…elevating and reimagining Seattle’s web of shorelines and waterways as interconnected landscapes where human experience and ecological enhancement thrive

SUMMER INTERNSHIP 2023 BERGER PARTNERSHIP

Lily Daniels, Intern with Belle Miller and Guy Michaelsen

Lily Daniels, Intern with Belle Miller and Guy Michaelsen

…elevating and reimagining Seattle’s web of shorelines and waterways as interconnected landscapes where human experience and ecological enhancement thrive

SUMMER INTERNSHIP 2023 BERGER PARTNERSHIP

Lily Daniels, Intern with Belle Miller and Guy Michaelsen© Copyright 2023

Berger Partnership Cover Art: Belle Miller

I grew up on Lake Washington spending every summer on the water with my family. We were lucky; we had a boat and a family that seized every opportunity to experience the waterways that define our region. From sailboat races on Thursday nights to afternoon picnics on the arboretum’s shores ... we lived on the water! What burns in my mind is the feeling of freedom it fostered, a feeling shared by all creatures that live on the water. It is a fundamental part of our existence, a piece of nature that lives in all beings, and something that should never be withheld or restricted.

Access to water is a human right. It is an essential part of our nature, our bodies, and our world.

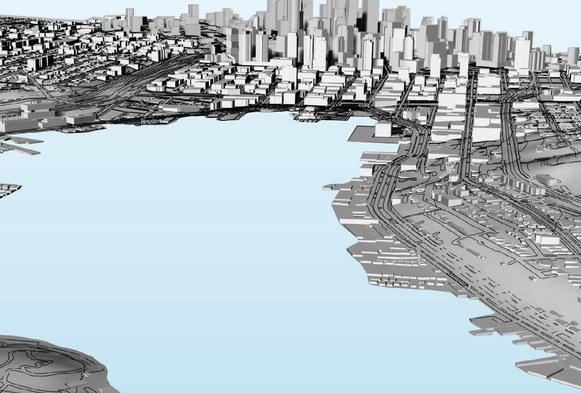

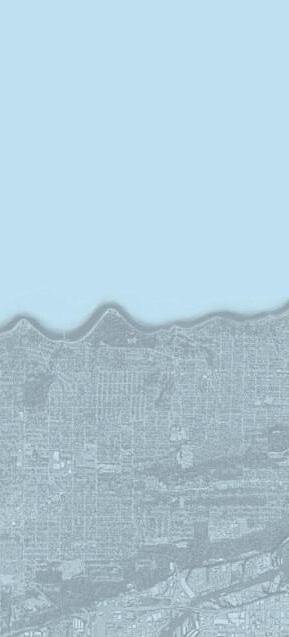

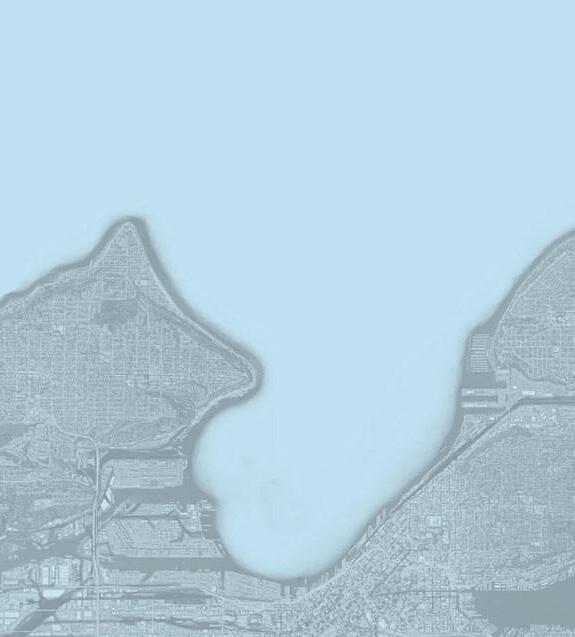

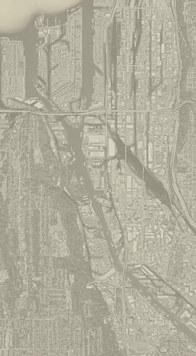

Seattle is blessed with an interwoven web of waterways, lakes, rivers, canals, and Puget Sound, sometimes a barrier, sometimes a connection, and always shaping the experience and soul of our city.

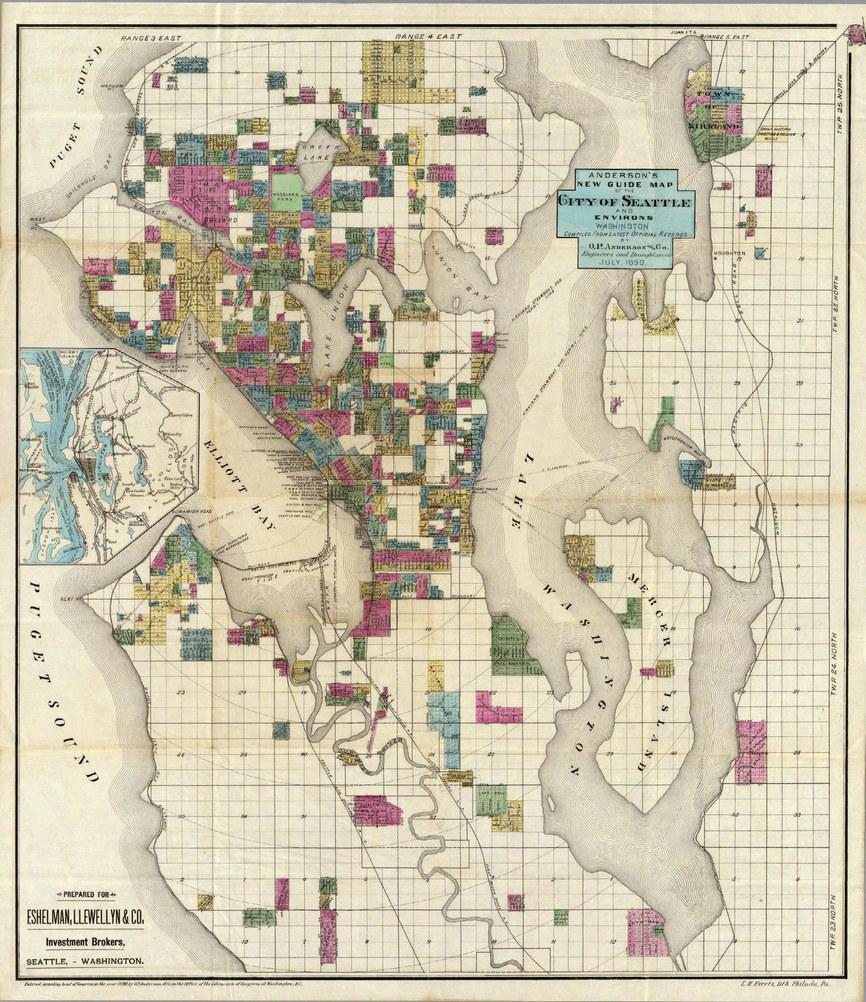

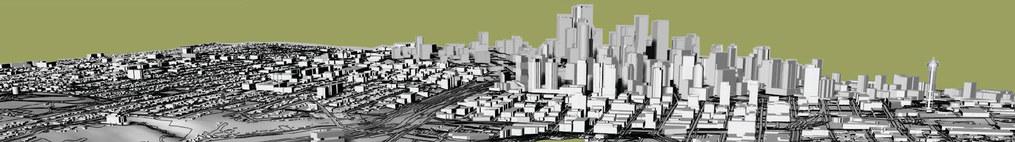

Over this web of water and the hills that shape it is a rectilinear street grid that stretches across the whole city, a human attempt to organize and impose structure on glacially shaped landscape.

Where our city meets the water is where the street ends and something entirely new begins … a place of alchemy where a series of unplanned, leftover spaces—relics of the collision between engineering, planning and geography— can be seized and reimagined. Interconnected shorelines where human experience and ecological enhancement can thrive together.

Inspired by a love of water and shorelines, this is a study of one of Seattle’s under-realized assets: its shoreline street ends, how they came to be, what they are today, and imagining what could be!

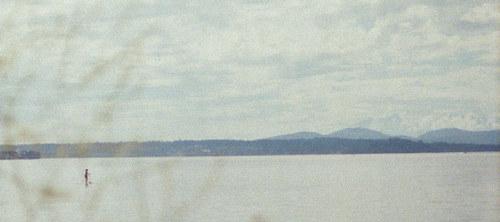

99.99% of the images in this book are taken this summer, on 35mm film, with my mom’s old Olympus OM-10. I wanted to tell this story raw, unfiltered, and unedited. Some of the photos came out grainy, blown-out, blurry, double exposed, or just unremarkable. They still found a place in this story. This imperfect and in-themoment quality is meant to be representative of the project itself. We’re just spitballing here; we don’t have all the answers. I took a lot of photos, but I couldn’t take thousands of redos or do-overs. This means that you may need to fill in the blanks to totally see some of the places. I guess it just leaves more to the imagination.

There are a couple of photos that capture absolute magic, a Seattle summer in full bloom, a love letter from me to my city.

ifyou fndyourselfgazingouttothe sound on a thursday evening , keepaneyeoutforthe weekly sailing regatta.

acrossthewaterastheydash throughthechoppywaves ... inthedistanceaferry boat or two catchesyour eye , ch u ggi n g along on asitcarries passengerstoandfro

01 water is a place

The water’s edge is a place of alchemy, the threshold between land and crossing over into another element. This emergent edge is mesmerizing: it evokes freedom, the edge of one world, the start of a new one, and provides a sense of timelessness. Land changes yet somehow water remains the same. Water is magnetic. We love the shoreline, its predictability and unpredictability. We love to stare at the horizon and take in something so much bigger than ourselves. We love to feel part of something so deep, so expansive, and so unknown. Water is all around us. It is what we are made of and where we came from.

Water holds a deep significance, intertwined with the essence of life itself. Humans have sought water throughout history to sustain their existence and quench their thirst. Beyond its practical necessity, water carries profound symbolic value, reminding us of our vulnerability and reliance on nature’s delicate balance. It represents purity, renewal, and cleansing—a universal source of life and vitality. The touch of water on our skin becomes a symbol of serenity and purification, infusing our lives with meaning and purpose. From ancient nomadic pursuits to modern appreciation, water is a testament to our interconnectedness with the natural world, weaving through the tapestry of our existence.

Whether it’s the sight of cascading waterfalls or the gentle ripples on a calm lake, water has the power to add vibrancy and excitement to its surroundings. Still water acts as a reflective surface, mirroring the beauty of the surrounding landscape and evoking a sense of serenity and depth within us. The soothing sound of water, whether it’s the rhythmic lapping of waves or the gentle trickling of a stream, can create a deep sense of relaxation and rejuvenation, nourishing our souls and providing a respite from the busyness of daily life.

Water is undeniably cathartic, providing a tranquil escape from the demands of the world. Whether diving into its depths or peacefully floating on its surface, we experience a profound sense of liberation and release. This transformative power is symbolized by water’s touch, which has long represented serenity in religious contexts. It purifies our souls, infusing us with newfound life, purpose, and meaning. Connecting with water allows us to renew ourselves, fostering a deeper bond with nature and leaving us refreshed and revitalized.

Water is essential for the continuity of life on Earth. It sustains all living beings and ecosystems, serving as a vital resource for hydration, growth, and reproduction. The availability of water directly impacts the survival and flourishing of organisms, including humans. It is the basis of various ecological processes, such as nutrient cycling and photosynthesis. Without water, life as we know it would not be possible.

We feel the power of water yet struggle to understand what we are feeling. We often see water as an obstruction, a void, looking across and focusing at what lies beyond—what the water is separating us FROM. Yet the power we feel standing at the water’s edge is not the boundary or void—what we feel is the presence of the water itself, connecting us to places both seen and beyond. It is a spirited, living, dynamic element that constantly evolves. It should not exist outside of our consideration as designers or as earth inhabitants. It should be considered for the powerful presence it holds in the world. Water is a link. Water is a place!

class departs onalatewednesdayafternoonfromthenotoriousagua

verde paddle club,knownfortheirloveofseattle

water sports anda sweet and saltyhappy hour margarita ... graba takeout burrito and sitbackatsakuma

viewpointto enjoythevibrantscene...

On a landscape shaped by glaciers, the hydrology of today’s Pacific Northwest is a diverse and remarkable system. Glaciers and snowfields in the Cascade and Olympic Mountains are vital for water supply, slowly melting and feeding rivers like the Columbia, Snake, and Willamette. Closer to Seattle, rain and groundwater feed the Duwamish, Cedar, and Sammamish. These rivers support wildlife, agriculture, hydropower, and recreation.

Along their paths, heavily altered and shaped by humans, they encounter lakes of all sizes, providing serene reservoirs and habitats. Together, these elements form a remarkable hydrological tapestry that sustains the ecosystem, enriches lives in the Pacific Northwest, and powers the waters that are central to Seattle’s identity.

Renowned for its mild weather and abundant access to fresh water, Seattle experiences a temperate maritime climate, characterized by cool, wet winters and mild, pleasant summers.

Rainfall is a defining aspect, with average annual precipitation ranging around 37 inches. However, recent climate change projections indicate potential shifts in precipitation patterns, including more intense rain events and increased variability.

Trail. These destinations mark the beginning of Seattle’s reclamation of its waterfront for public access and experience

