Shadows In the Moonlight

The Secret Lives of Forgotten Pollinators and Gardens of the Night

Summer Internship 2024

Phoebe Chuang, Intern with Paulina Arango, Belle Miller & Jason Henry

Shadows In the Moonlight Shadows In the Moonlight

The Secret Lives of Forgotten Pollinators and Gardens of the Night

Summer Internship 2024

Phoebe Chuang, Intern with Paulina Arango, Belle Miller & Jason Henry

Table of Contents

1. Wild Nights in Cities

2. Designing for Darkness

3. Graveyard (Shift) of Pollinators

4. Let the Shadows Meet You

5. Darkness for You and Me

6. Moon, Moth, Mother Nature

1. Urban Wildlife

WILD NIGHTS IN CITIES

Cities as... Places of Ecological Interactions

Contrary to the popular belief that cities and urban satellite areas are the source of destruction as well as the opposite of natural ecology, they are increasingly recognized as a part of a young, novel ecosystem with its own resources and a web of organisms that utilize them. However, the homogeneity of most modern urban environments and the lack of baseline research of these places tend to spark debates on the benefits of these urban ecosystems for urban wildlife and global biodiversity long term.

Nocturnality of Urban Wildlife

To further complicate the issue, research has discovered that across the globe, animals have increased their nocturnality by an average factor of 1.36 due to human activities and disturbances.1 This means that if an animal was previously 50/50 in day/night activity level, they would become 32% active during the day, and 68% active at night as they adjust to the urban lifestyle. The result, combined with the sharp increase in animal sightings in cities across the globe during Covid-19, shows not only the impact of human activities on animals, but also the growth of the urban wildlife population, which has continued in the past century in European, East Asian, and North American cities.2

Light Pollution is All Over the World

As more and more urban animals opt for the nocturnal lifestyle, the impact of artificial light at night and light pollution grows.

According to the world’s first Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness, published in 2001, not only were the developed countries the sources of light pollution, so were the developing ones.3 In addition, more than one-fourth of the people in the world then (including 80% of the US and two-thirds of the EU population) experienced night sky brightness greater than that of the full moon. According to the researchers, “Night never really comes for them.”4

Progression of Artificial Light at Night (ALAN)

Light pollution has not only intensified but also accelerated quickly in its short history since the inception of electric lights. To put it into perspective, every generation of human beings until about 200 years ago experienced a sky filled with stars every night.5 A study conducted 15 years after the initial World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness showed that 83% of the global population now live under light-polluted night skies (a 17% increase in a span of 20 years).6 Moreover, places like Singapore, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Israel, Argentina, and Trinidad all have more than half of their residents living under night skies so bright that their eyes cannot fully adjust to the dark, affecting night vision.

Not only is the acceleration of light pollution a concern, so are the impacts of sky glow: artificial light scattered in the atmosphere. The visibility of the light domes from Las Vegas and Los Angeles in Death Valley National Park in California serves as an example of the far-reaching impact of sky glow from cities on otherwise pristine natural environments. Furthermore, when combined with the overcast skies, the impact of sky glow can increase sevenfold, which has further implications on how local weather may amplify the intensity of light pollution beyond the current observed baseline.7

ASIA

ALAN Influences... Ecology & Evolution of Species

As much as there are positive influences of Artificial Light at Night (ALAN) on urban animals, ecological light pollution that changes the natural diurnal cycle of light and dark in ecosystems tends to bring more harm than good.8 Moreover, sensory pollution as a direct consequence of ecological light pollution can greatly influence how animals navigate both in the environment and in life. According to Ed Yong, a Pulitzer Prize-winning science journalist, the rapid changes in the abundance of lights at night in the last 200 years has effectively ended a four-billionyear streak of daily rhythms of light and dark on the planet, casting potential doom for countless species.9

By drowning out other natural light sources at night with ALAN, humans have not only reduced the habitat quality for many species, but also “flattened” the landscape and

decreased its variation. Since variations of light and dark at night helped create diversity in various traits such as vision, color, and behavior, to tackle the problem of light pollution is to simultaneously preserve and increase biodiversity.

