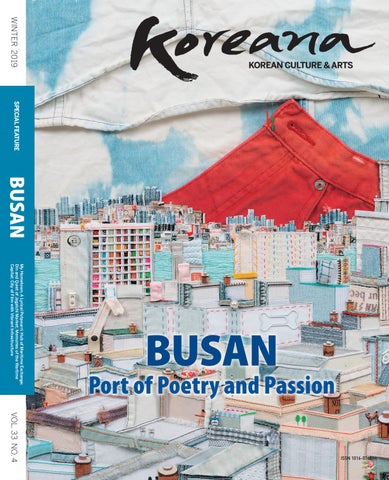

BUSAN

Port of Poetry and Passion My Hometown, A Lyrical Potpourri; Hub of Maritime Exchange; Din and Quiet of Jagalchi Market; Memories of the Wartime Capital; City of Film with Vibrant Infrastructure

BUSAN

VOL. 33 NO. 4

ISSN 1016-0744