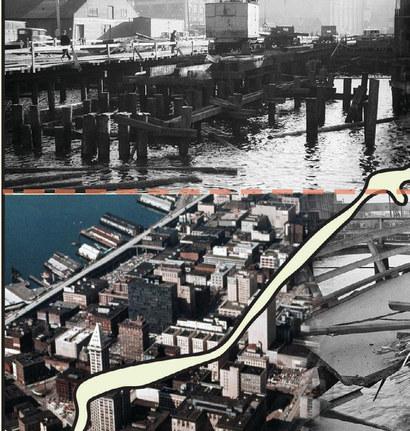

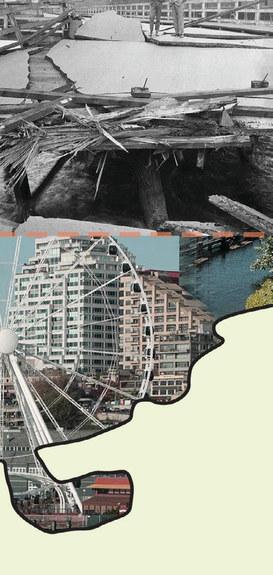

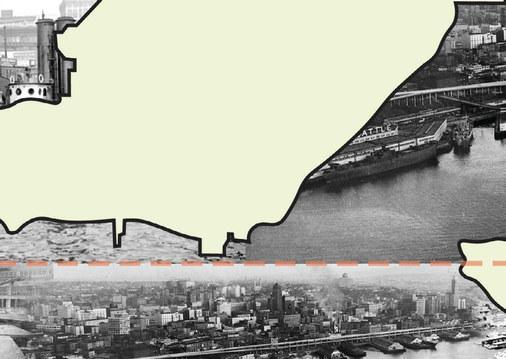

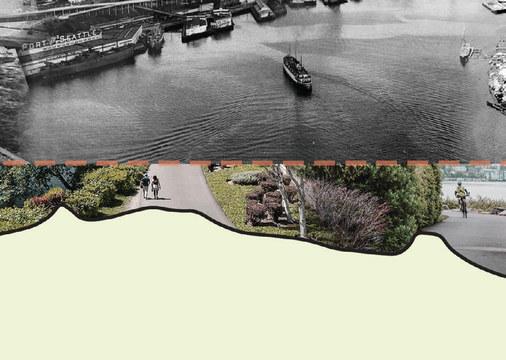

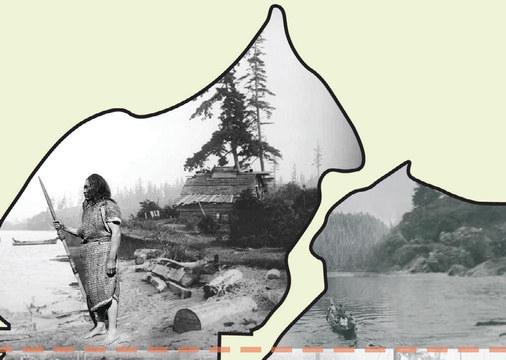

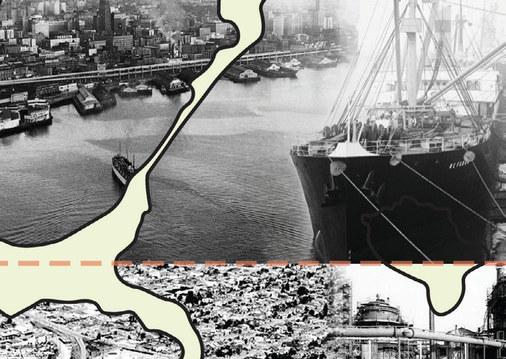

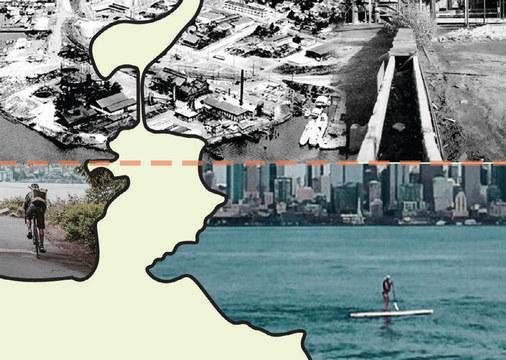

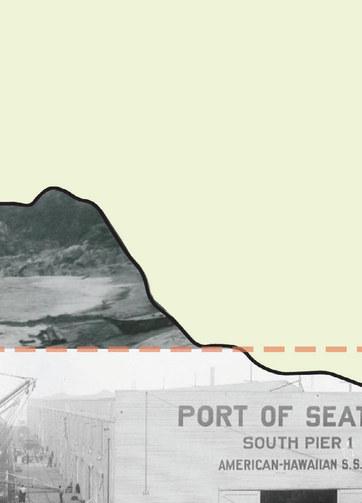

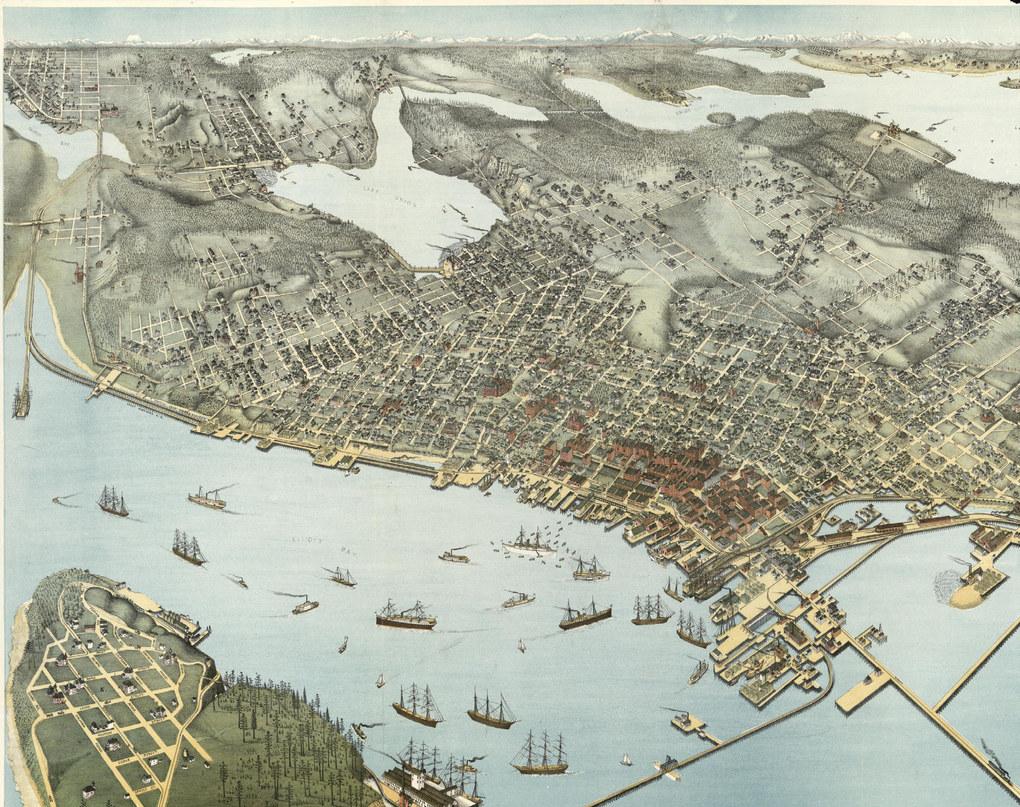

Progression from time immemorial to modern day has influenced Seattle’s dynamic shoreline environments. From the steward culture of the Coast Salish tribes of Puget Sound to the rise of shipbuilders and industrial economies, water has always shaped the city’s identity. As the waterfront industry declined, remnants of abandoned factories and rail lines emerged, leaving fallow landscapes that gave rise to notable civic treasures like Gas Works Park and the Burke-Gilman Trail. These destinations mark the beginning of Seattle’s reclamation of its waterfront for public access and experience and a renewed focus on ecology.

When Seattle was developing they promised property owners individual plats. These parcels sometimes extended directly into the water. This means that the property owner held rights not just over the land, but the beaches, tidal flats, and emergent zones extending from the waterways.

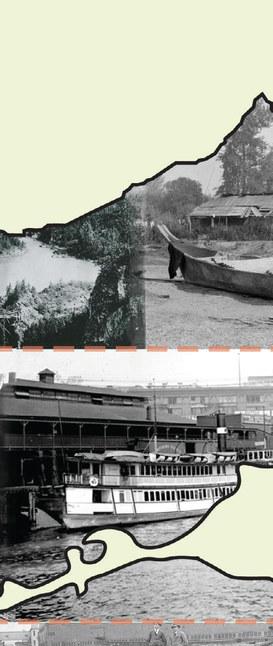

Seattle’s web of water has long connected the city to the world, region, and the surrounding Puget Sound area. A once bustling, steampowered “mosquito fleet” of ferries carried passengers around the sound, with tiny boats connecting to the shorelines of early Seattle, providing passengers with a sense of community.

As the area became increasingly industrialized, the mosquito fleet slowly lost its business to planes, trains, automobiles, and the Washington State Ferries. Through this evolution, intimacy was lost between our shorelines and the bodies of water that still connect Seattle.

Imagine how expansive yet connected our region would feel if we complemented our land-based streets with a renewed network of water-based connections!

A historic birds-eye view of Seattle created in 1891, just after the Great Seattle Fire of 1889 reshaped our city, shows the bustling waterfront economy of Seattle at the turn of the century. Detailed illustrations show buildings, railways, waterfront piers, and ships sailing around the sound and world. The focus on Seattle’s abundant waterfront access was evident. Life on the water carried a different tune in past centuries, but our waterfront is no less important to Seattleites today ... how can we strengthen our city’s soul by forging a stronger connection between land and water?

Today, Seattle’s waterways have become a thriving hub for both industry and recreation. Residents eagerly embrace activities like kayaking, paddle boarding, and sailing, seeking any excuse to get out on the water. With picturesque landscapes and a focus on health and wellness, water-based activities provide a break from urban life.

There is a renewed emphasis on shoreline ecologies and the health of our waterways. Improved waterfront infrastructure and access points have made it easier for people to enjoy the water, with enthusiasm for water recreation expected to continue growing.