In their research, Sordello et al summarized that the immediate impact of ALAN includes the “avoiding” or “sink/crash barrier effect” (see illustration) that either repels the wildlife or attracts them.10 As a result, habitats fragmented by ALAN that become ecological sinks can lead to a reduction in habitat patch size and suitability. Since lower habitat quality decreases species fecundity and survival rate, and ultimately leads to reduced population size and genetic diversity, the presence of ALAN would effectively form the “extinction vortex” that results in higher extinction probability and reduced biodiversity.

Ask Where the Darkness Needs to Be

The rise of nocturnal urban wildlife and increasing light pollution emphasize the need for urban rewilding. Light pollution disrupts wildlife, fragments habitats, and reduces biodiversity. Design professionals like landscape architects and planners can address this by rethinking nighttime design to preserve or reintroduce darkness, restore ecological balance, protect biodiversity, and foster healthier coexistence between humans and wildlife.

Most of the birds (over half of 630 North American species) we see during the day do in fact migrate at night biannually. The events involve billions of avian individuals, across taxa, size, age, and sex. Every fall and spring, birds of the Americas travel under the cover of dark skies across the continents via major migratory flyways, including one over the Pacific Northwest.

1. Urban Wildlife

2. Dark Infrastructure

DESIGNING FOR DARKNESS

Lets Us “See” in New Light Darkness...

In the dark, the limitation of our vision heightens our other senses that detect stimuli: auditory, olfactory, and tactile. This presents a unique opportunity for us to utilize other non-visual senses and exercise our imagination. Similarly, “seeing” places in darkness can offer new perspectives and enable us to ask questions that are not often considered such as, “why should we have more darkness and where should the darkness be?” These questions are fundamental to the theory and application of dark infrastructure that functions primarily to protect biodiversity.

The Dark Side of Green & Blue Infrastructure

Often in the form of a planned network of natural and semi-natural areas, green infrastructure plays a role in maintaining biodiversity in fragmented urban and rural landscapes and providing a range of ecosystem services to people.11 When green infrastructure is established for aquatic habitats, it is called ”blue infrastructure.” Dark infrastructure is created by adding darkness quality and availability into the establishment criteria of green/blue infrastructure. Its functions are not only to mitigate light pollution but also to reconnect habitats for nocturnal wildlife by removing and minimizing the intangible walls of ALAN.

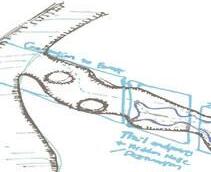

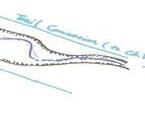

As a general framework, the process of establishing dark infrastructure starts with investigating the darkness quality of the landscape by documenting various forms

and dimensions of light pollution. A dark core that covers habitats of nocturnal wildlife is identified (which often overlaps with existing green/blue infrastructure), and actions that save or restore darkness are implemented accordingly. The last step involves the assessment of the dark infrastructure’s effectiveness by comparing the before/after implementation performances.

Planning of Dark City in Switzerland

Dubbed as the “nocturnal city of tomorrow,” the Swiss city of Fribourg is a textbook example of dark infrastructure planning at the city scale.12 By analyzing the region’s biological quality and geographical characteristics, a dark grid was created around the River Sarine and its tributaries. The lighting plan included phosphorescent gravel, bright path surfaces, LED fixtures with specific optics, and motion sensors along the river trails. These measures minimize light pollution and accommodate pedestrians and cyclists even on moonless nights. In addition, the lighting schedule adapts to the seasons and the life cycles of local wildlife.

Proposing Dark Corridors for Bats

In The Hague, the approach to dark infrastructure focused on bat conservation.13

A thesis project of Aileen Hallie from TU Delft started with an analysis of the HagueRotterdam region, identified the dark core, including two wooded parks, and highlighted missing connections between them. The project proposed a dark corridor along Haagse Beak to connect the two parks to improve habitat connectivity for bats. The corridor features night-flowering meadows, darkened bridges, and street intersections.

Advocating for New Zealand Dark Infrastructure

Planning for dark infrastructure is not exclusive to municipalities or scholars. Any person who is interested in the issue can affect the process. As an advocate for the dark sky in New Zealand, Kyra Xavia has been working with the local government to establish dark infrastructure at Dunedin, Birdlings Flat and Christchurch for wildlife.14

By demonstrating the look and feel of wildlife-friendly LEDs to residents, she helped change their mind about these alternative lightings. Together, they successfully lobbied to replace two-thirds of the old 4000K streetlights with 2200K lights and implemented a nightly lights-off period.

Strategies for Urban Darkness Preservation

In cases where a site has already been selected based on other criteria, and wildlife is not the main focus of the design, we can still keep darkness preservation in mind and incorporate it into the project. For example, retaining the day/night cycle at a hospital garden with dark pockets,15 playing with light and shadow at an urban plaza using gobos (a lighting fixture that projects a pattern),16 preserving the night sky by designing lights that adjust to the moonlight intensity at a rural church,17 and considering nighttime urban circulations and space use to reserve dark zones at a university campus.18

View Places through the Lens of Darkness

Darkness enhances our non-visual senses and off ers new perspectives. By integrating dark infrastructure with existing green and blue infrastructure, we can create better ecological corridors in cities. Case studies from Switzerland, the Netherlands, and New Zealand showcase diff erent approaches to incorporating darkness in design and planning projects, even when wildlife isn’t the main focus.

Urban gardens and farms are typically designed for daytime pollinators like butterflies and bees but neglect nocturnal pollinators such as bats and moths. Considering dark infrastructure can not only make cities more wildlife friendly, but also make them more robust in response to the climate crisis.

Once hatched, newborn sea turtles need to get into the ocean as soon as possible to avoid predators. The reflective surface of the seawater acts as a navigational cue for them. However, the shining artificial lights from beachfront properties and developments often mislead them and lure them away from the ocean. Switching out these lights with low-wavelength light bulbs is often an eff ective strategy in getting these babies to the place they need to be.

3.

Nocturnal Pollinator

1. Urban Wildlife

2. Dark Infrastructure

GRAVEYARD (SHIFT) OF POLLINATORS

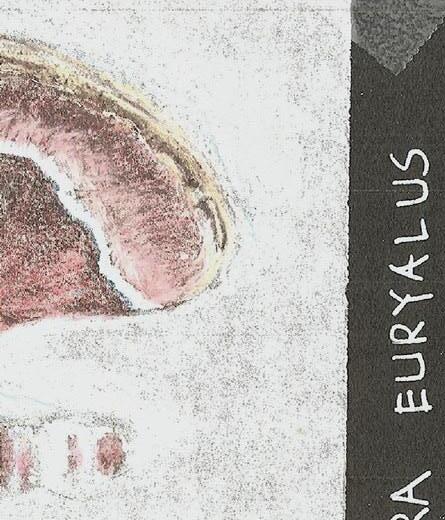

Nocturnal Pollinator of Southern United States

Fun Fact: Without bats as pollinators, we would not have tequila!

Forgotten Pollinators Who Are Active at Night

Moths can be both daytime and nighttime pollinators, but as a group, they are the majority of nocturnal pollinators in many places. Moths make significant contributions to plant pollination due to their diversity (there are about ten times more species of moths than butterflies).22

A study has also shown that certain species of moth are just as efficient as European honeybees in pollinating apple trees.23 In addition to crops, moths are found to be even faster than daytime pollinator insects in the case of wildflowers.24

Night Lights On Pollinator Insects and Plants

According to a recent publication, moths and other flying insects have a physiology that demands them to always fly with their backs to a light source at night.26 However, due to the point source nature of outdoor artificial lightings, they are often stuck in a loop around the light until either a crash occurs, or exhaustion sets in.