70% of shorelines in the Puget Sound region are privately owned

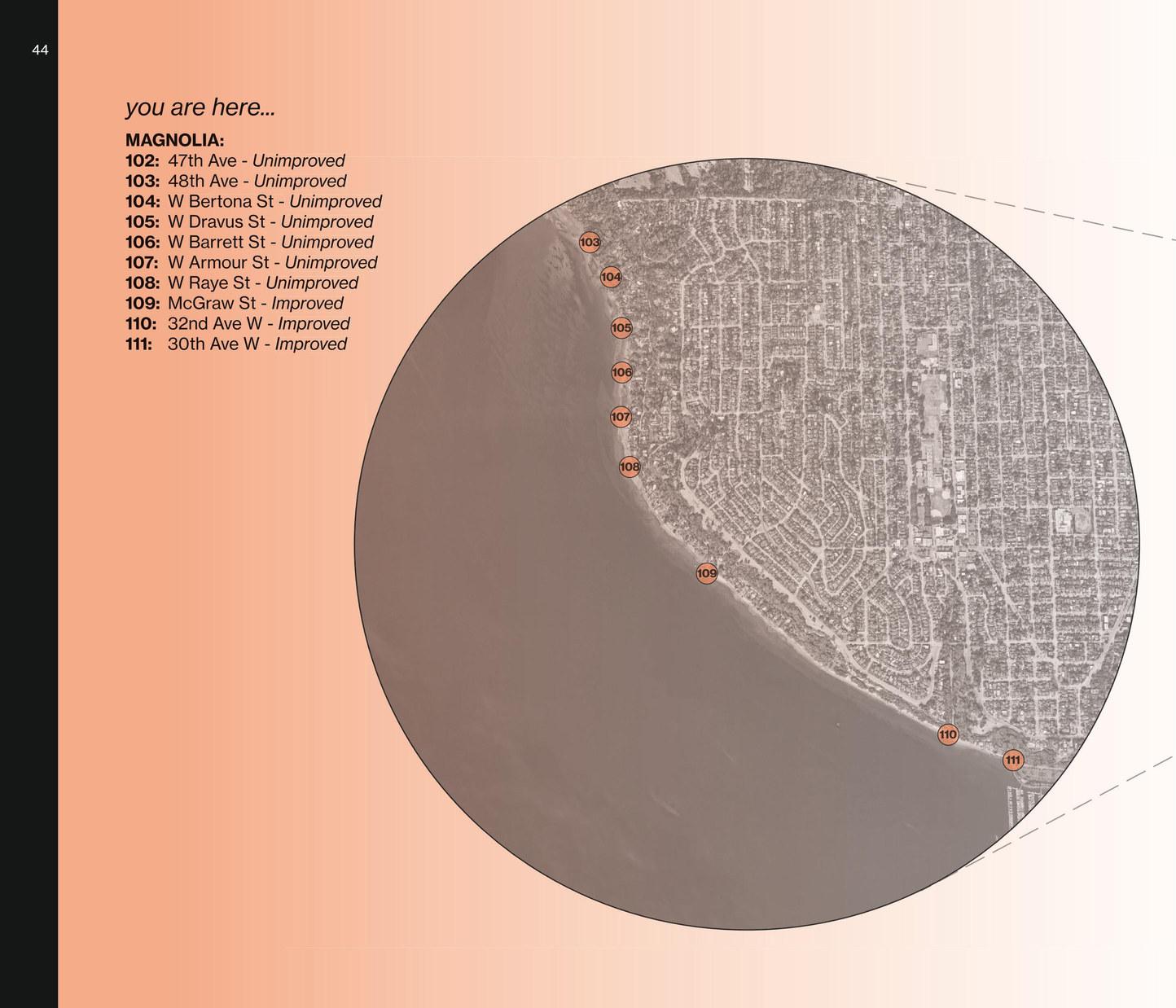

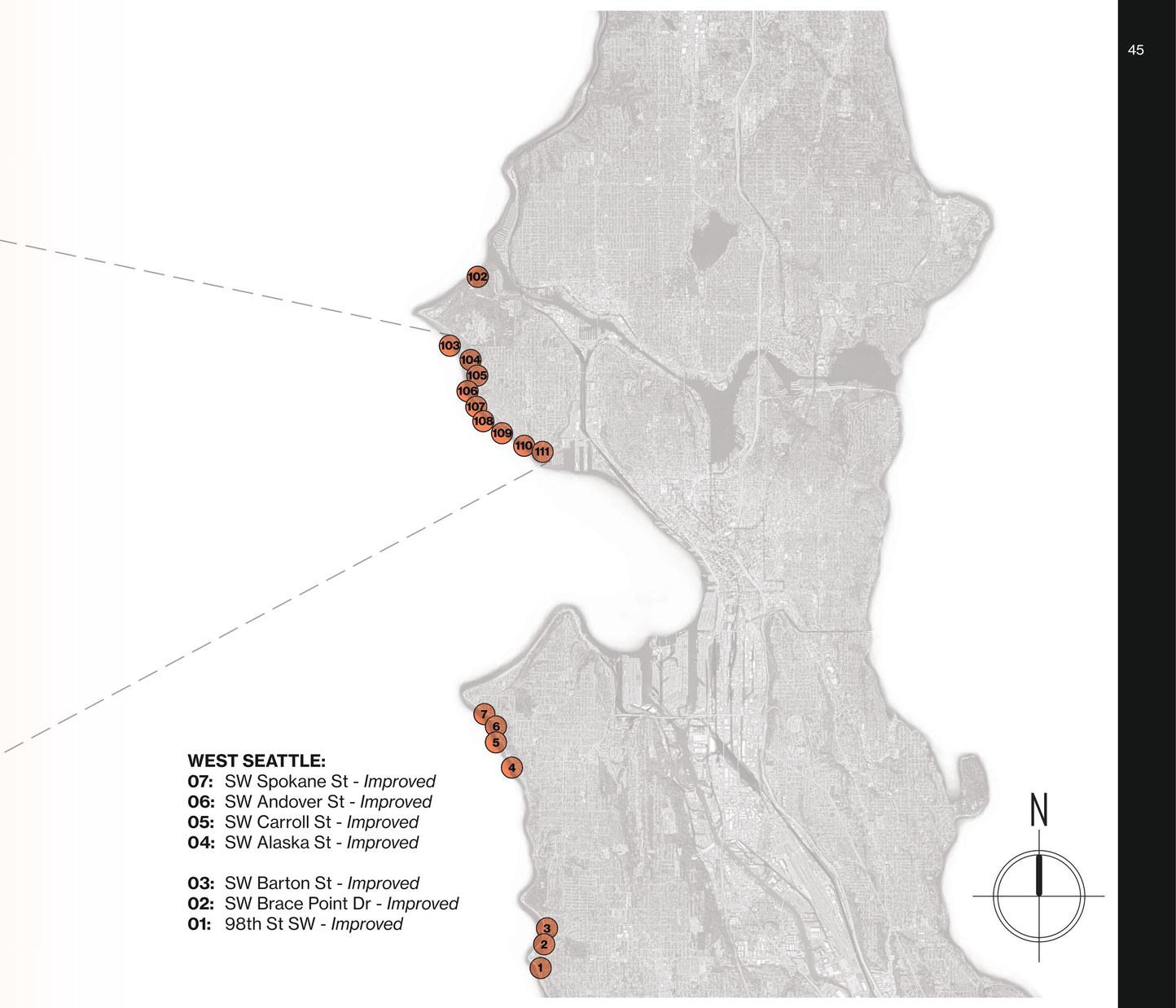

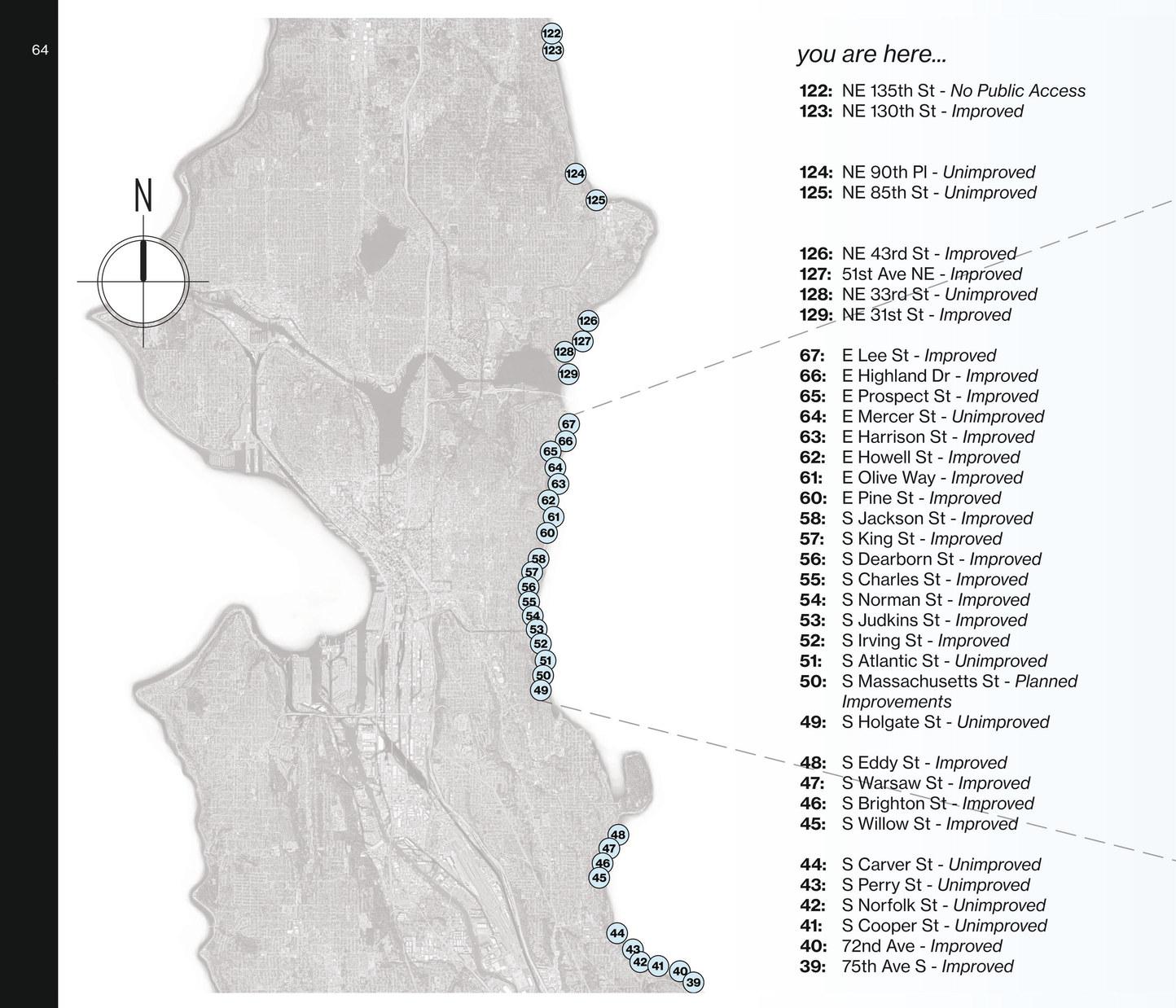

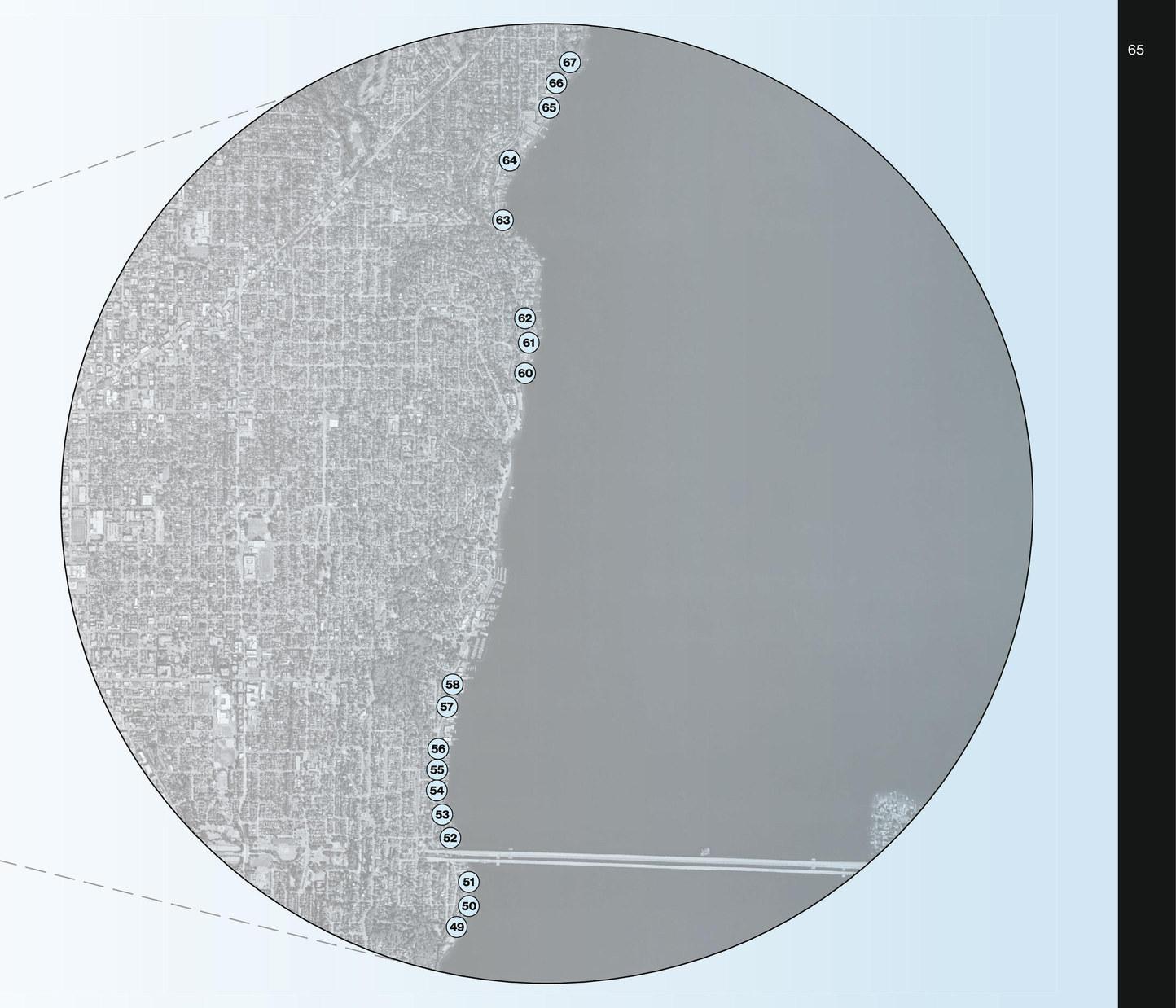

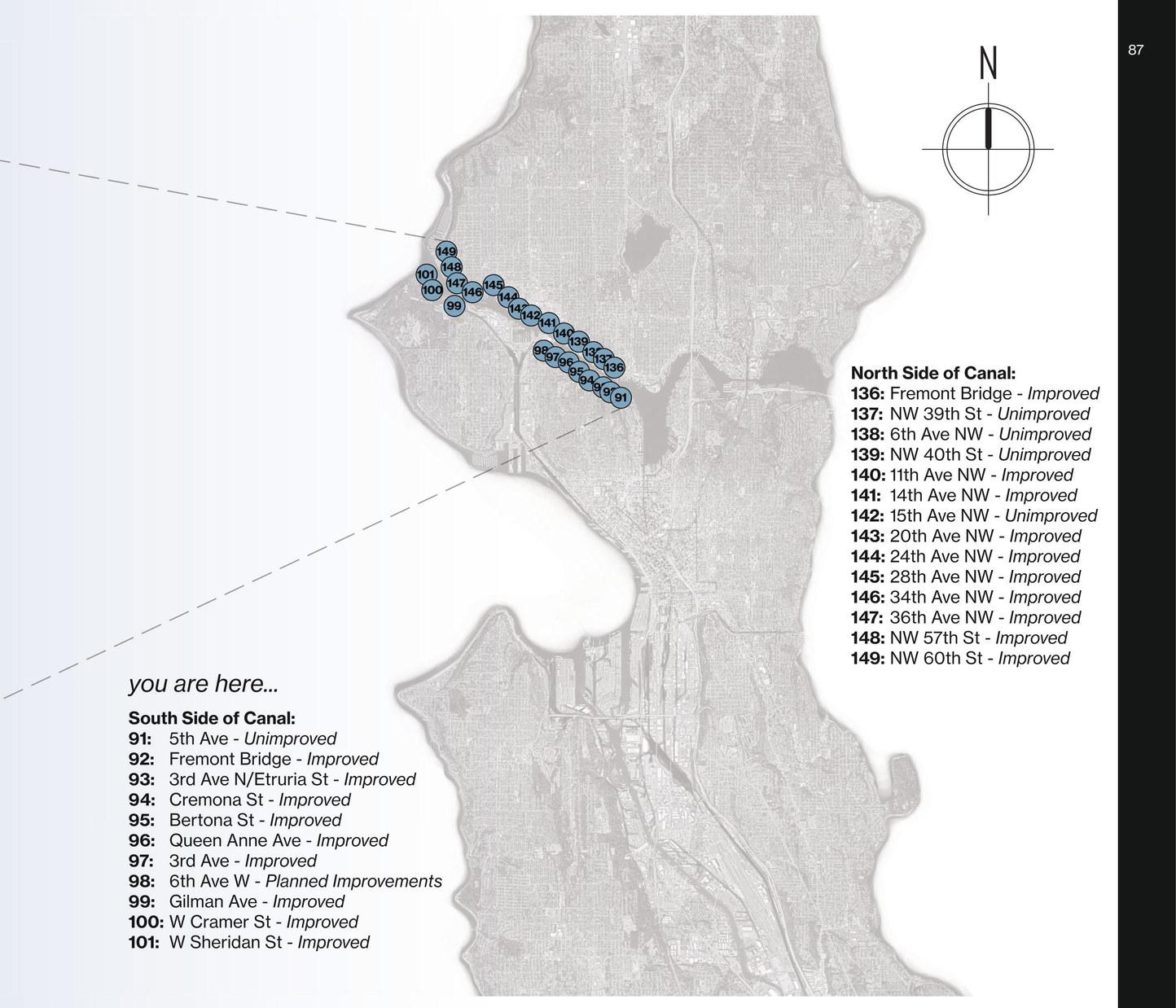

142 street ends were reclaimed for public use and enjoyment

Each one tells a different story of Seattle’s cultural and environmental history

water is a place • water is a link

Due to the platting of the public tideland, 70% of the Puget Sound region shorelines were privately owned by 1971. This disparity means that our public shorelands in Seattle are precious assets to be protected and enhanced.

Seattle is bordered by water in every direction. While there are several notable parks adjacent to the water, there are still significant gaps in waterfront parkland.

A community-led effort in the 1990s advocated for increased public shoreline access. The first four improved street ends, originally known as Seattle’s string of pearls, were the catalyst in the legislature turning over the public right of way. By 1996, the City Council approved Resolution 29370, designating shoreline street ends for “public use and enjoyment.” Following this resolution was Ordinance 119673 that codified specific permit fees to discourage private encroachment of public shoreline street ends. This revenue is used to provide maintenance and improvement of shoreline street ends.

The idea is that the street ends are these moments of respite scattered about the city, providing a break from noise, traffic, crowds, and hecticness. They are precious; they are special. John Barber, cofounder of Friends of Seattle Street Ends, the organization we should all be thanking for the advent of the street end program, calls himself a “SLOW LIFE ACTIVIST.” He’s out there with Marty Oppenheimer, Karen Daubert, and a whole bunch of other passionate Seattleites protecting our right to sit on a bench and take in the view.

Since street ends must exist in the right of way, they are inherently small, only averaging about 60-feet wide. This creates a unique park experience, one of privacy and ownership. Marty acknowledges this special identity.

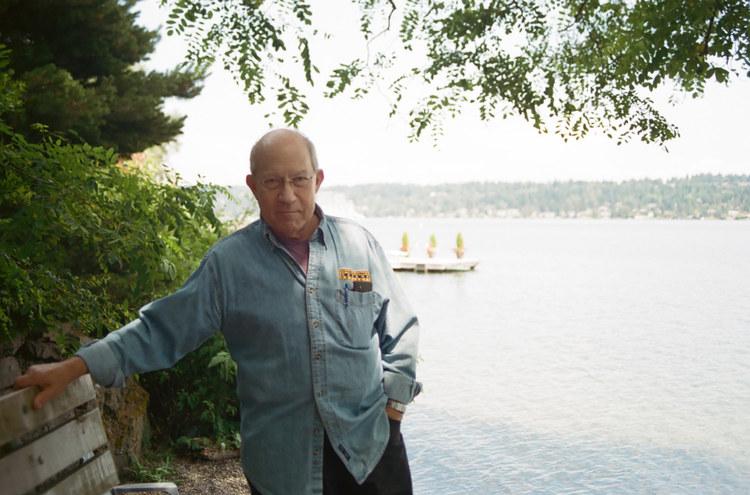

Marty Oppenheimer (left) is one of the leading members of Friends of Seattle Street Ends. He is pictured here at “his” street end. Marty, with support of his family and friends at FOSE, has been fighting for right-of-way rights at street ends for nearly 30 years.

“It’s interesting. They come and they look down there to see if there’s anybody there, and if there’s somebody there, they usually leave. Or they go down and join them, you know. But they keep it that it’s theirs. You know, they realize it’s a private space, that they don’t want to intrude on other people’s time.”

“slow life activism”

“street end robin hood”

Today, Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), along with Friends of Seattle Street Ends (FOSE), work together with various partners to maintain and improve shoreline street ends around Seattle. Due to neighboring encroachments, constant work must be done to continue to operate and maintain street ends in Seattle.

Currently, SDOT is working on a new director’s rule that will help the department manage the street ends more efficiently. This will mean less turf wars with neighboring property owners and more effort spent maintaining and improving street ends.

Beyond the politics of the street ends, there is also the task of maintaining 142 water-adjacent public right-of-ways. They require constant upkeep to maintain the native landscaping and keep out invasive species such as Himalayan Blackberry, Laurel, and English Ivy.

Pictured to the left is Omar Akkari, head of the street end oversight at SDOT, with intern Meridith Grupe, a student of landscape architecture at the University of Washington. With limited resources available at SDOT, part of the job description is to get your hands dirty every once in a while.

Omar is a dedicated civil servant, and along with maintaining the existing street ends, he works to create new ones. He is planning on adding 25 new street ends in coming years, with 10 new improvements coming soon. Think of him as the robin hood of street ends, taking down the private fences to open up access to the greater Seattle community.

Between SDOT, FOSE, and the other various street end activists, there are many ways for you to care for a street end.

You can reach out to SDOT directly or go to the Friends of Street Ends website to find a calendar of upcoming events. Work parties happen all over the city with various neighborhood groups.

If there is a street end near and dear to your heart, opt to become a street end steward

You can coordinate with SDOT or FOSE to take on the role, and it can be as little as walking by once a month or as much as organizing a major renovation of the site.

These pocket parks belong to us, the community of Seattle, and it is our responsibility to care for them. They are a unique opportunity to give us all a piece of the waterfront, to make memories, and to enjoy the view.

you, maybe??