Not only has ALAN been linked to an estimated nine percent decrease of the global insect population in the past decade, but plants pollinated by nocturnal pollinator insects such moths, beetles, and nocturnal bees, are also less likely to be visited if there are lights nearby.27 In a U.K. study, streetlights were found to half the moth abundance at the ground level while increase about 70 percent at the light sources.28

Like animals, plants also have circadian rhythm and use light as a cue to organize their activities. By investigating a database containing 13 years of plant budburst data of selected deciduous tree species in the U.K., researchers demonstrated that ALAN plays a role in the early budburst of these plants.29 The disruption of the plants’ circadian rhythm can lead to changes in flowering and fruiting patterns, reduce pollinations, and create the trophic mismatches (misalignments of animal activities and the required resources) that influence the lives of many wildlife.30

When plants grow under ALAN, their leaves become tougher, which could stunt the growth of caterpillars who eat them. The smaller caterpillar will impact the growth of their predators such as birds, causing a rippling effect in the food web.

3.

Nocturnal Pollinator

1. Urban Wildlife

2. Dark Infrastructure

4. Design Toolkit

Life in the Dark as Pollinators and Plants

Pollinator Syndrome is the phenomenon that plants and pollinators who interact with each other have specific physical characteristics used for attracting one another.31 In the dark, colors become a less important cue for attracting animals. Take plants that need bats for pollination for example: they tend to open at night, are large in size (1”-3.5”), and are bowl-shaped, pale, or white in color, very fragrant, with a fermenting or fruit-like odor, and have copious amount of diluted nectar. A list of bat-attracting plants include evening primrose, moonflower vine, four o’clock angel trumpets, night-blooming cereus, agave, and other desert flowers.32

Plants that attract another major group of nocturnal pollinator, moths, also share similar characteristics with plants for bats. They tend to be white or dull in color, open late in the afternoon and night, and have a sweet scent.33 Flowers in clusters, with landing platforms, and with nectar deeply hidden are preferred. Plants such as morning glory, tobacco, yucca, gardenia, milkweed, blazing star, bee balm, evening primrose, mock orange, phloxes, cherry and plum, sage, catchflies, goldenrod, and clover are all good moth-attracting species.34

Sonoma Coast Yarrow

Moonflower

Easter Bee Balm

Desert Evening Primrose

Design Toolkit for the Forgotten Pollinators

Map the Darkness Quality on Site and Nearby

What to take note of:

Light pollution assessment

Shadow locations

Select Target Nocturnal Pollinator Spaces

Sightings of surveys on site or nearby (or the lack thereof)

Determine Additional Site Programming

Data to gather: Consider:

Species research on lifecycle and habitat requirements

Availability of near-perfect habitats

Site use patterns

Mode of interactions between people and nocturnal pollinators

Mitigate Deadly Attractions or Unwanted Deterrents

Is light needed?

Is the light shielded?

Happy Nocturnal Pollinators!

Look into IDA’s “DaySky Approved” Lighting Fixture35

Is the light in warm colors?

Read Dr. Travis Longcore’s paper titled: A compendium of photopigment peak sensitivities and visual spectral response curves of terrestrial wildlife to guide design of outdoor nighttime lighting36,and look for figure 7

Create Habitats to Invite Nocturnal Pollinators

Where on site could each pollinator group be using?

Consider the placement of dark and lit pockets

Determine activity zones for all (pollinators + people)

Which plants could be in each area?

Place plants in activity zones based on site conditions (sun/shade + wet/dry)

Group plants with different bloom season, color, size, shape, and function (host/food/viewing)

Is there space for a water source and shelter?

Happy Nocturnal Pollinators!

Is the light as dim as possible?

Is the light timed or controlled?

Reference fig. 2 on cibsejournal module 147 (https://www. cibsejournal.com/cpd/ modules/2019-06-eye/)37

Visit “https://visibledark.ca/ energy-saving-leds-increasinglight-pollution-globally/”38 and see the diagram of energy savings comparison

Create shallow water with gravel bottom

Preserve snags and fallen leaf litter

How will the site be maintained throughout the year?

Keep the leaf litter undisturbed on the ground

Don’t mow or only mow in late spring

If Nothing Else, Remember This: Half of Any Place

After Dark.

3.

Nocturnal Pollinator

1. Urban Wildlife

2. Dark Infrastructure

4. Design Toolkit

5. Moth

DARKNESS FOR YOU AND ME

Lights at Night in the Rain City

As a place that inspires the cloudy dark ambiance of the novel series Twilight, Seattle is known for its overcast atmosphere. Perhaps the cloudiness and the grays of Seattle are contributing to the light pollution and the lack of natural darkness, which begs the question: can Seattle get any darker for the sake of local wildlife? Can the city appreciate the gray more through the contrast with the darkness?

Seattleites: Moth Edition

According to I-Naturalist,39 there are of wild moths logged in the Seattle area.

To the right are a few sample species:

Pollinator Partnerships in the Emerald City

A Seattle Pilot Site for Moths

3. Nocturnal Pollinator

1. Urban Wildlife

2. Dark Infrastructure

4. Design Toolkit

5. Moth

6. Dusk/Moon Garden

MOON , MOTH, MOTHER NATURE

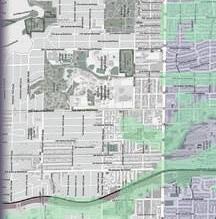

P-Patch Meets Power Transmission ROW

Site Inventory P-Patch ROW

P-Patch ROW Site Inventory

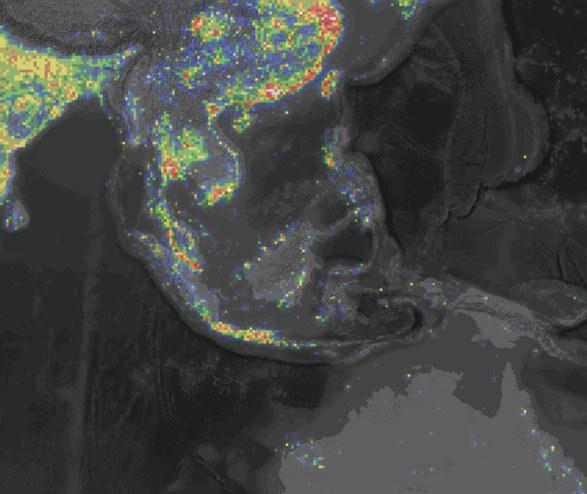

Bright Lights in the Distance

(2000’AttractionZoneonMoonlessNights fromthecorridor)

(200’AttractionZoneonMoonlitNights fromthecorridor) DarkCorridor

I-5 North I-5 South

P-Patch ROW Design Concept

Informed by site conditions and analysis, the design concept aims to organize the ROW into five zones:

Zone 1, where visitors could gather and discover the beauty of moths via outdoor sculptures.

Zone 2, for produce production and marketplace, where people would learn about the importance of moths as pollinators.

Zone 3, centers around food/host plants of moths and showcases the serenity of night gardens.

Zone 4, demonstrates moth-friendly maintenance routine with specific mowing schedule/method.

Zone 5, offers clear view of the lights across Elliott Bay and shows the severity of Seattle’s light pollution.

P-Patch ROW Core Concepts

15th Ave S

P-Patch ROW Master Plan

Gathering Space

Vegetated Crossing

Art Quarter

Rain Garden

Gibbous Plaza/Marketplace

Fountain of the Full Moon

Vegetated Crossing to the Park

Vegetated Crossing/Viewing Deck

St.

Moon Garden

Seating

New Moon Dipping Pool

Maintenance Test Plot

Crescent Pond

Nightview Overlook

Vegetated Crossing to the Forest

S Snoqualmie

S Angeline St.