... memories dance on the water

’ssurface,reflectingatapestryofdreams

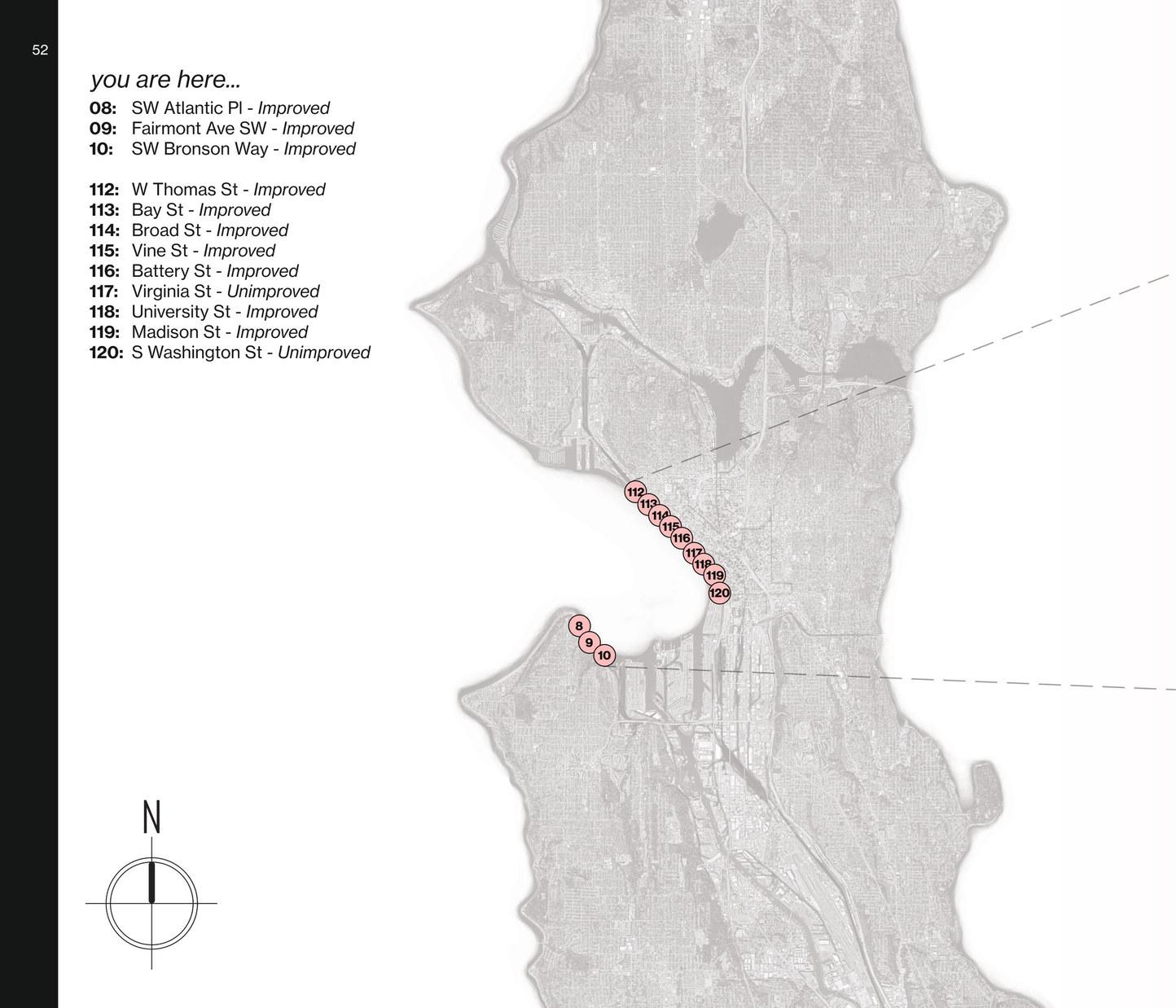

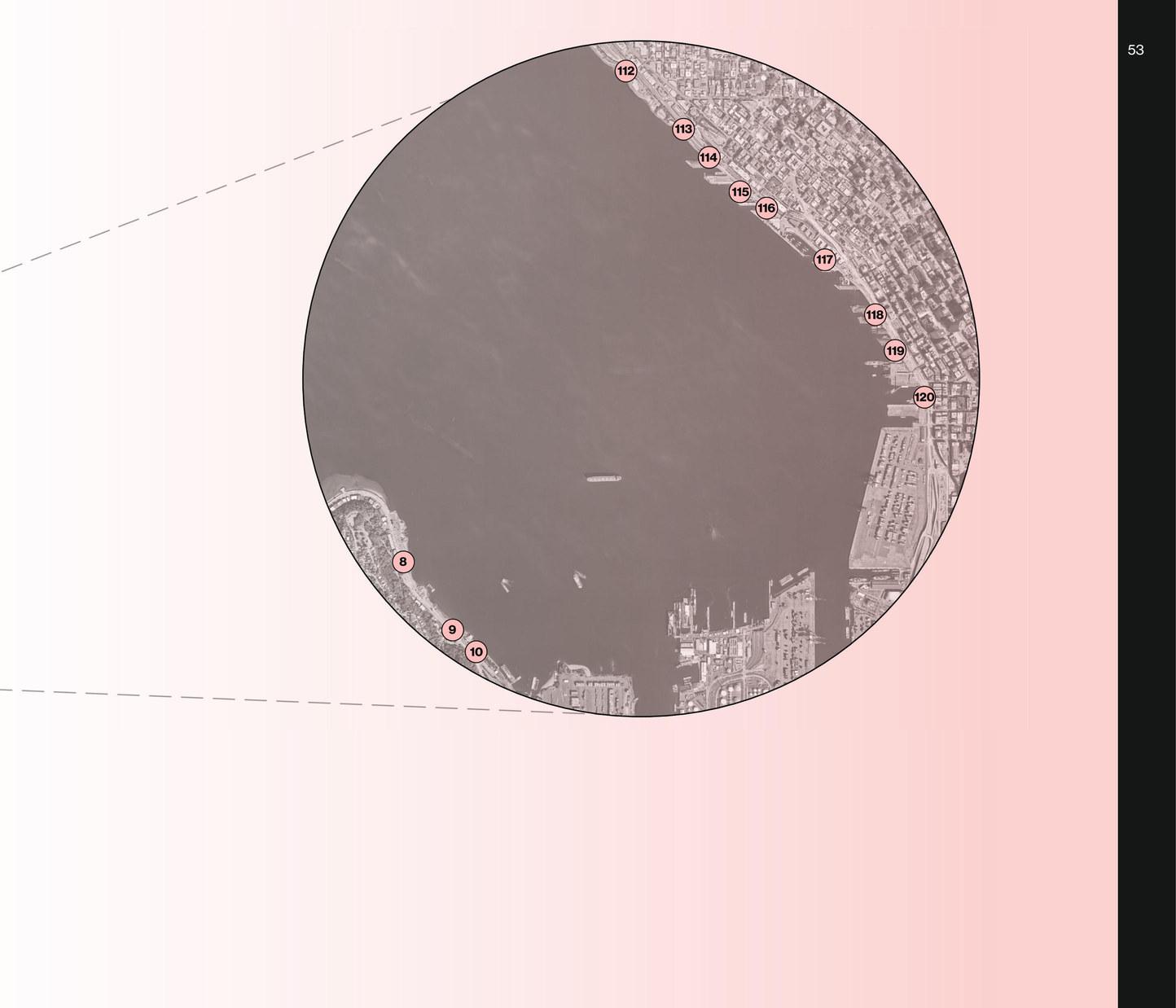

03 you are here... and daysgoneby ,

golden strand s through t h e r u s t ed r el i c s of i nd ust r y , a s ymphony of nature

Seattle, with its diverse topography and geographical features, boasts a plethora of waterbodies. From the grand expanse of Puget Sound, hugging the western boundary, to the serene waters of Lake Washington, stretching along the east, each body of water lends its character to the city’s charm.

The lively Lake Union, nestled in the heart of the city, fosters a vibrant urban atmosphere, acting as Seattle’s Central Park, while the calm waters of Union Bay offer a tranquil oasis. Further south, the industrial landscapes alongside the Duwamish River tell a story of Seattle’s maritime heritage.

These varied bodies of water intertwine with Seattle’s neighborhoods, shaping unique microregions that cater to diverse lifestyles and interests, making the Emerald City an enchanting mosaic of water and land.

The intertidal zone along the shores of Puget Sound teems with life. People are drawn to the sandy beaches adorned with shells and driftwood while shore birds frequent these locations, seeking sustenance from the abundant fish population. Such a locale brims with untapped potential, offering ample opportunities for activation and exploration.

At the bottom of the hill at West Magnolia Viewpoint lies West McGraw Street. Descending a rickety old staircase, you come upon a quiet alley with a handful of beach bungalows facing the sound. The winding road opens up to a hidden gem—the panoramic viewpoint at West McGraw Street, SSE #109. An expansive beach is awaiting discovery. From here you can walk for miles, taking in views of Mt. Rainier, Bainbridge Island, Ferry Boats, and the Olympic Mountains. The red peeling bark of Pacific madrone trees creates a tapestry of hues, while the delicate petals of California poppies add vibrant pops of color against the muted tones of sand and stone. Wild and untamed blackberry thickets claim the underbrush, providing visitors with sweet sun-soaked berries in the August afternoon. This space is still untamed by people, existing just as it is, a subtle testament to the unpredictable nature of the environment.

The tranquil and quiet beach embraces visitors with a peaceful ambiance. Whether you’re here to catch the sun’s final glimmer as it sinks below the horizon or to embark on a kayaking adventure along the protective reef, SSE #109 offers a sanctuary of quietude amidst the bustling Seattle streets. If you are the type to seek solace in nature’s company, come to the street end where the rhythmic lull of waves harmonizes with the wind’s gentle breeze. The dynamic coastal flora offers solitude along the beauty of the sound, a place to momentarily escape the urban pulse and find a connection to the natural world around Seattle.

Known to local West Seattleites as Weather Watch Park, this street end stands as one of the neighborhood’s most charming hidden gems. Situated along Beach Drive SW, this pocket-sized waterfront park offers an unobstructed view of Puget Sound, enhanced by its close proximity to the renowned La Rustica restaurant. Notably, this park holds historical significance, once being the site of a pier where the Eagle steamboat docked, connecting passengers to downtown Seattle until 1920.

This space used to serve as a bustling meeting point for the community, creating a vibrant town square atmosphere. After seven decades of dormancy following the pier’s removal, the area was transformed into the inviting park it is today, adorned with engaging artwork and educational displays focused on weather observation.

With a weather vane and sundial perched in its landscape, the park invites visitors to immerse themselves in the art and science of meteorology. Its sweeping western vista provides a panoramic view of Puget Sound and the majestic Olympic Mountains, making it an ideal spot for cloud watching and experiencing the natural beauty of the Northwest skies.

Perched upon the pebble-strewn beach, visitors can embrace their inner meteorologist, gazing skyward at a canvas of cloud formations, from billowing cumulus towers to saucer-shaped lenticular clouds, evoking a sense of wonder akin to that of a curious child.

Way out at West Seattle’s tip, Constellation Park is a beloved local pocket park, celebrated for its role as an artful guide to Seattle’s prime stargazing spots along the avenue of stars. Bronze plaques embedded in the sidewalk create a constellation tour, leading visitors to discover the city’s best night sky observation points. From the sandy beach extending to the historic Alki Point Lighthouse, panoramic views of Puget Sound unfold, complemented by scattered driftwood.

The park also prompts environmental awareness, with an adjacent pump station reminding locals of water’s journey and sewage pollution’s impact, while low tide reveals captivating tide pools along the intertidal shore, showcasing its ecological significance as a haven of biodiversity, making the journey to this coastal haven a truly enriching experience.

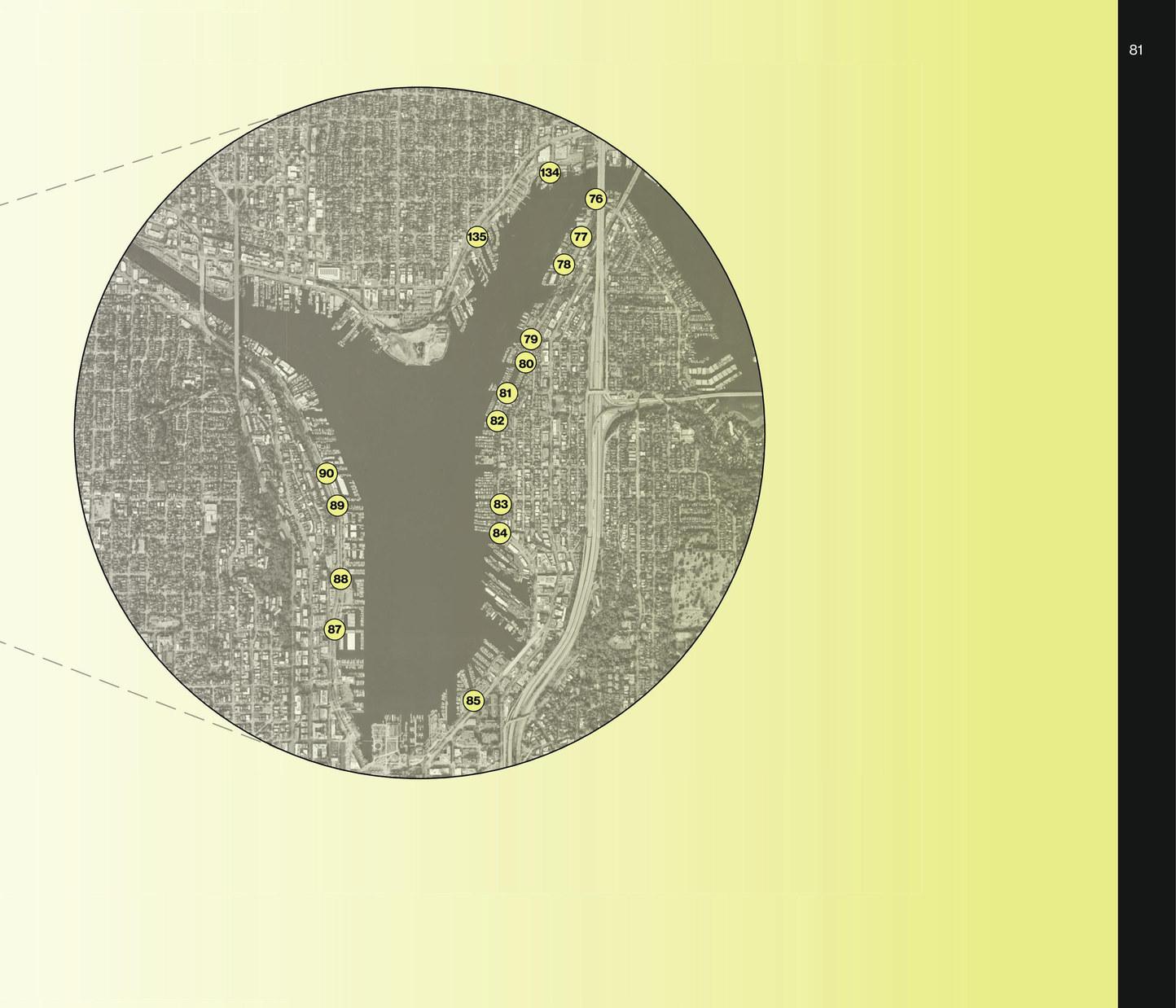

Wrapping around Seattle’s urban center, the street ends along Elliott Bay hold unique potential to bring open water access to the city. Downtown Seattle is notorious for its exciting events and displays of art. Elliott Bay is an exemplary showcase of this with its famous Olympic Sculpture Park and nearby Seattle Center. Street ends are strewn about this region with plenty of pocket parks to enjoy the view.

Imagine a warm summer day on Elliott Bay, the sun painting the waters with golden hues. Perhaps you found yourself drawn downtown, whether for a waterfront event or a leisurely stroll around the Olympic Sculpture Park. As you arrive at Bay Street End, a seamless fusion between urban pulse and tranquil waters unfolds. This site, one of the select few street ends gracing Seattle’s official waterfront, emanates an energy that mirrors the city’s vibrant heartbeat. The area hums with activity, an embodiment of bustling life, as if it were the epicenter of the universe itself.

Yet beneath the layers of modern vitality, a profound connection to Seattle’s indigenous history lies embedded. Bordering the sacred grounds known as the Little Crossing Over Place, the whispers of ancient villages that once thrived along this stretch of the sound still resonate. It’s as though the spiritual essence of these ancestral communities continues to linger, intertwining with the present.

Surrounded by a landscape of unparalleled grandeur, Bay Street becomes a bridge between worlds. The meticulously curated Olympic Sculpture Park stands as a testament to human creativity, offering a backdrop that juxtaposes urban artistry against the timeless expanse of the sea. As you turn to face the shoreline, a hidden alcove emerges—the Myrtle Edwards Park beach, an enchanting sanctuary that evokes a sense of discovery.

In this juxtaposition of urban sophistication and natural splendor, Bay Street stands as a portal to a realm where cityscapes and seascapes harmonize in breathtaking unity. Amidst the charm of the city and the majesty of the sound, Bay Street captures the essence of a perfect day, where the ordinary transforms into the extraordinary, and you find yourself exactly where you’re meant to be.