Snoqualmie P-Patch Upper ROW

S Snoqualmie St

Gibbous Plaza

Snoqualmie P-Patch

Snoqualmie P-Patch Lower ROW

12th Ave S Moon Garden Moon Garden Seating

Maplewood Playfield

P-Patch ROW Lighting Plan

2000’ from the Dark Corridor:

-> Motion-sensing RED LIGHTS in outdoor residential area, and timed, warm-colored street lights on moonless nights

200’ from the Dark Corridor: -> Motion-sensing RED LIGHTS in outdoor residential area, and timed, warm-colored street lights

Gathering Space

Vegetated Crossing

Art Quarter

Rain Garden

Gibbous Plaza/Marketplace

Fountain of the Full Moon

Vegetated Crossing to the Park

Within the Dark Corridor:

Vegetated Crossing/Viewing Deck

S Snoqualmie St.

Moon Garden

Seating

-> NO LIGHTS except for motion and light-sensing red path lights along the trails, and street lights on timers under the bridges

New Moon Dipping Pool

Maintenance Test Plot

Crescent Pond

Note: All lights should be fully shielded. They should also be in warm color temperature (2200K or below) and timed or on motion sensor wherever possible.

Nightview Overlook

Vegetated Crossing to the Forest

Snoqualmie P-Patch Plants for Moths

Black Cottonwood White Alder

Douglas Fir Pacific Madrone

Red Alder

Bitter Cherry Chokecherry

Pacific Fire Vine Maple

Douglas Maple

Strawberry Trees

Dwarf White English Lavender

Black Hawthorn Lester Rowntree Manzanita

Green Manzanita Snowberry

Blue Bush Sage

Indian Plum

Deerbrush

Foothill Yucca

Variegated Butterfly Bush

Snoqualmie P-Patch Plants for Moths

Sunburst Coreopsis

Common Thyme

Rozanne Cranesbill

Philadelphia Fleabane Cape Blanco Sedum

Spreading Phlox

Northern Lights

Tufted Hair Grass

Moonflower Calendula

Sonoma Coast Yarrow

Heart-leaf Milkweed

Common Woolly Sunflower

Parry’s Penstemon

Cardwell’s Penstemon

Moss Campion

Canadian Goldenrod

Floristan White Gayfeather

Cygnet White Coneflower

Easter Bee Balm Black-Eyed Susan

Desert Evening Primrose

Culver’s Root

Snoqualmie P-Patch PNW Moon Garden Plants

Mountain Hemlock Oregon White Oak Western Crabapple Scouler’s Willow

Saskatoon Serviceberry

Seaside Buckwheat

Glacier Peak Mountain Hemlock

Munster Woodbine Honeysuckle

White Blossom Ceanothus

Wild Mock Orange Black Elderberry

Large-flowered Hybrid Clematis

Double-Flowering Crape Jasmine

White Spiraea Little Devil Ninebark Ocean Spray Pigeon Point Coyote Bush

Tomales Bay Idaho Fescue

River House Blues Fescue

Redwood Sorrel

Fernleaf Biscuitroot

Western Pearly Everlasting

Sickle Keeled Lupine

Langtree Bleeding Heart

Snoqualmie P-Patch A View of the Moon Garden

Snoqualmie P-Patch In the Absence of Light

Have Fun in the Absence of Light

While the needs of other life on Earth may be seemingly at odds with our own, having common ground where we can come together to share the space, exchange perspectives, and enrich our lives is crucial. With the help of design, creativity, and kindness, I believe we can get there. And, don’t forget to have fun!