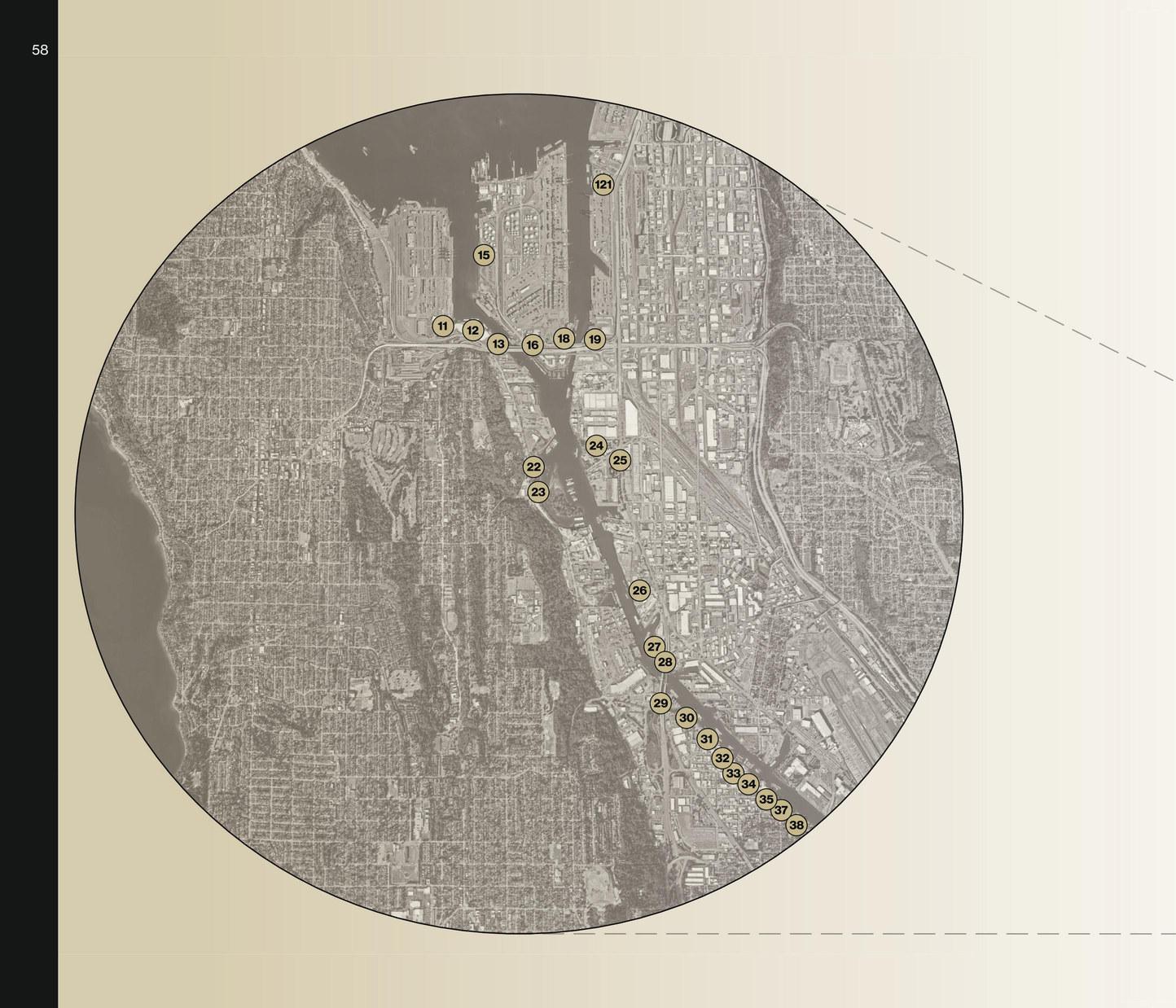

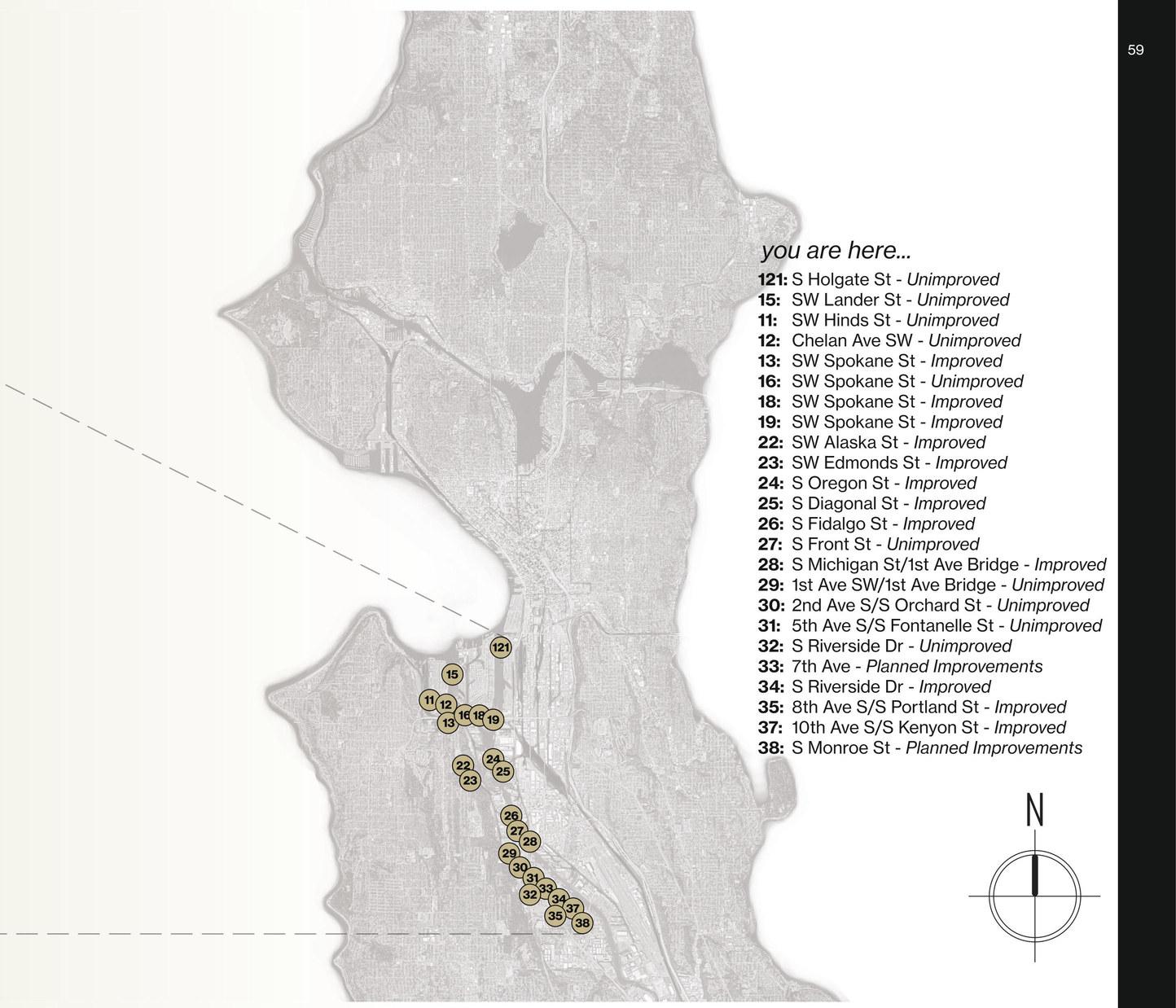

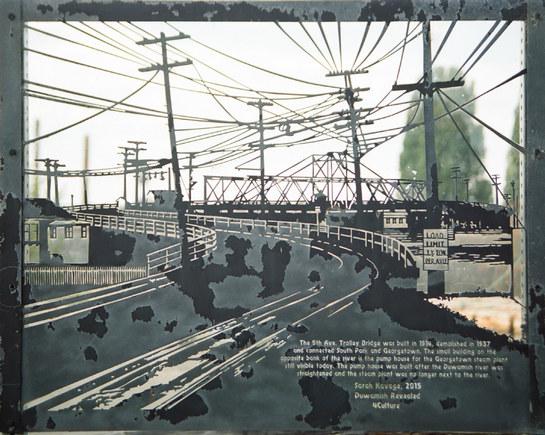

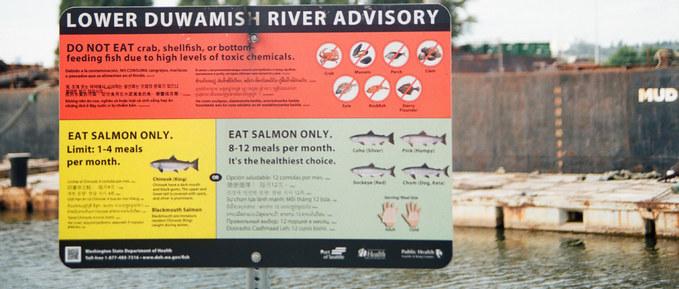

The Duwamish River is simultaneously well known and easily forgotten in the scope of Seattle waterways. Rich in industrial history, the Duwamish River has seen many different eras of Seattle’s culture. The river is essential to the Duwamish Tribe and other indigenous people of the area. Still an industrial hub, many of the street ends along the Duwamish are occupied by encroaching businesses along the river.

Located at the edge of South Michigan Street along the banks of the Duwamish River, this street end park offers a peaceful retreat amidst the urban landscape. This hidden gem provides a unique vantage point to observe the rhythmic flow of the river and the interplay between industry and nature. With views of passing barges and waterfront activity, the park captures the essence of Seattle’s maritime heritage. Its modest expanse invites locals and visitors to pause and reflect, offering a serene escape from the city’s hustle and bustle.

As an urban oasis, this street end park serves as a reminder of the delicate balance between progress and preservation, a place where the past meets the present in a tranquil harmony along the river’s edge.

Tałtałucid Park and Shoreline Habitat, also known as 8th Ave

South Park, carries a storied past as a former swing bridge site between South Park and Georgetown. Today, it provides a serene escape for local workers and residents amidst the bustling river traffic. Echoes of tribal fishers exercising treaty rights resonate alongside a thriving wildlife scene.

Once a waterway navigated by indigenous cedar canoes, the park’s land has witnessed Seattle’s evolution from its earliest settlement to industrial growth. The 1985 Comprehensive Public Access Plan marked a transformative moment, leading to its portguided restoration, completed in 2007, showcasing ecological stewardship through marsh habitats and lush greenery.

This park is more than a tranquil haven; it stands as a tribute to the enduring spirit of diverse communities and their commitment to preserving shared heritage and nature’s legacy.

Many street ends border Seattle’s Lake Washington. With panoramic views of the Cascade Range, Mt. Rainier, and Mt. Baker, Seattleites head to Lake Washington to see if “the mountain is out.” The street ends on the lake are the first of their kind, with decades of community activism behind every bench, stairway, and beach.

Tucked away on the serene shores of Lake Washington, the East Harrison shoreline street end, affectionately known as Hidden Beach, is a true gem among Seattle’s enchanting locales. This haven has embraced generations of the community—families, swimmers, strollers, and those seeking solace in nature’s embrace. A place where time stands still, where views and quiet moments intertwine to create cherished memories.

For years, this space has been tended to by an informal collective of caring souls. While a designated steward exists, the dedication of countless individuals is palpable as they selflessly remove debris, tidy paths, and contribute to the upkeep of Hidden Beach. This community-driven commitment to the environment exemplifies the harmonious relationship between the people and the land.

However, the passage of time has unveiled challenges to the serene expanse. Encroachments onto public spaces have emerged, impinging on the public’s right to revel in the beauty of Hidden Beach. United by a shared concern, a group of conscientious citizens formed the Friends of Hidden Beach. With unwavering determination, they’re striving to reclaim and rejuvenate the public space, combating encroachments by homeowners and advocating for the rightful enjoyment of all.

Amidst these efforts, a permit application has been submitted to SDOT aiming to restore and safeguard the essence of Hidden Beach. This application embodies the collective spirit of the Friends of Hidden Beach as they work diligently to ensure the beach remains a cherished retreat for Seattle citizens. With hope on the horizon and anticipation in the air, the community stands united in their mission to protect Hidden Beach and its precious connection to nature.

Drive around the idyllic Laurelhurst neighborhood, and you’ll find the street end park at NE 43rd Street. The space offers a serene retreat that blends seamlessly with the area’s charming residential character. Camouflaged by bushes at the edge of Lake Washington, this park captures the essence of waterfront living, allowing residents and visitors to connect intimately with the natural beauty that surrounds them. From its vantage point, one can savor picturesque views of the lake, watching as the gentle waves lap against the shore and boats sail by.

The park’s quiet aura encourages relaxation, making it a prime spot for leisurely picnics, casual strolls, or moments of quiet reflection. Its subtle elegance resonates with the community’s appreciation for both tranquility and nature, a testament to the harmonious coexistence of urban living and natural splendor.

Amidst the lush greenery and blossoming foliage, the street end park reveals its significance as a communal gathering place. Neighbors often come together to celebrate community events, fostering connections that strengthen the neighborhood’s bonds. Children’s laughter echoes as they explore the park’s nooks and crannies, while families and friends enjoy the simple pleasure of unwinding by the water’s edge.

The park’s role extends beyond its physical boundaries, nurturing a sense of belonging and unity among those who share in its beauty. In this haven of verdant serenity, the street end park at NE 43rd Street embodies Laurelhurst’s essence, a microcosm of harmonious cohabitation between humans and their natural surroundings, fostering moments of joy and connection that enrich the lives of all who visit.

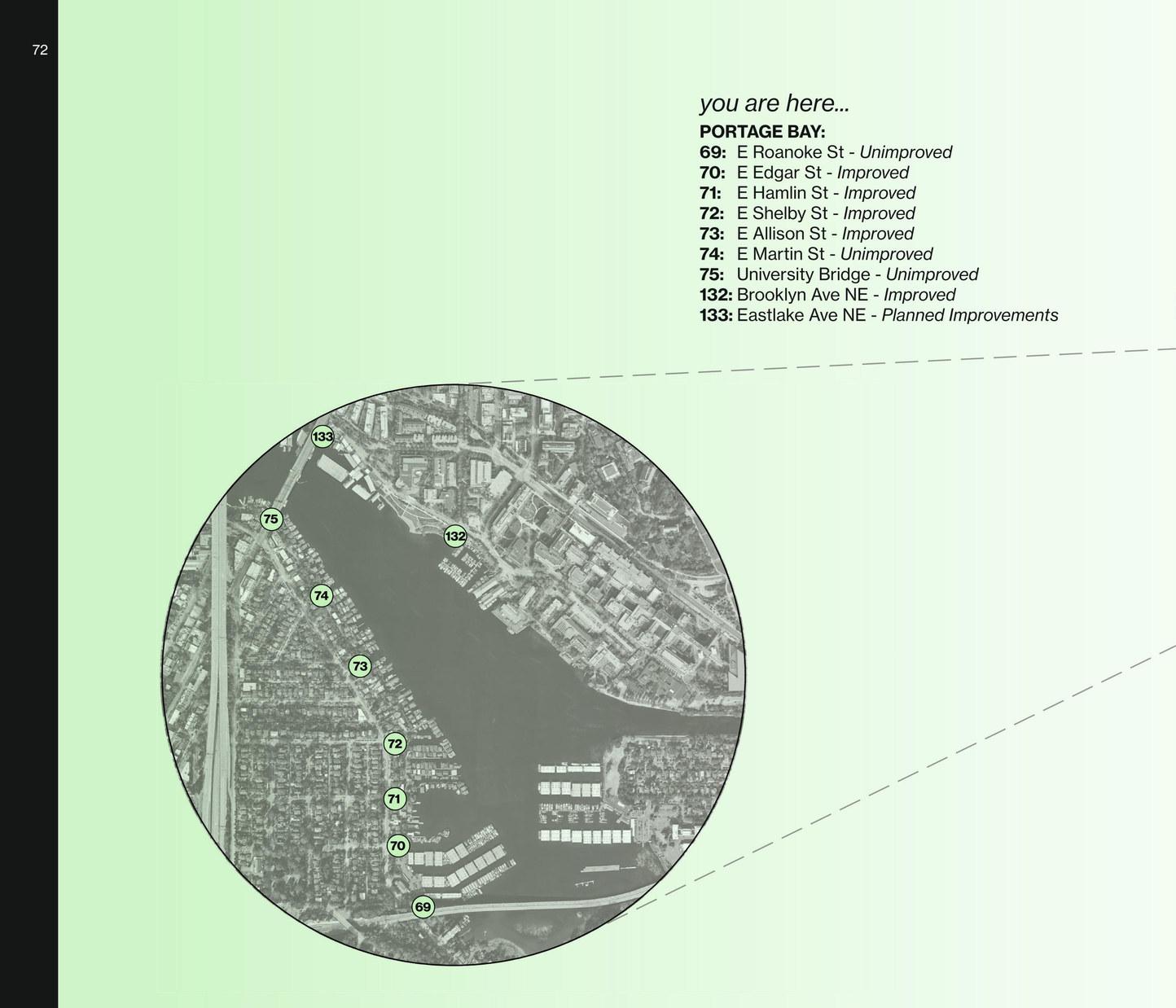

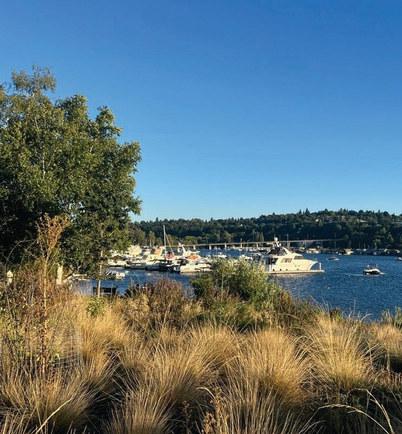

Placed within the vibrant University District of Seattle, the Brooklyn Avenue East street end, known by students as Sakuma Viewpoint, stands as an oasis for the University of Washington community. Gazing out across Portage Bay, the viewpoint offers a picturesque vantage point, capturing the vibrant movement of the iconic I-5 bridge.

A tranquil escape for students and passersby, this scenic spot invites moments of reflection and connection with the waterscape. From kayakers embarking on their journeys to the graceful presence of waterfowl, Sakuma Viewpoint harmonizes nature’s beauty with the rhythm of campus life.

The significance of Sakuma Viewpoint is deeply rooted in the legacy of Professor Donald Sakuma, an admired professor of landscape architecture at the University of Washington. This park, named in his honor, encapsulates his enduring impact on the College of the Built Environment community. Facing Portage Bay along the southern boundary of the campus, the viewpoint serves as a testament to the seamless blend of academia and natural splendor.

Situated at the western edge of the foot of 15th Ave NE, Sakuma Viewpoint occupies a precious stretch of waterfront that converges with Portage Bay, an extension of Lake Union. Anchored by the Fritz Hedges Waterway Park, the area offers a resplendent panorama of Portage Bay, framed by the graceful arches of the University Bridge. Relaxation takes on new meaning with beach lounge chairs on the pier, inviting one to bask in the passage of boats journeying between Lake Union and Lake Washington.

Agua Verde Paddle Club, an adjacent neighbor, complements the experience by offering kayak and paddle board rentals, enabling visitors to embark on aquatic explorations. On sunny days, a makeshift beach comes alive with sunbathers and frolicking beachgoers, creating a vibrant tapestry of leisure and community engagement. Sakuma Viewpoint extends its warm invitation to all who seek a respite by the water’s edge.

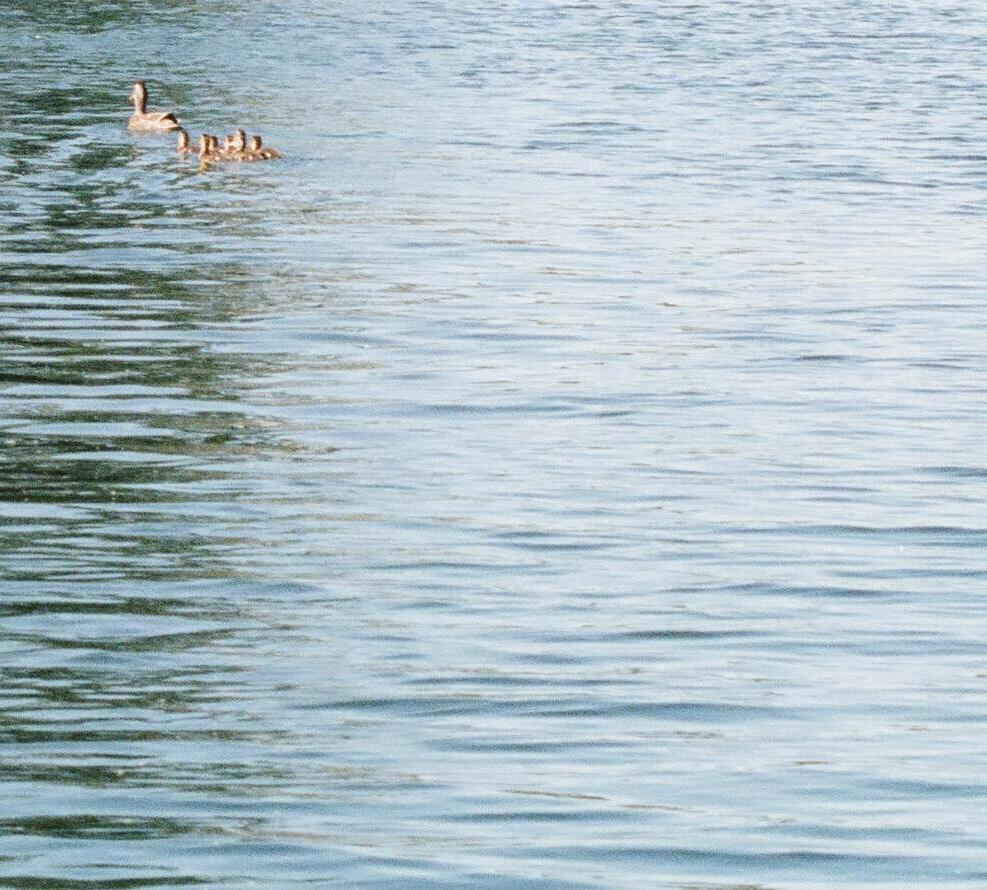

Amidst a community of upper middle class homes and neighboring a golf course, Beaver Lodge Sanctuary stands as a secret lookout, seamlessly connecting the woodsy ambiance with the serenity of the water. As you wander through this understated gem, you’ll discover neat piles of interwoven logs and branches— an intricate patchwork that forms the semi-aquatic beaver lodges. Though the beavers might have chosen to remain elusive on this particular day, their presence is felt, their coexistence with human neighbors emblematic of the harmonious blend of nature and urban life.

This intimate sanctuary, nestled within the heart of a residential enclave, offers a refuge of solace for those seeking respite. Whether you’re looking to indulge in moments of contemplation, unwind with a book, or simply revel in the soothing presence of ducks and geese amid the backdrop of bridge traffic, this is a space that wraps you in nature’s embrace.

The viewpoint also serves as a modest launch point for paddler’s, providing a gateway to observe the diverse wildlife that inhabits the area. As you navigate the waters near the bustling beaver dam, you might encounter the striking elegance of a bald eagle, the stately grace of a great blue heron, and the spirited chatter of mallards, painting a vivid portrait of the wildlife symphony that thrives here.

Those who venture here are greeted by a picturesque scene as nature’s canvas unfurls before them. Lush lily pads and submerged vegetation create an intricate tapestry beneath the surface, adding an element of wonder to the paddling experience. While waves from passing motorboats and the gentle push of the wind are part and parcel of Lake Washington’s character, the journey is a rewarding one, allowing you to explore everything from nearby marshes to the intricacies of manmade structures, like the 520 bridge freeway undergoing transformation.

From its peaceful launch site to the captivating encounter with wildlife, Beaver Lodge Sanctuary is a destination that invites connection—with nature, with the tranquil waters, and with a community of kindred spirits. This tucked-away haven is a testament to the power of discovery as it brings you closer to the water’s edge where the rhythm of the waves and the symphony of nature meld into an exquisite melody of tranquility.

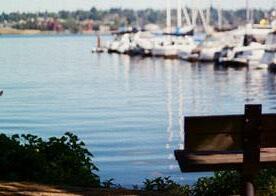

Seattle’s street ends on Lake Union offer a captivating glimpse into the city’s unique urban waterfront landscape. These charming pockets of access, often nestled between ship harbors, open up to the serene expanse of Lake Union. The Seattle street ends on Lake Union serve as inviting respites, where the city’s vibrant energy harmoniously intersects with the soothing allure of the lake, creating spaces for contemplation and connection with nature amidst the urban bustle.

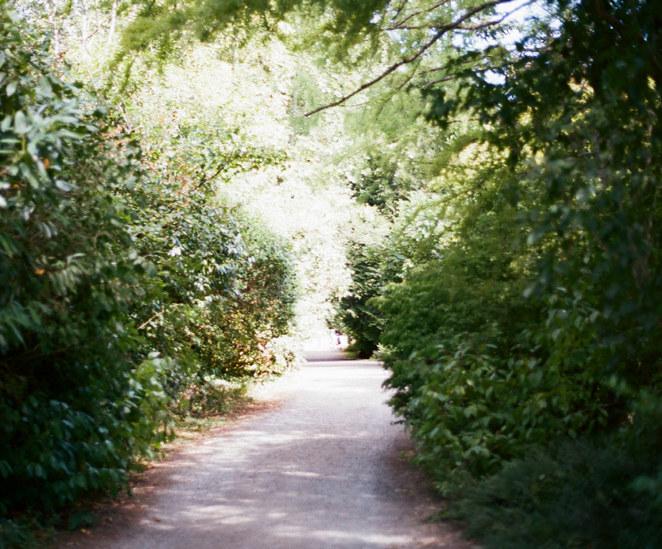

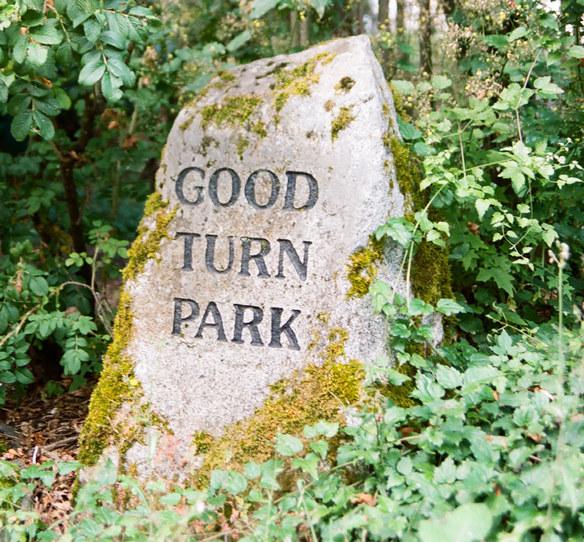

Known affectionately by the locals as Good Turn Park, the street end that sits at East Martin Street holds a significant value for Eastlake locals. An ideal pit-stop along the Chesiashud Loop, this little pocket park seems to exemplify the name. It is tucked in a quiet corner underneath the I-5 bridge, staying cool in the hot summer and dry in the wet winter. A great place to launch a kayak or sit on the shore for a picnic, this park has a modest but sacred feeling.

Thoughtfully cared for by stewards, work parties and community efforts go on year round to keep this park free of invasive species and rubbish. The community’s dedication to preserving this small yet significant park that features chairs, a picnic table, water access, and parking spaces for cars, paddle boards, and kayaks along the lake shore is appreciated.

At Lake Union’s southern edge, mirroring Gas Works Park on the other side, the Yale Avenue North Street End provides a soughtafter viewpoint for Seattleites and visitors alike. Here, tranquil waters meet vibrant streets, offering moments of reflection, kayaking, and companionship. A nexus for sailors and adventurers, the street end mirrors Seattle’s maritime vitality among boat docks and lookout spots. Embraced by native foliage spilling into the lake, it harmonizes urban life and nature, a calm oasis within South Lake Union’s bustling tech scene and dining culture.

As summer envelops the city, the site becomes a lakeside haven, where speedboats, sailboats, and seaplanes compose a lively symphony, capturing Lake Union’s role as Seattle’s heart—a magnetic force fostering connection and shared experiences, encapsulating the spirit of the city in each ripple and glimmer.

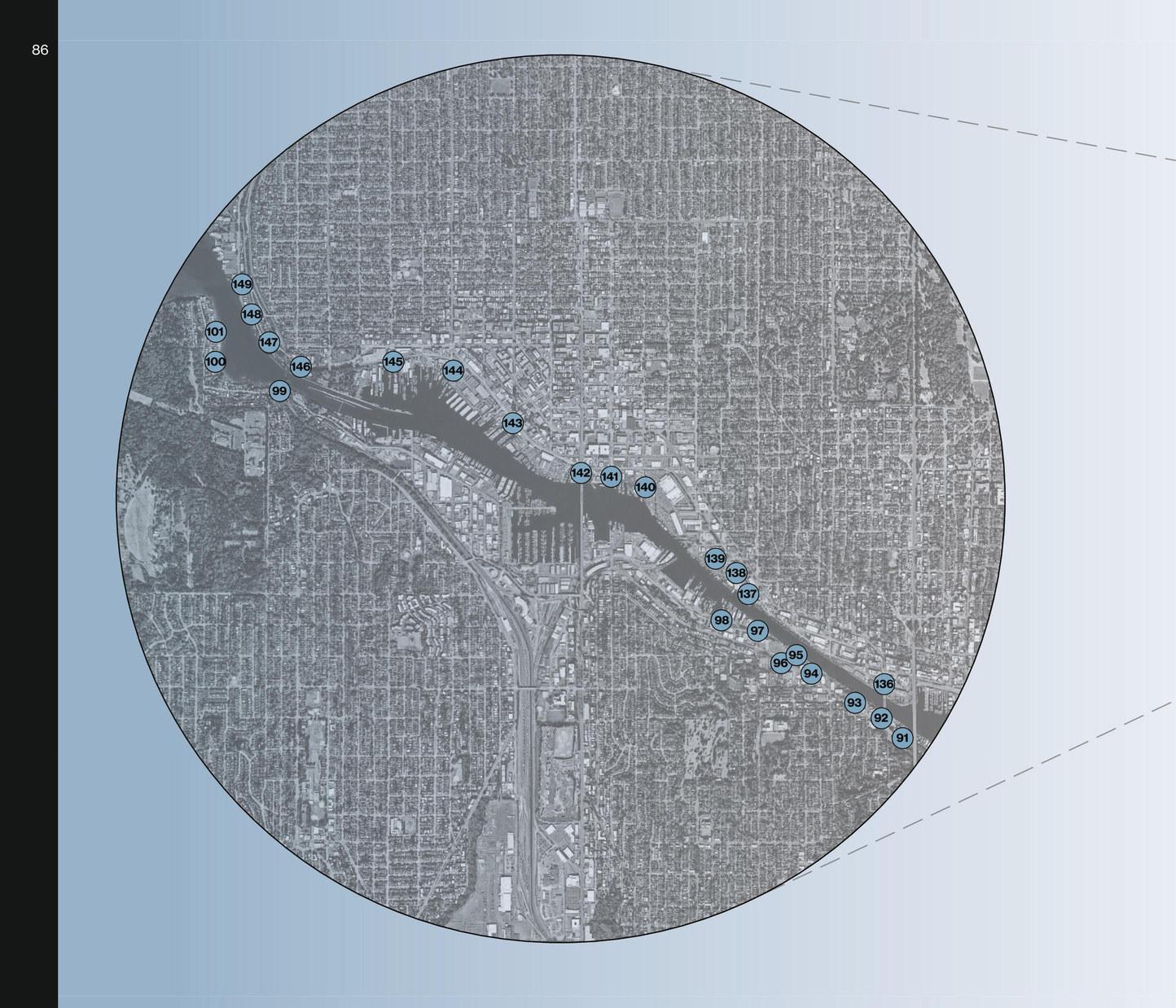

The Lake Washington Ship Canal, an engineering marvel completed in 1917, transformed Seattle’s maritime landscape by connecting Lake Washington, Lake Union, and Puget Sound. Along its shores, quaint street ends offer glimpses into this history, providing public access for enjoying scenic views and recreational activities. These street ends embody Seattle’s enduring relationship with water and its evolving urban fabric.

A curious park at the southern side of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, the 3rd Avenue street end presents a unique charm that resonates with the vibrancy of Seattle Pacific University’s neighboring campus. This inviting street end offers a haven for students seeking a respite from their studies, often seen taking leisurely breaks or savoring lunch moments by the canal’s edge.

Shaded by a verdant canopy of trees, one’s gaze can ascend to a towering power line structure which curiously serves as the nesting abode for a family of Bald Eagles, an awe-inspiring testament to the harmony of nature amidst urbanity. A distinctive feature of this locale is the sight of competitive row teams gliding through the canal’s waters, their synchronized efforts captivating.

As twilight casts its dusky hues, fortunate observers might catch a glimpse of a river otter traversing the canal en route to Puget Sound. The 3rd Avenue street end seamlessly marries liveliness with tranquility, offering a dynamic yet serene ambiance that makes it a truly cherished place.

At West Sheridan Street, a captivating ecological spectacle unfolds as the salty Puget Sound and pristine Lake Washington converge in a delicate dance, a masterful balance of engineering. This enchanting interplay stands as a vivid testament to both human ingenuity and nature’s rhythm, showcased daily by boats navigating the passage. From the Magnolia peninsula’s edge, the view encompasses mountains, sea, and the shared journey of migratory fish and waterfowl, bridging the land’s heart with the water’s embrace.

Here, time takes on a fluid quality, accompanied by trains, boats, and whispered tales of the tides. Encircled by tranquility, the path leads to a natural amphitheater of tree stumps, inviting contemplation. West Sheridan Street offers an unfiltered glimpse into nature’s symphony, blending sea and lake melodies, echoing Ballard’s maritime legacy, indigenous heritage, and the enduring Ballard Locks. This tapestry of humanity and Earth’s rhythms weaves a rich narrative within this serene enclave.

An unexpected vantage point, this street end is technically still unimproved. While in the works of being redesigned, this rugged lookout still provides an impactful experience. Up the street from the Fremont neighborhood, this street end is sandwiched between two industrial warehouses. The asphalt plant to its left, and the ship builders yard to its right, this doesn’t seem like an obvious place to seek respite. As you bike down the BurkeGilman Trail at its backbone you might even miss it, unless you know where to look.

Perhaps this site is best discovered by the water. On a kayak or a paddle board, paddle up to the shore of SSE #137 and take in an open view of the canal. Hummingbirds zip around the overgrown bushes, bald eagles soar overhead.

While this street end clearly needs a lot of love, as evidenced by the eroding slope ripe with invasive species, this place clearly still holds a special charm. On the map this location is right in the middle of what was once the strip of land between Salmon Bay and Lake Union slough, cut through by engineers at the turn of the century.

Plans for this site to be reimagined are being drawn up by Friends of Seattle Street Ends, maybe a simple bench seating area and a solar ground mural paying homage to the Fremont Solstice Parade. Whatever they decide, they seem to know a special place when they see one, and we can’t help but look forward to what the potential of this little pocket park may hold.

Across the railroad tracks next to the notorious Salmon Bay Cafe, this improved street end creates an unexpected scene. Ballard’s industrial district is known for its ship building empire, large and expansive harbors, and bustling urban life. The last thing you would expect to see is a soft native eddy cut into the bank of the canal, providing habitat and lush plantings to enjoy.