3. Nocturnal Pollinator

1. Urban Wildlife

2. Dark Infrastructure

4. Design Toolkit

5. Moth

6. Dusk/Moon Garden

Work Cited

1. Gaynor, K. M., Hojnowski, C. E., Carter, N. H., & Brashares, J. S. (2018). The influence of human disturbance on Wildlife Nocturnality. Science, 360(6394), 1232–1235. https:// doi.org/10.1126/science.aar7121

2. Alagona, P. S. (2024). Accidental ecosystem: People and wildlife in American cities. University of California Press.

3. Cinzano, P., Falchi, F., & Elvidge, C. D. (2001). The first world atlas of the Artificial Night Sky Brightness. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 328(3), 689–707. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-8711.2001.04882.x

4. See 3.

5. Trembley, B. (2021, April 7). History of light pollution. Vatican Observatory. https:// www.vaticanobservatory.org/sacred-space-astronomy/history-of-light-pollution/

6. Falchi, F., Cinzano, P., Duriscoe, D., Kyba, C. C., Elvidge, C. D., Baugh, K., Portnov, B. A., Rybnikova, N. A., & Furgoni, R. (2016). The New World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness. Science Advances, 2(6) https://doi. org/10.1126/sciadv.1600377

7. See 6.

8. Parris, K. M. (2016). Ecology of Urban Environments. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

9. Yong, E. (2022). An immense world: How animal senses reveal the hidden realms around us; Random House.

10. Sordello, R., Busson, S., Cornuau, J. H., Deverchère, P., Faure, B., Guetté, A., Hölker, F., Kerbiriou, C., Lengagne, T., Le Viol, I., Longcore, T., Moeschler, P., Ranzoni, J., Ray, N., Reyjol, Y., Roulet, Y., Schroer, S., Secondi, J., Valet, N., … Vauclair, S. (2022). A plea for a worldwide development of dark infrastructure for biodiversity – practical examples and ways to go forward. Landscape and Urban Planning, 219, 104332. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104332

11. See 10.

12. Kampen, N. (2023a). The lighting and dark fabric plan for the Swiss city of Fribourg. ’SCAPE, 2(NIGHTSCAPES – An ode to darkness), 92–95.

13. Harsema, H. (2023a). A dark sky corridor is not just for bats. ’SCAPE, 2(NIGHTSCAPES – An ode to darkness), 158–161.

14. Harsema, H. (2023b). New times, new practice. ’SCAPE, 2(NIGHTSCAPES – An ode to darkness), 132-133.

15. de Bruijn, D., Harsema, H., & Kampen, N. (2023). Embracing the darkness. ’SCAPE, 2 (NIGHTSCAPES – An ode to darkness), 67–69.

16. Kampen, N. (2023b). ‘We need to rediscover the pleasure of night and darkness’. ’SCAPE, 2 (NIGHTSCAPES – An ode to darkness), 102–105.

17. de Bruijn, D., Harsema, H. (2023). A moonlit church. ’SCAPE, 2(NIGHTSCAPES – An ode to darkness), 142-147.

18. Douglas, K. (2017). Campus Illumination, A Roadmap to Sustainable Exterior Lighting at the University of Washington Seattle Campus. Retrieved 2024, from https://idl. be.uw.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/104/2017/10/Campus-Illumination-Roadmap_ web.pdf.

19. Bat Pollination. US Forest Service. (n.d.). https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/ wildflowers/pollinators/who-are-the-pollinators/bats

20. Cradley, M. (n.d.). Lesser long-nosed bat. Lesser long-nosed bat - Facts, Diet, Habitat & Pictures on Animalia.bio. https://animalia.bio/index.php/lesser-long-nosed-bat

21. Bosma, K. (n.d.). Mexican long-tongued bat. Mexican long-tongued bat - Facts, Diet, Habitat & Pictures on Animalia.bio. https://animalia.bio/mexican-long-tongued-bat

22. Like a moth to a flower. Pollinator Partnership. (n.d.). https://www.pollinator.org/ pollinator.org/assets/generalFiles/Like-a-Moth-to-a-Flower.pdf

23. Robertson, S. M., Dowling, A. P., Wiedenmann, R. N., Joshi, N. K., & Westerman, E. L. (2021). Nocturnal pollinators significantly contribute to Apple production. Journal of Economic Entomology, 114(5), 2155–2161. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toab145

24. Walton, R. E., Sayer, C. D., Bennion, H., & Axmacher, J. C. (2020). Nocturnal pollinators strongly contribute to pollen transport of wild flowers in an agricultural landscape. Biology Letters, 16(5), 20190877. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2019.0877