Salmon Bay holds a significant history. Reflecting indigenous reverence, its name pays homage to the salmon that held cultural significance long before the area’s industrial expansion, symbolizing sustenance and connection. This native eddy stands as a bridge between the past and present, a sanctuary for wildlife, and a testament to the enduring harmony between nature’s sanctity and human progress.

where the timeless waters of lake washington embrace the horizon’s tender kiss, a tableau of

04 a slice of ecological cake

amidst the gentle ripples, a narrative of centuries past lingers, whisperedinthebreeze...

To comprehend these street end sites, an essential foundation lies in understanding Seattle’s diverse waterways. Each waterbody functions as a distinct ecological entity, and this comprehension guides our innovative design approach. These slices of ecological cake are to represent the distinct flavors of landscape found around Seattle’s street ends.

Seattle’s water systems encompass three main variations: fresh, salt, and riparian. These water types create distinct ecological landscapes, each marked by specific concerns and attributes. Saltwater habitats, for instance, foster entirely different species compared to freshwater rivers a short distance away. While both settings encounter issues such as flooding and erosion, the nuances of each environment present unique challenges.

Prior to delving into our creative design concepts, we lay the groundwork by observing the undisturbed natural state. Recognizing the inherent functionality of habitats and understanding their characteristics informs our endeavors. This preliminary exploration is pivotal, allowing us to devise solutions that build upon existing strengths.

normallowtide normalhightide springhightide

2 3 4 5 6 7

1

UPLAND - above tidal zone

Black-Tailed Deer, Western Red Cedar, Douglas Fir, Deer Fern

UPPER BORDER - reached only by storm surge

Pacific Silverweed, Spikegrass, Tufted Hairgrass, Bald Eagle

HIGH MARSH - reached by salt spray / very high tide

Marsh Wren, Douglas Aster, Pickleweed, Sea Blush, Rush

LOW MARSH - flooded at high tide

Great Blue Heron, Egret, Smooth Cordgrass

SALT PANNE / POOLS - flooded at high tide

Pacific Herring, Smelts, Mussels

TIDAL MUDFLAT - flooded at high tide

Crab, Mussels, Worms, Clams

SUBTIDAL - submerged

Starry Flounder, Chinook Salmon, Kelp, Clams

Seattle’s history is intertwined with salt marshes that once flourished along its shorelines. These coastal ecosystems, rich in biodiversity, provided crucial habitats for a variety of plant and animal species. Unfortunately, extensive urbanization and development over the years have significantly reduced the city’s natural marshlands.

When considering shoreline restoration today, it is important to remember our geomorphological past. When platting Seattle, city planners drew streets ending directly into Puget Sound. This meant that the land around the sound needed to be permanently altered to support houses, roads, cars, and everything else that comes with land dwelling civilization.

Salt marsh environments are not conducive to urban centers because of the sandy substrate and variable tide schedule. The sawdust fill early Seattle settlements used to fill in our salt marshes is still there today, causing many of our waterfront neighborhoods to sink into the water or quickly erode from wave action.

Returning to a softer Seattle shoreline would actually improve erosion conditions and create habitat for native Washington species. This is important to consider as we turn our attention to forward-looking street end interventions.

2 3 4 5

Western Red Cedar, Red Alder, Big Leaf Maple, Douglas Fir

Red-Osier Dogwood, Snowberry, Pacific Willow, Chickadee

Slough Sedge, Baltic Rush, Common Reed, Red-Winged Blackbird

Cattail, Bullrush, Water Iris, Mallard

Steelhead Trout, Chinook Salmon, Pondweed, Muskgrass

Lake Washington, nestled in the Pacific Northwest, boasts a rich history and unique features. One intriguing aspect is its history of reverse hydrology, a phenomenon triggered by the lowering of the lake’s water level to aid navigation. This process altered the lake’s natural inflow and outflow patterns. Ecologically, the lake is renowned for its diverse aquatic life and vibrant ecosystem. Its deep waters host a variety of fish species, supporting a balanced animal population including trout, bass, and waterfowl.

However, Lake Washington has not been without challenges. Over the years, pollution issues stemming from industrial and urban activities have threatened its ecological health. Algae blooms have periodically plagued the lake, driven by nutrient pollution, leading to oxygen depletion and fish habitat degradation. To address these concerns, innovative approaches are essential.

Seattle street end designs can play a role in mitigating these issues. Incorporating green infrastructure such as rain gardens, permeable pavements, and natural vegetation in these designs can help reduce stormwater runoff and nutrient pollution entering the lake, ultimately enhancing water quality and safeguarding the delicate balance of its ecosystem.

1 2 3 4

Pacific Willow, Oregon Ash, Red Alder, Black Cottonwood

Slough Sedge, Baltic Rush, Common Reed, Watercress

Water Plantain, Water Buttercup, Water Smartweed

Waterweed, Pondweed, Salmon, Trout

Seattle’s rivers, notably the Duwamish, have undergone significant geomorphological transformations due to human activities. The once meandering waterways have been altered by industrialization and urban development. This history holds profound significance for indigenous communities, as these rivers were historically central to their way of life. Over time, floodplain encroachment and habitat loss have resulted in ecological challenges.

To restore the vital ecological relationships that have been disrupted, leveraging the potential of street ends along the Duwamish is a promising strategy. These spaces can serve as points of connection between urban areas and the river’s ecosystem. By incorporating nature-based solutions like

riparian restoration, native vegetation planting, and floodplain management into street end designs, it’s possible to reestablish a more harmonious relationship between the river and the city.

These efforts can mitigate flooding, improve water quality, and offer habitat for native species, bridging the gap between historical importance and modern urban demands while fostering a renewed balance in the ecosystem.

there is something sorefreshingaboutth

epugetsound , crisp salty air ... seagull songsechoaboveaswe

the sand on a journey to

fndthe perfect seashell,thesturdiestdrifwood, the smoothest sea glass...

ECOLOGICAL

CELEBRATE CONNECTIVITY

To fully realize the potential of Seattle’s street ends, we’ve developed a list of key ingredients to help guide interventions and improvements. We imagine interventions that can be applied to individual street ends and the network as a whole. These qualities help guide those intentions into deliberate and creative ACTIONS.

Our most central tenet to Key Ingredients is this: while each street end will find its own balance between ecological and cultural considerations, the enhancement of both ecology and culture must be part of every street end. Human experience, and enhanced ecology can and must thrive together!

Each site has its own unique character and with that comes distinct influences. While one location may have more ecological needs or urban influence than another, there is still a harmony between the elements that must be achieved. There is not one without the other in public space, and we hope to use this spectrum to guide our designs in a harmonious way.

The design of a landscape must minimize its negative impact on the environment while maximizing its positive contributions to ecological health. By considering these elements and principles, an ecologically efficient landscape not only enhances the surrounding environment but also reduces resource consumption, supports biodiversity, and contributes to the overall health and sustainability of the ecosystem.

A well-planned landscape design can play a pivotal role in supporting sustainability efforts. Thoughtful selection of materials, like recycled or locally sourced options, minimizes environmental impact and reduces waste generation. A sustainable landscape design not only beautifies the environment but also serves as a responsible and lasting contribution to a greener and healthier planet.

Incorporating habitat-friendly elements into landscape design can be a powerful way to support and enhance biodiversity. By intentionally selecting and planting native vegetation, landscape designers can provide essential food sources and shelter for local wildlife, including birds, insects, and small mammals. Implementing water features, such as ponds or small streams, can attract amphibians and aquatic species, further enriching the habitat.

Preventing pollution in landscape design is a crucial best practice that ensures the preservation of environmental integrity and human well-being. Emphasizing pollution prevention in landscape design not only safeguards the natural ecosystem but also fosters a healthier and more sustainable environment for present and future generations.

Imagine all 142 street ends as a network. Individually they are tiny, but together they pack a mighty punch. By shifting the perception of street ends from individual pocket parks to a fully functional system, street ends in Seattle will be able to fulfill their potential to reconnect Seattle’s shoreline. By emulating environmentally historic conditions in Seattle with native plantings and soft shoreline, the network of street ends could function as a complete ecological system, serving humans and animal visitors alike.

When we say ‘welcome wacky,’ what we mean is to come into the design with an open minded, forward-thinking approach. Forget your budget, the timeline, and any other constraints. Come at the space with the sky as the limit. Get innovative with your technology, get weird with your art, and bring the public along in your journey to find the soul of the place.

Seattle is a bustling town known for its active lifestyle and appreciation of the PNW’s natural beauty. Streets ends can be transformed into pocket parks and waterfront plazas, providing a serene setting for relaxation and socialization. By involving the residents in the planning process and organizing outdoor events and activities, Seattle can embrace its love for the outdoors, turning street ends into thriving hubs of recreation and enhancing the overall urban experience.

We are all about creating moments and spaces that feel special, serendipitous, and notable. We want the unique opportunity of >142(!) street ends to feel remarkable to those who visit them. The list of characteristics that go into a magical landscape is long and complicated, and these are only a select amount of the necessary elements. But I think that’s the point of it, that magic doesn’t just happen, that it is a domino effect of a hundred different puzzle pieces falling into place.

sitabout the hustle and bustle of the canalthatdraws us in? is it the puttering of the boats? thedeep call ofthehornto op en t he draw bridge?

is itthe ener g y of t herow teams as theyhurtleforward into the distance ... or maybe it’s just a fleeting momentslipping into the past...

There are >>142 ways that designers and Seattleites can take advantage of our street end network to activate the shoreline. Whether the imagined opportunity will catalyze cultural experiences or ecological innovation, the potential these pocket parks hold is staggering. Using our key ingredients, we came up with some imagined opportunities of our own. This effort has resulted in some fantastic designs and ideas. We challenge you to think of an opportunity of your own!

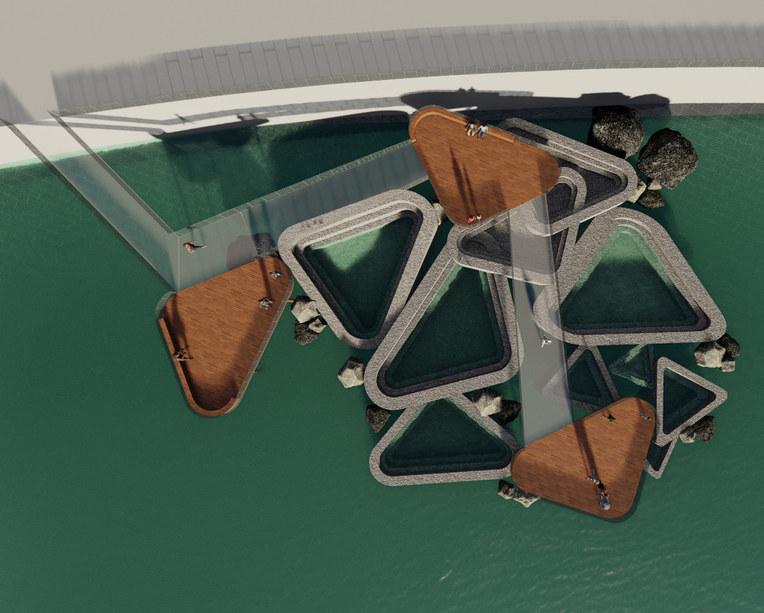

floating wood decked “island” with tree encapsulated in Silva Cell

suspended planter grate that holds sediment, rocks, aquatic plants, and other ecosystem debris

weighted anchors at bottom to counter flotation and add stability

Every year the Chinook, Sockeye, and Coho salmon migrate through the Ballard Locks on their journey to Puget Sound. This hundred-mile journey is the annual culmination of their life and spawning period, a sacred ritual honored and respected by many Northwest indigenous tribes.

The passage through the Lake Washington Ship Canal is relatively recent, as Salmon had to change their course to reach the sound after the cut was made. They are a resilient species that puts up with a lot of traffic and pollution along their journey. We thought they deserved more attention, and so we dreamt up this floating underwater habitat to aid them in their travels.

patterns that salmon need:

sediment mixture clean, cold water

When placed at the end of the numerous street ends along the Lake Washington Ship Canal, this floating habitat island could encourage a safe passage for meandering salmon along their journey. Beds of vegetation and sediment will provide salmon with the perfect combination of hiding places, food, cool water, and sediment mixing.

On the surface, passing visitors could lounge under the planted tree, providing shade for salmon and humans.

A periscope would encourage visitors to check out the habitat below and follow along as the salmon journey to the sound.

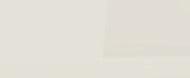

EXISTING CONDITIONS: SSE #132 BROOKLYN AVENUE EAST

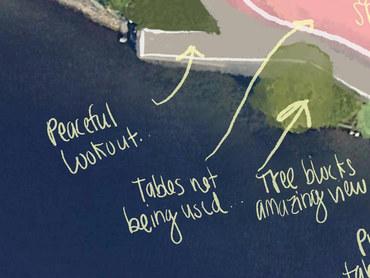

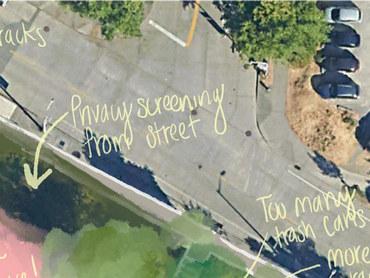

Sakuma Viewpoint is a street end that already, mostly, works. Abutted by well-programmed uses, Sakuma is the least populated of them, and not in a bad way: the peaceful serenity of a grassy lawn in dappled summer sun, picnic tables overflowing with picnickers from nextdoor, and a pier jutting into the open water of Portage Bay. The users of the space are exactly where they want to be: in the quiet nooks of a public outdoor park.

To the west, shiny, polished, showy Fritz Hedges

Waterway Park teems with college students sunbathing and launching paddle boards and kayaks. To the north, a vibrantly bustling café serves margaritas on tap and rents out boats. And yet, Sakuma seemingly sits in limbo. Forgotten? Slipping into the cracks of time? Intentionally preserved?

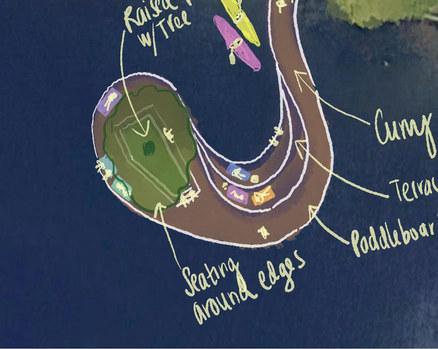

This intervention seeks to embrace a part of Sakuma that is already great, furthering the spirit of the place. A floating dock, simply an extension of the pier already extending into the bay, provides an amenity missing from this mini waterfront at UW: public jumping access to deeper water. While a wading beach exists to the west, and a boat dock occupies the east, the Sakuma dock marries both to create a new use.

Flexible spaces along the dock provide for lounging in tree-dappled shade, alone or with friends, views across and down the bay, and water access for swimming or pulling up a kayak for lunch.

In a city so attached to its water, public access is scarce. By incorporating uses other than viewing, and instead giving everyone interactive and sensory access to the water, public street ends and the waterfront become increasingly equitable public spaces.

Oyster Breakwaters are a technology being tested and employed in oceans around the world. Over at Reef Ball Foundation, engineers and scientists have found a way to create fully functioning oyster reefs in less than a year with 100% coverage by oysters. These “reef balls” function as both habitat for oysters and as breakwater barriers to mitigate the impact of the waves against the shoreline.

1

2

Reef Balls are created with a mix of concrete, silt, and shells.

3

The artificial reef also creates an environment attractive to other marine animals and plants.

The only native oyster to Washington, the Olympia Oyster, is listed as a species in greatest conservation need, very close to being classified as endangered. If these concrete oyster reefs could be installed along every Seattle street end landing on Puget Sound (all 29 of them!), we could make a significant impact on the rehabilitation of this sensitive species.

Oysters are immensely valuable to coastal ecosystems. They can filter as much as 50 gallons of water per day, greatly improving water quality. Oyster reefs improve habitat for other species, such as mussels, barnacles, and sea anemone. This allows the ecosystem to thrive by providing food for fish and other larger sea species.

The Duwamish River has had a long history of geomorphology, caused by both natural and human interventions. This map shows the lower Duwamish at its current form, alongside its historic meander and marsh land. The Lower Duwamish River is the last leg of the Cedar River Watershed, carrying sediment and life from hundreds of miles away.

Today, the river flows through Seattle’s industrial underbelly, surrounded by concrete and shipyards. Many of Seattle’s combined sewer outfall stations land on the Duwamish, and quite of few of those intersect with street end sites as well. What if we could find a way to clean that sewage before it entered the Duwamish?