25. U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.-b). White-lined sphinx moths benefit from abundant wildflowers (U.S. National Park Service). National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/ articles/000/white-lined-sphinx-moths-benefit-from-abundant-wildflowers.htm

26. Fabian, S. T., Sondhi, Y., Allen, P. E., Theobald, J. C., & Lin, H.-T. (2024). Why flying insects gather at artificial light. Nature Communications, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467024-44785-3

27. van Klink, R., Bowler, D. E., Gongalsky, K. B., Swengel, A. B., Gentile, A., & Chase, J. M. (2020). Meta-analysis reveals declines in terrestrial but increases in freshwater insect abundances. Science, 368(6489), 417–420. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax9931

28. Macgregor, C. J., Evans, D. M., Fox, R., & Pocock, M. J. (2016). The Dark Side of street lighting: Impacts on moths and evidence for the disruption of nocturnal pollen transport. Global Change Biology, 23(2), 697–707. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13371

29. ffrench-Constant, R. H., Somers-Yeates, R., Bennie, J., Economou, T., Hodgson, D., Spalding, A., & McGregor, P. K. (2016). Light pollution is associated with earlier tree Budburst across the United Kingdom. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 283(1833), 20160813. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.0813

30. See 29.

31. Pollinator syndromes. US Forest Service. (n.d.-b). https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/ wildflowers/pollinators/syndromes#:~:text=The%20flower%20type%2C%20shape%2C%20 color%2C%20odor%2C%20nectar%2C%20and,that%20will%20aid%20the%20flower%20 in%20successful%20reproduction.

32. Eierman, K. (2020). The pollinator victory garden: Win the war on pollinator decline with ecological gardening: How to attract and support bees, beetles, butterflies, bats, and other pollinators. Quarry Books, an imprint of The Quarto Group.

33. See 31.

34. See 32.

35. Manager, J. B. L. P. (n.d.-b). Darksky approved products. DarkSky International. https://darksky.org/what-we-do/darksky-approved/luminaires/

36. Longcore, T. (2023). A compendium of photopigment peak sensitivities and visual spectral response curves of terrestrial wildlife to guide design of outdoor nighttime lighting. Basic and Applied Ecology, 73, 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. baae.2023.09.002

37. Module 147: Lighting the way for occupant wellbeing. CIBSE Journal. (2019, May 30). https://www.cibsejournal.com/cpd/modules/2019-06-eye/

38. Shawn Nielsen. (2018). Energy saving leds increasing light pollution globally. VisibleDark. https://visibledark.ca/energy-saving-leds-increasing-light-pollutionglobally/

39. Observations. iNaturalist. (n.d.). https://www.inaturalist.org/ observations?captive=false&iconic_taxa=Insecta&nelat=47.73301573257415&nel ng=-122.20685897554735&order_by=observed_on&q=moth&quality_grade=researc h&subview=map&swlat=47.45982396296905&swlng=-122.44718490328172&taxon_ id=47157&view=species

40. Seattle City Light. (2021). Seattle City Light Vegetation Management Plan Eastside Transmission Line for Critical Areas Land Use Permit City of Bellevue. Bellevue; Seattle City Light and City of Bellevue.

Acknowledgment

This report could not have reached its current state without the help of Belle Miller, Paulina Arango, Jason Henry, Guy Michaelsen, Brad McGuirt, Stephanie Smith, Christine Gannon, and many others at Berger Partnership. I would like to thank everyone for their encouragement and feedback, as well as the good humor and kindness provided to me during the process.

I would also like to extend my appreciation to Dr. Travis Longcore from the University of California, Los Angeles, Emily May from The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, and Jeff Krueger from the University of Oregon for answering my questions about light pollution mitigation strategies, pollinator insects, and designing in power transmission right-of-way respectively.

Lastly, I want to express my gratitude to our natural world for helping me tell its mysteriously wonderful stories.