CURRENT DUWAMISH RIVER TOPOGRAPHY

HISTORIC DUWAMISH RIVER TOPOGRAPHY

HISTORIC DUWAMISH MARSH LAND

SEATTLE STREET END

SEATTLE STREET END W/ COMBINED SEWER OUTFALL

Taking one of the Duwamish River’s industrial street end sites and turning it into a rain garden/bioretention facility is a simple intervention that would have a big impact on runoff entering the river. The natural meander of the historic Duwamish would have had multitudes of eddies and tributaries feeding its flow.

Daylighting some of these outfall stations and naturalizing them would allow for a simple solution to clean the pollution. The shore would begin to feel more welcoming to visitors, and some of the native ecology would be able to return. This solution would also allow for a softer shoreline to address flooding, a problem only expected to worsen with climate projections for the area.

Seattle’s central waterfront is a waterfront forever altered. The soil mudflats of Elliott Bay, once charged with nutrients and habitat, have been hardened, destroyed, and filled with the hard edge of the city. The opportunity here is not to recreate a lost ecology but to build an ecology that meets the reality of today.

The replacement of the mudflats with hardened edges and steep tidelands provides the opportunity for an ecology that has not yet existed here; Elliott Bay can be notably benefited by artificial tidepools. Tidepools play an integral role in intertidal ecosystems in other parts of Puget Sound and the Washington coast.

Artificial tidepools can increase biodiversity and habitat, so the plants, animals, and organisms of coastal ecologies can thrive.

Ridges act as shelves for the flora and fauna to adhere to

Varying depths of tidepool basins can range from inches to feet deep

BARNACLES, SPONGES, ANEMONES

SEAWEED, KELP, ALGAE MUSSELS, URCHINS, LIMPETS, STARFISH, SNAILS, CRABS

At high tide, every swell of seawater brings new organisms and resources; tidepool communities welcome wacky with every wave...

Lake Washington is home to a thriving population of beavers that play an integral role in the local ecosystem. These industrious creatures have found a welcoming environment along the shores of the lake with its abundant aquatic vegetation and suitable water sources.

Beavers have been observed constructing intricate dams and lodges, shaping the landscape in their own unique way. Their presence contributes to the natural beauty of the area, fostering a sense of coexistence between human residents and the diverse wildlife that calls Lake Washington home. These beavers, through their dam-building and pond-creating activities, not only enrich the local ecology but also remind us of the interconnectedness of nature in this serene waterfront community.

Incorporating a beaver deceiver into a street end design would be a smart way to manage and control beaver activity to prevent unwanted flooding while still benefiting the environment.

A beaver deceiver is a cleverly designed water control device used to manage beaver activity while minimizing potential flooding in urban or developed areas, like street ends along Lake Washington. This ingenious contraption allows beavers to continue their natural dam-building behaviors while preventing excessive water buildup that could threaten nearby infrastructure or roadways. By regulating water levels through a pond-leveling pipe, the beaver deceiver maintains a balance between the needs of beavers and human-designed spaces.

In a street end design on Lake Washington, a beaver deceiver would benefit by preserving the aesthetics and functionality of these public spaces while also promoting a harmonious coexistence between humans and local wildlife, including beavers. It prevents costly flood damage and facilitates a peaceful cohabitation that respects the natural behaviors of these fascinating animals.

Puget Sound boasts over 1,400 miles of beaches primarily composed of sand and gravel eroded from nearby bluffs. The region’s irregular coastline influences sediment movement and the formation of local shoreline features, like feeder bluffs and barrier beaches. However, Seattle’s waterfront underwent extensive regrading efforts to enhance its maritime port, which erased much of its coastal complexity. Steep bluffs were either flattened or fortified with walls, and the once expansive beaches disappeared under material from inland operations like the Denny Regrade.

The geological history of Puget Sound underscores the importance of these bluffs as sediment sources, impacting spawning habitat, organic debris accumulation, and the maintenance of coastal ecosystems. As sea levels rise along armored shorelines, beaches narrow, and seawall water levels increase, necessitating more robust defenses. To preserve Washington’s beaches and nearshore ecosystems, allowing shorelines to erode landward and tapping into sediment from eroding bluffs is crucial.

Although bluffs often don’t offer direct water access due to their steep slopes, the beaches they create are enticing. Discovery Park remains one of the few remnants of this bluff-to-beach experience in the city. The construction of the Seattle Lake Shore and Eastern Railroad at the bluff’s base initiated the rapid transformation of a coastline that had taken millennia to form.

beach face backshore

low-tide terrace

subtidal zone

boat access

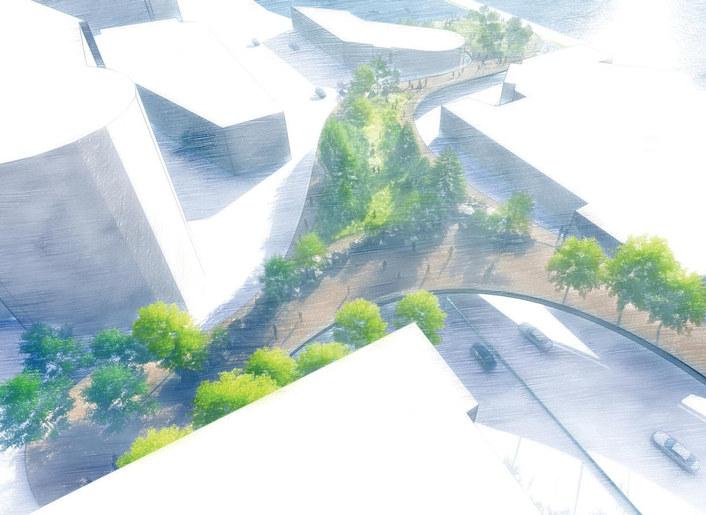

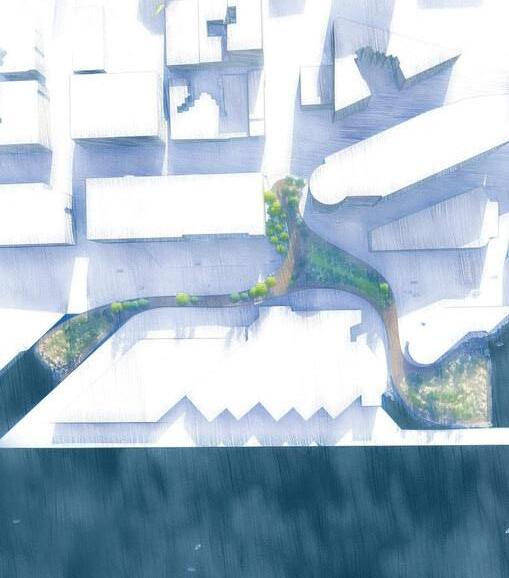

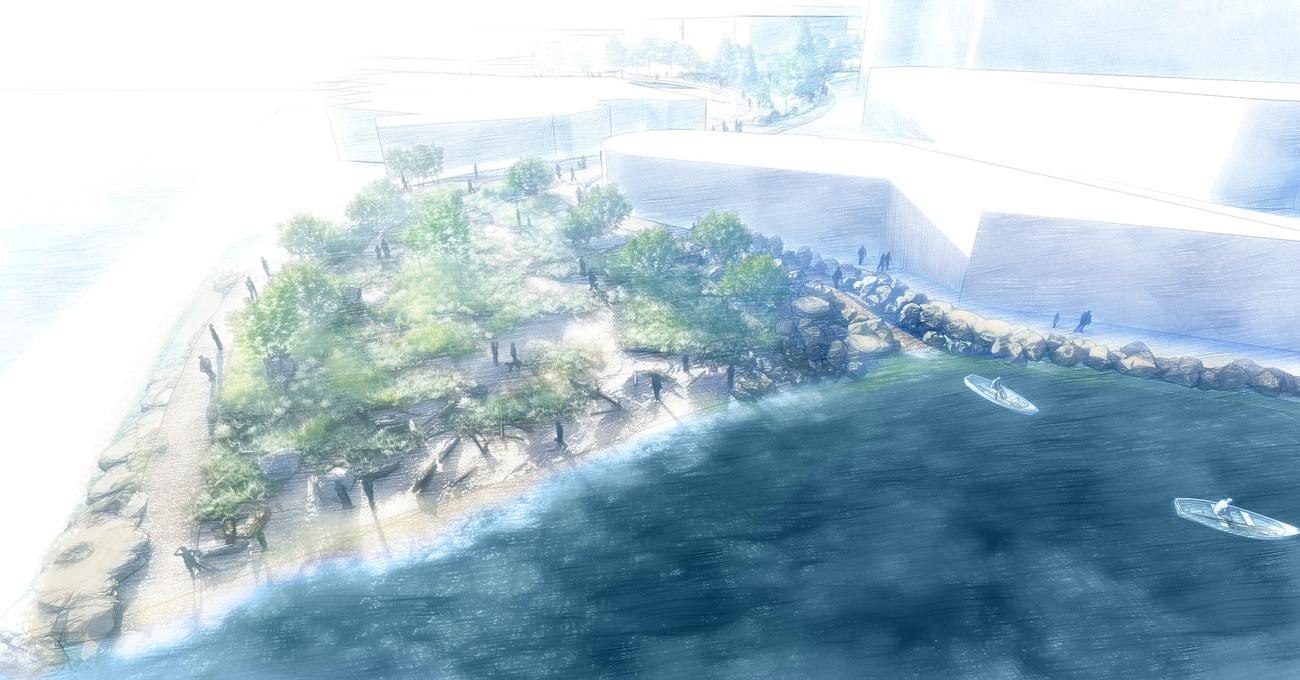

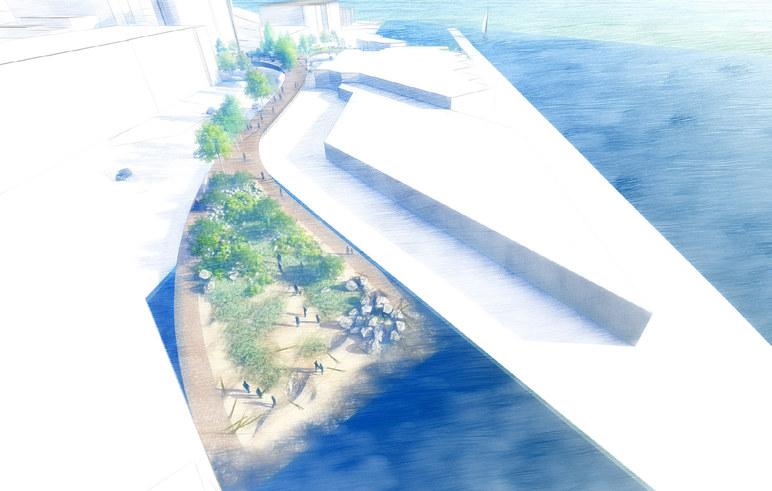

The proposed land bridge represents an innovative approach to reconnecting people with the waterfront while simultaneously addressing the ecological needs of the shoreline. Inspired by the flattened bluff ecology, this land bridge concept aims to create a harmonious interface between humans and the natural environment.

CELEBRATE CONNECTIVITY

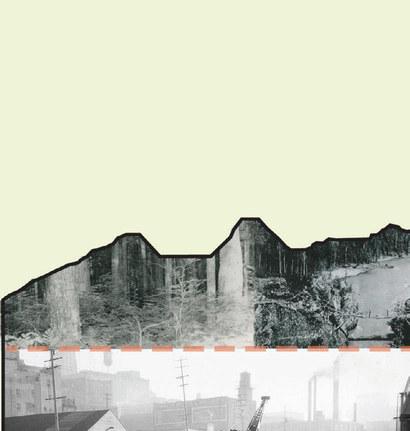

As much as any city in the world, the landscape of Seattle has been boldly reshaped by humans over the last century in the name of progress and commerce. The scale of change is massive, even geologic, literally altering the topography left by glaciers. Yet this created reality, much of it over a century old, is now accepted and seen as “original,” “right,” and even “natural.”

How can we make visible the overlooked, forgotten, and hidden history and archaeology of such a massively altered place?

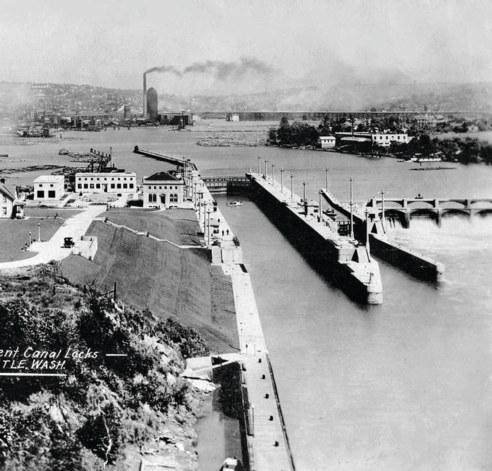

Salmon Bay existed for millennia, a narrow, tidal embayment off Puget Sound, left by retreating glaciers, an estuary ringed by temperate coniferous forest. That all changed in the early 1900s when the bay was dammed with the Hiram Chittenden Locks as part of a massive scale “replumbing” of the entire region to grow maritime access through the city.

Once salt water became fresh, varying tidelines became a static water level, and shoreline was hardened and filled to support commerce and maritime uses. The historically enclosed embayment became the flow-through and outfall for the massive Lake Washington and Lake Sammamish watersheds.

While the bay’s original limits and size are similar to today’s, everything else about the ecology and landscape is changed, with both benefits and impacts, including ever-declining salmon runs that now must navigate “new” routes to reach their historic spawning grounds.

It is a fascinating study of altered landscapes of which the tens of thousands of people who interact daily with the bay are unaware.

We dream of leveraging the collection of street ends along the bay (with other public waterfront access), considering and shaping them collectively, to bring to life the change, archeology, and future of Salmon Bay.

thelastpoppiesofsummer soakintheaugust light, the orange glow re v e r b e r a t gni a ob u t t h ebeach, casting sof andsil entshadows on the sand ... thereisnothing h berehttu e g e n t le t

07 actions & reflections

flip your perspective on design and interconnectedness 1 2 3

identify “social leftovers” hiding in your city

share, support, gather, and collaborate with your community on imagined opportunities

This began as a project about water. A closer peek at our curiosity surrounding it, why it feels so meaningful, and where our place within it is. And then it was just about the street ends, how many there are, what the incredible abundance of them means for our community, our history, and our reality.

Then, we started digging deeper. I visited as many street ends as I could. I sat and I took them in, started dreaming about what they could be, and how far they could go. I wanted to know what made them so special, and also what I could do to advocate for them.

It makes you start to think, how could we open this all up? How could we use these little pocket parks to maximize the abundant interconnectedness of our waterways?

And so I sat down with Berger Partnership and we brainstormed. We dreamed into the future and started to sketch, to draw, to paint, to draft. We had conversations with the people closest to the cause. We talked about what it means to them and what they want from all of this. And came up with a couple ideas and threw them in this book. It isn’t perfect, and it isn’t complete.

We just barely scratched the surface of something really important. It’s something that is meant to open up larger conversations, more collaboration, voices from designers, planners, architects, activists, beach lovers, and lake swimmers. Sometimes, asking questions leads to more questions and less answers. While this book is ending, the conversation has just begun.

How can we get back to the water? How can we find our place within it?

How does our relationship with the water inform our relationship with the land?

How can design and ecology and people and community and river and ocean and land all come together and harmonize into the most wonderful song?

The production and completion of this report could not have been done without the support of the local Seattle community including Omar Akkari and Meredith Grupe of the Seattle Department of Transportation for providing necessary map data and information on the street end program, and Marty and Robin Oppenheimer of Friends of Seattle Street Ends for their input on Seattle’s street end history, which is so long and complex that I barely scratched the surface. I would like to sincerely thank those who took time to answer my questions and meet with me during this process.

I would like to thank my friends at Berger Partnership, especially Guy Michaelsen and Belle Miller, for their daily support and encouragement in this process. Also, Evan Blondell and Stephanie Smith for taking on a street end design of their own. This book is a collaborative effort, and it is with brainstorming and many meetings that its pages were filled.

Lastly, I would like to thank my family for encouraging me to go outside and appreciate my surroundings in nature. From them my curiosity grew and landed me here.

Seattle is blessed with an interwoven web of waterways, lakes, rivers, canals, and Puget Sound, sometimes a barrier, sometimes a connection, and always shaping the experience and soul of our city.

Over this web of water and the hills that shape it, a rectilinear street grid stretches across the whole city, a human-shaped attempt to organize and impose structure on glacially shaped landscape.

Where our city meets the water is where the street ends, and something entirely new can begin … a place of alchemy ... where a series of unplanned, leftover spaces—relics of the collision between engineering, planning, and geography— can be seized and reimagined. Interconnected shorelines where human experience and ecological enhancement can thrive together.